Abstract

Ecosystem Based Management (EBM) is a comprehensive way of managing fisheries and marine resources. As such, it needs a large and complex suite of concepts and tools to address a variety of problems ranging from climate change, through various forms of water pollution, to trophic interactions and social-economic sustainability. Industry, scientists, managers, and policy makers involved in the fisheries sector are the main actors in EBM. EBM objectives based on policy needs, legal requirements, and ecosystem considerations may target specific fish stocks, or encompass several ecosystem components aiming for balanced fisheries, but they need to address the trade-offs between maximizing economic gains versus sustainable fisheries and healthy ecosystems. Fishing at Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY), setting ecosystem reference points, discards ban, avoiding bycatch of protected species, habitat protection, accounting for the effects of climate change, achieving good environmental status, setting effective marine protected areas, and considering ecosystem effects from marine spatial planning, are all examples of EBM objectives. The EcoScope project aimed to address ecosystem degradation, anthropogenic impacts, and unsustainable fisheries by developing an efficient, holistic, ecosystem-based approach to sustainable fisheries management that can easily be used by policy makers and advisory bodies. The EcoScope consortium reflects an interdisciplinary advisory team of biologists, modelers, economists, and social scientists. It performed comprehensive reviews of data, data gaps, and various tools (models, indicators, management evaluation procedures). An online platform, toolbox, academy, and a mobile application are end products delivered and maintained by EcoScope to facilitate knowledge sharing, communication, and education. The EcoScope project has built modules ready to be used in the implementation of EBM, but a more direct approach by the responsible organizations, such as ICES, FAO, GFCM and the EC, is needed to set explicit and formal research and managerial frameworks for implementing and coordinating the EBM activities.

1 Introduction

The ecosystem approach to fisheries (EAF) was introduced in 2001 with the Reykjavik Declaration on Responsible Fisheries in the Marine Ecosystem (Garcia et al., 2003). While the term was not used in the Reykjavik Declaration, organizations such as the International Council for Exploration of the Sea (ICES) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations adopted EAF for incorporating ecosystem considerations into fishery management. In 2002, the World Summit on Sustainable Development determined that the EAF should be implemented by 2010 (FAO, 2003, 2008, 2009). The term ecosystem-based management (EBM) was defined in the Ecosystem Principles Advisory Panel Report to the US Congress in 1998 (US EPAP, 1998). Steps toward actual implementation of the ecosystem approach followed much later (e.g. Fulton et al., 2019; Townsend et al., 2019; Bastardie et al., 2021; Ramírez-Monsalve et al., 2021; EU, 2022a). Over the years, the management of ecosystems and fisheries has been included in the context of slightly different formulations of Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries (EAF, Garcia et al., 2003), Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM, EU, 2022a), Ecosystem Based Fisheries Management (EBFM, Craig and Link, 2023), Ecosystem Based Management (EBM, Link and Browman, 2014; Craig and Link, 2023). These formulations have some pronounced differences (Garcia et al., 2003), or describe different application levels of ecosystem management (Patrick and Link, 2015; Dolan et al., 2016); however, the multitude of similar terms creates linguistic uncertainty (Dolan et al., 2016) that might lead to confusion among stakeholders and the general public. The different types of fisheries management approaches (including Single Species fisheries management, SSFM) were addressed in EcoScope (Table 1). As EBM encompasses all other levels, further in this paper we refer to it.

Table 1

| Management type | Description | References | EcoScope applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single species fisheries management (SSFM) | Single-species stock assessments based around the surplus production and optimal exploitation concepts. | Beverton and Holt, 1957; Gulland, 1971 | Assessed over 300 stocks (and functional groups) across European Seas and provided estimates for stock specific reference points. |

| Ecosystem approach to fisheries management (EAFM) | Ecosystem factors are included in the stock assessment, while the social and political dimensions are not necessarily addressed explicitly. | Ward et al., 2002; Garcia et al., 2003; Pitcher et al., 2009 | 1) Development of the EcoScope Toolbox: fisheries scoring index (FISH) that combines fisheries and population indicators; 2) Assessment of ecosystem components: functional groups, megafauna, habitats, benthic status, marine communities. |

| Ecosystem based fisheries management (EBFM) | It recognizes the combined physical, biological, economic, and social trade-offs that affect fisheries, and the need to address these trade-offs when optimizing fisheries yields from an ecosystem context | Pikitch et al., 2004; Link, 2010; Link and Browman, 2014 | 1) Development and application of marine ecosystem models (MEMs) combining the effect of management, policy and climate scenarios on ecosystem components; 2) Analysis of social and economic indicators, value-chain, and policy optimization models. |

| Ecocentric fisheries management (ECFM) | It acknowledges the intrinsic value of marine ecosystems, regardless of human use, aiming to maintain its health, structure, and function. | Leopold, 1949; Tsikliras et al., 2023 | Development of the EcoScope Toolbox: marine ecosystem scoring index (MESSI) that incorporates several ecosystem components, including socio-economic indicators. |

| Ecosystem based management (EBM) | It characterizes the movement towards a more cooperative and holistic approach to marine resource management and includes all anthropogenic pressures to the ecosystem | Leslie and McLeod, 2007; Link and Browman, 2014; Craig and Link, 2023 | 1) Construction of the EcoScope Platform composed of homogenized and georeferenced datasets; 2) Application of the MSP Challenge Simulation Platform for the eastern Mediterranean and the western Baltic Sea including all human activities such as wind energy production, aquaculture, oil extraction, shipping, and fisheries. |

Levels of fisheries management (sensuLink and Browman, 2014) addressed in EcoScope.

Mapping of the legal base and the main policy players was one of the first tasks in EcoScope (Rodriguez-Perez et al., 2023). Several international acts are relevant to managing fisheries and ecosystems (Table 2). The identification of the EBM starts with the definition of relevant policy problems to be solved (FAO, 2003; Townsend et al., 2019, Table 3). A thorough knowledge of the existing legal and policy basis is a necessary prerequisite in this process (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2

| Legislative act | Relevance to the EBM | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| EU legislation | ||

| Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) | Lays out the rules for sustainably managing European fishing fleets and conserving fish stocks. | EU, 1970, 1983a, b, 2013 |

| Habitat Directive (HD) | Aims to achieve Favourable Conservation Status (FCS) of listed habitats and species (including 9 marine habitats, cetaceans and sea turtles). Member States must designate Sites of Community Importance (SCI)/Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), which are part of the Natura 2000 network. | EU, 1992 |

| Water Framework Directive (WFD) | Aims to achieve Good Ecological Status for all EU surface and groundwaters including marine waters. | EU, 2000 |

| Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) | The EU’s most holistic directive on protecting the marine environment aiming to achieve Good Environmental Status GES in European marine waters by 2020 through an ecosystem approach to the management of human activities in the sea. | EU, 2008 |

| Birds Directive (BD) | Aim to achieve Favourable Conservation Status (FCS) of listed bird species (including seabirds). Member States must designate Special Protection Areas (SPA) which are part of the Natura 2000 network. | EU, 2010 |

| Maritime Spatial Planning Directive (MSPD) | Common framework for maritime spatial planning in the EU; requires implementation of an ecosystem-based approach and keeping the collective pressure of all human activities within levels compatible with GES. | EU, 2014b |

| European Green Deal | Reach zero net emissions of greenhouse gases in the EU by 2050; protect, conserve, and enhance EU environment. Supplemented by the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030. | EU, 2019b, 2020 |

| EU Action plan for fisheries | Aims to contribute to getting and keeping fish stocks to sustainable levels; reduce the impact of fishing on the seabed; minimize fisheries impacts on sensitive species. | EU, 2023 |

| Other international agreements | ||

| Bonn Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) | UN treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of migratory animals and their habitats. | UN, 1979 |

| United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement on highly migratory and straddling fish stocks (UNFSA) | Establishes rights and obligations for States to conserve and manage fish stocks and associated species, and to protect marine biodiversity. | UN, 1995 |

| United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) | International framework for activities in the ocean, including conservation and sustainable use of marine resources. | UN, 1982 |

| Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) | International treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, and for fair and equitable sharing of the benefits from the use of genetic resources. | UN, 1992 |

| GFCM 2030 strategy | Common vision and guidance on achieving sustainable fisheries and aquaculture in the Mediterranean and Black Sea region. | FAO, 2021 |

Main legislative and policy acts creating the institutional basis for the EBM.

