- 1School of International Affairs and Public Administration, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China

- 2College of Management & Institute of Marine Development, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China

- 3Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation, Beijing, China

In the global governance of marine plastic pollution, the “negotiation-driven governance model” of accelerating negotiations is used in order to issue plastics treaties to deal with the problem of plastic pollution including marine plastic pollution while little empirical evidence exists concerning the participation process and strategy of native Chinese NGOs in plastics treaty negotiations. To illustrate the embeddedness strategy that native Chinese NGOs used to attract resources from social individuals and strive for a voice in the “Intergovernmental Negotiation Conference (INC), this research utilized observation method and is grounded in a series of interviews to collect the first-hand data, utilizing the Nvivo12 software with the three-phase bottom-up coding approach to analysis these interview transcripts. After a single qualitative case study under a normative bridging framework which is developed by “embeddedness” combined with network institutionalism theory, this research finds the complex and nuanced development of a native Chinese NGO in plastic treaty negotiations, it connects with social individuals by nomination under the dual registration system in China, and embeds in international affairs through side events and non-official events with the observer status. This research empirically contributes to existing network institutionalism theories through the development of a NGO normative bridging framework to illustrate the relationship between native Chinese NGOs, individuals, and international negotiations in world political and international relationship issues.

1 Introduction

The escalating crisis of marine plastic pollution has catalyzed a global call for an international binding agreement to end plastic pollution across nations. Despite the United Nations’ ambitious initiative to forge an internationally binding agreement to end plastic pollution by 2024 (United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2), 2023), the regulatory framework to combat ocean plastic pollution remains in its infancy, with a conspicuous absence of legally binding instruments. In response, Resolution (5/14) mandated the establishment of an Intergovernmental Negotiation Committee (INC) to develop a legally binding instrument addressing plastic pollution, including its marine dimensions (UNEP, 2022). This treaty is imperative to mitigate the burgeoning crisis of marine plastic pollution (Dauvergne, 2023), characterized by its ambitious, time-bound objectives and clear goals. The fifth session of the INC is scheduled to convene in Busan, Republic of Korea, from 25 November to 1 December 2024.

While states are the main addresses of international treaties, the effectiveness of these treaties relies on many other actors including NGOs (Akrofi et al., 2022). So this research advocates the increased participation for NGOs in the drafting and implementation of the global plastic treaty. This research explores how a native Chinese NGO participates in the INC series, serving as an intermediary between the public and international political issues under a normative bridging framework. The study seeks to conceptualize the normative bridging process of NGOs, guided by embeddedness and network institutionalism theories, and analyze the institutional environment, embedding network construction, challenges, and policy implications. The research addresses the following questions: In what manner dose the native Chinese NGO amplify their influence on ultimate policy results through their network-centric involvement? What mechanisms do they employ to harness network power for greater responsiveness to grassroots needs or to introduce and institutionalize new ideas and initiatives? What types of organizational pathologies emerge as a result?

To address these questions, the remainder of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces institutional institutionalism combined with embedding theory according to previous relevant research, and a normative bridging framework is developed to illustrate the institutional environment and network analysis of NGO. Section 3 presents the methodology of this research, including the case study design and data collection. Section 4 introduces the institutional environment of the case NGO including domestic and international environment. Section 5 revolves around network analysis, focusing on embedding. Section 6 discusses the challenges and implications of native Chinese NGOs in terms of embedding.

2 Literature review

2.1 Researches on network institutionalism

Network institutionalism has emerged as a pivotal theoretical framework in international relations and political science, gaining significant traction in recent years for its explanatory power in global governance and the behaviors and influence of non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

This article employs network institutionalism, as conceptualized by (Ohanyan, 2012), as a theoretical framework to bridge the study of NGOs and international relations. By integrating network theories, this approach transcends traditional intradisciplinary divides between realism and liberalism, as well as between state-centric and society-centric perspectives. According to Ohanyan (2012), network institutionalism provides a robust lens for examining NGO embeddedness within their institutional environments and networks. This article integrates institutionalism with an embeddedness framework to elucidate the central role of NGOs in international negotiations. Network analysis, a fundamental component of network institutionalism, emphasizes the structural attributes of networks, which are crucial for understanding NGO behavior (Ohanyan, 2008).

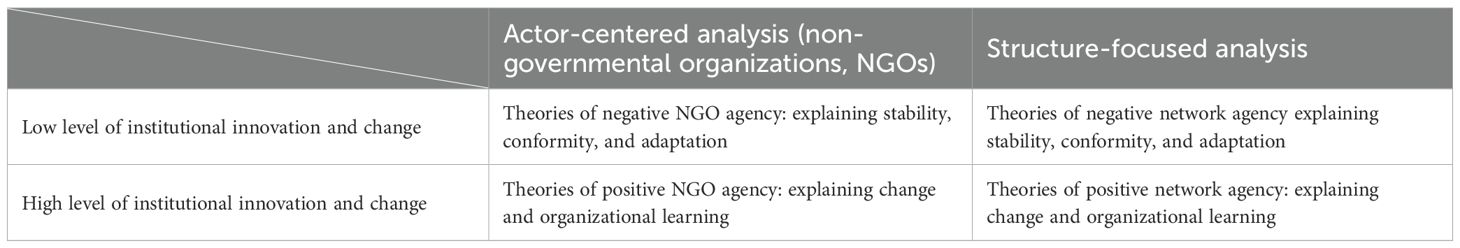

Network institutionalism focuses on specific aspects of NGO agency, such as “bridging,” and their impact on organizational fields and global governance structures. Ohanyan (2012) delineates four clusters of research areas within network institutionalism, as summarized in Table 1.

The theories of positive NGO agency, which build on extensive literature, have gained prominence with the rapid proliferation of NGOs (Reimann, 2006). NGOs influence global governance directly or indirectly by channeling latent agendas (DeMars, 2005), promoting ideas, normative frames, and material resources (Ohanyan, 2012), and gathering and disseminating information (DeMars, 2005). They also function as advocacy and lobby groups. Within this research area, NGOs introduce heterogeneity of action into global governance structures and foster the development of multisectoral networks (Benner et al., 2010).

Network institutionalism emphasizes the network position of NGOs and seeks to address several key questions through the lens of positive NGO agency: What is the systemic significance of NGOs in global governance structures? How do NGOs amplify their influence on policy outcomes through network-centric involvement? What mechanisms do they employ to harness network power for greater responsiveness to grassroots needs or to introduce and institutionalize new ideas and initiatives to donors, based on lessons learned from the field? (Ohanyan, 2012). This study simplifies these questions into “why,” “how,” and “what,” which are central to the research objectives.

Despite its theoretical and empirical advancements, network institutionalism faces notable challenges. highlights the need for refined methodologies to measure and evaluate network structures, which would enhance the framework’s explanatory rigor. Furthermore, the applicability of network institutionalism across diverse cultural contexts demands further empirical validation. (Graber, 2018) contends that future scholarship should prioritize integrating network institutionalism with other theoretical frameworks to develop more holistic analytical tools. For instance, synthesizing network institutionalism with rational choice institutionalism or historical institutionalism may yield novel theoretical insights, particularly in addressing complex transnational governance dilemmas. Network institutionalism provide a new perspective to illustrate NGOs development, however, there are insufficient empirical researches illustrating how network institutionalism connect with NGOs strategies in specific fields.

2.2 Researches on embeddedness theory

Essential theories or frameworks about the relationships between NGOs, the public, and international governance include institutionalism, social capital theory (Putnam et al., 1993), embeddedness theory (Granovetter, 1985), and network theory (Suebvises, 2018). Granovetter (1985) contends that social theories often focus on how behavior and institutions are affected by social relations and state that most behaviors are closely embedded in networks of interpersonal relations.

