Abstract

This work evaluated the effects of dietary supplementation with the seaweed polysaccharide (PS) extracted from red seaweed, Pterocladia capillacea, on the growth, feed efficiency, whole-body composition, immunological response, antioxidant activity, digestive enzyme activities, and gene expression of the whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Four isonitrogenous and isoenergetic diets with different SP levels were formulated. The basal experimental diet (control diet) had no seaweed polysaccharide added (PS0). Diets 2–4 (PS1, PS2, and PS3) were formulated to contain PS at levels of 1, 2, and 3 g/kg diet, respectively. Six hundred postlarvae (PLs15; with an initial body weight of 1.62 ± 0.12 g/PL) of the whiteleg shrimp L. vannamei were randomly selected and distributed into triplicate hapas per treatment. For the duration of the 60-day trial, the PLs were fed their corresponding diets three times a day at 10% of their body weight. Compared with those in the control diet and PS3, the shrimp reared in groups PS1 or PS2 showed significant (p< 0.05) improvements in the specific growth rate, survival rate, length gain rate, and weight gain rate. The individuals in the PS2 group showed the greatest significant (p< 0.05) values of the feed conversion ratio, feed efficiency ratio, and protein efficiency ratio. In addition, the shrimps in the PS2 group showed the highest significant values (p< 0.05) of lysozyme, amylase, lipase, and SOD, and the highest significant value of MDA, whereas the shrimp in the PS3 group showed the highest significant values (p< 0.05) of catalase. The expression levels of investigated growth-related genes (GH, IGF-1, and IGF-II) and immunity-related genes (Proph, SOD, and Lys) in the PS2 group were significantly (p< 0.05) increased. In conclusion, the supplementation rate of 2 g/kg PS significantly improved the growth, nutrient utilization efficiency, nonspecific immunity, antioxidant and digestive enzyme activities, and improved the immunity- and growth-related gene expression of L. vannamei shrimp. However, future works are recommended to understand the mechanism by which PS enhances physiological status and modulate genes expression in whiteleg shrimp.

1 Introduction

The aqua-diet industry has recently grown worldwide, taking its place as the most deeply important shrimp aquaculture sector (Gillett, 2008; Ahmed et al., 2019). The amount of shrimp consumed has increased globally over the past ten years, leading nutritionists to recommend the use of many agriculturally derived components in shrimp aquadiets (Ashour et al., 2024a). More than 70% of all shrimp cultivated globally are the Pacific whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei (Mansour et al., 2022b; Ashour et al., 2024b). Several challenges, such as low survival rates, poor water quality, and a lack of food supply, need to be addressed to achieve shrimp industry sustainability (Mansour et al., 2022b; N’Souvi et al., 2024; Widiasa et al., 2023; Suzuki and Nam, 2023). Additionally, serious issues, including the harmful impact of climate change, the increase in water pollution, the availability of aqua-diet ingredients (Abo-Taleb et al., 2021), low biological productivity, limiting shrimp aqua-diet industry development, shrimp aquaculture, and aquatic ecosystem impacts (Abisha et al., 2022; Metwally et al., 2020; Magouz et al., 2021). Several approaches have been employed to address international growth in the shrimp aquadiet industry, leading to the expansion of the shrimp diet industry (El-Sayed, 2021; Kesselring et al., 2021; Ashour et al., 2024a). Aqua-diet feed additives constitute one of the most deeply and extensively utilized approaches. It has become crucial for marine shrimp species as a growth promoter, immune system enhancer, and alternative disease resistance mechanism (Ceseña et al., 2021).

Marine seaweeds and/or their derivatives remain extensively employed in many major industries, including aqua-feed additives, plant growth enhancers (Ashour et al., 2023), antimicrobial activities (Osman et al., 2010, 2020), phytoremediation (Essa et al., 2018; Mansour et al., 2022a; Abou-Shanab et al., 2014), bioenergy (Elshobary et al., 2021), pharmaceuticals (Shao et al., 2019; Ashour and Omran, 2022), cosmetics (Mourelle et al., 2017; Zhuang et al., 2021), and human food supplements (Vieira et al., 2020; Fais et al., 2022). The Egyptian coasts (the Mediterranean and the Red Sea) have an important variety of seaweed. The red seaweed Pterocladia capillacea is well known for its high content of bioactive compounds.

Among different seaweed groups, red seaweeds are well known for having high polysaccharide contents and other bioactive compounds, such as flavonoids, phenolics, alkenes, hydrocarbons, vitamins, fatty acid methyl esters, and alkaloid compounds (Sanjeewa et al., 2018). These biological materials can shield aquatic organisms from a variety of detrimental effects, such as anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant, immune enhancer, and growth stimulator activities (Khotimchenko et al., 2020; Yazici et al., 2024). Red seaweeds have been successively used as feed additives for several aquatic animals (Pereira et al., 2020; Yazici et al., 2024). Zhang et al. (2023) investigated the impacts of nine different seaweeds—five green seaweeds (U. lactuca, C. racemosa, C. lentillifera, C. sertularioides, and C. linum), three red seaweed species (Acanthophora spicifera, G. bailiniae, and B. gelatinae), and one brown seaweed species (S. ilicifolium) as feed additives on the growth performance, immune response, antioxidant capacity, and antioxidation-related genes of white shrimp, L. vannamei juveniles for 28 days. Among the seaweeds used in this study, the red seaweed species A. spicifera had the greatest effect on immune response, antioxidant capacity, and antioxidation-related genes in L. vannamei (Zhang et al., 2023).

The use of polysaccharide (PS) from red seaweed, P. capillacea, has not been extensively investigated in shrimp L. vannamei diets, and little information is available regarding the performance of L. vannamei shrimp (Øverland et al., 2019; Vidhya Hindu et al., 2019). Therefore, this study aimed to examine the effects of red seaweed polysaccharide dietary supplementation on the growth, nutrient efficiency, immunity, digestive enzyme, antioxidant activities, growth, and gene expression of related growth and immunity genes in the whiteleg shrimp L. vannamei postlarvae.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Seaweed polysaccharides

Pterocladia capillacea (Rhodophyceae) samples were collected from the Alexandria Coast, Abu-Qir Bay, Egypt. The collected samples were cleaned, washed, air-dried, powdered, and stored in a plastic bag at room temperature in the dark until use (Abbas et al., 2023). The extraction procedure of red seaweed PS was produced following the protocol described previously by Abdelrhman et al. (2022). Briefly, the polysaccharides were extracted from dried red seaweed with distilled water at 100 °C for 1 hr to ensure justification of the extraction process. Then the crude polysaccharide was precipitated by adding three-fold crude cold ethanol and filtrated. After filtration, the crude polysaccharide precipitate was collected and washed several times with cold ethanol to remove residual impurities. The purified polysaccharide was then dried by lyophilization to remove any remaining ethanol and moisture. The final dried polysaccharide product was weighed and stored at -20°C until use.

