Abstract

Introduction:

The transition towards a sustainable blue economy (SBE) is a crucial component of global marine economic governance. This study examines the evolution of China’s marine economy policies and their role in facilitating this transition.

Method:

Through a systematic review of 40 national policy texts from 2000 to 2023, this study uses content analysis and social network analysis to conduct a multidimensional empirical analysis. We analyze policy development trends, thematic priorities, and structural characteristics across China’s three major marine economic zones– the Northern Marine Economic Zone (Liaoning, Hebei, Tianjin, Shandong), Eastern Marine Economic Zone (Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shanghai), and Southern Marine Economic Zone (Fujian, Guangdong, Hainan, Guangxi). These zones were chosen due to their distinct economic profiles, resource endowments, and roles in national marine strategies.

Result:

The research findings are as follows: 1. Policy evolution occurred in three phases: rapid economic growth (2003–2010), integration of economy and environment (2011–2018), and sustainable development (2019–2023), though economic objectives remain dominant. 2. A pronounced imbalance in policy tools: environmental tools (42.18%) were most frequent, followed by supply-oriented (37.30%) and demand-oriented tools (20.52%). 3. Regional disparities: Northern zones (politically closer to the central government) prioritized supply-oriented tools (e.g., infrastructure funding), while Southern and Eastern zones emphasized environmental tools (e.g., regulations) .

Discussion:

The study concludes that China’s policy framework still prioritizes industrial growth over ecological balance. To advance SBE, policymakers must rebalance tool usage, and tailor strategies to regional contexts.

1 Introduction

The rapid expansion of global marine industries has contributed significantly to economic growth while simultaneously imposing mounting pressure on marine ecosystems. Issues such as overfishing, eutrophication, plastic pollution, and acidification have emerged as critical threats to marine biodiversity and sustainability (Hobday et al., 2000; Derraik, 2002; Smith et al., 2006; Hendriks et al., 2010; González-Wangüemert et al., 2018; Chu Van et al., 2019). In response, the United Nations adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, with Goal 14, “Life Below Water,” specifically promoting the sustainable use of ocean resources and marine ecosystem conservation (Web-Chinese D; Cormier and Elliott, 2017). In this context, the blue economy has emerged as a conceptual and policy framework aimed at balancing economic development with ecological integrity. Unlike the traditional marine economy, which often prioritizes industrial output, the blue economy emphasizes long-term sustainability, ecosystem services, and inclusive growth (Spalding, 2016; Admin, 2020; Xinhua, 2022). Countries such as Canada and Australia have begun to institutionalize blue economy strategies, integrating marine spatial planning, low-carbon marine energy, and international cooperation into their national development plans (Bennett et al., 2019; Novaglio et al., 2022; Stephenson and Hobday, 2024).

China, as one of the world’s largest maritime economies, has also actively expanded its marine industrial base in recent decades. The country’s marine fishery output accounts for approximately 30% of the global total, and the overall value of its marine economy reached 9.9 trillion yuan in 2023, representing 7.9% of national GDP (Pace et al., 2023; People’s Daily Overseas Edition, China’s marine economy is recovering strongly, 2024). Alongside traditional sectors such as fisheries and shipbuilding, new areas like offshore energy, marine biomedicine, and coastal tourism are also gaining momentum. However, China’s marine development has faced increasing challenges related to pollution, resource overexploitation, and an imbalanced industrial structure (Choudhary et al., 2021; Pace et al., 2023). These challenges raise critical concerns about how to realign marine economic policies to support a transition from a growth-driven model to a sustainability-oriented blue economy. Although the Chinese government has released a series of national and local policies concerning marine development, the concept of the “blue economy” is rarely directly referenced in provincial policy texts. Instead, terms such as “marine economy” or “sustainable marine development” are more common, often lacking a unified definition or operational framework (Daoji and Daler, 2004; Bari, 2017; Wang et al., 2019). Existing scholarship has explored environmental regulation, marine resource governance, and industrial innovation (Vierros and De Fontaubert, 2017; Yang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020), but there remains a significant gap in understanding how policy tools are used to promote this conceptual transition. Specifically, it is unclear how different regions in China—each with varying ecological, political, and economic conditions—adopt and implement policies aligned with blue economy goals.

Some studies have emphasized specific policies, such as ecological compensation mechanisms and fishery subsidy policies, in promoting the sustainable use of marine resources (Clark et al., 2005). At the same time, policy research often focuses on the development of specific sectors such as fishery harvesting and marine eco-tourism (Katsanevakis et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2020). Therefore, it is essential to systematically analyze China’s marine economic policies to understand their transition from a traditional growth-driven model to a sustainability-oriented approach. This study systematically analyzes 40 marine economy-related policy documents issued across China’s three major marine economic zones (Northern, Eastern, and Southern). By applying content analysis and social network analysis, we aim to (1) trace the evolution of marine economic policy priorities over time, (2) examine the spatial variation in policy tool usage, and (3) assess how these policy strategies contribute to sustainable marine development. By analyzing existing marine economy policies helps to grasp the direction of future policymaking and has theoretical value in selecting policy tools. The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces the research design and data sources, including the selection criteria for policy texts, analytical framework, and methodology. Section 3 examines the evolutionary characteristics of China’s marine economic policies and presents key results from content analysis and social network analysis. Section 4 integrates policy tool theory with empirical findings to explore the application patterns of policy tools in China’s marine governance and their implications for sustainability. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the research conclusions and proposes actionable recommendations for future policy refinement.