In world politics, there is a broad research about the bridging and associative capacities of NGOs, the associative capabilities of NGO refer to the civic action by collaborating with other actors from other organizations (Bruszt and Vedres, 2008). As for network approaches, they represent structures wherein financially and politically influential principals, such as state agencies, delegate authority to their agents, for instance, non-governmental organizations (NGOs). To that end, NGO is essential in constructing and consolidating networks in global governance. Researchers of NGOs in Institutionalism is numerous and institutionalism enables the researchers to capture the bridging characteristic of NGOs in world politics, bridging practice could help the network-based NGOs institutional their position through various mechanism: mechanistic, regulative, normative, and mimetic (Ohanyan, 2012; Scott, 2008). Mechanistic bridging is clearly characterized by the organizational functionality of NGOs within networks; regulative bridging demand NGOs to have fiduciary capacities from previous; in normative bridging, donors often try to build legitimacy by becoming involved with the NGO sector (Carlarne and Carlarne, 2006); mimetic bridging means networks and organizational fields are reproduced from different countries.

However, the existing research lack of frameworks of analysis to capture the way the NGOs interact with other nonstate and state actors and bridging. And international relationship studies seldom focus on the associative capabilities or”bridging” (DeMars and Dijkzeul, 2015). It can be supplemented by embeddedness theory, which originally referred to economics and economic behavior being affected by social networks and can be extended to the study of NGO behavior.

Embeddedness theory is derived from Polanyi’s idea of embeddedness, whose main idea is that economic action is embedded in structures of social relations in modern industrial society: “Instead of economy being embedded in social relations, social relations are embedded in the economic system” (Polanyi, 1957) and states that individuals are tightly connected to their surrounding environment (Dacin et al., 1999), economic activities should be understood within the frame of social relations, including cognition, culture, social structure, and political institutions (Zuckin and Dimaggio, 1990). In short, entrepreneurs are connected to their social surroundings, which may change their behavior (Zahra et al., 2014).

This theory creates a bridge between economics and sociology (Polanyi, 1957), and it aids in understanding NGOs’ survival strategies in international platforms. Embeddedness has been mentioned in research from different dimensions, including spatial, social, institutional, mixed, family, or other dimensions (Wigren-Kristoferson et al., 2022).

There are different types of embeddedness, including special embeddedness (Trettin and Welter, 2011); mixed embeddedness (Ram and Jones, 2008); structure embeddedness, which shifts the focus from dyadic or triadic coordination activities to the network system (Pavlovich and Kearins, 2004); relational embeddedness, which emphasizes strong/weak ties (Granovetter, 1973), trust building (Larson, 1992), and problem solving (Uzzi, 1996); political embeddedness; culture embeddedness; and knowledge embeddedness (Zuckin and Dimaggio, 1990). Previous findings have also led to the conclusion that embeddedness plays different roles depending on the life cycle stage of the entrepreneurial firm and that the complexity of embeddedness should be considered by taking into account multiple contexts at the same time (Wigren-Kristoferson et al., 2022).

Scholars in management fields introduced embeddedness theory to organization studies in order to explain the behaviors and performance of organizations, including NGOs and social organizations. Scholars deem that political embeddedness refers to the connections with government agencies (Zhou et al., 2021). In China in particular, social organizations may have a closer connection with government authorities, as most resources are commanded by the state (Shieh, 2017); however, transparency may be at a higher risk of being overlooked or disordered (Edwards and Hulme, 1996). (Hua, 2021) found that government officials increase selective information disclosure. Organization embeddedness is derived from job embeddedness theory, which deems that the “totality” and “web” of an organization and the community influence employees’ choice to remain in that organization. In terms of the motivational mechanisms of embeddedness, “two-way” embeddedness often illustrates how social organizations build close connections with the state and society (Zhang, 2012). Studies have used embeddedness to illustrate the relationship between social organizations and nations; for example, “embedded activism” has been used to characterize the relationship between environmental NGOs and the state, arguing that a loose authoritarian regime provides space for collective action by environmental organizations (Ho and Edmonds, 2008).

3 Methodology

This paper employs a qualitative case study approach to facilitate an in-depth investigation and detailed understanding of the complex and nuanced development of native Chinese NGOs in plastic treaty negotiations through observation and systematic interviews method.

3.1 Case study design and case selection

The second to fifth sessions of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-2 to INC-5), aimed at developing an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, were held from 2022 to the end of 2024. During these sessions, NGOs from various countries participated as observers, including one native Chinese NGO, referred to as Y in this research.

Y was selected as the case study for three primary reasons:

a. Historical and Experiential Relevance: Y is one of the few native Chinese NGOs with nearly 40 years of experience in environmental protection and international negotiations, making it a significant participant in the INC series.

b. Public Engagement: Y has a unique ability to build strong relationships with the public, often inviting individuals with expertise in specific fields to participate in international activities as part of its delegation.

c. Organizational Maturity: Y is a well-established NGO with numerous internship positions, a dedicated staff, and active self-media platforms, reflecting its organizational maturity and capacity for sustained engagement.

3.2 Data collection

This research is grounded in a series of interviews with 11 carefully selected participants. These interviewees were identified through literature reviews, professional networks, and referrals, ensuring their relevance to the plastic treaty negotiations and their firsthand experience with INC. This research collected 11 interview transcripts during interview process. These interviewees included professionals, UN officers, and nominees who participated in INC, providing authoritative, valuable, and reliable insights. The detailed information of these interviewees are listed as the Table 2. All interviewees were willing to participate and demonstrated the ability to articulate their ideas and opinions clearly.

In addition to interviews, the researchers conducted participant observation at Y over five months, adopting the role of a “peripheral-member-researcher” as described by Adler and Adler (1998) (1998, p. 85). This included observing Y’s participation in INC-2 (online) and INC-5 (on-site) to gain a comprehensive understanding of its engagement process. Besides that, this research collected 10 online documents including the NGOs’participation in INC on UN website, official website of government in China, and the news, policies and documents.

The interviews and observations focused on several key areas:

a. Basic job information;

b. The nomination process encountered by participants;

c. The types of resources exchanged;

d. Personal views on the participation of Chinese NGOs in international treaty negotiations;

e. The process and individual roles in INC-2 participation.

These methods provided valuable insights into how Chinese NGOs participate in INC sessions as observers, build connections with nominees, develop strategies, and navigate challenges in plastic treaty negotiations and related activities. Based on the collected data, this research presents the following findings and analysis.

By combining qualitative interviews with participant observation, this study offers a robust methodological framework for understanding the role of native Chinese NGOs in global environmental governance, particularly in the context of plastic treaty negotiations.

3.3 Data analysis

Employing textual analysis, this study examines over 120,000-word (Chinese) interview transcript, with over 20000-word (Chinese) policy documents and online news obtained through participant observation, online searching and survey research to address a classic set of questions: Who says what, to whom, why, and with what effects? Utilizing a three-phase bottom-up coding approach encompassing open coding, axial coding, and selective coding.

3.3.1 Open coding

Open coding is the initial phases of qualitative data analysis which break down the data into small units and identify the concepts, categories or themes of these data (Corbin and Strauss, 2014). Besides, researchers have adjusted several times about these concepts, to ensure the effectiveness and rationality of coding. This research has break down the interview transcripts into small units and cached 34 pieces of initial concepts, including 92 references.

