- Faculty of Law, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China

This paper examines China’s evolving engagement with Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) in addressing illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. As the world’s largest fishing nation, China’s cooperation is crucial to achieving global fisheries sustainability. Through an analysis of legal instruments and case studies across eight RFMOs in which China participates, the study finds that China has progressively aligned its domestic regulations with RFMO measures—such as vessel licensing systems, observer programs, and IUU vessel blacklists. The incorporation of RFMO obligations into its national legislation, along with China’s cooperative approach toward RFMOs of which it is not a member, reflects a growing commitment to international fisheries governance. However, challenges remain. While China has actively engaged in RFMO decision-making processes, its cautious stance on certain issues highlights ongoing tensions both among member states and between states and international institutions. This study concludes that China’s regulatory reforms have enhanced its compliance and demonstrated its commitment to sustainable fisheries. However, further improvements in transparency and a more proactive role in international cooperation remain necessary. RFMOs provide valuable platforms for collaborative governance, and strengthening deeper and effective participation is essential to enhancing their overall function

1 Introduction

According to the Food and Agriculture Oganization (FAO), only 62.3 percent of fishery stocks are currently at sustainable levels, while 37.7 percent are classified as unsustainable (FAO, 2024a). It is estimated that illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing accounts for approximately 20 percent of the world’s total catch (FAO, 2024c), highlighting its severe impact on the sustainability of marine resources.

Ocean governance today is largely based on maritime zones. Coastal States exercise jurisdiction over fisheries within their national maritime zones under international law. In contrast, fisheries on the high seas fall under the purview of Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), which are established to manage and conserve fish stocks beyond national jurisdictions. However, the effectiveness of RFMOs depends heavily on the cooperation of their member states and cooperating non-members, especially in terms of compliance and enforcement.

China has emerged as a dominant force in the global fisheries sector. According to the FAO Yearbook of Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics 2021, China is the world’s largest producer in the fisheries industry. Over the past few decades, the country has expanded its domestic and distant-water fishing capacity and developed a robust seafood processing and export sector (FAO, 2024b). This growing prominence has placed increasing regulatory pressure on the Chinese government, particularly regarding oversight of its distant-water fishing fleet. In recent years, China has strengthened its fisheries legislation and enforcement mechanisms, signaling a shift toward greater cooperation with international and regional bodies—particularly in efforts to combat IUU fishing.

Since the 1990s, legal and policy responses to IUU fishing have received increasing attention at both international and national levels. The term “IUU fishing” was first formally introduced in 1997 by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). Since then, a range of hard-law and soft-law instruments has been developed. The United Nations has (UN) plays a pivotal role in highlighting and combating IUU activities. The UN General Assembly has adopted numerous resolutions aimed at identifying IUU fishing activities, outlining the associated harms, and advocating for effective countermeasures. The FAO of the United Nations has emerged as a key institution in the global fight against IUU fishing. In 2000, the FAO conducted the first comprehensive global review of IUU fishing (Bray, 2000). The FAO has since developed several soft-law instruments, including the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (FAO, 1995), the Compliance Agreement (Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas), the IPOA-IUU (International plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU Fishing, 2001), the global record of vessels, and various Voluntary Guidelines (FAO Voluntary Guidelines on Flag State Performance, 2014; FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Catch Documentation Schemes, 2017; FAO Voluntary Guidelines on the Marking of Fishing Gear, 2018; FAO Voluntary Guidelines on Transshipment, 2022). The FAO has also contributed to the development of binding legal instruments, such as the UN Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA) (Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, 1995) and the Agreement on Port State Measures (PSMA) (FAO, 2016).

A notable recent development is the adoption of the Third Implementing Agreement of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), which was opened for signature in June 2023. While the treaty still has a long path ahead, requiring ratification, approval, or accession by 60 States, its potential influence and interaction with RFMOs have drawn considerable attention in academia. It is important to note that the BBNJ Agreement is not intended to replace existing legal frameworks for managing the high seas but to complement them. Articles 5 and 22 of the BBNJ Agreement explicitly adopt a “not-undermining” principle, ensuring that the interpretation and application of the agreement, along with any management tools developed under it, should not undermine existing relevant legal instruments and frameworks (United Nations, 2023). Furthermore, the Agreement encourages coherence and coordination with regional bodies. Nonetheless, it is certain that RFMOs will continue to play a crucial role in managing global fisheries.

Existing scholarship on Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) has largely focused on their roles, performance, and regulatory measures, particularly concerning their overall effectiveness. Key aspects explored include transparency and decision-making processes (McDorman, 2005; Clark et al., 2015; Leroy and Morin, 2018; Fischer, 2022), IUU-related measures and inter-RFMO cooperation (Fujii et al., 2023; Andreassen, 2024), as well as compliance mechanisms and review procedures (Fabra, 2025) (Ewell et al., 2020). These studies demonstrate that the functionality and effectiveness of RFMOs are significantly influenced by the participation, enforcement, and cooperation of their member states and cooperating non-members, as well as the engagement of non-member states. In relation to China, a number of scholars have examined the development of Chinese fisheries management (Shen and Heino, 2014; Huang and He, 2019; Su et al., 2020) and China’s responsibilities as a flag State under international law (Xue, 2006; Serdy, 2010). However, limited academic attention has been paid to China’s interactions with RFMOs, particularly in the context of efforts to combat IUU fishing.

Against this background, this paper examines China’s attitude, development, and interaction with RFMOs in the context of combating IUU fishing. The study adopts a mixed-methods approach. First, it conducts a documentary analysis of both international legal instruments—particularly those of the United Nations and various RFMOs—and domestic regulatory frameworks, including Chinese fisheries legislation, administrative regulations, and departmental rules. Second, the study employs an empirical case study approach. Eight RFMOs in which China participates were selected, and their annual reports from 2021 to 2024 were analyzed to assess China’s positions, compliance records, and reported activities. Relevant Chinese legal documents were sourced from the PKU Law Database.

The paper is structured as follows. Following the introduction, Section 2 explores the evolution of international fisheries governance and the measures adopted by RFMOs to combat IUU fishing. Section 3 analyzes China’s interaction with RFMOs, focusing on its role as a major actor in global fisheries governance. Section 4 evaluates these interactions, identifying both achievements and persistent challenges. The paper concludes that while China has acknowledged the importance of addressing IUU fishing and has shown a cooperative—albeit cautious—approach toward RFMOs, further improvements are necessary. These include enhancing the domestic regulatory framework and strengthening international cooperation mechanisms. On China’s part, this entails implementing more robust legislative and enforcement measures. Simultaneously, RFMOs should improve mechanisms for accession, decision-making, compliance, and cooperation. A constructive starting point would be to deepen scientific and information-sharing collaboration.

2 RFMOs: vital players combating IUU fishing

2.1 The role of RFMOs in the international fisheries management regime

Fisheries management, deeply intertwined with politics, economics, law, and society, holds critical importance in global environmental governance. Recognizing this significance, the international community has adopted numerous instruments to enhance global fisheries management. Modern international law is rooted in the sovereignty and jurisdiction of States. Discussion of fisheries management should also begin with the allocation of jurisdiction. Historically, before the advent of long-distance voyages, the sea was regarded as a free domain, where all had the right to exploit its resources. The principle of freedom of the seas was dominant and continues to influence the development of the law of the sea today (Van Ittersum, 2006).

As technological advancements enhanced humanity’s ability to exploit marine resources, problems such as over-exploitation and disputes over maritime rights arose. To address these issues, the international community negotiated and established common rules, culminating in the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)—the most significant achievement in the law of the sea to date (Nemeth et al., 2014). UNCLOS introduced a globally accepted zonal management system for the ocean, defining concepts such as territorial seas, EEZs, and high seas (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982).

Under this system, the jurisdiction over inshore fishing activities is clearly delineated. Coastal States, motivated by the need to ensure the sustainability of their adjacent seas, have incentives as well as responsibility to better manage fisheries and combat IUU fishing. The 2015 ITLOS Advisory Opinion confirmed this, stating that “the primary responsibility for taking the necessary measures to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing rests with the coastal State,” while also emphasizing the flag State’s “due diligence obligation” to take all necessary measures to prevent IUU fishing by vessels flying its flag (ITLOS, 2015).

On the high seas, beyond coastal States’ jurisdiction, fishing activities operate largely under the principle of freedom of the seas. Here, management responsibilities primarily fall on the flag State, as per the “nationality principle” in international law (Mansell, 2009). However, issues such as “flag of convenience”, economic incentives to maximize harvests, and the limited enforcement capacities of some States undermine effective fisheries management (Le Gallic and Cox, 2006). These challenges create an environment conducive to IUU fishing, necessitating greater international cooperation. To bridge these gaps, the international community has increasingly relied on RFMOs. The IPOA-IUU stands as a landmark document in this effort. It emphasizes the role of RFMOs in addressing the limitations of the zonal management system and strengthening oversight on the high seas. The IPOA-IUU provides that “States, acting through relevant regional fisheries management organizations, should take action to strengthen and develop innovative ways, in conformity with international law, to prevent, deter, and eliminate IUU fishing.” Additionally, it states that “When a State fails to ensure that fishing vessels entitled to fly its flag, or, to the greatest extent possible, its nationals, do not engage in IUU fishing activities that affect the fish stocks covered by a relevant regional fisheries management organization, the member States, acting through the organization, should draw the problem to the attention of that State. If the problem is not rectified, members of the organization may agree to adopt appropriate measures, through agreed procedures, in accordance with international law.” Although the IPOA-IUU is a non-binding instrument, it reflects a growing trend toward empowering RFMOs and promoting responsible fisheries management on the high seas.

