- 1International School of Law and Finance, East China University of Political Science and Law, Shanghai, China

- 2School of International Law, East China University of Political Science and Law, Shanghai, China

- 3School of Humanities, Jinan University, Zhuhai, China

- 4Department of International Relations, School of International Relations, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

The latest negotiating text from the International Seabed Authority (ISA) on the Environmental Compensation Fund (ECF) system shows significant progress compared to the provisions in the 2019 Draft Exploitation Regulations. First, the formulation of the ECF rules and procedures has been further elaborated. Second, the scope of application of the ECF has been more precisely delineated. Third, the mechanisms for funding the ECF have been improved. Fourth, the “polluter-pays principle” has been introduced for the first time. Fifth, a periodic review mechanism has also been incorporated for the first time. Nevertheless, the 2025 Draft continues to exhibit certain deficiencies. First, the financial foundations of the ECF remain unreliable. Several new or modified sources of funding, such as voluntary contributions from member States, targeted contributions from sponsoring States, and donations from international or non-governmental organizations, are inherently uncertain. Second, the text fails to establish clear and operational criteria for determining eligibility to submit claims to the ECF. Third, the scope of compensation available under the ECF remains inadequately defined. Fourth, transparency for stakeholders with respect to the operation of the ECF is insufficient. This study proposes the following recommendations to deal with the abovementioned deficiencies. First, the principles, mechanisms, and specific measures for the ECF fundraising and management should be optimized. Second, with respect to eligible claimants, a multi-tiered and sequential framework is recommended. Third, the scope of the ECF’s compensatory mandate should be refined, and detailed standards developed to ensure that the ECF is used exclusively to address liability gaps where environmental harm cannot otherwise be remedied. Fourth, stakeholder transparency must be enhanced.

1 Introduction

The International Seabed Area (hereinafter “the Area”) constitutes a vital part of the ocean and is designated as the “common heritage of mankind”(hereinafter “CHM”) (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 136). Rich in mineral resources, particularly critical metals such as nickel, cobalt, manganese, and copper, which are essential for clean energy technologies, the Area has become increasingly significant in international discourse (Zeng, 2024). The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter “UNCLOS”) addresses the Area comprehensively: in Part XI, through provisions on the Area itself; in Part XII, concerning the “Protection and Preservation of the Marine Environment”; and in Annex III and Annex IV, which govern prospecting, exploration and exploitation conditions and the Statute of the Enterprise, respectively. Additionally, the United Nations General Assembly adopted an Implementing Agreement in 1994 (Zeng, 2024). Collectively, these instruments establish the legal framework governing the Area. The International Seabed Authority (hereinafter “ISA”) is mandated to regulate seabed mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction (hereinafter “ABNJ”), including by developing regulations for the exploration and exploitation of mineral resources within the Area (Koschinsky et al., 2018).

In recent years, technological advancements and escalating global demand for metals and rare earth elements have intensified interest in mining activities in the Area (Wedding et al., 2015). The regulation of such activities has emerged as a central concern for the international community, with environmental protection in the Area arguably constituting the most pressing issue. Since 2011, the Legal and Technical Commission (hereinafter “LTC”) of the ISA has been drafting regulations pertaining to mineral exploitation (Zeng, 2024). The 2016 and 2017 Drafts did not contain provisions addressing environmental compensation in the Area. By contrast, Articles 52, 53, and 54 of the 2018 Draft introduced the concept of an environmental liability trust fund, which laid the groundwork for what is now referred to as the Environmental Compensation Fund (hereinafter “ECF”). The 2019 Draft Exploitation Regulations (hereinafter “2019 Draft”) formally established the ECF system. Negotiations among States have continued on the basis of this draft, seeking to refine and operationalize the ECF system.

The ECF plays a crucial role in several respects. First, its improvement enables more rational and effective allocation of environmental protection resources in the Area. By centralizing financial resources, the ECF facilitates the efficient deployment of limited environmental protection assets. Second, the ECF contributes to the institutional development of the Area. As the Area is part of the CHM and remains largely unexplored, its governance framework is still under development. Enhancing the ECF system strengthens the legal and institutional architecture applicable to the Area. Third, the ECF can serve as a model for international environmental governance. If effectively implemented, it may provide a valuable reference point for other legal regimes, such as those governing the polar regions or outer space, thereby reinforcing global environmental governance mechanisms.

In terms of existing literature, Xu and Xue have examined the necessity and international legal foundations for establishing the ECF (Xu and Xue, 2021). Zhou and Xiang have argued for a more limited purpose for the ECF, clearer identification of funding sources, and improved disbursement procedures (Zhou and Xiang, 2023). However, due to their publication dates, these analyses did not address the most recent developments of the ECF provisions. Notably, the negotiating text presented during the ISA’s 30th Session in 2025 (hereinafter “2025 Draft”) introduced significant amendments to the ECF provisions.

This paper seeks to address the following key questions: (1) What substantive improvements does the new ECF text contain compared to that set out in the 2019 Draft? (2) What deficiencies persist in the new ECF system? On the basis of these questions, this paper will offer recommendations to enhance the ECF framework.

The central argument of this paper is that, despite the substantial revisions reflected in the new ECF text, several critical shortcomings remain. These include instability in funding sources, ambiguity regarding eligible claimants, overly restrictive compensation scope, and insufficient transparency for stakeholders. To address these concerns, this paper will propose a series of recommendations.

Methodologically, this paper adopts a doctrinal approach. It compares the 2025 Draft with the 2019 Draft to elucidate recent progress in the development of the ECF system. By examining proposals submitted by negotiating delegations, it analyzes the legal development of key provisions and identifies potential challenges. On this basis, the paper proposes constructive and legally grounded recommendations.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Part I presents legal foundations and comparative analysis of the ECF. Part II analyzes the deficiencies of the new text. Part III offers proposals for improving the ECF system.

2 Legal foundations and comparative analysis of the ECF

2.1 Compensation within the context of international environmental law and deep seabed mining

Compensation is a form of state responsibility. The Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (hereinafter “ASR”) is the most important international document related to the responsibility of states. ASR stipulates that “full reparation for the injury caused by the internationally wrongful act shall take the form of restitution, compensation and satisfaction, either singly or in combination” in Article 34. According to Article 36 of the ASR, compensation serves as an appropriate form of reparation in situations where the harm cannot be remedied through restitution. It shall extend to all financially quantifiable harm, including lost profits. Under international environmental law, in cases where full restoration is not feasible, which is frequently the situation, the parties involved must achieve consensus on financial compensation (Kiss and Shelton, 2007). Therefore, compensation is a legally mandated payment or restorative action required to address measurable harm to the environment (Onyeabor, 2024). It necessitates an itemized assessment of the specific elements of environmental harm that qualify for redress (Craik et al., 2023). Establishing such responsibility generally requires demonstrating a breach of an international obligation that led to harm, although proof of intent to cause the harm is not usually required (Kiss and Shelton, 2007). Many multilateral environmental agreements and declarations recognize that when environmental harm occurs, the responsible state is obligated to restore the environment to its original condition (Kiss and Shelton, 2007). In addition, those undertaking remediation efforts are entitled to fair compensation.

According to Regulation 55 of the 2025 Draft, compensation in the context of deep seabed mining (hereinafter “DSM”) means financial payment for any harm or degradation caused to the marine environment. It appears that the definition for compensation in the context of DSM is basically similar to the definition under international environmental law. The subjects of such compensation include the Contractors, ISA and sponsoring States. According to Article 22 of the Annex III of UNCLOS, Contractors shall compensate for damage resulting from wrongful conduct during their operations, with due consideration given to any contributory actions or omissions by the ISA. Likewise, the ISA shall pay compensation based on its own wrongful acts in the exercise of its powers and duties, including breaches of Article 168(2) of UNCLOS. In all instances, liability is limited to the actual damage incurred. According to Article 139 of UNCLOS, the sponsoring States shall ensure that Contractors’ activities conducted in the Area comply fully with the provisions of Part XI of UNCLOS. Additionally, this Article specifically mandates liability for failure of obligation in the Area that, subject to existing international law and Annex III Article 22 of UNCLOS, any damage resulting from a State’s or international organization’s failure to fulfill its obligations under Part XI of UNCLOS gives rise to liability (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 139). However, it also provides exceptions that a State is not liable for compensating any damage caused by a Contractor it sponsors under Article 153(2)(b), provided it has taken all necessary and appropriate steps, as outlined in Article 153(4) and Annex III, Article 4 (4), to ensure the Contractor’s compliance (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 139). Furthermore, Article 235 of UNCLOS establishes a general obligation for States to ensure compensation for damage to the marine environment including the Area. It calls on States to cooperate in implementing existing international legal frameworks and in development of international legal norms concerning responsibility and liability (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 235). This includes the provision of prompt and adequate compensation and the formulation of standards and mechanisms, such as compulsory insurance schemes or compensation funds (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 235).