Table 3

| Legal base | EBM needs | EBM objectives | EBM tools | Management measures (MMs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFP | TAC; Maintain fishing pressure at MSY or less; Apply MSY to mixed fisheries | Maintain all stocks at MSY | Combination of SSMs and MEMs | TAC; Catch limits, Effort control |

| Discarding | Minimize discards | MEMs | Landing obligation | |

| MPAs; FRAs | Protect ecosystems through spatial regulations/MPAs | Spatial ecosystem models | MPAs and FRAs | |

| Long-term predictions of management scenarios; Strategic EBM | Recovery and sustainable fishing of all stocks in a changing environment | Long-term strategic simulations; ERPs | Adaptive management | |

| Regionalization; EBM through ACs and MSRGs | Manage regional ecosystems and fisheries | SSA, EM | Regional MMs | |

| BD | Incidental bycatch of PETS | Protect PETS | MEM | Technical devices on fishing gear; Set time and area closures |

| HD | Reduce seabed impacts; Select the most suitable areas to implement the MSFD threshold values | Protect habitat | Spatial ecosystem models | MPAs Self-controlled fishing (related to eco-labeling) |

| MSFD | Protect PETS; Define maximum allowable mortality, and find areas to protect species/life-stages | Protect PETS | Spatial ecosystem models | MPAs |

| Ensure natural ecosystem processes are not disturbed | Ensure GES | EM | Adaptive management | |

| Biodiversity indicators | Protect/enhance biodiversity | EM, Kempton’s Q, TL, Network-based indices | Adaptive management | |

| MSPD | Marine Spatial Planning | Manage fishing and ecosystems in space | EM | Adaptive management |

| Green deal | Climate change; Integrate effects in management scenarios | Mitigate climate effects | LTL models; End-to-end models | Adaptive management |

| NRR | Restoring 15% of degraded habitats by 2030 | Define and identify different habitat areas to restore | Spatial ecosystem models | MPAs |

| EU BS 2030 | Find suitable areas for the 30/10% targets | Protect ecosystems through spatial regulations/restrictions on fishing | Spatial ecosystem models | MPAs, FRAs, OECMs |

| FRAs | Protect PETS and habitat through spatial regulations | Spatial ecosystem models | FRAs | |

| GFCM 2030 strategy | Maintain fishing pressure at MSY or less; Apply MSY to mixed fisheries | Maintain all stocks at MSY | SSMs, MEMs | Multiannual plans for stocks |

International legislation addressing EBM needs, objectives, tools, and management measures to achieve them (modified from Rodriguez-Perez et al., 2023).

Abbreviations used: CFP is Common Fisheries Policy, BD is Bird Directive, HD is Habitat Directive, MSFD is Marine Strategy Framework Directive, MSPD is Maritime Spatial Planning Directive, NRR is Nature Restoration Regulation, EU BS 2030 is EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030, TAC is Total Allowable Catch; MSY is Maximum Sustainable Yield; SSMs are Single-species Models; MEMs are Marine Ecosystem Models; PETS is Protected, Endangered, and Threatened Species; MPAs are Marine Protected Areas; FRAs are Fisheries Restricted Areas; GES is Good Environmental Status; LTL is Low Trophic Level; TL is Trophic Level; ERPs are Ecosystem Reference Points; AC is Advisory Council; MSRG is Member State Regional Group; OECMs are Other Effective area-based Conservation Measures.

In the EU, the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP; EU, 1970) reformed in 2013 (CFP; EU, 2013; Tables 2, 3) provides directions that are relevant for the implementation of the ecosystem approach, in particular: the Technical Measures Regulation (EU, 2019a), the Data Collection Framework Regulation, (DCF; EU, 2017a), the Deep Sea Stocks in the North-east Atlantic Regulation (EU, 2016), and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund Regulation (EMFF; EU, 2014a; Rodriguez-Perez et al., 2023). Unlike the CFP which aims to regulate the fisheries, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD; EU, 2008; Table 2) aims to achieve Good Environmental Status (GES) through an ecosystem approach to the management of human activities, and therefore accentuates on keeping safe and healthy ecosystems and their services. Other EU regulations such as the Habitats Directive (HD, EU, 1992), the Water Framework Directive (WFD, EU, 2000), the Birds Directive (BD, EU, 2010), and the Maritime Spatial Planning Directive (MSPD, EU, 2014b), also emphasize nature protection and ecosystem management (Tables 2, 3). The EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 (EU BS 2030; EU, 2020) is a core part of the European Green Deal (EU, 2019b; Table 3). A core commitment under the BS is the expansion of protected areas to cover 30% of the sea. For fisheries, it sets the targets to maintain or reduce fishing mortality to or under Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) levels; to eliminate or reduce bycatch, particularly for sea mammals, turtles, and birds; and to tackle practices that damage the seabed. The Nature Restoration Regulation (NRR, coming into force in mid-2026; EU, 2024), as a key element of the BS, aims to restore ecosystems, habitats, and species, to enable the long-term sustained recovery of biodiverse and resilient nature, and to achieve the EU’s climate mitigation and adaptation objectives. The General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) 2030 strategy (FAO, 2021) is binding for the Mediterranean and Black Sea member countries of the GFCM, and includes targets on achieving sustainable fisheries and aquaculture and constraining by-catch of Protected, Endangered, and Threatened Species (PETS).

In this paper, we aim to review the main issues with the state-of-the-art implementation of the EBM, and to share the EcoScope project experience on that matter. The main objective of EcoScope is to pilot the EBM implementation in European seas: the Baltic Sea, the North Sea, the Bay of Biscay, the Balearic Sea, the Adriatic Sea, the Black Sea, the Aegean Sea, and the Levantine Sea. In doing so, EcoScope provides building blocks to be used in assembling the necessary science, managerial, communication, and educational frameworks in Europe.

2 EBM data

EBM needs copious data, and the issue of its scarcity has been raised on a number of occasions (Murawski, 2007; Patrick and Link, 2015; Heymans et al., 2020; Rodriguez-Perez et al., 2023). Data gaps were also found to be a significant barrier reducing the statistical and explanatory power, as well as the predictive ability of models needed in EBM (Heymans et al., 2020). Given the call for more and better data, EcoScope aimed to identify and fill gaps in biological, fisheries, ecological, and socio-economic knowledge across marine ecosystem components and models (Supplementary Material (SM), Abucay et al., 2023; Kesner-Reyes et al., 2025). A short description of the fisheries, ecological, and socio-economic data required for EBM and their deficiencies are presented in the SM.

3 EBM tools

3.1 Fisheries models and indicators

Single stock assessment models (SSMs) are in use with EBM, together with single stock management practices of MSY and total allowable catch (TAC), as well as management strategy evaluations (MSEs) based on operational SSMs. In addition, SSMs are used to produce input data for multi-species and marine ecosystem models (MEMs), bio-economic models, and ecosystem MSE. EcoScope applied tools suitable for assessing data poor stocks such as most of the stocks in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. Commercial and non-commercial fish and invertebrate stocks were assessed in the context of MSY based on a series of new tools: catch maximum sustainable yields (CMSY++; Froese et al., 2023) for commercial species with catch and survey data, and Abundance Maximum Sustainable Yields (AMSY; Froese et al., 2020) for non-commercial stocks for which catch data are lacking but time-series of survey data are available. In data rich situations, when size and/or age structure of catches and abundance surveys are available, statistical catch-at-age models are commonly used, such as stock synthesis (SS3; Methot and Wetzel, 2013), assessment for all (a4a; Jardim et al., 2015), and yield-per-recruit analyses (e.g. STECF, 2023).

A series of community indicators were examined to assess ecosystem health and anthropogenic effects (climate and fisheries) on marine communities to complement the analysis of species distributions. These indicators include recently developed metrics such as the N90 diversity indicator, which is sensitive to both fishing and environmental impacts on diversity (Farriols et al., 2015), the BEnthos Sensitivity Index to Trawling Operations (BESITO; González-Irusta et al., 2018), and widely used indicators such as the mean weighted trophic level of the catch (mTLc), the Fishing-in-Balance index (FiB), and the Fishing Sustainability Index (FSI), which have been used to assess the effect of fisheries on marine ecosystems (Cury et al., 2005). The mean temperature of the catch has been used to evaluate the effect of climate change and variability in marine communities. The populations of sharks and rays were assessed using JARA (Just Another Red-List Assessment), which is a Bayesian state-space model that allows both process error and uncertainty to be incorporated into International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List assessments (Sherley et al., 2020). Finally, three ecosystem indicators and the accompanying thresholds were used to detect and delineate ecosystem fisheries exploitation or ecosystem overfishing: the Ryther index, the Fogarty ratio index, and the Friedland ratio index (Link and Watson, 2019). These indices rely on catch and satellite data, linking fisheries catch/landings to primary production through established constraints of trophic transfer efficiency. They have been previously applied on a global (Link and Watson, 2019) and regional scale (Link et al., 2020; Link, 2021) to determine the degree to which ecosystem overfishing may be occurring, if at all.

