Abstract

Introduction:

The myodural bridge (MDB) is considered one of the circulatory dynamics of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Initially identified in the human neck, it has since been documented across diverse vertebrates, including fish with analogous “MDB-like” structures. The teleost Takifugu rubripes, which exhibits a high degree of genetic homology with humans, serves as an excellent model for such comparative studies. Investigating its MDB-like structure can therefore provide a morphological basis for elucidating the mechanism of CSF circulation and its evolution during the vertebrate land–water transition.

Methods:

In this study, the morphology, development, and ultrastructure of MDB-like structure of Takifugu rubripes were explored. Three fresh adult T. rubripes were selected for gross anatomy. After incubation, 33 T. rubripes aged 13–120 days after hatching (dah) were fixed in 10% formalin solution. The samples aged 50–120 dah were further decalcified with EDTA for histological paraffin sectioning and Masson staining. Four cases aged 106 dah were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, two of which were observed by scanning electron microscopy, and two cases were observed by transmission electron microscopy.

Results:

Through light microscopy and electron microscopy, the results of the current study is that there are three types of fiber connections (MDB-like) between skeletal muscle and the spinal canal membrane in T. rubripes: (1) The fibers from the myocomma attach to the spinal canal membrane; (2) The epimysium connects to the spinal canal membrane directly or connects to the spinal canal membrane through reticular, filamentous fibers, or fibers emitting from the perimysium; and (3) The fibers from the end of the muscle bundle stop at the spinal canal membrane. These connections mainly exist on the sides of each vertebral interspace and may function similarly to the MDB.

Discussion:

Developmentally, “MDB-like” structures appeared in T. rubripes hatched at 18 dah, began to transmit force at 21 dah, and may have a positive correlation in development with the muscle and spinal canal membrane. This experiment provides developmental morphological information for comparative studies on the conservation and interspecies differences of MDB in evolution and provides informational support to explore the physiological function of MDB in humans.

1 Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a colorless and transparent fluid in the ventricles, central spinal canal, and subarachnoid space. It primarily functions to protect and nourish nerve tissue, transport metabolites, and regulate intracranial pressure (Sakka et al., 2011). CSF circulation is a significant topic in vertebrate research, yet the driving force behind it remains controversial. Currently, it is believed that the CSF circulation is influenced by several factors: (1) The heartbeat plays a key role in driving CSF circulation (Mestre et al., 2018; Wagshul et al., 2011); (2) The respiratory cycle has the greatest impact on CSF flow (Vinje et al., 2019); and (3) Body position also contributes to the differences in CSF flow (Alperin et al., 2005). In 1995, Hack et al. proposed a structure called the myodural bridge (MDB), which is primarily located in the atlanto-occipital space and atlanto-axial space. The MDB is a dense fiber connection between the deep suboccipital muscles and the spinal dura mater (SDM) (Hack et al., 1995). In recent years, some scholars suggested that the contraction of the suboccipital muscle can pull the MDB structure and thus pull the SDM. This action changes the volume of the subdural cavity, thereby creating negative pressure and forming a dynamic “pump” that influences CSF circulation (Zheng et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2021). Recent studies have demonstrated that MDB is a common homologous organ in mammals (Zheng et al., 2017). Its existence has been confirmed in various vertebrates, including birds (Okoye et al., 2018; Dou et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021), reptiles (Zhang et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2019; Li et al., 2022), amphibians, and even fishes, which exhibit an MDB-like structure (Cheng et al., 2025). This structure is described as muscle fibers connecting to the spinal canal membrane through myocomma fibers or directly anchoring to the spinal canal membrane. The MDB is now considered a universal and conserved anatomical feature in vertebrates (Cheng et al., 2025).

From an evolutionary perspective, fish represent the ancestral vertebrate group, and a growing body of research suggests that studying fish can provide key insights into vertebrate evolutionary processes (Gai et al., 2022; McClelland, 2012). Therefore, investigating the morphology and developmental patterns of MDB-like structures in fish may provide phylogenetically ancient evidence to understand the driving mechanisms of CSF circulation. Furthermore, such studies could provide critical insights into how the anatomical basis and physiological functions of CSF circulation evolved as vertebrates transitioned from aquatic to terrestrial environments.

This study employs the aquatic non-mammalian vertebrate T. rubripes as the experimental model. As a representative pufferfish species belonging to Osteichthyes and Tetraodontiformes, this organism serves as a premier model organism for genomic studies. Its genome assembly represents the gold standard in fish gene mapping, demonstrating remarkable homology with humans (Gao et al., 2017), and its genome has been widely used as a reference for the evolution of vertebrate genome (Kai et al., 2011).

The purpose of this study is to explore the fiber structure of T. rubripes similar to the MDB, characterize their developmental morphology, and establish a comparative morphological foundation to analyze both the evolutionary conservation and species-specific adaptations of MDB across vertebrate lineages.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

A total of 40 specimens of T. rubripes were collected from the Aquaculture Center of Ocean University. This cohort included three fresh adult specimens and 33 fixed specimens (13–120 days post-hatching, dph). The day of hatching was designated as day 1 and so forth; these were preserved in 10% formalin solution. Specimens aged 13–40 dph were sampled every 5 days, those aged 40–120 dph were sampled every 10 days, and three adult specimens aged 4 years were collected. Among them, four specimens at 106 dph were sampled for electron microscopy preparation. The 120-dph specimens measured approximately 165 mm in total length. For tissue processing, the cephalic and abdominal regions were excised, followed by division of the remaining body into six equidistant segments prior to 10% formalin fixation. Specimens aged 50–120 dph underwent EDTA-mediated decalcification. Additionally, four 106-dph specimens were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for ultrastructural analysis.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Gross anatomy

Three fresh adult T. rubripes specimens (approximately 450 mm in total length) that died naturally were systematically dissected. The integumentary system was removed, and transverse sections were created at the throacocadual vertebral junctions, thereby fully exposing the spatial relationship between the vertebral centra, the spinal canal, and the lateral muscles in cross-sectional view. Subsequent dissection involved midline separation of dorsal musculature along the neural spine, with bilateral retraction of tissue planes to visualize their anatomical connection with the spinal canal membranes.

Imaging was performed using a stereomicroscope (Jiangnan Yongxin, Model NOVEL) and a smartphone (Apple iPhone 8) for microscopic visualization and gross morphological documentation.

2.2.2 Histological sectioning and staining

Following fixation, specimens aged 13–120 dph (approximately 3–165 mm in total length) underwent continuous water irrigation overnight. Among them, for the juvenile specimens (13–86 dph, 3–30 mm), no tissue trimming was required, whereas adult-stage specimens (120 dph, 165 mm) required partial resection of the superficial lateral muscle, retaining a part of tissue close to the spinal canal. Notably, the specimens within 13–40 dph were exempt from decalcification protocols, proceeding directly to dehydration after washing.

For specimens aged 50–120 dph, decalcification was performed using an EDTA decalcifying solution (100 g EDTA, 450 mL distilled water at 60°C–70°C, 15 g NaOH, 500 mL PBS (pH 7.2–7.3), brought to a final volume of 1,000 mL with distilled water). This decalcifying solution offers minimal tissue disruption and maintains optimal staining quality. The decalcifying solution was refreshed every 5 days until complete decalcification was achieved, as determined by a needle being able to easily penetrate the bone. The decalcification time ranges from 7 days to 1 month, depending on the age of the fish. After decalcification, the samples were rinsed under running water for 24 h. Conventional dehydration, clearing, and paraffin embedding protocols were followed. The embedded tissue blocks were sectioned into 6-μm-thick slices using a rotary microtome (Leica Micro HM450, Leica Microsystems Co., Ltd., Wetzlar, Germany) and stained with Masson’s trichrome.

2.2.3 SEM and TEM

Four 106-day cases (approximately 5 cm in length) died naturally. After complete fixation in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution at 4°C, the samples were rinsed with running water. The skin and abdominal tissue were removed, and the specimens were sectioned transversely into 2-mm-thick tissue blocks. Based on histological staining results, further processing was performed under a stereomicroscope, namely:

SEM sample preparation: (1) Transverse section: The tissue block was trimmed while preserving the between the lateral muscle and the spinal canal membrane. (2) For the coronal section, the tissue block was oriented with the cut surface facing upward, and the dorsal aspect of the spinal canal was sectioned transversely to obtain a clean and uniform plane. All tissue blocks were approximately 4 × 3 × 2 mm.

TEM sample preparation: (1) Transverse sections were trimmed to preserve the critical interface between the lateral muscle and the spinal canal membrane, with careful removal of surrounding tissues. (2) Coronal section: Sectioning was performed using the same method as for scanning electron microscopy. All tissue blocks were approximately 1 × 1 × 2 mm.