2.2 Comparison with other environmental compensation funds

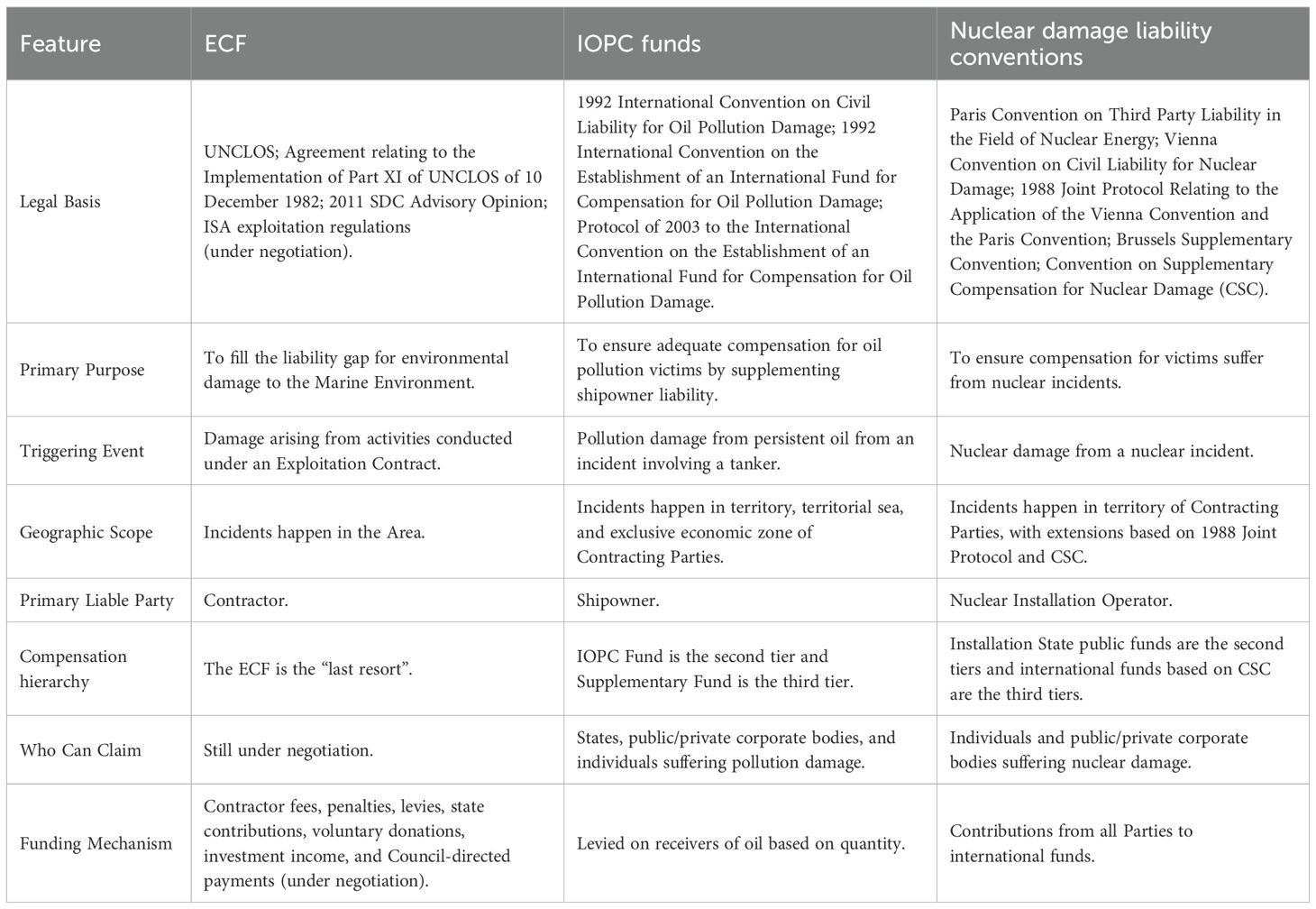

Before the proposal of the ECF, there were other important compensation funds and liability regimes. One is the International Oil Pollution Compensation (IOPC) Funds, the other is based on nuclear liability conventions (see Table 1).

All three regimes are founded on the basis of “polluter-pays principle”. This principle is one of the fundamental principles of international environmental law (Nanda and Pring, 2012). Moreover, all three regimes emphasize that those responsible for environmental pollution should bear the costs of compensation. However, each regime applies this principle differently. The IOPC Funds adopt a burden-sharing model between shipowners and cargo interests. In contrast, the nuclear liability regime places the financial burden primarily on the Operator, subject to compensation limits and supplemented by States’ support. The ECF put emphasis on liability to both Contractors and their sponsoring States. In addition, all three Funds share the core objective of ensuring adequate compensation for damage resulting from environmental pollution. This reflects the international community’s commitment to protecting the global environment.

Nonetheless, the ECF also exhibits distinctive features compared to the other two regimes. It applies specifically to incidents that occur in the Area, which sets it apart from the territorial scope of the IOPC Funds and nuclear liability systems. This reflects the growing global concern regarding the environmental impacts of activities conducted in ABNJ. However, it is important to note that due to the transboundary nature of marine pollution, the ECF is likely to compensate for environmental damage that happened within the national jurisdiction if this damage stems from the incidents that occur in the Area.

2.3 Analysis of the development of the ECF clauses

The 2016 and 2017 Drafts did not address environmental compensation in the Area. The 2018 Draft introduced provisions for an environmental liability trust fund in Regulations 52 to 54, outlining its establishment, purpose, and sources of funding. The 2019 Draft renamed the fund as the ECF and relocated its provisions to Regulations 54 to 56. Notably, the language in item (e) of the fund’s purpose was revised from “the restoration and rehabilitation of the Area when technically and economically feasible” in the 2018 Draft to “the restoration and rehabilitation of the Area when technically and economically feasible and supported by Best Available Scientific Evidence”. Other provisions remained unchanged. Therefore, a comparison between the 2025 Draft and the 2019 Draft is sufficient for analysis (see Table 2).

2.3.1 Further refinement of ECF rules and procedures

Regulation 54 of the 2019 Draft acknowledged the need for ECF rules and procedures but did not specify their timing of establishment or content. The 2025 Draft addresses this by requiring that the rules and procedures be established “before the [approval of a first Plan of Work for an Exploitation Contract] under these Regulations” (ISA, 2025a). This imposes a timeline on the ISA and links the development of the ECF framework to the commencement of commercial exploitation activities. This temporal condition encourages States with commercial mining interests to expedite the formulation of rules, thereby advancing the broader regulatory process.

Moreover, the 2025 Draft strengthens the legal obligation of the ISA by changing the verb from “will” to “shall” in reference to the Council’s duty to formulate these rules (ISA, 2025a). This underscores the mandatory nature of the obligation and the ISA’s heightened commitment to environmental protection.

The 2025 Draft also delineates the specific content of the ECF rules and procedures. These include requirements governing contributions to the ECF, fund replenishment, minimum size, fund management, eligibility and procedures for claims, types of compensable damage, standards of proof, temporal scope, disbursement mechanisms, and stakeholder participation (ISA, 2025a). This represents a substantial advance in providing clarity and institutional guidance.

2.3.2 Further rationalization of the ECF’s scope of application

The scope of the ECF in the 2019 Draft was criticized as overly broad (Zhou and Xiang, 2023). The 2025 Draft addresses this by articulating a clearer and more narrowly defined scope in Regulation 55, presenting two versions and retaining the one with the most support during the ISA’s 28th session.

First, the 2025 Draft explicitly characterizes the ECF as the “last resort” (ISA, 2025a). Previously, this concept was implied or derived from jurisprudence, notably the Advisory Opinion of the Seabed Disputes Chamber of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (hereinafter “the SDC”) (Xu and Xue, 2021). The new language “last resort” provides a statutory anchor for this principle.

