1 Introduction

Ocular anterior segment diseases are a significant global public health concern, being major contributors to blindness and visual impairment worldwide (1–4). Cataract, known as the leading cause of reversible blindness and visual impairment globally (5–7), along with corneal diseases, which rank as the fourth leading cause of blindness (8, 9), underscore the urgent need for timely diagnosis and intervention, particularly for conditions like keratitis that can progress rapidly (10, 11). Among the essential tools for diagnosing and managing these conditions is the slit-lamp biomicroscope, a fundamental instrument in ophthalmology clinics known for its convenience, availability, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency in identifying common ocular anterior segment diseases.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have shown promising results in automated diagnosis and treatment planning based on slit-lamp images (12–23). However, these AI systems are often limited by the availability of comprehensive datasets for training and validation purposes. Currently, there is a scarcity of open-access datasets that include slit-lamp images with detailed anatomical annotations and lesion identification necessary for developing robust AI models applicable to real-world clinical scenarios.

The publication of slit-lamp image datasets with thorough anatomical annotations and lesion identification is therefore pivotal. These datasets not only facilitate the advancement of AI models capable of precise and clinically relevant diagnoses but also serve to validate existing AI technologies. By offering standardized datasets to researchers globally, we aim to expedite progress toward more efficient computer-aided diagnosis and treatment systems for ocular anterior segment diseases.