The legal foundation for RFMOs is embedded in a range of international documents, particularly in UNCLOS and the UNFSA. UNCLOS mandates cooperation in Articles 61-67, which pertain to the EEZs, and Articles 117-118, which address the high seas. Specifically, Article 118 of UNCLOS states, “States shall cooperate with each other in the conservation and management of living resources in the areas of the high seas…. They shall, as appropriate, cooperate to establish sub-regional or regional fisheries organizations to this end.” This provision underscores the critical need for States to collaborate in the formation and operation of RFMOs to ensure effective management of high seas resources. However, the provision also leaves considerable room for interpretation. Key questions arise, such as: What does the “obligation to cooperate” entail? Does this obligation require States to become members of the relevant RFMOs, or does it imply that RFMOs have the authority to “close” their competent areas, restricting access only to members and cooperating parties? Alternatively, does the obligation to cooperate simply involve more flexible duties, such as participation in scientific research and information exchange? The ambiguity of this provision leads to diverse interpretations and practices, depending on the specific legal and political context (Molenaar, 2022).

The UNFSA, signed in 1995, further elaborates on this requirement. Article 8 of the UNFSA stipulates that “Where a sub-regional or regional fisheries management organization or arrangement has the competence to establish conservation and management measures for particular straddling fish stocks or highly migratory fish stocks, States fishing for the stocks on the high seas and relevant coastal States shall give effect to their duty to cooperate by becoming members of such organization or participants in such arrangement, or by agreeing to apply the conservation and management measures established by such organization or arrangement.” This provision emphasizes that only by participating in these RFMOs or by agreeing to their conservation and management measures can States gain access to the relevant fisheries resources. Furthermore, Article 17 clarifies that States not participating in RFMOs or not agreeing to apply the measures are still obligated to cooperate, reinforcing the international legitimacy of RFMOs to enforce conservation and management on the high seas. The RFMOs discussed in this paper primarily refer to regional organizations that have the authority under international law to implement legally binding measures for better fisheries management (Ásmundsson, 2016).

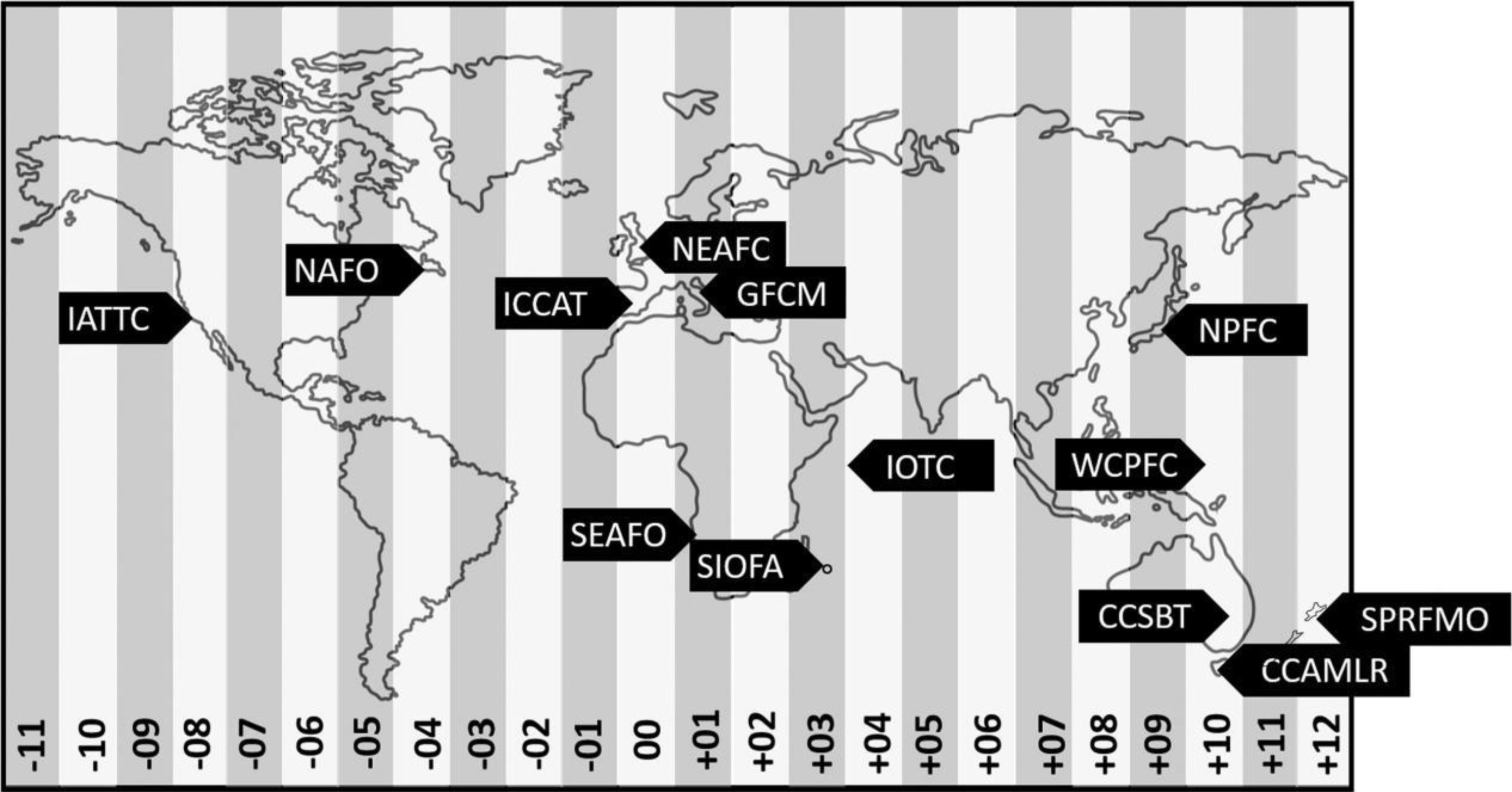

The number of RFMOs has grown over time, and currently, there are 5 tuna RFMOs and 8 general RFMOs (see Figure 1) (Haas et al., 2021), along with several specialized RFMOs. However, due to their specialized legal mandates, these specialized RFMOs are not discussed in detail in this paper.

Figure 1. Map of important RFMOs (Source: Haas et al., 2021).

2.2 RFMO measures against IUU fishing

Article 10 of the UNFSA outlines the obligations of States to cooperate in various aspects of fisheries management. These obligations include adhering to conservation and management measures, respecting catch limits and quotas, implementing recommended minimum standards, obtaining and evaluating scientific advice, and collecting, reporting, verifying, and exchanging data. States are also tasked with compiling and disseminating accurate statistical data, conducting scientific assessments, and cooperating to ensure effective monitoring, control, surveillance, and enforcement. Additionally, States are required to agree on procedures for the participation of new members, establish decision-making processes, promote the peaceful settlement of disputes, ensure cooperation between national authorities and industries, and publicize the measures taken. Most RFMOs have incorporated these measures into their regulatory framework.

2.2.1 Conservation and management measures

RFMOs can mandate that their members regulate fishing authorizations. First, RFMOs may impose restrictions on vessels and fishing gear. Only equipment that fulfills certain conditions is permitted for use in fishing activities. Second, RFMOs can adopt measures restricting catch levels, vessel numbers, fishing seasons, and fishing areas. These measures are based on scientific surveys and aim to maintain the sustainability of living marine stocks. Third, the management of particular species requiring special attention—such as deepwater fish or seabird bycatch—is also essential. CMMs are core, direct regulatory instruments of RFMOs. Their enforcement relies heavily on the actions of members and cooperating parties. CMMs also define the scope of fisheries under RFMO management and thus serve as the basis for identifying IUU fishing activities.

2.2.2 Monitoring, control and surveillance mechanisms

These measures are adopted to ensure compliance with and the effectiveness of RFMO rules. Activities of both States and vessels are subject to monitoring. For States, data collection, record-keeping, and communication form the foundation for improving compliance. Many RFMOs require members to maintain national records of fishing vessels, catches, fishers, and ports and to provide relevant information upon request to support monitoring and control of fishing activities. Periodic compliance reviews are also a critical tool for improving State compliance. Most RFMOs conduct annual reviews of how well their members adhere to established rules. By making the results public, members are further incentivized to take action to improve fisheries management.

Regarding vessels, RFMOs often require the implementation of Vessel Monitoring Systems (VMS). These satellite-based systems track the location and activities of fishing vessels in real time. RFMOs may set standards for the information that must be transmitted and for the format in which it is reported, ensuring close monitoring of vessel activities. In addition, boarding and inspection schemes are established, granting members the authority to conduct inspections on the high seas. This measure strengthens enforcement by allowing States to take direct action against suspected IUU activities, thereby increasing law enforcement presence in international waters. Lastly, observer programs are a vital component of RFMO strategies. These involve placing independent observers on vessels to collect scientific data and monitor compliance with RFMO measures. Members or cooperating parties are often required to incorporate observer programs into their national regulations, thereby creating an effective mechanism for oversight and data collection.

