Abstract

Background:

Health hotlines serve as platforms for patient–provider communication globally. However, few studies have explored public satisfaction with health hotline services. This study investigated the associations between the characteristics of health hotline platforms and public satisfaction with their services, aiming to provide insights for optimizing risk communication and improving residents’ access to health information via health hotlines.

Methods:

A retrospective observational study was conducted using calls and messages (CMs) received on a health hotline platform in Guangzhou, China, in 2023 and 2024. Generalized linear models were used to assess the associations between various request–response characteristics and public satisfaction with the hotline service.

Results:

A total of 9,280 satisfaction-related CMs were included in the analysis. All the request–response characteristics of the hotline were associated with public satisfaction. For example, responses at the department level were more satisfying than those at the hospital level, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.26 (95% CI 1.05–1.51). Regarding CM content, CMs related to patient safety had a lower satisfaction than non-clinical CMs, with an OR of 0.60 (95% CI 0.45–0.78). Additionally, as the response time increased, residents’ satisfaction tended to decrease (P for trend <0.05).

Conclusions:

The study indicated that request–response characteristics, such as response hierarchy and response time, significantly influence public satisfaction with health hotlines. Our findings provide novel evidence for optimizing the service quality of health hotline platforms to improve public satisfaction, which is valuable for enhancing patient–provider communication and improving the efficiency and quality of healthcare delivery.

1 Introduction

Effective communication has been identified as an important factor in healthcare delivery and significantly influences public satisfaction (1). Many countries and agencies have implemented health hotline platforms as a foundational element of their modern digital health systems (2–7). Telephone-based services such as health hotlines constitute a primary form of “client-to-provider telemedicine,” facilitating remote triage and serving as an inclusive entry point to the health system that bridges the digital divide (8). Some health hotlines have been proven to be effective in enhancing communication effects and public satisfaction (9–11). For example, a study in Scotland investigated the public's use of and attitude towards NHS 24, the NHS hotline, and revealed that over 80.0% of callers were satisfied with the NHS 24 service and that 93.9% would use it again; thus, NHS 24 has been viewed as an out-of-hours alternative to general practitioners (9). A systematic review from Australia reported that 988 cancer helplines deliver psychosocial benefits to patients affected by cancer, and the majority of cancer helpline callers were generally satisfied with the information they received, the way their call was managed, and the consultants’ knowledge and approach (4).

Thus, optimizing hotline operations is not merely a service improvement but a strategic enhancement of digital health infrastructure. Exploring the operational mechanism and core function of health hotline platforms is highly important for offering actionable insights to increase public satisfaction and improve patient–provider communication. A study from Oman assessed satisfaction with telephone-based psychiatry consultations and found that the sex, employment status, and income of users significantly influenced satisfaction levels (12). However, beyond demographic factors, understanding how platform-specific characteristics affect user experience is crucial. Evidence regarding the specific request–response characteristics of health hotline platforms that influence satisfaction remains scarce. Crucially, studies have found that actions taken by health hotline platforms, such as conducting training for hotline staff (13,14), enhancing communication competence, and promoting systems-based practice (14), are effective in improving communication via health hotlines.

Yet, research on the request–response characteristics of health hotline platforms that affect public satisfaction is still lacking, especially in developing countries. In the present study, we explored the associations between the characteristics of health hotline services and public satisfaction based on residents’ calls and messages (CMs).

2 Methods

2.1 Study setting and patient and public involvement

The 12320 health hotline is a platform that was established by the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Originating from the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Prevention and Consultation Hotline during the 2003 SARS outbreak, 12320 was officially launched in 2005 and implemented nationwide by 2012, functioning as a governmental conduit for health-related communication between the public and healthcare providers.

This study was conducted on a dataset from the 12320 Health Hotline Department of the Guangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Guangzhou is a core city in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area in China.