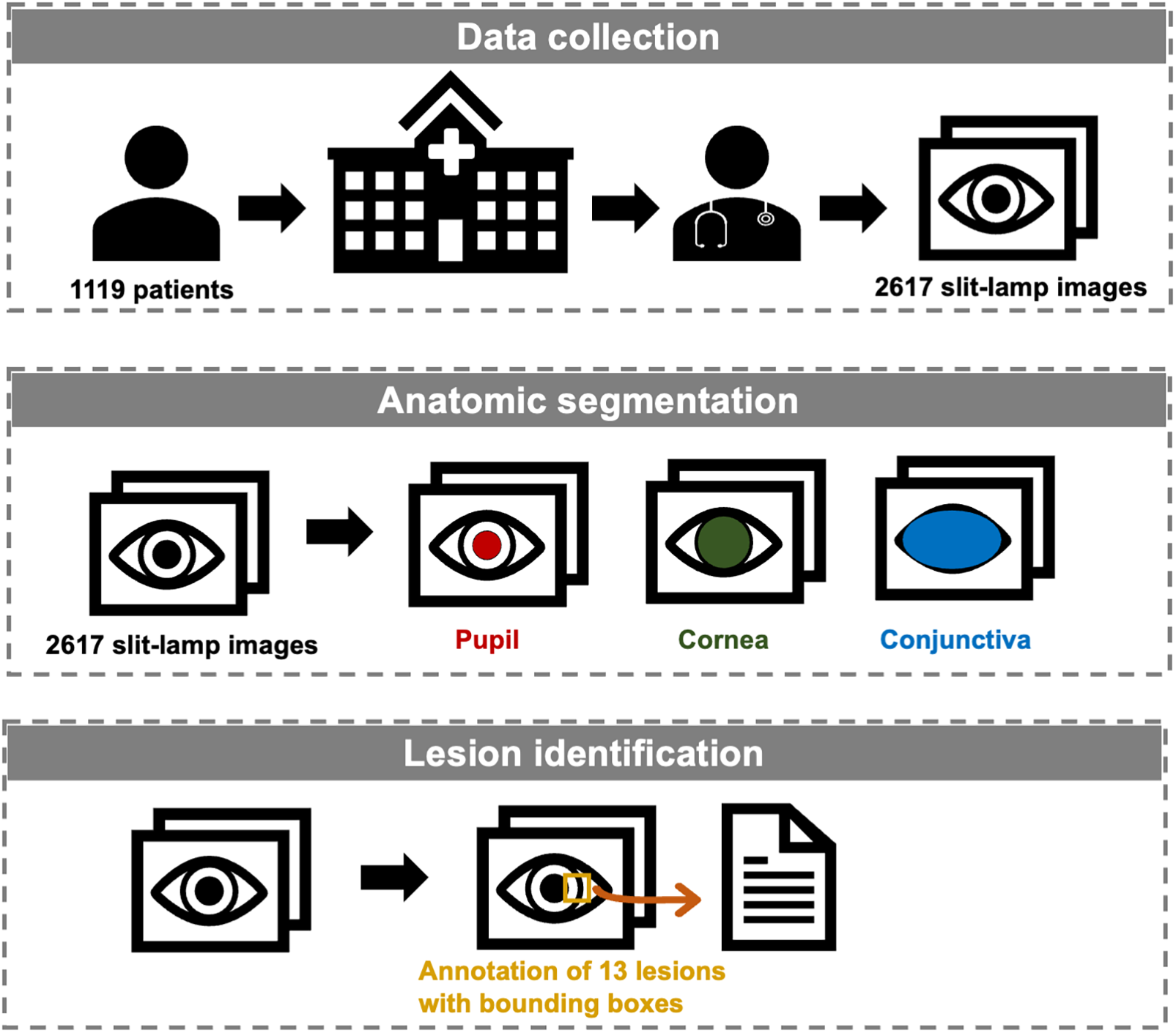

This paper introduces a comprehensive dataset crafted to fill these critical gaps in the field. Figure 1 illustrates our study, delineating the processes of data collection, anatomical segmentation, and lesion identification. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first open-source slit-lamp dataset with detailed anatomical and lesion-level information. Our dataset endeavors to serve as an invaluable resource for researchers endeavoring to develop AI models that are not only accurate but also applicable in preclinical screening and clinical practice.

Figure 1

Workflow of the establishment of the slit-lamp dataset.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Patient selection and image acquisition

We retrospectively collected 2,617 ocular surface slit-lamp images from 1,119 patients between November 2016 and March 2022 at the Eye Center of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, College of Medicine, China. All images were captured using Topcon SL-D701 slit-lamp biomicroscopes equipped with DC-4 digital cameras. Images were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) Poor quality images, defined as images with significant defocus or inappropriate illumination (overexposed or underexposed conditions) such that lesion features cannot be clearly identified; (2) Indeterminate lesions, defined as cases with atypical or ambiguous presentations in which our annotation team could not reach a consensus on the specific lesion category; (3) Anatomical abnormalities, defined as structural alterations of the ocular surface caused by prior surgery or trauma. To ensure anonymity, patient information was obscured with a black rectangular box in the top left corner of each image. Due to multiple follow-up visits for the same patient and varying eye positions and focus points during the same visit, multiple images may exist for the same eye of a single patient.

Demographically, a total of 1,383 eyes were included, comprising 668 left eyes and 715 right eyes, corresponding to 1,119 patients. Of these, 621 were women and 498 were men. Age distribution was as follows: 236 patients <18 years, 408 aged 18–44 years, 200 aged 45–59 years, and 275 aged ≥60 years. The number of images, eyes, and patients corresponding to each disease category was provided in Table 1.

Table 1

| Category | No. images | No. eyes | No. patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 245 | 220 | 150 | |

| Monomorbidity | Cataract | 107 | 92 | 77 |

| Intraocular lens | 69 | 34 | 31 | |

| Lens dislocation | 31 | 16 | 10 | |

| Keratitis | 162 | 38 | 37 | |

| Corneal scarring | 49 | 25 | 24 | |

| Corneal dystrophy | 289 | 169 | 108 | |

| Corneal/conjunctival tumor | 447 | 164 | 162 | |

| Pinguecula | 203 | 129 | 103 | |

| Pterygium | 92 | 63 | 51 | |

| Subconjunctival hemorrhage | 134 | 69 | 66 | |

| Conjunctival injection | 36 | 26 | 23 | |

| Conjunctival cyst | 90 | 43 | 42 | |

| Pigmented nevus | 382 | 175 | 165 | |

| Multimorbidity | 281 | 192 | 179 | |

The number of images, eyes, and patients corresponding to each disease category of the SLID dataset.

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, College of Medicine (IR2021001176). All procedures conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data was retrospectively collected from patients through routine medical care and obtained from medical facilities. The dataset does not include direct identifiers, as all participants’ names were removed, and their IDs were restructured to anonymize identifying information. Thus, the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, College of Medicine granted a waiver of consent.