2.2 Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei

The shrimp postlarvae (PLs15) were transferred from Barakat Ghalioun Hatchery in Kafr El Sheikh Governorate, Egypt, to the Fish Nutrition Laboratory, Baltim Research Station, Alexandria Branch, NIOF, Egypt. The PLs were stored for 15 days in concrete ponds (1 m × 5 m × 5 m) to adapt to the experimental culture conditions (dissolved oxygen of<5 mg L-1, temperature of 27 ± 1°C, salinity of 26.5 ± 1.0 ppt). Approximately 10% of the total water in the culture tanks was replaced daily with new clean water. During the acclimatization period, the PLs were fed, four times a day with a control basal diet containing 45% protein until full saturation. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Egypt.

2.3 Shrimp experimental diets

Four isocaloric (gross energy of 19.9 MJ/kg) and isonitrogenous (crude protein of 45.47%) diets were formulated in this feeding experiment. The control basal diet was not supplemented with PS extracted (PS0). Groups 2 to 4 were supplemented with PS at concentrations of 1, 2, and 3 g of PS/kg diet (PS1, PS2, and PS3, respectively). The selection of PS supplementation levels to the diets was performed as previously reported (Abdelrhman et al., 2022). The ingredients and diet biochemical compositions are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Ingredient (%, dry matter basis)* | Experimental groups (PS %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS0 | PS1 | PS2 | PS3 | |

| Fish meal | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Wheat gluten | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Defatted soybean meal | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| Squid liver powder | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Wheat flour | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Fish oil | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Lecithin | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Binder | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Cholesterol | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Choline chloride (60%) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Monocalcium phosphate (MCP) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Premix | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Ascorbic Acid | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Gelatin | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Lysine | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Methionine | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Total (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Polysaccharides (g/kg diet) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Chemical composition (%) | ||||

| Crude Protein | 45.47 | 45.47 | 45.47 | 45.47 |

| Crude lipid | 7.86 | 7.85 | 7.88 | 7.89 |

| Carbohydrate | 33.88 | 33.91 | 33.93 | 33.98 |

| Crude Fiber | 3.59 | 3.68 | 3.63 | 3.61 |

| Ash | 9.27 | 9.11 | 9.19 | 9.11 |

| Gross energy (MJ/kg) | 19.91 | 19.95 | 19.94 | 19.99 |

The ingredients and biochemical analysis of the experimental groups.

*PS0, PS1, PS2, and PS3: 0, 1, 2, and 3 g of red seaweed polysaccharide dietary supplement, respectively.

2.4 Experimental technique

After two weeks of acclimation, 600 PLs (initial body weight of 1.62 ± 0.12 g/PL and initial body length of 3.03 ± 0.11 cm/PL) were divided into four groups (diets), with 150 PLs per group (in triplicates). Each group was stored in a concrete pond (4 × 2 × 1 m), which was divided into three net hapas (0.7 × 0.7 × 1 m), 50 PLs per hapa. For 60 days, the distributed PLs were reared under optimum water quality conditions of salinity, pH, NH3, salinity, temperature, NO2, and NO3. Salinity, temperature, and pH were measured daily at midday. NH3, NO2, and NO3 were measured weakly. The water quality parameters were measured following the guidelines of APHA (2005). For all the groups, approximately 10% of the total water volume was replaced daily with new clean water.

2.5 Growth and feed efficiency indices

The survival rate (SR, %) was calculated by determining the initial and final number of PLs. The growth performance and feed efficiency parameters were calculated via the following equations:

2.6 Biochemical analysis

Fifteen individual shrimp were randomly selected from each group (five samples per replicate) for biochemical analysis of the whole shrimp at the end of the experiment. Briefly, the samples were euthanized, mixed, dried, powdered, and finally stored at a low temperature (– 20°C) until further analysis. The dry matter, crude protein, crude lipid, and ash contents were determined following the guidelines of AOAC (2003).

2.7 Immunological responses, digestive enzyme, and antioxidant activities

At the end of the experiment and after 24 hours of fasting, fifteen shrimp were randomly chosen from each group (five samples per replicate) to determine the immunological and antioxidant activity indices of lysozyme (µg/mL), catalase (IU/g), malondialdehyde (MDA, nmol/g), and serum superoxide dismutase (SOD, IU/g). Moreover, the activities of digestive enzymes (amylase and lipase) were determined in digestive gland homogenate using colorimetric assays following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, randomly selected samples were euthanized by cryoanesthesia (Becker et al., 2024), and muscle tissue and organs were dissected, weighed, and homogenized in a phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.4). Then, the tissues were centrifuged (3500 rpm/20 min), and the supernatants were carefully collected and stored at -20°C.

2.7.1 Lysozyme activities

The lysozyme activity was determined using ELISA kits (Catalog numbers: SL0050FI; SunLong Biotech Co., Ltd., China). The lysozyme-containing sample was incubated with Micrococcus lysodeikticus cells as the substrate. As directed by the manufacturer (Harshbarger et al., 1992), the reaction was observed by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 450 nm to determine the rate of substrate conversion.

2.7.2 Antioxidant activities

The antioxidant activities of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and malondialdehyde (MDA) were determined using the colorimetric method following the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific kits for CAT, SOD, and MDA were obtained from the Biodiagnostic Company, Egypt (Catalog numbers: CA2517, SD2521, and MD2529, respectively). The amusement wavelengths for SOD, MDA, and CAT were 560 nm (Nishikimi et al., 1972), 534 nm (Ohkawa et al., 1979), and 510 nm (Aebi, 1984), respectively.

2.7.3 Digestive enzyme activities

The activities of the digestive enzymes were determined in digestive gland homogenate using colorimetric assays following the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific kits for amylase and lipase were produced by the Biodiagnostic Company, Egypt (Catalog numbers: AY1050 and 281001, respectively). The measurement wavelengths for amylase and lipase were 660 nm (Caraway, 1959) and 580 nm (Moss et al., 1999), respectively.

2.8 Quantitative real-time PCR

Three shrimp were selected from the each group at the termination of the experiment. For total RNA isolation, small pieces of muscle tissue were cut and ground in Easy-RED TRIzol (Easy-RED, INTRON, Korea) as instructed by the manufacturer. The purity and concentration of the RNA samples were checked via a nanodrop (Implen, Nanophotometer, NP80 touch, Germany). cDNAs were then synthesized from the isolated RNA as templates via a commercial kit (ABT 2X RT Mix, cDNA Synthesis Kit, Applied Biotechnology). To evaluate the health status of L. vannamei fed different doses of red seaweed polysaccharides, the expression of growth- and immunity-related genes (GH, IGF-I, IGF-II, proPO, SOD, and Lys) was assessed. cDNAs were amplified through thermal cycling in RotorGene Q in 20 μl reactions containing 10 μl of ABT 2x qPCR Mix kit (SYBR Green/low ROX), 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM), 4 μl (50 ng) of cDNA, and 5 μl of RNAse-free water. The thermal profile included initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles, each of which included denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, annealing at 60–62°C for 10 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. The temperature was then increased in increments of 0.5°C from 60°C to 95°C to produce a melting curve, which was used to assess the target gene products. β-actin (Wang et al., 2008) was used as the housekeeping gene during this experiment. The primer names, sequences, and product sizes are presented in Table 2. The target genes’ Ct values were normalized to those of β-actin via the 2-ΔΔCt method (Rao et al., 2013).

