Abstract

Introduction:

The sea urchin Diadema africanum, a key herbivore shaping shallow benthic ecosystems of the Canary Islands, has experienced recurrent mass mortality events (MMEs) in recent years. This study provides the first comprehensive assessment of the extent and ecological consequences of the 2022–2023 MME across the archipelago.

Methods:

Information was compiled from citizen science reports, visual censuses of adult populations, and larval settlement surveys using artificial collectors and visual observations. Additionally, oceanographic data were analyzed to explore potential environmental drivers of the event.

Results:

Citizen science observations revealed widespread mortality across nearly all islands, originating in the westernmost islands (La Gomera and La Palma) and spreading eastward. Visual censuses indicated severe population collapses, with adult densities decreasing by 73.8% in La Palma and 99.66% in Tenerife relative to 2021 levels—the lowest densities recorded since monitoring began. Settlement surveys in Tenerife showed a total recruitment failure in 2023, with no settlers detected in collectors and no recruits observed during visual inspections four months after the typical settlement peak.

Discussion:

Preliminary oceanographic analyses suggest that prolonged eastward currents and anomalous high-energy southern swells may have facilitated the initial outbreaks. The timing of this MME coincides with other Diadematid die-offs worldwide, suggesting that the Canary Islands could represent a connecting node in a potential transoceanic marine pandemic. The unprecedented population collapse and recruitment failure point to a profound disruption of the species’ life cycle, raising serious concerns about its persistence in the region and its cascading effects on ecosystem structure and function.

1 Introduction

Diadema represent a genus of sea urchins that typically play a crucial role in shallow benthic ecosystems of tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions. Their significance lies in their ability to regulate algal biomass and growth through herbivory (Sammarco, 1982; Sangil et al., 2014; Ishikawa et al., 2016; Do Hung Dang et al., 2020). This genus is considered a boom-bust taxon, capable of reaching high population densities, which in turn, can alter entire habitats, overall reducing biodiversity (Uthicke et al., 2009). Conversely, at moderate densities, these sea urchins can also create space for slow-growing organisms such as coral, potentially providing high structural complexity to the ecosystem, subsequently driving elevated diversity. This equilibrium between macroalgae abundance and diadematid sea urchin densities is generally not linear, with drastic shifts from algae-dominated environments to barren areas when the urchin populations grow beyond certain thresholds (Ling et al., 2015). This critical population density is usually greater than the number of sea urchins required to sustain an overgrazed rocky seafloor, making these alternative states able to persist over decades, due to the establishment of positive feedbacks (Scheffer and Carpenter, 2003; Hernández et al., 2008a; Baskett and Salomon, 2010).

In the Canary Islands, the sea urchin Diadema africanum (Rodríguez et al., 2013) is considered the main grazer of the archipelago in shallow rocky bottoms between 5-to-40-meter depth (Hernández et al., 2008a). This echinoid has been responsible for promoting and maintaining impoverished barren states since, at least, 1965, when the first large aggregations were observed (Johnston, 1969). Since then, D. africanum populations have been showing a consistent increase in the Canaries, probably due to the depletion of its main predators and gradual increase in sea surface temperature (SST), which are correlated with higher settlement rates of this species (Hernández et al., 2008b, 2010; Hernández, 2017). This situation prompted local authorities to develop sea urchin eradication campaigns that showed limited long-term success (Hernández, 2017).

Barren grounds in the Canary Islands showed no signs of Diadema decline until March 2010, when a disease caused an average 60% reduction in D. africanum off La Palma and Tenerife; with symptoms such as tissue and spine loss matching the “bald sea urchin disease” (Clemente et al., 2014; Feehan and Scheibling, 2014; Sweet, 2020). The MME was attributed to a synergism between Neoparamoeba branchiphila and Vibrio alginolyticus, the latter potentially acting opportunistically (Dyková et al., 2011; Clemente et al., 2014; Hernández et al., 2020a). Despite the event, recruitment remained largely unaffected, and populations recovered, except in La Palma (Clemente et al., 2014; Hernández et al., 2020a). A recurrent MME was later detected in February 2018 causing ~93% D. africanum reductions in La Palma and Tenerife. The effects of this MME were also noted in citizen science, extending reports of mortalities to Gran Canaria, Lanzarote, and Fuerteventura (Hernández et al., 2020a). A similar scale of mortalities (~90%) were also detected in Madeira (Gizzi et al., 2020). Symptoms resembled those of 2010, however, only Paramoeba brachipilla, a paramoebaean typically found in stable marine sediments, was isolated (Nowak and Archibald, 2018; Salazar-Forero et al., 2022). This event has been linked to “killer storm” dynamics associated with the atypical SW storm Emma, which resuspended sediments and enhanced vertical mixing, likely transporting amoebae into the water column (Hernández et al., 2020a), a process also documented in other sea urchin MMEs (Scheibling and Lauzon-Guay, 2010; Feehan et al., 2012). The resulting decimation of D. africanum populations prompted wide-scale phase shifts from barrens to macroalgal beds when sea urchin densities fell below ~4 ind/m² (Sangil and Hernández, 2022).

Nevertheless, despite the severity of the 2018 MME, D. africanum refuge populations appear to persist, as evidenced by the successful settlement observed on the eastern coast of Tenerife Island in subsequent years (Méndez-Álvarez, 2021; Cano et al., 2024). Nevertheless, several locations off the island showed no indications of Diadema reappearance, suggesting that ecosystem feedbacks could have been hindering D. africanum recovery (Sangil and Hernández, 2022). In contrast, off Madeira Island, D. africanum populations demonstrated a surprisingly fast recovery following the 2018 MME (Gizzi et al., 2020).

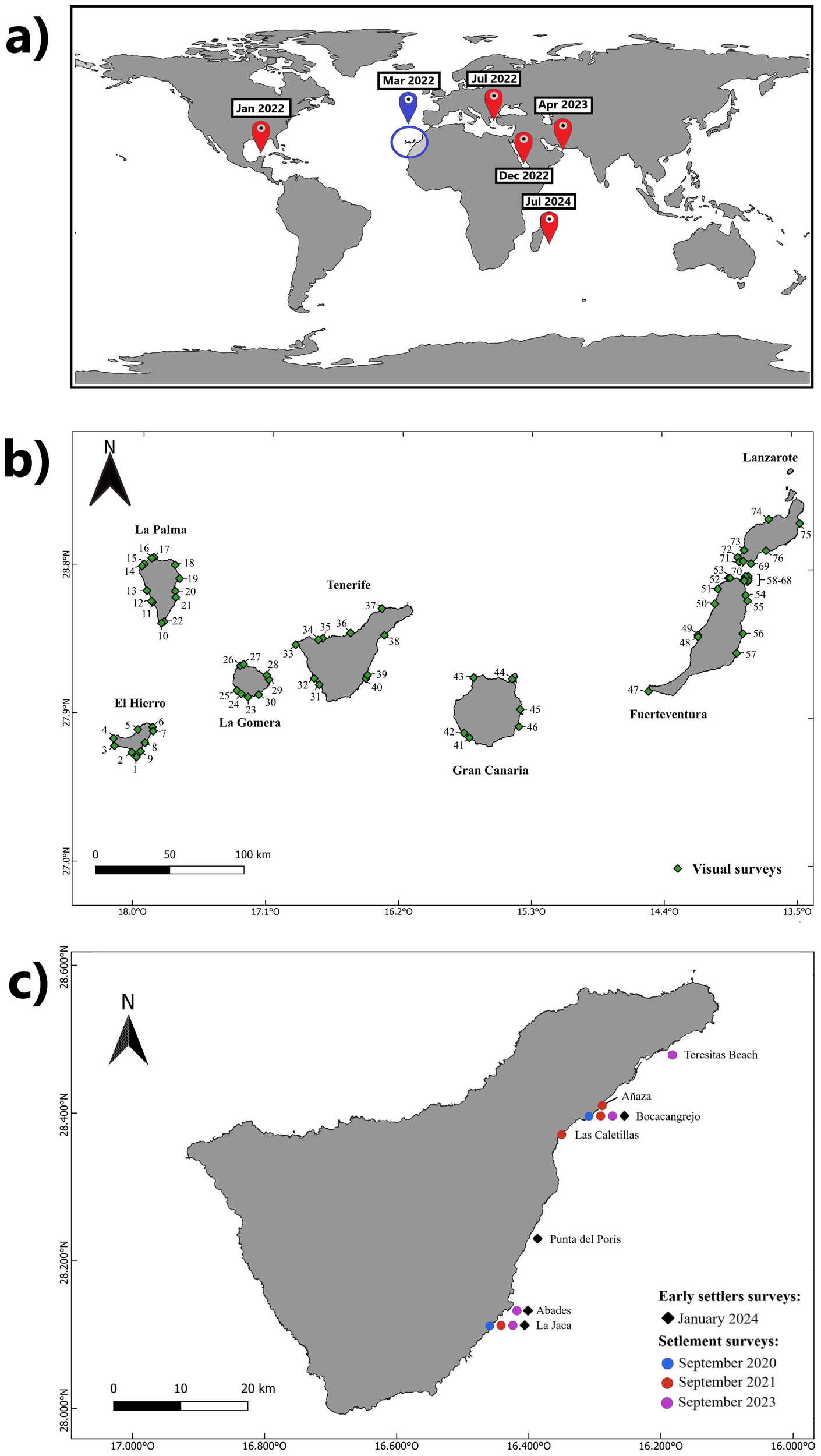

In March 2022, a new D. africanum MME was detected in La Gomera. This event coincided with other diadematoid MMEs globally, including the mortality of D. antillarum in the Caribbean in January 2022 (Hylkema et al., 2023), D. setosum in the Mediterranean Sea in July 2022 (Zirler et al., 2023; Dinçtürk et al., 2024; Demircan et al., 2025), Echinothrix calamaris and D. setosum in the Red Sea in December 2022 (Roth et al., 2024), D. setosum in the Sea of Oman in April 2023 (Ritchie et al., 2023), and Echinothrix diadema and E. calamaris off the Réunion Island in July 2024 (Quod et al., 2024) (Figure 1a).

