Abstract

Background:

Prediction models for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) often rely on biochemical markers such as glycated hemoglobin, fasting glucose, or lipid profiles. While clinically informative, these indicators typically reflect established dysglycemia, limiting their value for early prevention. In contrast, psychosocial stress, sleep disturbance, tobacco use, and dietary quality represent modifiable, non-clinical factors that can be observed long before metabolic abnormalities are clinically detectable. Yet most studies examine these factors in isolation or as additive lifestyle scores, overlooking how their interdependencies reorganize in the preclinical phase. A systems-level approach is therefore needed to capture how disruptions in behavioral coherence signal emerging vulnerability.

Methods:

This study develops a dual-analytic framework that integrates Cox proportional hazards models with artificial neural network (ANN) coherence analysis. Using longitudinal data from the UK Biobank (n=15,774; follow-up up to 17 years), we identified non-clinical predictors of incident T2DM and examined how behavioral networks reorganize across health states. Predictors were screened through multivariate survival analysis and mapped into ANN-derived influence matrices to quantify stability, direction, and systemic coherence of relationships among diet, sleep, psychosocial states, and demographics.

Results:

Eighteen significant predictors of T2DM onset were identified. Elevated risk was linked to loneliness, psychiatric consultation, emotional distress, insomnia, irregular sleep, tobacco use, and high intake of processed meat, beef, and refined grains. Protective effects were observed for 7–8 h of sleep, oat and muesli consumption, and fermented dairy. ANN analyses revealed a pronounced breakdown of behavioral coherence in T2DM: foods that stabilized mood in healthy individuals became associated with distress, age and BMI lost their anchoring roles, and emotional states emerged as dominant but erratic drivers of diet. These reversals and destabilizations were consistent across model iterations, suggesting robust signatures of preclinical vulnerability.

Conclusion:

T2DM risk is better conceptualized as systemic reorganization within behavioral networks rather than the additive effects of isolated factors. By combining survival models with ANN-derived coherence mapping, this study demonstrates that early prediction is possible from modifiable, everyday behaviors without laboratory measures. The framework highlights leverage points for psychologically informed, personalized prevention strategies.

1 Introduction

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) is a major global health threat. Hundreds of millions of adults are affected today and the number is projected to rise sharply in coming decades, with a substantial toll in deaths and health spending (1). If not diagnosed or well managed, T2DM leads to serious complications that include kidney disease, vision loss, limb amputation, cardiovascular events, and premature mortality (2). In response, there is a large literature on diabetes risk assessment and prediction.

Despite extensive research, current T2DM prediction, diagnosis, and prevention models continue to exhibit limitations. Most studies specify independent variables such as BMI, smoking status, or dietary habits and estimate their separate effects on incident T2DM, often using additive or risk-score based approaches (3). This design rarely captures interdependence, directionality, or the stability of links among diet, sleep, mood, activity, and demographics (4), and it frequently relies on downstream biomarkers such as HbA1c or fasting glucose that reflect established dysglycemia rather than upstream behavioral precursors (5). In this study, “signal” denotes a detectable pattern of interaction among behavioral variables, “marker” refers to an observable manifestation of this signal in the dataset, and “precursor” describes its appearance prior to deviation in conventional clinical biomarkers.

A study using UK Biobank shows that irregular sleep timing and duration are associated with higher risk of incident T2DM, even among individuals with adequate average sleep; however, sleep was analyzed as a single exposure and several measures were self reported (6). A dose-response meta analysis found that greater total and moderate to vigorous physical activity is linked to lower risk, often beyond the effect of adiposity, although activity was frequently self reported and evaluated in isolation (7). A classic cohort study reported that a composite lifestyle score combining dietary intake, physical activity, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and body weight explained a large share of incident T2DM, but the score was additive by design and did not estimate directionality or stability among these behavioral domains (8).

Recent evidence further indicates that alcohol consumption contributes directly to vascular aging, a process closely linked to insulin resistance, impaired glucose delivery, and broader metabolic dysregulation that precede and contribute to T2DM development (9). Taken together, these studies demonstrate robust single-domain and additive effects of dietary intake, physical activity, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and sleep behavior, but they do not show how relationships among diet, sleep, emotional states, physical activity, and demographic factors reorganize prior to diagnosis. Because T2DM is fundamentally a disorder of metabolic regulation, early risk may manifest not only through isolated behaviors but through loss of coordinated regulation across behavioral and psychosocial domains. In this study, the term behavioral coherence is used to denote the alignment and mutual reinforcement of emotional, dietary, sleep-related, physical activity, and social variables that support metabolic stability over time.

Many machine learning (ML) studies for incident T2DM use static baseline features and prioritize discrimination metrics (e.g., AUC), rather than modeling how behaviors interact; recent reviews of T2DM prediction consistently note this emphasis on performance over structure (10). Post-hoc explainers such as Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) (11) or partial dependence plots (PDPs) (12) add feature-wise attributions, but they do not recover inter-feature influence or its stability; moreover, PDPs can mislead under correlated predictors (13, 14), and SHAP explanations have documented pitfalls (13). Many models also include glycaemic and lipid biomarkers (e.g., HbA1c, fasting glucose, cholesterol), which improves accuracy but shifts modeling toward detection of established dysglycemia rather than preclinical behavioral disruption (15, 16). Broader evidence further shows that ML does not reliably outperform strong statistical baselines and needs better methodology and reporting in clinical prediction (17). This gap highlights the need for more integrative models that look at the whole system, capturing changes in everyday behaviors before diabetes or other metabolic diseases become clinically visible.

To address this gap, this study aims to develop and validate a behavioral framework for T2DM that detects early disruption in behavioral coherence and quantifies how links among sleep, mood, diet, physical activity, and demographics reorganize before clinical dysglycemia appears. We expected that, relative to healthy individuals, those who develop T2DM would exhibit a loss of stable, coherent relationships among these behavioral domains, with emotional and sleep-related states exerting more variable and destabilizing influences on dietary and lifestyle patterns. To test these expectations, a behavioral neural framework was developed and validated using longitudinal data from the UK Biobank.

1.1 Contributions of the study

This study makes four key contributions to the literature on T2DM risk prediction and behavioral modeling, advancing both methodological and conceptual understanding in the domain:

Systems level behavioral risk framework: This study introduces a dual-modeling framework that couples a Cox proportional hazards model with an ANN-based behavioral coherence and network analysis. This hybrid design enables both individual risk estimation and system-level mapping of interaction patterns among diet, emotion, sleep, and lifestyle variables, providing a holistic view of preclinical metabolic vulnerability within the cohort.

Non-biochemical, behavior-centered early risk detection: By excluding laboratory biomarkers and instead using longitudinal psychosocial, dietary, and lifestyle variables, the study demonstrates that accurate T2DM risk prediction is possible from everyday modifiable factors. This shift from biomarker-dependent models to a systems-level behavioral framework highlights how preclinical vulnerability can be detected through disruptions in sleep, mood, diet, and smoking patterns before dysglycemia becomes clinically measurable.

Translating behavioral coherence from concept to measurable patterns: This study advances behavioral coherence from a theoretical construct to a measurable, testable phenomenon. It identifies three reproducible signatures of disruption in T2DM: (i) emotional revaluation of foods, in which dietary items shift from stabilizing to strain-linked; (ii) erosion of demographic anchors, as age and BMI-defined weight status cease to structure behavior predictably; and (iii) instability in state-to-action mappings, reflecting fragmented and less reliable behavioral regulation. Together, these signatures provide an empirical basis for treating behavioral coherence as an early marker of metabolic vulnerability.

From structural disruption to prevention targets: By linking hazard ratios with structural roles in the behavioral network, the framework surfaces leverage points for intervention. Risk-amplifying behaviors such as smoking, processed meat intake, and irregular sleep emerge as destabilizing hubs, while stabilizing patterns such as high-fiber breakfasts and optimal sleep duration appear protective. Although not yet tested in interventions, these system-level priorities provide an evidence-informed foundation for designing psychologically attuned and personalized prevention strategies.

2 Related work

A substantial body of research has examined how clinical, behavioral, and lifestyle factors contribute to the incidence of T2DM (5, 17). Prior studies consistently demonstrate that risk is shaped not only by biological markers but also by everyday routines and psychosocial contexts (18, 19). Factors such as psychological distress and social connection, insomnia, sleep quality and circadian alignment, as well as dietary quality and broader pattern-level effects, have each been investigated in relation to T2DM onset (20–23). The following section reviews the literature to highlight how these domains have been studied, the consistent associations that have emerged, and the gaps that remain.

2.1 Psychological distress and social connection

Many studies have reported that psychological distress, encompassing both subclinical symptoms (e.g., persistent low mood, anxiety, sadness) and clinically diagnosed conditions (e.g., major depressive disorder), is associated with a higher incidence of T2DM. A prospective meta-analysis (24) found that individuals with depression or elevated depressive symptoms at baseline had a 60% higher risk of developing T2DM compared with those without depression, whereas having T2DM only modestly increased the risk of subsequent depression. Beyond clinical diagnoses, chronic psychosocial stressors in daily life have also been linked to elevated risk. An extensive European cohort study involving over 120,000 adults found that job strain was associated with a modest but significant increase in T2DM incidence, independent of lifestyle and demographic factors (25).

Beyond psychiatric symptoms, low or poor social connection, operationalized as loneliness or social isolation rather than social engagement, has emerged as an additional risk signal. For instance, multi-cohort and Mendelian randomization analyses link loneliness and social isolation to higher T2DM incidence across European and East Asian cohorts, with complementary evidence from national registry data (26, 27). Collectively, these studies establish psychological distress and weak social connection as meaningful contributors to T2DM risk. However, they tend to examine such factors independently or combine them into additive scores, overlooking how psychosocial states may dynamically interact with other behaviors such as diet or sleep in the lead up to diagnosis.

2.2 Sleep quality, insomnia, and circadian alignment

Prospective and meta analytic evidence indicates that insomnia symptoms including difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep and non restorative sleep are associated with higher incidence of T2DM, independent of common confounders (28). Primary care cohorts show that poor sleep quality elevates diabetes risk, with insomnia in prediabetes raising progression hazard by about 30% (29).

More recent device-based studies, using wrist-worn accelerometers and actigraphy-derived sleep metrics rather than glucose monitoring, demonstrate that irregular sleep timing and circadian misalignment predict incident T2DM even when total sleep duration is sufficient (30, 31). Experimental studies support these findings by showing that circadian disruption impairs glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, providing biological plausibility linking irregular sleep schedules, insomnia, and metabolic risk (32). In this study, sleep disturbance is operationalized specifically through self-reported insomnia symptoms, allowing us to evaluate its contribution to incident T2DM risk alongside diet and psychosocial factors and to test whether losses of behavioral coherence emerge when sleep regulation is disrupted.

2.3 Diet quality and eating patterns

Poor dietary intake contributes independent predictive value for T2DM. Researchers have found that higher consumption of red meat, particularly processed red meat, is associated with an increased risk of developing T2DM, a relationship confirmed across multiple U.S. cohorts and meta analyses (33). Conversely, higher whole grain intake is linked to lower risk (34), while Mediterranean like dietary patterns relate to reduced incidence and improved cardiometabolic profiles in both observational and intervention contexts (35). However, average main effects mask more nuanced processes. The emotional meaning of foods and the state dependent cues that drive choices may shift under psychosocial load or emerging illness. Moreover, timing of intake and its coupling with sleep patterns are often under measured, obscuring interactions between diet, circadian organization, and psychological state (36). Thus, while dietary risk is well established, its integration with other behavioral domains remains underexplored.

2.4 Integrative gap

Taken together, existing research demonstrates that adverse psychosocial states (e.g., psychological distress, low social connectedness), sleep disturbance, physical inactivity, and poor dietary quality are robustly associated with the incidence of T2DM. Yet most studies evaluate these variables independently, treat them additively in lifestyle scores, or rely heavily on downstream biomarkers. Such approaches clarify what the risk factors are, but not how their relationships reorganize, lose stability, or interact dynamically before clinical onset. The present study addresses this gap by moving from isolated exposures to a systems perspective, embedding these behavioral domains within a multi domain network. This enables us to estimate their incremental contribution to incident risk and to assess whether the relationships among psychosocial states, sleep, diet, and activity show shifts in direction or instability across health states, thereby operationalizing behavioral coherence as an early warning signal for T2DM.

