Abstract

The gastrointestinal (GI) microbiome plays a critical role in animal health and fitness, yet it remains understudied in many species—particularly those inhabiting freshwater environments affected by anthropogenic activity. This study investigates the gut microbiomes of two benthic fish species, Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) and suckerfish (Catostomus spp.), collected upstream and downstream of a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluent outflow into the East Gallatin River in southwestern Montana. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbiome diversity in the fish GI tract was assessed using 16S and 18S rRNA gene sequencing, respectively, from samples collected in the summer and fall of 2022 and 2023. While alpha diversity only had insignificant and small shifts across samples, beta diversity (taxonomic composition) differed significantly across sites and collection dates. Notably, the composition of eukaryotic sequences shifted markedly from upstream to downstream locations, suggesting that WWTP effluents may influence both prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbial communities. By establishing baseline GI microbiome characteristics for these species, this study provides important insights into the potential ecological effects of wastewater discharge on freshwater systems and supports conservation efforts aimed at mitigating pollutant impacts.

Scope statement

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are designed to effectively remove waste solids, nutrients, and organic matter before they redistribute the water back into the environment. However, WWTPs are not designed to remove chemicals of emerging concern (CECs) such as pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, fertilizers, and microplastics. Microbes can interact with CECs, and it is unknown how CECs might affect the microbiome of aquatic animals in the environment where WWTP effluent is released. In Montana, the baseline microbiome of common fishes is also under explored. This work accomplishes two main goals, 1) establishing a baseline microbiome for two fishes, the Rocky Mountain Sculpin and sucker fishes, so that we might be able to 2) identify potential changes in the fish microbiomes possibly associated with the WWTP effluent and its CECs.

Introduction

Human activity unfailingly involves environmental release of contaminants, such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products, pesticides, and other chemicals of emerging concern (CECs). Chemicals of emerging concern can originate from industrial, domestic, agricultural, and pharmaceutical sources, entering the environment through direct disposal, agricultural runoff or wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluent discharge (Zhou et al., 2009; Comber et al., 2018). Wastewater treatment plants effectively remove suspended solids, organic matter, and nutrients from wastewater (Obaideen et al., 2022) but are often ineffective at removing CECs and thereby result in direct CEC discharge into aquatic ecosystems (Vasilachi et al., 2021; Golovko et al., 2021; Pedrotti et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021; Matesun et al., 2024). Though CECs are not regularly monitored, studies have reported the global presence of these contaminants in surface and groundwater, particularly in areas impacted by WWTP discharge (López-Pacheco et al., 2019; Bishop et al., 2020). For example, traces of oxybenzone, pharmaceuticals, and various industrial and commercial compounds, such as heavy metals and microplastics, have been detected in seawater impacted by WWTP effluent in southern California (Vidal-Dorsch et al., 2012). These CECs are not just found in southern California; a nationwide study of 29 WWTPs across the United States detected 121 contaminants such as pharmaceuticals, anthropogenic waste indicators, caffeine, perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, and inorganic compounds in the WWTP effluent (Glassmeyer et al., 2017). As WWTPs continue to be major pathways introducing CECs into aquatic ecosystems, scientific studies have increasingly focused on understanding the ecological impacts of chronic exposure to these compounds.

Even trace CECs concentrations can pose risks to the health of aquatic environments, though effects are species and context dependent (López-Pacheco et al., 2019; Häder et al., 2020; Kasonga et al., 2021; Thanigaivel et al., 2023). Ecotoxicology studies demonstrate that CEC exposure causes cellular toxicity, genotoxicity, and hormonal disruptions in aquatic organisms, impairing reproductive success and altering sex ratios (King et al., 2012; Bukola et al., 2015; López-Pacheco et al., 2019; Nilsen et al., 2019; Pastorino and Ginebreda, 2021). CEC may also bioaccumulate in food webs, posing risks to aquatic life and human populations reliant on these ecosystems. For instance, studies on freshwater mussels found CECs present in water, sediment, and tissues, revealing widespread contamination across habitats and life stages, with potential implications for imperiled species like the freshwater mussel (Woolnough et al., 2020). Similarly, macroinvertebrates in a UK estuary exhibited higher body burdens of CEC compared to other species (Miller et al., 2021). In the Mediterranean Sea, bio-indicator species like the Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and the catshark (Scyliorhinus canicular) showed increased bioaccumulation of microplastics and pollutants, exacerbating contamination impacts on aquatic life (Impellitteri et al., 2023). In other fish, chronic pharmaceutical exposure contributed to behavioral and physiological effects, such as increased aggression, metabolic stress, and thyroid dysfunction (Bukola et al., 2015; Muir et al., 2017; Grabicova et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2020; Hubená et al., 2021; Gould et al., 2021). Endocrine-disrupting chemicals further disrupt reproduction, increase cancer risks, and cause thyroid issues in both wildlife and humans (Biswas et al., 2021).

CECs can also disrupt microbiomes, potentially compromising ecosystems or host health and leading to broader ecological consequences throughout aquatic ecosystems (Weersma et al., 2020; Restivo et al., 2021; Pinto et al., 2022; Dai et al., 2023). CECs introduced by WWTP effluents can alter prokaryotic microbial diversity and composition, as seen in the Grand River, Ontario, where increased Proteobacteria and Cyanobacteria and decreased Tenericutes and Bacteroidetes suggest compromised microbiome integrity and ecosystem services like nutrient cycling (Ruprecht et al., 2021; Millar et al., 2022). Similarly, estuarine fish exposed to metal contaminants show an increase in metal-resistant and pathogenic bacteria (Suzzi et al., 2022), with heavy metals like mercury, lead, and cadmium posing risks of oxidative damage and stimulation of antibiotic resistance gene transfer (Thomas et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2022; Thanigaivel et al., 2023; Abdulaziz Mustafa et al., 2024). In Ohio rivers, WWTP discharges contribute to the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genes in fish gut microbiomes (Ballash et al., 2022), with significant reductions in microbial diversity (Mills et al., 2024), and in Norwegian coastal waters, Atlantic cod contained bacteria linked to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) degradation, though microbiome responses to PAHs varied across environments (Walter et al., 2019). These findings highlight aquatic ecosystems and the fish gut microbiome as responsive to and as a potential biomarker for contamination.

Existing research has focused almost exclusively on prokaryotic communities, typically assessed using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. In contrast, utilizing the 18S gene to identify eukaryotic taxa (i.e. prey items and protozoans) within the gut of fishes in relation to contaminant exposure remains underexplored. This represents a gap in knowledge as eukaryotic taxa are integral to ecosystem functioning through organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling, parasitism, pollutant biotransformation, and food web dynamics (Covich et al., 1999; Hunting et al., 2012; Pharaoh et al., 2023). Benthic invertebrates are foundational to sediment-based food webs and can influence ecosystem resilience and recovery following disturbance (Covich et al., 1999). A study in Lake Ohrid, North Macedonia showed that benthic eukaryotic communities were shaped by habitat-specific environmental gradients, with deep profundal zones showing 15% higher diversity, greater community homogeneity, and the most complex ecological networks, traits associated with increased ecosystem stability (Wilden et al., 2021). These findings are especially relevant to studies of benthic fish, which interact closely with sediment-associated eukaryotic taxa. Furthermore, long-term biomonitoring studies have shown that invertebrate richness and community shifts can reflect improving water quality and enhance food web connectivity in recovering systems (Pharaoh et al., 2023).

Despite growing evidence of CECs in aquatic ecosystems, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding their impacts on fish gut microbiomes. The gut microbiome plays a critical role in fish health by influencing essential physiological functions including digestion, immune response, and development, with disruptions potentially leading to compromised health and disease susceptibility (Egerton et al., 2018). However, field studies examining the effects of WWTP effluent on gut microbiomes in wild fish populations are especially scarce, as are investigations comparing upstream and downstream impacts in the same river system. Addressing these gaps requires examining microbiome composition in fish species with limited mobility that experience chronic exposure to effluent discharge.

To address these knowledge gaps, this study assesses gut microbiome diversity in freshwater fish from the East Gallatin River. The East Gallatin River, flowing through southwestern Montana, provides a useful study system for examining the impacts of WWTP effluent on aquatic organisms. This river is ecologically and recreationally significant, supporting diverse fish populations and connecting to the larger Missouri River systems via the Gallatin River systems. Previous studies have identified a variety of contaminants of CECs in the East Gallatin River, including opioids, stimulants, and pharmaceutical compounds with variable removal during wastewater treatment (Bishop et al., 2020). These findings confirm the river as a relevant system for evaluating the potential biological impacts of WWTP effluent on aquatic organisms in the absence of industrial pollution. Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) and suckerfish (Catostomus spp.) were chosen as study organisms because their relatively limited habitat range and benthic feeding habits make them effective indicators of chronic exposure to anthropogenic contaminants.

The primary objective of this study was to compare the taxonomic composition of prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities in the intestines and stomachs of C. bondi and Catostomus spp. across sites upstream and downstream of WWTP discharge to evaluate the potential impacts of wastewater effluent on aquatic gut microbiomes. By using 16S rRNA sequencing, this study characterizes how prokaryotic gut microbial communities in benthic fish respond to wastewater exposure, highlighting potential shifts in bacterial taxa associated with anthropogenic disturbance. Additionally, 18S rRNA sequencing allows for the assessment of eukaryotic gut microbiome composition, filling a critical gap in understanding how both resident and transient eukaryotic communities within the fish gastrointestinal tract respond to environmental stressors.

Materials and methods

Collection site selection

Seven sites were selected along the East Gallatin River to study the impact of WWTP discharge on fish microbiomes. One site was situated 140 m upstream of the Bozeman WWTP outfall to serve as a negative control site (Site 1). The remaining six sites were downstream of the WWTP discharge, starting at 112 meters below the effluent discharge site (Site 3) and finishing 7.2 kilometers downstream (Site 9). On the first collection date, September 29, 2022, samples were collected at all sites. Thereafter, samples were only collected at Sites 1, 3, and 6 to provide deeper data for statistical analysis. These sites were selected for continued sampling based on preliminary toxicological analyses in from September 2022, indicating elevated contaminant concentrations at these locations (publication in prep).

Fish collection

Up to 10 Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) were collected at each site via backpack electrofishing on September 29, 2022, July 6, 2023, and October 6, 2023 (Table 1) using standard electrofishing procedures for wadable streams (Dunham et al., 2009). There is no power analysis software available to accurately address these types of data in new systems (Rahman et al., 2023). Therefore, based upon past experience with microbiome data our goal was to collect ten individuals per date per site, as microbiomes are variable among individuals, sites, and dates. Based upon the high numbers of Catostomus spp. that were incidentally obtained and released on September 29, 2022, permits were obtained to also collect this genus on July 6, 2023 and October 6, 2023. Stunned fish were immediately removed from the electrical field and target species were euthanized on site via pithing followed by decapitation. Samples were stored on ice and transported to the laboratory within a few hours for length and weight measurements and dissection (Supplementary Table S1). Stomach and intestine samples were placed in vials containing an RNA/DNA stabilizing buffer (25 mM sodium citrate, 10 mM EDTA and 70 g ammonium sulfate per 100 ml solution, pH 5.2) and stored at -80°C until DNA extraction.

Table 1

| Sites | 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance from WWTP | 140 m Upstream | 112 m Down-stream | 1809 m Down-stream | 2799 m Down-stream | 4770 m Down-stream | 6638 m Down-stream | 7219 m Down-stream | ||||||||

| Organ type | I | S | I | S | I | S | I | S | I | S | I | S | I | S | |

| Sept 29th, 2022 | Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) |

9 | 3 | 9 | – | 9 | 1 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | – | 11 | 1 |

| Suckerfish (Catostomus spp.) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| July 6th, 2023 | Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) |

11 | – | 5 | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Suckerfish (Catostomus spp.) | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Oct 6th, 2023 | Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) |

9 | 9 | 5 | 9 | – | – | 8 | 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Suckerfish (Catostomus spp.) | 7 | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | 1* | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

Data distribution. Number of intestine (I) and stomach (S) samples from Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) and suckerfish species (Catostomus spp.) Sampled on Sept 29th, 2022, July 6th, 2023, and Oct 6th, 2023. – indicates samples not collected or samples that did not pass quality control.

