- 1College of Literature, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Institute of Sino-Foreign Relation History, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

In ancient China, pearls were considered a luxury item and a symbol of imperial power. The competition for pearl harvesting rights was essentially an ecological and spatial contest among central imperial authority, eunuch factions, and local elites. This struggle prominently revealed the complex interactions between power, ecology, and law. The imperial state’s predatory pearl-harvesting policies led to a sharp decline in pearl oyster populations in the Beibu Gulf, exacerbating ecological pressures that triggered plagues, the displacement of Tanka people, and a surge in piracy, ultimately creating a vicious cycle of “environmental collapse–social disorder.” Although the Ming dynasty imposed strict prohibitions on private pearl harvesting, the eunuch monopoly and the breakdown of law enforcement rendered these bans ineffective. The contest between local officials and central policies further exposed the profound contradiction between the “legislative ideal” and the “governance reality” within the imperial autocratic system. By integrating local historical records with official documents, this study examines the interplay of power, resources, and ecology in the historical pearl industry of the South China Sea. Such an environmental perspective not only sheds light on institutional transformations over time but also provides historical insights into the sustainable governance of marine resources today.

1 Introduction

In ancient China, pearls occupied a near-mythical status within the hierarchy of luxury goods. Not only were they symbols of aesthetic perfection—round and lustrous like jade—but they also embodied the materialized authority of emperors. From the ritual precedent of King Wen of Zhou, who adorned his hair with pearls, to the extravagant garments of Empress Dowager Wang under Emperor Wu of Han, pearls paved the path of ultimate vanity in imperial China (Wang S., 1602). As rare treasures originating from mollusks, pearls were imbued with the value of “a thousand gold,” serving as tangible evidence of the divine mandate claimed by the ruling house.

Some Chinese scholars in antiquity named and classified pearls by their geographic origins. As Qu Dajun recorded in his local gazetteer and ethnographic New Discourse on Guangdong: “Those from the Western Ocean are called Western Pearls, those from the Eastern Ocean are called Eastern Pearls; Eastern Pearls are pale green and white, less glossy than Western Pearls; Western Pearls in turn are inferior to Southern Pearls.” (Qu, 1985) These “Southern Pearls” refer to those harvested from the southern seas of China, as also documented by the Ming (明) dynasty scientist Song Yingxing in his scientific and technological treatise The Exploitation of the Works of Nature: “All pearls in China must originate from the pools of Lei and Lian.” (Song, 2021) Lei and Lian Prefectures, under the jurisdiction of the Guangdong Provincial Administration Commission, served as the primary pearl-producing regions during the Ming, attracting consistent attention from emperors and aristocrats alike.

However, the pearl industry in these regions was soaked in blood and tears, reliant on the predatory exploitation of marine life and the systemic oppression of the “pearl people”. As the Ming dynasty represented both the zenith and a turning point in traditional Chinese maritime activities, its model of marine resource governance perpetuated this tension. The grandeur of Zheng He’s seven voyages under the banner of “pacifying distant peoples” masked the continuation of luxury trade as a means to consolidate imperial authority. Simultaneously, state-operated pearl industries, marked by cruelty, and the implementation of maritime prohibitions suppressed private initiative. This revealed the monopolistic nature of state power over the sea—pearls thus become a microcosmic specimen of Ming maritime governance. They reflected how the empire fortified its authority through resource control, while also showing how ecological depletion and popular unrest undermined the very foundations of its rule.

This study defines “maritime policy” broadly to include sea bans (haijin), the tribute trade system, the centralized administration of state-run pearl fisheries, and the use of military and legal mechanisms to enforce resource control. Anchored in the interdisciplinary frameworks of environmental history and political ecology, the paper examines how imperial resource monopolies reshaped coastal ecologies and destabilized local societies. Drawing on local gazetteers, official memorials, and administrative records, the analysis emphasizes how the overexploitation of marine resources—particularly pearls—functioned as both a symbol of sovereignty and a trigger for institutional breakdown. Rather than treating historical episodes as isolated cases, this article interprets them through a theoretical lens that highlights the interplay of symbolic power, ecological thresholds, and contestation over legitimacy in Ming marine governance.

Through a micro-historical lens focused on pearls as luxury commodities, this article examines the macro-structure of marine resource governance in the Ming dynasty, analyzing the triangular relationship among power, ecology, and extraction. It seeks to uncover the bloodstained history of laborers drowned by the tides of the South China Sea beneath the splendid epic of imperial sovereignty.

While this study draws primarily on official Ming sources—such as imperial memorials, administrative codes, and court records—it also critically considers their limitations. These documents often reflect the priorities and biases of central authority, potentially downplaying the extent of local resistance or ecological harm. To address this, the analysis incorporates local gazetteers, unofficial writings, and oral traditions (e.g., legends like “the return of pearls to Hepu”) to triangulate historical perspectives and reveal discrepancies between law and lived experience. Additionally, generative AI (ChatGPT, GPT-4) was used exclusively for language refinement and citation formatting. No interpretive content or historical claims were generated by AI tools.

