- 1Guanghua Law School, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

- 2Zhejiang Contemporary Institute of Ocean Law and Governance, Hangzhou, China

- 3School of Law, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

Advisory Opinion in the ITLOS Case No. 31 represents the first climate change-related advisory proceeding brought before an international judicial body. It addresses key legal issues, including the advisory jurisdiction of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as the “ITLOS”) as a full court, the legal characterization of greenhouse gas emissions, and the relationship between the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as the “UNCLOS”) and the international climate change legal regime. This paper examines how the ITLOS established its advisory jurisdiction by relying on the doctrine of “necessity inference” and subsequently applied systemic interpretation as an interpretive method to bring greenhouse gas emissions within the scope of “marine pollution” under Article 1(1)(4) of UNCLOS. It further analyzes how, for the first time, the ITLOS systematically integrated UNCLOS with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and other environmental treaties to address legal gaps in the law of the sea regarding climate change and to promote greater coherence within the international legal framework. This study argues that the advisory opinion reflects a broader trend toward the judicialization of global climate governance by international adjudicative bodies and enhances the applicability of UNCLOS in the context of global environmental governance. However, it remains essential to maintain a balance between the expansion of jurisdictional powers of international adjudicative bodies and the legal obligations of States Parties.

1 Introduction

In the current development of advisory opinion cases related to climate change in international judicial bodies, on 31 October 2021, the Prime Ministers of Antigua and Barbuda and Tuvalu signed the Agreement Establishing the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law (hereinafter referred to as the “COSIS agreement”) deciding to establish the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law (hereinafter referred to as the “COSIS”) (COSIS, 2021). In August 2022, the Commission of Small Island States requested the ITLOS to issue an advisory opinion on climate change and the protection of the marine environment. Subsequently, in January 2023, Chile and Colombia requested the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to issue an advisory opinion to clarify the State obligations in responding to climate emergencies under the American Convention on Human Rights. In April, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution requesting the International Court of Justice (hereinafter referred to as the “ICJ”) to issue an advisory opinion on the obligations of states concerning the climate change. On 21 May 2024, ITLOS has delivered its advisory opinion in ITLOS Case No. 31 in response to the Commission of Small Island States request. In this advisory opinion, the Tribunal determined States’ obligations under United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as the “UNCLOS”) concerning the climate change, establishing that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions constitute marine pollution under the UNCLOS and affirming States’ due diligence obligations in this regard. It is worth mentioned that on 23 July 2025, pursuant to a United Nations General Assembly resolution, the ICJ rendered an advisory opinion concerning States’ obligations erga omnes partes regarding climate mitigation. The Court determined that seminal climate instruments– including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change(hereinafter referred to as the “UNFCCC”), Kyoto Protocol, and Paris Agreement– establish legally binding obligations for the parties (I.C.J, 2025).

2 Literature review and analytical framework

2.1 Literature review

Many scholars are actively examining ITLOS Case No. 31 from a range of perspectives. First, regarding the Tribunal’s jurisdiction over the case, Barnes (2022) observed that after following the October 2021 agreement between Antigua and Barbuda and Tuvalu establishing a committee empowered to request Advisory Opinion from ITLOS, potential procedural obstacle existed for securing the Tribunal’s jurisdiction over advisory proceedings. Although no insurmountable barriers were identified, Barnes emphasized that meticulous formulation of submitted questions would be crucial. Second, from the perspective of UNCLOS State Parties’ obligations in climate governance, further scholarship has highlighted that the COSIS initiative accelerated the prospect of an ITLOS advisory opinion on climate change, while examining its potential to advance obligations under the UNCLOS in climate governance and the corresponding legal complexities (Roland Holst, 2023). Comparative analysis of the due diligence obligations articulated in the ITLOS Case No. 31 and parallel jurisprudence reveals their critical role in facilitating system legal integration and delineating state obligations in climate governance (Liang, 2024). Third, from a legal interpretive standpoint, an examination of the ITLOS’s application of the systemic integration in treaty interpretation revealed both expansive and selective interpretive approaches, underscoring the need for enhanced methodological clarity and transparency in international adjudicatory reasoning (Thin, 2025). Overall, the ITLOS Case No. 31 determined that the anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions qualify as marine pollution under the UNCLOS and imposed due diligence obligations on states with respect to the protection of the marine environment. This jurisprudential development is expected to fundamentally reconfigure international climate governance frameworks (Deng et al., 2024).

2.2 Analytical framework

The study aims to delve into how the “doctrine of necessity inference” was applied to establish ITLOS jurisdiction in Case No. 31, and the use of systemic interpretation as an interpretive method in reconciling the UNCLOS with evolving climate obligations. Employing an integrated methodology of legal doctrinal analysis and systemic interpretation, the research will examine relevant UNCLOS provisions, treaty texts and ITLOS jurisprudence to reconstruct the tribunal’s reasoning. Specifically, it analyzes how systemic interpretation bridges legal gaps within ocean-climate governance by examining the opinion’s integration of the UNFCCC and other environmental treaties. Furthermore, a critical review of international judicial precedents evaluates the opinion’s contribution to the coherence of international law, particularly regarding the reconciliation of UNCLOS with contemporary climate obligations.

From the perspective of international maritime governance in the context of climate change, ITLOS Case No. 31 holds significant analytical value and merits close examination for the following three key reasons. First, it constitutes a landmark indicative precedent. Within the evolving legal framework that increasingly integrates climate change and marine governance, ITLOS—exercising its advisory jurisdiction—became the first international adjudicative body to issue an advisory opinion directly addressing climate change (Giorgetti, 2016).1 This development provides important legal guidance for parallel proceedings currently before the ICJ and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (Slaughter, 1994). Second, ITLOS Case No. 31 has generated a discernible spillover effect. The general legal principles articulated therein—particularly those concerning state responsibilities and obligations in responding to climate change—may influence the normative framework guiding international organizations’ climate-related activities, as well as intergovernmental negotiations under multilateral environmental agreements (Kittichaisaree, 2024, paras. 2 and 27). Although advisory opinions are not legally binding, they carry normative externalities as legal instruments and can exert de facto influence on how other states fulfill their national obligations, such as those related to climate change adaptation and mitigation policies (Roland Holst, 2023; Tanaka, 2023).2 Finally, regarding the judicialization trend, since the onset of negotiations for the UNFCCC, this case marks a departure from the traditional reliance solely on intergovernmental negotiation mechanisms to address environmental challenges arising from climate change. It reflects an emerging trend toward the judicialization of global efforts to combat climate change.

Today, the global fight against climate change faces mounting challenges. The outcomes of multilateral climate negotiations and national mitigation efforts have fallen short of expectations, prompting growing frustration among small island states over the inefficiency of global climate action. This dissatisfaction is contributing to the rising significance of advisory opinions as key instruments of climate adjudication. 3Accordingly, this study aims to interpret and understand ITLOS Case No. 31 by clearly identifying the key legal issues, examining whether advisory opinions, as a principal vehicle for international judicial engagement with climate change, can provide authoritative principles for the international adjudicative bodies and the wider international community in climate-related practice.

Structurally, the article proceeds as follows: Part II interrogates three core legal issues in ITLOS Case No. 31: (i) the establishment of the full court’s advisory jurisdiction; (ii) the classification of greenhouse gas emissions as marine pollution; and (iii) the system interpretation coordinating climate-related international treaties–demonstrating their legal foundations through textual analysis. Part III subsequently examines the normative implications arising from the resolution of these issues, assessing their broader significance through legal interpretation. Building on the opinion’s jurisprudential spillover effects, Part IV advances obligations to prevent and govern as normative imperatives for the UNCLOS States Parties. The conclusion affirms that ITLOS Case No. 31 expands the normative scope of the UNCLOS within climate change governance and contributes to systemic coherence in the international law for cross-cutting global challenges, while identifying persistent issues warranting further judicial scrutiny and scholarly engagement.