3 Results

3.1 Gross anatomical results

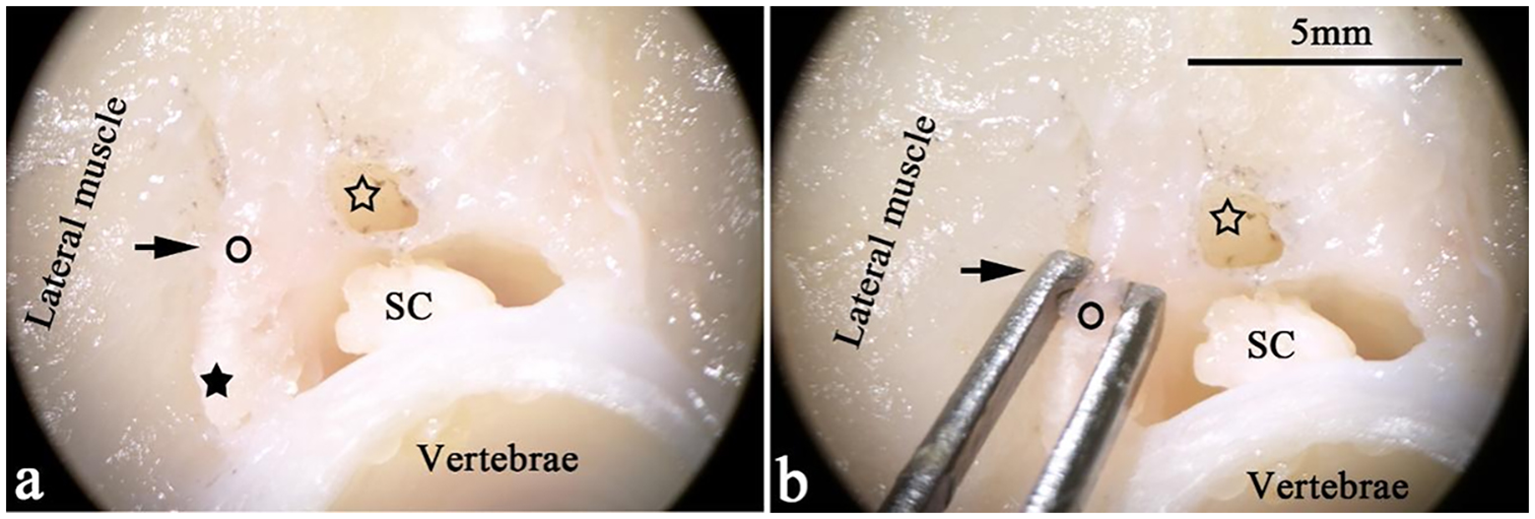

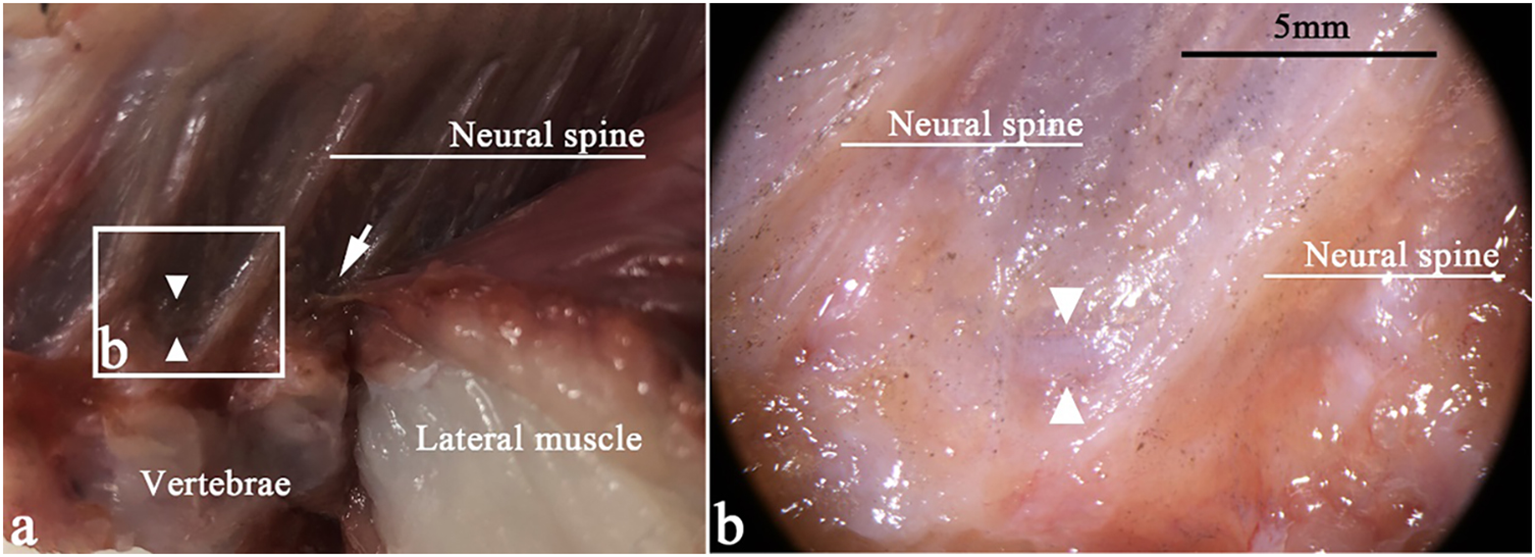

Observations in T. rubripes transverse section: The spinal canal was positioned dorsally to the vertebral centrum, with lateral muscle wrapping around its lateral sides. The walls on both sides of the spinal canal are closed by the spinal membrane and the medullary arch connecting adjacent vertebrae (Figure 1). Therefore, the spinal membrane participates in sealing the spinal canal symmetrically and intermittently along its length. The translucent spinal canal membrane exhibited significant mobility and elasticity when pulled with tweezers (Figure 1). The sagittal section revealed a fiber connection between the exposed lateral muscle and the spinal canal membrane (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Transverse sections of T. rubripes at the cranial thoracic segment. ○, spinal canal membrane; ★ (black star), medullary arch; SC (spinal cord), spinal cord; ☆ (hollow star), dorsal lumen of the spinal canal. (A, B) The pictures show the connection between the lateral muscle and the spinal canal membrane (→) under a stereomicroscope. A “lumen” (☆) of the same length and parallel to the spinal canal is on the back of the spinal canal. (B) The thickness of the spinal canal membrane is approximately 1 mm.

Figure 2

Sagittal section of T. rubripes at the anterior caudal vertebra. △, spinal canal membrane; →, fiber connection between the lateral muscle and the spinal canal membrane (△). (A) Fiber connection between the lateral muscle and the spinal canal membrane (△). (B) High-magnification view of the squares in (A). There is a spinal membrane (△) between two neural spines, sealing the spinal canal.

3.2 Histological results

Masson staining of paraffin sections revealed that the muscle tissue was stained red, while the collagen fibers appeared green.

