- School of Law, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China

Considering the fast development of Chinese deep-sea archaeology and the pressing situation of underwater cultural heritage (UCH), China’s legislation for UCH was revised again in 2022. This revision underwent a nine-year-long, arduous drafting process, but it has received little scholarly attention. This study explores the history of the revision via the comparison of four relevant legal documents to show the evolution of Chinese UCH legislation. The issues of most concern for China in the revision are the distribution of UCH responsibilities among different institutions, public participation, protection measures and international cooperation regarding UCH. In terms of the distance between Chinese legislation and the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, three different types of evolution tendencies appeared in the revision history. First, China’s legislation moved continuously closer to the Convention, and this tendency is reflected in the issues of public participation, international cooperation and the distribution of UCH responsibilities. Second, with respect to protection measures, China’s law showed a hesitant tendency, as China’s legislation once moved closer to the Convention but eventually retrogressed. Third, with respect to the definition and ownership-based jurisdiction of UCH, China’s legislation did not make substantial changes and remained consistently far from the Convention. To explain the dynamic and arduous revision history, influencing factors in the “pull” and “push” directions are identified. The shift from a state-led protection model to an integrated model and the international context pushed China closer to the Convention, while the consideration of economic development and institutional conflicts pulled China back. Consequently, China ultimately made a compromise in 2022.

1 Introduction

With the rapid development of deep-water technology and water acidification, the protection of underwater cultural heritage (UCH) has come to a new pressing situation (Browne and Raff, 2022; Ward, 2023). In 2001, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) adopted the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (2001 Convention) (UNESCO, 2001). The 2001 Convention lays down international legal grounds for UCH protection, and it has been signed by 79 states to date.1 As a traditional maritime power, China has made tremendous progress in underwater archaeological technologies. Two days before the year of 2025, China’s deep-sea cultural relic archaeology added another “heavy weapon” - the scientific research ship Exploration No.3 - officially commissioned in Sanya, and the ship was expected to carry out scientific research and archaeological operations in 2025 (Xinhua News Agency, 2024a). Technological advance drives legal improvement. Since China is not a party to the 2001 Convention, it relies mainly on domestic law to protect and manage UCH. In recent years, China has made remarkable achievements in the protection of UCH, and a notable aspect is the development of UCH legislation and policies (Jing, 2019). Although the relevant Chinese law is domestic by nature, it has a de facto international dimension. One reason is that China prioritizes UCH protection in coastal regions, such as the South China Sea, over protection in internal waters, and this unavoidably leads to far-reaching impacts on neighboring countries. Another reason is that China endows UCH with strong international policy implications. In China’s 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative, for instance, UCH plays an important role in increasing cultural connections and cultivating the common cultural identities of the involved countries (Zhong, 2020). As China’s domestic UCH law has been applied in solving high-profile disputes in coastal regions and has shaped China’s approach to international cooperation, further research is needed on this topic.

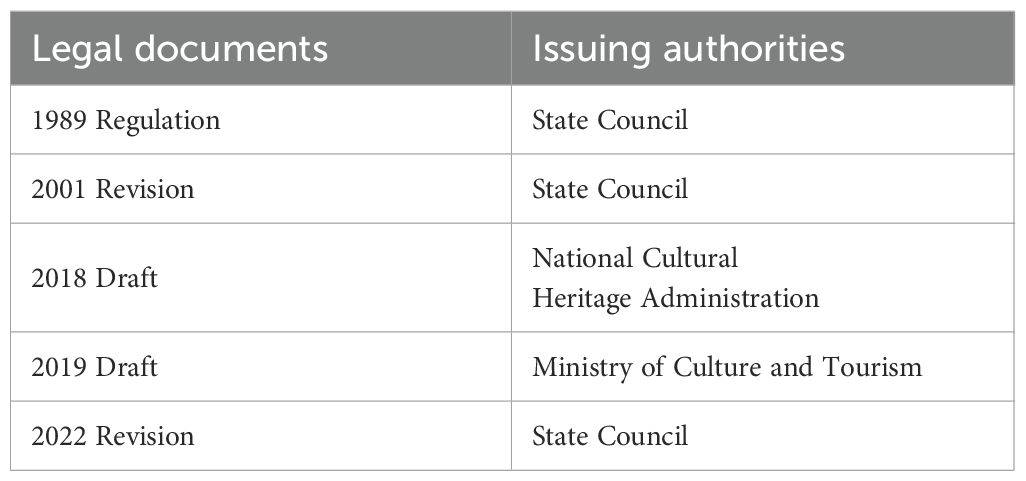

China has developed and constantly improved the legal framework for UCH over the past four decades. The legislative history began in the 1980s with the Geldermalsen case. The Geldermalsen was a sunk ship from the Dutch East India Company. It was discovered in the South China Sea and found to carry many valuable porcelains produced in China. However, the Chinese government could not find any legal ground in international or domestic law to effectively claim the return of the treasures (Jing, 2019; Lu and Zhou, 2016). Stimulated by the Geldermalsen case, China initiated UCH legislative work. The Regulation on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics was passed in 1989 (1989 Regulation).2 In 2011, the 1989 Regulation was revised for the first time (2011 Revision),3 but the revision did not involve any substantive content modification. The 2011 Revision, which substantively retained the status quo of the 1989 Regulation, was deemed incapable of adapting to the new situation of UCH protection, and the Chinese government thus decided to further revise the regulation.4 In 2013, the revision work was listed in the legislative work plan of the State Council as an item in need of active research.5 In 2016, the Guiding Opinions on Further Strengthening the Work of Cultural Relics issued by the State Council required the acceleration of the work on revising the UCH regulation.6 In the revision process, three important legal documents were issued in 2018, 2019 and 2022. The first revision draft was proposed by the National Cultural Heritage Administration (NCHA) in 2018 (2018 Draft).7 After receiving public comments, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, which assumes management responsibility over the NCHA, submitted a second draft for the review of the State Council, and the draft was published in 2019 (2019 Draft).8 In 2022, the State Council approved the revision (2022 Revision).9 The 2022 Revision introduces substantial alterations to the 2011 Revision, building a more scientific, professional, and operable legal framework (Jiang, 2022). These legislative efforts as a whole demonstrate China’s strong determinations for improving UCH protection and management (See Table 1).

2 Research design, materials and methods

China is not one of the most commonly studied regions in UCH research (Bulut and Yüceer, 2023). Among the limited number of China-related works, some focus on specific UCH disputes, such as the ownership or protection activities of UCH in the South China Sea (Jing and Li, 2019; Zhong, 2020). Other studies review the legislation and implementation of the Chinese UCH regime, highlight recent developments, and propose suggestions for improvement (Jing, 2019; Li and Chang, 2023; Lin, 2023; Wang and Li, 2024). Most current studies mention the 2022 Revision as the latest update of Chinese law and focus on its legal provisions but overlook its legislative history. Notably, the 2022 Revision underwent a long, arduous and dynamic drafting process of almost 9 years. As this article shows, some important clauses changed greatly or even underwent back and forth changes during the drafting process, demonstrating the controversy regarding essential issues of UCH protection and China’s hesitation in choosing sides.

This research seeks to bridge the gap in the current UCH literature by examining the legislative history of China’s latest revision of the UCH regulation. The drafting history offers valuable material for understanding the different standings and underlying concerns of China. The methodologies adopted by this research are legal research and comparative analysis. In the article, four legal documents that are important to the revision of China’s UCH law are compared, i.e., the original 2011 Revision, the 2018 Draft, the 2019 Draft, and the finalized 2022 Revision, in chronological order to draw a full picture of the legal evolution. Specifically, this research addresses the following questions. First, what were the most concerning issues for China among the revisions; i.e., which clauses were changed greatly or changed back and forth in the revision process? Second, as China claims to be a practitioner of the spirit of the 2001 Convention even though it is currently not a party to the Convention (Fan, 2014), has China’s UCH law moved closer to or farther from the 2001 Convention? Third, what factors influence the distance between China’s revision and the 2001 Convention?

This is the first research that comprehensively examines the legislative history of China’s 2022 Revision by comparing four relevant legislative documents to reveal the evolution tendency of Chinese UCH legislation. Importantly, this research differentiates three types of evolution tendencies shown in the revision history and unveils the underlying considerations that influenced China’s legal choice. These findings help predict the future development of China’s UCH policy. Moreover, this study summarizes China’s experience in the development of UCH legislation. For the protection of UCH, states may have different focuses or take different approaches, such as considering UCH protection in maritime spatial planning (Papageorgiou, 2018), using advanced scientific technologies for underwater archaeological prospection (Janowski et al., 2024), or establishing administrative bodies and associations to document and preserve UCH (Calantropio and Chiabrando, 2023), and China’s experience presents a possible complementary option to other countries’ existing approaches. Instead of acceding to the 2001 Convention, China has adopted a domestic law approach, under which China gradually embraces the principles of the 2001 Convention while maintaining distinctions to meet China’s specific economic and institutional demands. China’s approach provides important implications for other countries, such as those that are reluctant to accede to the 2001 Convention but resort to domestic law to protect UCH, or those that need to balance the protection of UCH and the development of the marine economy.