3 Three legal issues addressed in ITLOS Case No. 31

ITLOS Case No. 31, the first climate change case handled by an international judicial body, involves pivotal legal issues concerning: (1) the establishment of the ITLOS full-court’s advisory jurisdiction; (2) the classification of greenhouse gas emissions as marine pollution; and (3) the interpretive harmonization of climate-related international treaties (Filippi and de Mello, 2024; Klerk, 2025). These determinations are set to profoundly reshape the legal framework for global marine governance and the climate change mitigation. In this proceeding, the Commission of Small Island States submitted a formal request to the ITLOS, seeking the clarification of States Parties’ obligations to protect and preserve the marine environment under the UNCLOS. Referring to Article 192 of the UNCLOS, which stipulates that ‘States have the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment,’ and Article 194, which details the obligations to ‘prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment’, the Commission of Small Island States petitioned the Tribunal to clarify the specific obligations arising from these provisions with the context of climate change.

A total of 34 States Parties and 9 international organizations submitted written statements to the Tribunal, while 33 States Parties and 3 international organizations delivered oral statements. In response to the Commission’s request, ITLOS undertook an interpretation of the relevant provisions along three key dimensions, aiming to clarify the governance and preventive obligations of States Parties in addressing climate change under ITLOS Case No. 31.

3.1 Procedural confirmation: whether the full court possesses advisory jurisdiction

3.1.1 Textual interpretation

As the first advisory opinion case related to climate change, the jurisdiction of the full court remains one of the most contentious issues. Some non-member international organizations and States Parties, in their written submissions, argue that the application made by the Commission of Small Island States aligns with the provisions of the UNCLOS and Annex VI of the Statute of the ITLOS regarding advisory jurisdiction. For instance, the African Union contends that Article 21 of the ITLOS Statute (hereinafter referred to as the “Statute”) provides the substantive legal basis for ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction in ITLOS Case No. 31 (African Union, 2023, para. 68). This article states: “The jurisdiction of the Tribunal shall extend to all controversies and claims submitted to it in accordance with this Convention and to all questions expressly provided for in any other agreement that confers jurisdiction on the Court” (United Nations, 1982, Annex VI).

Furthermore, the African Union points to Article 138 of the Rules of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as the “Rules”), which stipulates that “The Tribunal may give an advisory opinion on a legal question if an international agreement related to the purposes of the Convention specifically provides for the submission to the Tribunal of a request for such an opinion.” In light of this, the African Union asserts that the request made by the Commission of Small Island States satisfies the criteria outlined in Article 21 of the Statute. Consequently, ITLOS has no compelling reason to refuse issuing an advisory opinion. Given that Article 21 of the Statute grants ITLOS jurisdiction over “disputes,” “claims” (ITLOS, 2015, para. 55) and “all matters specifically provided for in any other agreement conferring jurisdiction on the Tribunal,” (African Union, 2023, para. 69) it follows that the Tribunal’s jurisdiction should encompass all disputes, applications, and relevant matters (Feria-Tinta, 2023).

From the perspective of textual interpretation, there is no indication that the phrase “all matters” excludes requests for advisory opinions or precludes ITLOS from exercising its advisory jurisdiction. As Judge Lucky observed, “If a matter such as a request for an advisory opinion is excluded, the article will say so” (Cot, 2015, para. 4). Accordingly, the African Union contends that the COSIS qualifies as one of the “other agreements” capable of conferring advisory jurisdiction on ITLOS under Article 21 of the Statute (African Union, 2023, para. 73) Moreover, the claim at issue concerns the “specific matters” referenced in both Article 21 of the Statute and the COSIS. Therefore, the COSIS is understood to have validly conferred jurisdiction upon ITLOS (African Union, 2023, para. 73)

3.1.2 The legal logic of ITLOS’s jurisdiction

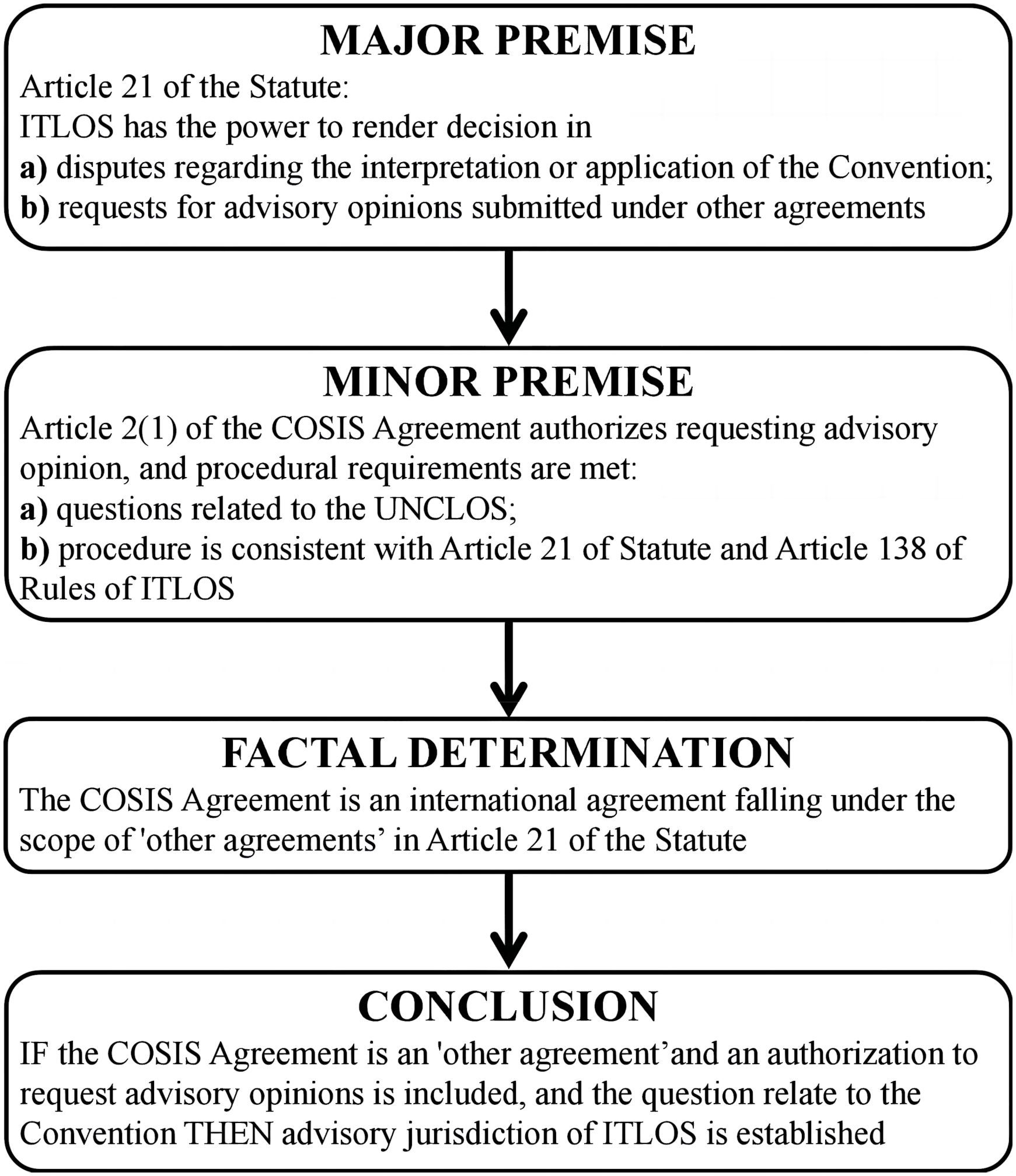

In terms of the logical demonstration of whether the full court has the advisory jurisdiction of over ITLOS Case No. 31, firstly according to Article 2 (2) of the COSIS: “…The Commission shall be authorized to request advisory from the ITLOS on any legal question within the scope of the 1982 United nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, consistent with Article 21 of the Statute and Article 138 of its Rules”, (COSIS, 2021) it means that the COSIS clearly authorizes the Commission of Small Island States to delegate the jurisdiction to provide advisory opinions to ITLOS. Secondly, as an agreement between states, the COSIS undoubtedly belongs to the “other agreements” in Article 21 of the Statute and is brought under the jurisdiction of ITLOS by the Statute. Finally, the interpretation of the legal relationship between the nature of the COSIS as an international agreement, the authorization clause in Article 2 (2) of the COSIS, and the confirmation that the jurisdiction under Article 21 of the Statute encompasses the COSIS, supports the conclusion that the full court has advisory jurisdiction over ITLOS Case No. 31 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Logical structure of ITLOS’s jurisdictional reasoning in ITLOS Case No. 31. Source: Author’s Illustration.