3.3.2 Axial coding

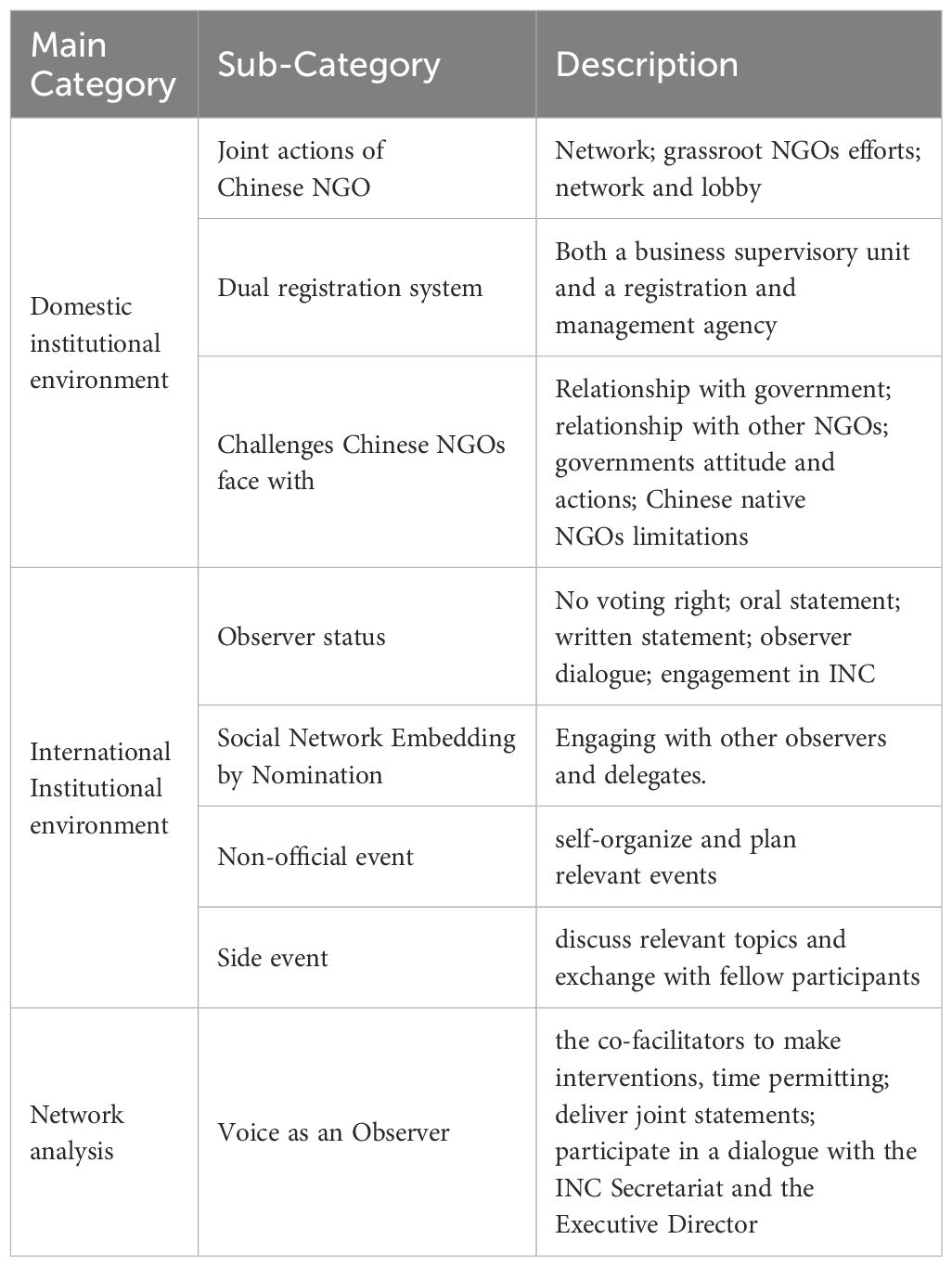

This study used NVIVO12 to perform cluster analysis on the correlation of free nodes, and based on the relationship attributes between open-coded categories. Cluster analysis clusters free nodes according to word similarity and the correlation coefficient of free nodes, which serves as a reference for classifying and summarizing free nodes and extracting and constructing sub-categories in this article. A total of 8 sub-categories were extracted and constructed. Detailed specifications are provided in Table 3.

3.3.3 Selective coding

Selective coding involves identifying a core category from the previously established categories and using it to integrate and refine all other categories, ultimately forming a coherent theoretical narrative (Belgrave and Seide, 2019). After the three-phase bottom-up coding process, this research conducted a coding process another time two months later to conduct theoretical saturation test. The inter-coder reliability test showed that Kappa = 0.823 (almost perfect agreement), and the raw percentage agreement was 87.6%, which met the consistency standard. As the Table 3. shows, this study classified all subcategories into three core concepts: domestic institutional environment; international institutional environment and network analysis.

3.4 Conceptual framework

Guided by institutionalism and network institutionalism (Ohanyan, 2008; Ohanyan, 2012), this study integrates theories of positive NGO agency with embeddedness theory to explore how a native Chinese NGO amplifies its influence in global plastic treaty negotiations. Embeddedness, closely related to the concept of social capital, highlights the role of social organizations in shaping outcomes through their social relations and constructed forms. Drawing on Tacon (2016) insights, this study examines the embeddedness of native Chinese NGOs’ social capital in international plastics treaty negotiations and explores the implications for their participation in the INC series.

This study focuses on the case of a Chinese NGO (Y), which has extensive experience in international environmental protection affairs and participates in various international treaty negotiations. NGO Y exemplifies the mediating role of NGOs in shaping plastic pollution policies and regimes, providing a valuable case for understanding the dynamics of NGO participation in global governance.

Building upon the existing body of literature on institutionalism, network institutionalism (Ohanyan, 2008; Ohanyan, 2012), and embeddedness theory (Granovetter, 1985), we identify a significant gap in the analytical frameworks that capture how NGOs interact with various actors in international politics. Moreover, there is a paucity of studies that focus on the associative capabilities of NGOs, particularly through case analyses in specific national contexts such as China. To address these gaps, this research integrates network institutionalism theory with embeddedness theory to construct a comprehensive framework. This framework elucidates how a native Chinese NGO interacts with other actors in global political processes, specifically within the context of plastic treaty negotiations, and seeks to address the fundamental questions posed by network institutionalism.