A total of 164 samples were analyzed; 150 C. bondi (104 intestines and 46 stomachs) and 14 Catostomus spp. (13 intestines and 1 stomach). The single Catostomus spp. stomach sample collected on Oct 6,2023 at Site 6 was not included in the data analysis.

While taxonomic identification via morphology of suckerfish to species level was not possible due the small size of the fish, based on regional distribution patterns they likely represent two species; Longnose Sucker (Catostomus catostomus) and White Sucker (Catostomus commersonii), both common throughout Montana waterways (Lee et al., 1980; Snyder and Muth, 1990). Additionally, it should be noted that the stomach 16S microbiome is likely to be more strongly influenced by microbes coming in on or in food items compared to the resident intestinal microbiome, and that 18S data reflect both eukaryotic prey items (macrofauna) and protists (microfauna).

DNA processing

The contents of each stomach and intestine were removed and placed directly into a PowerBead Pro tube for total DNA extraction using the Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro DNA extraction kit (Qiagen cat #47014) following the manufacturer’s instructions. We were unable to recover both stomach and intestinal contents for every sample. To generate taxonomic and proportional abundance profiles for each sample, the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was targeted for amplicon sequencing by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers 515F (5′-GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) (Parada et al., 2016) and 806R (5′-GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) (Apprill et al., 2015). PCR reactions included 2 µL template DNA, 0.5 µL each of forward and reverse primer (for a total concentration of 0.4 nM), 12.5 µL GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega) and 1 µL BSA (20 mg mL−1; New England BioLabs Inc.) and were brought up to 25 µL with molecular grade water (NEB). The thermal cycling protocol involved an initial denaturation at 95°C (3 min), followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C (45 s), primer annealing at 55°C (45 s), primer extension at 72°C (90 s), and a final extension at 72°C (10 min). Samples were then sent to the Research Technology Support Facility at Michigan State University for dual index barcoding and sequencing on a 250X250 V2 chemistry flow cell using Illumina MiSeq technology.

For 18S rRNA gene profiling, the V9 region of the eukaryotic small subunit (SSU) rRNA gene was amplified using PCR with Earth Microbiome Project primers 1391F (5′-GTACACACCGCCCGTC-3′) and EukBrR (5′-TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3′) (Stoeck et al., 2010). These primers target highly conserved sites flanking the V9 region. The forward primer, 1391F, is a broadly conserved three-domain primer and has been shown to capture a wider range of higher-level eukaryotic taxa compared to more narrowly targeted eukaryote-specific primers for the same gene region (Stoeck et al., 2010). PCR reactions included 2 µL template DNA, 0.5 µL each of forward and reverse primer (for a total concentration of 0.4nM), 12.5 µL GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega) and 1 µL BSA (20 mg mL−1; New England BioLabs Inc.) and were brought up to 25 µL with molecular grade water (NEB). The thermal cycling protocol involved an initial denaturation at 95°C (3 min), followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C (45 s), primer annealing at 55°C (45 s), primer extension at 72°C (90 s), and a final extension at 72°C (10 min). Samples were then sent to the Research Technology Support Facility at Michigan State University for dual index barcoding and sequencing 150X150 V2 chemistry flow cell using Illumina MiSeq technology.

For 16S and 18S quality control, three extraction blanks and two negative PCR controls were sequenced, and were removed by the quality control process during sequence analysis. The 16S and 18S sequences are deposited in the Sequence Read Archive under bioproject PRJNA1208553: Microbial community in the gut of Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) and suckerfish (Catostomus spp). Individual sample accessions, including IDs, dates, sites, and species, are accessible via the NCBI SRA metadata under PRJNA1208553.

16S rRNA gene sequencing and analysis

Raw sequences were processed using QIIME2 (v2022.8; Bolyen et al., 2019) to generate a cleaned, taxonomically annotated and phylogenetically contextualized Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) abundance table. Briefly, raw fastq files were imported into QIIME2. The reads were denoised, merged and chimeras filtered with read trimming parameters: (`–p-trim-left-f 10 –p-trim-left-r 10 –p-trunc-len-f 230 –p-trunc-len-r 230`) using DADA2 (Callahan et al., 2016). Taxonomy was assigned to each ASV using the Silva 138 515–806 database (Quast et al., 2013). ASVs annotated as mitochondria, chloroplast, and common laboratory contaminants were removed (Supplementary Table S2). Additionally, potential contaminating sequences were identified with the decontam package (Davis et al., 2018) and removed. The ASV abundance table was rarefied to 8,403 reads per sample without replacement, striking a balance between retaining as many samples as possible, while removing poorly sequenced libraries (removing 16 out of 182 samples) to ensure equal sequencing depth across samples. The normalized data were used for all subsequent analyses.

The ASV abundance, phylogeny, and taxonomy data generated by QIIME2 were imported into R (v.4.4.0) and processed using the qiime2R (Estaki et al., 2020) and phyloseq packages (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013). A phyloseq object was created to integrate the ASV abundance data, phylogenetic tree, taxonomy table, and metadata. Alpha diversity indices, including richness and Shannon diversity (both evaluated at the ASV level), were calculated using standard estimation methods. Not all prokaryotic taxa were identified to the species level due to database or resolution limitations. Data distribution for richness and Shannon diversity were evaluated using histograms and Q-Q plots. Richness was normally distributed, while Shannon diversity was not. Thus, the parametric test ANOVA was used to test differences in richness between groups, while the non-parametric test, Kruskal-Wallis, was used for Shannon diversity. Beta diversity was assessed using Bray-Curtis distances utilizing functions from the vegan R package (Dixon, 2003). The Permutational Multivariate ANOVA (PERMANOVA) test was implemented by the adonis() function to test the differences in multivariate clustering and location among the evaluated groups. To analyze the multivariate homogeneity of group dispersions, the betadisper() function on the vegan package was used for beta dispersion analysis. Diversity indices, ordinations, and percent abundancies of the top 20 taxa at the ASV level were visualized using the ggplot2 package (Gauthier and Derome, 2021).

DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) was used to identify differentially enriched prokaryotic classes within the intestines of C. bondi between Sites 1 and 3. To do this, the ASV abundance table was agglomerated at the class level using the R package phyloseq (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013). DESeq2 was run with the parameters: test=“Wald”, fitType=“parametric”. Site 6 was excluded from this analysis to ensure a balanced statistical design. Only taxa with an adjusted P value < 0.1 and log Fold change > 1 were included in subsequent analyses. This comparatively relaxed p value was selected to ensure we report as many potential significant trends in this novel system as possible, with the expectation that these trends could be the target of future studies.

18S rRNA gene sequencing and analysis

Raw sequences were processed using QIIME2 to generate a cleaned, taxonomically annotated and phylogenetically contextualized ASV abundance table. Raw fastq files were imported into QIIME2 (v2022.8; Bolyen et al., 2019). The reads were denoised, merged and chimeras filtered with read trimming parameters: (`–p-trim-left-f 5 –p-trim-left-r 5 –p-trunc-len-f 240 –p-trunc-len-r 240 `) using DADA2 (Callahan et al., 2016). Taxonomy was assigned to each ASV by aligning each sequence against the NCBI’s eukaryotic small subunit (SSU) rRNA database (Wuyts et al., 2002) using BLASTn (McGinnis and Madden, 2004). Each ASV was assigned the taxid of the top alignment with a percent identity above 80%. Taxonkit (Shen and Ren, 2021) was used to reformat the taxid lineage into a consistent format. Potential contaminating sequences were identified with the decontam package (Davis et al., 2018) and removed. The taxid linage file was further filtered to remove host sequences. The sequences identified as host sequences were then used to delineate the two variants of Catostomus, though species-level identification was not possible due to lack of accurate 18S rRNA gene reference sequences for this genus. Finally, the top 20 eukaryotic taxa per species and organ were visualized using the ggplot2 package in R (Gauthier and Derome, 2021). Not all eukaryotic taxa were identified to the species level due to database or resolution limitations. Additionally, it is possible that not all Eukaryotes were detected using these universal primers.

Results

Sample size and distribution

A total of 164 gastrointestinal samples were collected from Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) and suckerfish (Catostomus spp.) across three sampling dates: September 29, 2022; July 6, 2023; and October 6, 2023 (Table 1). Of these, 150 samples were from C. bondi (104 intestines, 46 stomachs), and only 14 were from Catostomus spp. (13 intestines, 1 stomach) due to an unexpected drop in Catostomus spp. abundance in 2023. However, these data were retained as no microbiome data are currently available for these species. Sampling occurred at seven sites (Sites 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9), although not all sites or dates yielded the same number or type of GI samples due to variation in fish availability and gut contents. Notably, the single suckerfish stomach sample collected on October 6, 2023 at Site 6 was excluded from the final analysis due to lack of replicates. This uneven distribution reflects logistical constraints in field sampling of wild fish populations and highlights the value of including multiple timepoints and anatomical compartments in microbiome studies, and it must be recognized that this may limit the power of our analyses when comparing the two species.