In fact, the logical argument in Case No.31 continues the ITLOS’s view in Case No. 21, “Request for an Advisory Opinion submitted by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission”. Case No. 21 is the first advisory case heard by the ITLOS as a full court. The full court examined Article 288 of the UNCLOS, Article 21 of the Statute, and Article 138 of the Rules, and clarified that the Statute and the UNCLOS have equal status and there was no subordinate relationship between them. It also proposed that the “all matters” in Article 21 of the Statute included the applications for advisory opinions, and Article 21 of the Statute and other international agreements constituted the substantive legal basis for the advisory jurisdiction of the full court (ITLOS, 2015, paras. 58-69)

Therefore, the African Union believes that the climate advisory request complies with Article 138 of the Rules and ITLOS should issue an advisory opinion on the request (African Union, 2023, para.71).4 According to paragraph 2 of Article 138 of the Rules: “A request for an advisory opinion shall be transmitted to the Tribunal by whatever body is authorized by or in accordance with the agreement to make the request to the Tribunal” (ITLOS, 1997), the request of the COSIS has been submitted to ITLOS by the Commission which is the authorized institution from the COSIS agreement (African Union, 2023, para. 80). Thus, once the ITLOS has the jurisdiction to issue an advisory opinion, it can decide whether to give an advisory opinion on its own. The tribunal finally held that it should not refuse a request for an advisory opinion unless there are “compelling reasons” in principle (ITLOS, 2015, para. 71; African Union, 2023, para. 81).

3.2 Conceptual definition: whether greenhouse gas emissions constitute marine environmental pollution

3.2.1 Opinions of international institutions, organizations and experts

In the substantive trial, there is a key that whether greenhouse gas emissions constitute “pollution of the marine environment” as defined in Article 1(1)(4) of the UNCLOS.5 The International Seabed Authority states that the marine ecosystem is as a whole. The harmful impact caused by climate change, such as ocean warming, acidification, and sea-level rise, have led to the damage of marine biodiversity, the change in the structure and function of the ecosystem, and the harm to the living resources and marine life with the threaten to the human survival and health. All of those are consistent with the adverse effect resulting from “pollution of the marine environment” as defined in Article 1(1)(4) of the UNCLOS. The concept of “pollution of the marine environment” is composed of three indicators: “by man, directly or indirectly”, “introduction of substances or energy into the marine environment”, and “results or is likely to result in … deleterious effects”. The harmful impact of anthropogenic carbon dioxide on the marine environment fall within the scope of “pollution of the marine environment”, triggering the corresponding obligations set for States Parties (International Seabed Authority, 2023, para. 19). Therefore, the harmful impact of the climate change on the ocean should be regarded as “pollution of the marine environment” in Article 1 (1)(4) of the UNCLOS. Then, the obligation referred in article 194 regarding “measures to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment”, the general obligation for the protection of the marine environment set out in Part XII (International Seabed Authority, 2023, paras. 52-58), as well as the specific obligation regarding pollution caused by activities in the Area should be applicable (International Seabed Authority, 2023, para. 23).

International organizations hold the similar views, such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the World Commission on Environmental Law.6 In addition, the Ocean Law Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources- World Commission on Environmental Law has expounded on the specific obligations that the Parties to the UNCLOS should undertake in the face of greenhouse gas emissions. According to the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (hereinafter referred to as the “IPCC”), the Parties should reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit the temperature rise within 1.5°C through the cooperation of all sectors in order to avoid catastrophic impacts of climate change on the marine environment. Meanwhile, the Parties should undertake the specific obligation regarding the climate pollutants. The specific obligation includes taking precautionary measures when existing scientific predictive information indicates that climate pollutants will cause irreversible damage to the marine environment, and bearing the obligations of governance and legal responsibilities to remedy the cumulative effects based on current scientific assessments and monitoring reports, such as ocean warming and ocean acidification (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources - World Commission on Environmental Law & Ocean Law Specialist Group, 2023, Chapters 2–4 and 7).

3.2.2 Positions of UNCLOS state parties

Parties to the UNCLOS have different positions on whether the emission of greenhouse gas constitutes the marine environmental pollution. There is a viewpoint that the responsibility for conduct and the responsibility for outcome can be treated separately. That is to say, the nature of all actions occurring before the assumption of the outcome responsibility is the same, and there is no conflict between them. In other words, it is to acknowledge that the emission of greenhouse gases is a common responsibility of human behaviors, which leads to the result of marine environmental pollution. Although these actions all point to the same goal- outcome responsibility, the assumption of outcome-based responsibility may vary among UNCLOS States Parties due to differences in their historical development. For example, the United Kingdom suggests that the legal implication of “pollution” and the parties’ obligations separately. It acknowledges that greenhouse gases fall within the category of the pollution of the marine environment as defined in Article 1 (1)(4) of the UNCLOS, but the specific obligations of the Parties should be considered with five relevant factors, including the standard of the due diligence, the application of the precautionary principle, the obligation of international cooperation, the concept of effectiveness and the best available science (United Kingdom, 2023, Chapter 3).

From a perspective of the treaty interpretation, some parties advocate that treaties should be interpreted strictly in accordance with the literal meanings to avoid the legal consequences of the power’s expansion and abuse caused by the expansive interpretation. For example, China opposes the inclusion of greenhouse gases within the concept of pollution of the marine environment on the ground that the UNCLOS does not mention the specific scenario of the climate change and also does not provide special authorization for related issues. The developmental interpretation of the UNCLOS should not exceed the original intention of the parties. Even, the UNFCCC does not define the anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions as the pollution (People’s Republic of China, 2023).

The aforementioned instance is based on a strict adherence to the textual interpretation. In addition, India concurred with China’s viewpoint, believing that the adverse impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the marine environment are unique and cannot be directly determined as a form of marine environmental pollution in the absence of the explicit provisions in the UNCLOS, the UNFCCC and so on. Especially, when calculating the outcome responsibilities, such as the greenhouse gas emission standards, the historical responsibilities of developed countries and the final consumption quotas must be taken into account (Telesetsky, 2023). Indonesia believes that there is insufficient legal basis for the ITLOS to recognize greenhouse gas emissions as a pollution of the marine environment, and there is a fundamental difference between greenhouse gas emissions and marine environmental pollution (Indonesia, 2023).

3.2.3 Opinion of ITLOS

In ITLOS Case No. 31, ITLOS believed that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions constitute marine environmental pollution. The Tribunal took the approach of teleological interpretation and understood the protection of the marine environment from the perspective of the legislative objective and spirit of the UNCLOS accompanied with Article 31, paragraph 1 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (hereinafter referred to as the “VCLT”). It stated that the negative effects of the ocean warming, acidification, and sea-level rise caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are highly consistent with the definition of marine environmental pollution in Article 1(1)(4) of the UNCLOS. All the parties should comply with the obligations stipulated in the UNCLOS, including taking “all necessary measures” to prevent, reduce and control greenhouse gas emissions from any source (ITLOS, 2024, paras. 60-62).

