- 1International Water Management Institute, Lalitpur, Nepal

- 2International Water Management Institute, Colombo, Sri Lanka

- 3Independent Researcher, Kathmandu, Nepal

The enactment of a new Constitution in 2015 in Nepal marked a shift to a representative system of federal governance. Earlier in 2002, the country's Tenth Five Year Plan had committed to a core focus on gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) in national policies and governance. How do these two strategic shifts in policy align in the case of WASH projects in rural Nepal? Applying a feminist political lens, we review the implementation of WASH initiatives in two rural districts to show that deep-rooted intersectional complexities of caste, class, and gender prevent inclusive WASH outcomes. Our findings show that the policy framing for gender equitable and socially inclusive outcomes have not impacted the WASH sector, where interventions continue as essentially technical interventions. While there has been significant increase in the number of women representatives in local governance structures since 2017, systemic, informal power relationship by caste, ethnicity and gender entrenched across institutional structures and cultures persist and continue to shape unequal gender-power dynamics. This is yet another example that shows that transformative change requires more than just affirmative policies.

1. Introduction

This paper explores the linkages between water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) in local governments and the processes of federalism on inclusive WASH in Nepal. The Constitution (2015) signifies a new journey in Nepal's political history for inclusive water governance and development in general and the WASH sector particularly. Article 30 of the Constitution ensures the fundamental right of individuals to live in a healthy and clean environment, and Article 35 (4) ensures fundamental right to clean water and hygiene. The principles of gender equality, social inclusion, justice, and non-discrimination are well articulated in different articles, including in the Preamble to the Constitution [GON (Government of Nepal), 2015]. The constitution builds on the foundation for gender transformative changes mentioned in the Tenth Five Year Plan (2002-2007). If implemented well, these two policies in complementarity would accelerate reliable and safe water supply services targeted to women and marginalized groups1 including Dalits, ethnic minorities and indigenous groups, and people with disabilities.

In Nepal, only 28% of the piped water supply systems are functional [DWSSM (Department of Water Supply and Sewerage Management), 2019], and less than 19% of the population have access to safely managed water services [CBS (Central Bureau of Statistics), 2020]. These challenges are increasingly impacted by climate change (Chapagain et al., 2019). Despite the universality of water supply problems and constraints, those most affected are marginalized communities, and particularly women and girls amongst them (Water Aid, 2017). In both rural and urban locations in Nepal (as elsewhere in South Asia), women and girls are primarily responsible for water-related domestic and productive work—fetching water for drinking and domestic use, for cooking, cleaning, washing at home, for sanitation hygiene, for livestock and homestead. In situations of increasing water scarcity, women, especially from poor and disadvantaged castes households are least able to invest in alternative sources of water (Water Aid, 2017; Shrestha et al., 2020). These women are also least able to influence water decision-making or its equitable use, as they are often excluded from local social networks (Water Aid, 2009; Leder et al., 2017). These challenges can be particularly constraining for women and girls with disabilities. There are reports of domestic abuse, gender-based violence and physical, emotional and health challenges for persons with disabilities in collecting and managing water for WASH (Sommer et al., 2015; Pommells et al., 2018).

There is also mention in the 2015 Constitution, of the State's responsibility to prioritize national investments in water resources development based on people's participation and making a multi-utility development of water resources. The 2015 constitution facilitated the introduction of a three tiered federal governance system. This Constitutional provision, which specifies authority and jurisdictions at three levels of government reshapes formal authority, functions and administrative systems for water and WASH services [GON (Government of Nepal), 2015]. As discussed below, these changes in principle enable and require local governments to plan and implement inclusive WASH services and decision-making.

Our focus in this paper was to assess how these two strategic shifts in policies, namely GESI and Federalism align in the case of WASH projects in rural Nepal. More specifically, have these processes led to transformative change, helped dismantle deep-rooted and intersectional gender-power dynamics at scale?

We conducted primary data collection in two locations: Dailekh in the hilly region of the Western district in Nepal has 11 local governments, while Sarlahi located in the lowlands, being more densely populated has 20 local governments. Jobs and incomes in agriculture are reported to be on the decline and increasingly unreliable in both in Dailekh and Sarlahi, even though due to better road accessibility and the development of small local industries, off-farm opportunities are available in Sarlahi. As in many rural locations in Nepal, there is seasonal and long-term outmigration of mostly men from both locations to major cities in Nepal, to India and the Gulf countries.

In Sarlahi, groundwater is the main source for irrigation and drinking. Compared to Dailekh, it is relatively easier and more affordable to install private, individual tube wells in Sarlahi. However, there are reports of high risks of ground water contamination in Sarlahi (SNV and CBM, 2019), and the cost for installing even a shallow tube well is not affordable to the poorest households, who must rely on communal water sources, which are mostly contaminated. Springs, pipes connected to an open water source (spring or stream), or community or private tap connections from a gravity-fed water supply system are the main sources of water for domestic uses in Dailekh.

This paper has five sections. After introducing the research context in the first section, we discuss the potential of federalism in Nepal for more inclusive WASH outcomes based on an analysis of policies. The third section introduces analytical framework and methodology of the research, including an overview of the research location. The fourth section is an analytical overview of how gender and social inclusion shapes the structure and functioning of newly established federal government institutions, as well as the potential of these systems for implementing more inclusive WASH services. In the final section, we analyze the intersections between federalism, GESI and WASH as seen in our research locations.

2. Federalism in Nepal: pathways to transformational change?

On September 20, 2015, Nepal adopted a three-tiered federal system of governance. The subsequent formation of local, province and federal governments was initiated in 2017. These changes are a progression of historic shifts in Nepal, the move from a monarchy to a centralized democratic government to now—shared legislative, executive, and judicial functions and powers between federal, provincial, and local governments (Sharma, 2020; Khadka et al., 2021). The new federal structure consists of 753 local governments (each local government body consisting of a number of wards), 7 provincial and 1 federal government, each with constitutional powers to enact laws, prepare policies, budgets and mobilize their own resources (Shrestha, 2019). It is important to point out that, prior to federalism, local authorities did not have legislative powers on WASH, although they could make development strategies, budgets, plans and programmes for water supply and sanitation (Water Aid, 2005).

These shifts are particularly interesting in Nepal, given that a national mandate to integrate GESI in all development policies and interventions, particularly in relation to governance, had been announced in the Tenth Five Year Plan, 2002–2007, (National Planning Commission, 2002). Put together, this would enable women to constitute at least one-third of federal and provincial assemblies, and 40% of the local government institutions, as well as a proportionate representation of marginalized groups in all three federal bodies. In the elections that followed in 2017, women made 39.8% of the total elected representatives [ECN (Election Commission Nepal), 2017] and 47% of elected women were Dalits and 8% Muslims (Paswan, 2017). This was a historic achievement. However, in the 2022 local elections, only 19% of the elected representatives were Dalit women (Nepali, 2022), showing a major decline. Limited interests of political parties to address social discrimination, male dominated political leadership and advisory bodies, lack of laws that ensure inclusion of marginalized women in the candidate selection criteria and process during the elections, and gendered stereotypes in the mindsets of political leaderships are contributors to declining women's representation in local governments (Nepali, 2022; Shrestha et al., 2022).

