- 1Law School, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China

- 2School of International Law, China University of Political Science and Law, Beijing, China

The adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and subsequent developments in State practice have prompted a growing number of International Investment Agreements (IIAs) to include "definition of territory clauses," extending their legal applicability beyond territorial waters. Yet the fragmented nature of the IIA regime has resulted in significant variations in the formulation and substantive scope of these provisions across different treaties. Concurrently, persistent divergences persist among States regarding the interpretation of sovereign rights and jurisdiction exercisable in various maritime zones—including the exclusive economic zone, the continental shelf, the high seas, and the international seabed area—which fundamentally shapes the applicability of IIAs to investments in non-territorial marine spaces. Determining such applicability carries broader implications for the interpretation and implementation of UNCLOS, particularly concerning marine environmental protection obligations and dispute settlement mechanisms. The complexity of this legal interplay underscores the need for rigorous scholarly analysis and coordinated policy responses. The international community should take proactive steps toward prescriptive and practical reforms to clarify the application of IIAs to investments in non-territorial waters. When properly defined and implemented, extending IIA protections to maritime investments could not only promote sustainable blue economic activities but also strengthen the international rule of law in ocean governance.

1 Introduction

Article 29 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties states, “Unless a different intention appears from the treaty or is otherwise established, a treaty is binding upon each party in respect of its entire territory.” International Investment Agreements (hereinafter referred to as “IIA” or “IIAs”), including Bilateral Investment Treaties (hereinafter referred to as “BIT” or “BITs”) and Treaties with Investment Provisions (hereinafter referred to as “TIPs”), which regulate international foreign investment relations between contracting States and aim to promote international investment and economic-technical cooperation development, are no exception to this general principle (Beham, 2020). Based on this provision, the geographic scope of IIAs over contracting parties should be limited to the land, air space, territorial waters, and subsoil, collectively known as the territory of contracting parties (Crawford and Brownlie, 2019).

However, as public international law has developed rapidly over the past half-century, States have acquired broader sovereign rights and jurisdiction beyond their territorial boundaries, particularly in the maritime domain. Investments in maritime areas like Exclusive Economic Zone (hereinafter referred to as “EEZ” or “EEZs”) and Continental Shelf (hereinafter referred to as “CS” or “CSs”) have also increased, driven by the practical requirements of economic development. Examples include the installation and operation of submarine cables and pipelines, the construction and operation of marine energy facilities, and the exploration and exploitation of international seabed mineral resources, etc. At the same time these investments hold significant value for host States, investors, and the international community, they face exceptionally high legal risks (Cotula and Berger, 2020).

Given their pivotal role in protecting international investment, the crucial question arises as to whether IIAs can be applied in waters where the host State lacks territorial sovereignty (hereinafter referred to as “non-territorial waters”) (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2024),1 which types of investments located in non-territorial waters may fall within the application ratione materiae of IIAs, and what potential impacts such application might have on the existing international legal framework. Addressing these issues will enable the international community to determine whether the current legal framework for international investment is capable of sufficiently supporting marine economic development.

To approach these issues, this paper employs three research methods: the doctrinal research approach, comparative legal analysis, and the case study approach. By thoroughly engaging with the recent academic developments and analyzing several influential maritime investment disputes in recent years, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the applicability of IIAs to international investments in non-territorial waters. In terms of structure, this article first examines the history, development, and current status of IIAs in their application to different non-territorial waters, laying the theoretical and practical foundation for addressing the two issues above. Next, the paper reveals that the application of IIAs on non-territorial waters depends not only on the provisions within the IIAs themselves but also on the prescriptive, enforcement and adjudicative jurisdictions that the host State can exercise based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as “UNCLOS”) and general international law (Liu and Duan, 2024). Only when specific investments fall within the jurisdictional scope of the host State—particularly within the scope of enforcement jurisdiction—can the host State effectively manage these investments and fulfil the investment protection obligations under IIAs (Benatar and Schatz, 2020). Protecting investments in non-territorial waters not only fosters the mutual development of the legal regimes of international investment law and the law of the sea, but also engenders a dynamic and complex interaction between these two fields. Such an approach is also likely to have significant implications for other provisions of the law of the sea, including those on marine environmental protection and existing dispute settlement mechanisms in UNCLOS. Finally, this paper provides a comprehensive analysis of whether IIAs are capable of protecting maritime investments located in non-territorial waters and offers specific recommendations to both host States and investors with regard to applying IIAs in non-territorial waters. Ultimately, this article aims to promote increased maritime investments located in non-territorial waters that can receive effective protection under IIAs.

2 The origin and development of the application of IIAs in non-territorial waters

The application of IIAs to investments in non-territorial waters did not come into existence naturally; rather, it underwent a delayed onset and a relatively prolonged development process (Wang, 2015). Before the 1980s, no IIAs attempted to expand their geographic scope to non-territorial waters, and there were only a few instances where IIAs provided differentiated stipulation of the term “territory” in their provisions. It can be argued that during this period, the geographic scope of IIAs in force was essentially delimited by the territorial boundaries of the contracting parties— the land domain, airspace, territorial waters (including internal waters and territorial seas), and subsoil. However, with the adoption of UNCLOS, whether IIAs can exert legal effects in non-territorial waters has become a particular concern. UNCLOS established the regime for the EEZ, developed the legal framework for the CS, and provided detailed regulations for areas beyond national jurisdiction (Gavouneli, 2007). With 170 contracting parties, it has become one of the most widely recognized conventions (United Nations, 2023). Consequently, the recognition of various sovereign rights and jurisdiction by States in non-territorial waters has gained widespread acceptance (HOUSE OF LORDS, 2022).

During the adoption of UNCLOS, a significant number of IIAs began to incorporate non-territorial waters into their geographic scope, as evidenced by the development of “definition of territory clauses” (hereinafter referred to as “territorial clauses”) within IIAs. Territorial clauses typically refer to provisions within the “definition clauses” of a BIT (usually the first article of a BIT or the first article of the investment part of a TIP) which are specifically intended to define “territory,” and thereby clarify the geographic scope of the treaty (Benatar and Schatz, 2020). In 1980, the United Kingdom—Bangladesh BIT became the first IIA to include non-territorial waters within its territorial clause formally. The clause stated that:

“The territory in which the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh is in force, as well as any area of sea or seabed outside the territorial sea of Bangladesh in which Bangladesh has sovereign rights in accordance with international law and the laws of Bangladesh.”2

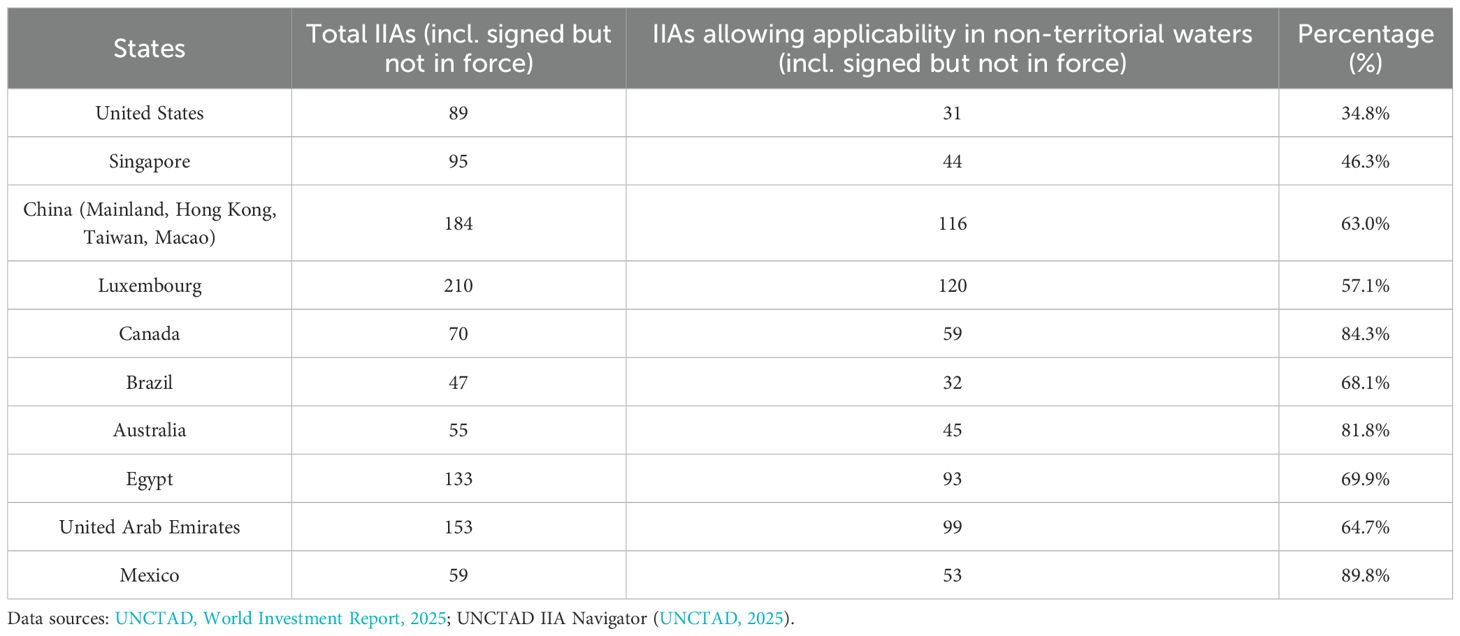

Subsequently, France, in its IIAs with States such as Equatorial Guinea, Panama, and China, also incorporated territorial clauses; these clauses were explicitly named “zones maritimes”, underscoring the intention for IIAs to be applicable to investments in the corresponding maritime areas.3 Today, in model BITs designed by the United States, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, as well as in newly signed treaties such as the USMCA and other TIPs, territorial clauses are established explicitly and encompass non-territorial waters like the EEZs and CSs of contracting parties.4 It appears that incorporating non-territorial waters into the geographic scope of IIAs has become a widespread choice at present (See Table 1).

