Abstract

Introduction:

Marine tourism, as a crucial component of the marine economy, generates employment opportunities in traditional marine industries and contributes to sustainable marine economic development. Understanding the drivers and enablers of individuals' travel in marine tourism is therefore essential.

Methods:

Grounded in the ability–motivation–opportunity framework, this study examines how tourism information quality influences individuals' travel intention toward marine tourism, while considering the moderating roles of travel motivation and information literacy. To test our study model, we follow a survey research design and rely on 268 participants' data.

Results:

Our results show that tourism information quality of marine tourism is positively related to individuals' travel intention toward marine tourism. However, only information skills positively moderate the positive relationship between tourism information quality and individuals' travel intention.

Discussion:

These results highlight the importance of tourism information quality in fostering marine tourism travel intention, particularly when individuals possess strong information skills. The findings provide practical implications for social media platforms and prospective tourists. The formulation and implementation of policies in the marine tourism industry can be inspired by our findings as well.

1 Introduction

Marine tourism, encompassing a broad range of tourism, leisure, and recreational activities along coastal zones and offshore waters, has emerged as one of the fastest-growing sectors in contemporary tourism (Dimitrovski et al., 2021; Hall, 2001). It includes coastal tourism development (e.g., accommodation and restaurants), supporting infrastructure (e.g., retail businesses and activity providers), and tourism activities (e.g., cruises and diving) (Dimitrovski et al., 2021; Hall, 2001). As a strategic driver of regional economic development and employment, marine tourism is closely intertwined with other components of the marine economy, such as fisheries and transportation (Martínez Vázquez et al., 2021; Shou and Xu, 2025). Prior studies have highlighted its potential in promoting the sustainable use of marine resources and creates new opportunities for workers in traditional marine industries, such as fisheries (Winchenbach et al., 2022). However, in China, institutional and policy support for marine tourism remains relatively limited, with marine development policies historically favoring port operations and fisheries. Given the rising demand for differentiated and experiential travel, marine tourism presents both urgent practical needs and rich research value (Dimitrovski et al., 2021; Leposa, 2020).

Among tourism research topics, travel intention—individuals’ propensity or willingness to visit a particular destination—has drawn sustained scholarly attention (Hosany et al., 2020). Extant studies have identified a range of influencing factors, such as content elements in short tourism videos (Gan et al., 2023) and personal attitudes (Liu et al., 2021). However, limited research has investigated how these factors interact rather than operate in isolation. Factors from different perspectives may not act independently but instead interact and reinforce each other (Kourouthanassis et al., 2017). Understanding what drives individuals to travel, particularly in less mainstream segments like marine tourism, is crucial for stakeholders seeking to optimize destination marketing and policy support (Maghrifani et al., 2022).

Tourism is inherently an information-intensive industry (Xiang and Gretzel, 2010), where individuals rely heavily on diverse sources—especially user-generated content (UGC)—to make informed travel decisions (Hays et al., 2013; Ruan and Zhang, 2021; Zeng and Gerritsen, 2014). Its importance has grown significantly with the increasing popularity of personalized travel over traditional group tours (Kim et al., 2017). The rise of the Internet has fundamentally reshaped how information is produced, disseminated, and consumed (Buhalis and Law, 2008). Tourists now routinely engage with digital platforms throughout the entire travel journey, from planning to post-trip sharing (Amaro et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2020). Social media enables consumers and stakeholders—including suppliers, intermediaries, and regulators—to exchange information in real time (Xiang and Gretzel, 2010). Individuals’ interaction with user-generated content on social media is fundamental in triggering their intention to visit those destination as well (Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2023). UGC, given its authenticity and social influence, is widely regarded as a trustworthy reference for potential travelers (Yoo and Gretzel, 2011; Wang et al., 2022). UGC related to tourism on social media assists individuals in developing travel plans and making travel decisions (Xiang and Gretzel, 2010).

Nonetheless, the increasing volume and complexity of content on social media has also led to new challenges. Information overload and decision fatigue are rising concerns, particularly when content is filtered through algorithmic systems that emphasize emotional appeal and idealized experiences (Zhang et al., 2023). This overexposure to information can lead to cognitive overload and contribute to negative perceptions of travel (Jia et al., 2021). Such mechanisms may foster unrealistic expectations, reduce perceived replicability, and even trigger dissatisfaction when actual experiences fall short (Huang et al., 2025; Kamishima et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2023). Under such circumstances, the perceived quality of tourism information on social media—which is typically defined as the extent to which information is applicable to users’ goals in a specific context (Gorla et al., 2010)—may be undermined, thus failing to effectively motivate potential tourists. The mixed findings regarding the influence of information quality on travel intention obscure the underlying mechanisms driving individuals’ travel-related decisions. In the context of marine tourism—an emerging and increasingly popular form of tourism—the availability of information remains relatively limited compared to more traditional forms of tourism. It offers a promising avenue for exploring the actual impact of tourism information quality in individuals’ travel decision-making process.

In tourism research, the primary driving factor behind destination visits is referred to as travel intention (Woodside and Lysonski, 1989). Travel intention reflects individuals’ expectations, plans, or intentions regarding future travel behaviors and serves as a predictor of actual travel behavior (Lam and Hsu, 2006). Previous research has summarized that individuals’ intention to travel to a particular destination is influenced by a combination of push factors (e.g., novelty seeking), which trigger the initial desire to travel, and pull factors (e.g., destination image), which attract them to specific destinations that satisfy their motivations (Liu et al., 2020; Maghrifani et al., 2022). Although motivation is often considered a key factor in explaining individual behavior, findings from fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) suggest that behavior can be better explained by the combination of opportunity and/or ability factors (Yee et al., 2021). Previous studies have also emphasized that individuals must possess appropriate abilities in a given domain in order to perform certain behaviors (Hung and Petrick, 2012). Investigating the combined impact of diverse factors—both technical and non-technical—on travel intention is thus of significant theoretical and practical relevance.

To address this complexity, this study adopts the Ability–Motivation–Opportunity (AMO) framework as its theoretical foundation (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017). While prior studies have adopted theoretical models such as the stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) framework (An et al., 2021) and theory of planned behavior (Borhan et al., 2019; Sparks and Pan, 2009) to explain individual behavioral outcomes, they have largely overlooked the complex interplay between external environmental stimuli and internal psychological mechanisms. In the context of tourism, the AMO framework suggests that individuals’ travel intention is shaped by three critical factors: ability, motivation, and opportunity (Hung and Petrick, 2012). Information quality, which is typically defined as the extent to which information meets users’ objectives in a specific context (Gorla et al., 2010), contributes to individuals’ informed decision making and their satisfaction (Filieri et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2024). Within this framework, information quality—which refers to the quality of outputs produced by an information system (Wang et al., 2024)—can be conceptualized as a situational factor that potentially improves individuals’ travel intention. Overall, tourism information quality can be understood as an opportunity-enhancing factor with the potential to increase individuals’ travel intention. On this basis, the purpose of this study is to investigate the influence of tourism information quality on individuals’ travel intention in the context of marine tourism, while accounting for their motivation and ability.

Accordingly, this research makes three key theoretical contributions. First, it extends the AMO framework to the marine tourism domain, responding to recent calls to examine the interaction among ability, motivation, and opportunity (Bos-Nehles et al., 2023; Hong and Gajendran, 2018). Second, it enriches tourism research by empirically testing the influence of tourism information quality on travel intention, a topic underexplored in marine tourism settings. By considering both motivational and ability-related factors, this study helps bridge a significant gap in the literature. Third, it offers novel insights into the heterogeneity of information literacy, revealing that different dimensions (e.g., knowledge vs. skills) may have diverging impacts on behavior. Together, these contributions offer a more comprehensive understanding of how individuals process tourism information and form behavioral intentions in emerging travel domains.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1 Ability, motivation, opportunity framework

The AMO framework was first proposed by MacInnis and Jaworski (1989) within the context of information processing. The model posits that ability, motivation, and opportunity are antecedents and predictors of consumer behavior (Hung and Petrick, 2012). The role of these three factors was further examined in brand information processing in the context of advertising (MacInnis et al., 1991), where they were shown to mediate the relationship between executional cues and the communication effectiveness of advertisements.

