- 1School of Humanities and Law, Jiangsu Ocean University, Lianyungang, China

- 2School of Economic Law, East China University of Political Science and Law, Shanghai, China

- 3School of Marine Law and Humanities, Dalian Ocean University, Dalian, China

Marine environment public interest litigation (MEPIL) is a crucial judicial mechanism for protecting marine resources and the environment in China. In a relatively divided governance context between land and sea, the operation of MEPIL has encountered significant challenges due to the immaturity of regulations. The theoretical aspects of MEPIL have been widely discussed. However, as a special arrangement embedded in China’s traditional judicial system, the operation of MEPIL remains to be explored through empirical analysis. Disputes regarding standing, jurisdiction, and compensation mechanisms persist. This research examines MEPIL practices in light of the latest available MEPIL-related judgments following the revision of China’s Marine Environmental Protection Law in 2023. Based on the content and comparative analysis of 218 judgments, the judicial landscape of MEPIL is described from the perspectives of the rules regarding plaintiffs, jurisdiction, and compensation. The challenges primarily include disputes over the qualification and priority of plaintiffs, the complexity of MEPIL jurisdiction, and inadequate arrangements for supervising marine ecological damage compensation. Further analysis reveals that the institutional challenges in MEPIL are caused by its cross-sectional nature and different judicial arrangements for marine and environmental procedures. To improve the judicial system for MEPIL, three crucial reform approaches are needed:(a) confirm the standing of social organizations to sue in MEPIL and stipulate equal rights of action among administrative authorities, procuratorial organs and social organizations; (b) provide centralized jurisdiction by the maritime court with an exception in land-sea crossing litigation; (c) establish compensation fund and deposit mechanisms for ecological damage. These reform approaches are beneficial for the effective implementation of MEPIL and provide more support for public participation in marine environmental governance. Considering that the rules governing marine compensation are still in their infancy, the compensation fund and deposit mechanisms can further enhance the implementation of ecological compensation, providing more effective relief for the damaged marine environment and resources.

1 Introduction

Environmental public interest litigation aims to strengthen legal protection for ecological well-being. Marine environment public interest litigation (MEPIL) is a subset of environmental public interest litigation, which has played a crucial role in safeguarding China’s marine environment. However, in the context of the relative separation of land and sea, the development of marine environmental public interest litigation (MEPIL) is relatively slow compared to land environmental public interest litigation. It also faces many challenges due to the complexity of marine environmental issues, the diversity of marine management institutions, and the particularities of marine justice.

The MEPIL is also a measure for China to fulfill its obligations under international treaties regarding marine protection and climate change, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (Moynihan and Magsig, 2020). The MEPIL in China exhibits a judicial-led characteristic, with the procuratorial organs playing a key role. This institution thus provides more judicial support for the implementation of China’s legislative, administrative, and market-based measures to protect the marine environment and ecosystem (Chang et al., 2020). The current research focuses on the theoretical analysis and practical investigation of MEPIL, including the qualification of environmental public interest litigation proceedings, litigation procedures, litigation jurisdiction, environmental damage compensation mechanisms, the procuratorate’s litigation status, personal litigation rights, and other related aspects. MEPIL faces some common problems of general environmental public interest litigation. For example, in the specialized study of marine public interest litigation, related research focuses on judicial practices and involves applying case analysis, comparative analysis, and other methods. While affirming the value of marine public interest litigation, the relevant research analyzes its main challenges. Relevant research is conducted on the litigation qualifications of social organizations and the jurisdictional issues of civil, administrative, criminal, and incidental civil cases. Yang (2023) emphasized that it is more conducive for administrative authorities responsible for marine environmental protection to initiate MEPIL, thereby leveraging their unique advantages and maximizing the unification of efficiency and justice in public interest litigation for environmental protection. Therefore, it becomes an inevitable practical need to establish state organs as the sole qualified subjects for public interest litigation concerning marine environmental protection. However, with the revision of the Marine Environmental Protection Law in 2023, procuratorial organs have been authorized to file lawsuits when related authorities refuse to do so. Zhai (2024) found that the number of cases initiated by marine executive departments is relatively limited, and jurisdictional matters remain a challenging issue. It is noted that a set of systematic and coordinated rules is necessary to overcome the obstacles. This research provides valuable insights into analyzing the practical challenges of implementing MEPIL. The effectiveness of MEPIL is also influenced by the general difficulties faced by the public in litigation, such as the timing of judicial intervention, uncertainties in litigation outcomes, and the scope of protection (Chu, 2023; Qi, 2018). In addition, narrow subject qualifications, extensive restrictions on environmental NGOs, and high litigation costs can also limit the function of MEPIL (Li and Song, 2024).

Relevant research provides a crucial foundation for the development of this study. Disputes and ambiguities exist in the interpretation of MEPIL-related rules and judicial practices. The MEPIL system needs to be improved to address the institutional challenges, such as standing and jurisdiction issues posed by the differing judicial arrangements for land and marine environmental protection, as well as the generally cross-regional nature of marine environmental issues. This study further focuses on typical cases of MEPIL, carries out a more systematic case review and summary, and analyzes the patterns and main problems of litigation qualification, jurisdiction, and ecological damage in practice. To enhance the judicial efficiency of MEPIL, this paper proposes key reform paths to address the institutional challenges. The second part of this paper introduces the case sources and sampling methods, providing an empirical data basis for the analysis presented. The third part of this paper examines the primary institutional challenges faced by MEPIL in China, its practical performance, and the significant harm it has caused. The fourth part of this paper proposes a corresponding reform path based on legal theory and practical needs to address institutional challenges and fully leverage the role of MEPIL in protecting the environment, restoring ecosystems, and controlling marine pollution and destruction.

2 Judicial landscape of MEPIL in China

To reflect the practice and existing problems of MEPIL in China, this paper examined related judicial cases using a combined method of content analysis and comparative analysis. To comprehensively explore the practice and existing challenges of marine environmental public interest litigation in China, this article employs an empirical research methodology.

Firstly, by utilizing databases such as “China Judgments Online”, “Peking University Law Database”, and “China Court Case Database”, keyword searches were conducted using terms like “environmental pollution”, “ship oil spill”, “illegal fishing”, “illegal sand mining”, “harm to precious and endangered wildlife”, “marine environmental civil public interest litigation”, “criminal public interest litigation attached to criminal cases”, and “administrative public interest litigation”. The case types were restricted to “maritime and commercial disputes”. Additionally, the study was supplemented with typical cases published by the Supreme People’s Court, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate Gazette, and the China Maritime Court Case Database.

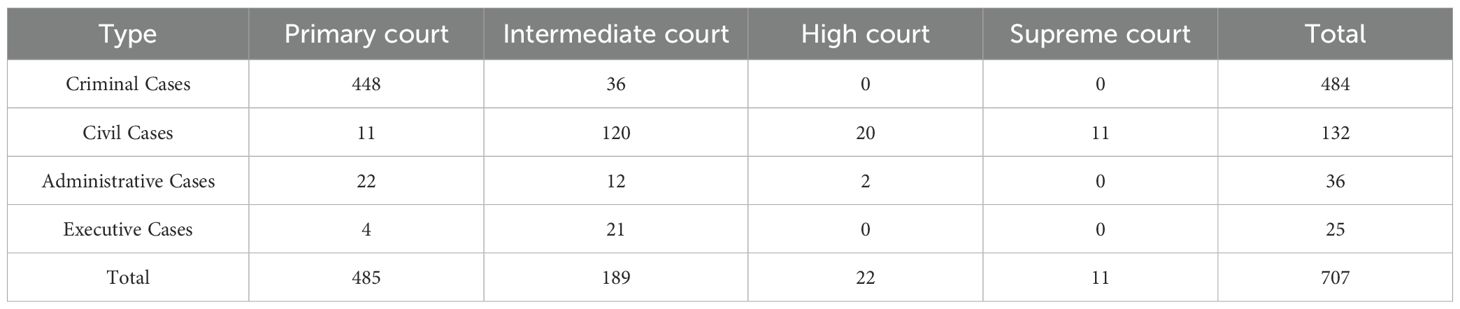

After completing the preliminary screening and review process, 707 legal case documents have been successfully identified and compiled. These documents encompass a diverse range of litigation types, specifically including criminal, civil, administrative, and executive cases dealing with the enforcement of court judgments (See Table 1).

A primary analysis of the cases related to MEPIL reveals that nearly 65% of the total cases are criminal cases or cases with the primary court as the court of first instance. The distribution of the cases suggests that MEPIL is currently involved in crimes related to the marine environment and natural resources, which are typically handled by the procuratorial organ and adjudicated by primary courts initially. By contrast, only 18.7% of the cases are civil ones, and this reflects that the civil procedure hasn’t been the main judicial approach to protect the marine environment and natural resources. Administrative cases account for the smallest portion of cases. This suggests that judicial supervision on administrative performance is relatively weak. A majority of administrative cases had been addressed through the procuratorial suggestion procedure (Zheng and Hu, 2024).