2 Research design

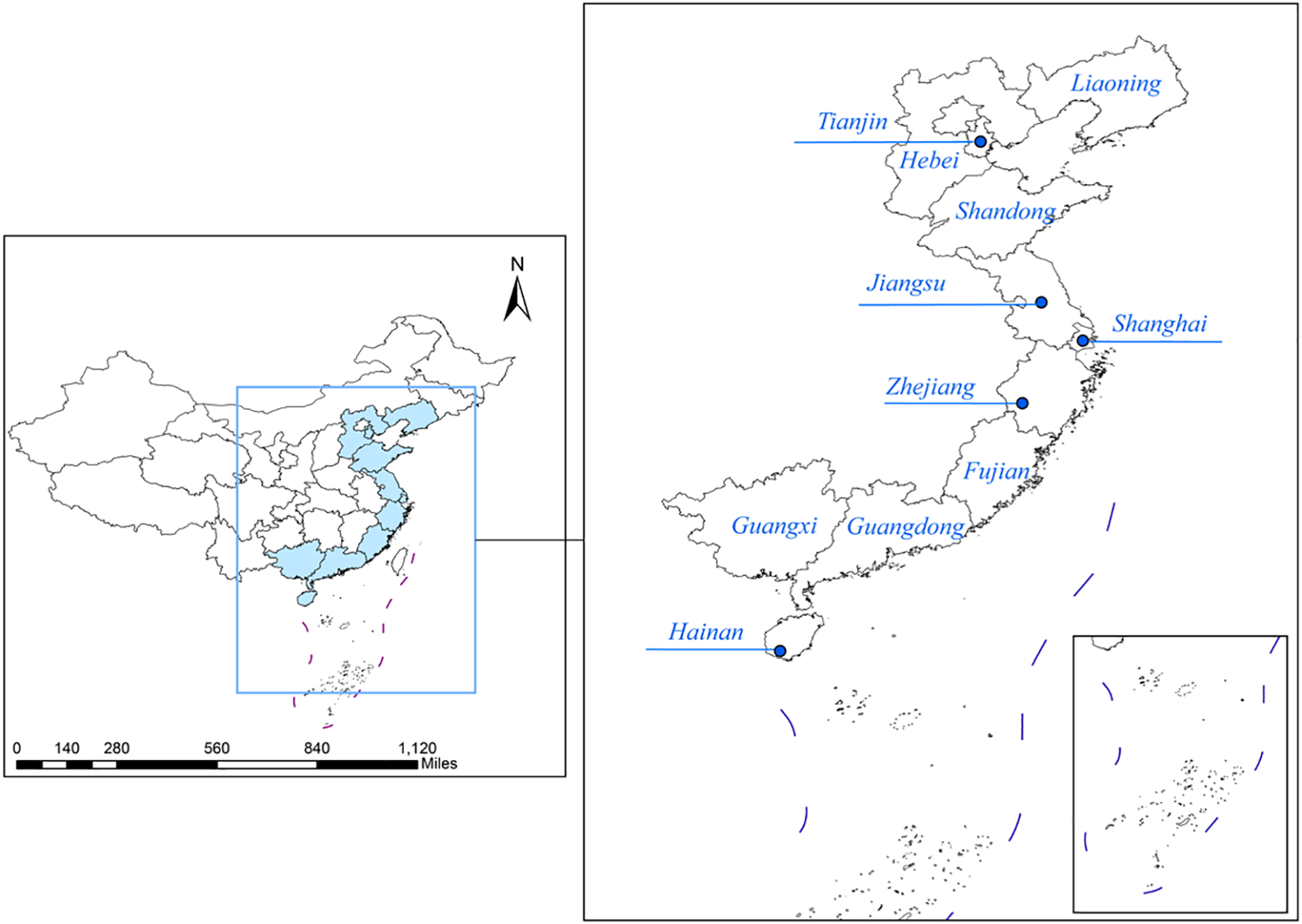

2.1 Characteristics of study area

The study area selected for this research includes three major coastal economic regions in China: the Northern Marine Economic Zone (Liaoning Province, Hebei Province, Tianjin City, Shandong Province), the Eastern Marine Economic Zone (Jiangsu Province, Zhejiang Province, Shanghai City), and the Southern Marine Economic Zone (Fujian Province, Guangdong Province, Hainan Province, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region). These zones were chosen because China has only 11 coastal provinces, and the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives Through 2035 officially categorizes them into three regions. The Northern Maritime Economic Zone is located in the Bohai Sea, encompassing the coastal areas and waters of the Liaodong Peninsula, Bohai Bay, and the Shandong Peninsula. It is home to advanced manufacturing industries and technology innovation bases in China. This maritime economic zone is next to Japan and South Korea, serving as an essential window for external trade and openness in northern China. The Eastern Marine Economic Zone is adjacent to the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea. It is a marine economic zone that radiates from Shanghai, the economic center of China. It has a high degree of outward orientation in its marine economy and is an important international region for the Belt and Road Initiative. The Southern Marine Economic Zone is located around the South China Sea and has the highest proportion of marine gross domestic product (GDP) among the three economic zones. These three marine economic regions possess abundant marine resources and developed port facilities, encompassing multiple sectors such as fisheries, shipping, and energy development. The total output value of the marine industries in these regions has exceeded 5 trillion yuan. In 2023, the total marine GDP in China reached 9909.7 billion yuan, accounting for 7.9% of the country’s total GDP. Obviously, China’s marine economy serves as an essential engine for sustained and healthy development (Morrissey and O’Donoghue, 2012; Sun et al., 2022). Figure 1 shows the research area.

Figure 1

Major coastal economic zones in China. ★ is Beijing, the capital of China.

2.2 Data sources

The policy texts used in this paper are sourced from various sources, including local government portals, the PKU Law website, the Government Legislation Database, and other policy databases. Referring to the existing literature and based on the requirements of this paper, keyword searches were conducted in titles and full texts using terms such as blue economy, marine economy, sustainable marine economy, and marine sustainable development. The initial texts obtained were then further filtered based on the following criteria: 1) Policies with titles containing keywords related to blue economy or marine economy and with content focused on these topics; 2) Policies with content primarily related to keywords such as blue economy, marine economy, and sustainable marine development, and with a focus on blue or marine economy. Additionally, while different entities published the policy documents involved in this study, the policies at the prefecture-level cities are predominantly guided by the policies set by the central government, ensuring consistency in policy objectives and directions. Therefore, the collected local policy documents for textual analysis are considered reliable. As of January 1, 2024, a total of 40 policy texts related to the development of the marine economy have been collected, as shown in the appendix.

2.3 Research methods

2.3.1 Social network analysis

This paper primarily utilizes social network analysis to visually analyze the focus of marine economy policies. Social network analysis is a quantitative method that examines relationships among entities within a network, allowing researchers to identify key nodes, structural patterns, and the overall connectivity of the network. This method operates on multiple levels and plays a crucial role in selecting problem-solving approaches and organizing operational structures. It has been widely used in research across various disciplines (Zhao et al., 2014; McIlgorm et al., 2022).By constructing a policy keyword network, this method helps reveal the core themes and policy focus areas in China’s marine economic development.

2.3.2 Content analysis

Content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that categorizes and summarizes text content based on predetermined coding conditions (Scott, 2012; Yan et al., 2015). This method allows for a systematic quantitative study of text content. During the process of content analysis, the text is broken down into multiple analytical units, which are then summarized and counted to identify patterns in the text content (Wasserman and Faust, 1994; Kleinheksel et al., 2020). Content analysis is widely applied in policy research, media studies, and governance analysis, making it a valuable tool for understanding marine economic policies. To conduct a comprehensive analysis of the policy texts, the collected 40 marine economy policies are encoded in Nvivo11. This encoding process was designed to ensure accuracy and completeness by using policy text paragraphs as the fundamental analysis units (Lowi, 1972; Schneider and Ingram, 1990). The specific steps of the encoding process are as follows: First, the content of the 40 policy texts was carefully organized. Paragraphs that explicitly mentioned the use of policy tools were identified and segmented. Each of these paragraphs was treated as an independent analysis unit to ensure that no relevant information was overlooked during the encoding process. This approach allows for a granular examination of how different policy tools are articulated and applied within the texts. Next, all policy documents were imported into the Nvivo11 software, a qualitative data analysis tool widely used for text analysis. Based on the predefined policy tool analysis framework, primary nodes representing the main categories of policy tools (e.g., supply-oriented, demand-oriented, and environment-oriented tools) were established. Corresponding secondary nodes were also created to capture specific subcategories within each primary node, such as funding Investment, trade regulations, or tax incentives. This hierarchical structure ensures a systematic and organized coding process. Finally, Each paragraph identified as an analysis unit was then encoded word by word, ensuring that every relevant policy tool mentioned in the text was accurately captured. Once all policy texts were encoded, the data was analyzed to identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the use of policy tools.

2.3.3 Policy tool analysis framework

Policy tools refer to the mechanisms and techniques governments use to support social change and achieve policy objectives (Krippendorff; Lakeman, 2008). Analyzing marine economy policy documents through the lens of policy tools enables us to systematically identify how governments prioritize different intervention strategies—such as regulation, investment, and incentives—in shaping the marine economy’s transformation pathways. This study draws on the classic policy tools analysis framework proposed by Rothwell and Zegveld. It categorizes marine economy policy tools into three types: supply-oriented, demand-oriented, and environment- oriented (Table 1) (Capano and Howlett, 2020).

Table 1

| Tool category | Tool name | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Supply-oriented | Funding Investment | Government or relevant institutions provide financial support promoting the development of the marine economy. This includes the development of marine resources, industrial cultivation, and research and development. |

| Infrastructure Construction | The government invests in and builds infrastructure to support the development of the marine economy, such as ports and shipping facilities. | |

| Public Services | Provision of professional services to ensure the development of the marine economy, such as the construction of public service platforms for technology transfer and commercialization. | |

| Information Support | Government or relevant institutions provide information and data support for the development of the marine economy. | |

| Human Resources | Policies related to talent cultivation for the development of the marine economy, with a focus on attracting, training, and managing talents required in the marine field. | |

| Demand-oriented | Trade Regulations | Management and regulatory measures imposed on trade activities, such as import and export regulations, trade restrictions, and prohibitions. |

| International Cooperation | Measures by the government to encourage cooperation with other countries or international organizations, such as transboundary resource cooperation and research information sharing. | |

| Demonstration Projects | Government support and promotion of demonstration projects and policies that involve the application and promotion of new technologies and models in the marine economy, such as the application of new marine technologies. | |

| Government Procurement | Government regulations for the procurement of goods, projects, and services to support the development of the marine economy. | |

| Environment-oriented | Goal Planning | Government’s strategic goals and planning for the development of the marine economy. |

| Regulatory Measures | Laws, regulations, and systems designated by the government to promote and manage the development and activities of the marine economy. | |

| Tax Incentives | Government policies aimed at encouraging the development of the marine economy, including tax exemptions, reductions, and other measures | |

| Financial Support | Government or financial institutions provide financial support and services to marine economy projects and enterprises, including low-interest loans, guarantees, and risk investments. | |

| Strategic Measures | Government measures and action plans to promote the development of the marine economy, including the establishment of a quality standard system for aquatic products. |

Presents the classification and explanation of policy tools in the marine economy.

Supply-oriented policy tools are direct strategies employed by the government to support the development of the marine economy, focusing on funding, talent, and infrastructure support. They can be further divided into financial investment, infrastructure construction, public services, information support, and human resources. These tools strengthen the “basic capabilities” and “development conditions” required for the marine economy through direct government investment of resources, such as building green ports, marine monitoring stations, and marine ranches, supporting renewable marine energy, clean fisheries, and marine ecological restoration projects.

Demand-oriented policy tools are used to stimulate market vitality in the marine economy and mitigate market risks. They can be further divided into trade regulations, international cooperation, demonstration projects, and government procurement. Through market incentives and institutional guidance, such as promoting replicable projects such as blue carbon pilot projects, ecological port construction, and blue technology incubation, strengthening international cross-border marine resource governance, and stimulating the participation of enterprises, the public, and other parties to promote the implementation of sustainable marine industries.

Environment-oriented policy tools primarily aim to create and ensure a favorable environment for the development of the marine economy. They can be further divided into goal planning, regulatory measures, tax incentives, financial support, and strategic measures. By standardizing the institutional environment, providing strategic planning, and implementing long-term incentives—such as formulating the Marine Functional Zoning to promote intensive use of marine spaces and prioritize ecological conservation—we can enhance the regulatory rigidity of systems like ecological red lines and pollutant discharge controls.

The effective development of the marine economy requires a balanced integration of supply-oriented, demand-oriented, and environment-oriented policy tools. Using these tools can create a synergistic effect that drives sustainable growth. By aligning these tools with regional priorities and global trends, governments can maximize the economic, social, and environmental benefits of their marine policies.