Prokaryote alpha and beta diversity metrics for C. bondi

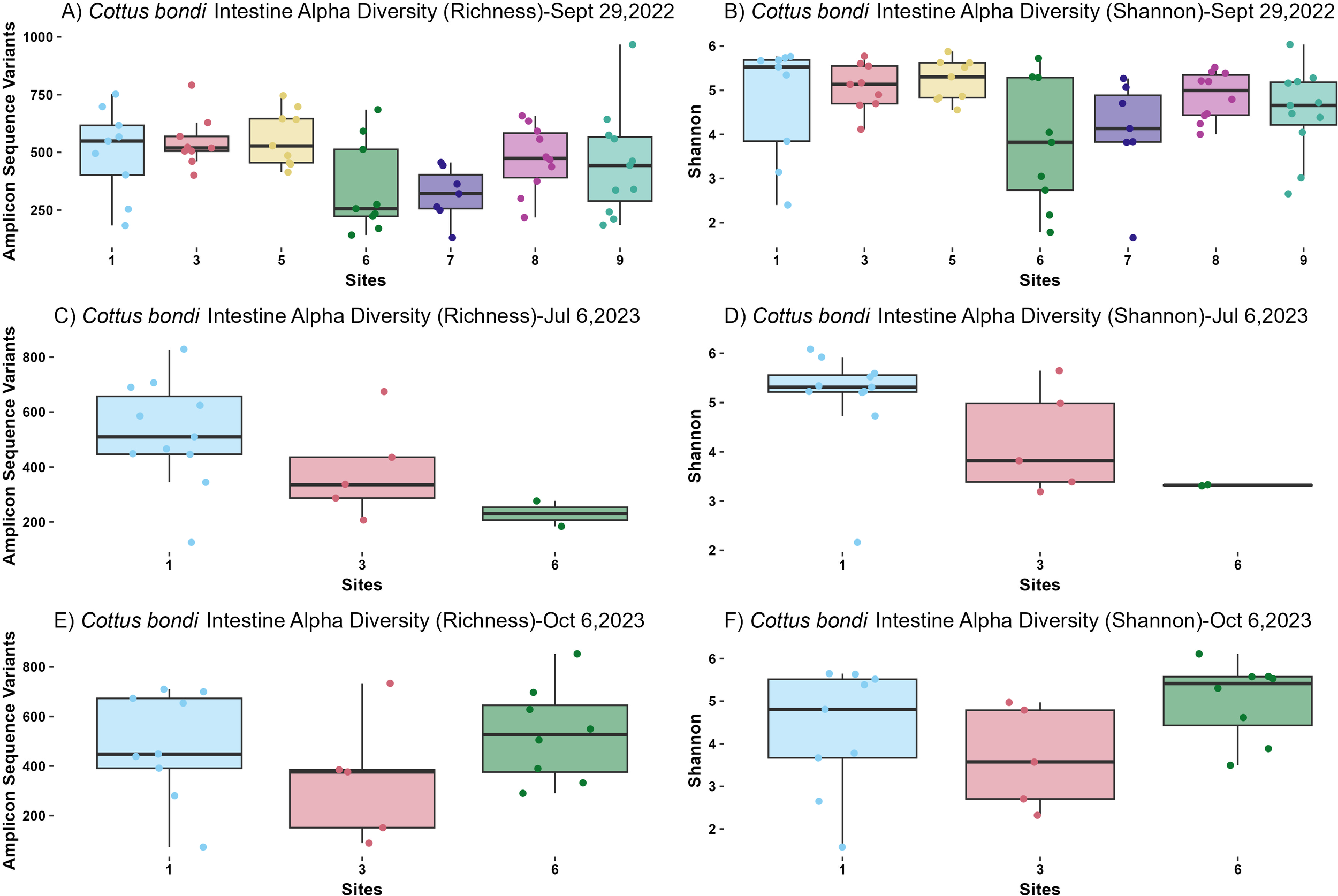

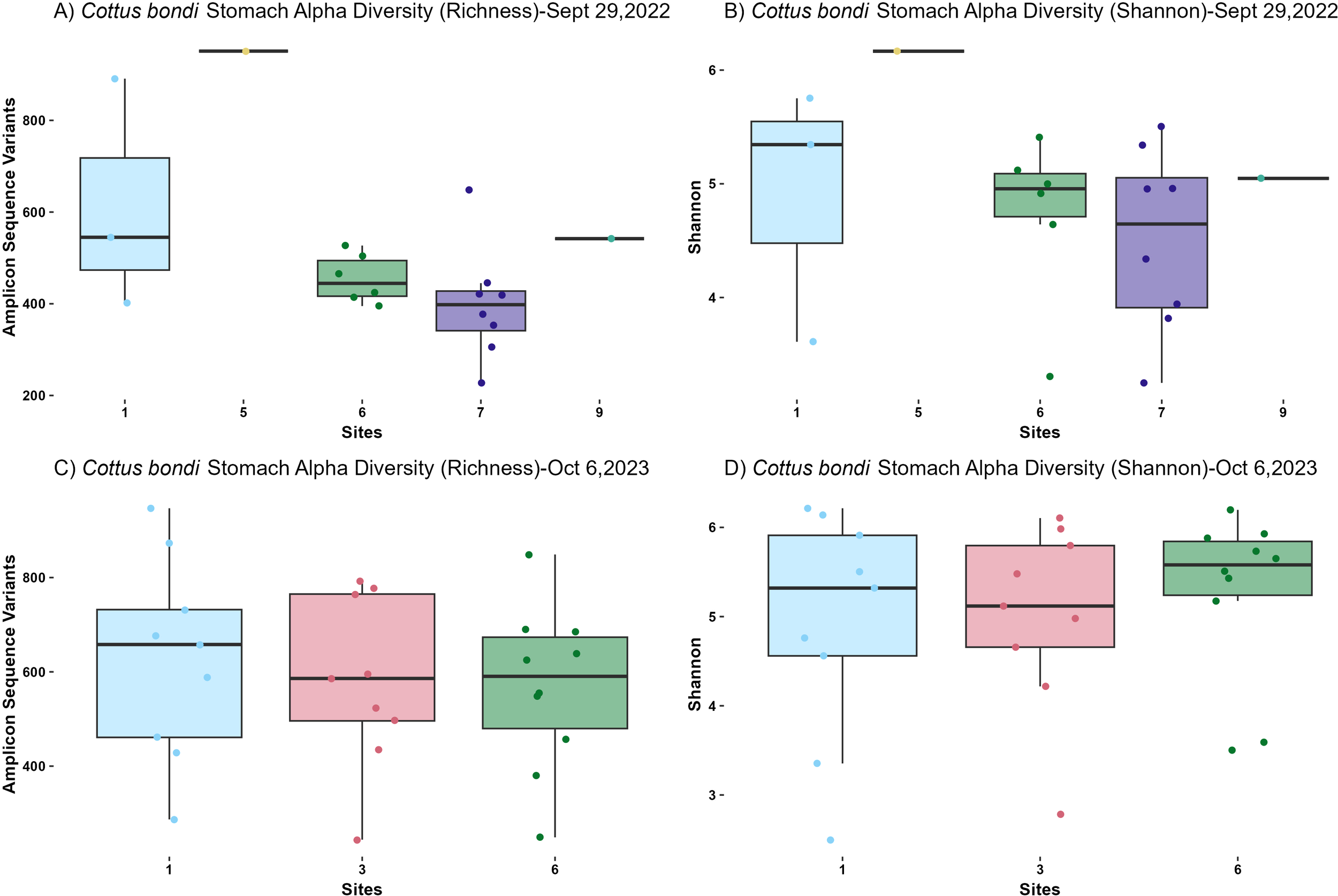

The alpha diversity of microbial communities in both the intestines and stomachs of C. bondi was assessed using richness and Shannon diversity indices. The intestines were sampled on three dates—September 29, 2022, July 6, 2023, and October 6, 2023 (Figure 1)—while the stomachs were sampled on September 29, 2022, and October 6, 2023 (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Alpha diversity metrics from microbial communities in the intestines of Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) collected at one site upstream of the WWTP (Site 1) and multiple sites downstream of the WWTP at the East Gallatin River (Sites 3-9) during the fall of 2022 and summer and fall of 2023. (A) Observed Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) for Sept 19th, 2022. A significant difference was detected between sites (p= 0.02776, ANOVA). Pairwise comparisons did not show significant differences between specific site pairs, possibly due to variability in sample sizes. (B) Shannon diversity index for Sept 19th, 2022 for C. bondi intestines across different sites showing no significant difference (p=0.059, Kruskal-Wallis). (C) Observed ASVs for July 6th 2023. No significant differences were observed between sites (p=0.1054, ANOVA). (D) Shannon diversity index for July 6th 2023 showing no significant differences between sites (p=0.085, Kruskal-Wallis). (E) Observed ASVs for Oct 6, 2023. No significant differences were observed between sites (p=0.344, ANOVA). (F) Shannon diversity index for Oct 6, 2023 showing no significant differences (p=0.163, Kruskal-Wallis).

Figure 2

Alpha diversity metrics from microbial communities in the stomachs of Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) collected at one site upstream the WWTP (Site 1) and multiple sites downstream the WWTP at the East Gallatin River (Sites 3-9) during the fall of 2022 and fall of 2023 separated by date of collection. (A) Observed Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) for Sept 29, 2022. A significant difference was observed between sites (p= 0.01257, ANOVA). There was only one sample from sites 5 and 9, which limits the statistical power and significance of pairwise comparisons involving these sites. (B) Shannon diversity index for Sept 29, 2022 for C. bondi stomachs across different sites showing no significant differences (p=0.4219, Kruskal-Wallis). (C) Observed ASVs for Oct 6, 2023. No significant differences were detected between sites (p=0.7688, ANOVA). (D) Shannon diversity index for Oct 6, 2023 showing no significant differences between sites (p=0.7671, Kruskal-Wallis).

On September 29, 2022, intestinal samples showed a statistically significant difference in richness among sites (P=0.02776, ANOVA; Figure 1A). Although pairwise comparisons did not reveal significant differences between specific site pairs, Site 6 had the lowest richness and Site 1 had the highest. Shannon diversity index did not show significant differences across sites (P=0.059, Kruskal-Wallis; Figure 1B). Similarly, in the stomachs, richness exhibited a statistically significant difference among sites (P=0.01257, ANOVA; Figure 2A). However, the limited sample size from Sites 5 and 9 (1 sample at each site) reduced the statistical power for pairwise comparisons involving these sites. The Shannon diversity index for the stomachs showed no significant differences among sites (P=0.4219, Kruskal-Wallis; Figure 2B).

On July 6, 2023, intestinal samples showed no significant differences among sites for richness (P=0.1054, ANOVA; Figure 1C) or Shannon diversity index (P=0.085, Kruskal-Wallis; Figure 1D). However, there remained a consistent pattern of lower diversity at sites downstream of the WWTP.

For both the intestines and stomachs sampled on October 6, 2023, no significant differences in richness were detected among sites (P=0.344, ANOVA for intestines; P=0.7688, ANOVA for stomachs; Figures 1E, 2C). Similarly, the Shannon diversity index showed no significant differences (P=0.163, Kruskal-Wallis for intestines; P=0.7671, Kruskal-Wallis for stomachs; Figures 1F, 2D).

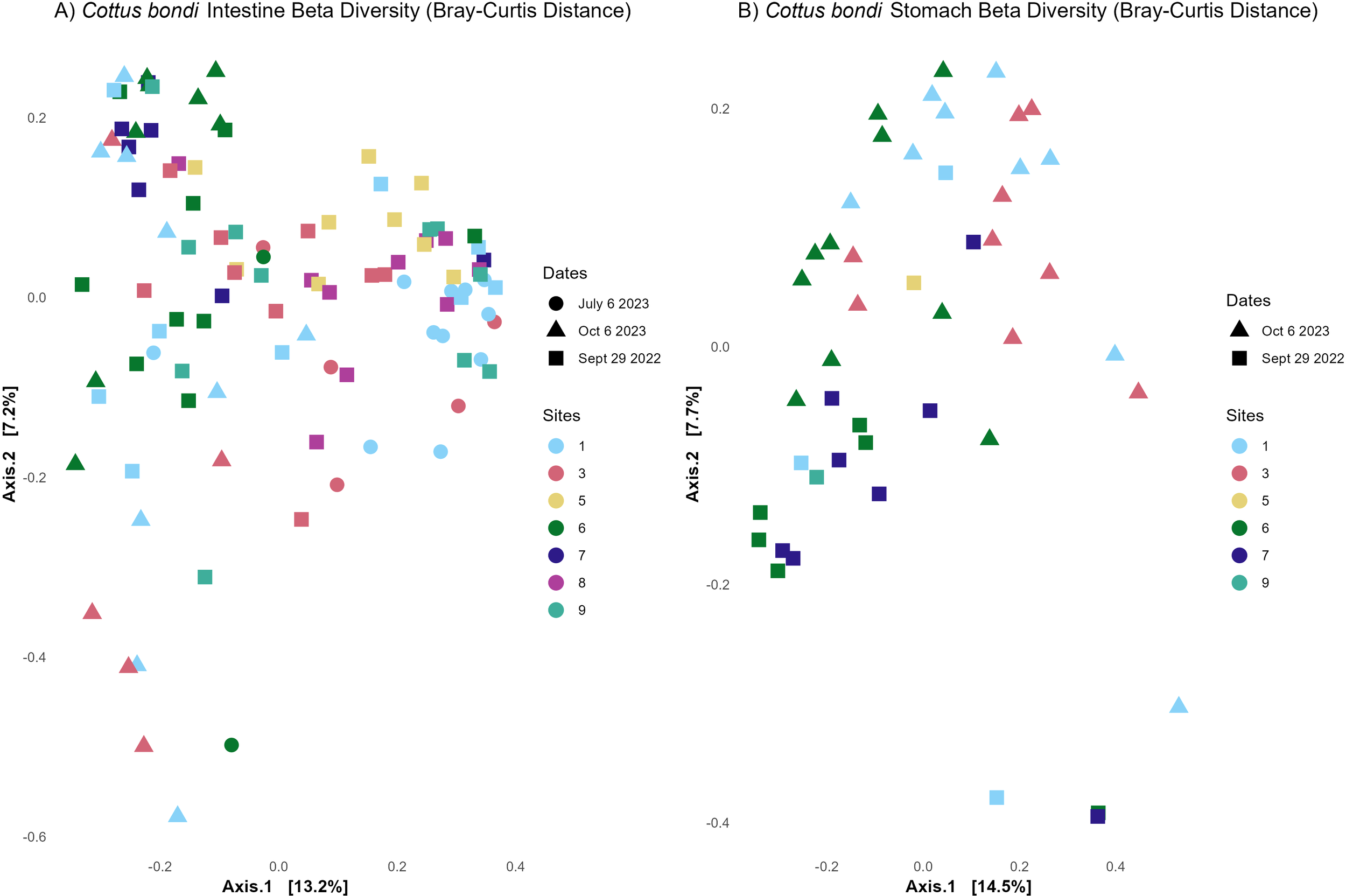

For the intestinal microbial community beta diversity was analyzed using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (Figure 3A). The PERMANOVA test revealed significant differences in microbial community composition among sites (P=0.001, PERMANOVA) and across the three collection dates (P=0.001, PERMANOVA), indicating that the microbial communities in the intestines differed significantly over space and time. Pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between specific sites: Site 1 vs 6 (P=0.021) and Site 3 vs 6 P=0.021, PERMANOVA. All other site comparisons were not statistically significant.

