Abstract

As traditional risks in global ocean governance continue to deteriorate and new challenges emerge, the state-centered pattern of the international rule-making approach often demonstrates inefficiency and lack of fairness, hindering the achievement of SDG 14 and damaging the common interests of the international community. In this context, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has successfully participated in the development of international legal rules over the past few decades, providing valuable perspectives for improving international rule-making in ocean governance as a non-state actor. However, due to various internal and external factors, the potential of this pattern is still limited. Therefore, to compensate the inherent shortcomings of state-led mechanisms for developing international legal rules, non-state actors including non-governmental organizations and organizations of hybrid nature are encouraged to deeply participate in and even lead the international rule-making in ocean governance, while maintaining their neutrality and representativeness. This paper not only further clarifies the role of non-state actors in environmental and ocean governance, but can also contribute to the study of contemporary development models of the law of the sea.

1 Introduction

Since the 20th century, global ocean governance (van Doorn et al., 2015) has been considered essential for managing the oceans and promoting their health and productivity for present and future generations (European Commission). Ocean governance includes the processes of making norms, implementation, and monitoring (Blythe et al.). International rules and standards are vital tools for coordinating the actions of states and international organizations to promote ocean governance due to the fluid and connected nature of the oceans. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is a comprehensive legal instrument for ocean governance that controls most human activities at sea (Churchill and Lowe, 1999). However, UNCLOS provides only a broad framework, and States are required to develop detailed rules and standards to regulate specific activities and conduct ocean-related actions. Therefore, responsible and effective international rule-making is key to achieving good governance of the oceans.

However, resource disparities, wealth, and industries vary greatly from country to country, and different parties to the international rule-making process have different interests in the oceans. Hence, divergent views in making norms make it difficult to reach universally binding treaties on ocean governance. The difficulties in developing “good law” to promote ocean governance make it necessary for international lawyers to seek improvements in the international rule-making model. It is witnessed the protracted delay in the development of international legal norms, including the Plastics Convention and regulations on exploitation of mineral resources in the Area, that are considered necessary to advance ocean governance. While the role of non-state actors in ocean governance has been well discussed in past studies, how they can better participate in the international rule-making process, and in particular lead it, has still not been clarified in a concrete way (He and Mengda, 2020). Currently, while States remain the primary makers of international law, other actors, such as international organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and individuals, contribute in various ways to the development of the rules and principles of international law.

Among them, the uniqueness of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lies in the fact that it is not a purely intergovernmental mechanism or a non-governmental organization, but rather a mixture of States and other actors, both at the level of decision-making and at the level of action. As a combination of governments and civil society organizations, IUCN has assumed a significant role in developing the rules on global ocean governance, and it has become a global authority on marine protection and conservation (IUCN, a). IUCN has not only supported governments and international organizations with knowledge, tools and projects in the middle of this process, but has also led or led some of the efforts with success. In 2024, IUCN contributed to three unprecedented legal proceedings, including the oral hearing consultation initiated by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea(ITLOS). IUCN plays a vital role in influencing international policy and advocating for conservation at all levels by providing the scientific basis for informed decision-making and sustainable practices. IUCN represents both state and non-state members, demonstrating its unique role as a bridge between government and civil society (IUCN, 2024). The “IUCN pattern” may provide a new perspective of the improvement of the international rule-making process in the field of global ocean governance.

Based on an analysis of IUCN’s practices, this paper adopts a case study approach to seeking a new model of promoting international rule-making in ocean governance globally. Part II examines IUCN’s major practices in international rule-making on ocean governance, such as the nature-based solutions and marine biodiversity projects proposed or supported by the IUCN and the specific actions conducted. Part III discusses the IUCN’s contribution to international rule-making in ocean governance, particularly its transcendence of the state-centered legislative mode, and analyzes the internal and external limitations on IUCN’s participation in global ocean governance. In Part IV, we further explore a viable approach to strengthening the voice of non-state actors in international rule-making to reduce the negative effects of the state-centered legislative model.

2 IUCN’s impacts on international rule-making in ocean governance

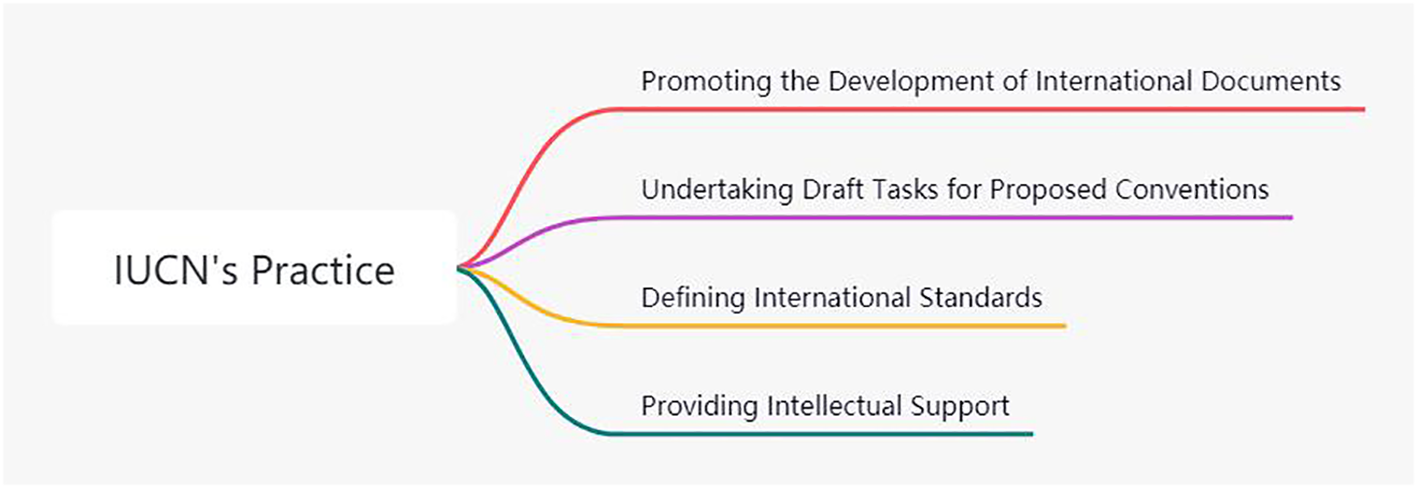

IUCN aims to ensure that marine ecosystems are restored and maintained, implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and support the Rio Conventions and many other marine biodiversity-related conventions. In the past decades, IUCN’s practices in international rule-making on ocean governance include setting ocean governance goals and specific directions for ocean protection, promoting the development or signing of international treaties, and hosting or assisting in the drafting of relevant draft conventions, etc. Its proposals and actions are of great importance to international rule-making on ocean governance (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

IUCN’s major practice concerning international rule-making.