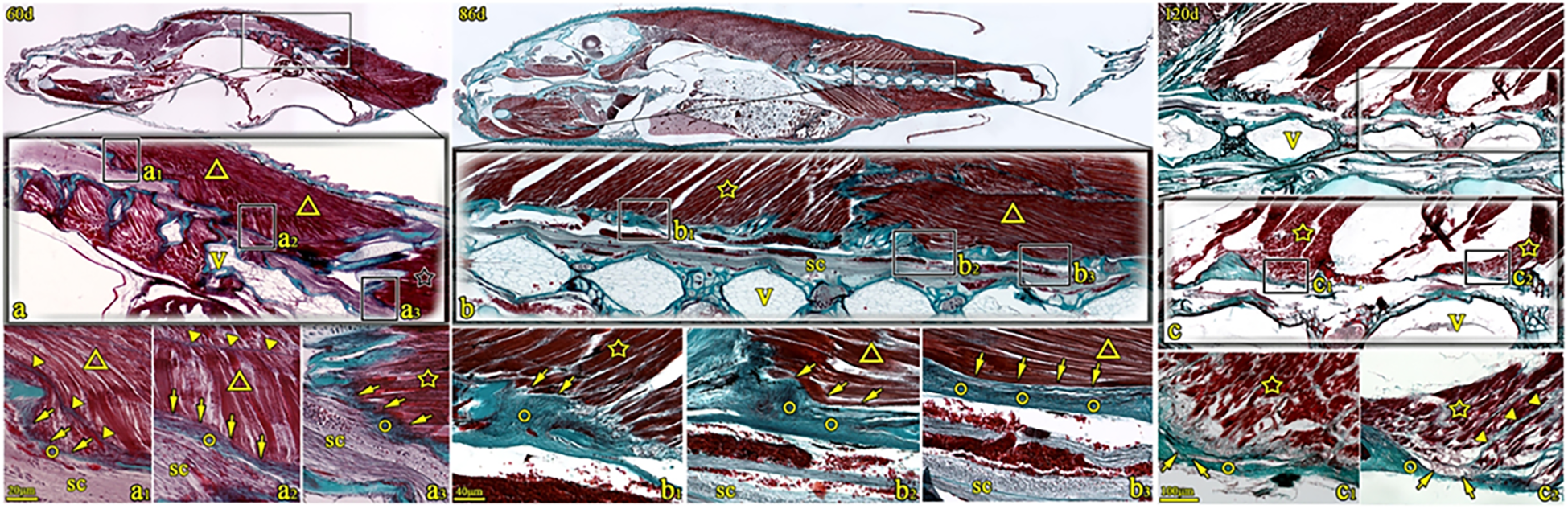

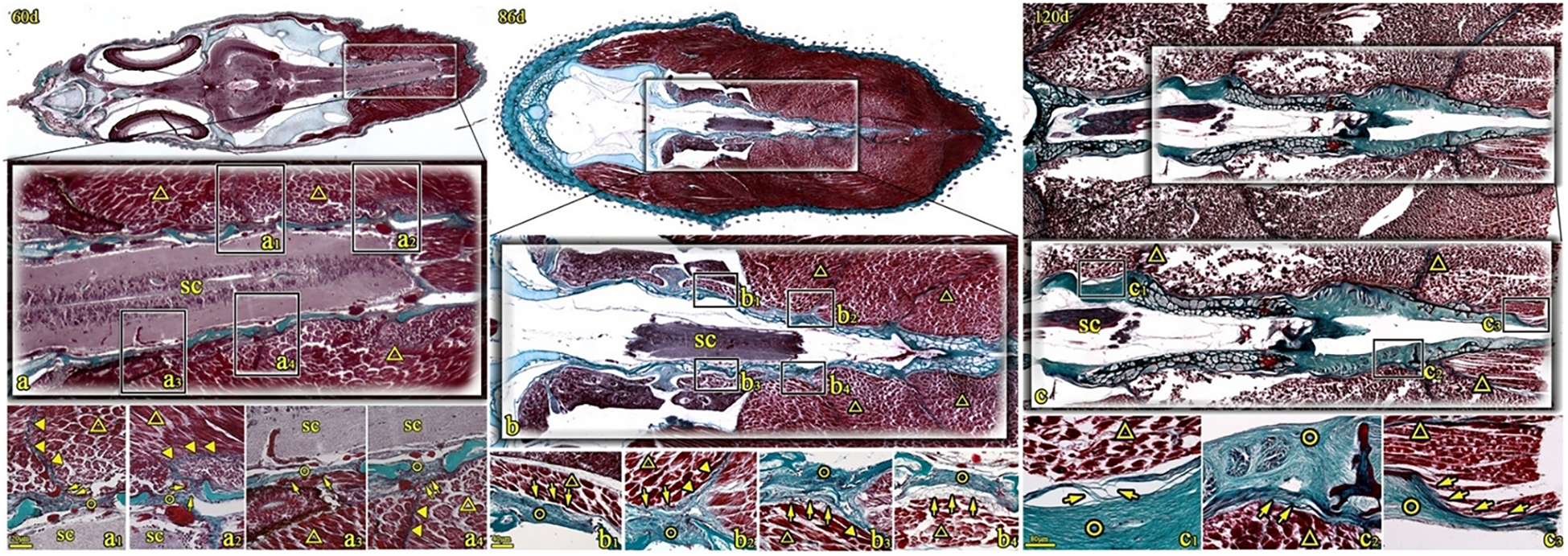

3.2.1 Fiber connections between muscle and spinal canal membrane (60, 86, and 120 dph)

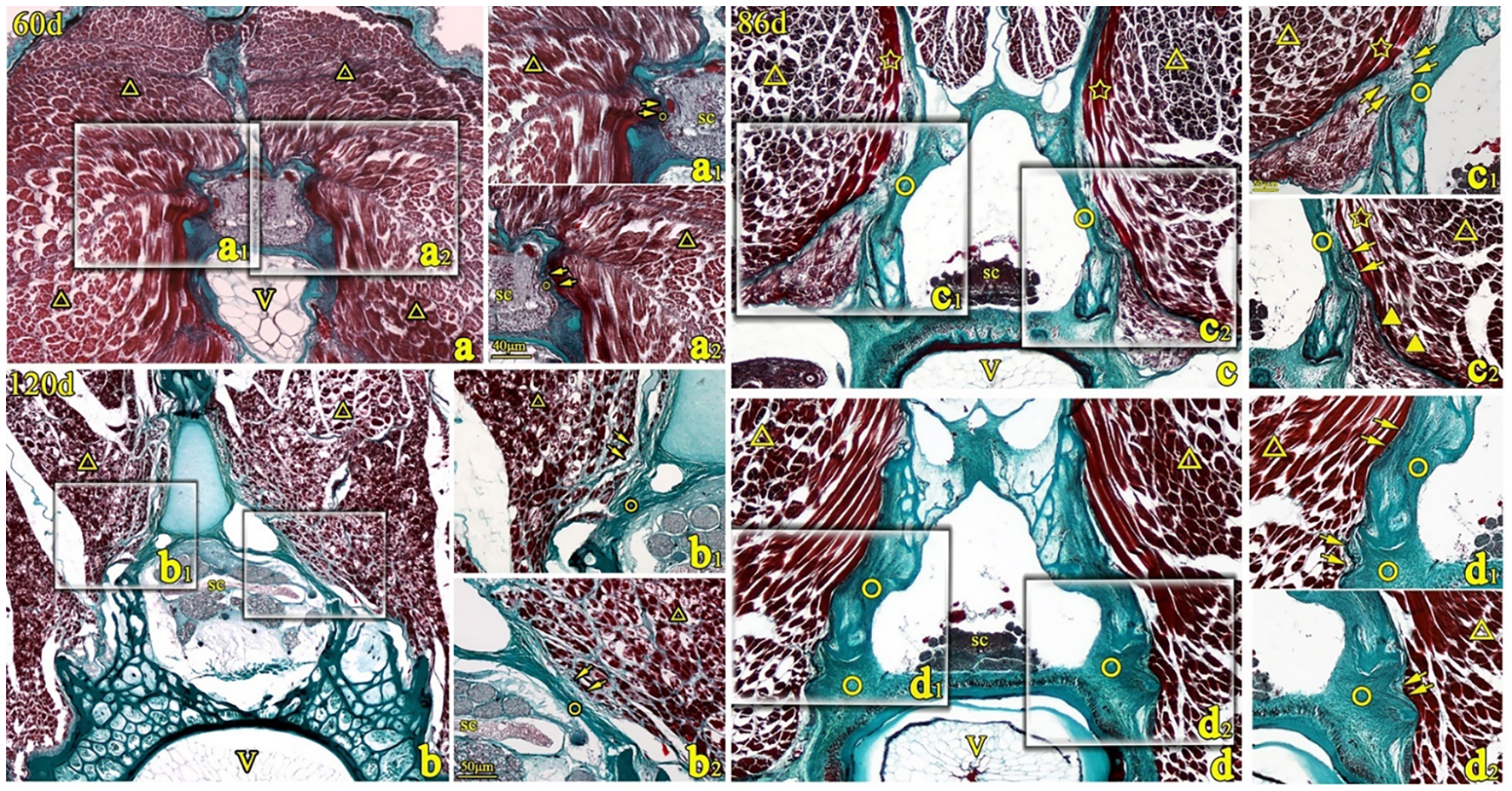

The morphology and arrangement of these fiber connections were consistent across sagittal, coronal, and transverse sections. The spinal canal membrane was composed of dense fibers, and sagittal and coronal sections further revealed that the spinal canal membrane symmetrically sealed the lateral side of the spinal canal and bridged the medullary arches (Figures 3 and 4). The transverse section showed that the dorsolateral part of the spinal canal was enclosed by the spinal membrane (Figure 5).

Figure 3

Sagittal sections of T. rubripes at 60, 86, and 120 dph (Masson’s trichrome stain). V, vertebra centrum; ○, spinal canal membrane; ☆, dorsal fin muscle; ▼, myocomma; △, lateral muscle; SC, spinal cord; → (arrow), connection between muscle and membrane. a1–a3, b1–b3, and c1–c2 are high-magnification views of the squares in a–c. The spinal canal membrane (○) intermittently seals the dorsolateral spinal canal. The dorsal fin muscle (☆) obliquely inserts into the spinal canal membrane (○) structure (→, a3 and b1). Alternatively, the epimysium is connected to the spinal canal membrane (○) (→, c1 and c2). Muscle fibers of the major lateral muscle (△) connect with the spinal canal membrane (→, a1 and a2). Alternatively, the muscle fibers of the lateral muscle attaching to the membrane (○) (→, b2 and b3).

Figure 4

Coronal sections of T. rubripes stained with Masson’s stain at 60, 86, and 120 days. ○, spinal canal membrane; △, lateral muscle; ▼, myocomma; SC, spinal cord; →, connection between muscle and membrane. a1–a4, b1–b4, and c1–c3 are high-magnification views of the squares in (A–C). The spinal canal membrane (○) intermittently seals the dorsolateral spinal canal. The epimysium of the lateral muscle (△) is directly attached to the membrane (○) (→, a3, b1, b3, and c2) or connected to the spinal canal membrane through reticular fibers (→, b4) and some filamentous fibers (→, c1). Some lateral muscles (△) are obliquely inserted into the spinal canal membrane (○) through the fibers at the end of the muscle bundle (→, c3). The myocomma (▼) is directly attached to the spinal canal membrane (a1, a2, a4, and b2).

Figure 5

Transverse sections of T. rubripes with Masson’s stain at 60, 86, and 120 days. V, vertebral centrum; ○, spinal canal membrane; △, lateral muscle; ▼, myocomma; SC, spinal cord; →, connection between muscle and membrane. a1, a2, b1–b3, c1, c2, d1, and d2 are high-magnification views of the squares in (a–d). The epimysium of the lateral muscle (△) is directly connected to the spinal canal membrane (○) (→, a1, a2, d1, and d2) or the fibers emitted by the perimysium are collected into the epicardium and connected to the spinal canal membrane (○) (b1 and b2) or connected to the spinal canal membrane through a reticular connective tissue (→, c1). The myocomma (▼) of the lateral muscle is directly attached to the membrane (→, c2).

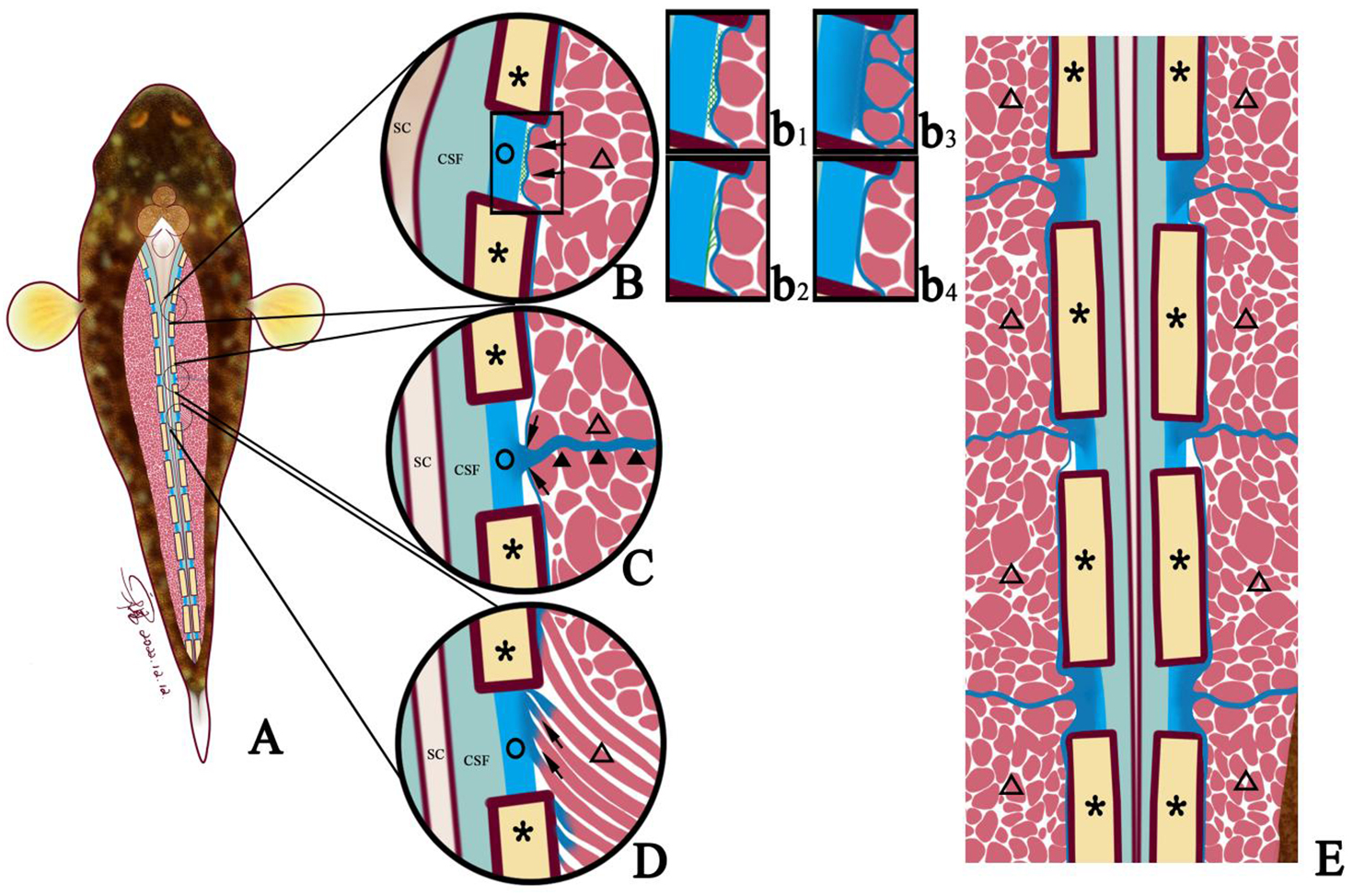

The lateral muscle and dorsal fin muscle connected to the spinal canal membrane via three primary ways (Figures 3–5), namely:

-

1. The end of the myocomma terminated symmetrically, attaching directly to the spinal canal membrane.

-

2. The epimysium connected to the spinal canal membrane through reticular or filamentary fibers and fibers emitted from the perimyslum or is directly attached to the spinal canal membrane.

