Abstract

The protection and development of World Heritage Sites are of great significance for inheriting human civilization, and it is crucial to maintain and enhance their brand quality. Located in a coastal area, the Levuka Historical Port Town currently faces issues such as damage of world heritage and lagging overall development. From the perspective of marine spatial planning, this paper analyzes the conflicts and synergies between land and sea uses, formulates corresponding compatibility rules, and takes blocks as basic units to measure the compatibility and functional optimization strategies between various activities, exploring effective means of achieving comprehensive protection and revitalization of world heritage. The results show that the Levuka Historical Port Town has a good overall compatibility between land and sea uses, but its land use mixing degree is low, with great potential for revitalization. Using marine spatial planning, the Levuka Historical Port Town is divided into a protection zone, an optimization zone, a function expansion zone and a function integration zone. it is necessary to reasonably control activities that threaten relics, promote activities conducive to the development of relics, moderately introduce other functions, increase the vitality of World Heritage Sites, and promote sustainable development of world heritage.

1 Introduction

With the growing number of world heritage sites, World Heritage Sites around the world are threatened by human activities, environmental changes, natural disasters, and the limited effectiveness of conservation efforts (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2020). Some World Heritage Sites are poorly integrated with social development and require urgent conservation measures, to improve their long-term effectiveness. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Strategic Plan for the World Heritage Convention proposes that heritage protection should balance current and future environmental, social, and economic needs and should achieve sustainable development by maintaining or enhancing the brand quality of World Heritage Sites (General assembly of states parties to the convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage, 23rd, 2021). Among them, sites located in coastal and marine areas present unique challenges and opportunities. These heritage landscapes at the land–ocean interface often represent complex continua, where human coastal activities, terrestrial relics, underwater heritage, and ecosystems interact (Henderson, 2019). However, the three-dimensional use of marine space resources and the mixed nature of land use can create functional overlaps and spatial conflicts among multiple activities. There is an urgent need to break through the isolated island protection model and establish an integrated land-sea coordination framework for comprehensive protection and revitalization. Marine spatial planning, as a key tool for coordinating land–sea resource allocation, offers a holistic approach to resolving conflicts between ecological protection, heritage preservation, and economic development (Papageorgiou, 2018). It effectively balances the dual needs of heritage conservation and regional development, introducing revitalization functions consistent with heritage values in moderation to provide new pathways for the sustainable development of world heritage while preserving the authenticity and integrity of the heritage.

World heritage serves as a bridge connecting the past and the future and carries rich historical and cultural information. Protecting world heritage and promoting innovation are indispensable components of urban strategies, as well as the human desire to preserve their own culture and protect the environment. From an international perspective, conservation has evolved from passive and absolute protection to active and relative protection (Yang, 2002). In addition to preserving the inherent characteristics of world heritage, it is essential to maintain its original functions to keep it alive (Shan, 2008), promote economic and social development (UNESCO, 2016), and ensure fair planning is a new approach to world heritage management. Marine spatial planning should consider the protection of world heritage (underwater and coastal) (Agapiou, 2017), strengthen comprehensive planning for coastal areas, and ensure the conservation and sustainable use of world heritage (Altvater et al, 2020), thereby providing opportunities for managing marine cultural heritage (Papageorgiou, 2018). Countries around the world are considering incorporating world heritage into marine spatial planning to protect human culture and underwater heritage, such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the Philippines, Greece, Portugal, Italy, and South Africa (Iskandar et al., 2025). Among them, China has proposed comprehensive protection of historical and cultural resources from a holistic and multi-element perspective (Binjun, 2020) and is exploring the systematic establishment of a historical and cultural protection system within the national territorial space planning framework. It is necessary to establish smooth vertical transmission mechanisms and horizontal connection mechanisms. Some European countries focus on underwater cultural sites (Lees et al., 2024). The Baltic Sea Region Integrated Maritime Cultural Heritage Management (BalticRIM) cross-border project in the Baltic Sea countries integrates maritime cultural heritage into the spatial planning process (Iskandar et al., 2025).

Although Chinese and international scholars have made progress in linking World Heritage with marine spatial planning, their work has primarily concentrated on protection–utilization systems and management models. What remains underexplored is the comprehensive protection and revitalization of World Heritage Sites—an urgent need as these sites face mounting pressures from development, climate change, and human activities. Marine spatial planning is uniquely positioned to fill this gap. As a proven governance tool, it excels in multi-objective coordination, conflict identification, and adaptive management, making it particularly effective for addressing the inherent contradictions between heritage protection and regional development. Harnessing its technical strengths provides not only a new paradigm for safeguarding World Heritage, but also a pathway for unlocking their broader social, cultural, and economic value.

Against this backdrop, this study examines the Levuka Historical Port Town—a representative land–sea interaction World Heritage Site. We develop an analytical framework of Conflict Identification → Synergistic Optimization → Functional Integration and Implementation, which defines rules for conflicts and synergies between land and sea uses. Using spatial analysis, the framework quantifies conflict and synergy indices across activities and calculates a land-use diversity index to diagnose areas of tension and opportunity. Building on these diagnostics, we propose carefully targeted, moderate introductions of complementary functions that prioritize conservation while integrating land and sea uses to stimulate revitalization and heritage transmission. The findings provide decision-support for the sustainable management of Fiji’s first World Heritage Site and offer a transferable methodological approach for coordinated land–sea governance of coastal heritage sites worldwide.