Research results are presented in the following structure. Based on comparative analysis, this research finds that the draft clauses of China’s UCH regulation changed to varying degrees during the revision process. While certain clauses remained almost unchanged or were modified slightly, there are also clauses that underwent significant changes. In particular, the provisions regarding the distribution of UCH responsibilities among different institutions, public participation, protection measures for UCH, and international cooperation were changed greatly or changed back and forth, suggesting that these are the areas of focus or even the issues of controversy in the legislation. Section 3 therefore examines the legal evolution of the four key points. As the distance between Chinese UCH law and the 2001 Convention changed dynamically in the different stages of the legislative process, Section 4 assesses the dynamic distance and observes three different types of evolution tendencies; i.e., Chinese UCH law 1) moved continuously closer, 2) approached once but finally became more distanced, or 3) remained consistently far from the stance of the 2001 Convention. To explain the dynamic and complex revision process, Section 5 identifies “push” and “pull” factors that influenced China’s distance from the 2001 Convention. Concluding remarks are given at the end.

3 Key points of the revision: comparative analysis

3.1 Distribution of responsibilities for UCH protection

In the original 2011 Revision, with respect to the distribution of responsibilities for UCH protection among different institutions, Article 4 provides the following: the NCHA is responsible for the registration of UCH, the protection and administration of UCH, and the approval of archaeological exploration and excavation activities; local administrative departments for cultural relics are in charge of the protection of UCH in their regions and, in conjunction with archaeological and research institutions for cultural heritage, are responsible for the identification and value assessment of UCH. The distribution of responsibilities was based on specific matters, and many important UCH matters were retained at the state level, i.e., the NCHA. However, such a state-centered distribution caused the NCHA to become overloaded in terms of both regulatory competency and budget pressures. In the meantime, with such vague provisions, it was difficult to determine which specific level of local cultural relic department should assume UCH responsibility, which weakened UCH protection in local regions.

In the 2022 Revision, the new Article 4 advanced in two aspects. First, the competence boundary between the central and local levels was reestablished in a territory-based manner rather than a matter-based manner. As Article 4 states, the competent cultural relic department of the State Council (i.e., the NCHA) is responsible for UCH protection work nationwide; the competent cultural relic departments of local governments at and above the county level are responsible for UCH protection work in their respective administrative regions. The new arrangement vertically decentralizes UCH protection responsibility from the central level to specific local levels, which balances the asymmetric regulatory pressure caused by traditional Chinese centralism and enables UCH protection to be carried out on a local basis. For a second development, Article 4 for the first time specifies the horizontal distribution of UCH responsibilities. In practice, UCH protection may involve different departments, such as the police department or the maritime law enforcement department. However, the 2011 Revision did not mention the horizontal division of labor among departments. The new Article 4 closed this loophole by providing that relevant departments of local governments are responsible for the work concerning UCH protection within their respective scope of responsibilities. Therefore, the 2022 Revision shows tendencies towards vertical decentralization and horizontal collaboration in terms of institutional arrangements.

In the 2018 Draft and 2019 Draft, two changes concerning the decentralization tendency are noteworthy. The first change concerns the degree of decentralization. A prominent difference between the two drafts and the 2022 Revision is that the two drafts did not limit the UCH work to local governments at and above the county level, indicating that local governments at all levels, including governments below the county level (such as town-level governments), are responsible for the conservation of UCH in their regions. However, the 2022 Revision finally excluded governments below the county level from the UCH institutional arrangement. The exclusion, which curbed radical decentralization, is understandable for realistic considerations, as town-level governments usually do not have the necessary capability or sufficient resources to address UCH matters. The second change concerns which institution assumes responsibility for the local protection of UCH, either “local governments” or “the cultural relic departments of local governments”. In the two drafts, local governments were designated to be in charge of local UCH work, but the 2022 Revision finally assigned the responsibility to the cultural relic departments of local governments. The authors believe that such a change is a reasonable move, especially against the background of the Chinese administrative hierarchy. The 2018 Draft is taken for illustration. As drafted in 2018, local governments were in charge of the UCH work in their regions, and the cultural relic department of the State Council (i.e., the NCHA) assumed the responsibility of guiding, supervising and inspecting the UCH work conducted by local governments.10 Under the Chinese administrative hierarchy, however, the NCHA is at the bureau level, whereas a local government might be located at a higher level than the NCHA since the government of a province is at the provincial and ministerial level. The institutional design in the 2018 Draft would have led to practical difficulty in enforcement: how could the NCHA supervise and inspect the UCH work conducted by the local governments of provinces, which are at a higher administrative level? The 2022 Revision solved this hierarchical problem by directly designating “the cultural relic departments of local governments” the responsibility body of local UCH work. In summary, the 2022 Revision rationalizes the institutional arrangement for UCH protection and clarifies the responsibilities of specific institutions, which is regarded as a highlight of the 2022 Revision by commentators (Cui, 2022; People’s Daily, 2022).

3.2 Public participation

In the 2011 Revision, public participation was implicitly reflected in certain clauses. For example, as Article 6 provided, any entities or individuals who have discovered UCH by any means should report promptly to the competent cultural relic authorities. Despite that, the authors observe that public participation was largely overlooked in the 2011 Revision and embodied in scattered clauses only. This is probably because China mainly depended on governments, rather than the public, to protect UCH and formed a state-led model for UCH (Lu and Zhou, 2016).

However, in the revision process, China clearly injected more elements of public participation. In the 2018 Draft, a specialized clause was introduced, i.e., Article 15, which states that to the extent that the safety of relevant people and UCH is ensured, underwater historical cultural relic parks can be built. This clause was intended to improve the public recognition of UCH and facilitate the development of UCH tourism. The 2019 Draft retained this clause with no major modifications.11

Furthermore, many new clauses concerning public participation were introduced into the 2022 Revision, and these clauses focus on different dimensions of UCH public participation. First, the 2022 Revision adds a general principle that sets the tone of encouraging public participation; i.e., Article 5 not only requires local governments to highlight UCH protection and ensure UCH safety but also imposes the obligation to protect UCH on any entity and any individual. Notably, the clause explicitly recognizes the important role that individuals can play in UCH protection, which activates the enthusiasm and resources of individuals to protect UCH. Second, regarding the discovery of UCH, Article 9 almost completely retains the reporting and submission obligations laid down by the 2011 Revision, with the addition of outlining the obligations of the competent authorities when they receive reports of the discovery of UCH. The authorities are obligated to rush to the scene within 24 hours, immediately take measures to protect the scene, and conduct rescue protection. Third, regarding the public promotion of UCH, Article 16 further improves the relevant clause of the 2018 Draft. Article 16 provides that the competent cultural relic departments should, through organizing exhibitions, visits, scientific research and other means, fully maximize the role of UCH, strengthen the publicity and education regarding excellent traditional Chinese culture and the legal system for UCH protection, improve the awareness of the whole society for UCH protection, and increase the public enthusiasm for participating in the protection of UCH. Compared with the relevant clause in the 2018 Draft,12 Article 16 in the 2022 Revision does not limit public participation to the establishment of UCH parks but offers broader and flexible ways. Fourth, the 2022 Revision establishes a new public reporting channel under Article 18. Any entity or individual has the right to report to the competent authorities any act that violates the UCH rules or endangers the safety of UCH. The competent authorities are required to establish a public reporting channel, disclose the channel to the public, and handle relevant reports in a timely manner.13 This provision enables the discovery of violations of UCH law through public participation, increasing the enforceability and deterrence of UCH law.

Overall, the importance of public participation significantly increased throughout the revision process. This is an improvement of the Chinese UCH law in terms of its international vision, as the revision is consistent with the 2001 Convention’s emphasis on “public awareness”, commented by Bo Jiang, Vice President of the International Council on Monuments and Sites and Professor at Shandong University, who participated in the revision process (Jiang, 2022).

3.3 Protection measures

Protection measures for UCH constitute the core of a UCH regime. As the authors observe, legislative measures for UCH protection, especially the clauses concerning the in situ preservation of UCH and prohibited activities for UCH, represent the most controversial issue in the revision process.

