Abstract

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) is increasingly recognized as a strategic approach to balance economic development, biodiversity conservation, and social equity in ocean governance. However, implementation across the Asia-Pacific remains uneven, shaped by divergent political priorities, institutional capacities, and planning cultures. This systematic review analyzes 57 peer-reviewed publications to examine the drivers and enabling conditions of MSP in the region, categorizing 13 factors into four themes: plan attributes, institutional context, participation, and integration. Findings reveal marked regional contrasts. In many Asian countries, MSP is primarily driven by economic imperatives—such as maritime transport and industrial development—while ecological and socio-cultural objectives receive comparatively less attention. In contrast, Oceania demonstrates more integrated and participatory approaches, emphasizing sustainability, traditional knowledge, and community engagement. Progress has been noted in the development of adaptive planning frameworks and legal foundations; however, persistent gaps remain in data infrastructure, human and financial capacity, and inclusive stakeholder engagement. Integration emerged as the weakest enabling condition, with widespread deficiencies in intergovernmental coordination, land–sea connectivity, and cross-sectoral policy alignment. To strengthen MSP implementation, the review highlights the need to operationalize ecosystem-based management (EBM), embed ecological thresholds in spatial planning, institutionalize inclusive participation, and promote regional cooperation. Lessons from the Asia-Pacific offer broader relevance, contributing to global efforts to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 14 and the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Advancing these actions is essential for fostering sustainable, inclusive, and resilient ocean governance.

1 Introduction

Oceans and coastal areas are increasingly contested spaces where economic, ecological, and socio-cultural interests converge. Accelerating urbanization, industrial development, climate change, and biodiversity loss—combined with the rapid expansion of maritime industries—have intensified pressures on marine ecosystems, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, which hosts some of the world’s most biodiverse and densely populated coastlines (UNEP, 2020; IPBES, 2019).

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) has emerged as a globally recognized governance tool for coordinating human activities and promoting sustainable ocean use through an ecosystem-based approach (Ehler and Douvere, 2009; Jay et al., 2013). By integrating ecological, economic, and social objectives, MSP provides a structured framework to reduce sectoral conflicts and guide long-term ocean management (Katsanevakis et al., 2011). Over the past two decades, more than 100 countries have initiated MSP processes to meet conservation goals, enable sustainable blue economy development, and advance global commitments such as SDG 14 (IOC-UNESCO, 2022; Ehler, 2021).

Despite this progress, implementation remains uneven, particularly in the Asia-Pacific, where MSP is shaped by diverse governance systems, development priorities, and institutional capacities (Gacutan et al., 2022; Domínguez-Tejo et al., 2016). Subregional contrasts are pronounced: while some countries prioritize industrial growth and resource extraction, others emphasize biodiversity protection, cultural heritage, and participatory governance (Domínguez-Tejo and Metternicht, 2018; Peart, 2019). Persistent barriers—such as fragmented legal frameworks, weak land–sea integration, limited technical capacity, and inadequate stakeholder engagement—continue to undermine planning effectiveness (Teng et al., 2021; Giffin et al., 2021).

Although the global MSP literature is expanding, region-specific and comparative analyses remain scarce, particularly regarding the drivers that motivate MSP adoption and the enabling conditions that determine its success (Zuercher et al., 2022a; Foley et al., 2010). Understanding these factors is critical for improving MSP design, promoting equity, and enhancing the resilience of marine governance systems.

This study addresses these gaps through a systematic review of 57 peer-reviewed publications on MSP in the Asia-Pacific. It has two main objectives: (1) to identify and analyze the key drivers influencing MSP adoption across countries and subregions, and (2) to examine enabling conditions that support or hinder implementation. The findings reveal regional patterns, persistent challenges, and strategic entry points for advancing inclusive, ecosystem-based MSP. While focused on the Asia-Pacific, lessons drawn from this analysis carry global relevance, offering insights for other regions facing similar governance and ecological challenges.

2 Methods

This study applied a systematic review to examine MSP development in the Asia-Pacific, following four steps: (1) defining objectives and research questions; (2) developing a search protocol; (3) applying inclusion criteria; and (4) conducting content analysis and synthesis (Elrick-Barr et al., 2022; McLeod et al., 2021; Ferro-Azcona et al., 2019; Pittman and Armitage, 2016). Research objectives and guiding questions are presented in Table 1. The review was also partly informed by insights from the project “Marine Spatial Planning: Application to Local Practices” (Satumanatpan et al., 2023), which supported the initial scoping and development of the thematic framework.

Table 1

| Objectives | Research Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. MSP Overview | • How MSP-related publications evolved in terms of quantity, journal distribution, publication types, geographic focus, and what is the current status of MSP implementation in the Asia-Pacific region? |

| 2. MSP Drivers | • What are the primary drivers of MSP in the Asia-Pacific region, and how do these drivers vary between Asia and Oceania? |

| 3. MSP Enabling Conditions | • What are the enabling conditions for effective MSP, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, and how are these conditions influenced by national or regional characteristics? |

| 4. MSP Future Challenges | • What are the challenges for Asia-Pacific countries to improve their MSP performances? |

Objectives and research questions.

2.1 Systematic review process

The review focused primarily on peer-reviewed literature from the Scopus database, covering the period 2003–2023. To complement the Scopus results, additional MSP-relevant sources were identified through the MSP Global platform, the European Commission, and UNESCO’s MSP database.

Search terms included combinations of “Mari*” (to capture both “marine” and “maritime”) with “spatial,” “functional,” “planning,” “zoning,” “MSP,” and “MFZ.” Searches were limited to article titles, abstracts, and keywords. Duplicate and irrelevant documents were excluded using predefined criteria.

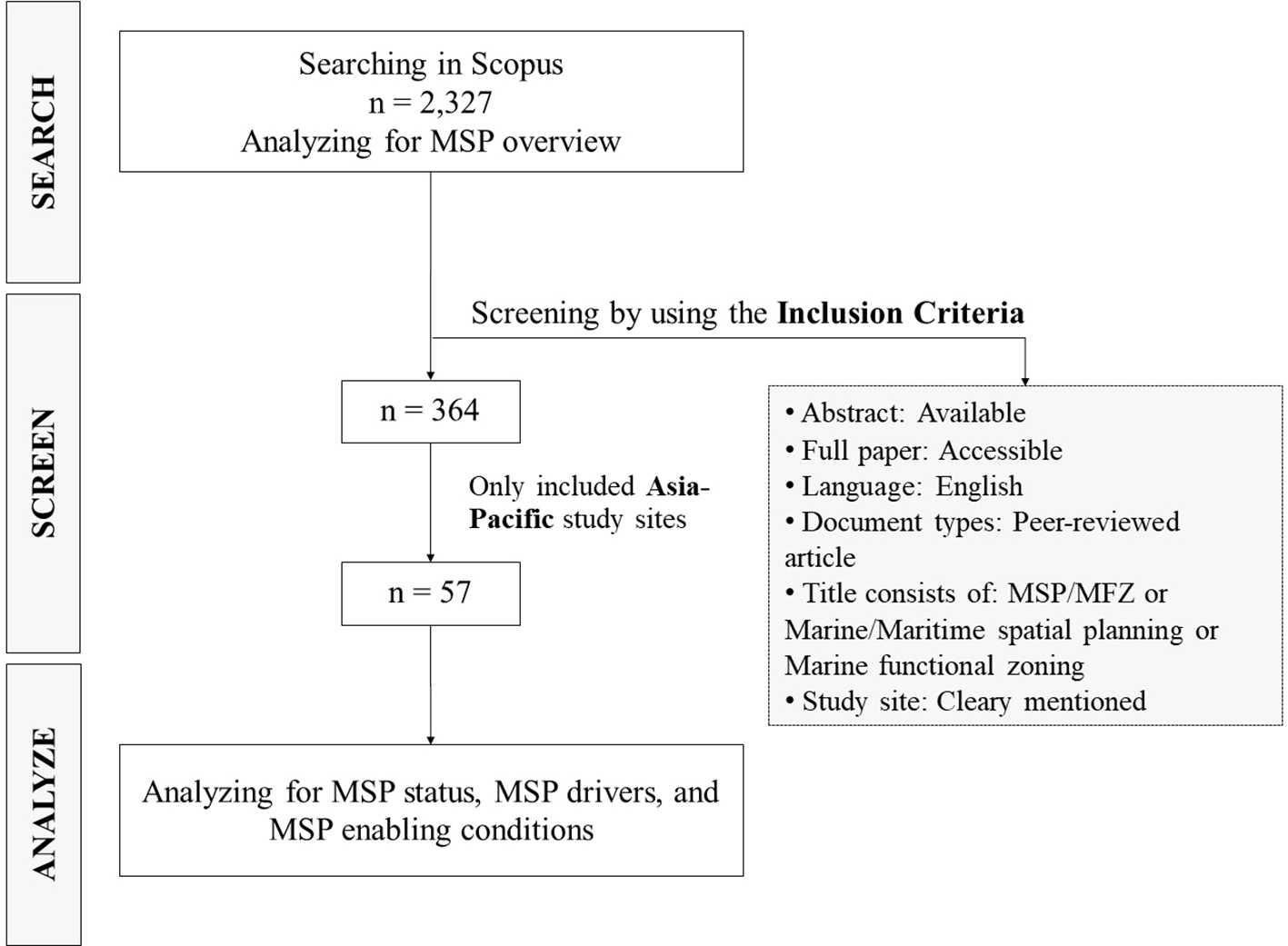

The search yielded 2,327 publications, which were categorized by publication type, year, and geographical focus (Figure 1). A total of 57 relevant papers addressing MSP implementation in the Asia-Pacific were selected for detailed analysis (see Supplement 1).