Second, the 2025 Draft adds a conditional requirement that covered environmental harm must be “not foreseen in the Plan of Work or that arise from a breach of any condition of approval” (ISA, 2025a). The 2024 proposal text included “unlawful” as a condition (ISA, 2024a). However, this condition may be problematic. As defining “unlawful” could raise interpretive difficulties, whether it refers to international or domestic law remains unclear. The fundamental purpose of establishing the ECF is to address liability gaps that arise where recourse to the sponsoring State’s responsibility under customary international law proves insufficient (Feichtner, 2020). Environmental harm occurring in the Area is often latent (Niner et al., 2018) and cumulative (Levin et al., 2016). Accordingly, damage caused by Contractors may include not only immediate, visible harm but also potential future harm that is currently indiscernible, necessitating a preventive approach (Levin et al., 2020). At the time the damage occurs, the extent of its actual impact may be difficult to assess due to spatial, temporal, and technological limitations (Durden et al., 2017). Certain environmental consequences may only manifest a number of years later, and establishing a causal link between such delayed harm and prior activities may prove exceedingly difficult. Consequently, it becomes challenging to determine whether a particular instance of environmental damage qualifies as “unlawful”. If environmental harm that does not meet the “unlawful” threshold is excluded from the scope of ECF compensation, liability gaps for which no institutional remedy exists will arise. As such, the deletion of the term “unlawful” from the 2025 Draft may be considered a justified revision.

2.3.3 Optimization of provisions on funding sources

The 2019 Draft provided a basic framework for ECF funding but was inadequate in addressing financial sufficiency (Zhou and Xiang, 2023). The 2025 Draft significantly broadens potential sources of funding. While removing certain provisions, such as percentages of fees or legal recoveries, it adds new mechanisms, including annual levies from Contractors and the Enterprise, contributions from sponsoring States, and donations from NGOs, international organizations, and member States (ISA, 2025a).

The 2025 Draft also clarifies the allocation of funding obligations among stakeholders: Contractors and the Enterprise are responsible for levies and penalties, while sponsoring States are designated as contributors. Collection mechanisms mirror those in the 2019 Draft, distinguishing between mandatory payments (collected by the ISA) and voluntary contributions (received directly by the ECF).

2.3.4 Introduction of the “polluter-pays principle”

The “polluter-pays principle” is one of the fundamental legal principles governing the exploitation of mineral resources in the Area (Sharma, 2019a). However, the provisions of the ECF addressing losses resulting from environmental pollution in the Area have historically failed to incorporate this principle. The 2025 Draft has now introduced this principle into both the scope of application of the ECF and its funding provisions. Regulation 55 of the 2025 Draft establishes that Contractors are liable for the costs of mitigating, remedying, and compensating damage resulting from their activities. This aligns with Article 139(2) of UNCLOS, which addresses liability for failures to fulfill obligations under Part XI. In addition, referring to Article 139(2) of UNCLOS in the text contributes to a clearer distinction between environmental damage in the Area that should be addressed by Contractors’ liability and that which requires compensation through the ECF. This distinction ensures that the ECF does not substitute the primary liability. Moreover, this introduction safeguards the existing liability regime under UNCLOS and prevents misuse of the ECF to address harm caused by identifiable polluters. This is likely to reinforce the ECF’s character as the “last resort”.

2.3.5 Introduction of a periodic review system

The 2025 Draft introduces a periodic review mechanism for assessing the scope of the ECF. The review will consider, inter alia, whether restoration has become technically and economically feasible and whether it can be carried out using Best Environmental Practices and Best Available Techniques (ISA, 2025a). However, the 2025 Draft does not yet elaborate on the frequency of reviews or procedures for initiating them.

3 Shortcomings of the 2025 Draft on ECF clauses

3.1 Unreliable fund capital sources

Due to limitations in scientific and technological development, as well as the inherent challenges in defining and valuing environmental damage caused by DSM, determining appropriate compensation for environmental harm remains difficult (Lodge et al., 2017). The scale of such compensation could be considerable. Under these circumstances, the ECF must possess adequate resources to ensure compensation can be provided. However, the current funding mechanisms outlined in the 2025 Draft provisions are unreliable and may prove insufficient to meet this need.

The first funding source for the ECF is “(a) The prescribed percentage or amount of [contribution] paid into the Fund [by Contractors or the Enterprise] after approval of a Plan of Work and prior to the commencement [of activities] under an Exploitation Contract] [of Commercial Production]”. There is still no clarity regarding how the aforementioned proportion or amount should be calculated. While this percentage may be determined in the future by the Council based on the recommendations of the Finance Committee, it is currently undefined. This lack of clarity renders the expected scale, function, and operational model of the ECF highly uncertain. During Council discussions on the fees to be paid by Contractors, a proposal was made to impose a 1% levy on environmental damage and liability. However, some delegations considered this figure too low and criticized the inflexibility of a fixed percentage (Willaert, 2020b). Consequently, the proposed rate failed to achieve consensus.

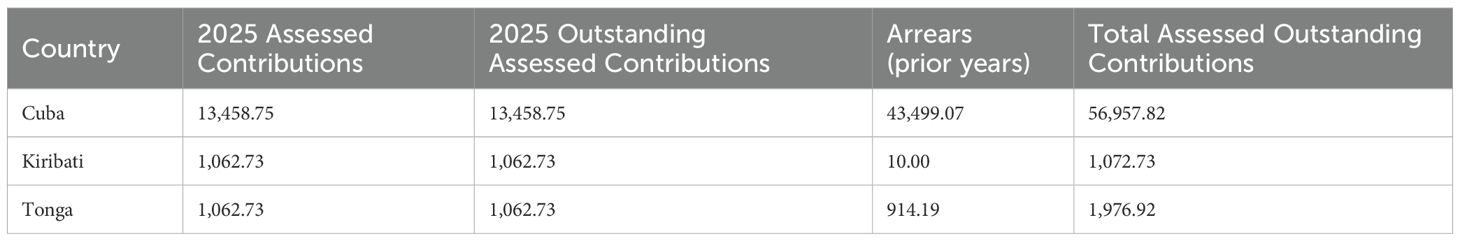

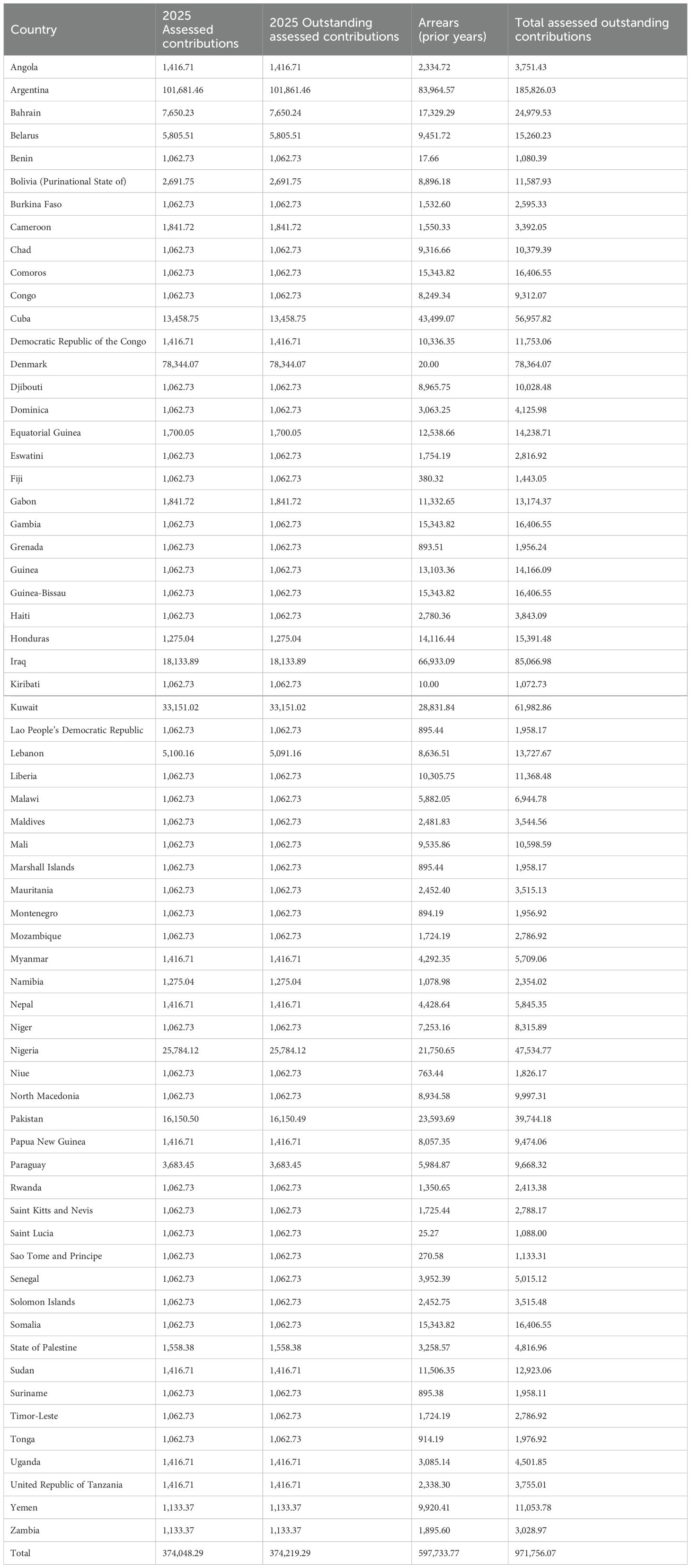

In the 2019 Draft, the equivalent clause reads that “(a) The prescribed percentage or amount of fees paid to the Authority”. This clause was removed in the 2025 Draft, meaning that fees paid to the ISA are no longer designated as a source of ECF funding. The rationale for this revision lies in the perceived stability of assessed contributions. Collecting funding annually and in a timely manner may provide a reliable funding stream. However, the collection of assessed contributions remains problematic. Data compiled on assessed contributions by ISA member States as of August 2025 reveal ongoing arrears (see Tables 3, 4).