Table 2

| Primer | Sequences (5′→3′) | Amplificon size (bp) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

β-actin

AF300705 |

F: GCCCATCTACGAGGGATA R: GGTGGTCGTGAAGGTGTAA |

121 | (Wang et al., 2008) |

|

proPO

AY723296 |

F: CGGTGACAAAGTTCCTCTTC R: GCAGGTCGCCGTAGTAAG |

122 | (Wang et al., 2008) |

|

SOD

DQ005531 |

F: AATTGGAGTGAAAGGCTCTGGCT R: ACGGAGGTTCTTGTACTGAAGGT |

153 | (Wang et al., 2008) |

|

Lys

AY170126 |

F: GGACTACGGCATCTTCCAGA R: ATCGGACATCAGATCGGAAC |

97 | (Wang et al., 2008) |

|

GH

XM027360152 |

F: AATTTGCGCTTGCACTACGG R: ATCCGGTTGAGGTGTAGCTG |

100 | Designed by NCBI tool |

|

IGF-I

KP420228 |

F: GTGGGCAGGGACCAAATC R: TCAGTTACCACCAGCGATT |

123 | Designed by NCBI tool |

| IGF-II XM02739466 | F: CTCTGTACAGTCAGCCCAGC R: CACACCCAGTCAGTCCCAAG |

220 | Designed by NCBI tool |

Primers, accession numbers, sequences, and product sizes (bp) were used for the qPCR study.

β-actin, beta-actin; proPO, Prophenoloxidase; SOD, Superoxide dismutase; Lys, Lysozyme; GH, Growth hormone; IGF-I, Insulin-growth factor 1, and IGF-II, Insulin-growth factor II.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Before performing the statistical analysis, Levene’s test was used to confirm the homogeneity assumption and normality, and arc-sin was used to convert the percentage results (Zar, 1984). The results are presented as the means ± standard deviations. With the use of SPSS Statistics Software, one-way ANOVA and the Duncan (1955) test (p< 0.05) were used for statistical analysis. Figures were created via the statistical program Graph Pad software (Swift, 1997).

3 Results

3.1 Water quality, growth, and feed utilization efficiency

The water quality indices of the current trial revealed that the temperature (26.5 ± 1.5°C), salinity (27 ± 2 ppt), pH (7.7 ± 0.2), NH3 (0.08 ± 0.03 mg/L), NO3 (0.17 ± 0.03 mg/L), and NO2 (0.09 ± 0.01 mg/L) were within the acceptable ranges for shrimp production (Venkateswarlu et al., 2019)_ENREF_5. The present study revealed that shrimp fed either PS1 or PS2 had significantly greater FW, WG, DWG, FL, LG, and SGR. In addition, shrimp fed PS2 presented the most significant values of FCR, FER, FI, PI, and SR. While PER value in PS0, PS1, and PS2 was significantly higher than PS3, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

| Indices | PS0 | PS1 | PS2 | PS3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IW (g/pL) | 1.62 ± 0.12 | 1.62 ± 0.12 | 1.62 ± 0.12 | 1.62 ± 0.12 |

| FW (g/PL) | 10.05 ± 0.35b | 10.69 ± 0.115a | 11.09 ± 0.288a | 9.32 ± 0.10c |

| WG (g) | 8.43 ± 0.450b | 9.07 ± 0.115a | 9.47 ± 0.288a | 7.70 ± 0.100c |

| DWG (g) | 0.14 ± 0.005b | 0.15 ± 0.005b | 0.16 ± 0.001a | 0.13 ± 0.005c |

| IL (cm/PL) | 3.03 ± 0.11 | 3.03 ± 0.11 | 3.03 ± 0.11 | 3.03 ± 0.11 |

| FL (cm/PL) | 11.27 ± 0.208b | 11.67 ± 0.152a | 11.60 ± 0.100a | 11.00 ± 0.101b |

| LG (cm) | 8.23 ± 0.321b | 8.63 ± 0.152a | 8.60 ± 0.100a | 7.93 ± 0.057b |

| SGR (%/day) | 1.14 ± 0.052ab | 1.18 ± 0.060a | 1.20 ± 0.045a | 1.08 ± 0.050b |

| SR (%) | 80.00 ± 2.01c | 85.33 ± 3.05b | 92.00 ± 2.02a | 76.00 ± 2.10c |

| FI (g) | 16.83 ± 0.51bc | 17.53 ± 0.25ab | 18.03 ± 0.56a | 16.43 ± 0.25c |

| PI (g) | 6.06 ± 0.18bc | 6.31 ± 0.09ab | 6.49 ± 0.20a | 5.91 ± 0.09c |

| FCR | 1.68 ± 0.08ab | 1.64 ± 0.03ab | 1.63 ± 0.06b | 1.76 ± 0.02a |

| FER | 0.59 ± 0.03ab | 0.61 ± 0.01ab | 0.61 ± 0.02a | 0.57 ± 0.01b |

| PER | 1.39 ± 0.10a | 1.44 ± 0.01a | 1.46 ± 0.05a | 1.30 ± 0.03b |

Growth performance and nutrient utilization efficiency of Litopenaeus vannamei shrimp fed diets supplemented with red seaweed polysaccharides.

PS0, PS1, PS2, and PS3: 0, 1, 2, and 3 g of red seaweed polysaccharide dietary supplement, respectively. IW, Initial Weight (g/pL); FW, Final Weight (g/pL); WG, Weight Gain (g); DWG, Daily Weight Gain (g); IL, Initial Length (cm/PL); FL, Final Length (cm/PL); LG, Length Gain (cm); SGR, Specific Growth Rate (%/day); SR, Survival Rate (%); FI, Feed Intake (g); PI, Protein Intake (g); FCR, Feed Conversion Ratio; FER, Feed Efficiency Ratio; PER, Protein Efficiency Ratio. The data (n = 5) are the means ± SDs. Letters in the same column are significantly different (p< 0.05).

3.2 Body biochemical composition

There were significant differences reported among the PS groups (PS1, PS2, and PS3) and the control group (PS0). The shrimp in the PS2 treatment presented the highest significant dry matter and lipid contents, whereas those in the PS3 treatment presented the highest significant protein and ash contents (Table 4).

Table 4

| Diets | Composition analysis (% of dry weight) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | Dry matter | Protein | Fat | Ash | |

| PS0 | 20.19 ± 0.05b | 79.81 ± 0.05c | 56.62 ± 0.27c | 7.06 ± 0.17b | 15.33 ± 0.31ab |

| PS1 | 21.42 ± 0.03a | 78.58 ± 0.03d | 56.17 ± 0.26d | 7.19 ± 0.24b | 13.75 ± 0.55c |

| PS2 | 17.97 ± 0.02d | 82.03 ± 0.02a | 58.15 ± 0.17b | 8.09 ± 0.06a | 14.82 ± 0.17b |

| PS3 | 19.88 ± 0.05c | 80.13 ± 0.05b | 60.28 ± 0.18a | 6.11 ± 0.21c | 15.92 ± 0.11a |

Biochemical composition analysis (%) of Litopenaeus vannamei shrimp fed diets supplemented with red seaweed polysaccharides.