Figure 1

The process of systematic review.

Geographical coverage included 20 countries: China, Taiwan, Indonesia, Israel, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Malaysia, India, Saudi Arabia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, French Polynesia, Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia, and Timor-Leste. The study focused on MSP within national jurisdictions, excluding high seas and areas beyond national jurisdiction such as the Weddell Sea and Antarctica.

The selected literature was analyzed to assess (i) the current status of MSP implementation in each country, (ii) MSP drivers, and (iii) enabling conditions that influence effectiveness.

2.2 MSP drivers

MSP drivers were classified into five categories—environmental (marine conservation concerns, marine pollution, and climate change), sociological (conflict among human uses, social & cultural values, social well-beings, equity & justice, and population growth), economic (economic growth concerns, sustainable uses, and new & emerging human uses), institutional and political (need more integrated approach and transboundary-planning advantage), as well as others (research purposes)—covering a total of 17 drivers. This framework was adapted from Zuercher et al. (2022a); Ehler (2021), and UNESCO/European Commission (2021), with adjustments based on themes identified through the literature review.

2.3 MSP enabling conditions

Thirteen enabling conditions were identified and classified into four categories following Ehler and Douvere (2009) and Zuercher et al. (2022b): (1) plan attributes, (2) institutional context, (3) participation, and (4) integration. These conditions formed the basis for analyzing how various factors contribute to or hinder MSP success across the region (Table 2).

Table 2

| Group | Enabling condition | Brief description |

|---|---|---|

| Plan Attributes | Adaptability | Plan is adaptable to future changes (e.g., climate change, new and emerging human uses, natural disasters) and has an adaptive process meant to facilitate ongoing updates, including the process of monitoring, evaluation, and revision of the MSP plan. |

| Data & Analytical tools | Supports by various types of data for plan development (e.g. human use data, ecological services, cumulative impacts) and the application of tools (software) that are essential for the analysis that enhance the process of decision-making (e.g. trade-offs analysis) | |

| Plan Design | The design of the MSP plan, whether composed of clear objectives, ecosystem-based, well-balanced in terms of ecological/social/economic goals, flexible, or poorly designed to cope with changes of situation, spatial coordination | |

| Inclusion of Traditional Knowledge | The acknowledgement and inclusion of traditional knowledge in the plan design process and plan development | |

| Institutional Context | Legislation & Enforcement | Law, policy, and national framework/strategy at different levels that will support the MSP plan development and implementation, including the enforcement of rules and policies related to the plan |

| Authority & Capacity | Whether there is an authority that’s responsible for MSP plan development and implementation or not, which includes their resources (experts) and capacity (their understanding, awareness, skills, especially the communication skills, and their willingness and commitment to execute their tasks) | |

| Human & Financial Resources | The workforce or the working capacity of the government agencies, as well as the funds/budget received either from the central government or external sources (e.g., donations, grants, etc.) | |

| Participation | Stakeholder Engagement & Empowerment | Stakeholder engagement and participation in the MSP process (along the plan development and in decision-making process), including the activities (e.g., training, workshops, or educational sessions) to empower and increase the stakeholders’ understanding, awareness, and knowledge of the MSP plan and implementation |

| Partnerships | Inclusion of partnerships, whether cross-border partnerships or partnerships from the private sector (e.g., institutions, oil/gas companies) | |

| Transparency | The context of the MSP process includes diverse stakeholders, during the development MSP plan, decision-making, and sharing information with the public. All the processes were opened to all eyes, genuinely and transparently. | |

|

Intergovernmental Integration | The coordination and collaboration between different levels of government, and whether they exist in harmony or conflicting situations. |

| Land-sea Interaction | The acknowledgment of transboundary issues and engagement in transboundary coordination (especially the land-sea interaction, cross-border interaction) | |

| Policy Integration | Whether there is a policy that addresses the interests and concerns across ocean use sectors, integrating a wide range of ocean and coastal uses and concerns (e.g., environmental, economic, and social concerns) |

MSP enabling conditions and brief descriptions.

3 Results

This section is organized into three main sub-sections: (1) an overview of MSP; (2) an analysis of MSP drivers; and (3) a discussion of enabling conditions, including plan attributes, institutional context, participation, and integration.

3.1 MSP overview

A total of 2,327 MSP-related papers were retrieved from Scopus between 2003 and 2023 (last accessed: July 2023), revealing a consistent upward trend in publications. Research output peaked in 2022 with 414 articles. Most documents were research articles (78.2%), followed by conference papers (6.8%), book chapters (6.5%), and others (8.5%).

The most frequently represented journals were Marine Policy (13.1%), Ocean and Coastal Management (7.5%), and Frontiers in Marine Science (5.1%). Other contributing journals included Sustainability, ICES Journal of Marine Science, Science of the Total Environment, Marine Pollution Bulletin, Biological Conservation, Journal of Environmental Management, and Marine Ecology Progress Series.

In terms of geographic focus, 63% of publications addressed MSP issues in Europe (n=229), followed by the Americas (19%, n=68), Asia (13%, n=47), Africa (7%, n=24), and Oceania (4%, n=14). Several studies included multiple regions, resulting in duplicated counts.

Europe dominates global MSP literature, reflecting its early and extensive adoption of MSP across territorial waters and exclusive economic zones (EEZs). In the Asia-Pacific region, 30 of the 57 selected papers (52.6%) focused on China and Australia—countries with the most advanced MSP initiatives in the region. The underrepresentation of other countries, such as Japan and South Korea, is likely due to limited availability of English-language publications in global databases.

Focusing on MSP implementation in the Asia-Pacific, we found that most countries applied MSP within their territorial seas (43%) and EEZs (41%), while only 16% addressed transboundary areas. MSP progress varied considerably across the region: 23.5% of countries had not yet initiated MSP (e.g., Israel, certain districts in Indonesia, such as South Konawe District and Kaledupa Island in Sulawesi, and the southern part of Taiwan), while 9.8% (e.g., Pakistan and India) were in early planning stages. Some countries, such as China, Australia, and French Polynesia, had already entered the revision phase (19.6%).