Likewise, though the percentage of elected women representatives at the 2022 local election saw a slight increase (41.22%), only 3.02% were elected as Mayor or Chairperson and 74.2% were Deputy-Mayors or Vice-Chairpersons (ECN, 2022). The GESI provisions have also contributed to ensure 33% women's representation in the federal parliament in the federal system [GON (Government of Nepal), 2015]. Prior to the federal system, women's representation in the House of Parliament was only 6% (Uehara, 2019).

GESI combined with a federal three-tiered governance structure, allows in principle, a politically inclusive space. At its lowest administrative tier, each ward2 committee—the political constituency of local government has the mandate to deliver all public services, including WASH. The ward committees are also tasked with the identification and implementation of development priorities in an inclusive way, as well as approval of policies, plans, programs, and budgets during assembly of their local government.

GESI principles integrated into the new federal structure thus presented an opportunity for political, economic, and social transformation like never before [SDC (Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation), 2018; Clement et al., 2019]. This new system would provide space for the formerly excluded to engage in and inform processes of governance in various ways.

Firstly, federalism requires not only administrative, but also financial transformations across government levels. In Nepal, this equation is important, as almost half of the centralized development financing relies on foreign aid (Khadka et al., 2020). Multilateral and bilateral development partners are active in the WASH sector extending their support from WASH service delivery to policy strengthening (Ministry of Finance, 2021; Joseph and Shrestha, 2022). To what extent would these policy changes deliver in situations of consistently low public investment for WASH (below 3%)?

Secondly, while federalism is new and evolving in Nepal, gender has been the commitment of international development partners for many decades [IDPG (International Development Partners Group), 2017]. In Nepal's case, the country's decade long Marxist political conflict (which ended in 2006) was instrumental in enabling a focus on social inclusion as a bottom-up, political discourse (Druckza, 2016). The armed conflict was also instrumental in resulting in the fall of a centralized exclusionary socio-political and state structure, (the monarchy) into a more representative, democratic system of constitutional governance (Hutt, 2004; Sharma, 2014). Increasingly, more roles and powers have been devolved to local governments for administering water supply, basic sanitation and hygiene infrastructure and services. Regardless of these shifts, power hierarchies and ideologies, inequalities by gender, caste, ethnicity and class continue to persist and shape unequal access to public services, resources, opportunities and decision-making processes [IDPG (International Development Partners Group), 2017; Gurung et al., 2020].

Unlike in the pre-federal system, local governments can now exercise 22 exclusive or single and 15 shared or common rights. Schedule 8 assigns local government exclusive rights on local water supply, irrigation, and watershed conservation, basic health, and sanitation. The Local Government Operation Act (LGOA) enacted in 2017 facilitates to develop and implement policies and annual plans related to WASH. Article 24 (2) of the LGOA 2017 requires local governments to consider GESI and governance aspects when preparing long-term and short-term development plans and programmes in their jurisdictions [GON (Government of Nepal), 2017]. These legal frameworks offer local governments the autonomy and power to develop, implement and monitor policies, plans, and programmes related to water for irrigation, including WASH. Have these national legal frameworks for implementing federalism translated into local level strategies and practices for promoting inclusive WASH? This is what we wanted to assess.

Understanding these linkages among GESI, WASH and federalism is critical for WASH sector policymakers and practitioners. This study provides evidence of the opportunities as well as challenges of these policy changes in implementing inclusive WASH development in a federal system.

3. Analytical framework and methodology

There are several interesting insights in assessing the roll out of GESI and federalism in relation to WASH governance. Guided by a Feminist Political Ecology (FPE) approach, our analysis of how WASH institutions, interventions, and outcomes are shaped by recent policy reforms of a GESI-informed devolution3—shows that gender-power dynamics continues to play out and shape newly formed institutional structures and spaces of governance. This requires analyzing relationships of power in political processes of decision making; assessing the changing relations between nation-state institutions and local communities; the engagement of diverse actors in the circulation of goods, services, and knowledges; and the gendered outcomes of these changes in private and public spaces (Bedford and Rai, 2013).

In understanding how deep-rooted gender norms play out at the intersect of poverty, age, ethnicity, disability in determining access to and control over water resources, it is essential to go beyond binary (women versus men) narratives (Leder et al., 2017; Shrestha et al., 2020). Unfortunately, the consideration of gender in WASH largely ignores the complexity of intersectional inequalities [ADB (Asian Development Bank), 2012; Leder et al., 2017; White and Haapala, 2018; Shrestha et al., 2020].

Gender research in Nepal by feminist scholars has extensively unpacked intersectional inequalities at the community level (Lama and Buchy, 2002; Nightingale, 2011; Leder et al., 2017), as well as gender-power disparities in water institutions (Udas and Zwarteveen, 2010; Liebrand and Udas, 2017; Shrestha and Clement, 2019). Feminist scholars argue that the disparities and exclusions are shaped not only by gender norms, but also by local contexts. In other words, economic, political and social contexts both at a national and local levels determine vastly different outcomes for similar or the same technical agenda (Joshi et al., 2011; Shrestha and Clement, 2019).

In both study areas, women's work in agriculture has increased due to male out-migration, coupled with the burdens of domestic work, made more challenging due to unreliable water supply. Climate impacts in both Dailekh and Sarlahi shape increasing water shortages. Water roles have become especially challenging in Dailekh—where women and young girls report walking longer and further away across the rugged terrain to fetch water.

In both locations, we noted that the Dalit women are the poorest and marginalized in multiple ways. On paper, exclusionary social practices that distinguished Dalits as “achhuyt” (“untouchable”) and historically prevented Dalit women and girls from accessing water from community water supply systems are addressed through policy reforms. In practice, Dalit women in Dailekh and Sarlahi (as elsewhere in Nepal, see Shrestha et al., 2020) report aggression and even violence from non-Dalits, including from other women—if they touch (access) public water taps or spring sources.

As we will discuss throughout this paper, access to and availability of water is shaped not just by gender and caste, but equally poverty and ethnicity. Brahmin, Chhetri, Thakuri (Khas Arya) and Janjatis (e.g., Gurungs, Thakalis)4 are economically better-off than Dalits and other marginalized minorities. This allows them to invest in private and public piped water supply schemes. These groups also inform and influence the installation of new water infrastructure. In contrast, a relative inability to pay, as well as being at the bottom of social power hierarchy means that Dalits and other marginalized groups are relatively less able to influence program interventions, to access improved water supply infrastructure. On the other hand, ethnic marginalized groups struggle to be heard in a still “Nepali language dominant” institutional culture. We discuss these issues in greater detail in the finding section below.

Our application of a FPE approach in this paper can be summarized through two inter-related axes of analysis: the relational dimensions of gender and power in governance structures and process, and the outcomes of these in terms of WASH know-how.

Power is complex, fluid, relational (Parpart et al., 2002) and manifest in social relations and engagements (Foucault, 1978). Power can be exercised through visible tangible changes as in formal rules, structures, institutions; as well as informally, through less visible social norms, beliefs, behaviors, perceptions and mind-sets (Veneklasen and Miller, 2007).

For example, federalism is a formal, visible change, which in principle can provide political spaces and rights for local communities, including marginalized groups to be represented in, and shape political spaces, structures, and outcomes. However, invisible or informal power—such as masculinity, caste-based disparities, values and mindset, can continue to create barriers for socially inclusive politics, policies and development (Hillenbrand et al., 2015).