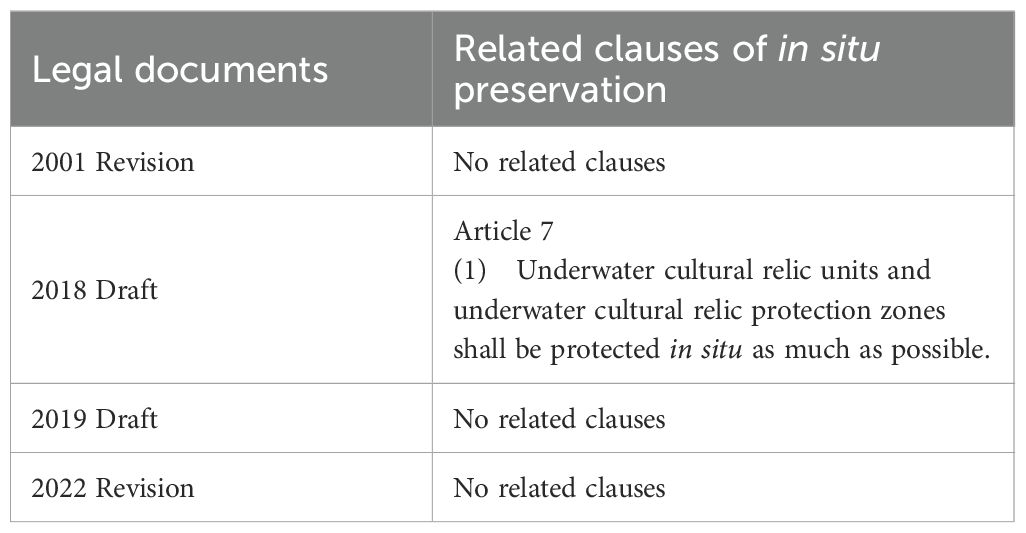

3.3.1 Preservation in situ of UCH

The first controversy is the acceptance of in situ preservation as a priority principle. According to the 2001 Convention, in situ preservation is considered the first option for protecting UCH.14 However, China did not write this principle into the 2011 Revision. As China’s past UCH protection experiences show, there are very few examples of in situ preservation, while on many occasions, important underwater cultural relics have been salvaged by governments. The best case of in situ preservation to date is the Ridge of White Crane (Baiheliang), which was built into an underwater museum in situ (Xinhua News Agency, 2024b). China’s reluctance to embrace in situ preservation as a priority causes concerns because in situ preservation is recognized as the best way to preserve the integral value and contextual information of UCH (Aznar, 2018; Lu and Zhou, 2016).

A significant change was made in the 2018 Draft. Article 7 provided that underwater cultural relic protection units and underwater cultural relic protection zones should be preserved in situ as much as possible. The authors hold that this clause represented remarkable progress for China, as it explicitly accepted in situ preservation as a priority, brought China closer to the 2001 Convention, and to a certain extent addressed the resource shortage problem of the state-led UCH salvage activities. However, the draft clause was surprisingly deleted in the 2019 Draft, and it was not restored in the finalized 2022 Revision (See Table 2). As a result, the in situ preservation of UCH is still not recognized as a priority principle in China’s UCH regulation.

3.3.2 Prohibited activities for UCH

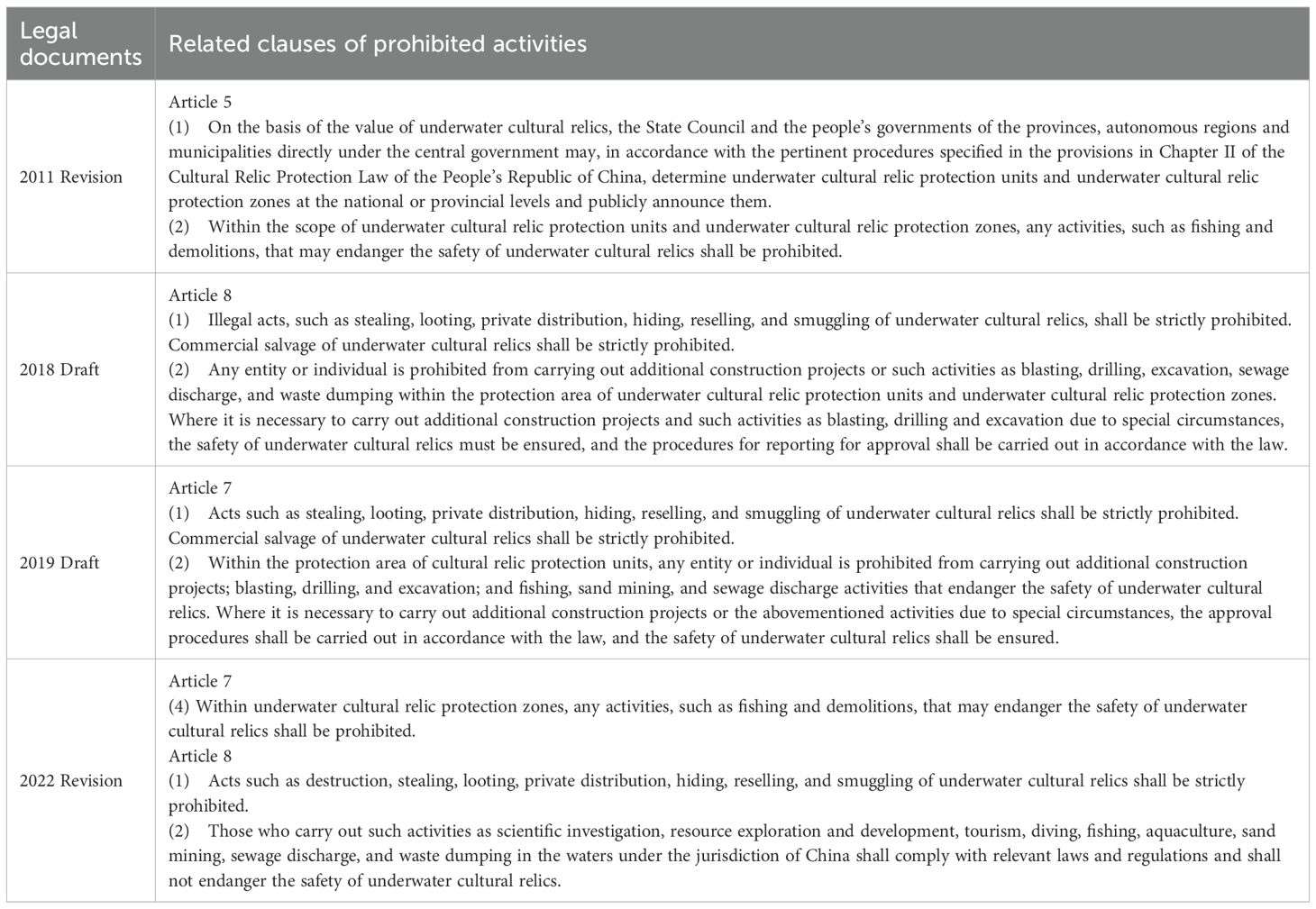

For the protection of UCH, acts that are harmful to UCH are prohibited by law. In general, the prohibition of more harmful acts implies higher levels of legal protection of UCH. Illegal acts, such as the destruction, stealing, hiding, and smuggling of UCH, are undoubtedly prohibited.15 In addition, certain economic activities, which may endanger the safety of UCH, also need to be prohibited, but which economic activities are prohibited is a controversial issue.

Notably, prohibited economic activities are related to the status of UCH. In China, the UCH to be protected takes two forms, i.e., cultural relic protection units and underwater cultural relic protection zones (UCRPZs). Governments may announce underwater cultural relics to be cultural relic protection units on the basis of their historical, artistic and scientific value, and governments may delineate waters where underwater cultural relics are relatively concentrated and need overall protection as UCRPZs. Originally, the 2011 Revision prohibited any activity, such as fishing or demolitions, that may endanger the safety of underwater cultural relics within the scope of underwater cultural relic protection units and UCRPZs.16

In the revision, the scope of prohibited activities underwent great changes (See Table 3). As the 2018 Draft provided, any entity or individual is prohibited from conducting any additional construction projects or operations such as blasting, drilling, digging, sewage discharge or waste dumping within the scope of underwater cultural relic protection units and UCRPZs. Under special circumstances, if it is necessary to conduct such constructions or operations, the safety of UCH must be ensured, and the matters should be subject to approval.17 Compared with the original ban laid down in 2011, the draft clause in 2018 signified a large step forward. Since the clause significantly enlarged the scope of prohibited activities, it was possible to establish an enhanced level of protection to UCH.

Regrettably, the draft clause was revised in a retrogressive way in 2022. The 2022 Revision distinguished the prohibited activities between UCRPZs and underwater cultural relic protection units. For UCRPZs, Article 7 of the 2022 Revision prohibited any activity, such as fishing and demolitions, that may endanger the safety of underwater cultural relics. This provision did not adopt the progressive clause in the 2018 Draft but rather followed the original ban laid down in 2011. Thus, the protection level for UCRPZs, which could have been increased if the draft clause of 2018 had been adopted, eventually remained the same as that in 2011.