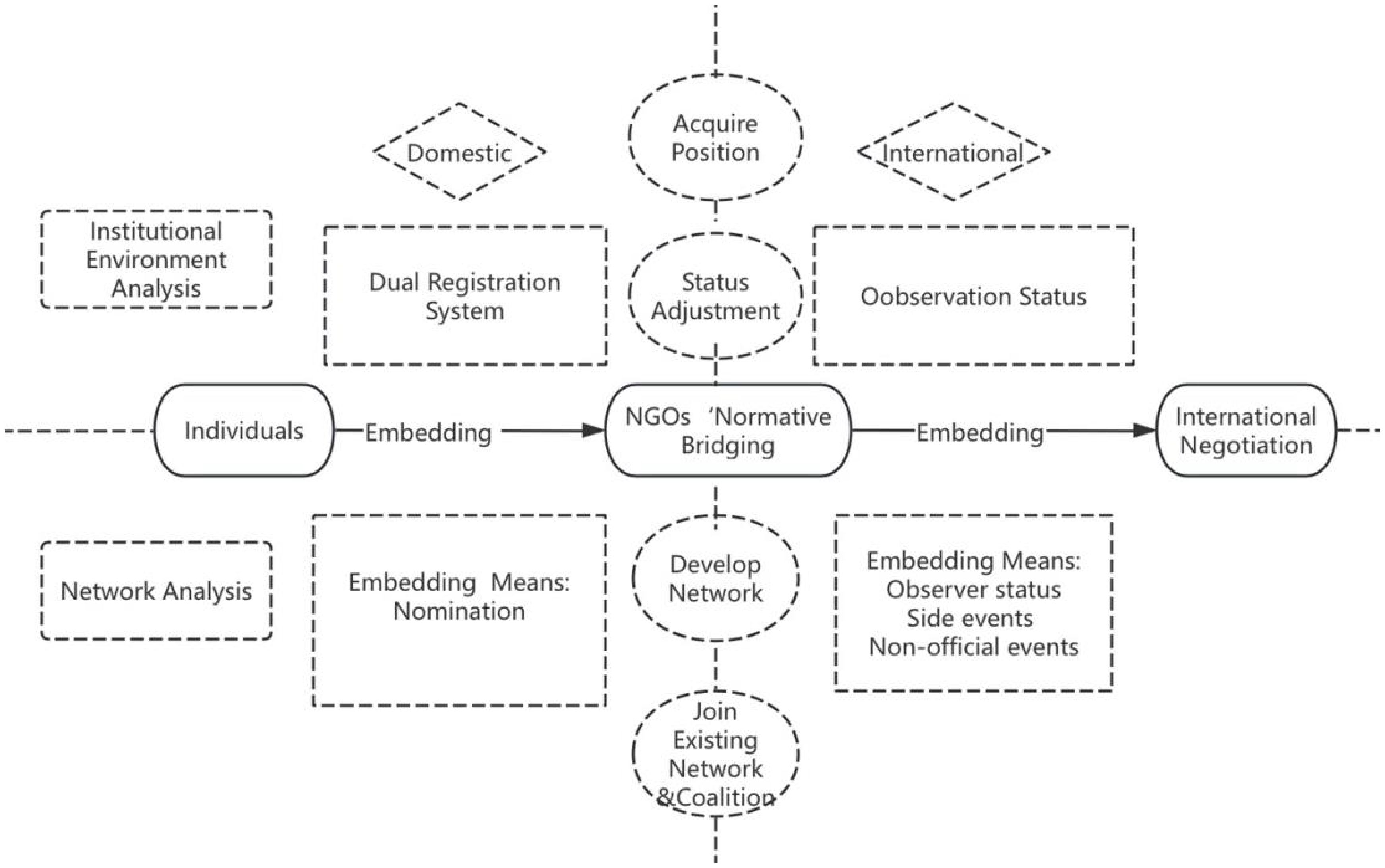

In this study, we examine how native Chinese NGOs embed themselves within international plastics treaty negotiations and influence these negotiations. Drawing on observations and prior research, we developed a framework grounded in theories of positive NGO agency and embeddedness theory. This framework is designed to address the core questions of “Why? What? How?” in the context of NGO participation in international negotiations.

Network analysis forms the cornerstone of this framework, encompassing the examination of immediate institutional environments and the networks that NGOs develop and sustain. Within this conceptual framework, NGOs are posited as “bridges” between individuals and international negotiators, suggesting that international environmental negotiations can be embedded within social networks. The concept of “bridging,” also referred to as the associative capabilities of NGOs, denotes collaboration with actors from other organizations (Bruszt and Vedres, 2008). This framework provides a robust explanation of how NGOs interact with other actors and the mechanisms they employ to do so.

By integrating these theoretical perspectives, the framework of this research not only enhances the understanding of NGO roles in international politics but also offers a nuanced lens through which to analyze the specific dynamics of native Chinese NGOs in global environmental governance. This approach underscores the importance of considering both the structural and relational dimensions of NGO activities, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of their impact on international treaty negotiations.

As the Figure 1 shows, there are two dimensions to analysis the native Chinese NGOs role in INC, one is institutional environment analysis including domestic and international environment of Y, the other is network analysis mainly about how the case native NGO work as intermediary among individuals and international negotiations, in this dimension, Y connect individuals with INC by normative bridging, these strategies include: embedding by nomination, side event, observer status and non-official events.

4 Institutional environment analysis of Y

4.1 Domestic institutional environment analysis: dual registration system

Historical, environmental and legislative contexts in the countries, cultures and communities concerned as well as the internal history and structure of each NGO could determine NGO actions and strategies (Butcher, 2007; Jamal et al., 2007). The domestic institutional environment for native Chinese NGOs can be characterized as one where “the state tolerates such groups as long as particular state agents can claim credit for any positive outcomes while avoiding accountability for any issues that may arise” (See The State Council The People’s Republic of China). To survive and operate effectively, native Chinese NGOs must navigate the dual registration system, a regulatory framework that governs social organizations in China (Hildebrandt, 2013). Under the Regulation on the Administration of the Registration of Social Organizations (2016 Revision), the establishment of social organizations requires approval from both a business supervisory unit and a registration and management agency (United Nations, 2016). The registration and management agencies include the Civil Affairs Department of the State Council and its counterparts at the county level or above, while business supervisory units are organizations authorized by these departments, such as the China Association for Science and Technology, the Ministry of Forestry, and the Social Organization Management Bureau of the Ministry of Civil Affairs.

“It should be a two-way effort (government and social organizations). The government makes decisions and can also guide the departments below on how to implement actions. We (NGO) should support the government’s strategies and policies, and then guide more people and people in society to take action…” (20230703GQ)

In 2020, the Chinese government published the Overall Plan for Comprehensively Promoting the Reform of Decoupling Industry Associations and Chambers of Commerce from Administrative Agencies (National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), 2019), aiming to decouple policies simultaneously increase nominal autonomy while maintaining party control through alternative channels. And to address issues such as the integration of management and operations, imperfect governance structures, inadequate supervision, insufficient innovation, and limited roles of industry associations and chambers of commerce. This document mandates that all qualified industry associations and chambers of commerce must be fully decoupled from administrative agencies in terms of organization, function, personnel, finance, property, party building, and publicity. This policy reflects a broader trend in China toward reducing direct state control over social organizations and fostering greater independence.

However, the state’s oversight of social organizations remains rooted in bureaucratic logic, emphasizing control over organizational resources and development (Wang and Zhang, 2019). Native Chinese NGOs must obtain approval from relevant supervision agencies before conducting international activities within China. When participating in international activities abroad, such as the INC or the United Nations Environment Conference, these NGOs operate under the identity of non-governmental organizations with observer status. This dual registration system allows them to navigate both domestic and international spheres, adapting their roles and functions according to the context. Domestically, they are subject to the constraints of Chinese laws and administrative regulations, while internationally, they enjoy greater autonomy in their operations and advocacy.

“Then, after you got the approval (under the dual registration system), although he supported you to go, he might even give you incentive funds, or you could even get reimbursement, but the conference was over…” (20231111YH)

In summary, the dual identities of native Chinese NGOs reflect the complex interplay between state control and organizational autonomy in China’s institutional environment. While they operate under the oversight of domestic regulatory bodies, they also leverage their international observer status to engage independently in global governance processes. This duality enables them to navigate the constraints of their domestic environment while contributing meaningfully to international efforts, such as the INC series on plastic pollution.

4.2 International institutional environment analysis: accredited observer status

Under the Westphalian system that shaped modern international law, participate in multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) either through informal interaction with sovereign States; or as formal participants (observers) (Spiro, 2007) and lack of direct decision-making power. For the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) series, observer status is granted not only to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with consultative status (Special, General, or Roster) under the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) but also to NGOs accredited to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and invited to participate in sessions of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA). Additionally, organizations accredited to the governing bodies of Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs) and regional environmental agreements administered by UNEP are eligible for observer status in the INC series.

The legal foundation for NGO participation in international affairs was established in Article 71 of the United Nations Charter (1945), which states: “The Economic and Social Council may make suitable arrangements for consultation with non-governmental organizations which are concerned with matters within its competence.” (UN.Charter.art.71) This provision directly legitimizes the involvement of NGOs in international negotiations, such as those for the plastics treaty. The international legal basis for NGO activities derives from the indirect provisions of international conventions, which recognize the rights of groups, including the “right to survive,” “right to self-determination,” and “right to organize” (Lindblom, 2005).

In 1996, the adoption of ECOSOC Resolution 1996/31 further formalized the consultative relationship between the United Nations and NGOs. This resolution grants NGOs the following rights:

a. Access to provisional agendas and the ability to propose items of special interest;

b. The right to designate authorized representatives to attend public meetings as observers;

c. The ability to submit written statements within their areas of expertise;

d. The entitlement to make oral presentations during meetings.

The implementation of Resolution 1996/31 led to a significant increase in the number of NGOs with consultative status, primarily due to the expanded access it provided. This resolution reinforced the role of NGOs as key stakeholders in international governance, enabling them to contribute meaningfully to global discussions and decision-making processes.