2 Resource competition: pearls as political commodities

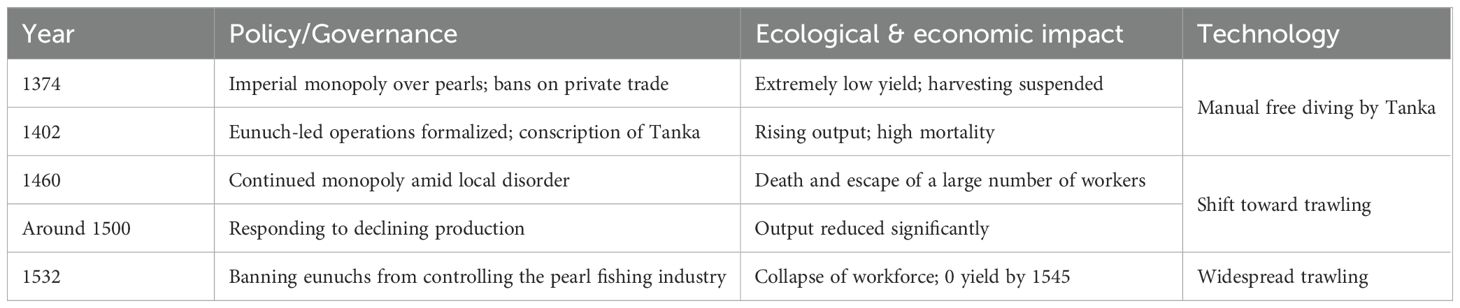

Throughout the Ming dynasty, marine policy regarding pearl fisheries exhibited a recurring pattern of divergence between centralized imperial decrees and their on-the-ground implementation. From the early Hongwu-era edicts that established state monopolies over marine resources to the Jiajing-era memorials demanding reform, the written law often clashed with administrative realities. In particular, eunuch monopolies frequently subverted formal restrictions, while local officials were at times compelled to adapt, evade, or selectively enforce imperial commands in response to ecological degradation and social unrest. This paper delineates these shifting dynamics across successive reigns, emphasizing how the widening gap between promulgated policy and practical enforcement reshaped both environmental outcomes and coastal community stability. Table 1 provides a visual overview of this evolving interplay among governance, technology, and resource extraction.

Within this contested policy landscape, pearls emerged as more than symbols of aesthetic refinement or courtly wealth. To the Ming imperial state, their rarity and radiance rendered them potent emblems of authority, with their regulated extraction serving as both a material and symbolic expression of sovereignty. Only with explicit imperial sanction could pearls from the South China Sea be harvested, and their distribution was similarly determined by the throne. Moreover, Ming China’s disputes with neighboring polities—particularly over control of the Beibu Gulf pearl beds—reveal how pearl fisheries became entangled in broader assertions of territorial jurisdiction and maritime dominance. In this sense, pearls functioned as quintessential “political commodities,” embodying the convergence of resource control, imperial legitimacy, and geopolitical contestation.

Firstly, pearls’ preciousness and beauty made them vital accessories for demonstrating imperial authority. The ceremonial regulations established in the 16th year of the Hongwu reign (1383) stipulated that the emperor’s crown was adorned with twelve strings of jade beads, each bearing five pearls (Shen and Zhao, 1587a). In the 3rd year of the Yongle reign (1405), it was decreed that the empress’s ceremonial crown—the “Nine Dragons and Four Phoenixes Crown”—should feature a large pearl held in the mouth of the central dragon. The other eight dragons and four phoenixes were similarly decorated with pearls, requiring a total of 25 pearls in different sizes (Shen and Zhao, 1587b). In the same year, the empress’s daily headwear was designated as the “Double Phoenix Supporting the Dragon Crown”, featuring a golden dragon flanked by two phoenixes holding pearls in their mouths. Other royal family members such as consorts and princes also had pearls included in their ceremonial and daily attire (Shen and Zhao, 1587c). In contrast, ordinary officials were permitted only gold and silver ornaments, not pearls—clearly demarcating pearls as symbols exclusive to imperial authority in early Ming.

Furthermore, pearls were frequently bestowed as prestigious rewards to meritorious officials. For example, when Zhu Chun, Prince of Shu and younger brother of Emperor Yongle, exposed the treasonous plot of Zhu Hui, Prince of Gu, he was rewarded with vast wealth, including 190 taels (approximately 7 kg) of pearls. (Huang, 1974; Wang, 1985a) Zhu Di also once gifted a set of pearl earrings to the mother of Zhao Yan, Minister of Rites, to honor Zhao’s filial piety (Wang, 1985b). Emperor Yingzong presented pearls as gifts to northern tribal leaders: in the 9th year of the Zhengtong reign (1444), the Ming court gave the Oirat Khan a large number of gold, silver, coral, and 100 pearls; five years later, his deputy Bayan Temur received 50 pearls and a pair of gold hoop earrings with pearls (Wang, 1985c).

Cross-border resource disputes also illustrate the linkage between resource control and national sovereignty. In the 4th year of Yongle (1406), the Ming court issued a decree prohibiting merchants in Qinzhou and Lianzhou from trading privately with the Kingdom of Annam (modern-day Vietnam). This order followed the capture of Annamese nationals led by Pham Yun, who had been illegally harvesting pearls from Chinese waters. A formal inquiry was sent to the Annamese king, who replied that some villagers in the kingdom’s eastern coastal regions had conspired with Qinzhou and Lianzhou merchants to poach pearls from the Hepu pearl beds. Annam claimed to have punished those involved. Nonetheless, the Ming reaffirmed its ban and ordered garrisons and inspection offices in Lianzhou to strengthen surveillance, mandating the arrest and trial of any future offenders and reporting directly to the central government (Zhang, 1637).

From the ceremonial use of pearls to rewards for loyal officials and strategic diplomacy, tharl clearly transcended its role as a mere luxury item in Ming society. It became a potent symbol of power, operating both domestically—to assert the legitimacy of rule—and externally—as a declaration of sovereignty. These ceremonial and diplomatic deployments of pearls demonstrate how the Ming state converted natural marine resources into instruments of symbolic domination. This aligns with political ecology perspectives that view state monopolies over ecological commodities as mechanisms for reinforcing hierarchical power structures and legitimizing authority across imperial space. As the Ming state molded pearls into political commodities through national control, it simultaneously incurred a hidden cost in the form of environmental degradation and human suffering.

