Abstract

Can procuratorial agencies play a key role in China’s governance of marine plastic pollution (MPPG)? Within the current discussions about the legal framework of China’s MPPG, courts, marine environmental regulatory authorities, procuratorial agencies, and environmental protection organizations are typically seen as the main stakeholders. However, the role of procuratorial agencies, as the statutory entity for initiating PIL in marine environmental protection, has been significantly overlooked. This raises a range of questions including how should procuratorial agencies leverage their advantages in PIL to enhance the diversity of participants in the litigation process? What inherent challenges exist in marine environmental lawsuits? What substantive and procedural obstacles will procuratorial agencies face when engaging in MPPG-related litigation? This study argues that procuratorial agencies, by fulfilling their public interest litigation (PIL) function in marine environmental protection, can effectively improve MPPG governance. The study focuses on issues such as the unclear prerequisites for initiating MPPG-related lawsuits by procuratorial agencies, the criteria for selecting diverse litigation models, and the applicability of procuratorial agencies’ PIL in foreign-related cases.

1 Introduction

Between 1950 and 2017, global primary plastic production reached approximately 92 billion metric tons, and it is expected to increase to 340 billion metric tons by 2050 (Geyer, 2020). This surge has solidified plastic’s status as a hallmark of the Anthropocene and accelerated its accumulation in the oceans (Zalasiewicz et al., 2016). The international community has become increasingly aware of the severe consequences of marine plastic pollution, including threats to marine ecosystems, climate, and the global economy, as well as the financial burdens of cleanup efforts and ecosystem degradation (UNEP, 2021). As the world’s largest producer and consumer of plastics, China faces particularly severe challenges (Liu, 2024). According to data from China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) in 2023, plastic waste accounted for 89.8% of the country’s floating marine debris and 75.4% of seabed debris (MEE, 2024).

MPPG has become a focal point in academic discussions on international legal frameworks (Stoett et al., 2024; Xu, 2024; Yang et al., 2024). At present, the international rules governing marine plastic pollution primarily include the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which establishes the basic legal framework for global ocean governance and contains a dedicated chapter on the “Protection and Preservation of the Marine Environment,” setting out obligations for states to prevent and control marine pollution. The Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, 1972 (commonly known as the London Convention) and its 1996 Protocol represent efforts to regulate all forms of marine dumping by prohibiting the discharge of non-degradable plastic waste into the ocean. The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, through its 2019 amendment, extended regulatory control to the export of mixed, non-recyclable, and contaminated plastic waste, thereby strengthening the legal constraints on the transboundary trade in plastic waste. In addition, regional cooperation mechanisms addressing marine plastic pollution include the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean (Barcelona Convention), the Convention for the Protection, Management and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the Eastern African Region (Nairobi Convention), as well as specific international guidelines, such as the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries formulated by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, which aims to reduce the impact of “ghost gear “(abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear) on marine ecosystems. These multifaceted international efforts reflect the international community’s growing emphasis on protecting the marine environment. However, challenges—including fragmented legal regulation, unclear responsibility allocation, inadequate oversight of plastic waste transfers, and difficulties in managing plastic waste in the high seas—are becoming increasingly apparent (Wang J, 2021). While many studies emphasize international cooperation, some scholars argue that the current non-binding and fragmented legal instruments undermine compliance, making it necessary to adopt stronger legal actions at the sovereign state level (Ferraro and Failler, 2020). In November 2024, the failure to reach a legally binding global plastic management treaty during the fifth United Nations Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee meeting further highlighted the difficulty of achieving a unified and effective international framework, underscoring the urgent need for countries to address this pressing issue (CNN, 2024). In summary, the collective efforts of the international community in addressing marine plastic pollution have indeed yielded significant results, but they are also profoundly influenced by geopolitical factors. For example, the early transboundary waste trade has had spillover effects, with developed countries often seeking to maintain export channels, while developing countries have increasingly prioritized environmental protection and strengthening their domestic governance capacity (Liu, 2020). In addition, the lack of robust enforcement measures in plastic governance frameworks has further underscored the urgent need to reform the global governance mechanisms for marine plastic pollution.

The discussion on national participation in governance particularly emphasizes the need for coordinating legal actions among domestic stakeholders (Garcia et al., 2019). In China, scholars define this coordination as the collaboration between the government, enterprises, and the public, with environmental protection organizations as representatives (Yang et al., 2021). This coordination is further strengthened through the involvement of procuratorial agencies, which help to narrow the enforcement gap and provide judicial support for these actions (He, 2024). However, previous discussions on domestic stakeholders have largely overlooked the key role of the procuratorial agencies. As the litigating party in marine environmental public interest litigation (EPIL), procuratorial agencies have played a critical role in issues such as marine ecological environment and resource protection (Huang et al., 2024). The Public Interest Litigation Department of China’s Supreme People’s Procuratorate has proposed guiding the accuracy and standardization of public interest litigation handled by procuratorial agencies through the principle of “justiciability leading public interest litigation.” Regarding the connotation and determination criteria of justiciability, Chinese scholars have suggested that “justiciability refers to the attribute of a matter being capable of being resolved through litigation. Specifically, in the context of procuratorial public interest litigation, it means that when national interests and social public interests are infringed, the procuratorial agencies can, on behalf of the state and society, file a lawsuit and request the people’s court to make a lawful ruling.” At the same time, they identify the criteria of justiciability from the perspectives of subject specificity, public interest purpose, statutory scope, and procedural particularity. Under the theme of this research, the procuratorial agencies’ initiation of marine environmental public interest litigation in response to marine plastic pollution basically meets the standards of justiciability, its legal basis is primarily reflected in Article 114 of the Marine Environmental Protection Law. However, there is a gap in the involvement of procuratorial agencies in PIL related to MPPG, raising two key questions: First, can procuratorial agencies play an effective role in China’s MPPG? Second, how can procuratorial agencies identify the entry points for litigation related to MPPG?

In order to answer the above questions, the structure of this paper is as follows: The second section will investigate the legislative status of marine plastic pollution governance in China and the value of procuratorial agencies in marine plastic pollution control. The third section will discuss the theoretical and practical basis of procuratorial agencies’ involvement in marine plastic pollution control. The fourth section will discuss the specific challenges (including legal and practical difficulties) faced by procuratorial agencies participating in MPPG. Section 5 will provide corresponding suggestions. Finally, the sixth section will summarize the article and put forward the future role orientation path of procuratorial agencies.

2 China’s MPPG: legislative status and function orientation of procuratorial agencies

2.1 China’s MPPG: current legislative situation

Since the early 21st century, China has initiated regulatory measures to address MPPG. This lengthy process reflects considerable complexity. Notably, China has adopted a comprehensive approach to curb marine plastic pollution, targeting the entire plastic lifecycle—from production and consumption to disposal. The regulatory framework is characterized by a multi-level, multi-actor structure, including national policies, legislation, and local regulations. As a result, nearly all major government agencies have now issued policies related to the control and prevention of plastic pollution (Fürst and Feng, 2022).

The study categorizes China’s regulations into three types based on the supply chain: (1) regulations on plastic production, (2) regulations on plastic waste management, and (3) regulations on industry standards for plastic products (Xu, 2024). At the production stage, the Clean Production Promotion Law establishes core principles of pollution prevention and product design, aiming to reduce secondary microplastic pollution (Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, 2012). Complementing this is the Plastic Restriction Order, which regulates the selection and scope of materials used (State Council, 2007).

In the field of waste management, the Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law and the Solid Waste Pollution Prevention and Control Law authorize the classification of microplastics as hazardous substances and establish obligations related to pollution disclosure, recycling, and enforcement (Standing Committee of NPC, 2019; Standing Committee of NPC, 2020). The Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law and the Marine Environmental Protection Law strengthen these measures by regulating land-based emissions and marine dumping, as well as allowing microplastics to be dynamically included in the pollutant catalog (Standing Committee of NPC, 2018; 2024).

In addition to written laws, China also adopts industry standards to manage plastic-containing consumer goods (Zhou and Xu, 2024). Technical specifications for products such as detergents and cosmetics set environmental and safety requirements, increasingly incorporating mechanisms that adapt to scientific advancements. Although microplastics are not always explicitly mentioned, these standards provide a flexible legal foundation for future regulation (Xu, 2024).