3 Research methodology

This study employed a dual-modeling framework to investigate behavioral precursors of T2DM, integrating predictive risk estimation with systems-level analysis of behavioral coherence.

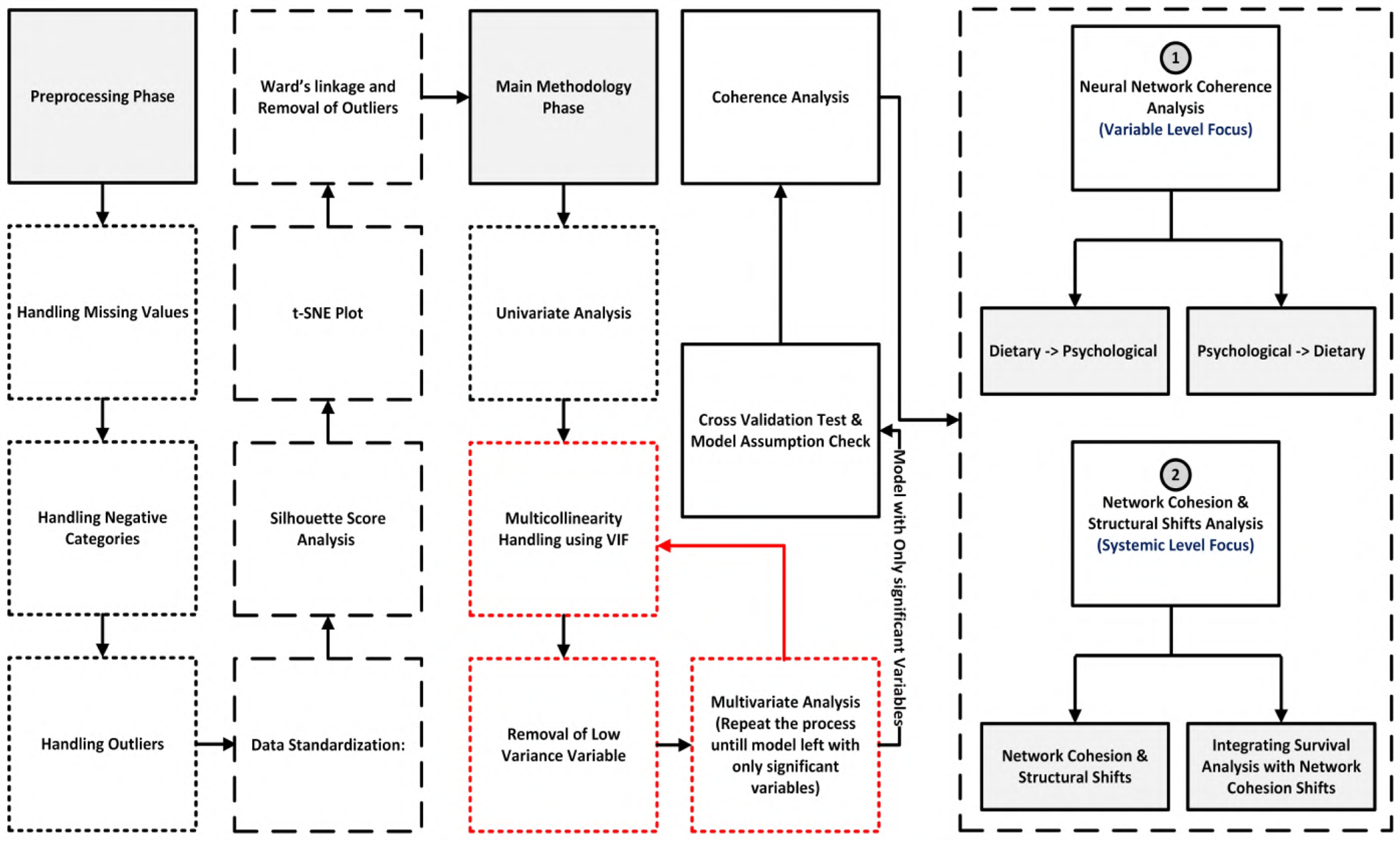

Figure 1shows the overall architecture after data selection, outlining the analytic pipeline from data preprocessing to behavioral interaction mapping. The methodology is organized into four main stages:

Dataset preparation: UK Biobank data were filtered using strict inclusion criteria to support time-to-event analysis (Section 4).

Preprocessing and feature selection: Standardization, imputation, and outlier exclusion were followed by univariate screening and multicollinearity checks (Section 5).

Survival modeling: A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model (37) was used to analyze time to T2DM diagnosis with right censoring and irregular follow-up; its semi-parametric form leaves the baseline hazard unspecified and yields efficiently estimated, clinically interpretable hazard ratios. To ensure robustness, proportional hazards diagnostics and C-index discrimination were assessed, and model stability was evaluated via cross-validation (Sections 6–7).

Neural network analysis and cohesion shifts: Behavioral interactions were modeled separately for diabetic and non-diabetic groups using a feedforward artificial neural network (ANN). Cohesion shifts were then quantified by comparing influence matrices and directional stability across health states (Sections 8–11).

Figure 1

Overall architecture after data selection, outlining the analytic pipeline from data preprocessing to behavioral interaction mapping. The methodology is organized into four stages: (1) preprocessing with quality control, missing-data imputation, and normalization; (2) feature engineering and selection; (3) model training and validation with cross-validation; (4) neural network coherence analysis that maps influences between dietary and psychological variables at the variable level, and (5) system-level network cohesion and structural shift analysis that integrates these changes with the survival results.

This approach enabled both individual risk prediction and detection of systemic behavioral disintegration. Cohesion shifts provided a key signal of emerging metabolic vulnerability, capturing how emotional, psychosocial, and demographic anchors in behavior erode prior to clinical diagnosis.

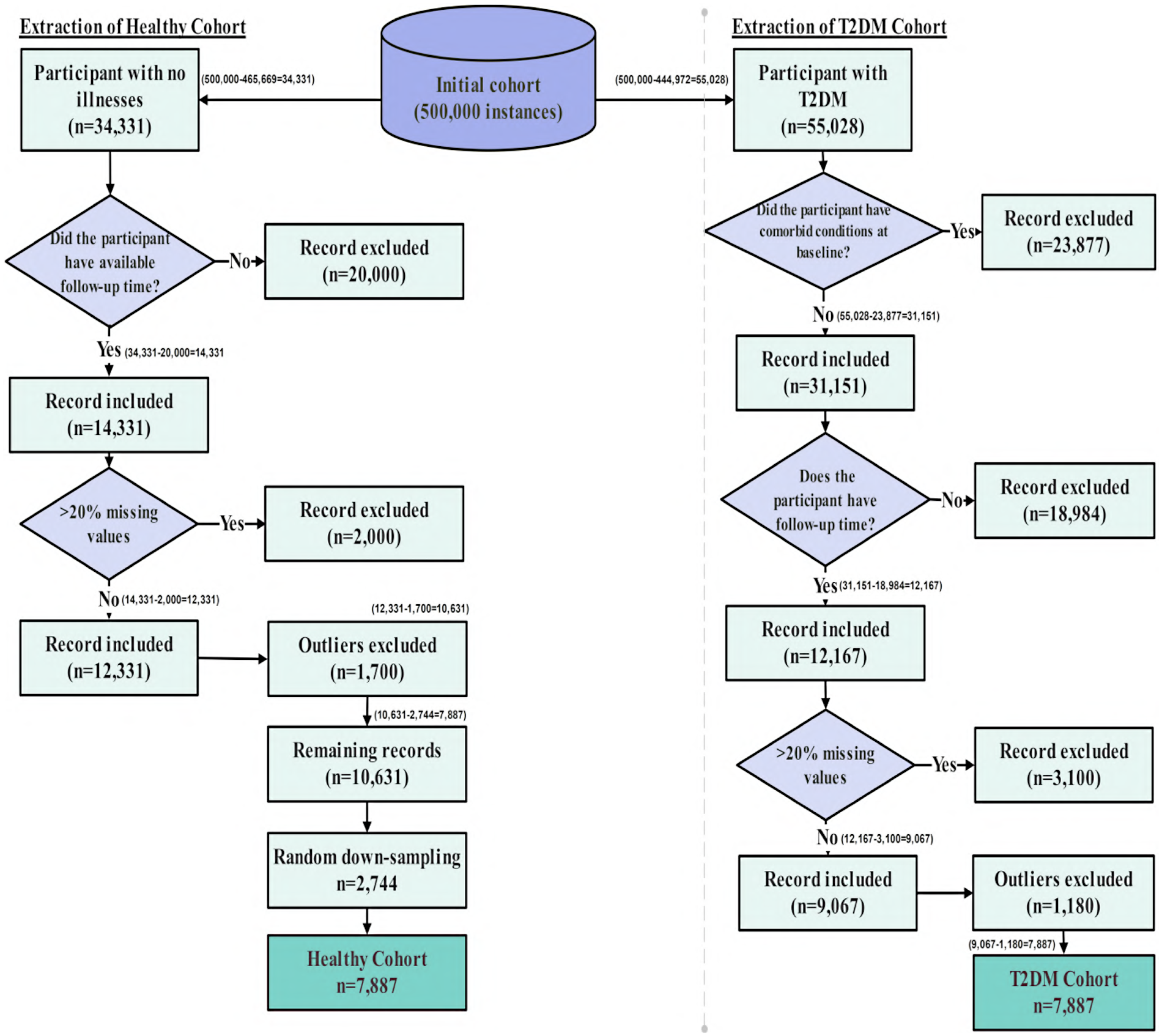

4 Dataset preparation

The dataset was derived from the UK Biobank (38), a prospective cohort of over 500,000 participants aged 40 to 69 at baseline. It included behavioral, psychosocial, demographic, and clinical variables such as validated measures of depression, insomnia, loneliness, self-reported mental health, physical activity, sleep, and diet, which were essential for modeling behavioral pathways and intervention outcomes. To construct the analytic dataset, we first separated participants into two parallel streams: (1) individuals with no record of T2DM, and (2) individuals with evidence of T2DM in linked health records. The full workflow is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Flow diagram of participant selection from the UK Biobank cohort. Starting from approximately 500,000 records, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied separately for T2DM and non-T2DM individuals. Records with comorbid illnesses, >20% missing data, and statistical outliers were excluded. Healthy individuals were randomly down-sampled to match the T2DM sample size. The final analytic dataset included 7,887 participants with T2DM and 7,887 healthy participants.

Healthy stream: The healthy cohort was defined using a strict baseline exclusion criterion. Participants were required to have no recorded chronic disease of any type, including T2DM. Disease status was determined using UK Biobank’s linked clinical records and self-reported medical history, with diagnoses identified via UK Biobank field 41270 (“Diagnoses ICD-10”). Individuals with any record of T2DM (ICD-10 code E11) or any other major chronic illness were excluded. Applying this criterion to the full UK Biobank cohort of approximately 500,000 participants resulted in the exclusion of 465,669 individuals. The remaining 34,331 participants were free of T2DM and all other major chronic diseases at baseline and were therefore designated as the healthy cohort. This group corresponds to the healthy branch shown in Figure 2, prior to follow-up verification, missing-data filtering, and outlier removal.

The rationale for this restriction was to isolate behavioral, dietary, and psychosocial patterns specifically attributable to diabetes rather than to general multimorbidity. Major non-diabetic chronic conditions, including cancer, chronic cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic respiratory disorders, and other long-term illnesses, are known to independently affect physical activity, diet, sleep behavior, and psychological well-being. Including such participants would confound diabetes-specific behavioral signatures with changes driven by unrelated disease processes. Restricting the healthy cohort to genuinely disease-free individuals therefore provided a clean reference group for identifying behavioral reorganization associated with the development of T2DM.

T2DM stream: T2DM was identified using ICD-10 codes E11.0–E11.9 recorded in UK Biobank linked hospital inpatient data, corresponding to Type 2 (non–insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Specifically, these codes include diabetes mellitus with hyperosmolarity (E11.0), ketoacidosis (E11.1), renal complications (E11.2), ophthalmic complications (E11.3), neurological complications (E11.4), peripheral circulatory complications (E11.5), other specified complications (E11.6), multiple complications (E11.7), unspecified complications (E11.8), and diabetes mellitus without complications (E11.9). Using these diagnostic codes, we extracted all participants who had at least one recorded T2DM diagnosis in their linked medical history, resulting in 55,028 individuals. This step therefore excluded approximately 444,972 participants from the original UK Biobank cohort of 500,000 who had no recorded T2DM diagnosis. The figure of 55,028 reflects the initial size of the T2DM stream prior to comorbidity filtering, missing-data screening, or outlier removal, as illustrated in the right-hand branch of Figure 2.