According to its origin and development history, the application of IIAs in non-territorial waters evidently results from the interaction between IIAs and the law of the sea. Whether IIAs can incorporate non-territorial waters into their geographic scope and to what extent IIAs can be applied to investments in different non-territorial waters requires a comprehensive interpretation and judgment based on both the provisions of the IIAs themselves and other relevant legal rules and standards in the law of the sea. The territorial clause of an IIA can either affirm the application of IIAs in non-territorial waters, impose restrictions, or even indicate a denial of such application. However, after the territorial clause of an IIA confirms its extraterritorial application in non-territorial waters, the realization of its application in such maritime areas must also adhere to the rules and standards of the law of the sea and the domestic law of the host State. If the host State is unable to assert sovereign rights or jurisdiction over non-territorial waters in accordance with the law of the sea or its domestic law, or if an investment exceeds the host State’s jurisdiction in specific non-territorial waters, the IIA may not adequately protect specific investments in such waters.

3 Different types of territorial clauses in IIAs and their impact to the application of IIAs in non-territorial waters

Whether non-territorial waters can be incorporated into the geographic scope of an IIA depends primarily on their territorial clauses. Nevertheless, due to the inherent fragmentation of international investment law (Waibel, 2022), significant differences exist in the mode and language of territorial clauses, which can have varying impacts on the legal effects of IIAs in non-territorial waters.

3.1 Symmetric and asymmetric territorial clauses

Most IIAs that include territorial clauses can be largely categorized into two types based on the structure of these clauses: “symmetric territorial clauses” and “asymmetric territorial clauses.” These two types of territorial clauses exhibit significant differences in determining the legal effects of their IIAs in non-territorial waters.

For IIAs that use symmetric territorial clauses, the term “territory” is interpreted consistently across all contracting parties. If non-territorial waters are explicitly covered by a symmetric territorial clause, the IIAs can, in principle, apply to these non-territorial waters with the same standards applied to all contracting parties. Take the U.S.-Argentina BIT as an example. Although the U.S. is not a contracting party to UNCLOS, under the stipulation of the symmetric territorial clause of this BIT, UNCLOS will serve as the primary basis for determining which non-territorial waters may be included within the geographic scope of this BIT.

“‘Territory’ means the territory of the United States or the Argentine Republic, including the territorial sea established in accordance with international law as reflected in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. This Treaty also applies in the seas and seabed adjacent to the territorial sea in which the United States or the Argentine Republic has sovereign rights or jurisdiction in accordance with international law as reflected in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.5“

Conversely, if a territorial clause explicitly excludes non-territorial waters, as seen in the Denmark-Sri Lanka BIT where the clause defines territory as, it cannot be applied to investments in non-territorial waters:

“In respect of Denmark and Sri Lanka the territory which constitutes the Kingdom of Denmark and the Republic of Sri Lanka, respectively, including the sea and submarine areas.6 “

Because its language adopts an exhaustive expression without including any non-territorial waters, the scope of the BIT would not extend to any non-territorial waters of the two contracting parties.

Following further development of IIAs, more complex “asymmetric territorial clauses” are becoming more prevalent. Under these territorial clauses, the definition and interpretation of “territory” may vary for different contracting parties, leading to situations where the legal effectiveness of an IIA may extend to non-territorial waters of Contracting Party A but not to non-territorial waters of Contracting Party B. For instance, in the Russian Federation - United Kingdom BIT, the territorial clause makes a clear distinction between the two contracting parties:

“The term “territory” for the United Kingdom is limited to its territory in general international law, whereas for Russia, “territory” includes any maritime area where it can exercise sovereign rights for exploration and exploitation of the natural resources.7“

In this BIT, the geographic scope clearly differs between the two contracting parties. UK investors are protected under the BIT not only for investments within Russian territory but also in non-territorial waters where Russia exercises sovereign rights. In contrast, Russian investors are afforded protection only for investments made within the territory of the United Kingdom, excluding any non-territorial waters.

Of course, IIAs that use asymmetric territorial clauses do not always exhibit such clear distinctions as seen in the Russian Federation - United Kingdom BIT. However, subtle differences in the language of the territorial clauses can still result in variations in the geographic scope of BITs for different contracting parties. For instance, in the Mexico - United Arab Emirates BIT, the territorial clause is as follows:

“(a) with respect to the United Mexican States, the territory of the United Mexican States including maritime areas adjacent to the coast of fie State concerned, i.e. the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf, to the extent to which Mexico may exercise sovereign rights or jurisdiction in those areas according to international law;

(b) with respect to the United Arab Emirates when used in a geographical sense, the territory of the United Arab Emirates which is under its sovereignty as well as the area outside the territorial water, airspace and submarine areas over which the United Arab Emirates exercises sovereign and jurisdictional rights in respect of any activity carried on in its water, sea bed, subsoil, in connection with the exploration or for the exploitation of natural resources by virtue of its law and international Law.8 “

The territorial clause in this BIT makes it clear that for Mexico, the BIT applies to all waters where Mexico can exercise sovereignty, sovereign rights, or jurisdiction. In contrast, the application of the BIT to the United Arab Emirates’ non-territorial waters is subject to more specific limitations. When Mexican investors seek protection for their investments in certain waters under this BIT, they must carefully assess whether the United Arab Emirates can exercise sovereign rights or jurisdiction in those waters based on the exploration or exploitation of natural resources. If the United Arab Emirates’ jurisdiction over specific waters is unrelated to natural resources, investors may face challenges in obtaining protection from this BIT.

3.2 Explicit and implicit language of territorial clauses

Regarding the territorial clauses of IIAs, their language can be further categorized into explicit and implicit types (Abadikhah, 2022). For the former, IIAs explicitly list the specific maritime areas to which they can be applied using a positive list approach. An example includes the territorial clause in the 2021 Canadian model BIT, which states:

“For Canada: (i) the land territory, air space, internal waters, and territorial sea of Canada, (ii) the exclusive economic zone of Canada, and (iii) the continental shelf of Canada, as determined by its domestic law and consistent with international law.9“

Similar explicit territorial clause can also be discovered in USMCA and many recent IIAs. These clauses typically employ an exclusive list expression, indicating that, for contracting parties, apart from their territory, only the non-territorial waters explicitly stated in the territorial clauses (mainly EEZs and CSs) of an IIA can be included in its geographic scope. This approach often leaves little room for treaty interpretation in investment disputes. If a specific maritime area does not fall within this scope of the territorial clause, that IIA cannot normally be applied to investments in that maritime area. For example, the territorial clause in the China-Qatar BIT states:

“The term “territory” means the territory of each contracting Party, as well as the maritime area of each Contracting Party. The maritime area means the territorial seas and the continental shelf outwards the territorial seas over which each Contracting Party has, in accordance with the International Law sovereign rights and a jurisdiction with a view of prospecting, exploiting and preserving natural resources.”

In this BIT, “maritime areas” only refer to the territorial seas and CSs of the two contracting parties, excluding EEZs. Therefore, investments that can be considered solely within EEZs are excluded from its geographic scope.

In addition to the explicit territorial clauses of IIAs, there are also many IIAs with implicit expressions, particularly those concluded between the 1980s and the early 21st century. These IIAs often do not specify the particular maritime areas to which they can apply. Instead, they use general terms such as “maritime areas”, “maritime zones”, or even “zones” and “areas” to refer to areas beyond the territory of the contracting parties where IIAs may apply (Tseng, 2018). Indeed, the territorial clauses of these IIAs impose certain restrictions on the applicability to non-territorial waters, as seen in the China-Finland BIT:

“The term ‘territory’ means the territory of either Contracting Party, including the land area, internal waters and territorial sea and the airspace above them under the sovereignty of that Contracting Party, as well as any maritime area beyond the territorial sea of that Contracting Party, over which that Contracting Party exercises sovereign rights or jurisdiction in accordance with domestic and international law.”