2 Methods

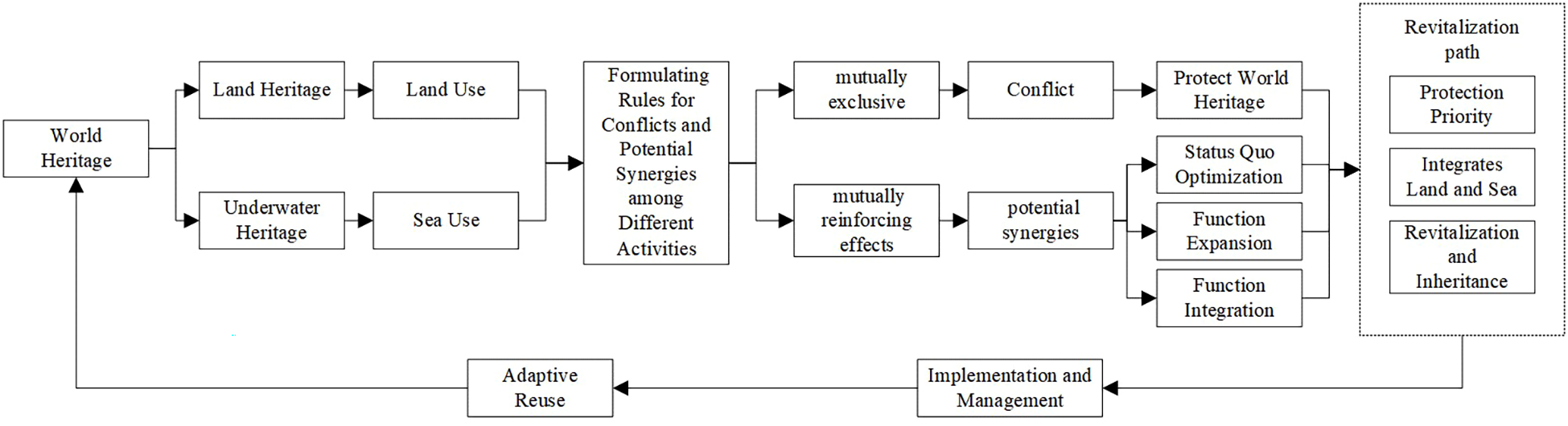

In this paper, we discuss incorporating world heritage into marine spatial planning and using it as a means for the comprehensive protection and revitalization of world heritage. Based on UNESCO’s historic urban landscape approach and land-sea integrated conservation and coordinated development principle, we constructed an analytical framework of conflict identification—synergistic optimization—functional integration. This framework aims to identify conflicts and potential synergies among different activities in coastal areas, balance development and conservation, and explore a world heritage revitalization pathway use, and promotion of revitalization and inheritance (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Revitalization method framework of world heritage.

2.1 Determining cultural relics protection main functions

We collected data on world heritage sites through methods such as field investigations, interview analyses, literature reviews, and drone surveys. A comprehensive survey of the natural, cultural, and human resources in and around the world heritage site was conducted. We analyzed the value characteristics of the heritage site and the social and economic pressures it faces, studied the issues confronting the heritage site, and uncovered the need for revitalization of the world heritage. The premise of revitalizing world heritage is the strict protection of the land used for world heritage, with the main functions being culture-oriented. In this paper, the main function dominated by the attributes of world heritage, we introduce concepts such as mixed land use and land use compatibility and encourage compatibility and the mixed land and sea use in areas such as public facility zones, historical and cultural landscape zones, transportation zones, coastal tourism zones, and commercial areas, with the goal of enhancing the organic connections between various activities and injecting new vitality into the city.

2.2 Formulating rules for conflicts and potential synergies among different activities

The areas where world heritage is located involve various land and sea use activities. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the conflicts and potential synergies resulting from the spatial overlap between world -heritage and land and sea use activities, as well as the conflicts and potential synergies caused by the overlap among land and sea use activities outside the world heritage sites.

When different types of land use are mutually exclusive, they may lead to relationships that cause mutual harm, resulting in conflicts between land and sea use activities. In such cases, if the land used for world heritage is incompatible with other types of land and sea use, protection of the world heritage is required. Conversely, if multiple land use types do not interfere with each other, they may produce mutually reinforcing effects, with potential synergies existing among land and sea use activities. This can be achieved through integration and compatibility within blocks to realize revitalization and utilization. Based on the above methods and combined with China’s land use planning compatibility standards, we formulated land and sea use compatibility rules (Table 1) (Wuhan Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Urban Rural Development, 2023; Beijing Municipal Commission of Planning and Natural Resources, 2022; Department of Natural Resources of Henan Province, 2023). Compatibility means that two or more land and sea use types can coexist within a certain range. Conditional compatibility means that two or more land and sea use types can coexist within a certain range under specific conditions. Incompatibility means that two or more land and sea use types cannot coexist within a certain range.

Table 1

| Types of land and sea use | Land and sea for historical purposes | Land for agriculture | Land without construction | Land for residential use | Land for administration and public service s | Land for commercial and business facilities | Land for industry | Land for transportation | Land for municipal utilities | Land for green space | Land for special purposes | Sea for fishing | Sea for industry mining and communication | Sea for transportation | Sea for tourism and recreation | Sea for special purposes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land and sea for historical purposes | ||||||||||||||||

| Land for agriculture | Incompatibility | |||||||||||||||

| Land without construction | Compatibility | |||||||||||||||

| Land for residential use | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | Compatibility | |||||||||||||

| Land for administration and public services | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | ||||||||||||

| Land for commercial and business facilities | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | |||||||||||

| Land for industry | Incompatibility | Incompatibility | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | ||||||||||

| Land for transportation | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | Compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Conditional compatibility | |||||||||

| Land for municipal utilities | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | Compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | Conditional compatibility | ||||||||

| Land for green space | Compatibility | Incompatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Incompatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | |||||||

| Land for special purposes | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | Compatibility | Incompatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Incompatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | ||||||

| Land for terrestrial water | Compatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Incompatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Compatibility | Conditional compatibility | |||||

| Sea for industry mining and communication | Incompatibility | Conditional compatibility | ||||||||||||||

| Sea for transportation | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Compatibility | |||||||||||||

| Sea for tourism and recreation | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | ||||||||||||

| Sea for special purposes | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility | Conditional compatibility |

Compatibility rules for land and sea use.