Individuals often exercise or experience power through their inclusion/exclusion in social networks and relations (Eyben, 2006). Nepal is a very diverse and unequal society. The idea of “afno manche” [social links] and informal networks are deeply entrenched in all forms of engagement, including public service delivery and access (Bista, 1991). Khadka (2009) points out that in Nepal, influential political actors (male, advantaged castes) have been able to undermine inclusion in policymaking spaces—informally.

Techno-engineering and biophysical perspectives and knowledge systems predominantly shape natural resources related development services and interventions (Nightingale, 2005; Gonda, 2016). Engineering practices in the field of irrigation and water resources development in Nepal are unable to promote social transformation by challenging the deeply rooted gender discrimination, exclusion and masculine culture (Liebrand, 2021). WASH solutions presented in a technical narrative help avoid tackling the exclusion of marginalized groups in WASH service delivery and management at local and other institutional levels. Our focus here was in analyzing if federalism informed by GESI principles would allow changing these dominant techno-centric perspectives and facilitate the practice of more representative and inclusive governance, including a more transformative WASH program implementation.

Applying these concepts, our interest was to understand how women marginalized by their gender, caste, class, age, and disability experience and participate in the process and roll out of federalism, in the face of deeply entrenched masculine and exclusionary values, norms and mindsets.

3.1. Methods

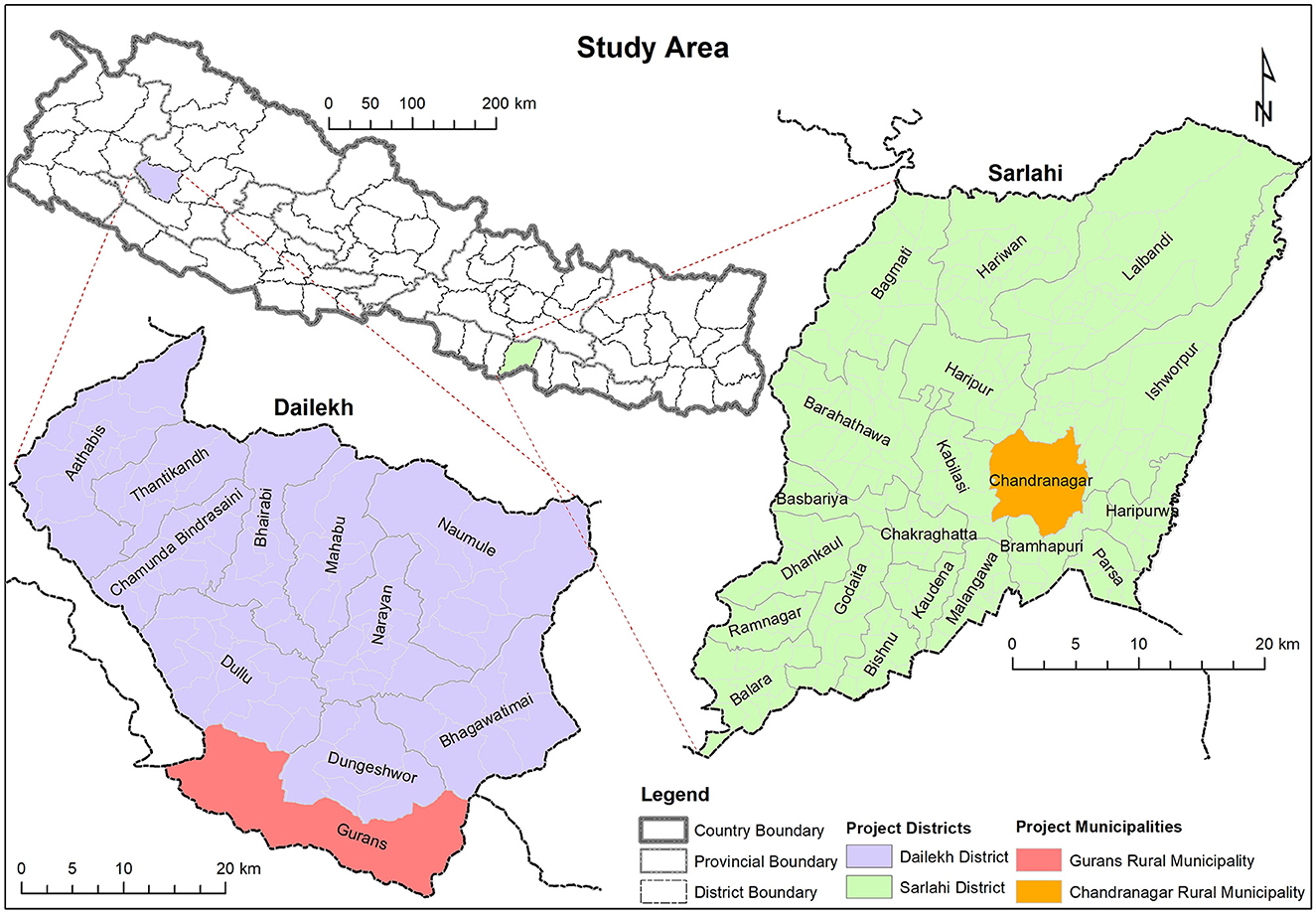

We applied qualitative methods to collect and analyse primary and secondary data in two rural municipalities (RMs), namely Chandra Nagar RM in Sarlahi district of the eastern Terai region of Nepal and Gurans RM in Dailekh district of western Nepal (Figure 1). The qualitative approach allows researchers to answer insights about lived experiences, meaning and perspectives of participants interviewed (Hammarberg et al., 2016). These rural municipalities were the IWMI Nepal's research project on WASH and we worked with local partners to implement this project.

Primary data were collected through 12 semi-structured interviews (with 5 women, 7 men undertaken through two field visits in June and December of 2019). Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic restricted field visits in 2020 and 2021. Thus, we conducted 15 additional phone interviews in 2020 and 2021 with different respondents (nearly 1 hour with 7 women and 8 men). For these interviews, we purposedly selected representatives of different stakeholder groups, including elected representatives, engineers, health workers, and non-technical staff of RMs and chairpersons and members of Water User and Sanitation Committees, NGOs and project staff working on WASH projects in the study areas. In 2021, we conducted follow up interviews with elected representatives, especially Chairpersons and vice-chairpersons of the RMs studied who were interviewed in 2019 for data verification. Dialogues with local stakeholders were conducted through local FM stations in Dailekh and Sarlahi, and webinars with national level WASH policymakers and practitioners were also held between 2020 and 2021. Moreover, ethical approval was secured through the internal review board of the International Water Management Institute, and ethical procedures were followed accordingly in the research process. We explained to the interviewees about the purpose of the research, interviews and the processes of maintaining confidentiality of respondents and information they shared with researchers.

We used the qualitative research strategies (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) for coding and deriving categories/themes based on the interviews data. We coded and analyzed the interviews data manually. We developed the categories based on the common patterns emerged in the interview data along with reflective notes of researchers maintained during data collection and analysis. Key categories generated to analyse barriers related to GESI inclusive WASH practices include knowledge, capacity, financial resources, language, gendered perception, networks, intersectional inequality and power relations in decision-making.