As the previous analysis indicates, China has made significant progress in building a relatively comprehensive legal framework for MPPG and continues to advance efforts aimed at reducing regulatory fragmentation. However, despite rapid progress in legislative development, judicial responses remain notably lacking. Research on the official database of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) of China’s online rulings shows that, as of 2025, no case—whether criminal, civil, or PIL—specifically addresses marine plastic pollution (China Judgments Online, 2025).

This apparent judicial gap raises an important question: Despite Chinese laws clearly allowing prosecutors and administrative agencies to initiate marine EPIL, why has environmental judicialization not been realized in the field of marine plastic pollution (Zhai, 2024)? To explore the gap between legislative potential and judicial practice, it is necessary to examine the institutional roles and capabilities of the aforementioned actors in promoting the use of EPIL as a mechanism for addressing marine plastic pollution.

2.2 The importance of procuratorial agencies’ participation in MPPG through PIL

Both the public and government agencies’ rapid growth and increasing attention to marine EPIL reflect a broader political shift, namely, the transfer of significant environmental decision-making from the executive branch, as policymakers, to the judiciary, as neutral arbiters of environmental justice (Xie and Xu, 2021). However, there is a significant imbalance among the entities authorized to initiate marine EPIL, and this asymmetry is particularly evident in cases where procuratorial agencies are involved. While scholars have long called for an expanded role for NGOs in environmental governance to promote broader public participation, expecting environmental organizations to take a leading or large-scale proactive role remains unrealistic (Zhuang and Wolf, 2021; Chu, 2023). As for administrative agencies, they have shown limited initiative in asserting rights, primarily because the procedures initiated by administrative bodies remain the least formal among the three categories of authorized rights claimants (Xie and Xu, 2021). Meanwhile, administrative agencies tend to focus on enforcing regulations within the MPPG framework rather than initiating lawsuits. In this institutional structure, procuratorial agencies have become the most capable and policy-aligned actors to initiate marine EPIL related to MPPG issues.

Environmental protection organizations have not played a major role in EPIL. In 2023, the proportion of EPIL filed by procuratorial agencies reached 92%, and the proportion of EPIL filed by social organizations as the main body of prosecution was 4.8% (SPC, 2024). An increasing number of scholars have pointed out the main obstacles to more active participation by environmental protection organizations, particularly the strict limitations on their standing as plaintiffs and the lack of sufficient institutional or economic incentives to engage in litigation (Ma, 2019; Guo, 2019). These limitations are deeply rooted in China’s state-centered environmental judicial policy, reflecting long-standing legislative concerns about frivolous lawsuits (Gilley, 2012; Gao and Whittaker, 2019). In the specific field of marine issues, the position of environmental protection organizations is even more vulnerable, as China’s Marine Environmental Protection Law does not explicitly recognize the status of environmental protection organizations as initiators in marine cases (Liu, 2015). National security and military interests effectively exclude environmental protection organizations from qualifying as initiators. The repeated rejection by courts of attempts by environmental protection organizations to engage in marine environmental litigation further demonstrates this exclusion (Cui, 2024). Therefore, while environmental protection organizations can continue to contribute through cooperation with procuratorial agencies and administrative agencies, their direct involvement in maritime issues remains heavily restricted, not to mention their qualifications to independently initiate such actions (Xia and Wang, 2023).

China’s Marine Environmental Protection Law, along with joint provisions from the SPC and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP), authorizes relevant departments to file lawsuits against those responsible for marine pollution or ecological damage that causes significant national losses (China Supreme People’s Court and SPP, 2022; China SPC, 2024; SPC, 2024). It is noteworthy that, when initiating marine EPIL, these agencies take precedence over procuratorial agencies. However, the prospects for administrative agencies to initiate marine EPIL on MPPG issues remain unclear. This is because they tend to prefer using familiar administrative powers, such as ordering remedial actions or suspending operations, rather than litigation, which may lead to redundancy and inefficient use of resources (Zhao and Yang, 2022). Furthermore, the legal provisions regarding their role as plaintiffs in marine pollution cases are vague and overlap with other mechanisms, such as the ecological damage compensation system, raising concerns about resource waste (Xie and Xu, 2021).

By comparing procuratorial agencies with environmental protection organizations and administrative agencies, the advantages of procuratorial agencies initiating marine EPIL are highlighted. Unlike environmental protection organizations, procuratorial agencies have the legal standing and national recognition required to file such lawsuits. Furthermore, procuratorial agencies are more familiar with litigation procedures than administrative agencies, which often lack detailed procedural guidelines. Therefore, the judicialization of MPPG requires the active involvement of procuratorial agencies. With this fundamental issue established, further research on how procuratorial agencies can effectively initiate marine EPIL in the context of MPPG is crucial.

3 PIL as a pathway for procuratorial agencies to address MPPG: concepts and practice

3.1 The theoretical foundation and developmental context of procuratorial agencies initiating PIL

Before discussing the PIL initiated by China’s procuratorial agencies in the governance of marine plastic pollution, it is necessary to clarify the current theoretical framework of China’s public interest litigation system. Article 1234 of China’s Civil Code stipulates: “Where damage is caused to the ecological environment in violation of state regulations, and such damage can be restored, the organs or organizations prescribed by the state or by law have the right to request the infringer to undertake restoration responsibility within a reasonable period.” Article 58 of China’s Civil Procedure Law states: “For acts that damage social and public interests, such as environmental pollution or infringement of the legitimate rights and interests of numerous consumers, organs and relevant organizations prescribed by law may file lawsuits with the people’s courts.” Article 114 of the China’s Marine Environmental Protection Law provides: “For pollution of the marine environment or destruction of the marine ecosystem that causes significant damage to the state, the departments exercising marine environmental supervision and management authority under this law shall represent the state to demand compensation from the responsible party,” and further stipulates that “the people’s procuratorates may file lawsuits with the people’s courts.” These legal provisions form the jurisprudential basis for public interest litigation in China. Summarizing these legal bases, three types of entities—the organs prescribed by the state, the organs and relevant organizations prescribed by law, and the procuratorial agencies—are entitled to file lawsuits in cases of ecological and environmental damage or pollution. Overall, in lawsuits concerning environmental damage, procuratorial agencies generally have a lower litigation priority. Based on the principle that special laws take precedence over general laws, some scholars argue that “qualified social organizations” as defined in the Environmental Protection Law are unlikely to bring lawsuits concerning marine pollution under this law. Returning to the main topic of this article, it is clear that marine plastic pollution falls squarely within the regulatory scope of the Marine Environmental Protection Law, under which only marine environmental regulatory departments and the procuratorial agencies are entitled to bring lawsuits. In practice, the judicial role played by procuratorial agencies in the marine field is becoming increasingly important.

In China, procuratorial agencies serve as legal supervisory organs, with broad powers granted by the Constitution to supervise the uniformity and correct application of the law. Nevertheless, the exact boundaries and substantive scope of the supervisory powers of procuratorial agencies have been a subject of debate in both legal academia and judicial practice (Lin and Wu, 2022). One particularly controversial area is their power to initiate marine EPIL, a mechanism aimed at protecting ecological interests that go beyond individual rights.

Before 2017, the legal basis for procuratorial agencies to initiate marine EPIL was still weak. Although laws such as the Environmental Protection Law provided general provisions authorizing procuratorial agencies to file lawsuits against polluters and environmental violators, these provisions lacked clarity and specificity in terms of procedural standing. In this context of legal uncertainty, most procuratorial agencies adopted a cautious and conservative approach. Despite evident environmental damage, they often refrained from initiating marine EPIL (Wang and Xia, 2023).

With the promulgation of the amendments to the Administrative Litigation Law and the Civil Procedure Law in 2017, a significant shift occurred in this fragmented legal framework. These legislative revisions explicitly granted procuratorial agencies the qualification to initiate PIL aimed at protecting the ecological environment and natural resources, marking a crucial transformation. Notably, the amendments authorized procuratorial agencies not only to file lawsuits against private actors but also to take action against negligent administrative agencies that fail to fulfill their environmental regulatory responsibilities (Standing Committee of NPC, 2017).