2.3 Identifying conflicts and potential synergies among multiple activities

By conducting field surveys and drone surveys and utilizing open data, we obtained orthoimages and 3-D models of the world heritage site. Multi-source data were used to identify various activities in the areas where world heritage is located. Taking blocks (Haochen et al., 2021) and functional areas as the basic units, a block is a fundamental component of the urban structure and can reflect the land use characteristics. In this study, we delineated blocks based on road networks and concentrations of human activities. Town centers are bounded by streets, and edge areas were dynamically defined according to the scope of the activities. Referring to the vector-based mixing degree index (VMDI) method (Zhuo et al., 2019), we assigned values to compute the block compatibility index based on land use compatibility rules (Equations 1, 2): the compatibility value is 1 for two adjacent land or sea use types that are incompatible, 0.5 for those that are conditionally compatible, and 0 for those that are compatible (Zhuo et al., 2019). We calculated the plot and block compatibility degrees (Haochen et al., 2021). High block-level compatibility signifies facilitative interactions among land-sea use activities, whereas low compatibility indicates conflicting utilization patterns.

where Cij is the compatibility value between parcels I and J based on the compatibility relationship table. n is the number of parcels within the influence range of parcel I, and 1 is the theoretical maximum incompatibility value of a parcel. The closer the compatibility value is to 1, the better the compatibility degree of the plot is. The formula is as follows:

where VMDIi is the plot compatibility degree of plot a; and M is the total number of plots in a given block. Statistically, the larger the values of the two are, the better the plot compatibility degree is.

2.4 Analysis of functional optimization strategies

Within blocks, there may be situations where the compatibility between plots is good but the types of use are singular. In this study, we utilized the definition of information entropy proposed by Frank et al. to calculate the land use mixing degree within blocks (Man et al., 2018) to identify the diversity of plot utilization and to balance the land use structure within blocks and promote harmonious land use. If the land use mixing degree is high, functions can be optimized based on the current situation. If the land use mixing degree is low, functions can be moderately implanted according to the land and sea use compatibility rules, the combination of land and sea use functions can be dynamically adjusted, the shortcomings of the world heritage site can be complemented, and synergistic optimization between world heritage protection and regional development can be achieved. The formula for land use mix degree is as follows (Equation 3):

where S is the entropy value of the land use mixing degree. N is the number of land use classification categories; and pi is the proportion of the area of the ith land use type in the region. The larger the value of S is, the higher the land use mixing degree is. Generally, the higher the land use mixing degree of a plot is, the better its environmental performance is.

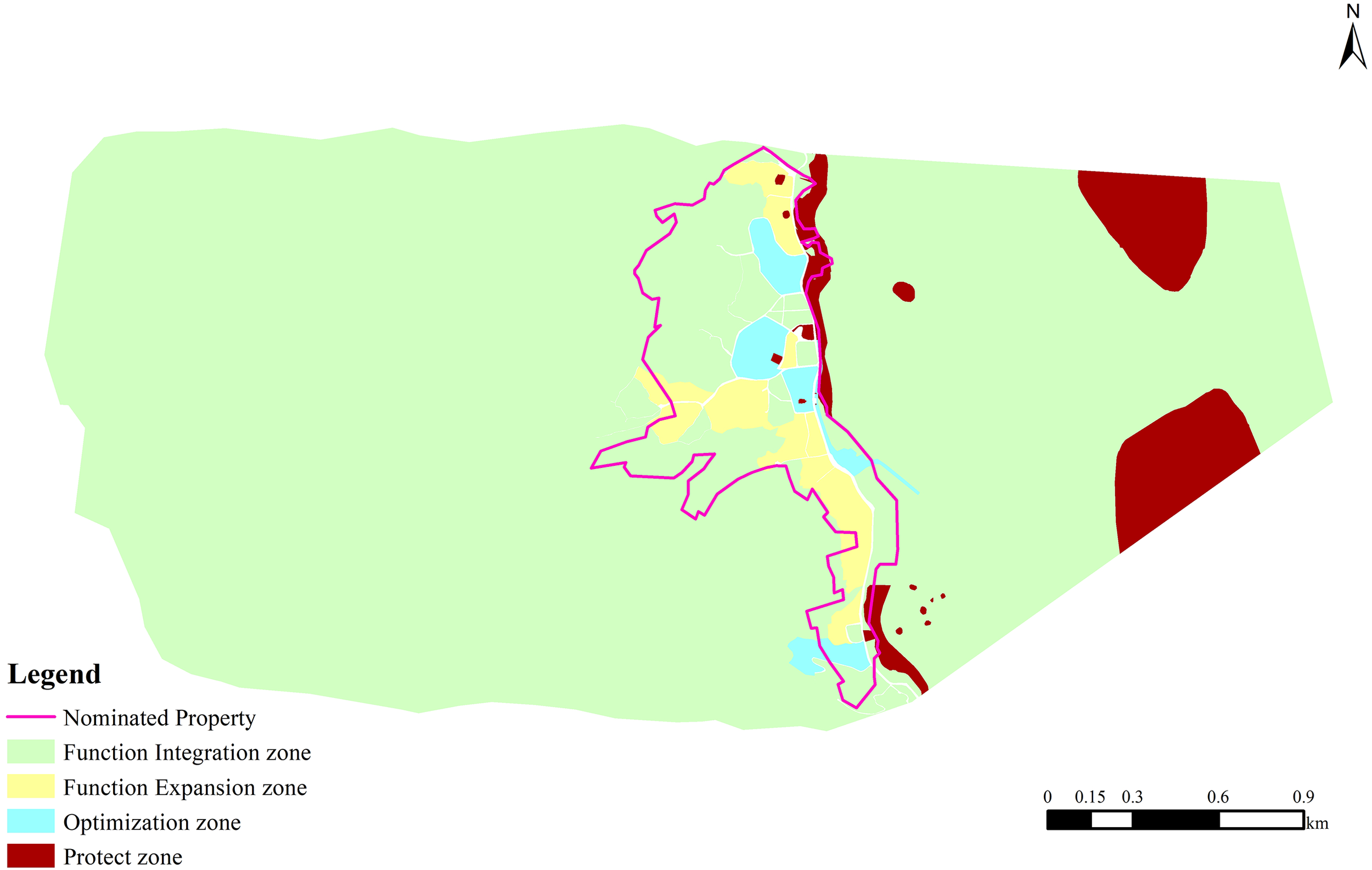

Based on identified conflicts and potential synergies among multiple activities, the World Heritage Site is zoned into function integration zone, function expansion zone, optimization zone and protect zone. Distinct functional optimization strategies are formulated for each zone. The protect zone refers to areas where the world heritage core and ecosystems are located, or where conflicts among multiple activities within the plot, these areas are designated for protection. The optimization zone refers to areas with a high land use mix and potential synergies among multiple activities within the plot; these areas can be upgraded and improved based on existing functions. The function expansion zone refers to areas with a low land use mix and potential synergies among multiple activities within the plot; these areas can undergo functional derivation and expansion based on existing functions. The function integration zone refers to areas with a low land use mix and potential synergies among multiple activities within the plot; these areas can introduce new functions.

