- 1Norwegian Polar Institute, Fram Centre, Tromsø, Norway

- 2Department of Ecological Chemistry, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany

- 3UMR Littoral, Environment and Societies (CNRS–University of La Rochelle), Institut du Littoral et de l’Environnement, La Rochelle, France

- 4Hanse-Wissenschaftskolleg – Institute for Advanced Study, Delmenhorst, Germany

Studies of Arctic food-web structure and function by means of carbon isotopic composition (δ13C) of fatty acids (FAs) have a main challenge of identifying a proper baseline for pelagic particulate organic matter (PPOM). To assess variations in δ13C values of the FAs 16:1(n-7), 20:5(n-3) and 22:6(n-3) in PPOM, seawater was collected along a latitudinal sea-ice gradient across the Barents Sea in August 2019, spanning ice-free to fully ice-covered stations. δ13C values varied strongly along the sampling transect in all three FAs (16:1(n-7): -32.2 to -28.9 ‰, 20:5(n-3): -37.4 to -29.8 ‰, 22:6(n-3): -34.7 to -29.3 ‰) and, independently of the FA, were consistently higher at ice-covered (δ13C: -30.2 ± 1.1 ‰) vs. ice-free stations (δ13C: -33.8 ± 2.2 ‰). This was likely the result of the contribution of ice-associated algae to PPOM due to ice melt as ice algae often have higher δ13C values than pelagic algae. Latitudinal differences in δ13C values of 20:5(n-3) and 22:6(n-3) displayed a similar trend, which partly differed from 16:1(n-7). This was likely related to differences in FA synthesis pathways and cellular functions between the membrane-associated FAs 20:5(n-3) and 22:6(n-3) and the storage FA 16:1(n-7). The δ13C values presented here are intended to support future food-web studies applying stable isotope mixing models to quantify carbon sources in the polar marine environment.

1 Introduction

The northern Barents Sea is a highly productive Arctic shelf system, which supports large stocks of commercially important fish, but is threatened by global warming (Ingvaldsen et al., 2025). Due to its ecological significance, improved knowledge on current trophic linkages and the energy flow within Barents Sea food webs is crucial to better forecast future changes in marine ecosystem structure and functioning (e.g., Årthun et al., 2025). Pelagic and sympagic (i.e., ice-associated) particulate organic matter (POM) are the primary food sources in polar pelagic food webs, with varying contributions depending on season and region (Budge et al., 2008; Koch et al., 2023). Sympagic algae have been shown to represent a crucial food source for zooplankton and, indirectly, for fish in the central Arctic Ocean (Kohlbach et al., 2016, 2017) and Bering Sea (Wang et al., 2015), whereas pelagic algae can be the major food source fueling food webs in seasonally ice-covered regions such as the Barents Sea (Kohlbach et al., 2023b, 2024).

Carbon stable isotope compositions (δ13C) are commonly used to distinguish the origin of POM (i.e., pelagic or sympagic) and to trace this organic matter from production to consumption across multiple trophic levels (Kunisch et al., 2021; Kohlbach et al., 2023b). Thus, isotopic compositions of pelagic and sympagic POM are crucial for the accurate quantification of flows of organic matter via stable isotope mixing models (Stock et al., 2018). Traditionally, biological samples are considered as a whole and their entire carbon content is investigated via bulk stable isotope analysis (BSIA; Søreide et al., 2013) as pelagic or sympagic algae can be well separated based on their δ13C values (Søreide et al., 2006). Data interpretations from bulk measurements, however, have limitations related to trophic fractionation, the routing of organic matter, and because the origin of different sources in mixtures cannot be determined (e.g., origin of microalgae in pelagic POM [PPOM]). Complementary to the determination of isotopic compositions, fatty acids (FAs) can be used as trophic markers as some FAs are specific for certain groups of primary producers (e.g., diatoms, flagellates and bacteria [Dalsgaard et al., 2003]). Comprehensive understanding of food-web functioning therefore often requires the use of a combination of several trophic markers (Lebreton et al., 2011). Compound-specific stable isotope analysis (CSIA) of FAs offers an additional approach, integrating the strengths of FA trophic markers and BSIA (Kohlbach et al., 2016; Desforges et al., 2022). CSIA can provide information on the composition of organic matter produced by specific algal groups at a high taxonomic resolution (i.e., δ13C values of diatom- and flagellate-associated FAs) as well as their fate in food webs. In addition, FAs are minimally modified during metabolic processes (i.e., negligible trophic fractionation), so their isotopic compositions remain largely unaltered across trophic levels, making these molecules valuable trophic markers (Dalsgaard et al., 2003; Bergé and Barnathan, 2005).

