- 1School of Zoology, George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, Tel-Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

- 2St John’s Island National Marine Laboratory, Tropical Marine Science Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 3The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History and Israel National Center for Biodiversity Studies, Tel- Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

Marine biological invasions, driven by climate change and maritime transportation, threaten biodiversity by reducing species richness and altering their distribution. Global efforts to understand the physiological tolerance and limitations of invasive species are essential for predicting their spread and mitigating negative impacts. Ascidians (Chordata, Ascidiacea) are well-known as notorious invaders, spreading via ship hulls, and causing significant ecological and economic damage. Environmental changes are likely to accelerate their expansion, further challenging marine ecosystems. We examined the physiological responses of native (Red Sea) and non-indigenous populations (Mediterranean and South China Sea) of a widely-distributed solitary ascidian, Phallusia nigra, to changing environmental conditions, and developed a model predicting its potential spread. Our multi-factorial design of three salinities (35, 40, 43 PSU) and three temperatures (16°C, 25°C, 31°C) examined the survivability of cultured juveniles and the reproductive success of each population. In addition, blood-flow-current change rate was used as a stress indicator. Our findings indicate survival and larval development are strongly influenced by population origin: non-indigenous populations exhibited higher tolerance to a broader range of conditions. Salinity significantly affected the Mediterranean population, whereas temperature was the primary factor for the native Red Sea population. The introduced Singapore population showed notable survival at 25° and 31°C across all salinities. Low temperatures inhibited larval development and survival across all populations, highlighting a critical reproduction barrier. Our species distribution model based on these findings predicted the potential range expansion of P. nigra under current and future climate scenarios. Responses to climate change varied among populations, however, emphasizing the need to consider local adaptations in predictive models. This study highlights P. nigra’s adaptability and demonstrates the value of species distribution models in predicting the spread of invasive species, emphasizing the need for marine biosecurity strategies to mitigate their impacts in a changing world.

Introduction

Rising global temperatures, predicted to increase by 1.5-4°C by the end of the century (IPCC, 2023), and ocean acidification, with pH levels predicted to decrease from 8.2 to 7.8 (Feely et al., 2009), are persistently affecting marine organisms, causing shifts in abundance, and distribution and disrupting biodiversity (Gallardo et al., 2016; Nagelkerken and Connell, 2022; Poloczanska et al., 2016). Consequently, marine species are dispersing to higher latitudes and deeper waters in search of cooler habitats, while warm-water species are expanding their ranges as new niches become available. These transformations are reshaping marine communities on a global scale (Chaikin et al., 2022; Pinsky et al., 2019b; Poloczanska et al., 2016).

Invasive species are becoming increasingly dominant, disrupting delicate ecological balances by outcompeting native species, altering food webs, and modifying habitat structures, ultimately leading to a decrease in biodiversity (Lambert, 2007; Occhipinti-Ambrogi, 2007; Pinsky et al., 2019b; Zhan et al., 2015). Climate change is exacerbating this problem by creating favorable conditions for the introduction and establishment of invasive species (Biancolini et al., 2024; Sorte et al., 2010). For a species to invade successfully, it must survive through all life stages, from fertilization to adulthood, while each stage may respond differently to environmental stress (Bautista and Crespel, 2021). It is hypothesized that introduced species tend to perform better than native species under extreme conditions, as supported by numerous studies (Biedrzycka et al., 2022; Gewing et al., 2019; Gröner et al., 2011; Kenworthy et al., 2018). At the genetic level, invasive populations often exhibit adaptive traits, such as salinity-related variables that provide tolerance, elevated heat shock protein (HSP) expression levels that enable stress management, and epigenetic mechanisms that enhance resilience to climate change (Chen et al., 2021, 2024; Pineda and Turon, 2012). Additionally, stress in the new environment can drive rapid genomic or phenotypic changes, further facilitating the establishment of introduced species (Prentis et al., 2008).

In this study, we sought to address the knowledge gap in our understanding of how introduced marine organisms respond to environmental changes driven by global climate change. Marine ectotherms, in general, are more vulnerable to climate-change-induced stress than terrestrial species (Pinsky et al., 2019a). Predictions for the epipelagic layer (0–50 m) suggest that successful introductions will occur primarily in temperate zones, albeit with significant changes also expected in polar regions (Meyer et al., 2024). While temperature is a key driver of these shifts, oxygen levels and pH are also predicted to play dominant roles over the next two decades (Spence and Tingley, 2020). Although several studies have conducted multiple stressor experiments and explored under-represented taxa in order to fill these knowledge gaps, research has remained predominantly laboratory-based and is still scarce (Bass et al., 2021).