In this BIT, the restrictive “maritime area” requirement is that “the Contracting Party can exercise sovereign rights or jurisdiction in accordance with domestic and international law.” This scope is similar to that of the contracting parties’ EEZs and CSs, but it should not be limited to such (Nguyen, 2021). On the one hand, coastal States may assert certain jurisdiction in other maritime areas in accordance with either their domestic laws or public international law. For example, China currently claims historic rights in the South China Sea, and the geographic scope of such rights may extend far beyond China’s EEZs and CSs (Gao and Jia, 2013). Further, the 2012 U.S. model BIT employs implicit language in its territorial clauses; due to the U.S. having signed shiprider agreements and other enforcement jurisdiction transfer agreements with several other coastal States worldwide (U.S. Department of State, 2023),10 at least those maritime areas where the U.S. can exercise specific enforcement jurisdiction can be interpreted within the geographic scope of its IIAs. On the other hand, as a result of the implicit language of territorial clauses failing to explicitly restrict certain types of jurisdiction, the term “jurisdiction” in such territorial clauses may include both territorial jurisdiction and extraterritorial jurisdiction based on different connecting factors (Liu and Duan, 2024). Thus, the interpretation of territorial clauses with implicit language may allow their IIAs to incorporate other non-territorial waters like the high seas and the “Area” into their geographic scope. This issue will be further discussed in the next section.

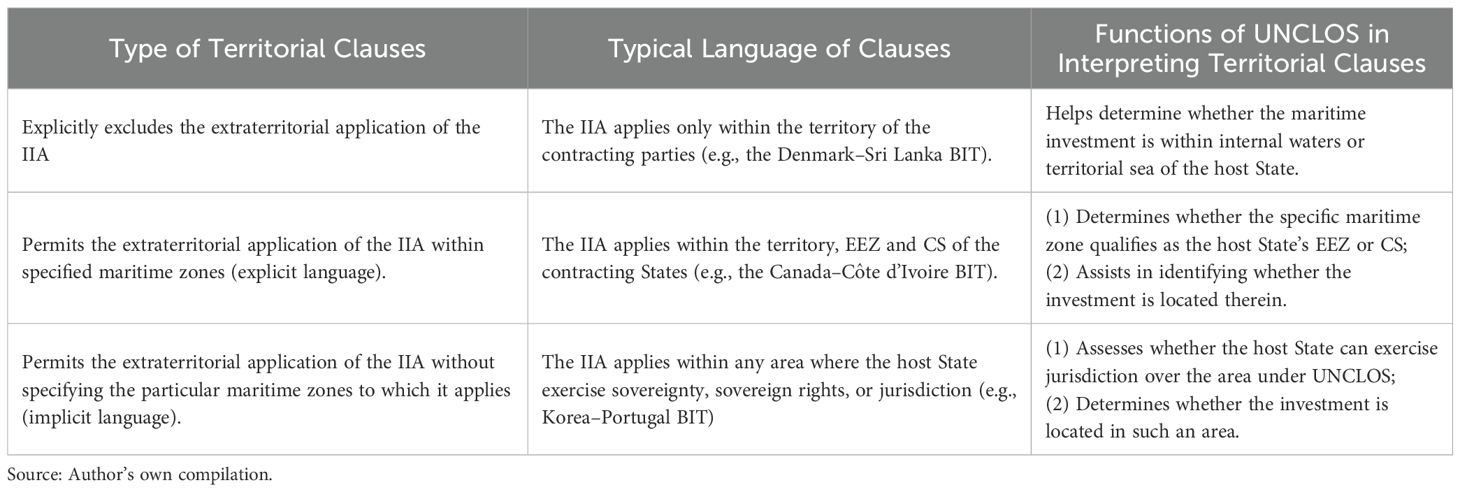

For the explicit and implicit territorial clauses of IIAs, their basic language and the role of UNCLOS in their interpretation are summarised and outlined in the table below (See Table 2).

3.3 The relationship between territorial clause and most-favored-nation treatment

In addition to territorial clauses in IIAs, the article still needs to examine whether Most-Favored-Nation treatment (hereinafter “MFN” or “MFN treatment”) in IIAs can also provide a legal basis for the application of IIAs in non-territorial waters.

According to the OECD, MFN clauses link investment agreements by ensuring that the parties to one treaty provide treatment no less favorable than the treatment they provide under other treaties in areas covered by such a clause (OECD, 2004). Since the MFN treatment can cover a significant portion of substantive rights and treatments that investors enjoy in most IIAs, it multinationalises the treatment that would otherwise pertain exclusively to bilateral or regional treaties at least to some extent (OECD, 2004). This feature of “multilateralising” specific provisions of IIAs is precisely why MFN treatment has long been a primary tool for investors to “free-ride” (Tzanakopoulos, 2014). The ambiguous concept of MFN treatment has led to, a huge number of investors to seeking MFN treatment not only for better substantive treatment, but also for definition clauses and dispute settlement mechanisms in order to gain added benefits from other IIAs (Rodriguez, 2008).

Nonetheless, by examining the provisions of existing IIAs, it is clear that MFN treatment cannot multilateralise the legal effects of territorial clauses. This is because territorial clauses, per se, are not a treatment. On the contrary, the definition of the term “territory” in territorial clauses is one of the conditions for determining whether the MFN clause is applicable. In model BITs from States such as the United States, Germany, Canada, etc., it is explicitly stipulated that the prerequisite for the application of MFN treatment states that the “investment is located within its territory”.11 Therefore, only an investment that meets the requirements of the territorial clause is eligible for the further application of the MFN clause. Similar considerations also apply to the determination criteria for the legal effects of the MFN clause based on the term “investment.” In the Société Générale S.A. v. The Dominican Republic Case, the arbitral tribunal noted that:

“Each treaty defines what it considers a protected investment and who is entitled to that protection, and definitions can change from treaty to treaty. In this situation, resort to the specific text of the MFN Clause is unnecessary because it applies only to the treatment accorded to such defined investment, but not to the definition of “ investment” itself.12“

Additionally, recent IIAs tend to impose more restrictions on the application of MFN treatment meaning that the possibility of expanding the scope of application of MFN treatment in the future is almost non-existent. For example, in the Bahrain - Japan BIT, MFN treatment does not apply to certain treatments obtained by contracting parties through regional agreements or to dispute resolution mechanism.13 Similar provisions have also appeared in many recent TIPs, such as the Canada - EU CETA.14 Accordingly, it should not be assumed that MFN treatment would result in the multilateralization of the territorial clause of an IIA nor extend the geographic scope of an IIA.

4 Analysis of the legal effects of IIAs in non-territorial waters

Whether IIAs can achieve application in non-territorial waters is not only dependent on the stipulation of territorial clauses, but equally depends on the jurisdiction of host States in relative waters, particularly their enforcement jurisdiction (Zheng, 2016). In the cases of SGS v. Philippines and Ambiente Ufficio S.p.A. v. Argentina, the arbitral tribunals emphasized the decisive role of the host State’s jurisdiction in determining whether an investment meets the territorial nexus requirement.15 In the Carlyle Group and Others v. Morocco case, the respondent also highlighted that the enforcement jurisdiction of the host State can be a core element in determining whether the investment can establish a territorial nexus with the host State.16 If a given investment falls outside the scope of a host State’s sovereign rights or jurisdiction—belonging instead to the realm of freedom rights, the exclusive jurisdiction of other States, or a disputed maritime area where the host State’s entitlement to sovereign rights and jurisdiction remains uncertain—the question arises as to whether such an investment can satisfy the ratione materiae requirement for the application of IIAs (Harrison, 2020). Furthermore, the exercise of sovereign rights and jurisdiction by a host State under UNCLOS may conflict with its obligations to protect foreign investments under IIAs. The intersection between ocean governance and investment protection thus creates complex legal interfaces that require careful balancing of competing international law obligations.

4.1 Application of IIAs in EEZs and CSs

Investments in the EEZs and CSs of a host State may face serious risks and legal conflicts (Nemeth et al., 2014). These two maritime areas are also the major non-territorial waters where most IIAs are expected to achieve legal effects and protect relative maritime investments.