3 Local resistance and collaboration

Under the pressure of centralized authority, the Ming court integrated pearl resources into the political-economic system through eunuch supervision, tax conscription, and military repression, attempting to legitimize its rule by invoking “ancestral systems.” However, this exploitative governance model incited deep contradictions and tensions within local society. As pearl harvesting turned into a brutal “life-for-pearl” reality, resistance and collaboration at the local level emerged as significant historical forces. As summarized in Table 1, key shifts in imperial policy, technological methods, and resource availability reveal a coevolving system where political ambition outpaced ecological constraints.

The court relied on eunuchs and coastal garrisons to directly control the pearl-producing marine zones—known as “pearl beds”—by conscripting Tanka households(a traditionally boat-dwelling ethnic group in southern China and reliant on fishing) to undertake the perilous diving labor. In Ming society, Tanka households were classified as jianji (low-caste) people, a hereditary status that severely restricted their economic and social rights. They were barred from owning land, excluded from most official posts, and faced prohibitions on intermarriage with higher-status groups, creating a quasi-serf relationship to the state and coastal elites. This entrenched marginalization made them especially vulnerable to compulsory conscription for hazardous marine labor. As recorded in Collected Statutes of the Great Ming (an official legal code and administrative regulations issued by the central government issued by the central government), in the 35th year of the Hongwu reign (1402), eunuchs were dispatched to recruit Tanka people for pearl harvesting in Guangdong, with grain provisions supplied (Shen and Zhao, 1587d). This method remained the primary means of labor recruitment throughout the dynasty. The work disrupted local subsistence patterns and was particularly grueling: divers faced dangerous underwater currents, shark attacks, disease outbreaks, and pirate raids (Jia, 1586). Mortality was extremely high, making resistance inevitable.

Ye Sheng, a former Governor-General of Guangdong and Guangxi, recorded in his compilation of official memorials Memorials of Lord Ye Wenzhuang that during the Tianshun reign (1457-1464), widespread deaths and desertions occurred due to piracy and plague outbreaks during large-scale pearl operations. In 1460 alone, 696 soldiers and Tanka people drowned, 237 died of disease, 55 were killed or captured by pirates, and over 2,000 deserted (Ye, 1680a). In contrast to its diplomatic outrage over Annamese poaching, the Ming court showed callous disregard for the lives of its own laborers, valuing pearls over people.

These episodes illustrate a disjuncture between imperial authority and ecological reality. As power became increasingly centralized in eunuch-led operations, the collapse of legitimacy at the local level—reflected in both overt resistance and covert collaboration—underscores what environmental historians identify as the institutional limits of top-down ecological control.

In the local gazetteer Records of Guangdong compiled by Guangdong official Guo Fei, Prefect of Lianzhou Hu Ao submitted a memorial during the Jiajing reign (1522-1566), warning that the region’s populace had been impoverished by prior pearl labor, with many still displaced. Rumors of renewed conscription prompted widespread panic and evasion. He urged against another campaign, reflecting both popular resistance and bureaucratic opposition to exploitative central mandates (Guo, 2014a).

In addition to widespread social resistance—such as the mass flight of commoners from forced labor—and the bureaucratic pushback from local officials through official memorials, the institutional structure of the pearl beds was also undermined by informal economic networks and vernacular knowledge traditions. As recorded by the Guangdong official Wu Yuancui in his Leisure Notes from the Forest Retreat (Linju Manlu, an informal literati notes and personal observations by a civil official), there were numerous cases of collusion between pearl thieves and government troops. For instance, Chen Rui, the Governor-General of Guangdong and Guangxi, allegedly orchestrated covert pearl poaching operations by commissioning criminal agents, all in order to present tributes of pearls to powerful court factions (Wu, a).

Beyond material resistance, Tanka households transmitted artisanal knowledge of pearl diving through oral folklore, forming a localized epistemology that challenged the official narrative. One Qing-dynasty compilation recorded a local proverb: “Only when the moon is full during the Mid-Autumn Festival can the sea clam swallow moonlight and conceive a pearl.” (Lu, )The spread of such legends may symbolize resistance to the exploitative burdens imposed by the state-led pearl mining campaign. By emphasizing that pearl gathering is only suitable during specific seasons (referring to the Mid-Autumn Festival), the Tanka people resisted the court’s unrestrained demand that they collect pearls, thereby reducing the oppression they suffered and, to a certain extent, maintaining the sustainability of pearl resource development.

From a theoretical standpoint, these interactions reflect what political ecologists identify as the destabilizing consequences of state-imposed resource monopolies—where ecological control becomes a site of contestation rather than cohesion. The use of coercive labor and eunuch-led enforcement produced not only material suffering but also epistemic ruptures, as vernacular knowledge systems and oral traditions began to articulate alternative modes of ecological legitimacy. In this sense, local resistance was not merely reactive, but structurally embedded in the governance failures of an imperial system that prioritized symbolic power over environmental and social sustainability. As the ecological and social costs of pearl harvesting deepened, the boundaries between enforcement and evasion, governance and disorder, became increasingly blurred. These phenomena also foreshadowing the broader systemic unraveling explored in subsequent sections.

4 Ecological feedback: how environmental change restructured power relations

The ultimate crisis of pearl fishery governance during the Ming dynasty unfolded under the dual pressures of ecological threshold breach and escalating administrative costs. After decades of extractive overexploitation, pearl oyster populations in Guangdong) neared extinction, leading to a marked and sustained decline in pearl yields. In response, the imperial court was compelled to shift its approach—from direct monopoly and state-managed extraction to a system based on delegated taxation and local intermediaries.