For underwater cultural relic protection units, the 2022 Revision deleted the prohibition clause in the 2018 draft and did not explicitly lay down any prohibited activities. As a result, one cannot determine which economic activities are prohibited within the area of underwater cultural relic protection units in the 2022 Revision. An important question is why China deleted the draft ban from the finalized 2022 Revision. The government did not provide any official explanation, and the authors offer two possible explanations. As a first possibility, by leaving the prohibition clause blank, the government intended to avoid the highly disputed issue of which economic activities should be prohibited or retain discretionary room for enforcement flexibility. Another possible explanation concerns the legal link between the underwater cultural relic protection system and the general cultural relic protection system. Under China’s legal framework, the underwater cultural relic protection system is subordinate to the general cultural relic protection system. As a general law, China’s Cultural Relic Protection Law is applicable to the specific case of underwater cultural relic protection. The Cultural Relic Protection Law defines cultural relic protection units and specifies prohibited activities within the scope of cultural relic protection units, such as additional construction projects; operations such as explosion, drilling or digging;18 or the construction of facilities that pollute cultural relic protection units or the environment.19 Such legal prohibitions also apply to underwater cultural relic protection units. Thus, although the 2022 Revision does not list the prohibited activities in the specific context of underwater cultural relic protection units, the prohibitions can be found in the general, superior law, i.e., the Cultural Relic Protection Law. However, for either reason, the deletion of the ban from the 2022 Revision, as the authors believe, is problematic because, first, it creates artificial hurdles that make it difficult for people to easily access relevant law and, second, the general prohibitions established by the Cultural Relic Protection Law may fail to address the specific characteristics of UCH.

In summary, the clauses concerning UCH protection measures were changed back and forth in the revision process. The 2018 Draft, which explicitly embraced preservation in situ as a priority principle and greatly increased the scope of prohibited activities, attained a new high level of UCH protection. Regrettably, however, the finalized 2022 Revision did not realize the progress that could have been achieved by the 2018 Draft.

3.4 International cooperation

In the 2011 Revision, international cooperation was mentioned at the end of Article 7. Article 7 outlined two requirements for foreign countries, international organizations and foreign legal persons or natural persons that intend to conduct archaeological exploration or excavation activities in waters under Chinese jurisdiction: 1) cooperate with Chinese entities and 2) submit applications for special approval. This provision revealed China’s prudent attitude towards foreign involvement in UCH archaeological activities. In the 2018 Draft, the two requirements were not substantially changed.20

Since 2019, the requirements for foreign involvement in UCH archaeological activities have been modified to be more detailed, and the modification has largely absorbed the rules and practical experience of Measures for the Administration of Foreign-related Archaeology Activities released in 2016 (Jing, 2019). In the 2019 Draft, Article 9 specified detailed provisions for application materials and application procedures for foreign involvement in UCH archaeological activities.

The 2022 Revision further increased the importance of international cooperation. The difference in formality is noteworthy since international cooperation for the first time took the form of a separate clause, i.e., Article 12, rather than being a part of other clauses, as in past legislative documents. Article 12 contains four paragraphs. In the first paragraph, the two requirements for foreign involvement in UCH archaeological activities are reiterated. However, the scope of suitable foreign parties is narrowed down by excluding foreign legal and natural persons, thus leaving only foreign organizations and international organizations. In addition, the first paragraph adds qualification requirements for the Chinese and foreign entities involved in archaeological cooperation. The Chinese entities should have qualifications for archaeological excavation. The foreign entities should be professional archaeological research institutions, have experts engaged in research related to the subject or in a similar direction, and have certain practical archaeological working experience. These requirements ensure that archaeological exploration is conducted by qualified entities with the necessary competence for the purposes of UCH protection and scientific research. Notably, such qualification requirements are compatible with Rules 22 and 23 of the Annex of the 2001 Convention.

The second and third paragraphs of Article 12 concern procedural issues, including the application materials and application procedures. On the basis of the draft clause in 2019, the new procedural provisions of the 2022 Revision were stipulated in a more detailed way. Since foreign parties must cooperate with Chinese entities, the Chinese entities need to file applications to the NCHA, including a letter of intent for cooperation, a work plan, and relevant qualification materials. After receiving the application materials, the NCHA should seek the opinions of relevant scientific research institutions and experts, seek the opinions of relevant military organs if necessary, and submit them to relevant departments for review. When an application passes the review, it is submitted to the State Council for special approval. If an application fails, the applicants are notified of the reasons.

Importantly, the fourth paragraph of Article 12 was newly added in 2022. Underwater cultural relics, natural specimens and original materials of archaeological records obtained from Sino–foreign cooperative archaeological activities belong to China.21 The clause aims to claim China’s ownership of the work products of Sino–foreign archaeological cooperation. On the whole, therefore, the provisions of international cooperation have been greatly enriched and detailed in this round of revision, highlighting China’s increasing attention to international cooperation. In the meantime, China also focuses on enhancing its leadership, ensuring safety, and pursuing scientific rigor in archaeological cooperation work, said Jianhua Zhang, Deputy Director of the Archaeological Research Center of the NCHA (Zhang, 2022).

4 Evolution tendency: farther from or closer to the 2001 Convention?

As the NCHA stated, the newly revised regulation responded positively to the general principles and international obligations of the 2001 Convention, which was an expression of China’s positive participation, through national legal practice, in the international rules of ocean and cultural governance (Archaeological Research Center of the National Cultural Heritage Administration, 2022). Similarly, scholars hold that the 2022 Revision indicates that China took “a step closer” to the 2001 Convention (Li and Chang, 2023). However, this article argues that the “closer” statement is not accurate because for each key issue, the distance between China’s regulation and the 2001 Convention varied dynamically throughout the revision process, and an overall distance cannot be simply generalized. In this study, the dynamic historical process of distance changes for each specific issue is assessed. Through the generalization of the patterns in which the distance between the relevant clauses of Chinese UCH law and the 2001 Convention changed in the different stages of the revision process, the authors identify three types of evolution tendencies of the Chinese UCH legislation.

4.1 Continuously closer to the 2001 Convention

The authors identify the first type of evolution tendency as China’s legislation moving continuously closer to the 2001 Convention throughout the entire revision process. This tendency is reflected in the issues of public participation, international cooperation and the distribution of UCH responsibilities. Correspondingly, the distance between China’s law and the 2001 Convention has continuously narrowed on these issues.

First, with respect to public participation, Article 20 of the 2001 Convention establishes the obligation of raising public awareness regarding the value of UCH and the importance of UCH protection. Originally, in the 2011 Revision, China did not pay much attention to public participation. The 2018 Draft introduced a specialized clause for raising public awareness by building UCH parks, and the 2019 Draft retained this clause. In the 2022 Revision, a systematic and complete framework for public participation was finally established. In such a revision process, the number of public participation clauses continued to grow, and the contents of these clauses were continuously enriched. Therefore, China moved continuously closer to the requirements of the 2001 Convention on the issue of public participation.

Second, the tendency is reflected in the evolution of international cooperation clauses. As UCH often has an international character, a number of nations may declare an interest in the UCH. How to coordinate the interests and activities of these nations for the benefit of the UCH, which “reflects the common heritage of humankind” (Forrest, 2002, p.551), gives rise to a significant challenge. Thus, facilitating international cooperation on UCH protection is established as an essential principle of the 2001 Convention. Article 19 of the Convention provides the cooperation and information sharing duties in UCH protection, including collaborating in the investigation, excavation, and study of such UCH. Originally, for international cooperation in underwater archaeological activities, China’s 2011 Revision established a simple and rough framework lacking operational details. The 2018 Draft just refined the wording of the provision. However, since the 2019 Draft, China has developed clauses concerning international cooperation in detail. In the 2022 Revision, a specialized and comprehensive system was finally established. China’s legislation has been revised to improve the enforceability and transparency of the approval procedure and facilitate Sino–foreign archaeological cooperation (Sun, 2024), indicating that China’s UCH legislation has developed in a direction that is continuously closer to the 2001 Convention.

