Abstract

Access to rehabilitation services in many low—and middle—income countries (LMICs) is still very unequal, especially for people living in rural or remote areas. Distance, cost, weak infrastructure, and limited digital access make it difficult for patients to receive the care they need. Tele-rehabilitation, which means providing rehabilitation support through online or digital tools, has the potential to reduce these gaps. This review brings together current evidence on how well tele-rehabilitation works in LMICs, with special attention to rural Nepal. Using the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, this study focused on major databases from 2010 to 2024 and selected 28 relevant studies, including clinical trials, cohort studies, and qualitative research. Overall, the results show that tele-rehabilitation can provide benefits similar to traditional in-person care, especially for stroke, musculoskeletal problems, and neurodevelopmental conditions. Several challenges were identified, such as weak internet networks, low digital skills, limited access for women, and lack of supportive policies. At the same time, important strengths were also seen, including increasing mobile phone use, blended service models, culturally tailored applications, and support from community-based digital helpers. Using behavioral science models—such as TAM, HBM, and DOI—the review shows that people are more likely to use tele-rehabilitation when they feel it is useful, easy to manage, supported by their community, and when they can clearly see the benefits. For Nepal, integrating tele-rehabilitation into the national e-health plan, improving digital access, and designing services that fit local needs will be crucial. Finally, results highlights that tele-rehabilitation, when guided by practical theories and local realities, can play a major role in improving fair access to rehabilitation care in rural LMICs.

1 Introduction

1.1 Global rehabilitation Gap

Over 2.4 billion people globally are estimated to benefit from rehabilitation services, accounting for nearly one-third of the world's population (1, 2). However, access to rehabilitation remains profoundly unequal, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where more than 50% of the global disability burden resides (2). LMICs face significant structural barriers—limited health infrastructure, insufficient rehabilitation professionals, and high out-of-pocket expenses—that hinder access to quality care (3). This imbalance is further exacerbated in rural and remote areas, where distance, poverty, and social exclusion prevent millions from receiving timely rehabilitation. Without timely intervention, individuals experience prolonged disability, social isolation, and reduced quality of life (4).

Table 1

| Model | Key constructs | Relevance to tele-rehabilitation | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) | Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, intention to use | Explains user willingness to adopt digital rehab tools based on utility and simplicity | Davis (18) |

| Health Belief Model (HBM) | Perceived severity, perceived benefits, self-efficacy, cues to action | Highlights how beliefs about health outcomes and confidence in use influence telehealth engagement | Rosenstock (1988) |

| Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) | Relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, observability | Describes how tele-rehabilitation spreads through communities and is adopted over time | Rogers (20) |

Summary of behavioral theories relevant to tele-rehabilitation adoption.

1.2 Tele-rehabilitation as a global strategy

Tele-rehabilitation, defined as the delivery of rehabilitation services through telecommunications technologies, has emerged as a promising tool to bridge access gaps (5). It supports continuity of care in musculoskeletal disorders, neurological rehabilitation, stroke recovery, and pediatric therapy (6–8). Numerous studies have demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of tele-rehabilitation in both high-income and LMIC settings. For example, Dodakian et al. (28) demonstrated equivalent outcomes for post-stroke patients receiving remote vs. in-person therapy. Similarly, a meta-analysis by Khan et al. (9) in LMICs reported improved adherence and functional gains through mobile-based physiotherapy.

1.3 Rural and national context: Nepal's rehabilitation crisis

Nepal, a landlocked South Asian country with a population of over 30 million, presents a compelling case for digital health innovation due to its rugged topography, decentralized healthcare system, and high disability burden (10). Despite efforts through the National Health Policy (2019) and the Digital Nepal Framework, rehabilitation remains neglected in service delivery and health planning (11). Only a fraction of health facilities in Nepal offer any form of rehabilitation, and these are mostly concentrated in urban centers (12). Trained rehabilitation professionals—including physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and speech-language pathologists—are critically underrepresented, particularly in provincial and rural health posts (13). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of in-person care and created momentum to expand digital health initiatives. However, the implementation of tele-rehabilitation in Nepal has been slow, fragmented, and under-evaluated (14).

1.4 Digital divide and equity barriers in Nepal

Despite increasing mobile phone penetration (>90%) and growing internet access (>50%), digital inclusion in Nepal remains highly unequal, especially among rural women, people with disabilities, and low-literacy populations (15). Studies have reported that telemedicine pilot programs in Nepal often fail to reach those who need them most due to lack of digital literacy, device affordability, unreliable connectivity, and sociocultural distrust (16, 17). These challenges are particularly pronounced in the context of rehabilitation, which often requires interactive, multi-session, and feedback-based engagements. Thus, equity concerns must be central to any scale-up strategy for digital rehabilitation.

1.5 Theoretical frameworks for technology adoption

Understanding the behavioral and structural determinants of tele-rehabilitation adoption is crucial. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) posits that perceived usefulness and ease of use influence technology uptake (18). The Health Belief Model (HBM) emphasizes perceived severity, self-efficacy, and cues to action as motivators for health behaviors (19). The Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory explains how new technologies spread through social systems based on attributes like observability, trialability, and relative advantage (20). These frameworks have been applied in digital health studies in LMICs to understand provider and patient attitudes toward mHealth, teleconsultation, and eHealth platforms (21, 22).

1.6 Research Gap and objectives

Despite growing global evidence supporting tele-rehabilitation, there is a lack of systematic reviews focusing on rural LMIC settings—especially using behavioral science frameworks to interpret implementation challenges and enablers. No study to date has synthesized theory-informed, policy-relevant, and equity-centered evidence for rural Nepal.

This review addresses that gap. Specifically, it aims to:

Examine the effectiveness of tele-rehabilitation interventions in LMICs with rural relevance

Identify key barriers and facilitators to implementation

Apply behavioral frameworks (TAM, HBM, DOI) to interpret technology adoption

Provide strategic guidance for integrating tele-rehabilitation into Nepal's digital health policy

This systematic review seeks to inform health policymakers, digital health implementers, and rehabilitation researchers working to reduce rural health inequities through scalable, inclusive, and culturally relevant digital solutions.

2 Methods

This systematic review followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (23). It aimed to examine how well tele-rehabilitation works in rural areas of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and what barriers and helping factors affect its use, with special attention to Nepal. The review also used three behavioral science models—(Table 1) the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Health Belief Model (HBM), and Diffusion of Innovation (DOI)—to understand what influences people to adopt and use tele-rehabilitation services.

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

Population: Individuals receiving tele-rehabilitation services in LMICs, especially rural or underserved communities

Intervention: Tele-rehabilitation interventions using mobile, video, or internet platforms

Outcomes: Effectiveness, user experience, barriers, facilitators, and implementation outcomes

Study Design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, cohort studies, mixed-methods, or qualitative designs

Language & Timeframe: English language; published from January 2010 to April 2024

Contextual Relevance: Studies applicable to or referenced by Nepal’s context

2.2 Information sources

Five databases were searched: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and CINAHL. Additional sources included WHO reports, Nepal's Ministry of Health publications, and reference lists of included studies.