3 Policy development and visual analysis

3.1 Policy development progress

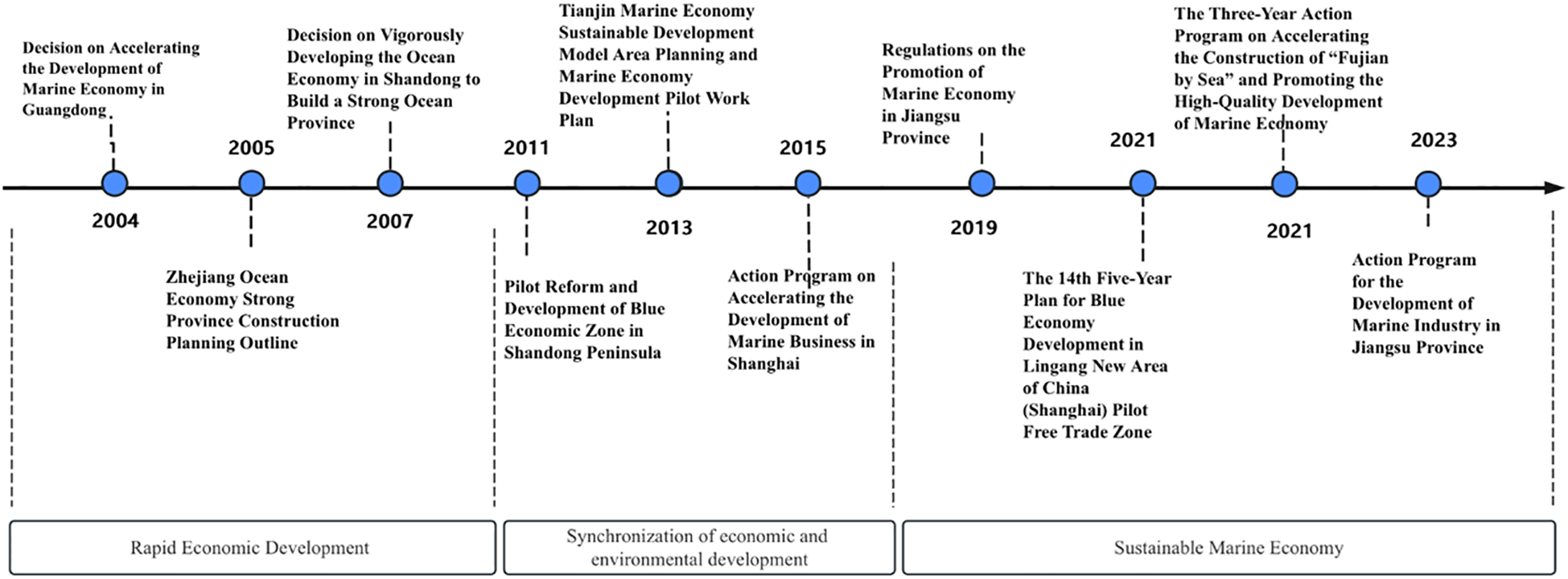

Over time, China’s marine economy policies in coastal areas have evolved in response to the nation’s economic development priorities. The policy direction has shifted from a focus on rapid marine economic growth to a balanced approach that includes resource protection and, more recently, an emphasis on the high-quality, sustainable development of the marine economy. The evolution is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

The evolution of China’s coastal marine economy policy.

3.1.1 Period of rapid marine economic growth (2003–2010)

Since China’s reform and opening up, the marine economy has been a crucial driver of national economic growth. Coastal economic development has heavily relied on marine resources, with industries like traditional fisheries, port trade, and marine energy expanding significantly since the 1990s. In 2003, the central government issued the Outline of the National Marine Economy Development Plan, providing macro-level guidance for marine economic growth. Subsequently, Guangdong and Hainan provinces led the way in the Southern Ocean Economic Zone, releasing their own marine economy development plans in 2004 and 2005, respectively, calling for accelerated growth. Policies during this period were broad lacking systematic planning; however, the Southern Economic Zone responded vigorously, implementing numerous initiatives.

3.1.2 Period of marine-economic and environmental integration (2011–2018)

In 2011, China initiated the Shandong Peninsula Blue Economic Zone as a pilot area for reform, marking the first policy use of the term “blue economy” and signaling a gradual shift toward resource protection and sustainable management. In 2013, Tianjin proposed a model area for sustainable marine economy development, emphasizing marine science and technology, resource monitoring, and environmental protection. Shanghai followed suit, introducing measures for marine industry development focused on industrial structure, technological advancement, and biomedicine. During this phase, local governments actively piloted new policies, exploring ways to optimize marine economic development while safeguarding the environment.

3.1.3 Period of sustainable marine economy (2019–2023)

In 2017, China adopted the concept of high-quality development, emphasizing green transformation and coordinated growth. By 2019, Jiangsu Province’s Marine Economy Promotion Regulation highlighted the need to improve both the quantity and quality of development, with a focus on sustainability. In 2021, Shanghai’s Lingang New Area was designated a pilot zone for blue economy growth, and Fujian Province introduced a Three-Year Action Program for High-Quality Marine Economic Development, emphasizing sustainability in the northern regions. Policies during this period have been more comprehensive, with regions aligning their plans to leverage their unique strengths for sustainable development.

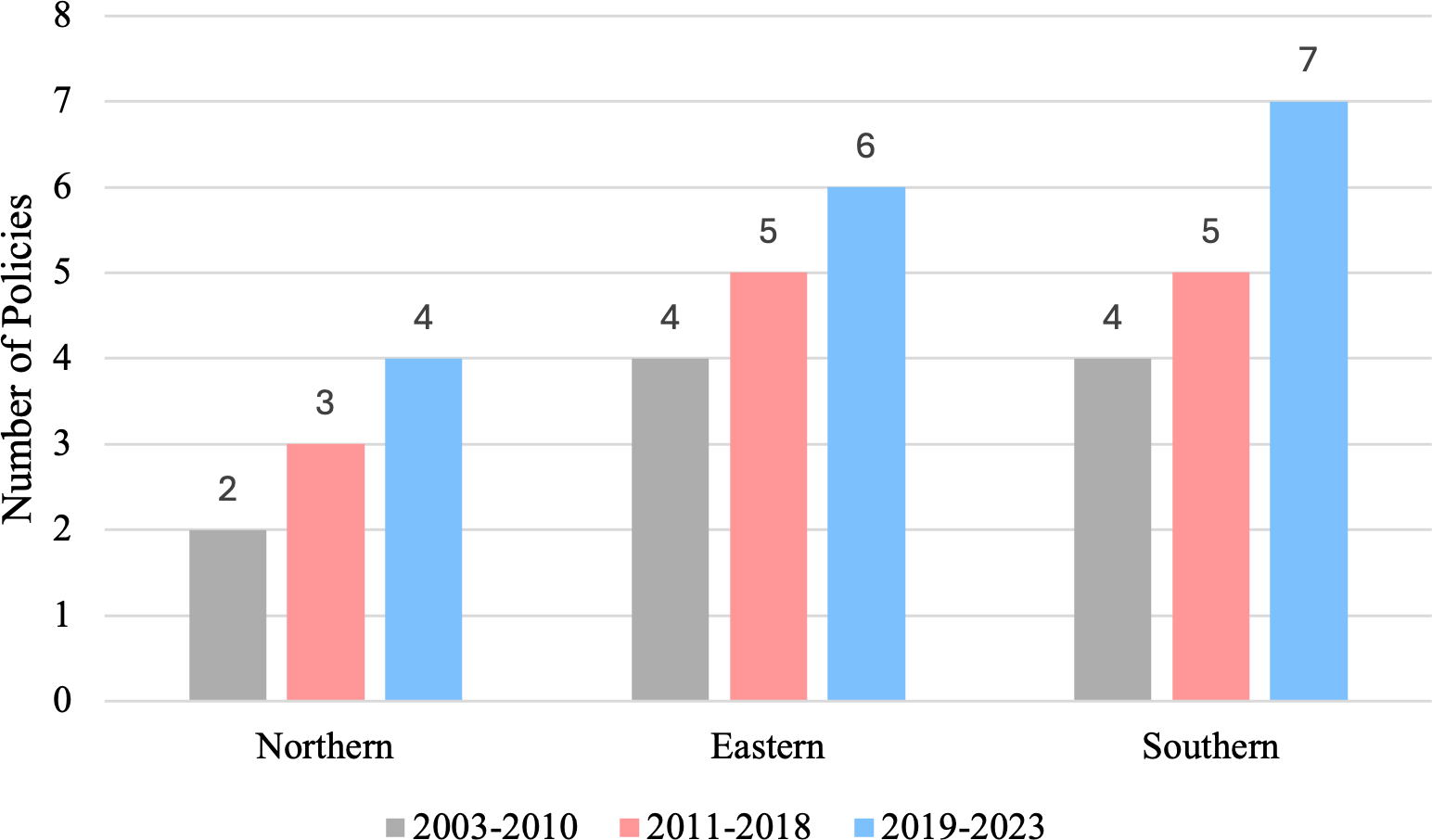

3.2 Distribution of policy texts by quantity

To some extent, the quantity of policy enactments reflects the attention, planning direction, and prospects of provincial governments towards the development of the marine economy. From Figure 3, it can be observed that the Southern Marine Economic Zone has the highest number of policies, totaling 16. The Eastern Marine Economic Zone follows with a total of 15 policies. Lastly, the Northern Marine Economic Zone has 9 policies. From a temporal perspective, based on the development process of policies, the number of issued policies has also increased, indicating that marine economic policies in coastal areas are being adjusted continuously in response to development. In terms of policy quantity, it may be influenced by several factors. On one hand, it could be due to economic development. The Eastern and Southern regions have higher marine economic output, requiring more comprehensive supporting policies. The implementation of policies also ensures the sustainable and rapid development of the marine economy while protecting the marine ecology, forming a closed loop. On the other hand, the Northern Marine Economic Zone is closer to the central government, and regional development takes into account the decision-making of the central government. The policies related to marine development and protection in the other two economic zones are relatively more flexible.