Third, the legal evolution of the distribution of UCH responsibilities among institutions shows a tendency of moving continuously closer to the 2001 Convention. In the 2011 Revision, the distribution of UCH responsibilities was matter-based, and the workload was largely concentrated on the NCHA. The revisions in 2018, 2019 and 2022 reformed the UCH institutional arrangement in two directions. Vertically, the revisions aimed to decentralize UCH protection responsibility from the central level to the local level, which could activate the resources of local governments and reinforce the implementation of UCH rules in local regions. Horizontally, the revisions aimed to facilitate collaboration among different departments. Considering these two directions, it is fair to conclude that China was determined to refine the past institutional arrangement, select competent authorities to protect UCH, and increase the enforceability of UCH legislation. This is consistent with the 2001 Convention, which requires the establishment of competent authorities for the protection, conservation, and management of UCH.22

4.2 Once closer to but ultimately farther from the 2001 Convention

On the issue of UCH protection measures, China’s legislation once moved closer to the 2001 Convention but finally pulled back, which is the second type of tendency observed. Among the 3 documents produced in the revision history (i.e., the 2018 Draft, 2019 Draft, and 2022 Revision), the 2018 Draft is, as the authors hold, the most progressive version and bears the greatest resemblance to the 2001 Convention. First, Article 7 of the 2018 Draft provided that underwater cultural relic protection units and UCRPZs should be preserved in situ as much as possible. This was the first time that China’s legislation explicitly recognized in situ preservation as a priority, consistent with the standing of the 2001 Convention. In situ preservation was initially recognized as the first option in contemporary archaeology, and this archaeological principle was gradually accepted in cultural heritage law, particularly UCH law (Aznar, 2018). The 2001 Convention introduces the in situ preservation of UCH as the first option, which establishes high international standards for UCH protection and is deemed a significant achievement of the 2001 Convention (Carducci, 2002; Fu, 2003). Second, Article 8 of the 2018 Draft explicitly prohibited the commercial salvage of UCH, which was in conformity with the 2001 Convention’s position to prevent the commercialization of UCH. In response to the recovery of UCH by treasure salvors and the increasing commercialization of UCH, the 2001 Convention explicitly states that UCH “shall not be commercially exploited”.23 Specifically, the 2001 Convention prohibits UCH from being traded, sold, bought or bartered as commercial goods.24 Although this prohibition has been criticized, for instance, for eliminating the economic value of UCH or probably leading to a “black market” in UCH (Forrest, 2002; Vadi, 2009), it establishes a trend in international law standards to combat the commercialization of UCH. Third, the 2018 Draft prohibited any entity or individual from conducting additional construction projects and operations such as explosion, drilling, digging, sewage discharge, and waste dumping.25 This ban was rather stringent, as it covered a broad range of harmful activities and applied to a broad scope, i.e., both underwater cultural relic protection units and UCRPZs. Therefore, throughout the legislative history, the 2018 Draft, which reflected the spirit of the 2001 Convention, represented the point at which China’s law was closest to the 2001 Convention.

However, the major progress that could have been achieved by the 2018 Draft was undone in the later revision process. First, the in situ preservation of UCH was deleted from the 2019 Draft and 2022 Revision. This indicates that China retained its preference for the excavation of UCH compared to in situ preservation. Second, the prohibition of commercial salvage, which was retained in the 2019 Draft, was also abandoned in the 2022 Revision. As a result, China’s attitude towards commercial salvage of UCH is unclear. Third, the ban on harmful activities to UCH in the 2018 Draft was largely relaxed in the 2022 Revision, in which the prohibited activities for UCRPZs retained the status quo under the original 2011 Revision and the prohibited activities for underwater cultural relic protection units became even more obscure. The relaxing of the draft ban drawn in 2018 might be related to economic considerations (which will be further discussed in Section 5.2). In summary, with respect to the protection measures of UCH, China’s legislation shows a tendency for hesitation: it once moved closer to the Convention in the 2018 Draft but eventually regressed.

4.3 Constantly far from the 2001 Convention

As the third type of evolution tendency, certain provisions of China’s UCH legislation remained almost unchanged throughout the revision process. These provisions include the clauses concerning the definition of UCH and the ownership-based jurisdiction of UCH. As Article 2 of the 2022 Revision provides, UCH refers to human cultural heritage that has historical, artistic and scientific value, remaining in the following waters:1) cultural heritage of Chinese origin, of unidentified origin, and of foreign origin that remains in the Chinese inland waters and territorial waters; 2) cultural heritage of Chinese origin and of unidentified origin that remains in sea areas outside the Chinese territorial waters but under Chinese jurisdiction; and 3) cultural heritage of Chinese origin that remains in sea areas outside the territorial waters of any foreign state but under the jurisdiction of a certain foreign state and in the high seas. For UCH specified in the first and second situations, the UCH shall be owned by China, and the state shall exercise jurisdiction over such UCH; for UCH specified in the third situation and cultural heritage of unidentified origin remaining in sea areas outside the territorial waters of any foreign country but under the jurisdiction of a certain foreign state and in the high seas, the state shall have the right to identify the owners of such heritage,26 which is based on China’s potential ownership of such UCH (Huang and Nan, 2019). However, Article 2 also provides that the definition of UCH excludes underwater remains after 1911 irrelevant to significant historical events, revolutionary movements, and notable men.

With respect to the definition of UCH, China extends a different scope of UCH from the 2001 Convention. First, the time condition is a prominent example of the divergence. The 2001 Convention requires traces of human existence to be under water for at least 100 years to be considered UCH, which reflects a dynamic measurement of time. In contrast, China fixes a static time point, as China requires UCH to have been under water since before 1911 unless it is related to significant historical events, revolutionary movements, and notable men. In other words, China follows a static time measurement to define UCH, which is easy to operate but lacks robustness. As a result, the scope of UCH in Chinese law remains relatively stable, whereas under the 2001 Convention, the scope of UCH expands over time. Second, during the negotiations of the 2001 Convention, whether the definition of UCH should introduce a significance criterion caused a heated debate. Civil law nations intended to provide “blanket” protection for all heritage over a certain age, while common law nations, such as the United Kingdom, selectively protected heritage on the basis of its particular significance (Dromgoole, 2013; Forrest, 2002). In the end, the Convention incorporated, in addition to the time condition, “a cultural, historical or archaeological character” as a qualifying criterion to define UCH. 27 Compared to the Convention’s definition, China’s definition seems to provide flexibility in situations where underwater remains do not satisfy the time condition but have particular significance. For remains that have been under water for less than 100 years, the Convention does not apply even if the remains are determined to have cultural, historical or archaeological significance. In contrast, under Chinese law, remains that have been under water after 1911 can still be recognized as UCH to the extent that they are relevant to significant historical events, revolutionary movements, and notable men (Fu, 2003). In this sense, China’s definition provides greater flexibility than that of the 2001 Convention.

With respect to jurisdiction, the state parties of the 2001 Convention protect UCH on the basis of their territorial jurisdiction, and the Convention does not address the ownership of UCH. However, China’s protection and management of UCH is based on the Chinese ownership of UCH, in addition to the location of UCH (Huang and Nan, 2019; Lin, 2019). The purpose of the Chinese definition is to ensure that China holds ownership of UCH that originated from China but may have been lost in waters outside China’s jurisdiction. The difference is prominently reflected in the divergence of Chinese law from the 2001 Convention on the regime of discovering, reporting and protecting UCH in exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and continental shelves (Li and Chang, 2023). The 2001 Convention requires contracting states to protect UCH discovered within their EEZs and continental shelves regardless of ownership, which appears, on the surface, to expand jurisdiction but, in essence, sets obligations for the contracting parties. However, if UCH of Chinese origin and of unidentified origin appears within China’s EEZs and continental shelves, China claims ownership of the UCH and extends legal protection over the UCH,28 whereas for UCH, which is clearly owned by other countries, found in China’s EEZs and continental shelves, it is not subject to the protection offered by China.

In summary, the unchanged clauses concerning China’s definition and jurisdiction of UCH remain divergent from the 2001 Convention, and the distance between China’s regulation and the 2001 Convention on these issues has remained constant. These issues represent China’s core interests in UCH, and China’s standing holds firm on these issues, especially regarding China’s ownership of UCH.