2.1 IUCN’s major concerns on global ocean governance

IUCN aims to promote activities that protect and develop the marine and coastal environment, conserve marine and coastal species and ecosystems, and raise awareness of marine and coastal conservation issues and management. Meanwhile, it endeavor to providing knowledge, tools, strategies, as well as legal and technical support for global ocean governance through effective, equitable and systematic approaches.

2.1.1 Nature-based solutions and sustainable blue infrastructure

The IUCN pioneered the concept of nature-based solutions (NbS) 20 years ago and defined the current widely accepted definitions, standards and implementation options for NbS. IUCN attempts to integrate nature-based solutions into coastal resilience planning and investments for sustainable blue infrastructure financing. The fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly adopted a global definition of NbS, largely based on the IUCN definition of NbS, and provided an official reference for Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity and other international agreements. Following Lisbon Declaration, IUCN called on countries and all stakeholders to increase investment in and scale up the implementation of nature-based solutions as an important contribution to climate change mitigation, adaptation and disaster risk reduction. It has continued to support governments in mainstreaming NbS into national policies and strategic plans, and has assisted communities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in a wide range of implementation actions through funding, guidance and collaboration. In addition, the Alliance provides specialized training for stakeholders (IUCN, b). Examples of the support of NbS in the policy arena include: Explicit recognition of NbS in the 2020 Leaders’ Pledge for Nature (September 2020), Explicit recognition of NbS in the G7 Climate and Environment Ministers’ Meeting Communiqué (May 2021), Explicit recognition of NbS in the Joint G20 Energy-Climate Ministerial Communiqué (July 2021), UNEA recognition of standard definition of NbS and adoption (March 2022), and Incorporation of NbS in countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) (IUCN, 2022a).

2.1.2 BBNJ agreement negotiation

The IUCN is committed to establishing The Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, and provides information on issues including: (1) marine genetic resources, including benefit-sharing issues, in particular drawing on the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)’s experience with digital sequence information, to guide and direct the implementation of the BBNJ financial mechanism (2025); (2) measures such as area-based management tools, including marine protected areas; (3) environmental impact assessments:IUCN provides legal amendment recommendations for the formulation and revision of the environmental impact assessment clauses of the BBNJ Agreement (IUCN Briefing for BBNJ negotiators, Environmental Impact Assessment and Strategic Environmental Assessment, Part IV); (4) capacity building and transfer of marine technology; and (5) issues related to general principles, definitions, responsibilities and compensation, and institutional and financial arrangements to achieve the conservation of marine biodiversity. The IUCN calls for the protection of biodiversity on the high seas and for changing the current trajectory of marine decline and biodiversity loss. IUCN played an active role from the BBNJ Agreement’s negotiation to its adoption by providing legal insights, organizing seminars and publishing key materials. Currently, IUCN is preparing an explanatory guide to the BBNJ Agreement to assist parties, States and other relevant stakeholders understand, effectively participate in or implement the BBNJ Agreement. The guide is expected to be published in 2026.

2.1.3 Reducing marine plastic pollution

IUCN calls for the negotiation of an internationally legally binding instrument on plastic pollution and the implementation of measures to prevent and significantly reduce plastic discharges into the oceans; and encourages governments to incorporate nature-based solutions into their commitments under the Paris Agreement. In 2020, IUCN, together with the United Nations Environment Programme, developed National Guidance for Plastic Pollution Hotspotting and Shaping Action, which provides a methodological framework and practical tools applicable at different geographic scales to enable governments to work with key stakeholders to identify and implement appropriate interventions and tools to address hotspots as a priority. This is of key importance for the initiation and development of negotiations on a plastics convention. In 2022, the resumed fifth session of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2) decided to develop an internationally legally binding instrument on plastic pollution (including marine environmental pollution), which will be drafted by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee. During the negotiation process of the drafting of the instrument, IUCN provided legal comparative analysis for the draft and provided international law expertise to relevant member states, guiding member states to find common ground and thus develop a legally binding international instrument on plastic pollution. In 2025, IUCN and its World Commission on Environmental Law (WCEL) attended the 2025 Conference of the Parties to the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions (2025 BRS COP) as observers. IUCN declared its support for the international cooperation model of the BRS future plastic treaty, and will provide further legal and scientific expertise to the BRS Convention and its contracting parties (IUCN Statement: BRS COPs 2025 – Agenda Item on International Cooperation and Coordination).

2.1.4 Sustainable fisheries

The IUCN proposes development objectives for sustainable fisheries management that include collaborative programs to adopt ecologically sustainable practices in fisheries such as catch monitoring, the reduction of the impacts of fisheries on vulnerable marine ecosystems, the establishment of stakeholder networks to restore critical habitats, building partnerships with governments, communities, and stakeholders to improve capacity for sustainable fishing, and strengthening regulatory frameworks for fisheries. The IUCN has identified a number of ways in which countries can effectively construct marine protected areas.

2.1.5 Ocean deoxygenation and acidification

With regard to ocean deoxygenation, IUCN proposes the need to urgently mitigate global climate change and local nutrient pollution by introducing legislation to limit runoff, set specific targets and monitor. With regard to ocean acidification, IUCN suggests that ocean acidification should be addressed at the regional aspect in Latin America and the Caribbean, the Western Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean.

2.2 IUCN’s practice on international rule-making for global ocean governance

2.2.1 Promoting the development of international documents

The IUCN plays a crucial role in promoting the development of international documents that guide global conservation efforts (IUCN, c). The organization convenes its General Assembly every two to four years to discuss policy issues, approve related plans, make resolutions, and provide recommendations to influence marine legislation and policy at the regional, national, and global levels. Over the years, IUCN resolutions have played a key role in shaping much of the international legislation on marine conservation.

