Abstract

Background:

Malaria remains a global health challenge, and the emergence of drug-resistant Plasmodium strains has necessitated the search for new antimalarial agents. Vernonia ambigua is used traditionally to treat malaria in parts of Africa, but its pharmacological potential remains underexplored. The aim of this study was to evaluate the antimalarial activity and chemical constituents of the chloroform leaf extract (CLE) of V. ambigua using in vivo and in silico approaches.

Methods:

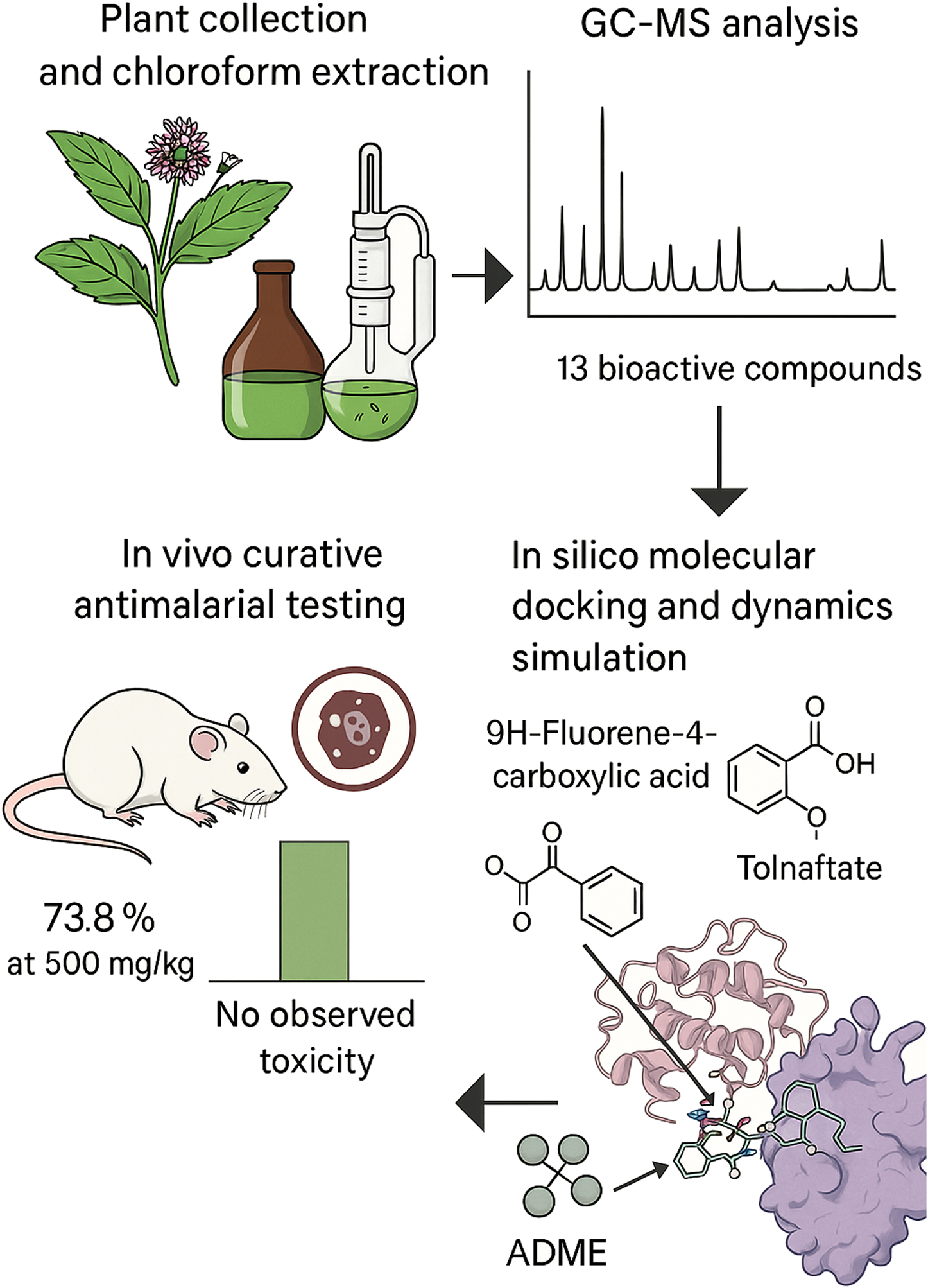

Acute toxicity was evaluated using Lorke’s method, and antimalarial activity was assessed via Ryley and Peter’s 4-day curative test in Plasmodium berghei–infected Swiss albino mice, followed by GC–MS profiling and in silico analyses (molecular docking and dynamics simulations) of the identified compounds.

Results:

The CLE showed a 73.8% parasite cure rate at 500 mg/kg, with no observed toxicity up to 5,000 mg/kg. GC-MS profiling revealed thirteen compounds, of which 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid and Tolnaftate showed strong PfLDH binding (docking scores of −7.7 and −7.6 kcal/mol, respectively). Tolnaftate demonstrated potentially modest stability in the active site of PfLDH during MD simulation. ADME/toxicity profiling identified 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid as the most promising compound, combining favorable bioavailability, low predicted toxicity, and good synthetic accessibility.

Conclusion:

V. ambigua possesses potent antimalarial properties, with 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid and Tolnaftate emerging as promising PfLDH inhibitors. These findings support further investigation and development of its bioactive constituents as antimalarial drug leads.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Malaria remains one of the most devastating infectious diseases worldwide, causing significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where Plasmodium falciparum is the predominant and most lethal species. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported approximately 247 million malaria cases globally, with 619,000 deaths, of which 77% occurred among children under 5 years old; According to the latest World Malaria Report (WHO, 2019; WHO, 2022; WHO, 2024), global malaria control efforts between 2000 and 2023 have averted an estimated 2.2 billion cases and 12.7 million deaths. Nevertheless, malaria remains a significant global health concern, with the greatest burden borne by the WHO African Region. In 2023, there were an estimated 263 million malaria cases and 597,000 deaths worldwide, an increase of approximately 11 million cases compared to 2022, while the number of deaths remained largely unchanged. Strikingly, about 95% of malaria deaths occurred in the WHO African Region, where many at-risk communities still face limited access to essential prevention, diagnosis, and treatment services. Despite the widespread use of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), the emergence and spread of drug-resistant P. falciparum strains pose a severe challenge to malaria control and elimination efforts (Thu et al., 2017; Wicht et al., 2020). This growing resistance supports the urgent need for novel antimalarial agents, particularly from natural sources, which have historically yielded critical therapeutic compounds (Singh et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2018; Belete, 2020).

Medicinal plants serve as a vital reservoir for drug discovery, playing a longstanding role in traditional medicine for treating febrile illnesses, including malaria (Kumar et al., 2018; Wangkheirakpam, 2018; Siqueira-Neto et al., 2023). Vernonia ambigua Kotschy and Peyr. (family Asteraceae) is one such plant, traditionally used in parts of Africa to manage malaria, gastrointestinal disturbances, and microbial infections (Gwandu et al., 2020). Preliminary studies on the decocted extract of the whole plant suggest potential antiplasmodial activity in V. ambigua (Builders et al., 2011). Thus, detailed investigations into its phytochemical composition and molecular mechanisms of antimalarial action remain limited.

A promising molecular target for antimalarial drug development is P. falciparum lactate dehydrogenase (PfLDH), an essential enzyme in the glycolytic pathway of the parasite and energy metabolism (Dunn et al., 1996; Kayamba et al., 2021). Given its structural and functional differences from its human counterpart, PfLDH is a selective target for therapeutic intervention (Kayamba et al., 2021). In silico molecular docking of plant-derived compounds against PfLDH provides a rapid, cost-effective approach for identifying potential inhibitors and prioritizing candidates for further biological evaluation (Shoemark et al., 2007; Aguiar et al., 2012; Samuel et al., 2021). The present study aimed to evaluate the antimalarial potential of the chloroform leaf extract (CLE) of V. ambigua through an integrated approach that combines chemical profiling using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), assessment of the interactions of identified phytoconstituents with PfLDH) via molecular docking simulations. We hypothesized that bioactive compounds in the CLE of V. ambigua inhibit PfLDH and contribute to the observed in vivo antimalarial activity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to integrate GC–MS profiling, curative in vivo antimalarial evaluation, and molecular docking/molecular dynamics (MD) simulations targeting PfLDH using compounds derived from V. ambigua. This integrated approach provides a mechanistic basis for the antimalarial activity of the plant and identified a potential novel PfLDH inhibitor, thereby offering new insights into plant-based drug discovery strategies against malaria.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Collection, identification, and preparation of plant sample

V. ambigua leaf was collected in June, 2024 during the rainy season at the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Sokoto State, Nigeria. A voucher specimen was prepared and authenticated by Musa Magaji at the Herbarium Unit of the Department of Pharmacognosy and Ethnopharmacy, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, where the voucher number of the plant PCG/UDUS/Aste/0008 was deposited. The leaves collected were freed from dirt and debris, shade-dried for 10 days, size-reduced using a grinder to a coarse powder, labeled and kept at room temperature before extraction.