Secondly, the authors independently code the selected samples. Each coder must strictly follow the pre-established coding scheme, which clearly defines various codes along with their specific contents and determination criteria. This ensures that all coders have a unified basis and reference during the coding process, thereby reducing coding inconsistencies caused by individual differences in understanding. After the coding is completed, the coders review the documents with inconsistent coding results and determine the proper code through discussion. During the case selection process, if multiple court judgments existed for the same case, only the most representative one was retained. Cases that did not fall under the category of marine environmental public interest litigation were rigorously excluded to ensure the professionalism and specificity of the research samples. A total of 218 valid and representative cases of marine environmental public interest litigation from the past decade (2014-2025) were selected for analysis. The case search concluded in July 2025.

Thirdly, based on these 218 valid and representative cases, after further screening and excluding 59 cases of marine environmental administrative public interest litigation and 72 cases of marine environmental criminal public interest litigation attached to criminal cases, 87 cases of marine environmental civil public interest litigation concerning the plaintiff were identified.

However, it should be noted that the selected samples do not cover all MEPIL cases, as there are still cases that have not been recorded by the relevant databases or issued by official platforms. This is a limitation of the current work. Additionally, cases that are still under trial are excluded from the sample, and these new cases may offer different perspectives compared to the selected ones.

Based on the selected cases, a further exploration of the plaintiffs, jurisdiction, and liability is helpful to describe the characteristics of civil MEPIL in practice. This systematic examination not only clarifies the practical application of relevant legal arrangements but also provides valuable insights for improving the judicial handling of specialized environmental cases.

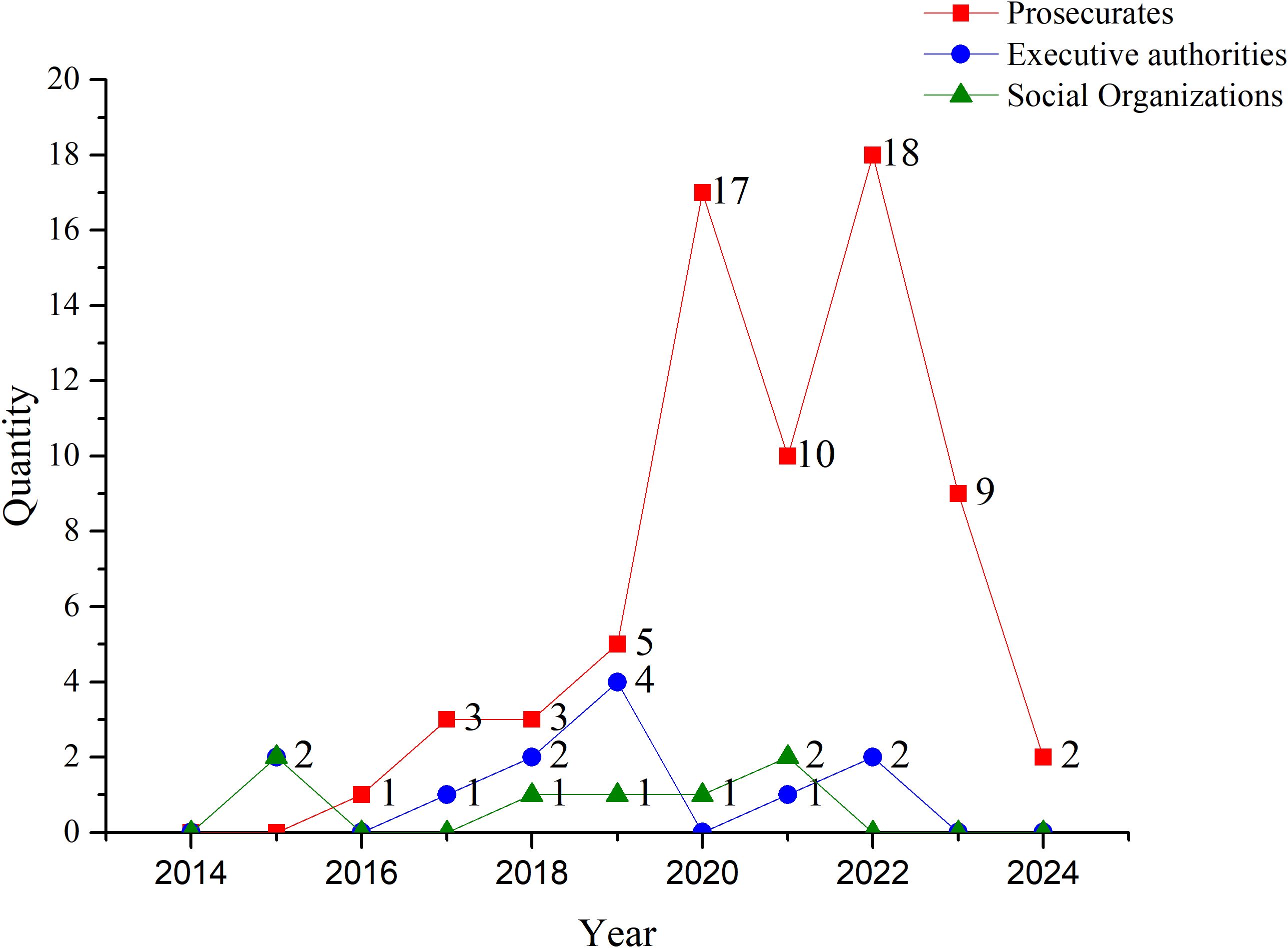

2.1 Types of plaintiffs

Social organizations have consistently played a pivotal role as the primary driving force behind environmental public interest litigation efforts. These non-governmental entities have been at the forefront of initiating legal actions to safeguard ecological interests. Their active participation has significantly contributed to the development and enforcement of environmental laws, ensuring that public environmental rights are effectively protected through judicial channels. However, as the rights of legal action by social organizations in MEPIL haven’t been stipulated, the public authorities continue to maintain their dominant position in related cases (See Figure 1). Before 2017, the primary body responsible for marine supervision and administration was the Bureau of Marine Fisheries, with other subjects being relatively rare. Social organizations have often acted as the primary body of prosecution, but the outcome is frequently not accepted or rejected by the trial court. Since 2017, procuratorates have emerged as the leading force in marine environmental civil public interest litigation, with the proportion of litigants participating as prosecution subjects reaching 80% (Wang and Zang, 2025).

From the analysis of the overall cases, it is clear and intuitive that 2017 marks the “starting point” for prosecutorial MEPIL to safeguard public interests. The reason is that the Civil Procedure Law is being amended that year, thus promoting the procuratorates as the prosecution subject to achieve a breakthrough of “zero to one”. Between 2014 and 2017, there were only 9 civil MEPIL cases. After 2017, the number of civil MEPIL cases showed explosive growth.