For instance, in 1954, the IUCN identified the importance of addressing the effects of pesticides on mammals, birds, and insects, leading to the adoption of the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal in 1989 and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in 2001. Influenced by these proposals, governments around the world have developed national legislation on pollution control, often with the advice of the IUCN Environmental Law Center.

The IUCN Congress in Warsaw in 1960 laid the groundwork for the development of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) provided expertise in the drafting of CITES, and in 1963, the IUCN adopted its first resolution on sea turtles, calling for a study of potential conservation measures. The plight of marine resources was raised at the 1972 IUCN Banff Conference, emphasizing the need for improved fisheries management, leading to the adoption of the IUCN Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) two decades later.

In 2000, the first comprehensive IUCN resolution on marine conservation was adopted in Amman, where IUCN members called for the ratification of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement and the creation of a representative network of marine protected areas (MPAs), including on the high seas MPAs. This resolution has been instrumental in the development of the CBD’s Aichi Target 11, which aims to conserve at least 10% of the world’s coastal and marine areas by 2020.

In 2024, the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution (INC-5) failed to finalize a legally binding international agreement to end plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, but advanced the text structure of the INC Chair’s Text 1 December for future negotiations. IUCN analyzed and elaborated on the text of each informal document to help member states understand the relationship with the other two informal documents and their mean in the context of international law obligations and the impacts of plastic pollution on the environment, biodiversity and human rights.

2.2.2 Undertaking draft tasks for proposed conventions

IUCN has a long tradition in international ocean governance legislation, including preparing relevant draft conventions or providing reference documents for proposed conventions. UNESCO’s 1992 Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage explicitly assigns IUCN a role as a provider of advice, cooperation, documentation services, etc. under the Convention. IUCN’s Environmental Law Committee assists countries in developing regulations and treaties, conducts research and publishes results, and was actively involved in the 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) negotiations. It prepared the first draft of the Treaty on Biological Diversity in 1986 and participated actively in the negotiations of the resulting Rio Convention on Biological Diversity.

IUCN also played an important role in promoting the creation of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which was adopted by Resolution 14 of the 7th IUCN General Assembly in 1963, and the IUCN Environmental Law Center drafted the first draft of the Convention, which was later signed by an agreement of 175 countries, which is an international agreement between governments, which aims to ensure that international trade in wildlife specimens does not threaten the survival of the species. Today, the CITES Secretariat is increasingly using the IUCN to implement the decisions and resolutions of the Parties.

The 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro added a new doctrinal dimension to the IUCN by articulating many of the soft law principles that will guide future legal and policy reform, including the principles of pollution prevention, inter-generational equity, polluter pays, and public participation, which guide international as well as national legal and policy reforms related to coastal and ocean management (Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Article 8(3), Article 13(7), Article 14(2)). In the absence of a unified general agreement on public international law to promote the integration of environment and development, the IUCN prepared a Draft International Convention on Environment and Development (Robinson, 1995), which was intended to provide a framework for the implementation of sustainability at all levels of society following the outcome of the Rio Conference. As a blueprint for consolidating and developing the international framework of existing legal principles on environment and development, the Draft International Convention on Environment and Development has been a “living document”, now in its fifth revised edition, serving as an authoritative reference and checklist for global legislators and other stakeholders in drafting new or updating existing policies and laws. It ensures the implementation of the principles and rules of international environmental law and development (2015).

As an intergovernmental observer organization, IUCN has played a vital role in the BBNJ agreement process, providing legal insights, hosting workshops and publishing important materials. IUCN was involved in the BBNJ agreement long before the formal IUCN negotiations began, laying the foundation for the formal negotiations that began in 2018. Since 2018, IUCN has been providing scientific and legal expertise to BBNJ negotiators to help build the capacity of the Intergovernmental Conferences (IGC). IUCN’s support has been vital in developing guidelines for Area-Based Management Tools (ABMTs), including Marine Protected Areas (IUCN, d).

2.2.3 Defining international standards

Based on extensive data sources and in-depth scientific research, the standards developed by the IUCN are increasingly being used by a number of national or international organizations, and the review of scientific and legal information on international and national laws and policies conducted by the IUCN has provided guidance to relevant national or international organizations on marine governance legislation.

In 1995, IUCN published a study identifying national and regional priorities for the conservation of marine biodiversity, and the Global Representative System of Marine Protected Areas (GRSMPA) divides existing protected areas into 18 biogeographic regions. The IUCN report identified 640 priority sites at the national level, of which 155 were selected as regional priority sites and 73 areas have been designated as protected areas. There are also criteria for naturalness, economic importance, social importance, scientific importance, international or national significance, and practicality/feasibility. These guidelines have been utilized by the International Maritime Organization in the development of guidelines for determining safety standards at sea and under the Baltic Sea Convention.

The IUCN’s global review of literature and legal information on international and national laws and policies also gives direction to inform the development or revision of laws in various countries and regions. The Legal Framework for Mangrove Governance, Conservation and Utilization: a Summary of Assessment, published in 2018, assesses mangrove-related legal instruments in India, Kenya and Mexico, and provides an in-depth assessment of Costa Rica, Madagascar and Vietnam on the effectiveness of mangrove-related laws; and an analysis of the evolving legal and policy architecture in the Arctic, providing a chronology of legal-related events and materials covering a wide range of issues, such as environmental protection, indigenous peoples’ rights, shipping and fisheries, and the delimitation of maritime boundaries.

2.2.4 Providing intellectual support

IUCN provides its members with sound ocean expertise and policy advice to advance ocean conservation and sustainable development. In the areas of marine biodiversity, seamount protection and deep-sea mining, marine plastic pollution, sustainable fisheries management, and other areas of marine governance, IUCN collaborates with national authorities to develop project programs and promote research on marine governance legislation.

In 2012, IUCN worked with the Lebanese Ministry of Environment on the marine protected area strategy to conduct environmental impact assessments of projects in Lebanon’s marine and coastal areas, mainstreaming biodiversity conservation into its environmental impact assessment process. In 2019, IUCN, with support from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, launched the Plastic Waste Free Islands (PWFI) project as part of the Turning Off the Plastic Tap program in Fiji, Vanuatu and Samoa in Oceania and in Antigua and Barbuda, St. Lucia and St. Lucia in the Caribbean. IUCN’s ocean governance research projects in various countries have contributed to the development of national ocean governance legislative research projects and set the direction for ocean governance in member countries.