3 Study area

The Levuka Historical Port Town (Figure 2) is located on the eastern coast of Ovalau Island in Fiji (17°41′00.16″ S, 178°50′04.32″ E). It served as Fiji’s capital until 1882 and was designated as a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO World Heritage Committee in June 2013. Levuka is Fiji’s sole World Heritage Site but is under risk of being delisted due to a lack of maintenance and effort in rebuilding colonial structures. The total area of the world heritage site is 609.4 hectares. It includes the region within the boundaries of Levuka, extends westward to the edge of the main crater of Ovalau Island, covering an area of 363 hectares. From the northern and southern boundaries of Levuka, it extends eastward to the outer reef edge, encompassing a marine area of 246.4 hectares.

Figure 2

Aerial view of Levuka Historical Port Town.

The Levuka Historical Port Town holds a significant position in the history of Fiji’s development. In 1852, the first government of the Kingdom of Fiji was established in this town. It was the first European settlement in the Fijian Islands and is the oldest and first modern city in Fiji’s history. In the 1820s, under the promotion of chiefs, a port was constructed, making it a commercial and information hub that attracted European settlers. This marked its transition from a beachside mining outpost to a colonial port. After being ceded to Britain in 1874, Levuka became the colonial capital of Fiji. European and American immigrants built warehouses, shops, harbor facilities, residences, religious buildings, educational facilities, and social institutions here. In 1882, the capital was moved to Suva, but a port base was retained in Levuka. Commercial fishing began to thrive in the 20th century. In 1877, Levuka was declared Fiji’s first municipality. Today, Levuka relies on natural resources for its livelihood and faces development challenges: many ancient buildings have deteriorated (Figure 3) or collapsed due to lack of protection, and incomplete supporting facilities have led to low urban vitality (Figure 4), necessitating the exploration of new development and conservation pathways.

Figure 3

Sacred Heart Parish Catholic Church.

Figure 4

Commercial activities.

4 Results

4.1 Digitalization of world heritage

The Levuka Historical Port Town is primarily dominated by residential activities, supplemented by commercial, industrial, and service activities. The commercial and industrial functions are distributed along the coastline. Although the facades of historical buildings retain the diverse color characteristics of the 19th century colonial period, some heritage structures face issues such as facades weathering and structural deterioration. Infrastructure development is unbalanced. The town has only two catering facilities that operate during fixed hours, and one of them closes intermittently. There is one port with infrequent ship schedules, and air transportation hub functions have stagnated. Accommodations are mainly provided by homestays. The public service system has significant shortcomings, including insufficient nighttime water supply. The tourist structure is homogeneous and dominated by backpackers.

In response to the current status and problems of the world heritage site, a preventative protection strategy was first adopted for the world heritage itself, with digital revitalization of the world heritage structures (Penjor et al., 2024). Through drone oblique photography, digital backups of the current state of the world heritage structures and geographical spatial information were made, fully recording the current material form of the world heritage. A 3-D model for digital protection was constructed, preserving image data for the World Heritage Site (Figure 5), which is beneficial for the protection and management of world heritage and promotes revitalization of the Levuka Historical Port Town.

Figure 5

Three-dimensional model of the Levuka Historical Port Town.