In polar ecosystems, carbon isotopic compositions of primary producers—making up mixtures like PPOM—can vary substantially at broad temporal and spatial scales (de la Vega et al., 2019). It is therefore important to rely on source δ13C values specific to a season and a region to precisely quantify organic matter fluxes. However, literature on FA-specific δ13C values in PPOM is limited and geographically restricted so far (e.g., Wang et al., 2014; Kohlbach et al., 2016).

Here, we present FA-specific δ13C values of PPOM collected along a latitudinal transect with ice-free and ice-covered sampling stations across the northwestern Barents Sea during August 2019. Our aim was to determine how isotopic compositions of FAs in PPOM change over this gradient, and to compare this to pre-existing data, in order to define some trends linked to differences in environmental parameters as well as FA synthesis pathways and cellular function. Based on this preliminary dataset, we provide recommendations for research foci of future isotope-based ecosystem studies.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling

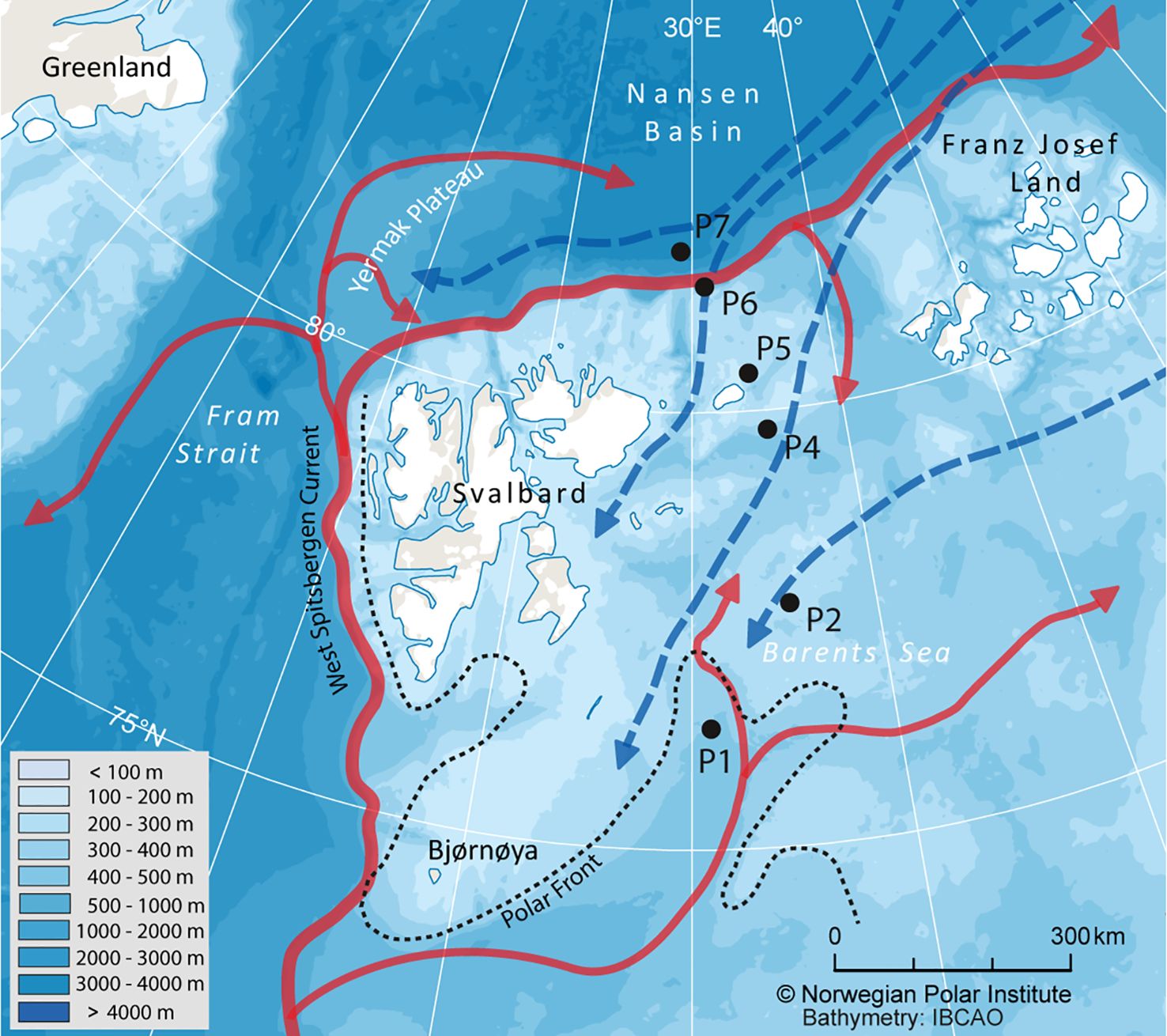

PPOM was collected between 8th and 21st of August 2019 at six process (P) stations (P1, P2, P4, P5, P6, P7) along a northward transect in the northwestern Barents Sea as part of the Nansen Legacy project (arvenetternansen.com; Figure 1). This transect covered a latitudinal gradient from ca. 76 to 82° N, from the Barents Sea shelf across the shelf break into the deep Nansen Basin. Located south of the Polar Front, station P1 was dominated by Atlantic water, whereas the surface waters of the other stations were influenced by Arctic water masses (Kohlbach et al., 2023a). At the time of sampling, stations P1 and P2 were ice-free, whereas the ice edge was located close to station P4, at ca. 79.75° N and 34°E, and stations P5 to P7 were ice-covered. Ice concentration increased from 60% to 90% from stations P4 to P7. More details on environmental conditions can be found in Kohlbach et al. (2023a). Seawater was sampled at the depth of maximum chlorophyll a concentration (14 to 73 m) using Niskin bottles attached to a CTD rosette. Seawater volumes of 1.2 to 2.5 L were filtered through pre-combusted (3 h, 550°C) 47 mm Whatman® GF/F filters using a vacuum pump (-20 kPA). Until further processing, filters were stored at -80°C.