Yet this institutional adjustment came too late. For the marginalized Tanka household), whose livelihoods had been systematically dismantled, the collapse of the fishery economy triggered a surge in maritime banditry. These grassroots uprisings not only exposed the structural failures of the so-called “Sea Ban–Pearl Extraction” regime, but also signaled its breakdown. The resulting instability rippled through coastal society, severely undermining local order and challenging the authority of both civil and military institutions. Technological escalation played a central role in environmental degradation. As described in Diaries from Eastern Waters, early Ming divers manually collected shells, but by the mid-Ming period, dredging nets with weighted stones were dragged across the seafloor by boats—akin to modern bottom trawling. While reducing human casualties, this method devastated coral reefs and mollusk habitats, as confirmed by marine ecologists, ultimately shrinking pearl yields.

4.1 Ecological destruction caused by pearl-harvesting technology

As described in Diaries from Eastern Waters, in the early Ming dynasty, pearl oysters were harvested manually by Tanka household, aquatic laborers who relied on free diving to retrieve shells from the seabed. By the mid-Ming period, this technique had been replaced by a more mechanized—yet ecologically devastating—method. Pearl-harvesting vessels were equipped with wooden posts supporting plank-framed net mouths on both sides. Heavy stones were tied to the bottom corners of the nets, which were shaped like pouches woven from hemp rope and attached to the sides of the boat via long cables (Ye, 1680b).

During operation, the nets were dragged along the seafloor as the boat moved with the wind. When the nets grew heavy, it indicated that they had filled with oyster shells. Although this method significantly reduced human fatalities compared to diving, it inflicted severe damage on the marine environment—akin to modern bottom trawling.

According to marine ecological research, such harvesting techniques destroy coral reef structures and disturb benthic habitats, thereby reducing the living space available for mollusk populations. As a result, the production of pearls declined over time due to the destruction of their natural ecological base (Hall-Spencer et al., 2002).

By the mid-Ming period, some officials had already recognized the ecological consequences of overexploitation. According to Collected Documents of the Present Dynasty (Guochao Dianhui, an imperial document collection containing memorials, edicts, and official correspondence), Lin Fu, then serving as Governor-General of Guangdong and Guangxi, submitted a memorial warning that pearl oysters required several years after harvesting to reproduce new offspring. These offspring then needed additional years to mature, and pearls themselves could take even longer to reach marketable size and quality (Xu, 1624).

This statement indicates the elements of the Ming administration were aware of the unsustainable nature of continued extraction. However, the imperial court’s unrelenting appetite for luxury goods—pearls foremost among them—meant that such ecological warnings were ultimately ignored in policymaking. No systematic conservation measures were adopted to protect the pearl resource.

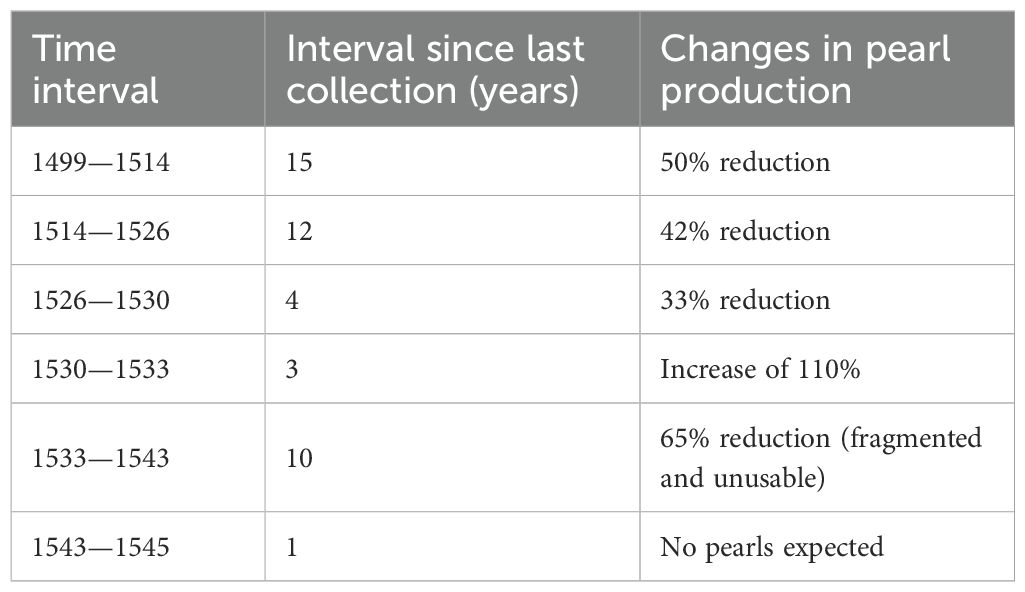

Data compiled from local records in Guangdong during the Ming dynasty provide a more intuitive representation of this ecological decline. The two tables show that as marine ecosystems deteriorated, total pearl production steadily decreased, while the financial cost per unit of pearl increased significantly. This reflects not only resource scarcity but the broader economic inefficiency resulting from ecological degradation. For detailed data, please refer to Tables 2, 3 (Huang, 1561).

Table 2. Statistics on pearl harvesting production and costs in Guangdong Province during the Ming dynasty.

The data presented in Tables 2, 3 reinforce these qualitative observations with a clear pattern of ecological and economic decline. Over successive decades, as harvesting methods became increasingly destructive, pearl production decreased markedly while extraction costs soared. Table 2 shows a steady increase in silver required per unit of pearl yield, and Table 3 highlights the accelerating depletion of oyster populations, culminating in a complete collapse by 1545. These trends illustrate the diminishing returns of extractive overreach and set the stage for the socio-ecological crisis detailed in the next section—where environmental degradation catalyzed labor collapse, population displacement, and administrative breakdown.

4.2 The vicious cycle of environment and population

The ecological crisis brought about by the Ming dynasty’s official pearl-harvesting policies not only resulted in the depletion of natural resources but also triggered a series of grave societal consequences—forming a vicious cycle of “environmental degradation, population attrition, and social disorder.” A particularly illustrative case is recorded in Memorials of Lord Ye Wenzhuang (Ye Wenzhuang Gong Zouyi), which documents the catastrophe of the 5th year of the Tianshun reign (1461).