2.2 Extraction protocol

The powdered sample of V. ambigua (362 g) was extracted via sequential extraction by maceration with solvent of increasing polarity starting with hexane (1.7 L), chloroform (1.8L), ethylacetate (1.7L) and methanol (1.8L), to obtained the different extracts coded as HLE, CLE, ELE and MLE, respectively. The procedure lasted for 8 days with the extract staying in contact with each solvent for 2 days with occasional shaking. The resulting extracts obtained were dried using a rotary evaporator at 40 °C to obtain the different extracts. The chloroform extract coded CLE was used for this study.

2.3 Experimental animals

A total of thirty-seven healthy Swiss albino mice (weighing 18–25 g) were used for this study. Twelve mice were allocated for acute toxicity assessment, while twenty-five were used for the in vivo antiplasmodial experiments. The animals were procured from the Animal House Facility of the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Nigeria. They were housed under standard laboratory conditions, including controlled temperature and humidity, with a 12-h light/dark cycle. The animals were fed a standard commercial diet (Ladokun Feeds, Ibadan, Nigeria) and had unrestricted access to clean water. Prior to the experimental procedures, all animals were acclimatized for a period of 2 weeks. All experimental protocols involving animals were conducted in accordance with internationally accepted guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Ethical approval was obtained from the University Health Research and Ethics Committee of Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, and registered under the reference number NHREC/UDU/-HREC/25/06/2023–UG70.

2.4 Acute toxicity test

The acute toxicity of CLE of V. ambigua was assessed using the method described by Lorke (1983) to estimate the median lethal dose (LD50). The study was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, nine mice were randomly divided into three groups of three animals each. The groups received intraperitoneal doses of the extract at 10, 100, and 1,000 mg/kg, respectively. Based on the outcome of the first phase, an additional three mice were assigned individually to three groups in the second phase and administered higher doses of 1,600, 2,900, and 5,000 mg/kg, respectively. All animals were observed continuously for the first 4 h post-administration and then periodically for 24 h to monitor signs of toxicity, behavioral changes, or mortality. The LD50 was calculated as the geometric mean of the highest non-lethal dose and the lowest lethal dose.

2.5 Antimalarial studies

2.5.1 Malaria parasite

The chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium berghei (NK-65 strain) was obtained from the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria. P. berghei shares conserved active site architecture and functional domains with P. falciparum, supporting the choice of the former for our in vivo studies (Winter et al., 2003). The parasite was subsequently maintained and expanded through serial passage in Swiss albino mice at the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Nigeria.

2.5.2 Ryley and Peter’s 4-day curative test

The antimalarial activity of CLE from V. ambigua was evaluated using the standard 4-day curative test described by Ryley and Peters (1970) and Peters et al. (1975). A chloroquine-sensitive strain of P. berghei berghei (NK-65) was used for infection. Donor mice with parasitaemia levels between 20% and 30% were used as the source of infected blood. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture, diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and adjusted to obtain a suspension containing approximately 1 × 107 parasitized erythrocytes per 0.2 mL. Each mouse was inoculated intraperitoneally with 0.2 mL of this standard inoculum on Day 0 (D0).

2.5.3 Grouping and treatment

Seventy-two hours post-inoculation (D3), the infected mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 5 per group) as follows:

Group I (Negative control): Received 0.2 mL of distilled water orally.

Group II (Positive control): Treated with 5 mg/kg/day of chloroquine diphosphate.

Groups III–V (Test groups): Treated orally with CLE at 150, 250, and 500 mg/kg, respectively.

The treatments were administered once daily from Day 3 to Day 6 (D3–D6).

2.5.4 Parasitaemia determination

On Day 6 (72 h after the first treatment), thick blood smears were prepared from the tail of each mouse. The smears were fixed with methanol, stained with 10% Giemsa solution, and examined under a light microscope (×1,000 magnification using oil immersion). Parasitaemia was determined by counting the number of parasitized red blood cells (pRBCs) per 200 leukocytes and calculated using the formula:

The percentage suppression of parasitaemia in the treated groups was calculated in comparison to the negative control group using the formula:where: A = Mean parasitaemia in the negative control group; B = Mean parasitaemia in the treated group.

2.5.5 Data analysis

The data were statistically evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test, which allowed for the comparison of each treatment group against the control. This analysis confirmed that the observed reductions in parasitemia were statistically significant (p < 0.05), thereby strengthening the validity of the in vivo antimalarial findings.

2.6 GC-MS analysis procedure

2.6.1 Protocol

The CLE from V. ambigua was first introduced into the GC system. This was done using an autosampler; an Agilent Intuvo 9000 GC system was used, coupled with a 5977B Mass Selective Detector (MSD). The sample was vaporized in the heated GC inlet and temperature was set at 300 °C (Agilent Technologies, n.d.). Helium, at a high purity of 99.999%, was used as the carrier gas and the flow rate was maintained at 1.2 mL/min. A DB-5 MS (5% phenyldimethylsiloxane) fused silica capillary column was utilized, with dimensions of 30 m in length, 320 µm internal diameter, and a film thickness of 0.25 µm. The sample components, or analytes, were separated based on their partitioning differences between the mobile phase (carrier gas) and the liquid stationary phase within the column (Agilent Technologies, n.d.). The oven temperature was programmed to enhance the separation process; Initially held at 50 °C for 2 min, and it was increased to 250 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min and held for 2 min, and finally increased to 300 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min and held for 3 min (Agilent Technologies, n.d.). After separation, the analytes were transferred through a heated transfer line into the mass spectrometer. This step ensures that the neutral molecules enter the MS for ionization without condensation.

In the MS, the neutral molecules were ionized, typically by Electron Ionization (EI) and in this analysis, an electron from a filament was accelerated with an energy of 70 electron volts (eV) and knocked an electron out of the molecule, forming a molecular ion (a radical cation). This process resulted in fragmentation, producing a variety of ions of different masses (Agilent Technologies, n.d.). The ions produced were separated based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) using the MS analyzer. For this analysis, the MS Source was maintained at 230 °C and the MS Quad at 150 °C (Agilent Technologies, n.d.). CLE or standard was injected into the GC system in splitless mode using the Agilent Automated Liquid Sampler (ALS) G4513A. The splitless mode ensured that the entire sample was directed onto the column, improving detection sensitivity for trace components (Agilent Technologies, n.d.).

2.6.2 Data acquisition and analysis

Data were acquired using GCMSD/Enhanced MassHunter Software and processed with GCMSD Data Analysis Software, incorporating the 2017 version of the NIST Library. This software aided in identifying compounds based on their mass spectra by matching the observed fragmentation patterns with those in the NIST database (Agilent Technologies, n.d.).

2.7 In silico studies procedure

2.7.1 Ligand selection and preparation

Thirteen (13) bioactive compounds identified from CLE of V. ambigua were subjected to molecular docking studies. The SDF files of these compounds were obtained from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.gov/), and the structures were prepared and converted into Protein Data Bank (PDB) format using PyRx software as previously reported by Johnson et al. (2023).

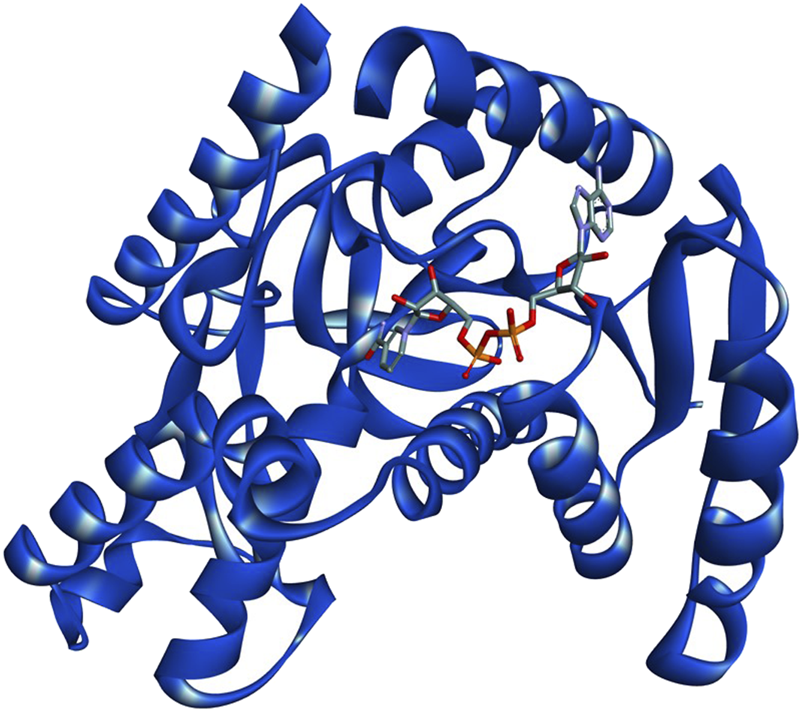

2.7.2 Protein preparation

The three-dimensional crystal structure of PfLDH with PDB ID: 1T2C (Figure 1) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). The structural and functional characteristics of PfLDH are reported to be conserved among Plasmodium species, hence its choice as a suitable target for molecular docking experiments that target this enzyme across the genus (Winter et al., 2003). Prior to docking, the protein was preprocessed using AutoDock 4.2, where Gasteiger charges were assigned and non-polar hydrogens were merged. Further refinement was performed using BIOVIA Discovery Studio, including the removal of water molecules and non-standard residues to ensure a clean and error-free structure. The protein was subsequently protonated and subjected to energy minimization to optimize its geometry and prepare it for interaction analysis (Johnson et al., 2023).