Subsequent legislative developments have further consolidated the role of procuratorial agencies in marine EPIL and expanded their functional scope. In 2018, the SPC and the SPP jointly issued an interpretation, marking a significant advancement in regulation. For the first time, the legal framework formally included environmental civil PIL related to criminal cases (SPC and SPP, 2018; China the Supreme People's Court and SPP, 2018). This interpretive provision serves multiple functions: it expands the scope of the procuratorial agencies’ authority in environmental civil PIL; addresses the previously unregulated space for environmental administrative PIL; and establishes a procedural model for environmental criminal incidental civil litigation (You et al., 2023). As a result of these reforms, all three types of litigation—civil, administrative, and criminal—are now institutionally embedded within China’s socialist legal system (Zhang and Chen, 2010).

In 2022, the SPC and the SPP issued further provisions on handling PIL cases related to marine natural resources and ecological environment (SPC and SPP, 2022). These provisions clarified the functional role of procuratorial agencies in marine EPIL, facilitated effective coordination with marine environmental regulatory departments, and established the exclusive jurisdiction of maritime courts over such cases. As of March 2025, the NPC Standing Committee’s work report announced plans to formulate a law on procuratorial PIL. This forthcoming legislation is expected to provide a clearer legal foundation and specific roadmap for procuratorial agencies to initiate marine EPIL, thus creating institutional space for their future involvement in MPPG through the PIL mechanism (Standing Committee of NPC, 2025).

3.2 Typical cases of procuratorial agencies initiating marine EPIL and their significance

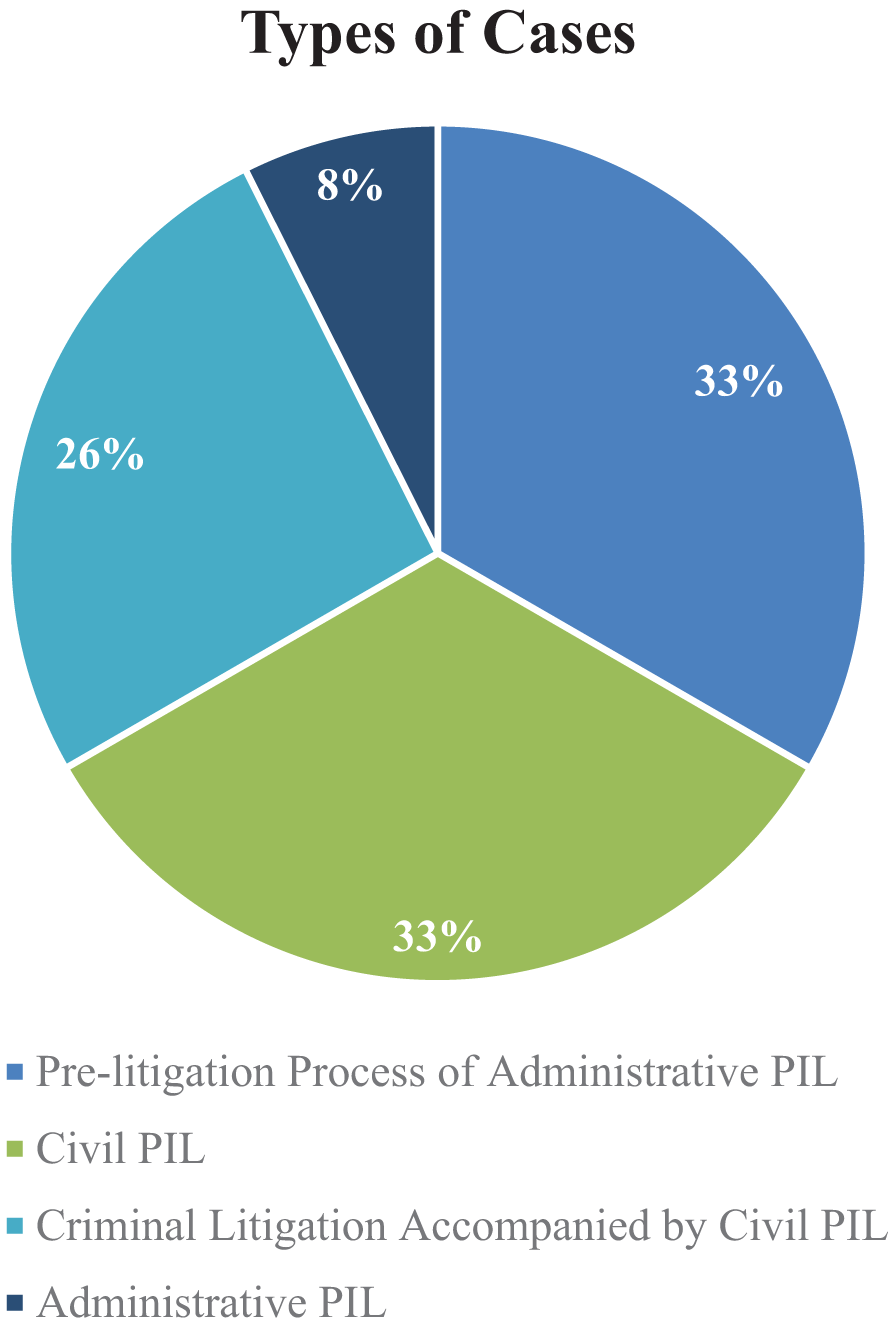

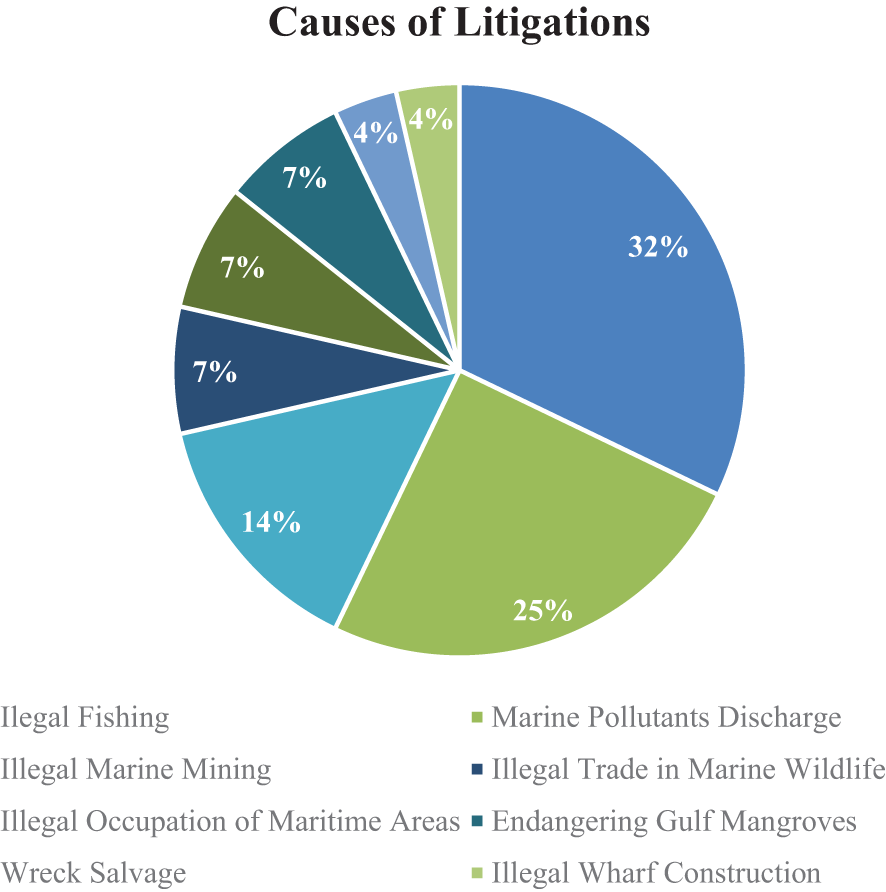

Although China’s judicial system does not formally recognize case law as a source of law, in practice, the guiding cases and typical cases issued by the SPC and the SPP serve as the most authoritative reference points for rulings (Gao, 2017). These cases not only reflect the priorities of China’s highest judicial organs but also signify the emerging theoretical trends in resolving various types of disputes. Accordingly, Figure 1 and Figure 2 jointly present an empirical analysis of the marine EPIL cases since the procuratorial agencies’ power to file EPIL was explicitly established in 2017. During this procedure, case selection was restricted to SPC- and SPP-published typical cases to guarantee jurisprudential authority and consistency. This approach encompasses all nationally recognized marine EPIL guidance cases issued post-2017, mitigating sampling bias while reflecting systemic judicial priorities. Specifically, these cases include: the EPIL cases from the “National Maritime Trial Typical Cases” published annually by the SPC since 2017; the typical cases from the “Guarding the Ocean the Ocean” PIL supervision activity issued by the SPP in 2020; and the typical cases of marine natural resources and ecological PIL jointly released by the SPC and the SPP in 2023, totaling 27 cases (SPC, 2021; SPC, 2022; SPP, 2020; SPC and SPP, 2023).