The 12320 Health Hotline in Guangzhou (12320-GZ) serves as a governmental health hotline platform for communication between the public and healthcare providers and guides residents’ CMs to relevant institutions, enhances hospital supervision, and addresses public concerns effectively.

12320-GZ staff respond to residents’ health requests in various ways, such as providing information and advice on appropriate self-care, arranging callbacks or visits by relevant clinical professionals, or referring them to other services when necessary.

2.2 Data source

CM data were collected from the 12320-GZ platform in 2023 and 2024. Then, we excluded CMs with missing satisfaction data. The response rate for the public satisfaction survey was 34.4%. In total, we gathered 9,280 CMs.

2.3 Identification of variables

We collected data on public satisfaction and request–response characteristics from the 12320-GZ system.

2.3.1 Outcome variable

Public satisfaction was initially rated on a 5-point scale (ranging from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied”). To facilitate model parsimony and provide a clear interpretation of the primary drivers of satisfaction, we dichotomized this variable. “Very satisfied” and “satisfied” were rated as 1 (satisfied), while the remaining grades were rated as 0 (dissatisfied). To ensure that this loss of granularity did not distort the findings, we performed a sensitivity analysis using multinomial logistic regression on the original 5-point scale, which confirmed the consistency of the results. Satisfaction ratings were self-reported by the residents and uploaded to the 12320-GZ system (see Supplementary Material).

2.3.2 Explanatory variables

The request–response characteristics included the following variables. Detailed definitions are provided in

Table 1.

- (1)

Response hierarchy: The organizational level at which the CM was processed and resolved (classified as either the general hospital level or the specific department level).

- (2)

Response mode: The communication channel utilized by the platform to deliver the final feedback to the resident (e.g., telephone, message, or alternative means).

- (3)

Resident's request: The primary intent or category of the resident's interaction (classified as a suggestion, consultation, or complaint).

- (4)

CM content: The specific subject matter or nature of the issue raised in the CM (e.g., clinical quality or patient safety).

- (5)

Facticity verification: The extent to which the details described by the resident were verified and acknowledged as accurate by the healthcare provider following an internal investigation (classified as accepted, partially accepted, or not accepted).

- (6)

Response time: The total duration from when the platform received the CM to the resident receiving the response. This was categorized into the following four quartiles: Q1 (0–3 days), Q2 (3–9 days), Q3 (9–13 days), and Q4 (13–48 days).

Table 1

| Variable | Variable levels and description |

|---|---|

| Response hierarchy | Hospital level: CMs processed at the hospital level |

| Department level: CMs processed at the specific hospital department | |

| Response time | The following four quantiles were divided according to the response time (the time from when 12320-GZ received the CMs to when the patient got the response from 12320-GZ): quantile 1 (Q1, ≤25th): 0–3days; |

| quantile 2 (Q2, 25th–50th): 3–9 days; | |

| quantile 3 (Q3, 50th–75th): 9–13 days; | |

| quantile 4 (Q4, ≥75th): 13–48 days | |

| Resident's request | Suggestion: CM providing constructive opinions or advice to improve healthcare services |

| Consultation: CM requesting health-related information or guidance | |

| Complaint: CM expressing dissatisfaction or criticism about perceived issues, mistakes, or misconduct in healthcare settings | |

| Response mode | Telephone response: responded via phone call. |

| Message response: responded via short message service | |

| Alternative response: other types of response to the patient, such as a written response | |

| CM content | Non-clinical item: CM related to administrative matters that did not involve medical or nursing matters, such as appointment scheduling and health certificate requests |

| Systemic issue: CM related to organizational and systemic issues affecting the overall functioning of healthcare services, instead of specific incidents, such as a staff shortage, long wait time, inefficiencies in workflows, and inadequate facilities | |

| Clinical quality: CM related to medical quality outcome from the resident’s perspective during healthcare experiences that were not a severe safety risk, such as dissatisfaction with treatment effectiveness and unsuccessful communication with healthcare staff | |

| Patient safety: CM related to serious incidents or concerns threatening patient safety, such as medication errors, surgical complications, adverse drug reactions, and healthcare-associated infections | |

| Facticity verification | Not accepted: not accepted due to the resident’s entirely inaccurate or unreasonable description |

| Partially accepted: partially accepted due to a partially inaccurate or unreasonable description | |

| Accepted: accepted due to accurate verification by medical providers |

Variables and variable levels of the request–response characteristics provided by 12320-GZ.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages n (%). Pearson's chi-square test was used to compare baseline characteristics between the dissatisfied and satisfied groups.