Figure 3

Beta diversity from microbial communities in the intestines and stomachs of Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) collected at one site upstream the WWTP (Site 1) and multiple sites downstream the WWTP (sites 3-9) at East Gallatin River during the fall of 2022 and summer and fall of 2023. (A) Bray-Curtis distances for sculpin’s intestine showing significant differences in microbial community composition between sites (p=0.001, PERMANOVA) and dates (p=0.001, PERMANOVA) (B) Bray-Curtis distances for C. bondi stomachs showing significant differences in microbial community composition between sites (p=0.002, PERMANOVA) and dates (p=0.008, PERMANOVA).

The beta dispersion analysis, which measured microbial variability within each site, showed a significant difference in variability among sites and dates (P=0.011, ANOVA for sites; P=<0.001, ANOVA for dates), suggesting that the observed differences in the PERMANOVA results are due to differences intrasample variability. Pairwise comparisons for beta dispersion indicated significant variability between Site 1 and Site 5 (P=0.034). All other site comparisons were not significant.

Similarly, for the stomach microbiome (Figure 3B), significant differences in microbial community composition were observed among sites (P=0.002, PERMANOVA) and dates (P=0.008, PERMANOVA), confirming that the microbial communities in the stomachs of C. bondi also vary significantly depending on the site and date of collection. As with the intestines, the beta dispersion analysis revealed significant differences in variability among sites (P=<0.001 ANOVA) but not dates (P=0.197, ANOVA), suggesting that the observed differences in the site PERMANOVA results are due to differences in variability across sites. However, the differences across dates are driven by changes in community composition. PERMANOVA Pairwise comparisons show significant differences between Site 1 and Site 6 (P=0.042), as well as between Site 3 and Site 6 (P=0.028), while other comparisons like Site 1 vs 3 (P=0.10) were not significant.

The beta dispersion pairwise comparisons revealed no significant differences in variability between Site 1 and Site 6 (P=0.407) or between Site 3 and Site 6 (P=0.420), supporting that the observed site-specific changes are driven more by community composition than by intrasample variation.

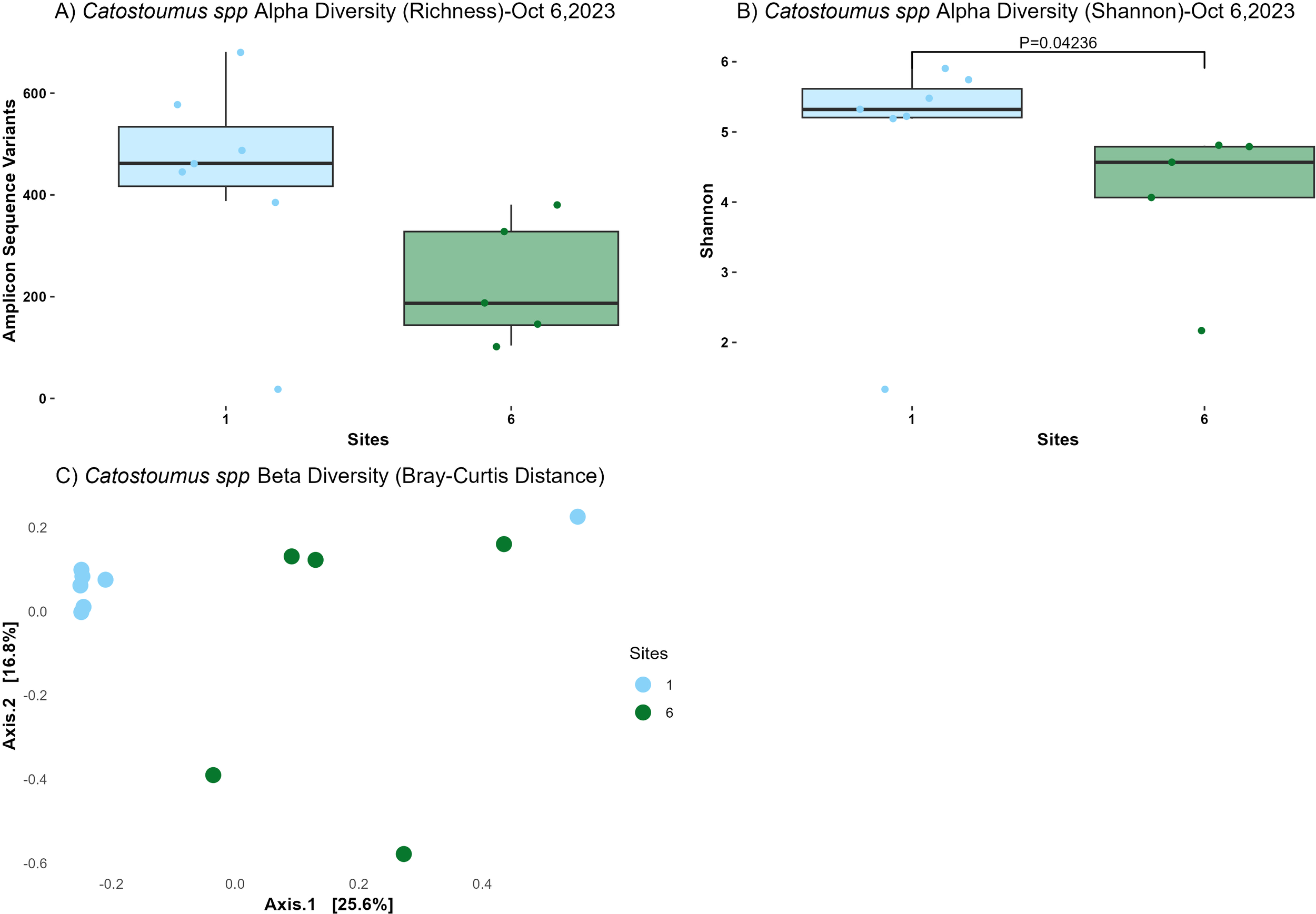

Prokaryote alpha and beta diversity metrics for Catostomus spp.

The richness diversity index did not show a statistically significant difference between Sites 1 and 6 (P=0.07313, ANOVA; Figure 4A). However, there was a trend indicating lower richness at Site 6 compared to Site 1 when using a more relaxed p-value threshold (P = 0.10). In contrast, the Shannon diversity index revealed a significant difference between the two sites (P=0.04236, Kruskal-Wallis; Figure 4B). This significant reduction in Shannon diversity downstream of the WWTP suggested that the microbial communities at Site 6 were less diverse as compared to Site 1.

Figure 4

Alpha and beta diversity metrics from microbial communities in the intestines of suckerfish (Catostomus spp) collected at one site upstream the WWTP (Site 1) and one site downstream the WWTP (Site 6) at the East Gallatin River on Oct 6th, 2023. (A) Observed Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). No significant difference was detected between sites 1 and 6 (p= 0.07313, ANOVA). (B) Shannon diversity index for Castostomidae spp. intestines showing significant differences (p=0.04236, Kruskal-Wallis). (C) Bray-Curtis distances for Castostomidae spp. intestines showing significant differences in microbial community composition between sites (p=0.017, PERMANOVA). Both Catostomus species are pooled for more statistical power in this analysis.

Beta diversity, assessed using Bray-Curtis distances, indicated significant differences in microbial community composition between sites (P=0.017, PERMANOVA; Figure 4C). Moreover, the lack of significant beta dispersion (P=0.2078, ANOVA) indicated that these differences are due to variations in community composition between sites rather than within-site variability. While it is possible that there were significant differences between the two Catostomus species, we were not able to test this due to low statistical power.

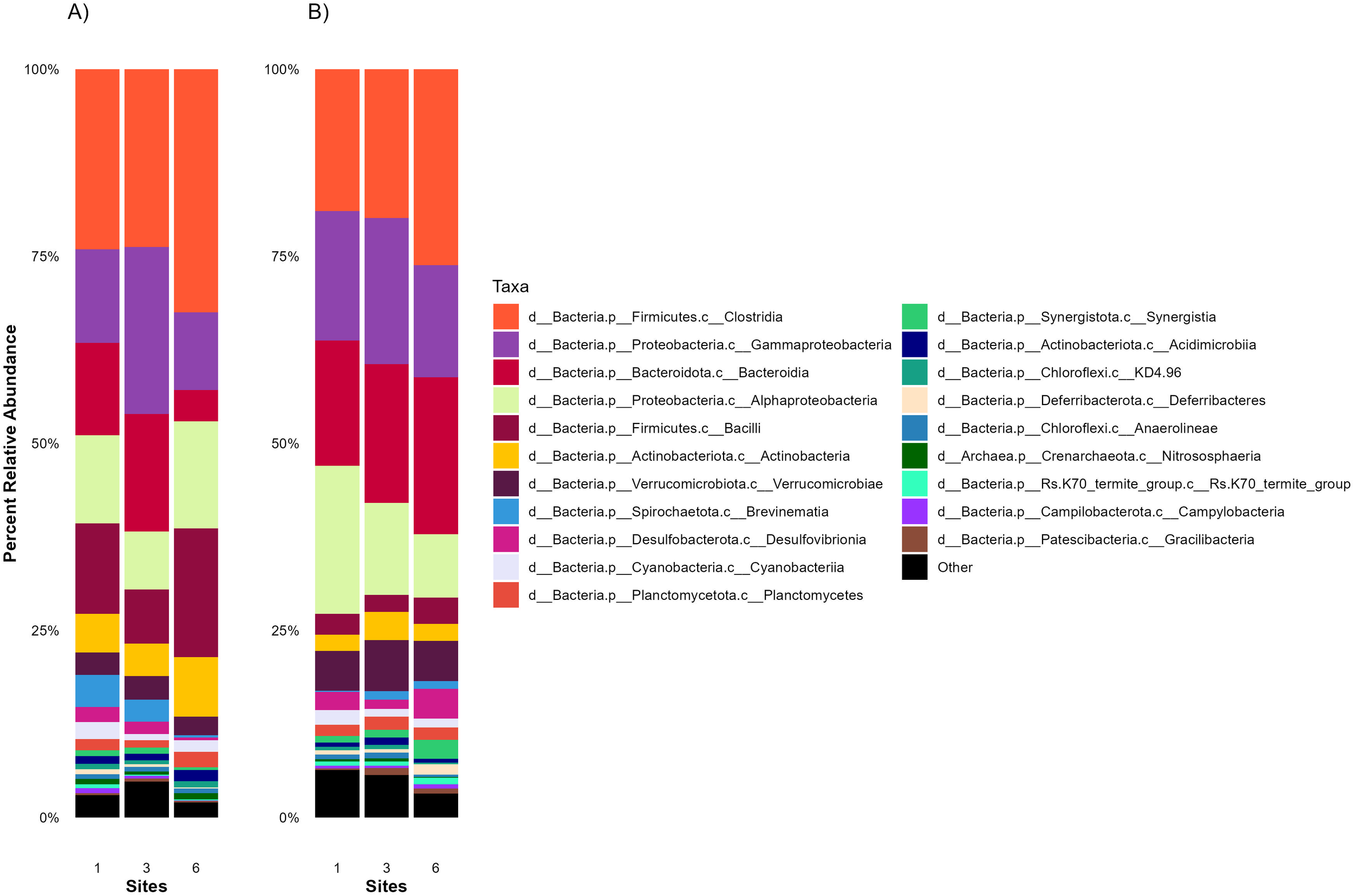

Relative abundance of top 20 prokaryotic classes in C. bondi at Sites 1, 3 and 6

The relative abundance of the top 20 prokaryotic classes in the intestines and stomachs of C. bondi collected from Site 1 (upstream of the WWTP) and Site 3 and Site 6 (downstream of the WWTP), highlighted differences microbial taxa across the sites (Figure 5). In the intestines, six main classes dominated the microbial community: Clostridia, Gammaproteobacteria, Bacteroidia, Bacilli, Alphaproteobacteria, and Actinobacteria. The relative abundance of these classes varied across sites.