Figure 3

The number of marine economic policies enacted in the three marine economic zones.

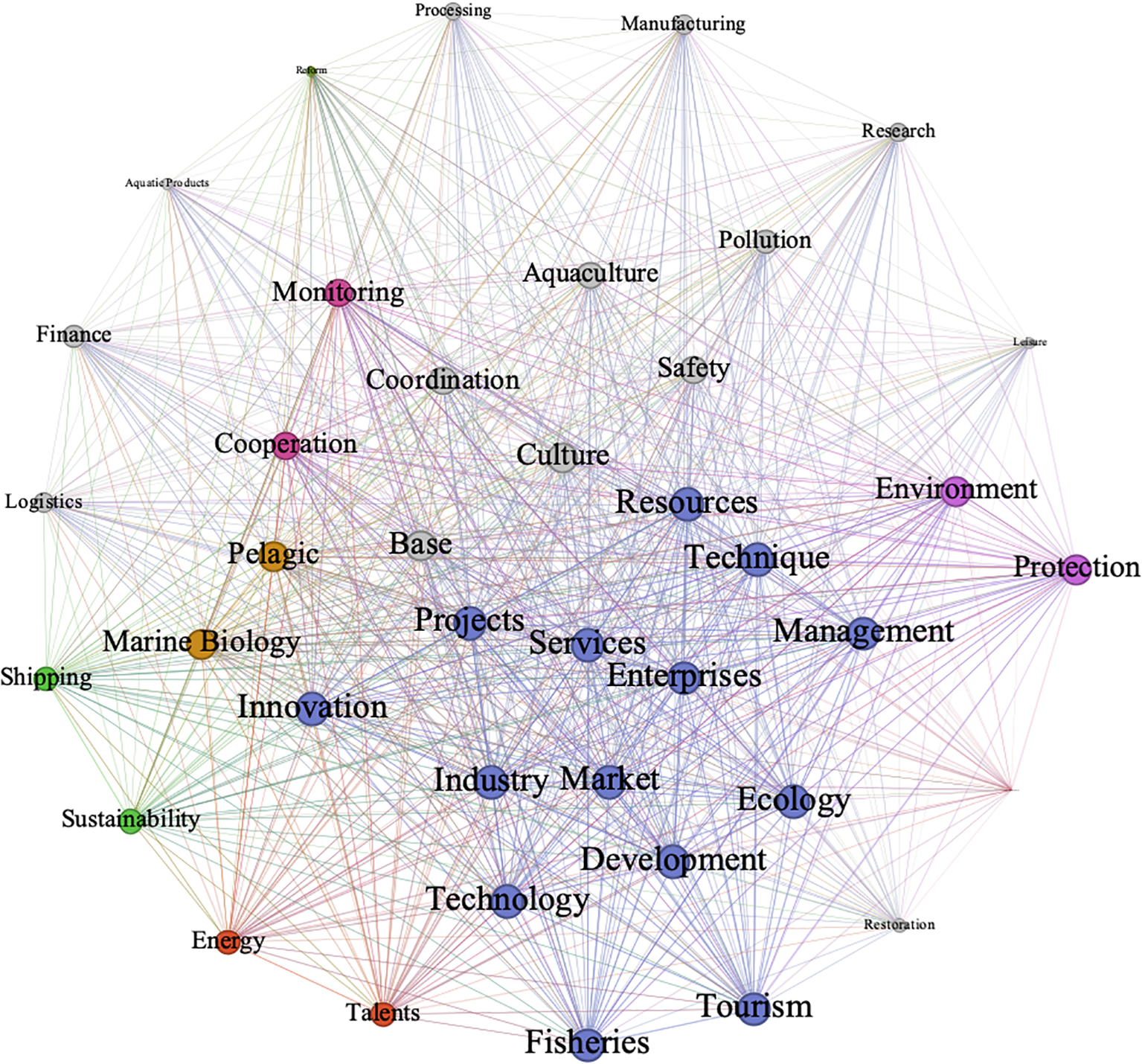

3.3 Extraction and co-occurrence analysis of policy themes

The frequent use of certain terms indicates the focus of policies. In order to grasp the direction of marine economy policies, Nvivo11 software is used to extract policy theme words (Drisko and Maschi, 2016). Initially, the extracted themes are screened to remove common words, irrelevant terms that do not reflect marine economy policies, and low-frequency words such as “ocean,” “national,” “strengthen,” “promote,” etc. Subsequently, a manual screening is conducted to finalize the frequency of terms. This process results in the identification of analysis terms, forming co-occurring policy theme words.

Co-occurrence refers to two policy theme words appearing together in the same policy text. A co-occurrence network is an integral network composed of high-frequency policy themes, where each theme corresponds to a node in the network. The size of the nodes represents the importance of policy hotspots, while the connections between nodes represent the degree of association between policy theme words. The weight of the edges is determined by the frequency of connections, with higher weights indicating stronger associations (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). To avoid duplicating term frequencies, when two policy theme words co-occur in the same text, they are recorded only once, thus forming a policy co-occurrence matrix. In this study, Gephi was used for social network visualization analysis of the co-occurrence matrix, and the results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Co-occurrence network of policy theme words in provincial government marine economy policies.

According to Figure 4, it can be observed that the nodes representing the themes “Industry,” “Development,” and “Projects” have the largest sizes, indicating their significant importance in the overall network. These themes are highly connected to other nodes, suggesting that the development of China’s marine economy primarily focuses on economic growth, particularly in terms of industrial development, project implementation, and technological innovation. Themes such as “Environment,” “Protection,” and “Monitoring” also hold a relatively prominent position, indicating that environmental protection and ecological monitoring are considered key priorities in marine economy policies. The themes “Fisheries,” “Marine Biology,” and “Energy” reflect the attention given to both traditional marine industries and the development of emerging industries within the marine economy. Overall, the analysis suggests that the main focus of marine economy policies is economic development, aiming for diversified industrial growth. However, there is also a secondary emphasis on environmental protection. In summary, the policies are primarily oriented towards promoting industrial development.

Building on the research conclusions, the study further examines the evolution of policies over time by analyzing the key terms emphasized in each policy development period. To provide a clearer observation, the study kicks out particularly high-frequency words such as “development” and “industry” and then chooses the top five most frequently occurring keywords for each period. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Period | Keywords | Period | Keywords | Period | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Marine Economic Growth (2003–2010) | Base, manufacturing, offshore, scientific and technology coordination | Marine-Economic and Environmental Integration(2011-2018) | Environment, pollution, aquaculture, logistics, scientific and technology | Sustainable Marine Economy(2019-2023) | Talent, science, energy, coordination, manufacturing |

Statistical frequency of policy keywords for different periods.

As shown in Table 1, the first stage of policy development primarily focuses on fundamental industrial activities while also emphasizing technological advancement and coordinated development. This reflects the early stage of integrating marine economic development with environmental factors. In the second stage, there is an increasing emphasis on the construction of environmental infrastructure and technological advancements. During this phase, the issue of environmental compensation in the process of economic development begins to be recognized. In the third stage, the focus shifts toward exploring sustainable development pathways, highlighting the use of clean energy, talent cultivation, and further promoting the coordinated development of the marine economy.