FIGURE 1

3D structure of PfLDH complexed with co-factor NADH (PDB ID:1T2C). The protein backbone is represented as a ribbon diagram, with NADH shown in stick representation.

2.7.3 Molecular docking analysis

Molecular docking was conducted to assess the binding affinities of thirteen bioactive compounds identified from CLE of V. with PfLDH. Docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina, integrated within PyRx virtual screening software (Trott and Olson, 2010). The prepared ligands and target protein (PfLDH) were imported into PyRx, and docking was performed following standard protocols. Binding energies (docking scores) were recorded to evaluate the strength of interaction between each compound and the target enzyme. Post-docking analysis was carried out to visualize and characterize the molecular interactions within the active site of PfLDH. Both 2D interaction diagrams and 3D binding conformations were generated using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2020 (Johnson et al., 2023).

2.7.4 Molecular docking (MD) simulation

Molecular dynamics simulations on the top-scoring compounds from CLE were carried out using NAMD software, and all the systems were prepared with the CHARMM-GUI web server (Jo et al., 2008) to obtain the input files for NAMD (Phillips et al., 2005). The input files were generated by using the CHARMM36 force field, and the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) server (Vanommeslaeghe et al., 2010) was used for the ligand’s parameterization. The systems were solvated with the TIP3 water model and neutralized by adding K+ and Cl− ions to the ionic concentration of 0.15 M using the distance ion-placing method. System energy minimization was carried out, followed by equilibration for 2 ns. Finally, all the systems were submitted to 100-ns production MD simulations in NVT ensemble.

2.7.5 In silico ADME, drug-likeness and toxicity predictions

The physicochemical properties and pharmacokinetic profiles (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion–ADME) of the identified compounds in CLE were evaluated using SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) as previously described by Bhat and Chatterjee (2021). The canonical SMILES of the top-scoring compounds were input into the SwissADME platform to predict parameters such as molecular weight, lipophilicity (LogP), topological polar surface area (TPSA), gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability.

To assess the toxicity profile, the compounds were further analyzed using the ProTox-3.0 web server (https://tox.charite.de/protox3/). Toxicity endpoints predicted included LD50 values, toxicity class, and potential for hepatotoxicity, carcinogenicity, immunotoxicity, mutagenicity, and cytotoxicity, thereby providing an early estimation of their safety for drug development.

3 Results

3.1 Percentage yield

The extraction of V. ambigua leaf using chloroform yielded a dark green extract weighing 8.31 g, corresponding to a percentage yield of 2.30% based on the initial weight of the plant material (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Plant | Solvent | Color | Weight (g) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. ambigua | Chloroform | Dark green | 8.31 | 2.30 |

Percentage yield of CLE from Vernonia ambigua.

3.2 Acute toxicity test

The median lethal dose (LD50) of CLE from V. ambigua was estimated to be ≥ 5,000 mg/kg, indicating that the extract is relatively non-toxic via the oral route (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Dose (mg/kg) | Number of mice used | Mortality |

|---|---|---|

| Phase I | Phase I | |

| 10 | 3 | 0/3 |

| 100 | 3 | 0/3 |

| 1,000 | 3 | 0/3 |

| Phase II | Phase II | |

| 1,600 | 1 | 0/1 |

| 2,900 | 1 | 0/1 |

| 5,000 | 1 | 0/1 |

Acute oral toxicity of CLE from Vernonia ambigua in mice.

3.3 Antiplasmodial studies

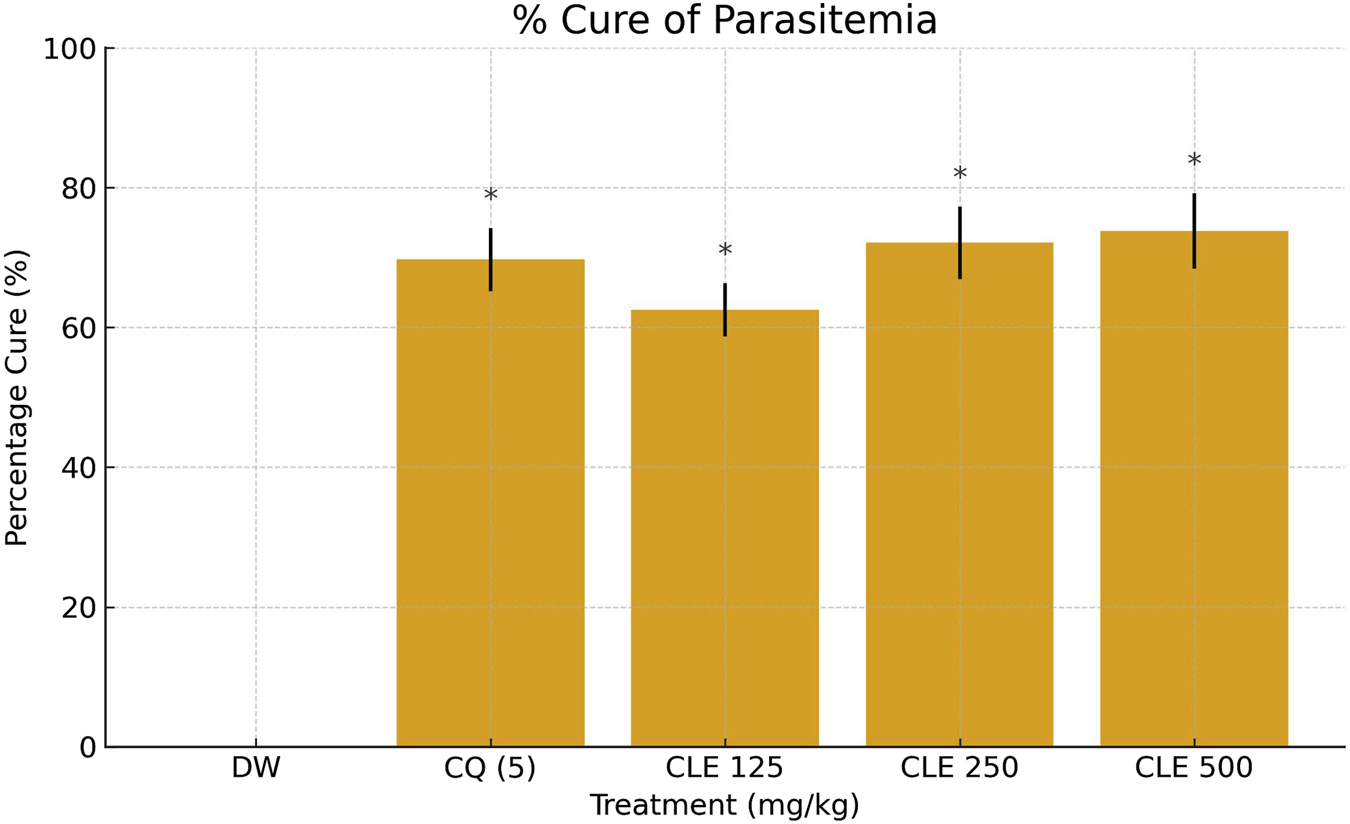

The curative antimalarial effect of CLE from V. ambigua is summarized in Table 3; the extract has demonstrated a significant (p < 0.05) curative antimalarial effect, which was in a dose-dependent manner (Table 3). CLE exhibited 62.5, 72.1% and 73.8% cure of parasitemia at 125, 250 and 500 mg/kg, respectively. The standard drug, chloroquine at 5 mg/kg was able to cure the parasitemia with 69.7%, (Figure 2).

TABLE 3

| Treatment (drug/extract) | Dose (mg/kg) | Average parasitemia | Percentage cure (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distilled water | 10 mL/kg | 31.33 ± 1.76** | _ |

| CLE | 500 | 8.20 ± 1.60* | 73.8 |

| CLE | 250 | 8.75 ± 1.66* | 72.1 |

| CLE | 125 | 11.75 ± 0.63* | 62.5 |

| Chloroquine | 5 | 9.50 ± 0.87* | 69.7 |

Curative antimalarial effect of CLE from Vernonia ambigua.

Key: CLE, chloroform leaf extract of Vernonia ambigua. *Values are statistically significantly (p < 0.05) different from the distilled water treated groups. **Values are statistically significantly (p > 0.05) different from the chloroquine treated groups.

FIGURE 2

Percentage cure of parasitemia in P. berghei–infected mice treated with CLE of Vernonia ambigua *(125–500 mg/kg), chloroquine (CQ, 5 mg/kg), and vehicle control (DW). Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05 vs. DW; **p < 0.05 vs. CQ.

3.4 Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) of CLE

GC-MS analysis of CLE from V. ambigua identified 13 bioactive compounds with varying retention times and relative abundance as indicated in Table 4 and Supplementary Figure S1. The identified compounds exhibited varying retention times and peak area percentages, indicating their relative abundance in the extract. Among them, 2-ethylacridine (RT: 19.948 min) had the highest peak area (2.41%), suggesting it is the most abundant compound detected. Other prominent constituents include (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid (1.45%) and hexahydropyridine, 1-methyl-4-[4,5-dihydroxyphenyl] (1.28%). Several bioactive structural classes were represented, including indoles, acridines, quinolines, and triazoles, which are known to possess diverse pharmacological properties. Notably, tolnaftate, a well-known antifungal agent, was also detected. The presence of these compounds suggests a rich phytochemical profile that could contribute to the observed antimalarial activity of the extract.