IUCN’s reports are often landmarks, such as the 2018 report, Ocean Connections: Warming Oceans, Increasing Risks in Change, and the 2021 report, Addressing Ocean Risks. In the two reports, IUCN not only defines for the first time what ocean risks are, but also tracks a series of major changes already occurring in the ocean and their impacts. On this basis, the IUCN calls for a more strategic approach to ocean risk assessment and management at the national level.

3 The advantages and limitations of the “IUCN pattern”

3.1 The advantages of the “IUCN pattern”

There is still a lack of applicable rules in ocean governance while the existence of conflicting interests between ocean powers and other countries often hinders an efficient international rule-making process. In fact, the situation is often visible in the traditional international rule-making model where the major powers dominate (2023). In this context, the role of non-state actors should be emphasized in order to reduce the negative impact influence of political considerations and interest orientation (Pauwelyn et al., 2012). IUCN as a combination of intergovernmental international organizations and non-governmental international organizations of non-state actors, has a unique advantage, and IUCN’s involvement is conducive to the development of international rule-making in ocean governance in a more just and reasonable direction, the peaceful use of the ocean, as well as the construction of a new pattern of global ocean governance (IUCN, 2017).

3.1.1 Objectivity

IUCN is an official observer to the United Nations, with more than 1,400 organizations in more than 160 countries worldwide and links to over 18,000 experts, which allows it to consider challenges and solutions in ocean governance in a comprehensive manner. IUCN’s concerns and goal setting for ocean governance are practical. In the past, most of its concerns, including incidental catch issues, deep-sea mining issues, radioactive waste disposal, and ship oil spills, have proven to be significant. IUCN’s extensive network allows it to maximize the consideration of perspectives from different geographic regions and different laws of the world.

At the same time, various stakeholders, such as governments, NGOs, scientists, businesses, local communities, and indigenous peoples’ organizations, can use IUCN’s objective and neutral platform to develop and implement solutions to the challenges of ocean issues and thus achieve sustainable ocean development. In 2021, IUCN approved the Nature 2030 plan. By developing a digital platform, IUCN members and other institutions will be able to record in spatial form their potential contributions to IUCN plans and the Global Biodiversity Framework, the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals. The results can support planning, reporting, communication and resource mobilization within the organizations and further afield, help develop action plans to fill gaps at the national or regional level, and be objective and scientific. Indeed, IUCN’s work is very much on the ground. For example, the 2015 West Africa Coastal Observatory (WACO) organization (West Africa Coastal Areas Management Program) for the West Africa Coastal Zone Assessment (WACA) had a deep involvement of IUCN. In response to the changing conditions of West African coastal systems, IUCN collects and updates information on coastal features, makes recommendations on priority actions and regional plans, and builds the region’s capacity to prevent and respond to coastal hazards (European Commission, MRAG Ltd, 2018).

3.1.2 Expertise

Not all countries have sufficient interest in and knowledge of ocean governance, limited by the resources they can devote to it. In many cases, ocean information and knowledge of IUCN far exceeds that of state actors. It means that IUCN has a better professional background in international rule-making in ocean governance than States, allowing it to make more practical and effective proposals. The IUCN’s technical guidelines of legislation already constitute a useful reference for its members’ domestic legislation. Through these guidelines, IUCN members are expected to overcome the lagging effects of international legislation and improve their adaptability to the development of ocean challenges.

Since 1980, IUCN has published the Guide to Protected Areas Legislation, linking best management practices to the laws that govern protected areas and the legal frameworks that establish and manage them, providing practical and up-to-date guidance for legal drafters, protected area professionals, policy makers, governmental and non-governmental stakeholders, and members of the academic community who are interested in strengthening protected area legislation. International Policy and Governance Options for Ocean Acidification, published in 2014, notes that existing international treaties are inadequate to address the ecological threat of ocean acidification, and that a review of international legal instruments such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and the Convention on Biological Diversity, makes clear that ocean acidification has not been explicitly included in the mandate of any international treaty. The Legislative Guide on Protected Areas, published in 2016, suggests the need to give special consideration in the legal framework for protected areas to the need to integrate coastal and marine protected areas into land use and marine spatial planning and so on. Many of the above documents have become part of international treaties and have been accepted by a significant number of countries as part of their domestic law.

Additionally, the standards and lists provided by the IUCN have significant impacts. For instance, the Red List of Threatened Species, created by the IUCN in 1964, is an inventory of species and their status, an important indicator of the health of the world’s biodiversity, promoting action for biodiversity conservation and policy change, and essential for the conservation of marine natural resources. To date, it is used by government agencies, wildlife departments, non-governmental organizations, natural re-source planners, educational organizations, students, and the business community (Iucnredlist).

In 2023, the UN General Assembly requested the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to issue an advisory opinion on the obligations of States with regards to climate change. ICJ approved IUCN’s request to participate in the case. In 2024, IUCN submitted a written response to ICJ and participated in relevant oral hearings. In 2025, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea issued an advisory opinion, pointing out that States have a legal obligation to assist developing countries in dealing with the pollution of the marine environment caused by greenhouse gas emissions. The consultation process involved the full participation of IUCN experts with expertise on a range of topics related to climate and biodiversity (IUCNe).

3.1.3 Vision

Related to its expertise, as mentioned earlier, IUCN is able to provide anticipatory policy and technical advice to negotiators and key stakeholders when engaging in international legislative processes. IUCN has identified timely issues such as ocean warming, ocean acidification and ocean hypoxia, overfishing and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, and has pointed to the urgent need for stronger legal and policy frameworks in these areas and their collaborative implementation. IUCN has explained innovations in ocean management and shared relevant scientific information with international diplomats involved in the negotiation process of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Some of this has been incorporated into Part VII of UNCLOS (Robinson, 2005).

IUCN has also been prescient in its advocacy for sustainable development of the oceans. Since the beginning of the 21st century, IUCN has urged member states to actively participate in IMO discussions to consider updating legislation to stop marine pollution caused by ship discharges of wastewater, including amending existing legislation on marine pollution and updating the list of pollutant types, which has become an important issue at IMO in recent years (IUCN World Conservation Congress).