Since its inception, the AMO framework has been applied across various research domains. In the context of consumer behavior, it has been used to explain knowledge-sharing behaviors (Jin et al., 2022) and social media usage (Guenzi and Nijssen, 2020). In the field of organizational behavior, the framework has been employed to investigate employees’ use of enterprise social media platforms (Yee et al., 2021), their resilience (Zahoor et al., 2024), and the development of enterprises competitive advantage at the organizational level (Lam et al., 2019). A common thread across these applications is the emphasis on decision-making processes influenced by the interplay of ability, motivation, and opportunity. The likelihood of a given behavior occurring is contingent on the degree to which these three factors are present. Moreover, the AMO framework is recognized for its parsimony, and the nature of the relationships among its constructs is considered to be context-dependent (Atmaja et al., 2024).

In the field of tourism, the investigation of individuals’ information processing and decision-making has long been a topic of scholarly interest. Travel intention can be viewed as an outcome of the information processing process, which is primarily influenced by the three factors outlined in the AMO framework. For instance, the AMO framework has been employed to explain individual decision-making processes, suggesting that perceived travel constraints, constraint negotiation, self-congruity, and functional congruity influence travel intention (Hung and Petrick, 2012). Furthermore, travelers’ motivation and opportunity have been found to be positively associated with their involvement with hotel social media pages, which in turn positively influences their revisit intention (Leung and Bai, 2013). Drawing on the AMO framework, previous research has also examined the impact of individuals’ perceived benefits and perceived constraints on their travel behaviors (Wang et al., 2018), reinforcing the framework’s utility in understanding the antecedents of travel intention.

Applying the AMO framework to the context of marine tourism, this study aims to construct a theoretical model to explain how tourism information quality, together with individuals’ travel motivation and information literacy, shapes their travel intention (Leung and Bai, 2013).

2.2 Opportunity: tourism information quality

Opportunity refers to situational factors that either facilitate or hinder individuals’ information processing (Leung and Bai, 2013). Prior research has conceptualized opportunity as the availability of resources such as time and money, which can positively or negatively influence the achievement of desired outcomes (MacInnis et al., 1991). A positively assessed opportunity promotes engagement in a particular behavior to attain desired goals, whereas a negatively assessed opportunity serves as a barrier that prevents individuals from achieving those goals (Atmaja et al., 2024; MacInnis et al., 1991). In tourism, social media content is regarded as a primary stimulus for evoking individuals’ travel intentions (Lu and Stepchenkova, 2015). Given that a positively assessed opportunity indicates fewer external impediments to information processing (Leung and Bai, 2013; MacInnis et al., 1991), we argue that tourism information quality—which refers to the characteristics of information that align with individuals’ expectations (Kahn et al., 2002)—serves as an opportunity-enhancing factor that can stimulate individuals’ travel intention.

In tourism, it is found that individuals tend to place trust in and form expectations about content created and shared by others, such as information regarding travel destinations (Yoo and Gretzel, 2011). Meanwhile, individuals’ impressions of products or services are shaped through their information processing of various sources, and the same informational content may be perceived differently depending on individuals’ backgrounds (Kim et al., 2017). Accordingly, when informational content is perceived as complete, accurate, relevant, and authentic, individuals are more likely to pay attention to and deeply process the information, leading to rational cognition and the formation of positive attitudes toward the destination (Wang and Yan, 2022).

Furthermore, social media can shape an individual’s impression of the destination, which in turn helps increase the possibility of them planning a trip (Kim et al., 2017). When the quality of tourism-related information positively influences various types of destination image, high-quality information also helps individuals increase their understanding of specific products or services, thereby assisting them in making informed decisions (Kim et al., 2017). As a relatively new and information-intensive tourism segment, marine tourism requires individuals to rely heavily on available information for decision-making, making it a suitable context for examining the effects of information quality (Kim et al., 2017; Xiang and Gretzel, 2010). In this regard, information quality—which refers to the quality of information based on its intrinsic characteristics (Park et al., 2007)—has been identified as a strong predictor of the credibility of information sources (Filieri et al., 2015). Accordingly, tourism information quality can be regarded as an opportunity-enhancing factor with the potential to persuade individuals and strengthen their travel intention toward marine tourism.

Due to the nearly limitless availability of information on the Internet, often accessible with minimal effort or cost (Kim et al., 2007), individuals may experience information overload and decision overload (Zhang et al., 2023). The asymmetry of tourism information—whereby individuals cannot assess the quality of tourism products or services before reaching the destination—further complicates the decision-making process (Wang and Yan, 2022). Excessive exposure to such information challenges individuals’ ability to make travel decisions and may lead to negative evaluations of travel experiences (Jia et al., 2021).

Given that individuals’ perceptions of information quality are positively associated with the importance they attach to that information (Dedeoglu, 2019), the overwhelming volume of information underscores the critical role of information quality. Previous studies have confirmed that information quality positively affects user satisfaction and purchase intention (DeLone and McLean, 1992; Ghasemaghaei and Hassanein, 2015; Park et al., 2007). Moreover, information quality can compensate for individuals’ limited tourism knowledge, enabling them to achieve their travel goals more easily and increasing their overall satisfaction (Wang et al., 2024). While tourism information quality helps address the problem of asymmetric tourism information, it also enhances individuals’ trust in the reliability of such information. In the context of tourism, trust refers to the confidence, belief, and expectations individuals hold toward a tourism destination (Wang and Yan, 2022). Individuals who trust tourism information are more likely to believe that the destination can fulfill their personal needs (Shou et al., 2023). Moreover, trust within the social media environment has been shown to increase individuals’ purchase intention and interest in purchasing behavior (Hajli, 2014; Li et al., 2020). Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Tourism information quality of marine tourism is positively related to individuals’ travel intention toward marine tourism.

2.3 Ability: information literacy

In order to perform a given behavior, individuals must possess the appropriate abilities relevant to that domain (Hung and Petrick, 2012). Because travel involves unfamiliar and novel experiences, the resulting uncertainty underscores the importance of individual information literacy (Karl, 2018). Originally, ability refers to the extent to which individuals possess the necessary resources—such as knowledge, intelligence, or financial means—to bring about a desired outcome (Leung and Bai, 2013). Adopting the concept from MacInnis et al. (1991), this study defines ability as the knowledge, skills, and beliefs that individuals possess to process information related to marine tourism.

Within the context of this study, information literacy—defined as the combination of knowledge and skills required to access, evaluate, and effectively use needed information (Bawden, 2001)—is considered the relevant ability within the AMO framework. In tourism research, information literacy emphasizes individuals’ capabilities related to the collection and processing of information (Wang et al., 2024). As individuals frequently need to gather a wide range of information to support decision-making for unfamiliar destinations—while simultaneously facing challenges such as information overload and redundancy—information literacy becomes critically important (Karl, 2018; Guan et al., 2022). Only by effectively collecting, evaluating, and utilizing reliable information can travelers ensure a satisfactory experience. It also emphasizes the significance of focusing on the context of marine tourism. Given the vast amount of information available on the Internet (Kim et al., 2007), individuals are expected to utilize useful information to make informed travel decisions and enhance their satisfaction (Filieri et al., 2015). Accordingly, information literacy is essential for supporting individuals in making appropriate choices and achieving satisfying travel outcomes (Wang et al., 2024).