TABLE 4

| S/No | Retention time | Area % | Compound name | Quality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.113 | 0.75 | 2-Methyl-7-phenylindole | 37 |

| 2 | 3.440 | 1.16 | Hexahydropyridine, 1-methyl-4-[4,5-dihydroxyphenyl] | 53 |

| 3 | 5.471 | 0.90 | 1-Benzazirene-1-carboxylic acid, 2,2,5a-trimethyl-1a-[3-oxo-1-butenyl] perhydro-, methyl ester | 46 |

| 4 | 8.469 | 1.45 | (9-Oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid | 40 |

| 5 | 9.614 | 0.76 | Ethyl 2-amino-6-ethyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-1-benzothiophene-3-carboxylate | 40 |

| 6 | 10.398 | 0.74 | 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid | 43 |

| 7 | 10.449 | 0.63 | Diethyl 5-formyl-3-methyl-1H-pyrrole-2,4-dicarboxylate | 38 |

| 8 | 10.747 | 0.55 | 5-Methyl-2-phenyl-1H-indole | 32 |

| 9 | 11.124 | 0.87 | 4-Allyl-5-(3-furyl)-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thione | 47 |

| 10 | 11.279 | 0.58 | 7-Chloro-4-methoxy-3-methylquinoline | 47 |

| 11 | 12.332 | 0.54 | Tolnaftate | 45 |

| 12 | 16.400 | 0.88 | 3-Amino-6-methylthieno [2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxamide | 40 |

| 13 | 14.111 | 2.41 | 2-Ethylacridine | 59 |

GC-MS identified compounds from CLE of Vernonia ambigua.

3.5 In silico studies

3.5.1 Molecular docking

The molecular docking results presented in Table 5 showed that the bioactive compounds identified from the CLE of V. ambigua exhibited binding affinities against PfLDH with docking scores ranging from −7.7 to −5.4 kcal/mol, whereas the native ligand NADH demonstrated a stronger binding affinity with a docking score of −10.1 kcal/mol.

TABLE 5

| S/No | CID | Compounds | Docking scores (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 439153 | NADH (native ligand) | −10.1 |

| 2 | 81402 | 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid | −7.7 |

| 3 | 5510 | Tolnaftate | −7.6 |

| 4 | 610242 | (9-Oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid | −7.5 |

| 5 | 610181 | 2-Methyl-7-phenylindole | −7.3 |

| 6 | 610161 | 2-Ethylacridine | −7.2 |

| 7 | 83247 | 5-Methyl-2-phenyl-1H-indole | −7.1 |

| 8 | 610035 | Hexahydropyridine, 1-methyl-4-[4,5-dihydroxyphenyl] | −6.3 |

| 9 | 610241 | Ethyl 2-amino-6-ethyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-1-benzothiophene-3-carboxylate | −6.3 |

| 10 | 53375841 | 1-Benzazirene-1-carboxylic acid, 2,2,5a-trimethyl-1a-[3-oxo-1-butenyl] perhydro-, methyl ester | −6.0 |

| 11 | 765847 | 3-Amino-6-methylthieno [2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxamide | −5.9 |

| 12 | 223280 | Diethyl 5-formyl-3-methyl-1H-pyrrole-2,4-dicarboxylate | −5.8 |

| 13 | 610128 | 7-Chloro-4-methoxy-3-methylquinoline | −5.8 |

| 14 | 723710 | 4-Allyl-5-(3-furyl)-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thione | −5.4 |

Docking scores of the compounds from CLE against pfLDH.

3.5.2 Molecular interaction of the compounds from CLE with PfLDH

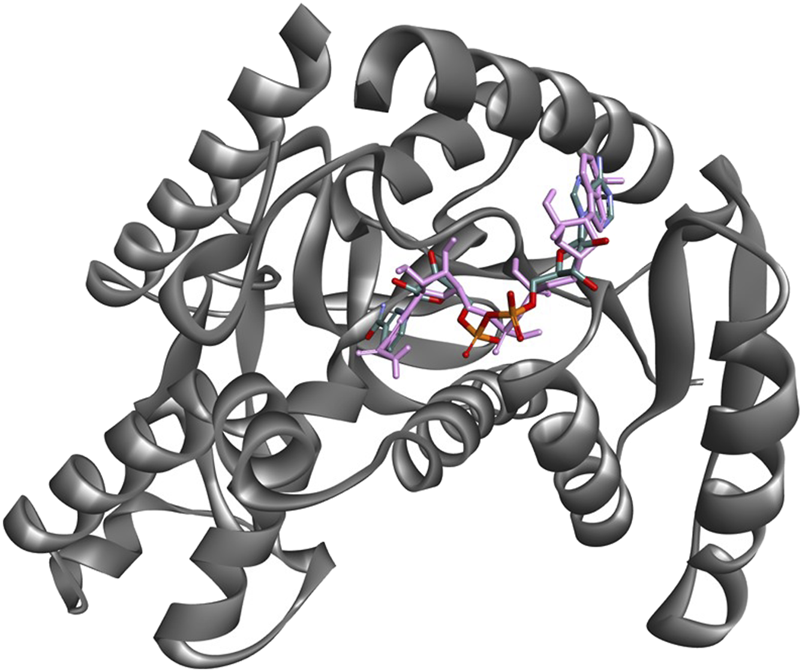

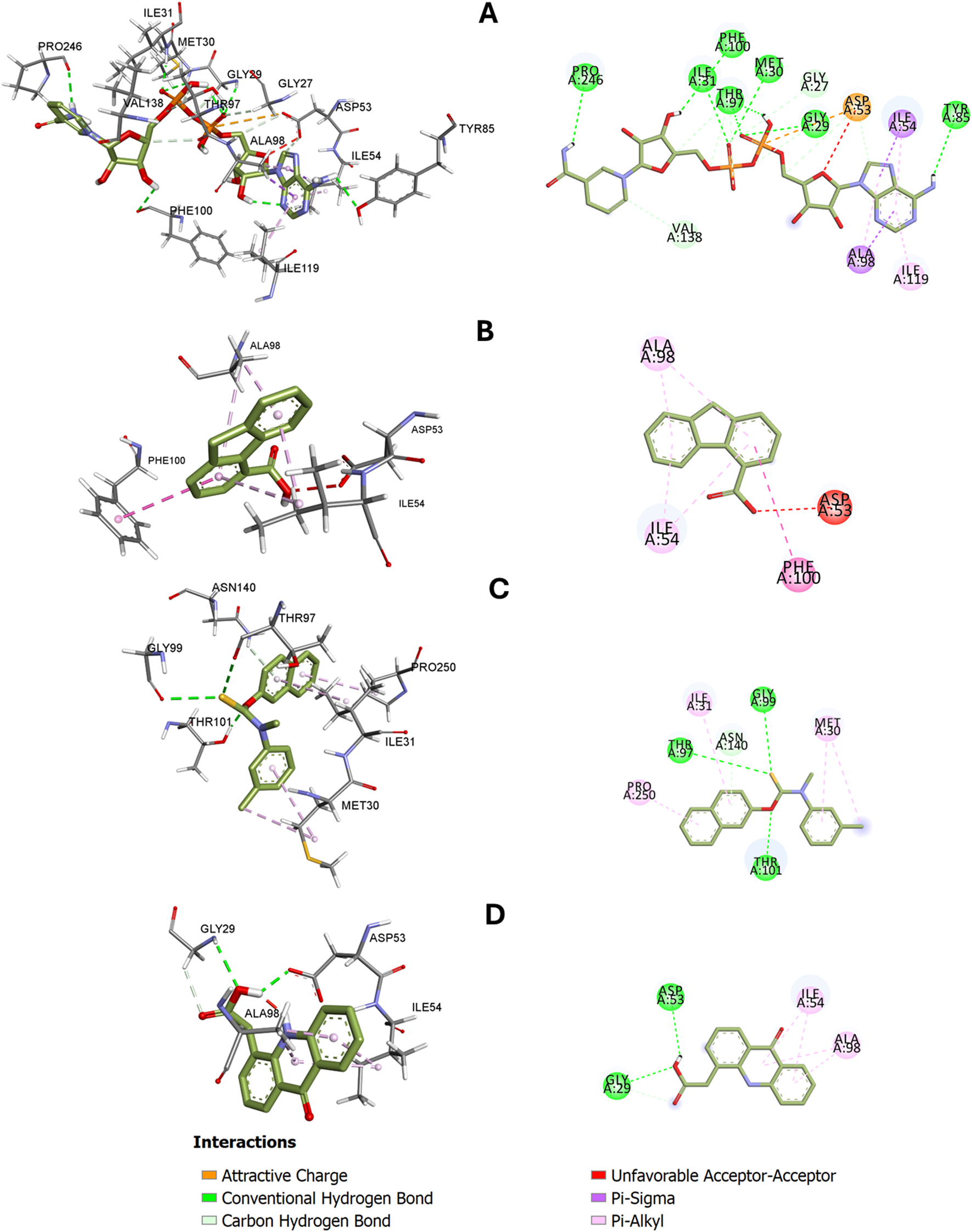

The co-crystallized ligand, NADH in PDB ID: 1T2C (cyan), and the docked pose of NADH superimposed PfLDH active site (Figure 3). This comparison evaluates how well the docking algorithm reproduces the experimentally observed binding mode of NADH. A close overlap implies high accuracy of the docking protocol and confidence in the pose prediction. The co-crystal and docked pose largely overlap, especially in the pharmacophoric groups. RMSD between the co-crystal and docked pose is found to be 0.45 Å. Generally, an RMSD < 2.0 Å indicates a good overlap, thus validating the docking approach. The molecular interactions between the top-scoring phytoconstituents of CLE from V. ambigua with pfLDH are presented in Figure 4.

