- History, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John’s, NL, Canada

Women owned a quarter of all rental units in Montréal, QC, Canada, in 1903, a city where 85% of the population were tenants. In no major city in the world today, do women control an equivalent area of the formal economy. This paper asks did the gender of proprietorship matter? It answers this through a series of tests linking a 30% sample of all immigrant-headed households in the 1901 census with a complete historical GIS of all properties and their owners in the city for 1903. The paper plays special attention to Ashkenazi Jews, Syrians, Chinese, and Italians, as these relatively recent immigrants constituted a major break with the largely British and French ancestry of the majority of the population in this 300-year-old settler colony. It then links the patterns in the sample to an index of all households in the census, to explore how these immigrant families integrated into the larger host communities. The paper shows that landladies and landlords had differing practices with regard to overcrowding and to the enforcement of segregation. The paper makes a sustained argument for rethinking how we should approach the relationship between gender and property.

In 1903, women owned a quarter of all rental properties in Montréal, a city where 85% of the 270,000 residents were tenants. A further 1 in 12 rental units were owned by estates, where women might well have shared in management decisions (Sweeny, 2014b). From the perspective of the present, such a high rate of female ownership appears quite extraordinary, but there is a growing body of literature that suggests it might not have always been so unusual (Baskerville, 1999, 2008; Inwood and Van Sligtenhorst, 2004; Morris, 2005).

This article attempts to answer a simple question: Did the ownership of rental properties by women matter? Or, did this formal ownership and control of almost a third of all rental units in Canada’s largest city count for little, as their husbands, sons, or other male relatives, aided by the occasional professional property manager or notary, would have managed these women’s properties.1

There is much to suggest in the laws and customary practices in turn of the century Quebec that a subordinate role for women, particularly but not exclusively married women, would have been the norm. While the default marriage regime was community of property, the husband was legally empowered to assume all management responsibilities of the community. Under the provincial civil code, women could own property as their “propre” (quite literally their “own” in both senses of the term), but all revenues accrued to the community managed by their husbands (Gerin-Lajoie, 1902). Any sales of real property did require the wife’s consent, but in a society increasingly marred by domestic violence any exercise of that veto would have come at an undoubted risk (Harvey, 1991).2 Notarized marriage contracts establishing a separation of property between future couples were possible, but they were frequent only among bourgeois Protestants. Furthermore, they were often used to restrict the wife’s dower rights to a pre-fixed amount, while establishing by contract a legal regime that mimicked the English common law’s subsuming of the wife in the legal personage of her husband (Bradbury, 2011). Thus, while women legally owned in whole, or in part, from a quarter to a third of all rental properties in the city, it is not self-evident that they controlled these properties.

If the question is clear, how best to address it is not. Here, I have opted for an analysis of a particular subset of the rental units owned by women. Using the historical GIS research infrastructure known as Montréal, l’avenir du passé (MAP),3 I selected all the immigrant households from the 1901 census and then analyzed in some detail nine differing immigrant populations. My choice to focus on immigrants reflects the importance of differing forms of segregation in the city. Over the last half of the nineteenth century, Montréal had become a city marked by strong spatial segregation along both religious and linguistic lines (Lewis, 1991; Gilliland et al., 2011). By 1880, the city had become spatially divided into three ethno-cultural groups: French-Canadian Catholics, English-speaking Irish Catholics, and English-speaking Protestants (Olson and Thornton, 2011). An immigrant family’s choice of where to live would have been circumscribed by these already existing and powerful forms of discrimination.

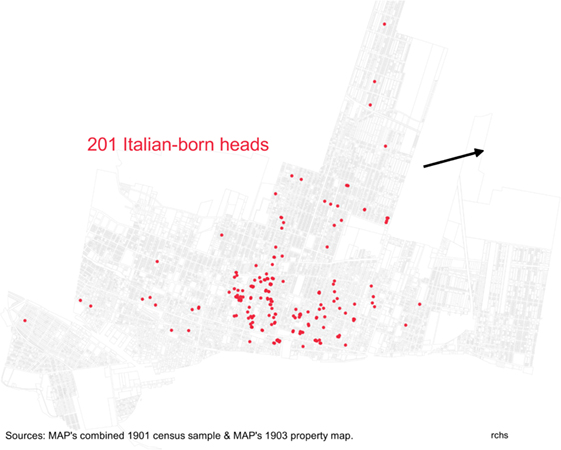

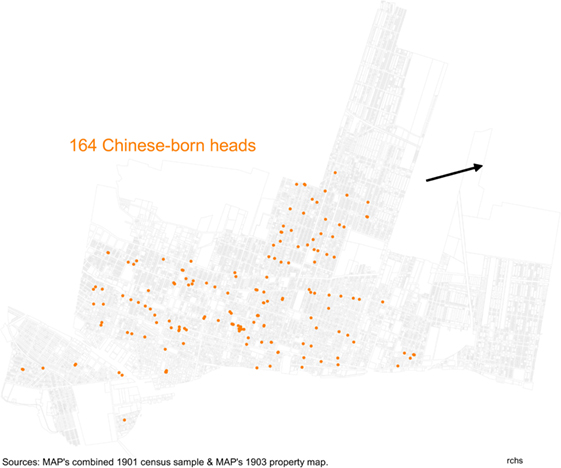

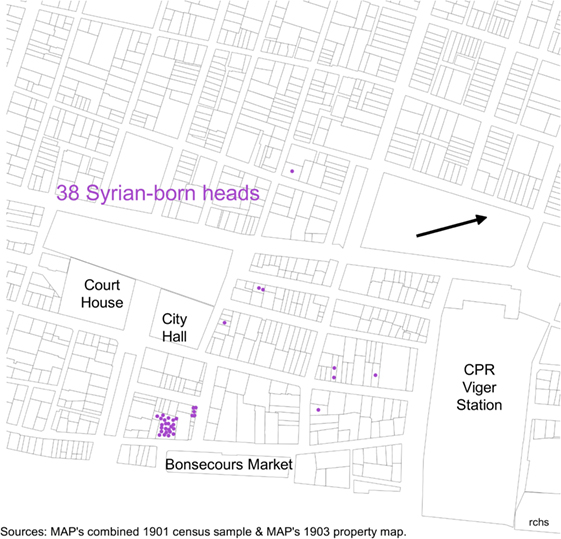

I examine literacy levels, relationships to the job market, and incomes of immigrant household heads, as well as their household incomes. Each of the immigrant groups examined exhibits substantial internal differentiation. For those with cultural, ethnic, or historic ties to one of the three major groups in the city, their own histories appear to have deepened the city’s internal divisions. However, four of the groups examined did not have such ties, and for this reason, these Chinese, Italian, Syrian, and Ashkenazi households are selected out for closer examination. The spatial distribution of each of these four groups is quite distinct. I examine how the gender of the proprietor might have influenced these patterns. I pay special attention to the vexed question of overcrowding, which I argue was a gendered issue, before examining if the proprietor’s gender had any affect on those who chose to live at some distance from the main concentrations for their particular group.

Although the diversity of these tenant households provides richly textured test cases to see how landlords and landladies4 acted, this paper does not allow for an historical explanation. This important limitation to the present study is due to the nature of the sources I use. Neither census returns nor tax rolls are eloquent on motivation. The evidence in these sources is best used for description, not explanation. Understanding these limitations is fundamental to the larger question this study raises, and so I start with a discussion of how these century old sources have been transformed by their integration into an historical geographic information system, before outlining the conundrum their usage poses. I return to this epistemological challenge in my concluding reflections. I argue that we really do need to understand how and why knowledge of such widespread participation by women in the formal economy could have been lost from both popular and scholarly memory, before we can properly answer the larger questions of causality and motivation.

Sources

This study uses parts of the fourth of six layers in MAP’s historical GIS of the city of Montréal. Those parts draw on two sources initially created, respectively, by the federal government in 1901 and the municipal council in 1903, but both have undergone very substantial transformations by MAP.

The 1901 decennial census of Canada is one of the most studied censuses in modern history and, as Montréal was then the economic capital and largest city of the Dominion, its returns have received a disproportionate share of historical attention.5 Realizing this was the case, MAP approached all the researchers we knew who had sampled this census and asked for copies of their databases. They all cooperated and the result, after a considerable editing job to address duplicate entries and completion of missing fields, is a combined sample of 16,111 of the city’s 51,297 households. At 31%, our sample is more than six times the size of the largest previously available public dataset.6 We complement this sample with a much more limited database that provides basic information on the entire island’s population: 70,076 households in which 370,242 people resided.

In 1901, the enumerators asked a complex series of questions, most of which were only partially answered. Three series of questions relating to ethnicity, income, and literacy and language are of particular importance for this paper. I selected the 4,300 individuals who were described as being a head of household and who also provided a year when they immigrated to Canada. I then culled household size and data on earnings for these immigrant-headed households from the larger sample. Finally, using locational information, I linked these households to all those sharing the same lot in the complete census.

The second major source is a 1,340 page publication of the City Council which listed in considerable detail the proprietors of every lot in the city, along with the cadastral and sub-division numbers, the dimensions, the area, a standardized value per square foot of land, the resultant value of the land, the associated civic addresses, an appraised value of all buildings on the property, the religion of the proprietor for purposes of the confessional school tax, and if the property was exempt from tax. The detailed personal information provided on each owner allows them to be uniquely identified, despite the frequency of common surnames. Council stated that the purpose of this exceptional publication was to encourage speculation in real estate.7

In 2006 and 2007, working with the historical demographer Patricia Thornton, MAP scanned and OCR’ed the document page by page. Patricia “stitched” the adjoining two page tables back together in a spread sheet for initial editing. I then exported the resultant table to a relational database for final editing and proof reading. This database became the basis for a number of my presentations to national and international conferences (Sweeny, 2007b,c, 2010, 2013). Then, starting in 2011, I undertook the creation of a geo-referenced layer to map this database. The spatial dynamics revealed so far has proven the value of this particular piece of research infrastructure.8

This geo-referenced map is the primary source used in this paper. And by this, I do not mean just that the map is my preferred way of presenting data, but that it is through the map that data coming from our two datasets described earlier, both based on the same census, are linked. To date, we have linked 87% of all households in the city to the map. I was able for this paper to raise that level to 98% for the 4,300 household heads in our sample who provided a year of immigration. Thus, this paper focuses on the 4,201 immigrant-headed households I have successfully linked to the map.9

The analytical priority I accord to the spatial reference of the lot is conceptually important. I am not analyzing immigrant-headed households in the abstract, but rather those households I have been able literally to ground on a particular lot. This permits a contextual analysis of this subset of the sample that, as we shall see, goes well beyond the limitations of the sample itself.