That year, due to repeated pirate incursions, pearl harvesting at the Baisha fishery was temporarily suspended. When operations resumed in the late winter and early spring, the return coincided with the spread of miasmatic diseases, leading to a major epidemic. According to the memorial report, in the single area of Yong’an, thousands of pearl workers drowned, died from illness, were killed, or fled. The mortality was particularly severe. Additional reports from counties such as Leizhou, Suixi, Xuwen, and Haikang stated that over 10,000 pearl workers had either perished due to disease or escaped and never returned, indicating that the local pearl-harvesting labor force was nearing collapse (Ye, 1680b).

Natural disasters—including violent storms, epidemic outbreaks, and rampant piracy—interwove with the already critical scarcity of pearl resources due to ecological degradation. Together, these factors pushed the socio-ecological system of the pearl beds to the brink. Local officials, confronted with escalating disorder, were compelled to recommend emergency policy adjustments, including suspending further harvesting activities and deploying military forces to protect and stabilize extraction zones.

Moreover, a memorial recorded in the History of the Ming Dynasty (official dynastic history) by Guo Honghua, who served as Vice Minister of the Court of Imperial Sacrifices in the 11th year of the Jiajing reign (1532), reveals the systemic consequences of the pearl-harvesting regime on a macro-political level. Guo explicitly warned that the excessive conscription of commoners in Guangdong for pearl harvesting had provoked desperate resistance among the local population. Some were driven to take up arms and even launched an attack on the county seat of Xinhui (Zhang, 1974a).

His memorial identified the causal link between resource exhaustion, coercive labor policies, and the eruption of social violence—particularly among the Tanka household, a marginalized coastal community historically plagued by the demand for pearls. As pearl beds entered ecological collapse, regular harvesting operations became increasingly untenable. In turn, displaced coastal dwellers—deprived of subsistence—resorted either to clandestine poaching or transformed into bandit groups, posing a direct and escalating threat to imperial authority.

Taken together, these developments reveal that the Ming dynasty’s pearl-harvesting regime failed to contract in response to the ecological limits of natural resource capacity. Instead of implementing restraint, the state—under the dominant influence of eunuch administrators, powerful court officials often drawn from the ranks of palace servants and entrusted with maritime oversight—continued to exert extractive pressure on depleted environments. This persistence ultimately triggered a compound crisis: exceptionally high mortality rates among pearl laborers, a sharp increase in displaced populations, and the deterioration of local security conditions around the pearl beds.

Ecological exhaustion and social disorder thus formed a mutually reinforcing cycle. Environmental collapse exacerbated labor instability and criminality, while the resulting social disintegration made ecological management even more difficult. This feedback loop culminated in a triple failure of “environment–population–security”, a systemic breakdown that exemplifies the recursive vulnerability of extractive regimes in the absence of adaptive governance.

4.3 Redefining the boundaries of power

To understand how these systemic failures translated into institutional erosion, we now turn to the legal frameworks underpinning Ming marine governance.

Throughout the Ming dynasty, the governance of pearl beds was marked by a dynamic power struggle among the central court, eunuch administrators, and local authorities. Eunuchs in the Ming court derived their authority through direct imperial appointment rather than the civil service hierarchy, operating outside the usual checks on bureaucratic power. This extra-legal status allowed them to invoke the emperor’s name to command resources, override civil officials, and enforce policies with minimal institutional oversight—conditions that often amplified local resentment and policy distortion.

The boundaries of administrative control were not static but continuously redefined through contestation and crisis. A notable shift occurred in the early Jiajing reign, when the status of certain pearl beds began to change—from tightly restricted imperial monopolies to zones administered under a form of local stewardship. While still nominally under imperial ownership, these areas increasingly relied on local officials or intermediaries to manage extraction and labor, reflecting a pragmatic compromise between central authority and local capacity. This change marking the decentralization of ecological powers in response to administrative pressure and environmental degradation.

As documented in both the Collected Documents of the Present Dynasty and the Records of Guangdong (Yue Da Ji), the preceding Zhengde reign (1506-1521) had witnessed the height of eunuch dominance. Empowered by imperial favor, eunuchs frequently invoked the emperor’s name to authorize pearl-harvesting operations in Guangdong, particularly along the coast of the Beibu Gulf. These activities severely disrupted the livelihoods of local fishing communities, undermined coastal order, and placed enormous pressure on the peasantry and pearl workers (Xu, ) (Guo, 2014b).

In the memorial Proposal on Reinforcing Frontier Defense to Alleviate Civil Distress (Ti Wei Zhong Bianfang Yi Su Minshi, a policy memorial submitted to the throne by official Wang Hong), the official Wang Hong offered a more detailed critique. He denounced the supervising eunuchs for abusing their authority and fabricating criminal narratives—falsely accusing merchant ships of transporting pearl thieves, and alleging that local civilians had been coerced into hiding stolen treasures (Jia, 1586). These so-called imperial envoys, who were nominally tasked with securing the maritime frontier, in reality plunged local society into chaos. Maritime trade routes were destabilized, and the daily lives of coastal populations were thrown into panic and confusion.

During this period, the pearl beds were effectively privatized by the eunuch faction. Once public imperial resources, they became instruments of personal privilege and profit, violating the institutional boundaries established under Ming centralization. The result was not merely bureaucratic overreach, but a fundamental erosion of the political norms that underpinned imperial authority.

At the outset of the Jiajing reign (1522-1566), a wave of reform accompanied the ascension of the new emperor. In response to widespread petitions from civil officials (including local and central officials), the court initiated a comprehensive restructuring of the pearl fishery administration. One of the key measures was the abolition of the position of Junior Supervisor of the Pearl beds, a role often held by eunuchs. Lin Fu, then Governor-General of Guangdong and Guangxi, submitted a memorial explicitly recommending the complete removal of eunuch oversight from pearl governance—a proposal that was ultimately approved by the throne (Guo, 2014c).