Figure 1. Sampling area in the northern Barents Sea indicating the main pathways of Atlantic (red arrows) and Arctic water masses (blue arrows).

2.2 Determination of PPOM FA-specific isotopic compositions

Carbon isotopic composition was determined in the FAs 16:1(n-7) and 20:5(n-3), predominantly synthesized by diatoms, and FA 22:6(n-3), mostly found in dinoflagellates and other flagellates (e.g., Phaeocystis; Dalsgaard et al., 2003 and references therein). These FAs can have different physiological functions, with 16:1(n-7) often used for energy storage (Morales et al., 2021) and the polyunsaturated FAs (PUFAs) 20:5(n-3) as well as 22:6(n-3) being important components of cell membranes (Harwood, 1998). FAs were extracted after Folch et al. (1957) using dichloromethane/methanol (2:1, v/v) and converted into fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) using methanol (containing 3% concentrated sulfuric acid). FA proportions are presented in Supplementary Table 1; FA profiles of PPOM are discussed in an ecological context in Kohlbach et al. (2021). Subsequent isotopic analyses were done at the stable isotope facility of the joint research unit LIENSs (CNRS – University of La Rochelle), France (see details in Kohlbach et al., 2023b). Isotopic compositions are reported in per mil (‰) using the delta (δ) notation and are normalized using Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) as a reference material. To consider a potential drift during the analysis of each sample batch, raw data were corrected and normalized with an internal standard (23:0, Sigma Aldrich) calibrated in EA-IRMS (mean: -32.39 ‰, standard deviation: 0.02 ‰, n = 5) as recommended in Dunn and Carter (2018). Reference materials used for the calibration of the EA-IRMS were USGS-61 and USGS-63. δ13C values (mean ± standard deviation) of the internal standard 23:0 added during lipid extraction were -32.85 ± 0.40 ‰ (n = 18). One replicate per station was analyzed, thus limiting statistical analyses, but this replicate is representative of the water at the sampling location as a large amount was filtered (see 2.1).