MCS mechanisms create incentives for improved compliance by both private parties and States. Efficient monitoring measures are essential for deterring and penalizing IUU fishing activities.

2.2.3 IUU fishing preventing measures

Several specific measures are particularly important in combating IUU fishing. First, RFMOs create IUU vessel lists, and cross-listing among RFMOs is undertaken to enhance cooperation and enforcement. Members and cooperating parties are obligated to monitor and take action against vessels on these blacklists. These lists can include vessels from non-cooperating States, vessels with a history of IUU fishing, and, in some cases, their owners and affiliated vessels. Notably, RFMOs can share IUU vessel lists with one another, thereby enhancing their deterrent effect.

Second, RFMOs adopt measures to prevent individuals from profiting from IUU-caught fish. Transshipment activities are targeted because they can conceal illegally caught fish and introduce them into the market. To prevent unauthorized transshipment, RFMOs may impose outright bans, establish specific conditions, or require monitoring and reporting of transshipment events. Port States are also required to take action. Since the landing and trading of fish typically occur at ports, port States play a crucial role in combating IUU fishing. RFMOs often mandate that members enforce stringent port measures, including the designation of specific ports for landings, setting conditions for port entry, requiring prior authorization, and conducting inspections. These measures help prevent IUU-caught fish from being offloaded and sold. Additionally, market-related measures are employed to restrict trade in IUU-caught fish. To enforce these restrictions, a robust documentation system is needed to trace the origin of seafood products. RFMOs can require their members and cooperating parties to implement trade documentation schemes, ensuring that only legally caught fish enter the market.

2.2.4 Other supportive functions

RFMOs also carry out several supportive functions to enhance global fisheries management. For example, RFMOs encourage the cooperation and contribution of members to scientific research and data sharing. Science-based fisheries management is crucial. RFMOs not only facilitate funding for scientific surveys but also promote the sharing of research results and the capacity-building of less developed countries. By providing a clearer understanding of sustainable fisheries, they underscore the importance of combating IUU fishing.

Furthermore, RFMOs facilitate cooperation and accession by non-member States and entities, recognizing that effective action against IUU fishing requires collaboration across jurisdictions. RFMOs exert pressure on stakeholders to engage. By keeping communication channels open and promoting reciprocal recognition of IUU vessel lists, RFMOs enhance the efficacy of their regulatory measures, fostering broader compliance and enforcement. Moreover, RFMOs play a key role in balancing the interests of coastal States and distant-water fishing nations. They provide crucial platforms for communication among members. By involving distant-water fishing nations in decision-making and enforcement processes, RFMOs contribute to building inclusive governance structures and help mitigate the free-rider problem (Pintassilgo et al., 2010). RFMOs also offer dispute resolution mechanisms and provide best practice guidance to their members.

However, it must be emphasized that the effectiveness of measures implemented by RFMOs largely depends on the actions of their members (Rayfuse, 2005). While RFMOs primarily focus on functions like information collection, record-keeping, publication, data exchange, monitoring, providing advisory services, and facilitating collective decision-making, their operational scope is often limited. Through recommendations, resolutions, and advice, RFMOs create a collaborative platform for decision-making and oversight. However, the active participation of coastal States and major players in the fisheries industry is crucial for ensuring the effectiveness of RFMO measures (Molenaar, 2020).

In summary, RFMOs play a pivotal role in filling governance gaps on the high seas, where flag-state jurisdiction is limited. Empowered by international law to enforce conservation and management measures, RFMOs have become crucial in the fight against IUU fishing. Their influence on achieving more responsible and sustainable fisheries management is significant, with extensive scholarly attention given to their functions and performance. Evaluations of their performance often focus on elements such as the precautionary and ecosystem approaches, decision-making processes, member participation, transparency, scientific advice and data, compliance and enforcement, cooperation, allocation, political will, overcapacity, socio-economic aspects, stakeholder engagement, management objectives, and surveillance frameworks (Haas et al., 2020).

Given their limited enforcement powers, the effectiveness of RFMO measures hinges significantly on the commitment of their members to implement them. This underscores the evolving role of RFMOs in addressing gaps in international fisheries management and highlights the importance of cooperation from major players in the industry, such as China.

3 China and RFMOs on combating IUU fishing

3.1 China’s fisheries management regime

Initially, IUU fishing did not receive significant attention from the Chinese government. However, as China’s fisheries industry — particularly its distant-water fishing sector — expanded, the country began facing social and political pressure from the international community (Xue, 2006). Alongside this external pressure, the Chinese government increasingly recognized the importance of environmental protection and sustainability. However, China also faces challenges in regulating IUU fishing. First, China has the largest fisheries sector in the world and operates the world’s largest distant-water fishing fleet. Second, while political pressure can serve as an incentive for China to improve its fisheries management, it may also provoke a defiant attitude—especially when the issue is perceived as a tactic employed by certain major powers. Third, domestic management and oversight mechanisms still require improvement, particularly given the involvement of multiple domestic authorities and the limited availability of publicly disclosed information (Shen and Heino, 2014; Gou and Yang, 2023). Nonetheless, as a rapidly developing nation, China has been actively working on strengthening its legal framework, particularly in areas related to the environment and sustainability.

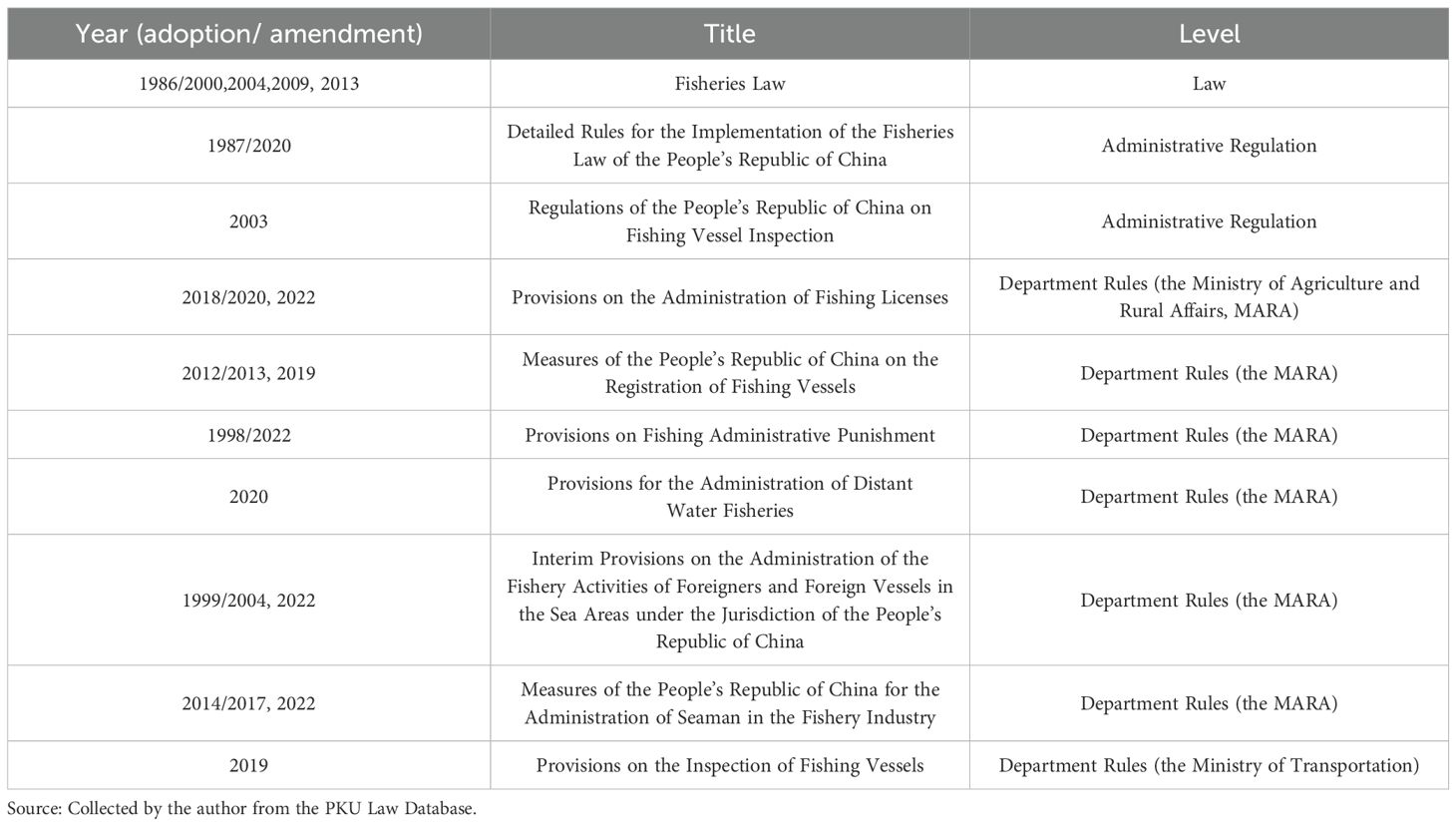

The Chinese Fisheries Law, promulgated in 1986, did not receive significant focus until the late 1990s. Since 2000, it has undergone four amendments (in 2000, 2004, 2009, and 2013) to address emerging challenges and align with evolving international standards (Fisheries Law of the People’s Republic of CHINA, 1986, 2013). Another amendment is currently in progress, as it has been included in the legislative work plan of the State Council for 2023 and 2024 (Legislative Work Plan of the Chinese State Council, 2024). These amendments reflect the Chinese government’s growing awareness of the need for robust regulation and management in the fisheries sector. Furthermore, China has issued several regulations at both the central and local levels to enforce the Fisheries Law. In recent years, China has significantly intensified its focus on fisheries management, establishing a more comprehensive legal framework (see Table 1).