Figure 1

Proportion of different types of PIL.

Figure 2

Proportion of diverse causes of litigations.

Through the analysis of the types of cases mentioned above, it is clear that procuratorial agencies simultaneously initiate marine EPIL against public entities (including administrative PIL and pre-litigation procedures for administrative PIL, accounting for 41%) and private entities (civil PIL and incidental civil PIL in criminal cases, accounting for 59%). This reflects the role of procuratorial agencies in promoting compliance with marine environmental regulations and strengthening local government accountability mechanisms (Wang and Xia, 2023).

The empirical analysis of the litigation reasons further highlights the procuratorial agencies’ focus on illegal fishing and pollution discharge. As for pollution-related cases, neither the typical cases published by SCP and SPP nor the official Chinese judicial document database has published EPIL cases against marine plastic pollution so far (China Judgments Online, 2025). Nevertheless, the existing marine EPIL cases against marine pollution presented by the Table 1, including 6 typical cases presented by SCP and SPP, still hold reference value for future MPPG cases, as they reveal the inherent merits and challenges for procuratorial agencies to participate in MPPG through EPIL.

Table 1

| Case title | Year | Pollution source | Case type | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative PIL Case on the Pollution of Bohai Sea Ecological Environment by Rivers Flowing into the Sea in Gaizhou City, Liaoning Province | 2019 | Land-based sewage | Pre-litigation procedures for administrative PIL | The procuratorial agency issued a procuratorial proposal, urging the local environmental department to strengthen wastewater discharge supervision. |

| Administrative PIL Series Cases for the Protection of Nanji Island in Pingyang Prefecture, Zhejiang Province | 2019 | Land-based sewage and wastewater discharged at sea | Pre-litigation procedures for administrative PIL | The procuratorial agency issued a procuratorial proposal, urging the local environmental department to strengthen wastewater discharge supervision. |

| Administrative PIL Case of Illegal Discharge of Pollutants by Coastal Restaurants and Hotels in Zhanggang, Changle District, Fuzhou City, Fujian Province | 2019 | Land-based sewage | Pre-litigation procedures for administrative PIL | The procuratorial agency issued a procuratorial proposal, urging the local environmental department to strengthen wastewater discharge supervision. |

| Administrative PIL Cases Concerning Direct Discharge of Domestic Sewage from Residential Areas in Laoshan District, Qingdao City, Shandong Province | 2018 | Land-based sewage | Pre-litigation procedures for administrative PIL | The procuratorial agency issued a procuratorial proposal, urging the local environmental department to strengthen wastewater discharge supervision. |

| Administrative PIL Case on Illegal Dumping of Waste at Sea in Haikou City, Hainan Province | 2019 | Dumping of garbage at sea | Pre-litigation procedures for administrative PIL and civil PIL | The procuratorial agency issued a procuratorial proposal, urging the local administrative department. The procuratorial agency filed a civil PIL against the polluter, and the court ordered the defendant to pay 9.07 million yuan in remediation fees, appraisal costs, and other expenses. |

| Administrative PIL Case of the People’s Procuratorate of Ningbo City, Zhejiang Province v. The Natural Resources and Planning Bureau of Ningbo City | 2022 | Dumping of garbage at sea | Administrative PIL | After filing the PIL, the procuratorial agency concluded that the administrative authorities had fulfilled their duties, applied to withdraw the case, and the court approved. |

The existing marine EPIL cases against marine pollution.

By analyzing the above-mentioned EPILs related to marine pollution, it can be observed that procuratorial agencies possess unique advantages in handling such cases. First, procuratorial agencies are entitled to employ the relatively mild judicial measures of “procuratorial proposal” to urge local administrative departments to immediately fulfill their regulatory duties. In the appeal cases, the administrative department promptly communicated with the procuratorial agencies after receiving the proposal and fulfilled its duties. This demonstrates the unique advantage of procuratorial agencies in rapidly advancing marine pollution control without consuming a significant amount of time and judicial resources. Secondly, procuratorial agencies have a certain degree of flexibility when handling cases. compared to traditional high-cost litigation, procuratorial agencies can more flexibly and conveniently supervise government work through administrative pre-litigation procedures (Wang, 2022). For example, in a series of administrative PIL cases in Laoshan District, Qingdao City, Shandong Province, where residents were discharging sewage directly into the sea, the procuratorial organ issued a prosecutorial suggestion to the environmental and municipal departments before initiating the administrative PIL. This led to government agencies funding the construction of sewage interception facilities, eliminating wastewater discharge along nearly 3 kilometers of coastline (SPP, 2020). This demonstrates the positive role of the procuratorial agencies’ social and political resources in achieving governance goals through EPIL.

Common characteristics of guiding cases include identifiable damage liability, damage occurring within a single jurisdiction, and quantifiable or predictable damage. These factors simplify the prosecution process, making it easier to obtain approval from higher authorities to initiate EPIL.

However, when considering the complexity of marine plastic pollution, significant challenges arise (Maljean-Dubois and Mayer, 2020). The above case also reveals the shortcomings of the procuratorial agencies in handling MPPG cases. The aforementioned cases generally possess the characteristics of identifiable damage liability, damage occurring within a single jurisdiction, and quantifiable or predictable damage. These factors simplify the prosecution process, making it easier to obtain approval from higher authorities to initiate EPIL. By contrast, in the MPPG cases, the uncertainties surrounding liability, the geographical scope of the issue, and the dispersion of the damage make it particularly difficult to address marine plastic pollution within the existing marine EPIL framework. Specifically, at the level of the procuratorial agencies, obtaining case clues presents considerable difficulties. Unlike pollution cases involving ship pollution, oil spills, etc., where it is usually possible to clearly identify the responsible parties, causes of pollution incidents, scope of assessment, and accountability measures, the clues for marine plastic pollution are more complicated to obtain. The mobility of seawater makes it more difficult to trace the sources and movement of plastic waste, which exacerbates the difficulty the procuratorial agencies face when intervening in such cases. Moreover, there are significant uncertainties in evidence collection, case filing conditions, and other aspects, leading to hesitation in the initiation of marine EPIL in the field of marine plastic pollution. Given these challenges, it is understandable why marine EPIL has not yet been applied to cases involving marine plastic pollution. The unpredictability and complexity of MPPG pose additional legal and practical obstacles that the procuratorial agencies have yet to overcome.

Therefore, this analysis shows that while EPIL can play a key role in marine environmental protection, addressing the systemic flaws in its current application is crucial for effectively solving the MPPG issue. The following sections will explore the problems at hand and potential solutions.

4 Legal dilemmas faced by procuratorial agencies in initiating marine EPIL

In global marine governance practices, marine plastic pollution has become a major issue of concern for countries around the world, including China. A preliminary review of China’s legal norms and policy documents related to plastic regulation reveals that the Chinese government emphasizes source-based control and has established obligations for local governments, businesses, environmental organizations, and community residents through a top-down approach. However, the governance of marine plastic pollution is influenced by multiple factors. In addition to the negative externalities of economic development on the environment, the recognition and commitment of coastal local governments to marine protection vary. Given that local governments usually have their own specific interests, the central government’s ability to enforce national policies at the local level is limited. It is common for some regions to prioritize economic development at the cost of marine ecosystems. Due to internal conflicts of interest within the bureaucratic system, the implementation of environmental policies has long faced challenges. The bargaining process between central and local governments often leads to policy modifications. Therefore, relying solely on the autonomy of local governments for source-based regulation cannot produce effective results (Jiang, 2020). Through the “Environmental Protection Law,” “Civil Procedure Law,” “Marine Environmental Protection Law,” and other legal frameworks, China has gradually established a PIL system led by procuratorial agencies with Chinese characteristics. procuratorial agencies play an important role in marine governance. Although the PIL system has the potential to address marine plastic pollution, its application faces numerous challenges due to the complexity of plastic pollution management, which is the focus of this study.