Implementing EBM is complex due to the many aspects that have to be considered, such as multi-species interactions, environmental/climate forcing, habitat status, human activities, and stakeholder acceptance. Marine ecosystem models (MEMs) are capable of predicting the effects of management decisions on some of these interrelated variables and can therefore make an important contribution to an effective EBM implementation. The term MEM refers to temporally and/or spatially dynamic models that simulate the marine food-web or the entire ecosystem by incorporating physical, chemical, and biological (i.e. food web) processes under the influence of natural and anthropogenic stressors (Steenbeek et al., 2021). Because models can differ in their structures and functioning, not all ecosystem models can address all EBM policy needs equally. For example, not all MEMs can address spatial issues such as MPAs, and species interactions in the models can be based on functional groups, trophic levels, or size classes, making MSY hard to address. Comprehensive overviews of how MEMs can be used to help EBM are presented by Townsend et al. (2019); Chust et al. (2022), and Craig and Link (2023).

In EcoScope, the common ecosystem modeling platform Ecopath with Ecosim (EwE; Christensen et al., 2024; De Mutsert et al., 2024) was used to create MEMs in different European Sea basins. EwE models use information on fish biomass dynamics, as well as information on other non-fish trophic groups and fisheries, to build mass balanced models (Ecopath), which are then validated as time dynamic models (Ecosim) using time series data (Christensen et al., 2024). These can be further expanded spatially with 3-dimensional spatial-temporal dynamic models (Ecospace, Steenbeek et al., 2013). EwE models can be coupled with low trophic level (LTL) models (Libralato and Solidoro, 2009; Akoglu et al., 2015) to ensure the bottom-up processes are well represented and feed into the higher trophic level interactions represented by EwE. EwE models were compiled and applied to all EcoScope case studies. Environmental and management scenarios were developed and tested in accordance with policy needs (e.g. CFP, MSFD, national policies), and to explore climate change impacts. Policy scenarios under deep uncertainty were tested in relation to future climate conditions and the impact of fisheries and non-indigenous species (NIS). The input and output data for all these models and indicators are freely available online within the EcoScope platform (https://data.ecoscopium.eu).

EcoScope also created Ecological Niche Models (ENM), which predict the actual or potential distribution of a species across a geographic area and time based on environmental and geophysical data (Coro et al., 2016). EcoScope used multiple Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based ENMs to determine the native areas of 1,508 rare and commercial fish and invertebrate species, marine mammals, and reptiles that were indexed by AquaMaps (www.aquamaps.org) as residing in the European Seas based on empirical observations (Coro et al., 2024). The ENMs included Maximum Entropy, AquaMaps, Artificial Neural Networks, and Support Vector Machines. These models were combined into species-specific ensemble models to make the best use of their complementary features and to increase ecological niche prediction accuracy. Distribution maps were produced according to IPCC Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) 4.5 and 8.5, representing future environmental projections under medium- and high-greenhouse gas emission scenarios, respectively. The resulting species distribution maps are available through the EcoScope Platform (https://data.ecoscopium.eu), and are used in assessing ecosystem models and simulations. Additionally, a biodiversity-richness map was produced from the ensemble models and published on the platform.

3.2 Fisheries socio-economic modeling

Modeling tools used for EBM (from SSMs to complex end-to-end modeling approaches) can be strengthened by: 1) re-expressing their outputs in socio-economic terms, and 2) by constraining relationships among model components using socio-economic factors (Thébaud et al., 2023). However, the use of food web models to assess the socio-economic consequences of change, albeit driven by the environment or management actions, on the fisheries systems has been very limited (Chakravorty et al., 2024). Food web models were found to be effective at characterizing the socio-economic importance of fisheries systems, and at simulating the socio-economic consequences of environmental or policy driven changes in the system. We developed an approach for assessing the socio-economic consequences in fisheries systems built upon existing capabilities of EwE: the value chain plugin (Christensen et al., 2011) and the policy search routine (Christensen and Walters, 2004). The framework aims to produce socio-economic indicators to explicitly address trade-offs among economic, social, and ecological objectives. Within EcoScope, the framework is being used to: (a) assess the consequences of alternative fishing effort restrictions on fleet profitability, fishers’ salaries, and employment contributions of Greek fleets operating in the Aegean Sea; (b) characterize the consequences of species invasions on the Israeli EEZ seafood value chain; (c) identify the consequences of fishing effort reductions across the Balearic Islands seafood value chain over time; and (d) highlight the trade-offs between existing management arrangements and fisheries policies that are optimized to maximize fisheries revenue, employment, biodiversity, or ecosystem maturity in the Aegean Sea, Balearic Islands, Baltic Sea, Israeli EEZ, and North Sea.

4 EBM implementation

4.1 Policy goals, actors and communication with stakeholders

The correct, clear, and transparent formulation of policy questions for EBM is important to kick off the implementation process (Townsend et al., 2019). Understanding policy and regulatory framework issues were mentioned as a problem in the stakeholder survey (Rodriguez-Perez et al., 2023), including weak policy frameworks for EBM, insufficient inclusion of ecosystem aspects by decision makers in requests to scientists, poor enforcement of regulations, and the complexity of different regulatory mechanisms in different countries. Identifying the policy question is often difficult and needs to be an interactive process within the existing management framework. It should be supported by the existing legislation relative to EBM (Tables 2, 3). Link et al. (2019) pointed out the different strengths of EBM-related regulations, differentiating between rather strict mandates of some protective or forbidding rules (e.g. protecting PETS), and more “relaxed” instructions (soft law, such as international law or conventions). Many EBM-related regulations seem to be holistic, and require several further steps for formulating operational measures regulating the fisheries and protecting/restoring ecosystems.

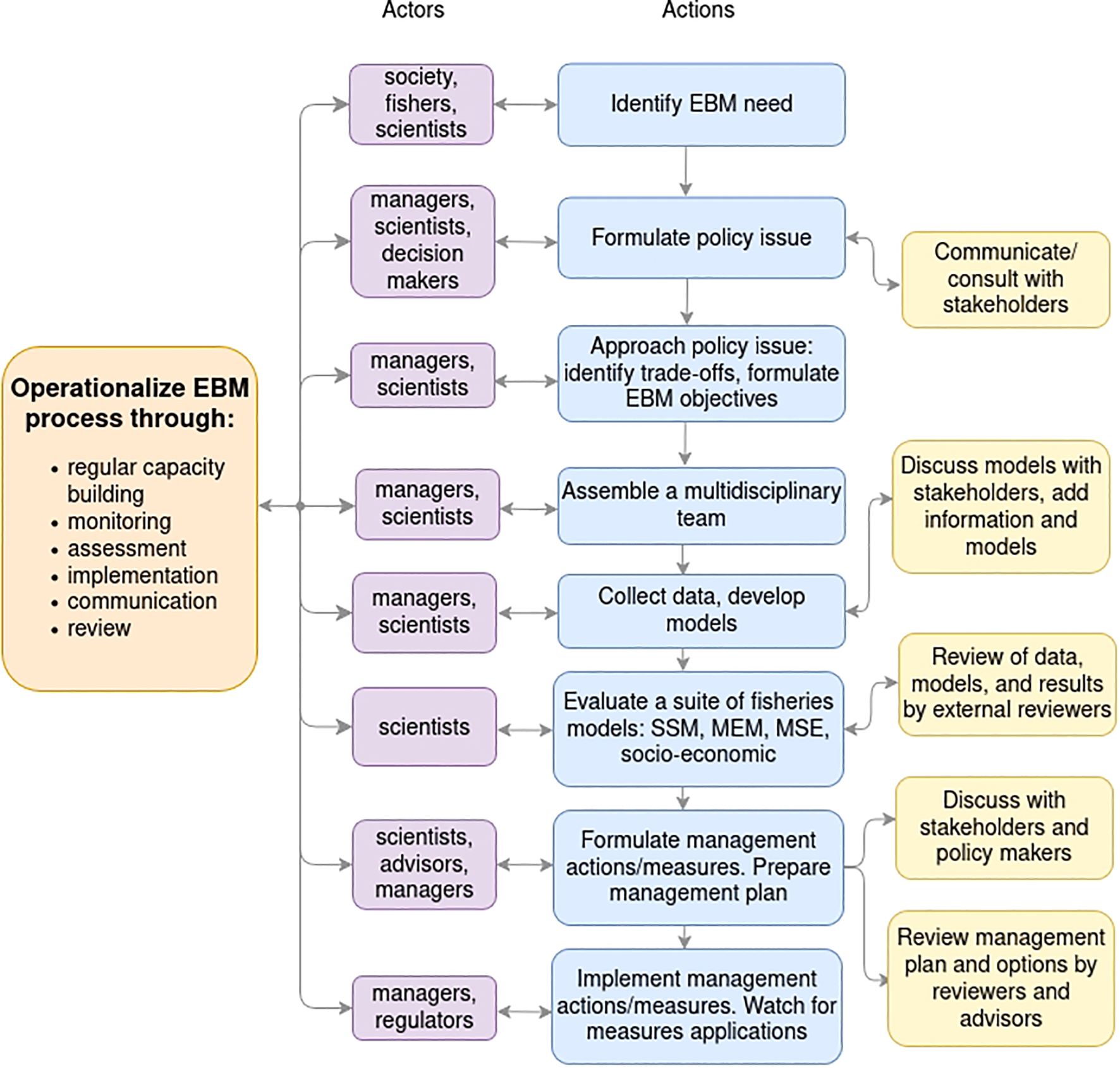

Fisheries industry, scientists, managers, and policy makers are the main actors involved in the EBM implementation (Figure 1). Their involvement is ensured through their participation in organizations (usually international and cooperative) providing advice to the EU on EBM (Figure 1; Ramírez-Monsalve et al., 2021; Rodriguez-Perez et al., 2023). Collaboration and communication between various actors are essential because they clarify objectives, promote information exchange, and facilitate the identification of trade-offs (Townsend et al., 2019). The roles and functions of the various actors are detailed in the SM. It is important to have regular open communication between various stakeholders to build trust and provide transparency of the process. This also helps the review process and mitigates the risk of model and advice rejection (Townsend et al., 2019). In the EU, the advisory councils (ACs) are a focal point of stakeholder communication because they provide experience-based information and a platform to discuss social, economic, and ecological outcomes (EU, 2017b; Ramírez-Monsalve et al., 2021).