The term “IUU fishing” appears in several regulatory documents, particularly in the context of international cooperation. Regulation of distant-water fishing on the high seas or jurisdictions of other States has seen significant improvements. A search for the keyword “distant-water fishing” in the PKU Law database reveals 38 regulatory documents issued by the MARA (and its predecessor, the Ministry of Agriculture) (Chinese Law Database). These documents cover a wide range of issues, including vessel registration, inspection and annual review of fishing vessels, fishing vessel renovation, observer management, and transshipment regulations. This indicates that the Chinese government has become more proactive in adopting and amending fisheries laws and regulations, extending the scope of these rules, and detailing their application. The enforcement system and instruments have also seen significant development. China enacted the Coast Guard Law, which grants the Coast Guard the authority to patrol, conduct supervisory inspections, investigate, and impose penalties to enforce fisheries management laws (Article 5, 12, and 23 of the Coast Guard Law of the Peoples’ Republic of China, 2021). Currently, a comprehensive management regime is in place, covering registration, authority of distant-water fishing licenses, reporting, monitoring, and vessel requirement (Shi, 2020).

3.2 China’s domestic implementation of RFMO obligations

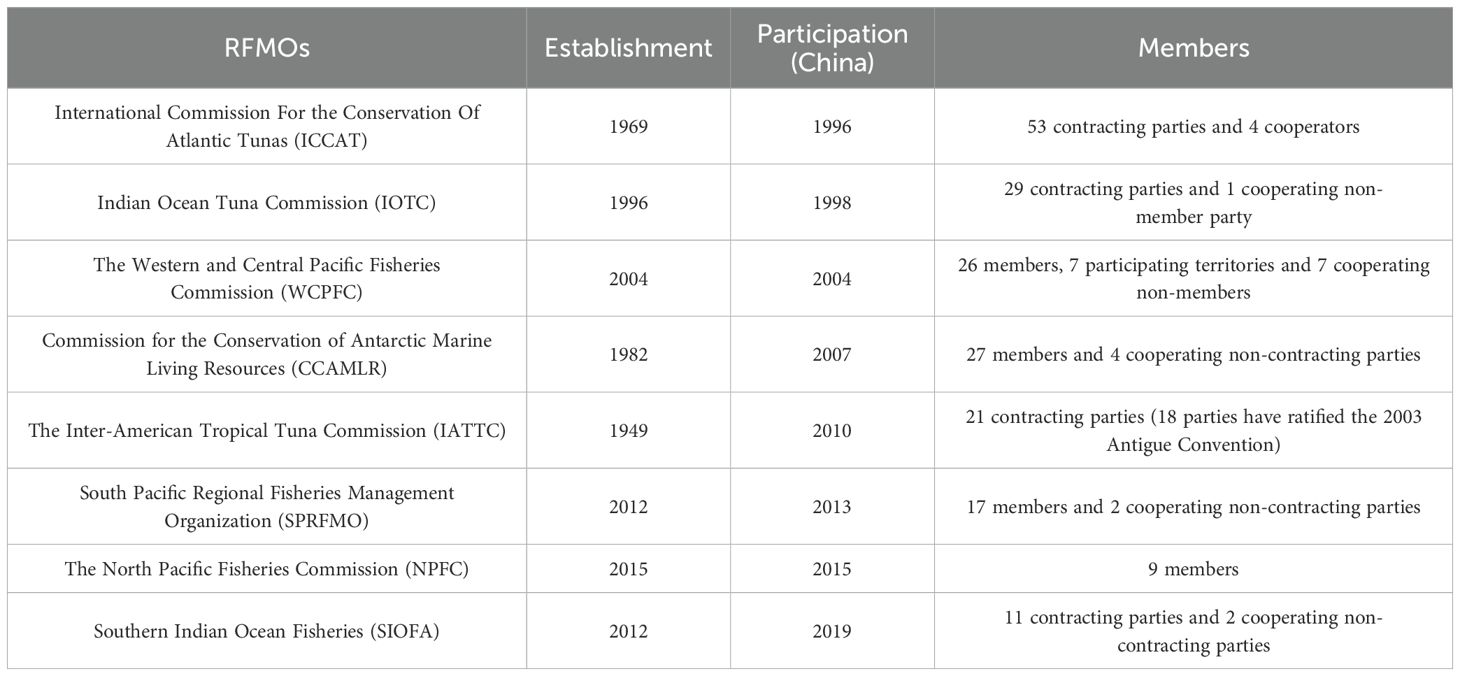

China has been dedicated to fulfilling its responsibilities under the RFMO frameworks, ensuring that its distant-water fishing activities are managed in accordance with international standards. So far, China has participated 8 RFMOs (see Table 2).

The Chinese government has made significant efforts to implement RFMO measures and integrate them into Chinese fisheries laws and management rules, particularly in the following areas.

3.2.1 General policy guidance

The MARA has issued a series of guidelines for managing distant-water fishing activities. The document titled Opinions on Promoting the High-Quality Development of Distant-Water Fisheries during the 14th Five-Year Plan Period (2022) outlines key directives. It emphasizes the need to “reasonably regulate the size of fishing fleets, scientifically plan fishing areas, continuously strengthen regulatory management, and rigorously combat IUU fishing activities.” The guidelines also advocate for “active participation in global fisheries governance, faithful fulfillment of international responsibilities and obligations, and the establishment of a responsible national image.”

These principles are integral to the daily operational framework. The document mandates the development of a comprehensive regulatory system for distant-water fishing, focusing on vessel monitoring, electronic fishing logs, remote video surveillance, regulation of high seas transshipment, and product traceability. It also highlights the importance of implementing a national observer program and enhancing independent oversight of high seas transshipment observers. The guidelines call for a “zero-tolerance” approach to illegal fishing, the establishment of a long-term regulatory mechanism, and full implementation of the compliance assessment system for distant-water fishing enterprises.

Regarding compliance with international law and international cooperation, the government is instructed to “actively participate in the affairs of international and regional fisheries management organizations and promote the establishment of a fair and equitable international fisheries governance order.” Additionally, China is encouraged to “actively research and advocate for accession to key international conventions related to distant-water fishing, implement the requirements of international laws such as the UNCLOS and the conservation and management measures of regional fisheries management organizations, and diligently fulfill international obligations.” The document further underscores the need to enhance capacity to meet international commitments, actively engage in international fisheries governance, strengthen high seas fisheries law enforcement and inspections, and collaboratively combat IUU fishing to protect and safeguard the rights and interests of China’s distant-water fishing.

Another significant document is the Action Plan for the “Year of Regulation Improvement” in Distant-Water Fishing of 2022 (Distant-Water Fishing, 2022). This plan outlines detailed annual tasks, including the “management of vessels on the high seas.” It emphasizes the need for the government to “strictly implement the conservation and management measures established by regional fisheries organizations and actively fulfill international due diligence obligations.”

The plan calls for a focus on enhancing compliance and monitoring measures for distant-water fishing vessels operating in high seas areas that are not yet managed by regional fisheries organizations, particularly in concentrated fishing areas. It also underscores the need to “strengthen the regulation of fishing vessels operating in the northern Indian Ocean and to impose stringent measures against illegal fishing activities.”

Furthermore, the document stresses the importance of continuing enforcement of high seas transshipment management. It recommends dispatching transshipment observers onboard where feasible, based on the prevailing pandemic situation, and promoting the installation and use of video surveillance on transport vessels to effectively implement high seas transshipment management.

3.2.2 Incorporation of RFMO measures in the regulatory system

The Chinese MARA have implemented several rules to integrate RFMO measures into China’s fisheries management regime. These rules provide clear guidance for vessel operators and owners to comply with RFMO requirements. Key areas of focus include:

1. Fisheries Activity Control: Vessels engaged in distant-water fishing must obtain licenses before operation. These licenses come with specific requirements regarding ownership, vessel specifications, crew qualifications, and fishing records. Operations are restricted to designated areas, and vessels must adhere to regulations concerning fishing methods, quotas, and reporting obligations (Provisions for the Administration of Distant Water Fisheries, 2020).

2. Protection of Bycatch Species: Chinese regulators mandate that vessels protect marine mammals, sea turtles, seabirds, and sharks. Operators are required to follow RFMO recommendations, equip their vessels with appropriate gear, and maintain accurate records and reports. Scientific support for bycatch protection is also emphasized (Notice on Strengthening the Protection of Bycatch Species in Distant-Water Fisheries, 2022).

3. Observer Programs: China actively participates in RFMO observer programs. The government has established a comprehensive system for the education, selection, deployment, and management of observers. Vessels are required to accommodate qualified observers and facilitate their work effectively (Notice from the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture on Strengthening the Management of National Observers in Distant-Water Fisheries, 2021).