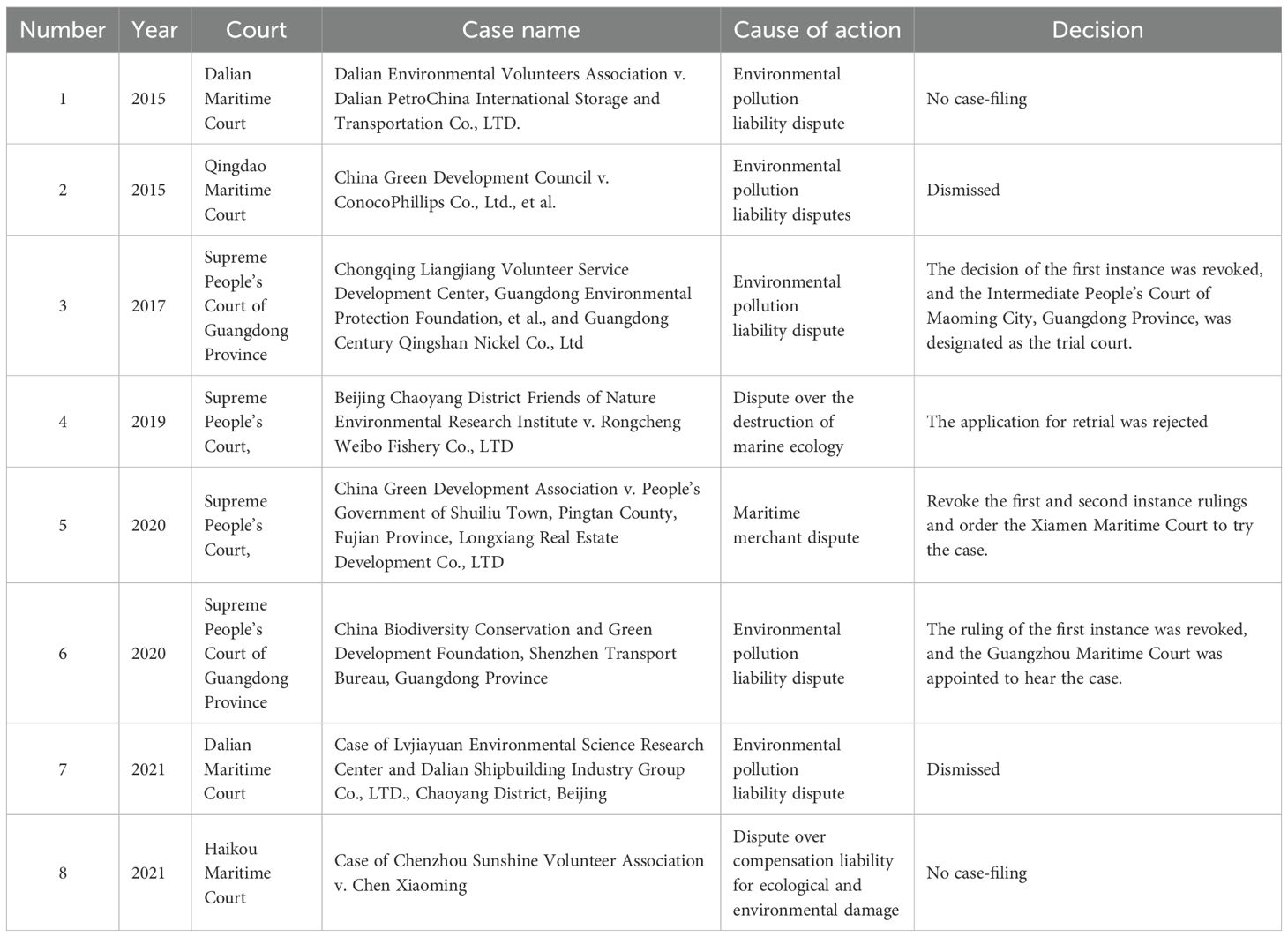

Social organizations have also been attempting to participate in marine environmental civil public interest litigation as the primary prosecution body, as shown in Table 2. Although marine supervision and administration have expanded the Marine Police Bureau and the Ecological Environment Bureau as legal prosecution subjects, negative litigation still persists. In an illegal marine dumping case, the procuratorate suggested in writing that the Haikou Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning (which undertakes the relevant functions of the former Bureau of Oceans and Fisheries) initiate the marine ecological environment damage compensation procedure under the law. However, the bureau replied that, due to its ongoing institutional reform and lack of legal professionals and litigation experience, it requested the procuratorate to file a civil public interest lawsuit (Supreme People’s Procuratorate of China, 2021).

Through the empirical analysis of the above cases, executive authorities continue to exhibit a negative attitude toward litigation. This phenomenon seriously hinders the development of marine environmental protection work. Suppose social organizations are excluded from civil public interest litigation on the marine environment. In that case, it will narrow the space for social forces to protect the marine ecological environment, which is not conducive to overall environmental protection.

In the Case of Lvjiayuan Environmental Science Research Center and Dalian Shipbuilding Industry Group, the Dalian Maritime Court dismissed the plaintiff’s complaint based on the following logic: The plaintiff did not clearly state the basis of its claim. Suppose the plaintiff initiated this lawsuit based on Article 89, Paragraph 2 of the Marine Environmental Protection Law, since the plaintiff is not a department exercising the supervision and management rights of the marine environment per the Marine Environmental Protection Law. In that case, the plaintiff is not a qualified subject to initiate this lawsuit. Suppose the plaintiff initiated this lawsuit based on Article 58 of the Environmental Protection Law, Article 55 of the Civil Procedure Law, and the Interpretation on Environmental Public Interest Litigation. In that case, this case should be under the jurisdiction of intermediate or higher People’s Courts, and this case will not fall within the jurisdiction of the Dalian Maritime Court. The plaintiff argued that the infringement involved in this case occurred on land and at the intersection of land and sea, and the consequences of the infringement occurred both at the intersection and in the sea. The current judicial policy is that environmental protection organizations can file public interest litigation cases involving damage to the junction of land and sea. However, the court decisions it cited as evidence were all civil rulings made by the Higher People’s Court of Guangdong Province, instructing the Intermediate People’s Court of Maoming or the Guangzhou Maritime Court to hear the cases. It can be seen that the claim that environmental protection organizations can file public interest litigation cases involving damage to the junction of land and sea is currently only a judicial viewpoint of the Higher People’s Court of Guangdong Province and is not an effective judicial interpretation. Moreover, the Higher People’s Court of Guangdong Province has not reached a consensus on whether such cases should be exclusively under the jurisdiction of maritime courts. Therefore, the plaintiff’s claim that it can file this public interest litigation case involving damage to the junction of land and sea has no legal basis.

