- 1World Maritime University, Malmö, Sweden

- 2International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 3DTU Aqua National Institute of Aquatic Resources, Technical University of Denmark (DTU), Lyngby, Denmark

- 4Fisheries Management, Thünen Institute of Baltic Sea Fisheries, Rostock, Germany

- 5School of Public Administration, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

- 6Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies, Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi, Corpus Christi, TX, United States

- 7Marine Institute, Galway, Ireland

- 8Ocean Governance, Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam, Germany

- 9National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Woods Hole, MA, United States

Ecosystem-based management (EBM) necessarily requires a degree of coordination across countries that share ocean ecosystems, and among national agencies and departments that have responsibilities relating to ocean health and marine resource utilization. This requires political direction, legal input, stakeholder consultation and engagement, and complex negotiations. Currently there is a common perception that within and across national jurisdictions there is excessive legislative complexity, a relatively low level of policy coherence or alignment with regards to ocean and coastal EBM, and that more aligned legislation is needed to accelerate EBM adoption. Our Atlantic Ocean Research Alliance (AORA) task group was comprised of a small, focused and interdisciplinary mix of lawyers, social scientists, and natural scientists from Canada, the USA, and the EU. We characterized, compared, and synthesized the mandates that govern marine activities and ocean stressors relative to facilitating EBM in national and international waters of the North Atlantic, and identified formal mandates across jurisdictions and, where possible, policy and other non-regulatory mandates. We found that irrespective of the detailed requirements of legislation or policy across AORA jurisdictions, or the efficacy of their actual implementation, most of the major ocean pressures and uses posing threats to ocean sustainability have some form of coverage by national or regional legislation. The coverage is, in fact, rather comprehensive. Still, numerous impediments to effective EBM implementation arise, potentially relating to the lack of integration between agencies and departments, a lack of adequate policy alignment, and a variety of other socio-political factors. We note with concern that if challenges regarding EBM implementation exist in the North Atlantic, we can expect that in less developed regions where financial and governance capacity may be lower, that implementation of EBM could be even more challenging.

Introduction

Ecosystem-based management (EBM) is predicated on using the natural ecosystem boundaries as a framework rather than being confined by political or administrative boundaries (Slocombe, 1993). In a marine context, EBM emphasizes the maintenance or enhancement of ecological structure and function, and the benefits that healthy oceans provide to society (Link and Browman, 2017). EBM necessarily requires a degree of coordination across countries that share ocean ecosystems, and among national agencies and departments that have responsibilities relating to ocean health and marine resource utilization. If conceived and implemented effectively, EBM may facilitate systematic, holistic perspectives on ocean management. As such, EBM has garnered substantial national and international interest among governments and agencies responsible for the sustainable utilization and management of ocean and coastal resources (ORAP, 2013; NMFS, 2016; AORA, 2017; European Parliament, 2018).

Despite its promise, there are a number of concerns that the pace of adopting and implementing EBM is insufficient (Arkema et al., 2006; Leslie and McLeod, 2007; Link and Browman, 2017), particularly in the face of accelerating environmental change (e.g., Hoegh-Guldberg and Bruno, 2010; Barange et al., 2018), technological advance (e.g., Sutherland et al., 2017), and the emerging importance internationally of the “blue growth” agenda (Visbeck et al., 2014). EBM requires coordination among jurisdictions and agencies that share ocean-related authority but which may hold very different priorities and values. This requires political direction, legal input, stakeholder consultation and engagement, and complex negotiations. The transaction costs of designing and successfully implementing EBM are likely high because governance and management mechanisms at the appropriate geographic scale take time and effort to establish and implement. Even though the long-term EBM benefits may well more than compensate for initial investments, responsible authorities may be reticent to fully invest and support EBM implementation unless they are sure that EBM is “worth the effort.” Two questions thus arise: do we have capable legal systems mandated to support cross-jurisdictional EBM; and do we have the political will and institutional and technical capacity to take the necessary efforts and investments to implement EBM?

Currently there is a common perception that within and across national jurisdictions there is excessive legislative complexity (Boyes and Elliott, 2014; Raakjaer et al., 2014; Boyes et al., 2016), a relatively low level of policy coherence or alignment with regards to ocean and coastal EBM, and that more aligned legislation is needed to accelerate EBM adoption and help maintain healthy oceans (Ramírez-Monsalve et al., 2016; Marshak et al., 2017). Other research has highlighted weak implementation of EBM (Arkema et al., 2006; Fluharty, 2012; Salomon and Dross, 2013; Link and Browman, 2014, 2017; van Tatenhove et al., 2014; Marshak et al., 2017) but, to date, there has been relatively little research focus on the legal and policy mandates needed to support effective EBM [but see (Boyes et al., 2016)], and how those might affect EBM implementation.

The Atlantic Ocean Research Alliance (AORA) between Canada, the EU, and the USA was launched by the signatories of the Galway Statement on Atlantic Ocean Cooperation in May 2013 (www.atlanticresource.org/aora). The AORA intends to advance the shared vision of a healthy Atlantic Ocean that promotes the well-being, prosperity, and security of the present and future generations. One of the four priority cooperation areas is on the ecosystem approach to ocean health and stressors. AORA with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations led an EBM scoping workshop in 2016, which concluded that understanding the impediments to implementation of EBM is imperative (AORA, 2017). Considering the common understanding of the potential benefits from a coordinated, effective EBM approach at the national and international level but given apparent ineffective implementation to date, an important question arises as to what role mandates play in the implementation of EBM within and across jurisdictions of Canada, the EU, and the US. By mandates we mean, in their broadest sense, an authorization to act in a particular way on a public issue. This may include legally binding obligations as well as so-called soft law agreements, principles and declarations that are not necessarily legally binding. Insights from the AORA regions, which have relatively high technical, financial and political capacity, could provide important insights for the broader global EBM community.

In this paper, we report findings from our AORA task group which is considering mandates and ocean governance. The mandates task group was asked to characterize relevant mandates and governance structures, relate them to one another, compare across jurisdictions, and identify those features that facilitate or hinder the ecosystem approach. Our task group, comprised of a small, focused and interdisciplinary mix of lawyers, social scientists, and natural scientists from across the three AORA jurisdictions, in March 2018 met in London for a 4-day workshop. Our goal was to characterize, compare, and synthesize the mandates that govern marine activities and ocean stressors relative to facilitating EBM in national and international waters of the North Atlantic. Specifically, we sought to compare the mandates across jurisdictions, identify policy and other non-regulatory mandates where possible, and to assess whether the lack of mandates was a likely constraint to EBM in the AORA jurisdictions.

Methods

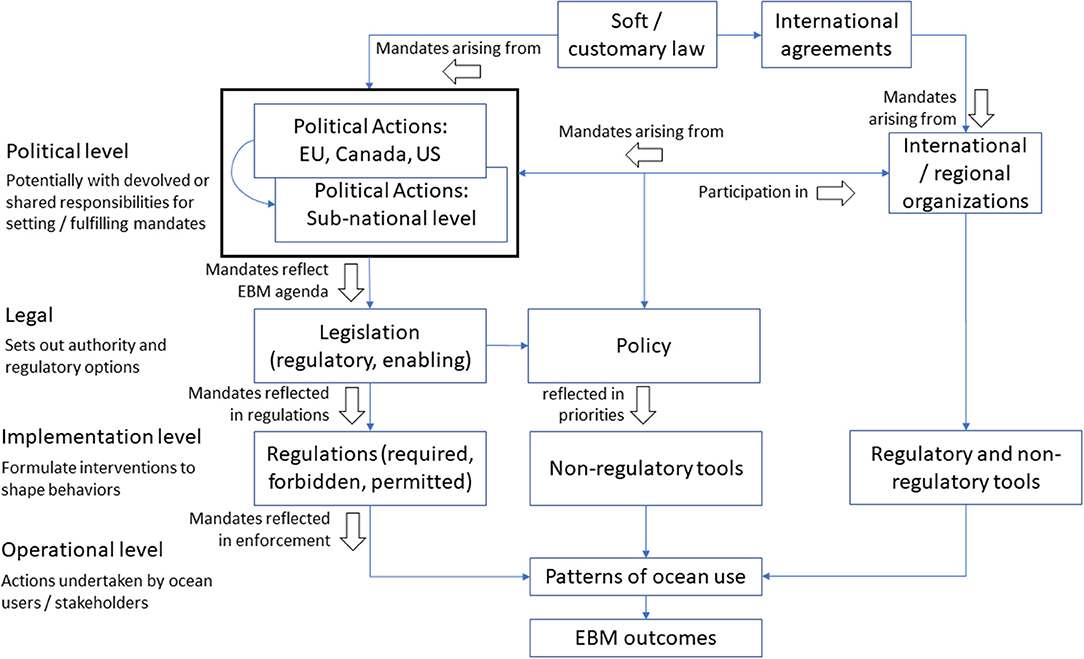

Understanding the potential for EBM to achieve ecological, social, and economic goals requires improved understanding of how governments establish and implement EBM. To organize our analysis, we propose a multi-level approach (Figure 1), reflecting political mandate, legislative structure, and non-regulatory implementing policy. We drew on the multi-level Institutional Analysis and Development framework (Rudd, 2004; Ostrom, 2005) to create the framework that helps conceptualize the mandates themselves and the degree to which there is commitment to implement them.

Figure 1. The conceptual multi-level approach used by the task group depicting political mandate, legislative structure, and non-regulatory implementing policy (adapted from Link et al., 2018).

Preliminary research prior to convening the workshop (AORA, 2017) outlined a range of legislation and agreements in Canada, the EU, the US, and internationally. We re-examined and refined these, focusing on how specific Acts or Agreements referenced particular ocean stressors and human activities. While not comprehensive, this information was used to structure workshop discussion regarding mandate coverage. Other non-regulatory mandates (e.g., executive directives, spending guidelines, policy statements, etc.) also exist, so the legislation list may not convey fully all the prescribed mandates or ocean management priorities within a jurisdiction. We also did not explicitly develop a list of national European legislation, or State- and Province-level legislation in North America, a task that would add greatly to the complexity of the exercise.