4. High Seas Transshipment: A Notice from the Ministry mandates that all transshipment on the high seas must be reported. Vessels must comply with RFMO management measures, host transshipment observers, and ensure proper monitoring and data collection (Notice from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs on Strengthening the Management of High Seas Transshipment in Distant-Water Fisheries, 2020).

5. Vessel Monitoring Systems (VMS): The government has introduced regulations for VMS installation, daily reporting, maintenance, and utilization. Supervision and enforcement measures are also specified to ensure compliance (Notice from the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture on Issuing the “Management Measures for Monitoring the Positions of Distant-Water Fishing Vessels, 2017).

6. Incorporation of RFMO Vessel Lists: The government has issued a Notice regarding IUU vessel lists provided by participating RFMOs. Ports are required to integrate these lists into their surveillance systems, deny entry to listed vessels, and refuse services such as unloading, resupplying, or repairs (Joint Notice from the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and the General Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on Requesting Updates to the List of Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing Vessels for Port Control, 2017).

3.2.3 Specialized government documents in respond to RFMOs

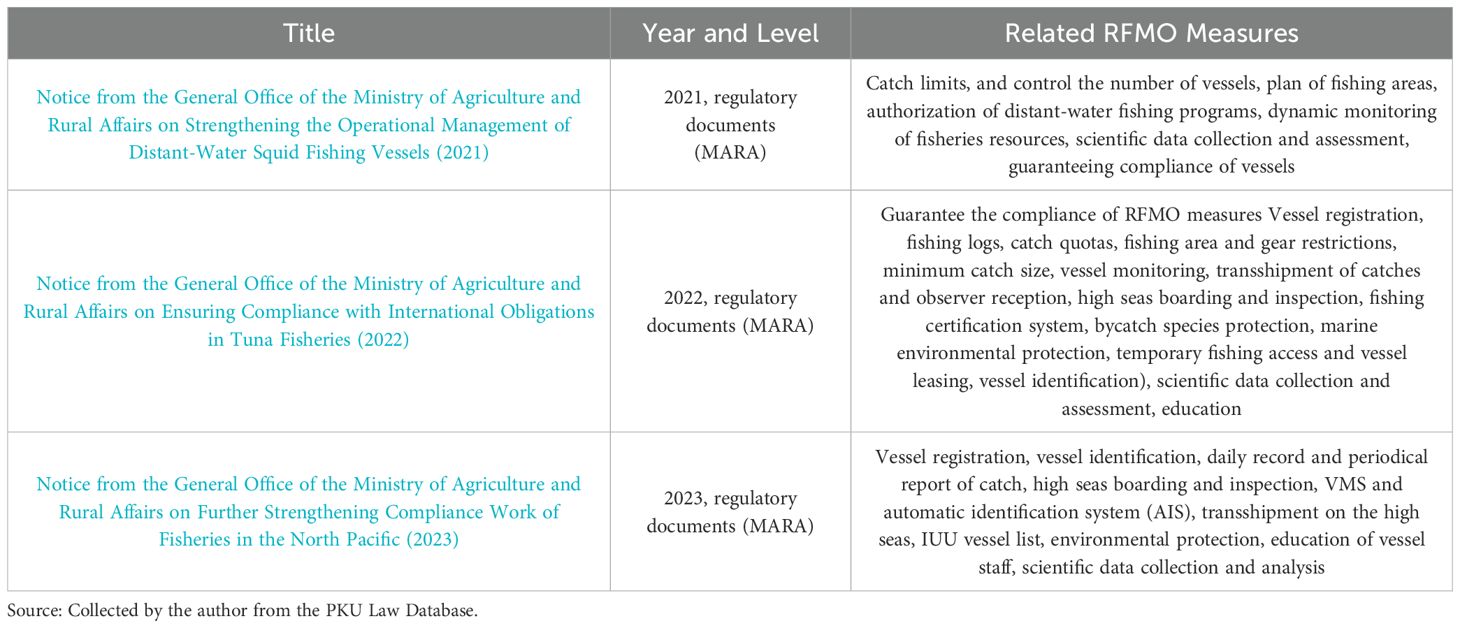

The MARA has issued a series of specialized documents to enhance cooperation among authorities and industries concerning specific species and regions. These documents address targeted areas of concern and outline specific measures to align with RFMO recommendations (see Table 3).

3.2.4 Punishment aligning with RFMO measures

China fulfill its flag-state obligations to impose penal to vessels conducting IUU fishing. In 2018 and 2020, the Chinese government issued three decisions addressing the investigation and punishment of companies or vessels suspected of violating RFMO fisheries management measures. Several vessels were penalized for reasons including unlicensed fishing activities, conducting unauthorized fisheries operations despite having a license, changing fishing methods or AIS settings without permission, illegal transshipment on the high seas, failing to fulfill reporting obligations, or document forgery. The imposed punishments included reductions in subsidies, cancellation or suspension of distant-water fishing licenses, fines and blacklisting of owners and captains, and notifying RFMOs to blacklist the vessels (Notice from the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs on the Investigation and Disciplinary Actions concerning Alleged Violations by Certain Distant-Water Fisheries Enterprises and Vessels, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, 2020, 2018; Notice from the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture on the Violations and Disciplinary Actions Concerning Certain Distant-Water Fisheries Enterprises and Vessels, 2018; Notice from the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs on the Investigation and Disciplinary Actions concerning Alleged Violations by Certain Distant-Water Fisheries Enterprises and Vessels, 2020).

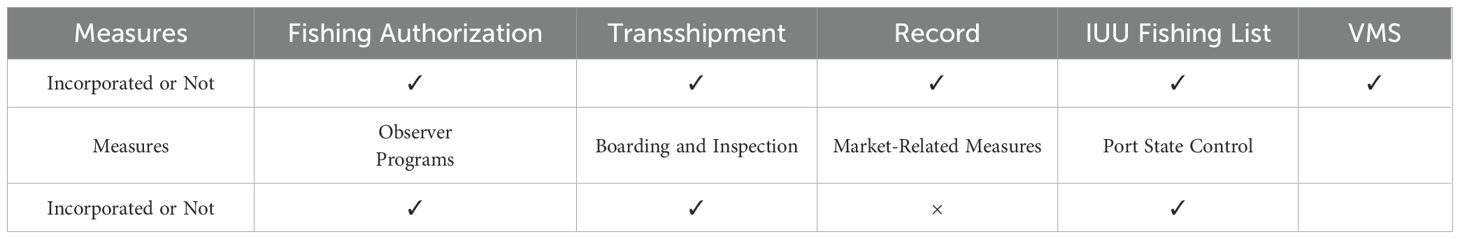

In summary, over the past two decades, China has made considerable strides in aligning its fisheries management practices with international standards and strengthening its collaboration with RFMOs, both as a member and a non-member. A variety of laws and regulatory documents have been established, contributing to a more robust and effective fisheries management system (see Table 4).

3.3 China’s engagement in RFMO decision-making

China has consistently expressed its commitment to being a “responsible major country” in the realm of fisheries management. This paper analyzes the annual reports issued from 2021 to 2024 by the eight RFMOs in which China has participated. The analysis reveals that China has played an increasingly active role in global fisheries management and several key points are highlighted to demonstrate China’s concern and contributions to the efforts of RFMOs.

3.3.1 ICCAT

ICCAT is the first RFMO that China joined, and it has remained an active member. In recent years, China has maintained a strong compliance record and has consistently fulfilled its financial obligations. ICCAT has served as a valuable platform for China to engage in communication, negotiations, and the protection of its fishing interests in the Atlantic Ocean.

A recent example of China’s engagement within ICCAT is its response to a submission by the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), an NGO that accused several Chinese vessels of engaging in IUU fishing and committing human and labor rights abuses. In response, China reported that it had conducted an investigation into the allegations and submitted its findings to ICCAT, refuting all accusations. At the same time, China questioned whether political motivations were involved in the case. ICCAT members, including the UK and the EU, concluded that there was no evidence to substantiate the claims made by the EJF. Subsequently, China supported Guatemala’s proposal that NGOs submitting allegations should hold observer status to prevent unfounded accusations (ICCAT, 2023).

3.3.2 IOTC

IOTC is primarily focused on the conservation and management of tuna and tuna-like species in the Indian Ocean. China has been an active participant in the IOTC and has consistently fulfilled its financial obligations to the organization. With a more comprehensive legal framework and an improved fisheries management system, China has made efforts to uphold its responsibilities, resulting in an increase in its compliance rate (IOTC 2025). China has advocated for a more cautious approach by the IOTC regarding third parties that submit vessel activity notifications. Specifically, China proposed an amendment to Resolution 18/03, which governs the establishment of a list of vessels presumed to have engaged in IUU fishing. The amendment seeks to restrict NGO submissions to only those organizations that hold official observer status with the IOTC, ensuring greater oversight and accountability in the submission process (IOTC, 2024).

3.3.3 WCPFC

WCPFC covers maritime areas near China’s coastline and has served as an important platform for China to communicate and collaborate with various stakeholders. In 2022, China expressed general support for the cross-listing of IUU vessels among RFMOs. However, it also raised two concerns regarding the implementation of this measure. First, China highlighted a legal issue: as it is not a member of all tuna RFMOs—specifically, it is a member of four tuna RFMOs but not of the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT)—there would be legal obstacles preventing it from taking enforcement actions based on cross-listed IUU vessel lists. Second, China pointed out the challenges associated with the delisting process, emphasizing the need for clear and fair procedures for removing vessels from IUU lists (WCPFC, 2022).