After reviewing the IPCC’s assessment reports on climate change, ITLOS bypassed a crucial step—providing a clear definition of “pollution of the marine environment” under the UNCLOS. Instead (IPCC, 2018; 2019a; 2023), it invoked the legislative intent of the UNCLOS to emphasize the importance of fulfilling States Parties’ obligations in addressing global warming (Eggleston et al., 2006; Masson-Delmotte et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2024). 7 Consequently, ITLOS’s conclusion that greenhouse gas emissions fall within the scope of marine environmental pollution may give rise to debate regarding the comprehensiveness of its legal reasoning and adherence to treaty interpretation. It remains to be seen whether this interpretation of “pollution of the marine environment” will be accepted and directly cited by other international adjudicative bodies, or whether it will provoke further controversy in future judicial practice.

3.3 Legal application: the relationship between the UNCLOS and other treaties

In addition to the application of the UNCLOS, ITLOS Case No. 31 also engages the UNFCCC (Barnes, 2022; Doelle et al., 2024; United Nations, 1992), which plays a central role in addressing climate change, as well as several related instruments (Klerk, 2023), such as the VCLT and the Paris Agreement. A key task of the advisory opinion is to clarify the relationship among these international treaties in the process of determining applicable law.

3.3.1 The relationship between UNCLOS and the international legal framework on climate change

The UNCLOS broadly encompasses matters related to the ocean and establishes a comprehensive legal framework for the protection of the marine environment (Churchill et al., 2022; United Nations, 1982, Part XII). However, as climate change had not yet emerged as a prominent concern during the negotiation of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, its implications for the marine environment are not explicitly addressed in the UNCLOS (Feria-Tinta, 2023). Notably, Part XII, Section 5 of the UNCLOS emphasizes the need for states to develop both international rules and domestic legislation aimed at the prevention, reduction, and control of marine pollution, categorized by its sources. This provision implicitly underscores the interconnection between international and domestic legal obligations in the context of ocean governance and climate change, particularly from the perspective of legal sources. In this regard, the ocean constitutes an essential and inseparable component of the broader climate change discourse. Nevertheless, the UNCLOS does not directly address greenhouse gas emissions, revealing certain limitations in its capacity to comprehensively respond to climate-related threats to the marine environment.

The UNFCCC serves as the cornerstone of the current international legal framework for addressing climate change (Carlarne et al., 2016).8 Although Kyoto Protocol, Paris Agreement and other agreements are the products negotiated within the framework of UNFCCC, as legally binding agreements, these documents should be regarded as independent implementation agreements signed to achieve the goal of UNFCCC (Bigagli, 2016; Tsung-Han et al., 2020). They focus on reducing greenhouse emissions through collective action to limit their effects on the climate system and sustainable human development (Bodansky et al., 2017).

From the perspective of legal relations, the UNFCCC cannot be regarded as a treaty that concretizes the relevant provisions of UNCLOS concerning marine environmental pollution (United Nations, Study Group of the ILC, 2006a). The two are neither in a general law–special law relationship (ITLOS, 2024, para.224) nor in a relationship of earlier law versus later law (Dörr and Schmalenbach, 2018). 9

It must be acknowledged that the UNCLOS and the international legal regime on climate change exhibit a relationship of compatibility and complementarity in terms of objectives, norms, and institutional mechanisms (Jakobsen et al., 2020). On the one hand, Part XII and Article 237 of UNCLOS reflect an openness to other international agreements (ITLOS, 2024, para. 134). Part XII employs distinct terminology to define the scope of application and legal effect, while Article 237 provides normative support for the development of the UNCLOS, stipulating that UNCLOS shall not affect agreements—referred to as “UNCLOS without prejudice agreements”—which may be concluded in furtherance of the general principles set forth in the Convention (ITLOS, 2024, para.131; Proelss, 2017). On the other hand, the international climate change legal regime contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of UNCLOS provisions on the protection and preservation of the marine environment (United Nations, Study Group of the ILC, 2006a). For instance, the preamble of the UNFCCC underscores the importance of recognizing the roles and significance of sinks and reservoirs of greenhouse gases in terrestrial and marine ecosystems. The Kyoto Protocol conferred a mandate upon the International Maritime Organization to address the regulation of greenhouse gas emissions from the maritime sector (United Nations, 1997, Art. 2.2). 10 The Paris Agreement further emphasizes the necessity of ensuring the integrity of all ecosystems, including oceans. 11

3.3.2 Positions of UNCLOS state parties

Parties to the UNCLOS generally recognize the importance of international treaties related to climate change and domestic laws of coastal states for the protection of the marine environment. Although the countries are largely in agreement on this issue, the main argumentative bases can be divided into three different types.

Firstly, some countries argue that the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (hereinafter referred to as the “CBDR”) should be applied when considering obligations related to environmental protection. For example, China views the UNFCCC as the primary treaty framework for addressing climate change (Tol and Verheyen, 2004). Based on the CBDR principle, it advocates for strengthened international cooperation to promote integrated governance of climate and ocean-related issues in order to jointly confront the challenges of climate change (People’s Republic of China, 2023, para. 27).

Secondly, some countries frame their positions in light of their respective national capacities. For instance, Australia holds that Section 5 of Part XII of the UNCLOS, titled “International Rules and National Legislation to Prevent, Reduce and Control Pollution of the Marine Environment,” permits parties to develop domestic laws and regulations to address various sources of marine pollution, including land-based and vessel-based sources. Section 6 further provides that parties may implement regulatory and enforcement measures to ensure the effectiveness of such domestic regimes. Australia emphasizes that Part XII does not prescribe a uniform enforcement mechanism. Therefore, as long as parties comply with international rules and fulfill their obligations in good faith, they may adopt diverse regulatory approaches suited to their individual capacities (Australia, 2023, para. 54).

Lastly, some parties have invoked the preamble of the UNCLOS to recognize the relevance of the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement (Hermwille et al., 2017; Harrould-Kolieb, 2019; Dobush et al., 2022). For example, the European Union considers the Paris Agreement the most pertinent international legal instrument in this context. It holds that the Paris Agreement affirms the due diligence obligations set out in Articles 192 and 194 of the UNCLOS and aligns with the objectives of Articles 207, 212, 213, and 222 (European Union, 2023, paras. 91-94). 12

3.3.3 Opinion of ITLOS

The UNCLOS is the first global instrument related to the protection of the marine environment. However, it does not explicitly illustrate the concept of the CBDR. It is worth noting that the Tribunal mentioned the concept of the CBDR at least eight times in its advisory opinion, which represents that in the context of climate change, the Tribunal intends to establish a meaningful connection between two legal fields: the law of the sea and the law of climate change.

Based on its arguments, the Tribunal contends that the UNCLOS has clearly recognized its commitment to “realization of a just and equitable international economic order which takes into account the interests and needs of mankind as a whole and, in particular, the special interests and needs of developing countries” in the fifth paragraph of its preamble. This preferential treatment for developing countries is further reflected in the relevant provisions of Part XII of the UNCLOS. Therefore, the concepts of the CBDR and respective capabilities, as the basis of Part XII of the UNCLOS, can serve as evidence that the drafters of the UNCLOS drew on the concept of the CBDR (De Almeida and Weston, 2024).

Based on the above arguments, the Tribunal believes that the UNCLOS, as a foundational legal instrument, provides certain reference clauses that guide States Parties to take external rules into account. Moreover, Article 237 of the UNCLOS affirms the openness of the regime concerning the “Protection and Preservation of the Marine Environment,” allowing for cooperative relationships with other treaties (ITLOS, 2024, para. 132). However, the application of external rules must remain consistent with the UNCLOS (ITLOS, 2024, paras. 133-134). The Tribunal also believes that, according to Article 31, paragraph 3 (c) of the VCLT, treaties cannot be understood and applied isolated, but should be considered within the entirety of legal framework (I.C.J, 1971, para. 53). The International Law Commission mentioned that when some international norms are related to an issue, they should be interpreted as far as possible to generate compatible obligations in the report of fragmentation of international law in 2006 (United Nations, Study Group of the ILC, 2006b; International Law Commission, 2021, Guideline 9).