FIGURE 3

Superimposition of the PfLDH crystal ligand NADH (cyan) with its docked pose (pink) within the active site of PfLDH, demonstrating good alignment and validating the docking protocol.

FIGURE 4

3D and 2D-dimensional representations of interactions between PfLDH and (A) NADH (cocrystal ligand), (B) 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid, (C) Tolnaftate, and (D) (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid. Hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interactions with specific amino acid residues are shown.

3.5.3 Molecular dynamics simulation

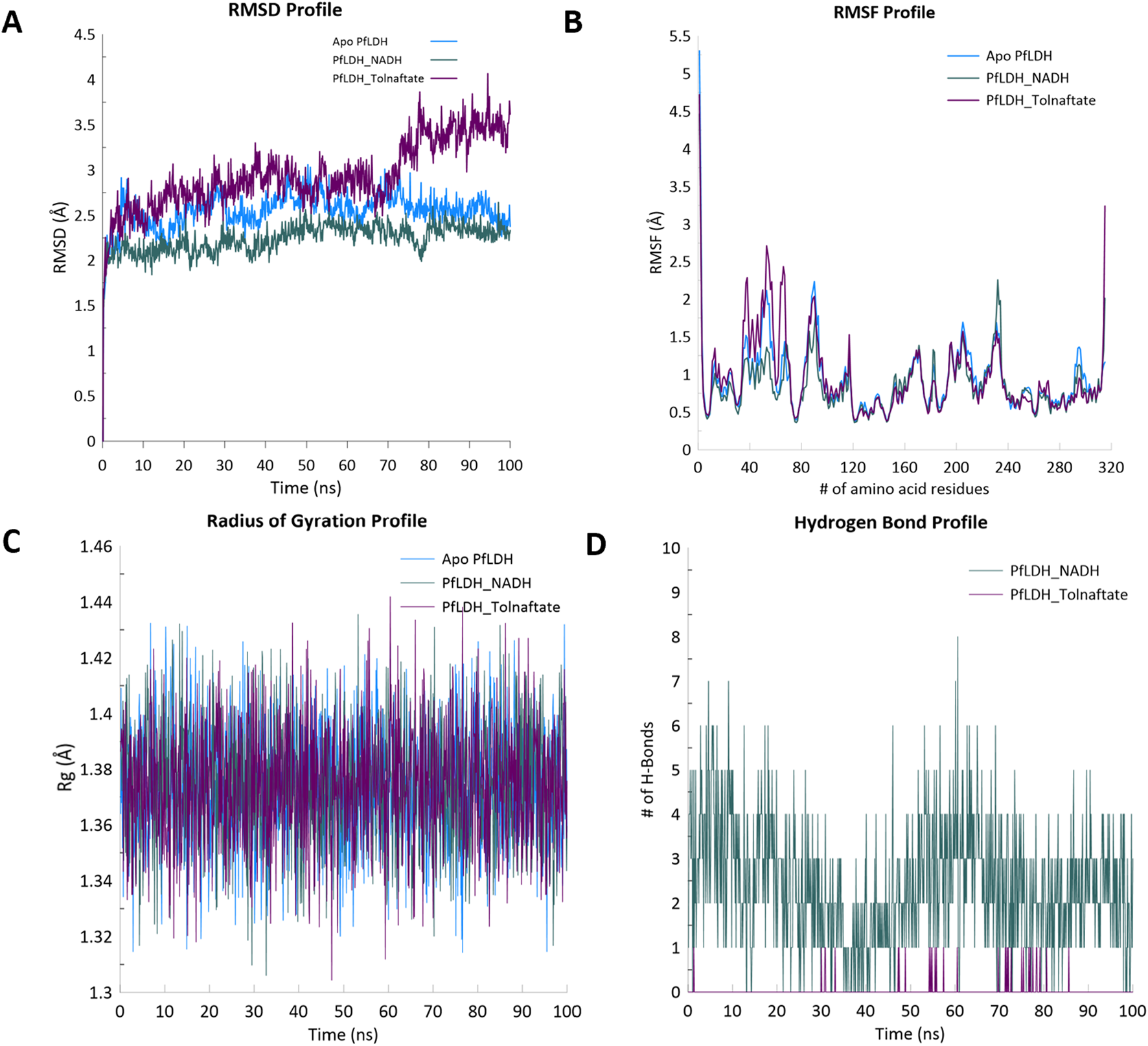

The RMSD profiles of the apo protein (1T2C), the protein bound to the standard ligand (NADH), and the protein bound to Tolnaftate over a 100 ns simulation period are indicated in Figure 5A; the apo protein exhibited a relatively stable RMSD, fluctuating around 2.5–2.7 Å after initial equilibration. The NADH-bound complex displayed the lowest and most consistent RMSD values, maintaining stability around 2.2 Å throughout the simulation. In contrast, the Tolnaftate-bound complex demonstrated a gradual increase in RMSD, reaching approximately 4.0 Å toward the end of the simulation, with more pronounced fluctuations observed after 60 ns. Figure 5B presents the RMSF values for the amino acid residues in the three systems. All systems showed relatively low fluctuations (<1.5 Å) across most residues, especially within the structured core of the protein. Elevated fluctuations were observed at the N- and C-terminal regions in all systems, with the Tolnaftate-bound complex showing slightly higher peak values (>3 Å) at these termini. Moderate fluctuations (∼1.5–2.5 Å) were also observed in loop regions around residues 30–80 and 200–240, with the Tolnaftate-bound system generally exhibiting higher values compared to the other two. The radius of gyration values shown in Figure 5C were consistent across all systems, fluctuating within a narrow range of approximately 1.32–1.42 Å throughout the 100 ns simulation. All three systems displayed small, high-frequency oscillations, indicating maintenance of compactness. Slightly broader oscillations were noted for the apo protein compared to the NADH- and Tolnaftate-bound complexes. Figure 5D illustrates the number of hydrogen bonds formed between the ligands and PfLDH during the simulation. The NADH-bound complex maintained a higher and more stable number of hydrogen bonds throughout the trajectory, typically ranging between 2 and 6, with occasional peaks up to 8. In comparison, the Tolnaftate-bound complex exhibited a lower number of hydrogen bonds, with more frequent interruptions and fluctuations in bonding events across the simulation timeline.

FIGURE 5

(A) Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), (B) root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), (C) radius of gyration (Rg), and (D) hydrogen bond profiles of PfLDH alone, PfLDH–NADH complex, and PfLDH–Tolnaftate complex during 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation.

3.5.4 In silico ADME and drug-likeness of the compounds from CLE

The ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion), pharmacokinetic properties, and drug-likeness of the five top-scoring compounds from CLE (9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid, Tolnaftate, 9-Oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid, 2-Methyl-7-phenylindole, and 2-Ethylacridine) are summarized in Table 6. The molecular weights of the compounds ranges from 207.27 to 307.41 g/mol and the Log S values, indicating solubility, ranges from −3.36 to −5.46. The Log P values, reflecting lipophilicity, ranges from 2.76 to 4.66 while the bioavailability scores for the compounds ranges from 0.55% to 0.85%. All the compounds have shown high GIT absorption and the ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The Log Kp values, reflecting skin permeation ranges from −4.30 to −5.40. Notably, 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid and 2-methyl-7-phenylindole were identified as substrates of the permeability glycoprotein (P-gp), while the other compounds were not. All compounds are partially inhibitors of CYP450 enzymes except 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid. With the exception of Tolnaftate, which has one violation, all compounds comply with Lipinski’s rule of five.

TABLE 6

| Molecules | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical properties | |||||

| Formula | C14H10O2 | C19H17NOS | C15H11NO3 | C15H13N | C15H13N |

| Molecular weight (g/mol) | 210.23 | 307.41 | 253.25 | 207.27 | 207.27 |

| H-bond acceptors | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| H-bond donors | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Molar refractivity | 61.85 | 96.92 | 73.62 | 68.70 | 69.02 |

| TPSA (Å2) | 37.30 | 44.56 | 70.16 | 15.79 | 12.89 |

| Lipophilicity | |||||

| Consensus LogP o/w | 2.76 | 4.66 | 2.24 | 3.75 | 3.72 |

| Water solubility Log S (ESOL) | |||||

| Water solubility Log S (ESOL) | −3.57 | −5.46 | −3.36 | −4.12 | −4.23 |

| Pharmacokinetics GI | |||||

| Absorption | High | High | High | High | High |

| BBB permeant | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| P-gp substrate | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No |

| Log KP (skin permeation cm/s) | −5.40 | −4.30 | −6.11 | −4.67 | −4.72 |

| Drug-likeness | |||||

| Lipinski violation | Yes; 0 violation | Yes; 1 violation | Yes; 0 violation | Yes; 0 violation | Yes; 0 violation |

| Ghose | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Veber violation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Egan | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Muegge | Yes | No; 1 violation | Yes | No; 1 violation | No; 1 violation |

| Bioavailability score | 0.85 | 0.55 | 0.85 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Medicinal chemistry | |||||

| Synthetic accessibility | 2.24 | 2.68 | 1.82 | 2.68 | 1.22 |

| Leadlikeness | No; 1 violation | No; 1 violation | Yes | No; 1 violation | No; 2 violations |

In silico ADME and Drug-likeness of the compounds.