2.2 Structure of jurisdiction

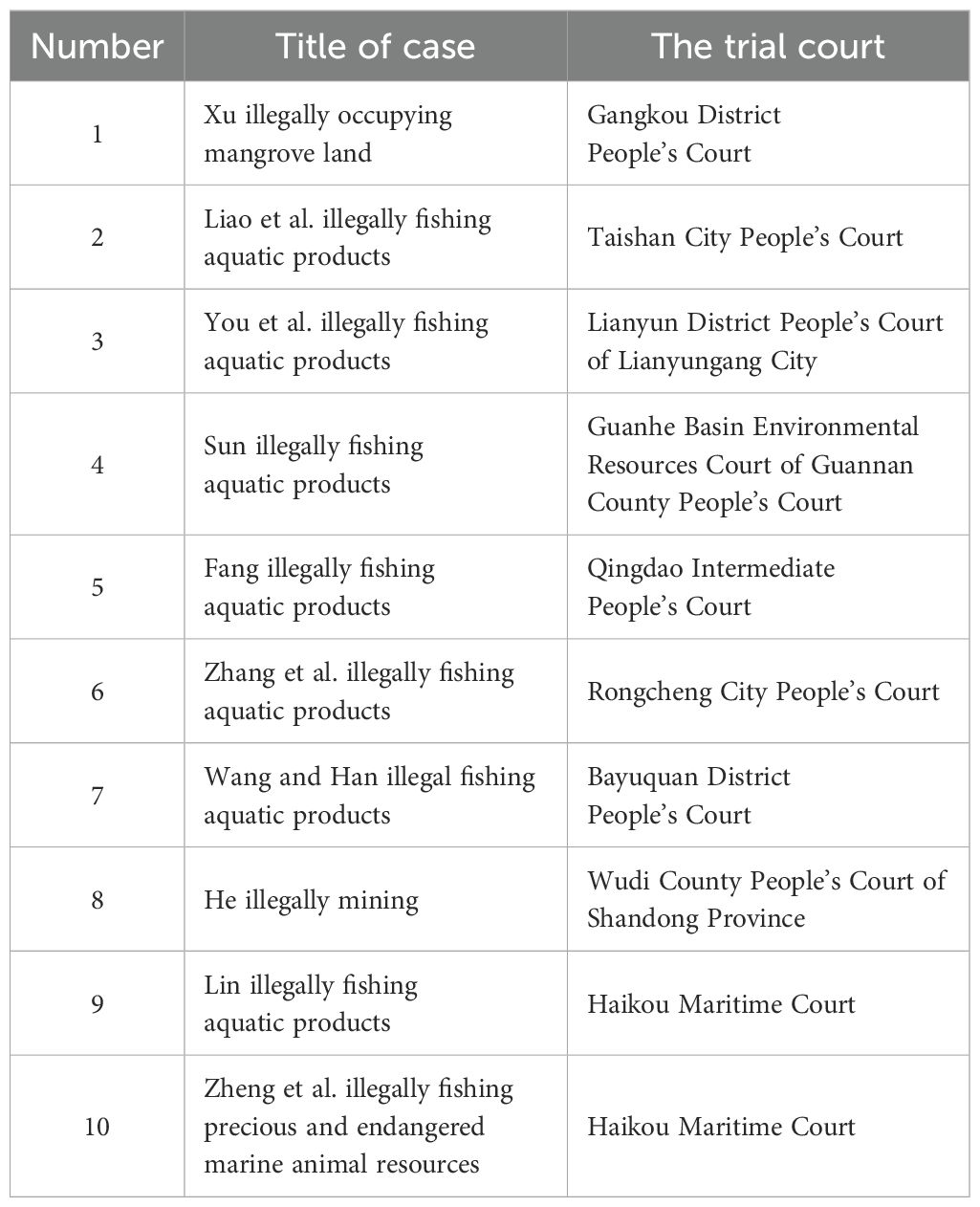

Since the environmental governance system in China exhibits a distinct land-sea division pattern, with separate regulatory frameworks and administrative bodies governing terrestrial and marine environments respectively, MEPIL cases consequently demonstrate a rather complex and multifaceted implementation status. MEPIL cases are mainly related to the jurisdictions of specialized marine courts, environmental courts, and ordinary courts (Khan and Chang, 2018). Cross-regional marine pollution may lead to more complex jurisdictional conflicts (Khan and Ullah, 2024). When the procuratorial organs initiate civil public interest litigation concerning pollution damage to sea areas caused by ship sewage discharge, ship production at sea, or ship operation, they shall file a lawsuit with the maritime court that has territorial jurisdiction. However, according to Article 5 of the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Public Interest Litigation Cases” and Article 6 of the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation Cases”, it cannot be ruled out that such cases may be under the jurisdiction of ordinary courts at or above the intermediate level (Han and Yan, 2024). If the procuratorates bring marine environmental criminal cases with civil public interest litigation, it is under the jurisdiction of the court that tries criminal cases. Most cases fall under the jurisdiction of the primary court and the intermediate people’s court, as the maritime court lacks jurisdiction to try criminal cases, as shown in Table 3. However, in February 2017, the Supreme People’s Court designated Ningbo Maritime Court as the country’s first pilot maritime court for maritime criminal cases. The maritime court can have jurisdiction over prosecuting crimes such as the illegal acquisition, transportation, and sale of precious and endangered wild animals, as well as traffic accidents and significant liability accidents (Shao, 2020). In 2020, the Haikou Maritime Court filed and accepted the first maritime criminal case, taking the lead in establishing a maritime criminal division among national maritime courts. This division is primarily responsible for hearing maritime criminal cases of first instance (Zhu, 2022). The Guangzhou Maritime Court accepted the first criminal case of endangering precious and endangered wild animals at sea in 2023. The Nanjing Maritime Court accepted the first illegal mining case in 2023, involving Li and two others. Currently, four maritime courts are attempting to hear maritime criminal cases, thereby ensuring that the criminal and public interest litigation procedures involved in the same criminal act are more closely linked and smoothly integrated.

2.3 Mode of liability

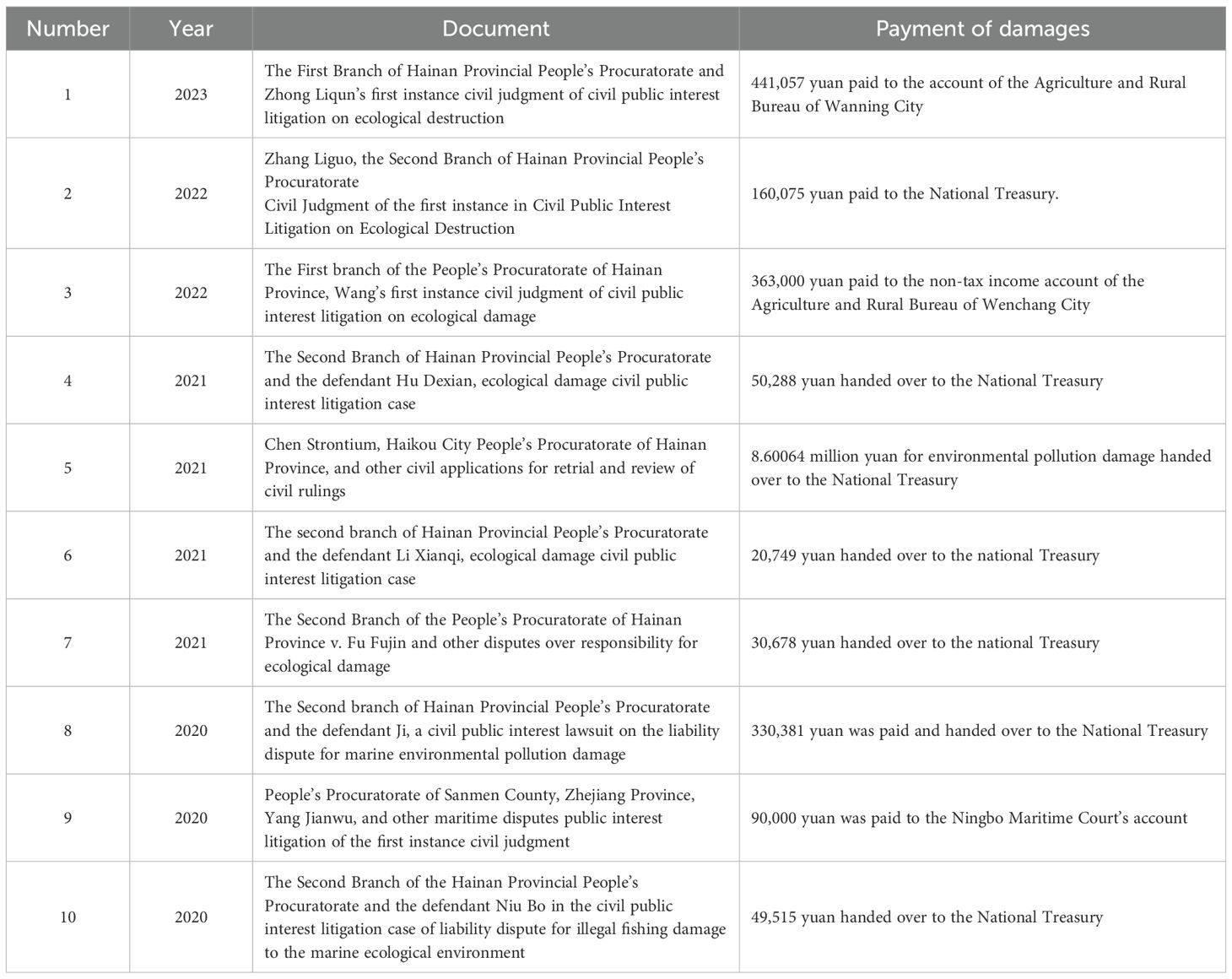

The primary objective and fundamental mission of MEPIL is dedicated to the comprehensive restoration and rehabilitation of ecosystems that have suffered degradation or damage. This includes not only repairing impaired natural resources but also revitalizing the overall environmental conditions that have been negatively impacted by human activities or natural disasters (Liao, 2020). According to current laws, regulations and technical standards, the scope of compensation for marine ecological damage mainly includes costs for pre-measures, expenses for marine ecological restoration and recovery, losses during the recovery period, investigation and assessment fees, costs for rebuilding or replacing the ecosystem, and losses caused by permanent damage, etc. From the perspective of liability categories, the compensation methods of MEPIL are diverse and varied, primarily including payment of ecological and resource damage compensation and assessment costs, making public apologies to society, value-added and release to restore ecology, participation in marine environmental and ecological publicity, and performing social services. According to the above collection of 218 related cases, in the screening, excluding cases dismissed by the court, 173 valid judgments can be obtained. 75% of the decisions were monetary compensation. Due to the long duration and uncertainty of marine ecological environment restoration, in practice, those responsible are often required to pay compensation for damage to the marine ecological environment. A further analysis of the monetary compensation cases decided by the court reveals that most courts specify the compensation that should be paid to the National Treasure in their judgments. Still, this financial account belongs to the unified collection and expenditure, and whether it will be used for marine ecological restoration in the future cannot be determined, as shown in Table 4. Monetary compensation can increase the cost of marine development and utilization activities, such as reclamation through economic leverage, and restrict the model of marine engineering. Still, it is challenging to regulate the use of money and repair the damaged ecology promptly (Li and Li, 2015). Firstly, the ultimate purpose of compensation for marine ecological damage is to protect and restore marine habitats, thereby realizing the sustainable use of marine resources. However, compensation based on economic considerations makes it difficult to ensure that the compensation funds are fully utilized in marine ecological protection and restoration, thereby making the overall effect of ecological compensation challenging to achieve. Secondly, the typical form of economic compensation remains government financial transfer payments, due to the lack of market mechanisms and the limited financial resources of central and local governments. There is no law to ensure adequate compensation funds, and long-term government-led funding will create an imbalance between government compensation and market compensation. It is challenging to leverage the advantages and characteristics of the market compensation mechanism. Finally, the compensation method has not played a comprehensive role, and non-economic compensation and habitat restoration are relatively weak, especially habitat restoration, which has not fulfilled its due role in compensating for marine ecological damage (Yin and Xu, 2021).

3 Major institutional challenges in China’s MEPIL

The judicial landscape of MEPIL reveals that uncertainties and divergences still exist in arrangements regarding the standing, jurisdiction, and liability within the MEPIL system. These gaps impact the effectiveness of judicial protection for the marine environment and its natural resources. The deficiencies in practices reflect irrationality in the institutional design for MEPIL. In fact, China’s MEPIL has developed based on public interest litigation and a relatively land-sea-divided governance context. Due to the immature characteristics of the MEPIL system, numerous institutional challenges exist, with the major ones focusing on rules regarding plaintiffs, jurisdiction, and compensation.

3.1 Disputes on the qualification and priority of plaintiffs

The qualification and priority of plaintiffs in MEPIL cases play a crucial role in determining which parties are legally authorized to initiate judicial procedures for the protection of the marine environment. The criteria for plaintiff qualification typically involve demonstrating a sufficient connection to or interest in the marine environment at risk. At the same time, priority considerations help resolve conflicts when multiple parties seek to file similar claims. However, the inconsistency of legal provisions, ambiguity in the functions and responsibilities of marine authorities, and the lack of effectiveness of the priority rule for the right of action negatively affect the efficiency of the MEPIL judicial system.