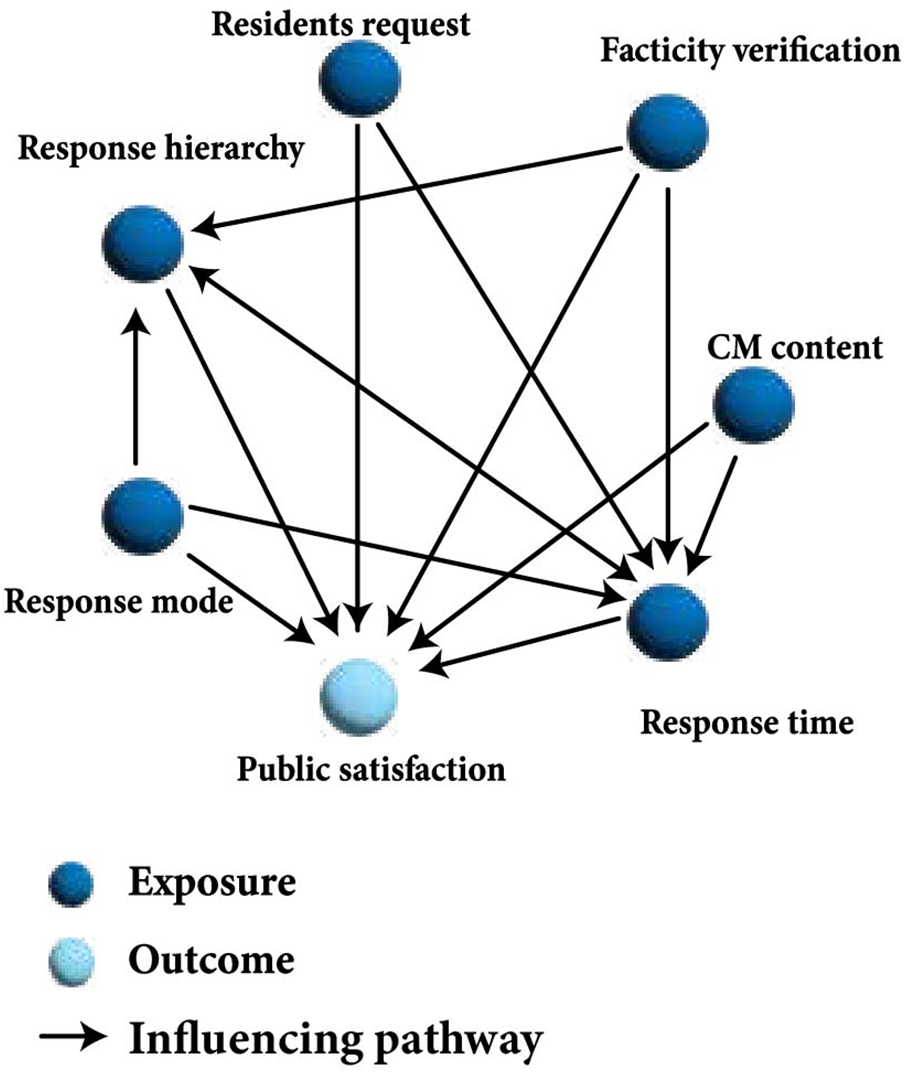

A directed acyclic graph (DAG) was constructed to guide the selection of potential confounders and illustrate the hypothesized causal pathways between the request–response characteristics and public satisfaction (Figure 1). The structure of the DAG was informed by prior subject matter knowledge, a literature review, and consultations with health hotline staff. To validate the robustness of the DAG-informed adjustment strategy, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a series of six nested models.