-

3. Fibers from the muscle bundle ends inserted into the spinal canal membrane (Figure 6). Additionally, the intermuscular septum consistently interfaced with spinal membrane at every intervertebral space (Figure 6E).

Figure 6

Diagram showing three connection modes between muscle and spinal canal membrane. ○, spinal canal membrane; △, lateral muscle; ▲, myocomma; SC, spinal cord; *neural spine; SC, spinal cord; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; →, connection between muscle and membrane. (A) The connection (→) between the lateral muscle (△) and the spinal canal membrane (○) can be observed in each intervertebral space. (B) Connection between the epicardium and the spinal canal membrane (→); that is, the epicardium is connected to the spinal canal membrane (○) through reticular fibers (b1), filamentous fibers (b2), and perimysium converging to the epicardium (b3), and the epicardium is directly attached to the spinal canal membrane (○) (b4). (C) The lateral muscle (△) is connected to the spinal canal membrane (○) through the myocomma (▲). (D) The lateral muscle or dorsal fin muscle is connected to the spinal canal membrane (○) through the fiber (→) emitted from the end of the muscle bundle. (E) Coronal view of the myocomma (▲) of the lateral muscle symmetrically attached to the spinal canal membrane (○).

3.2.2 Development and change of fiber connection (18–60 dph)

Comparative observations were performed on three regions: the cranial segment of the thoracic vertebra, the middle thoracic segment of the vertebra (the choracocaudal junction), and the cranial segment of the caudal vertebrae.

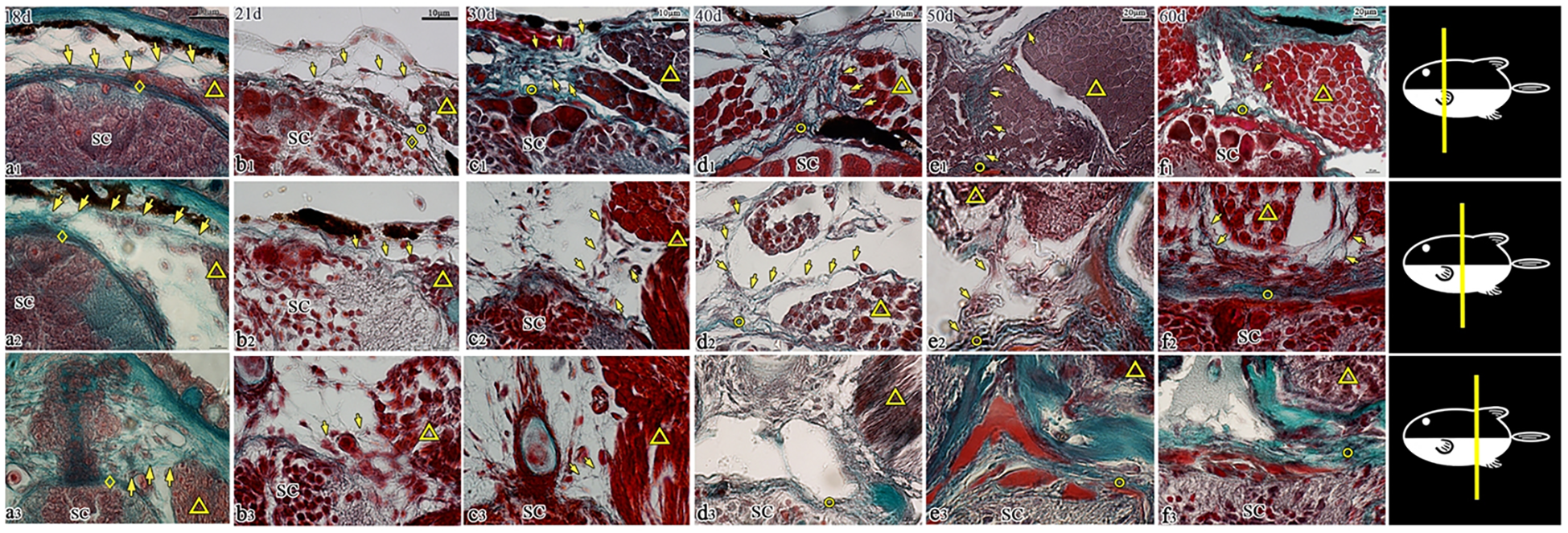

3.2.2.1 Dorsal spinal cord

At 18 days post-hatching, the spinal cord was wrapped by the spinal cord membrane, which was composed of multiple fibrous layers. A small number of muscle-derived fiber attached to the dorsal side of the spinal cord membrane and fused with it. At this stage, the stratification between the spinal cord membrane and the spinal cord membrane remained indistinct (a1–a3). By day 21, a clear gap became evident between the spinal canal membrane and the spinal cord membrane, and the spinal cord membrane clung to the spinal cord in the form of multilayer wavy fibers. Meanwhile, the filamentous fibers emitted by the muscles terminated at the spinal canal membrane without further penetration (b1–b3).

Serial slices from 21 to 60 dph were observed continuously, and it was found that the morphological development of T. rubripes varied slightly. For a detailed comparison, five key developmental stages (21, 30, 40, 50, and 60 dph) were selected. During this period, the spinal canal membrane exhibited increasing density, with its wavy fibers demonstrating a progressively tighter organization.

In the cranial–thoracic segment, muscle-emitted fibers progressively increased in number and aggregated into bundles that connected to the spinal canal membrane on the dorsal side of the spinal cord (Figures 7B1–F1). The middle thoracic segment of fish exhibited weaker fiber connections compared to the cranial segment, though it still showed an upward trend during development (Figures 7B2–F2). In contrast, the cranial segment of the coccyx showed a completely inverse pattern, and the connections between muscle and the spinal canal membrane gradually weakened and completely disappeared by 40 dph (Figures 7B3–F3).

Figure 7

Transverse sections of the dorsal spinal canal in T. rubripes (18–60 dph, Masson’s stain). ◇, spinal cord membrane; ○, spinal canal membrane; △, muscle; SC, spinal cord; →, connection between muscle and membrane; (A1–F1), cranial segment of the thoracic vertebra; (A2–F2), middle segment (junction of the thoracic segment and caudal segment); (A3–F3), cranial segment of the caudal vertebra. (A1–A3), a small amount of fibers (→) is emitted by the muscles and stops at the spinal cord membrane (◇). (B1), the fibers (→) emitted by the muscles stop at the spinal canal membrane (○). (A1–F1, A2–F2), the membrane outside the spinal cord gradually becomes denser, and the connection between the muscle and the spinal canal membrane (→) gradually strengthens; (A3–F3), the connection between the muscle and spinal canal membrane (→) is sparse (A3–C3) and disappears from d3 (D3–F3).

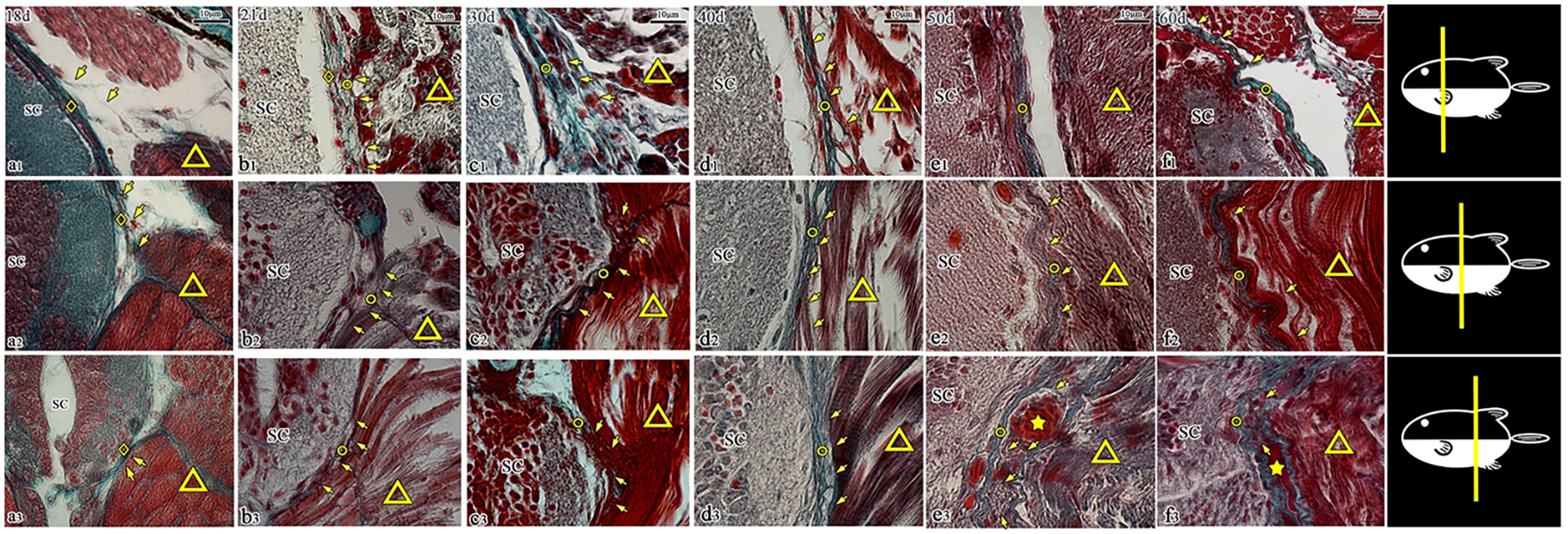

3.2.2.2 Both sides of the spinal cord

Serial slices from 18 to 60 dph (18, 21, 30, 40, 50, and 60 dph) were examined continuously. At 18 dph, skeletal muscle exhibited periodic transverse striations. During development, the spinal canal membrane gradually became dense, the muscle fibers of the lateral muscle gradually became full, and the connection between the muscle and the spinal canal membrane gradually became stronger in the middle segment of the fish and the cranial part of the coccyx (Figures 8B2–F2, B3–F3). Notably, these fiber connections disappeared in the cranial segment of the thoracic vertebra after 50 dph (Figures 8B1–F1). In caudal vertebrae segments at 50 and 60 days, it was observed that the fiber connections from the epimysium terminated at the spinal canal membrane and distributed around the blood vessels (Figures 8E3–F3).

Figure 8

Transverse sections of the spinal canal in T. rubripes (18–60 dph, Masson’s stain). ◇, spinal cord membrane; ○, spinal canal membrane; △, muscle; SC, spinal cord; ★, vascular structure; →, connection between muscle and membrane; (A1–F1), cranial segment of the thoracic vertebra; (A2–F2), middle segment (the junction of the thoracic segment and caudal segment); (A3–F3), cranial segment of the caudal vertebra; (A1–F1), the fiber connection (→) begins to disappear at e1; (A2–F2, A3–F3), the muscle fibers (△) gradually become fuller, and their connection with the spinal canal membrane (→) is gradually enhanced; e3, f3, filamentous fibers from the epicardium of the lateral muscle (△) are distributed around the vascular structure (★) and connected to the spinal canal membrane (○).