To structure the workshop discussion, we used a slightly adapted list of 20 EBM principles that were based on those of the Convention on Biological Diversity (www.cbd.int/ecosystem/principles.shtml) and the FAO Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries (Garcia et al., 2003). During the workshop, we solicited opinions from among participants familiar with each jurisdiction as to provide a judgement as to whether these principles were being practically implemented. The international area beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) component was viewed as too wide-reaching and with contrasting elements (e.g., seabed vs. water column; treaty vs. customary law) so as to give any meaningful judgement as to the implementation status for many of the principles; such an analysis could be better executed in the future using formal expert judgement interviews or reviews.

In addition to legislation that largely focuses on formal rules and regulatory action to implement EBM, there are informal enabling or non-regulatory policy tools that can be used. These can be inferred through the strength of discourse surrounding EBM, the discretionary scope of legislation or regulations, and the resources dedicated to achieving EBM goals. Non-regulatory policies and priorities can be used alone or in conjunction with formal rules to help move jurisdictions toward desired EBM outcomes, thus there are opportunities to strategically combine different types of interventions and investments to achieve synergies in protecting or re-generating benefits from healthy ocean ecosystems.

Results

Legislation across jurisdictions (Canada, EU, US) differs to some extent with respect to how EBM is defined and the specific processes and standards that it involves. There are also differences regarding implementation and enforcement mechanisms across jurisdictions, as well as in the flexibility that authorized agencies and departments have to use specific types of rules or non-regulatory policy tools to achieve EBM goals.

Mandates With Respect to Elements of EBM

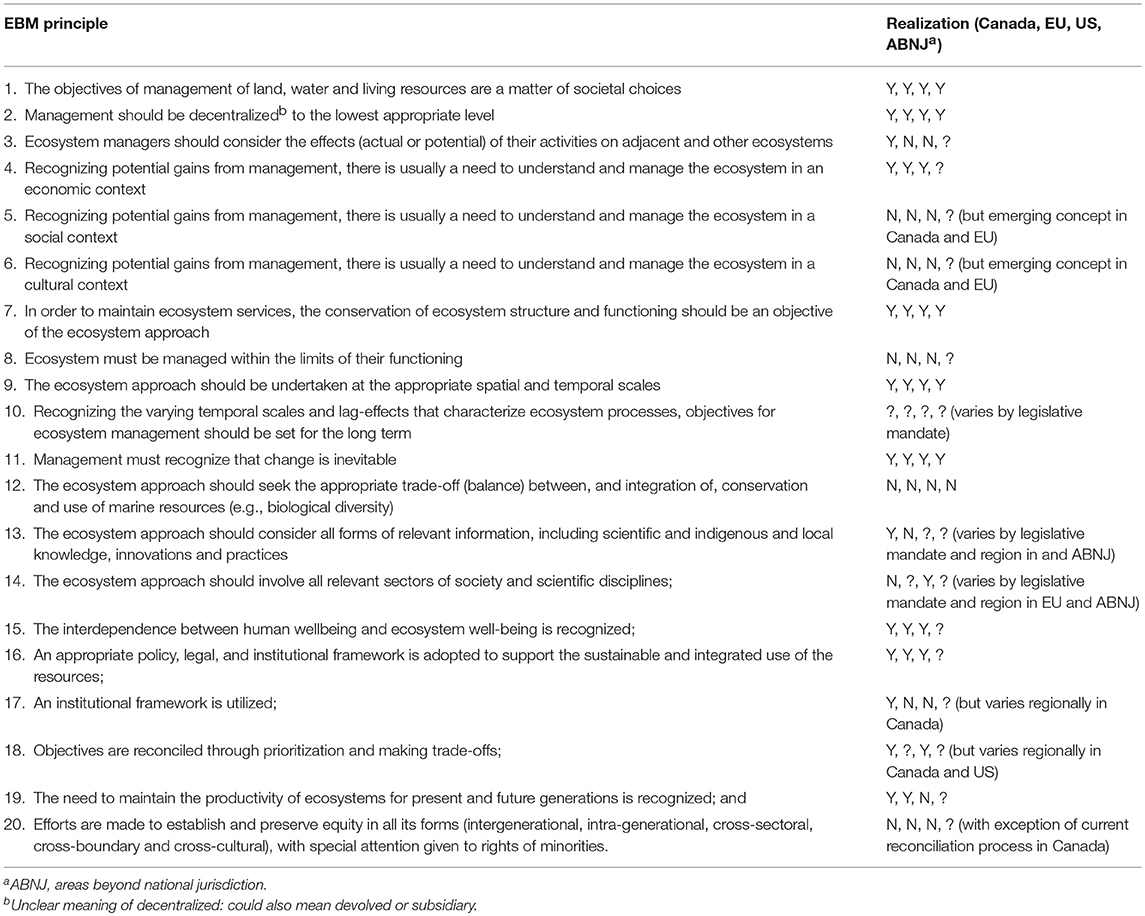

Our opinions, based on discussion within the expert task group at the London workshop (Table 1), were that a 40% (8 out of 20) of EBM principles were being realized in most jurisdictions. This occurred for all four jurisdictions for five principles (principles 1, 2, 7, 9, 11), and three principles (principles 4, 15, 16) were largely being realized in Canada, the EU, and the US (the situation varied too much internationally to make a meaningful characterization).

Table 1. Principles considered in comparing and contrasting EBM implementation across jurisdictions, and expert opinion on realization level (for each jurisdiction in order, Y, yes; N, no; ?, uncertain).

There was also consensus that five EBM principles were not being met, reflecting social and cultural considerations (principles 5, 6, 20), or ecosystem limitations (principle 8). There was also agreement that there were shortcomings across all jurisdictions with regards to the principle that emphasized that EBM should seek the appropriate balance between, and integration of, conservation and use of marine resources (principle 12). One principle (10) relating to lagged effects was recognized as too uncertain to make a definitive conclusion either way. The remaining eight principles were perceived to be realized in some jurisdictions but not others. The general message arising from Table 1 is that the need for EBM is recognized and that economic and ecological consequences are viewed as relatively more consequential across jurisdictions as compared to social and culture principles of EBM.

Mandates Arising From Legislation and Policy

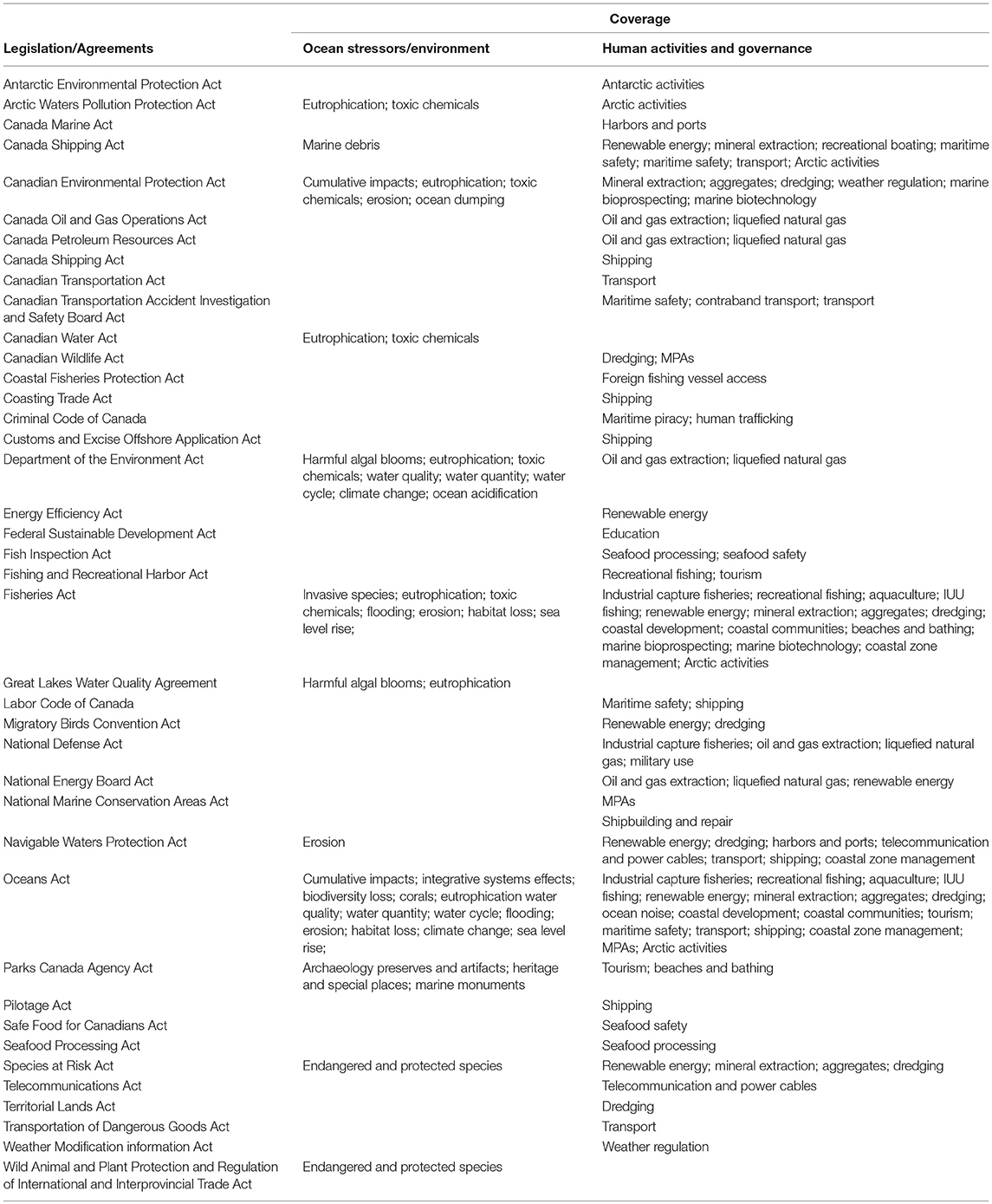

Canada

Canada has long term commitment to EBM through its Oceans Act, a federal statute that establishes broad principles by which Canada will manage its ocean territories. The Oceans Act prescribes that an ecosystem approach be applied in the protection and preservation of the marine environment, and for the conservation and protection of biodiversity. Implementation of EBM has been largely conducted on a regional basis through integrated planning processes and has been supported by a number of initiatives such as the 2007 launch of the Ecosystem Research Initiatives. As in other jurisdictions, there is some overlap in the implementation of EBM with other tools such as marine spatial planning and/or coastal zone management. Table 2 summarizes a selection of legislation that is particularly relevant for EBM in Canada. General information on Canadian legislation is available from the Department of Justice (laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/) and summaries of environmental legislation are available from Environment Canada (https://www.ec.gc.ca/?lang=en) and WWF Canada (2013).