Figure 1

The DAG of the relationship between the request–response characteristics of the health hotline platform and public satisfaction.

Associations were analyzed using generalized linear models. Based on the DAG analysis, the variables used in the model included the response hierarchy, response time, resident's request, response mode, CM content, and facticity verification (Figure 1). In addition, the P-value for the trend was calculated for response time. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.1.2).

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of the 12320-GZ health hotline

The characteristics of the 9,280 analyzed CMs are summarized in Table 2. Overall, 65.84% of the residents were satisfied with the service. The majority of the CMs were processed at the hospital level (83.2%), were complaints (64.1%), and were related to clinical quality (56.0%). Significant differences were observed across all request–response variables between the satisfied and dissatisfied groups (P < 0.001 for all comparisons), indicating that satisfaction was highly sensitive to platform operational characteristics (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variable | Total (N = 9,280) | Dissatisfied (N = 3,170, 34.16%) | Satisfied (N = 6,110, 65.84%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response hierarchy | <0.001 | |||

| Hospital level | 7,721 (83.2%) | 2,802 (88.4%) | 4,919 (80.5%) | |

| Department level | 1,559 (16.8%) | 368 (11.6%) | 1,191 (19.5%) | |

| Response time | <0.001 | |||

| Q1 | 2,782 (30.0%) | 491 (15.5%) | 2,291 (37.5%) | |

| Q2 | 2,086 (22.5%) | 553 (17.4%) | 1,533 (25.1%) | |

| Q3 | 2,360 (25.4%) | 1,041 (32.8%) | 1,319 (21.6%) | |

| Q4 | 2,052 (22.1%) | 1,085 (34.2%) | 967 (15.8%) | |

| Resident's request | <0.001 | |||

| Suggestion | 400 (4.3%) | 113 (3.6%) | 287 (4.7%) | |

| Consultation | 2,933 (31.6%) | 286 (9.0%) | 2,647 (43.3%) | |

| Complaint | 5,947 (64.1%) | 2,771 (87.4%) | 3,176 (52.0%) | |

| Response mode | <0.001 | |||

| Telephone response | 4,664 (50.3%) | 875 (27.6%) | 3,789 (62.0%) | |

| Message response | 4,142 (44.6%) | 2,097 (66.2%) | 2,045 (33.5%) | |

| Alternative response | 474 (5.1%) | 198 (6.2%) | 276 (4.5%) | |

| CM content | <0.001 | |||

| Non-clinical item | 1,113 (12.0%) | 235 (7.4%) | 878 (15.3%) | |

| Systemic issue | 1,114 (12.0%) | 247 (7.8%) | 867 (13.8%) | |

| Clinical quality | 5,197 (56.0%) | 1,791 (56.5%) | 3,406 (55.7%) | |

| Patient safety | 1,856 (20.0%) | 897 (28.3%) | 959 (15.2%) | |

| Facticity verification | <0.001 | |||

| Not accepted | 2,274 (24.5%) | 1,381 (43.6%) | 893 (14.6%) | |

| Partially accepted | 3,100 (33.4%) | 1,208 (38.1%) | 1,892 (31.0%) | |

| Accepted | 3,906 (42.1%) | 581 (18.3%) | 3,325 (54.4%) |

Analysis of the CMs.a

Bold text indicates that the associations were statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Values are expressed as the number of cases (percentages). Statistical comparisons between the satisfied and dissatisfied groups were performed using Pearson's chi-square test. All the statistical tests were two-sided, with the significance level set at P < 0.05.