Key literature and official documents on WASH were also reviewed to analyze policy commitments on rights, inclusive water, governance structures, and formal power sharing, and their implications for the WASH sector. We reviewed the Constitution of Nepal and three water resources and WASH related policies prepared after the federalism to understand the policy commitments on inclusive WASH and gaps in implementation level.

4. Findings

4.1. Changes in powers/jurisdictions and its implications for inclusive WASH

In the new/federal system, all the three levels of government have both exclusive and concurrent rights relating to policymaking and the program planning and implementation of water resources and water supply, although constitutionally, laws prepared by federal legislators will prevail in case of conflicts [DRCN (Democracy Resource Center Nepal), 2020, p. 4]. All levels of government having both exclusive and concurrent rights impact WASH in various ways. Each level of government, within their exclusive jurisdiction, can prepare policies, plans and programs for WASH sector's development. They can provide WASH services to the locals through engaging WASH projects partners; they can develop capacity for evidence-based policy development and implementation through partnership with research and academic institutions. However, the overlaps of roles and responsibilities between the three levels of government is creating confusions and hurdles for implementing WASH projects within a municipality. In our interviews, WASH staff of NGOs and RMs mentioned that poor coordination among federal, province and local level WASH projects being implemented in the same community pose a challenge to address WASH issues holistically.

“[…] implementing projects of federal, province and local government in the same municipality with no coordination is the main challenge. Coordination is taking place at the individual level, but not in an institutional level” (NGO staff, RM, Sarlahi, 20 December, 2019).

Although there have been efforts to reduce duplication of projects, there is a lack of long-term policy level coordination with local governments [DRCN (Democracy Resource Center Nepal), 2020]. Furthermore, as the jurisdiction of the three levels of government enshrined in the Constitution are ambiguous and contradict to each other across the level of government, a pro-active role at the federal government is needed to coordinate with provincial and local government to enact laws for operationalizing roles and responsibilities within the shared rights [DRCN (Democracy Resource Center Nepal), 2020]. In the absence of an updated legal framework, the overlap of jurisdiction for water resources between various tiers of government hampers implementation.

The provision for fiscal transfer and sharing of national revenue among three levels of government is a key milestone—subnational governments will now receive around 33% of the total federal budget to ensure people's access to effective public services such as water supply, sanitation, education (Devkota, 2020). This new fiscal arrangement in theory can provide increased inclusion and local control in WASH planning. However, as discussed in the following section, local governments in the study areas function with limited resources and human resources for delivering inclusive WASH services.

Since the devolution of power, finances and functions to the local level was operational before local policies and legal frameworks were developed, with many of the newly elected representatives who had no or limited experience of governance and limited skills and competency in development management struggled (Acharya, 2018; Acharya and Scott, 2021). These shortcomings were added to inadequate cooperation between elected representatives and state bureaucrats (Pokharel and Pradhan, 2020). Further, local elected representatives interviewed feel that financial and human resources allocated by the central government are inadequate. But, more importantly, they are also limited by the lack of a transformative attitude among federal policymakers. According to the chairperson of a rural municipality in Dailekh district,

“Sthaniya sarkar [Local government] is not empowered to exercise its powers and roles enacted in the Constitution. Rajyako shushasan pranali [state's governance system] has changed. Policymakers at the federal level have traditional mindsets and are not ready to be part of the change” (an elected representative of rural municipality, Dailekh, 6 June 2019).

Despite the GESI responsive national policy frameworks presented in the previous sections, our data show that in practice local governments have been unable to prioritize GESI. There is a disconnect between Constitutional commitments on GESI and sectoral legislations. For example, the draft Water Resources (Management and Regulation) Bill, 2020 (GON, 2020) acknowledges the knowledge, skills, and participation of local communities in water management, conservation, and sources protection. However, there is little explicit attention to GESI in water governance, decision-making, and benefit sharing. The lack of clarity added to the overlap of jurisdictions between the levels of government have posed challenges for WASH governance at the local level. Issues around capacity at the local level have further hampered progress on GESI.

4.2. Knowledge and capacity for inclusive WASH at the local level

The RMs authorities we interviewed, point out a lack of staff capacity on GESI-related WASH planning and implementation. In addition, in both official WASH institutions and newly elected governments, there is also the absence of specifically allocated budgets for GESI.

For example, each local government has budgetary provision for a technical engineer(s) position, although the budget may vary depending on rural and urban municipalities. There is no equivalent budget allocated to a GESI role. Similarly, WASH committees have been established at RM and community level, but GESI tasks are not defined. And to make the issue more complicated, knowledge, commitment to, and interest in WASH as well as GESI varies widely among the newly elected local leadership.

Perhaps impacted by the severity of water challenges, Gurans RM in Dailekh has established a WASH Coordination Committee and is preparing a municipal WASH strategy, which is required as per the RM's Water Supply and Sanitation Committee Act 2019. These tasks had not been initiated in Chandranagar RM in Sarlahi at the time of our research.

Regardless of the differences, a review of the annual programmes, budgets, and minutes of meetings in both RMs shows a limited vision, “political interest,” and knowledge for transformative WASH. The focus remains on the financing of new infrastructure development—and it is assumed that provision of new water infrastructure will benefit all, but especially women, who are tasked with water supply roles and responsibilities.

One of the locally elected leaders remarked that the compulsory inclusion of one-third women in local governance and water user committees—is an indicator of GESI success. However, local NGOs confirm that the “infrastructure centric” development perspectives and interests of local policymakers have not changed,

“[…] They are unable to think about gender and social inclusion in WASH strategically. Purbadhar Bikas (infrastructure development) such as road, electricity and other construction work is the priority of local elected representatives” (Executive Director, local NGO, Sarlahi, 20 December 2019).

The development approach and interest of local governments tend to invest mainly on public infrastructure such as road building and maintenance, building irrigation, canal water supply, and drainage. The priorities on infrastructure centric development are not only linked to how communities view the infrastructure as a symbol of development, but also local politicians want to extend their popularity by focusing projects that are highly visible to their direct constituencies and help them to earn votes during elections (Rai, 2020).

The lack of dedicated budget for GESI policy implementation and capacity building is another key barrier. The national annual WASH budget of the Government of Nepal is less than 3% (Water Aid, 2020). Although fiscal transfer has allowed local governments to develop and implement WASH programmes, they received less than 1% of the national annual WASH budget in FY 2018/19 (Water Aid, 2018). WASH services of the public sector also tend to be biased toward urban areas. Over 59% of the total national WASH budget in 2020/21 was allocated to urban WASH projects and of the total budget for the urban WASH projects, 31% is concentrated only in Kathmandu valley (Water Aid, 2020).

An analysis of the budget and annual plan of Chandranagar RM in FY 2018/19 shows that less than 2% of the total development budget was allocated to WASH, which was mostly used in the development of new WASH infrastructure. The RM also receives a WASH budget from sectors like education, physical infrastructure, and health; only 0.77% of the total annual WASH budget for sanitary pads distribution targeted at girls in public schools.

Gurans RM had a dedicated WASH budget line. One of the reasons for this difference could be that Gurans RM is one of the working areas of a rural water supply project supported by the Government of Finland. A small fraction of the budget is allocated to GESI activities that include capacity building of women, people with disability, and public awareness on harmful social norms (e.g. child marriage, Chaupadi) and WASH support to local schools. There are no budgetary allocations for GESI-related knowledge and capacity development for RM officials.