2.2 Annotation

The annotation data includes localization and categorical information pertaining to anatomical regions and lesions. All images underwent manual annotation using the VGG annotator by a professional team (24). This team comprised one junior ophthalmologists (JO) with over three years of clinical experience, one senior ophthalmologists (SO) with more than six years of clinical experience, and one specialized ophthalmologist with over 10 years of clinical experience. The JO and SO independently labeled the images, which were then reviewed and confirmed by the specialized ophthalmologist, and respective metadata files were exported.

For anatomical segmentation, three regions were annotated: pupil, cornea, and conjunctiva. Each image's anatomical annotations were meticulously delineated with respect to their labels. Typically, the anatomic regions of pupil and cornea were within the labeled circle and ellipse up to the conjunctival boundary (if intersected). In cases where the exposed areas of the pupil or cornea were too small to be labeled by circle or ellipse, polygonal contours were used. The conjunctiva was consistently contoured using polygons across all cases. It is important to note that certain anatomical regions may not be labeled if they are excluded from the image or if their edges cannot be determined due to the presence of lesions. An example of anatomical annotation is shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

For lesion identification, we identified 13 common classes encountered in clinical practice: cataract, intraocular lens, lens dislocation, keratitis, corneal scarring, corneal dystrophy, pinguecula, pterygium, subconjunctival hemorrhage, conjunctival injection, conjunctival cyst, pigmented nevus, and corneal/conjunctival tumor. Lesions were annotated using bounding boxes, except for cataract, intraocular lens, lens dislocation, and conjunctival injection. These lesions encompass the entire pupil or conjunctival area, so they were localized as the respective anatomical region. For normal images without detected lesions, only anatomical annotations were included. Examples illustrating lesion annotations for all monomorbidity cases and an example of multimorbidity are depicted in Supplementary Figure S2.

2.3 Data description

The dataset is available on the Github, with a summary of its features provided in Table 2. During the review stage, reviewers can access it via a token-protected link, with detailed protocols provided in the Data availability section. Upon publication, the dataset will be publicly accessible on GitHub.

Table 2

| Category | No. images with the label | No. images without the label |

|---|---|---|

| Pupil | 2,303 | 314 |

| Cornea | 2,573 | 44 |

| Conjunctiva | 2,616 | 1 |

| Cataract | 225 | 2,392 |

| Intraocular lens | 119 | 2,498 |

| Lens dislocation | 40 | 2,577 |

| Keratitis | 222 | 2,395 |

| Corneal scarring | 69 | 2,548 |

| Corneal dystrophy | 300 | 2,317 |

| Corneal/conjunctival tumor | 488 | 2,129 |

| Pinguecula | 405 | 2,212 |

| Pterygium | 163 | 2,454 |

| Subconjunctival hemorrhage | 181 | 2,436 |

| Conjunctival injection | 307 | 2,310 |

| Conjunctival cyst | 113 | 2,504 |

| Pigmented nevus | 416 | 2,201 |

Features of the SLID dataset.

The original slit-lamp images are in PNG format and can be found in the “Original_Slit-lamp_Images” folder, named as “n.png”, and the respective annotated file is provided as “Annotations.csv”.

The “Original_Slit-lamp_Images” file contains 2,617 slit-lamp images, with the “n” ranging from 1 to 2,617 representing the respective image number. The dataset includes images at three resolutions: 2,576 × 1,934 pixels (1,412 images), 1,924 × 1,556 pixels (746 images), and 1,284 × 964 pixels (459 images). Of these 2,617 images, 245 are from patients with no detectable lesions, 2091 are from patients with a single lesion (monomorbidity), and 281 are from patients with multiple lesions (multimorbidity). For the multimorbidity subset, the mean number of lesions per image is 2.82, and the median is 3. It should be noted that keratitis is almost always accompanied by conjunctival injection; therefore, images with only these labels are included in the monomorbidity set.

The “Annotations.csv” contains five columns: “filename”, “file_size”, “annotation_count”, “annotation_ID”, “attributes”, and “shape_coordinates”. “filename” indicates the image name, “file_size” indicates the image size, “annotation_count” specifies the number of annotations, “annotation_ID” represents the annotation ID, “attributes” details specific anatomical regions and lesions, and “shape_coordinates” describes their respective localization.