3 Results and discussion

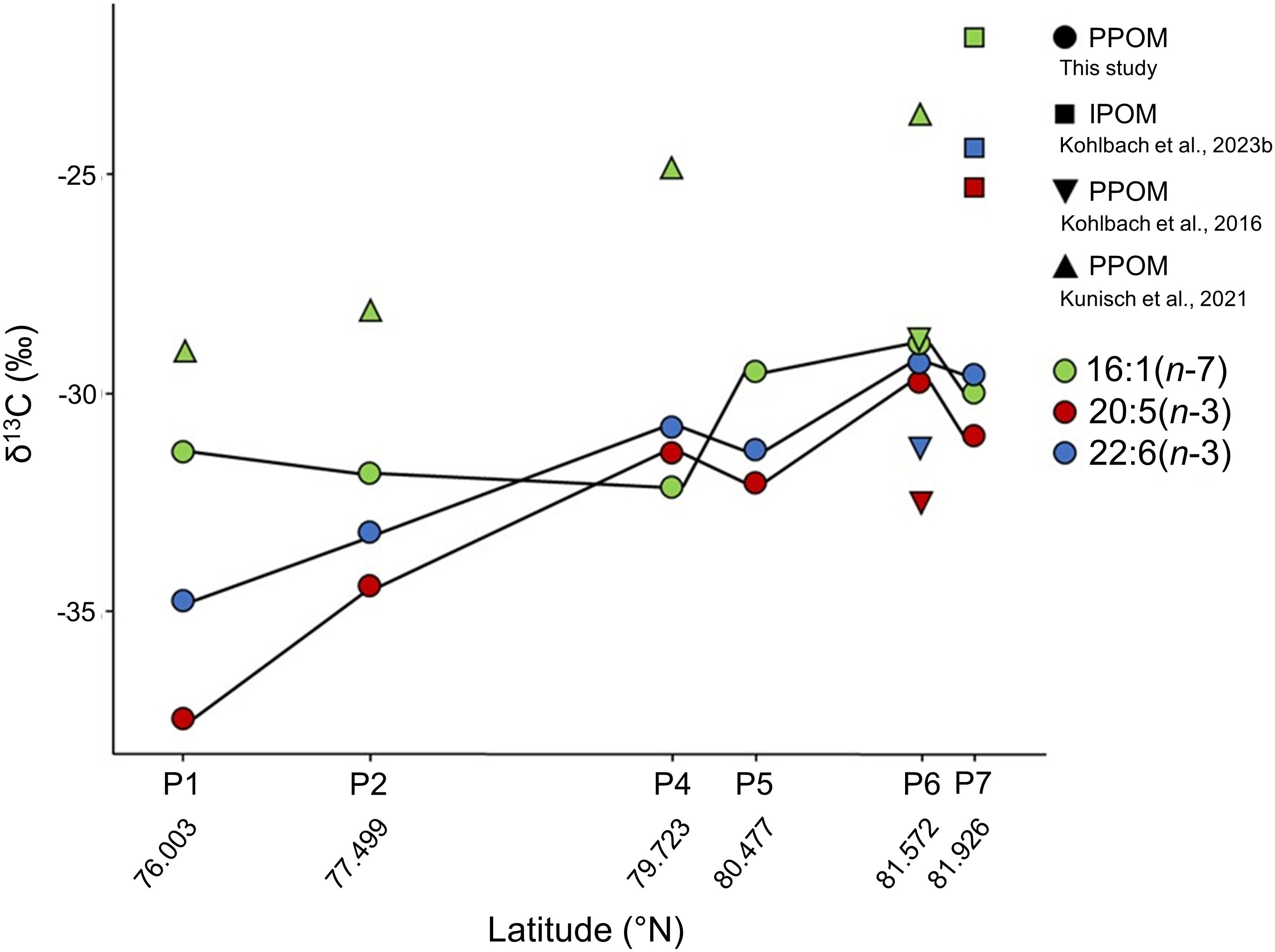

PPOM FA-specific δ13C values displayed some noteworthy variations at both spatial and temporal scales (Figure 2): Along the sampling transect, δ13C values of 16:1(n-7), 20:5(n-3) and 22:6(n-3) varied from -32.2 to -28.9 ‰, -37.4 to -29.8 ‰ and -34.7 to -29.3 ‰, respectively. Differences were also evident across sampling years and months, with 16:1(n-7) being considerably more δ13C-enriched in a study from June 2017 (Kunisch et al., 2021) than in August 2019 (present study; Figure 2). When unaccounted for, these spatial and temporal variations of several ‰ could severely alter data interpretation in food-web studies relying on FA-specific δ13C values. This emphasizes the importance of studying potential food sources (i.e., pelagic and sympagic algae in our case) and consumers from the same location and same time period while accounting for potentially varying species-specific turnover rates of FAs in the consumers.

Figure 2. Carbon stable isotope compositions (δ13C) of the fatty acids 16:1(n-7), 20:5(n-3) and 22:6(n-3) in pelagic particulate organic matter (PPOM) collected at stations P1 to P7 in the Barents Sea. Data from other studies have been added for comparisons: Ice-associated particulate organic matter (IPOM) collected at station P7 during the same sampling campaign (Kohlbach et al., 2023b), PPOM collected in August 2012 close to station P6 (station 209; Kohlbach et al., 2016), and PPOM collected in June 2017 close to stations P1, P2, P4 and P6/P7 (stations 44, 47, 48, and 50, respectively; Kunisch et al., 2021). The plot was created in Software R, version 4.1.0 (R Core Team, 2021), using the package ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016).