In summary, Article 71 of the UN Charter and ECOSOC Resolution 1996/31 collectively provide the legal and institutional framework for NGO participation in international affairs. However, it is important to note that few NGOs hold full or affiliate membership with voting rights in international organizations (IOs). While cooperation between IOs and NGOs is often governed by informal practices, exceptions such as the ECOSOC program demonstrate the potential for structured engagement. These informal practices afford IOs considerable discretion in defining the scope and nature of NGO involvement.

“If there are opportunities for NGOs to express opinions during the conference, we (Organization Y) will actively strive for them … If there is no opportunity to express ourselves, we will leave a message online in the background and strive to have a voice.” (20230703GQ)

“Observers are encouraged to deliver joint statements on behalf of coalitions, groups, or alliances.” (20250126ZW)

Despite their sociological legitimacy and recognition as actors with legal personality, NGOs remain secondary or derivative subjects in international law, as their legal standing is derived from states rather than being original or independent. This status underscores the complex and evolving role of NGOs in global governance, where they serve as critical intermediaries between states, international organizations, and civil society, yet operate within a framework shaped by state-centric legal structures.

5 Network analysis——embeddedness in public and international treaties negotiation

5.1 Social network embedding by nomination

Nomination in NGO is the process of selecting a candidate to represent it to fill organizational roles, particularly for international representation and this participatory approach both expands institutional capacity and enhances legitimacy in multilateral forums like the UN (Brinkerhoff, 2002). In international negotiations, NGOs may recruit volunteers for UN roles through nomination process, this process could influence policy and offer visibility to these nominees (Betsill and Corell, 2017). In UN-affiliated environmental work, nomination process of NGO could balance organizational control with the need for expertise and legitimacy (Tallberg et al., 2013).

For example, Y relies on the work of volunteers to assume international conference participant roles and calls on individuals and institutions to nominate themselves or their peers to assume various roles for the organization. These positions offer opportunities for individuals and enhance the prestige of institutional partners in international affairs in UN include the INC series. All ensure that Y can fulfill its mission to advance environment friendly career on the UN system and international affairs. Y and its participation in the INC series on plastics treaties offers an innovative perspective on network embedding.

NGOs, particularly advocacy-oriented ones, often prioritize the cultivation of networks, as these networks significantly influence their behavior and effectiveness. By joining existing coalitions, developing new networks, and acquiring strategic positions within these networks, NGOs can amplify their impact on policy outcomes. These networks enhance NGOs’ capacity to secure funding, expand their engagement on critical issues, increase global mobility, and improve organizational performance. Furthermore, embedding within such networks elevates NGOs’ institutional positions within global governance structures, enabling them to exert greater influence on international policy agendas.

The nomination process effectively embeds the public’s professional knowledge, financial resources, information, and scientific research into Y’s operations, establishing a reciprocal relationship between the organization and nominees. At its core, the nomination process is a mechanism for resource exchange. Y enjoys a strong international reputation and holds observer status in the INC and is authorized to form expert delegations and issue nomination letters to relevant experts, scholars, and specialists in China. Nomination process enables the volunteers to participate in INC series with early preparation, conference information and key outcomes summaries on its self-media platforms. As part of this resource exchange, the nominated experts and scholars contribute their professional knowledge and research findings to Y, cover their own participation costs, and provide firsthand insights from the INC conferences.

“(Y)as an observer, (applicants) can obtain an identity and nomination letters. Some individuals may not be eligible to participate in the INC, but because our organization qualifies, they could attend through our organization and speak on our behalf.”(20230706MS)

Nomination process allows native Chinese NGOs to overcome inherent limitations, such as constrained funding and a lack of specialized expertise, while leveraging their strengths, including their international reputation and communication capabilities. By embedding social power within their operations and facilitating resource exchange, native Chinese NGOs like Y can achieve significant impact in international plastics treaty negotiations with minimal cost.

Through these activities, Y exemplifies how native Chinese NGOs can effectively embed themselves within both public and international networks, leveraging the nomination process to maximize their influence and contribute meaningfully to global environmental governance.

In summary, nomination process represents a resource exchange mechanism that enables the embedding of civilian power into native Chinese NGOs, thereby addressing organizational shortcomings and fostering mutual benefits. This process facilitates the integration of social power—encompassing knowledge, information, and financial resources—into the operations of native Chinese NGOs. In return, these NGOs offer their UN observer status, international reputation, and logistical support, which serve as key incentives for civilian participation.

Native Chinese NGOs transform their social network resources into organizational capital, enabling them to participate effectively in the INC series. By embedding these social resources into the negotiation process, they contribute meaningfully to the development of plastics treaty agreements. This approach not only enhances the capacity of native Chinese NGOs but also enriches the global discourse on plastic pollution by incorporating diverse perspectives and expertise.

5.2 Native Chinese NGOs embedded in UN international negotiations under observer status

Focusing on native Chinese NGOs, this section examines how they embed themselves within United Nations (UN) negotiations. Various types of NGOs are eligible to participate in the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) (Observer guide of INC), including:

a. NGOs with consultative status under the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (special, general, or roster consultative status);

b. NGOs with observer status in the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and its subsidiary bodies;

c. Organizations accredited to the governing bodies of Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs) and regional environmental agreements administered by UNEP.

Among the diverse observer organizations in INC sessions, Y falls under the second category, holding observer status in UNEA and UNEP.

As accredited observers, NGO representatives like Y are required to:

a. Register for and participate in related webinars;

b. Submit written contributions to inform the INC process prior to each session;

c. Deliver statements and engage in dialogues with the INC secretariat and the UNEP Executive Director;

d. Participate in the planning and execution of both official side events and non-official activities related to plastic pollution during each session.

Native Chinese NGOs, such as Y, possess the same rights to engage in these activities. Their participation process reflects the embedding of social networks into international negotiations. During this process, Chinese NGOs integrate specialists, information, financial resources, perspectives, and public outreach into international negotiation process, leveraging their existing social networks.

There are numerous examples of Chinese native NGOs participating in international negotiations process and contribute their wisdom.

For example, In the intergovernmental negotiation process of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), The native Chinese NGOs exercise participatory rights under Article 7.6 of the Paris Agreement framework which institutionalizes participatory rights for non-state actors in COP process (Bäckstrand and Kuyper, 2017), including: a. monitor the progress of formal negotiation agendas through designated institutional channels; b. disseminate evidence-based research findings and implementation case studies through official COP platforms; and c. submit proposals to organize ancillary programming including but not limited to thematic parallel events, technical exhibitions, media briefings, and policy advocacy initiatives. For instance, during the COP 29, Chinese native NGOs holds almost half of the side events in China Pavilion (Liu et al., 2017).

Another successful case is Chinese Association on Tobacco Control, it has been tracking the progress of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) for a long time (Mamudu and Glantz, 2009). The published “Evaluation Report on Tobacco Control Legislation in Urban Public Places in China” provides empirical evidence for the “Beware of the Risks of New Tobacco Products” clause in the “Beijing Declaration” (the outcome document of the Seventh Conference of the Parties to the FCTC in 2018) (WHO FCTC, 2018). At the same time, during the 2018 COP, representatives of the association attended the conference as observers, focusing on refuting the lobbying claims of multinational tobacco companies on the “harmlessness of e-cigarettes” and supporting proposals for developing countries to strengthen tobacco advertising controls.

“Contact Groups, observers may also be invited by the co-facilitators to make interventions, time permitting.”(20250127ZJ)

Through the INC platform, Y can articulate its positions on the formulation of plastics treaties and marine plastic pollution governance on an international stage. It also provides an opportunity for Y to share China’s experiences in plastic pollution governance and marine environmental protection with a global audience. Participation in UN affairs is a critical avenue for NGOs to enhance their global reputation and operational efficiency. The INC sessions facilitate communication and collaboration among NGOs from different countries, state governmental organizations, and other small-group representatives. For instance, NGOs and specialists in the plastics field can exchange views and share the latest research findings through preparatory activities such as webinar series, which informs their statements and contributions.