Ascidians (Chordata, Ascidiacea), a unique group of marine invertebrates, have attracted significant public attention due to the ecological and economic damage they cause as invasive species (Lambert, 2007; Zhang et al., 2020). Solitary ascidians, such as Styela clava and Ciona intestinalis, are recognized as significant biofouling organisms, causing substantial economic losses to aquaculture operations. These species can damage infrastructure, and compete with cultured species for resources, resulting in reduced productivity and increased maintenance costs (Darbyson et al., 2009; Utermann, 2021). They often exhibit rapid growth rates and high reproductive capacity, further enhancing their ability to establish and thrive in new habitats. Collectively, these characteristics contribute to the global success of ascidians as invasive species, making them valuable models for studying marine bioinvasions (Zhan et al., 2015).

The current study species, Phallusia nigra Savigny, 1816, is a widely-distributed solitary ascidian belonging to the order Phleobranchia, commonly found in tropical shallow waters (Rocha et al., 1999). The absence of epibionts on P. nigra’s dark shining tunic facilitates its identification and sampling. We consider the native range of P. nigra to be the Red Sea, from where it was first described by Savigny in 1816, although some researchers suggested that its origin may be the western Atlantic (Vandepas et al., 2015; Rocha pers. comm.). The distribution of P. nigra currently encompasses the Indo-Pacific Ocean, western Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, Red Sea, and Caribbean Sea (Goodbody, 1961; Rocha et al., 2017; Shenkar and Loya, 2009).

Here, we conducted a novel concomitant comparison of three populations from both native (Red Sea) and non-indigenous populations (Mediterranean and South China Sea) of P. nigra. Laboratory cultures were established from each site following a protocol designed for this study (Lee et al., 2025). Unlike previous studies that have often focused on a single parameter or relied solely on adult survival as a determining factor (Bae and Choi, 2025; Gewing et al., 2019; Jofré Madariaga et al., 2014; Renborg et al., 2014), we conducted the same multi-factorial exposure experiment on both juveniles and gametes to determine their ability to survive under global change scenarios.

Using our empirical results, we developed a species distribution model (SDM) for P. nigra to forecast its potential current and future distributions and help anticipate and potentially prevent its spread as an invasive species. We show that understanding the physiological tolerance of P. nigra and other invasive species is crucial for predicting their spread under changing conditions, such as rising temperature and altered salinity. Such information is essential for developing effective conservation strategies and biosecurity tools to mitigate the ecological impacts of these changes.