3.2 MSP drivers

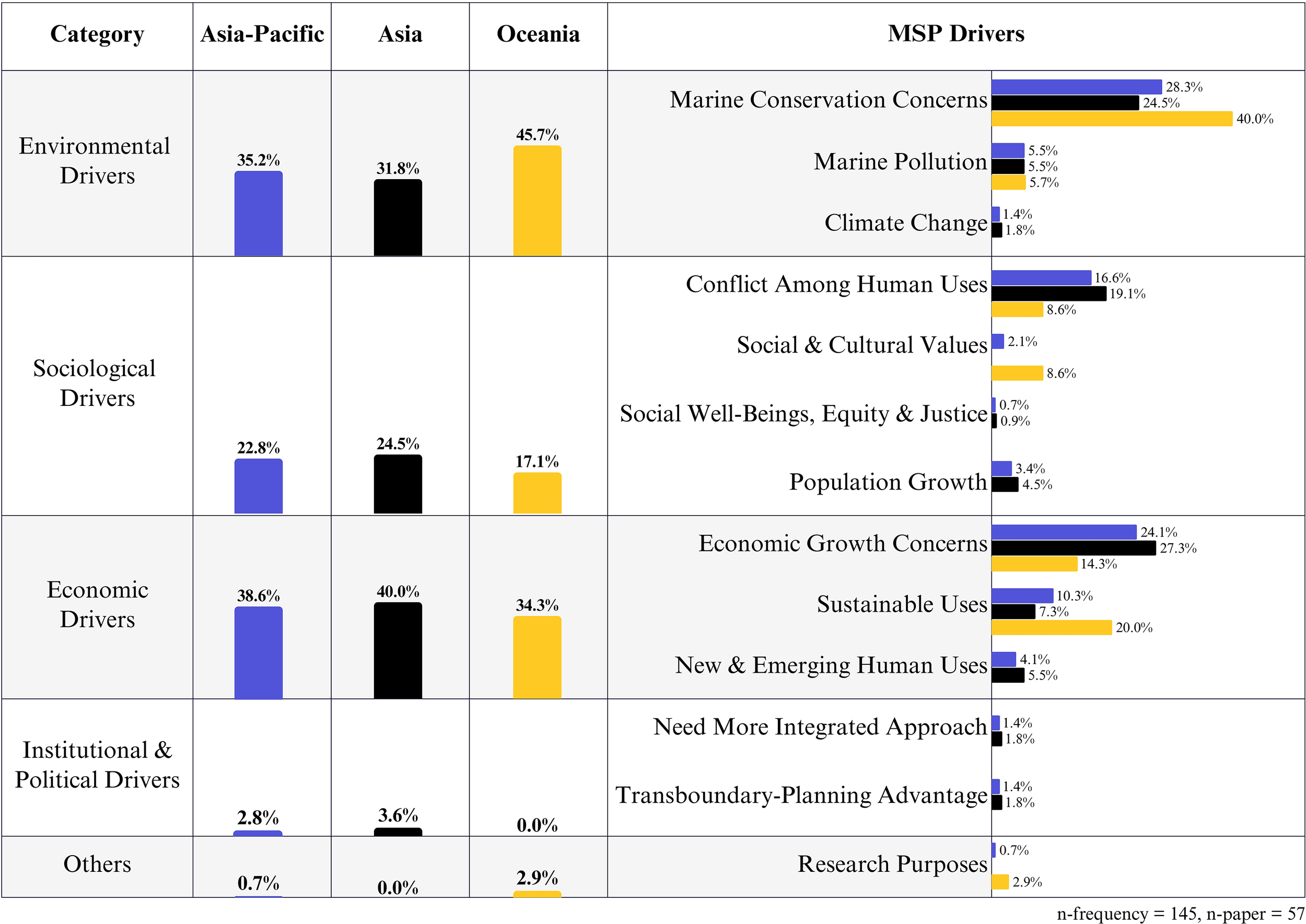

Content analysis revealed that economic drivers were the most frequently cited motivations for MSP implementation in the Asia-Pacific (38.6%), including economic growth (24.1%), sustainable use (10.3%), and new marine uses such as offshore aquaculture and energy (4.1%). (see Figure 2). Environmental drivers followed closely (35.2%), led by marine conservation (28.3%), with sociological drivers (22.8%) emphasizing user conflict and population pressures. Institutional, political, and research-related drivers were rarely mentioned (2.8% and <1%, respectively) (Wang et al., 2022a; Gacutan et al., 2022).

Figure 2

MSP drivers in Asia, Oceania, and the Asia-Pacific region.

Subregional comparisons showed a stark contrast. In Asia, MSP is predominantly motivated by economic growth (27.3%), with limited attention to climate change (1.8%), integrated approach (1.8%), transboundary-planning advantage (1.8% as referred to benefit from developing MSP between cities, provinces, and countries by Ma et al., 2023), equity (0.9%), and no references to socio-cultural or research-based drivers.

In contrast, Oceania emphasizes marine conservation (40%) and sustainable use (20%), particularly in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and Pacific Island nations where marine spaces are deeply embedded in cultural identity and local livelihoods (Domínguez-Tejo and Metternicht, 2018; Jarvis et al., 2015; Giffin et al., 2021).

MSP initiatives in Asia often focus on industrial development—transportation, fisheries, and tourism—reflecting growth-centered planning priorities (Ullah et al., 2021; Mannan et al., 2020). Meanwhile, Oceania’s more integrated approach uses MSP to balance conservation with socio-cultural preservation and long-term sustainability (Peart, 2019; Giffin et al., 2021).

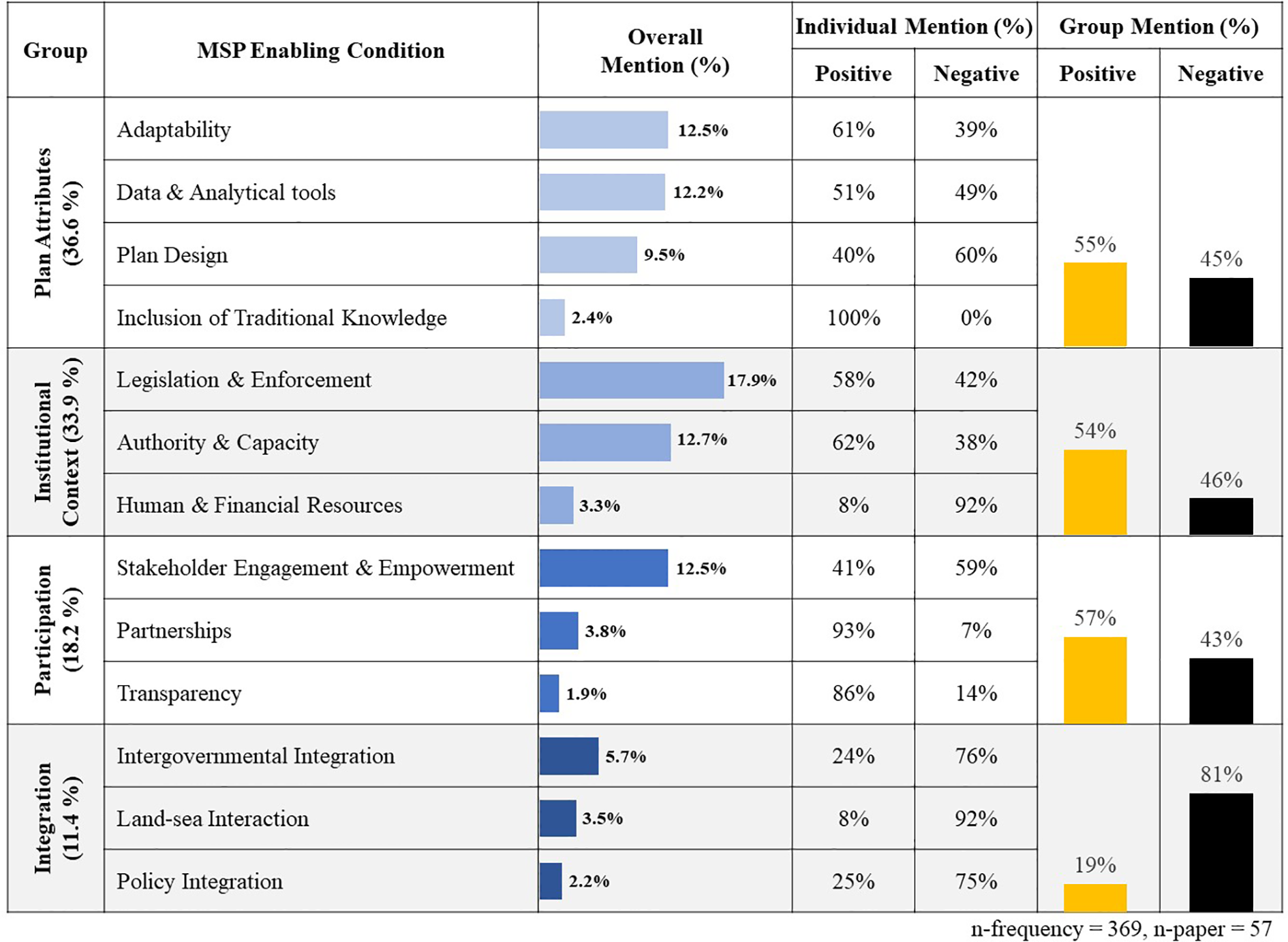

3.3 MSP enabling conditions

This study categorizes 13 enabling conditions into four thematic groups: (1) plan attributes, (2) institutional context, (3) participation, and (4) integration, following Ehler and Douvere (2009) and Zuercher et al. (2022b). Each condition influences the effectiveness of MSP—either as a positive contribution or as a barrier requiring attention. The results assess how often each condition is cited in the literature, distinguishing between enabling and hindering factors. Importantly, frequency does not imply relative importance; all identified conditions are essential for effective MSP.

Among the four groups, plan attributes accounted for 36.6% of mentions, followed by institutional context (33.9%), participation (18.2%), and integration (11.4%). Except for integration, all groups had more positive than negative references (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Enabling conditions in the Asia-Pacific region.

3.3.1 Plan attributes

This group includes four enabling conditions: adaptability, data and analytical tools, plan design, and inclusion of traditional knowledge. Overall, this group showed a nearly balanced distribution of positive (55%) and negative (45%) mentions (Figure 3).

3.3.1.1 Adaptability

Approximately 61% of the reviewed literature identified adaptability as a positive contributing factor. For instance, Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Project integrated climate resilience considerations into its planning framework (Chalastani et al., 2020). Several studies highlighted successful examples of adaptive planning, including MSP initiatives in Fiji, the Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea, where climate change impacts were explicitly addressed (Giffin et al., 2021). Similarly, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia applied a precautionary approach by incorporating future economic projections into the periodic evaluation and revision of its spatial plan (Gacutan et al., 2022; Domínguez-Tejo et al., 2016).