Figure 1

Map of (a) Global spread of diadematids mass mortalities since 2022. In blue, the location of mortalities in the Canarian archipelago, in red – previously reported mass mortality events, (b) the Canary Islands showing the locations where visual surveys were conducted and (c) Tenerife Island showing the locations and dates where settlement and recruitment surveys were conducted.

Experimental infections in D. antillarum demonstrated that a scuticociliate most similar to Philaster apodigitiformis was the causative agent of the 2022 Caribbean mortality event. This conclusion was supported by the consistent presence of the ciliate in abnormal urchins from affected sites and its absence in unaffected ones, the reproduction of characteristic disease signs following experimental challenge of naïve urchins with a culture isolated from a diseased specimen, and the subsequent re-isolation of the same organism from experimentally infected individuals, thereby fulfilling Koch’s postulates (Hewson et al., 2023). Molecular diagnostics detected the same waterborne scuticociliate protozoan in diseased specimens from the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, the Sea of Oman, and Réunion Island (Ritchie et al., 2023; Roth et al., 2024; Quod et al., 2024; Demircan et al., 2025). Additionally, in the Mediterranean Sea, molecular analyses also identified the bacterium Vibrio sp. in moribund D. setosum specimens (Dinçtürk et al., 2024; Demircan et al., 2025). These mortality events appeared separately across thousands of kilometers within a few months, leading to diadematoid mortality rates of between 90–99%. The swift expansion of mortalities has been linked to anthropogenic factors, as initial outbreaks were predominantly recorded near harbor areas (Hylkema et al., 2023), although other organisms such as fish were also suggested as indirect vectors (Zirler et al., 2023).

The aims of this research were: (1) to provide an estimate of the spread of D. africanum mortalities in the Canary Islands through citizen surveys, (2) to assess the impact of the disease on remaining D. africanum adult populations via visual surveys across the Canary Islands, using historical data to evaluate population trends when available, (3) to evaluate the impact of D. africanum mortalities on the settlement success of the species using artificial larval collectors and early recruits visual surveys, and (4) to offer preliminary insights into the primary causative agents responsible for this latest MME in the Canaries, exploring possible links with the recently reported diadematoid MME worldwide.

2 Methods

2.1 Citizen surveys

In March 2023, six months after our initial observations of moribund D. africanum specimens off the coast of Tenerife, citizen surveys were conducted to ascertain the extent of the mortalities. The respondents comprised scientific divers and professional surveyors from 72 dive centers distributed across the Canary Islands. Of these, 6 were located in El Hierro, 6 in La Palma, 2 in La Gomera, 15 in Tenerife, 15 in Gran Canaria, 20 in Lanzarote, and 8 in Fuerteventura. Initially, participants were presented with general questions to assess their knowledge of the morphology of the target species, with the aim of minimizing identification errors. In cases where respondents expressed uncertainty concerning the species identification or were unable to describe the key morphological characteristics of D. africanum, their reports were excluded from the dataset. Of the 72 dive centers and professional surveyors contacted during our surveys, 35 met the criteria for inclusion in the dataset. Since some dive centers routinely visit several sites, the citizen surveys recorded a total of 40 localities with valid Diadema africanum information.

Following this preliminary assessment, participants were asked to provide additional data on the past and current status of D. africanum at their most visited dive localities. Specifically, they were asked to provide an estimate of the species’ status between 2018 and 2021 to facilitate the differentiation of the 2022–2023 MME from the 2018 MME. Questions covered respondent and locality details, species identification, historical population status, observations from the 2022–2023 MME, and current sea urchin population conditions (see questionnaire in Supplementary Materials). Based on the responses, we established three main categories: (1) Historical low densities – areas where D. africanum population densities were already low between 2018 and 2022, making it difficult to assess the impact of the current mortality event; (2) Healthy populations – areas with aggregations of D. africanum still present at the time of the interview; and (3) Mortality report – areas where significant numbers of moribund or dead D. africanum were observed.

2.2 Adult visual surveys and historical MMEs data collection

To assess the current status of D. africanum populations following the 2022–2023 MME, visual surveys were conducted between August 2022 and June 2025 at depths of 10–20 meters over rocky bottoms. In each surveyed locality, D. africanum individuals were counted along six to nine transects (parallel to the coastline), each measuring 10 × 2m, with a minimum distance of 10m between each transect. A total of 76 localities were sampled across the seven islands, as follows (numbering corresponds to the position of localities in Figure 1b.):

-

El Hierro Island: during August 2025, nine localities surveyed (1-9).

-

La Palma Island: between August 2022 and February 2023, 13 localities surveyed (10-22).

-

La Gomera Island: between September 2023 and May 2024, eight localities surveyed (23-30).

-

Tenerife Island: between October 2023 and April 2024, a total of 10 localities surveyed (31-40).

-

Gran Canaria Island: During June 2025, a total of six localities surveyed (41-46).

-

Fuerteventura Island: between November 2022 and June 2023, a total of 11 localities surveyed in the main island (47-57). Additionally, 11 benthic surveys were conducted around the islet of Lobos (58-68), situated between Lanzarote and Fuerteventura Islands.

-

Lanzarote Island: between February 2025 and March 2025, a total of eight localities surveyed (69-76).

Furthermore, historical density data of D. africanum from La Palma and Tenerife Island, were obtained from comparable visual surveys conducted by Hernández et al. (2010); Clemente et al. (2014), and Hernández et al. (2020a). Hernández et al. (2010) surveyed three localities on La Palma and three on Tenerife (54 transects in total) between 2004 and 2008 – representing pre-MME conditions. Clemente et al. (2014) surveyed six localities per island (126 transects) – representing densities following the 2010 mass-mortality event (MME). Hernández et al. (2020a) resurveyed three localities per island, conducting 54 transects in 2016 and 54 in 2018 – bracketing the 2018 MME. Collectively, these datasets provide a robust basis for evaluating long-term population trends across the two islands.

2.3 Settlement surveys

To assess the potential impact of the 2022 mass mortalities on the settlement capacity of D. africanum, larval settlement collectors were deployed in September 2023 at four localities along the eastern coast of Tenerife Island: Teresitas beach, Boca Cangrejo, Abades, and La Jaca (Figure 1c). This month was selected as D. africanum spawning occurs between August and October, with a settlement peak in September (Hernández et al., 2010, 2011). Localities were selected as representative localities of relatively sheltered conditions compared to northern localities off the island, the availability of historical settlement data from these localities, and the presence of surviving populations of D. africanum at these localities following the MME of 2018 in the case of Teresitas beach and La Jaca (Hernández et al., 2010; Clemente et al., 2014; Méndez-Álvarez, 2021).

Each larvae collector consisted of 30 polypropylene biofilter balls, each measuring 3.9cm in diameter, providing 0.04 m² of surface area for larval settlement and metamorphosis into juvenile sea urchins. Those biofilter balls were enclosed in a nylon net and anchored to the seabed using a 0.5-meter plastic rope, maintaining a minimum of distance of 5 meters between collectors. A buoy was attached to the top of each collector to maintain a vertical orientation in the water column (for details about the methodology and design see Balsalobre et al., 2016). Additional historical data on the settlement rates of D. africanum were extracted from Hernández et al. (2010); Clemente et al. (2014), and Méndez-Álvarez (2021) to compare previous and contemporary settlement rates. These studies employed similar sampling methodologies, ensuring the comparability of their results with the current dataset.

Additionally, four months after the deployment of the settlement collectors, in January 2024, four localities along the southeast coast of Tenerife—Boca Cangrejo, Punta del Poris, Abades, and La Jaca (Figure 1c)—were selected to conduct recruitment surveys of D. africanum (with recruits being defined as individuals with an approximate test diameter of >20mm). This timing ensured that D. africanum settlers had reached a sufficient size for visual quantification in situ (Hernández et al., 2006, 2010). At each location, 20 quadrats (25 × 25cm) were haphazardly deployed between 5–10 meters’ depth, with a total of 80 quadrats examined. Each quadrat was carefully inspected for recruits of D. africanum, and the substrate/rocks lifted when possible to avoid overlooking cryptic recruits.

2.4 Meteorological and oceanographic data

To provide environmental context for the outbreak of MMEs in the Canary Islands, we present oceanographic data coinciding with these events, following the precedent set by Hernández et al. (2020a). For this, hourly records of surface ocean current velocity and direction were retrieved for the period January 2022 to May 2023 from SIMAR point 4030020, located off the northern coast of Tenerife (28.92° N, 16.00° W). These data were generated by the SIMAR system, which provides regional oceanographic hindcasts based on high-resolution hydrodynamic modeling. We extracted surface layer data (0–1 m) to characterize nearshore current conditions during the MMEs.