PS0, PS1, PS2, and PS3: 0, 1, 2, and 3 g of polysaccharide dietary supplement, respectively. The data (n = 5) are the means ± SDs. Letters in the same column are significantly different (p< 0.05).

3.3 Immunological responses, antioxidant

Table 5 shows the immunological responses, digestive enzymes, and antioxidant activities of the L. vannamei shrimp. The results revealed that shrimp fed the PS2 diet presented the highest level of lysozyme. The highest MDA and CAT values were achieved by shrimp fed PS0 and PS3, respectively. However, the shrimp fed the PS3 diet presented the best value of CAT, and the shrimp fed the PS2 diet presented the best value of SOD.

Table 5

| Parameters | PS0 | PS1 | PS2 | PS3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme (µg/mL) | 3.70 ± 0.45b | 3.81 ± 0.16b | 4.64 ± 0.65a | 4.30 ± 0.10ab |

| MDA (nmol/g) | 10.74 ± 0.12a | 9.09 ± 0.03d | 10.09 ± 0.03b | 9.89 ± 0.02c |

| CAT (IU/g) | 8.26 ± 0.41b | 8.56 ± 0.41b | 8.48 ± 0.51b | 9.57 ± 0.45a |

| SOD (IU/g) | 9.87 ± 0.16b | 10.15 ± 0.06b | 11.04 ± 0.25a | 10.30 ± 0.12b |

Immunological responses and antioxidant of Litopenaeus vannamei shrimp fed diets supplemented with red seaweed polysaccharides.

PS0, PS1, PS2, and PS3: diets supplemented with 0, 1, 2, or 3 g of polysaccharides, respectively. The data (n = 5) are the means ± SDs. Letters in the same column are significantly different (p< 0.05).

3.4 Digestive enzyme activities

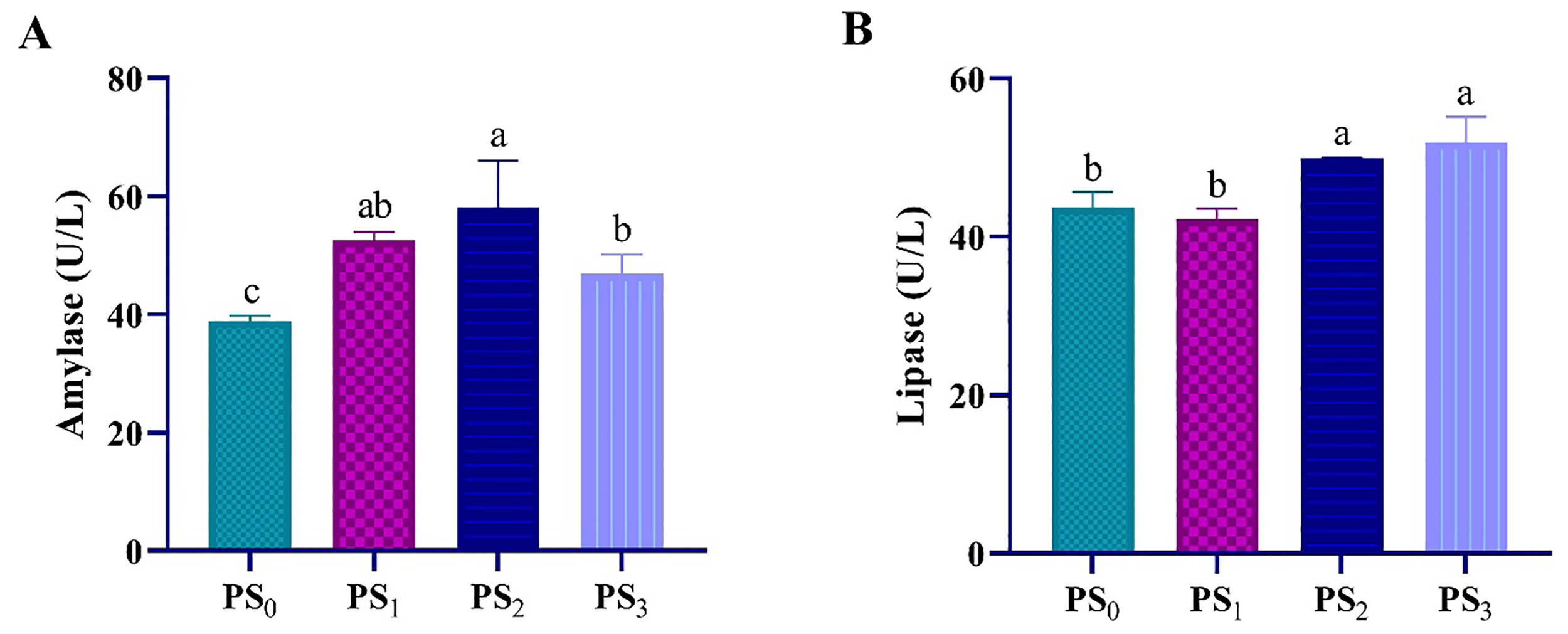

The effect of PS supplementation on digestive enzyme activities was presented in Figure 1. Shrimp fed either PS2 or PS3 presented the highest lipase activity. However, the highest significant amylase activity was reported PS2 treatment.

Figure 1

Digestive enzyme activities (A amylase and B lipase) of L. vannamei shrimp fed diets containing different levels of polysaccharides at P< 0.05.