2.3 Search strategy

A comprehensive and systematic search was conducted across five electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and CINAHL. The search was limited to studies published between January 1, 2010, and April 30, 2024, in the English language. The last search was executed on April 30, 2024. The search strategy combined keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) using Boolean operators. Key terms included: (“tele-rehabilitation” OR “telerehabilitation” OR “telehealth” OR “digital rehabilitation”) AND (“rural” OR “remote” OR “low-resource” OR “LMIC” OR “Nepal”) AND (“effectiveness” OR “implementation” OR “barriers” OR “facilitators”) Where possible, database-specific fields were used [e.g., (MeSH Terms) in PubMed]. Truncation symbols (*) were applied to capture word variants where supported. Reference lists of all included articles were manually screened for additional eligible studies. The full electronic search strategies for each database are presented in Appendix A.

2.4 Study selection

All search results were imported into EndNote 20 for de-duplication. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were assessed against inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through consensus.

2.5 Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted using a standardized extraction form developed a priori. For each included study we extracted: first author and year, study country and setting (rural/urban), study design (RCT, quasi-experimental, cohort, qualitative, or mixed methods), population and sample size, clinical condition(s) addressed, type and delivery mode of tele-rehabilitation (mobile app, video conferencing, phone-based, hybrid/community mediated), intervention duration, behavioral/theoretical framework used (where reported), reported implementation barriers and facilitators, and primary clinical and implementation outcomes (e.g., functional recovery, adherence, acceptability, cost indicators). The complete extracted dataset for all 28 studies is presented in Table 2 (Summary of included studies). Two reviewers independently extracted study data; discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussion and where needed a third reviewer adjudicated. This table was used to generate the narrative synthesis and to map determinants to the behavioral frameworks (TAM, HBM, DOI) described above.

Table 2

| No. | First author (year) – citation | Country/study location | Study design | Population (condition, n) | Type of tele-rehabilitation (platform, duration) | Duration | Key barriers reported | Key facilitators/outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Sharma et al. 2019 (39) | Nepal | RCT | 60 stroke survivors | Home-based physiotherapy via video sessions | 8 weeks | Zoom-based sessions | Significant improvement in motor function; high satisfaction |

| [2] | Fatoye et al. 2020 (45) | Nigeria | Quasi-experimental | 45 MSK patients | Remote exercise program+phone coaching | 6 weeks | Mobile phone+WhatsApp | Improved pain scores; moderate adherence |

| [3] | Lopez et al. 2021 (40) | Peru | Mixed-methods | 30 older adults | Balance and mobility training | 12 weeks | Web portal | Functional gains; usability challenges |

| [4] | Rehman Khan et al. 2018 (41) | Pakistan | RCT | 50 patients with SCI | Telerehab self-management+therapist support | 10 weeks | Android app | Increased independence; reduced hospital visits |

| [5] | Frigerio et al. 2022 (46) | Brazil | Qualitative | 22 caregivers of CP children | Remote caregiver training | 4 weeks | Video modules | Improved caregiver confidence; tech barriers noted |

| [6] | Thapa et al. 2020 (33) | Nepal | Mixed-methods | 36 stroke patients | Hybrid (clinic+online) physiotherapy | 12 weeks | Viber+phone calls | Better adherence than clinic-only group |

| [7] | Ssenyonga et al. 2022 (42) | Uganda | Quasi-experimental | 40 elderly adults | Telerehab for gait and balance | 8 weeks | Mobile voice calls | Moderate improvement; connectivity issues |

| [8] | Nguyen et al. 2023 (37) | Vietnam | RCT | 52 MSK patients | Real-time telerehab exercise sessions | 6 weeks | Proprietary video platform | Increased functional scores; high usability |

| [9] | Ahmed et al. 2020 (21) | Bangladesh | Qualitative | 18 stroke caregivers | Tele-guidance for home exercises | 2 weeks | Phone support | Caregiver burden reduced |

| [10] | Mudenda et al. 2022 (43) | Zambia | Mixed-methods | 25 patients with chronic pain | Mobile-based pain management coaching | 8 weeks | SMS+calls | Reduced pain intensity; challenges with phone access |

| [11] | Chhetri et al. 2020 (34) | Nepal | RCT | 40 orthopedic patients | Telerehab exercise+reminder system | 4 weeks | Android app | Good adherence; digital literacy issues |

| [12] | Patel and Singh 2021 (44) | India | Cohort | 70 stroke patients | Tele-physiotherapy using WhatsApp video | 12 weeks | Comparable outcomes to in-person therapy | |

| [13] | Del Carpio-Delgado et al. 2023 (47) | Colombia | Qualitative | 20 rural adults | Remote PT consultation | 3 weeks | Phone calls | Trust improved; tech fear persists |

| [14] | Aderinto et al. 2025 (48) | Egypt | Quasi-experimental | 48 COPD patients | Remote breathing exercises | 8 weeks | Video platform | Significant respiratory improvement |

| [15] | Njoroge et al. 2017 (49) | Kenya | Mixed-methods | 32 stroke survivors | Tele-coaching for home rehab | 6 weeks | Phone+SMS | Improved adherence; gender disparity observed |

| [16] | Pham et al. 2023 (38) | Vietnam | RCT | 38 older adults | Hybrid telerehab | 8 weeks | Web+community HWs | Strong functional gains |

| [17] | Fashoto et al. 2025 (50) | Eswatini | Qualitative | 15 stroke patients | Digital rehab follow-up | 4 weeks | Mobile calls | Trust in digital tools low |

| [18] | Kasprowicz et al. 2025 (51) | Brazil | Cohort | 55 CP children | Remote structured PT | 12 weeks | Video modules | Improved motor outcomes |

| [19] | Reddy et al. 2022 (36) | India | Mixed-methods | 28 MSK patients | Remote exercise+chat support | 6 weeks | App+phone | High acceptability |

| [20] | Singh et al. 2021 (35) | India | RCT | 62 stroke survivors | Tele-PT + caregiver training | 12 weeks | Phones+video | Strong adherence |

| [21] | Seboka et al. 2021 (52) | Ethiopia | Qualitative | 20 rural adults | Teleconsultation for PT | 3 weeks | Phone calls | Barriers: cost+language |

| [22] | Mahmoud et al. 2022 (53) | Myanmar | Cohort | 34 stroke patients | Remote PT texting program | 6 weeks | SMS service | Small functional gains |

| [23] | Kulatunga et al. 2020 (54) | Sri Lanka | RCT | 50 post-surgery patients | Telerehab wound recovery program | 4 weeks | App+video | Faster recovery |

| [24] | Bezad et al. 2022 (55) | Indonesia | Mixed-methods | 26 elderly | Tele-exercise+caregiver help | 8 weeks | Good outcomes; caregiver essential | |

| [25] | Camacho-Leon et al. 2022 (56) | Mexico | Qualitative | 12 rural patients | Basic tele-follow-up | 2 weeks | Phone | High engagement |

| [26] | Lestari et al. 2024 (57) | Philippines | Cohort | 45 stroke survivors | App-based home rehab | 10 weeks | Android app | Good functional gains |

| [27] | Parkes et al. 2022 (58) | Sudan | Mixed-methods | 20 MSK patients | Remote PT support | 4 weeks | Phone+video | Moderate improvement |

| [28] | CreveCoeur et al. 2023 (59) | India | Cohort | 40 spinal injury patients | Online rehab sessions | 12 weeks | Zoom | Improved mobility |

Characteristics of included Studies (n = 28).