To complement this dataset, we analyzed hourly records of sea surface temperature (SST), wave height, and wave direction from January 2020 to January 2024. These data were obtained from the oceanographic buoy of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, located off the southern coast of the island (28.46° N, 16.23° W).

All oceanographic data are publicly available through Puertos del Estado (http://www.puertos.es/es-es/oceanografia/Paginas/portus.aspx). To explore potential associations between oceanographic patterns and mortality events, these variables were plotted using the R package ggplot2 (Wickham et al., 2016). For the surface‐current data, we identified and highlighted all time intervals during which the prevailing flow was directed eastward, defined here by a directional window of 20° to 160° (measured clockwise from true north, 0–360°). For the wave‐height and wave‐direction data, we similarly flagged intervals when significant wave heights exceeded 2 m and the incoming wave direction fell between 90° and 270° (also referenced to true north). These conditions were selected according to our previous published study that linked uncommon south west swells and sea urchin mass mortalities (Hernández et al., 2020a).

2.5 Statistics

2.5.1 Statistical analysis of adult densities across MMEs

To evaluate the effects of the 2022–2023 D. africanum MME in comparison with the two previous MMEs affecting this species in the Canary Islands, we conducted a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using the “adonis2” function from the “vegan” R package (Oksanen et al., 2024). We selected this approach because preliminary analyses indicated heterogeneous variances among groups, violating the assumptions of parametric ANOVA (Anderson, 2001; Anderson and Walsh, 2013). In this analysis, we tested the influence of two fixed factors: “Island” (with two levels, La Palma and Tenerife) and “Year” (with 6 levels), as well as their interaction on contemporary and historical densities of D. africanum. The model also included the interaction between the fixed factor “Island” and the random factor “Locality”, nested within “Island”. The analysis was based on a Euclidean distance matrix derived from the response variable, with statistical significance assessed through 9999 permutations.

Subsequently, a post-hoc pairwise comparison of dissimilarity matrices was conducted using the “pairwise.adonis” function from the “vegan” R package (Oksanen et al., 2024) to examine differences between combinations of “Island” and “Year”. The pairwise comparisons were based on a distance matrix calculated from the dissimilarities between population densities, with the factor “Island” and the “Year” used to group the observations. A total of 9999 permutations were performed to estimate the statistical significance of the differences. To correct for multiple comparisons, the resulting p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction method.

2.5.2 Settlement surveys

In order to assess the potential influence of the 2022–2023 MME on the settlement success of D. africanum, we performed a PERMANOVA using the “adonis2” function from the “vegan” R package (Oksanen et al., 2024) to evaluate the effect of the fixed factor “Year” (with 8 levels representing the years where settlement rates of D. africanum were assessed) and the random factor “Locality” (nested within Year) on the variability of D. africanum settlement. This analysis was based on an Euclidean distance matrix derived from the settlement data. The significance of the factors was determined using 9999 permutations. As above, this approach was selected because preliminary analyses also indicated heterogeneous variances among groups, violating the assumptions of parametric ANOVA (Anderson, 2001; Anderson and Walsh, 2013).

Subsequently, a post-hoc pairwise comparison of dissimilarity matrices was conducted using the “pairwise.adonis” function from the “vegan” package (Oksanen et al., 2024). The pairwise comparisons were based on a distance matrix of the settlement data, with the factor “Date” used to group the observations. A total of 9999 permutations were performed to estimate the statistical significance of the differences. To control for multiple comparisons, the resulting p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction method.

3 Results

3.1 Citizen surveys

Among the 40 localities with valid Diadema africanum information, significant reductions in D. africanum populations and/or symptomatic individuals were reported at 31 localities. Of the remaining 9 localities, 5 reported consistently low sea urchin densities, with no observed changes or moribund individuals, while 4, all located in Gran Canaria, reported healthy populations throughout.

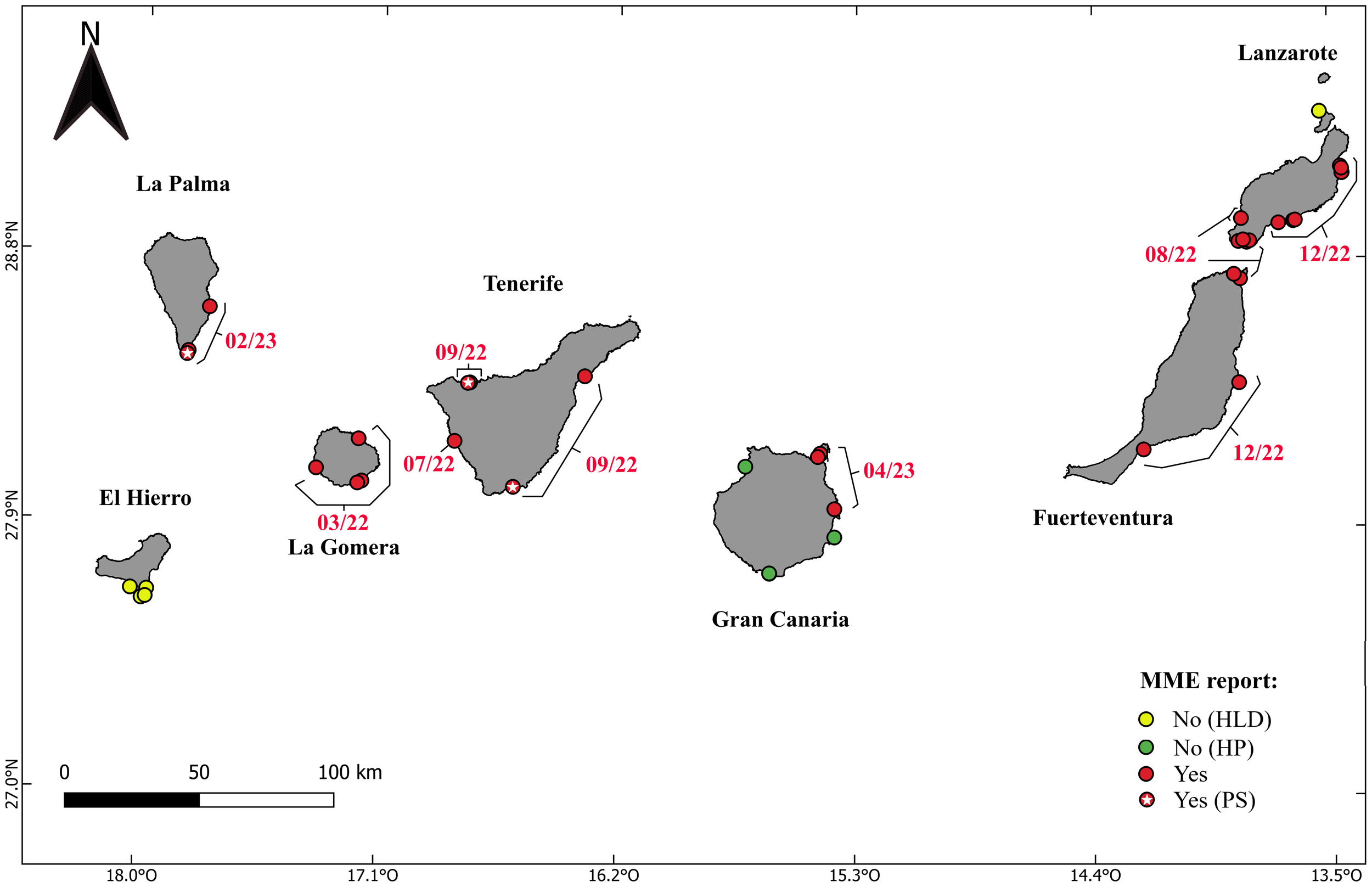

The results obtained from citizen surveys indicate that the mortalities affected nearly all the Canary Islands during two distinct periods through 2022-2023, beginning in the western islands and progressing along a latitudinal gradient toward the eastern islands. The first report was recorded by two dive centers in La Gomera on March 7, 2022. Approximately five months later, on July 30, 2022, a dive center in southern Tenerife reported mortalities. Four months later, in the first two weeks of September 2022, numerous moribund sea urchins were observed by the research team and two dive centers in the northern and eastern coasts of Tenerife. Notably, on August 20, 2022, the first report of moribund D. africanum individuals was also documented by a dive center in the Bocaina Strait, which is a shallow platform between Lanzarote and Fuerteventura Islands. From that date, the mortalities appeared to have spread to these two islands, with eleven of fourteen additional dive centers confirming these observations by December 2022.

Nearly a year following the initial reports, on February 11, 2023, another mass mortality event was observed by the research team and two dive centers on the western coast of La Palma Island, with numerous individuals exhibiting symptoms, similar to those seen in Tenerife. The mortalities then spread eastward, reaching Gran Canaria, where three dive centers first reported it in April 2023, while four others reported healthy D. africanum populations in the south and west sides of the island. Subsequent communications with the dive centers revealed the disappearance of the sea urchins in previously unaffected areas of Gran Canaria; however, the dive centers were unable to specify the exact dates of the population decline. El Hierro was the only island that did not report mortalities, likely due to historically low population densities of this species there (Hernández et al., 2008b) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Map of the Canary Islands showing the temporal progression of sea urchin mortality across the archipelago based on combined citizen and professional surveys. Yellow dots indicate areas where population densities between 2018 and 2022 were too low to discern any potential impact of the disease (Historical Low Densities);. Green dots represent healthy populations (HP), while red dots indicate populations where symptomatic individuals have been observed, along with a clear population decline. White stars indicate reports made by professional surveyors (PS). Red dates indicate the first reports of the disease in distinct geographical areas.