5.3 Side events as a bridge between native Chinese NGOs and governments

Side events, held concurrently with each session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) series, provide a vital platform for delegates to discuss pertinent topics, exchange ideas, and foster interactive dialogue. Side events serve as critical spaces where NGOs could translate national policies into globally legible narratives. These events are co-organized by member states, the conference secretariat, and observer organizations, offering a unique opportunity for collaboration and knowledge sharing. Shortly after the conclusion of each session, the conference secretariat invites interested NGOs and other organizations to submit written applications to host side events during the next session. Priority is given to member states and observer organizations that demonstrate a strong interest and submit timely applications. The selection of co-organizers is conducted by the secretariat in consultation with the conference president, taking into account factors such as geographical balance, representativeness, and technical expertise. The final list of co-organizers is published on the conference website as part of the event schedule.

Co-organizers and hosts are responsible for the logistical coordination and execution of side events, including all associated expenses and catering arrangements. The conference secretariat provides three designated rooms for these events, ensuring a structured and professional environment for discussions.

For example, during the INC-3, side events were scheduled daily from 13:30 to 14:45 local time. These events were co-hosted by a diverse array of participants, including member states such as China and Argentina, as well as UN-Habitat stakeholders, international alliances, and NGOs like the Reloop Platform and Delterra. One notable side event focused on the theme, “Promoting Environmentally Sound Management of Plastic Waste, Including Collection, Sorting, and Recycling, and Considerations for Investments.” Such events provide a forum for cross-sectoral dialogue and collaboration, enabling participants to share best practices and innovative solutions.

Side events serve as an invaluable platform for information exchange and communication, including technique expertise and policy innovation diffusion (Betsill and Corell, 2008). However, member states often face resource constraints in hosting or participating in these events, making the involvement of NGOs both essential and highly valuable (Tallberg et al., 2013). By participating in side events, NGOs gain access to the latest advancements in plastic pollution management and can share critical information: a. domestic policy blueprints, b. pilot project outcomes, and c. public-private partnership models with member state delegates and other stakeholders. For native Chinese NGOs, these events offer a strategic opportunity to inject funding, technology, information, and policy recommendations into the negotiation process. Through active engagement in side events, native Chinese NGOs can establish informal transmission channels that convert technical findings into negotiable policy language, as well as amplify their voices, ensuring that their statements and recommendations are heard and considered in the broader discourse on plastic pollution governance.

In summary, side events create a parallel discursive space where NGOs bypass formal barriers to engage policymakers and experts (Schroeder and Lovell, 2012). Side events not only facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration but also enable native Chinese NGOs to strengthen their influence and contribute meaningfully to international environmental negotiations. Side events could show the bridging roles of NGOs which upwardly channeling local innovations into global policymaking while downwardly interpreting treaty obligations for domestic implementation (Betsill, M.M. and Corell, E., 2008). By leveraging these platforms, NGOs can bridge the gap between grassroots initiatives and governmental policymaking, fostering a more inclusive and effective approach to global environmental governance.

5.4 Non-official events as expanded channels for participation

Non-official events serve as another alternative channel through which NGOs could embed in international negotiations (Stroup and Wong, 2017). These parallel events outside formal negotiation agendas organized independently of the INC secretariat, provide a flexible and dynamic platform for observers to engage in activities and discussions related to plastic pollution. Non-official events allow native Chinese NGOs to embed their expertise, human resources, financial contributions, and research findings into the negotiation process. By organizing and participating in seminars held concurrently with the INC sessions, these NGOs create indirect channels to communicate their perspectives to diplomatic officials of member states.

A notable example is the seminar titled “Participation and Practice of Social Organizations in Plastic Pollution in China,” held on November 13, 2023, in Nairobi, Kenya, just before the official commencement of INC-3 (UNEP, 2023). This event was jointly organized by more than ten NGOs, including the World Wildlife Fund, Beijing Entrepreneurs Environmental Protection Foundation, Shenzhen Zero Waste Environmental Protection Public Welfare Development Center, and Qinghe Circular Economy and Carbon Neutrality Research Institute. The seminar also attracted high-level participation from Chinese government officials and UN representatives, such as the Director of the Science Division of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Deputy Director of the Solid Waste and Chemicals Division of China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment, and the Plastics Issue Coordinator of UNEP.

As one interviewee noted, “From my observation, this seminar was completely organized by non-governmental organizations, without the involvement of government backgrounds. Officials from the Chinese delegation and the United Nations Environment Programme participated in the meeting.” (S20240313LH)

Non-official events significantly expand the channels through which native Chinese NGOs can engage in plastics treaty negotiations. These events not only involve a diverse array of Chinese NGOs as organizers and participants but also attract key stakeholders, including Chinese government officials and UNEP representatives. As a major participant in INC-3, China’s relevant government departments sent delegates to engage with representatives from various NGOs, UN officials, business alliances, and other global stakeholders. This multi-stakeholder dialogue enabled member state delegates to hear perspectives from a wide range of fields and institutions, including foreign NGOs and scientific research organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund and Shenzhen Zero Waste. Discussions focused on sharing experiences and best practices in plastic pollution control across different countries. Additionally, representatives from the internationally renowned alliance “Break Free from Plastic” participated, further enriching the discourse.

The interviewee further emphasized, “This seminar was held during the INC-3. The unofficial seminar can make better use of the resources of the participants and facilitate better communication among various fields. The participants in the seminar pay more attention to plastic pollution.” (S20240313LH)

Organizing non-official seminars in proximity to the Conference of the Parties (COP) offers several advantages. First, it leverages the convergence of stakeholders attending the COP, enabling professionals from related fields and diverse backgrounds to participate in meaningful exchanges. Second, it enables NGOs to ‘corridor lobby’ negotiators through curated interactions unavailable in formal settings (Betsill, M.M. and Corell, E., 2008), allow NGOs to convey their views and information to policymakers effectively. These interactions also promote information sharing among stakeholders, contributing to the successful outcomes of the COP.

In summary, non-official events serve as “safe space” for native Chinese NGOs to reframe local issues into globally legible policy inputs, amplify their influence, share expertise, and engage in multi-stakeholder dialogues. By organizing and participating in these events, NGOs can bridge the gap between grassroots initiatives and high-level policymaking, fostering a more inclusive and collaborative approach to global plastic pollution governance.

6 Discussion

This analysis provides a comprehensive case study of how Chinese native NGO serve as a bridge between the public and the UN national and international. It complements previous reviews of roles of Chinese native NGOs in international negotiations. There is one potential limitation of this research, case-study authors who report on single-NGO projects may possibly have connections with the NGO’s concerned, due to the limited resources, single case study may lack of representative for the whole group of native Chinese NGOs.

This analysis of the international environments of the case shows that NGOs are increasingly active in environmental dialogues as observers, advocating for robustness and research, and their influence in international agreements is on the rise (Ben Youssef, 2024). Despite increasing participation in international affairs, the non-status of NGOs in the international sphere has created significant problems for them, the status of NGOs in international law has not yet progressed (Martens, 2003). The observer status determined that NGOs have limited power to intervene the direction of one international negotiation such as INC as well as limited room to make a difference. Native Chinese NGOs should consider their positions in international law and the basic principal in INC priorly then try to devote their wisdom in plastic treaties negotiations. The international environment analysis revels that there are still challenges for Chinese native NGOs in INC to be promoters of China’s image in international affairs.