3.3.4 CCAMLR

CCAMLR was established to protect the unique and fragile ecosystem of Antarctica. China has demonstrated a cooperative attitude toward this objective, emphasizing the importance of a scientific approach in addressing core issues. Regarding krill fishing, China has adopted a cautious stance on proposals requiring 100% port inspections and automatic IUU listing, citing the specific characteristics of the krill fishery, such as its high operational costs and relatively low value in the context of IUU fishing (CCAMLR, 2022).

China has expressed support for the implementation of electronic reporting systems and the inclusion of relevant stakeholders in the decision-making process. At the same time, China has taken a more defensive position in areas where it perceives political factors to be at play. For instance, it has stressed the need for transparency in aerial surveillance activities and their associated reports. Additionally, China has underscored the importance of ensuring that all members have access to these reports so they can independently evaluate allegations and provide informed responses (CCAMLR, 2024).

3.3.5 IATTC

IATTC is another tuna RFMO in which China participates, covering the waters off the west coast of North and South America. Within this organization, China and the United States have disagreed on the inclusion of labor standards in the IATTC agenda. China has viewed the U.S. proposal as politically motivated and has maintained that labor issues should be addressed through domestic legislation, bilateral consultations, or discussions within relevant international organizations, such as the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the International Labour Organization (ILO). China has emphasized that it has already established domestic laws and regulations to address labor concerns. In China’s view, IATTC should remain focused on its primary mandate—marine living resource conservation and management (IATTC, 2024).

3.3.6 SPRFMO

SPRFMO was established in 2012, with China becoming a member the following year. Since then, China has actively participated in decision-making and the enforcement of measures within SPRFMO. One notable example illustrating China’s position is the discussion on the use of force during high seas boarding and inspection (HSBI) procedures.

As previously discussed, the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA) is a key legal instrument under the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). China actively participated in its negotiation process and signed the final agreement. Upon signing, China issued a statement regarding Articles 21 and 22 of the agreement. First, in reference to paragraph 7 of Article 21, which concerns enforcement actions taken by the inspecting State with the authorization of the flag State, China asserted that such actions should be considered an execution of the flag State’s authorization and must be strictly limited to the mode and scope specified in the authorization. Second, regarding subparagraph (f) of paragraph 1 of Article 22, which addresses the use of force during inspections, China emphasized that force should only be used when the personal safety of authorized inspectors is endangered due to violent resistance from crew members. Moreover, any use of force should be strictly limited to those committing the violence (UNTC, 2024).

In 2015, SPRFMO published its HSBI procedural measures (CMM 11-2015) (SPRFMO, 2015), stipulating that at-sea inspections should follow Articles 21 and 22 of UNFSA until a specific HSBI regime was established. In 2021, the United States submitted a proposal to formalize HSBI procedures, which was later revised multiple times to incorporate China’s suggested edits. During the 9th annual Commission meeting, China requested an amendment to explicitly exclude inspectors’ right to carry arms, citing concerns over the potential abuse of force and the need to protect the safety of fishermen. However, no consensus was reached among members (SPRFMO, 2021).

In 2022, two Chinese vessels were included in the SPRFMO provisional IUU list. China explained that its authorities had instructed the vessels not to accept the boarding and inspection team based on its interpretation of CMM 11-2015. After reviewing China’s explanation, the Commission ultimately decided not to include the vessels in the final IUU list (SPRFMO, 2021).

In 2023, SPRFMO adopted a final HSBI regime (CMM 11-2023). While the provision on the use of force largely mirrored Article 22(1)(f) of UNFSA, an additional footnote was included to address China’s concerns:

“Only when the personal safety of the Authorized Inspectors whose authorization has been duly verified is endangered or their normal inspecting activities are obstructed by the threat of violence by masters or crew members of the fishing vessel under inspection, may the inspectors take appropriate compulsory measures necessary to stop such threat of violence. Any force by the Authorized Inspectors will be only the force necessary to stop the threat of violence that was raised.”

This footnote reflects China’s position that the use of force should be strictly limited to situations involving a direct threat of violence against inspectors (SPRFMO, 2023).

3.3.7 NPFC

China became a member of the NPFC in the year of its establishment and has actively participated in NPFC scientific research activities. For instance, the Chinese research vessel Song Hang conducted multiple surveys from 2021 to 2023 in the NPFC Convention Area, covering fisheries resources, larval-juvenile fish distribution, plankton composition, and environmental assessments. These surveys provided fundamental data and biological tissue samples for further analysis (NPFC, 2024).

NPFC has also assisted China in strengthening its investigation and management framework for addressing IUU fishing vessels in the North Pacific. In 2022, five Chinese vessels without markings were identified as violating the NPFC’s compliance scheme. China acknowledged these findings and committed to implementing measures to prevent recurrence. Additionally, Japan identified six vessels engaged in fishing activities without proper registration. China explained that the issue resulted from an internal process error, which was subsequently rectified. To prevent similar occurrences, China established new working procedures to improve vessel management. Furthermore, Japan identified one vessel whose appearance did not match the photo submitted during registration. China clarified that the vessel had undergone multiple safety-related modifications that did not alter its key parameters. In response to these compliance issues, all seven vessels received significant administrative penalties (NPFC, 2021).

In 2023, Japan nominated six Chinese-flagged vessels for NPFC review, with three suspected of unauthorized transshipment, one reportedly denying a high seas boarding and inspection, and two involved in various other offenses. China actively communicated with the relevant States, committed to conducting further investigations, and pledged to take effective enforcement actions (NPFC, 2023).

3.3.8 SIOFA

Most RFMOs welcome new members or cooperating parties, and some directly invite China to attend meetings, ultimately leading to its accession. A typical example is the Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFA). SIOFA allows observers to attend meetings and is open for accession to all FAO members. Between 2000 and 2017, China primarily operated three different types of fisheries within the SIOFA area. In 2016, China became an observer and, in 2018, officially addressed SIOFA members, delivering a statement affirming its commitment as a responsible fishing State. China expressed its intent to regulate and manage its fleet while respecting and appreciating SIOFA’s conservation and management measures. Moreover, China declared its interest in obtaining full contracting party status within SIOFA. In September 2019, China formally joined the organization (SOFIA, 2020).

Since joining SIOFA, China has actively participated in its activities, including conducting multiple scientific surveys. China also plans to continue engaging in scientific research to enhance understanding of the ecosystem and marine environment. Furthermore, it has committed to submitting relevant data to the Scientific Committee, ensuring the outcomes of its research contribute to SIOFA’s broader scientific objectives (SIOFA, 2024).

3.4 China’s cooperative engagement with non-member RFMOs

China also perform cooperatively for RFMOs that it has not yet been a member. This happens both for the Agreement for the Establishment of a General Fisheries Council for the Mediterranean (GFCM) and the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT).

China is not a member of the GFCM, but it has maintained effective communication with the organization. In 2014, the GFCM contacted the Chinese authorities, reporting that three China-flagged vessels were sighted in the Mediterranean Sea. China promptly investigated the matter, providing the GFCM with vessel tracking data and explaining that the two vessels in question were transiting through the Mediterranean en route to the Atlantic Ocean, with no illegal fishing activities detected. The communication was described as “prompt, clear, and detailed (GFCM, 2015).”

Similarly, China is not a member of the CCSBT which is the only tuna RFMO that China does not participate in. In 2017, three vessels, including the Yuan Da 19, were found engaging in IUU fishing in the area under CCSBT’s jurisdiction. CCSBT included these vessels in its Draft IUU Vessel List and communicated this to China. In response, China conducted a thorough investigation and imposed strict penalties: the company and vessel owner were permanently disqualified from engaging in deep-sea fishing activities, the captain’s certificate was revoked, substantial fines were imposed, and the responsible managers were blacklisted. Despite these actions, the vessels were later found authorized to fish in the IATTC region, prompting the CCSBT to seek clarification from China. China reiterated its punitive measures and received a positive response from the CCSBT, leading to the vessels not being blacklisted (CCSBT, 2017a).

Subsequently, the MARA issued a Notice clarifying that China has not joined the CCSBT and therefore does not have a quota for catching Southern Bluefin Tuna. The ministry emphasized that Chinese fishing vessels are strictly prohibited from catching, retaining, transshipping, or unloading Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT, 2017b). Any accidental catch of Southern Bluefin Tuna must be immediately released and recorded in the fishing log.

These cases demonstrates that China maintains a positive stance towards cooperation with RFMOs even when it is not yet a member. When an RFMO reaches out to China and provides evidence of potential violations, China has shown a willingness to take appropriate actions and adhere to the measures prescribed by the RFMO.

4 Assessment of China-RFMO interactions in combating IUU fishing

4.1 China has incentives to improve fight against IUU and cooperation with RFMOs

China has been an important participant in the world fisheries sector since the 1980s. According to the FAO Fisheries Yearbook, China has been the biggest producer in capture marine fisheries production and biggest exporter (FAO, 2024b). With the large population and economic growth, it also has the biggest aquatic food market. Distant-water fishing has also developed significantly in China. According to the Chinese government, China had 177 approved distant-water fishing enterprises and 2551 registered distant-water fishing vessels, among which 1498 are high seas fishing vessels. Chinese vessels operate on the high seas of the Pacific, India, and Atlantic oceans (The State Council of People’s Republic of China, 2023).