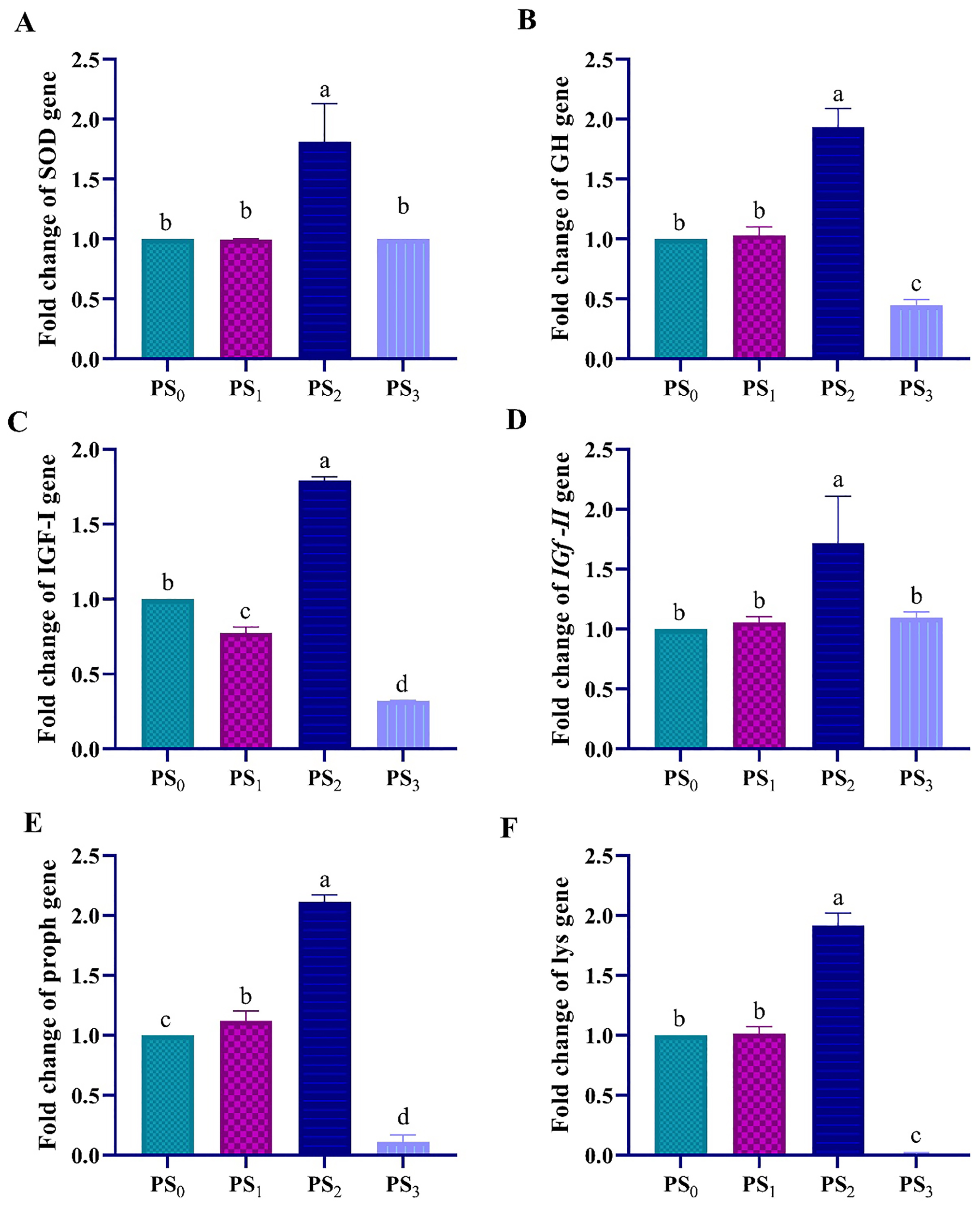

3.5 Gene expression

The results showed that SOD expression was upregulated in group fed diet supplemented with PS2 and did not change in other groups (Figure 2A). The growth- and immune-related gene expression was upregulated to its maximum in PS2. However, growth-related gene expression was down regulated in response to the seaweed PS in PS0, PS3, and PS1 (Figures 2B–D). On the other hand, the expression of immunity-related genes (Proph, and Lys) peaked in L. vannamei muscles when the concentration of PS was increased to 2 g kg-1 diet (PS2) (Figures 2E, F).

Figure 2

Gene expression levels of growth (A)GH, (B)IGF-1, and (C)IGF-II, and immunity; (D)Proph, (E)SOD, and (F)Lys, related genes in L. vannamei muscle shrimp fed diets containing different levels of polysaccharides at P< 0.05.

4 Discussion

Seaweeds have been documented to contain many bioactive compounds that improve growth and immune systems (Abbas et al., 2023). The results of the present study revealed that the performance, feed efficiency, and survival rate of shrimp increased significantly with increasing incorporation levels of polysaccharides in the diet compared with those of the control, with either the PS1 or the PS2 being superior.

The results of the present study are consistent with those by Abbas et al. (2023), who reported that diets supplemented with PS extracted from S. dentifolium, a brown seaweed, significantly increased the growth, feed efficiency, microbial diversity, abundance, and gene expression of related immune-related genes in L. vannamei. In their study, the most significant values of the studied parameters were achieved at the inclusion level of the 3 g/kg diet. However, the difference between Abbas et al. (2023) (3 g/kg diet) and our finding (2 g/kg diet) may be due to the type of seaweed species, the brown seaweed S. dentifolium in the study by Abbas et al. (2023) and the red seaweed P. capillacea in the present study. The nutritional value of red seaweed PS is greater than that of brown seaweed PS (Souza et al., 2012; Tanna and Mishra, 2019). The results of the present study are inconsistent with those by Peixoto et al. (2016), and Queiroz et al. (2014) who reported that the inclusion of brown seaweed does not affect the performance of various fish species, such as Senegalese sole, Gilthead seabream, and European seabass. The inconsistencies between these trials may be related to various factors, such as the type of seaweed species, inclusion level, or seaweed inclusion form (dry weight powder, extract, or PS form), as well as the aquatic animal species, size, age, and water quality.

The current findings may be related to different mechanisms: (i) the phytochemical compounds such as polyphenols and other functional groups present in the seaweed PS (Gómez-Ordóñez et al., 2014); (ii) the antioxidant properties of PS have positive impacts on the growth performance, nutrient efficiency, immune responses, and gene expression of L. vannamei (Abbas et al., 2023), rainbow trout (Sotoudeh and Mardani, 2018), Nile tilapia (Villamil et al., 2019), rabbit fish (Bakky et al., 2023), and hybrid red tilapia (Abdelrhman et al., 2022); (iii) the beneficial effects of polysaccharides, which slow down the rate while the feed passes through the digestive tract which increase nutrient absorption and bioavailability (Sotoudeh and Mardani, 2018). In terms of chemical body composition, shrimp-fed diets supplemented with polysaccharides, specifically, PS2, presented the highest values of dry matter and lipids, whereas those in PS3 presented the highest significant protein and ash contents. These results are in line with the findings reported by Abbas et al. (2023), who reported significant differences in the whole-body composition of L. vannamei when fed different levels of PS extracted from the brown seaweed S. dentifolium (SWP1, SWP2, and SWP3: 1, 2, and 3 g/kg diet, respectively), compared with the control diet SWP0 (0 g/kg diet).

Immune parameters are measured as predictive indicators for the investigation of shrimp health (Jerez-Cepa and Ruiz-Jarabo, 2021). The results of the present study are in line with the results reported by (Del Rocío Quezada-Rodríguez and Fajer-Ávila, 2017), who reported that ulvan has a key function in increasing the immune response of O. niloticus. Furthermore, our findings are similar to those reported by Akbary and Aminikhoei (2018) and Nirmal et al. (2024), who concluded that the inclusion of PS has a significant effect on enhancing the immune parameters of aquatic animals. These differences may be due to the greater potential of bioactive compounds and PS in red seaweed than in other seaweed types (Ashour et al., 2024a, b).