An Epistemological Conundrum

Influenced by social science, many historians would think of these sources as routinely generated nominal series. Furthermore, again inspired by our sister disciplines, social and economic historians would then apply statistical methods to identify not just patterns in the data but to deduce causal relationships. For reasons I have detailed elsewhere, I do not practice this social science history (Sweeny, 2015b). Rather, I think that when developing discourses of proof in history, we should distinguish between phenomenal and epiphenomenal evidence. Is the source the product of the historical changes we seek to explain or not? If so, then its internal historical logic might well allow the evidence to be used in a test of our hypothesis of causality. If not, then the evidence is best used for description, rather than explanation.

Now, the question that is at the heart of this study is: Did the gendered ownership of urban rental units matter? Neither of the sources I am using can be argued to have the direct product of this gendered relationship. However, the internal organization of both does speak to the centrality of gender relations in how these governments understood and attempted to bring order to their incoherent worlds. We should not mistake their constructions for historical reality. Rather, we need to recognize how gendered inequalities shaped the very evidence we have to work with. As Curtis (2002) observed, governments do not take censuses; they make them up. The fictional character of both sources used here is important for us to remember, lest we fall into the sort of a-historical explanations that have so marred my generation’s economic history (Boldizzoni, 2011).

If we need care in drawing conclusions about patterns apparent in either source, we need to exercise even greater caution when drawing connections between the two. For none should be thought of as the product of turn of the century Montréal; all such linkages have been created in and through twenty-first century historical theory and method. In short, we need to add a considerable dose of self-reflectiveness on our own constructions to the critical awareness that we bring to the constructions of past governments. Such an explicit recognition of our own historicity is vital to any successful resolution of this epistemological conundrum. As these cautionary words suggest, the motivations for any gendered differences revealed in the following analysis is currently beyond my ken. Minimally, it would require the analysis of quite different sources and a much greater contextualization of the social, cultural, religious, and gendered tensions within this society than I am presently capable of providing.

Immigrant-Headed Households

By 1901, Montréal had for the previous 70 years been the largest city in the most important settler colony of the British Empire. According to the census, this 258-year-old city was entirely populated by immigrants and their offspring. Even if this says more about how racist conceptions of “Indians” shaped government record-keeping (and so much more) than it does about the actual population, more than 90% of the listed residents were identified as Canadian-born, and over 95% of those could trace their origins back to either France or the British Isles. But, things were changing. The number of immigrant heads of household from one of the “two founding peoples”10 had dropped below 75% for the first time in the almost 300-year history of this settler colony.

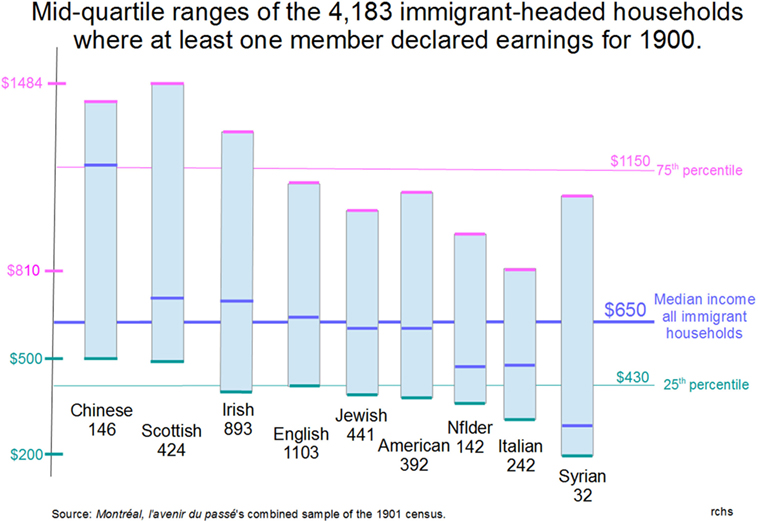

Table 1 profiles the principal immigrant groups retained for analysis here. They account for 94% of all immigrant-headed households in the 1901 census. They include the seven largest groups by country of origin, as well as two more diverse groups.11 Under Ashkenazi, I have regrouped the Jewish population drawn from Eastern and Central Europe. There was a well-established Jewish community in the city dating back to the 1760s, but it was Sephardic. I have also chosen to include the newest and ninth largest group by place of birth: the Syrians. The first of whom arrived in 1890, a forerunner of the estimated 600,000 Syrians who would immigrate to the Americas prior to the Great War (Karpat, 1983).

While three-quarters of all selected heads had immigrated by 1891, the majority of all non-“founding peoples” arrived in the 1890s. Both the youth and the small size of the Syrian and Chinese households hint at the qualitatively differing dynamics within these the most recent immigrant groups. Complexity characterized the Syrian families, while the Chinese lived in households not families.12 By contrast, the early date by which so many of the Irish had arrived means many would have immigrated as children and so might well be considered as the second-generation immigrants. The combination of a relatively early arrival and a considerably older median age of the Scottish-born heads also should be kept in mind when viewing my results.

The enumerators asked four different questions about ethnicity: What is your place of birth? What is your race? What is your nationality? What is your religion? People born in Canada were asked a supplementary question about whether they were born in a rural or an urban setting, whereas people born elsewhere were asked their year of immigration and their year of naturalization if any. In answer to the first question, people generally provided either a province within Canada or a country. The entries for “race” reflected essentialist understandings of the day, so what we might now think of as an ethnicity or a nationality was what was most often listed.13 A separate column queried people’s “color,” but under “race” “African” was entered for Blacks. In the Montréal returns, nationality was listed as being Canadian if the person was born in the country, a naturalized British citizen (there was no Canadian citizenship until after the Second World War), or born in the British Isles. Almost all other entries, save for the Jews, were left blank. The detailed answers to the religion question spoke to the complexity of the various forms of Protestantism practiced in the city. Only a handful of household heads studied here refused to state a religion, although there were two agnostics and an atheist.

The variety of questions asked does permit the construction of ethnic identities that build on a combination of variables. While I have retained the diverse responses for use in subsequent analysis, I chose to limit my initial definition of the groups to place of birth. I did so in the hope I could avoid presenting the government’s essentialist reasoning as an accurate reflection of reality. The exception is the Ashkenazi Jews, where I have constructed an identity that is not in the source. What is in the source is ample evidence that Jews from Eastern and Central Europe were considered differently from all other immigrants by the enumerators. For example, despite knowing their specific country of birth the enumerators inscribed 412 of them as “Hebrews,” “Jews,” or “Jewish” under “race.” The only major exception was the 34 people who gave their religion as Jewish and were born in Germany, two-thirds had “German” entered as their “race.”

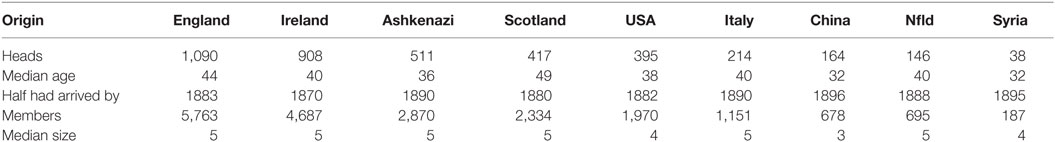

The enumerators asked the heads of household to identify their social relations and those of the household members using four options: living on their own means, employee, employer, or by their own account. These were not mutually exclusive categories, and there were within every group employers who said they also worked on their own account. The graph of Head’s declared social relations not only shows how people said they earned their living but also illustrates how varied the response rates were within the various groups (Figure 1). For a number of them, the rates are so low that we should not place too much emphasis on any apparent patterns.14 Nonetheless, one can clearly see the importance of peddling and other forms of self-employment among the Jews and the Syrians. The enumerators also asked if the heads practiced a trade other than their stated occupation. They were then asked what their annual earnings were in 1900 from their principal occupation, as well as from any other occupations. People who lived on their own means or worked on their own account normally did not provide any information about their earnings nor did many employers. Thus, one needs to exercise considerable caution with these figures. They represent as accurate a picture of wages as we are likely to have for the period, but they do not constitute a basis for an analysis of income inequalities.

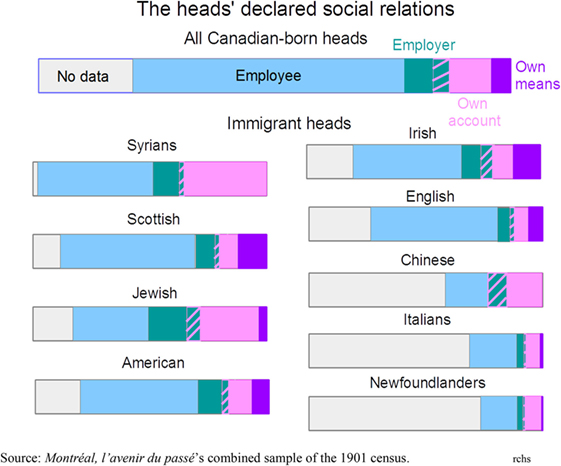

My graph of earnings by household head reveals remarkably broad variations across the differing immigrant groups (Figure 2). I present them in the order of their median earnings, from $600 for the Scottish and Chinese to a mere $200 a year for the Syrians. However, this relative success of the Chinese may be more apparent than real, for note that both their median and their 75th percentile are exactly the same. A third of all Chinese household heads stated $600 was what they earned in 1900. This contrasts sharply with the wide spread between this median and the 25th percentile of Chinese, the largest such range for any of the nine groups. Of the new immigrant groups, the Jews reported the best overall earning profile: with their 25th percentile second only to the Scottish and their 95th percentile ranking third. Quite unexpectedly, they report doing as well as the English-born heads. The Irish present a quite different profile than other immigrants from the British Isles, and this despite the fact that many of them would have been second-generation Canadians.15 Perhaps the relatively large number of people living on their own means, as with the Scottish a reflection of their older age profiles, meant an apparently worse situation than was in fact the case.