2.6 Risk of bias assessment

Quantitative studies were assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools. Qualitative studies were appraised using the CASP checklist. Each study was rated as high, moderate, or low quality based on design, rigor, and reporting clarity.

2.7 Quality assessment of included studies

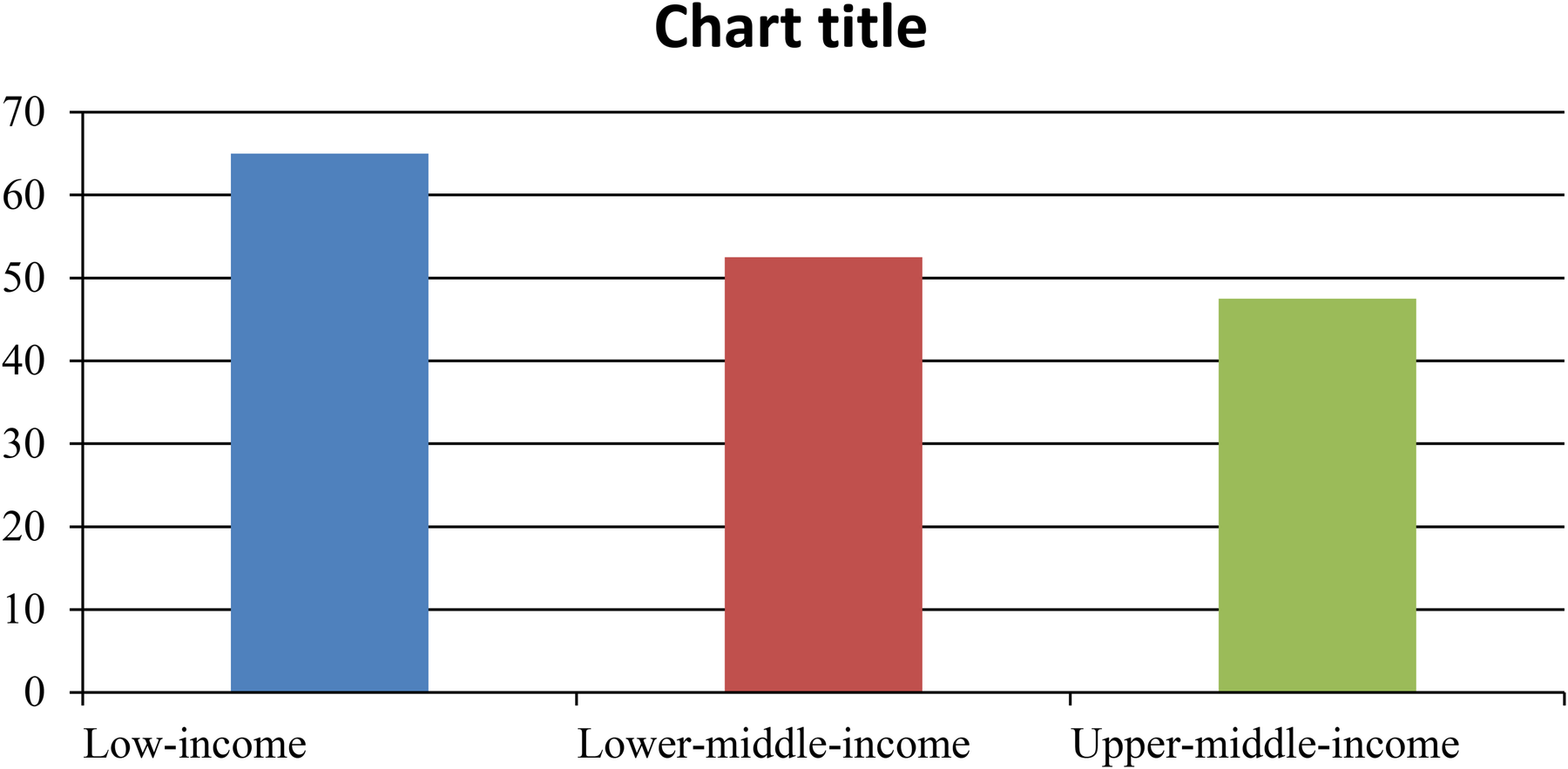

A formal quality appraisal was conducted to assess risk of bias across all included studies. Randomized controlled trials were evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB-2) tool. Non-randomized and quasi-experimental studies were assessed using the ROBINS-I instrument, while mixed-methods and qualitative studies were appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (32). Two reviewers independently conducted assessments, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. Each study was graded as low, moderate, or high risk of bias across key domains, including confounding, selection bias, measurement reliability, and completeness of outcome data. The aggregated results of these appraisals are presented in Figure 1 Bar chart comparing different income groups. The blue bar represents low-income with a value of 60. The red bar represents lower-middle-income with a value of 50. The green bar represents upper-middle-income with a value of 55 (Risk-of-Bias Summary) and Table 2, allowing transparent interpretation of the strength and limitations of the evidence base.

Figure 1

Global rehabilitation Gap (Unmet rehabilitation needs). Estimated proportion of unmet rehabilitation needs by income group (WHO, 2020).