However, more information does not necessarily lead to better decisions or higher satisfaction. Previous research has shown that individuals with inadequate information literacy tend to have low levels of trust in online information, which prevents them from meeting their travel planning needs (Kourouthanassis et al., 2017). Individuals lacking travel knowledge may struggle with managing emergencies, understanding travel documents, and selecting suitable destinations (Chang et al., 2019; Tsaur et al., 2010). Moreover, individuals with limited information skills may find it difficult to identify their information needs, locate necessary information, evaluate it accurately, and use it efficiently (Wang et al., 2024). In contrast, individuals with high information literacy are more likely to avoid post-decision regret and report greater satisfaction with both tourism information and travel experiences (Yan et al., 2017). Accordingly, information literacy should be regarded as a critical competence that must be cultivated to ensure a satisfactory travel experience (Wang et al., 2024).

Since information literacy provides the foundation for processing ability, high ability implies that the knowledge and skills necessary to interpret information are both present and accessible (MacInnis et al., 1991). Greater information literacy also reflects individuals’ higher self-efficacy in using information skills to address information-related problems, as well as a higher level of satisfaction with the information obtained (Wang et al., 2024). The combination of information quality as an opportunity-enhancing factor and information literacy as an individual ability can create a synergistic effect in strengthening travel intention. Specifically, individuals’ ability to access, evaluate, and effectively use needed information equips them with an advantage in transforming high-quality marine tourism information into a practical tool for planning future travel. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Information literacy moderates the relationship between tourism information quality of marine tourism and travel intention toward marine tourism, such as the relationship is stronger when information literacy is high.

2.4 Motivation: travel motivation

Motivation plays a crucial role in the decision-making process due to its influence on the direction and intensity of behavior (Bettman, 1979). Specifically, as a driving force that steers individuals toward specific goals and desirable outcomes, motivation encourages engagement and supports the decision-making process (Leung and Bai, 2013; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017). In tourism research, motivation is widely recognized as a key factor shaping individuals’ travel intention (Gnoth, 1997; Wong et al., 2018). It can be defined as the direction of individuals’ efforts and the allocation of their time and energy toward a specific task (Zahoor et al., 2024). In other words, individuals are motivated to engage in certain behaviors in order to fulfill situational needs (Maghrifani et al., 2022). Higher levels of motivation suggest that individuals are more willing to invest time and energy in identifying and processing relevant information (Leung and Bai, 2013). It should be noticed that when social platforms present content that aligns with individual interests, it is the tourism information itself that often stimulates individuals’ travel motivation (Wang and Yan, 2022). Travel motivation alone is not sufficient to directly generate travel intention (Maghrifani et al., 2022).

As a topic of significant interest in tourism research, travel motivation has been shown to directly influence individuals’ travel intentions and behaviors. However, the positive association between travel motivation and travel intention has yielded inconsistent results across studies. For instance, the motivation to seek knowledge has been found to positively influence individuals’ intention to visit wine tourism destinations, whereas the desire for escape and relaxation did not demonstrate a similar effect (Afonso et al., 2018). Furthermore, prior research suggests that individuals’ travel motivations can be fulfilled by various destinations, rather than being tied to a specific one (Jang and Cai, 2002). As such, travel motivation alone cannot consistently explain individuals’ intention to visit a particular destination. In other words, travel motivation may be associated with travel intention both directly and indirectly through the influence of other factors (Maghrifani et al., 2022). A key challenge, therefore, is to understand travel intention as a function of both internal motivations and external factors related to the specific destination (Maghrifani et al., 2022).

In tourism research, travel motivation based on the push and pull factors has been extensively studied (Jang and Wu, 2006). Push factors refer to individuals’ internal needs or desires that drive them to travel, while pull factors relate to the external attributes of a destination that attract individuals to choose it as a vacation site (Crompton, 1979; Dann, 1981). In this context, travel motivation is conceptualized as a push factor, which is essential for stimulating individuals’ intention to travel (Crompton, 1979; Dann, 1981). Information quality, considered a pull factor, conveys the attractiveness of a marine tourism destination. Accordingly, travel motivation and information quality may work in tandem—one providing the internal drive and the other delivering external appeal—to enhance individuals’ travel intentions. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Travel motivation moderates the relationship between tourism information quality of marine tourism and travel intention toward marine tourism, such as the relationship is stronger when perceptions of travel motivation are high.

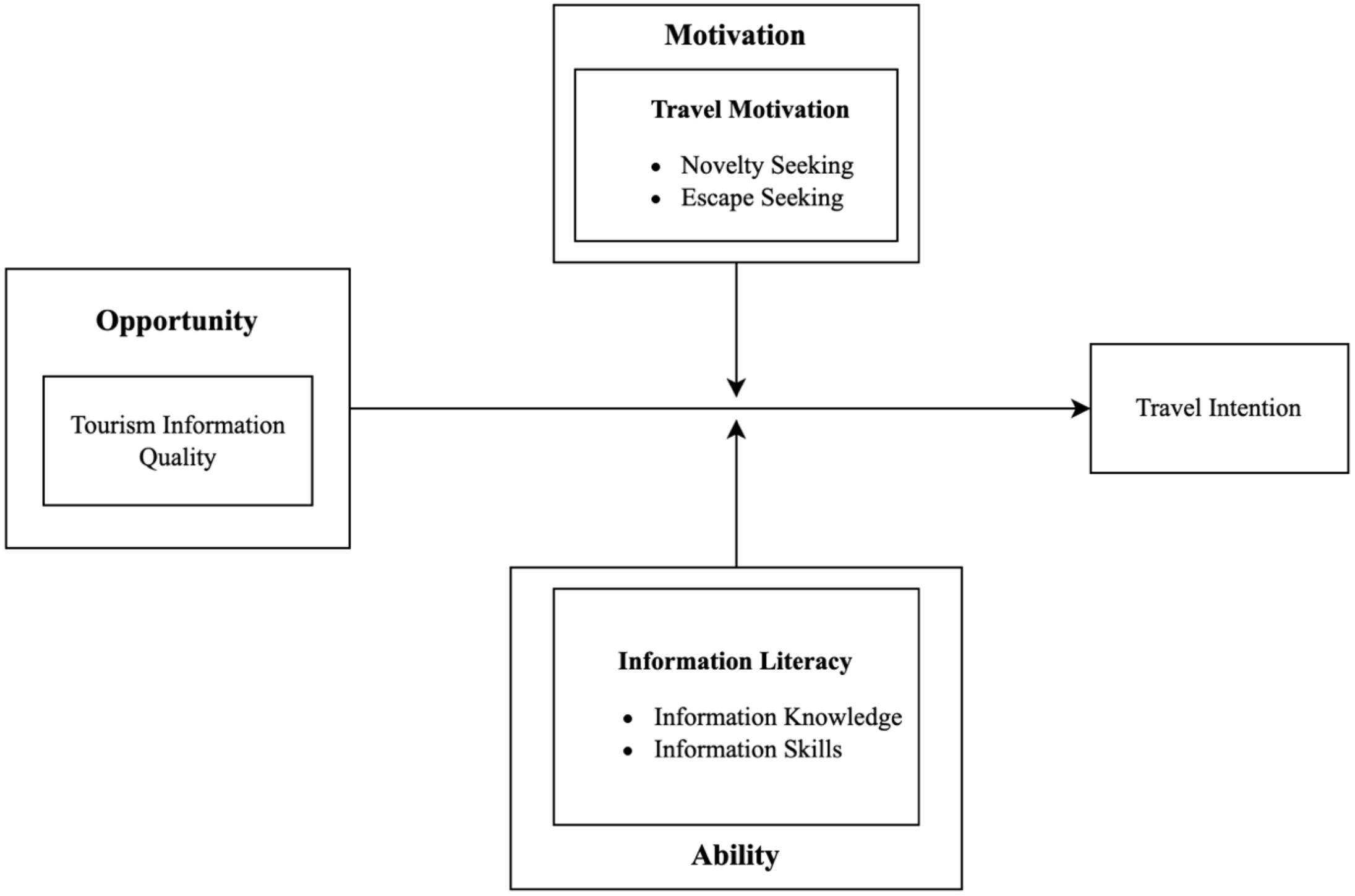

Accordingly, we develop a research model to examine how tourism information quality influences individuals’ travel intention toward marine tourism, and how travel motivation and information literacy may moderate the relationship between tourism information quality and travel intention. Figure 1 presents the proposed research model.