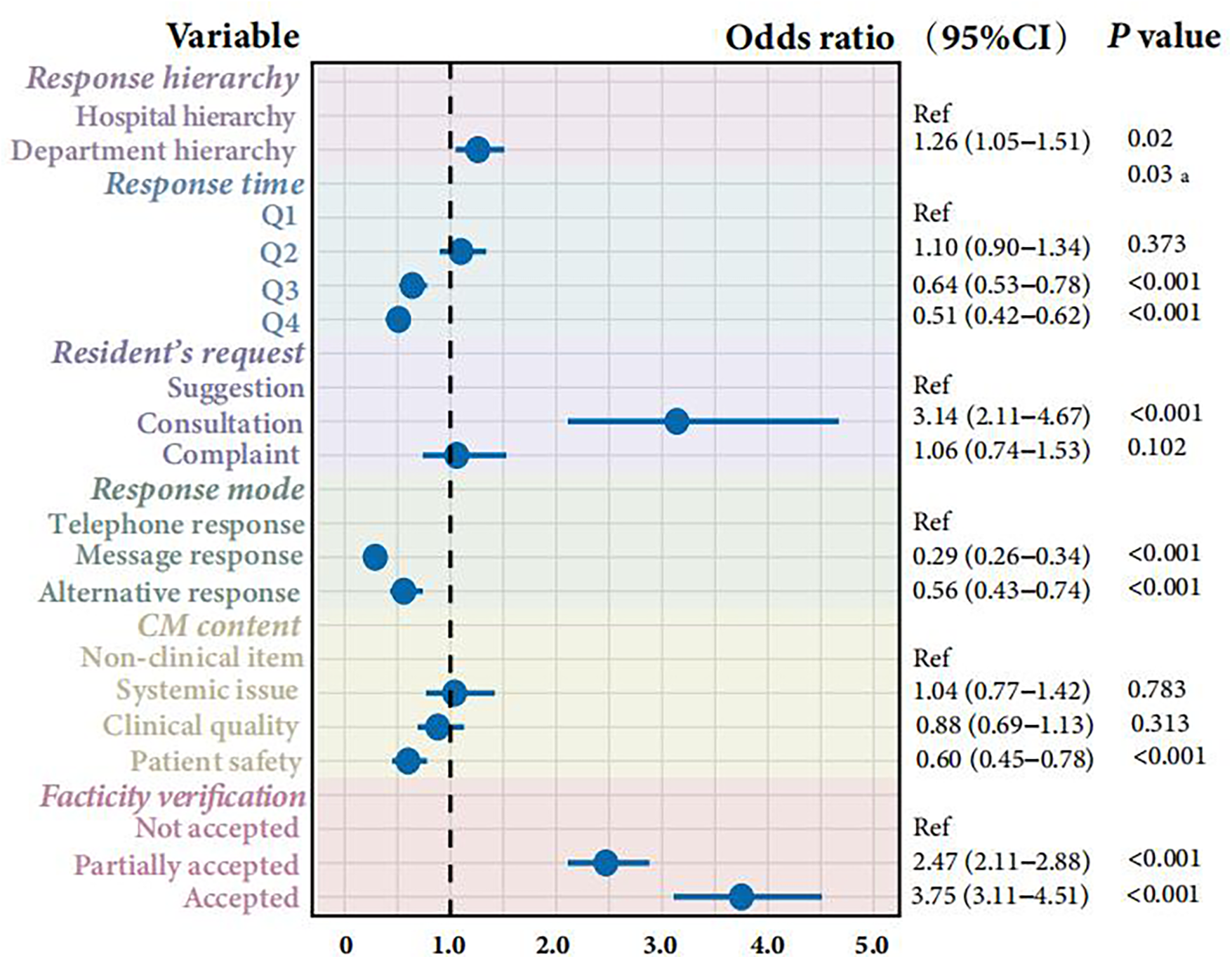

3.2 Request–response characteristics associated with public satisfaction with health hotlines

The multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed significant associations between platform characteristics and public satisfaction (Figure 2). CMs processed at the department level were significantly associated with higher satisfaction compared to those processed at the general hospital level (OR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.05–1.51), suggesting that specialized handling improves user experience. CMs involving patient safety were associated with a 40% lower likelihood of satisfaction compared to non-clinical items (OR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.45–0.78), highlighting patient safety as a critical area of contention. We observed a significant inverse trend for response time, with public satisfaction notably decreasing as the response time increased (P for trend <0.05). Specifically, compared to the quickest response time (Q1), response times in the third (Q3) and fourth (Q4) quartiles were associated with significantly lower odds of satisfaction. Verification status was the strongest predictor. CMs that were “accepted” (fully verified) had significantly higher odds of satisfaction (OR = 3.75, 95% CI 3.11–4.51) compared to those that were not accepted.

Figure 2

Forest plots of the associations between the request–response characteristics and public satisfaction. P-value for trend that was tested by including the median of each quartile of response time as a continuous variable in the models.

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary

This study revealed that the level of satisfaction with this health hotline platform was higher when CMs were handled at the departmental level, were responded to via telephone, were addressed promptly, and were properly verified. However, CMs involving patient safety were associated with lower satisfaction. To date, our study is the first globally to report on the associations between the request–response characteristics of health hotline platforms and public satisfaction, providing empirical evidence for optimizing digital health governance.

4.2 Satisfaction and response hierarchy

This study revealed that directing CMs to specific departments rather than general management offices increases public satisfaction. This finding aligns with international triage models, such as the UK's NHS 111 service, which utilizes the “NHS Pathways” system to escalate complex clinical cases from call handlers to clinical advisors or specialists (15). This tiered response mechanism ensures that patients receive care appropriate to the urgency and complexity of their condition.