Variations in FA isotopic compositions can be related to a multitude of biotic and abiotic factors, some of them relatively well known and others not well studied or documented (e.g., Wang et al., 2014; de la Vega et al., 2019). Although differences in PPOM FA-isotopic compositions were observed, the limited size of our dataset prevents us from offering definitive explanations; instead, we aim to suggest potential influencing factors in the following discussion.

3.1 Influence of sea-ice melt

The δ13C values of all three FAs were higher at the ice-covered stations (P5 to P7: -30.2 ± 1.1 ‰) compared to the ice-free stations (P1 and P2: -33.8 ± 2.2 ‰; Wilcoxon test, W = 2, p = 0.002). This was likely a consequence of sea-ice melt, indicated by the lower surface water salinity at the ice-covered compared to the ice-free stations, and the large contribution of ice-associated diatoms, such as Shionodiscus bioculatus, to the pelagic protist communities at the ice-covered stations (Kohlbach et al., 2023a). Ice-associated algae have often higher δ13C values than pelagic algae (Figure 2: station P7), i.e., up to 7 ‰ (Wang et al., 2015; Kohlbach et al., 2016; de la Vega et al., 2019; Kunisch et al., 2021) due to the limitation in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) availability in sea ice in comparison to the water column (Thomas and Papadimitriou, 2011). Thus, enhanced input of sympagic algae to PPOM at ice-covered vs. ice-free stations was likely a major driver of PPOM δ13C composition.

3.2 Influence of FA synthesis pathways and cellular function

At most sampling stations (except P4 and P7, where differences between FA δ13C values were minor), the monounsaturated FA 16:1(n-7) was more δ13C-enriched than the two PUFAs 20:5(n-3) and 22:6(n-3). Similarly, 16:1(n-7) was more δ13C-enriched than the PUFAs in IPOM at P7 (Figure 2).

Both 16:1(n-7) and 20:5(n-3) are considered to be typical diatom-produced FAs; however, the differences in their δ13C values point to a different driver than the taxa-specific influence on isotopic fractionation. Without being exhaustive, this difference may be related to several factors including:

1. The metabolic reactions involved in FA biosynthesis: Different de novo production pathways may affect FA δ13C values. Indeed, 16:1(n-7) derives directly from the saturated FA 16:0, while the long-chain PUFAs derive from FA 18:0, and their synthesis requires multiple enzymatic steps, including desaturation and elongation (Sprecher, 2000; Leonard et al., 2004; Baird, 2022). As suggested by Wang et al. (2014), the activity of desaturase enzymes (to introduce unsaturation) and of elongation enzymes (to add carbon atoms) may affect FA isotopic compositions.

2. The origin of the carbon used in FA biosynthesis: FAs synthesized during different stages of algae growth (e.g., early bloom, late season; Falk-Petersen et al., 1998) may incorporate DIC with varying δ13C values (de la Vega et al., 2019).

3. The functions of these FAs in the cells: While 16:1(n-7) is a FA typically used for energy storage and accumulated under unfavorable growth conditions (Morales et al., 2021), the two PUFAs are utilized for biomembrane stabilization (Harwood, 1998). During the time of sampling in August, the Barents Sea phytoplankton was in a late-bloom stage (Kohlbach et al., 2023a). The phytoplankton FA production was likely dominated by the synthesis of storage rather than membrane FAs reflecting strong seasonal variation, driven by the availability of nutrients and light (Falk-Petersen et al., 1998).

Of these potential explanations, the first is likely the best candidate as metabolic pathways are probably relatively similar between pelagic and sympagic algae, whereas the timing of their life cycles—involved in explanations 2 and 3—differs considerably. However, our limited dataset makes it difficult to identify the main factors influencing the isotopic compositions, warranting further investigation combining observations from the field—e.g., changes with season and region and variations within additional FAs— and experimental approaches to finely determine synthesis pathways and fractionation factors associated with each step during biosynthesis (Remize et al., 2020, 2021).