3.3 SEM results

The SEM results revealed that the spinal canal membrane consisted of multiple layers of thick, densely arranged fibers, with three distinct connection forms consistent with histological observations. On the transverse section, the muscular septum of the lateral muscle directly connected and fused with the spinal canal membrane (Figure 9), the fascicular fibers extending from the epimysium inserted into the spinal canal membrane (Figure 10), and some fibers from the ends of the muscle bundles traveled along the spinal canal membrane and finally fused with it (Figure 11). On the coronal section, the lateral muscle was closely attached to the spinal canal membrane through the epimysium (Figure 12).

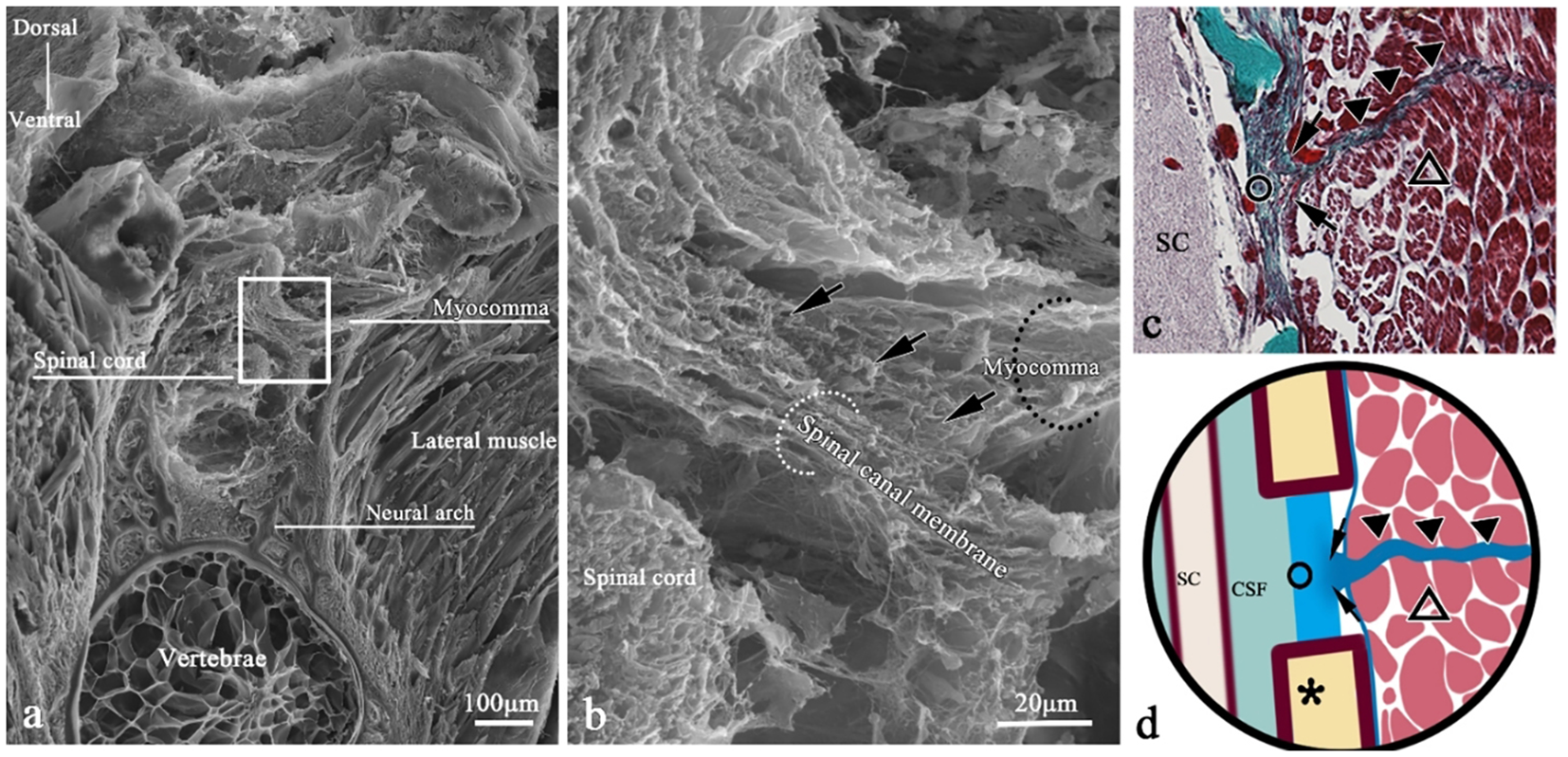

Figure 9

SEM of myocomma connection in a transverse section of T. rubripes. △, skeletal muscle; black dotted line/▲, myocomma; white dotted line, spinal canal membrane; *neural spine; SC, spinal cord; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; →, connection between muscle and membrane. (B) High-magnification view of the square in (A). It shows that the myocomma (black dotted line) is connected to the spinal canal membrane (white dotted line), interwoven with the spinal canal membrane and integrated. (C) Histological section corresponding to (A); Masson staining, showing skeletal muscle (△) attached to myocomma (▲) and myocomma connected to the spinal canal membrane (○). (D) Connection pattern diagram of myocomma.

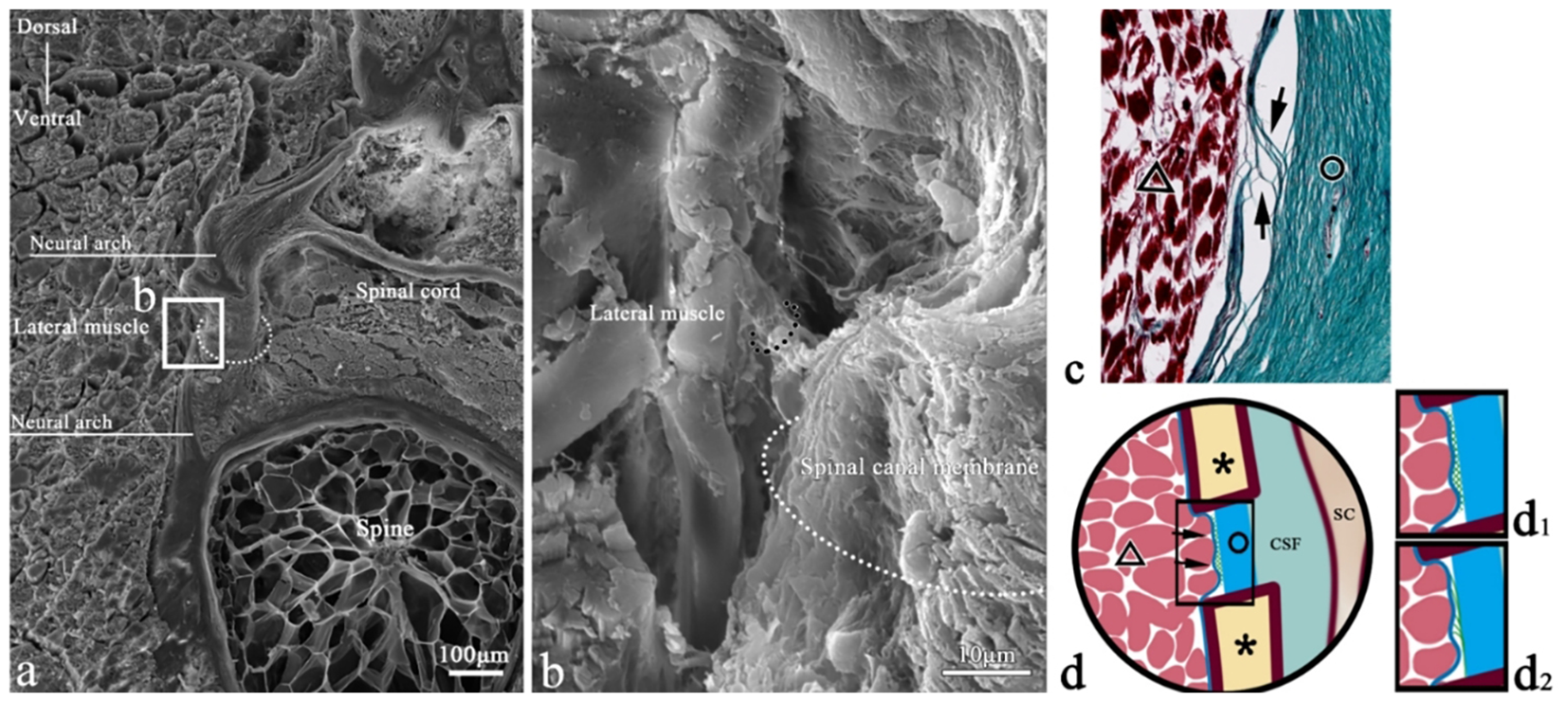

Figure 10

SEM of epimysium connection in a transverse section of T. rubripes. △, skeletal muscle; black dotted line/▲, myocomma; white dotted line, spinal canal membrane; *neural spine; SC, spinal cord; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; →, connection between muscle and membrane. (B) High-magnification view of the square in (A). The fibers (black dotted line) emitted from the epimysium are connected to the spinal canal membrane (white dotted line). (C) Histological section corresponding to (A); Masson staining, showing the fibers (→) emitted from the epicarsium of skeletal muscle (△) extending to the spinal canal membrane (○) and becoming part of the spinal canal membrane. (D) The connection pattern diagram of the epicarsium.