3.1.4 Providing a forum rather than a boxing ring

On the one hand, the IUCN, as a stable institution, provides a forum for constant negotiations. States can exchange views on emerging situations, thus providing new opportunities for international lawmaking. In past international negotiations led by the IUCN, it allowed negotiators to continue to interact beyond a single round of negotiations, to propose useful areas or topics that would facilitate treaty-making; to mobilize a wide range of potential collaborators; and to provide a more mature framework for negotiations based on States can meet in the IUCN as a forum and agree on a common acceptable approach to common issues. Indeed, the existence of a permanent international organization such as the IUCN means that delegates can build mutual trust and respect through long-term cooperation and discussion, avoiding as much as the possible direct confrontation between sovereign states over differences of opinion on common issues. In this sense, the IUCN is more like a facilitator, avoiding, through flexibility, excessive tensions between countries over specific topics to the extent that it abstains from participation.

On the other hand, it should be noted that much of the mistrust arises because of imbalances in the ability of the parties to access information. For this, the information provided by the IUCN based on extensive assessments and reviews is supported by a range of science and data, which avoids disagreements between countries due to inconsistent perceptions. Besides, IUCN publishes assessment guides, assessment reports, and more, which can also help determine better directions for legislative research, yielding more benefits in the long run while meeting marine conservation and sustainable development needs.

3.2 The Limitations of the IUCN to international rule-making for global ocean governance

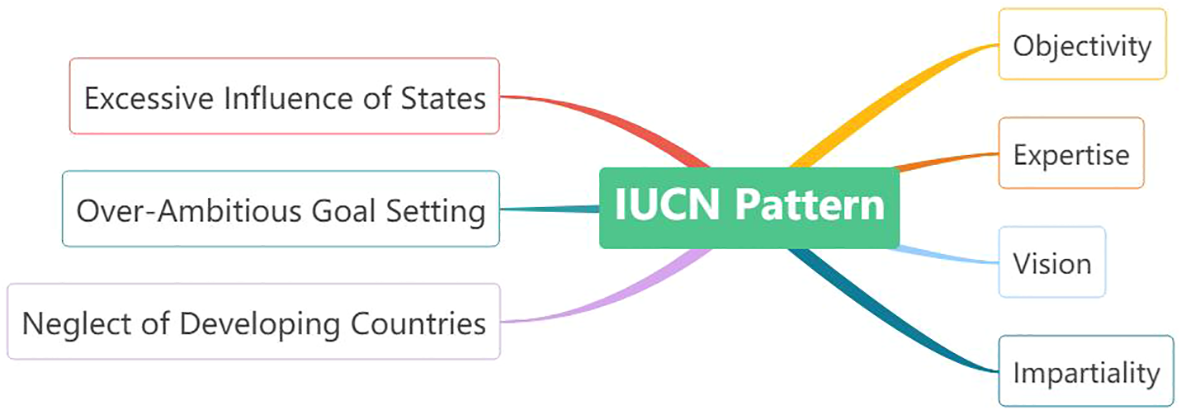

Despite the advantages of the “IUCN pattern”, IUCN’s decisions and actions are still difficult to avoid the dilemma of intergovernmental domination. At the same time, IUCN’s funders mainly come from European countries, the United States, Japan and other major developed countries, and most of the other funders or enterprises also come from developed countries. Under such circumstances, IUCN is inevitably “biased” and sometimes fails to fully consider the positions of countries outside Europe, especially developing countries (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

The advantages and limitations of the “IUCN Pattern”.

3.2.1 Excessive influence of states

IUCN resolutions have had a significant impact on the law-making of global ocean governance, with many elements of the resolutions even contributing to the development of international treaties on the oceans. As mentioned earlier, this is closely related to their NGO-supported mechanisms and sources of information. However, IUCN resolutions have inevitably suffered from intergovernmental dominance due to the “bicameral” nature of their rules (the votes of states and government agencies are counted separately from the votes of NGOs in the General Assembly). Specifically, the founding members of the IUCN structured the IUCN’s statutes to create a new method of linking state and NGO members (IUCN, 2022b), based on the broad provisions of Article 60 of the Swiss Civil Code, and an amendment to the IUCN’s statutes adopted in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1956 divided the General Assembly vote into state and NGO votes. The IUCN Council decided that it had the power to decide on NGO membership.

IUCN is unique among international organizations in that it was created by sovereign states and has a membership that includes governments, international NGOs and national NGOs, as well as non-voting affiliate members. According to the IUCN Statutes, IUCN membership is divided into four categories: Category A members include states, government agencies and local governments; political and/or economic integration organizations; Category B includes national NGOs and international NGOs; Category C members include indigenous peoples’ organizations; and Category D includes affiliated members (affiliated members are not government agencies, national and international NGOs in categories A, B or C). IUCN Only members in categories A, B and C have voting rights at the General Assembly. votes of members in category B and votes of members in category C, i.e. national NGOs, international NGOs, and indigenous peoples’ organizations, are combined. Unless the statutes provide otherwise, decisions of the Assembly are adopted by a simple majority vote of the members in category A, as well as in categories B and C. IUCN’s decision-making process at its Assembly is conducted through a bicameral voting process. Countries and government agencies, etc. in category A members vote in one chamber, while NGOs in categories B and C members vote in the other. According to the IUCN statutes, each member state has three votes at the General Assembly among government members, one of which is exercised collectively by members of the state’s government agencies; among NGO members, national NGO members have one vote; and international NGO members have two votes.

This weighted vote provided for in the IUCN Constitution and the fact that a majority of countries must vote in favor of the decisions adopted by the Assembly, there is an inevitable nature of Assembly resolutions remaining government-driven in the way they are counted, and therefore IUCN resolutions are subject to intergovernmental domination. the intergovernmental nature of the IUCN makes this form of law-making inevitably subject to political considerations, and Class A members, i.e., states, government agencies and Intergovernmental organizations such as A-class members, i.e., countries, government agencies and local governments, have a greater say in the rules of procedure of IUCN. This has led to IUCN resolutions sometimes being diverted from the scientific data, technical or project assessments and analyses on which they rely by the excessive in-fluence of States.