However, 39% of the literature highlighted concerns regarding the limited adaptability of MSP plans. In particular, China’s MSP was frequently cited as lacking a clear strategy to address climate change and a mechanism for integrating emerging issues into its management framework. Many studies emphasized the urgent need for adaptive management to respond to future changes (Teng et al., 2021; Yu and Li, 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Additionally, practical systems for monitoring and evaluation were found to be underdeveloped (Fang et al., 2011; Ullah et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2021; Wen et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022b). Fang et al. (2011) noted that performance monitoring for Marine Functional Zoning (MFZ) was often overlooked in practice, with revisions driven primarily by rapid economic growth rather than adaptive planning. Teng et al. (2021) further observed that updates to China’s National MFZ are excessively delayed, underscoring the need for more timely revisions.

3.3.1.2 Data and analytical tools

Data and analytical tools are widely recognized as critical contributors to successful MSP implementation worldwide. However, in the Asia-Pacific region, many countries are still in the early stages of technological advancement, and positive references to data and tool usage accounted for 51% of the literature. Some notable exceptions were found in island nations, where MSP development benefited from access to reliable data and decision-support tools. For instance, the Cham Islands and the Trao Reef Locally Managed Marine Area (LMMA) in Vietnam employed participatory mapping, 3D modeling, biodiversity surveys, ArcGIS, and MARXAN during plan development (Giffin et al., 2021). Similarly, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park was developed using the best available biophysical and socio-economic data (Kenchington and Day, 2011). The integration of standardized datasets enabled the incorporation of diverse forms of knowledge, including social values and traditional marine resource uses, through tools such as ArcGIS Pro and Social Network Visualizer (Domínguez-Tejo et al., 2016; Gacutan et al., 2022).

In Indonesia, the National MSP process emphasized the establishment of a centralized MSP database supported by a Spatial Decision Support System (SDSS). This effort was reinforced by a national spatial data infrastructure, legally formalized through Presidential Decree No. 85/2007 and updated in Decree No. 27/2014, providing a strong foundation for MSP implementation (Sutrisno et al., 2018).

Despite these advancements, 49% of the literature cited deficiencies in data availability and analytical capacity. Countries in the early stages of MSP development continue to face major challenges. For example, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) initiative in Pakistan highlighted the lack of baseline data and supporting technology necessary for MSP formulation (Ullah et al., 2017, 2021). In Bangladesh, insufficient data prevented the simulation of a comprehensive MSP database for the Bay of Bengal (Roy et al., 2022). Similarly, Thailand’s MSP process was hindered by fragmented and inconsistent data, limiting national-level planning (Gacutan et al., 2022).

3.3.1.3 Plan design

In the Asia-Pacific region, only 40% of the literature reviewed cited plan design as a positive contributing factor. One notable example is the Marine Functional Zoning (MFZ) in Xiamen, China, which was initially aligned with economic and social development goals. Through two rounds of revisions, the plan evolved to prioritize conservation, prohibiting industrial activities that conflicted with ecological objectives. Additionally, the marine protected area (MPA) in Xiamen is required to meet China’s first-class National Seawater Quality Standards (Fang et al., 2021). Another exemplary case is the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia, which applied an ecosystem-based approach that integrates environmental, social, and economic considerations with clearly defined objectives and operational principles. The plan’s design supports both feasibility and adaptability by monitoring external threats and pressures beyond MSP boundaries (Domínguez-Tejo et al., 2016; Kenchington and Day, 2011). While a well-designed MSP plan is essential, it does not guarantee successful outcomes due to various externalities and implementation challenges. Factors such as climate change (Zuercher et al., 2022b), data and monitoring issues (Flynn et al., 2023), human dimensions (Zuercher et al., 2022b; Charles and Wilson, 2009), enforcement (Wen et al., 2022), and the need for adaptive management (Reimer et al., 2023) play significant roles in determining the effectiveness of MSP. Addressing these challenges through comprehensive and adaptive approaches can help improve the outcomes of MSP initiatives.

However, 60% of the literature expressed concerns over inadequate or unbalanced plan design. In many Asian contexts, MSP initiatives tend to be heavily influenced by economic priorities. For instance, in Indonesia’s Karimunjawa National Park, zoning regulations were frequently adjusted to accommodate tourism, a major source of local income. This flexibility in favor of economic gain has resulted in significant damage to coral reefs and mangrove forests (Ramadhan et al., 2022). Similarly, in Wenzhou, China, the MFZ lacked effective coordination between marine uses and the area’s ecological carrying capacity. This resulted in overlapping zones and conflicts between development goals and marine sustainability (Ma et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2020). Furthermore, the MFZ framework has been criticized for its rigidity in adapting to emerging sectors such as offshore wind and ocean energy, limiting its responsiveness to evolving priorities (Yu et al., 2020).

3.3.1.4 Inclusion of traditional knowledge

Traditional knowledge was positively recognized in 100% of relevant cases, particularly in Oceania, yet remains absent from MSP planning across Asia.

Inclusion of traditional knowledge is increasingly acknowledged as a critical component in effective MSP design, especially in regions where communities maintain a close relationship with the marine environment. In island nations, this enabling condition received unanimous support in the literature. For instance, on Kaledupa Island in Sulawesi, Indonesia, local ecological knowledge was integrated into spatial planning (Szuster and Albasri, 2010). Similarly, the Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari plan for New Zealand’s Hauraki Gulf incorporated Mātauranga Māori—Indigenous knowledge systems—into the planning framework (Peart, 2019; Jarvis et al., 2015). Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park also integrated information from Aboriginal communities to support cultural and environmental stewardship (Domínguez-Tejo et al., 2016).

3.3.2 Institutional context

The results revealed a relatively balanced perception of institutional context, with 54% of mentions categorized as positive and 46% as negative. This group of enabling conditions comprised three key components: legislation and enforcement (17.9%), authority and capacity (12.7%), and human and financial resources (3.3%). While some progress has been made in establishing legal frameworks and building institutional capacity, the findings highlight ongoing challenges in governance structure, technical expertise, and resource availability across the region.

3.3.2.1 Legislation and enforcement

In the Asia-Pacific region, 58% of the literature viewed this factor positively, highlighting its significant contribution to successful MSP implementation. One prominent example is China’s national Marine Functional Zoning (MFZ), which is grounded in strong legal foundations such as the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration of the Use of Sea Areas. These legal instruments provide consistency and enforceability across coastal provinces, establishing MFZ as the national standard for regulating fisheries, transport, and industrial uses (Fang et al., 2021; Teng et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2020; Lin, 2023). Similarly, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is governed under a robust and well-defined legislative framework—the GBRMP Act—which supports ecosystem-based and integrated management across marine activities (Gacutan et al., 2022; Kenchington and Day, 2011).

However, 42% of the literature pointed to challenges in countries still at early stages of MSP development. Many lack clear, comprehensive legislation to guide MSP implementation. For example, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) initiative revealed that Pakistan lacks coherent maritime policies to support coastal and marine area protection or sea-use planning (Ullah et al., 2017, 2021) Similarly, in Bangladesh, the absence of a national MSP framework has hindered progress in sustainably managing the Bay of Bengal, a region in urgent need of coordinated marine governance (Mannan et al., 2020). Fragmented and overlapping legal systems further exacerbate these issues (Saha and Alam, 2018).

These legislative gaps often lead to unclear mandates and limited institutional capacity. For instance, Thailand continues to face challenges due to the absence of a formal lead agency to coordinate MSP efforts (Gacutan et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). In Pakistan, deficiencies in management capacity—ranging from limited scientific expertise to inadequate access to technology—also hamper effective MSP implementation (Ullah et al., 2021). Collectively, these weaknesses significantly obstruct the development and operationalization of MSP across the region.

While formal legislation is a common and often effective means of securing government commitment to MSP, it is not the only pathway. In several countries, progress has been achieved through alternative mechanisms, especially in the absence of dedicated MSP laws. These include leveraging existing sectoral legislation (Olsen et al., 2014), fostering stakeholder engagement (Wen et al., 2022; McGee et al., 2022), securing financial support (Hadjimitsis et al., 2015), demonstrating political will (Olsen et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2022; Reimer et al., 2023), and adopting collaborative governance models (Littaye et al., 2016). Such strategies can support institutional continuity and promote effective implementation, complementing formal legislative efforts where they exist—or providing viable alternatives where they do not.