4.1 The procuratorial organ raised the ambiguity of the measurement standard of “causing significant damage” in EPIL

Article 58 of the Civil Procedure Law stipulates that the condition for the public procuratorial agencies to initiate EPIL is based on “harm to the social public interest.” From various interpretations, “social public interest” can be understood as the demand with the potential to be jointly consumed by members of society, a value that is recognized, shared, and necessary for an unspecified majority. However, it is evident that this provision does not quantify the degree of harm to the social public interest (Liang, 2016). Article 114, Paragraph 3 of the Marine Environmental Protection Law states, “If the pollution of the marine environment or destruction of the marine ecosystem causes significant damage to the country, the departments exercising marine environmental supervision and management authority under this law shall represent the country to seek compensation from the responsible party.” This provision authorizes the marine environmental regulatory departments to initiate litigation for marine ecological damage compensation on behalf of the state. If these agencies fail to file a lawsuit, the procuratorial agencies may bring the case to the people’s court. This provision outlines two types of litigation, both of which are premised on the occurrence of “significant damage.” However, the critical issue is how to define “significant damage” in the context of marine plastic pollution.

Firstly, determining the criteria for marine plastic pollution is crucial. It must be clarified that for coastal communities, “making a living from the sea” has long been a way of life, and scattered or discarded fishing gear does not necessarily constitute marine pollution — marine plastic pollution does not inevitably lead to “significant damage.” Therefore, in the process of the procuratorial agencies initiating PIL related to marine plastic pollution, accurately defining the concept of “pollution” is especially important. The Marine Environmental Protection Law defines pollution in its supplementary provisions as: “The direct or indirect discharge of substances or energy into the marine environment, causing harmful effects such as damage to marine biological resources, harm to human health, interference with fisheries and other legitimate maritime activities, harm to seawater usability, or deterioration of environmental quality.” This provision adopts a results-based approach, using the occurrence of substantial damage as the criterion for determining pollution. However, determining pollution solely from the perspective of actual results has its limitations. The assessment of marine plastic pollution should also consider the specific nature of the pollution, such as its distribution range (e.g., whether plastic fragments have formed accumulations or elongated bands). However, current legislation in China related to plastic pollution does not provide clear standards in this regard, leaving ambiguity for judicial application. Additionally, the existence of “no significant damage” as the opposite condition to “significant damage” also raises questions. In cases where relevant marine regulatory departments fail to perform their duties in accordance with the law, how should the procuratorial agencies respond? This also requires further discussion.

Secondly, according to the “China Marine Ecological Environment Bulletin”, marine plastic pollution in China is mainly concentrated in coastal areas. In addition to development driven by economic growth and the opening of ports, many of China’s large-scale coastal fisheries and marine protected areas, which are intended to protect sensitive and vulnerable marine regions, are also located in coastal areas. Given that marine plastic pollution is influenced by seawater movement and ocean currents, it remains unclear whether the direct or indirect damage caused by marine plastic pollution to large-scale coastal fisheries and other types of marine spatial use can be classified as “significant damage.” It is worth noting that the condition for the procuratorial agencies to initiate PIL is that the pollution causes “significant national losses.” However, under the current marine plastic pollution legislation, it is still unclear whether the losses caused to private entities in such cases can be pursued by the procuratorial agencies on behalf of the public to seek damages.

4.2 The legal issues of multi-modal prosecutor initiated marine EPIL

Since the procuratorial agencies initiated PIL in 2014, three models have gradually emerged over nearly a decade of development: environmental civil PIL, environmental administrative PIL, and criminal incidental civil PIL, all aimed at protecting public interests. Although China has not filed a PIL case in the field of marine plastic pollution, these models still have potential applicability in marine protection, and their specific applications should be carefully determined according to actual needs. From an academic point of view, it is still necessary to conduct in-depth analysis and discussion on relevant legal issues, so as to provide guidance for possible judicial cases in the later period.

4.2.1 Disputes over the standing of environmental organizations as plaintiffs: focusing on coastal plastic pollution management

Due to the characteristics of ocean plastic pollution, even tens of thousands of tons of plastic in the high seas will eventually be carried by ocean currents to the coastal waters or even the coastal zone (i.e., the land-sea interface) of coastal countries. In academic discussions, there is no unified definition of the coastal zone. Both domestic and international discussions typically divide the coastal zone into geographic and administrative coastal zones based on the coastline. From an administrative management perspective, the definition of the coastal zone varies in practice due to the different coastlines and management needs of each country. However, China lacks specific legislation for the protection of the coastal zone environment, and the legal basis for coastal zone environmental protection comes from related laws. The “Marine Environmental Protection Law” mentions two terms: “coastal areas” and “natural coastal areas.” However, from a regulatory perspective, the focus is on protection and restoration, with this responsibility assigned to local coastal governments, aiming to address the issue from the perspective of administrative law. Nevertheless, relying solely on administrative agencies to enforce measures cannot fully achieve the goal of comprehensive protection of the coastal zone. On the judicial level, litigation for governance is a viable path. However, this requires clarifying who should have the standing to file PIL regarding coastal zone environmental protection, especially concerning pollution caused by the accumulation of ocean plastics and the damage to special ecological protection areas at the land-sea interface.

In the current judicial practice regarding coastal zone environmental protection, there are two types of litigation: one is ecological environmental damage compensation lawsuits, where administrative authorities demand that responsible parties bear the compensation for damages according to the law; the other is administrative PIL initiated by procuratorial agencies, requiring relevant departments to fulfill their duties, as well as civil PIL related to the marine environment initiated by procuratorial agencies according to legal procedures (Mei, 2024a). Domestic legislation in China grants the right to initiate litigation to marine environmental regulatory authorities and procuratorial agencies, which is inherently part of their responsibility in coastal zone protection, and this is undisputed. However, there are inconsistencies in judicial practice regarding whether environmental organizations can file PIL based on the characteristics of the coastal zone as the land-sea interface (Chu and Zhao, 2023). In practice, non-governmental organizations have initiated multiple EPIL, citing intertidal zone pollution as a reason. These cases mainly advocate for “beach EPIL” due to ecological damage to beaches, emphasizing the distinction between marine EPIL and ocean pollution. In the case of “China Green Development Association v. Liu Shui Town People’s Government of Pingtan County, Fujian Province and Longxiang Real Estate Development Co., Ltd. of Pingtan County,” the SPC supported the litigation claim that whether non-governmental organizations can initiate coastal zone EPIL depends on clearly defining the boundary between intertidal zones and sea areas (Wu, 2023). In 1985, China defined the scope of coastal zones and intertidal zone resources in a nationwide comprehensive survey, specifying that the coastal zone extends 10 kilometers inland and offshore to the 10-15 meters isobath. Based on this regulation, the inland portion is considered the beach intertidal zone, and environmental organizations can file a PIL based on this. In coastal zone environmental judicial practice, both non-governmental organizations and procuratorial agencies can initiate lawsuits, but this does not fully align with the collaborative governance principles of the land-sea coordination strategy.