3.2.2 Over-ambitious goal setting

IUCN establishes the role of scientific experts organized into committees whose mandates and chairs are determined by the General Assembly. IUCN’s governance structure is designed to make effective use of public and private resources with the goal of influencing, encouraging and assisting societies around the world to protect the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. In general, non-state actors, particularly those known as transnational advocacy networks, social movements and NGOs, primarily aim to seek access to international governmental bodies and legislative processes to advance their own agendas. IUCN, too, is committed to promoting its purposes and values in law-making processes, but it sometimes sets goals that are too ambitious to the point of being unrealistic.

For example, the IUCN has continued to advance its agenda on marine environ-mental protection. On the issue of deep-sea mining, on March 6, 2023, the IUCN Di-rector-General issued an open letter to the members of the International Seabed Authority on Deep Sea Mining, urging the members of the International Seabed Authority to insist on a global moratorium on seabed mining in accordance with the decision taken by the IUCN. The IUCN, as an international intergovernmental organization and an international non-governmental organization, publicly called on the International Seabed Authority, in accordance with the IUCN Assembly resolution’s objective of calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, which is contrary to the position of most countries, especially developing countries.

In fact, the International Seabed Authority was established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea treaty to ensure the protection of the marine environment while regulating mining activities in international waters. It has established regulations governing exploration activities, including provisions relating to environ-mental protection. Over the past two decades, the International Seabed Authority has issued exploration contracts to state-sponsored enterprises, government agencies and private companies (UN, 2017). Although the issue of deep-sea mining is still controversial internationally, most developing countries still look forward to the direct benefits and benefit-sharing that those seabed minerals may bring. the IUCN’s goal of calling for an outright moratorium on deep-sea mining without considering whether it is fair for developing countries, solely from the perspective of environmental protection and without fully considering the primary interests of States, seems too radical.

3.2.3 Neglect of the positions and interests of developing countries

Similar to most organizations that rely on external funding, IUCN is inevitably influenced by the views of its major funders. In many cases, IUCN conducts project research that is primarily supported by resources and funding from its partners, mainly the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the French government and the French Development Agency, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, and the U.S. Department of State, among others. IUCN’s research on ocean governance is to some extent limited by the direction set by the funders and cannot be fully independent in its research program based on the perspective of the most realistic needs of ocean governance.

For example, with support from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, IUCN’s Plastic Waste Free Islands project focuses on six islands in the Pacific and Caribbean regions: Fiji, Samoa, Vanuatu, Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, and St. Lucia. Three new economic briefs in the Caribbean demonstrate the impact of plastic pollution on the marine environment, livelihoods, and the economic and social aspects of island life. However, while these research programs selectively showcase the country’s most vulnerable to the impacts of marine plastics, it is questionable whether they reflect the picture of the majority of countries on the issue. These project grants have clearly helped to translate into “scientific conclusions” that support the funder’s position and are sometimes not entirely factual.

4 Towards a more efficient and democratic international rule-making pattern

Ocean governance issues challenge how international rule-making can stimulate good regional and international cooperation, by promoting the access to information, mutual understanding and fairness necessary for cooperation. The current pattern of international rule-making in ocean governance is often criticized for its difficulty in striking a balance between efficiency and democracy. In light, the “IUCN pattern” may provide a more efficient and equitable model for international rule-making in ocean governance.

4.1 Reinforcing the voice of non-governmental subjects

The oceans are divided into different regions and the diverse and fragmented nature of ocean governance calls for global cooperation, while the regional aspects of ocean governance and the issue of government dominance limit the potential for relevant measures. States and international organizations can only act within their respective jurisdictions and mandates. Overcoming this obstacle requires enhanced cooperation and coordination between states, between states and international/regional organizations, and between international/regional organizations, and industry and other private players need to play a role in this setup (Hilborn and Ovando, 2014).

The independence and pro bono nature of NGOs allow them to move away from a self-interest-based position to a degree that places the good governance of the global ocean at the core of their activities. This positioning allows NGOs to be seen as a neutral party in the process of governance policy formation and “international rule-making”, and makes them qualified monitors of the ocean governance activities of states and international organizations. A large number of NGO initiatives helps to fill the gaps in the governance capacity of national governments. By working in different areas and issues, NGOs are effectively contributing to global ocean governance, not only by proposing new ideas and concepts, but also by promoting their implementation, preventing global ocean governance from stagnating on slogans.

At the same time, ocean governance is facing challenges from many aspects, and a series of unreasonable and unsustainable behaviors such as marine pollution, overfishing, misuse and indiscriminate exploitation of resources have caused tremendous pressure on governance. In the face of the ocean crisis, no country or individual can do it alone. To ensure the sustainable development of the ocean and human society, it is necessary that civil society can work together with governments to carry out the cause of ocean governance. More importantly, the process of legislative consultation needs to ensure broader participation and raise the hopes of achieving an international treaty or agreement. Consultations should be conducted on a global scale, taking into account the perspectives of different legal systems. Conducting legislative assessments, collecting ocean-related data, organizing industry experts for technical analysis, strengthening the voting rights of non-governmental subjects, and organizing negotiations will help promote the formation of international treaties or other international legal instruments and strengthen coordination and cooperation among countries and regions.

4.2 Expert organization-led negotiation mechanism

On the one hand, despite the post-World War II globalization process that has driven the global South, the level of ocean governance in the vast majority of the world’s coastal regions is far from that of the countries of the North in North America and Europe. Some members of the international community, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa and small island development states, have weak international rule-making capacity to participate effectively in ocean governance because they have neither the necessary intellectual, resource, nor financial resources. At the same time, it is impractical to require them to adopt ocean protection and conservation measures under the same strict rules and standards as major countries, which leaves them in a weak position in international consultations. In light of this, the current state-centric, and especially dominant state-led, model of international rule-making is undermining the interests of all members of the international community to participate fairly and equitably, leaving the rule of law effectively in the hands of some states. Moreover, the domination of the negotiation process by the major powers has excluded NGOs and other actors who fear that their positions will not be consistent with their own.

IUCN’s practice reminds us that interstate negotiations do not necessarily have to be led by states. Instead, a specialized body with professional competence, whether inter-governmental or non-governmental in nature, as the leader of the negotiation mechanism is a viable model. In this case, most actors, especially those organizations with strong expertise but often excluded from the legislative process, are given a fuller opportunity to express their views and to present evidence and lobby for them. In this context, information transparency and sharing allow the dominance of the major powers to be diminished, while the mainstream views of the international community can be more clearly clarified and translated into normative content.