3 Data validation and utility

3.1 Data validation

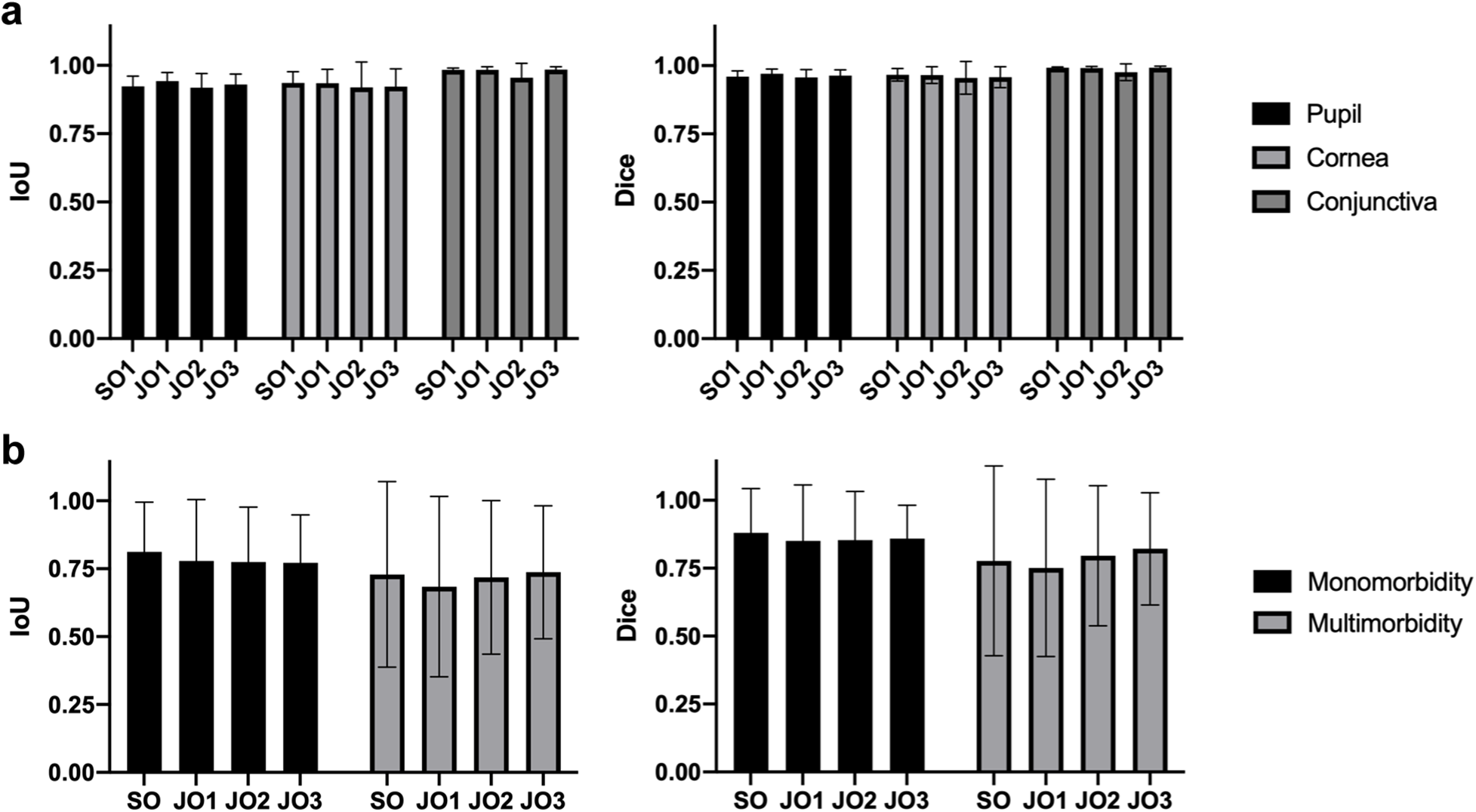

To validate the anatomic and lesion annotations, another one SO and three JOs were invited to anatomically segment 20 images and identify lesions in 195 images containing both monomorbidity and multimorbidity conditions randomly selected from the dataset. The results of anatomic segmentation and lesion identification are presented in Figure 2. All anatomic regions demonstrated excellent consistency, with mean IoU (Intersection over Union) >0.918 and mean Dice > 0.955 across all three regions and all four experts. Notably, segmentation performance for the conjunctival region was slightly superior to that of the corneal and pupillary regions, likely due to the clearer boundary between the conjunctiva and surrounding eyelid skin tissue. The validation results of lesion identification showed acceptable consistency, with mean IoU > 0.764 and mean Dice > 0.835 across all four experts. Among these images, those with monomorbidity exhibited relatively higher consistency, achieving a mean IoU of 0.785 and mean Dice score of 0.861. Images with multimorbidity also showed acceptable consistency, with a mean IoU of 0.717 and mean Dice score of 0.786. When analyzing specific lesion types, pterygium and pinguecula demonstrated lower consistency, primarily due to their less distinct lesion boundaries.

Figure 2

Validation of the SLID dataset. (a) The IoU and Dice score of the anatomic segmentation validation. (b) The IoU and Dice score of the lesion identification validation.

3.2 Data utility

To evaluate the potential of the proposed dataset for deep learning-based anterior eye multi-lesion detection, a YOLOv8 model was trained using single-lesion images following standard procedures, with experiment parameters listed in Supplementary Table S1 (25). At the image level, the dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio, achieving an average mean Average Precision (mAP) of 0.873 across all 13 single-lesion categories (Supplementary Table S2). At the patient level, we re-executed the 8:1:1 split, ensuring that all images from the same patient were assigned to a single dataset (training, validation, or test). Under this patient-level split, YOLOv8 achieved an average mAP of 0.736.

Statements

Data availability statement

De-identified data were used in the present study. These data are publicly accessible on GitHub at https://github.com/xumingyu-hub/SLID.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, College of Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because data was retrospectively collected from patients through routine medical care and obtained from medical facilities. The dataset does not include direct identifiers, as all participants’ names were removed, and their IDs were restructured to anonymize identifying information.

Author contributions