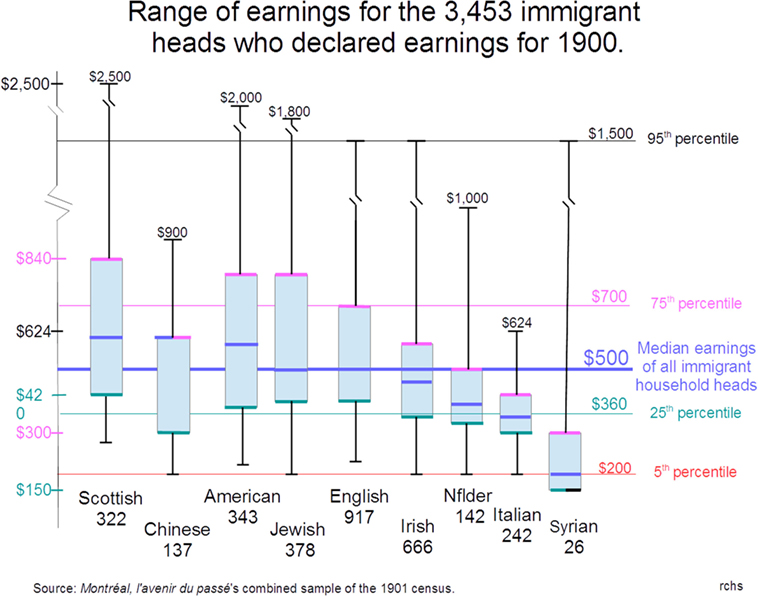

On the other hand, the situation for Italians, Syrians, and, somewhat surprisingly, the Newfoundlanders was unambiguous and qualitatively different. Much narrower ranges characterize all three groups, but with their 75th percentiles well below the median for all immigrant heads, the Italians and Syrians faced particularly hard times. Earning less than a dollar a day in 1900 was to live in dire poverty. All of the Italians and the Newfoundlanders declared earnings for 1900, they were the only groups to do so (Figure 3). This contrasts sharply with their under reporting on social relations and is probably a more accurate representation of the significance of waged labor for these two groups.

Male breadwinner ideology notwithstanding, these largely working-class households did not depend solely on their head for earnings. As the graph of mid-quartile ranges shows, when the earnings of all household members are included, the situation changes significantly. Median income for all save the Syrians rises by more than $120. While a quarter of the households of all groups, save the Italians and Newfoundlanders, declared annual earnings of $1,000 or more. This dramatic improvement was in part the result of more households reporting. Relatively affluent households, where the head had not declared earnings, often were home to other family members who earned good incomes. Homes where the head was effectively retired also would see major gains in earnings by including the wages or salaries of other household members. Even relatively poor working-class homes could see a major improvement simply by the fact that if they took in a lodger their income was often declared. Indeed, in a number of the Syrian households, the head declared little or no earnings, and so the earnings posted here were those of their lodgers. Thus, a complex set of relationships are subsumed in this graph and that is why I did not include any data on the upper and lower quartiles. Wealthy families would have been considerably wealthier than the declared earnings would indicate, while many of the apparently lowest income households would be because the only household member declaring any earnings was a domestic servant.

The exceptional results for the Chinese households do call for an explanation. Here, almost every member of the household declared earnings for 1900. Generally, $300 dollars for most lodgers and from $500 to $600 for the head. Almost all of these men worked as laundrymen. Often they lived in hostels, the largest of which had 102 residents with combined earnings of $31,600. Only an English-born hotel manager, who listed the earnings of his staff and a number of his resident guests, managed to top that with a declared household earning of $40,628. As we shall see, this was not the most surprising difference shown by the Chinese.

The admittedly exceptional situation of the Chinese underscores an important fact of life that was true for the majority of immigrant-headed households and for even larger numbers in the recently arrived groups. It took the efforts of an entire household to achieve a reasonable standard of living. Despite their labors, many would not achieve even this; particularly, it would appear among the Syrians, Italians, and Newfoundlanders. However, most would through this collective effort achieve something similar to the norms prevailing among Canadian-born families.16

This raises the question of integration, and the census returns does have some things to say about if and how these immigrant households fit into their new host societies. People were asked if they could read or write, although the language was not specified. They were also asked if they spoke English or French and what their mother tongue was. Turn of the century, Montréal was a majority French-speaking city, but the wealth and superior social services of its English-speaking Protestant minority had begun to act as a powerful agent of assimilation for immigrants, as they would continue to do until the Charter of the French Language was adopted in 1976 (Sweeny, 1994).

With the exception of the Newfoundlanders, the response rate to the questions on literacy and language paralleled those on social relations. Italians and Chinese largely ignored the questions, save for the one on their mother tongue. With only a little better than one in eight reporting on their ability to speak either English or French, it is difficult to say if the fact that half the Italians heads responding said they spoke French, and only one Chinese head did, is significant or not. Among the other groups literacy rates are uniformly high, all groups reported that two-thirds or more could read and write. While given the subsequent history of the language question in Montréal, there is a surprisingly large opening to French by both native English speakers and those with other mother tongues. Better than two out of the five of the Jewish and Syrian heads said they could speak French, while one in five of the native English speakers said they could, ranging from a quarter of the Irish, to only a tenth of the Newfoundlanders.

From Households to Communities?

Over the course of the last half of the nineteenth century, Montréal had become highly segregated along both linguistic and religious lines, while exhibiting less segregation along lines of social class than had characterized the pre-industrial town.17 Two of my recent papers have shown how in the closing decades of the nineteenth century Protestant landlords played a much more active role in promoting discrimination than did Catholic landlords and that their active exclusion of difference was in greatest evidence among small proprietors and in those city wards that bordered on strongly divergent wards. It was thus into a sharply and recently etched ethnic and religious landscape that the heads of households from central, eastern, and southern Europe moved. They were complemented by smaller immigration streams from greater Syria and south-eastern China. Where did members of these new ethnic, religious, and linguistic communities find a home?18

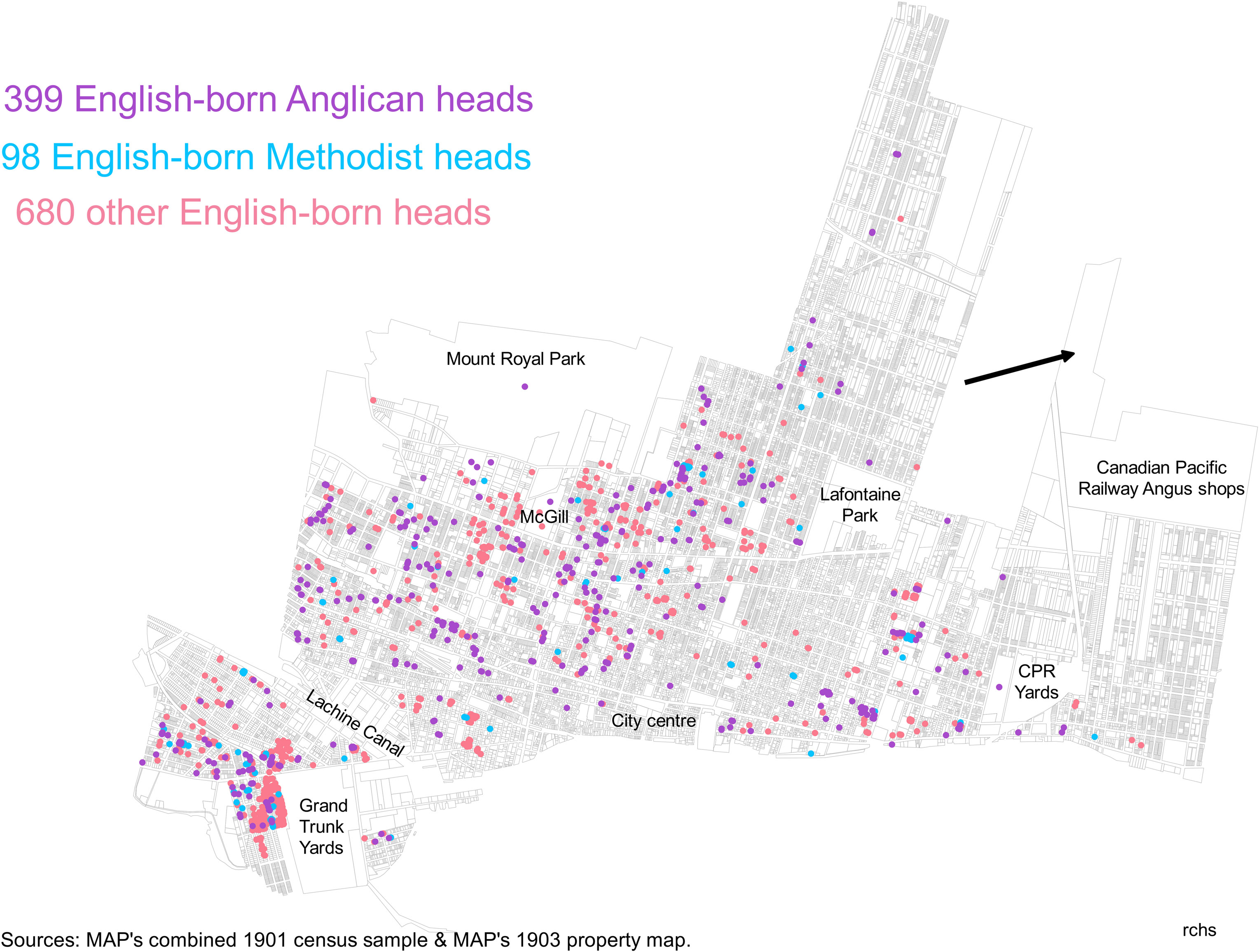

In order to properly contextualize their choices, I start with the immigrants who could claim to be members of one of the “founding peoples.” As is starkly evident in these four maps, English-speaking immigrant-heads settled overwhelmingly in the west,19 but not anywhere in that half of the city. Already existing cultural and religious patterns of segregation within English-speaking Montréal constrained the choices people made. What is also evident, with four of the five groups mapped here, is that pre-existing cultural and religious divisions from their places of origin were grafted onto these local patterns to reinforce sharply delineated lines of segregation.