Materials and Methods

Animal collection

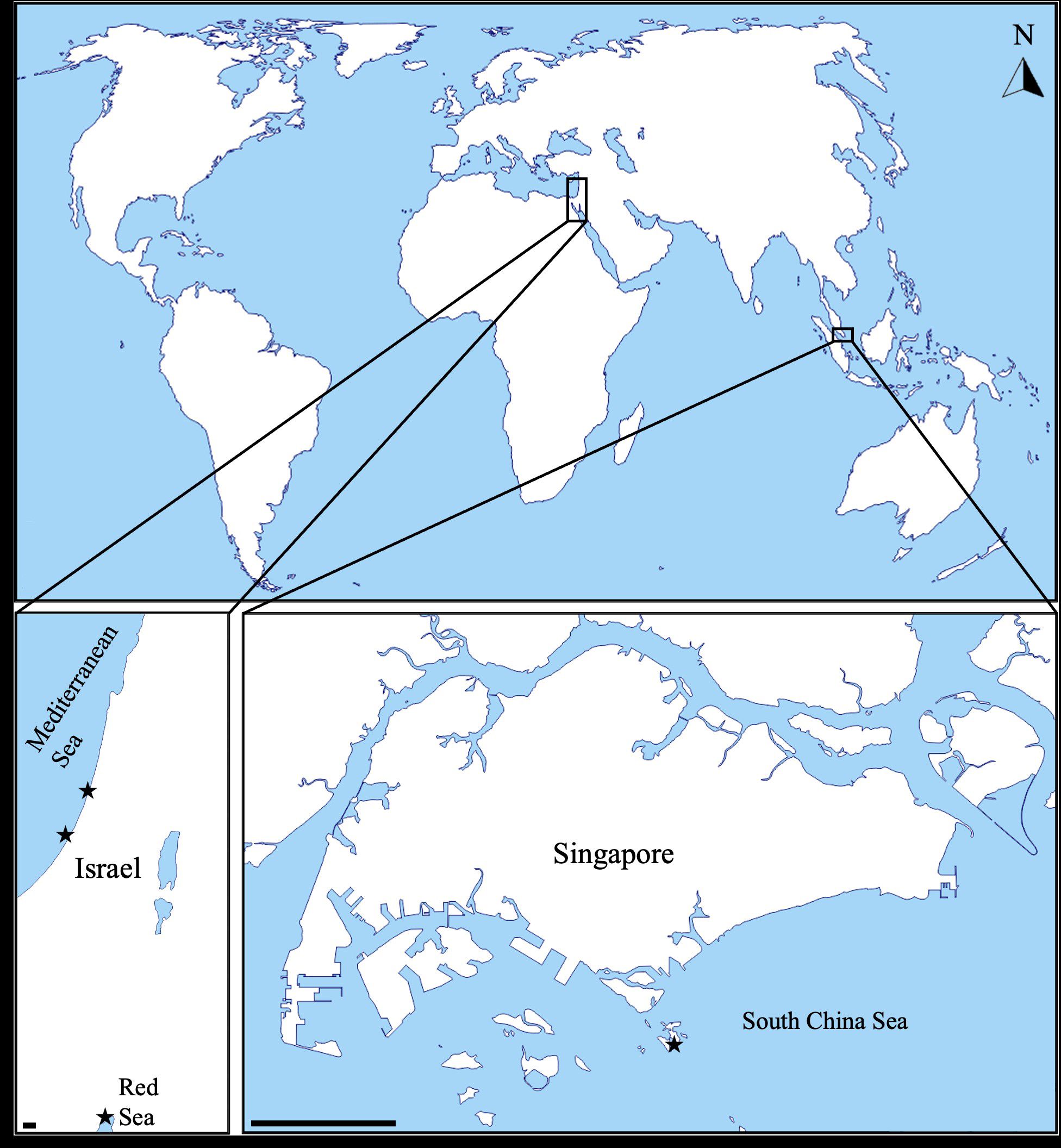

In Israel, adult individuals of P. nigra (n=10-15) were collected in April and May 2023 from two regions (Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea). Mediterranean individuals were collected either by retrieving ropes and buoys from Ashqelon Marina (31.6817°N, 34.5567°E) or by snorkeling and collecting from rocks at a depth of 0–2 meters at Bat Yam (‘Hof-a-sela’ beach, 32.0224°N, 34.7377°E). Red Sea individuals (n=10-15) were collected by SCUBA diving at a depth of 4–8 m from the underwater restaurant diving site (29.5474°N, 34.9536°E). After collection, individuals were transported submersed in seawater within plastic containers placed in a cooler, and brought to the aquaria at the Shenkar laboratory at The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel Aviv University. In Singapore, animals were collected from the Singapore Straits in February 2024, by snorkeling from floating pontoons off St John’s (1.2167°N, 103.8500°E) and Lazarus Islands (1.2230°N, 103.8542°E). Following collection, individuals were transported in pails with seawater to St John’s Island National Marine Laboratory (SJINML) flow-through aquaria. All animals were maintained in aerated aquaria until dissection, which took place either on the day of collection or within three days. Figure 1 presents the study sample sites.

Figure 1. Map of study sites. Mediterranean Sea, Israel (Bat Yam ‘Hof-a-sela’ beach and Ashqelon Marina). Red Sea, Israel (underwater restaurant diving site). South China Sea, Singapore (St John’s and Lazarus Islands). Scale: 10 km. Maps from d-maps.com.

Artificial fertilization and culture

Detailed protocols are available in Lee et al. (2025). Briefly, an incision was made along the dorsal side of the animal to remove the tunic and access the gonoducts. Eggs and sperm were extracted using a fine needle and Pasteur pipette or a 100 µm micropipette for smaller animals. Eggs and sperm from all individuals were initially combined in filtered seawater. Sperm was filtered through a 100 µm mesh to minimize self-fertilization and stored separately. All eggs and sperm were then pooled, mixed in a large jar, and placed in covered Petri dishes for incubation at 25°C for 24 hrs until tadpole larvae had developed.