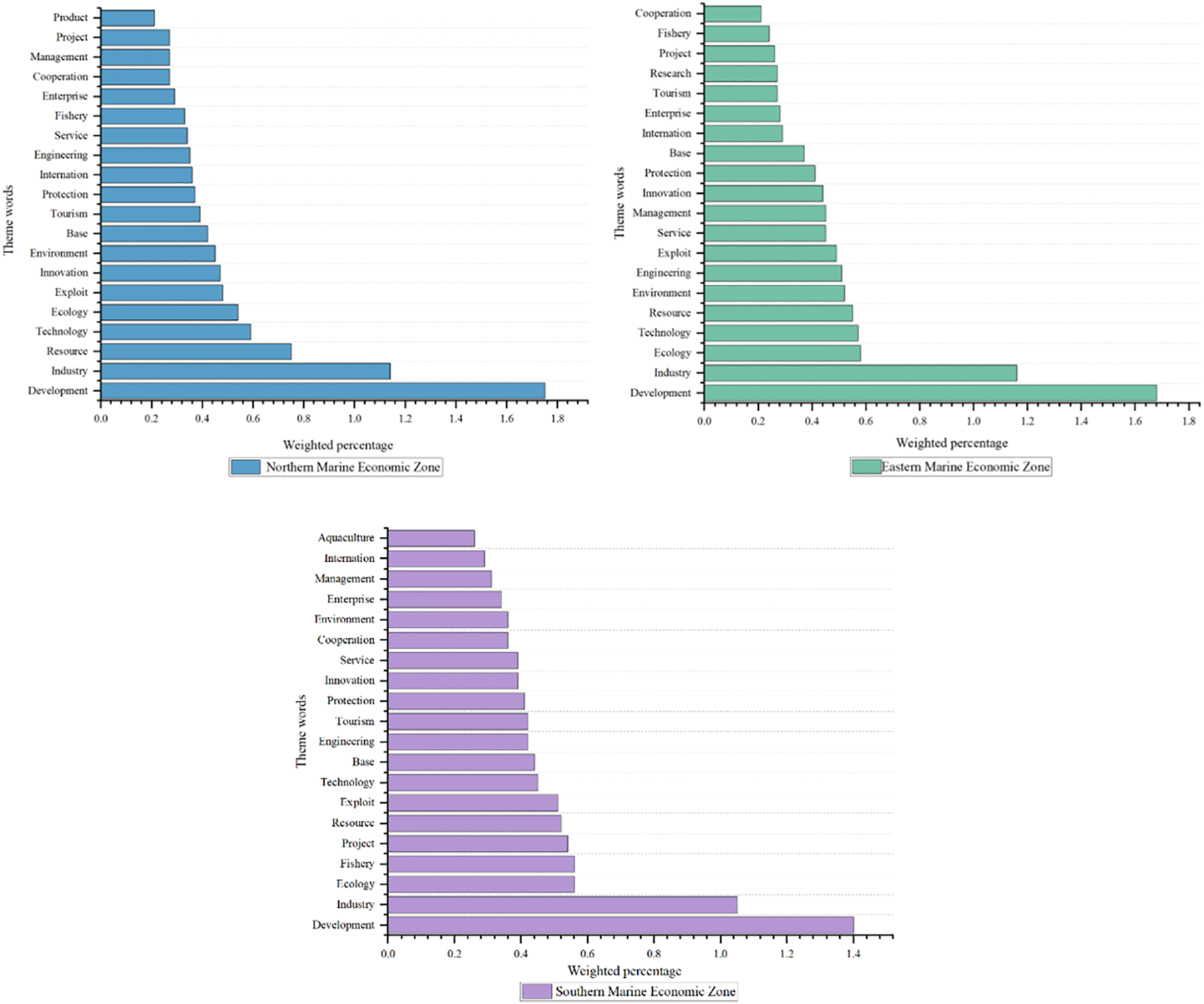

In order to better observe the similarities and differences in policies promulgated by the three marine economic zones, the study further differentiated the policy scope according to regional divisions and organized the theme words of these policies, respectively. Based on this, the top 20 high-frequency keywords in the policies of each marine economic zone were selected for discussion. The weight percentage of the theme words represents their proportion within the policy scope. The results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Policy theme words in three marine economy zones.

Figure 5 displays the high-frequency policy theme words of the three marine economic zones. Overall, the theme words involved are mostly the same, with high frequencies for “development,” “industry,” and “ecology.” This indicates that the policies of regional governments are generally consistent, emphasizing both economic development and ecological protection.

Specifically, in the Northern Marine Economic Zone, in addition to the common high-frequency theme words, “technology,” “development,” and “innovation” play a major role. This is closely related to the zone’s focus on building a highly developed shipbuilding and innovation research base. In the Eastern Marine Economic Zone, the emphasis is on innovation research and development, “industry,” and “services.” This may be due to the larger number of universities, research institutes, and enterprises in this region, as well as higher demands and a higher degree of openness, leading to a more developed maritime trade. Additionally, compared to the other two economic zones, there is less mention of marine tourism and fisheries. In the Southern Marine Economic Zone, it is evident that traditional marine activities such as “fisheries” and “aquaculture” receive more attention. There is also a significant proportion of keywords related to “projects,” “bases,” and “exploit,” followed closely by “tourism,” “services,” and “management.” This region has a more comprehensive consideration of marine economic development in its planning.

4 Quantitative analysis of policy texts

Based on policy tools framework in Chinese marine economy policy constructed in the previous article, this chapter further explores the types and frequency of policy tools adopted by various regions in promoting the development of the blue economy from the perspective of policy texts, analyzes their policy preferences and governance paths, and reveals the institutional basis and evolutionary trends of policy implementation. The use of policy tools reflects the role played by the government in the process of marine economy development and, to some extent, indicates the government’s control over the current direction of marine economy development. The quantitative analysis of policy tools mainly focuses on the number of coding reference points, which can reflect the government’s attention to different aspects of marine economy development. This study examines the frequency and distribution of different policy tools in texts to assess their relative importance and application.

According to the coding results of policy tools (Table 3), environmental policy tools have the highest proportion, accounting for 42.18%. This is followed by supply-oriented policy tools and demand-oriented policy tools, which account for 37.30% and 20.52%, respectively. This indicates that the policy tools used for the development of China’s marine economy mainly rely on environmental policy tools and supply-oriented policy tools, underscoring the critical role of creating a favorable development environment and providing robust government support. This strategic emphasis reflects the government’s focus on fostering a sustainable and resilient marine economy through regulatory frameworks, infrastructure development, and targeted incentives.

Table 3

| Primary node | Secondary node | Source of information | Reference points | Total (Percentage %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply-oriented | Funding Investment | 29 | 54 | 229 (37.30%) |

| Infrastructure Construction | 31 | 76 | ||

| Public Services | 20 | 28 | ||

| Information Support | 26 | 35 | ||

| Human Resources | 32 | 36 | ||

| Demand-oriented | Trade Regulations | 9 | 13 | 126 (20.52%) |

| International Cooperation | 29 | 41 | ||

| Demonstration Projects | 28 | 71 | ||

| Government Procurement | 1 | 1 | ||

| Environment-oriented | Goal Planning | 33 | 45 | 259 (42.18%) |

| Regulatory Measures | 21 | 36 | ||

| Tax Incentives | 14 | 15 | ||

| Financial Support | 33 | 37 | ||

| Strategic Measures | 36 | 126 |

Encoding status of marine economy policy tools.

Looking specifically at the secondary nodes, strategic measures emerge as the most frequently referenced, with 126 coding points. This highlights the government’s proactive approach in formulating and implementing specific measures to ensure the stable and sustainable growth of the marine economy. Such measures often include long-term planning, regulatory frameworks, and institutional reforms aimed at creating a conducive ecosystem for marine economic activities. Infrastructure construction comes next with 76 reference points. Marine infrastructure construction serves as the foundation for the development of the marine economy, providing support for resource development, utilization, and protection. Finally, demonstration projects are also prominently featured, with 71 reference points. These projects are instrumental in promoting innovative marine technologies, sustainable practices, and new business models. By piloting and showcasing successful projects, the government aims to encourage broader adoption of good practices, ensuring the long-term sustainability and effectiveness of marine policies.

In summary, the policy tool distribution reveals a strategic focus on creating a supportive environment and providing foundational resources for the marine economy. However, the relatively lower proportion of demand-oriented policy tools suggests potential opportunities to further stimulate market demand and enhance private sector engagement in the marine economy.

In addition, this study also analyzes the frequency and proportion of different types of marine economy policy tools across various periods. As shown in Table 4, in the first stage of policy development, environment-oriented tools accounted for the largest proportion (43%), followed by supply-oriented tools. In the second stage, supply-oriented tools had the highest proportion (48.3%), as policies during this period focused on supporting national infrastructure development. In the third stage, environment-oriented tools became more prominent (46.6%), with policy types shifting toward persuasive and incentive-based approaches. Throughout the development process, demand-oriented tools consistently maintained the lowest proportion.

Table 4

| Period | Supply-oriented | Demand-oriented | Environment-oriented |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number(%) | Number (%) | |

| Rapid Marine Economic Growth (2003–2010) | 36 (38.7%) | 17 (18.3%) | 40 (43.0%) |

| Marine-Economic and Environmental Integration(2011-2018) | 114 (48.3%) | 42 (17.8%) | 80 (33.9%) |

| Sustainable Marine Economy(2019-2023) | 89 (30.5%) | 67 (22.9%) | 136 (46.6%) |

Statistics frequency of marine economic policy instruments for different periods.