MX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YS: Validation, Writing – review & editing. HC: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology. YZ: Writing – review & editing, Validation. NM: Writing – review & editing, Validation. PC: Writing – review & editing, Validation. QM: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. PX: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. JY: Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82330032), the National Natural Science Foundation Regional Innovation and Development Joint Fund (U20A20386), the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2024C03204), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82101129).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdgth.2025.1716501/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Ahr H . Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to sight: an analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet Glob Health. (2021) 9(2):e144–60. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7

2.

Bourne RRA Flaxman SR Braithwaite T Cicinelli MV Das A Jonas JB et al Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. (2017) 5(9):e888–97. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30293-0

3.

Wang EY Kong X Wolle M Gasquet N Ssekasanvu J Mariotti SP et al Global trends in blindness and vision impairment resulting from corneal opacity 1984–2020: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. (2023) 130(8):863–71. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.03.012

4.

Xu T Wang B Liu H Wang H Yin P Dong W et al Prevalence and causes of vision loss in China from 1990 to 2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5(12):e682–91. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30254-1

5.

Cicinelli MV Buchan JC Nicholson M Varadaraj V Khanna RC . Cataracts. Lancet. (2023) 401(10374):377–89. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01839-6

6.

Lam D Rao SK Ratra V Liu Y Mitchell P King J et al Cataract. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2015) 1:15014. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.14

7.

Chen X Xu J Chen X Yao K . Cataract: advances in surgery and whether surgery remains the only treatment in future. Adv in Ophthal Pract and Res. (2021) 1(1):100008. 10.1016/j.aopr.2021.100008

8.

Jeng BH Ahmad S . In pursuit of the elimination of corneal blindness: is establishing eye banks and training surgeons enough?Ophthalmology. (2021) 128(6):813–5. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.06.042

9.

Organization WH. World health statistics (2015). Available online at:https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2015/en/(Accessed May 01, 2023).

10.

Brown L Leck AK Gichangi M Burton MJ Denning DW . The global incidence and diagnosis of fungal keratitis. Lancet Infect Dis. (2021) 21(3):e49–57. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30448-5

11.