T2DM frequently co-occurs with other long-term illnesses, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disorders, and inflammatory conditions, which can independently influence lifestyle behaviors and psychological outcomes. To isolate behavioral, dietary, and psychosocial patterns specifically associated with T2DM, individuals with major chronic comorbid conditions were excluded, thereby reducing confounding effects from non-diabetes–related illnesses. This approach enabled a more homogeneous T2DM cohort and improved interpretability of downstream behavioral analyses by limiting disease-related heterogeneity. After applying this comorbidity filter, 31,151 individuals remained in the T2DM stream, corresponding to the comorbidity-filtered cohort shown in Figure 2.

4.1 Follow-up time and eligibility for survival modeling

As shown in Figure 2, once the healthy and T2DM streams were established, the next step was to determine which participants had sufficient information to contribute a valid time-to-event interval. To ensure consistency in the survival analysis, both groups were then processed identically through follow-up verification, missing-data exclusion, and outlier removal.

Healthy participants (censored observations): As the goal here was to analyze individuals who were healthy at baseline (UK Biobank field 53) and remained free of T2DM throughout the observation window, follow-up time for these participants was defined from their baseline assessment to the most recent subsequent assessment at which they were still recorded as non-diabetic. Many participants attended a second or third assessment visit; in such cases, the latest visit confirming continued non-diabetic status was used to determine the censoring time. Participants who had no follow-up assessment and no later linked hospital records could not provide a verifiable time interval during which they were known to remain healthy, and were therefore excluded. After applying this criterion, 14,331 healthy participants had valid follow-up time.

Participants who developed T2DM (event observations): As outlined above, incident T2DM was identified using ICD-10 codes E11.1-E11.9. These diagnoses are captured in UK Biobank’s linked Hospital Episode Statistics dataset, where field “130708” records the exact date on which an E11 diagnosis was first documented. For each participant, follow-up time was calculated as the interval between the baseline assessment and this first diagnosis date provided the diagnosis occurred after baseline. This method produces valid survival times even for individuals who never returned for a second assessment visit, because their diagnosis date is captured through hospital linkage. After applying this rule, 12,167 T2DM participants had a valid event time.

This approach ensures that all individuals included in the survival model have a clearly defined period during which they were at risk, thereby preventing misclassification of event or censoring times and improving the accuracy of the hazard estimates. After establishing valid follow-up times, we next applied the missing-data and outlier exclusion criteria to the 14,331 healthy records and 12,167 T2DM records retained at this stage.

5 Data preprocessing and feature selection

To ensure data integrity and analytical robustness, several preprocessing steps were undertaken. Clinical biomarker variables (e.g., glucose, HbA1c, and cholesterol) were intentionally removed at the outset to focus the analysis on modifiable, non-clinical behavioral and psychosocial predictors. Although glycaemic and lipid biomarkers are clinically actionable and may be intervened upon at sub-clinical levels (5), their inclusion would shift the modeling task toward detection of emerging dysglycemia rather than the identification of earlier behavioral system disruption. The aim of this study was therefore not to replace biomarker-based risk assessment, but to examine whether vulnerability to T2DM can be detected through changes in everyday behavioral regulation prior to laboratory abnormalities becoming apparent.

Following this conceptual scoping of predictors, standard data-quality preprocessing procedures were applied to prepare the analytic dataset. Records (rows) with more than 20% missing data were excluded. This threshold reflects common pragmatic practice in epidemiological and machine-learning analyses to balance data completeness with sample retention, and to limit bias, instability, and loss of efficiency associated with extensive missingness and unreliable imputation (39–41). Applying this threshold to the 14,331 healthy participants with valid follow-up removed 2,000 records, leaving 12,331 healthy individuals. Likewise, from the 12,167 participants with incident T2DM, 3,100 records exceeded the missing-data threshold and were removed, resulting in 9,067 T2DM participants.

For the remaining missing values, categorical responses such as “Don’t know” and “Prefer not to answer” were coded as Not a Number (NaN) and imputed using mode imputation for categorical variables, mean imputation for continuous variables, and the least frequent category for binary fields. Negatively coded responses (e.g., 7 for “None of the above”) were recoded to maintain logical ordering.

5.1 Outlier handling and detection

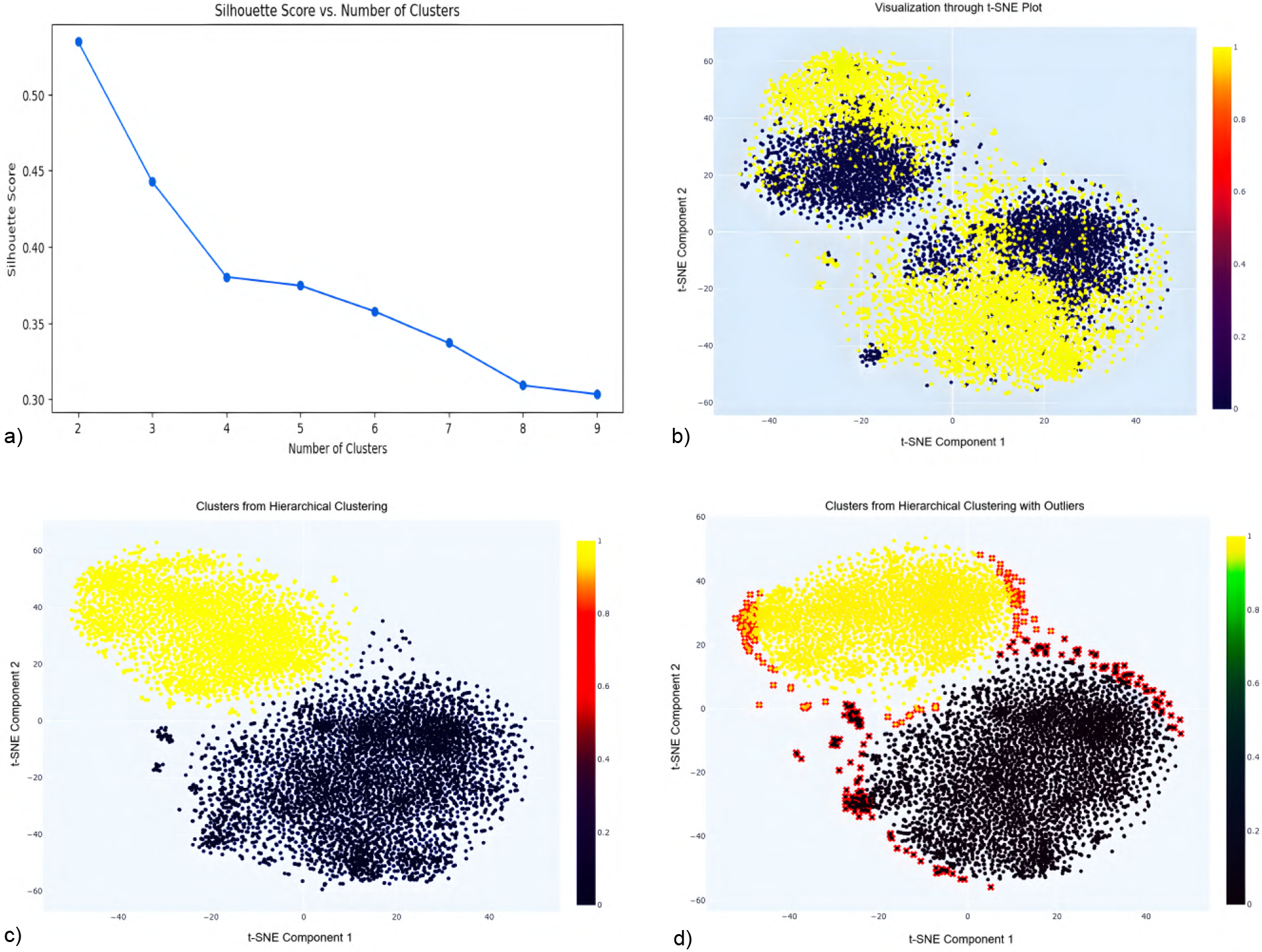

Following missing-data filtering and imputation applied only to records with limited missingness (<20%), outlier handling was performed to address structurally inconsistent behavioral profiles that could distort multivariate relationships and bias survival estimates. Unlike missingness, which was addressed through targeted value-level imputation when limited, outliers were handled using a full-case removal strategy, as adjusting extreme values can disrupt inter-variable dependencies and obscure system-level structure. Entire records identified as outliers were therefore removed to preserve multivariate integrity and ensure stable estimation in subsequent Cox proportional hazards models. Outlier detection was performed prior to supervised modeling to avoid data leakage. Figure 3 illustrates the full outlier detection workflow, from optimal cluster selection to identification of peripheral observations removed from the dataset.

Figure 3

Silhouette score analysis (a) indicates optimal clustering at k=2. The t-SNE projection (b) visually separates these clusters, highlighting outliers at the data margins. Hierarchical clustering using Ward’s linkage (c) refines cluster integrity, while final visualization (d) reveals peripheral outliers (red) subsequently removed to enhance data quality and improve model robustness. (a) Silhouette score vs. No. of clusters. (b) Visualization through t-SNE Plot. (c) Clusters from hierarchical clustering. (d) Clusters with outliers highlighted.

5.1.1 Outlier detection pipeline

A multi-step unsupervised procedure was applied to identify and eliminate structurally inconsistent data points, creating a stable dataset for analysis while maintaining a balance between generalizability and internal validity.

Data standardization: All features were standardized to a mean of zero and standard deviation of one to ensure equal contribution, especially for algorithms like t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) (42), which are sensitive to feature scale.

Optimal cluster selection via Silhouette score: Silhouette analysis (43) was used to evaluate clustering quality, with the highest score at , indicating optimal cluster separation (see Figure 3a).

t-SNE visualization: t-SNE was applied to project the dataset into two dimensions using a perplexity of 40 and 5,000 iterations. It was chosen over principal component analysis (PCA) (44) because it more effectively preserved local neighborhood structures in the data used in this study, which facilitated clearer cluster separation and outlier detection. The resulting two-dimensional projection revealed two distinct clusters corresponding to the binary target variable, along with peripheral points that may represent outliers (see Figure 3b).

Hierarchical clustering: Ward’s linkage method (45) was used on the t-SNE components, producing well-separated clusters with minimized intra-cluster variance (see Figure 3c).

- Outlier identification and removal:

Outliers were identified based on their Euclidean distance from the centroid of their respective clusters:

Centroid calculation: Centroids of each cluster in t-SNE space were computed.

Distance measurement: Euclidean distances between each data point and its cluster centroid were calculated.

Thresholding: Points beyond the 95th percentile of these distances were flagged as outliers.

Visualization and removal: Outliers were marked in red in Figure 3d and subsequently removed to avoid skewing the analysis.

This systematic pipeline ensured the removal of structurally inconsistent data points, resulting in improved cluster cohesion and enhanced analytical integrity. Although this approach strengthens internal validity and reduces model bias, it necessarily involves a trade-off in external generalizability, as the removal of extreme cases may reduce representation of certain subpopulations. Nonetheless, for time-to-event modeling and simulation purposes, this trade-off was deemed acceptable to support stable and unbiased survival estimation. Applying the pipeline to the UK Biobank cohorts removed an additional 1,700 outliers from the healthy cohort and 1,180 from the T2DM cohort, reducing the samples from 12,331 to 10,631 and from 9,067 to 7,887 participants, respectively, forming the pre-balanced cohorts used in the subsequent survival analysis.

5.2 Final analytic cohort derivation

After establishing valid follow-up times and completing the missing-data and outlier filtering steps described above, the resulting healthy and T2DM cohorts were carried forward to the final stage of cohort construction. Because the healthy pool remained substantially larger than the T2DM cohort after preprocessing (10,631 vs. 7,887), random down-sampling was applied to the healthy group to achieve matched sample sizes. Sampling was performed without conditioning on any predictor variables, ensuring that the procedure was independent of demographic, dietary, psychological, and lifestyle characteristics. Although this step alters the observed prevalence of T2DM relative to the full UK Biobank population, random selection preserves marginal structure in expectation. This balanced dataset was used exclusively for model training rather than for estimating population-level prevalence. Because Cox proportional hazards estimation relies on time-to-event information through the partial likelihood rather than outcome prevalence, altering class proportions through random down-sampling does not bias hazard ratio estimation or survival time interpretation (46–48).