4.2 Functional revitalization of world heritage

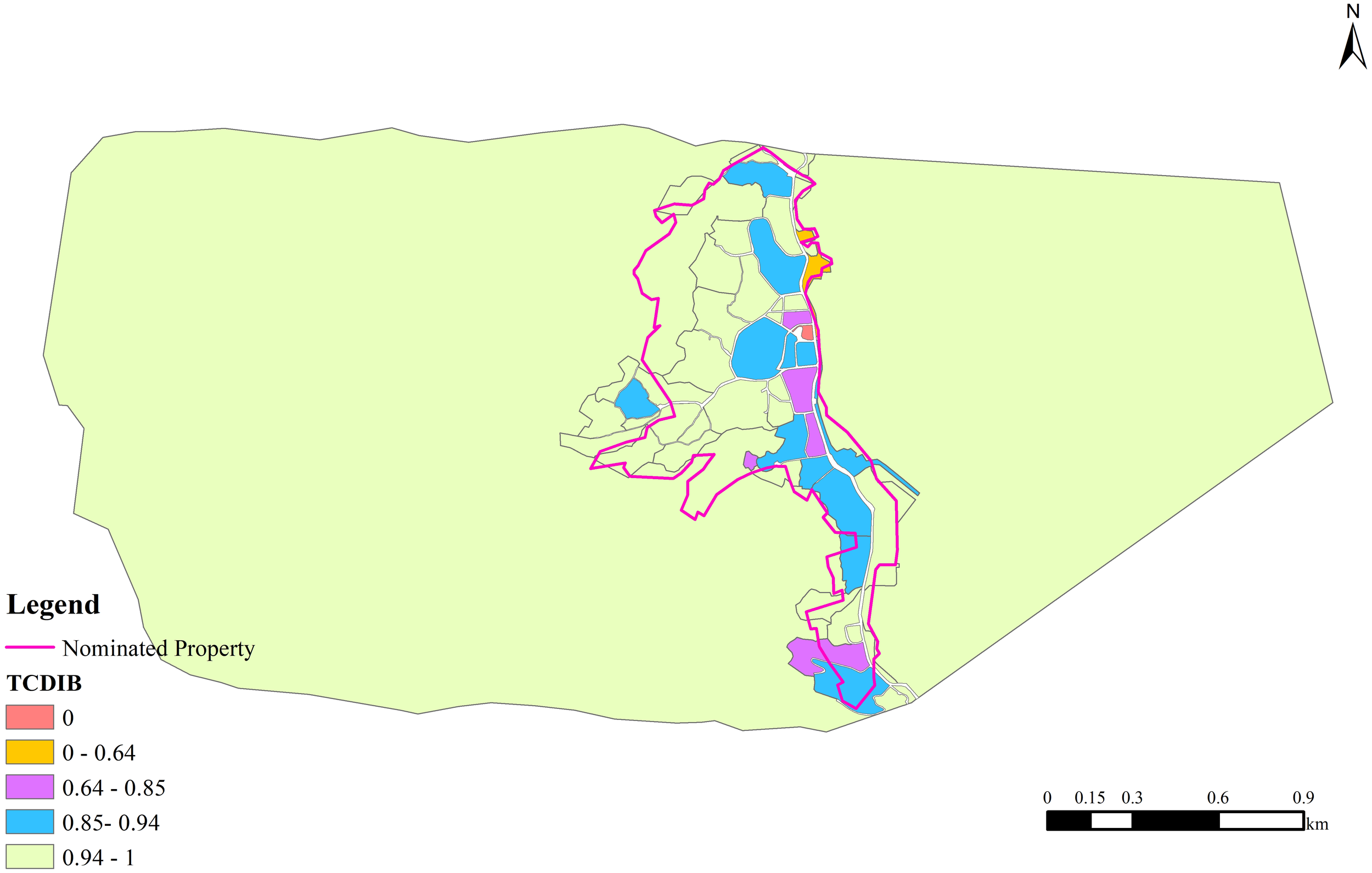

According to the calculation results of VMDIi and TCDIB, the compatibility degree of the Levuka Historical Port Town mostly falls within the range of 0.941–1 (Table 2; Figure 6). The overall compatibility is favorable, with land use functions within a block being mutually compatible and demonstrating a generally positive trend. One block in the northern part of Levuka Town is incompatible because it is primarily composed of commercial and public service functions, which conflict with each other. The compatibility degrees of other blocks are relatively high. For example, the coastal blocks, which are mainly used for commerce, green spaces, public service facilities, and residential purposes, promote mutual collaboration among activities within these blocks. There are few sea use activities, mainly focusing on fishing and transportation, and sea use compatible activities should avoid navigation channels.

Table 2

| Serial number | TCDIB | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–0.64 | 3 |

| 2 | 0.64–0.85 | 6 |

| 3 | 0.85–0.94 | 8 |

| 4 | 0.941–1 | 40 |

Table of TCDIB frequency.

The TCDIB frequency represents the number of plots within that numerical range. A higher TCDIB value indicates better land and sea use compatibility.

Figure 6

TCDIB map of the Levuka Historical Port Town, where TCDIB reflects the compatibility level of marine and land use, with higher numerical values indicating better compatibility. The spatial extent of the area is sourced from the UNESCO World Heritage Convention.