3.1.1 The inconsistency of the legal provisions about the qualification of the plaintiff

Among the MEPIL cases mentioned above, the “Rongcheng Weibo case” underwent three trials and garnered widespread attention. Friends of Nature, the plaintiff in the initial case, filed a civil public interest lawsuit because the Weibo Company and others allegedly engaged in illegal fishing during the fishing ban period. The Qingdao Maritime Court of the first instance held that Article 58 of the Environmental Protection Law is a general provision for environmental civil public interest litigation and that paragraph 2 of Article 89 of the original Marine Environmental Protection Law is a special provision. According to the principle that special law is superior to general law, Friends of Nature is not qualified as a plaintiff; therefore, the court ruled to dismiss the lawsuit (Mi and Wang, 2023). The Court of Second Instance also ruled to dismiss the appeal on similar grounds. Friends of Nature applied to the Supreme People’s Court for a retrial, arguing that the provisions of Article 89 of the Marine Environmental Protection Law and Article 58 of the Environmental Protection Law were different in terms of the basis of claims, the means of relief and the scope of relief, and they did not constitute a relationship between the general law and the special law. As a result, it is an error in the application of the law for the original trial court to exclude social organizations as plaintiffs in litigation. The Supreme People’s Court still ruled against Friends of Nature because Article 89, paragraph 2, of the Marine Environmental Protection Law is a special provision on compensation for damage to marine natural resources and the ecological environment (Wu, 2015).

In China’s judicial practice, the people’s courts have unanimously held that the current Marine Protection Law is a special law under the Environmental Protection Law. The principle that the special law is superior to the general law excludes the qualification of the marine civil public interest litigation filed by social organizations as the main body of the prosecution. Based on this, the applicable relationship between the Marine Protection Law, the Civil Procedure Law, and the Environmental Protection Law can be clarified to consider the systemic effect of legal norms.

3.1.2 The ambiguity in marine environmental supervision and management agencies’ functions and responsibilities

In MEPIL cases, the damage caused by the same infringement often involves multiple marine environmental supervision and management agencies. However, there is still an unclear division of functions among various agencies. Specifying each damage compensation to a specific functional unit is challenging, and a phenomenon of “all want to regulate” and “none want to regulate” will occur. The institutional reform in 2018 and the promulgation of the Coast Guard Law in 2021 granted coastal cities the authority to establish marine law enforcement agencies tailored to local conditions, resulting in diverse composition patterns and complex names for local marine law enforcement agencies (Wang et al., 2024). According to the Marine Environmental Protection Law, in addition to the maritime and coastal police, various sectors, including ecological environment, natural resources, transportation, fisheries, and others, have responsibilities for marine environmental protection. Based on the imperfect responsibility system of marine administrative law enforcement, the procuratorates often need to issue procuratorial suggestions to multiple administrative organs in handling administrative public interest litigation cases in the marine field. For example, illegal sand mining can lead to the loss of mineral resources, changes in seabed topography and coastline, and also cause deterioration in water quality and the loss of marine living resources. The marine supervision and management agencies include natural resources and planning, ecological, environmental protection, and agricultural and rural departments. It is difficult to identify the responsible central departments (Shi, 2020). The marine law enforcement system needs to be streamlined, and the target of the procuratorial suggestions needs to be strengthened.

3.1.3 Lack of effectiveness of the priority rule for the right of action

In marine environmental protection work, the marine environmental supervision and management department itself is more professional and authoritative, making it easier to identify clues about marine ecological damage, which has obvious inherent advantages compared to other litigation subjects. According to Article 114 of the new Marine Environmental Protection Law, the procuratorate files a lawsuit if the marine environmental supervision and administration department does not file a lawsuit. Suppose the Marine Environmental Supervision and Administration Department files a lawsuit. In that case, the procuratorate can support the prosecution, indicating that the marine environmental supervision and administration department has priority status in exercising its right of action. The procuratorate is the second in line. However, according to the analysis of the above 87 cases, the procuratorates hold a central force position in the MEPIL. In land-sea crossing public interest litigation, social organizations also have the priority of filing a lawsuit. However, in practice, during the pre-litigation announcement period initiated by the procuratorates, most of the prescribed authorities and social organizations neither provided written responses to the procuratorates’ announcements nor filed lawsuits within 30 days after the period expired. Taking the guiding cases issued by the Supreme People’s Court as typical examples, the procuratorates have all fulfilled the pre-trial supervision procedures under the law and made announcements accordingly. Procuratorates generally announce their plans to file environmental civil public interest lawsuits on national websites or in newspapers. The announcement procedure expands the scope of influence of public interest litigation cases, allowing social organizations to overcome geographical restrictions and maximize the possibility of prosecution. However, due to the lack of deterrence and coercive force of this pre-litigation procedure, the enthusiasm of social organizations or relevant authorities to file environmental civil public interest lawsuits did not improve after the announcement. Setting up the pre-litigation announcement procedure is to maintain the modesty of the procuratorates in the litigation. At this point, the pre-litigation announcement procedure has not reached its target value, and most of the final subjects of prosecution are still the procuratorates (Li and Wu, 2024). Therefore, the arrangement of the procuratorates’ subsequent right to sue has not played a significant role.

3.2 The complexity of MEPIL jurisdiction

Marine environment and natural resource protection involves both environmental and marine issues. Within the context of judicial specialization, China has established specialized courts for environmental and maritime issues. The hybrid nature of the marine environment and natural resource issues causes judicial conflicts, and the land-sea divided feature of environmental governance makes the conflicts more complicated.

3.2.1 The connection points of the MEPIL jurisdiction are unclear

According to the above analysis of the legislative status quo, Article 283 of the Interpretation of the Civil Procedure Law stipulates that the jurisdictional connection point of the maritime court is “the place where pollution occurs, the place where damage results, or the place where preventive measures are taken”. Article 2 of Provisions on Several Issues Concerning the Handling of Marine Natural Resources and Ecological Environment Public Interest Litigation Cases (2022) stipulates that the jurisdictional connection point of the maritime court is “the place where the damage occurs, the result of the damage, or the place where preventive measures are taken”. Article 7 (2) of the Law on Special Maritime Procedures stipulates that the connection point under the jurisdiction of the maritime court is “the place where the pollution occurs, the result of the damage, or the place where preventive measures are taken”. Article 6, paragraph 1, of the Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Trial of Cases Concerning the Sea Areas under China’s Jurisdiction stipulates that the connection point of the maritime court within the sea areas under China’s jurisdiction is “ having jurisdiction over the sea area”, and paragraph 2 stipulates that the connection point of the maritime court is “jurisdiction over the sea area or the place where preventive measures are taken” when the pollution accident occurs outside the sea areas under China’s jurisdiction. Although China’s marine environmental laws and judicial interpretations provide jurisdictional paths that point to the jurisdiction of maritime courts, the specific application circumstances and jurisdictional connection points are not the same, resulting in a vague space of which maritime court will ultimately be under the MEPIL jurisdiction, and even give rise to jurisdictional conflicts between maritime courts in specific cases (Han and Yan, 2024). To improve the jurisdiction system of marine environmental civil public interest litigation, it is urgently necessary to provide unified provisions on the connection points.

3.2.2 Jurisdictional conflicts arising from MEPIL collateral in criminal proceedings

The civil litigation attached to criminal cases complicates the jurisdiction of public interest litigation related to the marine environment. On the one hand, the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law to Procuratorial Public Interest Litigation Cases stipulates that “civil public interest litigation cases attached to criminal cases filed by the People’s Procuratorate shall be under the jurisdiction of the people’s court that tries criminal cases.” Therefore, in principle, criminal cases with civil public interest litigation must also be under the jurisdiction of the court that hears the criminal case. This has formed the special jurisdiction rules of civil public interest litigation. In practice, criminal cases are primarily under the jurisdiction of grassroots courts, and the prosecution and trial of environmental public interest litigation cases of criminal attachment have become grassroots (Shi and Hou, 2023). However, this provision conflicts with the general rule that civil public interest litigation cases are typically under the jurisdiction of the intermediate court, while marine public interest litigation is generally under the jurisdiction of the maritime court. If the procuratorate initiates criminal and civil public interest litigation, the criminal and civil aspects fall under the jurisdiction of the basic court. Suppose a public interest and criminal lawsuits are filed separately by the procuratorate. In that case, the grass-roots court will try the criminal part, while the intermediate court handles the civil part. However, having different courts for the criminal and civil aspects of the same case will increase judicial costs, reduce judicial efficiency, and may cause conflicts due to differing requirements, such as proof standards.