On the other hand, while the ocean governance crisis poses challenges for all countries, the risks are very different for each country. For example, Australia spends hundreds of millions of dollars each year monitoring and enforcing Southern Ocean fisheries through high seas vessels, satellite surveillance, overpasses, and other advanced military technology, but this is clearly impossible for most small and medium-sized countries to accomplish. Resource use needs, the urgency of the coastal zone and juris-dictional ocean protection, geographic location, or the influence of political and economic ties may drive governments to negotiate with too much regard for national considerations at the expense of the common interests of the international community. In contrast, specialized institutions of ocean governance serve only the public interest without over-considering these domestic political factors, making them more qualified leaders in the international rule-making process.

In addition, the use of specialized sub-sectoral bodies to lead regional ocean governance, with the targeted implementation of ocean governance measures through the leadership of specialized bodies for different areas such as fisheries and aquaculture, high seas, marine ecosystems, marine species, oceans and climate change, plastics and other pollution, has helped to advance the development of specialized ocean governance. Within the past decade or so, IUCN has analyzed and studied Cambodia’s policy and Myanmar’s strategic development, and assisted them in developing and implementing a regional cooperation plan for environmental management of the East Asian Seas, effectively promoting marine spatial planning, achieving sustainable development of marine and coastal activities such as tourism and recreation, fisheries, and aquaculture, and promoting regional cooperative arrangements and regional cooperation agreements on marine governance.

4.3 Translating scientific information into legislative guidance

Considering the history of the development of international rules, non-binding norms are not useless. On the contrary, they may result in more detailed national laws and provide a basis for regional agreements on specific commitments. In the past, the National Biodiversity Action Plans, National Autonomous Contribution Plans (NDCs), Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries, National Adaptation Plans, Climate Change Gender Action Plans, etc., proposed by the IUCN have been accepted and used by some countries, and have further generated new international agreements. These non-binding guidelines, which are not binding per se, are more moderate and therefore less likely to provoke strong opposition from states and are easily adopted in an incremental manner.

In terms of applying legal tools to achieve the goals of ocean governance, binding legal commitments often serve only to establish a framework to define general legal obligations. Instead, these non-binding guidelines can play an important role in developing detailed, practical guidance to achieve stated goals: at the national level, these “guidelines” can facilitate the establishment of national norms for common action; at the international level, it is more difficult to agree on agreements that apply to different geographic settings and socioeconomic circumstances, and Non-binding guidelines provide a useful alternative. Non-binding norms can be formally recognized and adhered to at the national level through domestic legislation, while non-binding norms, if applied and adapted by several neighboring countries, can form the basis of a unified regional approach. Once recognized through regional and global conventions, they can serve as rules of general international law governing the activities of states.

Therefore, actors in global ocean governance, whether States, international organizations, or non-governmental organizations, are encouraged to translate the scientific information at their disposal into readable and observable legislative guidelines to contribute to international legislation on ocean governance. Actors should not be satisfied with collecting facts, but should realize the guidance of scientific information for inter-national law-making by further integrating the competencies and expertise of different institutions.

4.4 Taking the broadest consensus into account

It is necessary and meaningful to consider the broadest consensus in the international rule-making of global ocean governance because the oceans are a shared resource that affects every nation and individual on the planet. Global ocean governance refers to the management and regulation of activities in the oceans, including issues such as marine pollution, marine biodiversity, fisheries management, and shipping regulation. In order to effectively manage and regulate these activities, it is important to have a comprehensive and widely accepted legal framework that reflects the interests and concerns of all stakeholders. This requires broad international cooperation and consensus-building, as well as a commitment to the principles of equity, fairness, and sustainable development.

Moreover, considering the broadest consensus in international rule-making for global ocean governance ensures that the legal framework is transparent, inclusive, and participatory, and that it reflects the diverse perspectives and interests of all stakeholders. This helps to build trust and cooperation among nations and promotes the peaceful and sustainable use of the oceans. The oceans are a complex and interconnected system that requires a holistic and integrated approach to governance. The broadest consensus promotes the development of a comprehensive legal framework that reflects this complexity and promotes the sustainable use and conservation of the oceans for present and future generations.

In summary, considering the broadest consensus in international rule-making for global ocean governance is necessary and meaningful because it promotes transparency, inclusivity, and cooperation among nations, and ensures a comprehensive and integrated approach to the management and regulation of activities in the oceans. Whether in an international rule-making process led by a state, an international organization, or an NGO, it is necessary to avoid the interests of a single or small number of actors to the detriment of the collective interests of the international community, and effective oversight should be guaranteed to achieve this goal.

5 Conclusion

International rule-making is a crucial means by which to promote global ocean governance, as it helps regulate the actors who can potentially contribute to good governance. However, the state-centric model of international rule-making has faced significant challenges in recent decades. On the one hand, disagreements among states due to differing interests and uneven access to information have caused the rule-making process to fall behind, to the detriment of the international community’s common interests. On the other hand, developing countries’ voices have often struggled to be heard and incorporated into legal norms, placing them at a legal disadvantage. As such, there is a need to refine the international rule-making approach in ocean governance, and in this regard, IUCN’s practice is inspiring. This paper explores the specific practices of IUCN and focuses on analyzing the contribution of the IUCN model, providing a theoretical basis for the development research of ocean governance and the formulation of relevant rules.

IUCN, a mixed governmental and non-governmental organization, has played an important role in promoting global ocean governance for a long time. It has advanced discussions on topics such as nature-based solutions, sustainable blue infrastructure, the BBNJ Agreement, and the reduction of marine plastic pollution, and has contributed to the development of international law rules relating to these issues. IUCN has not only been deeply involved in developing international documents and has even drafted some proposed treaties, but it has also created a series of compelling standards based on scientific evidence, which have been widely accepted, and provided intellectual support to the negotiation process on ocean governance.

The strength of the IUCN model lies in its objectivity based on scientific implementation and the expertise and vision gained from years of work in ocean governance. IUCN provides a forum for countries to communicate and exchange views regularly and constantly under its moderation, effectively alleviating tensions between countries due to differences of opinion and perceptions. However, IUCN’s work can still be overly influenced by countries, particularly major ones, due to its institutional design. Additionally, in some instances, IUCN has set overly ambitious goals and overlooked the positions and interests of the Global South.