Larvae were then transferred to new Petri dishes (20–30 per plate) and left undisturbed for 24 hrs for settlement and metamorphosis under a 12h:12h light:dark cycle. Starting three days post-fertilization, seawater in the Petri dishes was changed daily. At six days post-fertilization, settled larvae were transferred to aquaria with flowing water for daily feeding and maintenance.

Stress experiment on juvenile P. nigra

A month-long exposure experiment was conducted using lab cultures in two locations. At Tel Aviv University, juveniles derived from animals collected in the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea were used. In Singapore (St. John’s Island), juveniles originated from animals collected in the South China Sea. At the start of the experiment, juveniles were approximately 5 mm in size. Salinities and temperatures were selected based on predicted future environmental models (Soto-Navarro et al., 2020), to evaluate the potential range expansion of P. nigra.

The experiment employed three different temperatures: 16°C, 25°C, 31°C, and three different salinities: 35, 40, 43 PSU, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1. For the Singapore population the experimental salinities were slightly different due to local conditions: 28, 31, 35, and 40 PSU.

To achieve the desired temperatures, water baths were employed with a chiller system (HAILEA, model: HC-1000A) for the 16 °C and an aquarium heater (NEWA Therm eco) for the 25 °C and 31 °C. Salinity adjustments in Israel involved diluting or concentrating artificial seawater (ASW) from the Shenkar Lab aquaria system. In Singapore, fresh seawater (0.5 micron filtered) was used to prepare desired salinities either by diluting with de-ionized water or concentrated with aquarium sea salt (Red Sea Salts).

Each test salinity was conducted in 5 L aquaria with gentle aeration to generate currents. Partial water change (2 L) was conducted three times weekly with freshly prepared seawater. Each treatment from the Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea populations numbered 5–6 juveniles while 15 individuals were used in Singapore’s set up.

Juveniles were fed 1 mL of Phyto-blast food three times weekly. The experiment followed a 12h:12h light:dark cycle.

Measurements comprised: (1) survival rates, assessed three times weekly; and (2) blood flow patterns, assessed weekly. Survival was determined by observing siphon contractions under a dissecting scope (Nikon SMZ18); the scope was unnecessary for larger juveniles. Blood flow patterns were recorded from 5-min videos analyzed for flow direction changes using NIS Elements D software and a timer.

Stress experiment on P. nigra reproduction products

Larval development success was tested under the same temperature (16°C, 25°C, 31°C) and salinity (35, 40, 43 PSU) conditions as in the juvenile experiments (Supplementary Figure S2A). For Singapore, salinities were adjusted to 28, 31, 35, and 40 PSU due to the tropical conditions. A preliminary experiment conducted in December 2023 at the Inter-University Institute (IUI) in Eilat, Israel, had determined larval development times under the target temperatures.

Oocyte and sperm extraction followed the protocol described in the “Artificial Fertilization and Culture” section. Oocytes (10–15 per well; ~60 per treatment) were dispensed into six-well plates, with 1 mL of sperm mixture added per well subsequently (Supplementary Figure S2B). Filtered seawater at the appropriate salinity was added to each well resulting in a total volume of 6 mL. The plates were covered and incubated at 16°C or 31°C, or kept in an air-conditioned lab (24-25°C), and maintained in darkness. Development success was classified as either unfertilized, undeveloped/abnormal, larva, or settled.

Statistical analysis of stress experiments

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for each population (Singapore, Mediterranean, and Red Sea) and compared using log-rank tests. Due to assumption violations, including the proportional hazards assumption, a Cox proportional hazards model was not used. Instead, a negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) was used to analyze time to death (in days) for individuals that did not survive, with salinity, temperature, and origin as predictors. This approach addressed overdispersion in the count data.

For blood flow reversal patterns, a Poisson GLM assessed treatment differences. The response variable was time to reversal (in seconds), with salinity, temperature, and experiment day as predictors. The control treatment was 25 °C and 40 PSU, and assumptions of residual normality and homoscedasticity were satisfied. For the Singapore population, a Linear Mixed-Effects Model (LMM) was used to analyzed repeated measures, as this population included repeated measurements of the same individuals over the experimental period. Fixed effects were temperature, salinity, and experiment day, with individuals as a random effect. The control treatment was 25 °C and 31 PSU, reflecting Singapore’s lower salinity. Assumptions of residual normality, homoscedasticity and multicollinearity were met.