Although the EEZ and CS are distinct legal regimes, with rare exceptions, there can be an overlap within 200 nautical miles from the baseline of a coastal State. With regard to the EEZ, coastal States possess a range of sovereign rights related to exploring and exploiting natural resources. Coastal States can also exercise some jurisdictions in the EEZ.17 Such sovereign rights and jurisdiction not only include prescriptive jurisdiction, but also enforcement jurisdiction and adjudicative jurisdiction (Kaye, 2015). In parallel, the legal regime of the high seas can be applied in these two maritime areas, as long as it does not conflict with the legal requirements established by UNCLOS for EEZs and CSs.18 These sovereign rights and jurisdiction in the EEZ and CS of the host State stipulated by UNCLOS serve as one of the primary source for the territorial nexus issue of IIAs in both maritime areas, as the host State can exercise enforcement jurisdiction and directly control to such investments.

4.1.1 General criteria for determining jurisdiction over investments in EEZs and CSs

Maritime investments in EEZs and CSs can be classified into several categories: (1) the exploration and exploitation of living and non-living natural resources; (2) the construction of artificial islands or related installations; (3) the laying of submarine cables and pipelines; (4) the development of non-natural resources such as underwater cultural heritage and shipwrecks; and (5) various investments related to vessels (Liu and Duan, 2025). The determination of whether a host State may exercise jurisdiction over specific investment categories must be assessed in compliance with UNCLOS provisions and other applicable international rules and standards.

When a host state asserts a specific maritime area as part of its EEZ or CS, UNCLOS explicitly confirms that the following investments fall squarely within its jurisdictional authority: the exploration and exploitation of natural resources; and the construction and operation of artificial islands, installations, and structures. In contrast, investments involving underwater cultural heritage do not fall under this jurisdictional scope and are instead considered part of “residual rights.” (Sun, 2025) Neither UNCLOS nor the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage clearly allocates ownership rights over underwater cultural heritage. While the jurisdictional aspects of underwater cultural heritage receive limited treatment in both instruments, the International Court of Justice in Alleged Violations of Sovereign Rights and Maritime Spaces in the Caribbean Sea emphasized that a coastal State’s regulation of underwater cultural heritage within its contiguous zone has attained the status of customary international law. However, such jurisdiction is confined to the protection of underwater cultural heritage; it does not extend to its commercial exploitation or to questions of ownership and the allocation of economic benefits derived therefrom. Accordingly, if an investor’s activities involving underwater cultural heritage fall outside the host State’s jurisdiction, then the unresolved preliminary question of whether the host State possesses jurisdiction will hinder such investments from securing protection under the IIA. The issue of jurisdiction has already sparked disputes among States with differing interests in the earlier underwater cultural heritage investment arbitration case—Sea Search-Armada, LLC v. Republic of Colombia.19 In the more recent case of Maritime Archaeology Consultants Switserland AG v. Republic of Colombia,20 questions concerning the ownership and jurisdiction over underwater cultural heritage are likely to be subject to further discussion.

Moreover, investments involving submarine cables, pipelines, and vessels may encounter heightened difficulties in establishing a territorial nexus. Under UNCLOS, the laying of submarine cables and pipelines, as well as the navigation of vessels, are recognized as falling within the scope of the rights of freedom of all States.21 In other words, even if the host State claims a specific maritime area as part of its EEZ or CS, it must identify an extraterritorial connecting factor—most notably one based on nationality jurisdiction and the flag State jurisdiction—if it wishes to exercise jurisdiction over these two types of investments (Chang et al., 2024).

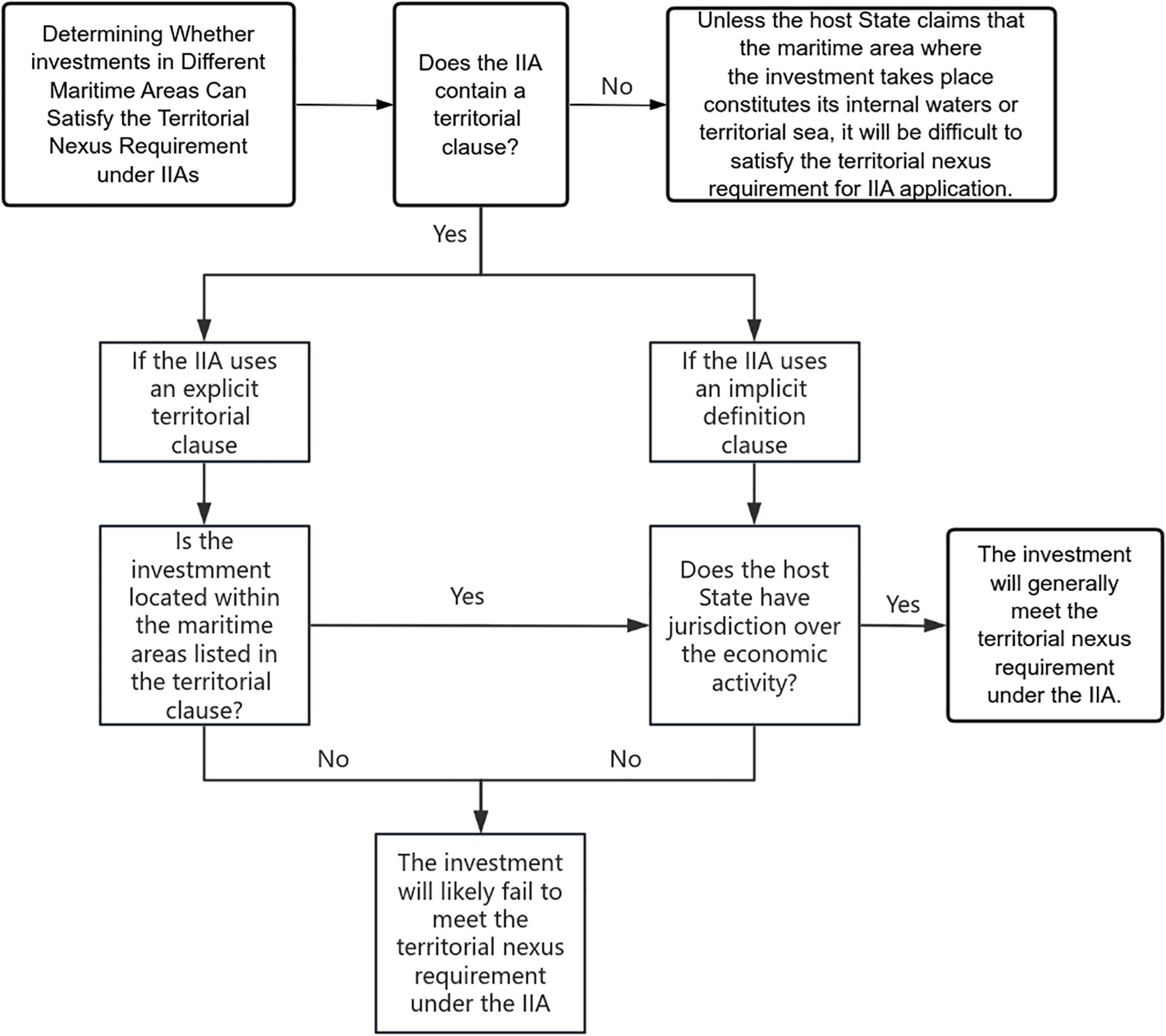

Other potential connecting factors for establishing a territorial nexus in such investments find only limited support in UNCLOS and relevant international rules and standards. In its 2020 interim report on submarine cables and pipelines, the International Law Association rejected the view that coastal States may exercises extraterritorial jurisdiction over submarine cables and pipelines beyond the scope provided in UNCLOS Article 79 (International Law Association, 2020). As for investments related to vessels, in the M/V “Norstar” case, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as “ITLOS”) expressly held that a State may not exercise prescriptive jurisdiction over foreign vessels on the high seas.22 This conclusion was subsequently invoked and endorsed by the tribunal in the Enrica Lexie case.23 Although the EEZ and CS regimes do not simply replicate the high seas regime, and coastal States are permitted to impose certain restrictions on the navigation rights of foreign vessels and other navigation-related activities when exercising their maritime entitlements (Chang et al., 2024), Where vessel-based investments do not fall strictly within the scope of those rights—such as offshore bunkering or maritime rescue—these activities likewise fall within the category of residual rights or even the rights of freedom of all States, rather than forming part of the coastal State’s jurisdiction. As a result, the host State faces significant difficulties in exercising extraterritorial jurisdiction over submarine cables, pipelines, and vessels on other connecting factors. Where no valid jurisdictional basis can be established, many investments involving submarine cables, pipelines, and vessels will struggle to form the territorial nexus required for IIA application ratione materiae (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart for determining territorial nexus of investments in maritime zones under IIAs. Source: author’s own compilation.

4.1.2 Assessment of host state jurisdiction regarding investments in disputed waters

Beyond the basic determination of whether investments in the EEZs and CSs fall within the host State’s jurisdiction, a further issue warrants attention—since the global progress in maritime boundary delimitation has been exceedingly slow, more than half of the world’s maritime boundaries remain unsettled among coastal States, resulting in a substantial number of disputed waters (Østhagen, 2020). Against this backdrop of an increasing number of disputed waters, the question arises: can maritime investments in disputed waters still satisfy the conditions for the application of IIAs?