4.2.2 Lack of unified standards for pre-litigation procedures in environmental administrative PIL

In the field of ocean plastic pollution management, civil PIL directly targets actions that pollute the environment and damage ecosystems, achieving a precise “targeting” effect in the lawsuit. In contrast, administrative PIL focuses on supervising the inaction or improper actions of administrative organs, effectively “leveraging” administrative power to protect the marine ecological environment (Xie and Yu, 2022). In addressing the issue of marine plastic pollution, both marine environmental regulatory authorities and procuratorial agencies can play a role in governance through administrative and judicial avenues. However, from the perspective of aligning with legislative provisions and maintaining the procuratorial agency’s restraint, administrative enforcement remains the primary means of addressing marine plastic pollution. Only when marine environmental regulatory authorities fail to act or act inappropriately should intervention through the initiation of marine environmental public interest litigation be considered. Procuratorial agencies can intervene in ocean plastic pollution governance through methods such as raise pre-litigation procuratorial proposals, and supporting lawsuits (Wang and Zhang, 2021). However, during the process of procuratorial agencies intervening in ocean plastic pollution governance, the following challenges may still arise:

(1) The standard for determining whether marine environmental regulatory departments have failed to fulfill or have neglected their duties remains unclear. According to the judicial interpretation issued by the SPC and the SPP on PIL initiated by procuratorial agencies, the target of administrative PIL must meet two requirements: a behavioral standard— “failure to perform duties according to the law,” and an outcome standard— “damage to public interests” (Zhang, 2022). In China, the governance of ocean plastic pollution primarily relies on marine environmental regulatory departments actively exercising administrative power. However, under China’s administrative system, marine-related management involves multiple departments, with overlapping and complex functions, often leading to shared governance by multiple agencies and overlapping responsibilities. Whether administrative organs have fully performed their statutory duties according to the law is a key factor in handling administrative PIL cases, determining the initiation of pre-litigation procedures, and the selection of subjects for procuratorial proposals. In the field of marine protection, the “Marine Environmental Protection Law” is the main legal basis. Procuratorial agencies can only exercise environmental judicial power and fulfill their supervisory duties to initiate relevant lawsuits when the administrative organs responsible for regulation unlawfully exercise their powers or fail to act. However, the key issue lies in how to define unlawful performance of duties or inaction by administrative organs. In judicial practice, there is currently a lack of unified standards for recognition.

From a behavioral perspective, if a department fails to perform its duties according to the law, or in some cases actively promotes the deterioration of pollution, its actions can be presumed to be intentional and constitute serious administrative violations. If the department continues to take no action and allows pollution to worsen, this still constitutes administrative inaction. In practice, the former situation is more harmful and results in broader negative impacts. The latter often occurs within China’s multi-agency administrative enforcement system, where the overlap of enforcement powers and jurisdictional conflicts between different administrative organs lead to mutual shirking of responsibilities and inaction, resulting in continuous harm to national interests. For example, in a guiding case published by the SPP— the case of Ningbo People’s Procuratorate v. Ningbo Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning in March 2020, the Yinzhou District People’s Procuratorate discovered that the involved parties had allegedly illegally occupied sea areas without approval. The marine regulatory authority failed to detect and stop this activity in time, leading to harm to national and public interests. As a result, the procuratorial organ urged the Department of Natural Resources and Planning to fulfill its regulatory duties, hold the responsible parties accountable, demand the return of the occupied sea area, restore the original state, and confiscate the illegal gains. However, the Department of Natural Resources and Planning responded that the act of dumping waste into the ocean constituted marine environmental pollution and should be handled by the department responsible for marine environmental supervision, thus refusing to fulfill its sea area regulatory duties. In fact, within China’s administrative system, both the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and the Ministry of Natural Resources are at the same administrative level, with overlapping functions in certain areas, and both are responsible for protecting the marine ecological environment. From the above case, it is clear that the actions of the Department of Natural Resources and Planning constituted administrative inaction. However, this determination was made based on the specific case, and subsequent legislation still needs to clarify and define the standards for unlawful exercise of power or administrative inaction by administrative organs.

From a results-oriented perspective, “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law for Cases regarding Procuratorial Public Interest Litigation (2020 Amendment)” stipulates that “if administrative organs with supervisory responsibilities unlawfully exercise their powers or fail to act, resulting in harm to national or public interests, the procuratorial organ shall raise procuratorial proposals or file a lawsuit.” At the same time, Article 114, Paragraph 2 of the Marine Environmental Protection Law states, “If marine pollution or ecological damage causes significant harm to the country, the department responsible for marine environmental supervision and management shall represent the state to seek compensation from the responsible party.” A potential issue is that, according to the Marine Environmental Protection Law, if no significant damage has occurred, the marine environmental regulatory department has no legal basis to demand compensation for marine ecological damage. However, in the case of unclear standards for determining significant damage caused by ocean plastic pollution, how to define “significant damage” and “damage to national and public interests, but not significant damage” becomes crucial. Whether the inaction of the marine environmental regulatory department should be considered is a question that needs further clarification. Otherwise, this could lead to situations where the procuratorial organ files administrative PIL based on the failure of regulatory departments to fulfill their duties, while administrative organs, under Article 114, Paragraph 2 of the Marine Environmental Protection Law, may refuse to take administrative measures or demand compensation from responsible parties on the grounds of “no significant damage.” This could severely undermine the effective governance of China’s marine environment.

(2) The effectiveness of pre-litigation procuratorial proposals cannot fully compel administrative organs to fulfill their duties. Firstly, it is difficult to accurately determine the obligated entities that should accept the pre-litigation procuratorial proposals. The effectiveness of procuratorial proposals typically relies on clearly identifying the administrative organ as the recipient to ensure that it can pressure the relevant departments to fulfill their duties. However, constrained by China’s current administrative system, despite the 2018 institutional reform plan by the State Council aimed at modernizing the national governance system, there still exists the issue of overlapping administrative powers in the field of marine governance. The sources of ocean plastic pollution are diverse, including land-based plastic from coastal areas, as well as plastics generated by passing ships and fishing activities. As a result, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the Ministry of Natural Resources, the Ministry of Transport, and the Ministry of Fisheries all bear the responsibility for preventing and controlling ocean plastic pollution, which presents potential obstacles to the effective issuance of procuratorial proposals. Ocean plastic pollution is merely a specific reflection of China’s broader efforts in marine ecological protection.

Secondly, procuratorial proposals lack sufficient “rigidity” in terms of legal effectiveness. On one hand, when ocean plastic pollution harms national marine interests and public interests, even after the procuratorial organ issues a proposal to the relevant marine environmental regulatory agency, whether that agency fulfills its legal duties is still entirely at its discretion. If the administrative organ chooses not to adopt the proposal, the procuratorial organ can only seek relief by initiating administrative PIL, lacking any other coercive means to force the administrative organ to take action. Some scholars argue that this practice does not align with the principle of administrative efficiency, undermines the goal of optimizing judicial resources, and could potentially increase the risk of marine environmental degradation. On the other hand, from the perspective of a “cost-benefit” analysis, legitimate and reasonable procuratorial proposals do play a positive role in urging administrative organs to fulfill their duties. However, if pre-litigation procuratorial proposals were abolished — removing the mechanism for prior evaluation of administrative actions — it could lead to excessive interference by the procuratorial organ in administrative law enforcement. This might violate the principle of prosecutorial restraint, which requires Procuratorial agencies to exercise caution and self-restraint when performing their supervisory functions (Liu, 2018).

4.3 An Analysis of the applicability and legal barriers for procuratorial agencies to initiate marine EPIL in foreign-related cases

4.3.1 Feasibility analysis of procuratorial agencies initiating marine EPIL in foreign-related marine plastic pollution cases

At the policy level, on December 30, 2024, the SPP issued the “Opinions on Strengthening Foreign-Related Procuratorial Work,” emphasizing that in the face of increasing external challenges, procuratorial agencies must take on the responsibility of safeguarding national security and promoting the efficient development of foreign-related procuratorial work.

At the level of legal norms, procuratorial agencies initiating EPIL should adhere to the general conditions for the application of legal systems, including temporal, spatial, and personal jurisdiction. Firstly, in terms of temporal jurisdiction, since China proposed the “exploration of establishing a system for procuratorial agencies to initiate PIL” in 2014, this system has gradually formed a relatively complete legal framework. Through the approach of “policy guidance + legislative improvement + judicial interpretation,” the scope of effectiveness for procuratorial agencies to initiate EPIL has been continuously expanded. Additionally, revisions to procedural laws such as the Civil Procedure Law and Administrative Procedure Law have provided guarantees for the implementation of this system.