3.2 Adult abundances across MMEs

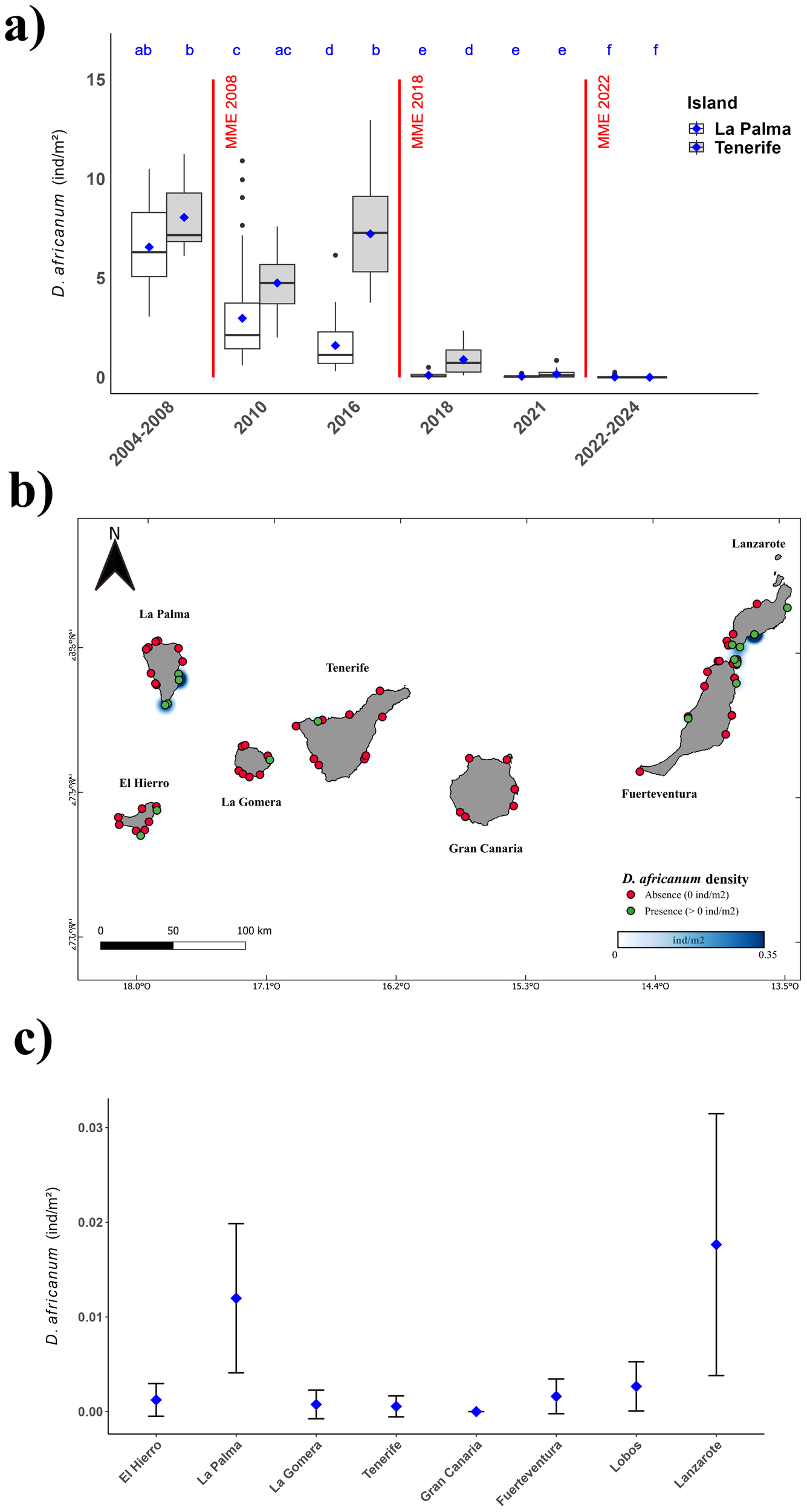

Our analysis of variations in D. africanum population densities demonstrated a significant effect of the fixed factors “Period” and “Island,” as well as their interaction (Table 1). Subsequent post-hoc analyses revealed differential population responses following the mass mortality events, with La Palma exhibiting diminished recovery following the 2008 event compared to Tenerife, where populations increased until the 2018 MME resulted in a significant decline. A significant decline of D. africanum populations was also observed between the 2018 MME and the 2022–2023 MME (Figure 3a).

Table 1

| Source | Df | SumOfSqs | R2 | F | P.value | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Island | 1 | 6.8 | <0.01 | 3.92 | 0.047 | * |

| Year | 5 | 2912.3 | 0.7 | 337.99 | <0.01 | *** |

| Island: Year | 5 | 327.6 | 0.08 | 38.02 | <0.01 | *** |

| Island: Locality | 28 | 58.1 | 0.01 | 1.2 | 0.227 | ns |

| Residual | 495 | 853 | 0.21 | |||

| Total | 534 | 4157.8 | 1 |

Results of PERMANOVA testing D. africanum densities across Years, Islands, and Locations, with “Year” and “Island” as a fixed factor and “Location” as a random factor nested within “Year.” Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05; *p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, non-significant).

Figure 3

(a) Boxplot representing abundances of Diadema africanum adult individuals across all studied years on Tenerife and La Palma. Red dashed vertical lines indicate the MMEs of 2010, 2018, and 2022–2023. Blue dots represent mean abundances, and letters denote significant differences among treatments according to the post-hoc test. Historical data were obtained from Hernández et al. (2010) for the years 2004 to 2008, from Clemente et al. (2014) for 2010, and from Hernández et al. (2020a) for 2018. (b) Map of the Canary Islands showing the current distribution of sea urchins according to our visual surveys. Red dots indicate localities where a total absence of D. africanum was recorded, while green dots indicate localities where the species was present. The blue gradient represents current densities. (c) Mean abundances (individuals per square meter) ± SD of adult D. africanum across all islands studied following the 2022–2023 mass mortalities.

Furthermore, our analysis revealed a sharp reduction in D. africanum populations following the 2022–2023 MME, with a 73.8% decrease in La Palma and a 99.66% decrease in Tenerife compared to 2021 data. No significant differences in sea urchin populations between islands were observed after 2018 (Supplementary Table 1; Figure 3). Of the 76 visual surveys conducted, only 17 recorded the presence of Diadema africanum, with the highest densities found on the southeastern coasts of La Palma and Lanzarote (Figure 3b). However, in all cases, sea urchin densities remained consistently below 0.04 ind/m², likely reflecting the severity of the 2022–2023 MME (Figure 3c).