Canada also has a variety of sectoral strategies (e.g., Canadian Biodiversity Strategy, Ocean Protection Plan) that address ocean-relevant pressures and activities, as well as explicit mandate letters (pm.gc.ca/eng/mandate-letters) that specify the legislative and policy priorities for various Departments with direct or indirect responsibilities for ocean management. New to the approach outlined in the mandate letter is the increased reliance on horizontal and coordinated action between departments.

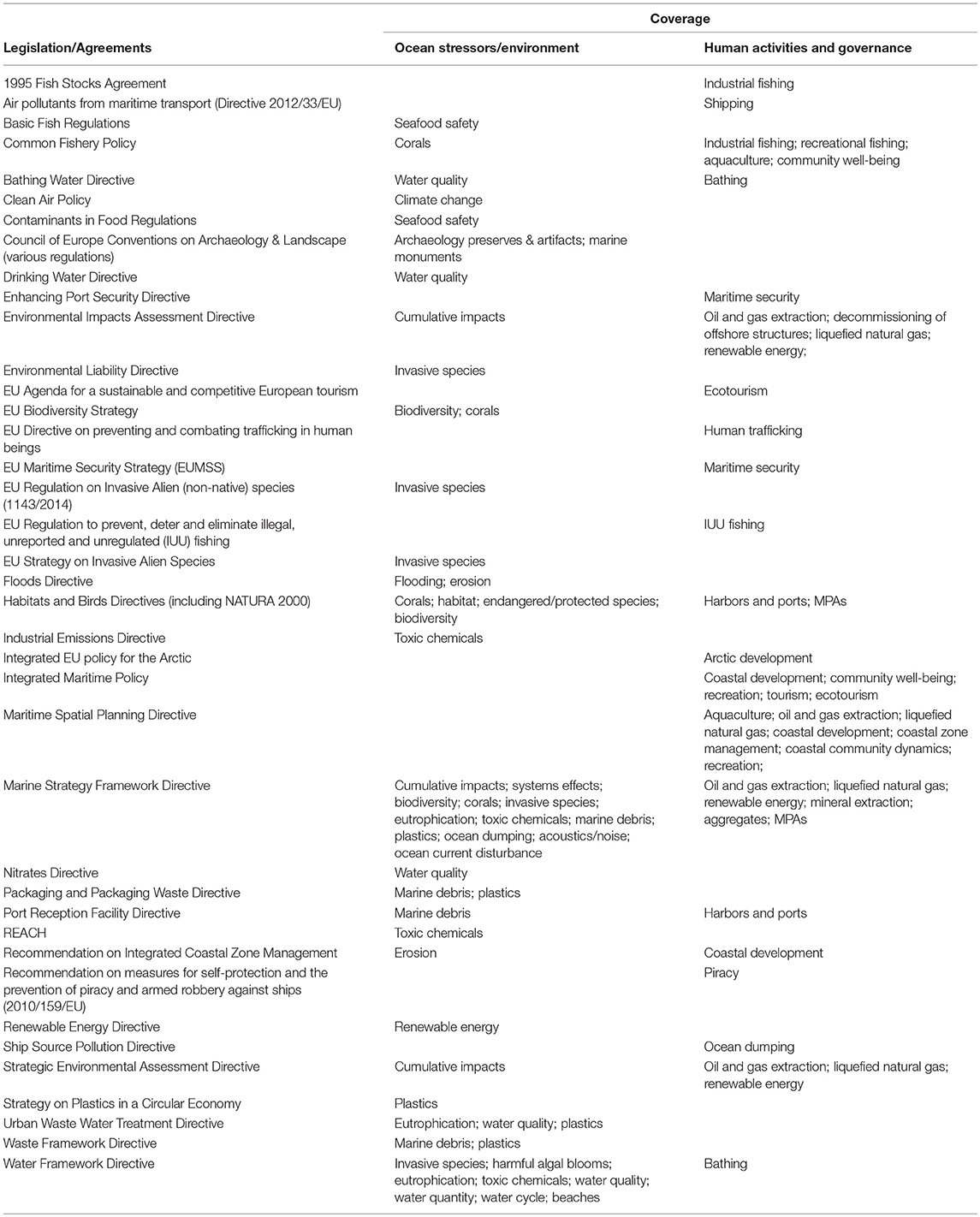

EU

The EU's Integrated Maritime Policy (IMP) seeks to provide an overarching framework (ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/policy_en) for coherent approaches to maritime issues and coordination between different policy areas that encompass a variety of legislation (Table 3). It addresses key aspects and instruments for a more holistic approach to maritime governance such as an agenda coordinating economic activities (i.e., “blue growth” strategies), marine data and integrated surveillance, or sea basins strategies. However, as the umbrella instrument for overall coordination of maritime activities across different Directorate Generals and different coastal nations, the IMP is relatively weak in legal and financial (lacking an adequate funding mechanism) terms when compared with the sectoral policies which it is supposed to integrate (Fritz and Hanus, 2015).

The Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) provides the environmental pillar to sectoral EU maritime policies and is unique (in terms of EU marine legislation) in having an ecosystem-based approach (van Tatenhove et al., 2014; Bigagli, 2015). Under the MSFD, each member state has to develop a marine strategy in order to contribute to the achievement of Good Environmental Status (GES) by 2020, specified through 11 descriptors. While developing such marine strategies, member states are required to cooperate, preferably through regional seas conventions (e.g., OSPAR, HELCOM) (van Leeuwen et al., 2014).

Marine spatial planning (MSP) is considered a central instrument for the implementation of the IMP and for implementing EBM (Schaefer and Barale, 2011; Bigagli, 2015). MSP was added to the EU's portfolio through the 2014 Maritime Spatial Planning Directive (Directive 2014/89/EU). The Directive introduces minimum requirements which EU member states have to fulfill in their MSP activities. While the main objective of the Directive is to “support sustainable development and growth in the maritime sector” [Art. 5(1)], a reference to the promotion of GES in Article 5 of the directive was removed during the legislative process (Jones et al., 2016).