M1=(9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid), M2= (Tolnaftate), M3= (9-Oxo-9, 10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid), M4= (2-Methyl-7-phenylindole), M5= (2-ethylacridine).

3.5.5 Toxicity profile of the top-five compounds from CLE

The findings from the toxicity prediction of the top five compounds are presented in Table 7; the LD50 of the compounds ranges from 670 to 6,500 mg/kg and they fell under the toxicity class of 4–6. None of the compounds have shown the tendency of being cardiotoxic, carcinogenic, immunotoxic or cytotoxic and they may not cause any nutritional toxicity. All of them can cross BBB barrier but all the compounds have shown tendency of being hepatotoxic except for 9-Oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid and 2-ethylacridine. Similarly only 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid and 9-Oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid are likely not to be mutagenic and neurotoxic; both compounds have shown the tendency of being nephrotoxic. Only 9-Oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid was active against respiratory toxicity all the compounds are not ecotoxic with the exception of 9-Oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid and in terms of chemical toxicity, only Tolnaftate and 9-Oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid were active.

TABLE 7

| Parameters | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted LD50 (mg/kg) | 6,500 | 6,000 | 1,200 | 670 | 940 |

| Predicted toxicity class | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Hepatotoxicity | Active (0.56) | Active (0.54) | Inactive | Active (0.50) | Inactive |

| Neurotoxicity | Inactive | Active (0.57) | Inactive | Active (0.52) | Active (0.54) |

| Nephrotoxicity | Active (0.55) | Inactive | Active (0.59) | Inactive | Inactive |

| Respiratory toxicity | Inactive | Inactive | Active (0.62) | Inactive | Inactive |

| Cardiotoxicity | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| Carcinogenicity | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| Immunotoxicity | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| Mutagenicity | Inactive | Active (0.69) | Inactive | Active (0.80) | Active (0.50) |

| Cytotoxicity | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| BBB-barrier | Active (0.87) | Active (0.86) | Active (0.57) | Active (0.94) | Active (0.96) |

| Ecotoxicity | Active (0.56) | Active (0.82) | Inactive | Active (0.78) | Active (0.84) |

| Clinical toxicity | Inactive | Active (0.51) | Active (0.61) | Inactive | Inactive |

| Nutritional toxicity | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

Toxicity profile of top-five scoring compounds in CLE.

Key: Values in parenthesis denotes percentage probability. M1= (9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid), M2= (Tolnaftate), M3= (9-Oxo-9, 10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid), M4= (2-Methyl-7-phenylindole), M5= (2-ethylacridine).

4 Discussion

Despite decades of progress in malaria control, the emergence of drug-resistant Plasmodium strains continues to threaten global health, reinforcing the urgent need for newer, safer, and more effective antimalarial agents (Varo et al., 2020; WHO, 2023). Accordingly, medicinal plants remain a valuable source of therapeutic leads, particularly those with established traditional use and favorable safety profiles (Jachak and Saklani, 2007; Builders, 2015; Kumar et al., 2022). The current study investigated CLE from V. ambigua, a plant traditionally used in malaria treatment (Builders et al., 2011), with initial toxicological evaluation serving as a key preclinical requirement. The acute oral toxicity results showed no mortality in mice at doses up to 5,000 mg/kg, indicating that the extract is practically non-toxic based on Lorke’s method (Lorke, 1983). This high safety margin supports the ethnopharmacological relevance of V. ambigua and suggests a low risk of acute adverse effects at therapeutic doses, thus providing a strong rationale for further pharmacological investigation as a source of antimalarial compounds.

Furthermore, the in vivo antiplasmodial efficacy of CLE using the standard curative (Rane’s) test against P. berghei showed dose-dependent parasite suppression. The highest activity was observed at 500 mg/kg (significant reduction in parasitaemia (8.20 ± 1.60) and a corresponding cure rate of 73.8%), which was comparable (p > 0.05) to that of chloroquine (69.7% cure at 5 mg/kg) The observed suppression suggests that the extract contains bioactive compounds capable of interfering with parasite survival and replication in vivo. Importantly, all tested doses of CLE significantly reduced parasitaemia compared to the negative control (distilled water, 31.33% ± 1.76%), further validating the traditional use of V. ambigua in malaria treatment. The antimalarial activity observed in this study is consistent with the findings of Builders et al. (2011), who reported significant parasite suppression with aqueous extracts of V. ambigua at doses up to 600 mg/kg in P. berghei-infected mice. Both studies also reported an LD50 above 5,000 mg/kg, indicating a wide safety margin; the estimated therapeutic index (TI) of CLE, calculated from the ratio of its LD50 (>5,000 mg/kg) to the effective curative dose (500 mg/kg), suggests a favorable safety margin for further preclinical development. These consistent findings across different extraction methods and study designs support the potential of V. ambigua as a source of antimalarial compounds.

The GC-MS profiling of CLE from V. ambigua revealed a chemically diverse array of thirteen phytoconstituents, including indoles, acridines, quinolines, pyridines, and benzothiophene derivatives (Supplementary Figure S2). Among these, 2-ethylacridine was the most abundant compound (2.41%), while tolnaftate was the least abundant (0.54%). Several of the identified compounds, such as 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid, (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid, and 5-methyl-2-phenyl-1H-indole, contain pharmacophores known to exhibit antiplasmodial properties (Frederich et al., 2008; Omar et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2024). The detection of multiple nitrogen-containing heterocycles and oxygenated aromatics in the extract suggests a potential for biological activity, particularly against metabolic targets such as PfLDH (Uzor, 2020). This chemical complexity supports the traditional use of V. ambigua in malaria treatment and justifies further exploration of its constituents for therapeutic development.

The molecular docking analysis provided insights into the potential inhibitory interaction of the GC-MS-identified compounds from CLE of V. ambigua with PfLDH, a critical enzyme in the parasite’s energy metabolism. Among the thirteen compounds docked, 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid, Tolnaftate, and (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid showed the strongest binding affinities, with docking scores of −7.7, −7.6, and −7.5 kcal/mol, respectively. These values, while lower than that of the native ligand NADH (−10.1 kcal/mol), indicate a favorable interaction with the PfLDH binding pocket. Notably, several other compounds, including 2-methyl-7-phenylindole and 2-ethylacridine, also demonstrated moderate binding energies in the range of −7.3 to −7.1 kcal/mol, suggesting they may contribute to the extract’s observed antimalarial activity. The docking scores provided a preliminary indication of binding strength and serve as a basis for selecting compounds for further dynamic and experimental validation.

The top docked compounds from CLE of V. ambigua showed distinct binding profiles within the active site of PfLDH), interacting with catalytically relevant residues and mimicking the behavior of the native cofactor, NADH (Figure 4A). 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid formed a relatively compact interaction network dominated by π–π stacking with Phe100, Ala98, and Ile54, and a conventional hydrogen bond with Asp53, a residue critical for NADH anchoring. This hydrogen bonding adds specificity and may enhance binding affinity, explaining the slightly stronger docking score than Tolnaftate (Figure 4B). However, its limited polar interactions and susceptibility to dissociation in MD suggest a less stable dynamic profile. Tolnaftate demonstrated a robust interaction network primarily involving hydrophobic interactions. Notably, π–alkyl interactions with Ile54, Ile119, and Ala98, as well as van der Waals contacts with Gly27, Val55, and Met58, anchored the ligand stably within the binding pocket. The presence of a carbon–hydrogen bond with Asp53 suggests additional polar stabilization, although it formed fewer hydrogen bonds compared to NADH (Figure 4C). This hydrophobic mode of binding may contribute to Tolnaftate’s favorable docking score and its maintained pose during molecular dynamics (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid interacted through key hydrophobic residues such as Ile54, Ala98, and Val55, with the latter forming a key hydrogen bond with Asp53. However, the steric arrangement and possible unfavorable donor–donor repulsions may explain the instability seen during MD runs for (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid (Figure 4D). In comparison, NADH, the native ligand, exhibited a well-distributed interaction network involving multiple hydrogen bonds with Ile31, Met30, Gly99, Phe100, Gly32, Gly29, Asp53, Asn140, Tyr85 and Thr97, as well as π–π interactions and van der Waals contacts. Its optimal alignment and tight anchoring explain its superior binding energy (−10.1 kcal/mol) and structural stabilization of the protein during simulation.

The top three docking-scored compounds, 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid, Tolnaftate, and (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid along with the native ligand NADH, were subjected to molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to evaluate their stability within the PfLDH active site. However, 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid and (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid were observed to dissociate from the PfLDH binding pocket during the simulation, even after multiple runs. As a result, only the NADH–PfLDH and Tolnaftate–PfLDH complexes were included in the final analysis. Both systems demonstrated a rapid increase in root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) during the initial ∼5 ns, which is typical of systems adjusting from their docked conformations to more stable states. The apo protein (PDB ID: 1T2C) reached an RMSD plateau around 2.5–2.7 Å, suggesting moderate deviation with acceptable structural stability post-equilibration. The NADH–PfLDH complex showed the lowest and most stable RMSD (2.2 Å) throughout the trajectory, indicating that the native ligand contributed to enhanced structural stability. Conversely, the Tolnaftate–PfLDH complex exhibited the highest RMSD (∼2.5–4.2 Å), with significant fluctuations after 60 ns, suggesting greater conformational flexibility or instability induced by the ligand (Figure 4A). This observation aligned with findings from previous studies that crystal complexes tend to exhibit higher structural stability than docking-generated complexes (Uba et al., 2020).

Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis across all three systems revealed values generally below 1.5 Å, particularly in the protein’s structured core, reflecting a stable secondary structure. Terminal regions (near residues 1 and 320) showed significantly higher fluctuations (>3 Å), especially in the apo and Tolnaftate-bound systems, which is consistent with expected terminal flexibility due to the absence of stabilizing interactions. The NADH-bound complex demonstrated reduced terminal fluctuations, further suggesting a stabilizing effect of the native ligand. Moderate fluctuations (∼1.5–2.5 Å) were observed in loop regions, notably between residues ∼30–80 and ∼200–240. Among the systems, the Tolnaftate-bound complex showed consistently higher peaks in these regions, indicating increased local flexibility possibly resulting from conformational adjustments upon Tolnaftate binding (Figure 4B).

The radius of gyration (Rg) analysis provided insights into the overall compactness and structural integrity of the simulated systems over 100 ns. All systems exhibited Rg values within a narrow range (∼1.32–1.42 Å), suggesting that the protein retained its global compactness without signs of unfolding or collapse. Minor, high-frequency fluctuations reflected normal protein breathing motions rather than instability. The apo protein displayed slightly broader oscillations, indicating a higher degree of flexibility. In contrast, the NADH-bound system maintained more consistent Rg values, implying ligand-induced stabilization. The Tolnaftate-bound system showed Rg values comparable to the others, though with marginally greater variability (Figure 4C), supporting earlier RMSD and RMSF findings (Uba et al., 2020). Hydrogen bonding analysis further confirmed the superior binding stability of NADH, which consistently formed between 2 and 6 hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation. Occasional peaks of 7–8 hydrogen bonds were recorded, indicating strong and persistent interactions. In contrast, Tolnaftate exhibited fewer and less stable hydrogen bonds, suggesting weaker binding affinity or alternative interaction modes with the target protein (Figure 4D).

The pharmacokinetic profiling and drug-likeness analysis of the top-performing compounds provided additional insight into their potential as orally bioavailable and CNS-active antimalarial agents. All the five compounds demonstrated high gastrointestinal (GI) absorption and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, suggesting favorable oral bioavailability and potential efficacy in cerebral malaria (Gondim et al., 2019; Das and Prabhu, 2022). Notably, 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid and (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid exhibited no Lipinski rule violations, acceptable molar refractivity, and moderate topological polar surface area (TPSA), indicating good membrane permeability and drug-likeness. Tolnaftate showed the highest lipophilicity (LogP = 4.66) and the lowest water solubility (Log S = −5.46), which may impact its formulation and systemic exposure. Despite one Lipinski violation and a moderate bioavailability score (0.55), Tolnaftate’s strong binding affinity and high GI absorption highlight its potential for repurposing with structural optimization. 2-methyl-7-phenylindole) and 2-ethylacridine also displayed good BBB permeability and acceptable drug-likeness based on multiple filters (Ghose, Veber, Egan). However, both showed slightly lower bioavailability scores (0.55) and one or more Muegge filter violations, suggesting that while they meet basic drug-likeness criteria, further optimization may be needed to enhance pharmacokinetic properties.

Toxicity predictions using the ProTox-3.0 platform revealed varying safety margins among the top five compounds. 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid and Tolnaftate had the highest predicted LD50 values (6,500 mg/kg and 6,000 mg/kg, respectively), classifying them under toxicity class 6, indicating a relatively low acute toxicity risk. In contrast, (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid, 2-methyl-7-phenylindole, 2-ethylacridine were assigned to toxicity class 4, suggesting moderate toxicity, with (9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid having a notably lower LD50 of 1,200 mg/kg.

Organ-specific toxicity predictions showed that hepatotoxicity and neurotoxicity were more prevalent among the indole and acridine derivatives (Tolnaftate, 2-Methyl-7-phenylindole and 2-ethylacridine), while 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid and (9-Oxo-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-yl)acetic acid had fewer flagged toxicities. Although Tolnaftate showed good pharmacokinetics and binding affinity, it was flagged for mutagenicity, neurotoxicity, and clinical toxicity, potentially limiting its application without structural modification. Conversely, 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid was predicted to be free from major organ-specific, mutagenic, or carcinogenic effects, reinforcing its potential as a lead compound with both efficacy and safety. All compounds were predicted to be blood-brain barrier permeable, which may be advantageous for treating cerebral malaria but also requires caution due to potential central nervous system (CNS) effects. The ecotoxicity profile of Tolnaftate, 2-Methyl-7-phenylindole and 2-ethylacridine also suggests environmental risk considerations during large-scale development.

Among the GC–MS-identified constituents, 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid exhibited the strongest binding affinity to PfLDH (−7.7 kcal/mol) and formed key stabilizing interactions with active-site residues such as Phe100 and Asp53. These residues are critical for cofactor anchoring and have been similarly targeted by other potent PfLDH inhibitors reported in previous studies (Kayamba et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2023). The compound’s π–π stacking with aromatic residues and hydrogen bonding to catalytic residues suggest a binding mode that could competitively inhibit NADH binding. In silico ADME and toxicity profiling further indicated high gastrointestinal absorption, blood–brain barrier permeability, compliance with Lipinski’s rule of five, and low acute toxicity (toxicity class 6), collectively supporting its potential as a drug-like lead. The fluorene scaffold is well-recognized in medicinal chemistry for its chemical stability and versatility, and structural analogues have demonstrated diverse pharmacological activities, including antimalarial effects (Liu et al., 2024). Given its favorable binding and safety profile, 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid represents a promising candidate for further optimization. Future work should focus on structural modification of the fluorene core to enhance affinity and selectivity toward PfLDH, followed by in vitro enzyme inhibition assays and in vivo P. falciparum validation.

5 Limitations

While the molecular docking and dynamics simulations were performed using PfLDH due to its well-characterized crystal structure, this enzyme shares substantial sequence and structural similarity with P. berghei LDH (Winter et al., 2003). Therefore, the observed in vivo antiplasmodial effects of the extract in P. berghei–infected mice may, at least in part, be attributed to similar inhibitory interactions at the LDH active site. However, the generalizability of these findings to other Plasmodium species, particularly P. falciparum infections in humans, requires further validation through in vitro assays and clinical studies. Nonetheless, direct structural or enzymatic studies on P. berghei LDH would be required to confirm these mechanistic predictions.

Additionally, the GC–MS analysis used in this study provided preliminary phytochemical profiling but does not offer definitive structural confirmation or quantification of all compounds. Follow-up studies using advanced spectroscopic techniques such as NMR and LC–MS/MS would be necessary to confirm the identities and relative concentrations of the bioactive constituents. Moreover, while in silico ADME and toxicity predictions offer valuable early-stage insights, they do not substitute for empirical pharmacokinetic and toxicological evaluations. In vivo absorption, metabolism, organ-specific toxicity, and long-term safety profiles of the active compounds remain to be investigated.

Finally, this study focused primarily on parasitemia suppression as a primary efficacy marker. Hematological and biochemical parameters, which provide important insights into the systemic impact and safety of candidate antimalarial agents were not evaluated. Future studies will incorporate such parameters to comprehensively assess host response and potential off-target effects.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study represents the first integrated application of GC–MS profiling, curative in vivo antimalarial evaluation, and molecular docking/molecular dynamics simulations targeting PfLDH using compounds derived from CLE of V. ambigua. The findings demonstrate the significant antiplasmodial activity of the CLE in P. berghei infected mice and revealed multiple bioactive constituents with strong predicted PfLDH inhibitory activity, favorable pharmacokinetic properties, and acceptable safety profiles. These results support the potential of V. ambigua as a promising source of novel antimalarial lead compounds. Given their drug-like characteristics, the identified molecules, including 9H-fluorene-4-carboxylic acid and Tolnaftate, warrant further preclinical development involving compound isolation, structure–activity relationship studies, and evaluation in P. falciparum models to advance their translational potential. Tolnaftate, although present in low abundance in the extract, demonstrated a strong predicted binding affinity to the PfLDH active site and favorable ADME–Tox properties. Its established clinical use as an antifungal drug suggests potential for repurposing, making it a compound of particular interest for further validation in malaria models.