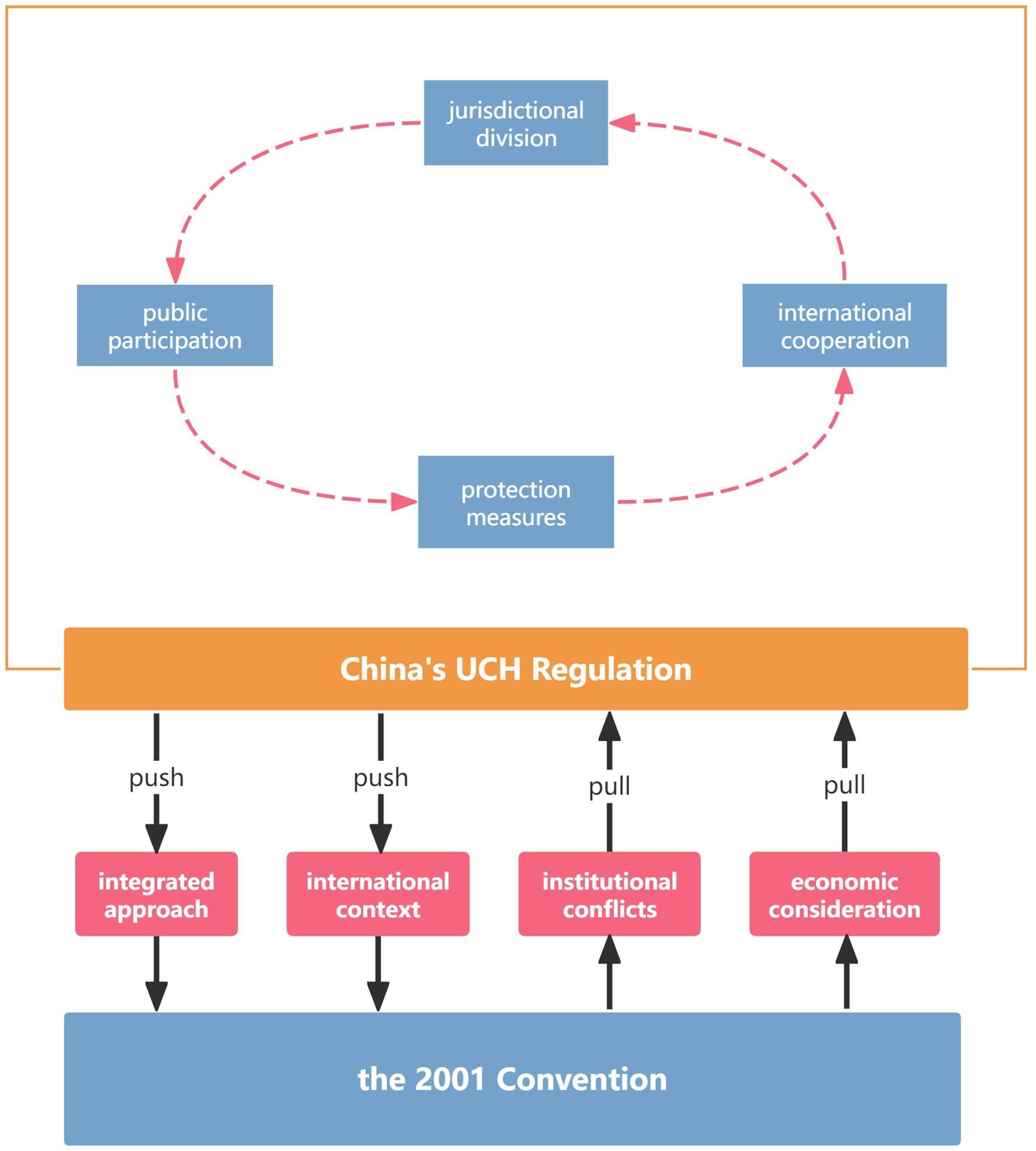

5 Influencing factors: “pull” and “push” factors

As the above analysis shows, China’s UCH legislation underwent a revision process in which three types of evolution tendencies can be distinguished. In this section, the authors develop a “push-pull” interpretive framework to provide reasonable explanations for the dynamic and complicated revision process. As the authors believe, the revision was driven by forces in two different directions, i.e., “push” and “pull” forces. One type of force “pushed” China to adopt the principles and rules established by the 2001 Convention, whereas the “pull” forces drove China to satisfy its national interests and cater to its own specific considerations. Driven by the two different forces, the revision history as a whole was an arduous process, and the 2022 Revision was finally made as a compromise. This section identifies specific “push” and “pull” factors that influenced China’s dynamic revision process (See Figure 1).

5.1 From a state-led approach to an integrated approach

As the 2011 Revision showed, China traditionally adopted a centralized and state-led model to protect and manage UCH. In practice, high-profile underwater archaeological salvages of China, such as the archaeological excavations of South China Sea No. 1 and No. 2 ancient shipwrecks, were solely implemented by the government. Considering China’s long coastline, the abundance of UCH resources and the pressing situation of UCH protection, however, the unsustainability of the state-led model became prominent after years of practice.

The first drawback of the state-led model concerns the shortage of funds and the delay of protection (Lu and Zhou, 2016). As UCH protection depends on the public budgets of governments, this undoubtedly creates financial pressures. Furthermore, the lack of funds resulted in a delay in the rescue of endangered UCH. For example, as the South China Sea No. 1 project cost more than 300 million RMB, the excavation of South China Sea No. 2 was delayed for almost three years because of the lack of state funds (Lu and Zhou, 2016). For a second problem, as the state-led model is not able to promptly respond to every UCH that needs to be protected, fishermen and illegal treasure seekers take the opportunity to excavate UCH, and illegal salvage imposes an increasing threat to UCH in China (Xinhua News Agency, 2011). Illegal salvage groups, which have become highly organized and technically advanced, have an increased ability to loot UCH. From 2005 to 2006, police officers from Fujian Province discovered 46 cases of illegal salvage and illegal trade of UCH, involving 50 vessels, 516 persons and 7372 ancient porcelains (Wen, 2011). To maximize economic profits, illegal looting groups prefer intrusive exploration methods, destroying surrounding cultural relics and the ocean environment. In addition, due to the weak protection awareness and insufficient protection measures, illegal looting groups usually fail to preserve the UCH that they have salvaged. On the whole, the centralized state-led model is no longer able to satisfy China’s demands for UCH protection, and a new approach is needed.

As the revision process shows, China is shifting to an integrated approach that enlists the resources, capability, and enthusiasm of the whole public for the protection of UCH. The 2022 Revision covers a broad range of new subjects, such as local governments, individuals and construction entities, to form an integrated force. First, for local governments, the new territory-based arrangement decentralizes UCH responsibility from the central government to local governments, which utilizes the competence of local governments. Second, for individuals, an enriched system of public participation is established in the 2022 Revision, which enhances every individual’s awareness of protecting UCH, submitting UCH and reporting UCH violations. Third, for construction entities, Article 13 of the 2022 Revision, for the first time, provides for construction-based archaeological investigations. For large-scale infrastructure construction projects in Chinese waters, before launching construction projects, construction entities should request that competent authorities make arrangements for conducting archaeological investigations in places where UCH may be buried within the area designated for the construction projects. Owing to the limited manpower and high costs, it is impractical for the state to comprehensively conduct a specialized underwater archaeological survey of the whole sea. Article 13 allows archaeological investigations to free-ride on construction projects since the costs of archaeological investigations are marginal and negligible for large-scale infrastructure construction projects. Notably, the results of such archaeological investigations, either revealing UCH or excluding the existence of UCH in the construction region, provide important preliminary guidance for future archaeological investigations, facilitate the mapping of the distribution of UCH, and effectively prevent UCH destruction due to construction projects (Cui, 2022). In a word, China has shifted from the centralized state-led model to an integrated and decentralized approach, which, as a result, pushes China closer to the 2001 Convention.

5.2 Economic considerations

As the largest developing country in the world, China has considered the development of its national economy the core of national policies in the past four decades. In 2017, Chairman Xi Jinping noted that China should accelerate the building of a strong oceanic country and that the ocean plays an irreplaceable role in promoting economic development (Xi, 2017). In such an economy-oriented policy context, China values the promotion of economic growth in addition to the protection of UCH in the revision of UCH regulation. In fact, China needs to balance UCH protection and economic development, but the two goals may be in tension. For the purpose of strengthening UCH protection, protection measures should be designed as stringently as possible. However, to promote the marine economy, the state needs to allow and encourage various economic activities in waters, to the prejudice of the goal of UCH protection.

The consideration of economic development can explain China’s hesitation and resistance to the adoption of strict UCH protection measures, especially in the two following examples. The first example concerns the deletion of the termination requirements of large-scale infrastructure construction projects. As Article 11 of the 2019 Draft provides, if any UCH is discovered in the construction process, the construction activities should be immediately terminated, and the scene should be protected. However, this clause, which is able to preserve the discovered UCH to a great extent, is not found in the 2022 Revision. The authors believe that economic considerations can explain the deletion because large-scale infrastructure construction projects in waters incur extremely high daily costs, and the termination of projects results in enormous economic loss. In the balance between UCH protection and economic considerations, China prioritized the maintenance of infrastructure construction. The second example concerns the change in the scope of prohibited economic activities in UCRPZs. Initially, the 2011 Revision explicitly prohibited activities, such as fishing or demolitions, that might endanger the safety of UCH in UCRPZs. Although the most progressive 2018 Draft significantly enlarged the scope of prohibited activities, the finalized 2022 Revision stepped back to retain the status quo with the 2011 Revision. The authors believe that China’s hesitation to adopt the protective measures drafted in 2018 can be accounted for by economic considerations. If the prohibition ban was designed too broad, as it was in the 2018 Draft, the economic activities allowed in UCRPZs would have been greatly limited, and economic development would have been correspondingly undermined. Overall, the focus on economic development distracted China from pursuing the UCH protection objective and decreased the UCH protection level that China could have extended. Thus, the promotion of the national economy amounts to a pull factor that drove China far from the 2001 Convention, which values the protection of UCH as the sole objective.29

5.3 Institutional conflicts

In the revision, China made remarkable efforts to establish competent authorities for UCH work. However, the conflict among different government departments remained a controversial factor. The political interests of different departments gave rise to a “bureaucratic turf war”, which was a factor pulling China away from the 2001 Convention.