Figure 1

Flowchart of the adaptive EBM implementation process.

The EcoScope consortium involving biologists, modelers, economists, and social scientists reflects the interdisciplinary science team needed to advise the implementation of EBM. To provide successful EBM advice, the team of scientists should include researchers, arbiters, advisers, and participatory experts (facilitators, mediators; Linke et al., 2023). However, as a team of interdisciplinary scholars, the EcoScope consortium lacks the means of collaboration with the main actors necessary for implementing project results into practice as well as directly communicate needs and tools. As it was carried out, the communication with stakeholders in EcoScope relied mostly on surveys (including workshops) rather than direct interaction. In order to provide efficient advice, the research team should participate in the decision process, ensuring that the tools produced, are tailored to purpose and contribute to EBM-related decision making. This can be achieved by associating future projects with dedicated EBM activities carried out by the ICES, GFCM, and ACs. Future projects could formally seek support for involvement in dedicated EBM efforts by the EC, ICES or other relevant organizations.

4.2 Objectives, trade-off between fisheries profits, ecosystem consideration, and societal needs

EBM objectives need to be formulated based on actual policy requirements, legal requirements, and ecosystem considerations. In some cases, they touch only on specific components of the ecosystem (e.g. the recovery of certain stocks), while in others they may encompass several components, aiming for balanced fisheries within the ecosystem, or addressing the trade-offs between sustainable fisheries and healthy ecosystems (Tables 3, 4; Rice and Duplisea, 2014). Setting double (e.g. optimize fishing, protect ecosystems) or multiple objectives (e.g. when recovering PETS, mitigating climate change, and enhancing human wellbeing are added to the first two, Table 4) unsurprisingly creates trade-offs, which need to be dealt with (Table 4).

Table 4

| MM | Objectives | Trade-offs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSY | Fishing all stocks at MSY | Maximize catch vs. overfishing less productive stocks | Mace, 2001; Rice and Duplisea, 2014; Craig and Link, 2023 |

| ERPs | Fishing all stocks at ERPs allowing to maintain desirable ecosystem state | Optimize catch and profits vs. sustain a healthy ecosystem, conserve/recover PETS | Chagaris et al., 2020; Scotti et al., 2022; Morrison et al., 2024 |

| Landing obligation | Sustainable fishing without discarding | Discards to support human uses (e.g. fish meal) vs. support for marine scavengers (birds, cetaceans). Cost of processing discards vs. revenues from fish meal | Celić et al., 2018; Moutopoulos et al., 2018; Onofri and Maynou, 2020 |

| MSY | Assess the resilience of EU fisheries to climate impacts | Maximize catch vs. reduce fishing mortality to mitigate climate effects and overfishing of stocks in poor state | EU, 2022b; Bastardie et al., 2022 |

| Regulate fishing daily | Minimize bycatch of PETS while conducting sustainable fishing | Sustain profitable fishing vs. protecting PETS | Townsend et al., 2019; Link et al., 2019; Tommasi et al., 2021 |

| MSY | Fishing at MSY vs. achieve and sustain GES | Fishing at MSY vs. achieve and sustain GES | Lynam and Mackinson, 2015; Stäbler et al., 2016; Baudron et al., 2019; Uusitalo et al., 2022 |

| MPA | Protect nature, enhance ecosystem resilience to climate change | Economic activities (incl. fishing, aquaculture, gas exploration) vs. nature conservation in Israelli EEZ, in the southeastern Mediterranean | Shabtay et al., 2025 |

| MSP | Produce green energy | Green energy vs. fishers’ access and species (mammals, birds) conservation. Fishers access vs. “reserve” and “reef” effects on ecosystem production and biodiversity | Alexander et al., 2016; Raoux et al., 2017; Lester et al., 2018; Halouani et al., 2020; Nascimento et al., 2025 |

Examples of EBM objectives, trade-offs, and management measures (MMs).

A typical trade-off discussed for a long time for multispecies fisheries (Mace, 2001; Rice and Duplisea, 2014; Trenkel, 2018) is how to fish all stocks at optimal levels simultaneously (e.g. at MSY, Table 4). It is generally accepted that fishing of all stocks at MSY (from SSM estimates) is impossible because less productive stocks tend to be overfished (Table 4, Mace, 2001; Stäbler et al., 2016; Baudron et al., 2019; Craig and Link, 2023). Significantly reduced fishing rates (by 20 - 50%) are required in order to achieve sustainable yield of all species (Stäbler et al., 2019).

An alternative of trying to optimize MSY of all species is to estimate ecosystem reference points (ERPs, Table 4, Morrison et al., 2024) for all exploited stocks that will allow optimal fishing and will simultaneously sustain desirable ecosystem state. The desirable ecosystem state may reflect various objectives defined by the managers. ERPs can be holistic (i.e. an ERP for the whole ecosystem) or individual stocks could each have an ERP to ensure that low productivity stocks are not overfished and other ecosystem components (e.g. PETS) stay healthy (Scotti et al., 2022; Morrison et al., 2024).

Discarding is a practice recognized by the stakeholders to be possibly affected by the EBM (landing obligation, LO, Table 4). Several studies demonstrate that the LO would have negative or modest effects on harvested stocks and that limiting discards may have negative effects on scavenger populations of PETS. However, discarding catch may also have other negative effects on PETS - e.g. increased incidental catch (Darby et al., 2023). A task of the EBM is therefore to accommodate a better balance between avoiding discarding practices and sustaining vulnerable ecosystem components.

The trade-off between contradicting objectives of profitable fishing and PETS protection (mammals, sharks, sea turtles, Table 4) in the California current ecosystem has for instance been accommodated by using spatial model daily forecasts (tuned by weather forecasts) allowing for the fisheries to avoid bycatch of protected PETS.

The current fisheries management frameworks can be challenged by unfavorable climate impacts, and the implementation of EBM is a way to accommodate future changes in the fisheries. There are several studies of impacts of climate on fish stocks and fisheries using MEMs (e.g. Bentley et al., 2017; Serpetti et al., 2017; Papantoniou et al., 2023), and such studies were also performed in EcoScope (e.g. Ofir et al., 2023; Keramidas et al., 2023, 2024). However, none of these describe actual management measures (MM) to mitigate climate impacts.

An EU study that evaluated the resilience of the fisheries managed under the CFP to climate change (Table 4, EU, 2022b; Bastardie et al., 2022) found that healthy and well-assessed stocks are more resilient than stocks in a poor state, and that short-lived species are more impacted, but recover quicker after climate shocks such as heat waves. Bioeconomic models (Bastardie et al., 2014; EU, 2022b) showed that fishing fleets with low profitability will not be resilient to climate-induced shocks. Climate change may lead to situations where management rules are not followed, resource resilience can be jeopardized, or fleets’ constraints are too high, affecting their economic resilience. Low fishing mortality and adaptive management may improve resilience and buffer against climate shocks, but at the cost of reducing short-term profits (Table 4).

The MSFD and the CFP are not harmonized to achieve similar ecosystem goals. Conforming to both EU policies will require the inclusion of the ecosystem effects of fishing (Baudron et al., 2019; Stäbler et al., 2016), as well as the development of specific ecological indicators and reference points that reflect the GES descriptors (Bourdaud et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2019; Ito et al., 2023). While reductions in fishing effort may lead to improvements in both the state of stocks and some GES indicators (e.g. D1-biodiversity, D4-food web; Lynam and Mackinson, 2015), trade-offs between fishery and ecosystem objectives may still occur even when fishing is sustainable (Stäbler et al., 2016; Baudron et al., 2019; Uusitalo et al., 2022). Although MEM (e.g., EwE) simulations can help reconcile conflicting policy objectives of the CFP and the MSFD, there is considerable uncertainty about how to include MSFD conservation objectives into new or existing management frameworks (van Hoof, 2015).