The enzymes of the digestive system play essential roles in both improving food absorption and digestion in the gastrointestinal system (Klahan et al., 2023). Our findings revealed that the incorporation of PS from P. capillacea had a significant effect on the activities of the digestive enzymes of L. vannamei. In our study, shrimp in the PS2 group (2 g/kg) presented the highest amylase and lipase activities. These findings are consistent with those published previously by (Liang et al., 2021). These results may be explained by the following functions of the biological activities of PS, including PS increases the activities of digestive enzymes (Ashour et al., 2024b), and the pH of the gastrointestinal tract is adjusted to improve the activities of digestive enzymes (Liang et al., 2021). Furthermore, the inclusion of polysaccharides in shrimp diets increased growth- and immune-related gene expression, particularly in the 2 g kg-1 diet (PS2). However, both the growth and immunity-related gene expression are down regulated in the 3 g/kg diet (PS3), which recommended the inclusion of a 2 g kg-1 diet as the maximum dose of polysaccharides in shrimp diets. These results are consistent with those of Zhu et al. (2011) who reported that L. vannamei-fed diets supplemented with PS significantly reduce inflammation, improve immune enzymes, and increase immune gene expression. Moreover, Abbas et al. (2023) reported that the L. vannamei dietary supplementation with PS positively upregulates growth-, and immune-related gene expression. Similarly, Lee et al. (2020) reported that the L. vannamei diet supplemented with brown seaweed PS significantly upregulated the immune gene expression of L. vannamei. Additionally, Liu et al. (2020) reported that the inclusion of PS extracted from Enteromorpha significantly improved the growth- and immune-related gene expression of the banana shrimp F. merguiensis.

5 Conclusion

The inclusion of polysaccharides derived from the red seaweed P. capillacea at a dose of 2 g/kg significantly improved the growth, nutrient utilization efficiency, immunological status, antioxidant balance, digestive enzyme activities, and growth- and immunity-related gene expression of the shrimp L. vannamei. The current findings highlight the importance of utilizing polysaccharides derived from red seaweed in the shrimp aquadiet industry. This could reduce reliance on antibiotics, lower feed costs via better FCR, and boost survival rates in aquaculture. The study supports sustainable practices by utilizing seaweed-derived additives to improve shrimp health and productivity. Future research should explore mechanisms behind PS-mediated gene regulation and gut microbiome interactions. Moreover, future works are recommended to understand the mechanism by which PS enhance physiological status and modulate genes expression in whiteleg shrimp.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

MA: Formal analysis, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. FA: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. AM: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation. AIAM: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation. MM: Investigation, Data curation, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology. ATM: Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Supervision. EM: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Resources, Formal analysis, Supervision. AA: Validation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (KFU251721).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abbas E. M. Al-Souti A. S. Sharawy Z. Z. El-Haroun E. Ashour M. (2023). Impact of dietary administration of seaweed polysaccharide on growth, microbial abundance, and growth and immune-related genes expression of the Pacific whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Life13, 344. doi: 10.3390/life13020344

2

Abdelrhman A. M. Ashour M. Al-Zahaby M. A. Sharawy Z. Z. Nazmi H. Zaki M. A. et al . (2022). Effect of polysaccharides derived from brown macroalgae Sargassum dentifolium on growth performance, serum biochemical, digestive histology and enzyme activity of hybrid red tilapia. Aquacult. Rep.25, 101212. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2022.101212

3

Abisha R. Krishnani K. K. Sukhdhane K. Verma A. Brahmane M. Chadha N. (2022). Sustainable development of climate-resilient aquaculture and culture-based fisheries through adaptation of abiotic stresses: a review. J. Water Climate Change. 13 (7), 2671–2689. doi: 10.2166/wcc.2022.045

4

Abo-Taleb H. A. Ashour M. Elokaby M. A. Mabrouk M. M. El-Feky M. M. M. Abdelzaher O. F. et al . (2021). Effect of a New Feed Daphnia magna (Straus 1820), as a Fish Meal Substitute on Growth, Feed Utilization, Histological Status, and Economic Revenue of Grey Mullet, Mugil cephalus (Linnaeus 1758). Sustainability13, 7093. doi: 10.3390/su13137093

5

Abou-Shanab R. A. I. El-Dalatony M. M. El-Sheekh M. M. Ji M.-K. Salama E.-S. Kabra A. N. et al . (2014). Cultivation of a new microalga, Micractinium reisseri, in municipal wastewater for nutrient removal, biomass, lipid, and fatty acid production. Biotechnol. biopro. Eng.19, 510–518. doi: 10.1007/s12257-013-0485-z

6

Aebi H. (1984). “[13] Catalase in vitro,” in Methods in enzymology (Academic Press).

7

Ahmed N. Thompson S. Glaser M. (2019). Global aquaculture productivity, environmental sustainability, and climate change adaptability. Environ. Manage.63, 159–172. doi: 10.1007/s00267-018-1117-3

8

Akbary P. Aminikhoei Z. (2018). Effect of polysaccharides extracts of algae Ulva rigida on growth, antioxidant, immune response and resistance of shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei against Photobacterium damselae. Aquacult. Res.49, 2503–2510. doi: 10.1111/are.2018.49.issue-7

9

AOAC (2003). AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (Arlington, Virginia: Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC)).

10

APHA (2005). Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater (Washington, DC, USA: American Public Health Association (APHA).

11

Ashour M. Al-Souti A. S. Hassan S. M. Ammar G. A. G. Goda A. El-Shenody R. et al . (2023). Commercial seaweed liquid extract as strawberry biostimulants and bioethanol production. Life13, 85. doi: 10.3390/life13010085

12

Ashour M. Al-Souti A. S. Mabrouk M. M. Naiel M. A. Younis E. M. Abdelwarith A. A. et al . (2024a). A commercial seaweed extract increases growth performance, immune responses, and related gene expressions in whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquacult. Rep.36, 102154. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102154

13

Ashour M. Mabrouk M. M. Mansour A. I. A. Abdelhamid A. F. Abdel-Kader M. F. Elokaby M. A. et al . (2024b). Impact of dietary administration of Arthrospira platensis free-lipid biomass on growth performance, body composition, redox status, immune responses, and some related genes of pacific whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. PloS One19, e0300748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0300748

14

Ashour M. Omran A. M. M. M. (2022). Recent advances in marine microalgae production: highlighting human health products from microalgae in view of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Fermentation8, 466. doi: 10.3390/fermentation8090466

15

Bakky M. A. H. Tran N. T. Zhang Y. Hu H. Lin H. Zhang M. et al . (2023). Effects of dietary supplementation of Gracilaria lemaneiformis-derived sulfated polysaccharides on the growth, antioxidant capacity, and innate immunity of rabbitfish (Siganus canaliculatus). Fish Shellf. Immunol.139, 108933. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2023.108933

16

Becker A. J. Braga A. Magalhães V. Medeiros L. M. Ramos P. B. Monserrat J. M. et al . (2024). Examination of the antioxidant effects of linalool and Lippia alba essential oil in the Pacific whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, subjected to eyestalk ablation. Aquaculture592, 741215. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741215

17

Caraway W. (1959). α-amylase colorimetric method. Ame. J. Clin. Pathol.32, 97–99. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/32.1_ts.97

18

Ceseña C. E. Jacinto E. C. González A. L. Villasante F. V. Castro R. M. M. Ochoa N. et al . (2021). Dietary supplementation of Debaryomyces hansenii enhanced survival, antioxidant and immune response in juvenile shrimp penaeus vannamei challenged with Vibrio Parahaemolyticus. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosys.24. doi: 10.3390/ani11051188