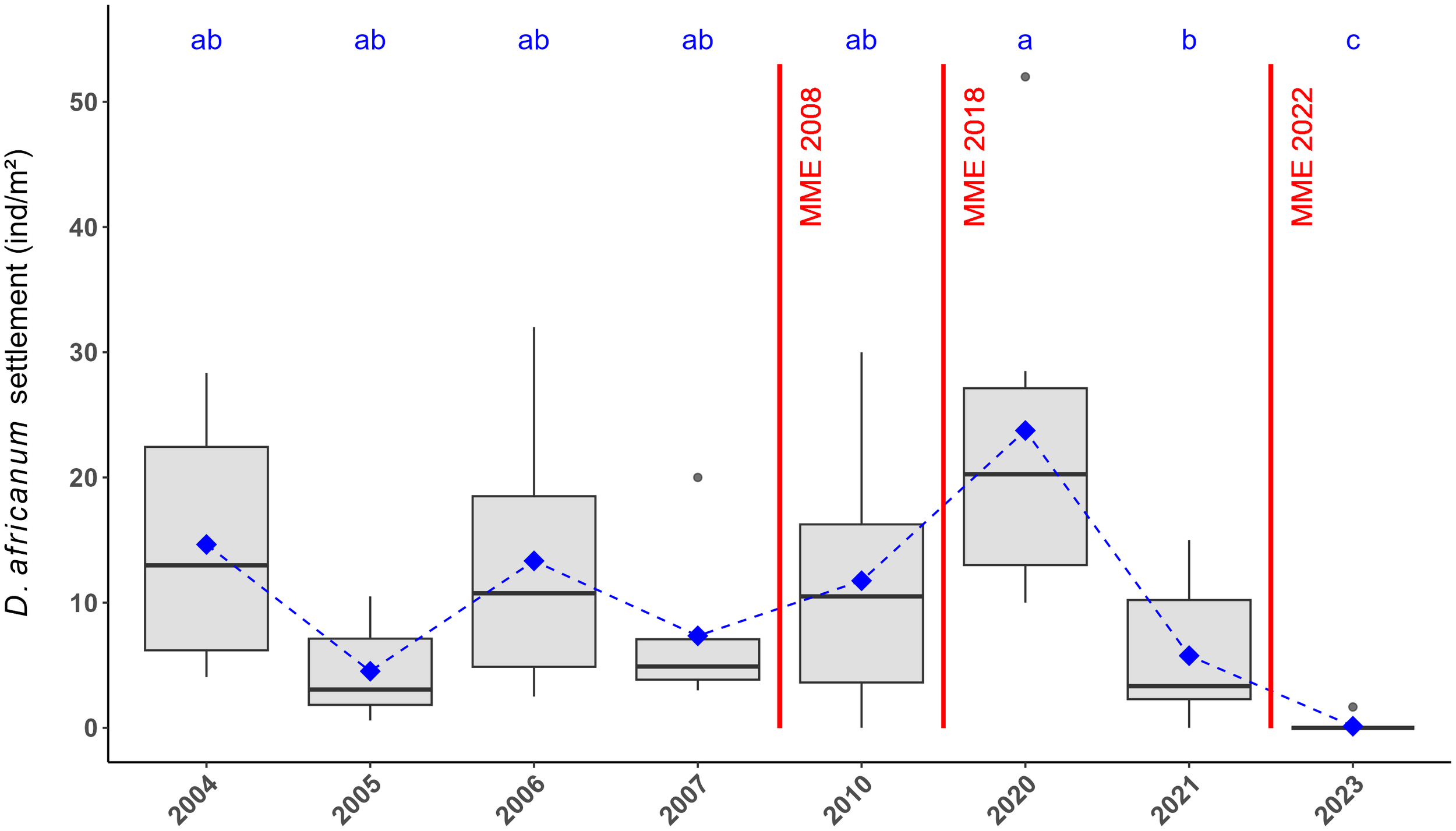

3.3 Settlement and recruitment

Settlement rates of D. africanum revealed a complete settlement failure in September 2023 at all studied locations, with almost zero settlers observed in our experimental units (Figure 4). This observation was supported by the visual surveys conducted in January 2024 which similarly showed a complete absence of D. africanum recruits at the four studied locations along the eastern shores of Tenerife.

Figure 4

Boxplots representing abundances of D. africanum settlers per artificial larval collector in September across all studied years on Tenerife Island. Red dashed lines represent the MMEs of 2010, 2018, and 2022–2023. Blue dots indicate the mean abundance of sea urchin settlers, and blue letters denote significant differences among treatments according to the post-hoc test. Data from Hernández et al. (2010) for the years 2004 to 2007, from Clemente et al. (2014) for the year 2010 and from Méndez-Álvarez (2021) for the year 2020 are included in the analysis.

PERMANOVA analysis conducted on the settlement rates using artificial larvae collectors, revealed significant differences in D. africanum settlement between “Dates”, with a significant interaction with the random factor “Location” (Table 2). The post hoc analysis, followed by Bonferroni corrections, revealed marked differences between 2023 and the rest of the years studied, regardless of the 2008 and 2018 MMEs (Supplementary Table 2; Figure 4).

Table 2

| Source | Df | Sum Of Sqs | R2 | F | P-value | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 7 | 2929.2 | 0.45 | 8.86 | 0.001 | *** |

| Year: Location | 12 | 1621 | 0.25 | 2.86 | 0.009 | ** |

| Residual | 41 | 1936.5 | 0.3 | |||

| Total | 60 | 6486.7 | 1 |

Results of PERMANOVA for settlement rates of D. africanum across Dates and Locations, with “Date” treated as a fixed factor and “Location” as a random factor nested within “Date.” Asterisks denote levels of statistical significance (* = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001; ns = non-significant).

3.4 Meteorological and oceanographic data

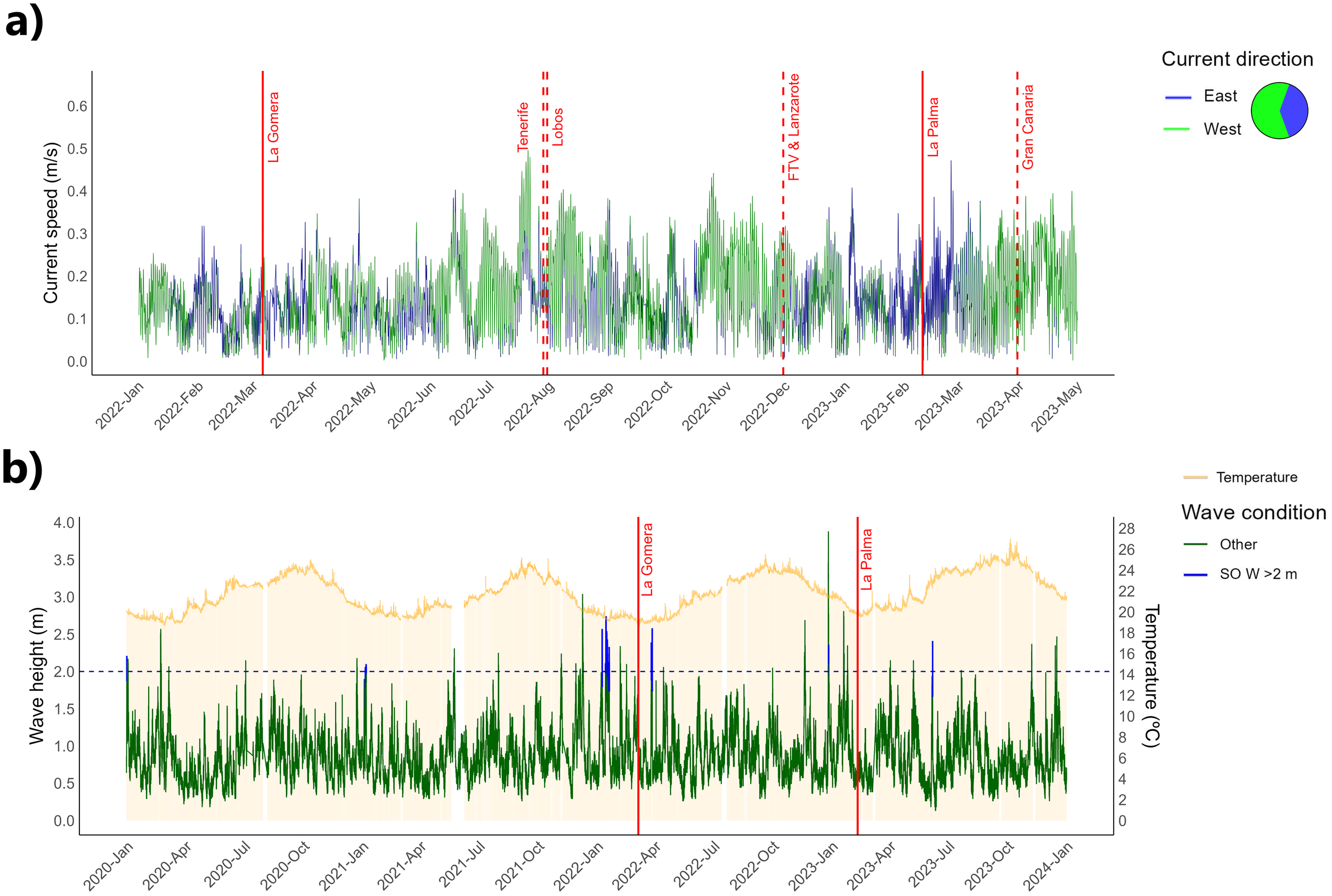

Our historical analysis of sea‐surface currents during the 2022–2023 MME affecting D. africanum in the Canary Islands revealed that west-to-east currents were present both before and after the outbreaks in La Gomera and La Palma. This pattern began approximately six weeks prior to the La Gomera MME and approximately eight weeks prior to the La Palma MME. Following both events, eastward currents persisted but were uncommon and did not coincide with the initial mortality reports from the other islands (Figure 5a).

Figure 5

Temporal plots showing: (a) Hourly surface current speed (in meters/second) and direction from January 2022 to May 2023. (b) Hourly SST (shaded yellow background) and wave height (in meters) from January 2020 to January 2024. The horizontal dashed blue line indicates the two meters wave height threshold proposed by Hernández et al. (2020a) as a key driver of the 2018 Diadema africanum MME. Solid blue lines mark periods when these waves originated from the south. Red solid vertical lines indicate the timing of disease outbreaks in La Gomera and La Palma, while red dashed lines indicate outbreaks reported in the other islands.

With respect to oceanographic events over the four-year study period, unusual high-energy waves over 2m in height developing in the south, occurred from January 9 to 20, 2022, shortly preceding mortalities outbreak in La Gomera. Similar exceptional high waves preceded the mortalities outbreak in La Palma. Here the south-originated high waves only occurred on December 27, 2022, for a short period, likely as the result of a significant winter storm that generated waves of more than 3m around the island (Figure 5b).

SSTs data during the 4-year period spanning the 2022–2023 MME (January 2020 to January 2024) showed no clear relationship between SST and the spread of mortalities across the Canaries. On the contrary, disease outbreaks in February 2022 (La Gomera) and March 2023 (La Palma) coincided with the lowest SST values recorded during those years, a pattern common to winter months (Figure 5b).