This analysis of the national legally environment of native Chinese NGOs shows that the development of native Chinese NGOs is governed by the Regulations on the Registration and Administration of Social Organizations, which impose a dual supervision system and the principle of consent-based registration (Wang, 2024). It also can be interpreted that native Chinese NGOs originate from an authoritarian environment that places numerous constraints on them (Ho, 2008; Hildebrandt, 2013). Native Chinese NGOs have limited funding support from governments, Chinese government has neither mobilized nor prohibited the internationalization of Chinese NGOs (Li and Dong., 2018; Deng, 2019). From a more positive perspective, this regulatory framework also provides native Chinese NGOs with access to support and guidance from their superior departments, there are two institutional official funding for native Chinese NGOs, one is the South-South Co-operation Assistance Fund from the central government, the other is the official aid fund of the Department of Commerce in Yunnan Province (Wang, 2024). Organizations that align closely with the priorities of their supervising institutions often experience smoother participation in international activities, benefiting from clearer information channels and reduced bureaucratic resistance. However, for those operating outside the scope of their designated fields or lacking strong institutional backing, the path to international engagement remains fraught with challenges. In summary, while the dual supervision system and unified registration principle offer native Chinese NGOs a structured pathway to international participation, they also impose significant limitations. Addressing these constraints requires a nuanced understanding of the regulatory environment and strategic efforts to navigate bureaucratic complexities, ensuring that native Chinese NGOs can fully leverage their potential in global governance.

The network analysis of the native Chinese NGOs embeddedness in INC reveals that social networks serve as a crucial avenue for resource integration and enhance organizational communication and coordination, characterized by social effectiveness and enduring benefits (Duan, 2025). In particular, it is noteworthy that Chinese NGOs tend to depoliticize and diplomatize their international development projects, their discursive legitimation strategies emphasize a strong national identity and influence from the Chinese state (Wang, 2024). However, these organizations frequently encounter substantial capacity constraints, particularly in terms of specialized knowledge and human resources required for effective participation in complex international negotiations. The current limitations in internationalization of Chinese NGOs stem from multiple systemic factors, including: incomplete legal and policy frameworks supporting civil society development; insufficient institutional authority and mobilization capacity; structural constraints in global talent acquisition and retention. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive, long-term strategy that encompasses policy reform, financial support mechanisms, and the cultivation of a global professional mindset among domestic talent pools. The transformation of Chinese NGOs into effective participants in global governance will necessitate sustained investment and strategic capacity-building initiatives over an extended period.

7 Conclusions

China’s evolving role in global environmental governance, particularly in international plastics treaty negotiations, demonstrates a clear trajectory from passive participation to active contribution and, ultimately, to leadership initiatives. While Chinese NGOs’ involvement in such international treaty-making processes commenced relatively recently, their demonstrated enthusiasm and institutional vitality suggest significant potential for future contributions. Despite existing challenges related to political and cultural factors, the innovative approaches and growing activism of these organizations indicate their emerging importance in global governance frameworks.

This study makes significant contributions to embeddedness theory through the development of a comprehensive framework analyzing the tripartite relationship between Chinese NGOs, individual actors, and international negotiation processes. Our findings reveal that the embeddedness process of Chinese NGOs in global affairs is characterized by three distinctive features: (1) latecomer advantage, (2) institutional inclusivity, and (3) dual identity negotiation. To enhance their embeddedness in international plastics treaty negotiations, Chinese NGOs should implement the following strategic approaches:

a. Strategic utilization of new media platforms for advocacy and networking

b. Active participation in both official side events and parallel civil society forums

c. Development of comprehensive social networks with long-term collaborative potential

d. Optimization of self-media platforms for information dissemination

e. Expansion of international cooperation networks through strategic partnerships

Exploring how a native Chinese NGO participates in the INC series with an embedding role between the public and international political issues under the normative bridging framework is the main theme underpinning this work. This research illustrated NGOs bridging process with the first-hand information gathered by interview, observation to make the case fully displayed, however, more cases data would make this research more credible and persuasive. Moreover, even the INC-5.1 has closed, the plastics treaty negotiation hasn’t made an agreement. For these two reasons, it would be better that our future research should take into comprehensive consideration of each INC session and supply the practical cases of participation of other Chinese native NGOs to make the sample size increased and the observation period extended to further verify and improve the research conclusions of this study.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by OCENA UNIVERSITY OF CHINA, OUC-HM-2024-26. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GG: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. HW: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adler P. and Adler P. (1998). “Observational techniques,” in Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. Eds. Denzin N. K. and Lincoln Y. S. (Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA), 79–109.

Akrofi D. F., Shang P., and Ciesielczuk J. (2022). Reconsidering: approaches towards facilitating non-state actors' Participation in the global plastics regime. Eur. J. Legal Stud. 14, 121. doi: 10.2924/EJLS.2023.005

(2023). United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2). Available online at: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/what-you-need-know-about-plastic-pollution-resolution (Accessed August 20, 2025).

UNEP/PP/INC.3/INF/3:United nations environment programme: list of participants. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/44167/INC3ListofParticipants.pdf. (Accessed August 20, 2025).

Observer guide of INC. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/43895/INCObserversEngagementGuide.pdf. (Accessed August 20, 2025).

See The State Council The People’s Republic of China. Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202404/content_6947873.htm. (Accessed August 20, 2025).

See The State Council The People’s Republic of China. Available online at: http://english.www.gov.cn/news/202405/28/content_WS6655237bc6d0868f4e8e78c8.html. (Accessed [August 20, 2025).

UN.Charter.art.71. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/full-text. (Accessed August 20, 2025).

Bäckstrand K. and Kuyper J. W. (2017). The democratic legitimacy of orchestration: the UNFCCC, non-state actors, and transnational climate governance. Environ. Politics 26, 764–788. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2017.1323579

Belgrave L. L. and Seide K. (2019). “Coding for grounded theory,” in The SAGE handbook of current developments in grounded theory, 167–185.

Benner T., Reinicke W. H., and Witte J. M. (2010). Multisectoral networks in global governance: towards a pluralistic system of accountability. Government Opposition 39, 191–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00120.x

Ben Youssef A. (2024). The role of NGOs in climate policies: the case of Tunisia. J. Economic Behav. Organ. 220, 388–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2024.02.016

Betsill M. M. and Corell E. (2008). “Introduction to NGO diplomacy,” in NGO diplomacy: The influence of nongovernmental organizations in international environmental negotiations Cambridge: The MIT Press, vol. 1. , 1–19.

Betsill M. M. and Corell E. (2017). “NGO influence in international environmental negotiations: a framework for analysis,” in International environmental governance (London: Routledge), 453–473.

Brinkerhoff J. M. (2002). Government–nonprofit partnership: a defining framework. Public Administration Development: Int. J. Manage. Res. Pract. 22, 19–30. doi: 10.1002/pad.20

Bruszt L. and Vedres B. (2008). The politics of civic combinations. Voluntas 19, 140–160. doi: 10.1007/s11266-008-9060-1

Butcher J. (2007). Ecotourism, NGOs and Development: A Critical Analysis (New York: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9780203962077

Carlarne C. and Carlarne J. (2006). In—Credible government: legitimacy, democracy, and non-governmental organizations. Public Organiz Rev. 6, 347–371. doi: 10.1007/s11115-006-0019-7

Corbin J. and Strauss A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (Sage publications).

Dacin M.T., Beal B. D., and Ventresca M. J. (1999). The embeddedness of organizations: Dialogue & directions. J. Manage. 25, 317–356. doi: 10.1177/014920639902500304

Dauvergne P. (2023). The necessity of justice for a fair, legitimate, and effective treaty on plastic pollution. Mar. Policy 155, 105785. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105785

DeMars W. E. (2005). NGOs and Transnational Networks: Wild Cards in World Politics (Pluto Press). JSTOR.

DeMars W. E. and Dijkzeul D. (2015). Conclusion: NGO research and International Relations theory. In The NGO challenge for international relations theory (pp. 289–316). Routledge

Deng G. (2019). Trends in overseas philanthropy by Chinese foundations. VOLUNTAS: Int. J. Voluntary Nonprofit Organizations 30, 678–6915. doi: 10.1007/s11266-017-9868-7

Duan X. (2025). Political embeddedness versus social networks: influences on social work NGO policy advocacy in China – insights from the 2019 Social Work Study. Evidence Policy. doi: 10.1332/17442648Y2025D000000048

Edwards M. and Hulme D. (1996). Too close for comfort? The impact of official aid on nongovernmental organizations. World Dev. 24, 961–973. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(96)00019-8

Graber M. (2018). Institutionalism as conclusion and approach (University of Maryland Research Paper). No. 2018-12.