Assigning CMs to specific departments in hospitals promotes a more targeted and precise process. This reflects the core competency of “systems-based practice,” which requires professionals to understand the larger organizational context and effectively mobilize resources to provide optimal coordination of care (16). Therefore, training for hotline staff should extend beyond clinical knowledge to include competencies in health system navigation and resource allocation. Policymakers should develop strategies to regulate institutional standards and ensure that residents’ inquiries reach the most appropriate provider efficiently, thereby building trust in the digital health infrastructure.

4.3 Satisfaction and response time

Our study revealed that satisfaction increased when response times were quicker than 10 days but dropped significantly after 13 days. This “satisfaction window” highlights the urgency of efficient triage.

However, not every CM can be resolved quickly, especially those involving complicated investigations. Research on healthcare complaints indicates that patients often perceive unexplained delays as institutional apathy rather than procedural necessity (17). The “Principles of Good Complaint Handling” by the UK Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman suggests that keeping the caller informed of the investigation status is a proven strategy to manage expectations and maintain trust, even when the resolution is delayed (18).

4.4 Satisfaction and CM content

Our study found that CMs related to patient safety had the lowest public satisfaction. This likely stems from the high emotional stakes and complexity inherent in safety incidents. Complaints involving safety often reflect breakdowns in care or medical errors, leading to patient distress that is difficult to alleviate through standard hotline responses.

This finding has profound implications for medical education and staff training. According to the WHO’s Multi-professional Patient Safety Curriculum Guide, effective communication is crucial when managing safety incidents (17). To improve satisfaction in this domain, we propose the following three educational priorities for hotline staff.

First, staff require training in active listening and de-escalation techniques to handle distressed callers. Research has consistently shown that empathy is strongly correlated with patient satisfaction and can mitigate the negative impact of adverse events (19). Second, hotline staff serve as the “sensor” for system-wide risks and, thus, training should empower them to identify “red flag” safety issues immediately and trigger appropriate escalation protocols, rather than offering generic responses. Third, for management, low satisfaction in safety cases suggests a need for systemic learning. Platforms could utilize root cause analyses of these complaints to improve quality, transforming individual grievances into organizational learning (20).