Figure 1

Conceptual model.

3 Methodology

3.1 Measurements

In this study, respondents scored multiple items on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We adopted appropriate existing scales (Gan et al., 2023; Maghrifani et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024) to measure tourism information quality, travel motivation, information literacy, and travel intention. The scales are also tailored to align with the specific context of this study. Specifically, the most suitable dimension of this constructs is selected. For travel motivation, as a wide range of motivation have been identified in the tourism context, this paper takes novelty seeking and escape seeking, which have been repeatedly identified, to represent travel motivation (Maghrifani et al., 2022). Novelty seeking motivation describes the need to pursue new experiences. The more familiar the destination, the less attractive it is likely to be to individuals motivated by novelty seeking (Moura et al., 2015). Engaging in marine tourism, which is an emerging and popular tourism type, should be a brand-new experience and an attractive travel for most people. Escape seeking motivation describes the need to get away from the stress of everyday life (Iso-Ahola, 1982). Individuals who take escape seeking motivation expect a socially and physically different environment from the one in which they usually live (Crompton, 1979). While activities that are related to marine tourism are far from traditional human settlements, the marine environment is also conducive to individuals’ relaxation. For information literacy, the core elements of general information literacy proposed by previous research, information knowledge and information skills, are chosen to represent information literacy (Wang et al., 2024). Information knowledge evaluates individuals’ familiarity with various travel information resources and different types of travel information (Tsaur et al., 2010). Information skills refer in particular to individuals’ ability to find, interpret, evaluate and use travel information (Ahmad et al., 2020). In addition to that, tourism information quality was composed of six items adapted from Wang et al. (2024). Travel intention was measured using three items from Gan et al. (2023). The final questionnaire is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Constructs | Subconstructs | Items | Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information Quality (IQ) (Wang et al., 2024) | IQ1 | The information about marine tourism I received on social media is timely for me to make travel decisions. | |

| IQ2 | The information about marine tourism I received on social media is understandable for me to make travel decisions. | ||

| IQ3 | The information about marine tourism I received on social media is reliable for making travel decisions. | ||

| IQ4 | The information about marine tourism I received on social media is useful for making travel decisions. | ||

| IQ5 | The information about marine tourism I received on social media is adequate for making travel decisions. | ||

| IQ6 | In general, I think the online travel information about marine tourism on social media I received is in high quality. | ||

| Information Literacy (IL) (Wang et al., 2024) | Information Knowledge (IK) | IK1 | I am familiar with various social media platforms (e.g., Rednote, Weibo). |

| IK2 | I know much about different types of travel information (e.g., weather, geo, transportation, accommodation, destination cultures). | ||

| IK3 | I know many social media platforms which provide travel information. | ||

| IK4 | I know many digital products in tourism (e.g., electronic tickets, travel insurance, customized travel route). | ||

| Information Skills (IS) | IS1 | I can find information I need from different social media platforms. | |

| IS2 | I have the ability to interpret different travel information (e.g., digital map, photos). | ||

| IS3 | I have the ability to evaluate whether the online travel information is useful to my travel decisions. | ||

| IS4 | I can use online travel information to plan my trip itinerary. | ||

| Travel Motivation (TM) (Maghrifani et al., 2022) | Novelty Seeking (NS) | NS1 | Experience different cultures and ways of life. |

| NS2 | Experience different places. | ||

| NS3 | Learn new things. | ||

| NS4 | Feel the special atmosphere of the destination. | ||

| NS5 | Meet new and different people. | ||

| Escape Seeking (ES) | ES1 | Forget about work and other responsibilities. | |

| ES2 | Relieve stress and tension. | ||

| ES3 | Forget about personal worries. | ||

| ES4 | Relax physically and mentally. | ||

| Travel Intention (TI) (Gan et al., 2023) | TI1 | I plan to visit the destinations for marine tourism in the near future. | |

| TI2 | I am willing to choose the destinations for marine tourism for my future holidays. | ||

| TI3 | Compared other similar destination, I would rather visit the destinations for marine tourism. | ||

Constructs and items.

After selecting appropriate measurements for each construct and modifying them to better align with the context of this paper, we sent the questionnaire to three experts in consumer behavior to examine the readability and improve according to the feedback. Acknowledging the variability in individuals understanding about collecting travel information on social media and marine tourism, we introduced two pivotal screening questions to filter out the useless questionnaire data. These two questions are “Have you ever used social media platforms to obtain travel information?” and “Have you ever learned about or participated in Marine tourism?”. Only those participants who understand marine tourism and experience the information collection on social media were viewed as useful respondents.

To control for potential biases, a range of control variables are examined: gender, age, education level, monthly salary, annual travel frequency, and the frequency of online tourism information search. Moreover, to mitigate common method bias associated with single-source survey data, we take two remedies. First, respondents were told that their anonymity would be protected, and they can freely present their thoughts. Second, before data collection, we discussed with three experts in consumer behavior to examine the readability. All measurements were pretested to ensure content validity and understandability.

3.2 Data collection

Data collection was executed through a leading research participants’ recruitment organization (Credamo), and 300 questionnaire responses were collected. Among them, 268 participants were classified as valid, resulting in a useful rate of 89%. Demographic insights are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| Variables | Category | Frequency (N=268) | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 168 | 62.69% |

| Female | 100 | 37.31% | |

| Age | Less than 25 years | 53 | 19.78% |

| 26 to less than 35 years | 141 | 52.61% | |

| 36 to less than 45 years | 53 | 19.78% | |

| 46 to less than 55 years | 15 | 5.60% | |

| 56 to less than 65 years | 5 | 1.87% | |

| More than 66 years | 1 | 0.37% | |

| Education levels | Middle school or below | 4 | 1.49% |

| High school | 15 | 5.60% | |

| Undergraduate | 232 | 86.57% | |

| Postgraduate | 49 | 18.28% | |

| Income | Less than 5000 yuan | 62 | 23.13% |

| 5001 to less than 8000 yuan | 72 | 26.87% | |

| 8001 to less than 15000 yuan | 94 | 35.07% | |

| 15001 to less than 30000 yuan | 39 | 14.55% | |

| More than 30001 | 1 | 0.37% |

Demographic insights.

Specifically, around 63% of the respondents were male compared to 37% female. More than 52% respondents were aged 26–35 years old, with over 90% of respondents held higher educational qualifications. Besides that, only around 15% of respondents reported monthly salary above 15000 yuan.

3.3 Data analysis

This paper applies a two-stage analytical procedure to examine the validity and reliability of the questionnaire data (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). While the first stage focuses on the evaluation of the measurement properties of the instruments, the objective of second stage is to examine the structural relationships (Srivastava and Chandra, 2018). Three types of validity, which are content validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, are examined. Content validity assesses whether the adopted measurements can comprehensively reflect the domain of the construct (Straub et al., 2004). We examined it when we designed the questionnaire and by checking the consistency between the measurements used in this paper and those in previous studies. Convergent validity discusses whether the items measuring a construct are strongly correlated (Petter et al., 2007). Since the measurements for constructs were modified based on the existing ones, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied. As illustrated in Table 3, the factor loading of items was higher than the threshold of 0.7 and the average variance extracted (AVE) was higher than the threshold of 0.5, supporting the good convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Additionally, the composite reliability was all greater than the threshold of 0.7, suggesting the good reliability of the data (Chin, 1998). Discriminant validity checks whether there is a significant difference in the measurements between different constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). As shown in Table 4, the square root of AVE all exceeded correlations between factors and other constructs, suggesting satisfactory discriminant validity.