White and Haapala (2018) write that a lack of capacity among local governments is a key barrier to achieving inclusive water governance and GESI outcomes. Our findings show that shifting the focus from investments in infrastructure to spending on soft skills development and GESI know-how will be challenging, especially when financial resources are limited.

The 2022 Drinking Water and Sanitation Act is more progressive—referring to people's fundamental right to safe drinking water and sanitation (article 3.1), the preferential prior-use rights of individuals or groups to water sources they have used for domestic uses, even if the ownership of water sources remains with the State (article 4.2); the need for representation of women professionals and elected women representatives of local governments in the Drinking Water and Sanitation (DWS) service Tariff Fixation Commission and the Intergovernmental Coordination Committee (ICC) respectively (see article 28.3, article, 55.1.6); and the role of WASH civil society in providing feedback to the ICC regarding DWS policies, plans and implementation (article 55.5) (GON, 2022). To what extent does these inclusion provisions get implemented needs further research.

4.3. Gender and social inclusion in local WASH policymaking and decisions

4.3.1. Diversity in the institutional structure of local governments

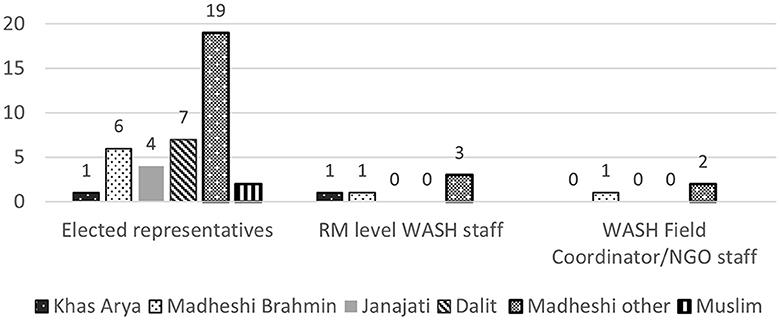

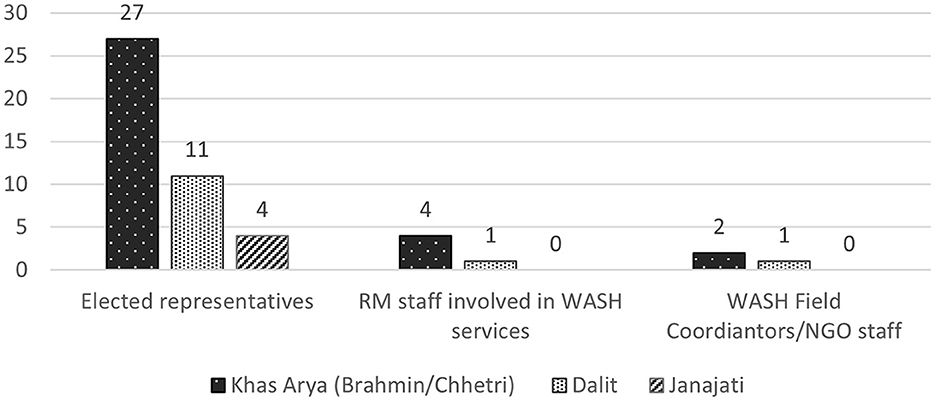

Three types of stakeholder groups are involved in WASH management and governance in the RMs studied (see Figure 2—Chandranagar RM and Figure 3—Gurans RM): elected representatives, public bureaucrats, including engineers, and NGO staff working for WASH projects in the RMs.

Figure 2. Caste and ethnicity dynamics of WASH actors in Chandranagar Rural Municipality, Sarlahi. Source: Field work (2020).

Figure 3. Caste and ethnicity dynamics of WASH actors in Gurans Rural Municipality, Dailekh. Source: Field work (2020).

No Dalits, ethnic and religious minorities occupy leadership positions in the state bodies, though Dalits are comparatively better represented in the RM assemblies; Kas Aryas outnumber in all the stakeholder groups in Gurans RM (Figure 3).

In Chandranagar RM, Khas Arya, Madhesh Brahmin, and Madhesh Other caste dominate in the RM assembly and WASH staffing, and WASH project field coordinator of local NGOs working in the RM (see Figure 2). Despite policy shifts, not much seems to have changed from earlier analyses [ADB (Asian Development Bank), 2012].

The representation of women in governance institutions has on the other hand changed dramatically. Women now constitute 40% of the elected representatives in local government, but as we discuss below, they still have little say in water governance.

The networks established among actors based on their gender, profession, and position reproduce old ideas and strategies and are difficult to break; they do not allow the entry of other actors with different perspectives and positions (Latour, 1999). The actor's networks and relationships do not challenge existing unequal power relations or support the empowerment of the powerless. The networks rather discourage women representatives, and diverse experiences and knowledge are not part of the local WASH politics, as discussed in the next section.

Interviews conducted in the study areas show that strong personal networks connect male elected leaders of the local government, influential civil servants, leaders of WASH projects and private sector actors. Elected heads of local water user and sanitation committees are also linked to the above-mentioned actors. Chief Administrative Officers (CAOs) who are the administrative head of RMs and coordinate local level budgeting and programming with the mayor/chairperson, the most powerful actors in law making of local governments—are all men (Rai, 2019).

Chairpersons (all men) of both RMs, closely interact with the chief administrative officers, head of finance and engineers of the RMs, and WASH service providers (e.g. local contractor of water supply infrastructure, WASH project coordinators, chairpersons of water user associations)—all of whom are male in the study areas. Elected women representatives, and especially if they are from marginalized communities are not part of these interactions and networks. When asked if they knew or could mention the name of an engineer or technical and financial staff serving in their RMs, none of the Dalit women elected representatives interviewed in both RMs were able to. When asked about her experience of being a local representative, a Dalit woman interviewed remarked,

“We [Dalits] are included in the Gaupalika because of Sanghiyata [federalism]. However, we are ignored in decision-making. Our chairperson's decisions matter the most. We don't know the decisions; he does not consult us. The situation would not be like that if we would have Dalit Adhakchya [Chairperson]” (Interview, Dailekh, 5 August, 2021).

While 92% of the deputy vice chair positions were occupied by women in the 2017 local elections, they are still struggling to meaningfully undertake their political roles. We analyzed how women's weak social ties with key actors like the local Chief Administrative Officers and Ward Chairpersons (all of whom are men) impacts inclusive water governance. Elected women representatives, especially if they are Dalit or from other marginalized groups—are not involved in the financial planning and budgeting of WASH and are also relatively unaware of water related policy issues. Elected women representatives expressed that the attitudes and behavior of their male counterparts was largely exclusionary. A woman vice-chairperson of a rural municipality in Dailekh explained,

“We [women] were able to come into the political roles due to arakchan niti [reservation policy]. Yet, it is a long way to be heard. Attendees laughed when I proposed an agenda for constructing a women-friendly toilet during an RM planning meeting. My voice was not heard; neither did the RM head supported my idea” (Interview, Dailekh, 30 September 2020).

The women representatives experience a deliberate undermining of their capacity to effectively function, due to a continued lack of information. Even if women elected leaders have the agency and political ability to participate in and contribute to local WASH decision-making, they are unable to do so. They feel unsafe raising their voices and vocal female leaders are not supported by their men counterparts.