3.2.3 Jurisdictional disputes in land-sea crossing public interest litigation

Jurisdiction over land-sea crossing environmental damage is another issue within the judicial system. In a marine dumping case brought by Chongqing Liangjiang Volunteer Service Development Center and Guangdong Provincial Environmental Protection Foundation, the Guangdong Provincial High People’s Court ruled that the defendant’s behavior of dumping slag to fill coastal beaches, wetlands, and mangroves not only caused damage to the marine ecological environment, but also caused damage to the terrestrial ecological environment, and recognized that environmental organizations qualify for public interest litigation. Make an order to cancel the civil order of first instance and order the court of first instance to try it. However, it should be noted that whether social organizations are qualified plaintiffs and their jurisdiction in land-sea cross-type environmental public interest litigation is also a matter of controversy. In the civil ruling of the first instance of the environmental pollution liability dispute between the Green Home Environmental Scientific Research Center of Chaoyang District of Beijing and Dalian Shipbuilding Industry Group., the Dalian Maritime Court held that the qualification of environmental organizations to sue for environmental public interest litigation at the interface of land and sea is only a local practice. There is no clear judicial interpretation to clarify the matter. It cannot yet bring a case involving the land-sea junction to the maritime court. Still, if a social organization claims it is not a maritime public interest litigation, it can bring a case to a non-maritime court with jurisdiction. This practical dispute highlights that the jurisdiction of land-sea cross-type environmental civil public interest litigation remains unclear, and the procuratorate will face a dilemma regarding whether to sue the maritime court or other local courts. Some scholars believe that land-sea cross-type environmental public interest litigation cases can be determined based on the location where the damage occurs. If the damage occurs at sea, it falls within the scope of marine environmental civil public interest litigation. When damage occurs on land, it falls within the scope of environmental civil public interest litigation (Li and Shao, 2024). However, this dual mechanism design compromises the integrity of marine environmental protection and is ineffective in addressing environmental public interest litigation jurisdiction at the land-sea junction. Some scholars also believe that land-sea cross-pollution environmental damage can be categorized into marine and land environmental damage, falling under the jurisdiction of the relevant intermediate court or maritime court. Still, this path can easily lead to repeated litigation, so the maritime court should have exclusive jurisdiction over cross-pollution environmental public interest litigation in a particular region (Chu and Zhao, 2023).

3.3 Improper arrangements for supervising marine ecological damage compensation

The huge amount is one of the characteristics of marine ecological damage compensation. In some cases, the compensation is as high as millions or even tens of millions, which is often difficult to utilize at once, and supervision requires a prolonged period. How to manage and use damages is also a prominent problem in the practice of MEPIL. At present, there are two main management modes for ecological damage compensation in various places: one is to turn over to the national Treasury or as non-tax revenue for local governments, and the other is to set up special accounts, including special management accounts for governments, courts, and procuratorates, and special funds for environmental public welfare organizations. Taking the court as an example, after the procuratorate files a public interest lawsuit in the court, the court adjudicates the judgment, and the defendant pays the compensation directly to the special deposit account for the execution of the court. Still, there is no explicit provision on how to use the funds, which quickly leads to unclear categories for this part of the funds and prevents it from fulfilling its intended utility. There are no explicit provisions to supervise the effective use of funds in the later period. From the perspective of judicial case handling procedures, the handling period of public interest litigation cases involving sea torture and attached people, such as illegal fishing and stealing sea sand, is long. Taking the case handling situation in L City as a statistical sample, the average time from the filing of a criminal case by public security organs to the judgment of the case is 25 months. Among them, the investigation process of public security organs takes an average of 15 months, the investigation process of procuratorates takes an average of 4 months, and the trial process takes an average of 6 months. The case handling cycle is too long, and the utilization efficiency of the damages implemented after the court judgment takes effect is low, which makes it challenging to repair the damaged public welfare restoration promptly.

4 The reform approaches for China’s MEPIL system

The institutional challenges necessitate proper reforms in the MEPIL system, based on a thorough analysis of related jurisprudence and practical needs. The key points lie in the rules for standing to bring a lawsuit, jurisdiction regarding MEPIL, and marine ecological damage compensation funds.

4.1 Clarify the rules for the standing to bring a lawsuit

Identifying eligible plaintiffs involves specifying which entities or individuals have the legal right to initiate litigation and providing scenarios where multiple parties may qualify as plaintiffs. More explicit rules for standing to bring a lawsuit will ensure consistency and fairness in legal proceedings, and enhance the efficiency of the judicial process.

4.1.1 Strengthen coordination among relevant laws and regulations

First of all, according to Article 92 of the Legislation Law, the legislative purpose of the “special law is superior to general law” is that there must be “inconsistency” between legal norms. There is no conflict of laws between the Marine Environmental Protection Law and the Environmental Protection Law, or the Marine Environmental Protection Law and the Civil Procedure Law. In this regard, the principle that a special law is superior to a general law or a new law is superior to an old law cannot be mechanically applied to determine the applicability of a specific law directly and to determine which legal norms to use according to the actual situation (Yang, 2021). Secondly, from the perspective of textual interpretation, Article 114, paragraph 2 of the Marine Environmental Protection Law stipulates that the special subject of claims shall be “the department that exercises the power of marine supervision and administration by the provisions of this Law shall make claims on behalf of the state”. The expression “on behalf” is not an exclusive and exhaustive list of authorizations; there may also be other legal provisions that bring corresponding MEPIL (Chen and Bai, 2018). Finally, suppose the legislature’s intention in the latest Marine Environmental Protection Law is to deny social organizations as the prominent plaintiffs. In that case, Article 58 of the Environmental Protection Law should be amended to include the provision that “regarding marine environmental damage, the relevant authorities may bring a lawsuit to the people’s court following the provisions of the Marine Protection Law” (Wu, 2019). In this way, the application relationship between the two laws can be clarified through the causative provisions, thus excluding the application of social organizations in the field of marine environmental protection. However, it is worth noting that the subject of public interest litigation has generally evolved from citizens to social organizations and State organs (Zou and Niu, 2023). The experience of public interest litigation in India demonstrates a supplementary role for social organizations, as they can assist the procuratorial organ in identifying violations and enforcement (Wang, 2024). To promote broader and deeper participation of non-state actors in ocean governance, it’s necessary to provide social organizations with the right of action in the MEPIL (Cao and Chang, 2023).

4.1.2 Provide equal rights of action to enhance judicial efficiency

According to the Organization Law of the People’s Procuratorates, revised in 2018, procuratorates safeguard national and social public interests and initiate public interest litigation per the law. As a legal supervisory organ, the procuratorate undertakes the statutory duty of preserving the international interests of the land and sea environment, resources, and public social interests. Some scholars maintain that procuratorates are the most appropriate subjects for litigation, as they represent national and social public interests (Research Group of Panyu Procuratorate, 2011). The public interest litigation initiated by the procuratorate is an act of fulfilling the statutory duty. Procuratorates’ public interest litigation rights are non-renounceable, non-transferable, and non-entrustable (Liu, 2021). Procuratorial public interest litigation expands the connotation and extension of the procuratorate’s legal supervision function. Compared to general public interest litigation subjects, procuratorates have significant advantages in collecting clues, conducting investigations, gathering evidence, and supervising litigation, among other areas. Procuratorates can better safeguard public interests by fully leveraging their initiative (Ma, 2023). The relevant administrative agencies themselves bear the responsibility for environmental management, which primarily achieves the objectives of ecological resource management by exercising the power of enforcement and punishment. In practice, there is also a lack of social organizations to respond to the prosecution during the implementation of pre-prosecution announcements (Sun and Zhang, 2023). The design of prioritizing other organizations has not been effective. Moreover, after the procuratorate has conducted the preliminary investigation, the litigation carried out by different organizations will also lead to the waste of judicial resources and affect the efficiency of case handling (Liu and Zhang, 2023). Considering that the public interest litigation right of procuratorates is more obligatory than the litigation right of other organizations, as well as the limitations of social organizations in terms of litigation qualifications and litigation resources in practice, procuratorates should be given the same legal precedence as other litigation subjects, so that they can more effectively and actively perform their statutory functions and powers, and avoid unnecessary continuation of environmental damage, the expansion of damage or the loss of evidence. Therefore, the procuratorate should not urge the marine environment administrative organ to use public announcements (Yu, 2021).

4.2 Improve the jurisdiction rules about MEPIL

The complex and multi-tiered jurisdictional framework governing maritime matters often results in considerable confusion and uncertainty regarding which particular court holds the appropriate legal authority to adjudicate cases involving breaches of marine environmental protection laws. This complexity creates a legal gray area where multiple courts might potentially claim jurisdiction while none can definitively assert exclusive authority over such environmental violation cases. Therefore, legal reforms concerning jurisdiction rules are urgently needed to establish a more efficient legal framework.

4.2.1 Promote the centralized jurisdiction of the maritime court

A fragmented structure characterizes China’s marine governance system. From an administrative perspective, at least four departments are responsible for marine environment management, including the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the Ministry of Natural Resources, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, and the China Coast Guard. The land-sea division environment mechanism makes marine environment governance more complicated. Although marine management has shifted from comprehensive management to industry-specific management, an industry management system lacking coordination is unable to meet the demands of complex and cross-domain marine affairs governance. Under the circumstances where comprehensive management is relatively weakened, the strengthened industry-oriented marine management system is at risk of reverting to fragmented marine governance (Mao, 2022).