From the prescriptive viewpoint, IIAs do not automatically preclude their application to relevant investments merely because the maritime area in question is disputed. This is because IIAs do not treat “territory” as a fixed concept (Selim, 2025). In ISDS practice, both the geographical scope of the host State and the maritime areas under its jurisdiction may change over time, and the legality of the host State’s title to such territory or maritime areas generally falls outside the scope of an arbitral tribunal’s determination.24 Accordingly, where a disputed water involves the host State asserting sovereignty or maritime entitlements and other States merely object without advancing competing claims to sovereignty or maritime entitlements over the same area; or where the dispute bears no substantive connection to the maritime entitlements on which the investment depends—for example, where both the host State and another coastal State claim a given area as part of their EEZs, yet the investor’s activity concerns the laying of submarine cables, which, under UNCLOS Article 58, falls within the rights of freedom of all States—the disputed status of the area does not impede the application of IIAs. In such circumstances, it is sufficient to apply the “effective control” principle to determine whether the host State exercises effective control over the maritime area itself or over the specific maritime entitlements at issue (Harrison, 2020).

However, in another scenario—where both the host State and another State claim maritime entitlements over a given area, and those rights form the very basis for establishing the territorial nexus of the investment; or where the investor’s loss is caused by actions of another State making an adverse claim to the host State—IIA application faces a different situation. In such cases, the question of sovereignty or entitlements over the disputed water becomes a preliminary issue and a very subject matter for determining IIA application ratione materiae. Yet, neither IIAs themselves nor ISDS arbitral tribunals generally have jurisdiction to resolve such public international law disputes. If the investment dispute nonetheless proceeds under ISDS, the tribunal should invoke the Monetary Gold principle to decline jurisdiction (Nguyen, 2021). This reasoning finds support in a recent significant investment dispute concerning a disputed water—Peteris Pildegovics & SIA North Star v. Kingdom of Norway. In this case, the claimants believe their investment in snow crab fishing within Norway’s CS has been treated unfairly by Norwegian authorities. However, it is critical to recognize that sovereign rights over snow crabs in this maritime area were subject to competing claims between the Norway and a third State, Russia. While Russia’s jurisdictional claims over the disputed waters would not per se negate Norway’s asserted rights, the investors’ alleged losses were partially attributable to enforcement conducts taken by Russian authorities. This circumstance would necessarily require the tribunal to assess the legality of Russia’s conduct as a prerequisite to adjudicating the investors’ claims. Norway invoked the Monetary Gold principle, contending that the tribunal should decline jurisdiction over the investment dispute absent Russia’s consent. The tribunal ultimately sustained Norway’s jurisdictional objection, while clarifying that the principle would not preclude its jurisdiction over investment claims unaffected by Russian conducts.25 If this interpretation and implementation of the Monetary Gold principle is correct, it would follow that all investment disputes dependent on a prior determination of maritime entitlements—where such determination is essential to establishing a territorial nexus—must be strictly governed by the principle. In practice, this would require tribunals, first, to make a threshold determination as to whether resolving the dispute would inherently involve adjudicating a third State’s sovereign rights or lawful conduct; and second, to exercise jurisdiction only where either (a) the third State has given express consent, or (b) the claims can be resolved without any assessment of that third State’s rights or conduct.

Admittedly, whether and how a third State may express its consent within ISDS proceedings remains a matter of considerable controversy.26 Under prevailing ISDS practice, third States may participate as amicus curiae, and in certain cases—such as JSC CB Privat Bank and Finance Company Finilon v. Russian Federation, the submissions of a third State acting as amicus curiae have even served as a key reference for arbitral tribunals in establishing a territorial nexus (Fouchard Papaefstratiou, 2023). However, it remains contentious whether such a procedure can amount to an expression of State consent for the purposes of the Monetary Gold principle (Galindo and Elsisi, 2021). Notably, some IIAs, such as the China–Malaysia BIT, the China–Philippines BIT, and the China–Vietnam BIT,27 expressly empower tribunals to design their own procedural rules. This flexibility could potentially facilitate a procedural mechanism through which a third State may express consent regarding the application of the Monetary Gold principle, thereby enabling tribunals to more effectively determine whether disputes over investments in contested maritime areas fall within their jurisdiction.

4.2 Application of IIAs in the high seas and the international seabed area

The question of whether the scope of IIAs can extend to the high seas and the international seabed area (hereinafter referred to as the “Area”) is worth examining. The high seas and the “Area” are also referred to as “areas beyond national jurisdiction”, where no State can claim sovereignty or sovereign rights (Berry, 2021). Thus, for most IIAs that use explicit language in their territorial clauses, despite confirmation of their legal effects in non-territorial waters, the exclusive list of territorial clauses never includes the high seas or the “Area.”28 Nevertheless, for IIAs using implicit language in their territorial clauses, due to the lack of clarity in their language and the increasing exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction by States in the high seas and the “Area,” IIAs now bear the potential for application in these two maritime areas.

Firstly, territorial clauses with implicit language do not enumerate which non-territorial waters can be applied; instead, they merely use some ambiguous terms like “maritime areas”, “maritime areas”, or even simply “zones” instead. Examples include the Saudi Arabia-Sweden BIT, Myanmar-Singapore BIT, China-Finland BIT,29 and Korea, Republic of - Portugal BIT. According to the interpretative rule of treaties, namely, Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, both the high seas and “Area” can indeed be considered as “maritime areas”, “maritime areas”, or “zones” (HOUSE OF LORDS, 2022), and the jurisdiction that contracting States can exercise should not be limited to territorial jurisdiction only (Crawford and Brownlie, 2019). In fact, States can exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction over different subjects, objects, and maritime activities in the high seas and the “Area” through different connecting factors, and extraterritorial jurisdiction should also be considered as “jurisdiction” in territorial clauses with implicit language (Yang, 2021). As States can exercise certain extraterritorial jurisdiction over the high seas and the “Area,” there is a clear foundation for the high seas and “Area” to become part of the geographic scope under IIAs (Wang et al., 2024).

In accordance with general international law and UNCLOS, a State, no matter whether it is a coastal or landlocked, can exercise jurisdiction over vessels flying its flag and individuals with its nationality on the high seas through flag State jurisdiction and nationality jurisdiction (Walker, 2012). Additionally, a State can, for the purpose of protecting its national interests and the common interests of mankind, exercise jurisdiction over various subjects, objects, and activities on the high seas and “Area” through either the protective jurisdiction, universal jurisdiction, or direct authorization by treaties (Crawford and Brownlie, 2019). Extraterritorial jurisdictions over the high seas and “Area” may also lack exclusivity, as various States may exercise jurisdiction over the same subject, object, or activities based on similar or different connecting factors, consistent with the inference that no State can assert sovereignty over the high seas and “Area” (Gavouneli, 2007; Wang et al., 2024). These connecting factors and related extraterritorial jurisdictions are the primary basis for establishing a nexus between the host States and the investors and their investments.

Another challenge that IIAs may face during their application in the high seas and “Area” is that, despite States being able to exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction over specific subjects, objects, and activities in these maritime areas through different means, all such extraterritorial jurisdictions are not inherently stable (HOUSE OF LORDS, 2022). In other words, if there are no connecting factors exist, such as when there is no vessel flying the flag of State A in the high seas, and no other facts or legal bases exist to establish jurisdiction for State A, then at least at that point in time, State A has no extraterritorial jurisdiction in the high seas and “Area”. Therefore, when interpreting the territorial clause of IIAs and considering its application in the high seas or the “Area”, it must be realized that the extraterritorial jurisdiction of a host State over the high seas and “Area” is not fixed but constantly changing. This fundamentally differs from the jurisdiction that States have in EEZs, CSs and in their territory. If we use a static perspective to interpret such territorial clauses, then excluding the high seas and the “Area” from the geographic scope of IIAs seems reasonable, because no State can demonstrate that they have consistent extraterritorial jurisdiction over the two maritime areas. However, if a dynamic perspective is used to interpret territorial clauses, then so long as a host State has jurisdiction over investments in the high seas or “Area” at the point in time when the IIA must be applied, it implies that the high seas or “Area” can be included in the territorial clause, and investments would naturally have a basis to receive IIAs protections. In practice, there are instances in the maritime domain where a dynamic interpretation of treaty provisions is reflected, such as in the determination of “international navigation” in international straits, where States like Japan emphasize assessing the “actual status”(使用実態) of straits usage (The House of Representatives, Japan, 2016). In the JSC CB Privat Bank and Finilon v. Russia case that was mentioned above,30 the arbitral tribunal appears to be more supportive of the dynamic interpretation of IIAs territorial clauses (Rachkov and Rachkova, 2020). Unfortunately, current international rules and standards of interpretation of international treaties, such as the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, or past precedents related to maritime investment, do not provide definitive guidance on whether to adopt a static or dynamic interpretation of IIAs provisions.