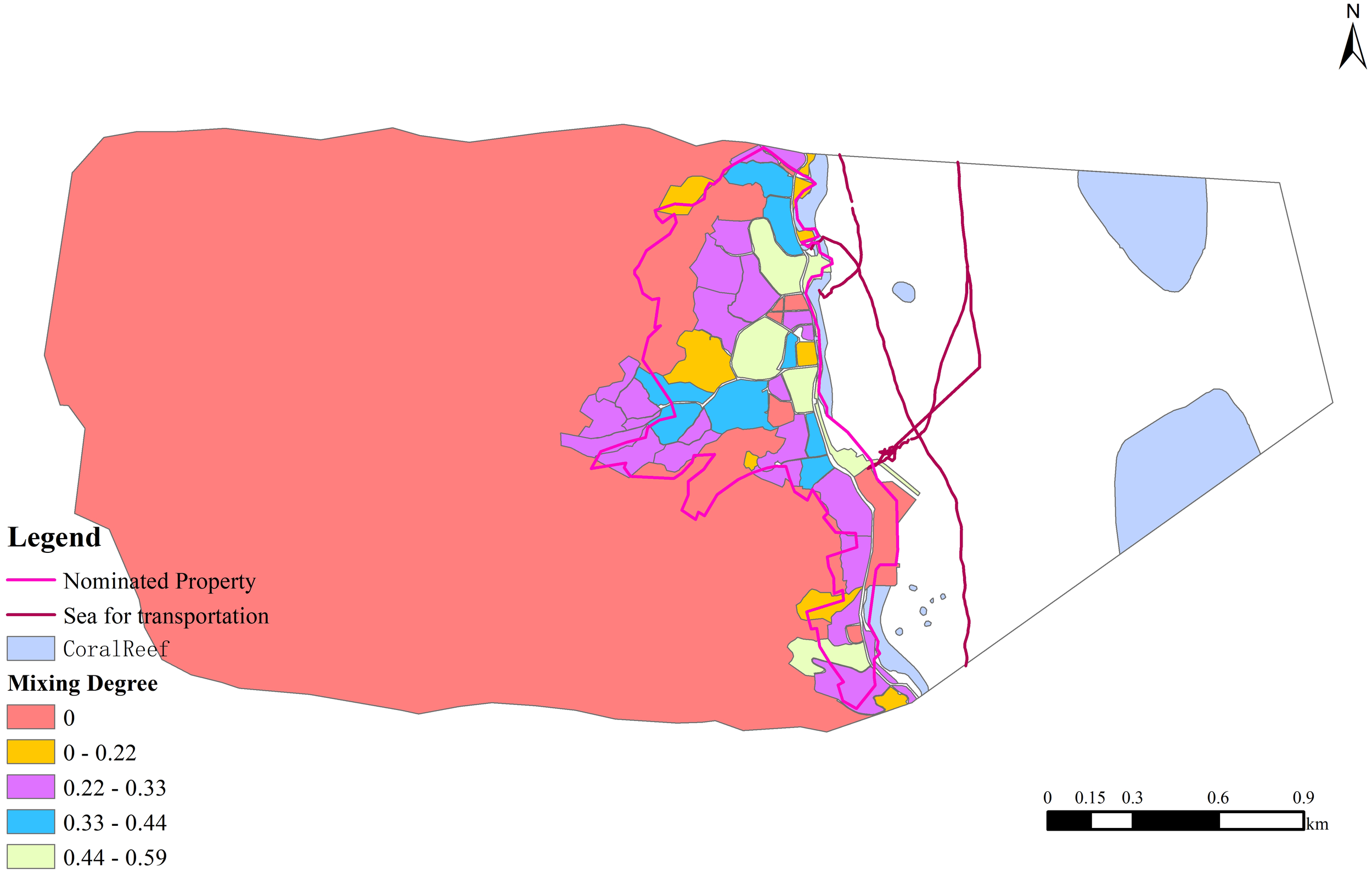

According to the results of the land use mixing degree analysis, the overall land use mixing degree of the Levuka Historical Port Town is low. The block with the highest mixing degree has a value of 0.58, and the land use mixing degree is concentrated within the range of 0.22–0.33, indicating that the human activities within the blocks are relatively singular and reflecting the prominent feature of simplified urban functions. The spatial distribution exhibits a trend of decreasing from the T-shaped high-value areas in the central and coastal regions toward the north and south (Figure 7; Table 3), indicating that the area has the potential for compound functional development.

Figure 7

Land use mixing degree map of the Levuka Historical Port Town. A higher land use mix value indicates greater land use diversity.

Table 3

| Serial number | Land use mixing degree | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–0.22 | 16 |

| 2 | 0.22–0.33 | 27 |

| 3 | 0.33–0.44 | 7 |

| 4 | 0.44–0.59 | 7 |

Table of land use mixing degree frequency, frequency represents the number of plots within a specific value range.

A higher frequency indicates a greater quantity of plots in that range.

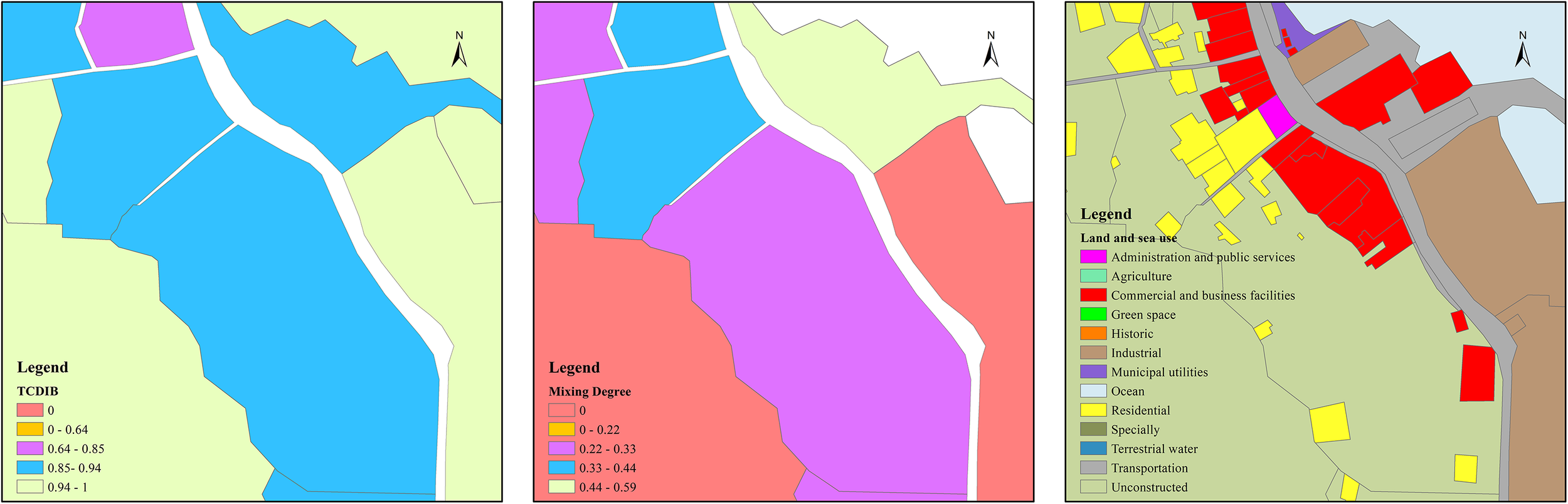

Comparative analysis (Figure 8) of the block compatibility and land use mixing degree indicates that the Levuka Historical Port Town exhibits spatial characteristics of high compatibility and a low mixing degree. For example, in a southern block where the land use is dominated by commercial services and residential functions, the land use compatibility reaches 0.89, but the land use mixing degree is only 0.32. The good compatibility indicates that the various land use functions within the block work well together, but the land is not used efficiently, suggesting the potential for the introduction of additional functions.

Figure 8

Maps of the compatibility degree, mixing degree, and land use types for a block in the Levuka Historic Port Town, a single block contains multiple land use types, exhibiting the phenomenon of high compatibility but low mix degree.

Based on the identification of conflicts and potential synergies among multiple activities, as well as the results of land use mix analysis, Levuka Historical Port Town is categorized into protection zone, optimization zone, function expansion zone and function integration zone (Figure 9). The protection zone refers to the area where the core of the world heritage and its surrounding environment are protected. The optimization zone refers to the area where upgrading and improvement are carried out based on existing functions. The function expansion zone refers to the area where functional derivation and expansion are conducted based on existing functions. The function integration zone refers to the area where new functions need to be introduced to drive existing development. The majority of Levuka Historical Port Town is classified as a Function Integration Zone, demonstrating significant potential for world heritage revitalization. Guided by the principle of “protection first” should be adhered to for functional optimization. Efforts should be made to develop world heritage friendly and vitality-restoring functions, such as fishing/collecting aquatic, crop production, ritual/spiritual/religious and association uses, indigenous hunting gatherings and collecting, tourism/visitation/leisure and entertainment, so as to revitalize world heritage sites.