Figure 5

Average 16S relative abundances of the top 20 taxa in the intestines and stomachs of Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) collected at one site upstream the WWTP (Site 1) and two sites downstream the WWTP (Sites 3 and 6) at the East Gallatin River on Sept 29, 2022, July 6 and Oct 6, 2023. The stacked bar chart illustrates the average 16S relative abundances of the top 20 taxa in the (A) intestines and (B) stomachs of C. bondi at each site. Each bar represents a site, with different colors indicating the average relative abundance of various microbial classes.

In the stomachs, the same dominant classes were present, but their relative abundances differed slightly compared to the intestines. Gammaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria and Bacteroidia were more abundant, potentially reflecting the stomach’s harsher conditions and the bacterial community’s adaptation to the environment. Moreover, Verrucomicrobiae shows a notable increase in the stomach with a decrease of Bacilli.

Significant differences in prokaryotic genera in C. bondi at Sites 1 and 3

Comparing microbial communities across Sites, overall structure remained stable though subtle shifts in specific taxa were observed. These findings were supported by the DESeq2 analysis (Table 2) of the intestinal microbiota (class level) at Sites 1 and 3, which revealed significant differences in microbial abundance. At Site 1, taxa associated with sulfate reduction (Desulfobulbia, Desulfobaccia, and Desulfobacter), anaerobic metabolism (Methanosarcinia), and potential nitrogen cycling (Cyanobacteriia) were enriched, suggesting active microbial-mediated biogeochemical processes that support nutrient cycling.

Table 2

| Enriched in site: | Log2 fold change | p-value (adjusted) | Genus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.574571053 | 0.003101786 | Desulfobulbia |

| 1 | 1.299172006 | 0.003101786 | Desulfobaccia |

| 1 | 1.194421144 | 0.015306785 | Desulfobacteria |

| 1 | 1.474588967 | 5.57e-04 | Methanosarcinia |

| 1 | 1.665738714 | 0.001750068 | Elusimicrobia |

| 1 | 1.194626439 | 0.049455569 | Negativicutes |

| 1 | 1.12189326 | 0.003101786 | Cyanobacteria |

| 3 | -2.649358916 | 6.13e-06 | SAR324clade(Marine group B) |

| 3 | -1.234698312 | 0.015306785 | Nitrospiria |

| 3 | -1.051968587 | 0.043938867 | Desulfitobacteriia |

| 3 | -1.229986511 | 0.052269294 | Gracilibacteria |

| 3 | -2.473765541 | 5.40e-05 | Fusobacteriia |

Differential abundance analysis of microbial genera in the intestines of Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) between the site upstream the WWTP (Site 1) and one side downstream theWWTP (Site 3), using DESeq2 (Wald test, fitType=“parametric”).

Only taxa with log2 fold changes greater than 1 and adjusted p-values below 0.1 were included.

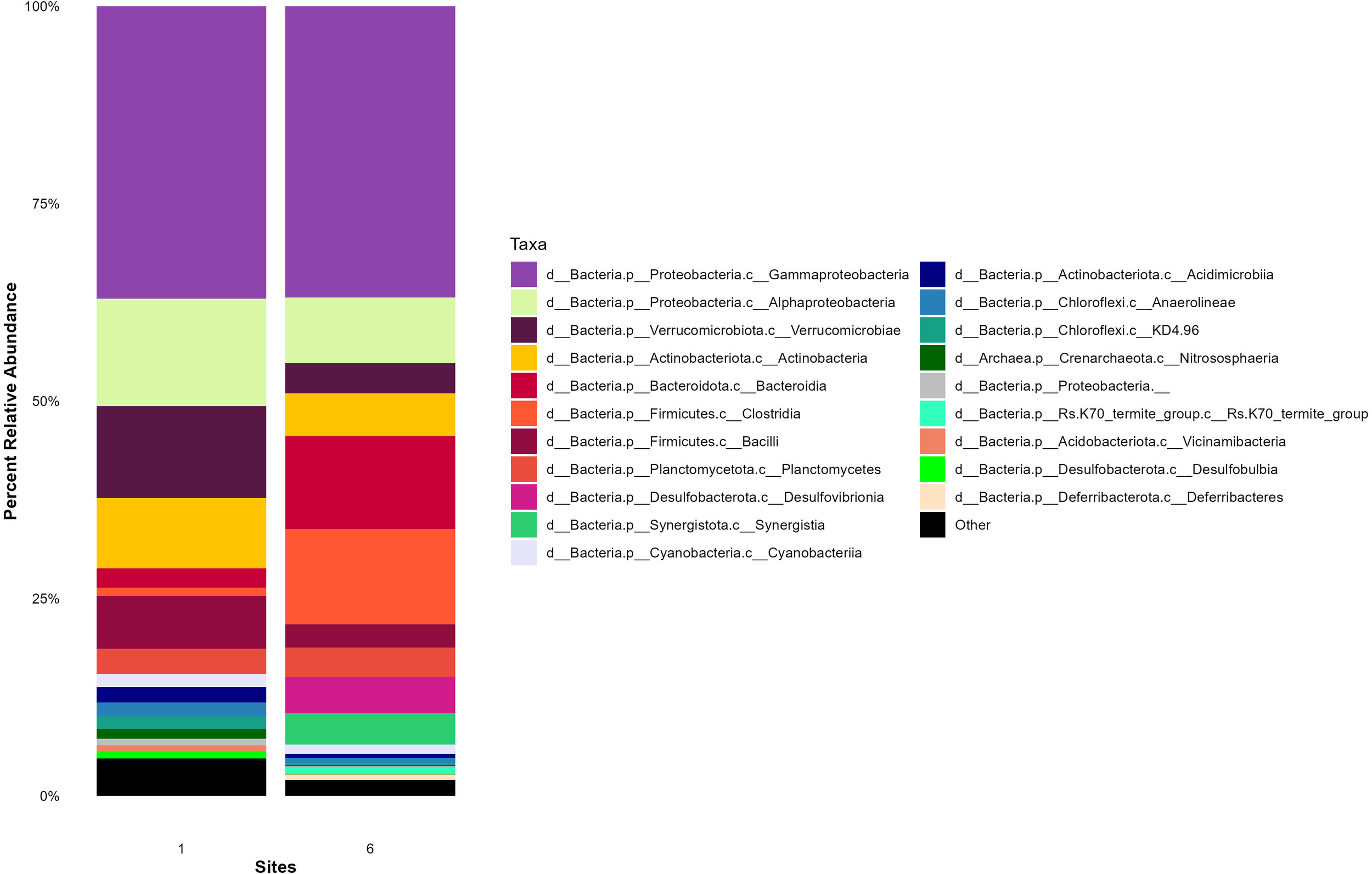

Relative abundance of top 20 prokaryotic taxa in Catostomus spp. at Sites 1 and 6

The relative abundance of the top 20 prokaryotic taxa (class level) in the intestines and stomachs of Catostomus spp. collected from Site 1 (upstream of the WWTP) and Site 6 (downstream of the WWTP), highlighted differences microbial taxa across the sites (Figure 6). In the intestines of Catostomus spp. (Figure 6), the microbial community is dominated by five main classes: Gammaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Verrucomicrobiae, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidia.

Figure 6

Average 16S relative abundances of the top 20 taxa in the intestines of suckerfish (Catostomus spp) collected at one site upstream the WWTP (Site 1) and one site downstream the WWTP (Site 6) at the East Gallatin River on July 6 and Oct 6, 2023. The stacked bar chart illustrates the average 16S relative abundances of the top 20 taxa in the intestines of Catostomus spp. at each site. Each bar represents a site, with different colors indicating the average relative abundance of various microbial groups. Both Catostomus species are pooled for more statistical power in this analysis.

When comparing the microbial communities between Site 1 and Site 6, the overall structure remained relatively stable, with the same dominant classes present at both sites. However, there were differences in the relative abundance of these classes, particularly Alphaproteobacteria, Verrucomicrobiae and Actinobacteria, which were more prevalent at the upstream Site 1.

Differences in C. bondi vs Catostomus spp. prokaryotic community

Cottus bondi exhibited a significantly higher richness as compared to Catostomus spp. (P=0.0251, ANOVA; Supplementary Figure S1A). However, no significant differences were observed in Shannon diversity (P=0.3547, Kruskal-Wallis), which suggests similar diversity levels in terms of evenness for both species (Supplementary Figure S1B), or that uneven sample sizes limited statistical power in comparing the two species. The significant difference in richness suggested that C. bondi intestines harbor a more diverse microbial community compared to Catostomus spp. A PERMANOVA test between species revealed significant differences in microbial community composition (P=0.001, PERMANOVA, Supplementary Figure S1C). However, beta dispersion analysis indicated no significant differences in dispersion between species (P=0.1638). The differences between the two host species were due to differences in community composition rather inter-species variability.

The intestinal microbiota of C. bondi (Supplementary Figure S2) was characterized by a notably higher proportion of Clostridia and Bacilli compared to Catostomus spp., suggesting a greater presence of Firmicutes phyla members potentially involved in fermentation and nutrient processing. In contrast, Catostomus spp. exhibited higher relative abundances of Verrucomicrobiae, Alphaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, and Bacteroidia, though their relative proportions varied. These differences in taxonomic profiles support the PERMANOVA results (Supplementary Figure S1) and suggest that host species influenced the gut microbial community composition, likely driven by host-specific factors such as trophic behavior, gut morphology, and habitat conditions.