Among the English-born, there was an exceptional concentration adjacent to the Pointe St-Charles yards of the Grand Trunk Railway (Figure 4). Note, however, the clear vertical line to the west, marking the former boundary of a now absorbed municipality of St-Gabriel, which did not obtain either drinking water or proper sewage until after amalgamation, decades after the Pointe. These largely skilled workers did include some Anglicans and Methodists, but attendees of both Church and Chapel tended to live elsewhere. Indeed, the majority of Methodists households and three in eight Anglican households lived on the same property as another immigrant member of their congregation or parish. Among the Anglicans, this communal solidarity is most in evidence in their small islands in the heavily French-speaking sea of eastern Montréal. Overall, the English do appear to be relatively affluent, with one in six living in the Golden Square Mile area south and west of McGill. Although only slightly more than a quarter of all retained households, they account for a third of those living in this the wealthiest neighborhood in the country. After the Pointe, however, their preferred neighborhood was a recent petty-bourgeois development of largely single family row housing to the east of McGill, now known as Milton-Park.

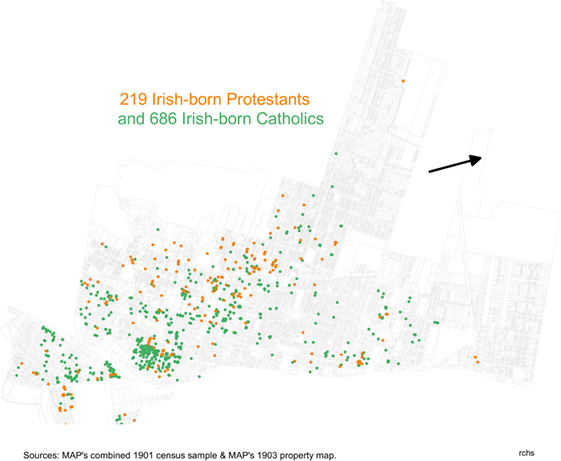

The late-nineteenth century saw a flourishing of the Orange Order throughout British North America, with deadly riots in Newfoundland and New Brunswick and a full-fledged assault on the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Toronto. Montréal was spared the worst of this violence, perhaps because Protestants were always a distinct minority. Nevertheless, the housing choices of the Irish-born immigrants show how significant the Catholic/Protestant divide had become (Figure 5). The line of green dots midway down the map in the west marks the base of the escarpment, above which rose the Golden Square Mile, where Irish Protestant households out-numbered Irish Catholics two to one. To the south, St Anne parish was the historic center of Irish Catholicism in Montréal, which by the turn of the century had crossed over the Lachine Canal to include adjacent parts of Pointe St-Charles, while some had moved further west into the former municipality of St-Gabriel.

The early year of immigration for so many of the Irish must have meant that many arrived as children with their parents and should be considered second generation. Three in 10 Irish-born immigrant heads migrated when they were 14 years or younger. Almost a quarter, 72 of the 280, were Irish Protestants, and they account for the majority who made it up into the Golden Square Mile. Among the second-generation Catholics, we see a different type of mobility. They account for almost half of Irish-born heads residing in the French-speaking eastern and northern wards of the city.

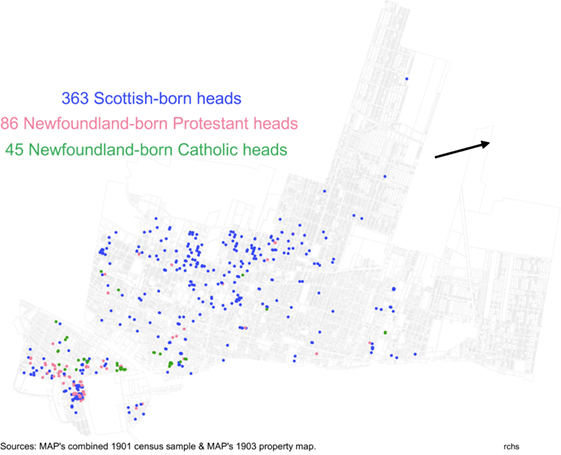

A quite disproportionate number of the Scots, a third, lived in the Golden Square Mile, where they accounted for a quarter of all immigrant-headed households (Figure 6). It was here that the uniquely Canadian architectural form known as Scottish Baronial was born. Only a quarter of these residents were among the 67 Scots who immigrated as children, but here too generational mobility was clearly in evidence. Three-quarters of the second-generation Scottish-Canadians lived above the escarpment, mostly in the largely petty-bourgeois neighborhoods east of McGill and north of Sherbrooke. In contrast, only a handful of the much smaller population of Newfoundlanders made it out of the “city below the hill,” but here too the generation-old divisions between West Country English Protestants and Irish Catholics from the Waterford region clearly made itself felt on the streets of popular class Montréal.

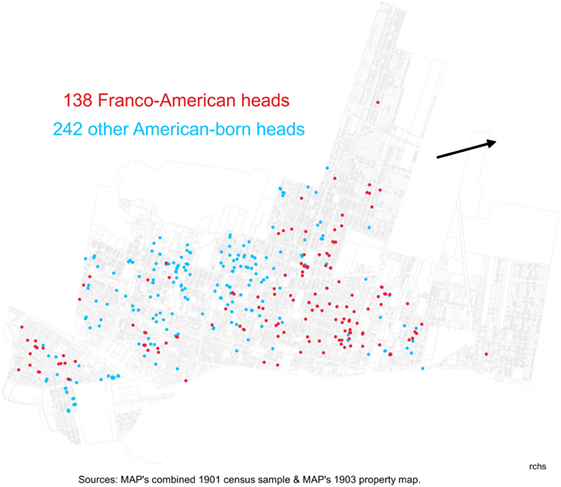

The Americans show how significant language was for the choices that people made (Figure 7). A third of the American-born immigrants were descendants of either Canadien or Acadien settlers. It had been their parents who migrated to work in the textile mills of New England starting in the 1850s. Now, they were starting to trickle back and, not surprisingly, they alone among those who could claim “founding people” status, took up residence in the heart of the city’s majority culture: in St-Jacques and Ste-Marie in the east and to a lesser extent in St-Gabriel and St-Joseph in the west.

Each of the more recent groups had their own distinct settlement patterns. The Italians were located well below the escarpment in the mixed popular class wards of St-Louis and St-Jacques (Figure 8). Over the past 20 years, St-Louis had been the subject of a turf war between English-speaking Protestant and French-Canadian proprietors, which by 1901 the latter had won. This was the only part of the emerging central business district where French was the language of business. It was here, 2 km east of the three major English language department stores, that Dupuis et Frères would build the largest retail business in French Canada. St-Jacques was a hard-scrabble, working-class neighborhood with not very many large factories, but hundreds of jobbers, workshops, and small manufacturers. It was here in the 1860s that the quintessential working-class duplex first came to dominate an urban landscape. The choice of these Italians immigrants to live here in a largely French-speaking environment confirms the suggestion in the partial census returns that they were tending to integrate into this linguistic community, with whom of course they shared a common religion and a similar language structure. At the top of the map, one can see the handful of households who were the pioneers of what, between the wars, would become Montréal’s Little Italy in northern St-Denis ward.

Chinese communities in North America are almost all identified with particular, densely used, “Chinatowns” (Figure 9). These Chinese had migrated from very particular places within South China. Nineteenth and early twentieth century Chinese immigrants to Canada came almost entirely from a handful of townships in Guangzhou.20 It was in this sense, the most organized and also the most limited migration stream of any the groups studied here. Thus, one would expect there to be a spatial concentration that reflected the myriad connections which undoubtedly linked members of this group and one can see, in the lower center of the map the small cluster of hostels on Lagauchetière which corresponds to the city’s embryonic “Chinatown.” Nevertheless, it is the remarkable dispersion of Chinese households across the entire residential landscape of the city that is most striking. Only the largely yet to be developed St-Denis ward to the north and the heavily industrial Hochelaga ward in the east were without their Chinese laundries. After all, everyone regardless of class, religion, or language has dirty laundry.

The greatest contrast to this exceptional dispersion was the housing arrangements of the Syrians (Figure 10). Unique among the groups studied, all of them were located in or very close to the old city center: a short distance on foot from St James Street, the financial hub of the Dominion and even closer to the spanking new CPR station serving eastern parts of the country. No fewer than 23 of the households lived in the venerable Rasco’s hotel on St Paul. Conveniently, this “Aleppo central” was located opposite Bonsecours, the city’s largest market.