The diversification of MEPIL jurisdiction has exacerbated the fragmentation of marine governance in China. Following the trend of judicial specialization, to improve trial efficiency, China has implemented a criminal, civil, and administrative “three-in-one” system in the trial of environmental resources. In the maritime courts, the Ningbo, Haikou, and Nanjing maritime courts have also been piloted to implement the three-trial integration of maritime trials, which is of great significance in strengthening the function of special maritime jurisdiction. This trial reform measure is conducive to establishing a comprehensive and multidimensional judicial protection system for marine natural resources and the ecological environment, thereby enhancing the efficiency and professionalism of maritime trials and unifying judicial standards to strengthen judicial protection of maritime rights and interests. After more than 30 years of development, China has become the country with the largest number of specialized maritime tribunals and the highest volume of maritime cases accepted globally. It has a relatively complete maritime legal and judicial service guarantee system. The maritime courts possess extensive experience in handling marine environmental pollution cases and have professional advantages in investigation, evidence collection, damage identification, legal application, and liability determination. Finally, the Law on Special Procedures for Maritime Proceedings may be amended to clarify that maritime criminal cases fall under the jurisdiction of maritime courts, thereby providing a legal basis for these courts to have jurisdiction over and try both maritime criminal and civil cases simultaneously.

However, it should be noted that, compared to ordinary criminal cases, maritime criminal cases are more specialized and intricate, requiring judges to possess robust maritime knowledge as well as extensive experience in criminal trials. The staffing of maritime courts primarily consists of personnel specializing in civil maritime trials, with a notable absence of dedicated specialists in criminal trials. The shortage of personnel resources hurts the quality and efficiency of maritime criminal case adjudication. Furthermore, within the current organizational framework of the People’s Courts, maritime courts operate at a level equivalent to intermediate people’s courts. Maritime cases are initially under the jurisdiction of maritime courts, resulting in a relatively high focus on trial proceedings.

4.2.2 Provide jurisdictional exception in land-sea crossing public interest litigation

Under the “three trials in one” mode in maritime trials, the coordination of public interest litigation involving marine environmental supervision can be better coordinated, and civil cases collateral to maritime criminal cases can be brought under the jurisdiction of maritime courts. In principle, it is more appropriate for the maritime court to have jurisdiction over first-instance environmental damage cases. This arrangement is conducive to leveraging the experience and resource advantages of maritime courts in sea-related issues. It is conducive to unifying the jurisdiction level of sea-related public interest litigation to meet the requirements of first-instance environmental resources cases to be heard by the intermediate people’s court. However, where the damage and its consequences occur primarily on land, and it is more beneficial for enforcement or ecological restoration to be tried by the ordinary court or the Environmental Resources Court, the prosecution should be allowed to bring a case before the ordinary court or the Environmental Resources Court.

4.3 Optimize institutions for marine ecological damage compensation funds

The monetization of marine ecosystem services is a practical approach to guiding the genuine implementation of marine ecological compensation. Moreover, monetizing marine ecosystem services not only makes ecological restoration more flexible but also provides alternative sources of funds for ecological restoration beyond government transfer payments. In ecological compensation, introducing market mechanisms and involving the active participation of society, with the cooperation of multiple parties, enhances the completeness of the ecological compensation mechanism (Gao et al., 2019). Quantifying marine ecosystem services in monetary terms not only enhances the adaptability and responsiveness of ecological restoration initiatives but also provides a standardized framework for evaluating environmental costs and benefits. This methodology facilitates the process of making more informed decisions by converting intricate ecological relationships into quantifiable economic metrics, thus bridging the gap between environmental conservation and economic progress. The flexibility achieved through monetization enables dynamic adjustments to restoration strategies in response to evolving ecological conditions and shifting economic priorities. Given that monetary compensation is the primary form of reparation for marine ecological damage, more effective institutions are needed to utilize and supervise compensation funds.

4.3.1 Establish a compensation fund for ecological damage

Environmental public interest litigation primarily aims to restore the ecological environment rather than monetary compensation. To better repair the damaged marine environment and resources, it is necessary to establish a special fund for compensating ecological damage. The provincial financial department shall lead the establishment of an environmental damage compensation fund within its jurisdiction and set up a unique agency responsible for the daily operation and management of the fund. The key is to establish a suitable mechanism for connecting financial funds and marine ecological compensation, thereby breaking through the information barriers between law enforcement agencies and judicial organs. For example, Ningbo allows prosecutors to establish special accounts for public welfare funds and manage their allocation and distribution. It is clear that the administrative department is responsible for implementation, and the procuratorate is accountable for using funds and supervising the increase and release of funds to the administrative department. At the same time, a third-party supervision and enforcement mechanism could be established. When the practical judgment of MEPIL is made, the court will appoint a third party, or the responsible body will hire a third party to supervise the implementation of its remediation plan, who will report the supervision situation to the court or the accountable body promptly, to supervise and adjust the environmental resources remediation plan. Professional institutions could be held responsible for the specific management and operation of the fund, including assessing the damage to the ecological environment, determining compensation amounts, allocating and utilizing funds, and ensuring the effective utilization and equitable distribution of the fund. For example, the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 established the National Oil Spill Commission, which is responsible for organizing the assessment of damage to natural resources and marine ecology, collecting fees and compensation from responsible parties, and performing other related tasks. The act also requires the fund center to maintain an oil spill fund of 1 billion dollars to ensure sufficient funding for clean-up operations in the event of an oil pollution accident.

The issues of transparency, accountability, and stakeholder engagement are crucial to the efficiency of the compensation fund. Establishing a scientifically robust and rationally structured mechanism for planning and allocating funds to compensate for marine ecological damage is necessary. Based on a comprehensive evaluation of marine ecological damage and the development of restoration strategies, this mechanism will allocate and utilize funds in a manner that reflects the urgency and specific financial requirements of restoration initiatives. Priority should be given to ensuring adequate funding for the restoration of marine ecological damage in critical marine ecosystem areas, key species habitats, and projects with substantial socio-economic impacts, thereby maximizing the ecological and societal benefits derived from these funds. Additionally, it is necessary to establish a comprehensive supervision system for fund utilization, thereby reinforcing oversight throughout the entire process of fund management. First, an internal supervision mechanism should be established, with dedicated auditing and monitoring departments within the fund management institution conducting regular audits and inspections to ensure compliance with regulatory requirements in fund allocation and usage. Second, external supervision mechanisms should be incorporated, engaging government auditing departments, the public, and media entities to promote regular disclosure of fund income, expenditure, and utilization outcomes. This approach enhances transparency, builds public trust, and effectively prevents misuse and waste of funds.

4.3.2 Explore a deposit mechanism for marine ecological damage compensation

In contemporary judicial practice, after being held criminally responsible, infringers often exhibit a negative or resistant attitude toward fulfilling their obligations to restore the environment or compensate for environmental losses, showing reluctance to undertake ecological restoration or make compensation for ecological losses. As a result, civil judgments in such cases are frequently challenging to enforce. Article 52 of the Environment Protection Law (2014) provides that the State encourages the purchase of environmental pollution liability insurance. However, considering the absence of a compulsory legal basis, a narrow scope of insurance liability, a low insurance payout ratio, a high insurance premium rate, and an incomplete exclusion of liability, the participation rate in environmental insurance is very limited (Wu, 2025). The challenge of how to effectively urge infringers to fulfill their obligations regarding ecological environment restoration, while avoiding scenarios where the government bears the costs or the ecological environment remains unrepaired, remains an issue that requires further exploration in MEPIL cases. Procuratorates can communicate and coordinate with notarial organs to explore A supervision mode for establishing a marine public interest damage deposit. After the procuratorates ascertain the damage to the marine ecological environment through investigation and evidence collection, they may, by law, decide to accept a voluntary application from the offender to deposit the corresponding public interest damage compensation guarantee funds with the notarial organs. The situation where the perpetrator actively pays the compensation deposit can be regarded as a consideration factor for the leniency of a guilty plea. This practice prioritizes compensation for ecological damage before trial, to a certain extent, avoids the problem of a lengthy judicial case handling cycle, and can ensure the timely restoration of the damaged marine ecological environment.

5 Conclusion

Marine environmental public interest litigation protects the marine environment and resources of the Ministry of Justice. In the process of judicial intervention, the compatibility of the original judicial system and the marine management system with the MEPIL faces challenges. Judicial practice demonstrates that marine environmental public interest litigation is involved in the operation of litigation rights, jurisdiction, enforcement of decisions, and other related issues. The relatively separate environmental management systems for land and sea, the progressive process of judicial specialization, the reform of procuratorate functions, the lack of coordination in the legislative process, and the imperfect marine ecological restoration mechanism are the main reasons for the above problems. To further enhance the effectiveness of MEPIL, rationalize the operating mechanism of such litigation, and improve the judicial protection of marine environmental resources, it is necessary to reform the current MEPIL system and the supporting mechanisms to overcome institutional challenges. Based on judicial adjudication documents, this study examines the operation and institutional challenges of MEPIL and systematically proposes suggestions for institutional reform. Future research may further explore the implementation efficiency of marine environmental public interest litigation, cross-regional cooperation in marine governance, and the challenges of maritime judicial specialization to improve the MEPIL system.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

SX: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WL: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Social Science Fund of Jiangsu Province "Research on the Practical Dilemmas and Institutional Improvements in China's Marine Environment Civil Public Interest Litigation".