Table 3. Countries with accumulated arrears and arrears status (ISA, 2025b).

As shown in the Tables 3 and 4, many ISA member States are in arrears, including three current sponsoring States. This significantly impacts the Authority’s financial stability. The ISA has stated that, since these are sovereign debts, the funds remain recoverable (ISA, 2022b). Nonetheless, the delay in payments reduces the time value of money, which may adversely affect the ECF’s functionality.

The second funding source is “(b) The prescribed percentage of any penalties paid by Contractors or the Enterprise to the Authority”. Originally, this clause did not include the phrase “Contractors or the Enterprise”. Germany proposed the inclusion of “Contractors” (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022a), and the final version also incorporated penalties imposed on the Enterprise. Annex III, Article 18(2) of UNCLOS authorizes the Authority to impose penalties commensurate with the severity of a violation. The ISA’s jurisdiction extends to all natural and legal persons conducting activities in the Area, irrespective of nationality (Ngum and Rene, 2021). Regulation 80 of the 2019 Draft stipulates penalties in accordance with Regulation 103(6). Nevertheless, Regulation 103(4) provides that the ISA may not impose monetary penalties until the Contractor has had a reasonable opportunity to exhaust available procedural remedies.

However, there is substantial doubt as to whether penalties can constitute a reliable funding source for the ECF. The penalties regime was a point of contention during negotiations. The German delegation, in relation to Regulation 103 of the 2019 Draft, emphasized the need for additional criteria to determine when penalties should be imposed in lieu of contract suspension or termination (ISA, 2024c). While such distinctions help promote legal certainty and fair treatment, they may also decrease the frequency with which penalties are imposed, thereby limiting this revenue stream. Spain noted that monetary penalties should be available except in cases of serious, persistent, or willful violations (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022e). Furthermore, the enforcement of penalties may be delayed, as Contractors must be afforded time to pursue judicial remedies (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022e). One version of the Regulation 64Qui(h) of the Draft proposes penalties for various forms of Contractor non-compliance. Although this provision could enhance fine-based revenues, it has faced resistance from mining companies (Open-ended Working Group, 2023). Stakeholders have requested clarification on the legal basis, thresholds, and procedural safeguards governing such penalties (Open-ended Working Group, 2023). Given these unresolved issues, the inclusion of this provision in the final text remains uncertain.

Even if adopted, this clause is unlikely to generate sufficient revenue. African States, for instance, have consistently argued that general penalties and penalties cannot provide adequate funding for the ECF (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022c). This concern is well-founded. First, the ISA’s enforcement activity is currently limited. According to the 2018 Secretary-General’s report, no Contractors had been fined as of that year (ISA, 2018). Second, penalties must comply with the principle of proportionality, limiting their amount (Harrison, 2022). Thus, penalties constitute an irregular and unreliable income stream, and their potential should not be overestimated.

The third funding source was originally “(c) The prescribed percentage of any amounts recovered by the Authority by negotiation or as a result of legal proceedings in respect of a violation of the terms of an exploitation contract”. Nevertheless, this provision was deleted. As a result, compensation recovered through legal processes will not serve as a funding source for the ECF. However, should such recoveries prove substantial in practice, their exclusion could hinder the ECF’s financial sustainability.

The currently listed clause is “(c) Any [other] monies paid into the Fund at the direction of the Council, based on recommendations of the Finance Committee”. Although the phrase “any amounts” appears flexible, the nature and magnitude of such payments remain undefined.

The fourth funding source is: “(d) Any income received by the Fund from the investment of monies belonging to the Fund”. At the 27th session, the African Group proposed replacing the earlier (a)-(e) items with “a.) the prescribed upfront Environmental Compensation Fund fee paid prior to the commencement of mining: and(b) Any income received by the Fund from the investment of monies belonging to the fund” (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022c). They argued that general fees and penalties were insufficient and proposed a substantial upfront fee to address environmental liabilities, especially in the early stages of mining (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022c). This approach would ensure that the ECF has immediate capacity to respond to early-stage environmental incidents. However, the 2025 Draft does not clearly designate who manages these investments or whether such investments entail financial risk. If such investments are exposed to financial risk, this funding source may also lack reliability.

The fifth funding source is “(e) An annual levy paid by Contractors or the Enterprise to the Fund [pursuant to a decision of the Council]”. In 2019, a 1% annual levy was proposed, with a $500 million cap. Another version proposed a fixed annual payment with a $100 million ceiling (ISA, 2019a). The non-governmental organization Pew Charitable Trusts supported a separate fund for early-stage environmental harm, noting that capping such contributions lacked clear justification and advocating for annual payments over the life of a contract (ISA, 2019b). This is consistent with the concept of a “percent-per-year levy”, emphasizing that such contributions should be continuous and recurring annually, rather than a one-time payment or subject to a ceiling. At the 27th Session of the ISA, the Mexican delegation emphasized the concept of “an annual levy paid by Contractors to the Fund”. The delegation stated that it was recommended that Contractors, in addition to the percentage determined by the financial mechanism, also pays an annual levy to the ECF (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022f). At the 29th session in 2024, entities including NORI, TOML, and BMJ advocated for deleting this paragraph (ISA, 2024b). The Pew Charitable Trusts proposed revising the provision to “An annual levy paid by Contractors or the Enterprise to the Fund pursuant to a decision of the Council” (ISA Council, 2024). It argued that such wording would be preferable as it would clarify how such an annual levy is to be established and by whom (ISA Council, 2024). This suggests that although the concept has been incorporated into the 2025 Draft, its concrete modalities remain unresolved and require further clarification. Notably, the 2019 Draft made no reference to an “annual levy”, nor did it provide any explanation of the term. As such, the implementation of this concept may necessitate the subsequent development of detailed rules or interpretive guidance.

The sixth funding source is “(f) Any [voluntary] contributions [from the Authorities member states]”. At the 30th Session of the Council in 2025, the Spanish delegation addressed the proposal regarding “Any voluntary contribution from the Authority’s member States”. It noted that the 2025 Draft already provides a fairly comprehensive list of potential funding sources (ISA Council, 2025). However, as a general observation and recommendation, it suggested that voluntary contributions from the Authority’s member States could also be considered as a viable funding option (ISA Council, 2025). However, as shown in the Table 3, as of 2025, 65 member States of the ISA had outstanding membership contributions, totaling USD 971,756.07. These States are unlikely to make voluntary contributions to the ECF. Moreover, to date, no member States in good standing have indicated a willingness to make voluntary contributions to the ECF. Accordingly, the extent to which this source of funding can effectively support the ECF remains uncertain.

The seventh funding source is “(g) [Any contributions] paid by Sponsoring States to the Fund”. During the 27th Session of the Council, the representative of Mexico has emphasized the need for additional sponsoring State contributions, drawing parallels to the IOPC Funds (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022f). However, this provision was met with opposition from the Republic of Nauru, which raised several concerns regarding paragraph (g). Nauru questioned whether a formal policy decision had already been made requiring sponsoring States to contribute to the ECF; what the expected amount of such contributions would be; when they would be due; and how small island developing States such as Nauru could be expected to contribute during the initial stages of exploitation, prior to the generation of commercial revenues. Nauru further asked whether the obligation to contribute would apply only to those sponsoring States whose sponsored entities hold exploitation contracts (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022h). It emphasized that these issues warrant further policy discussion, or alternatively, the relevant text should be removed (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022h). At the 28th Session of the Council, Nauru reiterated its position, suggesting that the reference to the “prescribed contributions paid by sponsoring States to the Fund” be revised to read “Any contributions paid by sponsoring States to the Fund” (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2023). It expressed clear opposition to the mandatory language of paragraph (g) as currently drafted, particularly insofar as it imposes a financial burden on developing States, and small island developing States in particular, to make contributions to the ECF (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2023).