Establishing MPAs has a broader objective to protect marine nature, and therefore on most occasions, it is beyond the specific scope of EBM, spanning into the field of maritime spatial planning and ecosystem management. However, the restrictions on the fisheries and the conflicts between fishing and nature conservation, in general, make the MPAs subject to fisheries management and therefore to EBM (Table 4). Recently, Shabtay et al. (2025) described the efforts to propose a network of MPAs for implementation in the Israeli EEZ. The project revealed and tried to streamline substantial challenges in the MPA implementation process, such as establishing and filling information gaps, solving user conflicts (including fisheries restrictions), generating public interest and encouraging the public to endorse the project, and implementation issues such as convincing the government to accept and apply the master plan (Shabtay et al., 2025).

An example of EBM application in Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP) is the assessment of mutual effects between offshore wind farms (OWFs) and fishing (Punt et al., 2009, Table 4). The negative effects such as increased mortality of migrating marine birds (Furness et al., 2013), and increased noise and vibrations that might change long-distance spatial movement of marine mammals (Teilmann and Carstensen, 2012), are more pronounced during the early development phases. A framework combining EwE modeling, the MSP Challenge tool, and an Environmental Impact Assessment metric has been developed to capture these effects, providing a suitable means to assess ecosystem-level impacts across the construction, operation, and decommissioning phases of OWFs (Nascimento et al., 2025). Positive impacts include a “reserve effect” that increases fish biomass via the spill-over into fishing areas (Halouani et al., 2020), and a “reef effect” colonization of the installations by benthic food organisms contributing to upper trophic levels’ biomass (Raoux et al., 2017). As a result, the construction and operation of OWFs induces trade-offs between fisheries, ocean use sectors, and PETS (Lester et al., 2018).

The demand for research on the socio-economic aspects of EBM to support decision and policy making has increased, with the EU pushing towards transformative change which harnesses the power of citizens, businesses, and communities. In EcoScope, a socio-economic survey was carried out in Bulgaria, Malta, and the UK, in order to get a better understanding of the perceptions, preferences, and expectations of the public for EBM and its economic value (Briguglio et al., 2025a). Overall, the results indicated an insufficient knowledge of specific EBM terminology, yet a positive perception of the values associated with EBM, and a strong support for policy interventions.

The socio-economic analyses conducted in EcoScope demonstrated how including the human dimensions of fisheries systems in EBM can facilitate comparisons and trade-off analyses that can help assess the outcomes of policy objectives (e.g., increasing seafood contribution to national food security, improving fleet profitability, reducing unsafe subsidies, increasing female representation in seafood sector employment, among others), as well as identify which sectors, fleet segments, and countries are most vulnerable to supply side or environmental shocks, and can also help identify data gaps and inform future data collection and monitoring efforts. At present, coupling ecology and economics is a must in the provision of scientific advice for the EBM. Further integration of the biophysical and human dimensions of fisheries systems is on the agenda, needing to bring together new algorithms, mandatory socio-economic data collection, adaptive management, and cross-sector and interdisciplinary collaboration.

5 Toward operational EBM

Effective implementation of EBM requires it to be conceived and structured as an adaptive, iterative process that involves formulating policies and legislation, acquiring knowledge, developing and testing models, applying MMs, and conducting ongoing surveillance (Figure 1). The “pull-push” mechanism of demanding/providing EBM advice that currently exists in the EU cannot satisfy the needs for effective operational EBM (Ramírez-Monsalve et al., 2021). Successful operational EBM requires: 1) well-defined management objectives (Tables 3, 4); 2) a clear management process receptive to the evaluation of trade-offs; 3) a suite of well-documented state-of-the-art models; 4) early and iterative engagement among scientists, stakeholders, and managers; 5) a model development process and fusion of suitable models in a collaborative, interactive, and iterative interdisciplinary team; and 6) a rigorous and iterative review process involving independent reviewers, institutions, and stakeholders (Townsend et al., 2019; Craig and Link, 2023).

Monitoring the outcomes of implementation is critical for the effectiveness of the EBM process (Tallis et al., 2010). It involves designing and establishing monitoring programs that identify how the chosen management actions affect the management targets (Levin et al., 2009). Much of the data collected during the monitoring can be used in future EBM, allowing scientists and managers to move from data poor to data rich situations, improving the rigor and sophistication of their decisions with each iteration. When governance is stable and multiple agencies cooperate, an integrated, coordinated, and efficient monitoring program can be established across agencies. Under less ideal governance situations, where funding for monitoring is questionable or the maintenance of monitoring programs is unlikely, the monitoring program can be designed to target critical time frames or areas, or to take advantage of remote sensing. The interdisciplinary team, together with managers and stakeholders, would establish an adaptive management framework that includes existing monitoring plans. Monitoring and adaptive management plans would be integrated, and their efficiencies would be evaluated (Tallis et al., 2010).

Once the EBM process is operational, its components and subprocesses need constant iterative adaptive updating. Data collection, knowledge base, and models need to be improved and tailored through periodic workshops by interdisciplinary teams of scientists and managers. Models, recommendations, and advice need to be re-evaluated through a series of reviews at different levels (experts and stakeholders). Communication between modelers, managers, and stakeholders is essential, and would enable model and procedure refinement, and ensure their usefulness. Communication with stakeholders would enable scientists to respond to urgent and critical events by providing strategic and tactical advice for holistic planning and operational applications (Townsend et al., 2019).

6 Building of the EBM knowledge base and stakeholder involvement: EcoScope platform, toolbox, academy, app and knowledge exchange forum