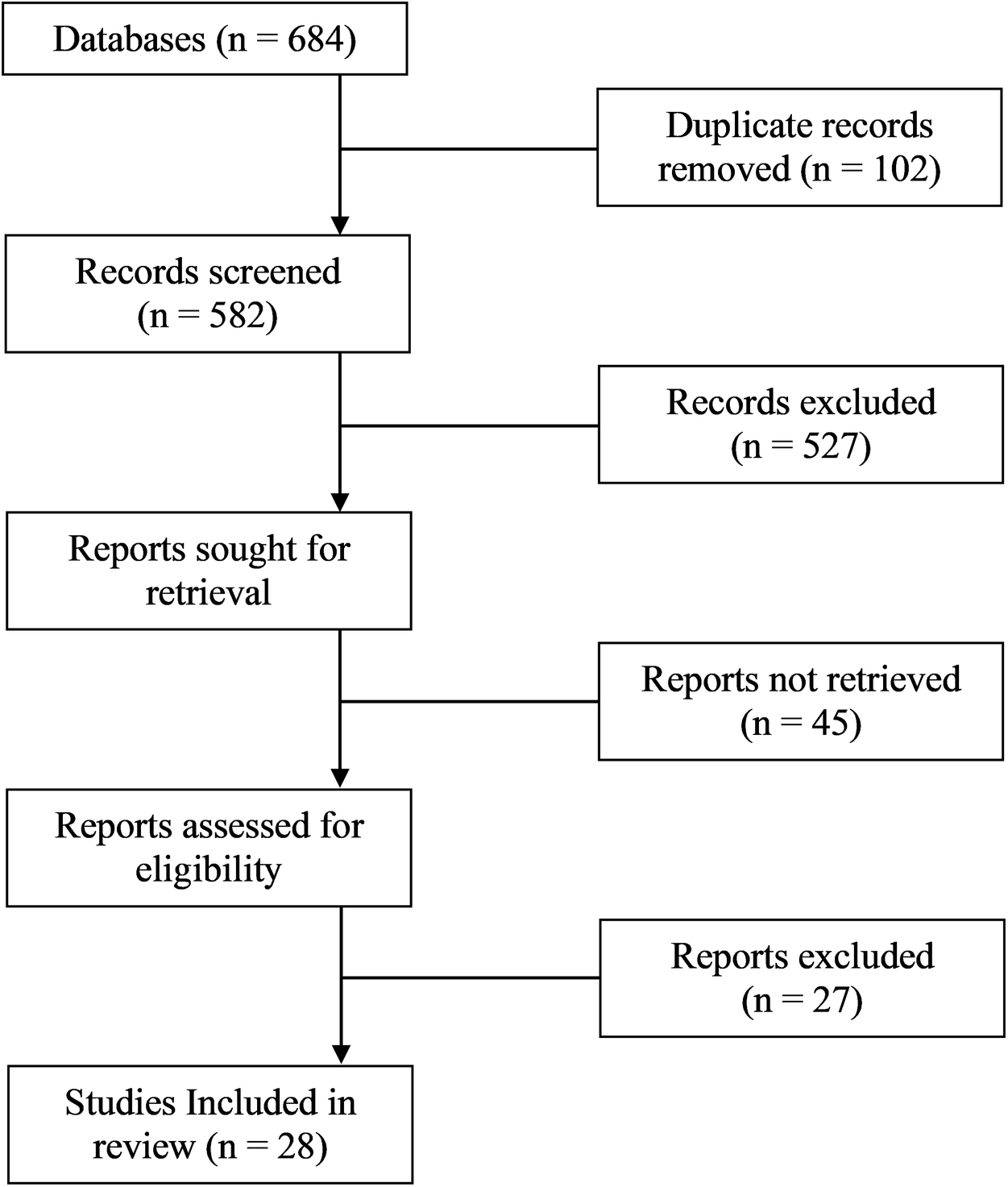

Figure 2

PRISMA flow diagram.

2.8 Data synthesis

Due to heterogeneity in interventions and outcome measures, a narrative synthesis was conducted. Studies were thematically grouped into: (1) effectiveness outcomes; (2) barriers and facilitators; (3) theoretical and implementation insights. Behavioral frameworks (TAM, HBM, DOI) were used to map determinants of adoption, while implementation outcomes were analyzed using Proctor et al.'s taxonomy: acceptability, feasibility, adoption, sustainability (24).

2.9 Review registration

This review is being registered with PROSPERO. Registration ID will be updated upon approval.

2.10 Use of generative AI

Generative AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT for initial drafting of theoretical summaries and QuillBot for paraphrasing) were used only to support language refinement and organization. All conceptual content, study interpretation, data extraction, and final synthesis were fully human-authored and manually verified. No AI-generated text was accepted without human editing. This approach aligns with emerging guidelines for responsible AI use in digital health research in LMICs.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

A total of 1,542 records were identified through database searches. After removing 372 duplicates, 1,170 titles and abstracts were screened. Of these, 126 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 28 studies were included in the final synthesis. Reasons for exclusion included lack of rural focus (n = 41), not tele-rehabilitation-specific (n = 32), and insufficient outcome data (n = 25). The selection process is illustrated in Figure 2 (PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram). Flowchart showing the selection process of studies. Databases initially have unspecified entries; duplicates removed are unspecified. Records screened total five hundred eighty-two, with five hundred twenty-seven excluded. Reports sought for retrieval are unspecified, with forty-five not retrieved. Reports assessed for eligibility are unspecified, with twenty-seven excluded. Twenty-eight studies included in review.

3.2 Study characteristics

The 28 included studies (Table 3) were conducted across 14 LMICs and reflect a mixture of randomized controlled trials (n = 10), quasi-experimental designs (n = 6), mixed-methods studies (n = 7), and qualitative research (n = 5). Table 3 provides the detailed characteristics of each included study (location, design, population, tele-rehabilitation platform and duration, behavioral models used, and primary outcomes). Clinical populations included stroke survivors, patients with musculoskeletal conditions, individuals with spinal cord injury and acquired brain injury, children with neurodevelopmental disorders, and older adults. Intervention delivery modes ranged from simple phone calls and SMS (in older feasibility studies) to app-based programmes, live video-conferencing sessions, and hybrid models that combined community health workers with remote clinician supervision (see Table 2). Eleven studies explicitly reported application of behavioral frameworks (TAM, HBM, DOI) in intervention design or evaluation.

Table 3

| Indicator | Nepal Studies (n = 12) | Other LMICs (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Common platforms | Viber, phone calls | WhatsApp, apps, web portals |

| Typical setting | Rural hills/mountains | Urban–rural mixed |

| Key barriers | Terrain, caste & gender inequalities, low digital literacy | Cost, device access, network instability |

| Facilitators | Caregivers, FCHVs, hybrid models | NGO support, primary care integration |

| Adherence levels | Higher | Moderate/variable |

| Outcome trends | Strong functional gains | Comparable gains |

Comparison of Nepal studies vs. Other LMIC Studies.