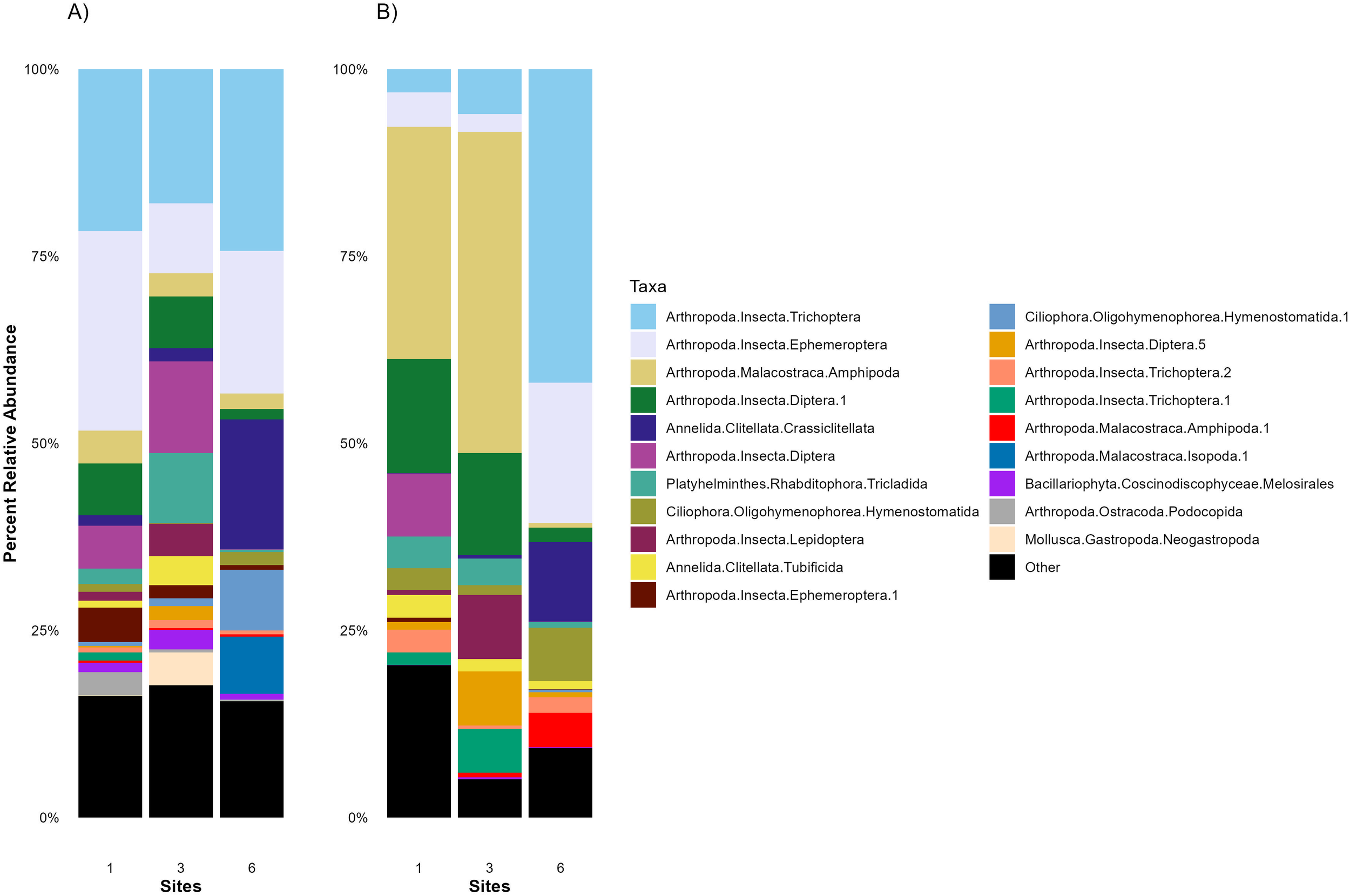

Relative abundance of eukaryotic taxa in C. bondi at Sites 1, 3 and 6

In the intestines of C. bondi, the eukaryotic composition was dominated by several taxa, with some variation observed between the upstream and downstream sites (Figure 7A). The dominant taxa included Trichoptera (Caddisflies), Ephemeroptera (Mayflies), Amphipoda (Amphipods), and Diptera (True Flies). Amphipoda, small crustaceans, and Diptera, which include various aquatic larvae, were also present, reflecting the benthic feeding habits of C. bondi.

Figure 7

Average 18S relative abundances of the top 20 taxa in the intestines and stomachs of Rocky Mountain Sculpin (Cottus bondi) collected at one site upstream the WWTP (Site 1) and two sites downstream the WWTP (Sites 3 and 6) at the East Gallatin River on Sept 29, 2022, July 6 and Oct 6, 2023. The stacked bar chart illustrates the average 18S relative abundances of the top 20 taxa in the (A) intestines and (B) stomachs of C. bondi at each site. Each bar represents a site, with different colors indicating the average relative abundance of various microbial groups. Averages are calculated from values presented in Supplementary Table S3.

At downstream sites, there was a shift in taxonomic composition. This shift may be influenced by the WWTP effluent, which can alter nutrient levels, organic matter availability, and overall biodiversity. For example, at Site 3, the relative abundance of Tubificida (a group of oligochaete worms) and the relative abundance of Tricladida (a group of flatworms) increased. In contrast, at Site 6, there was an increase in Crassiclitellata (segmented worms), which contribute to sediment processing and are adapted to organic-rich environments.

The stomachs of C. bondi exhibited a similar, though not identical, eukaryotic composition to that found in the intestines (Figure 7B). The same dominant taxa, including Trichoptera, Ephemeroptera, Amphipoda, and Diptera, are observed. However, the relative abundances differed, reflecting the immediate intake before digestion and absorption begin in the intestines. The stomachs showed a higher relative abundance of Amphipoda and Diptera at Site 3 as compared to Sites 1 and 6, suggesting that these taxa may be more readily available or preferred in this location. While Trichoptera and Ephemeroptera had a higher relative abundance at Site 6.

When comparing the eukaryotic composition among the sites, the general pattern of dominant taxa remained consistent, underscoring the dietary preferences and exposure of C. bondi to these eukaryotic organisms. However, the spatial shift in relative abundance highlights how the fish’s microbiome is influenced by the environmental conditions at different locations. The downstream sites show a slight shift towards dominant taxa that may be more resilient to pollution or lower water quality, such as Tubificida, Crassiclitellata, and other benthic organisms associated with disturbed environments.

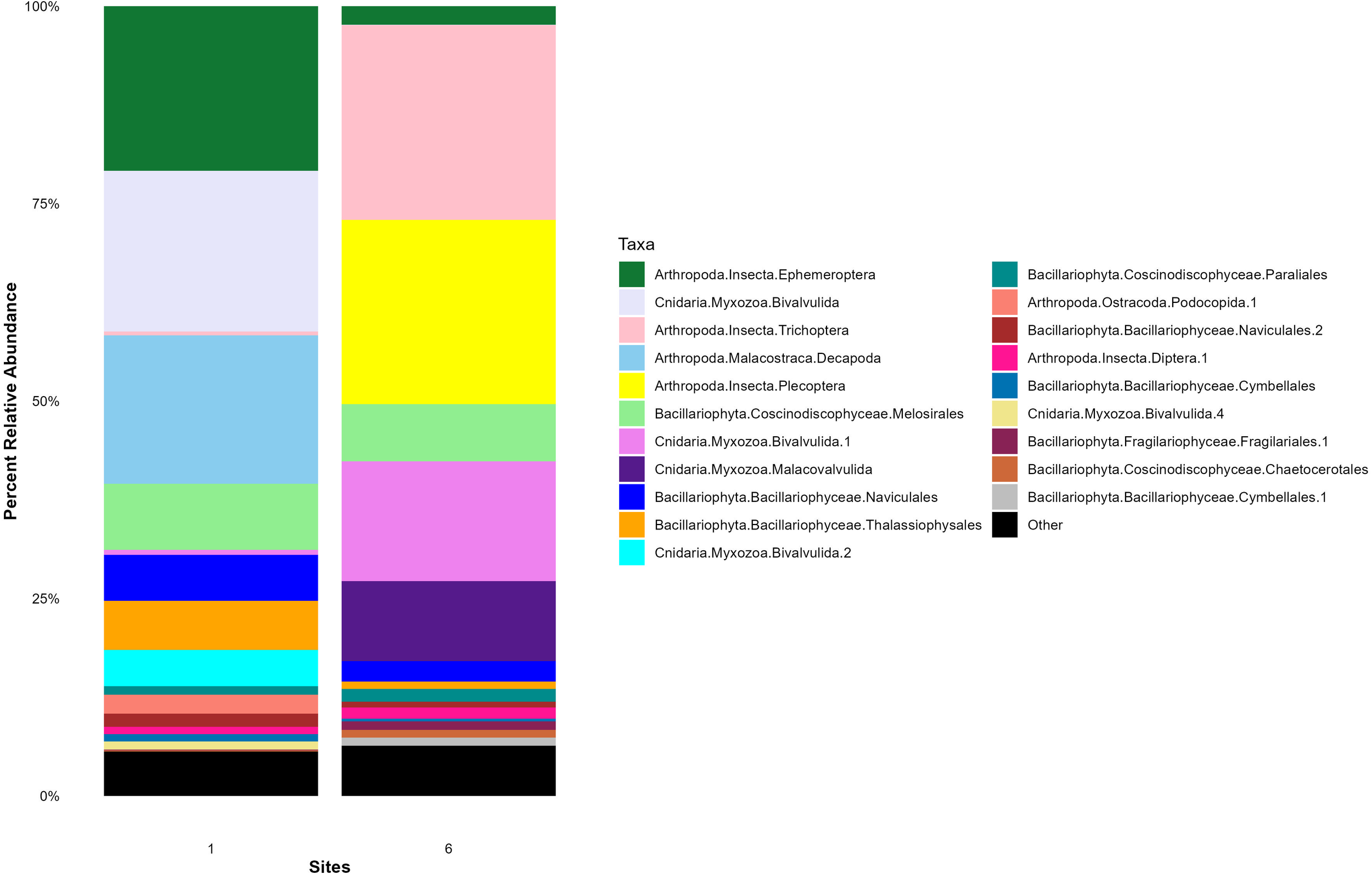

Relative abundance of eukaryotic taxa in Catostomus spp. at Sites 1 and 6

At Site 1, the eukaryotic community composition of Catostomus spp. was predominantly composed of various aquatic insects and diatoms (Figure 8). The most prominent taxa included, Ephemeroptera (Mayflies), Decapoda (Crustaceans), Bivalvulida (parasites) and several classes of diatoms from the Bacillariophyceae group, such as Naviculales, Cymbellales, and Thalassiophysales. At Site 6, the eukaryotic composition shifts noticeably (Figure 8). There is a marked increase in Plecoptera (stoneflies) and Trichoptera (caddisflies). Additionally, Cnidaria (Myxozoa), a group of parasitic organisms, are present in higher abundance at Site 6. This site also exhibited greater diatom diversity, suggesting that Catostomus spp. may be more exposed to benthic algae and associated microorganisms. This shift in food availability could be driven by altered nutrient input, habitat conditions, or feeding behavior in response to downstream environmental changes.

Figure 8

Average 18S relative abundances of the top 20 taxa in the intestines of suckerfish (Catostomus spp) collected at one site upstream the WWTP (Site 1) and one site downstream the WWTP (Site 6) at the East Gallatin River on July 6 and Oct 6, 2023. The stacked bar chart illustrates the average 18S relative abundances of the top 20 taxa in the intestines of Catostomus at each site. Each bar represents a site, with different colors indicating the average relative abundance of various microbial groups. Both Catostomus species are pooled for more statistical power in this analysis. Averages are calculated from values presented in Supplementary Table S4.

Differences in relative abundance of eukaryotic taxa in Catostomus spp. and C. bondi

The relative abundance of top 20 eukaryotic taxa between the sampled species (Supplementary Figure S3) showed distinct dietary signatures between species, reflecting differences in feeding behavior and environmental exposure. Cottus bondi, a benthic invertivore, exhibited a more taxonomically diverse eukaryotic community, dominated by insect taxa such as Trichoptera (caddisflies), Ephemeroptera (mayflies), and Diptera (true flies), alongside crustaceans (Amphipoda) and oligochaete worms (Crassiclitellata). In contrast, the intestines of Catostomus spp. were more heavily dominated by fewer taxa such as Plecoptera, Ephemeroptera, and several diatom groups (Bacillariophyta), which suggests a more selective diet. These dietary differences found in the eukaryotic GI profiles, align with the ecological roles of each species, C. bondi as a predator of aquatic macroinvertebrates and Catostomus spp. as benthic omnivores, which highlights the influence of feeding behaviors in gut microbiomes compositions.

Discussion

Our parallel analysis of 16S and 18S rRNA gene profiles provides a first glimpse of the microbiome composition of C. bondi and Catostomus spp., and how WWTP effluent may be reshaping aquatic ecosystems through trophic levels. We observed both a shift in prokaryotic communities and a corresponding change in eukaryotic composition between the site upstream of the WWTP and those downstream. While changes in gut content composition can also be influenced by longitudinal factors such as benthic substrate variation along the river (Doretto et al., 2021), we believe these effects are likely minimal in this case, as the East Gallatin River is a fifth-order river with no major tributaries along the sampled area. Additionally, Sites 1 (upstream) and 3 (downstream), are separated by only ~250 meters with similar habitat, suggesting that differences between the sites are primarily due to the influence of the WWTP.

Prokaryotic trends above and below the WWTP effluent

The analysis of microbial communities in the intestines and stomachs revealed notable spatial and temporal variations in both alpha and beta diversity among sites that were likely driven by environmental changes in flow rate, temperature, or chemical factors, or by biological factors such as changes in prey availability. Across sampling dates for both fishes, we observed a general trend of lower alpha diversity at sites downstream of the WWTP compared to upstream sites, particularly in spring and early summer. However, the anomaly at Site 6 in October 2023, where higher average richness was recorded, highlights the need for further investigation into additional environmental factors, such as seasonal hydrological shifts, specific anthropogenic contaminants, nutrient availability, and natural microbial fluctuations. These compositional shifts found in both species have broader implications for host health. Reduced microbial diversity and shifts toward taxa adapted to high-stress environments can affect host nutrition, immune function, and overall fitness (Restivo et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Goryluk-Salmonowicz and Popowska, 2022; Thanigaivel et al., 2023).