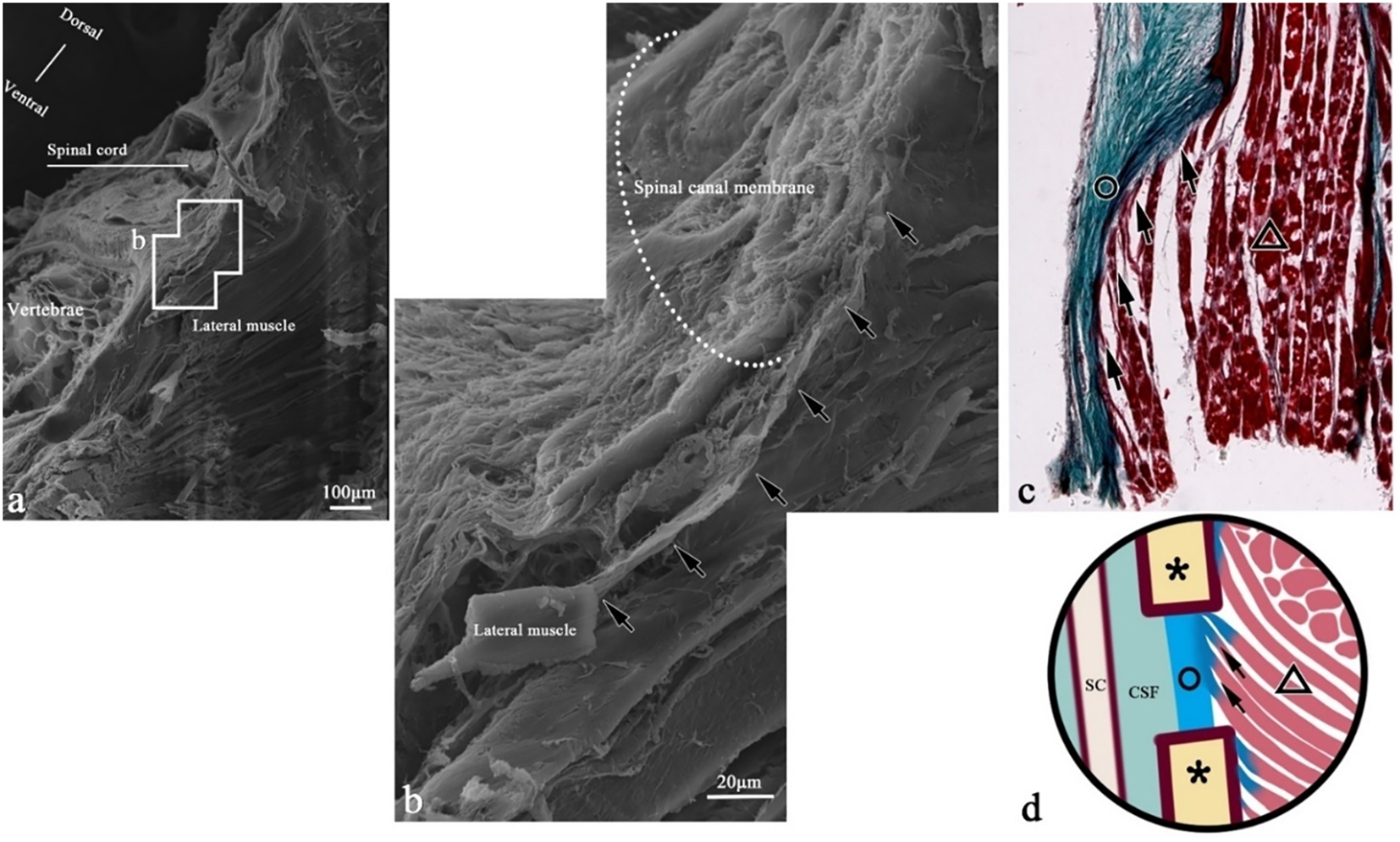

Figure 11

SEM of muscle bundle fiber connections in the transverse section of T. rubripes. △, skeletal muscle; black dotted line/▲, myocomma; white dotted line, spinal canal membrane; *neural spine; SC, spinal cord; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; →, connection between muscle and membrane. (B) High-magnification view of the square in (A). The fiber (→) from the end of the muscle bundle extends along the spinal canal membrane (white dotted line) and eventually becomes part of the spinal canal membrane. (C) Histological section corresponding to (A); Masson staining. Skeletal muscle fibers (△) are inserted into the spinal canal membrane (○), and the green fibers at the end of the muscle bundle are connected with the spinal canal membrane. The fibers (→) emitted from the epicarsium of skeletal muscle (△) extend to the spinal canal membrane (○) and become part of the spinal canal membrane. (D) Connection pattern diagram of the epicarsium.

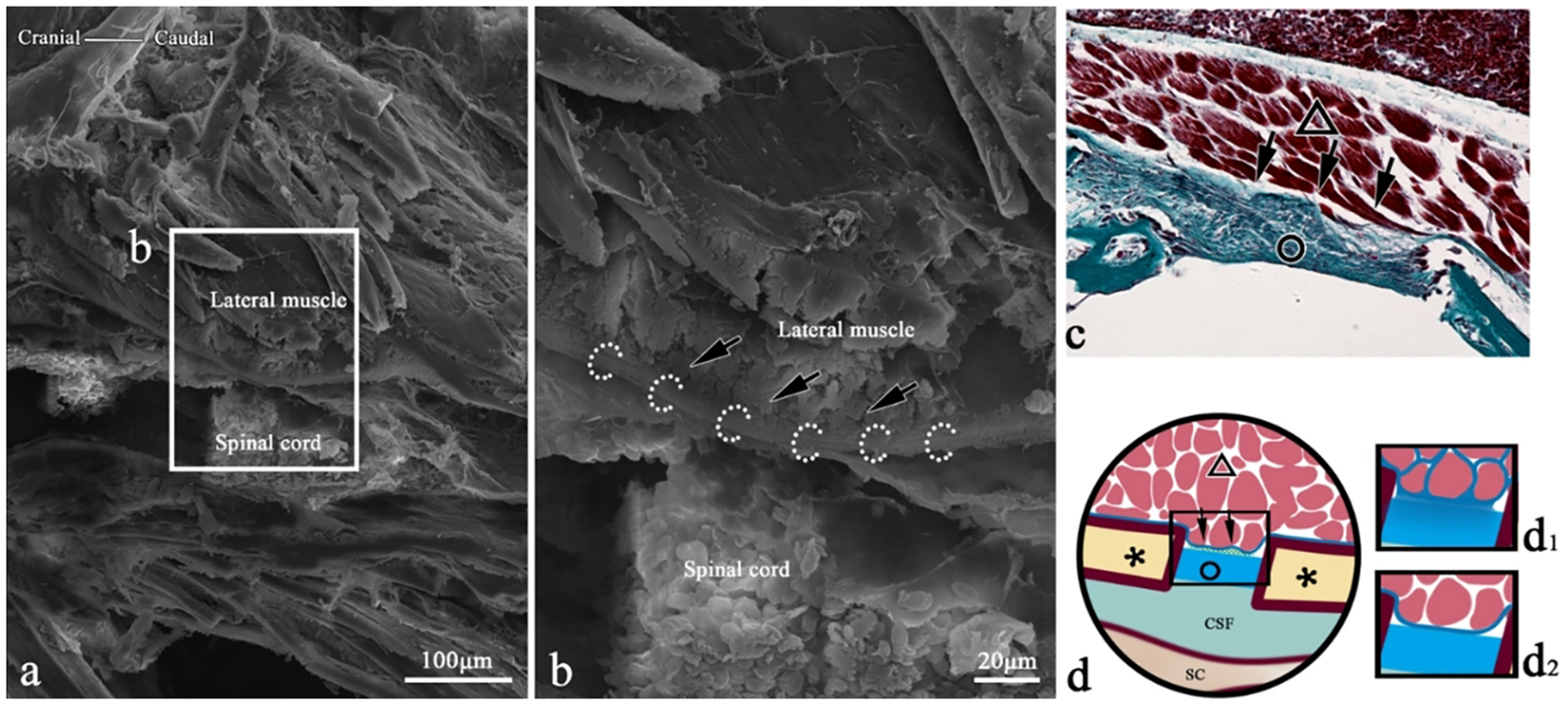

Figure 12

SEM of epimysium connection in the coronal section of T. rubripes. △, skeletal muscle; black dotted line/▲, myocomma; white dotted line, spinal canal membrane; *neural spine; SC, spinal cord; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; →, connection between muscle and membrane. (B) High-magnification view of the square in (A). The transverse section of the muscle bundle is clustered and clings (→) to the spinal canal membrane (white dotted line). (C) Histological section corresponding to (A); Masson staining. The epicarsium of the skeletal muscle (△) clings to the spinal canal membrane (○), indicating that the two types of collagen connective tissues dyed green are fused together (→). (D) Connection pattern diagram of the epicarsium.

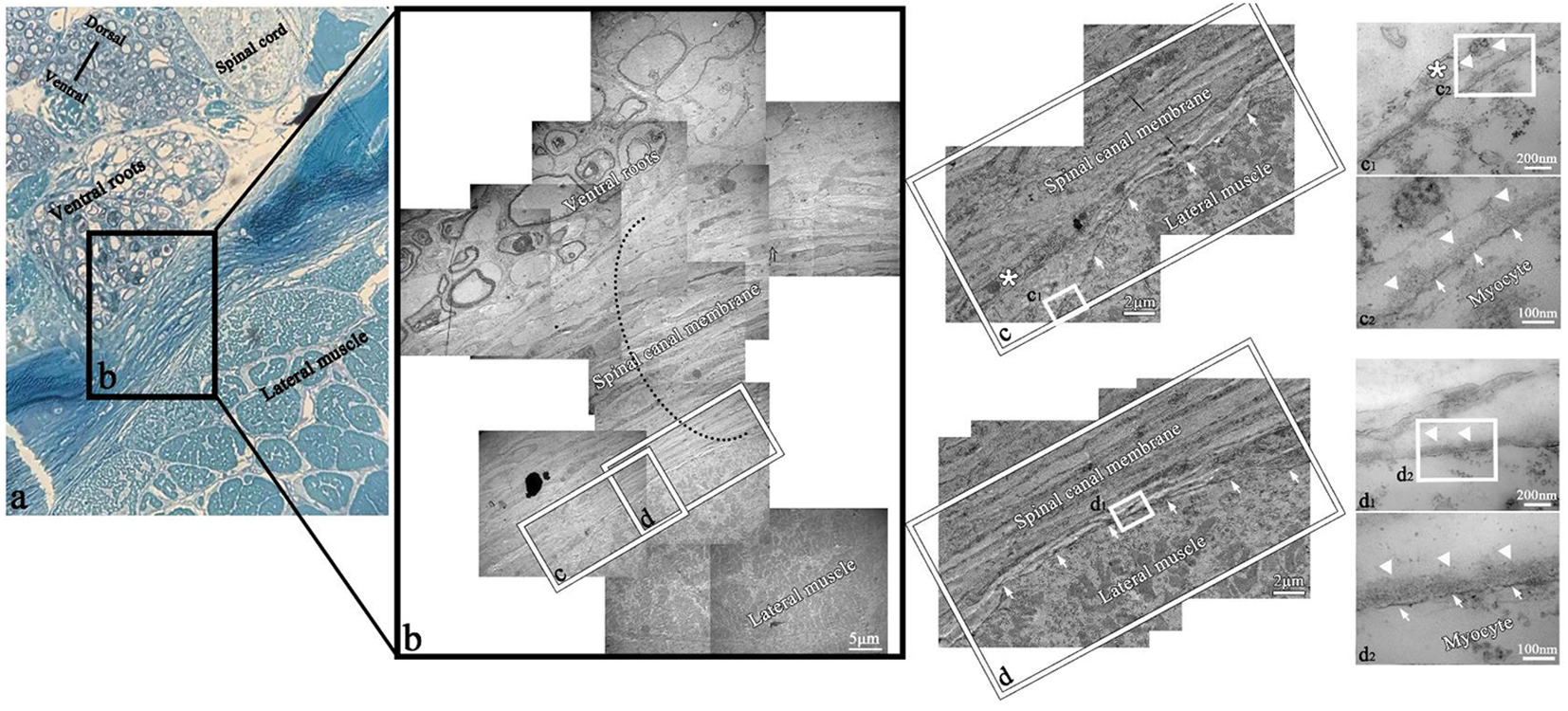

3.4 TEM results

Under TEM, the muscle clung to the spinal canal membrane (Figures 13B–D). At higher magnification (×300,000), the outer layer of muscle cells was composed of the muscle membrane and basement membrane, which interacted with the extracellular matrix secreted by fibroblasts (Figures 13C2, D2).