Finally, ITLOS believes that, the laws applicable to ITLOS Case No. 31 include the UNCLOS, the COSIS Agreement and other general rules of international law that is not in conflict with them in accordance with Article 138, paragraph 3 and Article 130, paragraph 1 of the Rules, Article 23 of the Statute and Article 293, paragraph 1 of the UNCLOS. The treaty regimes for addressing climate change, such as the UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships Annex VI, the Convention on International Civil Aviation Annex 16, and the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, can provide relevant external rules (ITLOS, 2024, paras. 123-137).

4 Legal implications of ITLOS Case No. 31

In the post-Paris Agreement era, the focus of global climate negotiations has gradually shifted from achieving political consensus to the allocation of national responsibilities and the implementation of intended nationally determined contributions (Campbell et al., 2016; Kuyper et al., 2018). However, this shift has increased the complexity of negotiations, leading to a slowdown—and in some cases, a standstill—in subsequent discussions on fulfilling the goals of the Paris Agreement. At the same time, international climate litigation faces significant practical challenges, the most prominent being the general absence of a clear mechanism for holding states accountable under existing climate treaties. 13 Against this backdrop, the involvement of the ITLOS in climate governance through advisory opinions has emerged as an important avenue for international adjudicative bodies to engage with climate change issues.

The advisory opinion in ITLOS Case No. 31 has become a highly concerned issue in the international community. Proponents argue that the advisory opinion can clarify the legal obligations of countries and help overcome the current impasse in multilateral climate negotiations among countries (Feria-Tinta, 2023). Conversely, critics contend it risks further complicating global climate governance and potentially disrupting established negotiation frameworks (Mayer, 2023a). Regardless of the arguments for and against, Case No. 31 as the world’s first advisory opinion to define the legal relationship between greenhouse gas emissions and marine environmental protection, will inevitably become an important reference for other international adjudicative bodies in addressing climate change advisory cases, due to its conclusions and patterns of legal reasoning. The key question is, what are the deeper legal implications implied by the three legal issues elaborated in Part 2 around? Whether it is possible to formulate workable legal standards from this opinion and employ them as precedents for other adjudicative bodies—such as the International Court of Justice and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights—in future climate-related advisory cases will be the focus of the following discussion.

4.1 The establishment of ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction as a full court: implied powers interpretation

ITLOS is an independent international judicial body established under UNCLOS. Whether the expansion of its jurisdictional authority can be interpreted through the doctrine of implied powers applicable to international organizations presents an interesting question (Gadkowski, 2016). This part seeks to examine the establishment of ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction as a full court through the lens of implied powers expansion. It may offer a distinct legal perspective on the legitimacy of jurisdictional expansion by international adjudicative bodies.

4.1.1 Expressed powers of ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction

As an international judicial body, ITLOS derives its advisory jurisdiction from expressed powers conferred under the “object and purpose of UNCLOS” and its “functional mandate,” as elaborated below:

First, from the perspective of objectives and purpose: The limitations of ITLOS’s mandate in addressing climate change have become increasingly evident (IPCC, 2019b; Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC, 2019). Consequently, the evolution of international judicial bodies like ITLOS is a dynamic process, marked by a gradual expansion of functions and powers, provided such development remains consistent with the institution’s founding mandate. In this context, the expansion of jurisdiction reflected in Advisory Opinion No. 21 (“Request for an Advisory Opinion Submitted by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission”) and ITLOS Case No. 31 can be understood as aligning with the objective set forth in the fourth paragraph of the UNCLOS Preamble: “promote … protection and preservation of the marine environment,” as well as the various requirement of the international community for marine affairs.

Second, from the perspective of functional mandate: ITLOS consists of two main parts, the full court and the Seabed Disputes Chamber, each of which is undertaking the corresponding legal responsibilities. According to Articles 186 and 187 of the UNCLOS, the jurisdiction of the Seabed Disputes Chamber originates from UNCLOS, and its function mainly involves disputes in the international seabed area (Oxman, 2001). The Seabed Disputes Chamber was originally designed as a department of the International Seabed Authority and later became a part of ITLOS according to the provisions of UNCLOS. According to Article 191 of UNCLOS, the Seabed Disputes Chamber can provide the advisory opinions on legal issues arising from the developer’s activities in the Area (United Nations, 1982),14 which is a special function on the grounds of “a matter of urgency” in international law.

However, the advisory opinion requested by the Commission of Small Island States in ITLOS Case No. 31 clearly extends beyond the activities of contractors in the Area, thereby raising the question of whether the ITLOS as a full court also has advisory jurisdiction. This issue arises from a potential deficiency in the express powers granted to ITLOS. According to Articles 28 8(1) and (2) of the UNCLOS, the jurisdiction of a court or tribunal encompasses disputes concerning the interpretation or application of the UNCLOS, as well as those involving international agreements related to its purposes. Notably, these provisions do not explicitly confer different forms of jurisdiction, including advisory jurisdiction. This ambiguity has fueled ongoing debate within the international legal community regarding the advisory authority of ITLOS as a full court, and constitutes the primary legal basis for the opponents’ view that the UNCLOS does not directly authorize ITLOS as a full court to render advisory opinions in such a capacity (People’s Republic of China, 2023, paras. 6-7).

4.1.2 Examining the necessary implication of implied powers

The 1949 United Nations Reparation for Injuries case is widely recognized by scholars as an important practice in which the ICJ laid the legal rationale for implied powers through an advisory opinion. According to the advisory opinion of the Reparation for Injuries case, it is clearly pointed out that in the process of legal interpretation, the United Nations is able to explain that it possesses powers beyond those explicitly stated in the Charter of the United Nations through the “necessary implication” (I.C.J, 1949). Therefore, a legitimate implied powers in the case must still be verified through the legal interpretation of the “necessary implication”. In the advisory opinion of the 1962 Certain Expenses of the United Nations case, it was pointed out that the purposes of the United Nations Charter are broad, but neither the exercise of the expressed powers of the United Nations itself nor the added powers granted for the Charter’s purposes are unlimited (I.C.J, 1962). Here, it is clearly pointed out that there should be two criteria for the “necessary implication” on which the interpretation of a legitimate implied powers depends.

First, rejecting the inference of new powers solely from the object and purpose: Inferring implied powers of an institution solely from general principles or indeterminate legal concepts—such as the object and purpose of a treaty or the mandate of an institution—carries the risk of unchecked expansion of institutional authority. This supports the doctrinal application of the least obligation principle in treaty interpretation, which emphasizes that while every part of a treaty may carry legal significance, not all provisions necessarily impose binding legal obligations. Preambles or object-and-purpose clauses, which often reflect the general direction of an international judicial body or the political aspirations of the contracting parties, tend to be drafted in vague and imprecise terms. Accordingly, interpretation of such clauses should adhere to a minimal obligation standard, and should, in principle, not give rise to legally binding obligations, nor establish new rights or duties that constrain state sovereignty (Dinstein and Tabory, 2024). Otherwise, arbitrarily interpreting the preamble and purposes of a treaty and expanding powers based on legal interpretation will easily infringe upon the sovereignty of the parties. Moreover, it goes against the spirit of international law that restriction on the exercise of national sovereignty should not be presumed.

Based on these observations, relying on the objective set out in the fourth paragraph of the UNCLOS preamble—”promote … protection and preservation of the marine environment”—as the basis for inferring that ITLOS possesses advisory jurisdiction as a full court reveals certain doctrinal weaknesses.

Second, infer new powers from the express powers: In the dissenting opinion of Judge Hackworth in the 1949 United Nations Reparations case, it was pointed out that powers not explicitly stipulated cannot be arbitrarily inferred. Implied powers should be derived from more certain legal bases like express powers. Such inference is based on the “necessity” of fulfilling the functions and duties of international bodies (Judge Hackworth, 1949, paras. 198–199). Similar views were also presented in the dissenting opinion of Judge Koretsky in Advisory Opinion on Certain Expenses of the United Nations (1962). Judge Koretsky pointed out that the pursuit of “The ends justify the means” is an unjust procedure. Therefore, he advocated that the necessary implication of the added powers for international bodies should adopt a strict interpretation stance, and it is recommended to start from the express powers in the charter of the international bodies rather than inferring from the purpose (Judge Koretsky, 1962, para. 268).