This large-scale dismissal of eunuchs associated with pearl operations was met with widespread approval among the local populace. For coastal communities long subjected to the arbitrariness and exploitation of eunuch-led harvesting campaigns, the reform signaled a long-awaited reprieve. To many, it marked the end of a dark era in which eunuch officials had wreaked havoc on regional economies and social life. For a brief period, the governance of the pearl beds appeared to return to a public administrative framework—suggesting a partial restoration of rationalized, locally attuned ecological management.

For a brief period, pearl bed governance returned to a more structured administrative framework—suggesting a partial restoration of rationalized, locally attuned ecological management. Yet paradoxically, the removal of corrupt eunuch oversight disrupted a shadow economy that had informally supported local livelihoods. By tacitly permitting illicit extraction, accepting bribes, and selling surplus pearls, eunuchs enabled a semi-tolerated market that lowered transaction costs and involved local divers, artisans, and traders. While extractive and unstable, this unofficial system created economic incentives for locals to maintain sustainable yields. The Jiajing reforms, by curbing this corruption and centralizing control, reinforced pearls’ status as political tribute, effectively severing local access. As a result, local society lost the economic autonomy generated by pearls, and pearl collection was once again transformed into a production activity to meet the court’s demand for luxury goods. The collection without restraint and protection awareness under government decrees exacerbated the vicious cycle of environmental degradation and social collapse. This reinforces the broader contradiction between centralized imperial monopoly and ecological sustainability.

However, a few years later, eunuchs once again seized control of the pearl beds, and innocent civilians were once again conscripted to collect pearls—a luxury item considered unnecessary. The Jiajing Emperor, having first suppressed the informal economy associated with pearl collecting, then forced these former informal participants to risk their lives collecting pearls, naturally sparked greater resentment in local society. This renewed expansion of power infringed upon the interests of local society, sparked tensions between local officials and the imperial court, and reflected the distortion and abuse of the emperor’s decrees in their implementation at the local level.

Against this backdrop, local society began to exhibit a tendency toward localized understandings and interpretations of ecological governance. The Ming scholar Wu Yuancui, in his work Linju Manlu, recorded the story of “the return of pearls to Hepu”, which carried strong symbolic significance. He cited a legend from the Eastern Han dynasty, in which, during Meng Chang’s tenure as governor of Hepu, the abolishment of excessive pearl harvesting led to the reappearance of pearl-producing mollusks that had long vanished from the area. Through a ritualistic eulogy, the narrative posed a reflection: “Pearls, being small and seemingly insentient, appear to lack awareness. But if they are truly insentient, why do they reappear once overharvesting ceases? And if they are sentient, why do they continue to grow despite today’s reckless exploitation?” (Wu, b).

This allegorical account was not only a symbolic expression of laborers’ hope for divine intervention by Meng Chang to relieve their suffering, but also served to construct a form of “ecological legitimacy” rooted in local historical memory and cultural symbolism. Amidst the ecological collapse triggered by state-led pearl harvesting, local gentry invoked this Eastern Han legend to reinforce the principle of sustainable resource use, thereby shifting the basis of governance legitimacy from imperial decree to a consensus grounded in community understanding and local values. The redefinition of pearl beds from imperial monopoly to natural resources owned by local communities reflects broader themes in political ecology, where ecological spaces become arenas of negotiation between state authority and community memory. Local narratives such as “the return of pearls to Hepu” can be seen as forms of vernacular environmentalism that reassert ecological ethics against exploitative governance.

In summary, the governance of the pearl beds during the mid-Ming period underwent a complex trajectory—shifting from eunuch monopoly, to local reassertion of authority, and eventually rebounding into centralized control once again. At the same time, the localization of ecological knowledge transformed “governance” from a purely top-down exercise of power into a process increasingly infused with cultural memory, popular beliefs, and local claims to justice. This evolution enabled a redefinition and rebalancing of the boundaries of official authority.

5 Legal practice and governance dilemmas (a legal-historical perspective)

The above-mentioned compounding cycle of ecological collapse and social unrest exposed not only the limits of imperial governance but also the structural gaps in the Ming legal system. As the state failed to respond adaptively, legal enforcement broke down, further exacerbating resource conflict and weakening legitimacy.

Within the Ming dynasty’s institutional framework for managing the pearl beds, a significant disjunction existed between legal codification and practical enforcement. Although the state established strict punitive measures to curb illegal pearl harvesting, the implementation of these regulations at the local level was often ignored, distorted, or deliberately circumvented. Moreover, the ambiguous distribution of authority between the central and local governments, as well as between civil and military officials, further exacerbated administrative disorder. A close examination of key historical sources reveals that the failure of pearl fishery governance lay not solely in local greed, but more deeply in the legal system’s inability to restrain the abuse of power and structural corruption.

5.1 The disconnection between legislation and enforcement

The Ming legal system explicitly addressed the regulation of pearl resources. According to the official annotated version of the Ming legal code Annotated Statutes of the Great Ming, the illegal harvesting of pearls was equated with unauthorized mining and was punishable in the same category as the theft of government treasury goods. Offenders were to be subjected to heavy beatings, exile, and even facial tattooing as a warning to others—illustrating the state’s strong stance on the protection of natural resources (Wang and Wang, 1691).

However, the actual conditions in local society diverged dramatically from the orderly vision enshrined in law. As documented in the Records of Guangdong, pearl reserves in Hepu and surrounding areas steadily declined, while illicit poaching activities increased with impunity. This gave rise to mounting tensions between officials and commoners in frontier society, leading to local disorder so severe that military intervention was required to restore even superficial stability. The prevalence of these “numerous pearl thieves” reveals that despite the formal severity of the law, its enforcement was largely ineffectual (Guo, 2014c). The legal deterrent power of the state in matters of environmental resource protection had fundamentally eroded.