Figure 13

TEM of myocyte–fibroblast interface in the transverse section of T. rubripes. Black dotted line, spinal canal membrane; *fibroblast; SC, spinal cord; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; →, connection between muscle and membrane; △, connection between myocytes of the lateral muscle and fibroblasts of the spinal canal membrane. (A) Semi-thin section showing the overall positional relationship of the lateral muscle, spinal canal membrane, spinal cord, and nerve roots. (B) TEM diagram of (A), and the black dotted line shows the thickness of the spinal canal membrane (×2,500). (C, D) High-magnification views of the square in (B). The lateral muscle is closely attached to the spinal canal membrane (→) (×15,000). c1, d1, high-magnification views of the square in (C, D), which show the connection between myocytes and fibrocytes or fibroblasts (×120,000). c2, d2, high-magnification views of the square in c1 and d1. It can be observed that the structure between the myocyte and fibroblast (*) is the myomembrane (→) and basement membrane (△) in turn (×300,000).

4 Discussion

The earliest known vertebrate belongs to Cyclostomata, which first appeared in the Ordovician 450 million years ago. The first major “revolution” in the history of vertebrates was the evolution from jawless to jawed vertebrates, and the primitive Gnathostomata evolved into Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes. Since then, the age of fishes has emerged, diversifying into numerous forms that would eventually give rise to amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. From an evolutionary perspective, studies of vertebrate evolution should begin with basal lineages, such as fishes. Previous studies have confirmed that the outer membrane of the fish spinal cord consists solely of a single meningeal layer of spinal cord membrane (Xie, 2010), but these reports did not address the presence of dural structures. This study revealed that T. rubripes, a teleost fish, possesses a specialized spinal canal membrane structure that completely enclosed the spinal canal. The membrane demonstrated elastic properties under traction, while both the cranial cavity and spinal canal were filled with CSF. The skeletal muscle was closely connected to the spinal canal membrane through some fibrous connective tissues. These fibers established connections with the spinal canal membrane through three distinct morphological patterns: (1) in the form of myocomma (mainly from the lateral muscle), (2) direct epimysial insertions or indirect connections or fused with the spinal canal membrane via reticular or filamentous fibers (mainly from the lateral muscles), and (3) fiber forms at the end of the muscle bundle integrations (mainly from the dorsal fin muscles with minor contributions from the lateral muscles). These fibrous tissues initially appeared on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the spinal canal at 18 dph but became restricted to the bilateral sides of the spinal canal as development progressed.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the CSF velocity of zebrafish increases during physical exercise (Olstad et al., 2019), although the underlying mechanism for this acceleration remains unknown. This study speculated that these fiber connections of T. rubripes may be related to this physiological phenomenon. An observational analysis revealed consistent fibrous connections within each intervertebral space of T. rubripes, especially fibers from the lateral muscle septa on both sides. Coronal sections clearly demonstrated the symmetrical connections between the muscular septum and the spinal canal membrane, potentially reflecting adaptations to the species’ body structure and locomotor patterns. Unlike other vertebrate skeletal systems, fish vertebrae are anatomically classified into thoracic and caudal vertebrae based on morphological characteristics (Xie, 2010). This structural division suggests that cervical vertebrae may represent an unnecessary adaptation for aquatic life. Supporting this observation, studies have documented cervical vertebrae fusion in the finless porpoise, an aquatic mammal, as an adaptive specialization for its life in water (Zheng et al., 2017). In addition, in the muscle system of fish, muscle fibers of myomeres are inserted into myocomma, and adjacent myomere are separated by flaky myocomma. Notably, the number of myomere in fish corresponds to the number of vertebrae in fish (Li et al., 2005). Consequently, the number of connections between myocomma and spinal canal membrane was considered to correspond to the number of myomere and vertebrae. This numerical correlation provides systematic evidence for the existence of these structural connections throughout the entire vertebral column. However, the laminar myocomma could not cover the whole spinal canal membrane. Two additional connection types were observed in the other gaps of the spinal canal membrane: (1) fibers from the epimysium and (2) the end of the muscle bundle. Collectively, these connective fibers with the spinal canal membrane primarily derived from the lateral musculature. The lateral musculature represents the largest axial muscle in fish (Xie, 2010), and the axial muscle provides both structural support and locomotor function in the whole body of vertebrates. During swimming forward, there is alternate contraction of lateral myomeres of the lateral muscle regularly, and the fish body swings left and right along the vertebral axial, constituting the primary propulsion mechanism in teleost fish (Li et al., 2005). It has also been reported that muscle strength can be transmitted through tendons or other connective tissues (not tendons) to bony or tendinous insertion sites (Huijing, 1999), and tension can also be transmitted through myomere (Gemballa and Vogel, 2002). Therefore, this study speculated that during the body swinging of T. rubripes, the contraction of skeletal muscle transmits the tensile force through these fiber connections, and there is pulling of the spinal canal membrane to make it expand locally, generating negative pressure within the spinal canal and thus providing power for CSF. The myocomma-like connections exhibited a fixed, dense morphology within each intervertebral space, suggesting their primary role in tension transmission, and other forms of connection played an auxiliary role. By 18 dph, T. rubripes had developed a mature striated musculature, and the definitive sign of muscle maturity is the formation of multi-nuclear striped myotubes (Goody et al., 2017) at this developmental stage. By 21 dph, a distinct separation between the spinal canal membrane and the spinal cord membrane was observed, which indicated that muscle maturation and the appearance of these fiber connections precede the formation of the spinal membrane. Consequently, these structures might become functionally competent for tension transmission at this stage.

Current understanding of CSF circulation dynamics identifies three primary driving factors: cardiac pulsation (Mestre et al., 2018; Wagshul et al., 2011), respiratory activity, and posture changes (Alperin et al., 2005). Recent researches have revealed an additional mechanism; suboccipital muscle contractions pull the dura mater through MDB fibers, thus creating negative pressure and influencing the CSF circulation dynamics (Zheng et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2021). At present, the MDB complex has been anatomically confirmed in multiple vertebrate species (Hack et al., 1995; Zheng et al., 2017; Okoye et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022), including MDB-like structures in fish and amphibians (Cheng et al., 2025). The results of the connections between muscle and the spinal canal membrane observed in Takifugu rubripes in this study are largely consistent with previous research. However, the connection via reticular fibers observed in Takifugu rubripes in this experiment has not been reported in prior studies, which may be related to differences in fish species and living environments. Fishes, as aquatic vertebrates, exhibit fundamental differences in lifestyle and movement patterns compared to terrestrial vertebrates, particularly upright-walking humans. However, these fiber structures of T. rubripes appear to influence CSF circulation dynamics similarly to the MDB in mammals. These fiber structures were also considered to have many similarities with the MDB structures found in the past; while fish lack true dura mater surrounding the spinal cord (Xie, 2010), these fiber tissues from different sources of T. rubripes converge and integrate with the spinal canal membrane, which was similar to the description that human MDB originated from different muscles and ligaments and migrate along SDM to become a part of it (Jiang et al., 2020). Furthermore, these fiber connections existed in every intervertebral space despite exhibiting differently from what MDB used to think in the neck. Recent studies have found that the dense tendinous MDB originating from the spinalis–semispinalis muscle unit (SSMU) of Gloydius shedaoensis passes through each intervertebral space. Researchers hypothesize that this anatomical arrangement may be related to its functionality, that is, its unique locomotor patterns activate SSMU to transmit tension through MDB and participate in CSF circulation (Li et al., 2022). The existence of MDB in the entire vertebral column has also been mentioned in horses (Vibeke Sødring Elbrønd, 2019). During the development of T. rubripes, the muscle fibers gradually became full and the spinal canal membrane became denser, which was consistent with the development research results of SD rats (Lai et al., 2021). These findings indicated that such fibrous connections may have retained distinct evolutionary characteristics across different branches of the evolutionary tree during the evolution from fish to mammals. These structures had similar anatomical paths in different species: originating from skeletal musculature and terminating either at SDM (Hack et al., 1995; Zheng et al., 2017; Okoye et al., 2018; Dou et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2019; Li et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2020; Scali et al., 2013) or spinal canal membrane through various fibrous specializations. This conserved structure potentially indicates deep evolutionary homology among vertebrate species. Thus, prior to the evolutionary development of cervical vertebrae in fish, these MDB-like fiber structures connected to the spinal canal membrane might play a role similar to MDB in promoting CSF circulation. In the process from fish’s lateral deflection motion to terrestrial vertebrates’ use of limbs to walk, cervical flexibility had been subsequently refined during land adaptation. From broadly distributed MDB-like structures that existed throughout the vertebral column to MDB restricted only to exist in the upper neck, this phylogenetic transition represents an evolutionary adaptation accompanying vertebrates’ shift from aquatic to terrestrial habitats, which might suggest that MDB was an indispensable part in CSF dynamics. As with the most ancestral vertebrate group, the MDB-like structures of fishes may provide crucial insights into the evolutionary origins and ubiquitous existence of the MDB. Future investigations of CSF dynamics should prioritize elucidating the functional significance of MDB.

Beyond its potential role in basic CSF circulation, the discovery of MDB-like structures in T. rubripes invites consideration of their involvement in more complex physiological processes. In mammals, CSF serves as a conduit for volume transmission, distributing neuroendocrine factors such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone to distant brain regions that lack direct innervation but possess corresponding receptors (Caraty and Skinner, 2008). Should similar signaling molecules be present in the CSF of teleosts, the mechanical stimulation of the spinal canal membrane via the MDB-like structures during swimming could theoretically enhance their dispersal. This perspective suggests a potential evolutionary conservation of mechanisms that couple locomotion with neuroendocrine regulation across vertebrates. Nevertheless, affirming this hypothesis requires further investigation, with future research needed to empirically test the functional link between these structural connections and CSF-mediated signaling in fish.