3.3.2.2 Authority and capacity

Approximately 62% of the reviewed literature identified this factor as a positive contributor to MSP progress in several countries across the Asia-Pacific. For instance, China’s centralized governance structure has facilitated the coordination of its MFZ system through designated agencies at both national and provincial levels. Australia similarly demonstrated strong institutional capacity, with the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) effectively overseeing multi-sectoral planning and monitoring (Fang et al., 2021; Kenchington and Day, 2011). Additionally, Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Project employed interdisciplinary teams—including marine scientists, planners, and policy experts—to develop its MSP in line with national coastal development goals (Chalastani et al., 2020).

Despite these positive cases, 38% of the literature reported critical shortcomings in authority and capacity, particularly in countries with fragmented institutional structures or a lack of dedicated MSP agencies. In Thailand, for example, no formal lead agency has been assigned to drive the MSP process, resulting in weak coordination across ministries and jurisdictional overlaps (Gacutan et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Similarly, Pakistan continues to face significant barriers due to limited institutional experience, technical expertise, and inter-agency cooperation (Ullah et al., 2017, 2021).

3.3.2.3 Human and financial resources

This enabling condition relates to the availability of adequate staffing, technical expertise, and financial support necessary to plan, implement, and sustain MSP initiatives. It received the lowest percentage of positive mentions among institutional factors—only 8%—while 92% of the literature cited it as a major limitation across the Asia-Pacific region. One of the few positive examples comes from Israel’s MSP in the Mediterranean Sea, where substantial support from a philanthropic foundation enabled a well-funded and technically sound planning process (Portman, 2015).

Many countries lack dedicated funding mechanisms for MSP, relying heavily on short-term donor support or project-based financing. For example, national-level MSP initiatives in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Taiwan, and Thailand often face chronic underfunding, which undermines their ability to establish technical teams, conduct stakeholder engagement, or develop spatial data infrastructure (Liu et al., 2011; Wen et al., 2022; Ullah et al., 2021; Roy et al., 2022; Gacutan et al., 2022).

Human resource constraints are equally significant. Limited numbers of trained planners, marine scientists, and GIS specialists have been reported across developing nations in the region. Without long-term investment in professional development and institutional staffing, the implementation of MSP remains fragmented and reactive rather than strategic.

In contrast, a few countries have made progress. Indonesia, for instance, established a national MSP program supported by technical experts and a legal framework for spatial data management (Sutrisno et al., 2018). Yet, even in these cases, sustained financial and human resource support is essential for maintaining momentum and ensuring plan revision, monitoring, and enforcement over time.

3.3.3 Participation

Participation is a critical enabling condition that encompasses stakeholder engagement, empowerment, partnerships, and transparency throughout the MSP process. In the Asia-Pacific literature, this category accounted for 18.2% of total mentions, with a relatively balanced perception—57% positive and 43% negative.

Effective participation contributes to the legitimacy, equity, and resilience of marine planning efforts. It includes not only formal consultation but also meaningful involvement of coastal communities, indigenous peoples, and marginalized groups in decision-making.

The following sections explore three core components of participation as identified in the literature: stakeholder engagement and empowerment, partnerships, and transparency.

3.3.3.1 Stakeholder engagement and empowerment

Stakeholder engagement and empowerment refer to the active inclusion of diverse actors—such as local communities, fishers, Indigenous peoples, private sector representatives, and civil society organizations—in all phases of the MSP process. While this enabling condition was positively mentioned in 41% of the reviewed literature, the remaining 59% identified challenges in ensuring meaningful and inclusive participation.

Positive examples of stakeholder engagement were particularly evident in Pacific Island nations and countries with strong community-based traditions. In Fiji, New Zealand, and Indonesia, participatory approaches were central to MSP processes. For instance, New Zealand’s Hauraki Gulf initiative (Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari) integrated Māori perspectives through co-governance and culturally appropriate engagement mechanisms (Peart, 2019). Jarvis et al. (2015) further demonstrated that citizen science can contribute valuable environmental insights while enhancing public engagement by enabling communities to share observations and participate meaningfully in planning. In Vietnam, participatory mapping and stakeholder forums actively involved coastal communities in MSP development (Giffin et al., 2021). Similarly, the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security (CTI-CFF) prioritized inclusive engagement by bringing diverse stakeholders into the process while addressing challenges related to language barriers and differing institutional capacities through targeted training and capacity-building efforts (Kull et al., 2021).

However, in many cases—especially in centralized governance systems such as China and Saudi Arabia—stakeholder involvement was limited. Participation was often restricted to consultation stages, with little influence on decision-making. For example, China’s MFZ process and the Red Sea Project in Saudi Arabia were both criticized for top-down planning approaches that excluded local voices (Teng et al., 2021; Chalastani et al., 2020).

3.3.3.2 Partnerships

Partnership was highly regarded, receiving 93% positive mentions in the reviewed literature, indicating its strong contribution to effective MSP implementation.

Several case studies illustrate the importance of partnerships in advancing MSP goals. In Israel, MSP in the Mediterranean Sea was largely supported by philanthropic foundations and public–private stakeholders with interests in natural gas exploration (Portman, 2015). In China, the MFZ in Xiamen benefited from close collaboration with local scientific institutions, including Xiamen University and the Third Institute of Oceanography under the State Oceanic Administration. These partnerships provided critical scientific and technical expertise for plan development (Fang et al., 2021). Similarly, New Zealand’s Hauraki Gulf project was supported by the Environmental Defense Society, a not-for-profit organization that contributed to stakeholder engagement and policy analysis (Peart, 2019).

Despite the overwhelmingly positive assessment, 7% of the literature highlighted shortcomings in certain cases—particularly some MFZ initiatives in China—where partnerships were perceived as insufficient or lacking a broader scope for fostering collaboration and cross-jurisdictional cooperation (Yang et al., 2022).

3.3.3.3 Transparency

In the reviewed literature, 86% of mentions highlighted transparency as a positive element that enhanced legitimacy, stakeholder trust, and plan implementation.

A notable example is the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security (CTI-CFF), where six member countries collaborated to develop the Triangle Atlas—a shared geospatial platform for transboundary marine planning. This initiative exemplified high levels of openness and data sharing, contributing to regional cooperation and informed decision-making (Kull et al., 2021). Similarly, small Pacific Island nations such as Fiji, the Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea adopted transparent, participatory approaches that actively involved local communities in the design and execution of MSP plans (Giffin et al., 2021).

However, 14% of the literature raised concerns about inadequate transparency. In Taiwan, for instance, conflicts between offshore wind farm developers and local fishers were exacerbated by the lack of transparent communication and public engagement. Stakeholders expressed strong demand for more inclusive dialogue and clearer access to planning information (Zhang et al., 2017).

3.3.4 Integration

Integration is a critical enabling condition that ensures coherence across governance levels, spatial domains, and policy sectors. However, it was the weakest-performing group in this review, with only 19% positive mentions compared to 81% negative, indicating substantial challenges in the region. This group consists of three key dimensions: intergovernmental integration (5.7%), land–sea interaction (3.5%), and policy integration (2.2%), each of which plays a vital role in achieving ecosystem-based and cross-sectoral MSP.

3.3.4.1 Intergovernmental integration

This factor received only 24% positive mentions, indicating limited but notable progress in certain cases.

A strong example is the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security (CTI-CFF), in which six member countries—Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, the Solomon Islands, and Timor-Leste—demonstrated effective coordination under a shared Regional Plan of Action. The Regional Secretariat played a central role in facilitating communication and ensuring alignment of national efforts toward common goals (Kull et al., 2021). In China, the establishment of the Marine Management Coordination Committee was another positive step, aimed at resolving intersectoral conflicts and facilitating cooperation across government levels in response to competing marine development and conservation needs (Fang et al., 2021).

Despite these examples, 76% of the literature reflected negative experiences with intergovernmental integration. In China’s transboundary MFZ project involving Xiamen Bay, Meizhou Bay, and Xinghua Bay, persistent conflicts between agencies and jurisdictions were reported. Yang et al. (2022) emphasized the urgent need for cross-border collaboration and institutional mechanisms to address these challenges, especially between municipal and provincial governments. Similarly, in Taiwan, McAteer et al. (2022) identified frequent tensions between central and local authorities, highlighting the absence of executive-level coordination structures in MSP initiatives.

3.3.4.2 Land-sea interaction

Land–sea interaction is a critical aspect of MSP, recognizing that inland activities—such as agriculture, industrial operations, and urban development—have direct and often detrimental impacts on coastal and marine ecosystems. Despite its importance, this condition received limited attention in the literature, with only 8% of mentions reflecting positive integration efforts.

A notable example is Indonesia’s National MSP, specifically in Bontang City, East Kalimantan Province, which successfully incorporated land–sea linkages into its planning framework. The plan accounted for upstream land uses and their influence on marine areas, demonstrating a more integrated and holistic approach to coastal governance (Wen et al., 2022).