4 Discussion

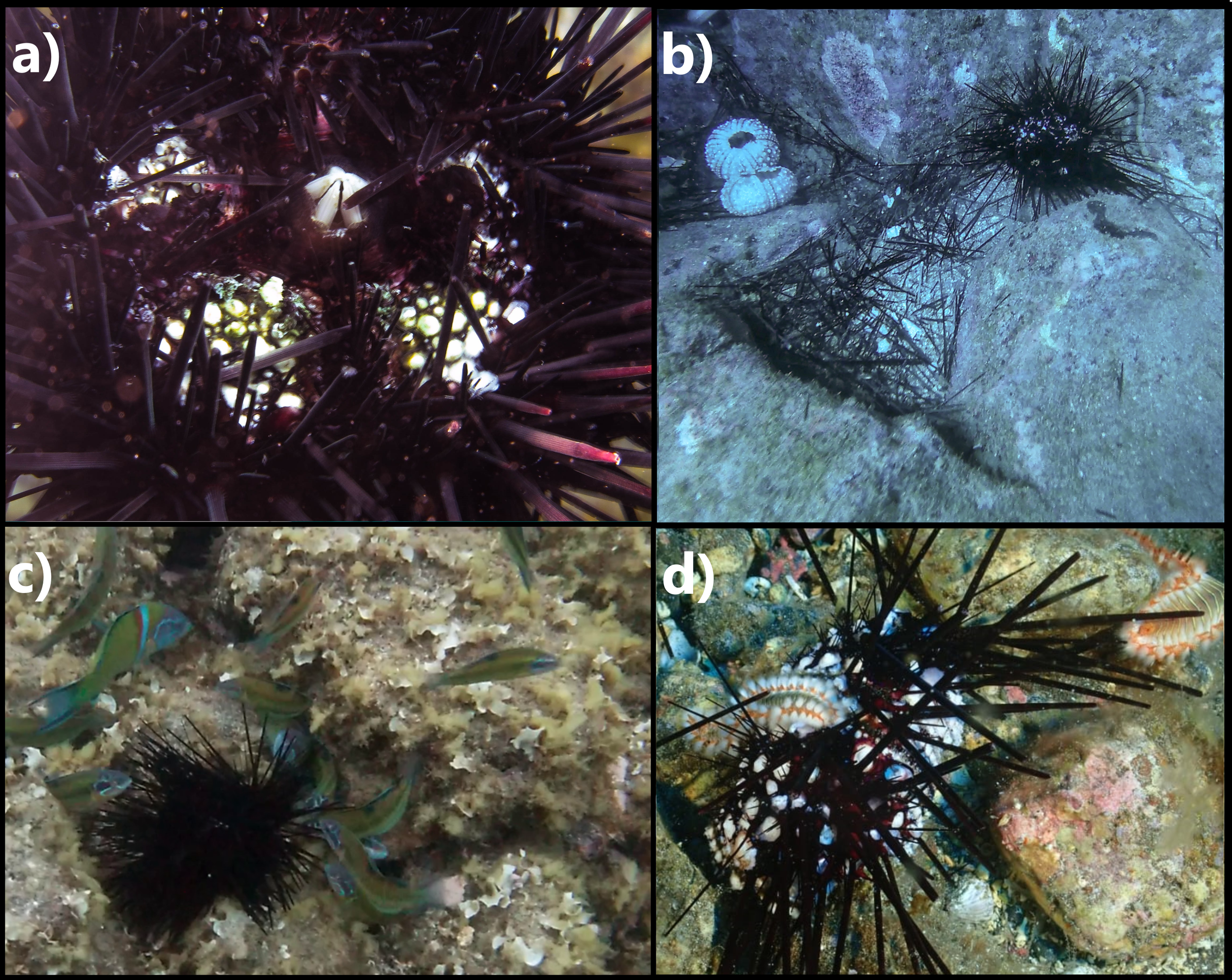

Our citizen-based study on the extent and impact of mass mortalities in the key herbivore Diadema africanum revealed widespread, recurrent mortality events affecting this species across the Canary Islands. Uniquely, this event only appears to have affected D. africanum, with affected individuals exhibiting similar symptoms to those previously described in other diadematids MMEs: severely reduced mobility and response to stimuli, loosely attached spines with abnormal movement, inability to adhere to the substrate, and lesions marked by tissue necrosis and loss, exposing bare areas of the test in moribund individuals, mainly at the basal region around Aristotle’s lantern (Clemente et al., 2014; Hernández et al., 2020a; Zirler et al., 2023; Roth et al., 2024). As mortalities progressed, dead individuals were often found aggregated in crevices, with empty tests, and clearly visible accumulations of spines were observed scattered on the seabed (Figure 6). According to the present data, MME outbreaks appeared to have occurred during two separate events, both sharing two common characteristics: they both began in the winter months of their respective years—March 2022 and February 2023—and both started in the western islands before spreading eastward, affecting all other islands of the archipelago with the only possible exception being El Hierro. The later, however, has historically maintained low densities of D. africanum – a feature attributed to the well preserve marine communities in the islands due to sustainable fishing activities which maintains a high biomass of sea urchin predators (Hernández et al., 2008b; Clemente et al., 2010). Therefore, even if D. africanum mortalities indeed spread to the island, the effects might have easily gone unnoticed by the citizen science surveys. Other sea urchin species present in the archipelago, such as Arbacia lixula, Paracentrotus lividus, and Sphaerechinus granularis, did not appear to show similar symptoms or notable population declines.

Figure 6

Images of moribund D. africanum off Tenerife Island during the September 2022 mass mortality event: (a) Moribund individual of D. africanum showing abnormal position and movement of the spines with white and greenish bare areas devoid of tissue; (b) Accumulation of detached spines and dead D. africanum individuals on the sea bed; (c) The fish Thalassoma pavo predating upon a moribund individual of D. africanum; and (d) The polychaete Hermodice carunculata feeding on a dead individual of D. africanum.

Since the first reports of MMEs, Diadema africanum populations have undergone a constant, progressive decline. For example, a negative population trend became evident on La Palma Island following the 2008 MME, whereas in Tenerife, D. africanum initially exhibited a marked recovery, which was interrupted by the 2018 MME. After this event, populations experienced a significant decline, as reflected in 2021 data from the island. Notably, no MMEs were detected in Tenerife between 2018 and 2021, suggesting that ecological processes—such as the observed reduction in sea urchin settlement rates combined with the natural mortality of adult individuals (Hernández et al., 2008b; Cano et al., 2025)—account for the continued population decrease during this period. As a result, D. africanum densities in Tenerife reached values comparable to those observed in La Palma for the first time since the 2008 MME, suggesting that once adult densities fall below a natural threshold, reproductive success may become insufficient to maintain population stability, resulting in a progressive decline over time even in the absence of additional mortality events.

Nevertheless, despite the gradual decline of D. africanum populations, the species remained relatively common prior to the 2022–2023 MME, with scattered aggregations and solitary individuals being easily spotted in shallow rocky habitats along the eastern coast of Tenerife, particularly in localities such as La Jaca and Teresitas Beach. Similarly, reports of dense aggregations remained common in other islands including Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, and La Gomera, where citizen-led eradication campaigns targeting D. africanum populations were still being carried out after the 2018 MME (in press, El Día, 2019). This suggest that the 2010 and 2018 MMEs did not affect the entire population of the species in the archipelago.

To date, based on the extensive visual censuses conducted between 2022 and 2025, D. africanum have almost disappeared from the shallow rocky reefs of the Canaries. Specifically, our results based on comparisons with the 2021 data showed additional sharp population declines on the eastern coast of Tenerife and the western coast of La Palma. Even on islands where citizen surveys reported uncertainty or even healthy Diadema populations, such as Gran Canaria or El Hierro, exhibited extremely low densities of this species, potentially suggesting that MMEs also affected these areas. Nevertheless, current abundances of D. africanum across the Canary Islands is at an all-time low since the initiation of monitoring efforts in 1965, with several populations nearing local extinction.

With respect to temporal settlement, we found that, despite the severity of the 2010 and 2018 MMEs, the recruitment capacity of D. africanum populations in Tenerife was practically unaffected (Clemente et al., 2014; Méndez-Álvarez, 2021). Given the high connectivity exhibited by D. africanum populations across distant localities facilitated by its planktotrophic larva with an extended development (Hernández et al., 2020b; Peralta-Serrano et al., 2024), it seems that surviving populations of D. africanum were capable of replenishing affected localities through successful long-distance recruitment. This finding is particularly striking because it may indicate that the “natural” decline in adult D. africanum populations between MMEs was not driven by impaired recruitment, but by ecological feedbacks related to community phase shift. Following the 2018 MME, the widespread reversion to macroalgal beds appears to have diminished suitable habitat and settlement localities for D. africanum, thereby reducing post-settlement survival and subsequently contributing to population decline, as previously reported for the archipelago (Sangil and Hernández, 2022; Cano et al., 2024, 2025).

However, our analyses of D. africanum settlement success following the 2022–2023 MME revealed a complete recruitment failure on the eastern coast of Tenerife, even during September – the most favorable recruitment month of the year (Hernández et al., 2010). Only a negligible number of settlers were detected in our larval settlement collectors, representing the first observation of this kind in nearly two decades of D. africanum settlement monitoring in Tenerife. Additionally, no recruits were detected in the shallow rocky habitats surveyed four months after the initial settlement assessment, confirming the absence of a new cohort in the field and indicating that the 2023 settlement was unlikely to have been missed. These results potentially indicate that the 2022–2023 MME had a profound impact on the reproductive populations of D. africanum, likely compromising fertilization success through Allee effect mechanisms (Gascoigne and Lipcius, 2004). This, along with the ongoing loss of suitable recruitment habitat (Cano et al., 2024, 2025), and the low genomic diversity and homogeneity reported for this species following the 2018 MME (Peralta-Serrano et al., 2024), suggests that the 2022–2023 MME had fundamentally compromised the ability of D. africanum to naturally recruit, potentially implying exceptionally long recovery durations (at best) and the collapse of local populations. A similar long-lasting effect has been well documented in the Caribbean Sea following the MME of the congeneric D. antillarum during the early 80s (Lessios, 2016). However, it is important to note that other factors, such as the onset of the El Niño event in July 2023, may have influenced our results—for instance, through altered currents that could have limited larval supply to our study areas (Peng et al., 2024). Future recruitment monitoring and population structure studies will be necessary to assess the long-term viability of this species.