According to ITLOS Case No. 21 “Request for an Advisory Opinion Submitted by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission”, the Tribunal pointed out that the advisory jurisdiction is derived from the Tribunal’s charter and external agreements. The Tribunal cited the term “all matters” in Article 21 of the Statute, considering it the substantial legal basis for the authority to provide advisory opinions (ITLOS, 2015, para.56). The Tribunal held that although “ ‘all matters specifically provided for in any other agreement which confers jurisdiction on the Tribunal’ does not by itself establish the advisory jurisdiction of the Tribunal” (ITLOS, 2015, para. 58) if “all matters” are “disputes”, then there is no need to use the word “disputes” instead in Article 21 of the Statute. Therefore, “all matters” should include advisory opinions (ITLOS, 2015, para. 56).

The reasoning adopted in Case No. 21 by ITLOS—inferring the existence of advisory jurisdiction for the full court from its express powers—was similarly invoked in ITLOS Case No. 31,15 where it was used to address the complex question of whether ITLOS was competent to assume advisory jurisdiction in response to the request submitted by COSIS (Miron, 2023). This reflects a broader development in customary international law, whereby international adjudicative bodies are effectively declared to have powers beyond their charter as long as they meet the “necessary implication” for fulfilling of their mandated functions (I.C.J, 1949, para. 182).

4.2 When textual interpretation falls short: a systematic approach to new marine pollution concepts

At the procedural stage, the inference by ITLOS that it possesses advisory jurisdiction as a full court demonstrates the Tribunal’s ongoing dynamic and flexible evolution in responding to emerging issues such as climate change. Similarly, at the merits stage, a major challenge for ITLOS lies in determining, as a matter of legal interpretation, whether the concept of “greenhouse gas emissions”—which, on its face, falls outside the traditional scope of the law of the sea—constitutes “pollution of the marine environment” within the meaning of Part XII of UNCLOS. This determination is crucial not only for applying the relevant provisions of UNCLOS to ITLOS Case No. 31, but also for incorporating other international treaties to expand the applicable legal framework, while ensuring consistency and coherence among the relevant legal instruments.

4.2.1 Limits of textual interpretation

In the advisory opinion, ITLOS characterizes anthropogenic greenhouse gases as marine pollution. In terms of interpretation, it first uses the most basic textual interpretation as the starting point. According to Article 1 (1)(4) of the UNCLOS, “pollution of the marine environment” means introducing substances or energy into the marine environment, which (may) leads to three types of harm: “damage to biological resources, marine life, and human health”; “degradation of seawater quality”; and “reduction of environmental amenity”. Since anthropogenic greenhouse gases have been scientifically proven to meet these criteria, it is considered as a kind of marine pollution (United Kingdom, 2023, para. 30).

In fact, the scientific opinions of international institutions, organizations and experts on the marine environmental pollution caused by greenhouse gases indirectly support the rationality of ITLOS’s preliminary reliance on textual interpretation in addressing the issue of conceptual definition.16 Nevertheless, in order to avoid criticism that ITLOS has engaged in overly expansive interpretation—particularly given that the term “greenhouse gases” is not explicitly mentioned in the relevant provisions of UNCLOS—the Tribunal sought to prevent expansive textual interpretation from leading to an undue extension or abuse of its powers. Instead, ITLOS adopted a systemic interpretation by situating the relevant provisions within the broader legal framework, drawing on the overall structure, internal logic, and object and purpose of the law.

4.2.2 Systematic interpretation as a necessary complement

Although the phrase “introduction by man, directly or indirectly, of substances or energy” in the UNCLOS does not explicitly include the natural absorption by the ocean of anthropogenic greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere, it can be understood that human knowledge was limited at the time of the treaty’s drafting. With the advancement of science and technology, it should now be interpreted to include the harmful impact caused by greenhouse gas emissions (Republic of Korea, 2023, para. 12).

Existing science can prove that there is a causal relationship between climate change and anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, with the latter contributes to the formation of ocean warming and acidification (Portugal, 2023, para. 51). However, looking at the overall structure of the UNCLOS, it aims to stipulate the obligations of states to prevent, reduce and control marine environmental pollution, specifying obligations related to land-based sources (Article 207), human activities such as on the seabed development (Articles 208, 209 and 210), pollution from vessels (Article 211), and pollution from or through the atmosphere (Article 212). No provisions arbitrarily address responsibilities and obligations related to climate change (Indonesia, 2023, paras. 57-64). Thus, two preliminary conclusions can be drawn. On the one hand, greenhouse gas emissions are an emerging issue, and even if not entirely new, it is a problem that the international community has only recently become aware of. On the other hand, the international rules existed are insufficient in regulating emerging issues.

Therefore, standing at the legal framework gap created by existing international treaties and emerging issues, the solution to the problem should fully respect the will of the contracting states. International adjudicative bodies should only intervene when the interpretation of legal provisions in isolation may lead to contradictions or ambiguities, at which point it is necessary to coordinate the relationships between different laws to avoid conflicts in application. For example, in the 2019 Advisory Opinion on the UNCLOS on Human Rights and Biomedicine (hereinafter: “the Oviedo Convention”), when the European Committee on Bioethics requested the European Court of Human Rights to issue an opinion on the “protective condition” stipulated in Article 7 of the Oviedo Convention, the European Court of Human Rights held that Article 7 reflects the contracting parties’ prudent choice, and the concept of “protective condition” cannot be defined through abstract judicial interpretation but should be defined in detail in parties’ domestic laws. The specification of a treaty is essentially legislation, and judicial interpretation should not limit the decision-making space of the parties (European Court of Human Rights, 2021, para. 65). This reflects the European Court of Human Rights’ approach of systemic interpretation, which involves a holistic consideration of international conventions as higher norms, the relevant domestic laws of the contracting parties, and general legal principles, in order to ensure consistency between domestic and international legal frameworks.

In ITLOS Case No. 31, the Tribunal held that the IPCC reports reveal the causes, impacts and dynamics of pollution, providing a scientific evidence (Harrould-Kolieb and Herr, 2012). It stressed that the decision-making of contracting states is needed that needs to be supplemented. The legal source of the corresponding measures is derived from Section 5 of Part XII of the UNCLOS, which states that parties must develop international rules and domestic legislation to prevent, reduce and control marine environmental pollution based on the sources of pollution. The specific implementation is reflected in the issue of the necessary measures for countries to assess the prevention, reduction and control of marine pollution caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gases (ITLOS, 2024, paras. 207-224). For example, setting marine climate targets, mitigation and adaptation policies, establishing marine protected areas for the most affected regions, enhancing the ability of marine ecosystems to respond to climate change, and strengthening research on the impacts of greenhouse gases on the marine environment, etc (Klerk, 2023; Roberts, 2024). The “the implementation of the obligation of due diligence … according to States’ capabilities and available resources” proposed by the Tribunal is actually, means that when the UNCLOS falls short in explaining how states should fulfill their marine environmental protection responsibilities and obligations in the context of climate change, the Tribunal emphasizes the intrinsic link between the international and domestic legal provisions. It suggests implementing states’ domestic laws and policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This approach ensures consistency and coordination between international and domestic legal provisions while avoiding a narrow perspective of interpreting a specific provision of UNCLOS in isolation.