If the dynamic interpretation of the territorial clauses of IIAs is acceptable, the application of IIAs to the high seas and the “Area” must be based on host States having jurisdiction over specific investments in these two maritime areas. Several typical investments located in the high seas or “Area” could meet this requirement, including the construction of artificial islands and facilities, vessels, submarine cables and pipelines, along with the exploration and exploitation of natural resources in the “Area” under sponsoring States’ participation. Most of these activities do not differ significantly from jurisdictional determinations in the EEZ and CS. However, the exploration and exploitation of natural resources in the “Area” constitutes a unique regime to UNCLOS, and the scope of host State jurisdiction therein, as well as the applicability of IIAs, requires further examination.

Similar to the natural resources in the EEZs and CSs, the natural resources in the high seas or the “Area” are also maritime investments that attract significant attention from the international community. Such activities essentially include the exploitation of fisheries in the high seas and the exploration and exploitation of mineral resources in the “Area.” For the former, as no State can claim sovereignty or sovereign rights over the high seas,31 the exploitation of fisheries resources in the high seas itself cannot fall under the jurisdiction of any host State, rather it is a traditional freedom of every State (Hasanli, 2021). Therefore, in most situations, disputes regarding the ownership and profits of fisheries resources do not meet the conditions for the application of IIAs. It is important, however, to note that investors can seek alternative methods to address disputes arising from their investments in fisheries resources; for example, if the host State violates investment commitments by prohibiting investors from bringing fisheries resources caught in the high seas into its domestic market, investors may seek remedies using alternative objects such as “market share.” This approach was supported in S.D. Myers v. Canada, where the tribunal accepted market share as a qualified investment.32 Moreover, if the host State causes damage to fishing vessels, investors can seek remedies for the damage to tangible assets, such as the vessels themselves.

Regarding the latter, although mineral resources in the “Area” are considered the “common heritage of mankind”, UNCLOS has established a relatively comprehensive legal regime for the exploration and exploitation of these resources. This legal regime can clearly be applied to foreign investors in a host State. According to Part XI of UNCLOS, the only way for foreign investors to participate in resource exploration and exploitation in the “Area” is to establish a company with the nationality of the host State and receive sponsorship from the host State. In addition, the International Seabed Authority (hereinafter the “ISA”) has complete and comprehensive jurisdiction over a specific activity in the “Area”. The ISA can take measures in accordance with UNCLOS to ensure the entire process of seabed mining exploration and exploitation in the “Area” is in compliance with the provisions stipulated by UNCLOS.33 Consequently, the exploration and exploitation of natural resources in the “Area” not only includes the jural relations between investors and host States, but also includes an additional role, the ISA. Disputes may involve not only investors and their host States, but also the ISA (Pecoraro, 2019). In relation to the latter, if a dispute does not involve the violation of the provisions of IIAs by the host State, it falls outside the scope of the legal effects of IIAs. However, such situations can be addressed in part through the dispute resolution mechanism for “Area” activities under article 187 of UNCLOS (Dingwall, 2018).

As for disputes arising solely between investors and the host State concerning the exploration and exploitation of “Area” resources, investors may seek remedies from IIAs. Firstly, the exploration and exploitation of resources in the “Area” aligns well with the investment clauses of the majority IIAs and objective standards such as the “Salini Test”, making it less controversial to be considered as a qualified investment (Dingwall, 2018). Secondly, with regard to the jurisdiction of the host State, UNCLOS explicitly states that each State has a responsibility, through its domestic law, to ensure that the sponsored entity’s activities comply with the obligations under UNCLOS (Freestone, 2011).34 This implies that the Convention grants States prescriptive jurisdiction and enforcement jurisdiction over activities related to activities of the “Area”, and therefore, the host State is also required to provide substantive treatment from IIAs to foreign investors. Although the provisions of UNCLOS may grant host States some room to exercise the right to regulate, host States cannot exercise their right to regulate without limit. In Eco Oro v. Colombia, the arbitral tribunal held that “neither environmental protection nor investment protection is subservient to the other, they must co-exist in a mutually beneficial manner”.35 Accordingly, if the prerequisites for the application of IIAs are met, the host State should strike a balance between the right to regulate and the interests of investors. This balance will also help to promote activities in the “Area” (Pecoraro, 2019).

Moreover, since the exploration and exploitation activities must be established with sponsorship, any time a host State revokes the permit for such sponsor, it will result in investors being unable to continue the exploration and exploitation of resources in “Area” (Kong, 2017). A host State thus has jurisdiction over the investor’s activities in the “Area”, and its jurisdiction is also supported by the Advisory Opinion issued by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea on the “Responsibilities and obligations of States sponsoring persons and entities with respect to activities in the Area” in 2011, where the Seabed Disputes Chamber stated that:

“The sponsoring State’s obligation “to ensure” is not an obligation to achieve, in each and every case, the result that the sponsored contractor complies with the aforementioned obligations. Rather, it is an obligation to deploy adequate means, to exercise best possible efforts, to do the utmost, to obtain this result. To utilize the terminology current in international law, this obligation may be characterized as an obligation “of conduct” and not “of result”, and as an obligation of “due diligence”.36

“Sponsoring State (host State) shall taking all measures necessary to ensure” compliance by the sponsored contractor. Annex III, article 4, paragraph 4, of the Convention makes it clear that sponsoring States’ “responsibility to ensure” applies “within their legal systems”. With these indications the Convention provides some elements concerning the content of the “due diligence” obligation to ensure. Necessary measures are required and these must be adopted within the legal system of the sponsoring State.37

UNCLOS itself, as well as the advisory opinion, both reflect the scope of the jurisdiction that the sponsoring State holds in the corresponding activities. If a dispute arises between the investor and the host State due to “Area” activities and falls within the jurisdiction of the host State, certain IIAs meeting the requirements can serve as the last straw for the investor to protect their rights where there is an absence of remedies provided for the investor by UNCLOS. Moreover, if future investment disputes concerning the “Area” are brought before an ISDS arbitral tribunal, the ISA could also be expected to participate as amicus curiae, thereby offering an authoritative reference to assist the tribunal in clarifying issues relating to the host State’s jurisdiction.

4.3 Potential risks in applying IIAs to protect investments in non-territorial waters

While the UNCLOS framework provides essential guidance for applying IIAs to maritime investments in non-territorial waters, its influence extends far beyond jurisdictional clarification. In some instances, some provisions of UNCLOS may even come into conflict with the application of IIAs. Specifically, prescriptive conflicts and differing value orientations between certain provisions of UNCLOS and those of IIAs may undermine key ocean governance objectives established under UNCLOS. Moreover, potential jurisdictional overlaps between UNCLOS dispute settlement mechanisms and the ISDS system could create substantial uncertainty in the resolution of maritime investment disputes.

4.3.1 Conflicts between the value orientation of UNCLOS and IIAs

A key practical risk in applying UNCLOS to maritime investment lies in the considerable divergence that persists between the value orientations of UNCLOS and IIAs. This divergence implies that certain UNCLOS provisions may come into direct conflict with substantive treatments under IIAs when extended to maritime investments.

Overall, UNCLOS is a framework legal instrument characterized by a pluralistic value orientation. While it primarily centers on the rights and interests of coastal States, it also gives due consideration to the rights and interests of flag States, port States, geographically disadvantaged States, and even the broader interests of all humankind.38 This pluralism is embedded throughout nearly all major parts of UNCLOS, particularly in Parts XI and XII. For instance, Article 145 requires States to take necessary measures to prevent harm to the common heritage of mankind when conducting activities in the Area; Article 192 establishes the general obligation of all States to protect and preserve the marine environment. As a result, regardless of the nature of maritime activities, States are required to respect not only the rights of other State Parties to UNCLOS but also the collective interests of humanity. These various values are not arranged in a hierarchical order of precedence; rather, they are intended to be upheld concurrently in the conduct of maritime activities (Zhang, 2014).

By contrast, the value orientation of IIAs has long been comparatively narrow. Early IIAs focused almost exclusively on protecting the rights and interests of investors. In recent years, however, there has been a growing trend toward incorporating broader values such as sustainable development, human rights, and corporate social responsibility—some of which have even evolved into binding obligations applicable to both investors and host States (Baltag et al., 2023). Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that traditional IIAs still form the core of the current international investment law regime. The legal force of most traditional IIAs has not been repealed or superseded by newer treaties (UNCTAD, 2018). Furthermore, the integration and enforcement of these non-investment protection values remain subject to ongoing debate. Even scholars who support a broader normative foundation for international investment law generally concede that the protection of investment continues to be the principal objective of IIAs (Titi, 2022).