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Cao X. and Chang Y. (2023). Developing the legal basis for non-state actors in China’s ocean governance. Mar. Policy 155, 105727. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105727

Chang Y. C., Wang C., Khan M. I., and Wang N. (2020). Legal practices and challenges in addressing climate change and its impact on the oceans—A Chinese perspective. Mar. Policy 111, 103355. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.11.018

Chen H. and Bai X. (2018). Identification of qualified plaintiff in marine environmental civil public interest litigation: Dilemma and solution path. J. South China Normal Univ. Soci. Sci. Edit. 2, 162–169.

Chu J. (2023). Protecting the habitats of endangered species through environmental public interest litigation in China: lessons learned from peafowl versus the dam. J. Environ. Law 35, 455–466. doi: 10.1093/jel/eqad031

Chu B. and Zhao Y. (2023). On the institutional linkage of environmental public interest Litigation under Sea and Land cross-pollution. J. Dalian Marit. Univ 2, 1–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-7031.2023.02.002

Gao R., Peng L., Wen Q., Peng X., and Chen X. (2019). The ecological restoration aimed marine ecological compensation mode. Ocean Dev. Manage. 36 , 53–56. doi: 10.20016/j.cnki.hykfygl.2019.01.010

Han L. and Yan Q. (2024). The research on the improvement of China′s marine environmental public interest litigation jurisdiction. J. Ocean Univ. China Soci. Sci. Edit 6, 37–45. doi: 10.16497/j.cnki.1672-335X.202406005

Khan M. I. and Chang Y. (2018). Environmental challenges and current practices in China—A thorough analysis. Sustain. 10, 2547. doi: 10.3390/su10072547

Khan A. and Ullah M. (2024). The Pakistan-China FTA: Legal challenges and solutions for marine environmental protection. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1478669. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1478669

Li J. and Li N. (2015). Preliminary study on establishment of ecological compensation system for land reclamation. Mar. Dev. Manag 32 , 97–102.

Li P. and Shao C. (2024). Research on the synergy of marine and land environmental civil public interest litigation from the perspective of land and sea coordination. China Environ. Manag 2, 129–135. doi: 10.16868/j.cnki.1674-6252.2024.02.129

Li X. and Song Z. (2024). A critical examination of environmental public interest litigation in China-reflection on China’s environmental authoritarianism. Humanit. Soc Sci. Commun. 11, 644. doi: 10.1057/s41599-024-03047-9

Li Z. and Wu M. (2024). The Chinese approach to judicial protection of ecological environment: practice and challenges of procuratorial environmental public interest litigation. J. Capital Normal Univ Soci. Sci. Edit. S1, 32–46.

Liao B. (2020). Research on compensation for Marine environmental damage from the perspective of ecological civilization. J. Polit Sci. Law 37, 57–66. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-3745.2020.06.008

Liu Y. (2021). The Myth and theoretical Reconstruction of the right of Action in Procuratorial public interest Litigation. Contemp. Law 1, 117–127. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-4781.2021.01.011

Liu J. and Zhang J. (2023). A review of the hierarchy of prosecution subjects in civil public interest litigation. People’s Procu. 21, 81–85. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-4043.2023.21.030

Ma H. (2023). China’s plan for procuratorial public interest litigation legislation. Adm. Reform 10, 25–36. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7453.2023.10.003

Mao W. (2022). Industrial management and “Combination of comprehensiveness and decentralization”: on China’s marine management and law enforcement system. J. Zhejiang Ocean Univ. Hum. Sci. 39, 16–22. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8318.2022.04.003

Mi M. and Wang M. (2023). Analysis on the subject qualification of plaintiff of environmental protection Organization in Marine environmental civil public interest litigation. J. Shandong Univ. Sci. Technol. Soci. Sci. Edit. 25, 45–53. doi: 10.16452/j.cnki.sdkjsk.2023.01.001

Moynihan R. and Magsig B. O. (2020). The role of international regimes and courts in clarifying prevention of harm in freshwater and marine environmental protection. Int’l. Environ. Agreem. 20, 649–666. doi: 10.1007/s10784-020-09508-1

Qi G. (2018). Public interest litigation” in China: panacea or placebo for environmental protection? China Int’l J. 16, 47–75. doi: 10.1353/chn.2018.0038

Research Group of Panyu Procuratorate (2011). Research on the system of procuratorates filing environmental public interest litigation. Law Rev. Sun Yat-sen Univ. 1, 1–13.

Shao H. (2020). Research on litigation jurisdiction in maritime criminal cases. Chin. Prosec. 24, 3–8.

Shi J. (2020). Analysis and Suggestions on development and management of marine sand resources in China. China Land Resour. Econ. 33, 80–83. doi: 10.19676/j.cnki.1672-6995.000500

Shi W. and Hou S. (2023). Review of the current situation, reflection and improvement path of civil public interest litigation attached to ecological environmental crimes: taking 595 environmental crime judgments as samples. Legal Res. 1, 25–34. doi: 10.26914/c.cnkihy.2023.034969

Sun Y. and Zhang J. (2023). The theoretical basis and legal framework of special legislation for procuratorial public interest litigation. J. Natl. Acad. Prosec. 3, 73–88. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-9428.2023.03.005

Supreme People’s Procuratorate of China (2021). Guiding cases of the supreme people’s procuratorate no. 111. Beijing SPP, 2021.

Wang Y. (2024). Judiciary-led public interest litigation in comparative perspective: China model and its global implications. Jurist 3), 1–15. doi: 10.16094/j.cnki.1005-0221.2024.03.004

Wang X., Gu B., Tian P., and Yang F.. (2024). Logic, difficulties and path breakthrough of marine governance modernization. China Land Resour. Econ. 37, 49–54.

Wang Y. and Zang T. (2025). The practice pilots and countermeasures of marine environmental public interest litigation in the context of the “three-in-one” reform of maritime trials. Hebei Law Sci. 43, 183–200. doi: 10.16494/j.cnki.1002-3933.2025.02.010

Wu J. (2015). Procedural structure of environmental civil public interest litigation. J. East China Univ. Polit. Sci. Law 18, 40–51. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-4622.2015.06.005

Wu W. (2019). The plaintiff qualification of environmental protection organizations to bring Marine environmental civil public interest litigation: a practical review and legal evidence. J. Nanjing Univ. Technol. Soci. Sci. Edit. 22, 36–48 + 109-110. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-7287.2023.06.005

Wu D. (2025). Practice dilemma and improvement path of mandatory liability insurance for environmental pollution. China Resour. Compr. Utili. 1), 162–164. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-9500.2025.01.047

Yang H. (2021). The subject of plaintiff in Marine environmental civil public interest litigation. Legal Bus. Stud. 38, 120–133. doi: 10.16390/j.cnki.issn1672-0393.2021.03.010

Yang L. (2023). China’s MEPIL: current situation, challenges, and improvement approach–analysis based on 339 cases. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1302190. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1302190

Yin L. and Xu H. (2021). Research progress and review of Marine ecological damage compensation in China. Mar. Econ. 11, 1–10. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-1647.2021.04.001

Yu M. (2021). Research on the path and procedure of procuratorial public interest litigation in Marine environmental protection. Chin. Marit. Law Res. 32, 33–40. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-7659.2021.02.005

Zhai T. (2024). An empirical study of marine environmental civil public-interest litigation in China: Based on 216 cases from 2015 through 2022. Ocean Coast. Manage. 253, 107164. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2024.107164

Zheng J. and Hu Y. (2024). Research on the difficulties and countermeasures in handling administrative public interest litigation cases in the water-related field. Rule Law Cult. 2, 51–57.

Zhu M. (2022). Study on special jurisdiction of Maritime criminal cases. China Sto. Transp. 2, 161–162. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-0434.2022.02.090

Keywords: marine environment, public interest litigation, judicial protection, marine governance, institutional reform

Citation: Xu S and Lu W (2025) Institutional challenges and reform approaches in China’s marine environment public interest litigation. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1578824. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1578824

Received: 18 February 2025; Accepted: 25 August 2025;

Published: 05 September 2025.

Edited by:

Natasa Maria Vaidianu, Ovidius University, RomaniaReviewed by:

Mehran Idris Khan, University of International Business and Economics, ChinaM Jahanzeb Butt, Bahria University, Pakistan

Copyright © 2025 Xu and Lu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shengqing Xu, c2hlbmdxaW5neHVzZEAxMjYuY29t; Wenlei Lu, bHZ3bGRvdUAxMjYuY29t

Shengqing Xu

Shengqing Xu Wenlei Lu3*

Wenlei Lu3*