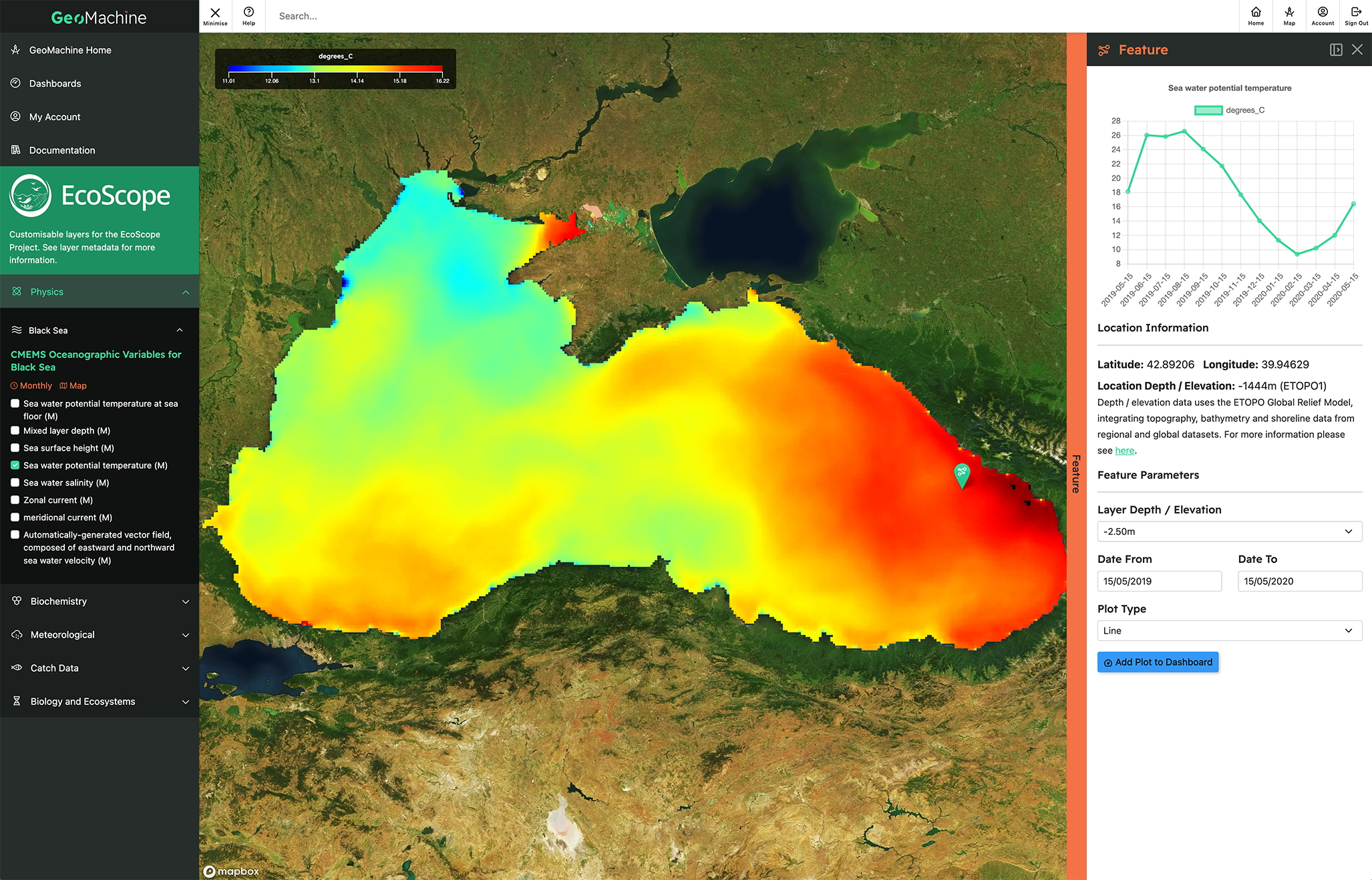

To facilitate data preservation, sharing, and usage by interested stakeholders, the EcoScope consortium developed, and will maintain in the future, the EcoScope platform (https://data.ecoscopium.eu, Figure 2), which is a key output of the project. The EcoScope platform is a geographical information system that hosts meteorological, oceanographic, biogeochemical, environmental, biological, fishery, and socio-economic datasets, and homogenizes them into common standard types and formats following international protocols. The environmental data are both historical and forecasts, cover all study areas, and are assembled, compiled, and integrated from multiple external databases and platforms such as CMEMS, EMODnet, NOAA, ECMWF, SMHI, Sentinel 2 and 3, CORDEX, IPCC. These data are combined with data from biological (e.g., FishBase, SeaLifeBase) and fisheries databases providing data on biomass, catches, and discards (e.g. GFCM, ICES, FAO, Sea Around Us project), marine mammal distribution (ACCOBAMS), biodiversity (Marine IBA e-atlas), fish and invertebrate species distributions and observations (AquaMaps, OBIS, GBIF), and fishing effort (Global Fishing Watch). All data are homogenized, georeferenced and quality checked, and form the back-end of the Ecoscope Platform (https://ecoscopium.eu/ecoscope-platform). The EcoScope platform is a modular tool linking data with environmental and human drivers, indicators, and models that couples predictions of changes in marine biogeochemistry with ecosystem productivity within a framework of climate change and increased anthropogenic forcing. The platform is based on state-of-the-art methodologies and adopts an Agile approach to ingest the diverse datasets. A series of user stories was considered for designing and providing shared services required by the external stakeholders. This platform is expected to help European decision makers in the long-term management of fishery activities, addressing pressing challenges like climate change and fisheries economy constraints.

Figure 2

The EcoScope platform illustrating the sea surface temperature (SST) distribution over the Black Sea and the temporal change of SST at a user-selected location, based on reanalysis monthly-mean data from https://marine.copernicus.eu.

The EcoScope Toolbox features a comprehensive set of standardized fisheries, community, ecosystem, and climate indicators, integrated into two unified scoring indices (one for assessing the health of fisheries and another one for assessing ecosystem health (https://ecoscopium.eu/ecoscope-toolbox, Table 1). To align with EBM principles, the toolbox also incorporates some socio-economic indicators, available as time series and specific to ecosystems rather than countries. Where feasible, the individual indicators are connected to outputs from ecosystem models (EwE), stock assessments, and various datasets on oceanography, climate, environment, and fisheries available within the EcoScope platform. The scoring indices have been co-designed and evaluated by scientists and stakeholders to assist decision-making and EBM implementation. The toolbox can be applied anywhere in the world at various scales depending on the data and boundaries, and has a set of metrics that can be used independently to support international and local policies with the EBM.

In addition, the fisheries and ecosystem information and expertise are used to assess ecosystem status and change through the maritime spatial planning (MSP) challenge simulation platform (https://www.mspchallenge.info/msp-challenge-simulation-platform.html). The MSP Challenge simulation platform is an extension of the pre-existing software platform https://www.mspchallenge.info/ applying MEMs (EwE) and incorporating dynamic ecosystem and climate conditions under deep uncertainty. It aims to engage advisers, managers and other stakeholders to carry out robust decisions and to promote adaptive management in accordance with the EU and national policies and legislation (Nascimento et al., 2025).

The EcoScope academy is the educational pillar of the project and includes a collection of online self-paced chapters contained in a course entitled “Ecocentric fisheries management” (https://ecoscope.getlearnworlds.com). The academy is addressed to postgraduate and undergraduate students, young scientists, and policymakers, building up the required knowledge for understanding the complexity and the necessity of EBM. It is used to disseminate the methodological approach of EcoScope and to transfer knowledge to all relevant stakeholders, as well as to support the proper usage of the developed platform and decision-making toolbox, and to facilitate the development and implementation of EBM policies.

The EcoScope app (https://ecoscopium.eu/ecoscope-app) is designed to empower citizens to contribute to the preservation of marine ecosystems by reporting marine hazards such as fishing in protected areas, sightings of invasive species, or marine pollution incidents.). These reports are transmitted in real time to the relevant authorities, ensuring that each issue is promptly addressed and managed. This mechanism facilitates a continuous flow of valuable data from the field, enabling stakeholders to monitor and respond to critical challenges in marine conservation. By collecting and centralizing information from users across regions, the app helps create a more comprehensive picture of activities impacting the marine environment, such as the spread of invasive species and fishing practices in ecologically sensitive areas. These data are not only instrumental in shaping immediate actions, but also serve as a valuable resource for scientists, policymakers, and governments.

The EcoScope stakeholder knowledge exchange forum (KEF) aims to achieve maximum participation, advice, and support from key ecosystem-based fisheries stakeholders to ensure the tools are useful for them and meet their needs. It comprises all stakeholders that were identified as key EBM players in the initial stakeholder mapping, as well as the stakeholders that have actively signed up via https://ecoscopium.eu/stakeholders. The results from the first stakeholder workshop have been instrumental in understanding stakeholder needs, guiding the design of the tools, and ensuring they are fit for purpose. The last workshop will showcase the final tools to all stakeholders in the KEF, and we will collect further feedback and advice on future challenges for EBM, additional needs, and how to best develop the tools further.

7 Discussion

The main objective of the EcoScope project is to help develop an efficient ecosystem-centered approach to fisheries management by providing the necessary data, tools, and communication media directly to users. With respect to this, the building of the EcoScope applications such as MEMs developed for the different sea basins and their availability for testing and use by stakeholders in the EcoScope platform, toolbox, and app were the project’s most essential outputs. This said, we can ask ourselves whether the achievements of the project are sufficient to help the implementation of EBM in Europe, and what problems and limitations we have encountered, that should be avoided in similar future efforts (Table 5).

Table 5

| EBM needs and actions | Achievements | Limitations | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| EBM data | |||

| Fisheries data | It assembled previously unused data and identified data gaps. | Some regional data were not taken into account in data-gap analyses. | To involve more regional expertise. |

| Ecosystem data | It assembled and used previously unused data and collected new data on ad hoc data needs. | Still a lot of ecosystem and socio-economic data are needed to better define and fit EBM models and indicators | To organize efficient data collection and monitoring and process previously collected raw data. |

| EBM tools | |||

| SSMs | It applied state-of-the art methods in data-limited situations to assess several commercial and non-commercial marine populations. | Data-limited SSMs are less accurate and have limited applications for fisheries management. More advanced models such as MSE can be used. | To bring in better data and apply size/age structured SSMs. To develop better fit-for-purpose indicators and models. |

| MEMs | It applied advanced MEMs in eight case studies, and made them available to users on interactive internet platforms. Run future climate scenarios and explored deep uncertainty in MEMs. | Several useful applications of MEMs were not or only partially developed: ETPs and MPAs simulations among others. | To make a better use of the developed MEMs for EBM applications. |

| Social-economic and well-being assessments | It performed surveys and coupled socio-economic models and indicators with MEMs. | Insufficient socio-economic data are hampering the ability of otherwise advanced models and algorithms to bring significant results. | Mandatory socio-economic data collection needs to be implemented in the EU MSs. |

| EBM implementation | |||

| Communication with stakeholders | It carried out surveys of EBM needs and perceptions. It developed interactive EcoScope Platform, Toolbox, app, MSP Challenge, KEF. | The project consortium was not directly involved in the decision-making process and interaction with the main EBM actors. | The project partners need to be directly involved with the dedicated assessment and advice working groups. |

| Upgrade and monitoring | It will support products and services after the life span of the project through business models for the EcoScope Platform, Toolbox, app and MSP challenge. | Supporting and interactively developing EBM knowledge base and monitoring need dedicated activities that surpass the of support of interactive platforms and apps. | The project results and experience need to be effectively transferred to operational assessment and advice working groups. |

Achievements and limitations of EcoScope, and possible future solutions.