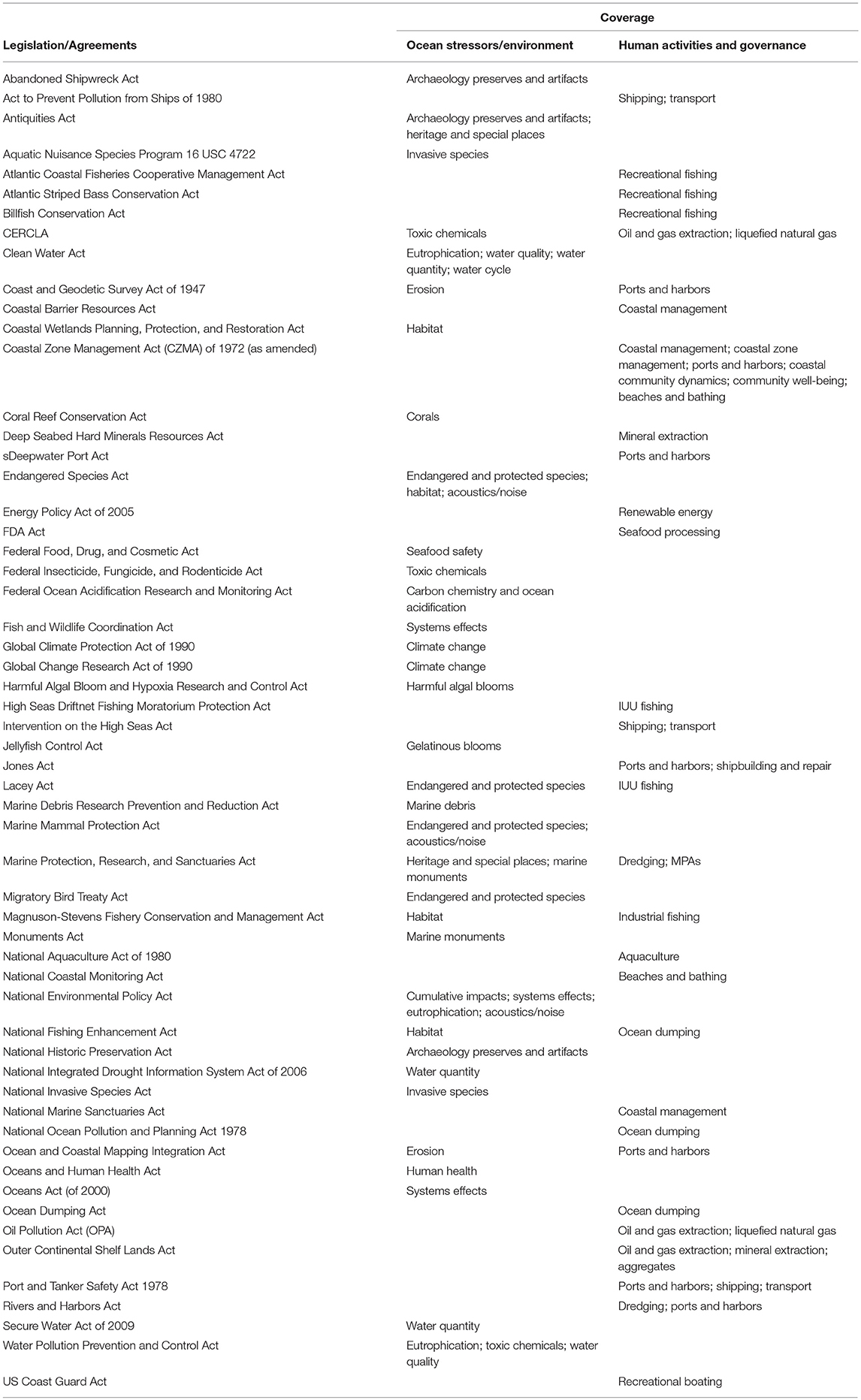

USA

In the US there is no comprehensive ocean legislation that mandates the application of EBM across ocean sectors but many individual pieces of legislation (Table 4) have potential relevance for EBM. Often the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) has been used to authorize and execute major facets of EBM. NEPA requires federal agencies to incorporate environmental considerations in their planning and decision-making through a systematic interdisciplinary approach. Specifically, all federal agencies are to prepare detailed statements assessing the environmental impact of and alternatives to major federal actions significantly affecting the environment. In practice, NEPA is used to examine a range of activities that impact parts of the ocean, but typically focuses on only one ocean-use sector. Recommendations by the National Commission on Ocean Policy, created under the auspices of the Oceans Act of 2000, established a strong framework for the implementation of EBM in U.S federal waters (National Ocean Council, 2013). This was further codified by an executive order formalizing the National Ocean Policy (Executive Order 2010) that called for “… a comprehensive, integrated ecosystem-based approach that addresses conservation, economic activity, user conflict, and sustainable use of ocean, coastal, and Great Lakes resources…” Yet relatively few EBM-related recommendations were put into practice by most federal agencies with ocean management regulatory authority (Craig, 2015).

In practice the focus of the National Ocean Policy was primarily on voluntary regional ocean planning with no specifically enforceable rights for the participating states and others (Christie, 2015). Two federally coordinated regional ocean plans were completed: the Northeast Ocean Plan; and the Mid-Atlantic Regional Ocean Action Plan (Duff, 2017). In these plans, the federal government's role was not to mandate EBM, but to encourage voluntary partnerships by providing information and funding for local/regional pilot projects (Craig, 2015). A recent Executive Order (Executive Order 2018) superseded the National Ocean Policy, emphasizing much more of a coordinating role for the federal government, stressing economic development in coastal and ocean areas, and not explicitly mentioning EBM.

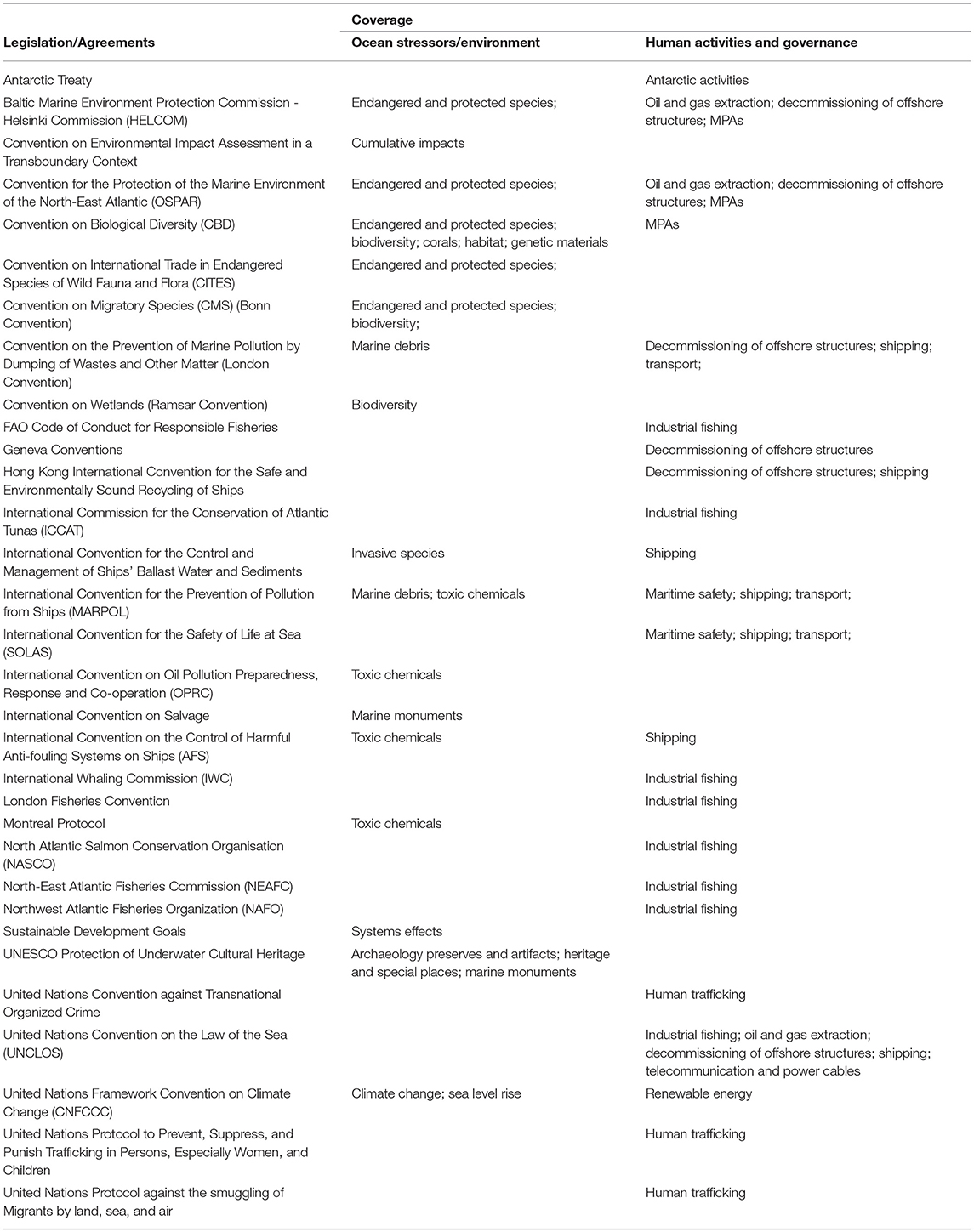

Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ)

In the ABNJ a number of ocean pressures and activities are covered by international agreements (Table 5). Environmentally-oriented agreements of potential relevance for EBM are summarized by the CBD (www.cbd.int/brc/) and the IMO provides a comprehensive list of shipping-related conventions (www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/ListOfConventions/Pages/Default.aspx).

International law on the management of resources in the ABNJ has developed on an ad hoc basis with minimal coordination or assurance that activities will be undertaken based on best scientific information. Some principles and obligations have been generally recognized as applying to all areas of the globe including the ABNJ. In 1987, The World Commission on Environmental and Development (WCED, 1987) approved 22 articles of legal principles including, for example: requiring nations to use transboundary natural resources in a reasonable manner; taking precautionary measures to limit risk and to establish strict liability for harm done; providing prior notification and assessment of activities having significant transboundary effects; and applying, as a minimum, the same standards for environmental conduct and impacts concerning transboundary resources as are applied domestically.

These legal principles are often discussed and used to guide national behavior in ocean areas. Many of them have become codified in international agreements, while others have come to reflect customary international law (Birnie et al., 2009). OSPAR is leading efforts in the Northeast Atlantic to designate a network of MPAs in ABNJ, which include working with competent international authorities to develop management measures for the sites (O'Leary et al., 2012). Negotiations are also moving forward on an international binding instrument, under the UNCLOS, on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of ABNJ.

These and similar efforts reflect a growing willingness by the international community to seek to manage ABNJ in a more coordinated and ecosystem-based fashion. Determining whether aspects of EBM are occurring in the ABNJ depends, however, on an interpretation of specific articles in existing international agreements as well as an analysis of relevant customary legal norms and soft law principles.

Discussion

In our view, the regulatory mandates across AORA jurisdictions reflect sufficient legal authority to engage in effective EBM. Language supporting an EBM approach has been incorporated into many legislative and policy instruments in all three jurisdictions. Yet in practice, EBM has seen limited implementation across all jurisdictions despite the apparently ample legal tool box. There are numerous potential explanations as to why this is still the case.

Mandates and Government Organization

Mandates and Policy Coherence

There are some gaps in legislative coverage for some ocean uses and pressures. For instance, some of the more recent technological developments seen in fields like marine biotechnology and bioprospecting do not have many, if any, clear legislative coverage across these jurisdictions. Sea level rise is another important issue lacking directly associated legislation at the national or regional level.

Next to legislative gaps, there are obvious instances of vertical and horizontal as well as external and internal incoherences at the level of policy objectives, instruments, and implementation (cf. Nilsson et al., 2012). They hamper or prevent the achievement of EBM. Put differently, the maximization of all maritime uses at large is impossible, though creating synergies between uses on the ground, minimizing their trade-offs, and searching for compensatory measures represent central challenges for EBM decision-makers and managers. The question of how coherence is addressed in maritime governance processes is closely linked to the capacities of actors (sectors, maritime users, see Imbalances in Capabilities Across Sectors), the existence and use of coordination mechanisms (see Interdepartmental and Agency Coordination), and the (re)-distributive dimension of EBM legislation (see Economic Costs and Benefits Arising From Implementing EBM).

Objectives and instruments governing marine resource utilization and marine resource protection in the three jurisdictions may not be well-aligned and can even be in direct conflict (external incoherence): e.g., exploiting fisheries vs. protecting biodiversity; port growth vs. increasing tourism opportunities; shipping efficiency vs. controlling pollutants from high Sulfur fuels. US management of ocean activities, for example, has an assortment of different and specific legislation, directives, and regulations targeting individual activities such as fisheries, hydrocarbon extraction, or habitat protection. This makes it difficult to implement EBM effectively across sectors and agencies (horizontal/external coherence) (Arkema et al., 2006; Link and Browman, 2017; Marshak et al., 2017).