The inability of the legal system to restrain supreme power was also evident in political practice. In the 11th year of the Jiajing reign (1532), the official Guo Honghua, Vice Minister of the Court of Imperial Sacrifices, submitted a memorial urging a moratorium on the excessive logging and pearl harvesting occurring throughout the empire, arguing that these practices exacerbated tensions between the populace and state officials, leading many to join rebel factions and endangering social stability. The emperor, however, dismissed the proposal, asserting that pearl fisheries was a long-standing imperial institution, and reportedly responded with anger (Zhang, 1974b). This episode demonstrates the supremacy of imperial will over legal rationality and reveals the absence of an effective institutional mechanism for self-correction. The Ming legal system lacked an institutional mechanism for judicial review or the separation of powers. Statutes could be nullified or ignored at the discretion of the emperor, whose authority superseded even codified law. While officials could submit remonstrative memorials, these were often dismissed without consequence, underscoring the limits of legal constraint under autocratic rule. In the governance of natural resources, statutory law was incapable of constraining the absolutist tendencies of the throne.

5.2 The ambiguity between maritime defense and public order

On the institutional level, the Ming court attempted to militarize pearl governance in order to strengthen its control over the fishery zones. As recorded in the National Annals (Guo Que, an imperial chronicle documenting major events and court activities), during the Chenghua reign (1465-1487), the pearl supervisor Wei Zhu voluntarily petitioned to lead military forces between Hainan and Leizhou to suppress pearl thieves, even though the Ministry of War initially opposed granting military power to eunuchs. Ultimately, however, imperial sanction was given (Tan, 1958). Eunuchs derived their power not from formal legal offices but from direct imperial delegation. Their lack of official civil or military rank made their influence extra-legal—yet potent—effectively placing them outside the reach of standard bureaucratic oversight. This transition from civil to military oversight of coastal security illustrates the court’s growing dependence on armed intervention, yet also highlighted the coordination challenges between administrative and military jurisdictions.

This militarized model of governance persisted into the later Ming period. According to the Supplement to the Comprehensive Examination of Literature (encyclopedic institutional history compiled by scholars), during the Wanli reign (1573-1620), a roving general was stationed on Weizhou Island specifically to guard the pearl beds. Initially, this strategy yielded modest results, with poaching temporarily subdued. However, as soon as eunuchs resumed large-scale pearl operations along the coast—attracting both official and private vessels—the situation again deteriorated (Wang Q., 1602). The authorities were forced to implement flexible deployments, whereby generals moved in and out of stations according to the seasonal opening and closure of the fisheries. These stopgap measures reveal that while military force could contain illicit activity in the short term, it could not resolve the underlying institutional weaknesses.

An even more alarming issue lay in the collusion between local authorities and criminal actors at the level of law enforcement. According to Leisure Notes from the Forest Retreat by Wu Yuancui, the high-ranking official Chen Rui, in order to curry favor with powerful elites at court, clandestinely instructed bandits to invade state-controlled pearl beds. When the regional military commander Xue Mingyu was alerted and dispatched troops to suppress the incursion, Chen’s official army pretended to fight the bandits but actually allowed them to continue their activities. This case study shows that, although the Ming Code prescribed penalties for official corruption—including flogging, dismissal, or exile—such measures were rarely enforced in cases involving high-ranking officials acting under imperial patronage. Chen Rui’s impunity reflects how informal networks of influence and factional protection often nullified legal consequences, further weakening the credibility of the legal system in regulating elite behavior (Wu, a).

This behavior of ‘feigning battle while actually letting them go’ between government troops and bandits not only shows that the law has been completely undermined in the grassroots enforcement system, but also reveals the governance corruption brought about by the manipulation of local military forces by those in power at the top, with the national will represented by the law being completely undermined. Similar tensions between codified resource law and political prerogative can be found in early modern European maritime powers such as Spain and Portugal, where crown-appointed viceroys often bypassed colonial regulations for private gain.

6 Conclusion

The evolution of the pearl harvesting industry in the Ming dynasty was not merely a matter of marine economic development; rather, it was the product of a multi-dimensional interaction between imperial power, local governance, and ecological systems. As this paper has shown, pearls were far more than ornamental luxuries. They functioned as political commodities embedded within statecraft—used to signal imperial authority, reward loyalty, and assert sovereignty over maritime space. In this sense, pearls exemplify what environmental historian John McNeill calls the “resource politics” of early modern states: the ways in which power is exercised, extended, and contested through the control and allocation of scarce natural resources (McNeill, 1999).

The Ming state’s attempt to centralize the governance of the “pearl beds” offers a classic case of how environmental resources are politicized. Through state monopolization, eunuch oversight, and aggressive extraction policies, the regime sought not only economic benefit but symbolic dominance over nature. However, this monopolization incurred a double cost. On the one hand, it accelerated ecological collapse—destroying coral reefs, exhausting shellfish populations, and disrupting marine biodiversity. On the other, it produced social dislocation—resulting in high mortality among the Tanka laborers, mass flight, and episodic resistance. As McNeill has argued, ecological systems are not passive recipients of human intervention but active agents in shaping historical trajectories. The degradation of the pearl fishery in Ming China thus constitutes not merely an environmental crisis, but a historically contingent feedback loop that undermined the foundations of state legitimacy.