The EcoScope project showed clear limitations (Table 4), some of which are inherent to the EBM process itself. One of them is the difficult communication of the EBM concept (Briguglio et al. 2025b). During the EcoScope survey (Rodriguez-Perez et al., 2023), stakeholders identified several barriers in implementing EBM: a lack of clarity of the EBM concept, including no common understanding of what the concept means; no guidelines on how EBM could work and be implemented; and no agreed definition, and therefore different interpretations, perceptions, and expectations among the various stakeholders. Policy and regulatory framework issues were also identified as a problem, including poor policy frameworks for EBM, insufficient inclusion of ecosystem aspects by decision makers, insufficient enforcement of regulations, and the complexity of different regulatory mechanisms in different countries. In addition, stakeholder communication issues were seen as a barrier in implementing EBM, including insufficient coordination, different mindsets, and a lack of common vision. Some of these problems can be traced back to the uncertainty in the formulation of the concepts (see Ch. 1), but others result from the mismatch between the environmental and fisheries regulations and advisory bodies with regard to EBM in the EU and elsewhere (Dolan et al., 2016; Ramírez-Monsalve et al., 2021). For example, the CFP deals mainly with fishing, and aims to sustain maximum yields, while the HD, MSFD, MSPD, and BD target environmental and biodiversity protection, and wider ecosystem management (e.g. achieving GES, setting protected zones and renewable energy projects). By trying to accommodate these diverging goals (creating perhaps impossible trade-offs), the EcoScope project (and possibly other similar efforts) is leaving the field of EBM and entering a wider field where it possibly lacks focus and sufficient expertise. The separation between environmental and fisheries regulations and advisory bodies was acknowledged by the EC, which proposed to address the harmonization of ocean policies in the new European Ocean Pact (EU, 2025).

It is clear that the EcoScope consortium’s communication with stakeholders is only indirect and therefore lacks the potential to acquire knowledge and contribute to management decisions interactively with the main actors. In future, project participants should be directly involved with the dedicated assessment and advice groups. Such involvement, however, needs to be authorized by the advisory administration in the EU, and future consortia must earn their place at the decision-making scene and gain the trust of the main actors responsible for the EBM implementation.

It is a considerable challenge to support the EcoScope products beyond the project’s life span. As mentioned in Ch. 5, operational EBM needs constant interactive updating of its policy plans, data collection and knowledge base. EcoScope aims to solve these problems by putting in place viable business models to ensure sustainable operation and update of its products and services in the future. The business models are aiming at future investments from private and public funds to ensure that the EcoScope platform, toolbox, app, and MSP challenge platform fulfill their tasks with the EBM implementation, stakeholder communication, and education.

The geographical scope of EcoScope includes eight sea basins, which have very different ecosystem, fisheries, and management properties. Although the project consortium tried to cover all areas equally, it was not possible to apply all analyses everywhere. SSM assessments and some of the MEM applications (EwE) were carried out in all areas, but others such as socio-economic value chain models were applied only to the Israeli and Balearic Islands cases, and the MSP Challenge simulations – only to the eastern Mediterranean and western Baltic Sea (Nascimento et al., 2025).

The complex nature and bulk quantity of data and tools needed make the development of EBM challenging and expensive. Data collection, identification, and filling of data gaps are essential for EBM development. Nevertheless, a shortage of certain data cannot be the reason to side step the ecosystem approach. When data are missing, modeling, scenario development, and plausible assumptions could be used to fill the gaps and to take on board ecosystem considerations.

The EcoScope project developed modules ready to be used in the EBM implementation in Europe. We feel, however, that a more direct approach should be taken by the responsible organizations, such as the European Commission and the agencies that advise the EC (ICES, GFCM), to explicitly define and set formal research and managerial frameworks for implementing and coordinating EBM activities. To do so, they need to actively communicate with key stakeholders such as the fishing industry, environmentalists, scientists, and advisors, and further develop the legal and institutional background (e.g. by adding to and/or revising the CFP and MSFD, and others) of EBM.

EBM needs a large and complex suite of concepts and tools to deal with a variety of problems ranging from climate change, through various forms of water pollution, to biological trophic interactions and social-economic sustainability. Despite certain criticisms that have been raised due to slow and sometimes badly coordinated approaches, lack of conceptual clarity, insufficient data, complex methodology, and lack of efficient communication, EBM has been developing and evolving toward operational implementation. To paraphrase W.S. Churchill’s famous quote (https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/quotes/the-worst-form-of-government) about democracy: EBM is probably not the most efficient form of management for fisheries or the ecosystem; however, we have no alternative but to maintain our ecosystems healthy and productive in order to be able to use them sustainably.

Statements

Author contributions

GD: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Sd: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SK: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MB: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. GC: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. GG: Writing – review & editing. JH: Writing – review & editing. AR: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – review & editing. GS: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AT: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article was written as part of the project “Ecocentric management for sustainable fisheries and healthy marine ecosystems – EcoScope”, which received funding from the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under Grant agreement no. 101000302. The German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (Bundesamt für Naturschutz, BfN) provided financial support to MS with funds from the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Climate Action, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMUKN), under the project AWZFISCH 4, grant agreement FKZ: 3524520800.

Acknowledgments

The authors are most grateful to the two reviewers whose comments greatly helped for the improvement of the manuscript. We thank Nikola Bobchev (IBER-BAS) for preparing Figure 1, and all partners contributing to EcoScope Work Package 2 “Efficiency of current management and gap analysis”.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1640487/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abucay L. R. Sorongon-Yap P. Kesner-Reyes K. Capuli E. C. Reyes R. B. Daskalaki E. et al . (2023). Scientific knowledge gaps on the biology of non-fish marine species across European Seas. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1198137

2

Akoglu E. Libralato S. Salihoglu B. Oguz T. Solidoro C. (2015). EwE-F 1.0: an implementation of Ecopath with Ecosim in Fortran 95/2003 for coupling and integration with other models. Geoscientific Model. Dev.8, 2687–2699. doi: 10.5194/gmd-8-2687-2015

3

Alexander K. A. Meyjes S. A. Heymans J. J. (2016). Spatial ecosystem modelling of marine renewable energy installations: Gauging the utility of Ecospace. Ecol. Model.331, 115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2016.01.016

4

Bastardie F. Brown E. J. Andonegi E. Arthur R. Beukhof E. Depestele J. et al . (2021). A review characterizing 25 ecosystem challenges to be addressed by an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management in Europe. Front. Mar. Sci.7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.629186

5

Bastardie F. Feary D. A. Brunel T. Kell L. T. Döring R. Metz S. et al . (2022). Ten lessons on the resilience of the EU common fisheries policy towards climate change and fuel efficiency - A call for adaptive, flexible and well-informed fisheries management. Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.947150

6

Bastardie F. Nielsen J. R. Miethe T. (2014). DISPLACE: a dynamic, individual-based model for spatial fishing planning and effort displacement—integrating underlying fish population models. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci.71, 366–386. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2013-0126

7

Baudron A. R. Serpetti N. Fallon N. G. Heymans J. J. Fernandes P. G. (2019). Can the common fisheries policy achieve good environmental status in exploited ecosystems: The west of Scotland demersal fisheries example. Fisheries Res.211, 217–230. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2018.10.024

8

Bentley J. W. Serpetti N. Heymans J. J. (2017). Investigating the potential impacts of ocean warming on the Norwegian and Barents Seas ecosystem using a time-dynamic food-web model. Ecol. Model.360, 94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2017.07.002

9

Beverton R. J. H. Holt S. J. (1957). On the dynamics of exploited fish populations Vol. 19 (London: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Fishery Investigations), 533 pp. Series II.

10

Bourdaud P. Gascuel D. Bentorcha A. Brind’Amour A. (2016). New trophic indicators and target values for an ecosystem-based management of fisheries. Ecol. Indic.61, 588–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.10.010

11

Briguglio M. Rodriguez Perez A. Bayo Ruiz F. Heymans S.J. J. (2025a). Citizens’ views and preferences for ecosystem-based fisheries management. EcoScope Policy Brief, published by the European Marine Board, Ostend, Belgium. Available online at: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/137131

12

Briguglio M. Ramírez-Monsalve P. Abela G. Armelloni E. N. (2025b). What do people make of “Ecosystem Based Fisheries Management”? Front. Mar. Sci.12. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1553838

13

Celić I. Libralato S. Scarcella G. Raicevich S. Marčeta B. Solidoro C. (2018). Ecological and economic effects of the landing obligation evaluated using a quantitative ecosystem approach: a Mediterranean case study. ICES J. Mar. Sci.75, 1992–2003. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsy069

14

Chagaris D. Drew K. Schueller A. Cieri M. Brito J. Buchheister A. (2020). Ecological reference points for Atlantic menhaden established using an ecosystem model of intermediate complexity. Front. Mar. Sci.7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.606417

15

Chakravorty D. Armelloni E. N. de la Puente S. (2024). A systematic review on the use of food web models for addressing the social and economic consequences of fisheries policies and environmental change. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1489984

16

Christensen V. Steenbeek J. Failler P. (2011). A combined ecosystem and value chain modeling approach for evaluating societal cost and benefit of fishing. Ecol. Model.222, 857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.09.030

17

Christensen V. Steenbeek J. Walters C. J. (2024). User guide for Ecopath with Ecosim (EwE) (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia), 294 p. Available online at: https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/eweguide/ (Accessed April 4, 2025).