Table 3

| Cronbach’s alpha | rho_A | Composite reliability | AVE | Indicator | Factor loading | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travel Intention | 0.701 | 0.714 | 0.834 | 0.627 | TI1 | 0.861 |

| TI2 | 0.749 | |||||

| TI3 | 0.761 | |||||

| Information Quality | 0.792 | 0.794 | 0.865 | 0.616 | IQ1 | 0.749 |

| IQ2 | – | |||||

| IQ3 | 0.815 | |||||

| IQ4 | – | |||||

| IQ5 | 0.768 | |||||

| IQ6 | 0.804 | |||||

| Information Knowledge | 0.7 | 0.725 | 0.832 | 0.624 | IK1 | – |

| IK2 | 0.701 | |||||

| IK3 | 0.826 | |||||

| IK4 | 0.835 | |||||

| Information Skills | 0.7 | 0.705 | 0.833 | 0.625 | IS1 | 0.82 |

| IS2 | – | |||||

| IS3 | 0.748 | |||||

| IS4 | 0.802 | |||||

| Novelty Seeking | 0.707 | 0.738 | 0.87 | 0.771 | NS1 | – |

| NS2 | – | |||||

| NS3 | 0.91 | |||||

| NS4 | – | |||||

| NS5 | 0.845 | |||||

| Escape Seeking | 0.714 | 0.724 | 0.839 | 0.636 | ES1 | – |

| ES2 | 0.84 | |||||

| ES3 | 0.764 | |||||

| ES4 | 0.785 |

Assessment of reliability and convergent validity.

Table 4

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Travel Intention | 0.792 | |||||

| 2 | Information Quality | 0.509 | 0.785 | ||||

| 3 | Information Knowledge | 0.452 | 0.462 | 0.79 | |||

| 4 | Information Skills | 0.441 | 0.534 | 0.576 | 0.791 | ||

| 5 | Novelty Seeking | 0.257 | 0.362 | 0.306 | 0.276 | 0.878 | |

| 6 | Escape Seeking | 0.14 | 0.136 | 0.128 | 0.278 | 0.139 | 0.797 |

Correlations and the square roots of AVE.

The bold values on the diagonal are the square roots of the AVEs. Values below the diagonal are the inter-construct correlations.

4 Results

After the confirmation of the validity and reliability of the questionnaire data, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models were applied to examine the proposed regression models. As delineated in Table 5, the linear terms of tourism information quality of marine tourism accounted for approximately 28% of the variance in individuals’ travel intention toward marine tourism. The calculated coefficients for information quality were 0.4293 (p<0.001), signifying that tourism information quality appears to positively impact individuals’ travel intention. Such findings lend empirical support to Hypothesis 1.

Table 5

| Travel Intention | |

|---|---|

| Model (1) | |

| Information Quality | 0.4293*** |

| (0.0494) | |

| Gender | 0.0411 |

| (0.0722) | |

| Age | -0.0449 |

| (0.0424) | |

| Education levels | -0.1513* |

| (0.0705) | |

| Income | 0.0627 |

| (0.0402) | |

| Cons | 3.9237*** |

| (0.3450) | |

| Number of obs. | 268 |

| Prob>F | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.2751 |

Effect of tourism information quality on individual’ travel intention.

***: P<0.001, *: P<0.05.

As illustrated in Model 2 in Table 6, it shows the results of testing the interactive effects of tourism information quality and information literacy on individuals’ travel intention. The interaction terms showed that individuals’ information literacy have a significant moderating role in the effect of tourism information quality of marine tourism on their travel intention toward marine tourism. While information skills (estimated coefficient = 0.1813, p<0.05) is positively moderating the impact of tourism information quality on individuals’ travel intention, the moderating role of information knowledge (estimated coefficient = -0.1855, p<0.05) is the opposite of the proposed hypothesis. Accordingly, the results fail to support Hypothesis 2. Furthermore, the Model 3 indicates the insignificant moderating impact of travel motivation, specifically novelty seeking (estimated coefficient = -0.0645, p>0.05) and escape seeking (estimated coefficient = -0.0112, p>0.05), on the relationship between tourism information quality and individuals’ travel intention. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 has not been confirmed.

Table 6

| Travel Intention | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model (2) | Model (3) | |

| Information Quality * Information Knowledge | -0.1855* | |

| (0.0759) | ||

| Information Quality * Information Skills | 0.1813* | |

| (0.0731) | ||

| Information Quality * Novelty Seeking | -0.0645 | |

| (0.0467) | ||

| Information Quality * Escape Seeking | -0.0112 | |

| (0.0870) | ||

| Information Quality | 0.2812 | 0.8201 |

| (0.3139) | (0.5661) | |

| Information Knowledge | 1.2674** | |

| (0.4293) | ||

| Information Skills | -0.8823* | |

| (0.4042) | ||

| Novelty Seeking | 0.3844 | |

| (0.2556) | ||

| Escape Seeking | 0.1403 | |

| (0.4857) | ||

| Gender | 0.0522 | 0.0369 |

| (0.0691) | (0.0729) | |

| Age | -0.0053 | -0.0505 |

| (0.0406) | (0.0425) | |

| Education levels | -0.1852** | -0.1428* |

| (0.0671) | (0.0712) | |

| Income | 0.0373 | 0.0605 |

| (0.0382) | (0.0408) | |

| Cons | 2.7240 | 1.1395 |

| (1.6360) | (3.1502) | |

| Number of obs. | 268 | 268 |

| Prob>F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.3626 | 0.2876 |

Moderating effect of information literacy and travel motivation on the relationship between tourism information quality and individual’ travel intention.

**: P<0.01, *: P<0.05.

5 Discussion

This study investigates how tourism information quality on social media influences individuals’ travel intention toward marine tourism, while accounting for their travel motivation and information literacy. The results confirm that higher perceived information quality is positively associated with individuals’ intention to participate in marine tourism. This supports prior findings suggesting that quality information enhances users’ trust in marine tourism information available on social media, thereby strengthening their behavioral intention. However, contrary to expectations, the hypothesized moderating effects of travel motivation and information literacy were not uniformly supported. Specifically, only information skills positively moderated the effect of tourism information quality on travel intention. Surprisingly, information knowledge demonstrated a significant negative moderating effect, while the two motivational dimensions—novelty seeking and escape seeking—showed no significant moderating effect and even indicated negative directions.

Several factors may explain the unexpected negative or insignificant moderation results. The divergence of information skills suggests that although both constructs pertain to information literacy, they may operate through distinct cognitive pathways. Regarding information knowledge, individuals with higher subjective knowledge may be more skeptical of social media content and more confident in their independent judgment, thereby weakening the influence of tourism information quality. Prior research has found that higher perceived knowledge reduces reliance on external cues, especially in familiar domains (Sharifpour et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2024). This overconfidence or selective filtering may reduce the perceived incremental value of the information quality, thereby weakening its impact on travel intention. Given that marine tourism is becoming increasingly mainstream, individuals may already possess baseline knowledge, thus reducing the marginal value of high-quality information for more informed users. In contrast, information skills—the capacity to locate, interpret, evaluate, and apply travel-related information (Ahmad et al., 2020)—enhanced the relationship between information quality and travel intention. Such competencies may enhance users’ capacity to extract value from high-quality tourism information, making them more responsive to credible and well-structured content. This suggests that individuals who are proficient in navigating the digital information environment are more capable of transforming high-quality content into actionable intentions. These findings highlight the distinction between possessing knowledge and operationalizing it effectively, reinforcing the notion that information-processing capabilities are more consequential than static knowledge in digitally mediated travel planning.