This fundamental divergence in value orientation between UNCLOS and IIAs means that many obligations under UNCLOS—particularly those requiring States to consider and respect the interests of other States or even humankind as a whole—may come into direct conflict with the investor protection standards established under IIAs. When a host State is simultaneously bound by obligations under both UNCLOS and an IIA, it may find itself caught in a legal dilemma. The protection of investments in the “Area” directly illustrates the challenges posed by these diverging normative frameworks. Since the “Area” constitutes the common heritage of humankind, States are collectively obliged to manage, share, and co-own its resources.39 However, as noted above, the technical capacity to explore and exploit the resources of the “Area” is concentrated in the hands of a small number of technological giants, while most States lack the requisite technology and funding to undertake such activities independently (European Parliamentary Research Service, 2015). Consequently, providing guarantees to private investors and relying on their participation in activities in the Area has become the only feasible path for many States—an approach that UNCLOS itself acknowledges and accommodates (Robb et al., 2024).

Nonetheless, as previously discussed, UNCLOS imposes a range of legal obligations—particularly those focused on environmental protection—for activities conducted in the Area. In the 2011 Advisory Opinion on the Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with Respect to Activities in the Area, in addition to affirming the jurisdiction of sponsoring States, the Seabed Disputes Chamber of ITLOS also confirmed that sponsoring States must adopt a series of environmental protection measures. These include taking necessary steps to prevent, reduce, and control transboundary marine pollution, applying the precautionary principle to minimize environmental harm, and ensuring that activities in the Area are conducted in accordance with best environmental practices.40 While such measures are essential for safeguarding the marine environment, they may nonetheless directly or indirectly undermine the commercial viability of private investments in the Area. Similar conflicts may also arise in relation to investments in other non-territorial waters, as States are subject to both general and specific obligations to protect and preserve the marine environment under Part XII of UNCLOS (Chang et al., 2025). To avoid breaching these environmental obligations, host States may need to adopt a range of regulatory measures targeting marine investments in non-territorial waters. As a result, such measures could prompt claims that the host State has breached substantive obligations under IIAs, such as the fair and equitable treatment or the treatment against unlawful expropriation.

Recent arbitral cases have already underscored the dilemma host States face when navigating the conflicting value orientations of public international law and international investment law. In Odyssey Marine Exploration v. Mexico, Mexico’s revocation of a seabed mining license based on environmental protection concerns was found by the tribunal to constitute a violation of the FET standard.41 Similarly, in Santa Elena v. Costa Rica, the tribunal held that even when a host State adopts measures to fulfill its obligations under international law, it must still provide compensation if those measures amount to expropriation.42 So under the principle of pacta sunt servanda, compliance with one set of treaty obligations may nevertheless result in a breach of another. Yet, both the prevailing IIA regime and UNCLOS lack targeted mechanisms for reconciling such conflicts (Andreotti, 2024).

4.3.2 Jurisdictional overlap between the dispute settlement mechanism under UNCLOS and IIAs

The application of UNCLOS to various maritime investments means that legal disputes in this area not only involve determinations of “investor–state” legal relationships, but also exhibit a strong public international law dimension. Consequently, in specific maritime investment disputes, investors may not only pursue remedies through the ISDS mechanism, but—where flaws exist in the host State’s exercise of jurisdiction over maritime investments—they may also seek remedy under public international law dispute settlement mechanisms, with the support of their home State. In this context, the dedicated dispute settlement mechanism under UNCLOS offers an alternative avenue for investor remedy [Liu and Duan]. However, when both ISDS and UNCLOS-based mechanisms possess jurisdiction over a maritime investment dispute, the host State may face intensified judicial pressure. In addition, such jurisdictional overlap may result in conflicting legal conclusions and ultimately undermine the effectiveness of both dispute settlement mechanisms.

Both the ISDS and UNCLOS dispute settlement mechanisms are mandatory in nature. Of course, the latter can only be initiated by the investor’s home State, whereas the former primarily depends on the investor’s initiative. In different types of maritime investment cases, the most critical factor in determining whether the ISDS or UNCLOS mechanism will be utilized is whether the dispute concerns the interpretation or implementation of UNCLOS, and whether resolving that UNCLOS-related issue is a prerequisite to settling the investment dispute itself.43 In cases where the host State’s jurisdiction over the investment is uncertain, it is generally more appropriate to first resort to the UNCLOS dispute settlement mechanism. Indeed, it is notable that nearly all existing disputes involving vessel-based investments—such as offshore bunkering cases like the M/V “Saiga” case and the Virginia G case (Chang et al., 2024), or resource exploration and development in contested maritime zones, as in the Ghana v. Côte d’Ivoire maritime delimitation case—have been brought directly under UNCLOS’s dispute settlement procedures, without any attempt to invoke ISDS or alternative dispute settlement mechanisms.44

However, it is important to note that the dispute settlement mechanism under UNCLOS and the ISDS mechanism operate independently of one another. As such, investors may pursue remedies under both systems concurrently or engage in “forum shopping” depending on their strategic interests. In the M/V Louisa and M/V Norstar cases in ITLOS, parallel proceedings under UNCLOS and domestic judicial systems were already observed (Gates, 2017). Looking ahead, host States may increasingly face simultaneous legal actions under both UNCLOS and ISDS mechanisms. In such scenarios, a finding of liability in either forum could expose the State to the risk of “losing on all fronts.”

Beyond the pressures associated with dual-track dispute settlement, a more serious practical risk lies in the potential for UNCLOS and IIAs—due to their fundamentally different value orientations—to produce entirely contradictory legal rulings concerning the same conduct. This risk has already been vividly demonstrated in previous instances of jurisdictional overlap between UNCLOS and the WTO dispute settlement system. For example, in the DS193 Chile — Measures affecting the Transit and Importing of Swordfish, Chile, citing the need to conserve swordfish stocks, prohibited EC vessels engaged in swordfish fishing from entering its ports and unilaterally processed the catches. As a result, both parties initiated separate proceedings: Chile brought a case before ITLOS, arguing that the EC’s actions violated Articles 64 and 116–119 of UNCLOS concerning the conservation of marine living resources, while the EC filed a complaint with the WTO, alleging that Chile’s port restrictions breached GATT Articles V and XI (Orellana, 2001).

The root of the Swordfish dispute lies in the inherent tension between fisheries conservation measures—endorsed and encouraged under UNCLOS—and their potential incompatibility with trade rules under WTO law (Myers, 2005). This type of value-based conflict, which shapes how different dispute settlement mechanisms are applied, can just as easily manifest between UNCLOS and IIAs. In the Swordfish case, both Chile and the European Community, as State actors and equal subjects of international law, were ultimately able to reach a tacit understanding and withdraw their respective claims (Myers, 2005). However, if a jurisdictional overlap arises between UNCLOS and ISDS—where the former involves inter-State proceedings and the latter centers on investor-State disputes—the misalignment of parties may make it significantly more difficult to reach any mutual accommodation or coordinated resolution.

If the same maritime investment dispute is adjudicated simultaneously under both mechanisms, and the host State’s measures are clearly supported by UNCLOS, those measures are likely to be upheld within the UNCLOS dispute settlement framework. For instance, in the Southern Bluefin Tuna case, the tribunal, in its order on provisional measures, explicitly encouraged States to adopt conservation measures aimed at maintaining the optimal populations of highly migratory species, pursuant to Articles 64 and 116–119 of UNCLOS.45,46 However, under the ISDS mechanism, if the arbitral tribunal adopts reasoning akin to that in the Santa Elena v. Costa Rica case, the same regulatory measures—despite their alignment with UNCLOS obligations—may still be deemed a violation of the IIA, thereby obligating the host State to assume international responsibility.

5 Some suggestions on the application of IIAs in non-territorial waters

The emergence and development of territorial clauses has qualified an increasing number of IIAs for application in non-territorial waters, and State practices in extraterritorial jurisdiction have provided a more solid foundation for such application. Yet, the current situation reveals that the lack of territorial clauses and the unclear language in existing territorial clauses has created uncertainty for the application of many IIAs in non-territorial waters. On the other hand, there is significant room for interpretation regarding the types and scope of jurisdiction that States can exercise in non-territorial waters. To protect investments in non-territorial waters more effectively, it is essential for States to make some adjustments to IIAs and continue enriching extraterritorial jurisdiction practices. Additionally, investors may explore the possibility of obtaining protection under IIAs through “treaty shopping” strategies.