Under the current model, sponsoring States are only required to assume sponsoring responsibility in the Area. According to Article 26 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, should this provision ultimately be incorporated into the exploitation regulations, it would impose an additional financial obligation on sponsoring States. This may increase the financial burden borne by such States and potentially hinder the achievement of consensus among ISA member States. As previously mentioned, several ISA member States are currently in arrears on their financial contributions, including three sponsoring States with outstanding membership fees. In light of this situation, the likelihood that this provision will ultimately be adopted remains uncertain. Even if it is formally adopted and enters into force for ISA member States, it is difficult to envision that those States that have not yet paid their membership dues will effectively fulfill this additional financial obligation.

The eighth and final funding source is “[(h) Donations or grants from international organisations, non-governmental organisations or other entities committed to environmental protection and sustainability.]” This clause was added following the 29th session of the Council. At present, it is unclear which entities may be willing to provide such funding, leaving the reliability of this source undetermined.

In summary, most of the funding sources currently identified in the 2025 Draft ECF provisions are unstable. Only a limited number can be considered dependable. Furthermore, key proportions and mechanisms remain undefined and subject to ongoing negotiation. Without reliable and predictable funding, the ECF may face significant obstacles to its long-term viability.

3.2 Unclear entities entitled to claim from the ECF

The 2025 Draft improves upon several aspects of the 2019 Draft. However, it still fails to clarify which entities are eligible to submit claims to the ECF. The ECF was originally established to address the liability gap identified in the advisory opinion of the SDC, one that could not be remedied through the liability of sponsoring States under customary international law (Svendsen, 2020). The 2025 Draft reaffirms the ECF’s role as the “last resort”. Without a clear definition of eligible claimants, ineligible parties may seek compensation when a liability gap arises, thereby undermining the ECF’s effectiveness and introducing disorder into the legal framework of environmental compensation.

In its advisory opinion, the SDC proposed a tentative list of potential claimants, including the ISA, entities engaged in DSM, other users of the sea, and coastal States (International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, 2011). However, the advisory opinion did not articulate specific eligibility criteria, rendering this list impractical for direct application. Further clarification is therefore necessary. Eligible claimants to the ECF should include entities that have incurred losses which cannot be fully compensated by the Contractor or the sponsoring State.

The inherently fluid nature of the marine environment complicates this issue, as pollution originating in the Area may traverse maritime boundaries (Martins et al., 2023). Two distinct scenarios must be considered. The first scenario is that DSM activities cause environmental damage in ABNJ. The second scenario is that such damage occurs within areas under national jurisdiction. In the former case, potential claimants may include contracting States of UNCLOS, ISA member States, the ISA itself, or, pursuant to the principle of the CHM, any State, individual, or institution. In the latter scenario, the State within whose jurisdiction the damage occurs is undoubtedly entitled to submit a claim. However, where that State fails to act, the question arises as to whether other entities, such as coastal States whose livelihoods depend on fisheries, may file claims by way of subrogation. This unresolved issue necessitates further legal elaboration to ensure that the ECF’s objectives are achieved effectively.

One underlying reason for this ambiguity is the novelty of the ECF system under the regime governing the Area. While references to such a fund can be traced back to UNCLOS and were later reflected in the ISA’s 2015 Framework for Exploitation Regulations, as well as the 2016 and 2017 Drafts, the ECF first appeared as a complete draft in the 2018 version. To date, only limited revisions have been made, and the 2025 Draft addresses only select contentious issues and remains incomplete.

A further complication is the absence of practical experience with the ECF system. A handful of technologically advanced States currently dominate the exploration and exploitation of mineral resources in the Area (Petrossian and Lettieri, 2024). Meanwhile, significant scientific uncertainties persist regarding the environmental consequences of such activities (Drazen et al., 2020). Although DSM operations have grown more frequent due to technological advancements, international disputes arising from these activities remain rare, particularly those involving environmental compensation. Consequently, no relevant case law exists to guide the implementation of the ECF.

3.3 Unreasonable scope of compensation

The scope of compensation under the ECF is a critical factor in determining whether it can fulfill its intended functions. As noted above, the 2025 Draft has removed the term “unlawful”, thereby reinforcing the ECF’s character as the “last resort”. The prior inclusion of “unlawful” as a prerequisite for compensation was problematic, as it excluded environmental damage not legally classified as “unlawful” from the ECF’s purview. The amendment mitigates the liability gap resulting from this exclusion. However, Article 55 of the 2025 Draft still contains internal inconsistencies and limitations.

First, paragraph 1 of Article 55 is contradictory. It states that the ECF compensates for damage caused by “activities conducted under an Exploitation Contract”, it also includes “contractor activities that were not authorized” as compensable incidents. This raises a question: can damage from unauthorized activities lacking an Exploitation Contract fall under subparagraph (a)? If so, it conflicts with the primary requirement of an exploitation contract; if not, it contradicts the provision that unauthorized activities are covered.

Second, the scope of compensation is unduly restricted to damage caused by “activities conducted under an Exploitation Contract” or “contractor activities”, thereby excluding harm caused by other human activities in the Area. This creates a potential accountability vacuum for environmental damage not linked to Contractors or Contracts.

Third, paragraphs 2 and 3 of Article 55 impose additional constraints by limiting the Contractors’ “polluter-pays” obligation and the ECF’s “last resort” function to situations where the Contractor is not liable under Article 139(2) of the UNCLOS. This conditionality dilutes the ECF’s intended “last resort” role, transforming it from a general environmental compensation mechanism into one that operates only under specific legal circumstances. Consequently, the ECF appears to be evolving into a Contractor’s fault compensation fund rather than a comprehensive environmental compensation mechanism.

These limitations primarily stem from conflicting interests among ISA member States (Sharma, 2022). For instance, regarding the ECF’s purpose, the African Group proposed that the ECF should address not only unavoidable environmental damage but also contribute to prevention efforts, while excluding post-mining remediation (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022b). They emphasized that “contractors’ own funds should be the first call for any required compensation/or mitigation”, thereby underscoring the ECF’s supplementary nature (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022b). China advocated that the ECF “should be remedial and supplementary, and be used to prevent, control, or repair environmental damage arising from activities in the Area” (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022g). Given this, it is recommended to remove provision that may weaken the main objective of the ECF (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022g). Conversely, Costa Rica proposed broadening the ECF’s scope to cover “damage to ‘the Area’, the Marine Environment or coastal States caused by activities in the Area, and the restoration and rehabilitation of the Area when technically and economically feasible” (Informal Working Group - Environment, 2022d). This divergence, particularly the expansive views of African and Costa Rican representatives, possibly influenced by their rich marine resource endowments, has contributed to an increasingly ambiguous and inconsistent articulation of the ECF’s purpose, conflicting with China’s more restrictive stance.

3.4 Insufficient transparency for stakeholders

Transparency is a cornerstone of international environmental governance, and it applies to DSM (Komaki and Fluharty, 2020). The ISA has acknowledged the importance of transparency in its regulatory instruments for mineral exploration and exploitation in the Area, and has incorporated it into stakeholder consultation questionnaires (Fritz, 2015). Nevertheless, significant deficiencies remain (Hvinden, 2024). The LTC has faced persistent criticism regarding its lack of transparency in particular (Feichtner, 2019).

The ECF system reflects these transparency shortcomings. Article 54 of the 2025 Draft provides for “the promotion of the participation of affected persons or other Stakeholders in decisions about disbursement of funds” (ISA, 2025a). Compared to the 2019 Draft, this inclusion of “Stakeholders” reflects a laudable attempt to enhance fairness. However, the provision fails to define the scope of “Stakeholders” entitled to participate. As a result, practical implementation of this clause is hindered by ambiguity.

Furthermore, the 2025 Draft does not outline procedural mechanisms to ensure stakeholder participation. While ISA member States may engage in fund disbursement decisions through internal channels, it remains unclear how participation rights will be secured for stakeholders beyond the ISA membership. Compounding this issue is the longstanding non-disclosure of environmental or safety data submitted by Contractors (Ardron, 2018). This lack of transparency impairs the ability of affected stakeholders to access relevant information in a timely manner. Although the 2019 Draft affirms that information concerning marine environmental protection cannot be classified as confidential, third-party stakeholders still lack avenues to submit objections or comments on the disclosed data (Willaert, 2020b).

Two primary factors explain these deficiencies. First, the ECF system remains at a legislative stage and has not been tested through practice. In the early phases of negotiations over the 2025 Draft, stakeholders lacked a comprehensive understanding of the system, and transparency concerns were overlooked. Second, because the negotiating parties are exclusively ISA member States, they have not prioritized the rights of non-member States or other external stakeholders. As ISA members are already able to engage through internal mechanisms, there has been little incentive to extend participatory guarantees to a broader range of actors.