Granovetter M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. Am. J. sociology 78, 1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469

Granovetter M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. sociology 91, 481–510. doi: 10.1086/228311

Hildebrandt T. (2013). Social Organizations and the Authoritarian State in China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Ho P. (2008). “Self-imposed censorship and de-politicized politics in China: green activism or a colorRevolution?,” in China’s Embedded Activism: Opportunities and Constraints of a Social Movement. Eds. Ho P. and Edmonds R. (Routledge, New York), 20–43.

Ho P. and Edmonds R. L. (2008). China’s embedded activism: opportunities and constraints of a social movement. London and New York: Routledge.

Hua R. (2021). Political label and selective information disclosure: Evidence from charity foundations in China. VOLUNTAS: Int. J. Voluntary Nonprofit Organizations 32, 383–400. doi: 10.1007/s11266-020-00292-9

Jamal T., Kreuter U., and Yanosky A. (2007). Bridging organisations for sustainable development and conservation: a Paraguayan case. Int. J. Tourism Policy 1, 93–110. doi: 10.1504/IJTP.2007.015522

Larson A. (1992). Network dyads in entrepreneurial settings: A study of the governance of exchange relationships. Administrative Sci. Q., 76–104. doi: 10.2307/2393534

Li X. and Dong. Q. (2018). Chinese NGOs are ‘Going out’: history, scale, characteristics, outcomes, and barriers. Nonprofit Policy Forum 9, 1–9. doi: 10.1515/npf-2017-0038

Lindblom A.-K. (2005). Non-Governmental Organization in International Law (Cambridge University Press), 137.

Liu L., Wang P., and Wu T. (2017). The role of nongovernmental organizations in China's climate change governance. Wiley Interdiscip. Reviews: Climate Change 8, e483. doi: 10.1002/wcc.483

Mamudu H. M. and Glantz S. A. (2009). Civil society and the negotiation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Global Public Health 4, 150–168. doi: 10.1080/17441690802095355

Martens K. (2003). Examining the (Non-)Status of NGOs in international law. Indiana J. Global Legal Stud. 10. doi: 10.2979/gls.2003.10.2.1

National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). (2019). Overall Plan for Comprehensively Promoting the Reform of Decoupling Industry Associations and Chambers of Commerce from Administrative Agencies, No. 1063 [2019].

Ohanyan A. (2008). NGOs, IGOs, and the Network Mechanisms of Post-Conflict Global Governance in Microfinance (Palgrave Macmillan).

Ohanyan A. (2012). Network institutionalism and NGO studies. Int. Stud. Perspect. 4, 366–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-3585.2012.00488.x

Pavlovich K. and Kearins K. (2004). Structural embeddedness and community-building through collaborative network relationships. M@n@gement 7, 195–214. doi: 10.3917/mana.073.0195

Putnam R. D., Leonardi R., and Nonetti R. Y. (1993). “Social capital and institutional success,” in Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton University Press), 163–186.

Ram M. and Jones T. (2008). Ethnic-minority businesses in the UK: a review of research and policy developments. Environ. Plann. C: Government Policy 26, 352–374. doi: 10.1068/c0722

Reimann K. D. (2006). A view from the top: international politics, norms and the worldwide growth of NGOs. Int. Stud. Q. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00392.x

Schroeder H. and Lovell H. (2012). The role of non-nation-state actors and side events in the international climate negotiations. Climate Policy 12, 23–37. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2011.579328

Shieh S. (2017). Same bed, different dreams? The divergent pathways of foundations and grassroots NGOs in China. VOLUNTAS: Int. J. Voluntary Nonprofit Organizations 28, 1785–1811. doi: 10.1007/s11266-017-9864-y

Spiro P. J. (2007). “Non-governmental organizations and civil society,” in The Oxford Handbook of International Environmental Law, vol. 781 . Eds. Bodansky D., Brunnée J., and Hey E. (Oxford University Press).

Stroup S. S. and Wong W. H. (2017). “The authority trap: Strategic choices of international NGOs,” in The Authority Trap (Cornell University Press).

Suebvises P. (2018). Social capital, citizen participation in public administration, and public sector performance in Thailand. World Dev. 109, 236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.007

Tacon R. (2016). The organizational embeddedness of social capital: A comparative case study of two voluntary organizations. J. Economic Issues 50, 23–42. doi: 10.1080/00213624.2016.1147298

Tallberg J., Sommerer T., Squatrito T., and Jönsson C. (2013). The opening up of international organizations (Cambridge University Press).

Trettin L. and Welter F. (2011). Challenges for spatially oriented entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Regional Dev. 23, 575–602. doi: 10.1080/08985621003792988

UNEP. (2022). United Nations, Draft resolution – End plastic pollution: towards an international legally binding instrument (Nairobi: United Nations EnvironmentAssembly of the United Nations Environment Programme). 5th session. Available online at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3999257 (Accessed August 20, 2025).

United Nations. (2016). No.666[2016] of the national assembly. Available online at: https://docs.un.org/en/A/70/666.

Uzzi B. (1996). The sources and consequences of embeddedness for the economic performance of organizations: The network effect. Am. sociological Rev., 674–698. doi: 10.2307/2096399

Wang Y. (2024). Chinese NGOs “Going out”: depoliticisation and diplomatisation. J. Contemp. Asia 55, 249–275. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2024.2305916

Wang M. and Zhang X. (2019). Bidirectional embeddedness: an analytical framework for the autonomy of social organizations in community governance. J. Nantong University: Soc. Sci. 359.

WHO FCTC (2018). Beijing declaration technical annex. Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/wpro---documents/regional-committee/session-70/rcm70-5-tobacco-control-annex.pdf?sfvrsn=86bde4fc_6. (Accessed August 20, 2025).

Wigren-Kristoferson C., Brundin E., Hellerstedt K., Stevenson A., and Aggestam M. (2022). Rethinking embeddedness: a review and research agenda. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 34 (1–2), 32–56. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2021.2021298

Zahra S. A., Wright M., and Abdelgawad S. G. (2014). Contextualization and the advancement of entrepreneurship research. Int. small business J. 32, 479–500. doi: 10.1177/0266242613519807

Zhang J. (2012). From the controversy of structure to the action analysis: A literature review on the Chinese NGOs study in abroad. Chin. J. Sociology 32, 198–223.

Zhou S., Zhu J., and Zheng G. (2021). Whom you connect with matters for transparency: Board networks, political embeddedness, and information disclosure by Chinese foundations. Nonprofit Manage. Leadership 32, 9–28. doi: 10.1002/nml.21463

Keywords: network institutionalism theory, embeddedness theory, international plastics treaty negotiation, native Chinese NGOs, marine environmental sustainability

Citation: Zhao Y, Gao G and Wang H (2025) Embeddedness analysis of a native Chinese NGO participating in international plastic treaty negotiations from the perspective of network institutionalism. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1631261. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1631261

Received: 19 May 2025; Accepted: 04 August 2025;

Published: 29 August 2025.

Edited by:

Mehran Idris Khan, University of International Business and Economics, ChinaReviewed by:

Egemen Aras, Bursa Technical University, TürkiyeIbrahim Alshawabkeh, United Arab Emirates University, United Arab Emirates

Copyright © 2025 Zhao, Gao and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guangyue Gao, Z2FvZ3Vhbmd5dWVAc3R1Lm91Yy5lZHUuY24=; Huo Wang, TGluZGEud29uZ0BjYmNnZGYub3Jn

Yan Zhao

Yan Zhao Guangyue Gao2*

Guangyue Gao2*