Figure 9

Zone for revitalization of Levuka Historical Port Town, showing protection zone, optimization zone, function expansion zone and function integration zone.

4.3 Marine spatial planning + revitalization model

The Levuka Historic Port Town faces challenges such as a low land use efficiency and lagging blue economic development. Marine spatial planning is used to coordinate conflicts between land and sea use. By leveraging terrestrial relics to drive the utilization of surrounding resources, exploring underwater relics, and seeking a world heritage revitalization path that prioritizes protection, this approach integrates land and sea and revitalizes heritage. Guided by the land and sea use compatibility rules, the land and sea resources are coordinated, and the protection of the world heritage itself is prioritized in conflict scenarios. In scenarios where multiple activities do not interfere with each other and the utilization efficiency is low, based on the zoning for functional optimization, moderate functional integration is utilized to supplement the shortcomings of the infrastructure, public service facilities, and commercial facilities, developing world heritage friendly functions with vitality regeneration potential, thus achieving functional optimization. In the planning and management of world heritage sites, it is necessary to dynamically assess the conflicts and synergies arising from land and sea use activities, promote adjustments in the combination of land and sea use functions, and achieve the protection and adaptive reuse of world heritage, thereby promoting the revitalization and inheritance of world heritage.

5 Discussion

5.1 Comparative analysis of coastal world heritage management models

Conflicts between the development of human activities and world heritage protection are common in coastal world heritage sites. It is necessary to balance economy and world heritage protection. Taking the Great Barrier Reef (a World Heritage Site in Australia) and the Amalfi Coast (a World Heritage Site in Italy) as examples, the economic development of both places relies heavily on world heritage resources. However, these economic activities may conflict with the goals of world heritage protection. To alleviate this conflict, a sound legal framework has been established, zoning management has been implemented to regulate the use of different areas, emphasis has been placed on the protection of culture and world heritage, and management strategies have been adjusted based on evaluation or monitoring. Consistent with the findings of this paper, the economic activity in Levuka world heritage relatively low. Strategies for the protection and revitalization of world heritage can be explored through marine spatial planning, by Evaluating its ability to capture complex land-sea interactions, multifunctional use, and adaptive management potential. Based on this, functional zoning can be carried out in Levuka Town, and adaptive management implemented to enhance the capacity for cultural inheritance and sustainable development.

5.2 Zoning for world heritage protection and revitalization based on quantitative identification

Scholars have proposed different theories and methods for the protection and revitalization of World Heritage. For example, assessing applicability based on literature extraction (Iskandar et al., 2025), using ArgGis technology and spatial analysis to evaluate the pressure of human activities on world heritage (Agapiou et al., 2017), and establishing a comprehensive participatory model for the protection and management of marine cultural heritage in marine protected areas (Breen et al., 2024). The core idea is that marine spatial planning is an effective tool for world heritage protection, but it lacks zoning and adaptive management. The paper identifies conflicts and potential synergies between various activities in different land-sea spatial blocks, quantitative evaluation can be conducted from dimensions such as inter-activity compatibility and synergistic. This enables effective identification of conflict areas in land-sea space utilization and exploration of potential synergy opportunities. With the goal of achieving balanced development between human activity distribution and world heritage protection, combined with the characteristics of land mixing degree and marine spatial planning, zoning for protection and revitalization is divided. Differentiated protection and revitalization measures are formulated based on the characteristics of each zone. This not only better serves local policy formulation and practice optimization, but also is consistent with excellent local experiences in world heritage protection and utilization.

5.3 Adaptive management path for world heritage protection and revitalization

This paper reveals the spatial tensions and opportunities between land and marine use through quantitative conflict and synergy indices, demonstrates the path for world heritage protection and revitalization, and provides ideas and methodological references for world heritage sites with insufficient vitality and related research. Meanwhile, combined with the zoning distribution for the protection and revitalization of Levuka Town, it promotes dynamic monitoring and zoning adjustment mechanisms, facilitates the implementation of adaptive management, provides a basis for the management of protection and revitalization, and offers references for local policy formulation. This aims to achieve a dynamic balance between multi-functional spatial use and heritage protection, further adjust to form the optimal plan adapting to local world heritage protection and revitalization, and ultimately realize the coordinated development of heritage protection, community development, and ecological sustainability.

6 Conclusions

In this study, we measured the relationship between land and sea use in the Levuka Historical Port Town world heritage site from the perspective of marine spatial planning and investigated potential conflicts and synergies between land and sea use activities. In conflict scenarios, it is necessary to strictly protect the land and sea use types that support the core functions of world heritage. In synergistic scenarios, multiple functions can coexist compatibly. Based on China’s relevant regulations on land and sea use compatibility, compatibility rules for land and sea use were formulated, and the relationships and utilization diversity of plots in the Levuka Historical Port Town were explored using blocks as the basic units. In this study, we found that the Levuka Historical Port Town exhibits good overall compatibility, but the land use mixing degree is low, and there is room for moderate functional integration and optimization. The Levuka Historical Port Town is divided into a protection zone, an optimization zone, a function expansion zone and a function integration zone. Through scientific planning and management of world heritage sites, it is possible to target and supplement shortcomings in the infrastructure, public service facilities, and commercial amenities, achieving active renewal of land and sea use functions. This planning approach, based on analyzing of the interactions between land and sea uses, not only maintains the integrity of the world heritage but also promotes regional social and economic development through functional optimization, providing an actionable planning pathway for sustainability of the coastal world heritage sites.