With this development, however, China began to face increasing international pressure of building a responsible management. Most critiques come from relevant jurisdictions, scholars, media and international organizations. The criticism mostly concentrates on lack or slow work of management of vessels as flag States, subsidies and encouraging policies for distant-water fishing, lack of information publicity and cooperation mechanism, loose measures combating IUU, etc (Mallory and Panel, 2012). Outside pressure generates great motivation for the Chinese government to improve its fisheries regulation.

More importantly, the Chinese government begin to realize the importance of environmental sustainability. Sustainable development is proposed as a national strategy in 1995. In 2017, the report of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China identified high-quality development as the primary goal, instead of high-speed development, in which sustainability is regarded as an important aspect (The State Council of People’s Republic of China, 2017). This fundamental evolution encouraged faster speed of improvement of fisheries management and more positive attitude towards international cooperation. The actions of the Chinese government can be seen from section 3 discussed above.

Developing an effective management system is not easy. Important preconditions include the establishment of a complete fisheries management regime, development of a competent enforcement system, adequate financial and technical resources, as well as cross-border cooperation through bilateral, multilateral and international instruments. The more active attitude of the Chinese government provides an opportunity for China to considerate its fisheries management regime, improve the enforcement and better combating IUU cooperating with RFMOs.

4.2 China has taken a cooperative attitude with RFMOs to combat IUU fishing

Observing China’s interactions with RFMOs, several key points are noteworthy. First, China has actively participated in the RFMOs of which it is a member and has generally maintained a strong record in terms of financial contributions and compliance. China has committed to being a responsible fishing state by improving its legal and management systems in accordance with RFMO requirements. Additionally, China has played an active role in decision-making and the enforcement of conservation measures, using RFMOs as platforms for communication with stakeholders and the protection of its interests. While political considerations are sometimes unavoidable, RFMOs provide a valuable forum for discussion rather than confrontation. China respects the authority of RFMOs and opposes unilateral actions outside these frameworks. Furthermore, China has demonstrated support for scientific research, which contributes to the long-term sustainability of marine living resources.

Second, China has remained open to joining new RFMOs and has exhibited a cooperative attitude toward those it has not yet joined. The obligation to cooperate with RFMOs has not yet developed into customary international law, meaning that legal commitments arise only through membership. Although China has not ratified the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA), it has joined eight RFMOs. In cases where unauthorized fishing by Chinese-flagged vessels has been identified in RFMO-regulated areas, China has been willing to engage in dialogue and take corrective measures. Moreover, the Chinese government has issued official documents restricting vessels from operating in these areas. This reflects China’s broader commitment to responsible fisheries management.

Third, China has generally adopted a cautious approach in its interactions with RFMOs. It maintains that limited resources should be directed toward addressing core fisheries management issues, while broader, unrelated matters should be handled by specialized international organizations. In particular, China has taken a careful stance on the use of force in fisheries enforcement. This position was evident both during China’s engagement with the UNFSA negotiations and in its actions within RFMOs.

4.3 Legal foundation for China to enhance international IUU cooperation needs to be strengthened

The authority of RFMOs to implement conservation and management measures is primarily derived from UNCLOS and the UNFSA. UNCLOS provides a general framework, while the UNFSA offers more specific and detailed provisions. China is a contracting party to UNCLOS and signed the UNFSA when it was created, but has not ratified the latter, possibly because the statement concerning Article 21 and 22 did not receive positive responses. This means that the UNFSA is not legally binding on China.

As previously discussed, the obligations imposed by UNCLOS on States to cooperate are somewhat general and open to interpretation. Although the UNFSA provides more precise guidelines, it has not been ratified by China, and it focuses primarily on straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks rather than covering all species. Nevertheless, China’s participation in or cooperation with RFMOs can be interpreted as a de facto recognition of its responsibility to adhere to RFMO measures (Yu, 2022). However, a clearer and more consolidated legal foundation would better ensure the effective implementation of these measures.

China has demonstrated a positive attitude toward improving fisheries management and has expressed a greater commitment to international cooperation in combating IUU fishing. Recently, China acceded to the key international fisheries management treaty, the PSMA, marking a significant step for China to improve its port state measures. marking a significant step toward strengthening its port state measures. However, it has not yet ratified the most important treaty concerning RFMOs, the UNFSA. China should consider ratifying UNFSA, which would further strengthen its fisheries management regime and provide a more robust legal basis for cooperation with other States, RFMOs, and international organizations.

4.4 Chinese legal regime for fisheries management needs further improvement

While it is undeniable that China has made significant efforts to enhance its fisheries management regulatory instruments and has introduced numerous rules to align with the development and requirements of RFMOs, there is still space for further advancements.

Fisheries management is primarily undertaken by the MARA, which serves as the competent authority for fisheries management and international cooperation on fisheries. MARA’s responsibilities include drafting fisheries development policies and plans, guiding sustainable aquaculture practices, and overseeing the processing and distribution of aquatic products. Additionally, MARA handles major international fisheries disputes and safeguards the rights and interests of national marine and freshwater jurisdictional waters according to its assigned responsibilities. It is also in charge of organizing the protection of the ecological environment of fishery waters and aquatic wildlife, supervising the implementation of international fisheries treaties, managing distant-water fishing, and overseeing fisheries administration and fishing ports (MARA, 2019).

Currently, most of the management rules take the form of regulatory documents (such as Notices) or policies rather than laws. The relatively low status of these rules within the legal system may affect their enforcement, particularly when enforcement requires cooperation from other departments, such as the Coast Guard. It can be observed that most of the RFMO measures fall within the competence of MARA has been incorporated into the rules. However, measures needing cooperation of other departments, for example, market-related measures are still not involved by the management system. Additionally, the keyword “Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated fishing” is not explicitly incorporated in the Chinese Fisheries Law. While MARA has included the term “illegal fishing” in the draft amendment to the Fisheries Law (MARA, 2019), the absence of specific mention of IUU fishing may reduce the emphasis on combating it.

Therefore, an amendment of the fisheries laws as well as a systematic improvement of the enforcement system with clearer grants of power could enhance efforts to combat IUU fishing and improve the implementation of RFMO measures.

4.5 Enhanced cooperation between China and RFMOs is essential for combating IUU fishing

China has consistently emphasized its commitment to being a responsible fishery nation and has pledged to adhere to international fisheries law and RFMO measures. However, further steps can be taken both by China and the RFMOs to deepen cooperation between China and RFMOs, ensuring more effective joint efforts against IUU fishing.

From the perspective of China, several work can be done. First, a rapid response mechanism should be established. There is a pressing need to establish a more efficient and responsive mechanism, especially concerning RFMOs in which China is not yet a participant. Enhanced communication and consultation channels are vital for addressing potential conflicts and facilitating smoother collaboration.

Second, China should enhance its engagement in the implementation of RFMO measures. An effective global fisheries management system requires not only member compliance but also robust supervisory mechanisms. China should take a more proactive role in accession negotiations, decision-making within RFMOs, and active participation in inspection and observer programs. Additionally, continuously contributing to the scientific underpinnings of RFMO activities will necessitate substantial investment in resources and personnel.

Third, China could provide more transparent information concerning its efforts on managing distant-water fishing and combating IUU fishing. The creation of a comprehensive system for the collection, analysis, publication, and exchange of accurate data is crucial. Investigation results, enforcement decisions, and assessment outcomes should also be published in time. Such a system would enhance the deterrence and monitoring of IUU fishing and provide a solid foundation for future management strategies.

Improvements to RFMOs are also necessary to further facilitate cooperation with China. First, fair and transparent negotiation and decision-making processes are essential. Given the political sensitivity of fisheries issues and the evolving global order, it is imperative to establish more equitable and transparent mechanisms for negotiations and decision-making. Such reforms would likely encourage broader participation from all stakeholders. One of China’s key positions is that RFMOs should adopt a more cautious approach when allowing the submission of allegations, ensuring due process for relevant States to respond and engage in dialogue.

Second, RFMOs need to strengthen their compliance and deterrence mechanisms. The effectiveness of RFMO measures largely depends on the commitment of member States to enforce them. To increase pressure on States to participate or cooperate, improving the implementation of measures by existing members is crucial. The introduction of performance reviews, adjudication mechanisms, and other evaluative tools could incentivize States to enhance their fisheries management practices. The interaction between RFMOs and China serves as a valuable example. Although there is still room for improvement, China’s cooperation—given its status as one of the world’s largest fishing nations—has significantly contributed to enhancing the effectiveness of the RFMO regime.

Third, better support systems could help improve the function of RFMOs. Efforts to combat IUU fishing should extend beyond RFMOs, requiring cooperation with other international organizations, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO). Collaboration with these entities could increase pressure on non-member States to engage in responsible fisheries management.

By addressing these key areas, China and RFMOs can strengthen their partnership and significantly advance global efforts to combat IUU fishing.