Nonetheless, IUCN’s practice suggests that state-centered international rule-making is not unchangeable or irreplaceable. On the contrary, the involvement of non-governmental subjects should be strengthened in constructing rules for global ocean governance. Professional organizations are encouraged to become more involved in and even lead the international rule-making process in various fields, shifting the focus from pure scientific research to rule development and providing essential legislative guidance to the international community. Additionally, the neutrality and objectivity of the pro-posed international rule-making mechanism should be guaranteed to incorporate the broadest possible consensus and ensure the interests of the most significant number of countries, rather than reflecting only those of a few major powers.

Statements

Author contributions

XC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. YZ: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. LZ: Writing – original draft, Resources, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by National Key R&D Program of China, grant number 2023YFC2808802; Global Deep Sea Typical Habitat Discovery and Conservation Program 102121221580000009023.

Conflict of interest

Author YZ was employed by Greenfield Law Firm.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

(2025). IUCN BBNJ Policy Brief, Digital Sequence Information (DSI) as a Means of Financing Under the BBNJ Agreement.

2

(2015). IUCN Draft International Covenant on Environment and Development.

3

(2023). Bec Strating, A jurisdiction over the high seas (Australia: Lowy institute). Available online at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/jurisdiction-over-high-seas.

4

IUCN Briefing for BBNJ negotiators, Environmental Impact Assessment and Strategic Environmental Assessment, Part IV.

5

IUCN Statement: BRS COPs 2025 – Agenda Item on International Cooperation and Coordination. Available online at: https://iucn.org/resources/information-brief/iucn-statement-brs-cops-2025-agenda-item-international-cooperation-and (Accessed May 11, 2025).

6

Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Article 8(3), Article 13(7), Article 14(2). (1972)

7

West Africa Coastal Areas Management Program. Available online at: https://www.iucn.org/news/secretariat/201701/german-resolution-reaffirms-iucn’s-position-international-stage (Accessed December 28, 2024).

8

IUCN World Conservation Congress. Available online at: https://iucncongress2020.org/motion/032 (Accessed June 7, 2025).

9

Blythe J. L. Armitage D. Bennett N. J. Silver J. J. Song A. M. The politics of ocean governance transformations.

10

Churchill R. R. Lowe A. V. (1999). The law of the sea, 3rd ed (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

11

European Commission International ocean governance. Available online at: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/ocean/international-ocean-governance_en (Accessed June 7, 2025).

12

European Commission, MRAG Ltd (2018). Final Report: International Oceans Governance - Scientific Support (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union).

13

He J. Mengda H. (2020). Global ocean governance and the BBNJ agreement: practical difficulties, legal construction and China’s path. J. China Univ. Geosci. (Social Sci. Edition)20 (3), p47-60. doi: 10.16493/j.cnki.42-1627/c.2020.03.005

14

Hilborn R. Ovando D. (2014). Reflections on the success of traditional fisheries management. ICES J. Mar. Sci.71, 1040–1046. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsu034

15

IUCN Setting priorities. Available online at: https://www.iucn.org/our-work/informing-policy/setting-conservation-priorities (Accessed June 7, 2025).

16

IUCN Nature-based Solutions. Available online at: https://iucn.org/our-work/nature-based-solutions (Accessed May 11, 2025).

17

IUCN . The impact of IUCN resolutions on international conservation efforts: an overview, IUCN-2018-011.

18

IUCN The Role of IUCN in the BBNJ Agreement: A Pathway to Ocean Conservation. Available online at: https://iucn.org/story/202503/role-iucn-bbnj-agreement-pathway-ocean-conservation (Accessed May12, 2025).

19

IUCN EXPLAINER: The International Court of Justice considers climate change. Available online at: https://iucn.org/story/202412/explainer-international-court-justice-considers-climate-change (Accessed May 12, 2025).

20

IUCN (2017). German resolution reaffirms IUCN’s position on the international stage. Available online at: https://www.iucn.org/news/secretariat/201701/german-resolution-reaffirms-iucn%E2%80%99s-position-international-stage (Accessed June 7, 2025).

21

IUCN (2022a). Nature-based Solutions in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework Targets.

22

IUCN (2022b). Statutes, including Rules of Procedure of the World Conservation Congress, and Regulations, revised on 22 October 1996 and last amended on 10 September 2021 (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN).

23

IUCN (2024). International Union for Conservation of Nature annual report.

24

Iucnredlist Background & History. Available online at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/about/background-history (Accessed June 7 2025).

25

Pauwelyn J. Wessel R. A. Wouters J. (2012). Informal International Lawmaking (Ox-ford: Oxford University Press).

26

Robinson N. A. (1995). Colloquium: The Rio Environmental Law Treaties IUCN’s Proposed Covenant on Environment & De-velopment, Pace Environmental Law Review, Vol. 13.

27

Robinson N. A. (2005). IUCN as Catalyst for a Law of the Biosphere: Acting Globally and Locally Vol. 35 (Australia: Environmental Law, Spring), 249–310.

28

UN (2017). The International Seabed Authority and Deep Seabed Mining Vol. Volume LIV (Australia: Our Ocean, Our World). Available online at: https://www.un.org/zh/chronicle/article/20657.

29

van Doorn E. Friedland R. Jenisch U. Kronfeld-Goharani U. Lutter S. Ott K. et al . (2015). World Ocean Review 2015: living with the oceans 4. Sustainable use of our oceans - making ideas work (Hamburg, Germany: Maribus, Future Ocean, IOI International Ocean Institute, mare), 76.

Summary

Keywords

global ocean governance, international rule-making, SDG 14, non-state actors, International Union for Conservation of Nature

Citation

Chen X, Zhong Y and Zhang L (2025) A new horizon for rule-making in global ocean governance? Reflections on the IUCN’s contributions and limitations. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1615329. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1615329

Received

21 April 2025

Accepted

24 June 2025

Published

10 July 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Qi Xu, Jinan University, China

Reviewed by

Hao Huijuan, Ningbo University, China

Yayezi Hao, Wuhan University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Chen, Zhong and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xidi Chen, cxd1996810@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.