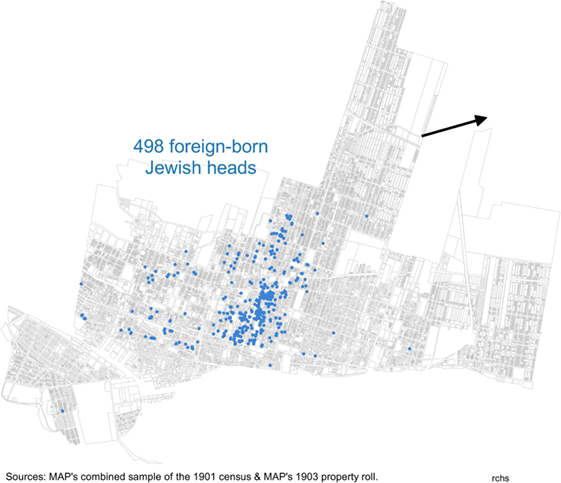

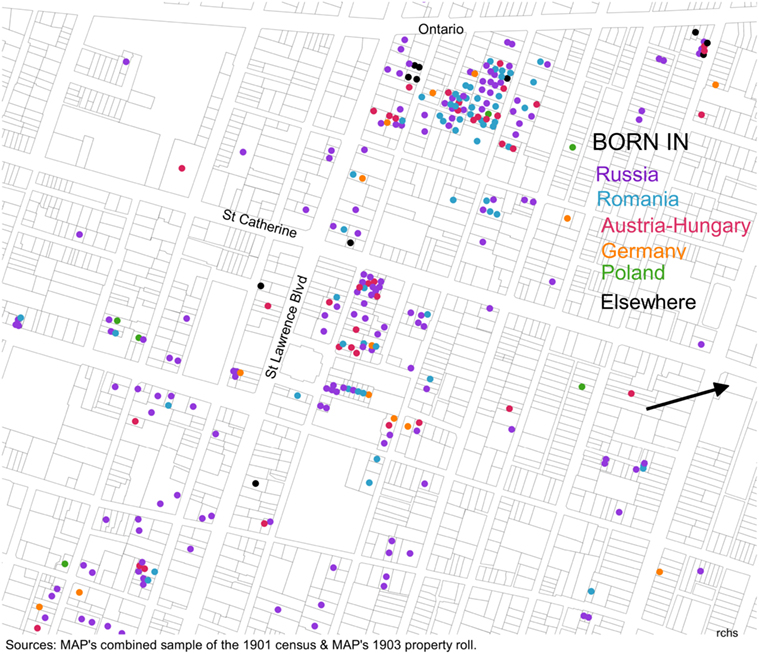

The majority of Jewish immigrant heads were also heavily concentrated in fewer than a dozen city blocks east of St Lawrence Blvd and south of the escarpment (Figures 11 and 12). This was 2 km east of the city’s principal synagogues, both located in the Square Mile where only 3% of these heads lived. The immigrant-headed households were near an older temple on Chenneville, which would be enlarged and rededicated as B’nai Jacob in 1902. Reflective of the distance between these newcomers and the established, largely Sephardic, Jewish community, was when the latter received funding from Baron de Hirsch to build a community center dedicated to the secular education of eastern European Jewry, they erected it where no Jewish families lived, on Bleury midway between the two, in the blank space on the map.

In my earlier work on the history of this wave of Jewish migration to Montréal, I argued that the people experienced a change in identity with their migration to Canada (Sweeny, 2008). I based myself on the heavily national character of the synagogues that the immigrants had created by the early 1920s (Figure 13). Whereas in their country of origin, they would have been a Jew, in Canada they became a Romanian Jew, or a Russian Jew or a Polish Jew (Figure 14). Ironically, I argued, the very national identity that would have been denied them in their country of origin was in their new home what distinguished their particular rites and customs, and so served to define their Judaism. A closer examination of where and with whom these immigrant heads chose to live in 1901 does not lend much support to this earlier interpretation. As can be seen clearly on Figure 14, of the areas where most had settled, cohabitation with fellow Jews was common enough, but this frequently involved Jewish households from other countries.

Figure 13. The city’s most important synagogues in 1900. From left to right, the Temple Shaar Hashomayim, on McGill College Avenue, opened in 1886, the new Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, three blocks further west on Stanley, opened in 1890, and the old Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue on Chenneville after it was enlarged and rededicated as B’nai Jacob in 1902.

Overall, slightly more than half of all Jewish households, 261 of the 498 I can plot on the map, shared their lot with at least one other Jewish household. I think this speaks to questions of agency and of community and not just among the Jewish households. Although we have seen each of the groups had both distinct settlement patterns and its own internal cleavages speaking to complex, contradictory histories stretching back well before these people immigrated to Canada, living in close proximity to others who shared aspects of one’s own culture was how these immigrants adapted to life in their new country and in so doing created new communities. Admittedly, the Jewish households were at the high end for those actually living on the same lot as another household from their community, only the Syrians had a higher percentage. Nevertheless, from a low of 1 in 9 with the American-born, to 1 in 6 for the Scots, through 3 in 10 for the English, and 4 in 10 for the Italians, this practice was certainly not exceptional. It might, of course, be argued that the widely dispersed Chinese shows this not to have been the case, but I would argue it is precisely their dispersal that speaks to shared strategies of adaptation and accommodation that were rooted in a sense of community. Both the existence of the hostels for the recently arrived and the subsequent dispersion in a rational manner that ensured households would not be undercutting each other speak to a strategic coherence that befits the most closely knit of all the groups studied.

On the Gender of Property Owners

Although much more work remains to be done on these households, enough context I hope has been provided to allow for an understanding of both the significance of the agency and the seriousness of the constraints facing these immigrant-headed households. This varying context is important for understanding the nature of the choices that their landlords and landladies were making in deciding to lease to an immigrant household. As the tenants varied, so too did the decisions of the proprietors.

One would not expect there to be a great variance in leasing practices by gender. After all, these men, women, and the institutions they controlled shared important characteristics by the simple fact of their being owners of rental property. By 1903, they came overwhelmingly from the bourgeoisie: petty, middling, and big. Indeed, for many, it was thanks to a multi-generational rentier strategy that they were so affluent. To be sure, the most successful had benefited from highly gendered practices whereby disciplining the marriage choices particularly of daughters had helped to create dynastic lineages of rentier capital, but as this suggests, property was very much a family affair.21

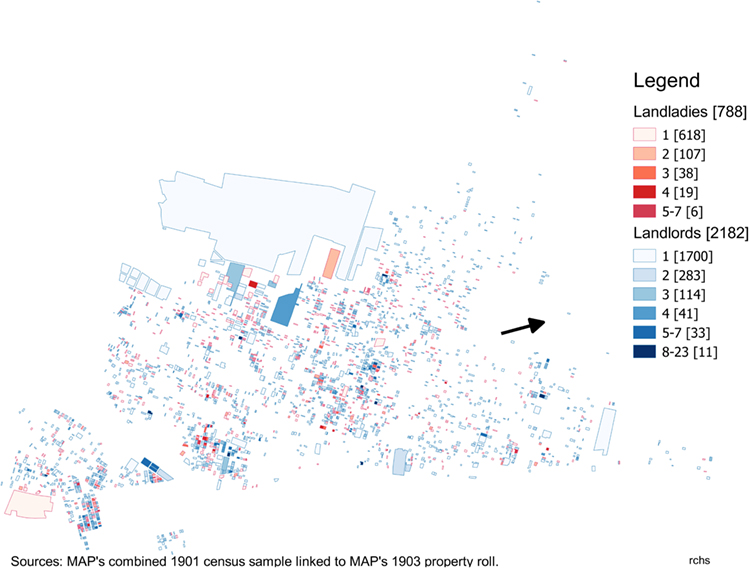

Differing familial practices did informally work to enforce differing inheritance practices, but there were strong cultural and historical forces encouraging equity between legitimate offspring. I do not mean by this that inheritance was gender-blind, quite the contrary. Property-owning mothers and fathers carefully considered gendered social expectations for their sons and daughters when designing their wills and as a result women tended to inherit properties that were more equally distributed in the city and less commercially oriented than their male siblings. Should disputes arise, the civil code foresaw family councils to handle any property disputes. Furthermore, as we have seen, the default marriage regime gave disproportionate power to the men. Finally, since much of the property owned by women was inherited, frequently from a deceased husband, their portfolios were rarely entirely of their own making. Many a landlady’s tenants would have signed their first lease on that property with a landlord. Thus, for these myriad reasons, we should not expect to see significant differences between the leasing practices of men and women and, on first glance, the density of immigrant households by the gender of the proprietor shows remarkable similarities between landlords and landladies (Figure 15).

Owners of 23% of the rental units in the city, women were the owners of 26.6% of properties where an immigrant-headed household in our sample resided. As is clear from the map they owned properties in all of the principal areas where these households chose to live. All three of the most concentrated areas of immigrant housing are clearly visible: west of the Grand Trunk Railway yards in the Pointe for the English, the parish of St. Anne for the Irish, and just east of the Main below Ontario for the Jews. And here, women did own properties, but as with the landlords, the clearest impression created by this mapping is one of spatial breadth. This is largely because in almost four out of the five cases there was only a single immigrant tenant on the property. So, even the eastern wards of the city, which as we have seen were largely shunned by the heavily English-speaking immigrants, appear represented. Only the city center, home to the Syrians and fewer than a dozen other immigrant-headed households,22 is almost blank.

Somewhat surprisingly, properties with heavy concentrations appear in the city’s most bourgeois area, the Golden Square Mile. Here, in all but three cases, these are the mansions of some of the wealthiest people in the Empire.23 Clearly, a number of immigrant-headed households may have made it up into the Square Mile, without making it up the stairs into their own home. The exceptions are the three caretakers’ and the porter’s households on McGill campus; one of the earliest apartment buildings in the city, on Stanley, owned by Roswell Corse Fisher, in whose Sherbrooke street mansion worked two immigrant-headed families; and five contiguous lots owned by Jean François Blanchet on Buckingham that were treated as a single property on the roll.

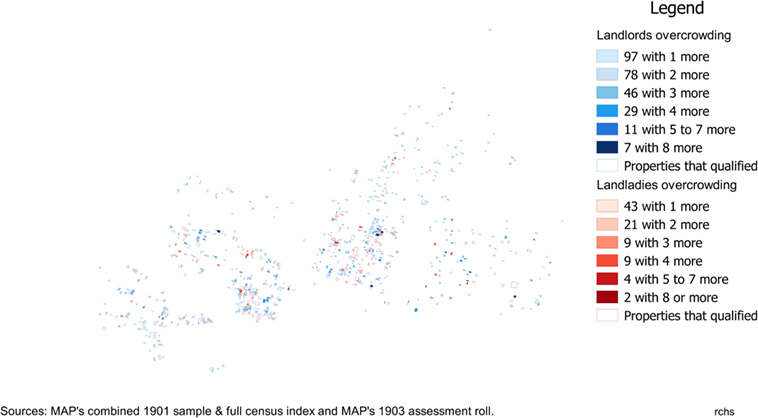

As these anomalies suggest, caution is required in interpreting this map. Nonetheless, a distinct gender imbalance is evident with the most densely occupied properties. While 7 landladies have from 5 to 7 immigrant-headed households on 8 properties, 34 properties owned by men do, and a further 11 have from 8 to 23. None of the properties owned by landladies exhibit this type of concentration. These 41 men are landlords to 311 immigrant-headed households on 45 properties, while the 7 landladies have only 45 immigrant-headed households as tenants on their 8 properties. This suggests the possibility that the vexed question of overcrowding may well be gendered.