5 Conclusion

As the world’s largest fisheries nation, China bears significant responsibility for contributing to the sustainability of global living marine resources and improving both domestic and international fisheries management. IUU fishing remains a critical challenge under the current international law of the sea. While the establishment of RFMOs has been instrumental in addressing this issue, the effectiveness of their conservation and management measures largely depends on the cooperation and commitment of relevant parties.

China’s distant-water fishing industry has experienced rapid growth, creating pressure for the country to establish a more robust and responsible management regime. China has adopted a cooperative yet cautious approach towards RFMOs, it has made substantial efforts to align with RFMO measures by developing numerous rules and regulatory instruments. Furthermore, China has maintained a positive stance towards RFMOs of which it is not yet a member. However, several areas still require improvement.

Domestically, China must enhance its legal framework and enforcement mechanisms to more effectively combat IUU fishing and to strengthen its collaboration with RFMOs. Internationally, China needs to adopt a more proactive approach in reinforcing the legal foundations for improved fisheries management and in participating more actively within the global fisheries management system.

RFMOs, on their part, need to refine their accession procedures, decision-making processes, compliance mechanisms, and cooperative frameworks to fulfill their responsibilities more effectively. In the immediate term, China and RFMOs can begin by enhancing information exchange and scientific cooperation. Such initiatives would significantly bolster China’s participation in global fisheries management and address resource shortages faced by RFMOs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SL: Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Conceptualization, Supervision, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This paper is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3132023531) and Liaoning Province Economic and Social Development Research Project (2024lslqnrckt-025).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas, adopted Nov. 24, 1993, 2221 UNTS 91 (entered into force April 24, 2023)

Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, opened for signature Dec. 4, 1995, 2167 UNTS 3, 34 ILM 1542 (entered into force Dec. 11, 2001)

Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, adopted Nov. 22, 2009, [2010] ATNIF 41 (entered into force June 5, 2016)

Andreassen I. S. (2024). The role of tuna-RFMOs in combating ‘ghost fishing’: Where is the Catch? Marine Policy 167, 106239. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106239

Ásmundsson S. (2016). Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs): Who Are They, What Is Their Geographic Coverage on the High Seas and Which Ones Should Be Considered as General RFMOs, Tuna RFMOs and Specialised RFMOs, Tuna RFMOs and Specialised RFMOs. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/mar/soiom-2016-01/other/soiom-2016-01-fao-19-en.pdf (Accessed March 15, 2025).

Bray K. (2000). A Global Review of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing, FAO, Document AUS/2000/6 (Rome: FAO). Available online at: https://www.fao.org/4/Y3274E/y3274e08.htmbm08.

CCAMLR (2022). Report of the Standing Committee on Implementation and Compliance (SCIC). Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/system/files/meeting-reports/e-scic-2022-rep_0.pdf (Accessed March 20, 2025).

CCAMLR (2024). Report of the Standing Committee on Implementation and Compliance (SCIC). Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/system/files/meeting-reports/SCIC-2024%20Compiled%20v5.pdf (Accessed March 20, 2025).

CCSBT. (2017a). Draft IUU Vessel List, CCSBT-CC/1710/07. Available online at: https://www.ccsbt.org/system/files/CC12_07_Draft%20IUU%20Vessel%20List.pdf (Accessed August 31, 2024).

CCSBT. (2017b). Relationship with Non-members, CCSBT-EC/1710/14. Available online at: https://www.ccsbt.org/system/files/EC24_14_RelationshipWithNonMembers.pdf (Accessed August 31, 2024).

Clark N. A., Ardron J. A., and Pendleton L. H. (2015). Evaluating the basic elements of transparency of regional fisheries management organizations. Marine Policy 57, 158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.003

Coast Guard Law of the People's Republic of China, promulgated Jan. 22, 2021, entered into force Feb. 1, 2021

Ewell C., Hocevar J., Mitchell E., Snowden S., and Jacquet J. (2020). An evaluation of Regional Fisheries Management Organization at-sea compliance monitoring and observer programs. Marine Policy 115, 103842. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103842

Fabra A. (2024). “Challenges in RFMO compliance review mechanisms,” in International Fisheries Law (Oxford: Taylor & Francis), 56–69.

FAO. (2001). IPOA-IUU (International plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU Fishing) (Rome, Italy: FAO). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/y1224e.

FAO. (2015). FAO Voluntary Guidelines on Flag State Performance (Rome, Italy: FAO). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i4577t.

FAO. (2017). Voluntary Guidelines for Catch Documentation Schemes (Rome, Italy: FAO). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i8076en.

FAO. (2019). Voluntary Guidelines on the Marking of Fishing Gear (Roma, Italy: FAO). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/ca3546t.

FAO. (2023). Voluntary Guidelines on Transshipment (Rome, Italy: FAO). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cc5602t.

FAO (2024a). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 - Blue Transformation in action (Rome: FAO). doi: 10.4060/cd0683en

FAO. (2024c). Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/iuu-fishing/fight-iuu-fishing/en/ (Accessed August 31, 2024).

Fischer J. (2022). How transparent are RFMOs? Achievements and challenges. Marine Policy 136, 104106. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104106

Fisheries Law of the People’s Republic of China, promulgated Jan. 20, 1986, entered into force July 1, 1986.

Fujii I., Okochi Y., Kawamura H., and Makino M. (2023). Potential cooperation of RFMOs for the integrity of MCS: Lessons from the three RFMOs in the Asia-Pacific. Marine Policy 155, 105748. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105748

GFCM (2015). Compliance Committee Intersessional Meeting, XXXIX/2015/Inf.11. Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/cc77a1ce-c6ba-4a42-901a-241d984cb9ec/content (Accessed August 31, 2024).

Gou Y. and Yang C. (2023). Dilemmas and paths of international cooperation in China’s fight against IUU fishing analysis. Marine Policy 155, 105789. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105789

Haas B., Davis R., and Hanich Q. (2021). Regional fisheries management: Virtual decision making in a pandemic. Marine Policy 125, 104288. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104288

Haas B., McGee J., Fleming A., and Haward M. (2020). Factors influencing the performance of regional fisheries management organizations. Marine Policy 113, 103787. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103787

Huang S. and He Y. (2019). Management of China’s capture fisheries: Review and prospect. Aquacult. Fish. 4, 173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.aaf.2019.05.004

IATTC. (2024). Minutes of the 102nd Meeting of the IATTC. Available online at: https://www.iattc.org/GetAttachment/36b55902-5b93-457e-ada1-3683bec1ef84/IATTC-102-MINS_102nd-Meeting-of-the-IATTC.pdf (Accessed March 20, 2025).

ICCAT (2023). Report for biennial period, 2022-23, PART II. Available online at: https://www.iccat.int/Documents/BienRep/REP_EN_22-23_II-1.pdf (Accessed March 20, 2025).

IOTC. (2025). IOTC-2025-CoC22-sCR03(Summary)-CHINA, IOTC 2025 Summary Compliance Report for CHINA. Available online at: https://iotc.org/documents/china-21 (Accessed March 20, 2025).

IOTC (2024). Res18-03 Amendment Proposal (China). Available online at: https://iotc.org/documents/Com/28/PropF_E (Accessed March 20, 2025).

Le Gallic B. and Cox A. (2006). An economic analysis of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing: key drivers and possible solutions. Marine Policy 30, 689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2005.09.008

Leroy A. and Morin M. (2018). Innovation in the decision-making process of the RFMOs. Marine Policy 97, 156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.05.025

Mallory G. T. and Panel V. (2012). China as a Distant Water Fishing Nation, US-CHINA Economics and Security Review Commission (John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies). Available at: https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/1.26.12mallory_testimony.pdf.

Mansell J. N. (2009). Flag State Responsibility: Historical Development and Contemporary Issues (Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag).

McDorman T. (2005). Implementing existing tools: Turning words into actions–Decision-making processes of regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs). Int. J. Marine Coast. Law 20, 423–457. doi: 10.1163/157180805775098595

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. (2022). Opinions on Promoting the High-Quality Development of Distant-Water Fisheries during the 14th Five-Year Plan Period (Beijing: Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs). Available online at: http://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/YYJ/202202/t20220215_6388748.htm.

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. (2022). “Action plan for the “Year of regulation improvement”,” in Distant-Water Fishing. Beijing. Available online at: http://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/YYJ/202203/t20220328_6394417.htm.

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. (2020). Provisions for the Administration of Distant Water Fisheries. Beijing. Available online at: http://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/nyncbgzk/gzk/202112/P020211207602889925101.pdf.

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. (2022). Notice on Strengthening the Protection of Bycatch Species in Distant-Water Fisheries. Beijing. Available online at: http://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/YYJ/202204/t20220406_6395583.htm.

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. (2021). Notice from the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture on Strengthening the Management of National Observers in Distant-Water Fisheries. Beijing. Available online at: http://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/YYJ/201101/t20110111_1804818.htm.

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. (2020). Notice from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs on Strengthening the Management of High Seas Transshipment in Distant-Water Fisheries. Beijing. Available online at: http://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/YYJ/202005/t20200521_6344904.htm.

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. (2017). Notice from the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture on Issuing the “Management Measures for Monitoring the Positions of Distant-Water Fishing Vessels. Beijing. Available online at: http://www.moa.gov.cn/nybgb/2014/shiyi/201712/t20171219_6111611.htm.