Downstream of the WWTP at Site 3, bacterial genera such as Nitrospiria, Desulfitobacteria, and Fusobacteria were significantly enriched in the C. bondi intestines compared to the upstream site, taxa possibly associated with nutrient-enriched environments. However, it should be noted that differences in microbial abundance could reflect differences in prey item availability, with each prey item possessing their own distinct microbiome that would also be detected upon ingestion, with the gut of aquatic insects having a similar microbial signature to that of fishes (Kroetsch et al., 2020).

Desulfitobacteria is a sulfate-reducing anaerobic bacterial group capable of using sulfite, thiosulfate, and sulfur as terminal electron acceptors, and known to thrive in environments enriched with sulfur compounds such as wastewater effluents or high-nutrient environments (Flint et al., 2012; Sehnal et al., 2021; Li et al., 2024). Typically associated with sediment and wastewater environments, Desulfitobacteria can enter fish intestines through ingestion of environmental material (He et al., 2020). Given Desulfitobacteria’s known role in dehalogenation of halogenated organic compounds, which are often present in WWTP effluents, its enrichment downstream may indicate potential microbial adaptation to effluent-derived contaminants (Villemur et al., 2006). Interestingly, Desulfobulbia and Desulfobacteria were enriched at Site 1, which are also taxa involved in sulfur cycling and anaerobic metabolism. However, these taxa have been associated with relatively undisturbed aquatic environments (Yu et al., 2023). These differences suggest potential environmental influences in availability of different sulfur species up and downstream of the WWTP, and further investigation is needed to determine whether they are driven by wastewater inputs, natural habitat variation, or other ecological factors.

Nitrospiria was also enriched at Site 3 downstream of the WWTP compared to the upstream site. Nitrospiria is an aerobic nitrite-oxidizing bacterium, plays a pivotal role in nitrification by converting nitrite to nitrate (Daims and Wagner, 2018). While it is primarily associated with sediment and wastewater treatment systems, Nitrospiria has also been detected in fish gills (Mes et al., 2023) and, to a lesser extent, in fish intestines, where it may contribute to nitrogen metabolism within the gut microbiome (Roeselers et al., 2011; Mes et al., 2023). Its increased abundance at Site 3 suggests potential shifts in nutrient availability, host diet, or microbial interactions, warranting further investigation into its ecological role within fish gut microbiomes.

Finally, Fusobacteria was significantly enriched in the C. bondi intestines at Site 3. Fusobacteria are commonly found in fish microbiota and play a key role in the digestion of proteins and fermentation of amino acids (Liu et al., 2016; Luan et al., 2023). Their increased dominance in downstream sites suggests that the effluent conditions, with higher organic matter input, may be selecting for microbial populations capable of fermentative metabolism. The enriched organic content from WWTP effluent could provide a nutrient-rich environment that supports the proliferation of Fusobacteria, further contributing to the shifts in microbial composition observed at Site 3. These collective findings support previous studies indicating that wastewater effluent can impose selective pressures that shape microbial communities, resulting in distinct taxonomic profiles across locations (Yukgehnaish et al., 2020; Degregori et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023; Mills et al., 2024).

These patterns are consistent with known effects of WWTP discharge, which introduces a variety CECs including pharmaceuticals, drugs of abuse, and drug metabolites into the East Gallatin River (Bishop et al., 2020). These CECs can disrupt aquatic microbial communities by altering taxonomic composition, reducing diversity, and selecting for resistant taxa. Moreover, microbial community responses to WWTP effluent are often context-dependent, shaped by interactions among contaminant load, seasonal variation, hydrological flow, and the resilience of resident microbiota (Drury et al., 2013; Butt and Volkoff, 2019; Ruprecht et al., 2021; Mills et al., 2022; Steiner et al., 2022; Mills et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2020). The difference observed in prokaryotic microbial communities associated with fishes up and downstream of the WWTP may have broader ecosystem implications, potentially affecting nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and energy transfer through the food web.

Eukaryotic trends above and below the WWTP effluent

Many aquatic macroinvertebrates, including taxa such as mayflies (Ephemeroptera) and caddisflies (Trichoptera), are known dietary components of C. bondi (Snyder and Muth, 1990; Lee et al., 1980). Indeed, Trichoptera and Ephemeroptera were the most abundant eukaryotes found in C. bondi intestines and at all sites. However, they were least abundant directly downstream of the WWTP. Trichoptera, Ephemeroptera, and Diptera have been shown to exhibit delayed emergence, reduced abundance, and shifts in community composition when exposed to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and psychostimulants in stream mesocosms (Lee et al., 2016; Richmond et al., 2018, Richmond et al., 2019). Although we did not identify the specific drugs released from the WWTP, these findings align with our lack of detection of these sensitive taxa downstream of WWTP discharge, suggesting community structure and function may already be undergoing subtle shifts due to pharmaceutical stressors. Additionally, Trichoptera and Ephemeroptera are widely recognized as key bioindicators of freshwater ecosystem health and are core components of the widely used EPT (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, Trichoptera) index. These taxa are highly sensitive to organic pollution and habitat degradation and typically dominate macroinvertebrate communities in pristine or minimally disturbed headwaters and mountainous streams (Ab Hamid and Rawi, 2017; Tubić et al., 2024), making them useful bioindicators (Souza et al., 2024). Their lower relative abundance downstream of the WWTP confirms a decline in water quality.

Similarly, directly downstream of the WWTP the relative abundance of Tubificida (a group of oligochaete worms) and the relative abundance of Tricladida (a group of flatworms) increased in the intestines of C. bondi. These taxa are often considered pollution-tolerant organisms and their presence in higher relative abundance is associated with organic pollution, and they thrive in low-oxygen environments (Knakievicz, 2014; Tampo et al., 2021; Han and Han, 2024; Aazami et al., 2015). In contrast, at Site 6, there was an increase in Crassiclitellata (segmented worms), which contribute to sediment processing and are adapted to organic-rich environments. Some species within this group are also known to tolerate polluted conditions (Glasby et al., 2021).

Previous studies of the influent and effluent from the WWTP discharging into the East Gallatin River have identified a complex mixture of pharmaceutical contaminants, including methamphetamine, amphetamine, tramadol, codeine, EDDP, ritalinic acid, fluoxetine, oxycodone, benzoylecgonine, and methadone (Bishop et al., 2020). While research directly examining the effects of these compounds on many of the eukaryotic taxa identified in our samples remains limited, a growing body of evidence demonstrates that these contaminants can induce significant sublethal effects in freshwater invertebrates—especially polychaeta, planaria, and aquatic insects (Hird et al., 2016; Kusayama & Watanabe, 2000; Hutchinson et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Richmond et al., 2018, 2019; Marcogliese et al, 2009). The observed shifts in eukaryotic composition in both fishes are consistent with known effects of environmental pollution on aquatic food webs (Windsor et al., 2020), and further studies are needed to correlate specific CECs with the trends seen here, as well as account for seasonal variation in macroinvertebrate life cycles, which can influence fish feeding behavior and exposure to specific prey taxa based on temporal availability.

Differences between organs and fishes

Clostridia and Gammaproteobacteria were dominant in the intestines of both fishes at all sites, taxa that are commonly observed in fish gut microbiomes and known for their roles in anaerobic fermentation and nitrogen fixation and polysaccharide degradation (Minamisawa et al., 2004; Talwar et al., 2018; Sehnal et al., 2021; McKee et al., 2021; Luan et al., 2023; Rose et al., 2024). However, Gammaproteobacteria were far more abundant in Castostomidae spp. compared to C. bondi, while Bacteroidia and Clostridia dominated in the intestines of C. bondi. While we were not able to compare the two species of Castostomidae, in studies of closely related fish species across multiple systems, gut microbiomes consistently showed high overlap and shared cores, with small, inconsistent species effects that were outweighed by environmental factors like habitat, location, diet, or captivity (Baldo et al., 2015; Eichmiller et al., 2016; Sevellec et al., 2019; Härer et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Shankregowda et al., 2023), and we anticipate similar patterns between these two species.

Because the stomach is characterized by an acidic, high-turnover environment, while the intestine is more neutral, anaerobic, and host-regulated, we expected to observe significant differences between the stomach and intestine microbiome (Sun and Xu, 2021). Additionally, studies have shown that the stomach often exhibits higher microbial diversity and is dominated by fast-growing taxa such as Clostridiaceae, whereas the intestine tends to be enriched with anaerobic taxa, particularly Fusobacteriaceae (Zhang et al., 2017; Solovyev et al., 2019), and a substantial proportion of gut microbes may be transient (Yang et al., 2022; Leroux et al., 2023). Surprisingly, the microbial structure was similar between the stomach and intestines of C. bondi, though certain trends were apparent such as Bacilli being more abundant in the intestine and Bacteroidia more abundant in the stomach. These trends were not readily apparent in our data likely due to the variability found within samples of the same type, as well as variability among sites and seasons. Definitive conclusions about microbial origins and enrichment in GI organs requires further targeted sampling and experimental controls that account for dietary influence, digestion stage, and environmental exposure. Nonetheless, our study provides a valuable baseline for understanding gut microbial variability in wild benthic fish and offers an ecological framework to guide future investigations into host–microbe–environment interactions.

The primary eukaryotic community detected in both fishes were common prey items of freshwater fishes. However, a handful of parasites and other taxa were identified, such as Bivalvulida, a parasitic bivalve and Myxozoa, a parasitic Cnidarian. Additionally, several classes of diatoms from the Bacillariophyceae group, such as Naviculales, Cymbellales, and Thalassiophysales were detected. The presence of diatoms suggested that these fish are also exposed to a substantial number of primary producers reflecting a biome that includes both animal and plant-based sources.

Implications and future directions

The results of this study underscore the importance of establishing microbiome composition baselines to monitor the effects of WWTP effluent on aquatic ecosystems, particularly in terms of its impact on microbial communities and food webs. The observed reductions in microbial diversity and shifts in eukaryotic composition downstream of the WWTP highlight the potential for CECs to disrupt the ecological balance of freshwater systems. These findings have important implications for the conservation and management of aquatic environments, particularly in areas where effluent discharge is a significant source of pollution.

Future research should focus on further elucidating the CECs emerging from the WWTP effluent entering the East Gallatin River and the mechanisms by which those specific CECs impact gut microbiomes and prey composition in aquatic species, ideally in controlled environmental settings. Longitudinal studies that track these changes over time and across different seasons could provide valuable insights into the temporal dynamics of these impacts. Additionally, experimental studies that manipulate environmental conditions, such as water temperature, pH, and contaminant concentrations to identify the specific factors driving the observed changes in microbial and prey communities.