Overcrowding has a long and troubled history in Montréal. The two pioneering sociological investigations of the nineteenth century, Jacques Viger in the 1820s and Herbert Ames in the 1890s, were both primarily concerned with this question. In the 1970s, poor housing was key to Terry Copp revisiting Ames’ study in his Anatomy of Poverty (Copp, 1974). While chronic overcrowding for the working class was also a major conclusion of Michael Katz’s ambitious experiment in social science history. Team members Michael Doucet and John Weaver went as far as suggesting that perhaps a third of working-class families in Montréal were forced to share their personal living space with another, unrelated, family.24 Unfortunately, with an oft-read article in the 1980s and a major prize-winning work in the 1990s, this misèrabliste image was reinforced by Bettina Bradbury’s work on late-nineteenth century familial strategies (Bradbury, 1984, 1993); despite the publication of a substantive challenge by the architect-historian Gilles Lauzon during the intervening years.25

Over the last half of the nineteenth century, housing in the city became dominated by triplexes and duplexes. By 1903, they accounted for two-thirds of residential properties. As a result, it was not at all uncommon to have two, three, or four tenants on a single property. Doubled duplexes, as shown in Figure 16, would normally house four families, each with their own door on the street. Triplexes generally did as well, as shown in Figure 17, but it was not infrequent for either a ground floor or a first floor entranceway to open onto a joint, interior, stairway. Nineteenth century census enumerators were instructed to consider households that did not have their own entranceway onto the street as being shared housing. Lauzon convincingly demonstrated that the high levels of doubling-up, reported by the misèrabilistes, were the result of having mistaken this technical classification for an historical reality. He found that doubling-up did occur, in perhaps as many as 3% of households, but he suggested this figure, a tenth that of Weaver et al., was itself somewhat misleading as the census was taken in the spring of the year, just before the May first moving date. Thus, he suggested, families that had recently arrived in the city and were looking for accommodation, and perhaps had already found it but would only be able to access it on May 1, would be considered as cohabiting even though their stay with extended kin or acquaintances was at most a temporary measure.

Recently, Lauzon has returned to this question in his detailed social history of Pointe St-Charles.26 There he argues we need to go beyond the limitations of Ames’ analysis of how many people per room characterized popular class housing – a popular analytical question as the census returns provide both household size and number of rooms – to a more revealing functional analysis: How many rooms served primarily as bedrooms and was there a separate kitchen and living room? This requires reconstructing the demographic composition of the resident families and paying close attention to the built environment, which Lauzon has done for a sample population in the Pointe, and the results he obtained suggests that there was a very significant improvement in housing conditions between 1880 and 1920. It is not possible for this paper to conduct an analysis like Lauzon suggests, although I certainly hope to utilize MAP’s infrastructure to extend his model to other popular class wards of the city in the near future.

What I can do here is analyze the evidence from the property roll, so as to construct a test for the evidence from the census returns. As we saw with the Blanchet property, the roll frequently listed multiple properties together providing all the information for them in a single entry. The highest density housing owned by a landlady was just such a case: the seven immigrant tenants in Anna Mills’ row of eight contiguous units each with its own civic number on Murray Street in St.-Anne. This, like the Blanchet property, is not proof of overcrowding. We need a more rigorous test than a simple linking of census returns to entries on a property roll will allow.

The strip of red properties facing the Grand Trunk yards in the Pointe illustrates some of the further complexities we need to consider. These properties owned by Elizabeth Schofield were part of Sebastopol Row, pictured here after a recent renovation by the municipal housing authority (Figure 18). Dating from the late 1850s, these were the first purpose-built tenements in the city. The roll indicates that she owned 7 lots with even civic numbers from 30 to 76, which suggests 23 units. Census returns detail 26 households from this range of addresses and furthermore, they were not evenly distributed, and so I mapped two lots with five and six tenants, respectively, while others have three or four and one has only two. Is this a case of overcrowding or not?

The roll provides us some guidance in developing an appropriate way of thinking through this problem, for it contains 1,701 entries where in addition to an integer the address included a letter, i.e., 79a, 79b, etc. These letters indicate that these rental units had already been subdivided, but in a way the city found acceptable or was at least hereby recognizing and effectively sanctioning. Landladies owned 23% of both these properties and units. They were, however, under-represented in those involving five or more units on a single property: where they accounted for only 10 of the 75 cases. Rents charged for these “lettered” properties were relatively high. Owners of properties with five or more such units recuperated the cost of their buildings in short order, averaging only six and a half years. Whereas it took on average 7 years and 8 months for the owners of a single duplex or triplex to recoup the cost of their building, while for owners of single family dwellings, it took more than 11 years rent to equal the value of their buildings.

I think best to err on the side of caution here, so the test I have developed focuses only on those properties where I have a range of civic numbers for the property and where the reported rent for that property equals the value of the building in 7 years or less. Requiring a range of civic numbers as a criteria eliminates from consideration the housing conditions below the stairs in the mansions, as well as in hotels like Rasco’s, or the Chinese hostels on Lagauchetière and the city’s still rare apartment buildings. It also recognizes that properties like those of Blanchet or Mill were not densely occupied in the sense meant here. Requiring higher than normal rents simply recognizes that these owners would have factored in the increased wear and tear on their buildings resulting from overcrowding.

What is left after applying these two restrictions is a group of properties that if they are linked to more household census returns in the complete manuscript census than the roll suggested they should be, then they can be reasonably considered as probable cases of overcrowding (Figure 19). By testing this group against MAP’s complete index of all households in the manuscript census, I am taking the issue of overcrowding well beyond the question of the immigrant-headed households that has been the focus to date. I can begin to ask how these immigrant households’ experiences relate to those of the larger host communities.

Figure 19. Probable cases of overcrowding where the address was part of a range and the rent equaled the building value within 7 years.

Applying these two criteria to properties where immigrant-headed households resided reduces considerably the number of properties being examined. Slightly more than a quarter of landladies’ properties (209 of 788), but almost a third of landlords’ properties (674 of 2,182) had both a range of addresses and generated a high enough rental income that it equaled the total assessed value of the buildings on the property in 7 years or less. This relative under-representation of landladies was not due to any marked gender differences in either the average or the median rents charged, which suggests it reflects different choices.

Distinct Practices for Differentiated Communities

Eighty-six landladies owned 88 properties where there appears to have been overcrowding. When linked to the census returns of all households in the city, it appears that there were 191 more households on these properties than suggested by the addresses in the roll, for an average of 2.17 households too many. In half of the cases, there was 1 more than expected, but on 24 properties there were 3 or more and 111 of the households lived there. This contrasts with 229 landlords having 666 more households on 268 properties, or on average of 2.49 households too many. Over a third of the properties had only one more than expected, but an almost equal number had three or more and on these 93 properties lived 410 of the probable cases.

What are we to make of this plethora of figures? Two general observations: landlords owned disproportionately more overcrowded properties and the overcrowding was more severe, than with was the case for landladies. The number of proprietors also matters. Whereas only 2 landladies owned more than one such property, 17 landlords owned 2 or more. Nine of these landlords owned two probable cases of overcrowding, while two owned three, four owned four, one owned five, and James Prendergast owned six. Clearly, for some landlords in turn of the century, Montréal the ethics of proprietorship differed from those practiced by almost all landladies.

Nor should this surprise us. After all, for the better part of a century, bourgeois women had been taught that their place was in the home. In the contemporary struggles for both married women’s property rights and for the suffrage, feminists in Canada articulated the reasons why they merited respect in maternalist terms. Given this history and the limited freedoms the law and paternalist cultures permitted them to exercise, it would be surprising if these bourgeois women handled their portfolios in a manner that challenged their role as guardians of the home. If their home mattered so much, why wouldn’t those of their tenants? This is not an essentialist argument. I am not suggesting landladies were more nurturing than landlords. What I am saying is that agency is exercised within social, cultural, and gendered constraints and in the differing discernable patterns their choices have left us, we can see the significance of gendered expectations.

Beyond the gendered distribution of ownership, this mapping of probable instances of overcrowding demonstrates several important points. First of all, there really are not all that many. We are dealing with a minority of proprietors. Too few to matter, some might argue. In light of the historiography on overcrowding, however, I think these relatively few cases are significant as they no doubt were to the 2,048 households living on these properties. I started with 4,300 rental units, where some of the most vulnerable households in the city resided and now, admittedly using very conservative methods to make the estimate, it appears that 1 in 12 may be a case of overcrowding. I think this result broadly supports the point that Gilles Lauzon has been making lo these many years.

Second, the relative absence of the main concentrations of immigrant housing is striking. The Pointe almost disappears. In Ste-Anne, while numerous properties qualified, only a limited number actually appear by this test to be cases of overcrowding. In St-Louis, home to the bulk of the Jewish households and many of the Italians, there are a number of cases of overcrowding particularly in the heart of what we saw to have been the new Jewish quarter. But, these particular concentrations indicate an important historical, and I think gendered, issue: these probable cases appear because of what I have done.