As shown in Figure 2, the final analytic dataset consisted of two equal groups of 7,887 participants each: one comprising individuals who were healthy at baseline but later developed T2DM during follow-up (T2DM cohort), and one comprising individuals who maintained a non-diabetic status across all available observations (Healthy cohort). Time-to-event durations ranged from 1 to 17 years, providing sufficient longitudinal variability for stable and unbiased survival estimation.

6 Survival modeling and risk identification

This section outlines the Cox modeling pipeline, covering variable screening, multicollinearity control, proportional hazards testing, and model validation, followed by interpretation of significant predictors forming the basis for simulation and intervention in the DT system.

6.1 Cox model development and validation

A penalized Cox proportional hazards model (37) was employed to estimate T2DM onset risk. The model simultaneously identified significant predictors and generated time-sensitive risk estimates, enabling personalized simulation. The hazard function is given in Equation 1:where is the hazard at time , is the baseline hazard, and represents the hazard ratio (HR) for predictor .

6.1.1 Univariate analysis

To identify predictors of diabetes onset, univariate Cox proportional hazards regression was performed for each variable, modeling time to T2DM onset as a function of a single predictor. Statistical significance was assessed using p-values, with variables meeting the threshold of retained for multivariate analysis. Categorical predictors were transformed into dummy variables to enable inclusion in the Cox framework while minimizing multicollinearity. It should be noted that univariate screening was used solely as an initial dimensionality reduction step and not as a criterion for final variable selection, which was determined in the multivariate modeling stage.

To improve stability and interpretability of the final model, two quality control procedures were applied. First, dummy variables with low variance across the dataset or within subgroups stratified by event status were excluded to prevent unstable coefficient estimates. Second, multicollinearity was addressed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), defined as , where is obtained by regressing predictor on all other predictors. Variables with were removed, consistent with established guidelines (49).

From 90 features evaluated, 27 were initially significant in univariate analysis. Following variance and multicollinearity screening, only robust, independent, and reliable predictors were advanced to the multivariate Cox model, ensuring improved validity and generalizability of results.

6.1.2 Multivariate analysis

After univariate screening, all candidate predictors were entered simultaneously into an initial multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to evaluate their joint effects on time to T2DM onset. This approach explicitly accounts for interdependencies among predictors and allows effect estimates to change in the presence of other variables. The 27 features identified in univariate analysis were included in the initial model, and several predictors lost significance once confounding and shared variance were accounted for. Variable retention was determined using an iterative stepwise procedure, with predictors removed only when they contributed no independent explanatory value after joint adjustment and exhibited redundancy or instability.

Because removing correlated predictors can alter estimated coefficients, statistical significance alone was not treated as sufficient justification for exclusion. Variables were removed only when they contributed no incremental explanatory value in the multivariable context and exhibited redundancy or instability due to shared variance (supported by VIF screening) or low-variance categories yielding unreliable estimates. This process reduced the predictor set from 27 to 18, underscoring the importance of joint modeling rather than variable-by-variable selection. As a sensitivity check, models were refit retaining theoretically supported covariates, and the direction and magnitude of key predictors as well as the overall conclusions remained unchanged. The final reduced predictor set was then used consistently in both the Cox survival model and the ANN analysis to ensure comparability between individual risk estimation and system-level interaction modeling.

The coefficients () represent adjusted hazard ratios, quantifying the relative risk of T2DM onset associated with each predictor while holding other factors constant. For instance, a dietary factor with a hazard ratio greater than 1 indicates an increased risk of T2DM independent of demographic or lifestyle covariates. This stepwise refinement enhanced both interpretability and robustness, yielding a final model focused on key predictors that reliably contribute to T2DM risk.

6.1.3 Proportional hazards assumption

Following multivariate modeling, the proportional hazards assumption was evaluated to ensure the validity of the Cox regression framework. This assumption requires that the effect of each covariate on the hazard remains constant over time, implying that hazard ratios are time-invariant. For example, if higher physical activity reduces diabetes risk by 30% (hazard ratio=0.70), this relative effect is expected to persist throughout the follow-up period.

The proportional hazard assumption was assessed using diagnostic methods based on Schoenfeld residuals (50). Violations can bias hazard ratio estimates; therefore, corrective strategies were applied when necessary. Two approaches were implemented: (i) stratification, allowing the baseline hazard to vary across covariate strata, and (ii) incorporation of time-dependent covariates to capture changing effects over time. In this study, non-proportionality was detected for cooked vegetable intake and long-standing illness, both of which were modeled with covariate–time interactions to preserve validity and interpretability. These adjustments enabled the model to accommodate dynamic predictor effects, thereby enhancing explanatory accuracy while preserving the validity of the proportional hazard assumption.

6.1.4 Internal validation

Model performance was evaluated using 10-fold stratified cross-validation, training on nine folds and testing on the tenth (51). Stratification preserved the distribution of diabetes onset and censored cases across folds. L2 regularization reduced overfitting by penalizing large coefficients (52). Performance was measured with the concordance index (C-index) (53), yielding a mean of 0.90 (SD=0.004), indicating excellent accuracy and consistency. The model was then refitted on the full dataset to maximize information, and the proportional hazards assumption was re-verified, confirming the stability and reliability of the final model.

7 Results and interpretation of significant predictors

This section presents the findings from the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, emphasizing their implications for disease prediction, behavioral interventions, and dietary profiling in T2DM risk. The model highlights the interplay of psychosocial stressors, sleep patterns, dietary choices, and demographic factors in shaping T2DM risk. Several modifiable, non-clinical variables, including mental well-being, sleep behavior, and specific dietary components, emerged as significant predictors. Table 1 summarizes the selected predictors along with their coefficients (), hazard ratios , percentage change in hazard (HR%), confidence intervals, and p-values. HR% was calculated as , and values are rounded consistently.

Table 1

| Risk factors | HR (%) | p | 95% CI for | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Loneliness isolation | 0.13 | 1.14 | 14.00 | 1.07 | 1.21 | |

| Seen a psychiatrist | 0.16 | 1.18 | 18.00 | 1.09 | 1.27 | |

| Sleeplessness insomnia | 0.06 | 1.06 | 6.00 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 1.12 |

| Fed up feelings | 0.08 | 1.08 | 8.00 | 1.02 | 1.14 | |

| Tense highly strung | 0.15 | 1.17 | 17.00 | 1.10 | 1.25 | |

| Sleep duration 7–8 h | 0.13 | 0.87 | 13.00 | 0.82 | 0.93 | |

| Nap during day | 0.09 | 1.10 | 10.00 | 1.01 | 1.20 | |

| Difficulty getting up in morning | 0.04 | 1.04 | 4.00 | 1.01 | 1.08 | |

| Plays computer games | 0.04 | 1.04 | 4.00 | 1.01 | 1.07 | |

| Smoking status (Previous smokers) | 0.12 | 1.13 | 13.00 | 1.07 | 1.19 | |

| Smoking status (Current smokers) | 0.17 | 1.19 | 19.00 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 1.38 |

| Current tobacco smoking | 0.29 | 1.34 | 34.00 | 1.14 | 1.58 | |

| Salt added to food | 0.04 | 1.05 | 5.00 | 1.02 | 1.08 | |

| Cheese intake | 0.05 | 0.94 | 6.00 | 0.92 | 0.96 | |

| Brown bread | 0.16 | 1.18 | 18.00 | 1.09 | 1.27 | |

| White bread | 0.26 | 1.30 | 30.00 | 1.18 | 1.43 | |

| Other type of bread | 0.11 | 1.11 | 11.00 | 0.07 | 0.98 | 1.26 |

| Processed meat intake (Less than once a week) | 0.07 | 1.07 | 7.00 | 0.15 | 0.97 | 1.19 |

| Processed meat intake (Once a week) | 0.05 | 1.05 | 5.00 | 0.29 | 0.95 | 1.17 |

| Processed meat intake (2–4 times a week) | 0.06 | 1.06 | 6.00 | 0.21 | 0.96 | 1.18 |

| Processed meat intake (5–6 times a week) | 0.17 | 1.18 | 18.00 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 1.38 |

| Beef intake | 0.16 | 1.18 | 18.00 | 1.08 | 1.29 | |

| Biscuit cereal | 0.10 | 1.11 | 11.00 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 1.21 |

| Oat cereal | 0.23 | 0.79 | 21.00 | 0.73 | 0.85 | |

| Muesli | 0.55 | 0.57 | 43.00 | 0.52 | 0.63 | |

| Sugary cereal | 0.10 | 1.11 | 11.00 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 1.21 |

| Age_[50–59] | 0.06 | 0.93 | 7.00 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.14 |

| Age_[60–70] | 0.42 | 1.52 | 52.00 | 1.24 | 1.87 | |

| BMI_[25–29.9]_Overweight | 0.71 | 0.49 | 51.00 | 0.39 | 0.60 | |

| BMI_[30–34.9]_Obesity class I | 0.08 | 1.08 | 8.00 | 0.40 | 0.88 | 1.33 |

| BMI_[35–39.9]_Obesity class II | 0.43 | 1.54 | 54.00 | 1.26 | 1.89 | |

| BMI_[40-50]_Obesity class III | 0.58 | 1.79 | 79.00 | 1.45 | 2.20 | |

Final selected variables and corresponding hazard ratios for T2DM risk. Reference categories are detailed in the table note.

Psychosocial, sleep-related, and behavioral predictors were modeled as binary variables. Salt added to food was treated as an ordinal variable. Processed meat intake, beef intake, bread type, cereal type, age, and BMI were modeled as categorical variables using dummy coding. Reference categories were: Processed meat intake=never; Beef intake=never; Bread type=wholewheat bread; Cereal type=bran cereal; Age=40–49 years; BMI=18.5–24.9 kg/ (normal weight).

Although several candidate variables have strong theoretical and empirical links to T2DM risk, such as alcohol consumption and physical activity (9, 54, 55), inclusion in the final model reflects their independent contribution in the multivariate context rather than on prior evidence alone. As described above, all candidate predictors were initially screened and evaluated jointly in multivariate modeling. Variables were excluded from the final model if they showed no independent association after adjustment, exhibited redundancy due to shared variance, had low variance or sparse response distributions leading to unstable estimates, or exceeded predefined preprocessing thresholds. For example, alcohol consumption and physical activity-related variables were evaluated but did not retain independent explanatory value after adjustment for correlated behavioral and psychosocial factors and were therefore not included in Table 1. This approach prioritizes model stability and interpretability while acknowledging the broader theoretical relevance of excluded factors.

To ensure transparency in variable interpretation, all predictors were coded in accordance with their native UK Biobank structures using binary or dummy-coded categorical variables to maintain interpretability and consistency within the Cox regression framework. Psychosocial, sleep-related, and behavioral exposures (e.g., loneliness, daytime napping, insomnia) were treated as binary indicators. Dietary variables with multiple intake-frequency levels were represented through mutually exclusive dummy variables, with the lowest-consumption category serving as the reference.

Specifically, “Salt added to food” is an ordinal variable with four levels (never/rarely, sometimes, usually, always). In the multivariate Cox model, these levels exhibited highly similar effect sizes and several were non-significant; therefore, the overall ordinal effect was retained and reported as a single hazard ratio. In contrast, processed meat intake comprises six ordered categories (never, less than once per week, once per week, 2–4 times per week, 5–6 times per week, daily) and these levels demonstrated distinct risk gradients. All categories were included as dummy variables with “never” as the reference, although only the 5–6/week category remained significant in the final model.

Beef intake is recorded on the same frequency scale, but only the highest consumption level (5/week or daily) retained statistical significance following stepwise model refinement and is therefore presented with “never” as the reference. Body mass index (BMI) was modeled using WHO-standard categories. The underweight category (<18.5 kg/) contained too few participants for stable estimation and was therefore excluded; normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/) served as the reference category for all BMI contrasts. Age on the other hand was modeled using UK Biobank decadal categories (40–49, 50–59, 60–70 years), with 40–49 years defined as the reference group; this approach captures non-linear age-related risk gradients without imposing parametric assumptions.

This coding strategy preserves fidelity to UK Biobank variable structure while ensuring that only categories contributing independent explanatory value are retained in the multivariate model.