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential ecological impacts of WWTP effluent on the gut microbiomes and prey composition of benthic fish in the East Gallatin River. The findings emphasize the need for improved environmental management practices to mitigate the risks posed by CECs and protect the health and biodiversity of freshwater ecosystems.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, PRJNA1208553.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Montana State University IACUC. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MR: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CV: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded with the support of the Montana State University College of Agriculture Mini Grant.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded with the support of the Montana State University College of Agriculture Mini Grant. We extend our gratitude to the Bozeman Water Reclamation Facility for their invaluable assistance and support in obtaining effluent samples for our water testing. We also thank the private property owners for allowing us access to their land for sample collection. Special thanks to all the individuals who contributed to sample collections, dissections, and DNA extractions: Marco Nesic, Savannah Angwin, Madelaine Brown, Kyle Roessler, Courtney Scott, and Peyton Klanecky. Your efforts were instrumental in the success of this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fmars.2026.1788022.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1629523/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Aazami J. Esmaili-Sari A. Abdoli A. Sohrabi H. Van den Brink P. J. (2015). Monitoring and assessment of water health quality in the Tajan River, Iran using physicochemical, fish and macroinvertebrates indices. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng.13, 29. doi: 10.1186/s40201-015-0186-y

2

Abdulaziz Mustafa S. Al-Rudainy A. J. Salman N. M. (2024). Effect of environmental pollutants on fish health: An overview. Egyptian J. Aquat. Res.50, 225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejar.2024.02.006

3

Ab Hamid S. Rawi C. S. M. (2017). Application of aquatic insects (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera and Trichoptera) in water quality assessment of Malaysian headwater. Trop. Life Sci. Res.28, 143. doi: 10.21315/tlsr2017.28.2.11

4

Apprill A. McNally S. Parsons R. Weber L. (2015). Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microbial Ecol.75, 129–137. doi: 10.3354/ame01753

5

Baldo L. Riera J. L. Tooming-Klunderud A. Albà M. M. Salzburger W. (2015). Gut microbiota dynamics during dietary shift in eastern African cichlid fishes. PloS One10, e0127462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127462

6

Ballash G. A. Baesu A. Lee S. Mills M. C. Mollenkopf D. F. Sullivan S. M. P. et al . (2022). Fish as sentinels of antimicrobial resistant bacteria, epidemic carbapenemase genes, and antibiotics in surface water. PloS One17, e0272806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272806

7

Bishop N. Jones-Lepp T. Margetts M. Sykes J. Alvarez D. Keil D. (2020). Wastewater-based epidemiology pilot study to examine drug use in the Western United States. Sci. Total Environ.745, 140697. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140697

8

Biswas C. Maity S. Adhikari M. (2021). Pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment and their endocrine disruptive effects in fish. Proc. Zoological Soc.74, 507–522. doi: 10.1007/s12595-021-00402-5

9

Bolyen E. Rideout J. R. Dillon M. R. Bokulich N. A. Abnet C. C. Al-Ghalith G. A. et al . (2019). Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9

10

Bukola D. Zaid A. Olanlekan E. I. Falilu A. (2015). Consequences of anthropogenic activities on fish and the aquatic environment. Poultry Fisheries Wildlife Sci.3, 138. doi: 10.4172/2375-446X.1000138

11

Butt R. L. Volkoff H. (2019). Gut microbiota and energy homeostasis in fish. Front. Endocrinol.10, 9. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00009

12

Callahan B. J. McMurdie P. J. Rosen M. J. Han A. W. Johnson A. J. Holmes S. P. (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods13, 581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869

13

Comber S. Gardner M. Sörme P. Leverett D. Ellor B. (2018). Active pharmaceutical ingredients entering the aquatic environment from wastewater treatment works: A cause for concern? Sci. Total Environ.613–614, 538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.101

14

Covich A. P. Palmer M. A. Crowl T. A. (1999). The role of benthic invertebrate species in freshwater ecosystems: Zoobenthic species influence energy flows and nutrient cycling. BioScience49, 119–127. doi: 10.2307/1313537

15

Dai T. Su Z. Zeng Y. Bao Y. Zheng Y. Guo H. et al . (2023). Wastewater treatment plant effluent discharge decreases bacterial community diversity and network complexity in urbanized coastal sediment. Environ. pollut.322, 121122. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121122

16

Daims H. Wagner M. (2018). Nitrospira. Trends Microbiol.26, 462–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.001

17

Davis N. M. Proctor D. M. Holmes S. P. Relman D. A. Callahan B. J . (2018). Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome6, 226. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2

18

Doretto A. Piano E. Fenoglio S. Bona F. Crosa G. Espa P. et al . (2021). Beta-diversity and stressor specific index reveal patterns of macroinvertebrate community response to sediment flushing. Ecological Indicators, 122, 107256. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107256

19

Degregori S. Casey J. M. Barber P. H. (2021). Nutrient pollution alters the gut microbiome of a territorial reef fish. Mar. pollut. Bull.169, 112522. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112522

20

Dixon P. (2003). VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Vegetation Sci.14, 927–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2003.tb02228.x

21

Drury B. Rosi-Marshall E. Kelly J. J. (2013). Wastewater treatment effluent reduces the abundance and diversity of benthic bacterial communities in urban and suburban rivers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.79, 1897–1905. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03527-12

22

Dunham J. B. Rosenberger A. E. Thurow R. F. Dolloff C. A. Howell P. J. (2009). “ Coldwater fish in wadeable streams,” in Standard methods for sampling North American freshwater fishes ( American Fisheries Society), 1–20.

23

Egerton S. Culloty S. Whooley J. Stanton C. Ross R. P. (2018). The gut microbiota of marine fish. Front. Microbiol.9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00873

24

Eichmiller J. J. Hamilton M. Staley C. Sadowsky M. Sorensen P. (2016). Environment shapes the fecal microbiome of invasive carp species. Microbiome4, 44. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0190-1

25

Estaki M. Jiang L. Bokulich N. A. McDonald D. González A. Kosciolek T. et al . (2020). QIIME 2 enables comprehensive end-to-end analysis of diverse microbiome data and comparative studies with publicly available data. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf.70, e100. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.100

26

Flint H. J. Scott K. P. Duncan S. H. Louis P. Forano E. (2012). Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes3, 289–306. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19897

27

Gauthier J. Derome N. (2021). Evenness-richness scatter plots: A visual and insightful representation of Shannon entropy measurements for ecological community analysis. mSphere6, e01019–e01020. doi: 10.1128/msphere.01019-20

28

Glasby C. J. Erséus C. Martin P. (2021). Annelids in extreme aquatic environments: Diversity, adaptations and evolution. Diversity13, 98. doi: 10.3390/d13020098

29

Glassmeyer S. T. Furlong E. T. Kolpin D. W. Batt A. L. Benson R. Boone J. S. et al . (2017). Nationwide reconnaissance of contaminants of emerging concern in source and treated drinking waters of the United States. Sci. Total Environ.581–582, 909–922. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.004

30

Golovko O. Örn S. Sörengård M. Frieberg K. Nassazzi W. Lai F. Y. et al . (2021). Occurrence and removal of chemicals of emerging concern in wastewater treatment plants and their impact on receiving water systems. Sci. Total Environ.754, 142122. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142122

31

Goryluk-Salmonowicz A. Popowska M. (2022). Factors promoting and limiting antimicrobial resistance in the environment – Existing knowledge gaps. Front. Microbiol.13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.992268

32

Gould S. L. Winter M. J. Norton W. H. J. Tyler C. R. (2021). The potential for adverse effects in fish exposed to antidepressants in the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. Technology. 55, 16299–16312 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c04724

33

Grabicova K. Grabic R. Fedorova G. Fick J. Cerveny D. Kolarova J. et al . (2017). Bioaccumulation of psychoactive pharmaceuticals in fish in an effluent dominated stream. Water Res.124, 654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.08.018

34

Guo P. Zhang K. Ma X. He P . (2020). Clostridium species as probiotics: Potentials and challenges. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol.11, 24. doi: 10.1186/s40104-019-0402-1

35

Häder D.-P. Banaszak A. Villafañe V. González R. Helbling E. W. (2020). Anthropogenic pollution of aquatic ecosystems: Emerging problems with global implications. Sci. Total Environ.713, 136586. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136586

36

Han W. Han Q. (2024). Macrobenthic indicator species: From concept to practical applications in marine ecology. Global Ecol. Conserv.55, e03262. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2024.e03262

37

Härer A. Torres-Dowdall J. Rometsch S. J. Yohannes E. MaChado-Schiaffino G. Meyer A. (2020). Parallel and non-parallel changes of the gut microbiota during trophic diversification in repeated young adaptive radiations of sympatric cichlid fish. Microbiome8, 149. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00897-8

38

He W. J. Shi M. M. Yang P. Huang T. Yuan Q. S. Yi S. Y. et al . (2020). Novel soil bacterium strain Desulfitobacterium sp. PGC-3–9 detoxifies trichothecene mycotoxins in wheat via de-epoxidation under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Toxins12, 363. doi: 10.3390/toxins12060363

39

Hird C. Urbina M. Lewis C. Snape J. Galloway T . (2016). Fluoxetine exhibits pharmacological effects and trait-based sensitivity in a marine worm. Environmental Science & Technology, 50, 8344–8352. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b03233

40

Huang L. Wu C. Gao H. Xu C. Dai M. Huang L. et al . (2022). Bacterial multidrug efflux pumps at the frontline of antimicrobial resistance: An overview. Antibiotics11, 520. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11040520

41

Hubená P. Horký P. Grabic R. Grabicová K. Douda K. Slavík O. et al . (2021). Prescribed aggression of fishes: Pharmaceuticals modify aggression in environmentally relevant concentrations. Ecotoxicology Environ. Saf.227, 112944. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112944

42

Hunting E. R. Whatley M. H. van der Geest H. G. Mulder C. Kraak M. H. S. Breure A. M. et al . (2012). Invertebrate footprints on detritus processing, bacterial community structure, and spatiotemporal redox profiles. Freshw. Sci.31, 724–732. doi: 10.1899/11-134.1

43

Hutchinson C. Prados J. Davidson C. (2015). Persistent conditioned place preference to cocaine and withdrawal hypo-locomotion to mephedrone in the flatworm planaria. Neuroscience Letters, 593, 19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.03.021

44

Impellitteri F. Multisanti C. R. Rusanova P. Piccione G. Falco F. Faggio C. (2023). Exploring the impact of contaminants of emerging concern on fish and invertebrates’ physiology in the Mediterranean Sea. Biology12, 767. doi: 10.3390/biology12060767

45

Kasonga T. K. Coetzee M. A. A. Kamika I. Ngole-Jeme V. M. Momba M. N. B. (2021). Endocrine-disruptive chemicals as contaminants of emerging concern in wastewater and surface water: A review. J. Environ. Manage.277, 111485. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111485

46

King G. M. Judd C. Kuske C. R. Smith C. (2012). Analysis of stomach and gut microbiomes of the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) from coastal Louisiana, USA. PloS One7, e51475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051475

47

Knakievicz T. (2014). Planarians as invertebrate bioindicators in freshwater environmental quality: The biomarkers approach. Ecotoxicology Environ. Contamination9, 1–12. doi: 10.5132/eec.2014.01.001

48

Kusayama T. Watanabe S . (2000). Reinforcing effects of methamphetamine in planarians. Neuro Report, 11, 2511–2513. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00033

49

Kroetsch S. A. Kidd K. Monk W. Culp J. Compson Z. Pavey S. (2020). The effects of taxonomy, diet, and ecology on the microbiota of riverine macroinvertebrates. Ecol. Evol.10, 14000–14019. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6993

50

Lee D. S. Gilbert C. R. Hocutt C. H. Jenkins R. E. McAllister D. E. Stauffer J. R. Jr. (1980). Atlas of North American freshwater fishes (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State Museum of Natural History), 867.

51

Lee S. S. Paspalof A. Snow D. Richmond E. Rosi-Marshall E. Kelly J. (2016). Occurrence and potential biological effects of amphetamine on stream communities. Environ. Sci. Technol.50, 9727–9735. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b03717

52

Leroux N. Sylvain F.-É. Holland A. Val A. L. Derôme N. (2023). Gut microbiota of an Amazonian fish in a heterogeneous riverscape: Integrating genotype, environment, and parasitic infections. Microbiol. Spectr.11, e02755–e02722. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02755-22

53

Li Y. He Y. Guo H. Hou J. Dai S. Zhang P. et al . (2024). Sulfur-containing substances in sewers: Transformation, transportation, and remediation. J. Hazardous Materials467, 133618. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.133618

54

Li J. Ni J. Wang C. Yu Y. H. Zhang T. (2020). Different response patterns of fish foregut and hindgut microbiota to host habitats and genotypes. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res.18, 7369–7378. doi: 10.15666/aeer/1805_73697378

55

Li Y. Su Z. Dai T. Zheng Y. Chen W. Zhao Y. et al . (2023). Moderate anthropogenic disturbance stimulates versatile microbial taxa contributing to denitrification and aromatic compound degradation. Environ. Res.238, 117106. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.117106

56

Liu H. Guo X. Gooneratne R. Lai R. Zeng C. Zhan F. et al . (2016). The gut microbiome and degradation enzyme activity of wild freshwater fishes influenced by their trophic levels. Sci. Rep.6, 24340. doi: 10.1038/srep24340

57

López-Pacheco I. Silva-Núñez A. Salinas-Salazar C. Arévalo-Gallegos A. Lizarazo-Holguin L. A. Barceló D. et al . (2019). Anthropogenic contaminants of high concern: Existence in water resources and their adverse effects. Sci. Total Environ.690, 1068–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.052

58