In the EU, a lack of objectives which are valid for all maritime sectors prevents a more coherent mandate structure (horizontal/external coherence). The MSFD is characterized by relatively weak and uncoordinated implementation in the member states, creating asymmetries in fisheries regulation and enforcement among EU members (vertical/external coherence) (van Hoof et al., 2012; Salomon and Dross, 2013; Raakjaer et al., 2014). MSP acts as the key cross-sectoral tool to achieve integrated maritime policy but has also so far not been used effectively by member states to integrate objectives originating from different maritime sectors (as an example of incoherences at the level of instruments and implementation) (Jones et al., 2016). The EU's Common Fisheries Policy further provides examples of internal incoherences at the level of policy objectives and instruments: The Basic Regulation (European Parliament and European Council, 2013) sets out the basic objectives of achieving MSY and at the same time creating economic and employment benefits (Art. 2.2 and 2.5.c). Contradictory fisheries subsidies provide examples of an internal consistency at the level of instruments (cf. Belschner et al., 2018).

We do, however, recognize that many of the perceived gaps in legislative coverage may in fact be covered directly by overarching laws or policies and that some single-sector mandates (e.g., NMFS, 2016) have the ability to contribute to EBM objectives. All jurisdictions have some sector-specific legislation that considers ocean activities and pressures relevant to cumulative impacts, even if specific coverage on the effects of multiple stressors is not a primary focus those pieces of relevant legislation. Additionally, all jurisdictions have a mandate, or at least non-legislative policy, to consider ocean governance and management in an integrative and systemic manner. Enabling policy and instrumental coherence across governance levels, between and within sectors, as well as across jurisdictions is inherent to EBM and may present an even larger challenge than addressing legislative gaps.

Conflicting Interpretations of Laws and Mandates

EBM implementation may be impeded due to conflicting interpretations of laws or regulations. For example, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in the United States has traditionally been interpreted to require that federal agencies ensure that their actions are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any listed species or adversely modify their critical habitat (Goble et al., 2006). This interpretation, which narrowly focuses on the health of one species, is increasingly being criticized in favor of broader EBM approaches to fulfill the mandates of the ESA. Under the evolving interpretation, if the best scientific evidence shows an EBM approach would better protect and enhance the biological requirements of listed species, agencies should have the authority to employ that method of recovery. This interpretation has not, however, been fully tested in the courts and it is still legally unclear whether EBM may be used as a recovery strategy under the ESA.

All jurisdictions have iterative and interactive processes between policy-makers who create legislation and the courts who interpret legislation and provide guidance on acceptable behaviors and sanctions. This is a long-term and expensive process, part of the high transaction costs of successfully designing and implementing EBM.

Interdepartmental and Agency Coordination

EBM requires significant coordination efforts by lead departments, within and across departments, and any conflicts that arise over jurisdictional authority and competition between administrative units can act as barriers to EBM implementation. Departments and agencies may have competing agendas and mandates, as well as different administrative cultures or institutional norms. Some departments may use highly technical analyses based on quantified data (e.g., fisheries science—Sainsbury et al., 2000) whereas others may rely heavily on indicators (e.g., ecosystem health assessments—Halpern et al., 2012) and associated narratives. There may also be a lack of adequate mechanisms and incentives to support integrated or coordinated approaches necessary for EBM, although routine horizontal integration techniques do exist within Canada, EU, and US governments (e.g., inter-departmental committees at relatively senior levels, regional associations of governors, etc.). In the EU, a high-level of integration was achieved through the creation of the European Commission's Directorate General (DG) MARE in 2008 as successor of DG FISH (i.e., Common Fisheries Policy), to include and reflect responsibilities for the EU's IMP (adopted in 2007) and through the combination of the competences for DG MARE and DG ENV (the commissioner for DG MARE is also in charge of DG ENV, environment). Both happened in response to the introduction of the EBM approach (EC, 2008) and according policy frameworks (IMP and MSFD), while at the same time “the Commission's interpretation of the concept and the definition of its potential instrumental effect largely remained unclear (Wenzel, 2018 p.159).”

Bureaucratic Incentives

Within bureaucracies, potential impediments to EBM implementation can arise due to a variety of staffing issues. Managing EBM initiatives requires a relatively in-depth understanding of issues that cut across the natural and social sciences, as well as of the stakeholders and other departments engaged by EBM initiatives. From one management perspective, EBM would benefit from having subject specialists in managerial roles. In environments with high levels of unplanned staff turnover, there can be challenges in maintaining the human capacity, institutional memory, and social networks needed to evaluate and manage EBM issues. Another perspective held by many governments (e.g., Canada) is that senior managers should be generalists who can rapidly assimilate information on complex topics, draw on broad knowledge of management methods and their social networks, and capably manage complex processes such as the design and implementation of EBM.

Either way, career incentives may influence individuals' enthusiasm for engaging in EBM. If it is perceived as being an area with limited potential for “making a mark,” it may be the case that individuals on a fast track to upper-level managerial positions could seek to avoid working in EBM. Conversely, if EBM was viewed as an area for a young professional to engage in policy innovation and develop valuable new skills and networks, departments involved in EBM could be viewed as attractive career-building stops. The potential effects on EBM engagement on incentives and reward systems for bureaucrats is not well-understood.

Operational Challenges

Stakeholder Involvement

Engagement, dialogue, and co-creation of evidence is a key part of effective EBM implementation, requiring adoption of best practices among participants in relation to stakeholder engagement and interaction. Poor stakeholder engagement can be as destructive to the legitimacy of EBM processes and trust relationships as a total absence of stakeholder engagement (Kearney et al., 2007; Linke and Jentoft, 2016). In Europe, Advisory Councils (regional stakeholder bodies set up under the Common Fisheries Policy) report that the work load for their members has exponentially increased as more projects, institutions, and bodies call on their participation as formal stakeholders (Aanesen et al., 2014). This may result in a dilution of attention and growing resentment toward events that use poor stakeholder engagement practices and lead to increasing reluctance to accept invitations to engage in new initiatives.

From a government perspective, EBM requires increased levels of coordination from lead departments with sectoral representations as well as other actors. Such outreach processes are not only determined by time and resource constraints, but also the strategic agendas of lead departments or agencies. It is important to be cognizant that governments can use stakeholder engagement implicitly as a tool to download management costs on stakeholder groups (Wiber et al., 2010).

Transdisciplinary Skill Sets

It is now well-recognized that complex environmental challenges require transdisciplinary problem solving. Transdisciplinary approaches for mission-oriented problem solving requires the development among problem solvers of a shared understanding of concepts, language, and intervention options (Pennington et al., 2013). Business, NGO, government, and academic participants in EBM all come to the process with different backgrounds, rhetoric, and mental models. Solving complex challenges requires significant investment in the process of dialogue and relationship building (Hickey et al., 2013). The value-added of EBM relative to traditional management approaches arises from holistic consideration of the ecosystem and the opportunities that rely on its health, but it does take sustained time, effort, and investment to ensure that the benefits of transdisciplinary approaches are realized (Lawton and Rudd, 2013).

Imbalances in Capabilities Across Sectors

EBM is an approach to ocean management that is predicated on taking a whole-of-ecosystem viewpoint. Within an ecosystem, there are many diverse interests that can vary regarding their capabilities to engage in the EBM process. Capabilities are all types of resources that allow actors to influence an outcome. For instance, they can be financial- or staff-related resources, but may also be related to staff assertiveness or access to information (Scharpf, 1997). For example, oil and gas companies have considerable resources to invest in the scientific research needed to support the decision-making process around EBM. Regulatory agencies, smaller industries, or coastal resource users and communities may lack the resources and capacity for production of credible scientific evidence to bolster their positions.

Context-related institutions (e.g., The Role of Governments in Governance, Bureaucratic Incentives) define how actors can make use of their resources in EBM processes. Formal and informal rules prescribe the coordination between competent ministries or rules define access of stakeholders to the decision-making processes (see Stakeholder Involvement). Together with actor-specific resources, procedural rules indirectly shape the substance of EBM legislation as well as their implementation. They also affect the quality and legitimacy of EBM decision-making processes (e.g., Sander, 2018).

In addition, EBM processes are often lengthy and require considerable commitment in terms of participation and engagement. Again, larger industries are often better placed to persist through the EBM process whereas stakeholders from small organizations or industries (e.g., small-scale fisheries) may not have the resources to dedicate to the EBM process on an ongoing basis, thus limiting their ability to participate and be represented in the outcomes of the EBM process.

Crises Swamp Longer-Term Policy Priorities

EBM requires a long term and persistent commitment for its successful implementation. However, the focus of decision-makers and financial resources can be diverted from the implementation agenda when emerging issues become suddenly salient to policy-makers. For EBM practitioners, a critical factor is to recognize the unpredictability of decision-making and of long-term political support for their activities (Cohen et al., 1972), highlighting the temporal dimension for EBM implementation.

Kingdon's (1984) conception of windows of opportunity may offer possibilities for transitions toward an EBM-oriented maritime governance. This requires policy entrepreneurs such as politicians or leaders of interest groups to put enhanced EBM implementation on the political agenda through coalition building or strategic framing of EBM issues (e.g., Meijerink and Huitema, 2010). Policy entrepreneurs link problem perception (key actors perceive current maritime governance as sub-optimal for tackling the challenges entailed), policy communities (specialists continuously working on EBM “solutions” which can be offered when the “time is right”) and politics (decision-makers sensing an appetite for policy change within government parties and coalitions or wider society (Zahariadis, 1995). Turnover in political staff as a consequence of elections can facilitate political and attitudinal change. The 2019 elections to the European Parliament could, for instance, represent such a turning point if populist-nationalist parties or environmentally-oriented parties experience increased levels of success.

Crises can also lead key actors to dedicate resources to awareness-building surrounding particular positions on a crisis issue. Public and political awareness may, however, also be used by interest groups or policy entrepreneurs as opportunities for advancing particular policy reforms; EBM may suffer if proponents do not have, relative to other parties, strongly formulated and effectively communicated positions. For example, after Hurricane Katrina ecological economists made a case for increased investment in coastal protection by reconstructing wetlands but that was largely trumped, on economic grounds, by others with even stronger arguments supporting increased emphasis on traditional coastal protection infrastructure (Farley et al., 2007).