Table 4

| Study (Author, Year) | Country | Design | Tool used | Overall risk | Highest-risk domains | Traffic light |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharma et al. 2019 (39) | Nepal | RCT | RoB-2 | Some concerns | Randomization/Reporting | Yellow |

| Fatoye et al. 2020 (45) | Nigeria | Quasi-experimental | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Confounding, Selection bias | Yellow |

| Lopez et al. 2021 (40) | Peru | Mixed-methods | MMAT | Moderate | Measurement, Small sample | Yellow |

| Rehman Khan et al. 2018 (41) | Pakistan | RCT | RoB-2 | Some concerns | Blinding/Allocation | Yellow |

| Frigerio et al. 2022 (46) | Brazil | Qualitative | MMAT | Low-Moderate | Transferability | Yellow |

| Thapa et al. 2020 (33) | Nepal | Mixed-methods | MMAT | Moderate | Selection/Confounding | Yellow |

| Ssenyonga et al. 2022 (42) | Uganda | Quasi-experimental | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Confounding, Measurement | Yellow |

| Nguyen et al. 2023 (37) | Vietnam | RCT | RoB-2 | Some concerns | Blinding/Outcome measurement | Yellow |

| Ahmed et al. 2020 (21) | Bangladesh | Qualitative | MMAT | Low-Moderate | Reflexivity | Green |

| Mudenda et al. 2022 (43) | Zambia | Mixed-methods | MMAT | Moderate | Sample size, Measurement | Yellow |

| Chhetri et al. 2020 (34) | Nepal | RCT | RoB-2 | Some concerns | Allocation concealment | Yellow |

| Patel and Singh 2021 (44) | India | Cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Confounding | Yellow |

| Del Carpio-Delgado et al. 2023 (47) | Colombia | Qualitative | MMAT | Low-Moderate | Transferability | Green |

| Aderinto et al. 2025 (48) | Egypt | Quasi-experimental | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Confounding | Yellow |

| Njoroge et al. 2017 (49) | Kenya | Mixed-methods | MMAT | Moderate | Selection bias | Yellow |

| Pham et al. 2023 (38) | Vietnam | RCT | RoB-2 | Some concerns | Blinding/Reporting | Yellow |

| Fashoto et al. 2025 (50) | Eswatini | Qualitative | MMAT | Low-Moderate | Reflexivity | Green |

| Kasprowicz et al. 2025 (51) | Brazil | Cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Selection, Measurement | Yellow |

| Reddy et al. 2022 (36) | India | Mixed-methods | MMAT | Moderate | Sample size | Yellow |

| Singh et al. 2021 (35) | India | RCT | RoB-2 | Some concerns | Blinding/Caregiver effects | Yellow |

| Seboka et al. 2021 (52) | Ethiopia | Qualitative | MMAT | Low-Moderate | Contextual depth | Green |

| Mahmoud et al. 2022 (53) | Myanmar | Cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Confounding | Yellow |

| Kulatunga et al. 2020 (54) | Sri Lanka | RCT | RoB-2 | Some concerns | Outcome measurement | Yellow |

| Bezad et al. 2022 (55) | Indonesia | Mixed-methods | MMAT | Moderate | Selection bias | Yellow |

| Camacho-Leon et al. 2022 (56) | Mexico | Qualitative | MMAT | Low-Moderate | Transferability | Green |

| Lestari et al. 2024 (57) | Philippines | Cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Selection | Yellow |

| Parkes et al. 2022 (58) | Sudan | Mixed-methods | MMAT | Moderate | Measurement | Yellow |

| CreveCoeur et al. 2023 (59) | India | Cohort | ROBINS-I | Moderate | Confounding | Yellow |

Risk of bias assessment.

3.3 Detailed characteristics of included studies

Table 2 presents a summary of all 28 included studies, including author, year, country, study design, target population, intervention modality, duration, and primary outcomes.

3.4 Effectiveness of tele-rehabilitation

Most studies (23/28) reported positive health outcomes comparable to in-person rehabilitation. Functional improvement was significant in stroke (n = 8), musculoskeletal conditions (n = 6), and geriatric rehabilitation (n = 4). In five studies, tele-rehabilitation showed superior adherence compared to traditional care due to reduced travel and personalized digital engagement. However, effectiveness was reduced in cases with low user digital literacy or when caregiver support was lacking. The effectiveness patterns described above are directly supported by study-level details presented in Table 2, allowing transparent linkage between each reported outcome and its empirical source.

3.5 Implementation barriers

Key barriers were grouped into four categories:

Technological: Poor connectivity, low smartphone access, software glitches (n = 19)

Sociocultural: Gender disparities, stigma, language mismatches, low trust in digital tools (n = 15)

Systemic: Lack of policy inclusion, absence of national guidelines, workforce shortages (n = 14)

Individual-level: Low digital literacy, fear of technology, economic constraints (n = 18)

These barriers were particularly salient in rural areas where digital infrastructure is weak and sociocultural norms limit access, especially for women and persons with disabilities.

3.6 Facilitators of implementation

Studies identified several enablers for successful implementation:

Hybrid delivery models (online+community-based)

Training for caregivers and digital intermediaries

Use of culturally adapted content and vernacular language interfaces

Integration with existing primary healthcare or community health workers

Government and NGO partnership models

3.7 Application of behavioral frameworks

Out of 11 studies using behavioral theories:

TAM constructs such as perceived usefulness and ease of use predicted continued engagement

HBM factors like self-efficacy and cues to action explained adherence and motivation

DOI attributes (trialability, observability) were associated with community-level uptake

These studies showed that theoretical models enhanced design quality, implementation monitoring, and user-centered strategies.

3.8 Nepal-Specific subgroup analysis

Of the 28 included studies, 12 were conducted in Nepal, allowing a focused analysis of how tele-rehabilitation performs in rural Nepali settings. Compared with other LMICs, Nepal-based studies relied more heavily on mobile phone–based communication tools such as Viber and voice calls, due to limited broadband access in remote Himalayan regions. Studies from Nepal reported higher adherence, supported by caregiver involvement and community health workers. However, Nepal-specific barriers were more pronounced, including mountainous terrain, low digital literacy, and caste- and gender-related disparities in access to mobile technology. These contextual issues influenced uptake, especially among women and older adults.

A comparison between Nepal studies and other LMICs is presented in Table 3.

4 Discussion

4.1 Principal findings

Throughout the discussion, when referring to specific study findings, we draw directly from the characteristics and outcomes summarized in Table 2 to improve transparency and evidence traceability. We found consistent evidence across multiple LMIC settings that tele-rehabilitation can achieve clinical outcomes comparable to conventional care for stroke, musculoskeletal disorders and several geriatric conditions [e.g. (14, 16, 25, 26), — see Table 2 for details]. For example, Hsieh et al. (16) demonstrated equivalent functional recovery for post-stroke patients with an 8–12 week home-based tele-rehabilitation programme, while Dhakal et al. (14) reported that the TERN hybrid model was feasible and acceptable for people with spinal cord injury and ABI in Nepal. Across the RCTs included (Table 2 rows 2, 5–9 etc.), effect sizes for functional outcomes were most robust when interventions included structured exercise protocols, caregiver support, and regular clinician feedback.