4 Recommendations for the 2025 Draft on ECF clauses

4.1 Optimizing the principles, mechanisms, and specific measures for ECF fundraising and management

At the heart of the debate over funding sources lies the question of who should ultimately bear responsibility for environmental damage caused by DSM in the Area. Some oppose DSM in the Area (Singh et al., 2025) due to the uncertain environmental impacts, which may significantly exceed current scientific estimations (Miller et al., 2021). Such activities could result in irreversible harm to the marine environment (Jaeckel et al., 2017). Nonetheless, negotiations over the Exploitation Regulations are ongoing, indicating a prevailing inclination among negotiating Parties to pursue DSM in the Area. This must be understood in the context of UNCLOS, which prescribes binding obligations concerning marine environmental protection. Any entity conducting activities in the Area must therefore adhere to environmental protection duties. The ECF embodies a balanced approach, seeking to reconcile the dual imperatives of environmental protection and DSM in the Area.

It is recommended that the operational mechanisms and implementation framework of the ECF be refined along the following lines. First, the “polluter-pays principle” should be explicitly incorporated into the regulatory text. Under this principle, those responsible for pollution must bear the associated costs. The establishment of the ECF should in no way be interpreted as absolving or mitigating the polluter’s responsibility for environmental harm. Second, the ECF’s function as the “last resort” must be underscored in the regulatory hierarchy. The ECF should only be utilized after all other avenues of redress have been exhausted, specifically, where the Contractor has failed to fulfill its compensation obligations, and the sponsoring State is not held liable under Article 139(2) of UNCLOS. Premature reliance on the ECF risks diluting the obligations of Contractors and sponsoring States, thereby undermining accountability mechanisms enshrined in international law. Third, provisions on the ECF funding sources must remain aligned with the existing environmental liability regime applicable to the Area. A sponsoring State has a primary duty to ensure that activities in the Area by entities under its jurisdiction or control are conducted in compliance with Part XI of UNCLOS and ISA rules and regulations. While the ultimate objective is to secure the Contractor’s compliance with applicable regulations, the sponsoring State’s duty is to deploy appropriate means and exercise best possible efforts to achieve this outcome (International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, 2011). This “due diligence” obligation is characterized as an obligation of conduct, rather than an obligation of result, and is therefore understood in international law as a duty of diligence (International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, 2011). Compared to Contractors that are directly engaged in mineral exploitation in the Area, sponsoring States bear relatively lighter obligations. However, in contrast to States that are not currently involved in exploration or exploitation activities in the Area, sponsoring States shoulder greater responsibilities. Accordingly, it is advisable to encourage sponsoring States to contribute financially to the ECF. Such contributions would incentivize the enhancement of national legislative and enforcement frameworks. For ISA member States that are not sponsoring States, contributions should remain voluntary. This approach reflects practical constraints that some sponsoring States have yet to meet their assessed ISA contributions, as well as the basis of “polluter-pays principle” that non-polluting States should not bear mandatory financial obligations.

The following recommendations are made with respect to specific funding sources. First, regarding Contractor contributions before production, the proportion or amount of fees should be clarified through precise rulemaking. Both the proportion and timing of payments must be specified to avoid excessive deferral to future elaboration. Second, in terms of the penalties, it is recommended that a significant, if not full, portion of environment-related penalties be allocated to the ECF. The ISA should enhance its enforcement capacity to ensure penalties are effectively imposed and collected. Further, where a mining activity both violates ISA rules and causes environmental damage necessitating compensation from the ECF, the allocation of penalties should be maximized to support the ECF. This approach both strengthens the ECF reserves and provides a deterrent effect against non-compliance. Third, concerning sources from Council’s allocations, clear criteria should be established to guide the Council in determining when it must prioritize the ECF funding allocations, or even treat such allocations as obligatory. Fourth, regarding the investment income, investment of the ECF assets must follow a conservative strategy, limited to low-risk instruments such as government bonds, with a requirement for annual public disclosure of investment portfolios and performance. A minimum reserve ratio should be maintained to ensure adequate liquidity for unexpected environmental compensation claims. Fifth, with respect to the annual levies, the annual fee structure could be implemented based on the scale or revenue of the project, with progressive contributions. Environmentally responsible Contractors could receive incentives such as reduced fees or exemptions. Sixth, pertaining to the contributions from ISA member States, member States with interests or plans for mineral exploitation in the Area should be encouraged, but not compelled, to contribute. Under the current liability regime and given the foundational nature of the “polluter-pays principle”, such contributions must remain voluntary. It should be pointed out that no entity should invoke this provision to demand compulsory contributions from ISA member States. Seventh, as regards other voluntary donations, transparent, efficient procedures should be established for the acceptance and management of voluntary donations. However, such donations must remain supplementary. Overreliance on them could undermine the polluter’s legal responsibility for environmental harm.

4.2 Clarifying eligible claimants

The 2025 Draft lacks a clear articulation of the entities eligible to submit claims under the ECF, which may impair the ECF’s ability to assess the admissibility of claims when environmental harm occurs in the Area. It is inadequate to merely advocate for the subordination of national interests to the common interest of the international community. Rather, the international community is expected to recognize the ocean as a shared global resource (Wilde et al., 2023). Firstly, three categories of potential claimants should be recognized. First, states with a direct and concrete interest in the consequences of environmental degradation in the Area should be recognized as primary claimants. Although the Area constitutes the CHM, the adverse effects of environmental harm are often disproportionately borne by specific states, while others experience only indirect or attenuated impacts. Pursuant to the principle of equity, states experiencing direct and material harm should be entitled to compensation. These states invariably incur costs in responding to and mitigating the environmental damage, whereas the impact on indirectly affected states is often contingent upon the efficacy of the directly affected States’ response efforts. For example, Coastal States are protected under UNCLOS, which safeguards their “rights and legitimate interests” (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 142). Thus, where coastal States are the primary victims of harm in the Area, their impaired rights and interests warrant redress. For another example, some developing States may be more vulnerable to environmental degradation caused by DSM. Mining operations in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) present substantial risks to the surrounding small island developing States (Alam et al., 2025). Moreover, DSM has the potential to undermine food security and reduce income from tuna fisheries for small island developing States and other developing coastal States (Amon et al., 2024). These scientific findings indicate that they may rely more on the ECF to obtain compensation to recover from the influence of environmental incidents. Additionally, Article 140 of UNCLOS prescribes that activities conducted in the Area should give special attention to the needs and interests of developing States. Thus, developing States, particularly coastal ones, should be prioritized as primary claimants to the ECF. Second, although the immediate victim may be a particular State or entity, environmental damage in the Area constitutes a public harm to the CHM. Addressing such harm through publicly administered mechanisms, including the ECF, is both appropriate and necessary. Excluding directly affected States or entities from ECF access risks cultivating a passive international stance (Cato and Evoy, 2025) one of indifference under the logic of “not in my backyard”, which undermines the common responsibility for protecting the marine environment (Wang and Pan, 2024). Third, entities experiencing solely civil or economic loss should not qualify as directly interested for purposes of ECF claims. A critical distinction must be maintained between public and private losses. For example, if environmental harm disrupts a national ecosystem requiring remediation, the affected State may be eligible for compensation under the ECF. Conversely, where the harm merely affects tourism or other private economic sectors, the claimant should not be qualified.

Secondly, States or other entities lacking a direct interest in the environmental consequences may nevertheless be deemed supplementary claimants. Given the inextricable connection between humanity and the ocean (Sharma, 2019b), and recognizing that the UNCLOS imposes obligations to protect and preserve the marine environment (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 192), non-directly affected entities should, under specific conditions, be permitted to submit claims to the ECF. First, in the absence of sovereignty over the Area, there may be situations where no State possesses a direct interest in the environmental damage. In such circumstances, and in light of the Area’s legal status as the CHM, the duty to protect marine environment becomes a shared one (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 150). Consequently, States or entities lacking a direct interest may legitimately serve as claimants. Second, holding the status of claimant does not automatically entitle an entity to receive compensation. Entities without a direct interest may act as stewards of the CHM, but they must assume a share of the responsibility for seeking remediation. ECF compensation should be reserved for those undertaking actual environmental rehabilitation. Third, supplementary claimants should include not only coastal States, but also landlocked States, consistent with the principle of public participation (Rayfuse et al., 2023). However, non-state actors should be limited to those demonstrating a substantive nexus to the objective of marine environmental protection, so as to prevent the dilution of the claims process and the overburdening of evaluative resources with non-specialist involvement.