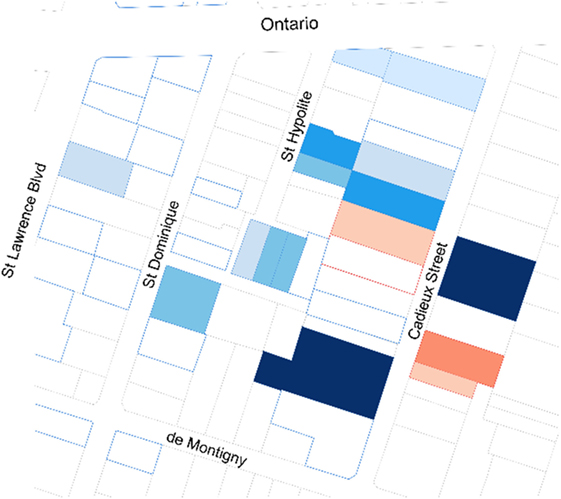

By linking the immigrant-headed houses through the map to the broader population and then using the returns about the host society to inform the housing situation of these immigrants, I have reconstituted something like the process these immigrant heads faced. They lived there because these properties were already, through the dynamics of the host society, characterized as poor housing. The notable concentration on Cadieux Street, home to so many of the Ashkenazi Jews, is a case in point (Figure 20). Here, on the 17 properties identified as overcrowded, only a minority of the households were headed by an immigrant: 46 of the 91 tenants of landlords and 10 of the 26 tenants of landladies.

Overall, 70% of the households living in overcrowded properties were born in Canada. This is why, relative to the other maps, St-Joseph (below the escarpment and above the Pointe), St-Denis (at the top of the map), and the eastern wards of Ste-Marie, St-Jean Baptiste, Lafontaine, and Papineau all appear more prominently in this analysis of overcrowding than on any of my earlier maps, which showed immigrant-headed households in primarily English-speaking wards.

If this analysis is correct, then the gendered nature of the ownership of these overcrowded properties discussed above refers not to a situation primarily facing immigrant-headed households, but to all those households in the city who were facing dire straits. One does not have to endorse the misèrabiliste viewpoint to recognize that this would have included a very significant number of people. I would estimate a fifth of the city’s 51,300 households. Thus, it may well be that in a city where one in four rental units was owned by a woman, the discernably different practices identified here, for lots where immigrant-headed households resided, resonated much more widely within the lived experience of the city’s broader working class.

If the gender of proprietors mattered to those at the lower end of the socioeconomic scale, can the same be said for those immigrant-headed households who were doing relatively well? After all, as we have seen, none of these groups appeared in my earlier analysis to be an undifferentiated mass. There were considerable differences in both opportunity and income within each group. For those who were better-off did the gender of proprietorship matter?

The answer is a quite resounding yes. In all three communities for which meaningful results might be expected, the nearest neighbor index shows that the further away you lived from the core concentrations for your specific immigrant community, the more likely you had a landlady rather than a landlord.27 Does this mean that when immigrants from qualitatively different cultural backgrounds lived outside the main concentrations associated with their community they chose a landlady over a landlord? Not necessarily, for I suspect it was very often the other way around. Landladies chose to lease to these unusual immigrant-headed households, while the landlords in their neighborhoods would not.

Be that as it may, these immigrant-headed households were usually the only foreign-born household head on the property. Thus, whatever the motivations of the people involved, or the varying combinations of choices that resulted in these households being located where there were, we should have no doubt about the effect. This greater ethnic and cultural dispersion would necessarily have reduced the extraordinary levels of ethnic, religious, and cultural segregation in the city: lines of segregation that had emerged in mid- to late-nineteenth century Montréal in support of the new patriarchal order of industrial capitalism.28

A Final Word of Caution

The three sources used here provide a wealth of detailed information about turn of the century Montréal. Once transformed into databases and GIS maps, the analytical possibilities appear if not endless, certainly very rich indeed. And this is as it should be, for the whole idea behind developing the MAP research infrastructure is to allow people access to a robust, yet complex series of spatially and temporally linked datasets, so that they may more successfully investigate historical change.

The power of such a system is not merely analytical. It is also, indeed at times I think primarily, seductive. So much information is now at our disposal, we think we should be able to answer the questions we pose. Not any question to be sure, but the important ones about causality. Clear answers to why questions.

The questions of our time are, however, only rarely the questions of times past and even when they were their meaning would in almost all cases have been qualitatively different. And so it is with the question at the heart of this study.

What the men and women on the 1903 roll would have thought of my analysis we can never know, but beyond being perplexed and perhaps intrigued by the technology, they would undoubtedly have wondered why something so normal in their lives could have become a question for historical investigation only a little more than a century later.

Why, when we now know so much more about the past experience of women than ever before, should the fact that women owned a quarter of all rental units in a large city a century ago need investigating? How could we have forgotten this? What mechanisms resulted in the memory of these practices by men and women becoming so lost to us as to lead us to question if they had any real meaning?

Since Amy Louise Erickson wrote her pioneering study on gender and property in early modern England (Erickson, 1993), we have had numerous studies showing the importance of female proprietorship in a wide variety of cultures and places (Schmidt, 2007; Wnek, 2009; Kaplan, 2010).29 Despite these rich new perspectives, all too many scholars continue to assume that it is reasonable to discuss gender and wealth in terms of entrepreneurial versus risk-adverse strategies.30 One of the reasons for such present-minded, and in this case frankly sexist, impositions of our own concerns on the past is an all too frequent and uncritical recourse to social science history. Using present day methods and analytical techniques first developed by the social sciences to study the past may at times be appropriate. Certainly, this paper has made use of such methods, but we must always be critically self-reflective when we do so. In part, this means ensuring that our categories and tests are developed in a manner that respects the historical logic of our diverse sources for they come from a qualitatively different time and place. But that is not enough.

What I have found most useful in stopping myself from making egregious errors of present-mindedness is to distinguish clearly between description and explanation. And so, I return to the conundrum I raised at the outset. The motivations of landlords, landladies, and tenants of turn of the century Montréal cannot be determined using MAP’s infrastructure. Epiphenomenal evidence does not allow of phenomenal explanation. No amount of statistical wizardry should hide this simple fact. When we advance an historical explanation based on this type of descriptive material, we need to be clear that is what we are doing. We are not presenting a proof based on evidence from the past; we are advancing a possible explanation based on our best efforts in the present to understand a past society. Furthermore, until we better understand how forgetting and remembering interact with structures of power in our own very unequal world, to talk of proof for any of the really large historical questions is, I fear, simply a form of professionally sanctioned, peer-reviewed, collective self-delusion.

Author Contributions

The author confirms he is the sole author of this work and has approved it for publication, while gratefully acknowledging the collegial contributions noted in the footnotes 1 and 18, and in the Acknowledgements section.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Throughout the research and writing of this piece, I benefitted from the sage advice of Elizabeth-Anne Malischewski. An early draft was substantively improved by the critical comments of Valerie Burton and the suggestions of Tony Chadwick. I would also like to thank the participants in our session on migration at the Economic History Society’s 90th conference, Robinson College, Cambridge, April 2016, for their comments. My concluding remarks owe much to a thought-provoking paper by the leading scholar of gender and property, and our host at Robinson College, Amy Louise Erickson. I would also like to thank Ian Milligan and Daniel Alves, reviewers for Frontiers in Digital Humanities, whose comments allowed me to further strengthen the piece.

Footnotes

- ^Here, I am paraphrasing Richard Denis’ formulation of the question when I first presented my early research to a London conference back in 2006. That paper was subsequently published as Sweeny (2007a). Two California studies relevant to this conversation are Simpson (1997) and Lain (2007).

- ^Nor is this solely an historic problem, see Kaul (2009).

- ^The project’s website provides an introduction to this pioneering Canadian H-GIS.

- ^It is perhaps necessary to point out that my usage of landlady in this article refers to women who were proprietors of real estate and who fully let the premises to tenants. They were not coresident with lodgers or managers of boarding houses. For a discussion of these quite different, but also highly gendered contexts, see the special issue on lodgers in rural and urban Europe in the past edited by Moring (2016).

- ^Most notably by the Canadian Families Project, for a methodological overview, see Sager (1998), while for the major findings, see Baskerville and Sager (2006).

- ^All but one of the contributing samples were initially designed to answer specific research questions and so this is not a random sample. For present purposes, the most important difference is that some samples took individual households, but others took all the households on a property, or all on a particular page. Thus, the relationship between households within the larger sample varies a great deal, which is why to examine one such relationship, overcrowding, I used the full index of all households in the census.

- ^Montreal City Council, “Introduction,” Valuation and assessment role of the immoveables of the city of Montreal. 1903.

- ^In addition to the SSHA 2014 paper in Toronto, results have been presented in Sweeny (2012, 2014a, 2015a).

- ^Please note this discrepancy in coverage, 98 versus 87%, means that for certain tests I am not able to include all of these households.

- ^The late nineteenth century saw the development of an important and long-lasting Canadian constitutional myth, which held that the negotiations which had given rise to Confederation in 1867 had been a pact between the “two founding peoples”: the French and the British. Initially, a French-Canadian idea, associated with the nationalist discourse of Honoré Mercier in the wake of the suppression of the Second Métis uprising and execution of Louis Riel in 1885, this became a widely accepted concept among federal Liberals until the late 1960s. By this interpretation, indigenous peoples, as well as immigrant groups conceived as ethnic minorities, had no real role in the making of Canada.

- ^The presence of Newfoundland might surprise some, but it was a separate British settler colony until 1949. Immigration to Quebec from Newfoundland dates from the 1840s and early 1850s when a significant number of families began moving to the North Shore of the St Lawrence and to the Gaspé Peninsula, as the French Shore agreement blocked settlement of the west coast of the island until 1904.

- ^The 36 Syrian households included 24 wives, 34 lodgers, 15 cousins, and 14 brothers, while the Chinese included only 4 women, but 430 lodgers, 40 servants, 11 cousins, and 5 brothers.

- ^So, English, French, Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Belgian, Chinese, Prussian, etc., were entered as “races.” French-speaking Canadians were listed as being of the French “race,” unless they were immigrants from the United States, in which case their “race” was generally listed as French-Canadian.