Overall, ITLOS has taken a prominent stance in ITLOS Case No. 31. In addressing the emerging issues arising from the relationship between greenhouse gas emissions and the protection of the marine environment, the Tribunal did not mechanically apply a strictly textual interpretation of UNCLOS that might yield conclusions misaligned with the UNCLOS’s legislative intent. Instead, it employed a systemic interpretative approach to analyze the broader structural and logical relationship between international and domestic legal frameworks. Although ITLOS’s suggestions are consistent with the principle of the CBDR in the UNFCCC framework, the remaining issue is how to determine different responsibility-allocation schemes according to the differences in national social, economic and development goals, which still needs to be established through negotiations among the parties (Kulovesi et al., 2012). Abstract judicial interpretation cannot replace the concretization of treaties (Eicke, 2022; European Court of Human Rights, 2021). Therefore, as ITLOS Case No. 31 adopts a systemic interpretation approach to define emerging maritime concepts, the primary challenge for future international adjudicative bodies in addressing climate-related advisory proceedings involving similarly emerging issues will be to strike a balance between ensuring more coherent legal interpretation and avoiding over-interpretation that risks exceeding judicial authority, while remaining faithful to the object and purpose of the underlying legal instruments.

4.3 Supplementing UNCLOS via external treaty interpretation

Given the nature of greenhouse gas emissions, when ITLOS Case No. 31 initiates the systematic interpretation approach to define new maritime concepts, it is like opening a Pandora’s box, which requires more external treaties to enhance the applicability of UNCLOS to climate change. Since the issue of greenhouse gas emissions essentially has gone beyond the traditional field of the law of the sea, inevitably, in the issue of legal application, ITLOS must make an interpretation through systematic interpretation, treaty coordination, and the principle of the common objectives of international law, to ensure that UNCLOS should be consistent with the relevant international legal framework in the process of the global governance of the climate change. It not only helps to fill the legal gaps in UNCLOS, but also contributes to the coherence and effectiveness of the international law.

From the perspective of the coordination among different legal frameworks, clarifying the relationship between UNCLOS and other rules of international law in dealing with the marine impacts of climate change is of great significance for enhancing the accuracy of the application of UNCLOS and ensuring its vitality (ITLOS, 2024, para. 130). Undoubtedly, both the international maritime legal framework and the international climate change legal framework have their own limitations and the issue of connection between different legal frameworks in solving the marine climate change issues. The reasons are as follows: First, the international maritime legal framework and the international climate change legal framework are two independent legal frameworks. Although UNCLOS addresses all matters related to the ocean, it does not explicitly address climate change. The international legal framework on climate change encompasses all issues related to climate change, covering geographical spaces such as land, the atmosphere, and the ocean, but it has not been adequately integrated with the various spatial regimes. Secondly, although ITLOS considers that UNCLOS and UNFCCC are the main legal instruments for addressing marine issues caused by global climate change (ITLOS, 2024, para. 67), both UNCLOS and UNFCCC have certain shortcomings (Klerk, 2023). For example, although the causes and impacts of ocean acidification can be found in both treaties, there are still no specific provisions regulating ocean acidification caused by greenhouse gases (Roland Holst, 2023).

Therefore, in ITLOS Case No. 31, ITLOS, when addressing the coordination and application of different legal regimes, recognized that aligning the interpretation of UNCLOS-related treaties with the objectives of the international climate change legal framework is essential for ensuring the coherence of international law and effectively addressing the impacts of climate change on the oceans (ITLOS, 2024, para. 136). On this basis, the Tribunal supplemented its interpretation of UNCLOS through reference to external treaties. It ultimately held that, pursuant to Article 293 (1) of UNCLOS concerning applicable law, the legal instruments forming part of the applicable law in ITLOS Case No. 31 include the UNCLOS, Article 23 of the Statute, Articles 130 (1) and 138 (3) of the Rules, and Annex VI of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships under the framework of the law of the sea, as well as, within the climate change legal regime, the UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement, Annex 16 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, and the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (ITLOS, 2024, para. 127).

5 Emerging obligations of state parties: harmonized governance of climate and ocean issues

Climate change is closely related to the vital interests of every country. Each country is both an emitter of greenhouse gases and a victim of greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, the objectives that need to be coordinated in global multilateral climate negotiations are diverse, and for certain issues, the approach of constructive ambiguity has to adopt to increase the likelihood of reaching an agreement on treaties (Bodansky and Rajamani, 2018). Climate change is fundamentally reshaping the future evolution of global ocean governance. Guided by the advisory opinion in ITLOS Case No. 31, States Parties to UNCLOS may draw lessons on enhancing the effectiveness of ocean governance by strengthening both their preventive and governance obligations.

5.1 Prevention obligations in ocean–climate response

From the perspective of prevention obligations, marine biodiversity is facing significant risks induced by climate change, including biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation. Preventing the continuation of this trend is essential for achieving global sustainable development of the oceans (Boyle, 2020; Abraham et al., 2022). It is worth noting that the obligation of prevention is fundamentally aimed at preventing legal harm in advance. The obligation of prevention is highly likely to expand the legal power, legal obligation and legal liability in the future. However, no matter what, the preventive governance model can only successfully prevent the occurrence of some legal harm. Since the obligation of prevention inevitably involves the actions or in-actions within the scope of cognition, judgment, and action capabilities of social entities, the obligation of prevention should be a reasonable preventive obligation required by common sense. It cannot force every social entity to comply with high moral standards, nor can it demand that everything meets the “zero risk” standard.

Drawing on the commitments and provisions of the climate change legal regime, UNCLOS States Parties have the opportunity to periodically update national and regional data concerning the regulation of greenhouse gas emissions, actively promote emissions reductions through all available technologies, and work toward the preservation and enhancement of marine ecosystems. Within this context, the Meeting of States Parties to UNCLOS could, guided by the framework established in Articles 192 and 197 of UNCLOS and Article 31 of the VCLT, encourage the adoption of non-binding supplementary instruments—such as “Statements of Consensus by the States Parties” or “Environmental Implementation Recommendations.” These soft law tools would serve to clarify and operationalize UNCLOS obligations related to prevention in the ocean–climate nexus. Such an approach would facilitate regular assessments of implementation effectiveness by the States Parties, enable timely adjustments, and strengthen accountability mechanisms to ensure that States fulfill their obligations and commitments as comprehensively as possible.

More specifically, the Paris Agreement requires Parties to submit updates every five years, reporting on the gap between global stocktake results and national targets, and to revise their nationally determined contributions in light of their sustainable development needs. In a similar vein, UNCLOS States Parties might consider including information on “the ocean as a greenhouse gas sink and reservoir” in their nationally determined contributions. By leveraging data and progress made through the global stocktake process, States could periodically update and coordinate their collective and individual actions to ensure consistency with their legal obligations (Australia, 2023; UNFCCC Secretariat, 2022).

5.2 Governance obligations in ocean–climate cooperation

From the perspective of governance obligations, States Parties to UNCLOS should improve relevant mechanisms for the protection of the marine environment in order to promote cooperation with the existing legal regime on climate change. Governance obligations are fundamentally concerned with ex post facto response to legal harm, and are remedial mechanisms implemented through intervention or regulatory measures during or after an event. Governance obligations and preventive obligations mentioned before are both essential and coexist over the long term. According to Article 192 of the UNCLOS, which says “States have the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment”, it does establish and confirm a general obligation for the protection and preservation of the marine environment, emphasizing the erga omnes obligations of all states in the international community. Besides, pursuant to Article 197 of UNCLOS, which provides that “States shall cooperate on a global basis and, as appropriate, on a regional basis, directly or through competent international organizations … taking into account characteristic regional features,” States should formulate rules, standards, recommended practices, and procedures for the protection and preservation of the marine environment in accordance with UNCLOS.