Secondly, in terms of spatial jurisdiction, regarding MPPG, Articles 2 and 114 of the Marine Environmental Protection Law explicitly procuratorial agencies the power to initiate marine EPIL. According to this provision, procuratorial agencies initiating marine EPIL apply to waters under China’s jurisdiction. Additionally, if the pollution source is located outside China’s jurisdiction but causes environmental pollution or ecological damage to Chinese waters, procuratorial agencies can also file lawsuits based on this provision. This regulation reflects the Chinese government’s high regard for marine environmental protection and indicates that, in the interconnected state of the ocean, even if the pollution source is from outside Chinese waters, as long as it causes environmental harm to Chinese waters, procuratorial agencies have the right to initiate PIL under this legal provision.

Finally, regarding the effectiveness concerning the parties involved, the effectiveness of procuratorial agencies initiating EPIL also applies to parties who do not have Chinese nationality. Article 114 of the “Marine Environmental Protection Law” stipulates that if relevant administrative organs fail to perform their duties, procuratorial agencies can file a lawsuit. Although this provision does not explicitly identify the responsible party, based on the legislative purpose and goals of the “Marine Environmental Protection Law”, as well as the inherently transboundary nature of marine environments, any action that causes pollution to China’s waters and meets the standard for significant damage, regardless of whether the responsible party is Chinese or not, should be subject to this provision and held accountable. Additionally, Part 12 of the UNCLOS explicitly states that countries have the responsibility to protect the marine environment and, in certain cases, have the right to take legal action through judicial procedures. For example, Article 229 provides: “This Convention does not affect the right to initiate civil proceedings under applicable law to seek compensation for damage caused by marine environmental pollution.” This provision further emphasizes that when the marine environment is polluted, the affected party can seek compensation through appropriate legal procedures.

In conclusion, the applicability of procuratorial agencies initiating EPIL in foreign-related cases is fully supported by both domestic and international legal provisions, demonstrating strong legal adaptability and practical significance.

4.3.2 Obstacles to the applicability of procuratorial agencies initiating marine EPIL in foreign-related cases

Theoretically, procuratorial agencies have the conditions to initiate EPIL in foreign-related cases, but in judicial practice, it is difficult to achieve its practical effect.

Firstly, identifying the responsible parties for ocean plastic pollution is challenging. In fact, the sources of ocean plastic pollution are complex and varied, often involving multiple stages and different actors, such as land-based plastic waste from coastal areas, waste from passing ships, and plastic pollution caused by fishing activities. These pollution sources are widely distributed, and the spread of pollutants in the ocean often makes it extremely difficult to trace the origin of the pollution. Even with the use of certain investigative and technical methods, it is still hard to accurately track and identify the specific individuals or entities responsible. Therefore, in most cases, procuratorial agencies may face the dilemma of being unable to initiate litigation due to the difficulty of identifying the responsible parties. Procuratorial agencies face the same challenges when filing PIL in foreign-related marine environmental cases.

Secondly, procuratorial agencies may face strong resistance from foreign countries when initiating PIL in foreign-related cases, particularly in terms of legal application, national sovereignty, and international political maneuvers. From the perspective of legal application, most countries’ legal systems are based on the principle of territorial jurisdiction, meaning that the scope of legal application is generally limited to a country’s own jurisdiction. From the perspective of national sovereignty, each country bears independent responsibility for environmental governance, and legal disputes related to environmental pollution are usually resolved through diplomatic negotiations or bilateral or multilateral agreements, rather than through unilateral legal actions by one country. Particularly in the area of plastic pollution management, pollution sources often involve multiple countries, and there is significant controversy over responsibility allocation. If Chinese procuratorial agencies file PIL against foreign polluters based on domestic law, the relevant countries may view this as an infringement on their judicial jurisdiction and may refuse to cooperate with the litigation process, making enforcement more difficult. Additionally, at the level of international politics, MPPG is not only a legal issue but also an important area of geopolitical competition. For instance, in the draft text of the “Global Plastics Treaty,” there has been no consensus on key issues such as binding targets for reducing plastic production and funding support for developing countries.

Finally, in marine environmental public interest litigation initiated by procuratorial agencies, the governance of marine plastic pollution especially requires regional cooperation. In other areas of work carried out by Chinese procuratorial agencies, judicial authorities of various countries have already strengthened transnational cooperation in the lawful crackdown on the “three forces” (terrorism, separatism, and extremism), drug trafficking, cyber and transnational organized crime, and financial crimes through platforms such as the Meeting of Prosecutors General of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization member states. However, in the field of marine ecological protection, although China, Japan, and South Korea regularly hold ministerial-level meetings on ecological and environmental matters to strengthen marine ecological protection, procuratorial cooperation to address the increasingly severe issue of marine environmental pollution has not yet been established. In fact, cross-border marine plastic pollution requires even closer judicial cooperation between neighboring countries, with the establishment of regular cooperation mechanisms in areas such as evidence collection and exchange, pollution source investigation and tracing, and jurisdiction determination. At the international cooperation level, the Sino-French “Joint Declaration on Strengthening Cooperation on Biodiversity and Oceans: From Kunming-Montreal to Nice” can serve as a demonstration and guiding framework for regional cooperation in marine environmental governance. However, at the regional level, there is still a lack of such agreements. The absence of a regional judicial cooperation mechanism for marine plastic pollution could increase the challenges faced by procuratorial agencies in addressing marine plastic pollution.

In addition to the aforementioned obstacles, how to balance the allocation of authority within different administrative regions and between various levels of procuratorial agencies is also an important issue that may arise in the application of foreign-related cases. From the perspective of maritime law, China’s jurisdiction over its maritime areas includes territorial seas, contiguous zones, and exclusive economic zones. The territorial sea is closely connected to coastal provinces, and in cases of marine plastic pollution, the principle of proximity or relevant procuratorial agencies may intervene. However, for marine plastic pollution events that occur outside the territorial sea but still impact China’s maritime areas, determining which level or region of procuratorial agencies should intervene remains a question worthy of further discussion.

5 Optimizing the path for procuratorial agencies to initiate marine EPIL from the MPPG perspective

In the past decade, the specific practice of procuratorial agencies initiating PIL in China has developed from pilot programs to full implementation, accumulating rich practical experience. The inclusion of the “Procuratorial PIL Law” in the 2025 legislative agenda highlights the institutional advantages of this system. Under the MPPG framework, legislation should support the land-sea coordinated strategy, focus on marine EPIL, and clarify relevant legal issues through legislation, thereby promoting the standardization and in-depth application of this system.

5.1 Clarify the standard of “significant harm” brought by procuratorial agencies: including pollution types and harmful results

The “Marine Environmental Protection Law” and the “Solid Waste Pollution Prevention and Control Law” in China express a prohibition on dumping plastic waste into the ocean, but it remains difficult to specifically define “marine plastic pollution.” This presents a challenge for the prosecution authorities when initiating civil PIL based on the premise of “causing significant harm” due to marine plastic pollution. Therefore, this paper suggests the following standards to determine the “significant harm” caused by marine plastic pollution:

-

Spatial Scope Standard: The organization “Zero Plastic Ocean” classifies marine plastic into four different categories: Ocean Bound Plastic (OBP) Rivers refers to plastics discarded within 650 feet (about 200 meters) of a river or plastics within the river that have not yet been collected. OBP Coastline refers to plastics discarded within 650 feet (about 200 meters) of the coastline that have not been collected. Potential OBP refers to plastics discarded within 50 kilometers of the coastline that have not been collected. OBP Fisheries refers to improperly managed waste generated by fishing activities and fishing nets. Environmental organizations define marine plastic pollution based on spatial scope, and this method has significant reference value for China’s judicial practice in determining plastic pollution from a spatial perspective. However, given China’s long and winding coastline, this method may not fully cover all marine plastic pollution scenarios. Therefore, it should be supplemented with pollution quantity standards, such as whether the pollution reaches a threshold that impacts the marine ecosystem. For example, East China Normal University was the first to conduct a floating microplastic pollution survey in the Yangtze River estuary and the adjacent East China Sea. The results showed that the plastic abundance in the Yangtze River estuary (4137.3 ± 2461.5 pieces/m) was far higher than that in the adjacent East China Sea (0.167 ± 0.138 pieces/m). Research from Xiamen University showed that the microplastic abundance in the South China Sea was as high as 2569 pieces/m, with polyester resin (22.5%) and polycaprolactone (20.9%) accounting for nearly half of the total polymer content. In the coastal waters near Xiamen, the microplastic content in surface seawater was as high as 2017 pieces/m, and the microplastic content in sediments reached 333 pieces/kg. These quantity standards are based on experimental data from specific marine areas, and the specific pollution value standards need to be set through professional evaluation, customized for different regions within China’s jurisdictional waters. (Shao et al., 2019) In conclusion, China’s relevant legislation can refer to the above spatial pollution standards and pollutant quantity standards when determining marine plastic pollution. In coastal and near-shore areas, a certain width of marine plastic pollution control zones can be established. Once the pollution level exceeds this range, it can serve as a basis for the prosecution authorities to intervene.