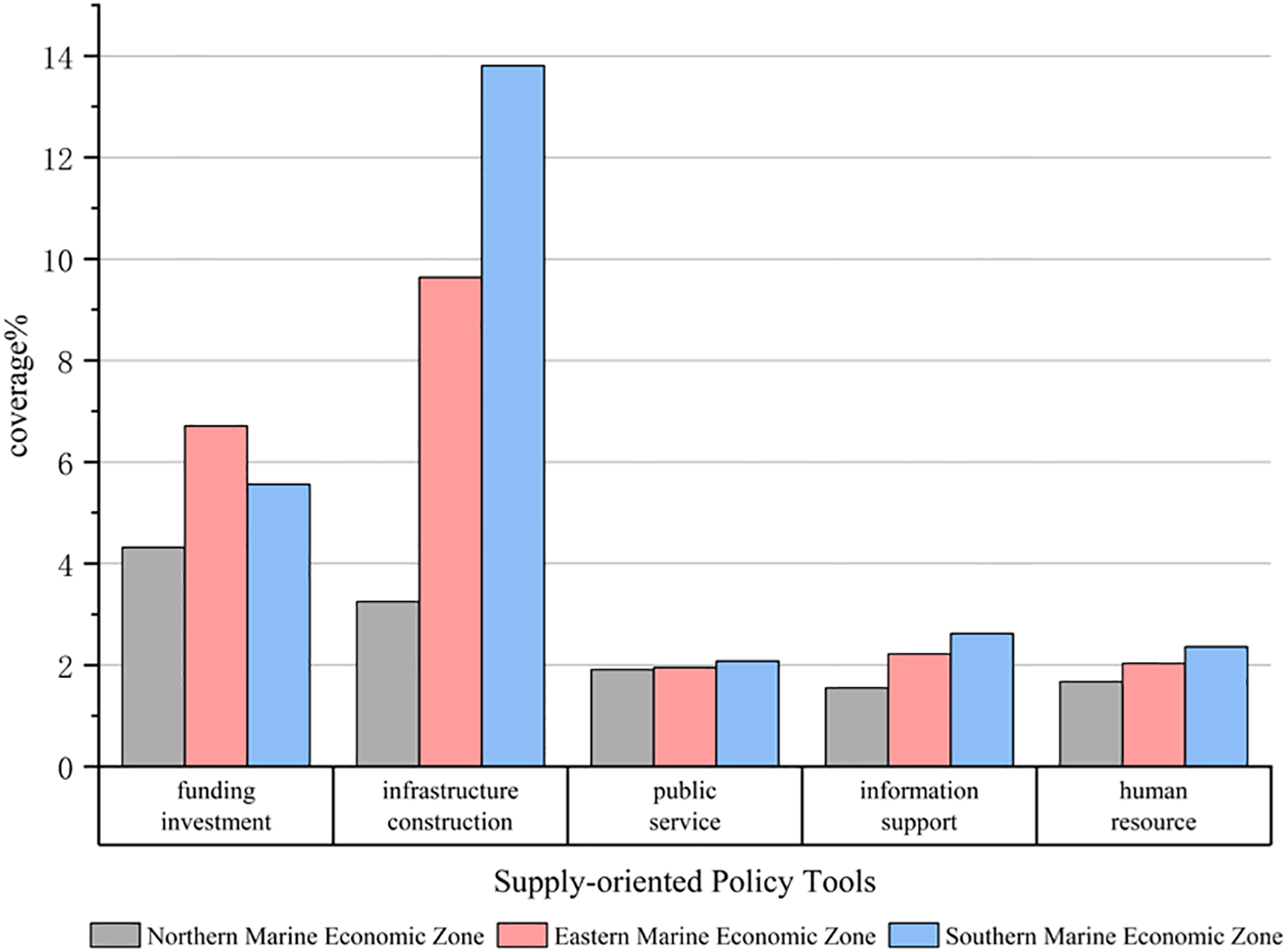

4.1 Analysis of supply-oriented policies

According to Table 3, supply-oriented policy tools account for the second-highest percentage of total nodes. Among the secondary nodes, infrastructure construction has the highest proportion, followed by funding investment. Provincial governments across China have placed significant emphasis on the planning and construction of port infrastructure, marine network monitoring infrastructure, and other related facilities. They prioritize supporting the development of the marine industry and emphasize increasing funding investment. At the same time, governments are actively attracting talent in the marine sector and building “smart ocean” and public service platforms.

Looking at specific zones, as shown in Figure 6, the Eastern Marine Economic Zone and Southern Marine Economic Zone focus more on the development of infrastructure construction. The Northern Marine Economic Zone pays greater attention to government funding investment. Three Zones formulate fewer policies on public service, information support and human resources. Overall, the frequency of using supply-oriented policy tools is relatively lower compared to other categories.

Figure 6

Implementation of supply-oriented policy tools in various marine economic zones.

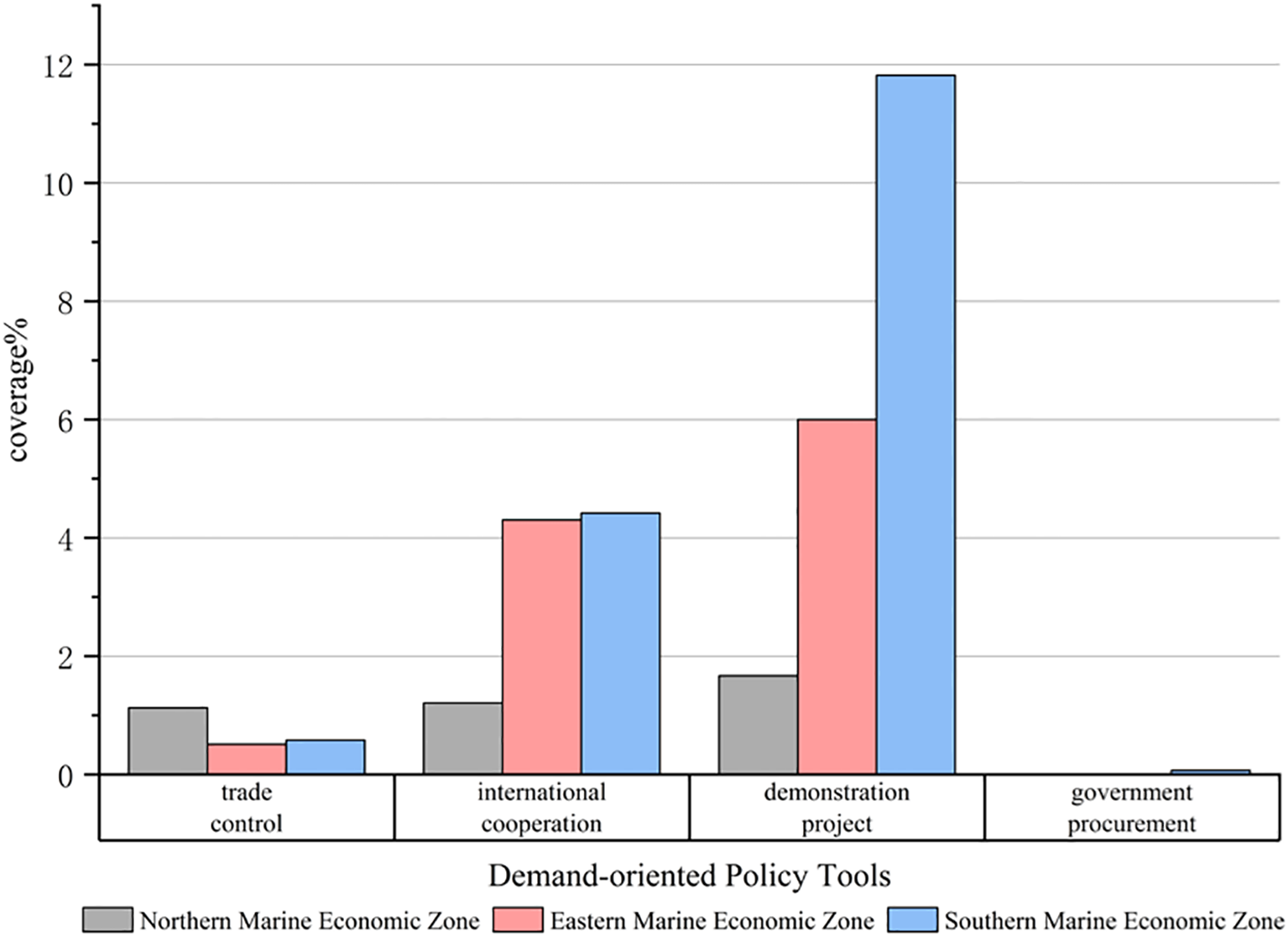

4.2 Analysis of demand-oriented policies

Table 4 indicates that demand-oriented policy tools are utilized relatively less. Among these tools, demonstration projects are mentioned most frequently. Demonstration projects serve as pilot initiatives before the widespread implementation of policies, allowing for the assessment of their feasibility and facilitating scientific adjustments to existing policies. International cooperation is the next most mentioned tool. Active international cooperation contributes to market expansion, technology exchange, and ecological protection, among other aspects. Preferential policies are implemented in foreign trade relations.

From Figure 7, it can be observed that demonstration projects are the most commonly used policy tool in the three major marine economic zones. Compared to the other two economic zones, the Northern Marine Economic Zone also emphasizes external cooperation and import-export control. It has a more balanced use of demand-oriented policy tools. However, government procurement has the lowest frequency of utilization.

Figure 7

Implementation of S demand-oriented policy tools in various marine economic zones.