Moreover, because UNCLOS does not directly establish substantive standards for issues such as vessel-source and land-based pollution, and although the UNFCCC and related instruments may arguably be interpreted as constituting the “global and regional rules, standards and recommended practices and procedures” referred to in Article 212 (3) of UNCLOS, these instruments primarily address atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions. They do not set specific targets for carbon dioxide emissions contributing to ocean warming or acidification, nor do they explicitly refer to the ocean’s function as a carbon sink. This legal gap underscores the need for States Parties to develop and implement international rules specifically addressing ocean acidification, and to advance corresponding domestic legislation. Such efforts should include the adoption of national laws and regulations aimed at preventing, reducing, and controlling the impacts of greenhouse gases on the marine environment, in accordance with provisions such as Articles 194, 207, 211, and 212 of UNCLOS. A failure by a State to act in accordance with established rules and plans should be regarded as a breach of its due diligence obligation (Mayer, 2023b).

6 Conclusion

ITLOS Case No.31, as the first climate change advisory case handled by an international judicial body, not only established important legal principles in terms of procedural confirmation, definition of legal concept, and the coordination of international treaties, but also demonstrated the trend of judicialization in the international adjudicative bodies in addressing the climate change. It is worth noting that the emergence of ITLOS Case No. 31 with its potential legal implications are worth continuous attention from the international legal community.

First, regarding whether the ITLOS as a full court possesses jurisdiction, the Tribunal invoked the term “all matters” in Article 21 of its Statute, interpreting it as a substantive legal basis for its advisory jurisdiction. This interpretation represents an expansion of its powers through a doctrine of “necessary implication”. The reasoning behind such an inference merits further examination, particularly as to whether it reflects a broader trend of jurisdictional expansion by international adjudicative bodies.

Secondly, when addressing the emerging issue of greenhouse gas emissions, ITLOS began by employing a textual interpretation of Article 1 (1)(4) of UNCLOS to determine that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions meet the three criteria constituting “pollution” of the marine environment. However, given that UNCLOS does not explicitly mention greenhouse gases, the Tribunal proceeded with a systemic interpretation, drawing on IPCC scientific reports and principles of international environmental law to emphasize that UNCLOS obligations on pollution prevention and control should extend to such novel sources of pollution. This interpretative approach contributes to filling the normative gap in the international law of the sea regarding climate change, and offers a potential model for international adjudicative bodies in addressing emerging global environmental challenges. Nonetheless, a critical question remains: will the interpretative approach adopted in Advisory Opinion No. 31 influence the application of law by the International Court of Justice or other environmental tribunals in future cases? In the long term, how to ensure the coherence of international law while preventing the excessive expansion of powers by international adjudicative bodies will become an increasingly pressing issue.

Thirdly, in ITLOS Case No. 31, ITLOS systematically integrated the UNCLOS with UNFCCC and other international environmental law treaties for the first time to fill the legal gap in the law of the sea regarding the climate change. This approach ensures the applicability of UNCLOS within the broader climate governance framework, enhances the coherence of the international legal framework, and helps to avoid conflicts between different legal regimes. It demonstrates the crucial role of judicial interpretation in filling legal gaps, especially by expanding the traditional scope of the law of the sea to address new and evolving global challenges.

As a conclusion, this study argues that the interpretative approach adopted by ITLOS in Advisory Opinion No. 31 not only enhanced the applicability of UNCLOS to climate change issues but also contributed to greater coherence in international law when addressing cross-cutting challenges. However, several questions remain that warrant further observation:

1. Will the legal reasoning and interpretative method used by ITLOS to define greenhouse gas emissions as a form of marine pollution influence the jurisdiction and scope of law applied by other international adjudicative bodies in future climate-related cases?

2. How can external treaties be appropriately incorporated into UNCLOS-based adjudication while preserving the core framework of UNCLOS and avoiding concerns over judicial overreach?

3. Looking ahead, should UNCLOS be formally amended—or should additional implementing agreements be developed—to explicitly define the climate-related obligations of States Parties, rather than relying solely on judicial interpretation? 17

Overall, the dynamic interaction between the international law of the sea and international environmental law is revealed in Case No,31, providing legal support for how the UNCLOS can adapt to global environmental governance in the context of climate change. In addition, it also points out that the key in the future lies in that international adjudicative bodies need to find an appropriate balance between the power expansion and the will of the parties, in order to achieve greater coordination and effectiveness of the international law in global environmental governance.

Author contributions

WQ: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. BW: Data curation, Writing – original draft. TT: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research is funded by the National Social Science Foundations of China under contract No.23BFX154 and also supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ This study contends that the judicialization trend catalyzed by the ITLOS Advisory Opinion in ITLOS Case No. 31 is far-reaching in scope and exerts significant influence on the institutional diversity of adjudicative bodies. Accordingly, the term “international adjudicative bodies” is employed throughout this research to denote a broad spectrum of institutions, including international courts and tribunals, claims and compensation commissions, arbitral tribunals, and ad hoc dispute resolution mechanisms. These bodies are fundamentally characterized by their capacity to render decisions that are legally binding upon the parties to which they are addressed.

- ^ The normative externality in an advisory opinion means that, in the advisory procedure the international judicial body clarifies and interprets the rules of international law. These rules of international law are often of universal applicability, and their interpretation inevitably has legal effects on other states. See I.C.J, 2010, para. 44.

- ^ Since the 1980s, international society has addressed the issue related to the climate change shifting from appeals to practice. Multiple rounds of negotiations on climate change have been launched. However, there have been serious differences among countries regarding specific measures, their own mitigation and adaptation obligations, financial support, etc. At the 26th Conference of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change held in Glasgow of the United Kingdom in 2021, small island states believed that climate change had caused extreme weather, resulting in significant losses, but the international community had not taken it seriously. The demands of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) had not been fully responded to. See https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop26, last accessed on 25 May 2025.

- ^ Article 16 of Annex VI to the UNCLOS authorizes ITLOS to formulate its own procedural rules. Therefore, ITLOS has clarified the preconditions for the exercise of its advisory function in Article 138 of the Rules. See Written statement of African Union, 2023, para.71.

- ^ UNCLOS, Art. 1(4): “Pollution of the marine environment” means the introduction by man, directly or indirectly, of substances or energy into the marine environment, including estuaries, which results or is likely to result in such deleterious effects as harm to living resources and marine life, hazards to human health, hindrance to marine activities, including fishing and other legitimate uses of the sea, impairment of quality for use of sea water and reduction of amenities.

- ^ The International Union for Conservation of Nature points out that with the intensification of global climate change, the marine ecosystem is facing unprecedented threats. From the long-term monitoring data of the global ecosystem, the large-scale emissions of anthropogenic greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide are the key factors leading to these negative changes in the marine environment. The World Commission on Environmental Law states that from the perspective of legal logic and policy orientation, the negative impacts of climate change should be included in the scope of “pollution of the marine environment”. See International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources-World Commission on Environmental Law & Ocean Law Specialist Group, 2023.

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (hereinafter referred as to “IPCC”) pointed out that the risks “are higher at 1.5°C of global warming than at present but lower than at 2°C (high confidence)”. IPCC stated that: “[o]ver the 21st century, the ocean is projected to transition to unprecedented conditions with increased temperatures (virtually certain), greater upper ocean stratification (very likely) [and] further acidification (virtually certain)”. IPCC(2023) stated that “[r]isks and projected adverse impacts and related losses and damages from climate change escalate with every increment of global warming (very high confidence)” and “[i]ncreasing frequency of marine heatwaves will increase risks of biodiversity loss in the oceans, including from mass mortality events (high confidence)”. See IPCC,2018 and 2019a.

- ^ The goal of UNFCCC is to stabilize the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system, allowing ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change.

- ^ UNFCCC was formulated later than the UNCLOS, and the States Parties of the two are not exactly the same. The UNCLOS has 169 parties, and the UNFCCC has 198 parties.

- ^ Kyoto Protocol, Art. 2.2. The reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from international maritime transport is the responsibility of the International Maritime Organization (hereinafter referred to as “IMO”). IMO has become a significant implementing entity for the international community to address climate change and control greenhouse gas emissions in the maritime sector, such as organizing research on the issue of carbon dioxide emissions from ships, formulating and improving ship energy efficiency rules and greenhouse gas emission reduction strategies.