As the original enforcement system under the 2011 Revision was found to be weak, how to reform the UCH enforcement system was an issue of debate in the revision process (Wang, 2022). The 2018 Draft updated the original system in two ways. First, the NCHA, which drafted the 2018 Draft, designated itself the main responsible body for UCH protection, which would jointly carry out UCH law enforcement inspections with maritime and waterborne law enforcement departments.30 This clause caused great controversy in society. Although it had expertise and experience in the protection of UCH, the NCHA did not have sufficient maritime law enforcement experience, and the NCHA itself was not a strong, powerful bureau among the involved government departments. Thus, whether the NCHA was capable of acting as the responsible body in UCH law enforcement inspections was highly questionable. This might be the reason why this provision was deleted in the later drafts, as the involved departments could not reach a consensus on the choice of the main responsible body. Second, as the 2018 Draft provided, a joint UCH law enforcement working mechanism should be established by governments.31 The joint working mechanism was expected to reinforce the enforcement effects of UCH law (Huang and Nan, 2019), as it could address certain drawbacks of ad hoc departmental cooperation, such as incompact organization, information sharing barriers, and the overlaps and conflicts of responsibilities.

However, the draft article was reorganized entirely under Article 17 of the 2022 Revision. First, the designation of the main responsible body was no longer mentioned, and the focus of Article 17 was on the division of enforcement power. As Article 17 provides, competent cultural relic departments, police departments and maritime law enforcement agencies carry out, in accordance with the division of responsibilities, UCH protection law enforcement work and strengthen law enforcement collaboration. As the authors observe, the division of labor among the three departments is obscure, and which department takes the main responsibility is not elaborated. In practice, this may create the conflicts of responsibilities for UCH protection and lead to disagreements regarding which department should have the leading role among the three departments. Second, the joint working mechanism, which could have significantly increased enforcement effects, was not adopted in the 2022 Revision. Article 17 only requires cultural relic departments to strengthen communication and coordination with other relevant departments in UCH protection work and share information on the law enforcement of UCH.

In summary, as a result of the bureaucratic turf war, the 2022 Revision did not clearly designate a responsible body and did not retain the joint working mechanism. Rather, a compromise that obscured the division of labor among relevant departments was finally achieved in 2022. This, to a certain extent, undermined China’s initial efforts to establish a competent enforcement system for UCH law.

5.4 The international context

Another factor that significantly influenced China’s revision is the international context. UCH plays an important role in serving China’s diplomatic strategies and creating an international cultural image. In China’s 14th Five-Year Plan concerning Cultural Heritage Protection and Technological Innovation, the promotion of international communication and cooperation on cultural heritage, including strengthening international communication and participating in the global governance of cultural heritage, is specifically emphasized.32 Such international demands drive China’s UCH law closer to the established international rules of the 2001 Convention.

As an international law instrument, the 2001 Convention has profound influences in shaping most international and regional initiatives aimed at UCH protection as well as the practices and domestic laws for UCH protection of both the parties and non-parties to the Convention (Nafziger, 2018; Sarid, 2017). Although China is not a party to the 2001 Convention, the 2001 Convention provides a standard legal model for China to learn from. Notably, in the process of approaching the 2001 Convention, China has charted its own way: Chinese UCH regulation maintains reasonable distinctions to satisfy China’s specific demands amid the general tendency to move closer to the 2001 Convention. The preservation of UCH in situ provides a prominent example. Although China deleted the draft clause in 2018 that recognized in situ preservation as a priority, the regime of the UCRPZ is deemed an interim attempt to accept the in situ preservation principle on the basis of the UCH protection situation in China and the Chinese government’s capacity (Ren, 2023). This indicates that rather than blindly pursuing consistency with the 2001 Convention, China placed great emphasis on its specific demands in the revision of UCH regulation.

Despite maintaining certain Chinese characteristics, China is, as the authors believe, embracing international UCH rules to an increasing extent, and this general tendency will not be altered in the future. In fact, the protection of UCH depends largely on the level of technology and human resources of a country, and China can benefit from moving closer to the 2001 Convention and forming close contact with other countries in these aspects. In the past, China’s international cooperation focused mainly on the training of archaeologists. For example, in the 1980s, China sent students abroad to study underwater archaeology and trained a group of underwater archaeologists.33 Through cooperation with other nations, China was able to have an increased number of qualified diving professionals and learn technological achievements from other countries. Such cooperation contributed to the improvement in the level of UCH protection in China, which, in turn, further attracted China to deepen international cooperation. On the whole, the international context serves as a factor that pushed China’s UCH regulation closer to the 2001 Convention, which provides common legal grounds for international UCH protection and facilitates China’s international UCH cooperation with other countries.

6 Conclusion

China has a long history of maritime trade, from the Han Dynasty to the prosperity of the Tang Dynasty, and its maritime trade has continued to the present day. Considering the fast development of underwater archaeology and the pressing situation of UCH protection, China has made persistent efforts to polish its legal framework for the protection of UCH. The most recent round of revision, which lasted almost 9 years, represents a dynamic process of legislative evolution, in the authors’ estimation. In the revision process, the issues of greatest concern to China were the distribution of UCH responsibilities among institutions, public participation, protection measures, and international cooperation regarding UCH. Importantly, in terms of the distance between China’s legislation and the 2001 Convention, this article argues against the traditional “closer” statement and identifies three different types of evolution tendencies in the revision history. With respect to public participation, international collaboration, and the distribution of UCH responsibilities, China progressively aligned more closely with the 2001 Convention during the revision process. However, with respect to UCH protection measures, China showed a hesitant attitude, as it initially approached the 2001 Convention more closely in 2018 but subsequently retreated further away from it in 2022. Throughout the revision process, China did not make substantive alterations to the definition of UCH and the ownership-based jurisdiction of UCH, thereby maintaining a constant distance from the 2001 Convention. The dynamic and arduous revision process was a consequence of the “push” and “pull” forces. Specifically, the unsustainability of China’s traditional state-led model and the international context pushed China closer to the 2001 Convention, while the considerations of economic development and institutional conflicts pulled China back. Driven by the “push” and “pull” forces in two different directions, China finally reached a compromise in the 2022 Revision.

Regarding the question of whether China would become a party to the 2001 Convention in the future, an overall consideration of the incentives of China and the feasibility of Chinese law is needed. In terms of the incentives of China, considering the fact that most of the neighboring countries that often have UCH disputes with China, such as Japan or Indonesia, have not acceded to the 2001 Convention, China would benefit little from acceding to the 2001 Convention in resolving actual UCH disputes. In addition, there are other debated issues in the Convention, such as the sovereign immunity of sunken warships or the responsibilities of party states in various marine areas. Thus, the incentives for China to accede to the Convention are not strong. Even if China wished to, China could not accede to the Convention without amending the current 2022 Revision. The aim of the Chinese UCH legislation is not only to protect and manage UCH but also to claim the Chinese ownership of UCH. For all UCH of Chinese origin, China intends to claim ownership and jurisdiction over it wherever it is found (except in the territorial waters of a foreign state); while for UCH of foreign origin, China does not claim the ownership-based jurisdiction unless it is found in the territorial waters of China. To claim the ownership of UCH is a consistent theme that has never changed throughout the Chinese legislative process from 1989 to 2022. Although the 2001 Convention has the concept of “a verifiable link”, it refers to states having “especially a cultural, historical or archaeological link” rather than an ownership link.34 The rights granted to such states are to be invited to join bilateral, regional or multilateral agreements, to be informed, or to declare an interest in being consulted, and China is not able to claim ownership and jurisdiction based on such “a verifiable link”. Therefore, the application of the “verifiable link” precisely reflects the evasion and ambiguous treatment of the ownership of UCH under the 2001 Convention, which is in conflict with the clear assertions under Article 2 and Article 3 of the Chinese UCH law. On the issue of UCH ownership, China’s position does not allow for the slightest ambiguity or compromise. Overall, Chinese UCH legislation has actually embraced the rules and spirit of the 2001 Convention to an increasing extent, with certain reservations due to China’s core national interests and specific situation. The legislative history of the 2022 Revision clearly shows that China expects to more actively participate in the international efforts of UCH governance and offer Chinese wisdom and contributions for the protection of UCH.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

QL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XQ: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Project of the Ministry of Education of China [grant no. 24YJCGJW005], the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant no. 202413005], and the Postdoctoral Innovation Project of Shandong Province [grant no. SDCX-RS-202400023].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ See Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, UNESCO, https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/convention-protection-underwater-cultural-heritage?hub=66535 (Accessed on June 17, 2025).

- ^ Regulation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics, Order of the State Council No. 42, promulgated on October 20, 1989 (hereinafter 1989 Regulation).

- ^ Regulation of the PRC on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics, Order of the State Council No. 588, amended on January 8, 2011 (hereinafter 2011 Revision).