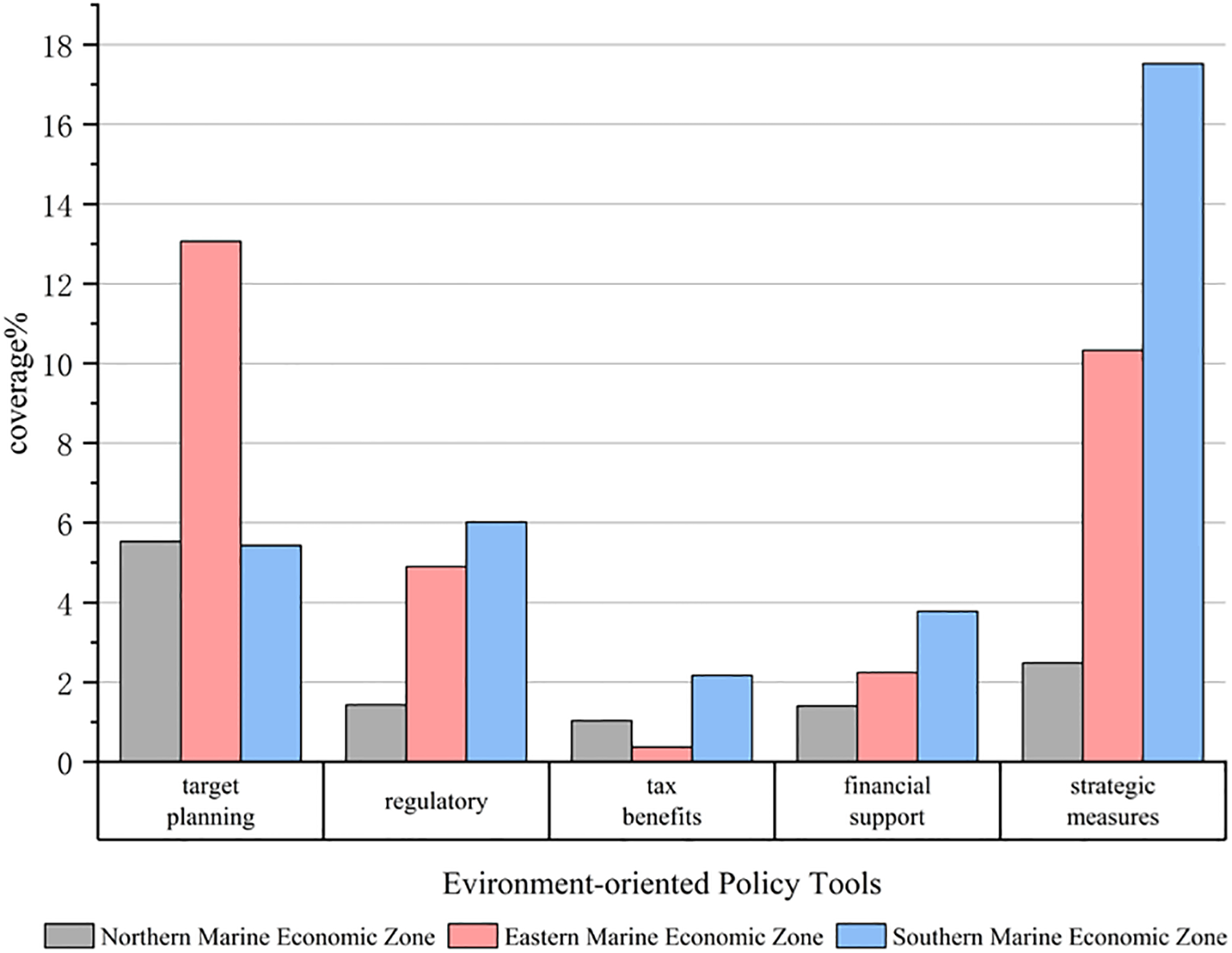

4.3 Analysis of environment-oriented policies

According to Table 4, environment-oriented policy tools have the highest number of nodes. Among the secondary nodes, strategic measures have the highest proportion, followed by target planning, financial support, regulatory measures, and tax incentives. This indicates that governments primarily ensure a favorable environment for the development of the marine economy through regulatory documents, with laws and regulations and financial subsidies serving as supporting tools to achieve development goals.

From Figure 8, it can be observed that there are significant variations in the usage of environmental-based policy tools across the three marine economic zones. The Northern Marine Economic Zone primarily focuses on controlling development direction, utilizing target planning tools and strategic measures. The Southern Marine Economic Zone prioritizes ensuring a developmental environment, relying more on strategic measures. The former also employs regulatory measures to maintain development order, while the latter emphasizes strategic measures and target planning. The Eastern Marine Economic Zone uses targeted planning as its main policy tool but also focuses on the use of strategic measures, combining the strengths of the other two regions. However, it lacks tax benefits.

Figure 8

Implementation of environment-oriented policy tools in various marine economic zones.

Through the analysis above, the study found that the Northern Marine Economic Zone prioritizes supply-oriented policies, followed by environment-oriented policies, and finally, demand-oriented policies. The Eastern and Southern Marine Economic Zones, on the other hand, lean more towards the use of environment-oriented policies, followed by demand-oriented policies, and lastly, supply-oriented policies. Among them, the Southern Marine Economic Zone has the highest policy coverage. There are regional differences in the use of different types of policy tools, which are associated with the geographical location and economic development of the regions.

5 Conclusion and discussion

Nowadays, the development of sustainable marine economy is getting more and more attention. This study comprehends the developmental evolution of marine economic policies in China’s coastal areas. Based on this, the policy text is analyzed in depth. In general, the overall direction of China’s marine economy policies is primarily focused on economic development while also emphasizing the protection and restoration of the marine ecosystem. After conducting a comprehensive and quantitative analysis of the policy texts, the following main conclusions can be drawn:

The theme words in marine economy policies have a certain degree of concentration. Social network analysis reveals the characteristics and meanings of the theme words in the studied policy texts. Words such as “industry,” “development,” “projects,” and “tourism” emphasize the development of emerging marine industries. Words like “talent,” “research,” and “science” highlight the importation and training of talent to better serve marine technological research. At the same time, words such as “environment,” “ecology,” and “protection” underscore the governance and protection of the marine ecosystem. Overall, the policies are oriented towards industrial development, supplemented by environmental governance mechanisms. In addition, policy directions for development have varied in different periods, from the concept of development as a first priority to the current concept of sustainable and coordinated development. Specifically, from the policies of the three marine economic zones, there are also differences and similarities in the key themes and their frequencies. In order to better observe the policy direction, the article selected the top 20 themes in the three regions for analysis. The study found that “Development” and “Industry” are the high-frequency policy words in the three regions, indicating that the policies still focus on industrial development. At the same time, the high frequency of “Ecology”, “Environment”, and “Protection” also reflects the policy’s efforts in environmental protection. On this judgment, the policy tendencies of the three regions are also significantly different. The Northern Marine Economic Zone focuses on the development of innovative technologies and resource development, which is also in line with its characteristics as an innovation and construction base. In addition, “Tourism”, “Engineering” and “Fishery” are also important directions of development. The high-frequency policy words of the Eastern Marine Economic Zone tend to be “Technology”, “Engineering”, and “Service”, and compared to the other two regions’ emphasis on traditional fisheries, the eastern region pays more attention to R&D projects and technological innovation. Among the policy themes of the Southern Marine Economic Zone, traditional fishery activities (“Fishery”, “Aquaculture”) are important high-frequency words, and the frequencies of themes such as project development (“Project”, “Base”, “Exploit”) and technological innovation (“Technology”, “Innovation”) all show that the marine economy and ecological environment development in this region is the most balanced.

In the context of promoting a sustainable blue economy, policy tools play distinct yet complementary roles. Supply-oriented tools provide the foundational capacities needed for SBE development—for instance, infrastructure investments in green ports and marine observation stations, as well as R&D funding for renewable marine energy and ecological aquaculture. Demand-oriented tools stimulate market engagement through mechanisms such as public procurement of green marine products, pilot demonstration zones, and international cooperation in marine governance. Meanwhile, environment-oriented tools—including regulatory measures, strategic planning instruments, and fiscal incentives—offer the institutional framework that supports long-term sustainability. These three categories of tools together form a holistic toolkit that enables governments to promote economic development while maintaining marine ecological integrity. In this study, both as a whole and in different time periods, there is an imbalance in the use of marine economy policy tools. Currently, implemented policy tools are predominantly environmental in nature, followed by supply-oriented tools, with a severe lack of demand-oriented policy tools. When examining the three types of policy tools in detail, there are also internal imbalances in their proportions. Strategic measures dominate the environmental-oriented policy tools, indicating that the government recognizes the need to ensure the development of the marine economy but lacks specific policy support and legal documents. In the supply-oriented policy tools, more emphasis is placed on infrastructure construction and funding investment, with the least proportion allocated to the development of public service platforms. In demand-oriented policy tools, there is a lack of proportionate coordination between government procurement and trade regulations, which may result in the effectiveness of complementary measures falling below expectations. There are also internal imbalances in the selection of policy tools among different economic zones, leading to significant differences. Compared to the other two regions, the Northern Marine Economic Zone utilizes more supply-oriented policy tools, with a tendency towards government-issued orders and autonomous actions. The other two regions, on the other hand, mainly adopt environmental-oriented policy tools, focusing more on the application of auxiliary measures.