7.1 Psychosocial stressors and sleep behavior

Psychological strain was consistently associated with elevated T2DM hazard. Loneliness or social isolation, psychiatric consultation, and emotional distress were each associated with a 14%–18% increase in hazard, while frequent feelings of being fed up were associated with an 8% increase. Sleep-related factors also contributed independently. Insomnia symptoms and difficulty waking were associated with 6% and 4% higher hazard, respectively, and daytime napping with a 10% increase. In contrast, habitual sleep duration of 7–8 h per night was associated with a 13% lower hazard, indicating a protective association of adequate sleep duration.

Importantly, this protective association with sleep duration was observed alongside indicators of sleep disturbance and psychosocial stress, suggesting that aspects of sleep regulation beyond duration may be relevant for metabolic risk. Consistent with prior evidence, psychosocial stress and circadian disruption have been shown to impair glucose regulation through neuroendocrine and inflammatory pathways, underscoring the relevance of behavioral and chronobiology-informed interventions (56).

7.2 Dietary habits and composition

Dietary patterns showed strong yet heterogeneous associations with T2DM. High beef intake (5 servings/week) was associated with an 18% higher hazard, consistent with previous links between red meat and metabolic dysfunction (57). Processed meat intake showed mixed results: only individuals consuming processed meats 5–6 times per week had a significantly higher hazard (18%), while lower intake frequencies were not statistically significant. Adding salt to food, measured as an ordinal self-reported behavior (never/rarely to always), was associated with a modest 5% increase in hazard. In contrast, cheese intake was associated with a 6% lower hazard, possibly due to vitamin K2 and other bioactive components in fermented dairy that improve insulin sensitivity and glucose regulation (58).

These dietary variables represent key modifiable factors and serve as critical leverage points for targeted dietary interventions. Grain-based foods revealed notable contrasts. Brown bread was associated with an 18% higher hazard compared with the reference category of wholewheat bread, suggesting that not all breads confer equal benefits. Notably, white bread showed a stronger association with elevated risk, with approximately a 30% higher hazard relative to wholewheat bread. This pattern suggests that consumption of more refined grain products may be associated with higher T2DM risk within this cohort, consistent with prior prospective and meta-analytic evidence (54). Cereal types also diverged: muesli and oats reduced hazard by 43% and 21%, respectively, whereas sugary cereals and biscuit-type cereals increased hazard by 11%. These findings emphasize that foods within the same category may exert opposite metabolic effects depending on type and processing (59).

7.3 Smoking behavior

Smoking demonstrated a clear gradient of hazard compared with never smokers: Former smokers had a 13% higher hazard, current smokers 19%, and individuals actively smoking tobacco at baseline 34%. These findings are consistent with prior evidence that both historical and current exposure exert lasting metabolic burdens (60). In this study, smoking status captured lifetime history (never, previous, current), while current tobacco smoking reflected active use at baseline. Their joint inclusion highlights that the long-term metabolic hazards from past smoking differ from the acute hazards of ongoing exposure, enabling models to better distinguish historical vs. modifiable behaviors and refine predictions of individual hazard trajectories and intervention timing.

7.4 Age and BMI

Age showed a clear gradient in T2DM hazard. Adults aged 60–70 years had a 52% higher hazard compared with the reference group of 40–49 years, while those aged 50–59 years showed a non-significant 7% lower hazard. Body mass index (BMI), categorized according to WHO classification (61), demonstrated heterogeneous associations with T2DM risk. Overweight individuals (BMI 25–29.9 kg/) exhibited a 51% lower hazard compared with the normal-weight reference group, a counterintuitive pattern sometimes described as the “metabolically healthy overweight” phenomenon (62). Importantly, BMI reflects body mass relative to height and does not directly measure adiposity or body fat distribution; therefore, these findings should not be interpreted as evidence of lower adiposity among individuals classified as overweight. The apparent protective association may reflect survivor bias, reverse causation, residual confounding, or differences in fat distribution and metabolic profile that are not captured by BMI alone (63). In contrast, obesity class I (BMI 30–34.9 kg/) was not significantly associated with T2DM hazard, whereas obesity class II (BMI 35–39.9 kg/) and class III (BMI 40–50 kg/) were associated with substantially higher hazards of 54% and 79%, respectively. These results highlight the increasing metabolic risk associated with higher BMI categories, particularly at more severe levels of obesity.

To summarize, the Cox model identifies psychosocial stress, sleep behavior, diet, smoking, and BMI as key determinants of T2DM hazard. Modifiable lifestyle factors, including mental well-being, sleep quality, and dietary composition, emerged as critical intervention targets. The findings also highlight heterogeneity within BMI categories, with obesity driving substantial increases in hazard while overweight status shows more complex effects, reflecting the importance of fat distribution and metabolic health. Overall, prevention efforts should adopt an integrated approach that considers psychological, behavioral, and physiological factors to more effectively reduce T2DM hazard.

7.5 Risk score derivation and group stratification

Following internal validation of the multivariate Cox model, individual risk scores were computed to quantify each participant’s relative susceptibility to T2DM onset. The risk score for participant was defined as the model’s linear predictor as shown in Equation 2:where are the coefficients estimated from the final multivariate Cox proportional hazards model (Table 1), and represents the participant-specific value for predictor . Categorical predictors were represented using dummy variables, with reference categories specified in Table 1. The resulting score provides an interpretable log-relative hazard reflecting the combined contributions of behavioral, psychosocial, sleep-related, dietary, and demographic factors.

Because the linear predictor is continuous, a supervised discretization procedure was applied to generate clinically interpretable strata. A decision tree classifier (64) was trained using the risk score as the sole input and observed T2DM incidence as the target outcome. To balance interpretability and discriminatory performance, the tree was constrained to five leaf nodes and trained using 10-fold cross-validation, with the resulting split points fixed and applied uniformly to all participants. These thresholds defined the score ranges for the very low (1.67 to 0.22), low (0.23 to 0.40), moderate (0.41 to 0.70), high (0.71 to 1.11), and very high (1.12 to 2.75) risk strata.

For transparency, two illustrative calculations demonstrate how the linear predictor maps to the final risk strata. Consider an individual who reports loneliness , a habitual sleep duration of 7–8 h , and regular muesli consumption , with all remaining predictors fixed at their reference levels. The corresponding linear predictor is therefore , which falls within the Very Low risk category. As a contrasting example, an individual exhibiting loneliness , daytime napping , current smoking , sugary cereal intake , and membership in the 60–70 year age group yields a linear predictor of , corresponding to the High risk category. These examples illustrate how specific combinations of behavioral and demographic variables translate into distinct diabetes risk classifications.

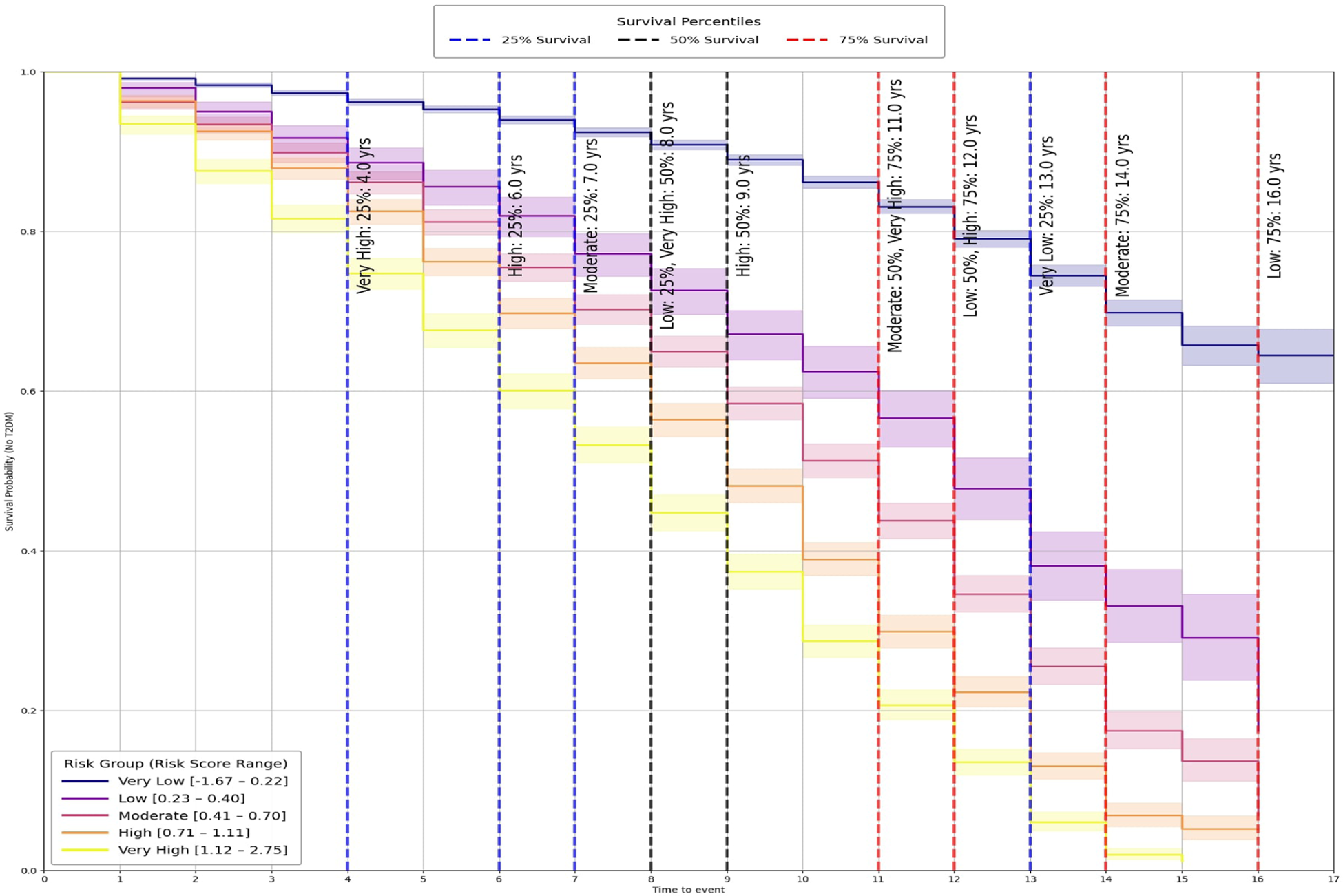

7.6 Validation of risk groups

The predictive utility of these groups was evaluated using Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival analysis (65), which revealed clear, progressive separation across categories (Figure 4). Pairwise log-rank tests (66) further confirmed that differences between groups were statistically significant (, Table 2a), demonstrating that the stratification captures both major and incremental variations in diabetes onset risk.

Figure 4

Kaplan-Meier survival curves by risk group.

Table 2

| (a) Pairwise log-rank test results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Test statistic | p-value | ||

| Very low vs very high | 5255.49 | |||

| Very low vs high | 3662.31 | |||

| Very low vs moderate | 2072.38 | |||

| Low vs very high | 409.51 | |||

| Moderate vs very high | 353.93 | |||

| Very low vs low | 517.59 | |||

| Low vs high | 189.67 | |||

| Moderate vs high | 95.38 | |||

| High vs very high | 89.86 | |||

| Low vs moderate | 46.71 | |||

| (b) Survival time percentiles by risk group | ||||

| Risk group | Score range | 25% | 50% | 75% |

| Very low | [1.67, 0.22] | 13.00 | ||

| Low | [0.23, 0.40] | 8.00 | 12.00 | 16.00 |

| Moderate | [0.41, 0.70] | 7.00 | 11.00 | 14.00 |

| High | [0.71, 1.11] | 6.00 | 9.00 | 12.00 |

| Very high | [1.12, 2.75] | 4.00 | 8.00 | 11.00 |

Panel (a) reports pairwise log-rank test outcomes: Comparison shows the two groups tested, Test Statistic is the log-rank value, and p-value indicates significance. Panel (b) shows survival time percentiles for each group, with Score Range defining the risk category and 25%, 50% (median), and 75% giving survival times in years.

“” denotes that survival did not fall below the percentile threshold during follow-up.

To provide clinically interpretable timelines, survival percentiles were also computed (Table 2b). Individuals in the Very High group reached 25% incidence by year 4 and 75% by year 11, whereas the Very Low group crossed the 25% threshold only after 13 years and did not reach higher incidence levels during follow-up.