However, 92% of the literature highlighted deficiencies in addressing land–sea interactions. For instance, China’s MFZ in Xiamen and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park continue to experience significant inland pollution from sediment runoff, agricultural nutrients, and urban waste. In China, the MFZ system lacked mechanisms to control or mitigate land-based sources of pollution, resulting in long-standing degradation of adjacent marine environments (Hou et al., 2022; Fang et al., 2021).

3.3.4.3 Policy integration

Policy integration refers to the alignment and coordination of policies across diverse ocean-use sectors, aiming to address environmental, economic, and social objectives within a unified framework. It ensures that overlapping interests—such as fisheries, conservation, tourism, and coastal development—are managed in a coherent and mutually supportive manner.

Despite its importance, policy integration received a relatively low rate of positive mentions (25%) in the reviewed literature. One example of progress comes from Southern Taiwan, where the integration of spatial sea use management with terrestrial planning was formally recognized through the National Territorial Planning Act. This legislation became the country’s first integrated policy foundation for MSP, bridging offshore and inland concerns to reduce planning conflicts and mitigate land-based impacts on marine ecosystems (Lee et al., 2014).

Nevertheless, policy integration was one of the most frequently cited challenges, accounting for 75% of negative mentions. In Australia, the New South Wales Marine Estate project highlighted the fragmentation of jurisdictional boundaries and landscape governance, resulting in overlapping policies and regulatory inconsistencies (McAteer et al., 2022). A similar situation was reported in Malaysia’s Terengganu Marine Parks, where conflicting authority between federal and state governments led to uncoordinated management. This lack of integration contributed to significant pressures on coral reef systems, particularly in high-tourism areas. Interestingly, less-developed islands outside the formal MPA system, such as Pulau Bidong, were found to have healthier reef conditions than more heavily visited sites like the Perhentian Islands (Safuan et al., 2022).

4 Discussion: key challenges and lessons for global application

The findings of this review highlight that while MSP adoption is expanding across the Asia-Pacific, significant challenges persist that undermine its ability to deliver on sustainability and equity objectives. These challenges, though region-specific in manifestation, reflect broader governance, institutional, and operational issues relevant to MSP worldwide. Seven interrelated challenges were identified, along with lessons that can inform future MSP implementation globally.

4.1 Policy and governance complexity

Fragmented legal frameworks, overlapping mandates, and weak intergovernmental coordination remain major obstacles to effective MSP. Many countries in Asia lack comprehensive legislation or a designated lead agency to ensure coherence across jurisdictions. For instance, Thailand’s absence of a formal coordinating authority has resulted in disjointed planning efforts, while Pakistan and Bangladesh continue to operate without clear legal foundations for MSP (Gacutan et al., 2022; Mannan et al., 2020). Even in more advanced systems, such as Australia and China, jurisdictional overlaps and sectoral silos hinder integrated decision-making (McAteer et al., 2022; Fang et al., 2021). These findings underscore the need for harmonized governance frameworks and mechanisms that facilitate both vertical and horizontal integration.

4.2 Institutional capacity and resources

Institutional weakness is a recurring theme across the region. Chronic underfunding, limited technical infrastructure, and shortages of skilled personnel constrain the ability to design, implement, and monitor MSP effectively. Countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Thailand report severe gaps in financial resources and technical expertise (Ullah et al., 2021; Roy et al., 2022). In contrast, Australia and Indonesia illustrate the benefits of sustained investment in spatial data systems and trained professionals (Sutrisno et al., 2018; Kenchington and Day, 2011). Globally, long-term financing mechanisms, cross-sectoral training programs, and institutional capacity-building are prerequisites for MSP resilience.

4.3 Meaningful participation and inclusion

While stakeholder engagement is widely acknowledged as essential, practice often falls short. In many centralized governance contexts, participation remains tokenistic, with limited influence on decision-making. Examples from China and Saudi Arabia reveal top-down planning models that marginalize local voices (Teng et al., 2021; Chalastani et al., 2020). Conversely, Oceania demonstrates strong models of inclusive governance, such as New Zealand’s Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari, which institutionalizes Māori co-governance and community engagement (Peart, 2019). Moving forward, MSP must institutionalize the co-production of knowledge, incorporate traditional and local knowledge, and prioritize equity to enhance legitimacy (Pennino et al., 2021).

4.4 Monitoring, evaluation, and adaptation

Adaptive management—a core principle of MSP and ecosystem-based management (EBM)—is rarely operationalized in the region. Monitoring systems are often underdeveloped, with revisions typically driven by economic rather than ecological indicators (Fang et al., 2011; Teng et al., 2021). By contrast, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park demonstrates how structured evaluation linked to ecological thresholds can enhance resilience (Domínguez-Tejo et al., 2016). Embedding robust monitoring and adaptive mechanisms into MSP is critical to respond to dynamic marine and socio-economic conditions globally.

4.5 Integration across scales and sectors

Integration—across governance levels, land–sea interfaces, and policy domains—emerged as the weakest enabling condition in this review. Persistent fragmentation undermines the holistic approach required for ecosystem-based MSP. While Taiwan’s National Territorial Planning Act offers a promising model for land–sea policy integration, most countries lack coherent frameworks (Lee et al., 2014). Similarly, intergovernmental coordination failures were documented in China’s multi-jurisdictional MFZ projects and Australia’s New South Wales Marine Estate (Yang et al., 2022; McAteer et al., 2022). To address this, MSP must establish institutional mechanisms for vertical and horizontal integration and align sectoral policies to prevent conflicting mandates.

4.6 Climate change and emerging pressures

Despite the Asia-Pacific’s vulnerability to climate-driven risks—such as sea-level rise and extreme weather—climate resilience is rarely a central feature of MSP frameworks. Adaptation strategies and scenario-based planning remain underdeveloped, particularly in Asia (Teng et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2020). By contrast, Oceania and Australia provide examples of incorporating climate adaptation into MSP design (Giffin et al., 2021). Globally, MSP must mainstream climate change adaptation and account for cumulative and emerging pressures, such as offshore energy development, to safeguard ocean resilience.

4.7 Reinforcing the EBM–MSP nexus

MSP was conceived as a tool to operationalize EBM, yet its application often remains rhetorical. In many contexts, MSP functions as a spatial allocation mechanism rather than an integrated ecosystem management strategy (Ehler and Douvere, 2009). MSP is regarded as one of the most pragmatic tools to advance EBM (ESCAP, 2019; Rezaei et al., 2024). The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD, 1998) and Hammer (2023) emphasize that all 12 EBM principles must be applied collectively, including adaptive management, stakeholder participation, and precautionary approaches. Successful models—such as the Great Barrier Reef and New Zealand’s Hauraki Gulf Plan—illustrate how EBM-based MSP can maintain ecological thresholds while accommodating socio-economic objectives (Peart, 2019; Domínguez-Tejo et al., 2016). Strengthening this nexus globally requires embedding EBM principles into national legislation, performance indicators, and adaptive governance mechanisms.

5 Conclusion

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) in the Asia-Pacific reflects contrasting trajectories shaped by diverse political, institutional, and socio-cultural contexts. While Oceania demonstrates more holistic approaches grounded in sustainability and traditional knowledge, much of Asia remains dominated by growth-oriented agendas with limited integration of ecological and social objectives. Among the enabling conditions, progress was noted in plan attributes and institutional frameworks, yet persistent weaknesses in adaptive capacity, data systems, and stakeholder engagement undermine effectiveness. Integration emerged as the most critical gap, particularly in intergovernmental coordination, land–sea connectivity, and policy coherence.

Strengthening MSP requires a systemic shift beyond incremental improvements toward operationalizing ecosystem-based management (EBM) as a guiding principle. This entails embedding ecological thresholds into spatial decisions, institutionalizing inclusive participation, and adopting adaptive mechanisms for climate resilience. Addressing institutional fragmentation, chronic resource constraints, and tokenistic participation is vital to ensure equity, sustainability, and resilience. Lessons from the Asia-Pacific carry global relevance: advancing MSP as a transformative governance framework demands alignment with global commitments such as SDG 14 and the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.

6 Policy and research implications

Policymakers should prioritize legal harmonization, sustainable financing, and inter-agency coordination to strengthen governance coherence. Investment in capacity building, robust data infrastructure, and inclusive participatory mechanisms will be essential for implementation success. Future research should focus on developing measurable indicators for ecosystem-based outcomes, evaluating adaptive governance models, and exploring the co-production of knowledge across diverse cultural contexts. These actions will be critical for positioning MSP as a credible tool to achieve resilient, equitable, and ecologically sound marine futures globally. A summary of policy and research implications is provided in Table 3.