- ^ National Cultural Heritage Administration, Drafting Statements for the Draft Revision of the Regulation of the PRC on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage, February 11, 2018, http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2018/2/11/art_1966_146987.html (Accessed on January 6, 2025).

- ^ Press release of the National Cultural Heritage Administration, An Expert Conference on the Draft Revision of the Regulation on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics was held in Beijing, July 7, 2018, https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-07/07/content_5304403.htm (Accessed on January 6, 2025).

- ^ Guiding Opinions of the State Council on Further Strengthening the Work of Cultural Relics, promulgated by the State Council, March 8, 2016, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-03/08/content_5050721.htm (Accessed on January 6, 2025).

- ^ Notice of the National Cultural Heritage Administration on Publicly Soliciting Opinions on the “Draft Revision of the Regulation of the PRC on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics” (Draft for Opinion), National Cultural Heritage Administration, February 11, 2018, http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2018/2/11/art_1966_146987.html (hereinafter 2018 Draft) (Accessed on January 6, 2025).

- ^ Notice of the Ministry of Justice on the Publicly Soliciting Opinions on the “Regulations on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics (Draft Amendment for Review)”, Ministry of Justice, March 19, 2019, https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-03/19/content_5375083.htm (hereinafter 2019 Draft) (Accessed on January 6, 2025).

- ^ Regulation of the PRC on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics, Order of the State Council No. 751, amended on January 23, 2022, effective on April 1, 2022, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-02/28/content_5676054.htm (hereinafter 2022 Revision) (Accessed on January 6, 2025).

- ^ See 2018 Draft, Article 4.

- ^ See 2019 Draft, Article 14.

- ^ 2018 Draft, Article 15.

- ^ See 2022 Revision, Article 18.

- ^ See 2001 Convention, Article 2(5).

- ^ See 2022 Revision, Article 8.

- ^ See 2011 Revision, Article 5.

- ^ See 2018 Draft, Article 8.

- ^ The Cultural Relic Protection Law of the PRC, promulgated by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, amended on November 8, 2024, Article 28.

- ^ Ibid, Article 30.

- ^ See 2018 Draft, Article 10.

- ^ See 2022 Revision, Article 12.

- ^ See 2001 Convention, Article 22.

- ^ 2001 Convention, Article 2(7).

- ^ 2001 Convention, Rule 2 of the Annex.

- ^ See 2018 Draft, Article 8.

- ^ See 2022 Revision, Article 3.

- ^ See 2001 Convention, Article 1.

- ^ See 2022 Revision, Article 2, Article 3.

- ^ See 2001 Convention, Article 2(1).

- ^ 2018 Draft, Article 14.

- ^ 2018 Draft, Article 14.

- ^ General Office of the State Council on the Issuance of the “14th Five-Year Plan” for the Protection of Cultural Relics and Scientific and Technological Innovation Notification, issued by the General Office of the State Council No. 43[2021], November 8, 2021, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-11/08/content_5649764.htm.

- ^ See “Under-water Archaeology”, Chinese Social Sciences Net, December 17, 2005 (in Chinese), http://kaogu.cssn.cn/zwb/kgyd/kgbk/200512/t20051217_3908480.shtml (Accessed on January 6, 2025).

- ^ See, e.g., Article 6 and Article 7 of the 2001 Convention.

References

Archaeological Research Center of the National Cultural Heritage Administration (2022). Ride the wind and waves, and move forward: before the implementation of revised Regulation of the PRC on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics. Available online at: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2022/4/1/art_722_173621.html (Accessed January 6, 2025).

Aznar M. J. (2018). In situ preservation of underwater cultural heritage as an international legal principle. J. Maritime Archaeology. 13, 67–81. doi: 10.1007/s11457-018-9192-4

Browne K. and Raff M. (2022). “The protection of underwater cultural heritage—future challenges,” in International Law of Underwater Cultural Heritage (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 591–665.

Bulut N. and Yüceer H. (2023). A literature review on the management of underwater cultural heritage. Ocean Coast. Manage. 245, 106837. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106837

Calantropio A. and Chiabrando F. (2023). The evolution of the concept of underwater cultural heritage in Europe: a review of international law, policy, and practice. Heritage. 6, 7660–7673. doi: 10.3390/heritage6120403

Carducci G. (2002). New developments in the law of the sea: the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage. Am. J. Int. Law. 96, 419–434. doi: 10.2307/2693936

Cui Y. (2022). A grounded and operable regulation on the protection and management of underwater cultural relics (Beijing, China: National Cultural Heritage Administration). Available online at: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2022/3/1/art_1961_173140.html.

Dromgoole S. (2013). Reflections on the position of the major maritime powers with respect to the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage 2001. Mar. Pol. 38, 116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.05.027

Fan Y. (2014). “Underwater cultural heritage conservation and the convention practice in China,” in Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage 2014. Available online at: http://www.themua.org/collections/items/show/1622.

Forrest C. (2002). A new international regime for the protection of underwater cultural heritage. Int. Comp. Law Quarterly. 51, 511–554. doi: 10.1093/iclq/51.3.511

Fu K.-C. (2003). A chinese perspective on the UNESCO convention on the protection of the underwater cultural heritage. Int’l J. Mar. Coast. L. 18, 109–126. doi: 10.1163/157180803100380384

Huang W. and Nan Y. (2019). Research on measures of China’s accession to the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage - from the perspective of comparison and combination between the draft revision to China’s Regulation and the Convention. J. Boundary Ocean Stud. (Bianjie yu haiyang yanjiu). 4, 56–73.

Janowski Ł., Pydyn A., Popek M., and Tysiąc P. (2024). Non-invasive investigation of a submerged medieval harbour, a case study from Puck Lagoon. J. Archaeological Science: Rep. 58, 104717. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104717

Jiang B. (2022). Comments on the revised Regulation on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics (Beijing, China:National Cultural Heritage Administration). Available online at: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2022/4/8/art_722_173715.html.

Jing Y. (2019). Protection of underwater cultural heritage in China: new developments. Int. J. Cultural Policy. 25, 756–764. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2017.1372753

Jing Y. and Li J. (2019). Who owns underwater cultural heritage in the South China Sea. Coast. Manage. 47, 107–126. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2019.1540908

Li X. and Chang Y.-C. (2023). A step closer to the convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage 2001: China’s latest efforts in regulation. Mar. Pol. 147, 105346. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105346

Lin Z. (2019). Jurisdiction over underwater cultural heritage in the EEZ and on the continental shelf: a perspective from the practice of states bordering the South China Sea. Ocean Dev. Int’l L. 50, 170–189. doi: 10.1080/00908320.2019.1582601

Lin Z. (2023). Chinese legislation on protection of underwater cultural heritage in marine spatial planning and its implementation. Int. J. Cultural Policy. 29, 500–517. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2022.2080201

Lu B. and Zhou S. (2016). China’s state-led working model on protection of underwater cultural heritage: practice, challenges, and possible solutions. Mar. Pol. 65, 39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.003

Nafziger J. A. R. (2018). The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage: its growing influence. J. Maritime Law Commerce. 49, 371–400. Available online at: https://docs.rwu.edu/law_ma_jmlc/vol49/iss3/13

Papageorgiou M. (2018). Underwater cultural heritage facing maritime spatial planning: legislative and technical issues. Ocean Coast. Manage. 165, 195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.08.032

People’s Daily (2022). Li Keqiang signs State Council Decree announcing Revised Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Relics. Available online at: https://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2022-03/01/nw.D110000renmrb_20220301_5-01.htm (Accessed June 14, 2025).

Ren P. (2023). Research on legal issues concerning the protection of underwater cultural heritage in the international underwater region. (Dissertation Thesis). Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China.

Sarid E. (2017). International underwater cultural heritage governance: past doubts and current challenges. Berkeley J. Int’l L. 35, 219–261. doi: 10.15779/Z383R0PT20

Sun J. (2024). The development and prospect of underwater archaeology in China. Technol. Rev. (Keji daobao). 42, 38–47. doi: 10.3981/j.issn.1000-7857.2023.11.01647

UNESCO (2001). Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. Available online at: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/convention-protection-underwater-cultural-heritage?hub=66535 (Accessed January 6, 2025).

Vadi V. S. (2009). Investing in culture: underwater cultural heritage and international investment law. Vanderbilt J. Transnational Law. 42, 853–904.

Wang J. (2022). Refinement of protection measures for underwater cultural heritage: insights from Australia’s 2018 Underwater Cultural Heritage Act. Res. Chin. Cultural Relics Sci. (Zhongguo wenhua yichan yanjiu). 04, 10–18. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-9677.2022.04.002

Wang Y. and Li W. (2024). The idea renewal and legal perfection of underwater cultural relics protection and management. J. South China Sea Stud. (Nanhai Xuekan). 10, 56–68.

Ward S. (2023). The Fourth Asia Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage: a marine policy perspective. Mar. Pol. 148, 105358. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105358