Political Challenges in Implementing EBM

The Role of Governments in Governance

There are some fundamental differences in perspectives between AORA jurisdictions as to the proper role and scope of government in the management of public resources. In the EU, a simplified view is that policies should be coordinated as much as possible to maximize effectiveness and efficiency, ultimately ensuring that high levels of environmental quality are attained (but while leaving some flexibility at the national level to customize measures that are contextually fit for purpose). In Canada, while the federal government has maintained a leading role due to its authorities in ocean management, the implementation has been pursued through regional processes, a framework compatible with EBM (Forst, 2009).

In the USA, however, the history of federalism since the country's founding has traditionally emphasized the need for more devolved power, citizen deliberation, and has portrayed debate and contestation as virtues (Ostrom and Ostrom, 2004). Centrally coordinated policies and agencies are not necessarily more economically efficient than the “messy” polycentric systems that characterize the overlapping and shifting institutional policy landscape (Ostrom and Ostrom, 2004; Ostrom, 2005, 2009), especially when dealing with complicated socio-ecological systems operating at multiple scales. Vociferous contestation in politics and in the courts is thus much more accepted as a legitimate facet of governance in the USA compared to Canada or the EU. The difference in fundamental views on the role of governments in governance processes have been implicated as a source of divergence in conservation science research priorities among natural resource managers in Canada and the USA (Illical and Harrison, 2007; Rudd et al., 2011).

Federalism thus plays a role in complicating the implementation of EBM in AORA jurisdictions where inter-jurisdictional coordination is needed. Each State in the USA or Member State in the EU has effective authority in ocean areas adjacent to their coasts. Political influences and pressures relating to ocean activities in state waters vary greatly in the different regions of the nations and may diminish the political will to implement EBM approaches on a national or sub-national scale. In contrast, Canada's Oceans Act provides the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans a lead role in the coordination of ocean management activities, working in collaboration with provinces, territories and First Nations. The Oceans Act is therefore a significant statutory framework for the implementation of EBM while acknowledging the unique ecosystems of Canada's three coasts.

Challenges Arising From Increasing Populism

There are currently populist and nationalistic undercurrents in politics at various levels in and beyond the AORA jurisdictions. One context in which broader societal issues, relating largely to national identity, may constrain effective EBM implementation is with Brexit (i.e., the United Kingdom's impending departure from the EU–Boyes and Elliott, 2016). The UNCLOS, in Article 63(1), requires neighboring countries to “seek … to agree” upon certain measures in relation to shared fish stocks. In principle, when the UK leaves the EU, many fish stocks will become shared between the UK and the EU and the Article 63(1) requirement will apply to the UK and the EU in respect of those stocks. Beyond the so-called “transition” or “implementation” period of Brexit, it remains to be seen whether or how that requirement will be implemented. Ultimately, and irrespective of Article 63(1), any failure by the UK and the EU to cooperate on the conservation and management of shared fish stocks may lead to challenges to effective EBM in the waters concerned.

Political Leadership

Political leadership is necessary for successful EBM and is often expressed via non-regulatory mandates such as policy declarations or reflected implicitly in the annual budgeting process. In Europe, there is substantial political depth behind mandates for EBM as evidenced by European Parliament Motions (European Parliament, 2018). In Canada, there has been a long-standing commitment to EBM (Rutherford et al., 2005) through the Oceans Act and recent initiatives to expand marine conservation beyond biodiversity objectives. In the US, there are also broad mandates in place to facilitate EBM (Fluharty, 2012; Foran et al., 2016; NMFS, 2016). Areas beyond national jurisdiction also increasingly appear to be garnering a political mandate for EBM (European Parliament, 2018). Increasing effort to engage stakeholders potentially affected by ocean development or change (e.g., indigenous communities, resource users, coastal communities, etc.) may also reflect an increasing level of political will to engage in EBM.

The appropriate allocation of resources to enable the implementation of EBM is, of course, a critical indicator of the level of political support for EBM and implicitly highlights the level of political will for implementing EBM. If one views political will as being driven relatively simply by the domestic economic costs and benefits of supporting a particular position (e.g., Sunstein, 2007), the relative lack of EBM implementation can be interpreted by taking the view that the perceived financial costs of engaging in EBM currently outweigh the perceived benefits of implementation. While there may be symbolic support for EBM, little real support in terms of resources implies little political will to support EBM over a time frame for it to achieve synergies and pay back the efforts to nurture it. If one views political will as a reflection of the domestic political and economic costs and benefits of supporting a particular position, the challenges of successfully implemented EBM may become even more vexing.

Business Case for EBM

We contend that the regulatory mandate for EBM exists, but implementation is weak. The lack of political will to implement EBM may reflect the relative levels of perceived costs and benefits of taking action to implement EBM. In theory, successfully bolstering the business case for EBM should increase levels of political will and increase levels of support for EBM via non-regulatory mandates, as well as clarification and strengthening of formal legislation. As is typical for environmental investments, the costs of taking action to implement EBM can be significant, occur in the near-term, and may affect in particular a small group of stakeholders that represent effective lobbies (e.g., oil and gas industry, industrial fishing companies, etc.). The benefits from EBM are, on the contrary, less specific, may be delayed temporally, and accrue to more diverse beneficiaries.

Economic Costs and Benefits Arising From Implementing EBM

Following best practices in economic cost-benefit analysis (Pearce et al., 2006; Treasury Board Secretariat, 2007; EPA, 2008), full accounting systems for natural capital consider profits from industrial and extractive use but also a full spectrum of benefits arising from recreational use, ecological support functions, passive use (e.g., existence value), and information provision (Helm, 2015). Passive or non-use values are important because citizens who live far from the coast can still put significant value on marine and coastal habitats and species (Carson et al., 2003; Rudd, 2009; Drakou et al., 2017).

From a transaction economics perspective (Williamson, 1998), the effectiveness and efficiency of governance is a function of scale-matching. Specifically, the transaction costs of EBM governance (i.e., coordination, negotiation, monitoring, enforcement, litigation) can be minimized by ensuring that the scope of ocean governance is aligned with the geographic, political, and ecological scope of the challenges that EBM is being used on. Creating appropriate institutions and building technical and human capacity for EBM over medium- to long-time planning horizons can be viewed as an investment to increase social, economic, and political predictability within increasingly uncertain biophysical and technological environments. Like any investment, there is an upfront investment that anticipates longer-run benefits will outweigh costs of investment. If financing can be raised, either through traditional or innovative (Thiele and Gerber, 2017) means, it is more likely that EBM objectives can be met.

Functionally, the EBM process can be used as a tool for problem structuring (Hisschemöller and Hoppe, 1995), helping to better align scientific effort with policy needs by better articulating EBM challenges and/or identifying and creating new knowledge that addresses those challenges. Well-structured problems are those to which specific management actions may then be effectively applied (Rudd, 2011), thus increasing the likelihood of positive real-world EBM outcomes. Problem structuring may help in streamlining the processes by which ocean regulatory decisions are produced and increase predictability. Many in the ocean stakeholder community believe that lack of predictability in permitting and administrative decision-making is the primary impediment to successfully investing in ocean activities (Sterne et al., 2009; Craig and Ruhl, 2014). Unpredictable administrative outcomes are also a primary driver of litigation between stakeholders and governments. Moving away from sectoral approaches and toward more integrated EBM approaches should decrease the uncertainty and unpredictability that spurs legal disputes and litigation and ultimately improve environmental outcomes in the ocean realm.

The EBM Economic Narrative

For EBM advocates, the presumption is that EBM investments pay dividends and avoid increasing levels of conflict and over-exploitation of ocean resources in the long run. A Business as Usual (BAU) ocean management approach may, however, generate briefly higher short-term levels of profits for private sector actors, with potential spin-off effects in the economy and some government tax revenue. A BAU strategy also has lower transaction costs of governance in the short-term compared to EBM. This storyline may explain the relative lack of implementation success.

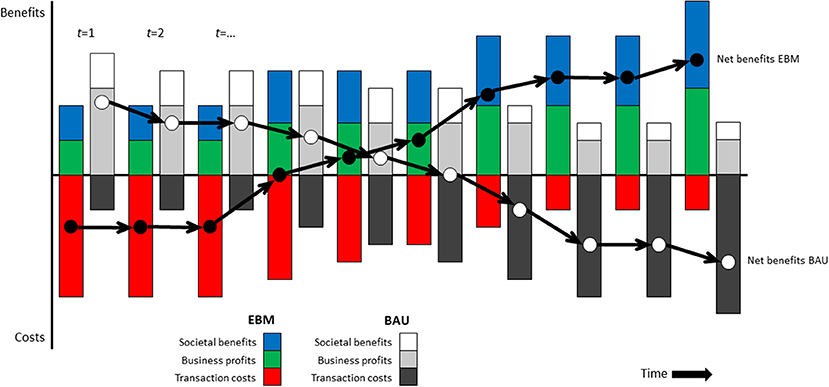

Figure 2 provides a representation of the conceptual arguments for EBM providing a higher level of long-term economic benefits relative to a BAU strategy. Each consideration (see below) is, however, still not well-quantified; this EBM storyline requires economic research to assess if the conceptual benefits of EBM are delivered in practice over time.

Figure 2. Comparing the projected trajectory of hypothetical net benefits from BAU and EBM management.

The rationale for supporting sustained long-term investment in EBM-oriented ocean governance revolves, however, around a number of broader considerations: (1) economic profitability for the private sector (and spin-offs and tax revenues) will decline if ocean resources are over-exploited over time (Clark, 1973); (2) other non-market and social benefits important to society and derived from ocean ecosystem services are inadequately accounted for under typical BAU governance systems (Pearce et al., 2006); (3) non-market and social benefits under BAU may decline over time due to changing public perceptions regarding ocean conditions; (4) the transaction costs of ocean governance will increase over time under BAU given increasing levels of contestation over ocean resource use and conservation; (5) investments in EBM increase the predictability of ocean governance, thereby providing benefits to the private sector and help protect profitability in the face of increasing environmental uncertainty; (6) a more predictable social, economic, and political environment influences planning horizons, allowing organizations and resource users to more effectively consider investments in sustainability that provide substantial, but relatively long-run, returns; and (7) EBM has a relative advantage compared to BAU in coping with uncertainty due to the deliberative and participatory orientation of EBM. Each presumption requires research to ascertain its validity and the relative magnitude of various EBM benefits.