Table 3

| Dimension | Policy implication | Research implications |

|---|---|---|

| Governance & Policy | • Harmonize fragmented legal frameworks across sectors and levels of government • Establish clear institutional mandates and strengthen inter-agency coordination. |

• Assess the effectiveness of multi-level governance models in MSP. • Explore legal innovations for integrated marine and land planning. |

| Institutional Capacity |

|

• Develop frameworks for capacity assessment and adaptive governance under resource constraints |

| Participation & Inclusion | • Institutionalize mechanisms for meaningful participation beyond tokenistic consultation. • Incorporate Indigenous and local knowledge into MSP processes. |

• Examine best practices for knowledge co-production in culturally diverse contexts. |

| Integration & EBM | • Embed ecosystem-based management (EBM) principles in MSP through ecological thresholds and cross-sectoral policy alignment. | • Develop measurable indicators to monitor EBM outcomes and socio-ecological resilience. |

| Data & Monitoring | • Establish standardized spatial data infrastructures and promote open data sharing. • Implement adaptive monitoring and evaluation systems. |

• Innovate decision-support tools integrating ecological, social, and economic datasets for MSP |

| Climate Change & Resilience | • Mainstream climate adaptation strategies into MSP design and implementation. | • Investigate climate-resilient MSP models and scenario-based adaptive planning tools. |

Details of Policy and Research Implications.

7 Limitations

This study is subject to several important limitations. Due to government budget constraints, access to the Web of Science database was unavailable during the study period; therefore, the review relied solely on peer-reviewed publications indexed in the Scopus database between 2003 and 2023. In addition, the exclusion of non-English publications may have underrepresented national experiences, particularly from countries where significant Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) efforts are documented in domestic languages. Grey literature—such as MSP strategies, implementation reports, and policy documents—was also excluded, which may limit practical insights into real-time implementation and practitioner perspectives. Taken together, these limitations mean that the findings should be interpreted as a partial representation of the Asia-Pacific region, and future research would benefit from a complementary qualitative review incorporating grey literature and practitioner experiences to bridge the gap between academic discourse and on-the-ground implementation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

SS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KC: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. TP: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. SP: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZZ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We gratefully acknowledge the funding support provided by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) for this work, under the project Marine Spatial Planning: Application to Local Practices (2022–2023).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Artificial intelligence assistance (ChatGPT) was used to support improvements in language clarity, coherence, and overall presentation of the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1659088/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Chalastani V. I. Manetos P. Al-Suwailem A. M. Hale J. A. Vijayan A. P. Pagano J. et al . (2020). Reconciling tourism development and conservation outcomes through marine spatial planning for a Saudi Giga-project in the red sea (The red sea project, vision 2030). Front. Mar. Sci.7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00168

2

Charles A. Wilson L. (2009). Human dimensions of marine protected areas. ICES J. Mar. Sci.66, 6–15. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsn182

3

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (1998). Report of the workshop on the ecosystem approach. Report No. UNEP/CBD/COP/4/Inf.9. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/cop/cop-04/information/cop-04-inf-09-en.pdf

4

Domínguez-Tejo E. Metternicht G. (2018). Poorly-designed goals and objectives in resource management plans: Assessing their impact for an Ecosystem-Based Approach to Marine Spatial Planning. Mar. Policy88, 122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.013

5

Domínguez-Tejo E. Metternicht G. Johnston E. Hedge L. (2016). Marine Spatial Planning advancing the Ecosystem-Based Approach to coastal zone management: A review. Mar. Policy72, 115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.06.023

6

Ehler C. N. (2021). Two decades of progress in Marine Spatial Planning. Mar. Policy132, 104134. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104134

7

Ehler C. N. Douvere F. (2009). “ Marine spatial planning: a step-by-step approach toward ecosystem-based management,” in Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and Man and the Biosphere Programme, IOC Manual and Guides No. 53, ICAM Dossier No. 6 ( UNESCO, Paris).

8

Elrick-Barr C. E. Zimmerhackel J. S. Hill G. Clifton J. Ackermann F. Burton M. et al . (2022). Man-made structures in the marine environment: A review of stakeholders’ social and economic values and perceptions. Environ. Sci. Policy129, 12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2021.12.006

9

ESCAP (2019). Asia-Pacific marine spatial planning snapshot 2009-2019. Available online at: https://stat-confluence.escap.un.org/download/attachments/16154828/08.01.04%20ESCAP_OceanAccounts_PreliminaryStudy_Asia-PacificMSPSnapshot2009-2010.pdf?version=1&modificationDate=1610433680611&api=v2.

10

Fang Q. Ma D. Zhang L. Zhu S. (2021). Marine functional zoning: A practical approach for integrated coastal management (ICM) in Xiamen. Ocean Coast. Manage. 207, 104433. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.03.004

11

Fang Q. Zhang R. Zhang L. Hong H. (2011). Marine functional zoning in China: experience and prospects. Coast. Manage.39, 656–667. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2011.616678

12

Ferro-Azcona H. Espinoza-Tenorio A. Calderón-Contreras R. Ramenzoni V. C. Gómez País M. M. Mesa-Jurado A. Z. (2019). Adaptive capacity and social-ecological resilience of coastal areas: A systematic review. Ocean Coast. Manage.173, 36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.01.005

13

Flynn S. Tray E. Woolley T. Leadbetter A. Heney K. O’Driscoll D. et al . (2023). Management of spatial data integrity including stakeholder feedback in Maritime Spatial Planning. Mar. Policy156, 105799. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105799

14

Foley M. M. Halpern B. S. Micheli F. Armsby M. H. Caldwell M. R. Crain C. M. et al . (2010). Guiding ecological principles for marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy34, 955–966. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2010.02.001

15

Fu X.-M. Liu G.-J. Liu Y. Xue Z.-K. Chen Z. Jiang S.-S. et al . (2021). Evaluation of the implementation of marine functional zoning in China based on the PSR-AHP model. Ocean Coast. Manage.203, 105496. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105496

16

Gacutan J. Pınarbaşı K. Agbaglah M. Bradley C. Galparsoro I. Murillas A. et al . (2022). The emerging intersection between marine spatial planning and ocean accounting: A global review and case studies. Mar. Policy140, 105055. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105055

17

Giffin A. L. Brown C. J. Nalau J. Mackey B. G. Connolly R. M. (2021). Marine and coastal ecosystem-based adaptation in Asia and Oceania: review of approaches and integration with marine spatial planning. Pacific Conserv. Biol.27, 104. doi: 10.1071/pc20025

18

Hadjimitsis D. Agapiou A. Mettas C. Themistocleous K. Evagorou E. Cuca B. et al . (2015). “ Marine spatial planning in Cyprus,” in Proceedings of SPIE – The International Society for Optical Engineering: Third International Conference on Remote Sensing and Geoinformation of the Environment (RSCy2015), Bellingham, WA: SPIE. Proceedings Vol. 9535, 953511. doi: 10.1117/12.2195655

19

Hammer M. (2023). Lost in translation – Following the ecosystem approach from Malawi to the Barents Sea. Arctic Rev. Law Politics14, 46–69. doi: 10.23865/arctic.v14.5482

20

Hou Y. Xue X. Liu C. Xin F. Lin Y. Wang S. (2022). Marine Spatial Planning Scheme evaluation based on the conflict analysis system - A case study in Xiamen, China. Ocean Coast. Manage.221, 106119. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106119

21

IOC-UNESCO (2022). Marine spatial planning ( Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO). Available online at: https://www.ioc.unesco.org/en/marine-spatial-planning.

22

IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services ( IPBES Secretariat).

23

Jarvis R. M. Bollard Breen B. Krägeloh C. U. Billington D. R. (2015). Citizen science and the power of public participation in marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy57, 21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.011

24

Jay S. Flannery W. Vince J. Liu W. H. E. Xue J. G. Matczak M. et al . (2013). International progress in marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy39, 182–192. doi: 10.1163/22116001-90000159

25

Katsanevakis S. Stelzenmüller V. South A. Sørensen T. K. Jones P. J. S. Kerr S. et al . (2011). Ecosystem-based marine spatial management: Review of concepts, policies, tools, and critical issues. Ocean Coast. Manage.54, 807–820. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.09.002

26

Kenchington R. A. Day J. C. (2011). Zoning, a fundamental cornerstone of effective Marine Spatial Planning: lessons learnt from the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. J. Coast. Conserv.15, 271–278. doi: 10.1007/s11852-011-0147-2

27

Kull M. Moodie J. Thomas H. Méndez-Roldán S. Giacometti A. Morf A. et al . (2021). International good practices for facilitating transboundary collaboration in Marine Spatial Planning. Mar. Policy132, 103492. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.03.005

28

Lee M.-T. Wu C.-C. Ho C.-H. Liu W.-H. (2014). Towards marine spatial planning in southern Taiwan. Sustainability6, 8466–8484. doi: 10.3390/su6128466

29

Lin Z. (2023). Chinese legislation on protection of underwater cultural heritage in marine spatial planning and its implementation. Int. J. Cultural Policy29(4), 500–517. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2022.2080201