Interestingly, despite the fact that the two PUFAs are produced by different algal taxa, i.e., 20:5(n-3) predominantly by diatoms and 22:6(n-3) predominantly by (dino)flagellates/Phaeocystis (Dalsgaard et al., 2003), the δ13C values of 20:5(n-3) and 22:6(n-3) followed a very similar trend over the latitudinal gradient, with 20:5(n-3) being always more δ13C-depleted than 22:6(n-3). A similar pattern (i.e., lower δ13C values in 20:5(n-3)) was observed in the IPOM at P7 and the PPOM collected in August 2012 close to P6. As previously described (e.g., Sprecher, 2000; Baird, 2022), the PUFAs are both synthesized from FA 18:0 as a precursor, with 22:6(n-3) being eventually synthesized from 20:5(n-3) through elongation of its chain into 22:5(n-3) and then desaturation at the 4th carbon of the chain. The difference of δ13C values between 20:5(n-3) and 22:6(n-3), which ranged from 0.4 ‰ at station P6 to 2.7 ‰ at station P1, therefore likely corresponds to the isotopic fractionation issued after the combination of these two biochemical pathways. This likely reflects the distinct carbon fixation mechanisms in diatoms and dinoflagellates leading to unique isotopic fractionation even with similar PUFA biosynthetic pathways. Our preliminary results stress the need to better assess the processes involved in isotopic fractionation during biochemical reactions, in order to provide precise estimations of fractionation factors for each enzymatic reaction. Such estimations at the molecular scale would allow to holistically understand which processes lead to isotopic fractionation at the individual scale, but also at the scale of food webs, providing more robust estimates of organic matter fluxes in complex marine food webs. Ultimately, these molecular-level fractionation factors should be collected and summarized in review articles and databases, as has been done previously at the level of species or functional groups (Vander Zanden and Rasmussen, 2001; Stephens et al., 2023).

4 Conclusions

Carbon isotopic compositions of PPOM FAs varied markedly across latitudinal gradients, which could have strong implications for data interpretation in food-web studies. Such variations were found to be linked to varying molecular structure (monounsaturated vs. polyunsaturated FAs) and cellular function (storage vs. membrane FAs) as well as to differences in the contribution of ice-associated algae to the PPOM pool depending on ice-melt stage. Given the complexity underlying the observed variability and trends, further in-depth studies are needed to investigate the mechanistic processes leading to differences in FA isotopic compositions—such as fractionation mechanisms in chemical reactions and synthesis pathways—while also accounting for seasonal dynamics (i.e., elevated production of storage or membrane FAs during certain periods of the year).

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: The isotopic data is available at the Norwegian Polar Data Centre (https://data.npolar.no/, https://doi.org/10.21334/npolar.2023.d8e07ee1).

Author contributions

DK: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Data curation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Methodology. BL: Visualization, Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. GG: Resources, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Data curation. AW: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. HH: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. MG: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision. PA: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Data curation, Methodology, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Research Council of Norway through the project The Nansen Legacy (RCN # 276730). DK is currently funded by the German Helmholtz Association Initiative and Networking Fund (Helmholtz Young Investigator Group Double-Trouble, VH-NG-20-09). BL was supported by a Fellowship from the Hanse Wissenschaftskolleg Institute for Advanced Study, Delmenhorst, Germany. PA was supported by the Centre for ice, Cryosphere, Carbon and Climate (iC3) through the Centre of Excellence funding scheme by the Research Council of Norway (grant no. 332635).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the captain and the crew of RV Kronprins Haakon for their excellent support at sea during the Nansen Legacy seasonal cruise Q3. We further thank Sinah Müller, Valeria Adrian (AWI), and Angela Stippkugel (NTNU) for their help with the lipid laboratory analyses. We are grateful for the valuable comments received from the two reviewers during the review process.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1656212/full#supplementary-material

References

Årthun M., Dinh K. V., Dörr J., Dupont N., Frasner F., Nilsen I., et al. (2025). The future Barents Sea—A synthesis of physical, biogeochemical, and ecological changes toward 2050 and 2100. Elem. Sci. Anth 13, 46. doi: 10.1525/elementa.2024.00046

Baird P. (2022). Diatoms and fatty acid production in Arctic and estuarine ecosystems a reassessment of marine food webs, with a focus on the timing of shorebird migration. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 688, 173–196. doi: 10.3354/meps14025

Bergé J. P. and Barnathan G. (2005). “Fatty acids from lipids of marine organisms: molecular biodiversity, roles as biomarkers, biologically active compounds, and economical aspects,” in Marine Biotechnology I. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology, vol. 96 . Eds. Ulber R. and Le Gal Y. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg). doi: 10.1007/b135782

Budge S. M., Wooller M. J., Springer A. M., Iverson S. J., McRoy C. P., and Divoky G. J. (2008). Tracing carbon flow in an arctic marine food web using fatty acid-stable isotope analysis. Oecologia 157, 117–129. doi: 10.1007/s00442-008-1053-7