Indeed, the failure of Ming governance in the face of ecological thresholds reflects what McNeill terms “the fragility of imperial environmental strategies.” Imperial power, when exercised through h extractive overreach, confronts its limits in the face of resource depletion, disease propagation, and labor collapse. As seen in the Ming case, when pearls dwindled and laborers perished, the symbolic potency of the resource could no longer sustain the ideological weight imposed upon it. The court’s attempts to reassert control—through law, military force, or ritual purification—proved insufficient to counteract the ecological realities that eroded the very basis of its authority. Comparable dynamics were observed in early modern Europe, where coral fisheries in the Mediterranean and pearl fisheries in Spanish America also collapsed under imperial overreach, ecological exhaustion, and coerced labor regimes. These cases reinforce the broader historical lesson that centralized extractive economies, when disconnected from environmental realities, face inevitable breakdown.

This ecological counterforce also redefined the boundaries of political legitimacy. The resurgence of local narratives—such as the story of “Pearls Returning to Hepu”—signals a form of vernacular environmentalism, wherein local elites and communities used ecological memory and moral symbolism to contest the legitimacy of imperial resource extraction. In this sense, ecological degradation was not merely a background condition, but a terrain upon which political contestation was staged.

In sum, the Ming pearl economy reveals how imperial resource politics operated at the intersection of symbolism, sovereignty, and ecology. It also exposes the limits of centralized governance in the face of environmental feedback. By employing an environmental historical lens informed by scholars like John McNeill, we can better understand how the environment not only shaped the dynamics of Ming imperial rule but also exposed its vulnerabilities. This case thus provides a valuable historical analogue for contemporary discussions about sustainable governance, ecological justice, and the politics of resource extraction in fragile ecosystems.

At the same time, this study invites further legal-historical research into the institutional dimensions of environmental governance in imperial China. Future work might explore how Ming legal institutions attempted (or failed) to regulate resource use, particularly by analyzing underutilized materials such as administrative rulings, memorial archives, or judicial records beyond the statutory code.

Author contributions

CS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. YL: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was completed with the support of the major project of the National Social Science Fund of China, “Study on the Economic Strategy and Governance System of the South China Sea from the Ming and Qing Dynasties to the Republic of China” (Project No. 21&ZD226).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT, GPT-4) was used exclusively for language refinement and citation formatting. No interpretive content or historical claims were generated by AI tools.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Guo F. (2014b). Records of Guangdong Vol. 29 (Guangzhou: Guangdong People’s Publishing House), 876–877.

Guo F. (2014c). Records of Guangdong Vol. 29 (Guangzhou, China: Guangdong People’s Publishing House), 876–877.

Hall-Spencer J., Allain V., and Fosså J. H. (2002). Trawling damage to Northeast Atlantic ancient coral reefs. Proc. Biol. Sci. 269, 507–511. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1910

Huang Z. (1561) Guangdong Tongzhi Vol. 25 (Local S peciality VI), 17–20. Jiajing reign, year 40 ed. Ming Dynasty.

Huang R. (1974). Taxation and governmental finance in sixteenth-century Ming China (New York: Cambridge University Press), xiv.

McNeill J. R. (1999). Ecology, epidemics and empires: environmental change and the geopolitics of tropical America, 1600–1825. Environ. Hist. 5, 175–184. doi: 10.3197/096734099779568371

Shen S. and Zhao Y. (1587a) Revised Da Ming Huidian Vol. 60 (Ministry of Rites. Imperial Printing House), 1. Wanli reign, year 15.

Shen S. and Zhao Y. (1587b) Revised Da Ming Huidian Vol. 60 (Ministry of Rites. Imperial Printing House), 32. Wanli reign, year 15.

Shen S. and Zhao Y. (1587c) Revised Da Ming Huidian Vol. 60 (Ministry of Rites. Imperial Printing House), 37–38. Wanli reign, year 15.

Shen S. and Zhao Y. (1587d) Revised Da Ming Huidian Vol. 37 (Ministry of Revenue. Imperial Printing House), 26. Wanli reign, year 15.

Song Y. (2021). The Exploitation of the Works of Nature Vol. 18 (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company), 464.

Wang S. (1602) Yan Zhou Si Bu Gao Vol. 157 (Wang’s Shijing Hall), 8. Ming Dynasty Wanli reign, year 5.

Wang Q. (1602) The Supplement to the Comprehensive Examination of Literature Vol. 27 (Songjiang Prefecture, printer), 31–32. Wanli reign, year 30.

Wang Q. and Wang K. (1691) Annotated Explanation of the Supplementary Provisions of the Great Ming Code Vol. 18 (Criminal Law. Gu D, printer), 23. Kangxi reign, year 30. Qing Dynasty.

Wu Y. Lin Ju Man Lu Vol. 3 (First Collection. Yuan family, printer), 7–8. Wanli reign. Ming Dynasty.

Ye S. (1680a) Memorials of Ye Wenzhuang Gong Vol. 9 (Ye’s Book Tower, printer), 11–13. Chongzhen reign, year 4.

Ye S. (1680b) Diaries from Eastern Waters, Vol. 5. 7–9, Kangxi reign, year 19 rev. ed. Qing Dynasty.

Keywords: pearl harvesting, marine environmental governance, political ecology, resource politics, South China Sea, legal history

Citation: Shi C and Liu Y (2025) Pearls, power, and predation: an ecological perspective on marine resource governance in ancient China. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1653912. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1653912

Received: 25 June 2025; Accepted: 26 August 2025;

Published: 10 September 2025.

Edited by:

Yen-Chiang Chang, Dalian Maritime University, ChinaReviewed by:

Mehran Idris Khan, University of International Business and Economics, ChinaWei Yuan, Dalian Ocean University, China

Fei Ji, Hangzhou Urban and Rural Development Commission, China

Copyright © 2025 Shi and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ce Shi, Y3plc2MwMjBAZm94bWFpbC5jb20=; Yonglian Liu, dHlsbEBqbnUuZWR1LmNu

Ce Shi

Ce Shi Yonglian Liu1,2*

Yonglian Liu1,2*