It is important to note that as an integrated framework, EBM supports the consideration and assimilation of stakeholders' perspectives along multiple dimensions. It is a forum through which diverse sectoral interests, differing government mandates, and public agendas can be articulated for the purpose of facilitating the reconciliation of them. As the business case for EBM grows stronger we should expect to see increased levels of political support for EBM implementation efforts, a phenomenon which could in principle be measured (e.g., Schaffrin et al., 2015).

Conclusions

EBM provides society with a complex governance challenge. To address current and looming challenges to ocean environments and resources, we must, in the face of scientific uncertainties and taking into account socio-ecological contextual differences in different countries and regions, design, choose and implement interventions and investments to support ocean sustainability. On a positive note, our review found that irrespective of the detailed requirements of legislation or policy across AORA jurisdictions, or the efficacy of their actual implementation, most of the major ocean pressures and uses posing threats to ocean sustainability have some form of coverage by national or regional legislation. The coverage is, in fact, rather comprehensive.

Still, there are numerous impediments to effective implementation of EBM. They arise for a number of factors, including practical factors relating to the integration and operation of agencies and departments, a lack of adequate policy alignment, and a variety of other socio-political factors. We suspect that a lack of political will to adequately support successful EBM implementation is to some degree a function of the perceptions within government as to the relative costs and benefits of EBM vs. status quo approaches to ocean management. While the costs and benefits of EBM are not yet adequately quantified, either in the AORA jurisdictions or in other regions, we also recognize that there is an argument that the costs of inaction on the ocean governance front (i.e., the BAU trajectory) may be very high over the longer term due to the escalating pace of environmental change in the marine environment.

For EBM to be more successfully implemented in the future, it will be important to address very important gaps in our knowledge regarding how ocean governance helps to synergize or support EBM, and how specific mandates signal and shape political, policy, and implementation actions that affect EBM outcomes. This suggests some priorities for further research to build understanding of how, when, and where EBM may work. Topics which need sustained and focused research effort include: (1) integrating sub-national governance mandates into a comprehensive review of mandate gaps and policy coherence across AORA jurisdictions; (2) review of non-legislative mandates across jurisdictions; (3) assessment of the assumptions and economic viability of the business case in support of EBM, to see if EBM benefits truly outweigh the transaction costs of implementation; (4) identifying the determinants of successful EBM implementation and how pathways to success might be quantified given different social, political, and economic contexts in which EBM is being deployed; and (5) assessing if an incremental or evolutionary approach to EBM policy development (i.e., “policy layering”) sufficient to keep pace with rapidly advancing ocean technologies and environmental change.

We note with concern that if challenges regarding EBM implementation exist in the North Atlantic, we can expect that in less developed regions where financial and governance capacity may be lower, that implementation of EBM could be even more challenging.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in a March 2018 workshop held in London under the auspices of the Atlantic Ocean Research Alliance Coordination and Support Action. MAR coordinated preparation of the manuscript. MC and MAR produced the figures. All authors contributed with text.

Funding

The Atlantic Ocean Research Alliance Coordination and Support Action (AORA-CSA) has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 652677.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

MAR was supported by a Nippon Foundation Chair in Sustainable Ocean Governance & Marine Management.

References

Aanesen, M., Armstrong, C. W., Bloomfield, H. J., and Röckmann, C. (2014). What does stakeholder involvement mean for fisheries management? Ecol. Soc. 19:35. doi: 10.5751/ES-06947-190435

Arkema, K. K., Abramson, S. C., and Dewsbury, B. M. (2006). Marine ecosystem-based management: from characterization to implementation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 4, 525–532. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2006)4[525:MEMFCT]2.0.CO

Barange, M., Bahri, T., Beveridge, M. C. M., Cochrane, K. L., Funge-Smith, S., and Poulain, F. (2018). Impacts of Climate Change on Fisheries and Aquaculture: Synthesis of Current Knowledge, Adaptation and Mitigation Options. Rome: FAO, 628.

Belschner, T., Ferretti, J., Strehlow, H., Kraak, S., Döering, R., Kraus, G., et al. (2018). Evaluating fisheries systems – a comprehensive analytical framework and its application to the EU's Common Fisheries Policy. Fish Fish. early view. doi: 10.1111/faf.12325. [Epub ahead of print].

Bigagli, E. (2015). The EU legal framework for the management of marine complex social–ecological systems. Marine Policy 54, 44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.11.025

Birnie, P., Boyle, A., and Redgwell, C. (2009). International Law & The Environment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boyes, S. J., and Elliott, M. (2014). Marine legislation – the ultimate ‘horrendogram’: international law, European directives & national implementation. Marine Pollut. Bull. 86, 39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.06.055

Boyes, S. J., and Elliott, M. (2016). Brexit: the marine governance horrendogram just got more horrendous! Marine Pollut. Bull. 111, 41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.08.020

Boyes, S. J., Elliott, M., Murillas-Maza, A., Papadopoulou, N., and Uyarra, M. C. (2016). Is existing legislation fit-for-purpose to achieve Good Environmental Status in European seas? Marine Pollut. Bull. 111, 18–32. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.06.079

Carson, R. T., Mitchell, R. C., Hanemann, M., Kopp, R. J., Presser, S., and Ruud, P. A. (2003). Contingent valuation and lost passive use: damages from the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Environ. Resource Econom. 25, 257–286. doi: 10.1023/A:1024486702104

Christie, D. R. (2015). Lead, follow, or be left behind: the case for comprehensive ocean policy and planning for Florida. Stetson Law Rev. 44, 335–396.

Clark, C. W. (1973). Profit maximization and the extinction of animal species. J. Political Econ. 81, 950–961. doi: 10.1086/260090

Cohen, M. D., March, J. G., and Olsen, J. P. (1972). A garbage can model of organizational choice. Admin. Sci. Quart. 17, 1–25. doi: 10.2307/2392088

Craig, R. K. (2015). An historical look at planning for the federal public lands: adding marine spatial planning offshore. George Washington J. Energy Environ. Law 6, 1–20.

Craig, R. K., and Ruhl, J. B. (2014). Designing administrative law for adaptive management. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 67, 1–88. Available online at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/vanlr67&div=4&g_sent=1&casa_token=

Drakou, E. G., Pendleton, L., Effron, M., Ingram, J. C., and Teneva, L. (2017). When ecosystems and their services are not co-located: oceans and coasts. ICES J. Marine Sci. 74, 1531–1539. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx026

Duff, J. (2017). The voice of local authories in coastal and marine spatial planning in the Northeast: insights from the regional ocean planning process. Sea Grant Law Policy J. 8, 6–17. Available online at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/sglum8&div=6&g_sent=1&casa_token=

EC (2008). COM (2008) 395 Final Guidelines for an Integrated Approach to Maritime Policy: Towards Best Practice in Integrated Maritime Governance and Stakeholder Consultation. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

EPA (2008). Guidelines for Preparing Economic Analyses (External Draft Review). Washington, DC: Environmental Protection Agency, 138.

European Parliament (2018). International Ocean Governance: an Agenda for the Future of Our Oceans in the Context of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Brussels: European Parliament.

European Parliament and European Council (2013). Regulation on the Common Fisheries Policy, amending Council Regulations (EC) No1954/2003 and (EC) No 1224/2009 and repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 2371/2002 and (EC) No 639/2004 and Council Decision 2004/585/EC ((EU) No 1380/2013). Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union.

Farley, J., Baker, D., Batker, D., Koliba, C., Matteson, R., Mills, R., et al. (2007). Opening the policy window for ecological economics: katrina as a focusing event. Ecol. Econom. 63, 344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.07.029

Fluharty, D. (2012). Recent developments at the federal level in ocean policymaking in the United States. Coastal Manage. 40, 209–221. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2012.652509

Foran, C. M., Link, J. S., Patrick, W. S., Sharpe, L., Wood, M. D., and Linkov, I. (2016). Relating mandates in the United States for managing the ocean to ecosystem goods and services demonstrates broad but varied coverage. Front. Marine Sci. 3:5. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00005

Forst, M. F. (2009). The convergence of integrated coastal zone management and the ecosystems approach. Ocean Coast. Manage. 52, 294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2009.03.007

Fritz, J.-S., and Hanus, J. (2015). The european integrated maritime policy: the next five years. Marine Policy 53, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.11.005

Garcia, S. M., Zerbi, A., Aliaume, C., Do Chi, T., and Lasserre, G. (2003). The Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries. Issues, Terminology, Principles, Institutional Foundations, Implementation and Outlook. Rome: FAO, 71.

Goble, D. D., Scott, J. M., and Davis, F. W. (2006). The Endangered Species Act at Thirty. Renewing the Conservation Promise (Volume 1). Washington, DC: Island Press.