Dalsgaard J., St John M., Kattner G., Müller-Navarra D., and Hagen W. (2003). Fatty acid trophic markers in the pelagic marine environment. Adv. Mar. Biol. 46, 225–237. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2881(03)46005-7

de la Vega C., Jeffreys R. M., Tuerena R., Ganeshram R., and Mahaffey C. (2019). Temporal and spatial trends in marine carbon isotopes in the Arctic Ocean and implications for food web studies. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 4116–4130. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14832

Desforges J.-P., Kohlbach D., Carlyle C., Michel C., Loseto L., Rosenberg B., et al. (2022). Multi-dietary tracer approach reveals little overlap in foraging ecology between seasonally sympatric ringed and harp seals in the high Arctic. Front. Mar. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.969327

Dunn P. J. H. and Carter J. F. (2018). Good practice guide for isotope ratio mass spectrometry. 2nd Edition (Group of the Forensic Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry Network), ISBN: 978-0-948926-33-4.

Falk-Petersen S., Sargent J., Henderson J. R., Hegseth E. N., Hop H., and Okolodkov Y. B. (1998). Lipids and fatty acids in ice algae and phytoplankton from the Marginal Ice Zone in the Barents Sea. Polar Biol. 20, 41–47. doi: 10.1007/s003000050274

Folch J., Lees M., and Stanley G. H. S. (1957). A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64849-5

Harwood J. L. (1998). “Membrane lipids in algae,” in Lipids in photosynthesis: structure, function genetics. Eds. Siegenthaler P.-A. and Muarata N. (Springer Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 53–64.

Ingvaldsen R. B., Bratbak G., Planque B., and Søreide J. E. (2025). Food web structure, functions, drivers, and dynamics in the Barents Sea and adjacent seas. Prog. Oceanogr 233, 103454. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2025.103454

Koch C. W., Brown T. A., Amiraux R., Ruiz-Gonzalez C., MacCorquodale M., Yunda-Guarin G. A., et al. (2023). Year-round utilization of sea ice-associated carbon in Arctic ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 14, 1964. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37612-8

Kohlbach D., Goraguer L., Bodur Y. V., Müller O., Amargant-Arumí M., Blix K., et al. (2023a). Earlier sea-ice melt extends the oligotrophic summer period in the Barents Sea with low algal biomass and associated low vertical flux. Prog. Oceanogr 213, 103018. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2023.103018

Kohlbach D., Graeve M., Lange B., David C., Peeken I., and Flores H. (2016). The importance of ice algae-produced carbon in the central Arctic Ocean ecosystem: Food web relationships revealed by lipid and stable isotope analyses. Limnol. Oceanogr 61, 2027–2044. doi: 10.1002/lno.10351

Kohlbach D., Hop H., Wold A., Schmidt K., Smik L., Belt S. T., et al. (2021). Multiple trophic markers trace dietary carbon sources in Barents Sea zooplankton during late summer. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.610248

Kohlbach D., Hop H., Wold A., Schmidt K., Smik L., Belt S. T., et al. (2024). Ice algae as supplementary food rather than major energy source for the Barents Sea zooplankton community. Prog. Oceanogr. 229, 103368. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2024.103368

Kohlbach D., Lebreton B., Guillou G., Wold A., Hop H., Graeve M., et al. (2023b). Dependency of Arctic zooplankton on pelagic food sources: new insights from fatty acid and stable isotope analyses. Limnol. Oceanogr. 68, 2346–2358. doi: 10.1002/lno.12423

Kohlbach D., Schaafsma F. L., Graeve M., Lebreton B., Lange B. A., David C., et al. (2017). Strong linkage of polar cod (Boreogadus saida) to sea ice algae-produced carbon: evidence from stomach content, fatty acid and stable isotope analyses. Prog. Oceanogr. 152, 62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2017.02.003

Kunisch E., Graeve M., Gradinger R., Haug T., Kovacs K. M., Lydersen C., et al. (2021). Ice-algal carbon supports harp and ringed seal diets in the European Arctic: evidence from fatty acid and stable isotope markers. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 675, 181–197. doi: 10.3354/meps13834

Lebreton B., Richard P., Galois R., Radenac G., Pfléger C., Guillou G., et al. (2011). Trophic importance of diatoms in an intertidal Zostera noltii seagrass bed: Evidence from stable isotope and fatty acid analyses. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 92, 140–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2010.12.027

Leonard A. E., Pereira S. L., Sprecher H., and Huang Y.-S. (2004). Elongation of long-chain fatty acids. Prog. Lipid Res. 43, 36–54. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(03)00040-7

Morales M., Aflalo C., and Bernard O. (2021). Microalgal lipids: A review of lipids potential and quantification for 95 phytoplankton species. Biomass Bioenergy 150, 106108. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2021.106108

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available online at: http://www.r-project.org (Accessed March 19, 2023).