Taken together, this stratification highlights the practical utility of the digital twin framework beyond statistical validation. By translating continuous outputs from the Cox model into discrete, time-sensitive categories, the system provides thresholds that can inform clinical decision-making and public health planning. These findings show that psychosocial and behavioral risk factors can be structured into groups that are both statistically distinct and clinically meaningful, reinforcing the value of this framework for individualized prevention and population-level screening.

8 From individual risk to system-level dynamics

While the Cox model identifies which individual variables increase or reduce the hazard of T2DM, it does not reveal how these same variables interact with one another or how broader behavioral–dietary systems reorganize as the disease develops. Many risk factors do not operate in isolation but influence and reinforce each other through emotional, lifestyle, and dietary pathways (67, 68). To understand not only who is at greater risk but also how behavioral regulation changes once T2DM emerges, we therefore extend the analysis using an ANN-based coherence framework. This approach complements the Cox model by mapping variable-to-variable influence patterns, quantifying structural shifts in behavioral cohesion, and identifying which predictors function as network hubs, bridges, or feedback drivers in the chronic-disease state. In this way, the ANN analysis adds a systems perspective to the survival model by linking hazard ratios to each variable’s systemic role within the broader behavioral-emotional-dietary network.

The remainder of this section outlines the ANN architecture, the preprocessing steps applied to ensure comparability with the Cox model, and the methodological procedures used to derive and interpret influence matrices. This approach prepares the groundwork for the network cohesion and interaction mapping discussed later in the manuscript.

8.1 Neural network architecture

The ANN comprised two hidden layers with Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activations, selected for their effectiveness in modeling complex non-linear relationships while mitigating vanishing gradient problems (69, 70). The first hidden layer contained 64 neurons and the second 32 neurons, with L2 regularization applied to the latter to reduce overfitting and enhance generalization (71). The output layer was configured according to prediction type: a sigmoid activation with binary cross-entropy loss for binary targets, a linear activation with mean squared error loss for continuous targets, and a softmax activation with sparse categorical cross-entropy loss for categorical targets (72, 73). Model training employed the Adam optimizer, chosen for its adaptive learning rates and favorable convergence properties (74).

8.2 Data stratification and preprocessing

After survival modeling and variable selection, the dataset was stratified into individuals who developed T2DM during follow-up and those who remained non-diabetic for system-level comparison. Outcome labels and time-dependent variables were excluded prior to ANN training to prevent target leakage and ensure that learned representations reflected predictor–predictor relationships rather than implicit outcome information, consistent with recommended machine learning practice (41, 75). Continuous predictors such as BMI and age were scaled to the [0,1] range using min–max normalization to improve numerical stability and convergence during training (76).

For the Cox model, variables including BMI, age, and smoking status were categorized to support hazard ratio interpretation and maintain epidemiological conventions. In contrast, for the ANN, BMI and age were kept as continuous predictors to retain informational resolution and allow non-linear relationships to be learned, while smoking status was collapsed into a binary indicator. This binarization reflects the dominant contrast in smoking-related risk, which is current or former exposure vs. no exposure. It also reduces the impact of sparse subgroups while preserving the underlying risk pattern that is most informative for ANN learning. Binary encoding and one-hot representations were selected according to the measurement scale and distribution of each variable, following standard guidance for handling categorical and ordinal predictors in neural network models (41, 77).

Dietary variables were processed according to their original UK Biobank structures and the number of meaningful levels retained following Cox model selection. Processed meat intake and beef intake were recorded on six-level ordered frequency scales. Because only the highest consumption levels (processed meat 5–6 times per week; beef 5 servings per week) showed distinct effects and the remaining categories were sparsely populated, these variables were collapsed into binary indicators for the ANN. The highest-intake category was contrasted against all lower levels, with “never” serving as the reference for ANN inputs. Collapsing sparse ordinal categories into binary contrasts is a common strategy to reduce noise and improve model stability when extreme exposure levels drive effects (41).

Bread type and cereal type differed fundamentally from the meat variables, as they represent nominal, mutually exclusive food categories rather than ordered frequency levels. Their categories reflect qualitatively distinct products rather than increasing amounts of the same item, and their distributions were well balanced across levels. Because they do not form an ordinal scale, these variables could not be meaningfully collapsed into binary exposure groups. Additionally, because bread and cereal types compete as distinct product choices rather than dose-dependent exposures, preserving their multi-category structure allowed the ANN to capture substitution patterns that would be lost under binary encoding. Preserving nominal predictors using multi-category or one-hot encoding is recommended when categories represent qualitatively distinct choices rather than ordered exposure levels, as collapsing can obscure substitution and interaction effects (41, 77).

Together, these preprocessing decisions aligned variable encoding with the underlying measurement structure of each predictor while preserving the information required for the ANN to learn meaningful non-linear patterns. This approach ensured methodological consistency between models and supported stable and interpretable comparisons across predictor types.

8.3 Weight extraction and feature influence quantification

Effective input to output weights were computed by summing products of connection weights along all hidden paths, providing a systemic importance measure rooted in Garson’s algorithm (78) and extended in ecological modeling (79, 80). For a two hidden layer network, the effective weight from input to output is defined as Equation 3:where is the connection weight from node to node . The sums run over all neurons in the first hidden layer and all neurons in the second hidden layer. This provides a weight-based proxy for systemic importance by decomposing and aggregating connection weights across all paths. To improve stability and reduce overfitting, training was repeated across 10 runs with 5-fold cross-validation, yielding 50 networks per target (79). Feature influence scores were then obtained by multiplying weight matrices across layers and summarizing the values using the median over these 50 models (78, 80), a robust estimator less sensitive to outliers (81).

ANNs naturally capture joint influences among inputs through their layered nonlinear structure, meaning that the effect of any variable can depend on the values of others (82, 83). These interactions are not explicit multiplicative terms in the statistical sense but arise implicitly from the way weighted inputs propagate through the hidden layers (84). To prevent these internal dynamics from compromising interpretability, we did not inspect individual activations or paths directly. Instead, we derived effective connection weights using the Garson-based approach (78) and summarized them across cross-validated runs. This procedure aggregates all hidden-layer pathways into stable influence estimates that represent each variable’s integrated contribution after accounting for its interactions with others. As a result, the ANN can learn complex dependencies without introducing uncontrolled multiplicative artifacts, and the final influence matrices reflect consistent, interpretable, and robust joint effects.

8.4 Stability and coherence evaluation

To assess the robustness of these interactions, stability was evaluated, defined as the consistency of the interaction’s sign across multiple ANN training folds. For systematic interpretation, a four-tier classification was introduced:

Highly Stable: 70% consistency in sign across folds

Moderately Stable: 60%–69% consistency

Low Stability: <60% consistency

Unstable: approximately equal distribution of positive and negative signs (50%)

Stability provides a way to distinguish interaction patterns that are reproducible and potentially meaningful from those driven by noise or sampling variability, an approach commonly used to assess robustness of inferred relationships in neural network and ecological modeling frameworks (

77,

85). In the context of behavioral coherence, lower stability could indicate more fluid or fragmented relationships between variables, whereas higher stability suggests more persistent associations. These definitions make it possible to interpret whether observed coherence patterns indicate stable behavioral structures or emerging disruption. The following section examines how coefficient values and their stability appear in the links between dietary choices and psychological states.