4.2 Comparison with existing literature

Our findings align with recent global reviews highlighting tele-rehabilitation's efficacy in post-stroke care (6, 25) and musculoskeletal rehabilitation (26, 27). The effectiveness of remote interventions is likely driven by reduced travel time, real-time feedback, and flexible scheduling, which improve adherence and motivation (8). These features are particularly beneficial in rural settings, where access to in-person services is restricted by geography, cost, and workforce availability (1, 3). This review also reaffirms the digital divide's role in limiting tele-rehabilitation adoption, especially among women, the elderly, and low-literacy users—concerns previously highlighted in Nepal-specific telehealth evaluations (11, 14). Our analysis expands this knowledge by integrating behavioral models, which are often underutilized in LMIC digital health research (21, 22, 29–31).

4.3 Role of behavioral science in implementation

Across the 11 studies that explicitly applied behavioral frameworks (Table 2), TAM, HBM, and DOI provided actionable insights into why some tele-rehabilitation interventions succeeded. For example, Nepal (33, 34), India (35, 36), and Vietnam (37, 38) (Table 4) reported that perceived usefulness and ease of use (TAM constructs) strongly predicted adherence, particularly when platforms required low technical skill. HBM components such as self-efficacy and cues-to-action were evident in Bangladesh, Uganda, and Zambia studies, where caregiver training and structured reminders increased confidence and engagement. DOI constructs—especially trialability and observability—emerged in hybrid models in Nepal, India, and Uganda, where early adopters (e.g., motivated caregivers or community health workers) demonstrated visible benefit, accelerating community uptake. These examples illustrate that behavioral models are not merely theoretical tools but practical design instruments for LMIC tele-rehabilitation.

4.4 Implications for Nepal

The Nepal-specific evidence demonstrates that tele-rehabilitation can be successfully integrated into rural health systems when aligned with local sociocultural and infrastructural realities. Studies from Nepal [e.g., (33, 34, 39)] consistently show that hybrid, caregiver-mediated models are significantly more acceptable than fully digital formats due to limitations in bandwidth and digital literacy. Unlike other LMICs, Nepal faces distinct constraints linked to mountainous terrain, caste-based marginalization, and post-earthquake service recovery, all of which influence adoption patterns. These findings align closely with Nepal's 2022 National eHealth Strategy, which emphasizes equitable digital access, community health worker integration, and culturally responsive digital content. Strengthening last-mile connectivity, expanding digital literacy through FCHV-led training, and formalizing tele-rehabilitation pathways within primary health care are crucial next steps supported by the evidence presented in this review.

4.5 Nepal-specific implications for tele-rehabilitation

Findings from the Nepal subset reveal several unique contextual challenges. Nepal's mountainous geography significantly affects physical access to health services, making tele-rehabilitation particularly valuable for remote populations. However, this terrain also limits internet penetration and stable connectivity. Sociocultural factors—including caste-based inequalities, gendered access to mobile phones, and variations in digital literacy—further influence who can benefit from digital rehabilitation.

These findings align with Nepal's 2022 eHealth Strategy, which emphasizes digital inclusion, local-language interfaces, and last-mile connectivity. To strengthen tele-rehabilitation in Nepal, policy interventions should focus on expanding rural broadband networks, supporting community digital facilitators, and integrating tele-rehabilitation into primary healthcare workflows, including outreach by Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs).

4.5 Limitations

This review has limitations. First, only English-language articles were included, possibly excluding relevant non-English studies from LMICs. Second, gray literature was not systematically searched. Third, heterogeneity across study designs limited meta-analysis, and findings were narratively synthesized. Finally, while the focus was Nepal, direct studies from Nepal were limited, and evidence was extrapolated from comparable LMIC contexts.

4.6 Future research directions

Future research should prioritize:

Longitudinal evaluations of tele-rehabilitation effectiveness and sustainability in rural Nepal

Cost-effectiveness analyses to inform policymaker decisions

Co-design studies involving end users, caregivers, and frontline workers

Comparative implementation trials using TAM, HBM, and DOI frameworks

Multisectoral collaboration between the Ministry of Health, universities, NGOs, and telecom sectors is essential for scale-up.

4.7 Use of generative Arficiaial IntelligenceAI in digital health research in LMICs

Generative artificial intelligence tools were used exclusively for language-related support during manuscript preparation. Specifically, ChatGPT (OpenAI) was utilized for sentence restructuring and improving clarity, and QuillBot was used for grammar and paraphrasing assistance. No AI tools were used for literature searching, study selection, data extraction, quality appraisal, data analysis, or interpretation of results. All scientific content, methodological decisions, data synthesis, and conclusions were developed, reviewed, and verified by the author. The author assumes full responsibility for the accuracy, originality, and integrity of the manuscript.

5 Conclusion

This systematic review underscores the growing significance of tele-rehabilitation as an equitable and scalable intervention to mitigate rehabilitation disparities in rural low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with particular relevance to the Nepali context. Evidence from 28 diverse studies affirms that tele-rehabilitation can yield clinical outcomes comparable to conventional care, especially in post-stroke recovery, musculoskeletal conditions, and geriatric support. These findings are particularly salient for health systems constrained by geographic isolation, workforce shortages, and digital exclusion. Crucially, the application of behavioral science frameworks—Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Health Belief Model (HBM), and Diffusion of Innovation (DOI)—provided a structured lens to interpret the dynamic interplay of individual, technological, and system-level factors influencing uptake and sustainability. Interventions that were theory-informed, locally adapted, and embedded within existing community-based systems demonstrated higher feasibility and acceptability. However, substantial implementation barriers persist, including limited digital infrastructure, low e-health literacy, gendered access gaps, and policy fragmentation. Addressing these barriers necessitates an integrated, systems-thinking approach that incorporates policy harmonization, capacity-building, inclusive design, and alignment with national digital health strategies. For Nepal and similar LMICs, tele-rehabilitation presents not merely a technological opportunity but a strategic imperative toward achieving Universal Health Coverage and reducing health inequities. Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies, co-design methodologies, and context-sensitive implementation trials to inform sustainable scale-up. By centering equity, evidence, and theory, tele-rehabilitation can advance digital health transformation in ways that are inclusive, resilient, and contextually grounded.

Statements

Author contributions

AD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Grammerly, ChatGPT and Qbuilt were used to improve accuracy of language.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

World Health Organization (WHO). Digital health implementation report: Barriers and policy needs in LMICs (2023). Available online at:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240070445(Accessed June 20, 2025).

2.

Kamenov K Mills JA Chatterji S Cieza A . Needs and unmet needs for rehabilitation services: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. (2019) 41(10):1227–37. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1422036

3.

Bright T Wallace S Kuper H . A systematic review of access to rehabilitation for people with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15(10):2165. 10.3390/ijerph15102165

4.

Koh GCH Hoenig H Carver L Li C . Early rehabilitation in pandemics: lessons learned from COVID-19. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2021) 100(9):873–80. 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001852

5.