The non-significant and negative effects of travel motivation also warrant further consideration. While motivation is traditionally viewed as a key driver of travel intention, its role may vary across contexts or specific travel destination (Maghrifani et al., 2022). In this study, high novelty seekers may perceive well-structured tourism information as reducing uncertainty or spontaneity, thereby weakening destination appeal. Additionally, earlier research has noted that tourists often begin their travel planning with multiple potential destinations in mind, and that their motivations can be fulfilled by a variety of destinations (Jang and Cai, 2002). Similarly, individuals with strong escape motivations may seek emotional stimulation rather than factual detail, and thus respond less positively—or even negatively—to high levels of informational structure and completeness. These dynamics suggest that the quality cues valued by information systems may not always align with the psychological needs of different traveler types. Furthermore, since individuals’ travel motivation may be triggered by exposure to specific information (Maghrifani et al., 2022), it is likely that traditional dimensions such as novelty seeking, and escape seeking may not fully capture the core of travel motivation.

In sum, this study underscores the importance of differentiating among motivational and ability-related factors when applying the AMO framework in tourism contexts. While tourism information quality plays a central role as an enabling factor, its effectiveness is contingent upon how individuals engage with and interpret the content, both cognitively and emotionally. These findings contribute to a more nuanced understanding of how digital information systems shape behavioral intentions in emerging tourism domains such as marine tourism.

6 Contribution

6.1 Theoretical contributions

This paper makes three key theoretical contributions. First, from a theoretical perspective, the research on the integrative impact of both external environmental factor and individual factors on individuals’ travel intention is very limited. The study is one of the first attempts to explore the various factors influencing individuals’ travel intention from an integrative perspective. It also provides empirical evidence to support the use of the AMO framework in the tourism context. By investigating the combined impact of tourism information quality, information literacy and travel motivation on individuals’ travel intention, this paper responds to calls for investigating the interactive effects among ability, motivation, and opportunity (Bos-Nehles et al., 2023; Hong and Gajendran, 2018).

Second, this study advances tourism research by quantitatively examining the impact of tourism information quality on individuals’ travel intention—an area that remains underexplored in the context of marine tourism. While the role of information on social media in shaping travel intention has received considerable attention, few studies have investigated the characteristics of the information itself. By considering both motivational and ability-related factors, this study helps bridge a significant gap in the literature.

Third, the study offers nuanced insights into the heterogeneous nature of information literacy. By distinguishing between information knowledge and information skills, the findings reveal that these two dimensions can have divergent effects on individual behavior. This highlights the context-dependent nature of information literacy and provides a theoretical foundation for future research.

6.2 Practical contributions

In the current era of information explosion, the quality of information provided on social media platforms plays a crucial role in shaping individuals’ access to effective tourism content and enhancing their overall travel experiences (Li et al., 2025). The findings of this study offer several practical implications for promoting the sustainable development of marine tourism by addressing the roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders, including government, platform companies, and the tourism industry. Moreover, it also enables individuals to clearly understand the mechanism of their own tourism behaviors.

First, from a governmental perspective, policy support for tourism-related stakeholders remains relatively limited (Khalid et al., 2021). To facilitate the sustainable development of marine tourism, governments should formulate more comprehensive incentive policies. Such policies not only support industrial growth but also contribute to improving the visibility of tourist destinations, stimulating local economic development, and enriching consumers’ travel experiences (Aguinis et al., 2023; Shou and Xu, 2025). Moreover, the study highlights the significance of information environment governance. Governments are advised to implement regulatory frameworks to manage the dissemination of false or misleading content and improve the overall quality of online tourism information. Policymakers could also support the development of verified social platforms to address information asymmetry and enhance public trust through useful policies. By fostering a trustworthy and well-regulated information environment, governmental efforts can contribute to a more sustainable and competitive tourism ecosystem. In this regard, multi-level coordination among individuals, industries, and public authorities could promote long-term destination attractiveness and traveler satisfaction (Choi and Choi, 2019).

Second, platform companies—particularly social media service providers—should optimize their content presentation mechanisms. Personalizing information delivery based on user preferences can significantly enhance user engagement and platform competitiveness. Additionally, digital platforms can tailor content delivery strategies according to users’ information literacy profiles—for example, providing structured and filtered content for users with lower information skills, while allowing more exploratory options for more literate users. In addition, platforms can adopt incentive mechanisms that encourage users to generate and share high-quality content. This not only supports users in accessing reliable and meaningful travel information but also expands the role of social platforms in destination promotion and tourism marketing, especially in emerging sectors such as marine tourism.

Third, for stakeholders within the tourism industry, a deep understanding of how individual travel behaviors are influenced by the digital information environment is critical. Practitioners can enhance competitiveness by aligning marketing and service strategies with tourists’ online information-seeking behaviors. Furthermore, promoting consumers’ information literacy can empower individuals to more effectively evaluate and utilize high-quality information from platforms, thereby improving their travel decision-making processes and enriching their tourism experiences. Ultimately, the collaborative efforts of governments, platforms, and industry stakeholders can foster a more informed, engaged, and sustainable marine tourism environment.

7 Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations that open avenues for future research. First, while the joint effects of tourism information quality and information literacy on travel intention are supported, the observed interaction patterns—particularly the opposite roles of information knowledge and skills—deviate from initial expectations. Future studies should further explore these mechanisms in different tourism contexts and cultural settings. Second, this study adopts simplified measures of core constructs. Tourism information quality is treated as a unidimensional concept, and only selected aspects of travel motivation and information literacy are examined. Future research could apply more nuanced, multidimensional frameworks to capture deeper insights. Third, the generalizability of findings may be influenced by contextual and platform-specific factors. Cultural norms, such as the peer influence in collectivist settings, and tourism type, such as the uncertainty inherent in marine tourism versus urban travel, may shape how users process information. Platform differences, particularly in algorithm design and content format, can also affect perceptions of quality. Lastly, this study reflects a specific temporal context. Rapid changes in digital environments, such as the rise of short-form video and post-pandemic shifts in traveler psychology, may alter how individuals evaluate and use tourism information. These evolving conditions underscore the need to revisit and extend the proposed model in future research across diverse technological and behavioral landscapes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. YJ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. HT: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Project supported by the Key Soft Science Project of Department of Science and Technology of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2022C25050).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Afonso C. Silva G. M. Gonçalves H. M. Duarte M. (2018). The role of motivations and involvement in wine individuals’ intention to return: SEM and fsQCA findings. J. business Res.89, 313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.042

2

Aguinis H. Kraus S. Poček J. Meyer N. Jensen S. H. (2023). The why, how, and what of public policy implications of tourism and hospitality research. Tourism Manage.97, 104720. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104720

3

Ahmad F. Widén G. Huvila I. (2020). The impact of workplace information literacy on organizational innovation: An empirical study. Int. J. Inf. Manage.51, 102041. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.102041

4

Amaro S. Duarte P. Henriques C. (2016). Travelers’ use of social media: A clustering approach. Ann. Tourism Res.59, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.03.007

5

An S. Choi Y. Lee C. K. (2021). Virtual travel experience and destination marketing: Effects of sense and information quality on flow and visit intention. J. Destination Marketing Manage.19, 100492. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100492

6

Anderson J. C. Gerbing D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. psychol. Bull.103, 411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

7

Atmaja F. T. Wu C. H. J. Guttena R. K. Honora A. (2024). Intention to use telemedicine services during a health crisis: A motivation-opportunity-ability theory approach. Int. J. Consumer Stud.48, e13044. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.13044

8

Bawden D. (2001). Information and digital literacies: a review of concepts. J. documentation57, 218–259. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000007083

9

Bettman J. R. (1979). An information processing theory of consumer choice (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company).

10

Borhan M. N. Ibrahim A. N. H. Miskeen M. A. A. (2019). Extending the theory of planned behaviour to predict the intention to take the new high-speed rail for intercity travel in Libya: Assessment of the influence of novelty seeking, trust and external influence. Transportation Res. Part A: Policy Pract.130, 373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2019.09.058

11

Bos-Nehles A. Townsend K. Cafferkey K. Trullen J. (2023). Examining the ability, motivation and opportunity (AMO) framework in HRM research: Conceptualization, measurement and interactions. Int. J. Manage. Rev.25, 725–739. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12332

12

Buhalis D. Law R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism Manage.29, 609–623. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005

13

Chang K. T. Huang C. C. Tsaur S. H. (2019). Tourist geographic literacy and its consequences. Tourism Manage. Perspect.29, 131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.11.005

14

Chin W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods business Res.295, 295–336. Psychology Press.