The initial reports of mortality outbreaks in the Canaries occurred two months after the first reports of a similar MME affecting D. antillarum in the Caribbean, which began in January 2022 (Hewson et al., 2023; Hylkema et al., 2023). Four months after the first reports of MMEs in the Canaries, another event affecting Diadema setosum was reported in the Eastern Mediterranean (Zirler et al., 2023), and five months later, mass mortalities affecting both D. setosum and Echinometrix calamarix were documented in the Red Sea (Roth et al., 2024). By mid-2023 the mortalities have spread beyond the Red Sea and were reported from Oman and the Persian Gulf (Ritchie et al., 2023) before arriving to the Western Indian Ocean off the coasts of Reunion (Quod et al., 2024). Thus, there is compelling possibility that the recent MMEs affecting diadematoids worldwide are all connected. As such, D. africanum mass mortalities in the Canary Islands may represent a potential link in what may be considered a marine pandemic, initiating in the Caribbeans, and potentially spreading over thousands of kilometers within a few months, affecting both tropical and subtropical regions alike.

In this context, the earliest observations of moribund Diadema africanum in the Canary Islands coincided with prolonged periods of eastward‐flowing sea‐surface currents. This hydrodynamic regime began roughly six weeks before the first diseased individuals were recorded in La Gomera. Likewise, the second MME on the western coast of La Palma similarly occurred under a comparable eastward‐current regime, suggesting the possibility of the potential transport of a waterborne pathogen from the west. Following these two distinct episodes of persistent eastward flow, eastward currents became sporadic, oscillating with the prevailing northeast–southwest regime (Marrero-Betancort et al., 2020). Such oscillations could have contributed to the spread of a waterborne pathogen, causing mortalities throughout the archipelago, driven by typical Canarian mesoscale oceanographic dynamics, such as tidal currents and water mass retention eddies. However, it is important to emphasize that, without controlled experimental evidence, we cannot definitively identify current oscillations as the primary dispersal mechanism. Alternative vectors operating simultaneously—such as predatory fish scavenging on moribund urchins or regional marine traffic—may also have facilitated the regional transmission of a potential waterborne pathogen, as suggested by Zirler et al. (2023) for the Mediterranean MME affecting D. setosum.

Currently, no consistent pathogenic studies have yet been conducted in the Canaries, largely due to the lack of available samples from the time of mortalities, thus the exact causative agent of the 2022–2023 D. africanum mass mortalities cannot be asserted. Nevertheless, the recent Canaries MME share several similarities with the two previous MMEs affecting this species in the archipelago. In all three Canarian MMEs, the initial disease outbreaks began in the coldest months of the year: February 2010 (Clemente et al., 2014), February 2018 (Hernández et al., 2020a) and March 2022-February 2023 (present study). Additionally, the current mortalities trajectory was similar to that of the 2018 MME, which also started in the western islands and moved eastwards (Hernández et al., 2020a).

During the 2010 and 2018 Canary MMEs, it was hypothesized that the disease outbreaks were initiated by anomalous storms originating from the south that initiated during the winter months (Hernández et al., 2020a). In line with these observations, we similarly recorded uncommon south-originating waves exceeding two meters in height, approximately one and a half months before the onset of mortality outbreak on La Gomera Island. This oceanographic event lasted eleven days and was likely associated with high turbidity levels and nutrient enrichment in the water column. Such conditions have previously been proposed to favor the proliferation of waterborne pathogens known to affect D. africanum as well as other echinoid species globally (Scheibling and Lauzon-Guay, 2010; Feehan et al., 2012; Hernández et al., 2020a; Salazar-Forero et al., 2022). Clearly, the currently provided environmental context of the 2022–2023 Canary Islands MME is circumstantial and are intended to provide the broader context of mortalities. While insufficient for directly implicating the anomalous southern winter storm as the triggering factor of mortalities, current circumstantial evidence is well aligned with previously published evidence and highlights the urgent need for further investigations. In this regard, exploring the potential involvement of alternative pathogens, such as amoebae and Vibrio species, may offer valuable insights into the mechanisms driving recent diadematid die-offs worldwide.

5 Conclusions

In summary, the unprecedented decline of D. africanum populations across the Canary Islands following the 2022–2023 MME, bear severe consequences for the resilience of this key herbivore in the shallow rocky habitats of the archipelago. The near complete decline of adult populations, coupled with the observed recruitment failure, suggests a long-term disruption of its life cycle. Unlike previous MMEs in the region, where recruitment persisted despite significant adult decimation, the 2022–2023 events seem to have almost eradicated source populations, limiting the species’ capacity for natural recolonization. These findings suggest a near-complete collapse of the species in the region and raises urgent concerns about the future viability of D. africanum populations in the Canaries, with potential cascading effects on ecosystem structure and function.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

IC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JL: Writing – review & editing. OB: Writing – review & editing. CS: Writing – review & editing. JH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. JL-M was supported by the Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica (CIBER) de Enfermedades Infecciosas (CIBERINFEC); Instituto de Salud Carlos III, 28006 Madrid, Spain (CB21/13/00100); Cabildo Insular de Tenerife 2023–2028 (Proyecto CC20230222, CABILDO.23), and Ministerio de Sanidad, Spain. Additional funding was provided by Israel’s Ministry of Regional Cooperation (grant no. 1001808844) and the Tel Aviv University seed grant to OB.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aitor Ugena for his work in collecting information from the citizen surveys and for his assistance during fieldwork. We also thank Marina Aliende and Andrés Rufino for their support in conducting the underwater visual censuses using SCUBA equipment.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1665504/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Anderson M. J. (2001). A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol.26, 32–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2001.01070.pp.x

2

Anderson M. J. Walsh D. C. (2013). PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: what null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol. Monogr.83, 557–574. doi: 10.1890/12-2010.1

3

Balsalobre M. Wangensteen O. S. Palacín C. Clemente S. Hernández J. C. (2016). Efficiency of artificial collectors for quantitative assessment of sea urchin settlement rates. Scientia Marina80, 207–216. doi: 10.3989/scimar.04252.13A

4

Baskett M. L. Salomon A. K. (2010). Recruitment facilitation can drive alternative states on temperate reefs. Ecology91, 1763–1773. doi: 10.1890/09-0515.1

5

Cano I. González-Delgado S. Hernández J. C. (2025). Benthic community phase shifts towards macroalgae beds compromise the recruitment of the long-spined sea urchin Diadema africanum. Mar. Environ. Res.205, 106999. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2025.106999

6

Cano I. Ugena A. González-González E. Hernández J. C. (2024). Assessing the influence of macroalgae and micropredators on the early life success of the echinoid Diadema africanum. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.309, 108972. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2024.108972

7

Clemente S. Hernández J. C. Rodríguez A. Brito A. (2010). Identifying keystone predators and the importance of preserving functional diversity in sublittoral rocky-bottom areas. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.413, 55–67. doi: 10.3354/meps08700

8

Clemente S. Lorenzo-Morales J. Mendoza J. C. López C. Sangil C. Alvez F. et al . (2014). Sea urchin Diadema africanum mass mortality in the subtropical eastern Atlantic: role of waterborne bacteria in a warming ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.506, 1–14. doi: 10.3354/meps10829

9

Demircan M. D. Arslan-Aydogdu E.Ö. Dalyan C. Eldem V. Gönülal O. Tüney İ. (2025). Mortality event of the Mediterranean invasive sea urchin Diadema setosum from Gökova bay (Southern Aegean Sea). Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.319, 109290. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2025.109290

10

Dinçtürk E. Öndes F. Alan V. Dön E. (2024). Mass mortality of the invasive sea urchin Diadema setosum in Türkiye, eastern Mediterranean possibly reveals vibrio bacteria infection. Mar. Ecol.45 (6), e12837. doi: 10.1111/maec.12837

11

Do Hung Dang V. Fong C. L. Shiu J. H. Nozawa Y. (2020). Grazing effects of sea urchin Diadema savignyi on algal abundance and coral recruitment processes. Sci. Rep.10, 20346. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77494-0

12

Dyková I. Lorenzo-Morales J. Kostka M. Valladares B. Pecková H. (2011). Neoparamoeba branchiphila infections in moribund sea urchins Diadema aff. antillarum in Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain. Dis. Aquat. organisms95, 225–231. doi: 10.3354/dao02361

13

El Día (2019). San Sebastián realiza una acción de control de erizos de mar en la bahía ( El Día). Available online at: https://www.eldia.es/la-gomera/2019/12/15/san-sebastian-realiza-accion-control-22508622.html (Accessed June 13, 2025).