When asked about water supply schemes in her ward, a woman ward representative remarked,

“We have khanepani yojana [drinking water scheme], but I don't know much about it. Our Oda Adhakchya [ward chairperson] better knows it because he is involved in this process” (Interview, 30 September 2020).

Women representatives experienced that they don't receive equal respect in the village assembly and in meetings with the male representatives, where they are often called out as being “incapable of undertaking political roles.” They report that they are always expected to be seated in the last rows—behind all the male representatives, who gather around the male RM Chairperson and Ward chairpersons. Nonetheless, women see their political inclusion through federalism, as a first step toward the opportunity to serve their constituencies. When asked what changes she observed in local development due to federalism, a woman representative in Dailekh said,

“Sanghiyata [Federalism] legitimatized local governments as the government nearest to the people. It has the power to prepare laws and policies and sets a priority for development, which was not possible in the previous system because the development process in the past was based on centrally planned and “top-down” (Interview, Dailekh, 5 June 2021).

The challenges faced by women are not similar. As we discuss below, women from marginalized groups are especially vulnerable to exclusions from any political space.

4.3.2. Intersectional power relations in shaping WASH agenda and developing political capacity

An intersectional dynamic (Thompson et al., 2017) around the participation among women representatives is evident in the study areas. The woman vice-chairperson in Gurans RM, belonging to an advantaged caste group, appears to be more aware of water supply activities of her RM, compared to her counterpart in Chandranagar RM who is a Dalit woman, low in the caste hierarchy. Language, family background, and social contacts are also prominent in determining difference and disparity. A Madheshi woman respondent in Sarlahi narrated the multiple challenges women in the Terai region face compared to women in the Hill region,

“Compared to Pahadi mahila [hill women], Terai mahila dherai pachhadi chhan [the situation of Terai women is far behind]. In Terai, we speak Maithili, but water supply and sanitation discussions are often held in the Nepali language. Social norms and perceptions discriminate against us. Society wants to see men as the head of the household and communities. A married woman still needs to cover her head when interacting with other male members, except her husband, although the compulsory wearing of the veil is slowly changing” (Interview, Sarlahi, 5 August 2021).

Rai (2019, p. 6–7) confirms that language is a key barrier to marginalized women—as we observed amongst Terai women representatives in meetings conducted with other executive, official post-holders. Dalit women in Sarlahi were particularly excluded in relation to access to information, social networks, and participation in local WASH planning. The dominance of Nepali language in formal and informal spaces further marginalizes these women, as well as Muslim women.

Similarly, Dalit women representatives speak of their “tokenistic” political representation: elected but consistently excluded from WASH planning and budgeting (Interview, 21 December 2019). A Dalit woman member mentioned that she goes with her husband to attend ward meetings to avoid humiliation during the meetings. She remarked,

“Our Ward Chairperson decides everything. His voice matters the most. We [Dalit women] are asked to sign off in the meeting minute. He completely ignores me in the ward meetings unless I go with my husband” (Interview, 21 December 2019).

As we discussed above, the move from a unitary to the federal governance system happens in the context of complex power inequalities and relationships—where the voices, rights and agency of women, particularly from marginalized groups remains blurred and silenced in institutional structures, planning and decision-making. In the final section below, we discuss how and why Federalism, GESI and WASH have not aligned and some pathways to consider to strengthen interlinkages between these.

5. Conclusion

Our research in the two rural municipalities reveals the gap between the intentions of federalization which is to provide more space and voice to local communities, especially for women and historically excluded groups, and the reality in the context of local WASH governance. Newly elected local governments are only just getting inducted into their political roles and responsibilities, and have limited vision, knowledge, and capacity both on WASH and GESI (White and Haapala, 2018).

The overlap of roles between the three levels of government for water resources along with a lack of legal framework to operationalize the constitutionally shared rights and roles are resulting in confusions for developing and implementing WASH programs. The lack of coordination among the WASH projects of federal and subnational governments at the local level also provides less opportunities for making WASH development programs sustainable and inclusive. Local governments in the study areas also function with limited skills and resources (e.g. budget, human resources, and capacity) to design and implement local WASH policies and programs beyond technical “fixes” approaches.

The political inclusion of women and historically marginalized groups in all levels of government has resulted in their physical access to “policymaking spaces.” However, deeply entrenched patriarchal mind-sets, beliefs, and power relations connect powerful local men in their roles as elected representatives and civil servants continue to obstruct women's full exercise of their rights. It will be an uphill task for women to dismantle these masculine spaces. Previous studies of local governance (Tamang, 2018; White and Haapala, 2018) also observed some of these gender barriers for elected women representatives.

We note that formal reforms in policy have not disrupted informal power and privilege, which continue to be skewed along the lines of gender, ethnicity, class, and caste. Policy reforms and political aspirations to inclusive WASH services and systems need to go well beyond “engineering fixes” and “technical solutions.” This calls for transforming mindsets, values, biases, as well as capacities and budgetary allocations at all levels of government. We suggest three pathways for narrowing the disconnection between GESI, WASH and federalism in Nepal.

An institutional practice is needed to monitor the allocation and expense of budgets, and human resources to design and implement local WASH policies, plans and programs that support inclusion and inclusionary outcomes of WASH development. Inclusive dialogues in local governments to overcome gender and social power differentials in planning and decision-making need to be facilitated; case studies to draw lessons from local governments experiences where women and disadvantaged groups are more involved in water and WASH planning and decision-making are needed to show case inclusive approaches and methods.

The implementation of federalism is evolving with the development of new legislation and plans in the WASH sector. International Development Partners through a dedicated funding for the Provincial and Local Governance Support Program (PLGSP) are committed to contribute to ensure that subnational governments are fully functional, sustainable, inclusive and accountable to their citizens (PLGSP, 2021). The program has also dedicated GESI strategy to enhance institutional and individual capacities among provincial and local governments to promote GESI during and beyond the program (PLGSP, 2021). To what extent new federal WASH legislation and the federalism implementation national programs such as PLGSP are contributing to recognize agency and voices of women and marginalized groups in local political spaces need further research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MK contributed to the conception, design, data collection, and analysis of the study. DJ reviewed and provided conceptual comments for the draft and edited the manuscript after restructuring the paper in the final version. GS and LU supported in data collection and analysis in the draft manuscripts. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The Water for Women Fund, grant agreement WRA094, a key initiative of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) as part of Australia's Aid Programme funded the research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank SNV Nepal, Everest Club (Dailekh) and Bagmati Welfare Society (Sarlahi) for partnerships on this project. Our special thanks go to all the respondents in Chandranagar RM in Sarlahi and Gurans RM in Dailekh and elsewhere for their time, engagement and insights. Tina Wallace reviewed a draft manuscript and provided editing support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^We defined the marginalized groups in this paper as individuals or groups who are economically poor and socially marginalized due to their caste, ethnicity, class and other identities. They include the poor, Dalits, people living with disability and indigenous ethnic groups.

2. ^A ward is the lowest administrative unit of a local government and is the closest government entity to the people in the federal structure. The ward committee consists of five-elected representative and civil servants for day-to day political and administrative functions. There are 6,753 wards in the total 753 local governments under the federal system.

3. ^In the federal system, formal power of making laws, policies, plans, budgeting, planning and monitoring has been shared to local government in order to strengthen localism and development (Chaudhary, 2019).