Thirdly, the ISA, as the body entrusted with administering the Area, should serve as the claimant of the last resort. First, the ISA possesses legal authority under UNCLOS to act as a claimant on behalf of humankind in the stewardship of the Area (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 137). Where no other qualified party initiates a claim, the ISA should ensure the protection of the marine environment. Second, the ISA’s mandate encompasses environmental management (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 157), and its institutional knowledge and operational experience equip it to assess environmental harm and submit claims when warranted. As an institution designated by the States Parties of the UNCLOS to organize and oversee activities in the Area (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 157), it can promote a claims process that is legitimate, informed, transparent, inclusive, and equitable (Menini et al., 2022). Third, filing a claim is not merely a right, but also an obligation of eligible claimants. Given this, a comprehensive institutional framework should delineate these responsibilities. Designating the ISA as the claimant of last resort is essential to bridging institutional responsibility gaps when eligible claimants fail to act.

4.3 Enhancing the scope of compensation

To more accurately reflect the ECF’s purpose, the scope of compensation should be refined to better align with its intended objectives and to promote a more efficient allocation of resources.

First, the ECF should be confined to situations where it serves to fill gaps in liability for environmental harm occurring in the Area. Given the current limitations of deep-sea technologies, environmental damage in the Area is ongoing and persistent (Miller et al., 2018). Moreover, the technical means for remedying such damage remain under active development (Van Dover et al., 2017). The ECF is well positioned to address these gaps. For example, the full ecological impact of DSM is currently unquantifiable, and necessary remediation may include indirect measures such as scientific research or capacity-building, both of which require substantial investment (Amon et al., 2022). ECF’s support for such purposes is appropriate. Accordingly, one criterion for compensation eligibility should be the existence of a causal link between the environmental harm and DSM. ECF’s support may be warranted even when harm is causally identified a number of years after the relevant activity. The other should be the presence of a liability gap. Where a specific actor can be clearly identified as responsible for the harm, primary responsibility must lie with that actor. ECF’s resources should be made available only when the responsible party is absent, unidentified, or unable to provide adequate remediation.

Second, the scope of ECF compensation could be harmonized with the environmental impact assessment (EIA), monitoring frameworks (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 204) and inspection mechanisms applicable to the Area. UNCLOS imposes obligations to conduct EIAs (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 206) and ongoing monitoring (UNCLOS, 1982 Art 204), as reaffirmed in the 2025 Draft (ISA, 2025a). EIA is a typical precautionary measure which presents the precautionary principle in international environmental law (Ma et al., 2023). Its purpose is to fulfill obligations and principles of international environmental law, notably the duty to prevent environmental harm and the duty to cooperate (Wang and Pan, 2025). Monitoring programs are required at all stages, prior to, during, and following a specific activity, in order to assess the impact of the DSM on biological processes, including the recolonization of areas that have been disturbed (Bräger et al., 2020). The purpose of inspection mechanisms is assessing compliance with the ISA’s rules, regulations, and procedures (Ardito and Rovere, 2022). Part XI of the 2025 Draft specifically introduces this mechanism. All of these regulatory pillars are designed to prevent environmental incidents that may arise during DSM activities conducted in the Area. Nevertheless, they cannot entirely eliminate the possibility of environmental incidents. When such incidents do occur, the ECF can provide timely compensation for environmental damage falling within its scope, thereby contributing to the protection of the marine environment to the greatest extent possible. In this sense, the ECF functions as an ex-post complementary mechanism to these regulatory pillars. Moreover, the ECF should align its compensation procedures with these mechanisms, making full use of conclusive documents such as EIA, monitoring and inspection reports. These documents should serve as key references in determining whether specific harm falls within the compensable scope of the ECF, thereby enabling the ECF to operate in a more targeted and effective manner.

4.4 Enhancing transparency for stakeholders

Transparency in the operation of the ECF must be improved to ensure stakeholders’ confidence and accountability. At a minimum, legislation governing DSM should incorporate non-confidentiality rules for data and information related to environmental protection and conservation, accompanied by clear procedures for public access (Willaert, 2020a).

Firstly, the definition of “stakeholders” requires clarification. According to the 2019 Draft, stakeholders include individuals or entities with interests in, potentially affected by, or possessing relevant information or expertise regarding activities in the Area. However, this definition fails to specify with sufficient precision which actors may participate in ECF funding decisions. First, the definition does not explicitly include States as stakeholders. Given the ECF’s function as the “last resort” for environmental compensation within the ISA framework, all ISA member States inherently qualify as stakeholders in ECF governance. Second, non-State actors, such as individuals, legal persons, and joint ventures, should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, in accordance with their relevance to the matter.

Secondly, a comprehensive participatory framework should be developed to ensure stakeholder involvement in ECF funding decisions. First, the proposal mechanism must be strengthened. The ISA should engage in broad consultations at both the proposal development and approval stages. Stakeholders, including States, international organizations, indigenous peoples, local communities, and the scientific community, must be provided with opportunities to participate. Mechanisms should be implemented to ensure that stakeholders’ comments are formally considered, including explanations of relevant decisions, the criteria applied, and unresolved concerns. Second, robust information disclosure mechanisms should be established. The ISA and administrative bodies of the ECF must be obligated to disclose relevant information fully, promptly, and accurately to safeguard stakeholders’ right to information. This would foster participatory decision-making and bolster public trust. For instance, the DeepData Database is to serve as a repository for all information concerning deep seabed activities, especially data gathered by Contractors during exploration, along with other pertinent environmental and resource-related data pertaining to the Area (ISA, 2022a). Moreover, the ISA’s integration into the Ocean Data and Information System (ODIS), which compiles data from over 800 conductivity, temperature, and depth sampling stations across the deep seabed (Letra, 2025), further enhances the transparency of environmental monitoring. Therefore, DeepData can be employed to track and disclose information such as the location and nature of environmental damage during exploitation, ensuring that affected communities and the broader international community are appropriately informed. Third, a rigorous accountability mechanism must be established. Entities that fail to ensure meaningful stakeholder participation, such as by withholding information or disregarding stakeholder input, must be subject to appropriate sanctions.

5 Conclusion

This study has undertaken a comprehensive analysis of the ISA’s latest negotiating text concerning the ECF regime. Compared to the provisions in the 2019 Draft, the 2025 Draft represents several noteworthy advancements. First, the formulation of ECF rules and procedures has been further elaborated. Second, the scope of application of the ECF has been more precisely delineated. Third, the mechanisms for funding the ECF have been improved. Fourth, the “polluter-pays principle” has been introduced for the first time. Fifth, a periodic review mechanism has also been incorporated for the first time.

Nevertheless, the revised text continues to exhibit certain deficiencies. First, the financial foundations of the ECF remain unreliable. Several new or modified sources of funding, such as voluntary contributions from member States, targeted contributions from sponsoring States, and donations from international or non-governmental organizations, are inherently uncertain. Second, the text fails to establish clear and operational criteria for determining eligibility to submit claims to the ECF. Third, the scope of compensation available under the ECF remains inadequately defined. Fourth, transparency for stakeholders with respect to the operation of the ECF is insufficient.

This study proposes the following recommendations to deal with the abovementioned deficiencies. First, the principles, mechanisms, and specific measures for ECF fundraising and management should be optimized. The “polluter-pays principle” should be affirmed, the ECF’s role as the “last resort” underscored, and funding sources aligned with existing liability regimes under UNCLOS. A diversified, transparent funding strategy including prioritizing Contractors’ and sponsoring State contributions and ensuring voluntary donations remain supplemental is essential. Second, with respect to eligible claimants, a multi-tiered and sequential framework is recommended. States with a direct interest in the environmental harm caused in the Area should be recognized as primary claimants. States or other entities without a direct interest may serve as supplementary claimants. The ISA, as the entity charged with the administration of the Area should act as the claimant of last resort. Third, the scope of the ECF’s compensatory mandate should be refined, and detailed standards developed to ensure that the ECF is used exclusively to address liability gaps where environmental harm cannot otherwise be remedied. Fourth, stakeholder transparency must be enhanced. This includes establishing robust participatory mechanisms to guarantee the rights of stakeholders in decisions regarding the disbursement of the ECF, as well as the creation of reliable channels for the disclosure of relevant information.

The ECF is a novel mechanism for addressing the potential environmental risks of DSM in the Area, its development and refinement is a complex and evolving process. Its ultimate effectiveness will depend on whether the international community can achieve consensus on the core issues identified herein and adopt rules and procedures that are practical, sufficient, and equitable. This calls for all parties involved in the negotiation of the Exploitation Regulations to uphold the principle of international cooperation and to commit collectively to establishing the ECF as a functional and effective legal instrument. In doing so, the ECF may come to serve as a robust safeguard for the CHM, advancing a sustainable equilibrium between the development of resources in the Area and the imperative of environmental preservation.