15

Choi H. Choi H. C. (2019). Investigating tourists’ fun-eliciting process toward tourism destination sites: An application of cognitive appraisal theory. J. Travel Res.58, 732–744. doi: 10.1177/0047287518776805

16

Crompton J. L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. tourism Res.6, 408–424. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(79)90004-5

17

Dann G. M. (1981). Tourist motivation an appraisal. Ann. tourism Res.8, 187–219. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(81)90082-7

18

Dedeoglu B. B. (2019). Are information quality and source credibility really important for shared content on social media? The moderating role of gender. Int. J. Contemp. hospitality Manage.31, 513–534. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-10-2017-0691

19

DeLone W. H. McLean E. R. (1992). Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Inf. Syst. Res.3, 60–95. doi: 10.1287/isre.3.1.60

20

Dimitrovski D. Lemmetyinen A. Nieminen L. Pohjola T. (2021). Understanding coastal and marine tourism sustainability-A multi-stakeholder analysis. J. Destination Marketing Manage.19, 100554. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100554

21

Filieri R. Alguezaui S. McLeay F. (2015). Why do travelers trust TripAdvisor? Antecedents of trust towards consumer-generated media and its influence on recommendation adoption and word of mouth. Tourism Manage.51, 174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.05.007

22

Fornell C. Larcker D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J Mark Res.18 (3), 382–388. doi: 10.2307/3150980

23

Gan J. Shi S. Filieri R. Leung W. K. (2023). Short video marketing and travel intentions: The interplay between visual perspective, visual content, and narration appeal. Tourism Manag.99, 104795.

24

Ghasemaghaei M. Hassanein K. (2015). Online information quality and consumer satisfaction: The moderating roles of contextual factors–A meta-analysis. Inf. Manage.52, 965–981. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2015.07.001

25

Gnoth J. (1997). Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Ann. Tourism Res.24 (2), 283–304.

26

Gorla N. Somers T. M. Wong B. (2010). Organizational impact of system quality, information quality, and service quality. J. strategic Inf. Syst.19, 207–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsis.2010.05.001

27

Guan L. Liang H. Zhu J. J. (2022). Predicting reposting latency of news content in social media: A focus on issue attention, temporal usage pattern, and information redundancy. Comput. Hum. Behav.127, 107080. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107080

28

Guenzi P. Nijssen E. J. (2020). Studying the antecedents and outcome of social media use by salespeople using a MOA framework. Ind. Marketing Manage.90, 346–359. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.08.005

29

Hajli M. N. (2014). A study of the impact of social media on consumers. Int. J. market Res.56, 387–404. doi: 10.2501/IJMR-2014-025

30

Hall C. M. (2001). Trends in ocean and coastal tourism: the end of the last frontier? Ocean Coast. Manage.44, 601–618. doi: 10.1016/S0964-5691(01)00071-0

31

Hays S. Page S. J. Buhalis D. (2013). Social media as a destination marketing tool: its use by national tourism organisations. Curr. Issues Tourism16, 211–239. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2012.662215

32

Hong W. Gajendran R. S. (2018). Explaining dyadic expertise use in knowledge work teams: An opportunity–ability–motivation perspective. J. Organizational Behav.39, 796–811. doi: 10.1002/job.2286

33

Hosany S. Buzova D. Sanz-Blas S. (2020). The influence of place attachment, ad-evoked positive affect, and motivation on intention to visit: Imagination proclivity as a moderator. J. Travel Res.59, 477–495. doi: 10.1177/0047287519830789

34

Huang Y. Qian L. Tu H. (2025). When social media exposure backfires on travel: The role of social media–induced travel anxiety. Tourism Manage.110, 105163. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2025.105163

35

Hung K. Petrick J. F. (2012). Testing the effects of congruity, travel constraints, and self-efficacy on travel intentions: An alternative decision-making model. Tourism Manage.33, 855–867. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.09.007

36

Iso-Ahola S. E. (1982). Toward a social psychological theory of tourism motivation: A rejoinder. Ann. Tourism Res.9 (2), 256–262.

37

Jang S. Cai L. A. (2002). Travel motivations and destination choice: A study of British outbound market. J. Travel Tourism Marketing13, 111–133. doi: 10.1300/J073v13n03_06

38

Jang S. S. Wu C. M. E. (2006). Seniors’ travel motivation and the influential factors: An examination of Taiwanese seniors. Tourism Manage.27, 306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.11.006

39

Jia Y. Ouyang J. Guo Q. (2021). When rich pictorial information backfires: The interactive effects of pictures and psychological distance on evaluations of tourism products. Tourism Manage.85, 104315. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104315

40

Jiménez-Barreto J. Rubio N. Campo S. Molinillo S. (2020). Linking the online destination brand experience and brand credibility with tourists’ behavioral intentions toward a destination. Tourism Manage.79, 104101. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104101

41

Jin Y. Tan Y. Huang J. (2022). Managing contributor performance in knowledge-sharing communities: A dynamic perspective. Production Operations Manage.31, 3945–3962. doi: 10.1111/poms.13822

42

Kahn B. K. Strong D. M. Wang R. Y. (2002). Information quality benchmarks: product and service performance. Commun. ACM45, 184–192. doi: 10.1145/505248.506007

43

Kamishima T. Akaho S. Asoh H. Sakuma J. (2014). Correcting popularity bias by enhancing recommendation neutrality. RecSys posters10.

44

Karl M. (2018). Risk and uncertainty in travel decision-making: Tourist and destination perspective. J. Travel Res.57, 129–146. doi: 10.1177/0047287516678337

45

Khalid U. Okafor L. E. Burzynska K. (2021). Does the size of the tourism sector influence the economic policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic? Curr. Issues Tourism24, 2801–2820. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2021.1874311

46

Kim S. E. Lee K. Y. Shin S. I. Yang S. B. (2017). Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: The case of Sina Weibo. Inf. Manage.54, 687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2017.02.009

47

Kim D. Y. Lehto X. Y. Morrison A. M. (2007). Gender differences in online travel information search: Implications for marketing communications on the internet. Tourism Manage.28, 423–433. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.001

48

Kourouthanassis P. E. Mikalef P. Pappas I. O. Kostagiolas P. (2017). Explaining travellers online information satisfaction: A complexity theory approach on information needs, barriers, sources and personal characteristics. Inf. Manage.54, 814–824. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2017.03.004

49

Lam T. Hsu C. H. (2006). Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tourism Manage.27, 589–599. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.02.003

50

Lam H. K. Yeung A. C. Lo C. K. Cheng T. C. E. (2019). Should firms invest in social commerce? Integr. perspective. Inf. Manage.56, 103164. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2019.04.007

51

Leposa N. (2020). Problematic blue growth: A thematic synthesis of social sustainability problems related to growth in the marine and coastal tourism. Sustainability Sci.15, 1233–1244. doi: 10.1007/s11625-020-00796-9

52

Leung X. Y. Bai B. (2013). How motivation, opportunity, and ability impact travelers’ social media involvement and revisit intention. J. Travel Tourism Marketing30, 58–77. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2013.751211

53

Li L. Leung X. Y. Yang L. (2025). How tie strength and face consciousness moderate the impact of social media on impulsive travel intentions: a social-technical perspective. J. Hospitality Tourism Technol.16, 479–495. doi: 10.1108/JHTT-02-2024-0112

54

Li M. W. Teng H. Y. Chen C. Y. (2020). Unlocking the customer engagement-brand loyalty relationship in tourism social media: The roles of brand attachment and customer trust. J. Hospitality Tourism Manage.44, 184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.06.015

55

Liu X. Mehraliyev F. Liu C. Schuckert M. (2020). The roles of social media in tourists’ choices of travel components. Individ. Stud.20, 27–48. doi: 10.1177/1468797619873107

56

Liu Y. Shi H. Li Y. Amin A. (2021). Factors influencing Chinese residents' post-pandemic outbound travel intentions: An extended theory of planned behavior model based on the perception of COVID-19. Tourism Rev.76 (4), 871–891.