4. ^Khas Arya and Janajatis comprise Hindu caste groups and indigenous nationalities respectively. Nepal has over 125 caste and ethnic groups with diverse socio-economic status. Dalits are economically poor and socially discriminated because of caste and class relations. Indigenous nationalities (or Janajatis) such as Magars or Tharus also are considered as marginalized groups on socio-economic and political fronts compared to Khas Arya. Khas Arya groups belong to Indo Aryan origin and Janajatis come from Tibeto-Burman groups.

References

Acharya, K., and Scott, J. (2021). A study of the capabilities and limitations of local governments in providing community services in Nepal. Ublic Administr. Policy 25, 1727–2645. doi: 10.1108/PAP-01-2022-0006

Acharya, K. P. (2018). The capacity of local governments in Nepal: from government to governance and governability? Asia Pacific J. Public Administrat. 40, 186–197. doi: 10.1080/23276665.2018.1525842

ADB (Asian Development Bank) DFID (Department for International Development), and World Bank. (2012). Gender and Social Exclusion Assessment 2011: Sectoral series: Monograph. Water Supply and Sanitation, Nepal. Nepal: ADB; DFID; World Bank.

Bedford, K., and Rai, M. S. (2013). Feminists Theorize International Political Economy. E-International Relation. Available online at: https://www.e-ir.info/pdf/35165 (accessed January 9, 2023).

Bista, D. B. (1991). Fatalism and Development: Nepal's Struggle for Modernization. Calcutta: Orient Longman.

CBS (Central Bureau of Statistics) (2020). Nepal: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019. Survey Findings Report November 2020. Nepal: CBS and UNICEF Nepal.

Chapagain, P., Ghimire, M. L., and Shrestha, S. (2019). Status of natural springs in the Melamchi region of the Nepal Himalayas in the context of climate change. Environ. Develop. Sustain. 21, 263–280. doi: 10.1007/s10668-017-0036-4

Chaudhary, D. (2019). The decentralisation, devolution and local governance practices in Nepal: the emerging challenges and concerns. J. Politic. Sci. 19, 43–64. doi: 10.3126/jps.v19i0.26698

Clement, F., Pradhan, P., and van Koppen, B. (2019). Understanding the non-institutionalization of a socio-technical innovation: the case of multiple use water services (MUS) in Nepal. Water Int. 44, 336. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2019.1600336

Devkota, K. L. (2020). Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers in a Federal Nepal. Working Paper 20-17, November 2020. Georgia: International Center for Public Policy, Georgia State University.

DRCN (Democracy Resource Center Nepal) (2020). The Interrelationship Between Three Levels of Governments in Nepal's Federal Structure. A Study Report. Nepal: Democracy Resource Center Nepal.

Druckza, K. (2016). Social Inclusion and Social Protection in Nepal. (PhD Thesis): Deakin University, Australia.

DWSSM (Department of Water Supply and Sewerage Management) (2019). Status Report of Water Supply and Sanitation. Nepal: DWSSM, Ministry of Water Supply.

ECN (2022). Local Level Election E-Bulletin (Sthaniya Taha Nirwachan E-bulletin). 1(43). May 26, 2022. Government of Nepal. Nepal: ECN. Available online at: https://election.gov.np/admin/public//storage/Local%20Election/%E0%A4%AC%E0%A5%81%E0%A4%B2%E0%A5%87%E0%A4%9F%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%A8/E-Bulletine%2043%20Issu%20ful.pdf (accessed March 7, 2023).

Foucault, M. (1978). The Will to Knowledge. The History of Sexuality. Volume I. Translated from the French by Robert Hurley. England: Penguin Books.

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction.

GON (2020). Bill on Water Resources (Management and Regulation), 2077 B.S. Nepal: Government of Nepal.

GON (2022). Water Supply and Sanitation Act 2079 B.S. (Nepali). Nepal: Ministry of Law, Justice and Federal Affairs, Government of Nepal.

GON (Government of Nepal) (2015). Constitution of Nepal. Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, Government of Nepal. Nepal: Law Books Management Board.

GON (Government of Nepal) (2017) Local Government Operation Act 2017. Nepal: Government of Nepal. Available online at: https://www.mofaga.gov.np/notice-file/Notices-20200210094733703.pdf (accessed November 4, 2019)..

Gonda, N. (2016). Climate change, “technology” and gender: “adapting women” to climate change with cooking stoves and water reservoirs'. Gender Technol. Develop. 20, 149–168. doi: 10.1177/0971852416639786

Gurung, Y. B., Pradhan, M., and Shakya, D. (2020). State of social inclusion in Nepal: Caste, ethnicity and gender. Evidence from Nepal social inclusion survey 2018. Kirtipur: Central Department of Anthropology. Tribhuvan University.

Hammarberg, K., Kirkman, M., and Lacey, D. S. D. (2016). Qualitative research methods: when to use them and how to judge them. Hum. Reproduct. 31, 498–501. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev334

Hillenbrand, E., Karim, N., Mohanraj, P., and Wu, D. (2015). Measuring Gender Transformative Change: A Review of Literature and Promising Practices. CARE USA. Working Paper. The USA: CARE.

IDPG (International Development Partners Group) (2017). Common Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Framework. Nepal: GESI Working Group, IDPG, Nepal.

Joseph, G., and Shrestha, A. (2022). Glaciers, rivers and springs: a water sector diagnostic of Nepal. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Joshi, D., Fawcett, B., and Mannan, F. (2011). Health, hygiene and appropriate sanitation: Experiences and perceptions of the urban poor. Environ. Urbanizat. 23, 91–111. doi: 10.1177/0956247811398602

Khadka, M. (2009). Why Does Exclusion Continue? Aid, Knowledge and Power in Nepal's Community Forestry Policy Process. Maastricht, the Netherlands: Shaker Publishing.

Khadka, M., Joshi, D., and Nicol, A. (2020). Covid-19-A Wake-up Call for Strategic and Inclusive WASH Planning and Financing in Nepal. Nepal: International Water Management Institute.

Khadka, M., Uprety, L., Shrestha, G., Minh, T. T., Nepal, S., Raut, M., et al. (2021). Understanding Barriers and Opportunities for Scaling Sustainable and Inclusive Farmer-Led Irrigation Development in Nepal. Nepal: The Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA).

Lama, A., and Buchy, M. (2002). Gender, CLASS, caste and participation: the case of community forestry in Nepal. Indian J. Gender Stud. 9, 27–41. doi: 10.1177/097152150200900102

Latour, B. (1999). “On recalling ANT,” in Actor Network Theory and After, eds J. Law, and J. Hassard (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers/The Sociological Review), 15–25.

Leder, S., Clement, F., and Karki, E. (2017). Reframing women's empowerment in water security programmes in Western Nepal. Gender Develop. 25, 235–251. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2017.1335452

Liebrand, J. (2021). Whiteness in Engineering: Tracing Technology, Masculinity, and Race in Nepal's Development. Nepal: Himal Books.

Liebrand, J., and Udas, P. B. (2017). Becoming an engineer or a lady engineer: exploring professional performance and masculinity in Nepal's department of irrigation. Eng. Stud. 9, 120–139 doi: 10.1080/19378629.2017.1345915

Ministry of Finance (2021). Development Cooperation Report, March 2021. Nepal: International Economic Cooperation Coordination Division, Ministry of Finance (MoF), Government of Nepal.