Based on the above conclusion and further analysis, the policy formulation for the three marine economic zones needs to grasp the overall direction of coordinated economic and ecological development, while considering the specific conditions of each region to develop effective and targeted policies that will lead to balanced regional development. Thus, the formulation of ocean economy policies can strive towards some directions. As a whole, while optimizing traditional marine industries, proactive efforts should be made to introduce and develop new technologies and models, with a focus on the use and development of clean marine energy to alleviate environmental issues. And government investment and construction should be encouraged to establish platforms and centers for ocean development and environmental governance, involving participation from businesses and individuals. When formulating policies, the government should consciously adjust the proportion of policy tools used and emphasize the diverse application of various policies. Efforts should be made to increase the procurement of new technologies, clean energy facilities, etc., and establish trade control measures that benefit the people. Furthermore, within the supply-oriented policy tools, emphasis should be placed on the construction of public service platforms, promoting resource exchange and information sharing among participants in the ocean economy. Additionally, the government can collect information in a timely manner to facilitate the adjustment and optimization of existing policies. Lastly, the utilization of strategic measures should be further studied and refined, and the government should introduce corresponding supporting measures and normative documents. From the perspective of marine economic regions, the northern region should strengthen technological innovation and the transformation of achievements, accelerating the clustering of marine technology industries. The Qingdao area has established research centers for marine medicine and technology, leveraging local universities. Additionally, it is essential to optimize the application of supply-oriented and demand-oriented tools, which can include implementing fishery subsidies and increasing investment in public service platforms. The eastern region should maintain its advantage in technological innovation, utilizing its abundant talent and industrial resources to build a technology transformation cluster. At the same time, it should effectively use demand-oriented tools and enhance coordinated governance within the region. In the southern region, traditional fisheries and project development coexist, but there is an imbalance in the use of policy tools. This region can leverage its rich marine carbon sink resources for pilot projects, improve the supporting use of demand-oriented tools, and promote the green development of traditional fisheries.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ZY: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1553962/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Admin O. (2020). Blue economy (The Ocean Foundation, The Ocean Foundation). Available online at: https://oceanfdn.org/zh-CN/%E8%93%9D%E8%89%B2%E7%BB%8F%E6%B5%8E/.

2

(2024). People’s Daily Overseas Edition, China’s marine economy is recovering strongly. Available online at: http://www.news.cn/fortune/20240326/6e61e0c93d4443889d88177fdd3a9349/c.html (Accessed January 23, 2024)

3

Bari A. (2017). Our oceans and the blue economy: opportunities and challenges. Proc. Eng.194, 5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2017.08.109

4

Bennett N. J. Cisneros-Montemayor A. M. Blythe J. Silver J. J. Singh G. Andrews N. et al . (2019). Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nat. Sustain2, 991–993. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0404-1

5

Capano G. Howlett M. (2020). The knowns and unknowns of policy instrument analysis: policy tools and the current research agenda on policy mixes. SAGE Open10, 2158244019900568. doi: 10.1177/2158244019900568

6

Choudhary P. G V. S. Khade M. Savant S. Musale A. G R. K. K. et al . (2021). Empowering blue economy: From underrated ecosystem to sustainable industry. J. Environ. Manage.291, 112697. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112697

7

Chu Van T. Ramirez J. Rainey T. Ristovski Z. Brown R. J. (2019). Global impacts of recent IMO regulations on marine fuel oil refining processes and ship emissions. Transportation Res. Part D70, 123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2019.04.001

8

Clark C. W. Munro G. R. Sumaila U. R. (2005). Subsidies, buybacks, and sustainable fisheries. J. Environ. Economics Manage.50, 47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2004.11.002

9

Cormier R. Elliott M. (2017). SMART marine goals, targets and management – Is SDG 14 operational or aspirational, is ‘Life Below Water’ sinking or swimming? Mar. pollut. Bull.123, 28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.07.060

10

Daoji L. Daler D. (2004). Ocean pollution from land-based sources: East China sea. China Ambio33, 107–113. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-33.1.107

11

Derraik J. G. B. (2002). The pollution of the marine environment by plastic debris: a review. Mar. pollut. Bull.44, 842–852. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00220-5

12

Drisko J. W. Maschi T. (2016). Content Analysis (Oxford University Press).

13

Elo S. Kyngäs H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Advanced Nurs.62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

14

González-Wangüemert M. Domínguez-Godino J. A. Cánovas F. (2018). The fast development of sea cucumber fisheries in the Mediterranean and NE Atlantic waters: From a new marine resource to its over-exploitation. Ocean Coast. Manage.151, 165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.10.002

15

Hendriks I. E. Duarte C. M. Álvarez M. (2010). Vulnerability of marine biodiversity to ocean acidification: A meta-analysis. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.86, 157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2009.11.022

16

Hobday A. J. Tegner M. J. Haaker P. L. (2000). Over-exploitation of a broadcast spawning marine invertebrate: Decline of the white abalone. Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries10, 493–514. doi: 10.1023/A:1012274101311

17

Katsanevakis S. Stelzenmüller V. South A. Sørensen T. K. Jones P. J. Kerr S. et al . (2011). Ecosystem-based marine spatial management: review of concepts, policies, tools, and critical issues. Ocean Coast. Manage.54, 807–820. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.09.002

18

Kleinheksel A. J. Rockich-Winston N. Tawfik H. Wyatt T. R. (2020). Demystifying content analysis. Am. J. Pharm. Educ.84, 7113. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7113

19

Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Available online at: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130282272640086912 (Accessed January 23, 2024).

20

Lakeman R. (2008). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs.15, 868–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01257.x

21

Lowi T. J. (1972). Four systems of policy. Politics Choice Public Administration Rev.32, 298–310. doi: 10.2307/974990

22

McIlgorm A. Raubenheimer K. McIlgorm D. E. Nichols R. (2022). The cost of marine litter damage to the global marine economy: Insights from the Asia-Pacific into prevention and the cost of inaction. Mar. pollut. Bull.174, 113167. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.113167

23

Morrissey K. O’Donoghue C. (2012). The Irish marine economy and regional development. Mar. Policy36, 358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2011.06.011

24

Novaglio C. Bax N. Boschetti F. Emad G. R. Frusher S. Fullbrook L. et al . (2022). Deep aspirations: towards a sustainable offshore Blue Economy. Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries32, 209–230. doi: 10.1007/s11160-020-09628-6

25

Pace L. A. Saritas O. Deidun A. (2023). Exploring future research and innovation directions for a sustainable blue economy. Mar. Policy148, 105433. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105433

26

Qin M. Yue C. Du Y. (2020). Evolution of China’s marine ranching policy based on the perspective of policy tools. Mar. Policy117, 103941. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103941

27

Schneider A. Ingram H. (1990). Behavioral assumptions of policy tools. J. Politics52, 510–529. doi: 10.2307/2131904

28

Scott J. (2012). What is social network analysis? Bloomsbury Acad, 114. doi: 10.5040/9781849668187

29

Smith V. H. Joye S. B. Howarth R. W. (2006). Eutrophication of freshwater and marine ecosystems. Limnology Oceanography51, 351–355. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.1_part_2.0351

30

Spalding M. J. (2016). The new blue economy: the future of sustainability. J. Ocean Coast. Economics2(2), 8. doi: 10.15351/2373-8456.1052

31

Stephenson R. L. Hobday A. J. (2024). Blueprint for blue economy implementation. Mar. Policy163, 106129. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106129

32

Sun J. Miao J. Mu H. Xu J. Zhai N. (2022). Sustainable development in marine economy: Assessing carrying capacity of Shandong province in China. Ocean Coast. Manage.216, 105981. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105981

33

Vierros M. De Fontaubert C. (2017). The potential of the blue economy : increasing long-term benefits of the sustainable use of marine resources for small island developing states and coastal least developed countries. Available online at: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1509557/the-potential-of-the-blue-economy/2177713/ (Accessed January 23, 2024).

34

Wang S. Xing L. Chen H. (2019). Impact of marine industrial structure on environmental efficiency. Manage. Environ. Qual.31, 111–129. doi: 10.1108/MEQ-06-2019-0119

35

Wasserman S. Faust K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications (Cambridge University Press).

36

Web-Chinese D Sustainability development goals, Sustainability development. Available online at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/zh/sustainable-development-goals/ (Accessed January 23, 2024).

37

Xinhua Y. (2022). Towards Blue Transformation: Aquaculture in a changing world (FAO Aquaculture Newsletter), II–III.

38

Yan X. Yan L. Yao X.-L. Liao M. (2015). The marine industrial competitiveness of blue economic regions in China. Mar. Policy62, 153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.09.015

39

Yang X. Liu N. Zhang P. Guo Z. Ma C. Hu P. et al . (2019). The current state of marine renewable energy policy in China. Mar. Policy100, 334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.11.038

40

Zhang W. Chang Y. C. Zhang L. (2020). An ocean community with a shared future: Conference report. Mar. Policy116, 103888. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103888

41

Zhao R. Hynes S. Shun He G. (2014). Defining and quantifying China’s ocean economy. Mar. Policy43, 164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.05.008

Summary

Keywords

marine economy, sustainable blue economy, policy tools, social network, content analysis

Citation

Shen C, Yang Z and Zhan J (2025) Analysis of China’s marine economic policy: regional policy characteristics, evolution and assessment. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1553962. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1553962

Received

07 January 2025

Accepted

29 July 2025

Published

15 August 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Di Jin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, United States

Reviewed by

Hu Zhang, East China University of Political Science and Law, China

Wenjie Zou, Fujian Normal University, China

Zacharoula Kyriazi, University College Cork, Ireland

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Shen, Yang and Zhan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhenjie Yang, zjyang@mpu.edu.mo

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.