5.1 Expanding the geographic scope of IIAs through the revision of territorial clauses

In order to better protect the rights and interests of investors engaged in maritime investments in non-territorial waters, States should consider the requirements of different types of maritime investment and adjust the IIAs that are in force. The most direct adjustment approach is to terminate the existing IIAs and incorporate territorial clauses allowing for their application in non-territorial waters in new IIAs. Further, States should also pay attention to their obligations under IIAs to protect investments in non-territorial waters.

Expanding the geographic scope of IIAs through territorial clauses should be considered as the first step. Revising existing IIAs is the most direct approach, but it may not necessarily achieve the most ideal results. On the one hand, unilateral termination of IIAs may have significant adverse effects on international investment in the short term, as evidenced by India’s large-scale termination of IIAs in the past decade (Kotyrlo and Kalachyhin, 2023). On the other hand, negotiating new IIAs can be a time-consuming process. In the interim period before new IIAs are enacted, if existing ones have already been terminated, the sunset clauses of the terminated IIA can only provide protections for investments made before the date of treaty termination. As a result, if other provisions of an IIA adequately meet the practical needs of safeguarding maritime investments, States can also, in accordance with Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, provide legally binding interpretations on the scope of the agreement through subsequent agreements or practices. Alternatively, during the arbitration process, States can also achieve the application of IIAs in non-territorial waters by responding to the arbitration tribunal’s invitation or submitting opinions on treaty interpretation to the tribunal in the capacity of a non-disputing party (Titi, 2017).

It is important to recognize that extending the application of IIAs to non-territorial waters can be a double-edged sword, potentially enabling foreign investors to file claims or even exploit their rights in various investments. Particularly for many developing States with limited law enforcement and judicial capacity, expanding the geographic scope of IIAs to cover more investments in non-territorial waters could place considerable pressure on them. This could not only hinder their ability to develop and utilize marine resources but also jeopardize their existing maritime economic development goals, resulting in unnecessary economic losses (Mariama, 2012). Therefore, if the application of certain IIAs to non-territorial waters is anticipated to trigger a surge in investment disputes between States and investors in the short term, States should make efforts to prevent this outcome. By flexibly revising and interpreting IIAs, States can better align the expansion of their geographic scope with the practical needs of maritime investment protection. Additionally, if a State seeks to avoid assuming uncertain obligations for investment protection in various non-territorial waters, it could include explicit territorial clauses in its IIAs rather than relying on implicit ones. These clauses would clearly define the non-territorial waters covered by the IIA, helping to reduce uncertainties in treaty interpretation and implementation.

The expansion of the geographic scope of IIAs may have other impacts to host States, especially in cases where a host State has more than one legal unit within its territory. Take China as an example. A prominent issue is whether the IIAs in force between China and other States also have legal effects on Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Since China’s IIAs generally do not explicitly exclude the application of these legal units in the territorial clauses, if maritime investment such as submarine cables and pipelines in these legal units face unfair treatment, investors may directly invoke IIAs between China and their home State for remedies. Previous cases like the Señor Tza Yap Shum v. Peru and Sanum Investments Limited v. Laos have already sounded the alarm for such potential risk (Pathirana, 2017). If a State has multiple legal units, it is therefore essential to distinguish the legal effects of IIAs in different legal units through territorial clauses. For example, China, should explicitly excludes the legal effect on Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan through territorial clauses of its IIAs.

Undoubtedly, territorial clauses are essential in determining the application and legal effects of IIAs in non-territorial waters. As more non-territorial waters can be included in the geographic scope of IIAs, States should raise standards for the protection of foreign investment in these areas. By ensuring full compliance with their investment protection obligations under applicable IIAs, States can mitigate the risk of potential liability for IIA violations.

5.2 ISDS proceedings should provide necessary support for the application of IIAs in non-territorial waters

The applicability of IIAs to investments in non-territorial waters depends not only on the provisions of the treaties themselves, but also on how arbitral tribunals interpret and apply IIAs in conjunction with UNCLOS and other relevant rules and standards, as well as on the participation of stakeholders in the investment. In this process, several questions become particularly important: how arbitral tribunals interpret IIAs with different types of territorial clauses; how they apply UNCLOS and other public international law treaties to establish the territorial nexus of an investment; and how they view the legal standing of interested parties within ISDS proceedings. For maritime investments to operate with legal certainty and for related disputes to be resolved consistently, ISDS practice must develop coherent, predictable frameworks to address these intersecting issues of treaty interpretation and jurisdictional competence.

To date, only a small number of ISDS cases have touched upon the interpretation of territorial clauses and the application of UNCLOS or other rules of public international law, and even fewer have resulted in clear procedural or practical rules. Building on the analysis of these two issues in the preceding sections, several points merit particular attention from arbitral tribunals:

First, although an increasing number of IIAs explicitly allow for application in non-territorial waters, the general rule under Article 29 of the VCLT remains a standard that tribunals must strictly observe. In other words, in the absence of a territorial clause, the relevant IIA would, as a general matter, not qualify for application in non-territorial waters. While a few cases—such as Mobil and Murphy Oil v. Canada—involved IIAs without territorial clauses being applied to non-territorial waters (Harrison, 2020), this does not mean that IIAs inherently possess such applicability; rather, it reflected an implied consent between the disputing parties to extend the spatial scope of the IIA. Where no such agreement exists, the tribunal must strictly adhere to the provisions of the territorial clause when interpreting whether the IIA may be applied in the relevant waters.

Second, with respect to applying UNCLOS or other rules and standards of public international law to determine the host State’s jurisdiction, although UNCLOS itself does not form part of an IIA, it constitutes a necessary component in establishing a territorial nexus. Tribunals therefore clearly possess incidental jurisdiction over such matters. Moreover, existing arbitration rules do not preclude tribunals from applying rules of public international law outside IIAs in resolving investment disputes (Newcombe and Paradell, 2009). Accordingly, applying UNCLOS solely to clarify jurisdiction does not, in itself, constitute an excess of power. However, given that the host State’s jurisdiction over many investments in non-territorial waters is inherently uncertain, tribunals should proceed with caution. On the one hand, decisions or awards rendered by the ICJ, ITLOS, or Annex VII tribunals under UNCLOS on the jurisdiction over relevant maritime activities provide authoritative guidance that ISDS tribunals may refer to. Where a consistent view has been formed in such public international law precedents, tribunals should refrain from readily departing from it, so as not to undermine the authority of those decisions. On the other hand, if in a particular investment dispute the investor also challenges the host State’s exercise of jurisdiction, such a jurisdictional dispute may constitute a prerequisite for establishing a territorial nexus, and potentially falling outside the tribunal’s incidental jurisdiction (Duan and Liu, 2024). In such circumstances, the tribunal might consider declining jurisdiction over the investment dispute and require the investor to resolve the public international law dispute through mechanisms such as ITLOS before proceeding, thereby avoiding manifestly exceeded its powers.

Finally, applying IIAs to investments in non-territorial waters will inevitably involve certain stakeholders, such as other claimant States over the disputed waters or other entities holding significant interests in the investment. Tribunals must take such interests into account within the confines of existing procedures. While the amicus curiae mechanism allows third parties to submit written observations, it does not confer upon indispensable third parties in disputed maritime investment cases the same legal standing as the disputing parties (Galindo and Elsisi, 2021). Nor does it provide an adequate means for such parties to express State consent or to participate directly in the arbitration—precisely the source of much of the controversy over applying the Monetary Gold principle in ISDS practice. Where indispensable or significantly interested third parties exist, and the applicable IIA permits, the tribunal could consider establishing a dedicated procedure to enable their participation in the arbitration. Effective mechanisms developed in certain cases could be more widely adopted, thereby affording more robust protection for third-party interests in non-territorial waters investment disputes.

5.3 Achieving coordination between UNCLOS and IIAs through value compatibility

Compared to the prescriptive gaps within UNCLOS concerning specific maritime investments, the value-based conflicts between UNCLOS and IIAs may pose an even greater obstacle to the effective application of UNCLOS in maritime investment disputes. Ensuring that core obligations under UNCLOS—particularly those related to the protection of the marine environment—are upheld in investment disputes without triggering breaches of IIA provisions requires thoughtful institutional innovation (Andreotti, 2024). A coordinated mechanism that legally binds IIA signatories, investors, and ISDS tribunals is essential.

Such coordinated mechanisms can be constructed in two principal ways. First, IIAs should expressly recognize UNCLOS as an applicable source of law. Many modern IIAs already require arbitral tribunals to consider “applicable rules of international law.” Expanding and refining this language to specifically reference UNCLOS would help ensure its consistent application in relevant disputes. Second, to mitigate normative and value-based conflicts, IIAs should incorporate exception clauses exempting States from liability when they are fulfilling their obligations under UNCLOS. Some IIAs already contain general exceptions related to environmental protection,47 while others—such as the Belarus–Zimbabwe BIT and the Japan–Georgia BIT—go further by detailing environmental responsibilities applicable to both investors and States.48