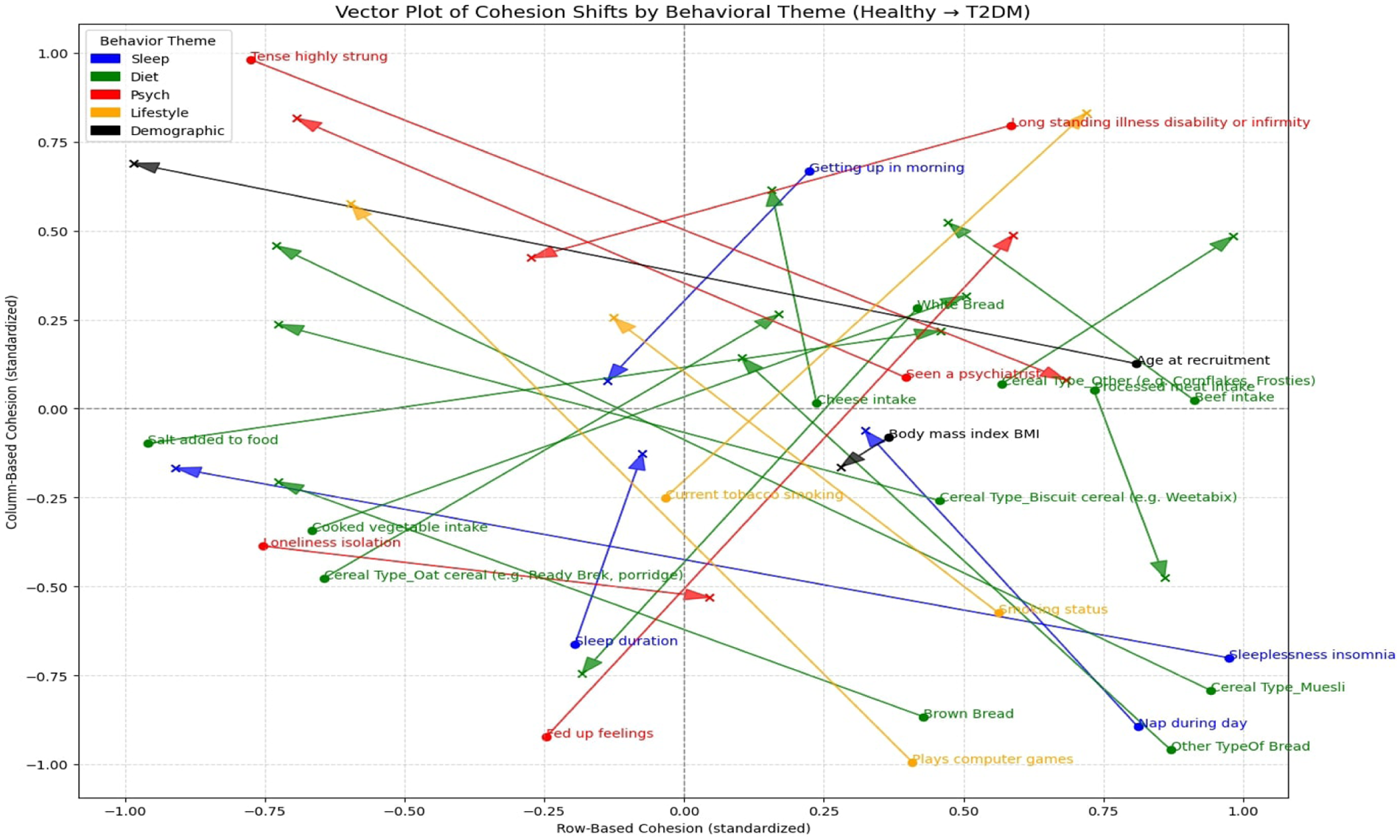

9 Results and discussion of ANN-derived influence modeling

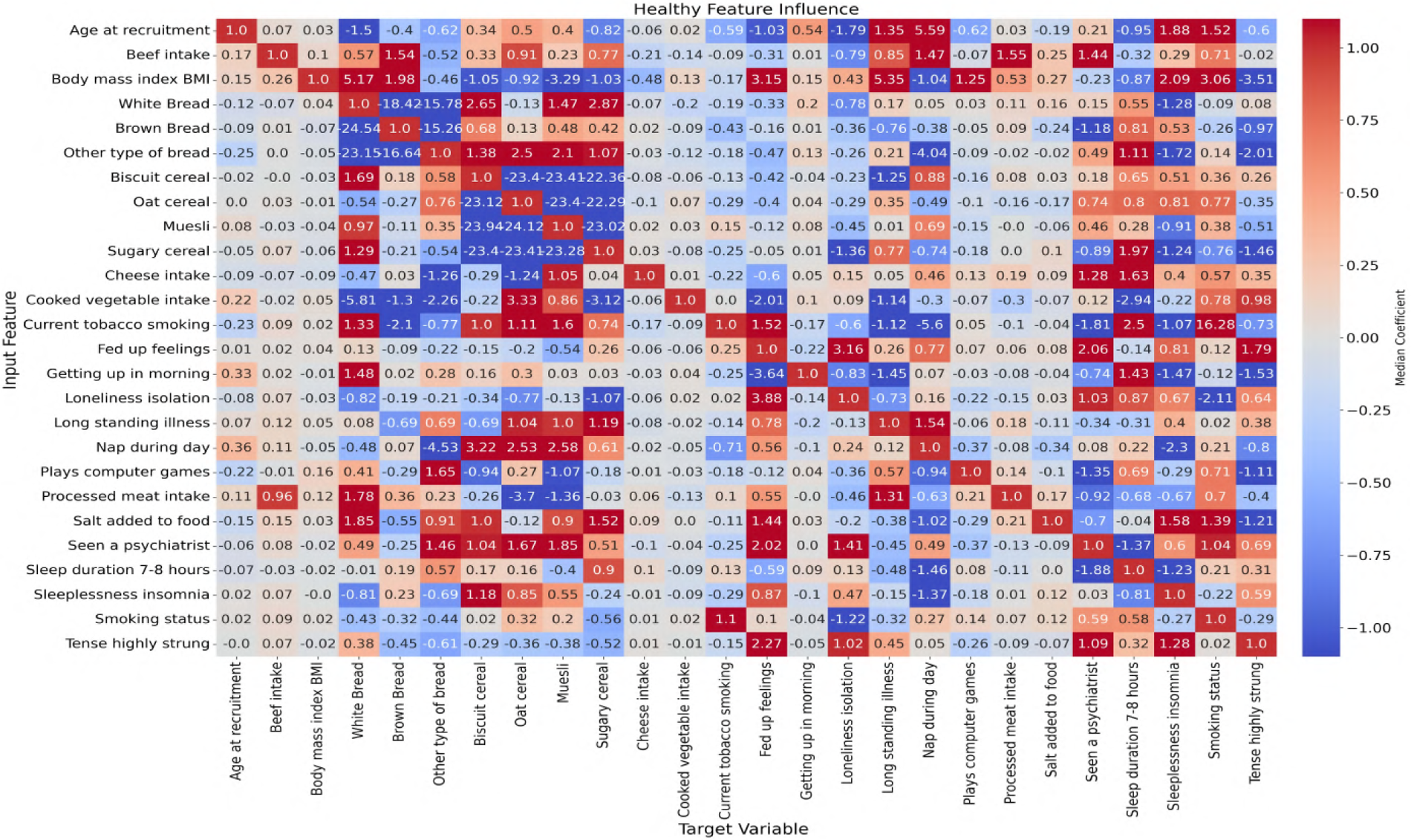

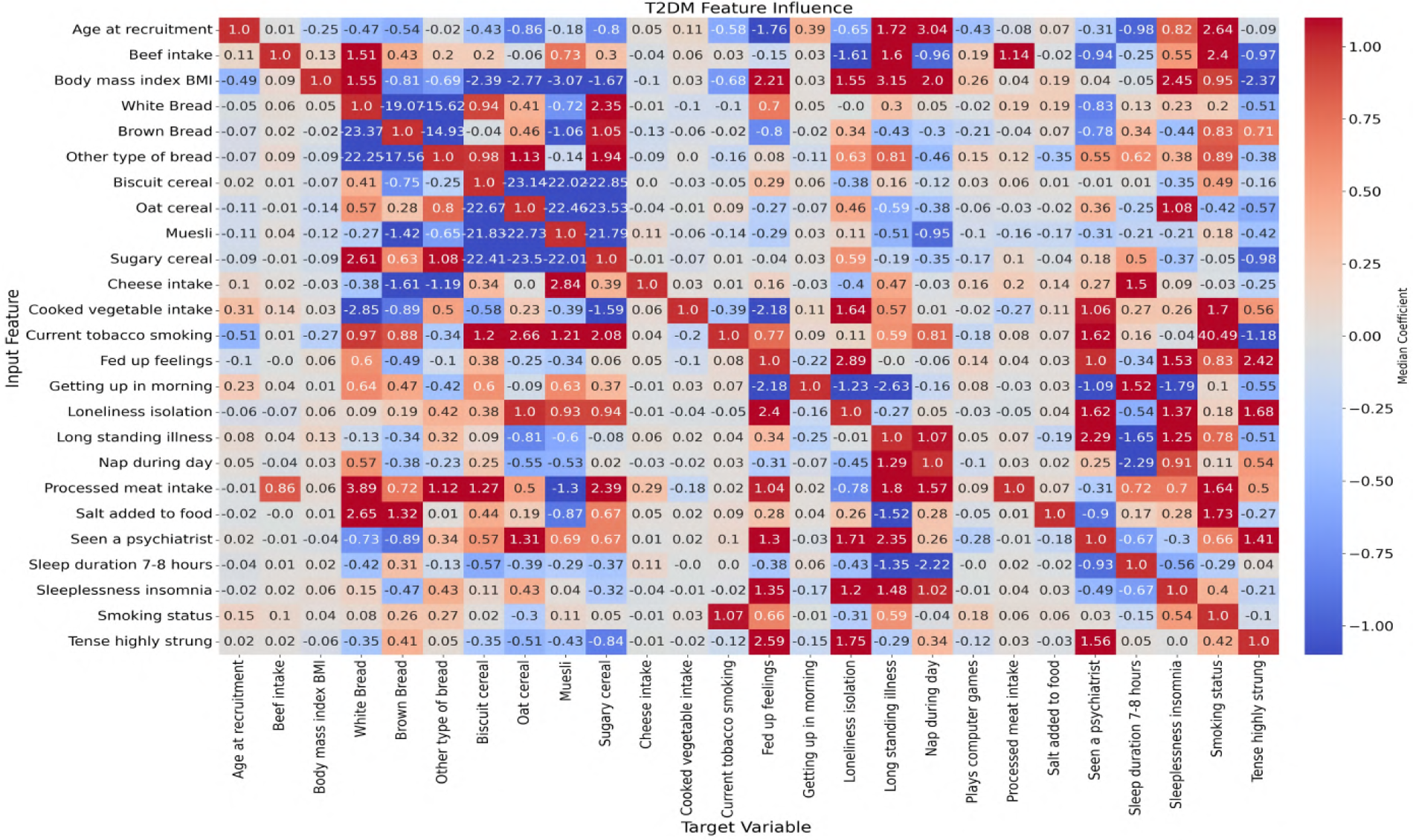

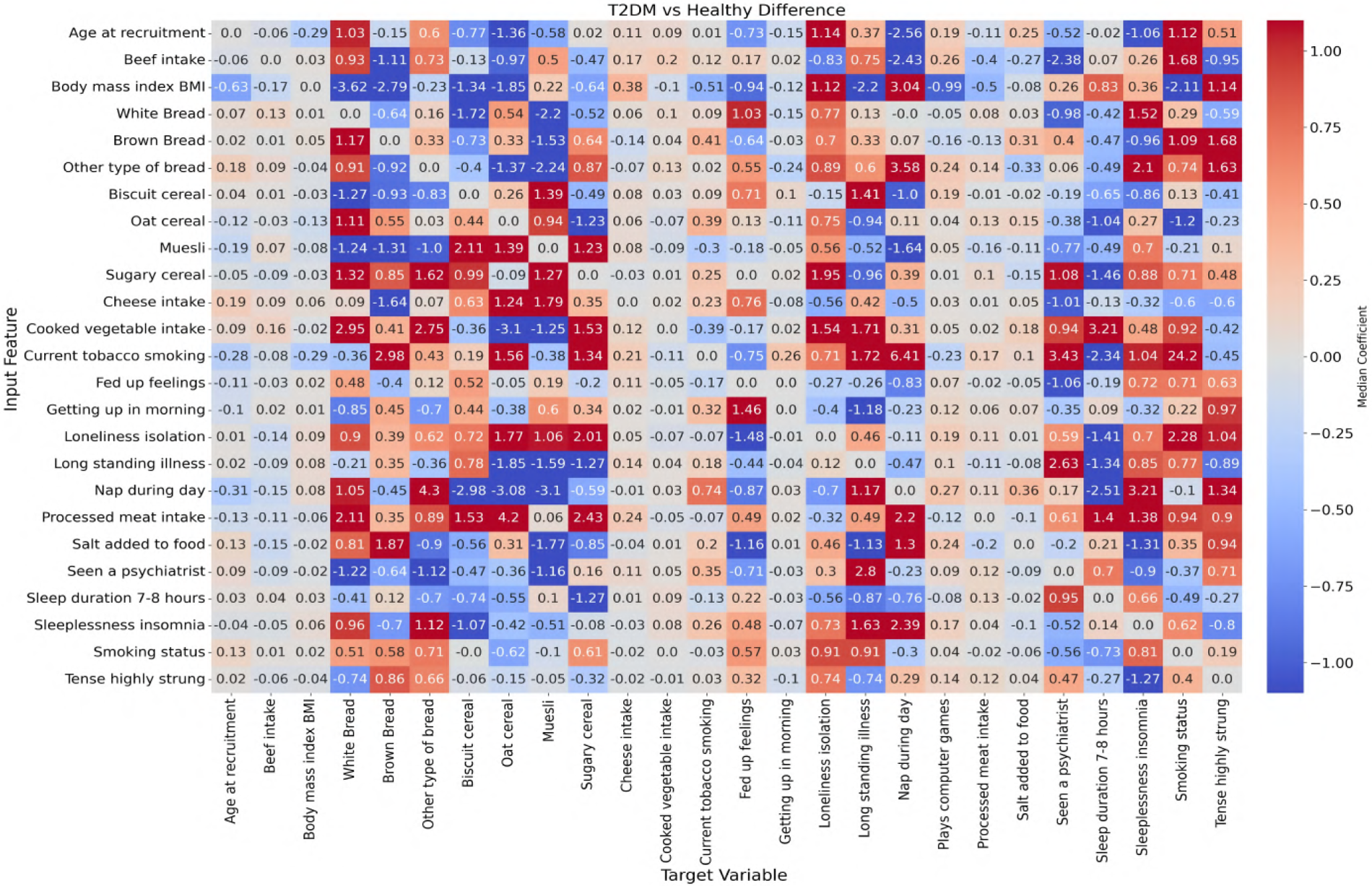

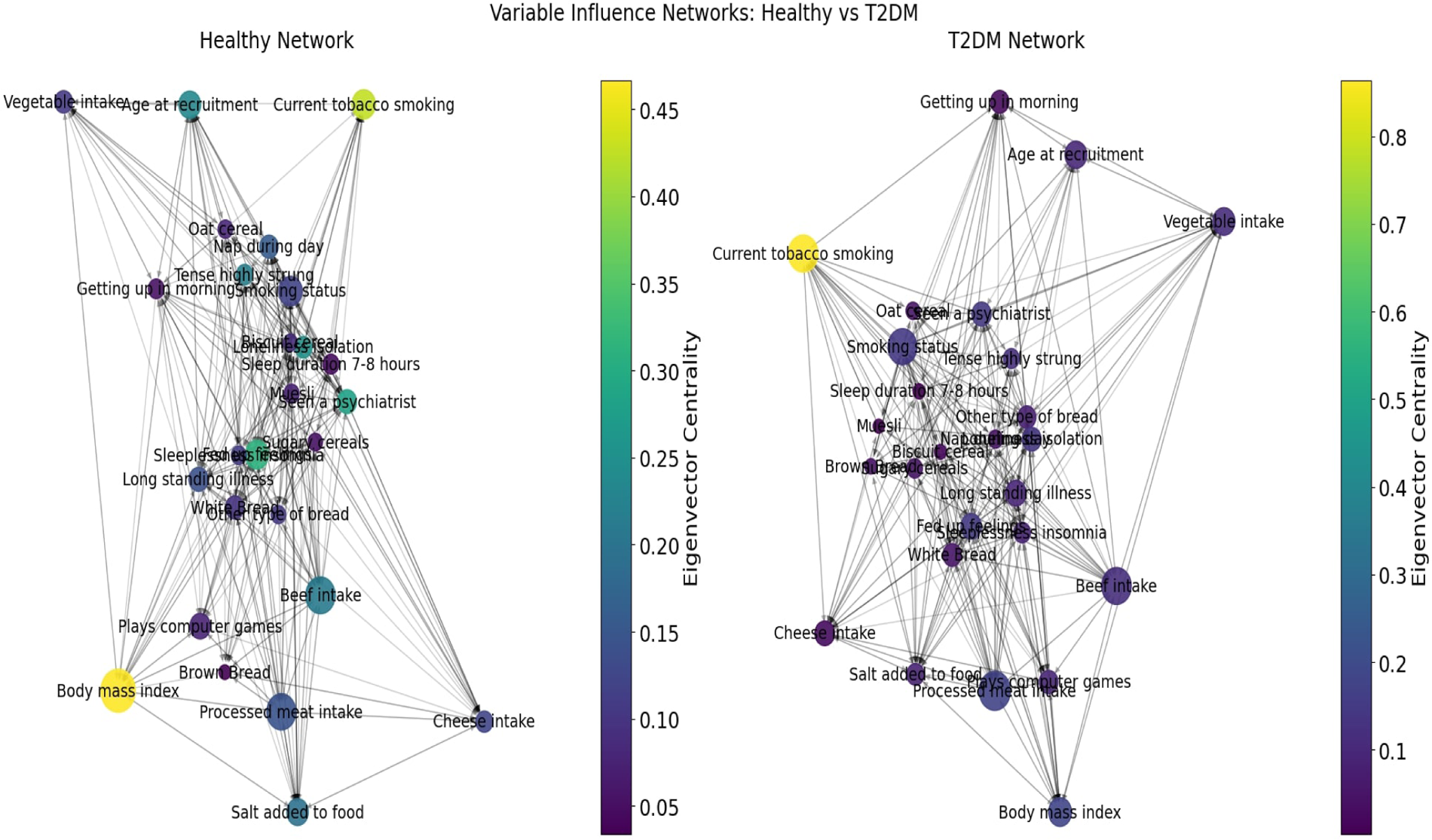

In this study, ANN-derived influence modeling was applied to compare Healthy and T2DM cohorts, using directional influence scores to quantify variable-to-variable associations and generate influence matrices for each group (Figures 5, 6). Subtracting the Healthy matrix from the T2DM matrix produced a Difference Matrix (Figure 7), highlighting domains in which the strength or direction of associations differed between groups. Several variables exhibited sign reversals, where associations observed in Healthy individuals changed direction in T2DM, indicating systematic reorganization of behavioral, emotional, and dietary relationships associated with disease status. These patterns are interpreted descriptively as changes in network structure rather than as evidence of causal pathways or temporal ordering (86).

Figure 5

Neural network-derived feature influence matrix for healthy individuals, where darker colors show stronger positive or negative influences between variables.

Figure 6

Neural network-derived feature influence matrix for T2DM individuals, where darker colors show stronger positive or negative influences between variables.

Figure 7

Difference matrix showing the change in feature influence between T2DM and healthy individuals (T2DM matrix minus Healthy matrix). Highlighted regions indicate variables with substantial shifts in influence relationships, potentially reflecting disrupted behavioral regulation in the diabetic state.

To examine these systemic differences in greater detail, the following sections analyze directional associations between dietary variables and psychological states, followed by the reverse direction from psychological predictors to dietary intake. This bidirectional examination allows comparison of how food–emotion relationships are structured in Healthy individuals vs. those with T2DM.

9.1 Dietary-to-psychological influences

This section explores the relationship between specific food choices and psychological states in the context of T2DM. By examining how the consumption of common dietary items predicts emotional behaviors in healthy compared with T2DM individuals, the analysis highlights how chronic illness may alter the emotional impact of food.

9.1.1 From comfort to coping: Emotional and demographic shifts in T2DM

In the Healthy group, certain foods serve as psychological anchors linked to comfort, regulation, or routine. However, in the context of T2DM, these same foods often become associated with emotional strain, disengagement, or maladaptive coping behaviors. Simultaneously, demographic anchors such as age and BMI, which typically guide food preferences in predictable ways, weaken or invert. This dual pattern emotional revaluation and demographic destabilization signals a broader breakdown in the structure and meaning of dietary behavior under chronic illness. The following case examples illustrate how common foods, once emotionally stabilizing and socially structured, shift in meaning and significance in the presence of metabolic strain.

Table 3 identifies variables with sign reversals, while Table 4 summarizes the effects of age and BMI on dietary intake. The values represent directional influence scores from the neural network models, indicating the sign and relative magnitude of associations. Stability reflects the consistency of the sign across model runs shown in “%.”

Table 3

| Input feature | Target variable | Healthy coeff | Healthy positive | Healthy negative | T2DM coeff | T2DM positive | T2DM negative | Coeff. difference (T2DM–Healthy) | Absolute difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| () | (%) | (%) | () | (%) | (%) | ||||

| White bread | Fed-up feelings | 0.33 | 32 | 68 | 0.69 | 90 | 10 | 1.02 | 1.02 |

| White bread | Seen a psychiatrist | 0.15 | 60 | 40 | 0.83 | 10 | 90 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| White bread | Sleeplessness insomnia | 1.28 | 0 | 100 | 0.23 | 64 | 36 | 1.51 | 1.51 |

| White bread | Tense highly strung | 0.08 | 58 | 42 | 0.51 | 28 | 72 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| Beef intake | Seen a psychiatrist | 1.43 | 96 | 4 | 0.94 | 8 | 92 | 2.37 | 2.37 |

| Biscuit cereal | Fed-up feelings | 0.41 | 26 | 74 | 0.29 | 76 | 24 | 0.71 | 0.71 |

| Biscuit cereal | Seen a psychiatrist | 0.17 | 56 | 44 | 0.01 | 50 | 50 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Biscuit cereal | Sleeplessness insomnia | 0.50 | 74 | 26 | 0.34 | 32 | 68 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Biscuit cereal | Tense highly strung | 0.25 | 62 | 38 | 0.15 | 38 | 62 | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| Brown bread | Loneliness isolation | 0.35 | 20 | 80 | 0.34 | 66 | 34 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

| Brown bread | Sleeplessness insomnia | 0.52 | 70 | 30 | 0.43 | 20 | 80 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Brown bread | Tense highly strung | 0.97 | 32 | 68 | 0.71 | 82 | 18 | 1.68 | 1.68 |

| Cheese intake | Fed-up feelings | 0.60 | 28 | 72 | 0.15 | 54 | 46 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Cheese intake | Loneliness isolation | 0.15 | 64 | 36 | 0.40 | 22 | 78 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Cheese intake | Tense highly strung | 0.35 | 76 | 24 | 0.25 | 28 | 72 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| Cooked vegetable intake | Loneliness isolation | 0.09 | 56 | 44 | 1.63 | 98 | 2 | 1.54 | 1.54 |