- ^Particularly, when one compares the lowest reporting groups’ answers with the answers given to a subsequent question: did you work in a factory or at home? Almost three times the number of Newfoundlanders said they worked in a factory than were identified as being an employee. None of the Chinese said they worked in a factory and only four said they worked at home. Yet, overwhelmingly, these Chinese worked in laundries located in their homes or in the several factory-sized steam laundries in the city.

- ^As Olson and Thornton (2011) have so elegantly demonstrated, inter-generational social mobility was particularly important for Irish Roman Catholics in nineteenth century Montréal.

- ^For a comparative analysis of family incomes in 1901 across six Canadian cities, see Baskerville and Sager (1998).

- ^My recent monograph demonstrated the importance of multi-class structures to the new industrial neighbourhoods we have long mistakenly considered working class.

- ^I used the open-source software QGIS for this project and I would like to acknowledge the collegial support I received to my queries from more experienced users within this community: Raphael Fernandez, Brent Wood, Alex M. of wildintellect.com and Uwe Fisher.

- ^In Montréal, the cardinal points do not define direction, rather east and west are defined in relation to the St Lawrence River conceived as flowing in an easterly direction, although here it flows north by north-east. When I refer to north, west, or east in the text it means at the top, to the left, and to the right of the maps are displayed here. They have all been rotated 75° clockwise.

- ^Where Presbyterian missionaries from Canada had been active for decades. Indeed, our sample includes Grace Eaton, a 53-year-old artist born in China to pioneering missionaries. A clear majority, 86 of the 164 heads, in the 1901 census for Montréal listed their religion as Presbyterian. For a recent review of the literature and a fine case study, see Connors (2014).

- ^Here, I am summarizing key findings of my paper “Social and Spatial Dynamics of Rentier Capital.”

- ^Including the household of Wah Hong Wing, laundryman, who told the enumerator that his religion was “Judaisme.”

- ^These include the four distinct immigrant-headed households who serve Jane Cassils (utilities), the three who continue to work in the homes of the late Andrew Allan (shipping) and John Redpath (sugar), as well as the two in each of the homes of Richard Angus (CPR) and Louisa Frothingham (heir to a metallurgy fortune and widow of a Molson).

- ^Doucet and Weaver’s (1991) earlier articles eventually formed the basis for their Housing the North American City.

- ^Her 1993 study, which won both the Innis and Macdonald prizes, has since been re-issued twice without any adequate discussion of the methodological problem Lauzon discovered. Gilles Lauzon’s thesis won the prize in labor history in Quebec and was published as: Lauzon (1989). His summary and restatement won the Frégault for the best article of the year: Lauzon (1992).

- ^For a more ample discussion of this important study, see my review (Sweeny, 2015c) of Lauzon (2014).

- ^Syrians lived too close together for this to be a meaningful question. Nearest neighbour index for the Jewish households with landladies was 0.623 with a Z-score of −8.595 versus 0.435 and −20.586 for landlords; for the Italians households it was 0.700 with a Z-score of −4.408 versus 0.418 and −13.871 for landlords; while the Chinese posted a 0.899 with a Z-score of −1.203 for landladies versus 0.685 and −6.596 for landlords.

- ^See the last substantive chapter in Sweeny (2015b), which surveys the industrial city in 1880.

- ^For an update on her classic work, see Erickson (2007). For an examination of the highly influential practice in London, see Doolittle (2015). It is now clear, however, that the active ownership role played by women in early modern England was in evidence in a number of differing societies: Hardwick (1998), Sjögren and Peter (2004), and Hutton (2005). To guard against Eurocentric understandings of gender and property, see Varley (2010) and Aluko (2015). For an early study on Syria, see Doumani (1998). For differing views on the situation elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire, see Kark and Fischel (2012) and Huffaker (2012).

- ^This gendered dichotomy is simply assumed to be natural by many of the authors in Green et al. (2011). Indeed, it is considered to remain valid even when all of the evidence presented calls that assumption into question.

References

Aluko, Yetunde A. (2015). Patriarchy and property rights among Yoruba women in Nigeria. Feminist Economics 21: 56–82. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2015.1015591

Baskerville, Peter. (1999). Women and investment in late-nineteenth-century urban Canada: Victoria and Hamilton, 1880–1901. Canadian Historical Review 80: 191–219. doi:10.3138/CHR.80.2.191

Baskerville, Peter. (2008). A Silent Revolution? Gender and Wealth in English Canada, 1860–1930. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Baskerville, Peter, and Sager, Eric W. (1998). Unwilling Idlers: The Urban Unemployed and Their Families in Late Victorian Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Baskerville, Peter, and Sager, Eric W. eds. (2006). Household Counts: Canadian Households and Families in 1901. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Boldizzoni, Francesco. (2011). The Poverty of Clio: Resurrecting Economic History. Rutherford: Princeton University Press.

Bradbury, Bettina. (1984). Pigs, cows and boarders. Non-wage forms of survival among Montreal families, 1861–1881. Labour/Le Travail 14: 9–46.

Bradbury, Bettina. (1993). Working Families: Age, Gender and Daily Survival in Industrializing Montreal. Toronto: Canadian Social History Series, McClelland and Stewart.

Bradbury, Bettina. (2011). Wife to Widow: Lives, Laws and Politics in Nineteenth Century Montreal. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Connors, Margaret. (2014). An Historical Register: Chinese People in Pre-Confederation Newfoundland. Major Research Paper for a M.A. in History. St.John’s: Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Copp, Terry. (1974). The Anatomy of Poverty: The Condition of the Working Class in Montreal, 1897–1929. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

Curtis, Bruce. (2002). The Politics of Population: State Formation, Statistics and the Census of Canada, 1840–1875. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Doolittle, Ian. (2015). Property law and practice in seventeenth-century London. Urban History 42: 204–24. doi:10.1017/S0963926814000546

Doucet, Michael, and Weaver, John. (1991). Housing the North American City. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Doumani, Beshara. (1998). Endowing family: waqf, property devolution, and gender in greater Syria, 1800 to 1860. Comparative Studies in Society and History 40: 3–42. doi:10.1017/S001041759898001X

Erickson, Amy Louise. (2007). Possession- and the other one-tenth of the law: assessing women’s ownership and economic roles in early modern England. Women’s History Review 16: 369–85. doi:10.1080/09612020601022261

Gilliland, Jason A., Olson, Sherry, and Gauvreau, Danielle. (2011). Did segregation increase as the city expanded? The case of Montreal, 1881–1901. Social Science History 35: 465–501. doi:10.1017/S0145553200011640

Green, David R., Owens, Alistair, Maltby, Josephine, and Rutterford, Janette eds. (2011). Men, Women and Money: Perspectives on Gender, Wealth, and Investment 1850–1930. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hardwick, Julie. (1998). Seeking separations: gender, marriages, and household economies in early modern France. French Historical Studies 21: 157–81. doi:10.2307/286931

Harvey, Kathryn. (1991). To Love, Honour and Obey: Wife-Battering in Working-Class Montreal, 1869–1879. Mémoire de maîtrise en histoire, Université de Montréal.

Huffaker, Shauna. (2012). Gendered limitations on women property owners: three women of early modern Cairo. Hawwa 10: 127–51.

Hutton, Shennan. (2005). On herself and all her property’ women’s economic activities in late-medieval Ghent. Continuity and Change 20: 325–50. doi:10.1017/S0268416005005552

Inwood, Kris, and Van Sligtenhorst, Sarah. (2004). The social consequences of legal reform: women and property in a Canadian community. Continuity and Change 19: 165–97. doi:10.1017/S0268416004004862

Kaplan, Debra. (2010). Women and worth: female access to property in early modern urban Jewish communities. Leo Baeck Institute Year Book. 55: 93–113. doi:10.1093/lbyb/ybq017

Kark, Ruth, and Fischel, Roy. (2012). Palestinian women in the public domain during the late ottoman and mandate periods, 1831–1948. Hawwa 10: 77–96. doi:10.1163/156920812X627759

Karpat, Kemal H. (1983). The «Syrian» emigration from the Ottoman state, 1880–1914. Revue d’histoire magrebine 10: 285–300.

Kaul, Nitasha. (2009). Elderly single women and urban property: when a room of one’s own becomes a curse. Gender and Development 17: 493–502. doi:10.1080/13552070903299186

Lain, Katy. (2007). Lillian Burkhart goldsmith: shaping the city. Southern California Quarterly 89: 285–306. doi:10.2307/41172376

Lauzon, Gilles. (1989). Habitat ouvrier et révolution industrielle: le cas du village St-Augustin. Montréal: Regroupement des chercheurs-chercheures en histoire des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec, coll. “Études et documents,” no 2.

Lauzon, Gilles. (1992). «Cohabitation et déménagements en milieu ouvrier montréalais: essai de réinterprétation à partir du cas du village Saint-Augustin (1871–1881)». Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 46: 115–42. doi:10.7202/305050ar

Lauzon, Gilles. (2014). Pointe-Saint-Charles: L’urbanisation d’un quartier ouvrier de Montréal, 1840–1930. Montréal: Septentrion.

Lewis, Robert. (1991). The segregated city. Journal of Urban History 17: 123–53. doi:10.1177/009614429101700201

Morris, R.J. (2005). Men, Women and Property in England, 1780–1870: A Social and Economic History of Family Strategies amongst the Leeds Middle Class. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olson, Sherry, and Thornton, Patricia. (2011). Peopling the North American City, Montreal 1840–1900. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Sager, Eric W. (1998). The National Sample of the 1901 Census of Canada: A New Source for the History of the Working Class. Amsterdam: Social Science History Conference.

Schmidt, Schmidt. (2007). Survival strategies of widows and their families in early modern Holland, c. 1580–1750. The History of the Family 12: 268–82. doi:10.1016/j.hisfam.2007.12.003

Simpson, Lee M.A. (1997). Women, real estate and urban growth: a case study of two generations of women property owners in Redlands, California, 1880–1940. California History 76: 24–47. doi:10.2307/25161642

Sjögren, Åsa Karlsson, and Peter, Linderström. (2004). Widows, ownership and political culture: Sweden 1650–1800. Scandinavian Journal of History 29: 241–62. doi:10.1080/03468750410003757