Statements

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by University Health Research and Ethics Committee of Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, and registered under the reference number NHREC/UDU/-HREC/25/06/2023–UG70. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AY: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Resources, Conceptualization, Project administration, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. AA: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis. MS: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. JA: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing – review and editing, Investigation. NS: Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing, Software. KY: Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation. AU: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review and editing, Software, Formal Analysis. MI: Visualization, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review and editing, Supervision.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledged the efforts of Mal. Hamza Muhammad of Department of Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry for his guidance during extraction, Mal. Abubakar Usman from the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology for his assistance during the antimalarial studies, and Kannan R.R. Rengasamy, Centre for High-Performance Computing (CHPC), South Africa, for providing computational resources to this research project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fddsv.2025.1635697/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Aguiar A. C. C. da Rocha E. M. de Souza N. B. França T. C. Krettli A. U. (2012). New approaches in antimalarial drug discovery and development: a review. Memorias do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz107, 831–845. 10.1590/s0074-02762012000700001

2

Belete T. M. (2020). Recent progress in the development of new antimalarial drugs with novel targets. Drug Des. Dev. Ther.14, 3875–3889. 10.2147/DDDT.S265602

3

Bhat V. Chatterjee J. (2021). The use of in silico tools for the toxicity prediction of potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2. Altern. Laboratory Animals49 (1-2), 22–32. 10.1177/02611929211008196

4

Builders M. (2015). Plants as antimalarial drugs: a review. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.44 (08), 1747–1766. 10.3923/ijp.2011.238.247

5

Builders M. I. Wannang N. N. Ajoku G. A. Builders P. F. Orisadipe A. Aguiyi J. C. (2011). Evaluation of the antimalarial potential of Vernonia ambigua kotschy and peyr (asteraceae). Int. J. Pharmacol.7 (2), 238–247. 10.3923/ijp.2011.238.247

6

Das N. Prabhu P. (2022). Emerging avenues for the management of cerebral malaria. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.74 (6), 800–811. 10.1093/jpp/rgac003

7

Dunn C. R. Dunn C. R. Banfield M. J. Barker J. J. Higham C. W. Moreton K. M. et al (1996). The structure of lactate dehydrogenase from Plasmodium falciparum reveals a new target for anti-malarial design. Nat. Struct. Biol.3 (11), 912–915. 10.1038/nsb1196-912

8

Frederich M. Tits M. Angenot L. (2008). Potential antimalarial activity of indole alkaloids. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg.102 (1), 11–19. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.10.002

9

Gondim B. L. da Silva Catarino J. de Sousa M. A. D. de Oliveira Silva M. Lemes M. R. de Carvalho-Costa T. M. et al (2019). Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery: blood-brain barrier as the main obstacle to treating infectious diseases in CNS. Curr. Pharm. Des.25 (37), 3983–3996. 10.2174/1381612825666191014171354

10

Gwandu U. Z. Dangoggo S. M. Faruk U. Z. Halilu E. M. Yusuf A. J. Mailafiya M. M. (2020). Isolation and characterization of oleanolic acid benzoate from the ethylacetate leaves extracts of Vernonia ambigua (kotschy ex. Peyr). J. Chem. Soc. Niger.45 (5). 10.46602/jcsn.v45i5.518

11

Jachak S. M. Saklani A. (2007). Challenges and opportunities in drug discovery from plants. Curr. Sci., 1251–1257. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24097892

12

Jo S. Kim T. Iyer V. G. Im W. (2008). CHARMM‐GUI: a web‐based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem.29 (11), 1859–1865. 10.1002/jcc.20945

13

Johnson T. O. Adegboyega A. E. Johnson G. I. Umedum N. L. Bamidele O. D. Elekan A. O. et al (2023). Uncovering the inhibitory potentials of Phyllanthus nivosus leaf and its bioactive compounds against plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase for malaria therapy. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.41 (19), 9787–9796. 10.1080/07391102.2022.2146750

14

Kayamba F. Faya M. Pooe O. J. Kushwaha B. Kushwaha N. D. Obakachi V. A. et al (2021). Lactate dehydrogenase and malate dehydrogenase: potential antiparasitic targets for drug development studies. Bioorg. and Med. Chem.50, 116458. 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116458

15

Kumar S. Bhardwaj T. R. Prasad D. N. Singh R. K. (2018). Drug targets for resistant malaria: historic to future perspectives. Biomed. and Pharmacother.104, 8–27. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.009

16

Kumar V. Garg V. Dureja H. (2022). Role of traditional herbal medicine in treatment of malaria. TMR Mod. Herb. Med.5 (4), 20. 10.53388/mhm2022b0816001

17

Liu H. Zhou H. Xing J. (2024). The antiplasmodial activity of the carboxylic acid metabolite of piperaquine and its pharmacokinetic profiles in healthy volunteers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.79 (1), 78–81. 10.1093/jac/dkad349

18

Lorke D. (1983). A new approach to practical acute toxicity testing. Archives Toxicol.54 (4), 275–287. 10.1007/BF01234480

19

Omar F. Tareq A. M. Alqahtani A. M. Dhama K. Sayeed M. A. Emran T. B. et al (2021). Plant-based indole alkaloids: a comprehensive overview from a pharmacological perspective. Molecules26 (8), 2297. 10.3390/molecules26082297

20

Peters W. Portus J. H. Robinson B. L. (1975). The chemotherapy of rodent malaria, XXII: the value of drug-resistant strains of P. berghei in screening for blood schizontocidal activity. Ann. Trop. Med. and Parasitol.69 (2), 155–171. 10.1080/00034983.1975.11686997

21

Phillips J. C. Braun R. Wang W. Gumbart J. Tajkhorshid E. Villa E. et al (2005). Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem.26 (16), 1781–1802. 10.1002/jcc.20289

22

Ryley J. F. Peters W. (1970). The antimalarial activity of some quinolone esters. Ann. Trop. Med. and Parasitol.64 (2), 209–222. 10.1080/00034983.1970.11686683

23

Samuel B. B. Oluyemi W. M. Johnson T. O. Adegboyega A. E. (2021). High-throughput virtual screening with molecular docking, pharmacophore modelling and ADME prediction to discover potential inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum lactate dehydrogenase (PfLDH) from compounds of combretaceae family. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. (TJNPR)5 (9), 1665–1672. 10.26538/tjnpr/v5i9

24

Shoemark D. K. Cliff M. J. Sessions R. B. Clarke A. R. (2007). Enzymatic properties of the lactate dehydrogenase enzyme from Plasmodium falciparum. FEBS J.274 (11), 2738–2748. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05808.x

25

Singh S. V. Manhas A. Kumar Y. Mishra S. Shanker K. Khan F. et al (2017). Antimalarial activity and safety assessment of Flueggea virosa leaves and its major constituent with special emphasis on their mode of action. Biomed. and Pharmacother.89, 761–771. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.056

26

Siqueira-Neto J. L. Wicht K. J. Chibale K. Burrows J. N. Fidock D. A. Winzeler E. A. (2023). Antimalarial drug discovery: progress and approaches. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.22 (10), 807–826. 10.1038/s41573-023-00772-9

27

Thu A. M. Phyo A. P. Landier J. Parker D. M. Nosten F. H. (2017). Combating multidrug‐resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. FEBS J.284 (16), 2569–2578. 10.1111/febs.14127

28

Trott O. Olson A. J. (2010). AutoDock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.31 (2), 455–461. 10.1002/jcc.21334

29

Uba A. I. Weako J. Keskin Ö. Gürsoy A. Yelekci K. (2020). Examining the stability of binding modes of the co-crystallized inhibitors of human HDAC8 by molecular dynamics simulation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.38 (6), 1751–1760. 10.1080/07391102.2019.1615989

30

Uzor P. F. (2020). Alkaloids from plants with antimalarial activity: a review of recent studies. Evidence‐Based Complementary Altern. Med.2020 (1), 8749083. 10.1155/2020/8749083

31

Vanommeslaeghe K. Hatcher E. Acharya C. Kundu S. Zhong S. Shim J. et al (2010). CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug‐like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all‐atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem.31 (4), 671–690. 10.1002/jcc.21367

32

Varo R. Chaccour C. Bassat Q. (2020). Update on malaria. Med. Clínica Engl. Ed.155 (9), 395–402. 10.1016/j.medcli.2020.05.010

33

Wangkheirakpam S. (2018). “Traditional and folk medicine as a target for drug discovery,” in Natural products and drug discovery (Elsevier), 29–56. 10.1016/B978-0-08-102081-4.00002-2

34

Wicht K. J. Mok S. Fidock D. A. (2020). Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.74 (1), 431–454. 10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115546

35

Winter V. J. Cameron A. Tranter R. Sessions R. B. Brady R. L. (2003). Crystal structure of Plasmodium berghei lactate dehydrogenase indicates the unique structural differences of these enzymes are shared across the plasmodium genus. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol.131 (1), 1–10. 10.1016/S0166-6851(03)00170-1

36

World Health Organization (2019). World malaria report 2019. World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565721 (Accessed December 04, 2019).

37

World Health Organization (2022). World malaria report 2022. Geneva: WHO. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2022 (Accessed August 05, 2025).

38

World Health Organization (2023). World malaria report 2023. Geneva: WHO. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023 (Accessed August 05, 2025).

39

World Health Organization (2024). World malaria report 2024. Geneva: WHO. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2022 (Accessed August 05, 2025).

Summary

Keywords

Vernonia ambigua , median lethal dose, antiplasmodial activity, characterization, GC–MS, Plasmodium berghei , in silico docking

Citation

Yusuf AJ, Alpha A-RA, Salihu M, Aminu J, Sahin NMM, Yelekçi K, Uba AI and Imam MU (2025) Integrated in vivo and in silico evaluation of antimalarial compounds from Vernonia ambigua leaves identified by GC-MS profiling. Front. Drug Discov. 5:1635697. doi: 10.3389/fddsv.2025.1635697

Received

08 June 2025

Revised

16 October 2025

Accepted

04 November 2025

Published

09 December 2025

Volume

5 - 2025

Edited by

José L. Medina-Franco, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

Reviewed by

Sherif Hamidu, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, United States

Sonali Mishra, Washington University in St. Louis, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yusuf, Alpha, Salihu, Aminu, Sahin, Yelekçi, Uba and Imam.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amina J. Yusuf, amina.yusuf@udusok.edu.ng

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.