| Cooked vegetable intake | Sleeplessness insomnia | 0.21 | 40 | 60 | 0.26 | 64 | 36 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| Muesli | Loneliness isolation | 0.44 | 26 | 74 | 0.11 | 58 | 42 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Muesli | Seen a psychiatrist | 0.46 | 78 | 22 | 0.30 | 42 | 58 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Oat cereal | Loneliness isolation | 0.29 | 28 | 72 | 0.46 | 84 | 16 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Other type of bread | fed-up feelings | 0.47 | 34 | 66 | 0.08 | 52 | 48 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Other type of bread | Loneliness isolation | 0.26 | 34 | 66 | 0.62 | 82 | 18 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Other type of bread | Sleeplessness insomnia | 1.72 | 0 | 100 | 0.38 | 70 | 30 | 2.10 | 2.10 |

| Processed meat intake | Sleeplessness insomnia | 0.67 | 8 | 92 | 0.70 | 84 | 16 | 1.37 | 1.37 |

| Processed meat intake | Tense highly strung | 0.40 | 26 | 74 | 0.49 | 82 | 18 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Salt added to food | Loneliness isolation | 0.19 | 40 | 60 | 0.26 | 68 | 32 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| Sugary cereal | Loneliness isolation | 1.36 | 0 | 100 | 0.59 | 94 | 6 | 1.95 | 1.95 |

| Sugary cereal | Seen a psychiatrist | 0.89 | 16 | 84 | 0.18 | 60 | 40 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

Neural network-derived influence scores and directional stability estimates for specific dietary items associated with psychological variables in healthy individuals and those with T2DM.

Table 4

| Input feature | Target variable | Healthy coeff | Healthy positive | Healthy negative | T2DM coeff | T2DM positive | T2DM negative | Coeff. difference (T2DM – Healthy) | Absolute difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| () | (%) | (%) | () | (%) | (%) | ||||

| Age at recruitment | Beef intake | 0.07 | 96 | 4 | 0.01 | 90 | 10 | 0.0629 | 0.0629 |

| Age at recruitment | Biscuit cereal | 0.34 | 36 | 64 | 0.43 | 56 | 44 | 0.7703 | 0.7703 |

| Age at recruitment | Brown bread | 0.40 | 10 | 90 | 0.54 | 24 | 76 | 0.1492 | 0.1492 |

| Age at recruitment | Cheese intake | 0.06 | 12 | 88 | 0.05 | 94 | 6 | 0.1095 | 0.1095 |

| Age at recruitment | Cooked vegetable intake | 0.02 | 96 | 4 | 0.11 | 100 | 0 | 0.0904 | 0.0904 |

| Age at recruitment | Muesli | 0.40 | 76 | 24 | 0.18 | 14 | 86 | 0.5760 | 0.5760 |

| Age at recruitment | Oat cereal | 0.50 | 52 | 48 | 0.86 | 6 | 94 | 1.3583 | 1.3583 |

| Age at recruitment | Other type of bread | 0.62 | 2 | 98 | 0.02 | 22 | 78 | 0.6019 | 0.6019 |

| Age at recruitment | Processed meat intake | 0.03 | 88 | 12 | 0.08 | 46 | 54 | 0.1082 | 0.1082 |

| Age at recruitment | Salt added to food | 0.19 | 6 | 94 | 0.07 | 40 | 60 | 0.2521 | 0.2521 |

| Age at recruitment | Sugary cereal | 0.82 | 34 | 66 | 0.80 | 16 | 84 | 0.0215 | 0.0215 |

| Age at recruitment | White bread | 1.50 | 12 | 88 | 0.47 | 30 | 70 | 1.0318 | 1.0318 |

| Body mass index | Beef intake | 0.26 | 100 | 0 | 0.09 | 96 | 4 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Body mass index | Biscuit cereal | 1.05 | 14 | 86 | 2.39 | 0 | 100 | 1.34 | 1.34 |

| Body mass index | Brown bread | 1.98 | 100 | 0 | 0.81 | 8 | 92 | 2.79 | 2.79 |

| Body mass index | Cheese intake | 0.48 | 0 | 100 | 0.10 | 2 | 98 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| Body mass index | Cooked vegetable intake | 0.13 | 100 | 0 | 0.03 | 84 | 16 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Body mass index | Muesli | 3.29 | 0 | 100 | 3.07 | 0 | 100 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| Body mass index | Oat cereal | 0.92 | 12 | 88 | 2.77 | 0 | 100 | 1.85 | 1.85 |

| Body mass index | Other type of bread | 0.46 | 28 | 72 | 0.69 | 12 | 88 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Body mass index | Processed meat intake | 0.53 | 100 | 0 | 0.04 | 70 | 30 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Body mass index | Salt added to food | 0.27 | 98 | 2 | 0.19 | 96 | 4 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Body mass index | Sugary cereal | 1.03 | 8 | 92 | 1.67 | 0 | 100 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Body mass index | White bread | 5.17 | 100 | 0 | 1.55 | 100 | 0 | 3.62 | 3.62 |

Neural network-derived influence scores for age at recruitment and BMI predicting intake of specific food items in healthy individuals and those with T2DM.

White bread illustrates this dual process. In healthy individuals, its intake was modestly associated with more psychiatric consultation (; 60% stability), but also with reduced fed-up feelings (; 68% stability) and fewer reports of insomnia (; 100% stability), suggesting a subtle comfort or stabilising role. Stability refers to the percentage of model runs in which the sign of remained consistent (for example, with 68% stability indicates a negative association in 68% of runs, whereas with 60% stability indicates a positive association in 60% of runs). In T2DM, BMI’s strong positive association with intake weakened markedly (1.55 in T2DM vs. 5.17 in Healthy), indicating a loss of demographic predictability. Concurrently, earlier protective emotional links diminished or disappeared, indicating that the earlier emotionally stabilizing associations are no longer present. This erosion of both demographic and emotional coherence may reflect processes such as dietary fatigue, habituation to familiar foods, and reduced emotional reward, as suggested by psychological models of eating behavior and self-regulation (87, 88). In chronic illness, white bread appears to shift from a behavior embedded in stable emotional patterns to one with reduced psychological anchoring, potentially reflecting the combined influence of dietary constraints and emotional strain.