Ting DSJ Gopal BP Deshmukh R Seitzman GD Said DG Dua HS . Diagnostic armamentarium of infectious keratitis: a comprehensive review. Ocul Surf. (2022) 23:27–39. 10.1016/j.jtos.2021.11.003

12.

Fang X Deshmukh M Chee ML Soh ZD Teo ZL Thakur S et al Deep learning algorithms for automatic detection of pterygium using anterior segment photographs from slit-lamp and hand-held cameras. Br J Ophthalmol. (2022) 106(12):1642–7. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-318866

13.

Gu H Guo Y Gu L Wei A Xie S Ye Z et al Deep learning for identifying corneal diseases from ocular surface slit-lamp photographs. Sci Rep. (2020) 10(1):17851. 10.1038/s41598-020-75027-3

14.

Keenan TDL Chen Q Agrón E Tham YC Goh JHL Lei X et al Deeplensnet: deep learning automated diagnosis and quantitative classification of cataract type and severity. Ophthalmology. (2022) 129(5):571–84. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.12.017

15.

Koyama A Miyazaki D Nakagawa Y Ayatsuka Y Miyake H Ehara F et al Determination of probability of causative pathogen in infectious keratitis using deep learning algorithm of slit-lamp images. Sci Rep. (2021) 11(1):22642. 10.1038/s41598-021-02138-w

16.

Li W Yang Y Zhang K Long E He L Zhang L et al Dense anatomical annotation of slit-lamp images improves the performance of deep learning for the diagnosis of ophthalmic disorders. Nat Biomed Eng. (2020) 4(8):767–77. 10.1038/s41551-020-0577-y

17.

Li Z Jiang J Chen K Chen Q Zheng Q Liu X et al Preventing corneal blindness caused by keratitis using artificial intelligence. Nat Commun. (2021) 12(1):3738. 10.1038/s41467-021-24116-6

18.

Tabuchi H Masumoto H . Objective evaluation of allergic conjunctival disease (with a focus on the application of artificial intelligence technology). Allergol Int. (2020) 69(4):505–9. 10.1016/j.alit.2020.05.004

19.

Tiwari M Piech C Baitemirova M Prajna NV Srinivasan M Lalitha P et al Differentiation of active corneal infections from healed scars using deep learning. Ophthalmology. (2022) 129(2):139–46. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.07.033

20.

Wei Z Wang S Wang Z Zhang Y Chen K Gong L et al Development and multi-center validation of machine learning model for early detection of fungal keratitis. EBioMedicine. (2023) 88:104438. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104438

21.

Wu X Liu L Zhao L Guo C Li R Wang T et al Application of artificial intelligence in anterior segment ophthalmic diseases: diversity and standardization. Ann Transl Med. (2020) 8(11):714. 10.21037/atm-20-976

22.

Yoo TK Choi JY Kim HK Ryu IH Kim JK . Adopting low-shot deep learning for the detection of conjunctival melanoma using ocular surface images. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. (2021) 205:106086. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106086

23.

Zhang Z Wang H Wang S Wei Z Zhang Y Wang Z et al Deep learning-based classification of infectious keratitis on slit-lamp images. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. (2022) 13:20406223221136071. 10.1177/20406223221136071

24.

Abhishek Dutta AG Zisserman A . VGG Image Annotator (VIA)).

25.

Ultralytics. YOLOv8: a new state-of-the-art computer vision model. Available from: https://yolov8.com/ (Accessed April 01, 2024).

Summary

Keywords

anatomical segmentation, dataset, deep learning, lesion detection, ocular anterior segment disease, open source

Citation

Xu M, Sun Y, Cheng H, Zhou Y, Maimaiti N, Chen P, Miao Q, Xu P and Ye J (2026) SLID: a slit-lamp image dataset for deep learning-based anterior eye anatomical segmentation and multi-lesion detection. Front. Digit. Health 7:1716501. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1716501

Received

18 December 2025

Revised

26 November 2025

Accepted

18 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Zhao Ren, University of Bremen, Germany

Reviewed by

Yukun Zhou, University College London, United Kingdom

Runzhi Zhou, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Xu, Sun, Cheng, Zhou, Maimaiti, Chen, Miao, Xu and Ye.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Peifang Xu xpf1900@zju.edu.cn Juan Ye yejuan@zju.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.