Remize M., Planchon F., Garnier M., Loh A. N., Le Grand F., Bideau A., et al. (2021). A 13CO2 enrichment experiment to study the synthesis pathways of polyunsaturated fatty acids of the Haptophyte Tisochrysis lutea. Mar. Drugs 20, 22. doi: 10.3390/md20010022

Remize M., Planchon F., Loh A. N., Le Grand F., Bideau A., Le Goic N., et al. (2020). Study of synthesis pathways of the essential polyunsaturated fatty acid 20:5n-3 in the diatom Chaetoceros muelleri using 13C-isotope labeling. Biomolecules 10, 797. doi: 10.3390/biom10050797

Søreide J. E., Carroll M. L., Hop H., Ambrose W.G. Jr, Hegseth E. N., and Falk-Petersen S. (2013). Sympagic-pelagic-benthic coupling in Arctic and Atlantic waters around Svalbard revealed by stable isotopic and fatty acid tracers. Mar. Biol. Res. 9, 831–850. doi: 10.1080/17451000.2013.775457

Søreide J. E., Hop H., Carroll M. L., Falk-Petersen S., and Hegseth E. N. (2006). Seasonal food web structures and sympagic-pelagic coupling in the European Arctic revealed by stable isotopes and a two-source food web model. Prog. Oceanogr. 71, 59–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2006.06.001

Sprecher H. (2000). Metabolism of highly unsaturated n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1486, 219–231. doi: 10.1016/S1388-1981(00)00077-9

Stephens R. B., Shipley O. N., and Moll R. J. (2023). Meta-analysis and critical review of trophic discrimination factors (Δ13C and Δ15N): Importance of tissue, trophic level and diet source. Funct. Ecol. 37, 2535–2548. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.14403

Stock B. C., Jackson A. L., Ward E. J., Parnell A. C., Phillips D. L., and Semmens B. X. (2018). Analyzing mixing systems using a new generation of Bayesian tracer mixing models. PeerJ 6, e5096. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5096

Thomas D. and Papadimitriou S. (2011). “Biogeochemistry of sea ice,” in Encyclopedia of snow, ice and glaciers. Eds. Singh V. P. and Haritashya U. K. (Springer, Dordrecht, the Netherlands), 98–102.

Vander Zanden M. J. and Rasmussen J. B. (2001). Variation in δ15N and δ13C trophic fractionation: implications for aquatic food web studies. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 2061–2066. doi: 10.4319/lo.2001.46.8.2061

Wang S. W., Budge S. M., Gradinger R. R., Iken K., and Wooller M. J. (2014). Fatty acid and stable isotope characteristics of sea ice and pelagic particulate organic matter in the Bering Sea: tools for estimating sea ice algal contribution to Arctic food web production. Oecologia 174, 699–712. doi: 10.1007/s00442-013-2832-3

Wang S. W., Budge S. M., Iken K., Gradinger R. R., Springer A. M., and Wooller M. J. (2015). Importance of sympagic production to Bering Sea zooplankton as revealed from fatty acid-carbon stable isotope analyses. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 518, 31–50. doi: 10.3354/meps

Keywords: Arctic Ocean, carbon isotopic composition of fatty acids, particulate organic matter, sea ice, fatty acid synthesis

Citation: Kohlbach D, Guillou G, Wold A, Hop H, Graeve M, Assmy P and Lebreton B (2025) Variations in carbon isotopic composition of fatty acids in Arctic pelagic particulate organic matter: a preliminary assessment over a latitudinal gradient. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1656212. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1656212

Received: 29 June 2025; Accepted: 14 November 2025; Revised: 05 November 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Jinlin Liu, Tongji University, ChinaReviewed by:

Ashok Jagtap, Ministry of Earth Sciences, IndiaBiswajit Roy, Ministry of Earth Sciences, India

Copyright © 2025 Kohlbach, Guillou, Wold, Hop, Graeve, Assmy and Lebreton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Doreen Kohlbach, ZC5rb2hsYmFjaEBnb29nbGVtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Benoit Lebreton, YmVub2l0LmxlYnJldG9uQHVuaXYtbHIuZnI=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Doreen Kohlbach

Doreen Kohlbach Gaёl Guillou3

Gaёl Guillou3 Anette Wold

Anette Wold Haakon Hop

Haakon Hop Martin Graeve

Martin Graeve Philipp Assmy

Philipp Assmy Benoit Lebreton

Benoit Lebreton