-

Loss Quantification Standard: Quantifying “significant loss” and appropriately expanding the scope of direct loss. In October 2014, the former State Oceanic Administration issued the “National Claims Measures for Marine Ecological Damage and Loss.” This regulation provides detailed standards for determining “significant loss.” However, considering the potential impact of marine plastic pollution (including microplastic pollution), further consideration should be given to the economic factors of coastal areas. For example, the loss of coastal fishery resources and the impact of marine ecological degradation on tourism should be included in the scope of compensation for significant losses. (Wang and Zang, 2015) However, the specific quantification of these economic losses still requires the prosecuting authorities to comprehensively apply methods such as economic analysis and digital monitoring. Currently, the numerical standards for marine plastic pollution have not been fully established, and the prosecuting authorities still need to continuously summarize and practice in specific cases to form a more operational identification system. The two standards for determining “significant loss” mentioned above can be used to reverse-engineer the conditions for the establishment of pollution, and the prosecuting authorities can use these to initiate PIL. Conversely, if marine plastic pollution does not constitute a “significant loss,” although PIL may lack the necessary conditions for prosecution, this does not mean the prosecuting authorities cannot take action. In cases of “non-significant loss,” it should be the responsibility of the marine environmental regulatory departments to oversee the issue, rather than initiating marine EPIL. In other words, judicial environmental protection cannot replace environmental administrative management; it can only be supplementary. Due to the limitations of legal supervisory power, PIL by the prosecuting authorities can only be seen as the last resort for protecting public environmental interests (Wang X, 2021)

-

The above standards mainly focus on the quantification of “significant loss,” but as China increasingly emphasizes the protection of the marine ecological environment, preventive PIL, based on the principle of “protection first, prevention foremost,” should play a judicial role. In recent years, procuratorial agencies in China have continuously expanded the scope of preventive PIL, aiming to address public interest damages at their source. Although there is currently no explicit legal basis for procuratorial agencies to initiate preventive environmental civil PIL, they possess certain advantages over other legally designated agencies and relevant organizations in this area. This is particularly relevant given that such litigation involves assessing major environmental risks before actual harm has occurred, requiring a high degree of expertise and technical judgment. Abstract concepts such as environmental public interest, environmental risk, and environmental hazard must also be clearly defined. First, procuratorial agencies have more extensive judicial experience and greater access to legal and professional resources, enabling them to better address complex environmental issues and make more accurate assessments of environmental risks, thereby enhancing early regulation and prevention. Second, as representatives of state authority, procuratorial agencies are better positioned to coordinate with relevant departments during the investigation and evidence-gathering process. This facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of environmental risks and supports the formulation of reasonable claims and preventive measures. Finally, allowing procuratorial agencies to initiate preventive environmental civil PIL can help prevent environmental NGOs from abusing the right to PIL (Bao, 2024).

As evidenced in the case of the Tangshan People’s Procuratorate of Hebei Province v. a shipping company concerning the salvage of a sunken vessel. In this case, the prosecuting authorities, based on the current situation of the sunken ship, considered factors such as potential marine ecological damage and navigational safety risks, and filed a civil PIL against the responsible parties. Similarly, when prosecuting authorities intervene in marine plastic pollution cases, they should consider the “significant damage risk” as a critical factor and take preventive judicial measures to protect the marine environment in advance. At the same time, due to the unique nature of marine plastic pollution, prosecuting authorities should collaborate with marine environmental regulatory departments to strengthen preemptive supervision of coastal pollutant-emitting enterprises and fishing activities. Through review and record-keeping systems, they can curb the sources that may lead to marine plastic pollution, providing clues and legal grounds for future accountability.

5.2 Clarify the rules and standards for procuratorial agencies to file different types of PIL

5.2.1 Limitation of the subject of coastal plastic pollution litigation brought by procuratorial agencies in marine environmental civil public interest litigation

The 2023 China Marine Ecological Environment Bulletin shows that the average number of beach litter along China’s coastal beaches is 46,311 pieces per square kilometer, with an average density of 387 kilograms per square kilometer, and plastic waste accounting for 79.1%. This data vividly illustrates the current situation of beach litter in China and indicates that relying solely on marine environmental regulatory agencies to fulfill their responsibilities is insufficient for comprehensive governance. When administrative agencies fail to fulfill their duties, procuratorial authorities can play a complementary role. Coastal areas are the junction between land and sea, and the approach to resolving environmental judicial issues in these areas depends on different stakeholders’ understanding of specific marine areas. In judicial practice, many non-governmental organizations have filed EPIL, arguing that coastal areas fall within the scope of EPIL. However, courts have dismissed these cases, ruling that the plaintiffs had no standing to sue. For example, in the “Chongqing Liangjiang and Others v. Shijiqing Mountain and Others Environmental Pollution Liability Dispute Public Interest Lawsuit,” the Maoming City Court in Guangdong Province ruled that the plaintiffs had no right to sue and dismissed the case. However, the Guangdong Higher People’s Court, upon reviewing the case in the second instance, recognized the plaintiffs’ standing to sue. The significant differences in these rulings are largely due to China’s definition of the nature of coastal areas such as tidal flats. It is necessary to define the nature of these marine areas and clarify the allocation of litigation rights between procuratorial authorities and environmental organizations.

First, from the perspective of integrated land-sea management, the legal interest protected by marine EPIL should be the marine ecological environment as a whole system, rather than just the “marine area” environment. This is supported by the China Marine Ecological Environment Bulletin, which categorizes estuaries, bays, and tidal wetlands as typical marine ecosystems, clearly stating that marine environmental damage occurs not only in China’s jurisdictional waters but also in the “typical marine ecosystems” at the land-sea boundary. From this, it can be preliminarily concluded that coastal zones should be included in the overall scope of the marine ecological environment. According to Article 114 of the Marine Environmental Protection Law, both marine environmental regulatory agencies and procuratorial authorities can file PIL for this area. However, according to the basic legal principles of special laws and general laws, environmental organizations do not have the right to file PIL regarding marine environmental pollution in these waters (Han and Yang, 2024)

Secondly, when initiating a public interest lawsuit against marine plastic pollution in coastal areas, the marine environmental regulatory agencies is the first prosecution subject, and the procuratorial organ is in a secondary position, and non-governmental organizations can participate in the lawsuit. Given the litigation capacity of environmental organizations and the complexity of marine-related lawsuits, it is currently not suitable for NGOs to directly file marine EPIL. The reasons are as follows. First, state authorities (including marine environmental regulatory agencies and procuratorial agencies) have the inherent advantage of representing the state, and they adhere to the principle of prioritizing national and environmental interests in marine environmental governance. When maritime disputes arise with other countries, state authorities acting on behalf of the state help strengthen the legitimacy and recognition of such actions in the eyes of other countries. Second, considerations of maritime security play a role. Coastal plastic pollution is mainly concentrated within China’s territorial waters, and this area often involves matters of maritime military security. However, as an important force representing social public interests, environmental organizations will undoubtedly play an increasingly prominent role in China’s future environmental judicial governance. In the pluralistic governance structure of marine environmental judicial remedies, environmental organizations can participate in marine environmental affairs by exercising their rights to information, participation, and supervision in accordance with the law. For example, when discovering marine plastic pollution issues, environmental organizations can report to marine administrative agencies according to the law; if these organizations find that the administrative agencies have failed to take action, they can also report the matter to the procuratorial authorities. (Mei, 2024b) After the analysis of the above contents, the litigation subjects of coastal plastic pollution should be limited to marine environmental supervision institutions and procuratorial agencies.

5.2.2 Clarify the standard of omission of marine environmental supervision department and improve the effectiveness of procuratorial proposals