This study provides a foundational morphological description of the MDB-like structures in T. rubripes using post-hatching days as a developmental timeline. A recognized limitation is the lack of direct evidence linking these structures to CSF flow dynamics. Our future work will directly address this by investigating CSF movement patterns during swimming, which will be correlated with both refined morphological staging and the structural details established here, to definitively confirm their physiological role.

5 Conclusion

In T. rubripes, there were three distinct connection types between the musculature and spinal canal membrane, predominantly localized bilaterally within each intervertebral space. These structures appear functionally analogous to MDB structures, potentially serving to transmit mechanical tension and facilitate CSF circulation. In this study, developmental observations revealed that the MDB-like structures appeared by 18 dph in T. rubripes, with tensile force transmission by 21 dph. The coordinated developmental timing of muscle, MDB-like structures, and spinal canal membrane suggests a potential positive correlation. These results provided crucial morphological evidence supporting the evolutionary conservation of MDB architecture across vertebrates and provided foundational data to explore the physiological functions of human MDB.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by The Animal Experimental Center of Dalian Medical University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. W-BJ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Y-YX: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. C-ZS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. H-XL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. J-XS: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. L-LC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. BL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Y-YC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. J-HL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Y-TS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. X-HZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. XS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. GH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. S-BY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. J-FZ: Writing – review & editing. H-JS: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant: NSFC31801008 to Jian-Fei Zhang, NSFC32471192 and Dalian Science and Technology Program 2023RG003 to Hong-Jin Sui).

Acknowledgments

We thank Large Language Models DeepSeek R1 model (https://chat.deepseek.com/) for the language revision of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Author JZ was employed by the company JOINN Laboratories Suzhou Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Alperin N. Hushek S. G. Lee S. H. Sivaramakrishnan A. Lichtor T. (2005). MRI study of cerebral blood flow and CSF flow dynamics in an upright posture: the effect of posture on the intracranial compliance and pressure. Acta Neurochir Suppl.95, 177–181. doi: 10.1007/3-211-32318-x_38

2

Caraty A. Skinner D. C. (2008). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone in third ventricular cerebrospinal fluid: endogenous distribution and exogenous uptake. Endocrinology149, 5227–5234. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1636

3

Chen C. Yu S. B. Chi Y. Y. Tan G. Y. Yan B. C. Zheng N. et al . (2021). Existence and features of the myodural bridge in Gentoo penguins: A morphological study. PloS One16, e0244774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244774

4

Cheng C. Yang H. Song Y. Dong Y. L. Zhang J. Shah M. A.A. et al . (2025). A new analogous organ in bony fishes and amphibians an anatomical structure related with the cerebrospinal fluid circulation. Sci. Rep.15, 5646. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-89599-5

5

Dou Y. R. Zheng N. Gong J. Tang W. Okoye C. S. Zhang Y. et al . (2019). Existence and features of the myodural bridge in Gallus domesticus: indication of its important physiological function. Anat Sci. Int.94, 184–191. doi: 10.1007/s12565-018-00470-2

6

Gai Z. Li Q. Ferron H. G. Keating J. N. Wang J. Donoghue P. C.J. et al . (2022). Galeaspid anatomy and the origin of vertebrate paired appendages. Nature609, 959–963. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04897-6

7

Gao K. Wang Z. Zhou X. Wang H. Kong D. Jiang C. et al . (2017). Comparative transcriptome analysis of fast twitch muscle and slow twitch muscle in Takifugu rubripes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics24, 79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2017.08.002

8

Gemballa S. Vogel F. (2002). Spatial arrangement of white muscle fibers and myoseptal tendons in fishes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol.133, 1013–1037. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00186-1

9

Goody M. F. Carter E. V. Kilroy E. A. Maves L. Henry C. A. (2017). Muscling” Throughout life: integrating studies of muscle development, homeostasis, and disease in zebrafish. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol.124, 197–234. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.11.002

10

Hack G. D. Koritzer R. T. Robinson W. L. Hallgren R. C. Greenman P. E. (1995). Anatomic relation between the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle and the dura mater. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)20, 2484–2486. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199512000-00003

11

Huijing P. A. (1999). Muscle as a collagen fiber reinforced composite: a review of force transmission in muscle and whole limb. J. Biomech32, 329–345. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00186-9

12

Jiang W. B. Zhang Z. H. Yu S. B. Sun J. X. Ding S. W. Ma G. J. et al . (2020). Scanning electron microscopic observation of myodural bridge in the human suboccipital region. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)45, E1296–E1301. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003602

13

Kai W. Kikuchi K. Tohari S. Chew A. K. Tay A. Fujiwara A. et al . (2011). Integration of the genetic map and genome assembly of fugu facilitates insights into distinct features of genome evolution in teleosts and mammals. Genome Biol. Evol.3, 424–442. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr041

14

Lai H. X. Zhang J. F. Song T. W. Liu B. Tang W. Sun S. Z. et al . (2021). Development of myodural bridge located within the atlanto-occipital interspace of rats. Anat Rec (Hoboken)304, 1541–1550. doi: 10.1002/ar.24568

15

Li S. A. Gao M. Hou J. H. Li S. H. Wang L. Z. (2005). “ Comparative anatomy of lateral muscles in six species of fish,” in Collection of Symposium of the Zoological Society of China in Seven Northern Provinces and Cities, Vol. 51. Tianjin, China: Tianjin Normal University.569–581.

16

Li C. Yue C. Yan B. Bi H. T. Wang H. Gong J. et al . (2022). Identification of the myodural bridge in a venomous snake, the gloydius shedaoensis: what is the functional significance? Int. J. Morphology40, 304–313. doi: 10.4067/S0717-95022022000200304

17

McClelland G. B. (2012). Muscle remodeling and the exercise physiology of fish. Exerc Sport Sci. Rev.40, 165–173. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3182571e2c

18

Mestre H. Tithof J. Du T. Song W. Peng W. Sweeney A. M. et al . (2018). Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat. Commun.9, 4878. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07318-3

19

Okoye C. S. Zheng N. Yu S. B. Sui H. J. (2018). The myodural bridge in the common rock pigeon (Columbia livia): Morphology and possible physiological implications. J. Morphol279, 1524–1531. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20890

20

Olstad E. W. Ringers C. Hansen J. N. Adinda Wens A. Brandt C. Wachten D. et al . (2019). Ciliary beating compartmentalizes cerebrospinal fluid flow in the brain and regulates ventricular development. Curr. Biol.29, 229–241.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.059

21

Sakka L. Coll G. Chazal J. (2011). Anatomy and physiology of cerebrospinal fluid. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngology Head Neck Dis.128, 309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2011.03.002

22

Scali F. Pontell M. E. Enix D. E. Marshall E. (2013). Histological analysis of the rectus capitis posterior major’s myodural bridge. Spine J.13, 558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.01.015

23

Vibeke Sødring Elbrønd R. M. S. (2019). Equine myodural bridges, An Anatomical, integrative and functional description of myodural bridges along the spine of horses: Special focus on the atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial regions. Med. Res. Arch.7. doi: 10.18103/mra.v7i11.2005

24

Vinje V. Ringstad G. Lindstrom E. K. Valnes L. M. Rognes M. E. Eide P. K. et al . (2019). Respiratory influence on cerebrospinal fluid flow - a computational study based on long-term intracranial pressure measurements. Sci. Rep.9, 9732. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46055-5

25

Wagshul M. E. Eide P. K. Madsen J. R. (2011). The pulsating brain: A review of experimental and clinical studies of intracranial pulsatility. Fluids Barriers CNS8, 5. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-8-5

26

Xie C. X. (2010). Ichthyology (Beijing: China Agriculture Press).

27

Xu Q. Shao C. X. Zhang Y. Zhang Y. Liu C. Chen Y. X. et al . (2021). Head-nodding: a driving force for the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid. Sci. Rep.11, 14233. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93767-8

28

Xu Q. Yu S. B. Zheng N. Yuan X. Y. Chi Y. Y. Liu C. et al . (2016). Head movement, an important contributor to human cerebrospinal fluid circulation. Sci. Rep.6, 31787. doi: 10.1038/srep31787

29

Zhang J. H. Tang W. Zhang Z. X. Luan B. Y. Yu S. B. Sui H. J. (2016). Connection of the posterior occipital muscle and dura mater of the siamese crocodile. Anat Rec (Hoboken)299, 1402–1408. doi: 10.1002/ar.23445

30

Zhao H. F. Zhang X. Sui J. Y. Zhao Q. Q. Yuan X. Y. Li C. et al . (2019). Existence of Myodural Bridge in the Trachemys scripta elegans: Indication of its Important Physiological Function. Int. J. Morphology37, 1353–1360. doi: 10.4067/S0717-95022019000401353

31

Zheng N. Yuan X. Y. Chi Y. Y. Liu P. Wang B. Sui J. Y. et al . (2017). The universal existence of myodural bridge in mammals: an indication of a necessary function. Sci. Rep.7, 8248. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06863-z

32

Zheng N. Yuan X. Y. Li Y. F. Chi Y. Y. Gao H. B. Zhao X. et al . (2014). Definition of the to be named ligament and vertebrodural ligament and their possible effects on the circulation of CSF. PloS One9, e103451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103451

Summary

Keywords

myodural bridge, T. rubripes , cerebrospinal fluid, development, spinal canal meningioma

Citation

Song Y, Jiang W-B, Xiong Y-Y, Shi C-Z, Lai H-X, Sun J-X, Chen L-L, Liu B, Chi Y-Y, Li J-H, Sun Y-T, Zhang X-H, Zhang J, Song X, Gong J, Hack GD, Yu S-B, Zhang J-F and Sui H-J (2025) The connection between skeletal muscle and spinal canal membrane of Takifugu rubripes and its anatomical and physiological significance. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1656098. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1656098

Received

29 June 2025

Accepted

27 October 2025

Published

17 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Khaled Mohammed Geba, Menoufia University, Egypt

Reviewed by

Sofia Priyadarsani Das, National Taiwan Ocean University, Taiwan

Gustavo M Somoza, Instituto Tecnológico de Chascomús (CONICET-UNSAM), Argentina

Hongwei Yan, Dalian Ocean University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Song, Jiang, Xiong, Shi, Lai, Sun, Chen, Liu, Chi, Li, Sun, Zhang, Zhang, Song, Gong, Hack, Yu, Zhang and Sui.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jian-Fei Zhang, zjfdlmedu@163.com; Hong-Jin Sui, suihj@hotmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.