In this study, we conducted a beneficial exploration of the overall protection and revitalization of a World Heritage Site from the perspective of marine spatial planning, providing a new idea for the protection and revitalization of world heritage sites. We propose an integrated land and sea use approach that is suitable for most coastal World Heritage Sites and that can accurately identify the relationship between land and sea use. However, this study still has some limitations. 1) When measuring the degree of compatibility, we find ecosystem and marine transportation data. some marine data were missing, and the ability to collect and integrate data needs to be improved. 2) The formulation of the compatibility rules was mainly based on Chinese experience and UNESCO world heritage convention documents, with limited consideration of local context. In response to this, future in-depth research can be carried out in several areas. 1) Future studies should systematically collect marine-related quantitative information through channels such as the Fiji local government to improve the data foundation. 2) Local professionals in planning and management should be involved in the formulation of compatibility rules, thus making the identification of land and sea use relationships more locally applicable. 3) The positioning of the world heritage within the marine spatial planning management system should be explored, and the establishment of a more comprehensive management system should be promoted.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

WK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft. XT: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. QZ: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. AP: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XM: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. PZ: Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Ministry of natural resources of Bilateral and multilateral international cooperation (C3250GJ02), China Oceanic Development Foundation of Technical Pathways for National Cooperation in Marine Spatial Planning under the Blue Partnership Framework (C3220C004); Ministry of Foreign Affairs of The Construction of the China-ASEAN Blue Partnership (Phase II)(C3250DM02).

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors for their insightful comments, which helped to improve the manuscript. We are grateful to Arpana Pratap and Henry Galuvakadua for giving onsite support during the survey in Levuka. We thank Teng Xin and Zhao Qiwei for their support in the interview.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Agapiou A. Lysandrou V. Diofantos G. Hadjimitsis . (2017). The Cyprus coastal heritage landscapes within Marine Spatial Planning process. J. Cultural Heritage23), 28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.culher.2016.02.016

2

Altvater S. Aps R. Bashirova L. Blazauskas N. Danilova L. Herkül K. et al . (2020). Final publication of the Baltic Sea Region Integrated Maritime Cultural Heritage Management Project 2017-2020. (Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, Sweden: BalticRIM project).

3

Beijing Municipal Commission of Planning and Natural Resources (2022). Beijing municipal guidelines for the mixed use of construction land (Trial). Beijing, China.

4

Binjun G. Jiaqi Y. (2020). Strategies of activation and utilization of historic buildings in traditional village under the perspectives of tenacity ——A case study of xinzhuang village of gaoqiao town. Architecture Culture05), 130–131.

5

Breen C. Tews S. Nikolaus J. Ray N. Holly G. Andreou G. et al . (2024). Developing an integrated framework for Marine Cultural Heritage (MCH) and Marine Protected Areas (MPA) across Africa and the Middle East. Mar. PolicyHenan, China, 165, 106218. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106218

6

Department of Natural Resources of Henan Province (2023). Notice on promoting the mixed development and utilization of land to promote the transformation and upgrading of industries (Draft for comments). Henan, China.

7

Haochen S. Miaoxi Z. Peiqian C. (2021). Measuring the functional compatibility of land from the perspective of land-use mix:A case study of xiangtan. Trop. Geogr.41, 746–759. doi: 10.13284/j.cnki.rddl.003361

8

Henderson J. (2019). Oceans without history Marine cultural heritage and the sustainable development agenda. Sustainability11, 5080. doi: 10.3390/su11185080

9

Iskandar D. Safuan C. D. M. Latip R. Saiffuddin A. H. Shaari H. Bachok Z. et al . (2025). Effective conservation of cultural and natural heritage of the Bidong archipelago via marine spatial planning: A review. Ocean Coast. Manage.262 (000). doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2024.107538

10

Lees L. Herkül K. Aps R. Francisco R. Karro B. K. Roio M. et al . (2024). Integrating cultural and natural assets in marine spatial planning: A new approach for joint management of cultural and natural assets[J]. Journal for Nature Conservation, 81(000), 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2024.126701

11

Man Z. Zhao R. Yuan Y. Feng D. Yang Q. Wang S. et al . (2018). Impact of Land-mixing Degree of Residential Area on Carbon Emissions of Commuting: A Case Study of Typical Residential District, Jiangning district, Nanjing. Human Geography, 33 (1), 6. doi: 10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2018.01.009

12

Papageorgiou M. (2018). Underwater cultural heritage facing maritime spatial planning: legislative and technical issues. Ocean Coast. Manage.165, 195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.08.032

13

Penjor T. Banihashemi S. Hajirasouli A. Golzad H. (2024). Heritage building information modeling (HBIM) for heritage conservation: Framework of challenges, gaps, and existing limitations of HBIM. Digital Appl. Archaeol. Cultural Heritage35, e00366. doi: 10.1016/j.daach.2024.e00366

14

Shan J. (2008). Living heritage”: innovations in the protection of the grand canal. China Ancient City02), 4–6. doi: CNKI:SUN:ZGMI.0.2008-02-002

15

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Paris,France, International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM), Rome, Italy, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), France, International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Switzerland. World Heritage institute of Training and Research for the Asia and the Pacific Region under the auspices of UNESCO, WHITR-AR, Shanghai, China . (2020). Guidance and toolkit for impact assessments in A world heritage context.

16

UNESCO (2016). Culture urban future; global report on culture for sustainable urban development; summary. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

17

World heritage centre . (2021). General assembly of states parties to the convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage, 23rd (Paris: UNESCO), 695.

18

Wuhan Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Urban Rural Development (2023). Wuhan planning land use compatibility management regulations. Wu Han, China.

19

Yang R. (2002). Some clarifications on the relationship between World Heritage sites and tourism. Tourism Tribune017 (006), 7–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-5006.2002.06.004

20

Zhuo Y. Zheng H. Wu C. Xu Z. Li G. Yu Z . (2019). Compatibility mix degree index: A novel measure to characterize urban land use mix pattern. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst.75, 49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2019.01.005

Summary

Keywords

marine spatial planning, world heritage, revitalization, protection, function optimization

Citation

Kang W, Teng X, Zhao Q, Pratap A, Meng X and Zhang P (2025) Comprehensive protection and revitalization of Levuka world heritage from the perspective of marine spatial planning. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1658939. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1658939

Received

03 July 2025

Accepted

30 September 2025

Published

03 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Md. Nahiduzzaman, WorldFish, Bangladesh

Reviewed by

Subrata Sarker, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Bangladesh; Han Zou, Hubei University of Technology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Kang, Teng, Zhao, Pratap, Meng and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xin Teng, notctengxin@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.