5 Strengths and limitations

This study offers a unique research perspective by analyzing the associations between request–response characteristics and public satisfaction with a health hotline in a large sample from Guangzhou, China. These findings provide a paradigm for improving communication via health hotlines.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, as a core city in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area, Guangzhou's large population made the data valuable for gaining insights to enhance the quality of health hotlines and public satisfaction. However, the findings may not represent the experiences of all residents across the country, especially those living in rural or less developed regions who may lack access to official hotline platforms or have different health concerns.

Second, the response rate for the satisfaction survey was 34.4%. Although this response rate may introduce potential non-response bias, the substantial sample size (n = 9,280) provides adequate statistical power for the analysis.

Third, owing to the protection of residents’ personal privacy, we were not able to collect data on the individual demographic characteristics of the respondents, which may influence individual satisfaction levels. Given that our study focuses on the impact of the platform's request–response factors on public satisfaction, the absence of individual-level data does not significantly undermine the validity of the study.

6 Conclusion

Our findings establish the critical role of request–response characteristics in determining public satisfaction with health hotline platforms, offering novel evidence for optimizing digital health governance. Practically, to enhance service quality, healthcare administrators should prioritize establishing specific departmental workflows for complex clinical cases rather than general handling. Furthermore, hotline staff require specialized training in patient safety competencies and active verification protocols to manage the high expectations associated with clinical inquiries. Further research is needed to develop standardized benchmarks for health hotline operational mechanisms, ensuring that communication is not only timely but also targeted, articulated, and effective.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study are subject to the following licenses/restrictions: the data that support the findings of this study are available from the 12320 Health Hotline Department of the Guangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the 12320 Health Hotline Department of the Guangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to JW at 342133376@qq.com.

Author contributions

SS: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XB: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. ZW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the General Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning of Guangdong Province 2022 “Research on the Systematization of Public Health Emergency Management under the Coordinated Governance of ‘Medical Prevention and Management’ in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area” (Grant No. GD22CGL16). This work was supported by the Guangzhou Science, Technology and Innovation Commission > Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project 2023 “Public Risk Perception, Psychological and Behavioral Surveillance and Early Warning During Major Public Health Emergencies” (Grant No. 2023A03J0463).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the staff of 12320-GZ, who gave their valuable time to participate in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdgth.2026.1702945/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CM, calls and messages; 12320-GZ, 12320 Health Hotline in Guangzhou

References

1.

Platonova EA Qu H Warren-Findlow J . Patient-centered communication: dissecting provider communication. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. (2019) 32:534–46. 10.1108/IJHCQA-02-2018-0027

2.

Johnson LL Muehler T Stacy MA . Veterans’ satisfaction and perspectives on helpfulness of the Veterans Crisis Line. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2021) 51:263–73. 10.1111/sltb.12702

3.

Gonçalves-Bradley DC Maria ARJ Ricci-Cabello I Villanueva G Fønhus MS Glenton C et al Mobile technologies to support healthcare provider to healthcare provider communication and management of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2020) 2020:CD012927. 10.1002/14651858.CD012927.pub2

4.

Clinton-McHarg T Paul C Boyes A Rose S Vallentine P O’Brien L . Do cancer helplines deliver benefits to people affected by cancer? A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. (2014) 97:302–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.09.004

5.

Zabelski S Kaniuka AR Robertson R A Cramer RJ . Crisis lines: current status and recommendations for research and policy. PS (Wash DC). (2023) 74:505–12. 10.1176/appi.ps.20220294

6.

Kristal R Rowell M Kress M Keeley C Jackson H Piwnica-Worms K et al A phone call away: New York’s hotline and public health in the rapidly changing COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive commentary about New York City health+hospitals clinician-staffed COVID-19 hotline. Health Aff. (2020) 39:1431–6. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00902

7.

Arafa M El Ansari W Qasem F Al Ansari A Al Dosari MAA Mukhtar K et al Reinventing patient support and continuity of care using innovative physician-staffed hotline: more than 60,000 patients served across 15 medical and surgical specialties during the first wave of COVID-19 lockdown in Qatar. J Med Syst. (2023) 47:77. 10.1007/s10916-023-01973-w

8.