30

Littaye A. Lardon S. Alloncle N. (2016). Stakeholders’ collective drawing reveals significant differences in the vision of marine spatial planning of the western tropical Pacific. Ocean Coast. Manage.130, 260–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.06.012

31

Liu W.-H. Wu C.-C. Jhan H.-T. Ho C.-H. (2011). The role of local Government in marine spatial planning and management in Taiwan. Mar. Policy35, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2010.08.006

32

Ma C. Stelzenmüller V. Rehren J. Yu J. Zhang Z. Zheng H. et al . (2023). A risk-based approach to cumulative effects assessment for large marine ecosystems to support transboundary marine spatial planning: A case study of the yellow sea. J. Environ. Manage.342, 118165. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118165

33

Ma R. Ji S. Ma J. Shao Z. Zhu B. Ren L. et al . (2022). Exploring resource and environmental carrying capacity and suitability for use in marine spatial planning: A case study of Wenzhou, China. Ocean Coast. Manage.226, 106258–106258. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106258

34

Mannan S. Nilsson H. Johansson T. Schofield C. (2020). Enabling stakeholder participation in marine spatial planning: the Bangladesh experience. J. Indian Ocean Region16(3), 268–291. doi: 10.1080/19480881.2020.1825200

35

McAteer B. Fullbrook L. Liu W.-H. Reed J. Rivers N. Vaidianu N. et al . (2022). Marine spatial planning in regional ocean areas: trends and lessons learned. Ocean Yearbook Online36, 346–380. doi: 10.1163/22116001-03601013

36

McGee G. Byington J. Bones J. Cargill S. Dickinson M. Wozniak K. et al . (2022). Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast: Engagement and communication with stakeholders and the public. Mar. Policy142, 104613. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.104613

37

McLeod E. Shaver E. C. Beger M. Koss J. Grimsditch G. (2021). Using resilience assessments to inform the management and conservation of coral reef ecosystems. J. Environ. Manage.277, 111384. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111384

38

Olsen E. Fluharty D. Hoel A. H. Hostens K. Maes F. Pecceu E. (2014). Integration at the round table: marine spatial planning in multi-stakeholder settings. PloS One9, e109964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109964

39

Peart R. (2019). Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari: addressing catchment and marine issues in an integrated marine spatial planning process. Aquat. Conservation: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst.29, 1561–1573. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3156

40

Pennino M. G. Brodie S. Frainer A. Lopes P. F. M. Lopez J. Ortega-Cisneros K. et al . (2021). The missing layers: Integrating sociocultural values into marine spatial planning. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.633198

41

Pittman J. Armitage D. (2016). Governance across the land-sea interface: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Policy64, 9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2016.05.022

42

Portman M. E. (2015). Marine spatial planning in the Middle East: Crossing the policy-planning divide. Mar. Policy61, 8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.06.025

43

Ramadhan A. Salim W. A. Argo T. A. Prihatiningsih P. (2022). The human dimension dilemma in marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy146, 105297. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105297

44

Reimer J. M. Devillers R. Zuercher R. Seif E. Kiener M. Pomeroy R. et al . (2023). The Marine Spatial Planning Index: A tool to guide and assess marine spatial planning. NPJ Ocean Sustainability2, 15. doi: 10.1038/s44183-023-00022-w

45

Rezaei F. Contestabile P. Vicinanza D. Azzellin A. Weiss C. V. C. Juane J. (2024). Soft vs. hard sustainability approach in marine spatial planning: Challenges and solutions. Water16, 1382. doi: 10.3390/w16101382

46

Roy S. Hossain M. S. Badhon M. K. Chowdhury S. U. Sumaiya N. Depellegrin D. (2022). Development and analysis of a geospatial database for maritime spatial planning in Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manage.317, 115495. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115495

47

Safuan C. D. M. Aziz N. Md Repin I. Xue X.-Z. Muhammad Ashraf A. R. Bachok Z. et al . (2022). Assessment of governance and ecological status of Terengganu Marine Park, Malaysia: Toward marine spatial planning. Sains Malaysiana51, 3909–3922. doi: 10.17576/jsm-2022-5112-04

48

Saha K. Alam A. (2018). Planning for blue economy: prospects of maritime spatial planning in Bangladesh. AIUB J. Sci. Eng. (AJSE)17, 59–66. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4427726

49

Satumanatpan S. Plathong S. Zhang Z. (2023). Marine Spatial Planning Project: Application to Local Practice (Bangkok, Thailand: National Research Council of Thailand).

50

Sutrisno D. Gill S. N. Suseno S. (2018). The development of spatial decision support system tool for marine spatial planning. Int. J. Digital Earth11, 863–879. doi: 10.1080/17538947.2017.1363825

51

Szuster B. W. Albasri H. (2010). Mariculture and marine spatial planning: integrating local ecological knowledge at Kaledupa Island, Indonesia. Island Stud. J.5, 237–250. doi: 10.24043/isj.246

52

Teng X. Zhao Q. Zhang P. Liang L. Dong Y. Heng H. et al . (2021). Implementing marine functional zoning in China. Mar. Policy132, 103484. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.02.055

53

Ullah Z. Wu W. Guo P. Yu J. (2017). A study on the development of marine functional zoning in China and its guiding principles for Pakistan. Ocean Coast. Manage.144, 40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.04.017

54

Ullah Z. Wu W. Wang X. H. Pavase T. R. Hussain Shah S. B. Pervez R. (2021). Implementation of a marine spatial planning approach in Pakistan: An analysis of the benefits of an integrated approach to coastal and marine management. Ocean Coast. Manage.205, 105545. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105545

55

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) (2020). Protected Planet Report 2020 (Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC).

56

UNESCO/European Commission (2021). MSP global International Guide on Marine / Marine Spatial Planniong (Paris: UNSECO). IOC Manual and Guides no 89.

57

Wang S. Liu C. Hou Y. Xue X. (2022a). Incentive policies for transboundary marine spatial planning: An evolutionary game theory-based analysis. J. Environ. Manage.312, 114905. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114905

58

Wang J. Yang X. Wang Z. Ge D. Kang J. (2022b). Monitoring marine aquaculture and implications for marine spatial planning—An example from Shandong Province, China. Remote Sens.14, 732. doi: 10.3390/rs14030732

59

Wen W. Samudera K. Adrianto L. Johnson G. L. Brancato M. S. White A. (2022). Towards marine spatial planning implementation in Indonesia: progress and hindering factors. Coast. Manage.50, 469–489. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2022.2126262

60

Yang S. Fang Q. Ikhumhen H. O. Meilana L. Zhu S. (2022). Marine spatial planning for transboundary issues in bays of Fujian, China: A hierarchical system. Ecol. Indic.136, 108622. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108622

61

Yu J.-K. Li Y.-H. (2020). Evolution of marine spatial planning policies for mariculture in China: Overview, experience and prospects. Ocean Coast. Manage.196, 105293. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105293

62

Yu J.-K. Ma J.-Q. Liu D. (2020). Historical evolution of marine functional zoning in China since its reform and opening up in 1978. Ocean Coast. Manage.189, 105157. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105157

63

Zhang Z. Plathong S. Sun Y. Guo Z. Ma C. Jantharakhantee C. et al . (2022). An issue-oriented framework for Marine Spatial Planning—A case study of Koh Lan, Thailand. Regional Stud. Mar. Sci.53, 102458. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2022.102458

64

Zhang Y. Zhang C. Chang Y.-C. Lin Y.-C. (2017). Offshore wind farm in marine spatial planning and the stakeholders' engagement: Opportunities and challenges for Taiwan. Ocean Coast. Manage.149, 69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.09.014

65

Zuercher R. Ban N. C. Flannery W. Guerry A. D. Halpern B. S. Magris R. A. et al . (2022b). Enabling conditions for effective marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy143, 105141. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105141

66

Zuercher R. Motzer N. Magris R. A. Flannery W. (2022a). Narrowing the gap between marine spatial planning aspirations and realities. Ices J. Mar. Sci.79, 600–608. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsac009

Summary

Keywords

marine spatial planning (MSP), Asia-Pacific, ecosystem-based management (EBM), ocean governance, stakeholder participation, climate resilience

Citation

Satumanatpan S, Chuenwongarun K, Piyawongnarat T, Plathong S and Zhang Z (2025) Pathways in marine spatial planning: a systematic review of drivers and enabling conditions in the Asia-Pacific. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1659088. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1659088

Received

03 July 2025

Revised

07 October 2025

Accepted

19 November 2025

Published

03 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Samiya Ahmed Selim, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, Bangladesh

Reviewed by

Joseph Onwona Ansong, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

Fatemeh Rezaei, Università degli Studi della Campania L. Vanvitelli, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Satumanatpan, Chuenwongarun, Piyawongnarat, Plathong and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Suvaluck Satumanatpan, suvaluck.nat@mahidol.ac.th

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.