19

Del Rocío Quezada-Rodríguez P. Fajer-Ávila E. J. (2017). The dietary effect of ulvan from Ulva clathrata on hematological-immunological parameters and growth of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). J. Appl. Phycol.29, 423–431. doi: 10.1007/s10811-016-0903-7

20

Duncan D. B. (1955). Multiple range and multiple F tests. biometrics11, 1–42. doi: 10.2307/3001478

21

El-Sayed A. F. M. (2021). Use of biofloc technology in shrimp aquaculture: a comprehensive review, with emphasis on the last decade. Rev. Aquacult.13, 676–705. doi: 10.1111/raq.12494

22

Elshobary M. E. El, Shenody R. A. Abomohra A. E. F. (2021). Sequential biofuel production from seaweeds enhances the energy recovery: A case study for biodiesel and bioethanol production. Int. J. Energy Res.45, 6457–6467. doi: 10.1002/er.v45.4

23

Essa D. Abo-Shady A. Khairy H. Abomohra A. E.-F. Elshobary M. (2018). Potential cultivation of halophilic oleaginous microalgae on industrial wastewater. Egypt. J. Bot.58, 205–216. doi: 10.21608/ejbo.2018.809.1054

24

Fais G. Manca A. Bolognesi F. Borselli M. Concas A. Busutti M. et al . (2022). Wide range applications of spirulina: from earth to space missions. Mar. Drugs20, 299. doi: 10.3390/md20050299

25

Gillett R. (2008). Global study of shrimp fisheries. FAO Fish Tech. Pap.475, 25–29.

26

Gómez-Ordóñez E. Jiménez-Escrig A. Rupérez P. (2014). Bioactivity of sulfated polysaccharides from the edible red seaweed Mastocarpus stellatus. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre3, 29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2014.01.002

27

Harshbarger J. C. Spero P. M. Wolcott N. M. (1992). Neoplasms in wild fish from the marine ecosystem. Pathobiol. Mar. Estuar. Organ.2, 157.

28

Jerez-Cepa I. Ruiz-Jarabo I. (2021). Physiology: An important tool to assess the welfare of aquatic animals. Biology10, 61. doi: 10.3390/biology10010061

29

Kesselring J. Gruber C. Standen B. Wein S. (2021). Effect of a phytogenic feed additive on the growth performance and immunity of Pacific white leg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, fed a low fishmeal diet. J. World Aquacult. Soc.52, 303–315. doi: 10.1111/jwas.12739

30

Khotimchenko M. Tiasto V. Kalitnik A. Begun M. Khotimchenko R. Leonteva E. et al . (2020). Antitumor potential of carrageenans from marine red algae. Carbohydr. Polym.246, 116568. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116568

31

Klahan R. Deevong P. Wiboonsirikul J. Yuangsoi B. (2023). Growth Performance, feed utilisation, endogenous digestive enzymes, intestinal morphology, and antimicrobial effect of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) fed with feed supplemented with pineapple waste crude extract as a functional feed additive. Aquacult. Nutr.1160015. doi: 10.1155/2023/1160015

32

Lee S. J. In G. Han S.-T. Lee M.-H. Lee J.-W. Shin K.-S. (2020). Structural characteristics of a red ginseng acidic polysaccharide rhamnogalacturonan I with immunostimulating activity from red ginseng. J. Ginseng Res.44, 570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2019.05.002

33

Liang J. Zhang M. Wang X. Ren Y. Yue T. Wang Z. et al . (2021). Edible fungal polysaccharides, the gut microbiota, and host health. Carbohydr. polym.273, 118558. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118558

34

Liu W.-C. Zhou S.-H. Balasubramanian B. Zeng F.-Y. Sun C.-B. Pang H.-Y. (2020). Dietary seaweed (Enteromorpha) polysaccharides improves growth performance involved in regulation of immune responses, intestinal morphology and microbial community in banana shrimp Fenneropenaeus merguiensis. Fish shellf. Immunol.104, 202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.05.079

35

Magouz F. I. Essa M. A. Matter M. Mansour T. A. Alkafafy M. Ashour M. (2021). Population dynamics, fecundity and fatty acid composition of oithona nana (Cyclopoida, copepoda), fed on different diets. Anim. (Basel)11 (5), 1188. doi: 10.3390/ani11051188

36

Mansour A. T. Alprol A. E. Ashour M. Ramadan K. M. A. Alhajji A. H. M. Abualnaja K. M. (2022a). Do red seaweed nanoparticles enhance bioremediation capacity of toxic dyes from aqueous solution? Gels8, 310. doi: 10.3390/gels8050310

37

Mansour A. T. Ashry O. A. Ashour M. Alsaqufi A. S. Ramadan K. M. Sharawy Z. Z. (2022b). The optimization of dietary protein level and carbon sources on biofloc nutritive values, bacterial abundance, and growth performances of whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) juveniles. Life12, 888. doi: 10.3390/life12060888

38

Metwally A. S. El-Naggar H. A. El-Damhougy K. A. Bashar M. A. E. Ashour M. Abo-Taleb H. A. H. (2020). GC-MS analysis of bioactive components in six different crude extracts from the Soft Coral (Sinularia maxim) collected from Ras Mohamed, Aqaba Gulf, Red Sea, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish.24, 425–434. doi: 10.21608/ejabf.2020.114293

39

Moss D. M. Rudis M. Henderson S. O. (1999). Cross-sensitivity and the anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome. J. Emergency Med.17, 503–506. doi: 10.1016/S0736-4679(99)00042-6

40

Mourelle M. L. Gómez C. P. Legido J. L. (2017). The potential use of marine microalgae and cyanobacteria in cosmetics and thalassotherapy. Cosmetics4, 46. doi: 10.3390/cosmetics4040046

41

N’Souvi K. Sun C. Che B. Vodounon A. (2024). Shrimp industry in China: overview of the trends in the production, imports and exports during the last two decades, challenges, and outlook. Front. Sustain. Food Syst.7, 1287034. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1287034

42

Nirmal N. Demir D. Ceylan S. Ahmad S. Goksen G. Koirala P. et al . (2024). Polysaccharides from shell waste of shellfish and their applications in the cosmeceutical industry: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.131119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131119

43

Nishikimi M. Rao N. A. Yagi K. (1972). The occurrence of superoxide anion in the reaction of reduced phenazine methosulfate and molecular oxygen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.46, 849–854. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(72)80218-3

44

Ohkawa H. Ohishi N. Yagi K. (1979). Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem.95, 351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3

45

Osman M. E. H. Abo-Shady A. M. Elshobary M. E. (2010). In vitro screening of antimicrobial activity of extracts of some macroalgae collected from Abu-Qir bay Alexandria, Egypt. Afr. J. Biotechnol.9, 7203–7208. doi: 10.5897/AJB09.1242