Halpern, B. S., Longo, C., Hardy, D., McLeod, K. L., Samhouri, J. F., Katona, S. K., et al. (2012). An index to assess the health and benefits of the global ocean. Nature 488, 615–620. doi: 10.1038/nature11397

Hickey, G. M., Forest, P., Sandall, J. L., Lalor, B. M., and Keenan, R. J. (2013). Managing the environmental science–policy nexus in government: perspectives from public servants in Canada and Australia. Sci. Public Policy 40, 529–543. doi: 10.1093/scipol/sct004

Hisschemöller, M., and Hoppe, R. (1995). Coping with intractable controversies: the case for problem structuring in policy design and analysis. Knowledge Tech. Policy 8, 40–60.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., and Bruno, J. F. (2010). The impact of climate change on the world's marine ecosystems. Science 328, 1523–1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1189930

Illical, M., and Harrison, K. (2007). Protecting endangered species in the US and Canada: the role of negative lesson drawing. Can. J. Political Sci. 40, 367–394. doi: 10.1017/S0008423907070175

Jones, P. J. S., Lieberknecht, L. M., and Qiu, W. (2016). Marine spatial planning in reality: introduction to case studies and discussion of findings. Marine Policy 71, 256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.04.026

Kearney, J., Berkes, F., Charles, A., Pinkerton, E., and Wiber, M. (2007). The role of participatory governance and community-based management in integrated coastal and ocean management in Canada. Coast. Manage. 35, 79–104. doi: 10.1080/10.1080/08920750600970511

Lawton, R. N., and Rudd, M. A. (2013). Crossdisciplinary research contributions to the United Kingdom's National Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosyst. Servic. 5, 149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.07.009

Leslie, H. M., and McLeod, K. L. (2007). Confronting the challenges of implementing marine ecosystem-based management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5, 540–548. doi: 10.1890/060093

Link, J. S., and Browman, H. I. (2014). Integrating what? Levels of marine ecosystem-based assessment and management. ICES J. Marine Sci. 71, 1170–1173. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsu026

Link, J. S., and Browman, H. I. (2017). Operationalizing and implementing ecosystem-based management. ICES J. Marine Sci. 74, 379–381. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsw247

Link, J. S., Dickey-Collas, M., Rudd, M. A., McLaughlin, R., Macdonald, N. M., Thiele, T., et al. (2018). Clarifying mandates for marine ecosystem-based management. ICES J. Mar. Sci. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsy1169

Linke, S., and Jentoft, S. (2016). Ideals, realities and paradoxes of stakeholder participation in EU fisheries governance. Environ. Sociol. 2, 144–154. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2016.1155792

Marshak, A. R., Link, J. S., Shuford, R., Monaco, M. E., Johannesen, E., Bianchi, G., et al. (2017). International perceptions of an integrated, multi-sectoral, ecosystem approach to management. ICES J. Marine Sci. 74, 414–420. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsw214

Meijerink, S., and Huitema, D. (2010). Policy entrepreneurs and change strategies: lessons from sixteen case studies of water transitions around the globe. Ecol. Soc. 15:21. doi: 10.5751/ES-03509-150221

National Ocean Council (2013). National Ocean Policy Implementation Plan. Washington, DC: Office of Science and Technology Policy, Office of the White House, 32.

Nilsson, M., Zamparutti, T., Petersen, J. E., Nykvist, B., Rudberg, P., and McGuinn, J. (2012). Understanding policy coherence: analytical framework and examples of sector–environment policy interactions in the EU. Environ. Policy Govern. 22, 395–423. doi: 10.1002/eet.1589

NMFS (2016). Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management Policy of the National Marine Fisheries Service. Washington, DC: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

O'Leary, B. C., Brown, R., Johnson, D., von Nordheim, H., Ardron, J., Packeiser, T., et al. (2012). The first network of marine protected areas (MPAs). on the high seas: the process, the challenges and where next. Marine Policy 36, 598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2011.11.003

ORAP (2013). Implementing Ecosystem-Based Management: A Report to the National Ocean Council. Washington, DC: Ocean Research Advisory Panel.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2009). A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325, 419–422. doi: 10.1126/science.1172133

Ostrom, E., and Ostrom, V. (2004). The quest for meaning in public choice. Am. J. Econom. Sociol. 63, 105–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1536-7150.2004.00277.x

Pearce, D., Atkinson, G., and Mourato, S. (2006). Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment: Recent Developments. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Pennington, D. D., Simpson, G. L., McConnell, M. S., Fair, J. M., and Baker, R. J. (2013). Transdisciplinary research, transformative learning, and transformative science. BioScience 63, 564–573. doi: 10.1525/bio.2013.63.7.9

Raakjaer, J., van Leeuwen, J., van Tatenhove, J., and Hadjimichael, M. (2014). Ecosystem-based marine management in European regional seas calls for nested governance structures and coordination - a policy brief. Marine Policy 50, 373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.03.007

Ramírez-Monsalve, P., Raakjær, J., Nielsen, K. N., Laksá, U., Danielsen, R., Degnbol, D., et al. (2016). Institutional challenges for policy-making and fisheries advice to move to a full EAFM approach within the current governance structures for marine policies. Marine Policy 69, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.03.016

Rudd, M. A. (2004). An institutional framework for designing and monitoring ecosystem-based fisheries management policy experiments. Ecol. Econom. 48, 109–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2003.10.002

Rudd, M. A. (2009). National values for regional aquatic species at risk in Canada. Endang. Species Res. 6, 239–249. doi: 10.3354/esr00160

Rudd, M. A. (2011). How research-prioritization exercises affect conservation policy. Conserv. Biol. 25, 860–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01712.x

Rudd, M. A., Beazley, K. F., Cooke, S. J., Fleishman, E., Lane, D. E., Mascia, M. B., et al. (2011). Generation of priority research questions to inform conservation policy and management at a national level. Conserv. Biol. 25, 476–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01625.x

Rutherford, R. J., Herbert, G. J., and Coffen-Smout, S. S. (2005). Integrated ocean management and the collaborative planning process: the Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management (ESSIM). Initiative. Marine Policy 29, 75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2004.02.004

Sainsbury, K. J., Punt, A. E., and Smith, A. D. M. (2000). Design of operational management strategies for achieving fishery ecosystem objectives. ICES J. Marine Sci. 57, 731–741. doi: 10.1006/jmsc.2000.0737

Salomon, M., and Dross, M. (2013). Challenges in cross-sectoral marine protection in Europe. Marine Policy 42, 142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.02.012

Sander, G. (2018). Ecosystem-based management in Canada and Norway: the importance of political leadership and effective decision-making for implementation. Ocean Coast. Manage. 163, 485–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.08.005

Schaefer, N., and Barale, V. (2011). Maritime spatial planning: opportunities & challenges in the framework of the EU integrated maritime policy. J. Coast. Conserv. 15, 237–245. doi: 10.1007/s11852-011-0154-3

Schaffrin, A., Sewerin, S., and Seubert, S. (2015). Toward a comparative measure of climate policy output. Policy Stud. J. 43, 257–282. doi: 10.1111/psj.12095

Scharpf, F. W. (1997). Games Real Actors Play: Actor-Centered Institutionalism in Policy Research. Oxford: Westview Press.

Slocombe, D. S. (1993). Implementing ecosystem-based management. BioScience 43, 612–621. doi: 10.2307/1312148

Sterne, J. K., Jensen, T. C., Keil, J., and Roos-Collins, R. (2009). The seven principles of ocean renewable energy: a shared vision and call for action. Roger Williams Univ. Law Rev. 14, 600–623. Available online at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/rwulr14&div=22&g_sent=1&casa_token=&collection=journals

Sunstein, C. R. (2007). Of Montreal and Kyoto: a tale of two protocols. Harvard Environ. Law Rev. 31, 1–66. Available online at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/helr31&div=5&g_sent=1&casa_token=&collection=journals

Sutherland, W. J., Barnard, P., Broad, S., Clout, M., Connor, B., Côté, I. M., et al. (2017). A 2017 horizon scan of emerging issues for global conservation and biological diversity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 32, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2016.11.005

Thiele, T., and Gerber, L. R. (2017). Innovative financing for the High Seas. Aquatic Conserv. 27, 89–99. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2794

Treasury Board Secretariat (2007). Canadian Cost-Benefit Analysis Guide: Regulatory Proposals. Ottawa: Treasury Board Secretariat.

van Hoof, L., van Leeuwen, J., and van Tatenhove, J. (2012). All at sea; regionalisation and integration of marine policy in Europe. Maritime Stud. 11:9. doi: 10.1186/2212-9790-11-9

van Leeuwen, J., Raakjaer, J., van Hoof, L., van Tatenhove, J., Long, R., and Ounanian, K. (2014). Implementing the marine strategy framework directive: a policy perspective on regulatory, institutional and stakeholder impediments to effective implementation. Marine Policy 50, 325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.03.004

van Tatenhove, J., Raakjaer, J., van Leeuwen, J., and van Hoof, L. (2014). Regional cooperation for European seas: governance models in support of the implementation of the MSFD. Marine Policy 50, 364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.02.020

Visbeck, M., Kronfeld-Goharani, U., Neumann, B., Rickels, W., Schmidt, J., van Doorn, E., et al. (2014). Securing blue wealth: the need for a special sustainable development goal for the ocean and coasts. Marine Policy 48, 184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.03.005

Wenzel, B. (2018). Rational instrument or symbolic signal? Explaining coordination structures in the Directorate-General for Fisheries and Maritime Affairs of the European Commission. Public Policy Admin. 33, 149–169. doi: 10.1177/0952076716683764

Wiber, M. G., Rudd, M. A., Pinkerton, E., Charles, A. T., and Bull, A. (2010). Coastal management challenges from a community perspective: the problem of 'stealth privatization' in a Canadian fishery. Marine Policy 34, 598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2009.11.010

WWF Canada (2013). An Overview of Federal Instruments for the Protection of the Marine Environment in Canada. Ottawa: WWF Canada, 47.

Keywords: ecosystem approach, ecosystem-based management, marine policy, ocean governance, ocean policy, mandates, North Atlantic

Citation: Rudd MA, Dickey-Collas M, Ferretti J, Johannesen E, Macdonald NM, McLaughlin R, Rae M, Thiele T and Link JS (2018) Ocean Ecosystem-Based Management Mandates and Implementation in the North Atlantic. Front. Mar. Sci. 5:485. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00485

Received: 04 August 2018; Accepted: 29 November 2018;

Published: 14 December 2018.

Edited by:

Lyne Morissette, M–Expertise Marine, CanadaReviewed by:

Marcus Geoffrey Haward, University of Tasmania, AustraliaChristian T. K.-H. Stadtlander, Independent researcher, St. Paul Minnesota, United States

Christos Karelakis, Democritus University of Thrace, Greece

Nengye Liu, University of Adelaide, Australia

Copyright © 2018 Rudd, Dickey-Collas, Ferretti, Johannesen, Macdonald, McLaughlin, Rae, Thiele and Link. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Murray A. Rudd, bXVycmF5cnVkZEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Murray A. Rudd

Murray A. Rudd Mark Dickey-Collas2,3

Mark Dickey-Collas2,3 Johanna Ferretti

Johanna Ferretti Ellen Johannesen

Ellen Johannesen Jason S. Link

Jason S. Link