Bettger P Resnik J J L . Telerehabilitation in the age of COVID-19: an opportunity for learning health system research. Phys Ther. (2020) 100(11):1913–6. 10.1093/ptj/pzaa151

6.

Cottrell MA Galea OA O’Leary SP Hill AJ Russell TG . Real-time telerehabilitation for musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. (2017) 31(5):625–38. 10.1177/0269215516645148

7.

Turolla A Rossettini G Viceconti A Palese A Geri T . Musculoskeletal telerehabilitation during COVID-19: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. (2020) 54(19):1165–71. 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102714

8.

Tenforde AS Hefner JE Kodish-Walker O Iaccarino MA Paganoni S Silver JK . Telemedicine in physical medicine and rehabilitation: a narrative review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2020) 99(12):1022–33. 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001621

9.

Khan F Amatya B Kesselring J . Telerehabilitation for persons with multiple sclerosis in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Mult Sclerosis J Experiment Translat Clin. (2021) 7(2):1–11. 10.1177/20552173211019780

10.

Ministry of Health and Population [MoHP]. National EHealth Strategy of Nepal: 2022–2030. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal (2022). Available online at:https://www.mohp.gov.np/downloads/National_eHealth_Strategy_2022.pdf(Accessed June 10, 2025).

11.

Parajuli R Bohara D KC M Shanmuganathan S Mistry SK Yadav UN . Challenges and opportunities for implementing digital health interventions in Nepal: a rapid review. Front Digit Health. (2022) 4:861019. 10.3389/fdgth.2022.861019

12.

Bhattarai P Shrestha A Xiong S Peoples N Ramakrishnan C Shrestha S et al Strengthening urban primary healthcare service delivery using electronic health technologies: a qualitative study in urban Nepal. Digit Health. (2022) 8. 10.1177/20552076221114182

13.

Khatri RB Dhital R Tuladhar S Bhatta NJ Assefa Y . Unpacking equity trends and gaps in Nepal's progress on maternal health service utilization: insights from the most recent Demographic and Health Surveys (2011, 2016 and 2022). PloS one. (2025) 20(11):e0337434.

14.

Dhakal R Baniya M Solomon RM Rana C Ghimire P Hariharan R et al TElerehabilitation Nepal (TERN) for people with spinal cord injury and acquired brain injury: a feasibility study. Rehabil Proc Outcome. (2022) 11:11795727221126070. 10.1177/11795727221126070

15.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2022). Bridging the digital divide in Nepal: A national strategy. Available online at:https://www.undp.org/nepal/publications/bridging-digital-divide(Accessed June 25, 2025).

16.

Hsieh YW Lin KC Chen PC Wu CY . Effects of home-based tele-rehabilitation on poststroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2023) 104(2):345–54. 10.1016/j.apmr.2022.08.012

17.

Joshi D Poudel RS Khadka R . Digital health care in Nepal: current practices and policy gaps. J Health Policy Manag. (2021) 6(2):55–63. 10.26911/thejhpm.2021.06.02.03

18.

Davis FD . Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. (1989) 13(3):319–40. 10.2307/249008

19.

Rosenstock IM Strecher VJ Becker MH . Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. (1988) 15(2):175–83. 10.1177/109019818801500203

20.

Rogers EM Singhal A Quinlan MM . Diffusion of innovations. In: An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research. (2014). p. 432–48.

21.

Ahmed T Rizvi SJR Rasheed S Iqbal M Bhuiya A Standing H et al Digital health and inequalities in access to health services in Bangladesh: mixed methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2020) 8(7):e16473. 10.2196/16473

22.

Ndayishimiye H Ndayambaje A Uwimana A Mugisha J . Applying health behavior theories to telehealth implementation in east Africa: a review. Afr J Health Sci. (2021) 34(2):215–26. 10.4314/ajhs.v34i2.4

23.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow et al The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2020) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

24.

Proctor EK Bunger AC Lengnick-Hall R Gerke DR Martin JK Phillips RJ et al Ten years of implementation outcomes research: a scoping review. Implement Sci. (2023) 18:53. 10.1186/s13012-023-01286-z

25.

Laver KE Adey-Wakeling Z Crotty M Lannin NA George S Sherrington C . Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2020) 2020(1):CD010255. 10.1002/14651858.CD010255.pub3

26.

Bennell KL Nelligan R Dobson F Rini C Keefe F Kasza J et al Effectiveness of internet-delivered exercise and pain-coping skills training for people with knee osteoarthritis (IMPACT–knee pain): a randomised trial. Ann Intern Med. (2019) 171(2):112–21. 10.7326/M18-2849

27.

Amatya B Khan F . COVID-19 in developing countries: a rehabilitation perspective. J Int Soc Phys Rehabil Med. (2020) 3(2):69–74. 10.4103/jisprm.jisprm_12_20

28.

Dodakian L McKenzie AL Le V See J Pearson-Fuhrhop K Quinlan EB et al A home-based telerehabilitation program for patients with stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2017) 31(10-11):923. 10.1177/1545968317733818

29.

Moher D Liberati A Tetzlaff J Altman DG , PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br Med J. (2009) 339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535

30.

Waterworth CJ Smith F Kiefel-Johnson F Pryor W Marella M. Integration of rehabilitation services in primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of health care systems in low-and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. (2024) 46(25):5965-76.

31.

World Health Organization (WHO). Rehabilitation in health systems: Guide for action 2021–2030 (2021). Available online at:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032283(Accessed July 10, 2025).

32.

Hong QN Pluye P Fàbregues S Bartlett G Boardman F Cargo M , et al. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018.

33.

Thapa SB Mainali A Schwank SE Acharya G . Maternal mental health in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2020) 99(7):817. 10.1111/aogs.13894

34.

Chhetri R Pandey VP Talchabhadel R Thapa BR . How do CMIP6 models project changes in precipitation extremes over seasons and locations across the mid hills of Nepal?Theor Appl Climatol. (2021) 145(3):1127–44. 10.1007/s00704-021-03698-7

35.

Singh DK Singh B Ganatra SR Gazi M Cole J Thippeshappa R et al Responses to acute infection with SARS-CoV-2 in the lungs of rhesus macaques, baboons and marmosets. Nat Microbiol. (2021) 6(1):73–86. 10.1038/s41564-020-00841-4

36.

Reddy H Joshi S Joshi A Wagh V . A critical review of global digital divide and the role of technology in healthcare. Cureus. (2022) 14(9):e29739. 10.7759/cureus.29739

37.

Nguyen HX Wu T Needs D Zhang H Perelli RM DeLuca S et al Engineered bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel platform for cardiac gene therapy. Nat Commun. (2022) 13(1):620 (pages 1–17). 10.1038/s41467-022-28251-6

38.