World Health Organization. Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening – Executive Summary. Geneva: World Health Organization (2019). Available online at:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-19.8 (Accessed January 2, 2026).

9.

Gallagher TH Mazor KM . Taking complaints seriously: using the patient safety lens. BMJ Qual Saf. (2015) 24:352–5. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004337

10.

Mirzoev T Kane S . Key strategies to improve systems for managing patient complaints within health facilities – what can we learn from the existing literature?Glob Health Action. (2018) 11:1458938. 10.1080/16549716.2018.1458938

11.

Li X Shu Q Kong C Wang J Li G Fang X et al An intelligent system for classifying patient complaints using machine learning and natural language processing: development and validation study. J Med Internet Res. (2025) 27:e55721. 10.2196/55721

12.

Al-Mahrouqi T Al-Sabahi F Al-Alawi M Al Rubkhi M Al Abdali M Al Salmi M et al Assessing usability and satisfaction of telephone-based psychiatry consultations in Oman: a cross-sectional study. Front Digit Health. (2025) 7:1563180. 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1563180

13.

Cerulli C Missell-Gray R Harrington D Thurston SW Quinlan K Jones KR et al A randomized control trial to test dissemination of an online suicide prevention training for intimate partner violence hotline workers. J Fam Violence. (2023):1–14. 10.1007/s10896-023-00533-7

14.

Car J Ong QC Erlikh Fox T Leightley D Kemp SJ Švab I et al The digital health competencies in medical education framework: an international consensus statement based on a Delphi study. JAMA Netw Open. (2025) 8:e2453131. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.53131

15.

Anderson A Roland M . Potential for advice from doctors to reduce the number of patients referred to emergency departments by NHS 111 call handlers: observational study. BMJ open. (2015) 5:e009444. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009444

16.

Health systems science. (2020). Available online at:https://shop.elsevier.com/books/health-systems-science/skochelak/978-0-323-69462-9 (Accessed January 3, 2026)

17.

Reader TW Gillespie A Roberts J . Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf. (2014) 23:678–89. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002437

18.

Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman. Principles of Good Complaint Handling. London: Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) (2009). Available online at:https://www.ombudsman.org.uk/ (Accessed January 3, 2026).

19.

Luetke Lanfer H Reifegerste D Weber W Memenga P Baumann E Geulen J et al Digital clinical empathy in a live chat: multiple findings from a formative qualitative study and usability tests. BMC Health Serv Res. (2024) 24:314. 10.1186/s12913-024-10785-8

20.

Kellogg KM Hettinger Z Shah M Wears RL Sellers CR Squires M et al Our current approach to root cause analysis: is it contributing to our failure to improve patient safety? BMJ qual saf. (2017) 26:381–7. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005991

Summary

Keywords

health hotline, medical quality, patient satisfaction, telehealth, telemedicine, telephone

Citation

Sun S, Lai J, Wang J, Bai X, Wang Z, Liu R and Hu R (2026) Request–response characteristics and public satisfaction with using a health hotline. Front. Digit. Health 8:1702945. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2026.1702945

Received

27 September 2025

Revised

03 January 2026

Accepted

08 January 2026

Published

13 February 2026

Volume

8 - 2026

Edited by

Dari Alhuwail, Kuwait University, Kuwait

Reviewed by

Asmaa Abdelnasser, Ibn Sina National College for Medical Studies, Saudi Arabia

Fernando Araujo, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João (CHUSJ), Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Sun, Lai, Wang, Bai, Wang, Liu and Hu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: ZhiWei Wang 625456616@qq.com RuQing Liu liurq@mail.sysu.edu RuWei Hu huruwei@mail.sysu.edu.cn

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

† Present Address: ZhiWei Wang, Guangzhou Health Education and Promotion Center, Guangzhou, China

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.