National Planning Commission (2002). Tenth Plan (2002-2007). Unoffical translation. March 2002. Nepal. National Planning Commission(NPC), His Majesty's Government.

Nepali, R. (2022). Dalit women in Nepali politics: Underrepresented, undermined, discriminated and oppressed. November 2 2022, Nepali Live Today. Available online at: https://www.nepallivetoday.com/2022/11/02/dalit-women-in-nepali-politics-underrepresented-undermined-discriminated-and-oppressed/ (accessed May 4, 2023)

Nightingale, A. J. (2005). The experts taught us all we know: professionalisation and knowledge in nepalese community forestry. Editor. Board Antipode 37, 581–604. doi: 10.1111/j.0066-4812.2005.00512.x

Nightingale, A. J. (2011). Bounding difference: intersectionality and the material production of gender, caste, class and environment in Nepal. Geoforum 42, 153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.03.004

Parpart, J. L., Rai, S. M., and Staudt, K. A. (2002). “Rethinking Em(power)ment, gender and development. an introduction,” in Rethinking Empowerment, Gender and Development in a Global and Local World, eds J. L. Parpart, S. M. Rai, and K. A. Staudt, (London: Routledge), 3–21.

Paswan, B. (2017). Data Reveals Local Elections a Disaster for Gender Equality. The Record. Available online at: https://www.recordnepal.com/data-reveals-local-elections-a-disaster-for-gender-equality (accessed October 24, 2017).

PLGSP (2021). Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) Strategy, 2021-2023. Nepal: Provincial and Local Governance Support Programme (PLGSP), Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration, Government of Nepal. Available online at: https://plgsp.gov.np/sites/default/files/2023-02/PLGSP%20Gender%20Equality%20and%20Social%20Inclusion%20%28GESI%29%20Strategy%202021%E2%80%932023.pdf (accessed June 9, 2023)

Pokharel, B., and Pradhan, M. S. (2020). State of Inclusive Governance: A Study on Participation and Representation after Federalization in Nepal. Nepal: Central Department of Anthropology, Tribhuvan University.

Pommells, M., Schuster-Wallace, C., Watt, S., and Mulawa, Z. (2018). Gender violence as a water, sanitation, and hygiene risk: uncovering violence against women and girls as it pertains to poor WaSH access. Violence Against Wom. 24, 1851–1862. doi: 10.1177/1077801218754410

Rai, J. (2019). Status and process of law-making in local governments. Reflections from two provinces. Federalism in Nepal. Volume 4. London: International Alert

Rai, N. (2020). The implementation of federalism and its impact on Nepal's renewable energy sector: A political economy analysis, 2019/2020. Nepal: Nepal Renewable Energy Program (NREP).

SDC (Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation) (2018). Swiss Cooperation Strategy, Nepal 2018-21. Bern: Federal Department of Foreign Affairs FDFA. SDC

Sharma, P. (2014). “State restructuring in Nepal: Context, rational and possibilities,” in The Federalism Debate in Nepal: Post Peace Agreement Constitution Making in Nepal Volume II, eds B. Karki and R. Edrisingh (Nepal: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)).

Sharma, P. (2020). Federalism in Nepal: Opportunities and challenges. Key note speech at the virtual International Knowledge Forum, The Netherlands Alumni Association of Nepal (NAAN). 11-12 October 2020.

Shrestha, A., Joshi, D., and Roth, D. (2020). The hydro-social dynamics of exclusion and water insecurity of Dalits in peri-urban Kathmandu Valley, Nepal: fluid yet unchanging. Contemp. South Asia 28, 320–335. doi: 10.1080/09584935.2020.1770200

Shrestha, G., and Clement, F. (2019). Unravelling gendered practices in the public water sector in Nepal. Water Policy 21, 1017–1033. doi: 10.2166/wp.2019.238

Shrestha, P., Giri, K., and Neelam, A. (2022). Gender Analysis of Nepal's Local Elections—May 2022. Centre for Gender And Politics. Available online at: https://www.cgapsouthasia.org/_files/ugd/0dea55_c5a70377a2a6436caae7a401aa770f18.pdf?index=true (accessed June 9, 2023).

Shrestha, R. (2019). Governance and Institutional Risks and Challenges in Nepal. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

SNV and CBM (2019). WASH experiences of people with disabilities. Final report (unedited). Beyond The Finish Line Formative Research, SNV Nepal and CBM Australia.

Sommer, M., Ferron, S., Cavill, S., and House, S. (2015). Violence, gender and WASH: spurring action on a complex, under-documented and sensitive topic. Environ. Urbaniz. 27, 105–116. doi: 10.1177/0956247814564528

Tamang, S. (2018). “Rules of the game”: The Leadership and Meaningful Participation of Newly-Elected Women Representatives. Nepal: Governance Facility

Thompson, J. A., Gaskin, S. J., and Agbor, M. (2017). Embodied intersections: Gender, water and sanitation in Cameroon. Agenda: Empower Wom. Gender Equity 31, 140–155. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2017.1341158

Udas, P. B., and Zwarteveen, M. Z. (2010). Can water professionals meet gender goals? a case study of the Department of Irrigation in Nepal. Gender Develop. 18, 87–97. doi: 10.1080/13552071003600075

Uehara, A. (2019). Glass ceiling in the Himalayas: In Nepal, an uphill battle for gender parity. Nepal.

Veneklasen, L., and Miller, V. (2007). A New Weave of Power, People andPolitics. The Action Guide for Advocacy and Citizen Participation. Warwickshire: Practical Action Publishing.

Water Aid (2005). Water laws in Nepal: Laws Relating to Drinking Water, Sanitation, Irrigation, Hydropower and Water Pollution. Nepal: Water AidNepal.

Water Aid (2009). Seen But Not Heard? A Review of the Effectiveness of Gender Approaches in Water and Sanitation Service Provision. Nepal: Water Aid.

Water Aid (2018). WASH Financing in Nepal 2018/19. Context SDG 6. Nepal: Water Aid. Available online at: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/sites/g/files/jkxoof256/files/2022-03/WASH%20Financing%20factsheet_2021-22_0 (accessed January 10, 2021).

Water Aid (2020). WASH financing in Nepal 2020/21. Context: WASH SDGs and COVID 19. Nepal: Water Aid.

Keywords: WASH, gender, federalism, inclusion, policy, dynamics, change unless systemic

Citation: Khadka M, Joshi D, Uprety L and Shrestha G (2023) Gender and socially inclusive WASH in Nepal: moving beyond “technical fixes”. Front. Hum. Dyn. 5:1181734. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1181734

Received: 07 March 2023; Accepted: 29 August 2023;

Published: 25 September 2023.

Edited by:

Chanda Gurung Goodrich, Independent Researcher, Kalimpong, IndiaReviewed by:

Monica Adhiambo Onyango, Boston University, United StatesAnjal Prakash, Indian School of Business, India

Copyright © 2023 Khadka, Joshi, Uprety and Shrestha. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Manohara Khadka, bS5raGFka2FAY2dpYXIub3Jn

Manohara Khadka

Manohara Khadka Deepa Joshi2

Deepa Joshi2 Labisha Uprety

Labisha Uprety Gitta Shrestha

Gitta Shrestha