14

Feehan C. J. Scheibling R. E. (2014). Effects of sea urchin disease on coastal marine ecosystems. Mar. Biol.161, 1467–1485. doi: 10.1007/s00227-014-2452-4

15

Feehan C. Scheibling R. E. Lauzon-Guay J. S. (2012). An outbreak of sea urchin disease associated with a recent hurricane: Support for the “killer storm hypothesis” on a local scale. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.413, 159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.12.003

16

Gascoigne J. Lipcius R. N. (2004). Allee effects in marine systems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.269, 49–59. doi: 10.3354/meps269049

17

Gizzi F. Jiménez J. Schäfer S. Castro N. Costa S. Lourenço S. et al . (2020). Before and after a disease outbreak: tracking a keystone species recovery from a mass mortality event. Mar. Environ. Res.156, 104905. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.104905

18

Hernández J. C. Brito A. Cubero E. García N. Girard D. González-Lorenzo G. et al . (2006). Temporal patterns of larval settlement of Diadema antillarum (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) in the Canary Islands using an experimental larval collector. Bulletin of Marine Science78 (2), 271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.104905

19

Hernández J. C. (2017). Influencia humana en las fluctuaciones poblacionales de erizos de mar. Rev. Biología Trop.65, S23–S34. doi: 10.15517/rbt.v65i1-1.31663

20

Hernández J. C. Clemente S. Brito A. (2011). Effects of seasonality on the reproductive cycle of Diadema aff. antillarum in two contrasting habitats: implications for the establishment of a sea urchin fishery. Mar. Biol.158, 2603–2615. doi: 10.1007/s00227-011-1761-0

21

Hernández J. C. Clemente S. García E. McAlister J. S. (2020b). Planktonic stages of the ecologically important sea urchin, Diadema africanum: larval performance under near future ocean conditions. J. Plankton Res.42, 286–304. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbaa016

22

Hernández J. C. Clemente S. Girard D. Pérez-Ruzafa Á. Brito A. (2010). Effect of temperature on settlement and postsettlement survival in a barrens-forming sea urchin. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.413, 69–80. doi: 10.3354/meps08684

23

Hernández J. C. Clemente S. Sangil C. Brito A. (2008a). The key role of Diadema aff. antillarum (Echinoidea: Diadematidae) throughout the Canary Islands (eastern subtropical Atlantic) in controlling macroalgae assemblages: an spatio-temporal approach. Mar. Environ. Res.66, 259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2008.03.002

24

Hernández J. C. Clemente S. Sangil C. Brito A. (2008b). Actual status of the sea urchin Diadema aff. antillarum populations and macroalgal cover in marine protected areas compared to a highly fished area (Canary Islands—eastern Atlantic Ocean). Aquat. Conservation: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst.18, 1091–1108. doi: 10.1002/aqc.903

25

Hernández J. C. Sangil C. Lorenzo-Morales J. (2020a). Uncommon southwest swells trigger sea urchin disease outbreaks in Eastern Atlantic archipelagos. Ecol. Evol.10, 7963–7970. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6260

26

Hewson I. Ritchie I. T. Evans J. S. Altera A. Behringer D. Bowman E. et al . (2023). A scuticociliate causes mass mortality of Diadema antillarum in the Caribbean Sea. Sci. Adv.9, eadg3200. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adg3200

27

Hylkema A. Kitson-Walters K. Kramer P. R. Patterson J. T. Roth L. Sevier M. L. et al . (2023). The 2022 Diadema antillarum die-off event: Comparisons with the 1983–1984 mass mortality. Front. Mar. Sci.9, 1067449. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1067449

28

Ishikawa T. Maegawa M. Kurashima A. (2016). Effect of sea urchin (Diadema setosum) density on algal composition and biomass in cage experiments. Plankton Benthos Res.11, 112–119. doi: 10.3800/pbr.11.112

29

Johnston C. S. (1969). Studies on the ecology and primary production of Canary Islands marine algae. Proc. Int. Seaweed Symp6, 213–222.

30

Lessios H. A. (2016). The great Diadema antillarum die-off: 30 years later. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci.8, 267–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-122414-033857

31

Ling S. D. Scheibling R. E. Rassweiler A. Johnson C. R. Shears N. Connell S. D. et al . (2015). Global regime shift dynamics of catastrophic sea urchin overgrazing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.370, 20130269. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0269

32

Marrero-Betancort N. Marcello J. Rodríguez Esparragón D. Hernández-León S. (2020). Wind variability in the Canary Current during the last 70 years. Ocean Sci.16, 951–963. doi: 10.5194/os-16-951-2020

33

Méndez-Álvarez A. (2021). Asentamiento larvario del erizo de mar Diadema africanum (Rodríguez et al., 2013), post-mortalidad masiva de 2018. University of La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain.

34

Nowak B. F. Archibald J. M. (2018). Opportunistic but lethal: the mystery of paramoebae. Trends Parasitol.34, 404–419. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.01.004

35

Oksanen J. Simpson G. Blanchet F. Kindt R. Legendre P. Minchin P. et al . (2024). vegan: Community ecology package (R package version 2.6-6.1). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (Accessed June 13, 2025).

36

Peng Q. Xie S. P. Passalacqua G. A. Miyamoto A. Deser C. (2024). The 2023 extreme coastal El Niño: Atmospheric and air-sea coupling mechanisms. Sci. Adv.10, eadk8646. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adk8646

37

Peralta-Serrano M. Hernández J. C. Guet R. González-Delgado S. Pérez-Sorribes L. Lopes E. P. et al . (2024). Population genomic structure of the sea urchin Diadema africanum, a relevant species in the rocky reef systems across the Macaronesian archipelagos. Sci. Rep.14, 22494. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-73354-3

38

Quod J. P. Séré M. Hewson I. Roth L. Bronstein O. (2024). Spread of a sea urchin disease to the Indian Ocean causes widespread mortalities—Evidence from Réunion Island. Ecology106, e4476. doi: 10.1002/ecy.4476

39

Ritchie I. T. Vilanova-Cuevas B. Altera A. Cornfield K. Evans C. Evans J. S. et al . (2023). Transglobal spread of an ecologically significant sea urchin parasite. bioRxiv18 (1), 2023–2011. doi: 10.1101/2023.11.08.566283

40

Rodríguez A. Hernández J. C. Clemente S. Coppard S. E. (2013). A new species of Diadema (Echinodermata: Echinoidea: Diadematidae) from the eastern Atlantic Ocean and a neotype designation of Diadema antillarum (Philippi, 1845). Zootaxa3636 (1), 144–170.

41

Roth L. Eviatar G. Schmidt L. M. Bonomo M. Feldstein-Farkash T. Schubert P. et al . (2024). Mass mortality of diadematoid sea urchins in the Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean. Curr. Biol.34, 2693–2701.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.04.057

42

Salazar-Forero C. E. Reyes-Batlle M. González-Delgado S. Lorenzo-Morales J. Hernández J. C. (2022). Influence of winter storms on the sea urchin pathogen assemblages. Front. Mar. Sci.9, 812931. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.812931

43

Sammarco P. W. (1982). Effects of grazing by Diadema antillarum Philippi (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) on algal diversity and community structure. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.65, 83–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(82)90177-0

44

Sangil C. Hernández J. C. (2022). Recurrent large-scale sea urchin mass mortality and the establishment of a long-lasting alternative macroalgae-dominated community state. Limnology Oceanography67, S430–S443. doi: 10.1002/lno.11966

45

Sangil C. Sansón M. Clemente S. Afonso-Carrillo J. Hernández J. C. (2014). Contrasting the species abundance, species density and diversity of seaweed assemblages in alternative states: Urchin density as a driver of biotic homogenization. J. sea Res.85, 92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2013.10.009

46

Scheffer M. Carpenter S. R. (2003). Catastrophic regime shifts in ecosystems: linking theory to observation. Trends Ecol. Evol.18, 648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2003.09.002

47

Scheibling R. E. Lauzon-Guay J. S. (2010). Killer storms: North Atlantic hurricanes and disease outbreaks in sea urchins. Limnology Oceanography55, 2331–2338. doi: 10.4319/lo.2010.55.6.2331

48

Sweet M. (2020). “ Sea urchin diseases: Effects from individuals to ecosystems,” in Developments in aquaculture and fisheries science, vol. 43. (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 219–226.

49

Uthicke S. Schaffelke B. Byrne M. (2009). A boom–bust phylum? Ecological and evolutionary consequences of density variations in echinoderms. Ecol. Monogr.79, 3–24. doi: 10.1890/07-2136.1

50

Wickham H. Chang W. Wickham M. H. (2016). Package ‘ggplot2’. Create elegant data visualisations using the grammar of graphics. Version2, 1–189.

51

Zirler R. Schmidt L. M. Roth L. Corsini-Foka M. Kalaentzis K. Kondylatos G. et al . (2023). Mass mortality of the invasive alien echinoid Diadema setosum (Echinoidea: Diadematidae) in the Mediterranean Sea. R. Soc. Open Sci.10, 230251. doi: 10.1098/rsos.230251

Summary

Keywords

rocky reefs, echinoderms, recruitment, Eastern Atlantic, mass mortality event

Citation

Cano I, Lorenzo-Morales J, Bronstein O, Sangil C and Hernández JC (2025) Insights on the last sea urchin Diadema africanum mass mortality suggest a worldwide Diadematid pandemic in 2022-2023. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1665504. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1665504

Received

14 July 2025

Accepted

17 October 2025

Published

11 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Stelios Katsanevakis, University of the Aegean, Greece

Reviewed by

Alwin Hylkema, Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Sciences, Netherlands

Ezgi Dincturk, Izmir Katip Celebi University, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Cano, Lorenzo-Morales, Bronstein, Sangil and Hernández.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Iván Cano, ivancano_94@hotmail.com

† Present address: Iván Cano, Dpto. Biología Animal, Edafología y Geología, Universidad de La Laguna, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.