Author contributions

YoW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YiW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research is funded by the China Oceanic Development Foundation and the Academy of Ocean of China Key Project in the Field of Ocean Development Studies (2025): Research on the Legal Framework for China’s Application of the Principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities for Participation in High Seas Environmental Governance (Grant number: CODF-AOC202501).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT-4o was used for proofreading and language editing. Google Gemini 2.5 Pro was used for identify and retrieve relevant textual sources.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alam L., Pradhoshini K. P., Flint R. A., and Sumaila U. R. (2025). Deep-sea mining and its risks for social-ecological systems: Insights from simulation-based analyses. PloS One 20, e0320888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0320888

Amon D. J., Dobush B.-J., Drazen J. C., McCauley D., Nathan N., and van der Grient J. M. A. (2024). Potential interactions between deep-sea mining and tuna fisheries (Manila, Philippines: 20th Regular Session of the WCPFC Scientific Committee). Available online at: https://meetings.wcpfc.int/node/23115 (Accessed May 13, 2025).

Amon D. J., Gollner S., Morato T., Smith C. R., Chen C., Christiansen S., et al. (2022). Assessment of scientific gaps related to the effective environmental management of deep-seabed mining. Mar. Policy 138, 105006. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105006

Ardito G. and Rovere M. (2022). Racing the clock: Recent developments and open environmental regulatory issues at the International Seabed Authority on the eve of deep-sea mining. Mar. Policy 140, 105074. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105074

Ardron J. A. (2018). Transparency in the operations of the International Seabed Authority: An initial assessment. Mar. Policy 95, 324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.06.027

Bräger S., Romero Rodriguez G. Q., and Mulsow S. (2020). The current status of environmental requirements for deep seabed mining issued by the International Seabed Authority. Mar. Policy 114, 103258. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.09.003

Cato A. and Evoy P. (2025). Exploring plausible future scenarios of deep seabed mining in international waters. Earth System Governance 24, 100249. doi: 10.1016/j.esg.2025.100249

Craik N., Mackenzie R., and Davenport T. (Eds.) (2023). “Definition and Valuation of Compensable Environmental Damage,” in Liability for Environmental Harm to the Global Commons (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge), 54–94. doi: 10.1017/9781108866477.005

Drazen J. C., Smith C. R., Gjerde K. M., Haddock S. H. D., Carter G. S., Choy C. A., et al. (2020). Midwater ecosystems must be considered when evaluating environmental risks of deep-sea mining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 17455–17460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2011914117

Durden J. M., Murphy K., Jaeckel A., Van Dover C. L., Christiansen S., Gjerde K., et al. (2017). A procedural framework for robust environmental management of deep-sea mining projects using a conceptual model. Mar. Policy 84, 193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.07.002

Feichtner I. (2019). Sharing the riches of the sea: the redistributive and fiscal dimension of deep seabed exploitation. Eur. J. Int. Law 30, 601–633. doi: 10.1093/ejil/chz022

Feichtner I. (2020). Contractor liability for environmental damage resulting from deep seabed mining activities in the area. Mar. Policy 114, 103502. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.04.006

Fritz J.-S. (2015). Deep sea anarchy: mining at the frontiers of international law. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 30, 445–476. doi: 10.1163/15718085-12341357

Harrison J. (2022). “Checks and Balances on the Regulatory Powers of the International Seabed Authority,” in The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Part XI Regime and the International Seabed Authority: A Twenty-Five Year Journey. Eds. Ascencio-Herrera A. and Nordquist M. H. (Leiden; Boston: Brill | Nijhoff), 151–173. doi: 10.1163/9789004507388_012

Hvinden I. S. (2024). To mine or not to mine the deep seabed?: The relative influence of competing NGO views in defining “serious harm” to the marine environment. Maritime Stud. 23, 11. doi: 10.1007/s40152-023-00345-x

Informal Working Group - Environment (2022a). TEMPLATE FOR SUBMISSION OF TEXTUAL PROPOSALS DURING THE 27TH SESSION: COUNCIL - PART I Federal Republic of Germany’s Proposed Amendments to the Draft Regulation 56. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/GERMANY_56.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

Informal Working Group - Environment (2022b). TEMPLATE FOR SUBMISSION OF TEXTUAL PROPOSALS DURING THE 27TH SESSION: COUNCIL - PART 3 African Group of 47 Member States ‘s Proposed Amendments to the Draft Regulation 55. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/AFRICAN_GROUP_DR55_IWG_ENV.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

Informal Working Group - Environment (2022c). TEMPLATE FOR SUBMISSION OF TEXTUAL PROPOSALS DURING THE 27TH SESSION: COUNCIL - PART 3 African Group of 47 Member States ‘s Proposed Amendments to the Draft Regulation 56. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/AFRICAN_GROUP_DR56_IWG_ENV.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

Informal Working Group - Environment (2022d). TEMPLATE FOR SUBMISSION OF TEXTUAL PROPOSALS DURING THE 27TH SESSION: COUNCIL - PART 3 Republic of Costa Rica’s Proposed Amendments to the Draft Regulation 55. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/COSTA_RICA_DR55_IWG_ENV.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

Informal Working Group - Environment (2022e). TEMPLATE FOR SUBMISSION OF TEXTUAL PROPOSALS DURING THE 27TH SESSION: COUNCIL - PART I SPAIN’s Proposed Amendments to the Draft Regulation 103. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/SPAIN_103.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

Informal Working Group - Environment (2022f). TEMPLATE FOR SUBMISSION OF TEXTUAL PROPOSALS DURING THE 27TH SESSION: COUNCIL - PART II Mexico’s Proposed Amendments to the Draft Regulation 56. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/MEXICO_56.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

Informal Working Group - Environment (2022g). TEMPLATE FOR SUBMISSION OF TEXTUAL PROPOSALS DURING THE 27TH SESSION: COUNCIL - PART III China’s Proposed Amendments to the Draft Regulation 55. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/China-DR55_IWG_ENV.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

Informal Working Group - Environment (2022h). TEMPLATE FOR SUBMISSION OF TEXTUAL PROPOSALS DURING THE 27TH SESSION: COUNCIL - PART III Republic of Nauru’s Proposed Amendments to the Draft Regulation 56(g). Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Nauru_DR56_IWG_Env.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

Informal Working Group - Environment (2023). TEMPLATE FOR SUBMISSION OF TEXTUAL PROPOSALS DURING THE 28TH SESSION: COUNCIL - PART III Republic of Nauru’s Proposed Amendments to the Draft Regulation 56(g). Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Nauru_DR56_IWG_Environment.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (2011). Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area, Advisory Opinion, 1 February 2011, ITLOS Reports. Available online at: https://www.itlos.org/fileadmin/itlos/documents/cases/case_no_17/17_adv_op_010211_en.pdf (Accessed February 22, 2023).

ISA (2018). Information relating to compliance by contractors with plans of work for exploration Report of the Secretary-General. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/isba24-c4-e.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

ISA (2019a). Report of the Chair on the outcome of the second meeting of the open-ended working group of the Council in respect of the development and negotiation of the financial terms of a contract under article 13, paragraph 1, of annex III to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and section 8 of the annex to the Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/isba_25_c_32-1912014e.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

ISA (2019b). Statement of the Pew Charitable Trusts on ISA Financial Models. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/16-pewchtrust.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

ISA (2022a). DeepData Database. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/deepdata-database-old/ (Accessed May 29, 2025).

ISA (2022b). Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 December 2021. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/ISA-financial-statement-2021.pdf (Accessed May 29, 2025).

ISA (2024a). 2024 Draft regulations on exploitation of Mineral resources in the Area Revised Consolidated Text. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/29112024-Revised-Consolidated-Text.pdf (Accessed May 29, 2025).

ISA (2024b). 2024 Draft regulations on exploitation of mineral resources in the Area Compilation of proposals. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ISBA_29_C_CRP.3-Compilation_of_Proposals.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

ISA (2024c). ISA 29th Session, Part II – Reading of the Draft Consolidated Text Oral Statement by the Federal Republic of Germany Delivered in July 2024 Regulation 103 - Compliance Notice. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Germany-Statement_DR103-July_2024.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).

ISA (2025a). 2025 Draft regulations on exploitation of Mineral resources in the Area Revised Consolidated Text ISBA/30/C/CRP.1. Available online at: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/10012025-Revised-Consolidated-Text-2-1.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2025).