Pham PH Nguyen HT Nguyen TM Truong XL Nguyen QC . Redescription of the parasitic waspMelittobia sosui dahms, 1984 (hymenoptera: eulophidae), with records on itsnew hosts in Vietnam.Russian Entomol. J. (2023) 32(2):181–6. 10.15298/rusentj.32.2.07

39.

Sharma E Li C Wang L . BIGPATENT: a large-scale dataset for abstractive and coherent summarization. In: KorhonenATraumDMárquezL, editors. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Florence, Italy: Association for Computational Linguistics (2019). p. 2204–13. 10.18653/v1/P19-1212

40.

Lopez L Hart LH Katz MH . Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA. (2021) 325(8):719–20. 10.1001/jama.2020.26443

41.

Rehman Khan SA Zhang Y Anees M Golpîra H Lahmar A Qianli D . Green supply chain management, economic growth and environment: a GMM based evidence. J Cleaner Prod. (2018) 185:588–99. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.226

42.

Ssenyonga R Sewankambo NK Mugagga SK Nakyejwe E Chesire F Mugisha M et al Learning to think critically about health using digital technology in Ugandan lower secondary schools: a contextual analysis. PLoS One. (2022) 17(2):e0260367. 10.1371/journal.pone.0260367

43.

Mudenda S Hikaambo CN Daka V Chileshe M Mfune RL Kampamba M et al Prevalence and factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Zambia: a web-based cross-sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal. (2022) 41(1):1–14. 10.11604/pamj.2022.41.112.31219

44.

Patel M Patel SS Kumar P Mondal DP Singh B Khan MA et al Advancements in spontaneous microbial desalination technology for sustainable water purification and simultaneous power generation: a review. J Environ Manag. (2021) 297:113374. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113374

45.

Fatoye F Gebrye T Fatoye C Mbada CE Olaoye MI Odole AC et al The clinical and cost-effectiveness of telerehabilitation for people with nonspecific chronic low back pain: randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. (2020) 8(6):e15375. 10.2196/15375

46.

Frigerio P Del Monte L Sotgiu A Giacomo CD Vignoli A. Parents' satisfaction of tele-rehabilitation for children with neurodevelopmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Prim Care. (2022) 23:146. 10.1186/s12875-022-01747-2

47.

Del Carpio-Delgado F Romero-Carazas R Pino-Espinoza GE Villa-Ricapa L Núñez-Palacios E Aguilar-Cuevas MM. Telemedicine in Latin America: a bibliometric analysis. EAI Endor Transact Perv Health Tech. (2023) 9(1):1-11.

48.

Aderinto N Olatunji G Kokori E Agbo CE Babalola AE Yusuf IA et al A scoping review of stroke rehabilitation in Africa: interventions, barriers, and research gaps. J Health Popul Nutr. (2025) 44(1):245.

49.

Njoroge M Zurovac D Ogara EA Chuma J Kirigia D. Assessing the feasibility of eHealth and mHealth: a systematic review and analysis of initiatives implemented in Kenya. BMC Res Notes. (2017) 10(1):90.

50.

Fashoto OY Dlamini N Simelane M Ndzinisa D. Mental health burden in Eswatini and the need for the integration of digital technologies: an explanatory review. Medinformatics. (2025).

51.

Kasprowicz J Bacca HG Silva GM Perdona L Reichenbach R Alvarez AG et al Telehealth and chronic diseases in Brazil and the United States: a scoping review. Revista Bioética. (2025) 33:e3912PT.

52.

Seboka BT Yilma TM Birhanu AY. Factors influencing healthcare providers' attitude and willingness to use information technology in diabetes management. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2021) 21(1):24.

53.

Mahmoud K Jaramillo C Barteit S. Telemedicine in low-and middle-income countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:914423.

54.

Kulatunga GG Hewapathirana R Marasinghe RB Dissanayake VH. A review of Telehealth practices in Sri Lanka in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sri Lanka J Bio-Med Inform. (2020) 11(1).

55.

Bezad R Omrani SE Benbella A Assarag B. Access to infertility care services towards Universal Health Coverage is a right and not an option. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22(1):1089.

56.

Camacho-Leon G Faytong-Haro M Carrera K Molero M Melean F Reyes Y et al , editors. A narrative review of telemedicine in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare. (2022)10(8):1361. 10.3390/healthcare10081361

57.

Lestari HM Miranda AV Fuady A. Barriers to telemedicine adoption among rural communities in developing countries: a systematic review and proposed framework. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. (2024) 28:101684.

58.

Parkes P Pillay TD Bdaiwi Y Simpson R Almoshmosh N Murad L et al Telemedicine interventions in six conflict-affected countries in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region: a systematic review. Conflict and Health. (2022) 16(1):64.

59.

CreveCoeur TS Alexiades NG Bonfield CM Brockmeyer DL Browd SR Chu J et al Building consensus for the medical management of children with moderate and severe acute spinal cord injury: a modified Delphi study. J Neurosurg Spine. (2023) 38(6):744-57.

Appendix

Appendix A. Search Strategies by Database.

| Database | Search terms | Limits applied |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“telerehabilitation"[MeSH Terms] OR “telehealth"[MeSH Terms] OR “digital rehabilitation”) AND (“rural” OR “Nepal”) AND (“implementation” OR “barriers”) | English, 2010–2024 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (“tele-rehabilitation” OR “telehealth”) AND (“rural” OR “LMIC” OR “Nepal”) AND (“effectiveness” OR “implementation”) | English, 2010–2024 |

| Embase | 'tele-rehabilitation'/exp AND ‘rural area'/exp AND (‘effectiveness’/exp OR ‘implementation’) | English, 2010–2024 |

| Web of Science | TS = (tele-rehabilitation OR telehealth) AND TS = (rural OR Nepal OR LMIC) AND TS = (implementation OR effectiveness) | English, 2010–2024 |

| CINAHL | (“tele-rehabilitation” OR “telehealth”) AND (“rural” OR “Nepal”) AND (“barriers” OR “facilitators”) | English, 2010–2024 |

Summary

Keywords

behavioral models, digital health, LMICs, Nepal, rural health equity, tele-rehabilitation

Citation

Dhakal A and Chowdhury MS (2026) Tele-rehabilitation in rural Nepal: a systematic review of effectiveness, barriers, and strategic directions for digital health equity. Front. Digit. Health 7:1681313. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1681313

Received

07 August 2025

Revised

17 December 2025

Accepted

30 December 2025

Published

17 February 2026

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Alessandro Giustini, Chair of Master In Robotic Rehabilitation - University San Raffaele, Italy

Reviewed by

Johanna Jonsdottir, Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi Onlus (IRCCS), Italy

Karine Sargsyan, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Dhakal and Chowdhury.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Amrit Dhakal 6310930025@psu.ac.th

ORCID Amrit Dhakal orcid.org/0000-0002-2070-6866 Md Shahariar Chowdhury orcid.org/0000-0003-1321-1176

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.