57

Lu W. Stepchenkova S. (2015). User-generated content as a research mode in tourism and hospitality applications: Topics, methods, and software. J. Hospitality Marketing Manage.24, 119–154. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2014.907758

58

MacInnis D. J. Jaworski B. J. (1989). Information processing from advertisements: Toward an integrative framework. J. marketing53, 1–23. doi: 10.1177/002224298905300401

59

MacInnis D. J. Moorman C. Jaworski B. J. (1991). Enhancing and measuring consumers’ motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from ads. J. marketing55, 32–53. doi: 10.2307/1251955

60

Maghrifani D. Liu F. Sneddon J. (2022). Understanding potential and repeat visitors’ travel intentions: the roles of travel motivations, destination image, and visitor image congruity. J. Travel Res.61, 1121–1137. doi: 10.1177/00472875211018508

61

Martínez Vázquez R. M. Milán García J. De Pablo Valenciano J. (2021). Analysis and trends of global research on nautical, maritime and marine tourism. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.9, 93. doi: 10.3390/jmse9010093

62

Moura F. T. Gnoth J. Deans K. R. (2015). Localizing cultural values on tourism destination websites: The effects on users’ willingness to travel and destination image. J. Travel Res.54 (4), 528–542.

63

Park D. H. Lee J. Han I. (2007). The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. electronic commerce11, 125–148. doi: 10.2753/JEC1086-4415110405

64

Petter S. Straub D. Rai A. (2007). Specifying formative constructs in information systems research. MIS Quarterly. 31, 623–656. doi: 10.2307/25148814

65

Rasoolimanesh S. M. Jaafar M. Ahmad A. G. Barghi R. (2017). Community participation in World Heritage Site conservation and tourism development. Tourism Manage.58, 142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.016

66

Ruan W. Q. Zhang S. N. (2021). Can tourism information flow enhance regional tourism economic linkages? J. Hospitality Tourism Manage.49, 614–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.11.012

67

Sharifpour M. Walters G. Ritchie B. W. Winter C. (2014). Investigating the role of prior knowledge in tourist decision making: A structural equation model of risk perceptions and information search. J. Travel Res.53, 307–322. doi: 10.1177/0047287513500390

68

Shou M. Xu J. (2025). Enhancing individuals’ engagement in marine recreational sport activities: from an institutional perspective. Front. Mar. Sci.12, 1539326. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1539326

69

Shou M. Yu J. Dai R. (2023). Identify the effect of government regulations on the live streaming e-commerce. Ind. Manage. Data Syst.123, 2909–2928. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-10-2022-0655

70

Sparks B. Pan G. W. (2009). Chinese outbound tourists: Understanding their attitudes, constraints and use of information sources. Tourism Manage.30, 483–494. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.10.014

71

Srivastava S. C. Chandra S. (2018). Social presence in virtual world collaboration: An uncertainty reduction perspective using a mixed methods approach. MIS Q.42, 779–804. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2018/11914

72

Straub D. Boudreau M. C. Gefen D. (2004). Validation guidelines for IS positivist research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst.13, 24. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.01324

73

Tsaur S. H. Yen C. H. Chen C. L. (2010). Independent tourist knowledge and skills. Ann. Tourism Res.37, 1035–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2010.04.001

74

Wang F. Deng Z. Petrick J. F. (2018). Exploring the formation mechanisms of urban residents’ travel behaviour in China: Perceptions of travel benefits and travel constraints. J. Travel Tourism Marketing35, 909–921. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2018.1445575

75

Wang Z. Huang W. J. Liu-Lastres B. (2022). Impact of user-generated travel posts on travel decisions: A comparative study on Weibo and Xiaohongshu. Ann. Tourism Res. Empirical Insights3, 100064. doi: 10.1016/j.annale.2022.100064

76

Wang R. Wu C. Wang X. Xu F. Yuan Q. (2024). E-Tourism information literacy and its role in driving individual satisfaction with online travel information: A qualitative comparative analysis. J. Travel Res.63, 904–922. doi: 10.1177/00472875231177229

77

Wang H. Yan J. (2022). Effects of social media tourism information quality on destination travel intention: Mediation effect of self-congruity and trust. Front. Psychol.13, 1049149. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1049149

78

Winchenbach A. Hanna P. Miller G. (2022). Constructing identity in marine tourism diversification. Ann. tourism Res.95, 103441. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2022.103441

79

Wong I. A. Law R. Zhao X. (2018). Time-variant pleasure travel motivations and behaviors. J. Travel Res.57, 437–452. doi: 10.1177/0047287517705226

80

Woodside A. G. Lysonski S. (1989). A general model of traveler destination choice. J. travel Res.27, 8–14. doi: 10.1177/004728758902700402

81

Xiang Z. Gretzel U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Manage.31, 179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.016

82

Xie C. Yu J. Huang S. S. Zhang K. Yang D. O. (2023). The ‘magic of filter’effect: Examining value co-destruction of social media photos in destination marketing. Tourism Manage.98, 104749. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104749

83

Yan Y. Zhang X. Zha X. Jiang T. Qin L. Li Z. (2017). Decision quality and satisfaction: the effects of online information sources and self-efficacy. Internet Res.27, 885–904. doi: 10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0089

84

Yee R. W. Miquel-Romero M. J. Cruz-Ros S. (2021). Why and how to use enterprise social media platforms: The employee’s perspective. J. business Res.137, 517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.057

85

Yoo K. H. Gretzel U. (2011). Influence of personality on travel-related consumer-generated media creation. Comput. Hum. Behav.27, 609–621. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.05.002

86

Yoo K. H. Lee Y. Gretzel U. Fesenmaier D. R. (2009). “Trust in travel-related consumer generated media,” in Information and communication technologies in tourism 2009 (Springer, Vienna), 49–59.

87

Zahoor N. Roumpi D. Tarba S. Arslan A. Golgeci I. (2024). The role of digitalization and inclusive climate in building a resilient workforce: An ability–motivation–opportunity approach. J. Organizational Behav.45, 1431–1459. doi: 10.1002/job.2800

88

Zeng B. Gerritsen R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tourism Manage. Perspect.10, 27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2014.01.001

89

Zhang X. Zhang X. Liang S. Yang Y. Law R. (2023). Infusing new insights: How do review novelty and inconsistency shape the usefulness of online travel reviews? Tourism Manage.96, 104703. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104703

90

Zhou X. Wong J. W. C. Xie D. Liang R. Huang L. (2023). What does the audience care? The effects of travel vlog information quality on travel intention. Total Qual. Manage. Business Excellence34, 2201–2219. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2023.2246908

Summary

Keywords

marine tourism, tourism information quality, travel motivation, information literacy, travel intention

Citation

Zhuge Y, Jiao Y, Tong H and Yu JJ (2025) Predicting marine tourism intention through information processing: an ability-motivation-opportunity framework. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1629706. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1629706

Received

16 May 2025

Accepted

01 August 2025

Published

28 August 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Xuemei Li, Ocean University of China, China

Reviewed by

Yufeng Zhao, Ocean University of China, China

Wen-qian Lou, Southeast University, China

Dandan Li, Zhejiang Agriculture and Forestry University, China

Lishuang Jia, Hangzhou Dianzi University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhuge, Jiao, Tong and Yu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hao Tong, hao.tong@nottingham.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.