46

Osman M. E. H. Abo-Shady A. M. Elshobary M. E. Abd El-Ghafar M. O. Abomohra A. E.-F. (2020). Screening of seaweeds for sustainable biofuel recovery through sequential biodiesel and bioethanol production. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27 (26), 32481–32493. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09534-1

47

Øverland M. Mydland L. T. Skrede A. (2019). Marine macroalgae as sources of protein and bioactive compounds in feed for monogastric animals. J. Sci. Food Agric.99, 13–24. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2019.99.issue-1

48

Peixoto M. J. Salas-Leitón E. Pereira L. F. Queiroz A. Magalhães F. Pereira R. et al . (2016). Role of dietary seaweed supplementation on growth performance, digestive capacity and immune and stress responsiveness in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquacult. Rep.3, 189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2016.03.005

49

Pereira V. A. De Alencar D. B. De Araújo I. W. F. Rodrigues J. A. G. Lopes J. T. Nunes L. T. et al . (2020). Supplementation of cryodiluent media with seaweed or Nile tilapia skin sulfated polysaccharides for freezing of Colossoma macropomum (Characiformes: Serrasalmidae) semen. Aquaculture528, 735553. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735553

50

Queiroz A. C. S. Pereira R. Domingues A. F. Peixoto M. J. D. Gonçalves J. F. M. Ozorio R. O. (2014). Effect of seaweed supplementation on growth performance, immune and oxidative stress responses in gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata). Front. Mar. Sci.1. doi: 10.3389/CONF.FMARS.2014.02.00018

51

Rao X. Huang X. Zhou Z. Lin X. (2013). An improvement of the 2ˆ (–delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat. Bioinf. biomath.3, 71.

52

Sanjeewa K. Lee W. Jeon Y.-J. (2018). Nutrients and bioactive potentials of edible green and red seaweed in Korea. Fish. Aquat. Sci.21, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s41240-018-0095-y

53

Shao W. Ebaid R. El-Sheekh M. Abomohra A. Eladel H. (2019). Pharmaceutical applications and consequent environmental impacts of Spirulina (Arthrospira): An overview. Grasas y Aceites70, e292. doi: 10.3989/gya.2019.v70.i1

54

Sotoudeh E. Mardani F. (2018). Antioxidantall,.ynn parameters, digestive enzyme activity and intestinal morphology in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fry fed graded levels of red seaweed, Gracilaria pygmaea. Aquacult. Nutr.24, 777–785. doi: 10.1111/anu.2018.24.issue-2

55

Souza B. W. Cerqueira M. A. Bourbon A. I. Pinheiro A. C. Martins J. T. Teixeira J. A. et al . (2012). Chemical characterization and antioxidant activity of sulfated polysaccharide from the red seaweed Gracilaria birdiae. Food Hydrocol.27, 287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.10.005

56

Suzuki A. Nam V. H. (2023). Blue revolution in Asia: The rise of the shrimp sector in Vietnam and the challenges of disease control. Agric. Dev. Asia Afr.289. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-5542-6_21

57

Swift M. L. (1997). GraphPad prism, data analysis, and scientific graphing. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci.37, 411–412. doi: 10.1021/ci960402j

58

Tanna B. Mishra A. (2019). Nutraceutical potential of seaweed polysaccharides: Structure, bioactivity, safety, and toxicity. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf.18, 817–831. doi: 10.1111/crf3.2019.18.issue-3

59

Venkateswarlu V. Seshaiah P. Arun P. Behra P. (2019). A study on water quality parameters in shrimp L. vannamei semi-intensive grow out culture farms in coastal districts of Andhra Pradesh, India. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud.7, 394–399.

60

Vidhya Hindu S. Chandrasekaran N. Mukherjee A. Thomas J. (2019). A review on the impact of seaweed polysaccharide on the growth of probiotic bacteria and its application in aquaculture. Aquacult. Int.27, 227–238. doi: 10.1007/s10499-018-0318-3

61

Vieira M. V. Pastrana L. M. Fuciños P. (2020). Microalgae encapsulation systems for food, pharmaceutical and cosmetics applications. Mar. Drugs18, 644. doi: 10.3390/md18120644

62

Villamil L. Infante Villamil S. Rozo G. Rojas J. (2019). Effect of dietary administration of kappa carrageenan extracted from Hypnea musciformis on innate immune response, growth, and survival of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquacult. Int.27, 53–62. doi: 10.1007/s10499-018-0306-7

63

Wang Y.-C. Chang P.-S. Chen H.-Y. (2008). Differential time-series expression of immune-related genes of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei in response to dietary inclusion of β-1, 3-glucan. Fish Shellf. Immunol.24, 113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2007.09.008

64

Widiasa I. Susanto H. Ting Y. Suantika G. Steven S. Khoiruddin K. et al . (2023). Membrane-based recirculating aquaculture system: Opportunities and challenges shrimp farming. Aquacult.740224. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.740224

65

Yazici M. Zavvar F. Hoseinifar S. H. Nedaei S. Doan H. V. (2024). Administration of Red Macroalgae (Galaxaura oblongata) in the Diet of the Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Improved Immunity and Hepatic Gene Expression. Fishes9, 48. doi: 10.3390/fishes9020048

66

Zar J. H. (1984). Statistical significance of mutation frequencies, and the power of statistical testing, using the Poisson distribution. Biometr. J.26, 83–88. doi: 10.1002/bimj.4710260116

67

Zhang Z. Shi X. Wu Z. Wu W. Zhao Q. Li E. (2023). Macroalgae improve the growth and physiological health of white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquacult. Nutr.2023, 8829291. doi: 10.1155/2023/8829291

68

Zhu M. Wang C. Wang X. Chen S. Zhu H. Zhu H. (2011). Extraction of polysaccharides from Morinda officinalis by response surface methodology and effect of the polysaccharides on bone-related genes. Carbohydr. polym.85, 23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.01.016

69

Zhuang D. He N. Khoo K. S. Ng E.-P. Chew K. W. Ling T. C. (2021). Application progress of bioactive compounds in microalgae on pharmaceutical and cosmetics. Chemosphere132932. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132932

Summary

Keywords

gene expression, innate immunity, Pterocladia capillacea , polysaccharides, physiological status, shrimp feed

Citation

Ashour M, Ali FS, Mamoon A, Mansour AIA, Mabrouk MM, Mansour AT, Mohamed E and Abdelhamid AF (2025) Pterocladia capillacea polysaccharide enhances growth, immunity, digestive enzyme, antioxidant activities, and gene expressions of Litopenaeus vannamei. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1594751. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1594751

Received

17 March 2025

Accepted

02 June 2025

Published

26 June 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Kumbukani Mzengereza, Mzuzu University, Malawi

Reviewed by

Ahmed Mustafa, Purdue University Fort Wayne, United States

Islam Teiba, Tanta University, Egypt

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Ashour, Ali, Mamoon, Mansour, Mabrouk, Mansour, Mohamed and Abdelhamid.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohamed Ashour, microalgae_egypt@yahoo.com; Abdallah Tageldein Mansour, amansour@kfu.edu.sa; Ehab Mohamed, ehab.reda@uaeu.ac.ae

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.