18

Christensen V. Walters C. J. (2004). Trade-offs in ecosystem-scale optimizations of fisheries management policies. Bull. Mar. Sci.74, 549–562. Available online at: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/umrsmas/bullmar/2004/00000074/00000003/art00006 (Accessed April 4, 2025).

19

Chust G. Corrales X. González F. Villarino E. Chifflet M. Fernandes J. A. et al . (2022). Marine biodiversity modelling study ( EU DG Research and Innovation, Fundación AZTI, Luxembourg). doi: 10.2777/213731

20

Coro G. Magliozzi C. Ellenbroek A. Kaschner K. Pagano P. (2016). Automatic classification of climate change effects on marine species distributions in 2050 using the AquaMaps model. Environ. Ecol. Stat.23, 155–180. doi: 10.1007/s10651-015-0333-8

21

Coro G. Sana L. Bove P. (2024). An open science automatic workflow for multi-model species distribution estimation. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal 20, 1131–1150. doi: 10.1007/s41060-024-00517-w

22

Craig J. K. Link J. S. (2023). It is past time to use ecosystem models tactically to support ecosystem-based fisheries management: Case studies using Ecopath with Ecosim in an operational management context. Fish Fisheries24, 381–406. doi: 10.1111/faf.12733

23

Cury P. M. Shannon L. J. Roux J.-P. Daskalov G. M. Jarre A. Moloney C. L. et al . (2005). Trophodynamic indicators for an ecosystem approach to fisheries. ICES J. Mar. Sci.62, 430–442. doi: 10.1016/j.icesjms.2004.12.006

24

Darby J. H. Clairbaux M. Quinn J. L. Thompson P. Quinn L. Cabot D. et al . (2023). Decadal increase in vessel interactions by a scavenging pelagic seabird across the North Atlantic. Curr. Biol.33, 4225–4231.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.08.033

25

De Mutsert K. Coll M. Steenbeek J. Ainsworth C. Buszowski J. Chagaris D. et al . (2024). “ Advances in spatial-temporal coastal and marine ecosystem modeling using Ecospace,” in Treatise on Estuarine and Coastal Science, 2nd ed. ( Elsevier, Amsterdam), 122–169. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-90798-9.00035-4

26

Dolan T. E. Patrick W. S. Link J. S. (2016). Delineating the continuum of marine ecosystem-based management: a US fisheries reference point perspective. ICES J. Mar. Sci.73, 1042–1050. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsv242

27

EU (1970). Regulation (EEC) No 2142/70 of the Council of 20 October 1970 on the common organisation of the market in fishery products. Off. J. Eur. Communities236, 5–20. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/1970/2142/oj/eng (Accessed April 16, 2025).

28

EU (1983a). Council Regulation (EEC) No 170/83 of 25 January 1983 establishing a Community system for the conservation and management of fishery resources. Off. J. Eur. Communities24, 1–13. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/1983/170/oj/eng (Accessed April 16, 2025).

29

EU (1983b). Council Regulation (EEC) No 171/83 of 25 January 1983 laying down certain technical measures for the conservation of fishery resources. Off. J. Eur. Communities24, 14–29. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/1983/171/oj/eng(Accessed April 16, 2025)

30

EU (1992). Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (Habitats Directive). Off. J. Eur. UnionL206, 7–50. Available online at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31992L0043:EN:HTML (Accessed April 16, 2025).

31

EU (2000). Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for community action in the field of water policy (Water Framework Directive). Off. J. Eur. UnionL327, 1–73. Available online at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32000L0060:EN:HTML (Accessed April 16, 2025).

32

EU (2008). Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 establishing a framework for community action in the field of marine environmental policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive). Off. J. Eur. UnionL164, 19–40. Available online at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32008L0056:EN:HTML (Accessed April 16, 2025).

33

EU (2010). Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on the conservation of wild birds (Birds Directive, codified version). Off. J. Eur. UnionL20, 7–25. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/147/oj/eng (Accessed April 16, 2025).

34

EU (2013). Regulation (EU) No 1380/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on the Common Fisheries Policy, amending Council Regulations (EC) No 1954/2003 and (EC) No 1224/2009 and repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 2371/2002 and (EC) No 639/2004 and Council Decision 2004/585/EC. Off. J. Eur. UnionL354, 22–61. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2013/1380/oj (Accessed April 16, 2025).

35

EU (2014a). Regulation (EU) No 508/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 2328/2003, (EC) No 861/2006, (EC) No 1198/2006 and (EC) No 791/2007 and Regulation (EU) No 1255/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Off. J. Eur. Union149, 1–66. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/508/oj/eng (Accessed April 16, 2025).

36

EU (2014b). Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning. Off. J. Eur. UnionL257, 135–145. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/89/oj/eng.

37

EU (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/2336 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2016 establishing specific conditions for fishing for deep-sea stocks in the north-east Atlantic and provisions for fishing in international waters of the north-east Atlantic and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 2347/2002. Off. J. Eur. Union354, 1–19. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/2336/oj/eng (Accessed April 16, 2025).

38

EU (2017a). Regulation (EU) 2017/1004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2017 on the establishment of a Union framework for the collection, management and use of data in the fisheries sector and support for scientific advice regarding the common fisheries policy and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 199/2008 (recast). Off. J. Eur. Union157, 1–21. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/1004/oj/eng (Accessed April 16, 2025).

39

EU (2017b). Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/1575 of 23 June 2017 amending Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/242 laying down detailed rules on the functioning of the Advisory Councils under the common fisheries policy. Off. J. Eur. UnionL239, 1–2. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2017/1575/oj/eng (Accessed April 16, 2025).

40

EU (2019a). Regulation (EU) 2019/1241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on the conservation of fisheries resources and the protection of marine ecosystems through technical measures, amending Council Regulations (EC) No 1967/2006, (EC) No 1224/2009 and Regulations (EU) No 1380/2013, (EU) 2016/1139, (EU) 2018/973, (EU) 2019/472 and (EU) 2019/1022 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 894/97, (EC) No 850/98, (EC) No 2549/2000, (EC) No 254/2002, (EC) No 812/2004 and (EC) No 2187/2005. Off. J. Eur. Union198, 105–201. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1241/oj/eng (Accessed April 16, 2025).

41

EU (2019b). “ Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the European council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions,” in The European Green Deal. ( European Commission, Brussels). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (Accessed August 10, 2025).

42

EU (2020). “ Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions,” in EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 Bringing nature back into our lives. ( European Commission, Brussels). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52020DC0380 (Accessed August 10, 2025).

43

EU (2022a). The implementation of ecosystem-based approaches applied to fisheries management under the CFP: final report ( Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg), 110 p. Available online at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2926/57956 (Accessed August 10, 2025).

44

EU (2022b). Climate change and the common fisheries policy: adaptation and building resilience to the effects of climate change on fisheries and reducing emissions of greenhouse gases from fishing: final report (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union), 129 p. Available online at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2926/155626 (Accessed August 10, 2025).

45

EU (2023). “ Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions,” in EU Action Plan: Protecting and restoring marine ecosystems for sustainable and resilient fisheries. ( European Commission, Brussels). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52023DC0102 (Accessed August 10, 2025).

46

EU (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on nature restoration and amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869 (Text with EEA relevance). Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1991/oj/eng (Accessed August 10, 2025).

47

EU (2025). “ Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions,” in The European ocean pact. ( European Commission, Brussels). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=comnat:COM_2025_0281_FIN (Accessed August 10, 2025).

48

FAO (2003). “ Fisheries Management - 2,” in The Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries (FAO Fisheries Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries No. No. 4, Suppl. 2) ( FAO, Rome, Italy). Available online at: https://www.fao.org/4/y4470e/y4470e00.htm (Accessed August 10, 2025).

49

FAO (2008). “ Fisheries management. 2. The ecosystem approach to fisheries,” in 2.1 Best practices in ecosystem modelling for informing an ecosystem approach to fisheries (FAO Fisheries Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries No. No. 4, Suppl. 2, Add. 1) ( FAO, Rome, Italy). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i0151e (Accessed March 19, 2025).

50

FAO (2009). “ Fisheries management. 2. The ecosystem approach to fisheries,” in 2.2 The human dimensions of the ecosystem approach to fisheries (FAO Fisheries Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries No. No. 4, Suppl. 2, Add. 2) ( FAO, Rome, Italy). Available online at: https://www.fao.org/4/i1146e/i1146e00.htm (Accessed March 19, 2025).

51

FAO (2021). GFCM 2030 Strategy for sustainable fisheries and aquaculture in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea (Rome, Italy: FAO), 25 p. doi: 10.4060/cb7562en

52

Farriols M. T. Ordines F. Hidalgo M. Guijarro B. Massutí E. (2015). N90 index: A new approach to biodiversity based on similarity and sensitive to direct and indirect fishing impact. Ecol. Indic.52, 245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.12.009

53