All analyses were conducted in R (v4.2.2). Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests used the ‘survival’ package and the ‘survfit’ and ‘survdiff’ functions (Therneau and Lumley, 2023). GLMs were run using the ‘Mass’ package with the ‘glm.nb’ and ‘glm’ functions, while LMM employed the ‘lme4’ package using the ‘lmer’ function (Bates et al., 2015). Model performance (Nagelkerke’s R² for GLMs; conditional and marginal R² for LMMs) was evaluated using the ‘performance’ package (Lüdecke et al., 2021).

Larval development was analyzed separately for each population (Red Sea, Mediterranean, Singapore) due to the distinct experimental conditions and responses across populations. A binomial generalized linear model (GLM) assessed larval development success (binary: success vs. failure), defined as larvae reaching the fully developed or settled stage. Non-fertilized eggs, undeveloped larvae, and dead larvae were categorized as failure. Control treatments were 25°C/40 PSU for Red Sea and Mediterranean populations and 25°C/31 PSU for Singapore, to reflect local conditions. Models were fitted using the ‘stats’ package, with the ‘glm’ function (Bates et al., 2015). Tjur’s R² from the ‘performance’ package (Lüdecke et al., 2021) was used to assess model fit.

Potential distribution of P. nigra under a global change scenario

The main goal of this analysis was to estimate the potential distribution of the ascidian P. nigra by integrating experimental survival data from three populations originating from distinct marine ecoregions (Red Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and Singapore). This approach allowed us to evaluate how temperature and salinity jointly influence species survival across current and future ocean conditions.

We first developed a global coastal map of temperature and salinity. By integrating the empirical survival rates of juveniles and larvae from our experiments with these coastal environmental conditions, we predicted the survival potential of P. nigra under both current and future climate scenarios.

To parameterize coastal environmental conditions, we extracted sea surface temperature (SST) and sea surface salinity (SSS) data from the MPI-Es12-2-HR climate model under the SSP585 scenario (Schupfner et al., 2019). To characterize present and future coastal conditions and provide insights into how temperature and salinity may shift over time, we downloaded data for two climate periods: current (2015-2024) and future (2075-2100). Coastal areas were defined using bathymetry data, classifying grid cells with depths of ≤100 m to reflect proximity to coastal areas. To ensure that all relevant coastal grid cells were included, we applied a 3×3 neighborhood filter, designating any coastal cell adjacent to missing values (i.e., land pixels) as coastal. We then extracted SST and SSS values for each coastal grid cell. This part was performed with ‘ncdf4’ (Pierce, 2024) and ‘terra’ (Hijmans et al., 2025) packages in R. To assess seasonal patterns, we aggregated data by month and computed the maximum and minimum SST and SSS for each coastal location for both periods.

For each coastal coordinate, we estimated the survival rates of juveniles and larvae from each population using the findings from our controlled experiments, specifically at seven days post-exposure. In particular, we fitted Generalized Additive Models (gam) for each population and life stage, with survival as a binary response variable and temperature and salinity as continuous explanatory variables. Survival was modeled using a binomial distribution with a logit link function. The model was fitted using the “gam” function from the ‘mgcv’ R package (Wood, 2023). Using the gam models, we predicted the survival of juveniles and larvae from each population for every combination of temperature and salinity. Although the models were fitted for the observed experimental conditions, we also predicted survival across a broader temperature range (0-40°C) and salinity range (0–45 PSU) to assess survival potential beyond those of the experimental conditions.

For each population and life stage, we predicted the mean annual survival from monthly predictions at each coastal coordinate, using the corresponding gam model. For larval distribution maps, predictions were restricted to months in which the mean temperature exceeded 25°C, to account for seasonal reproduction. Additionally, we mapped the projected change in survival by the end of the century (future survival minus current survival). Each pixel in the final maps presents a spatial resolution of 50 km².

Additional R packages used in the analysis included ‘dplyr’ (Wickham et al., 2023), ‘lubridate’ (Spinu et al., 2024), ‘data.table’ (Barrett et al., 2024). Visualization and plotting were carried out using the ‘ggplot2’ (Wickham et al., 2024) and ‘maps’ (Deckmyn, 2024).

Results

Stress experiment on juvenile P. nigra

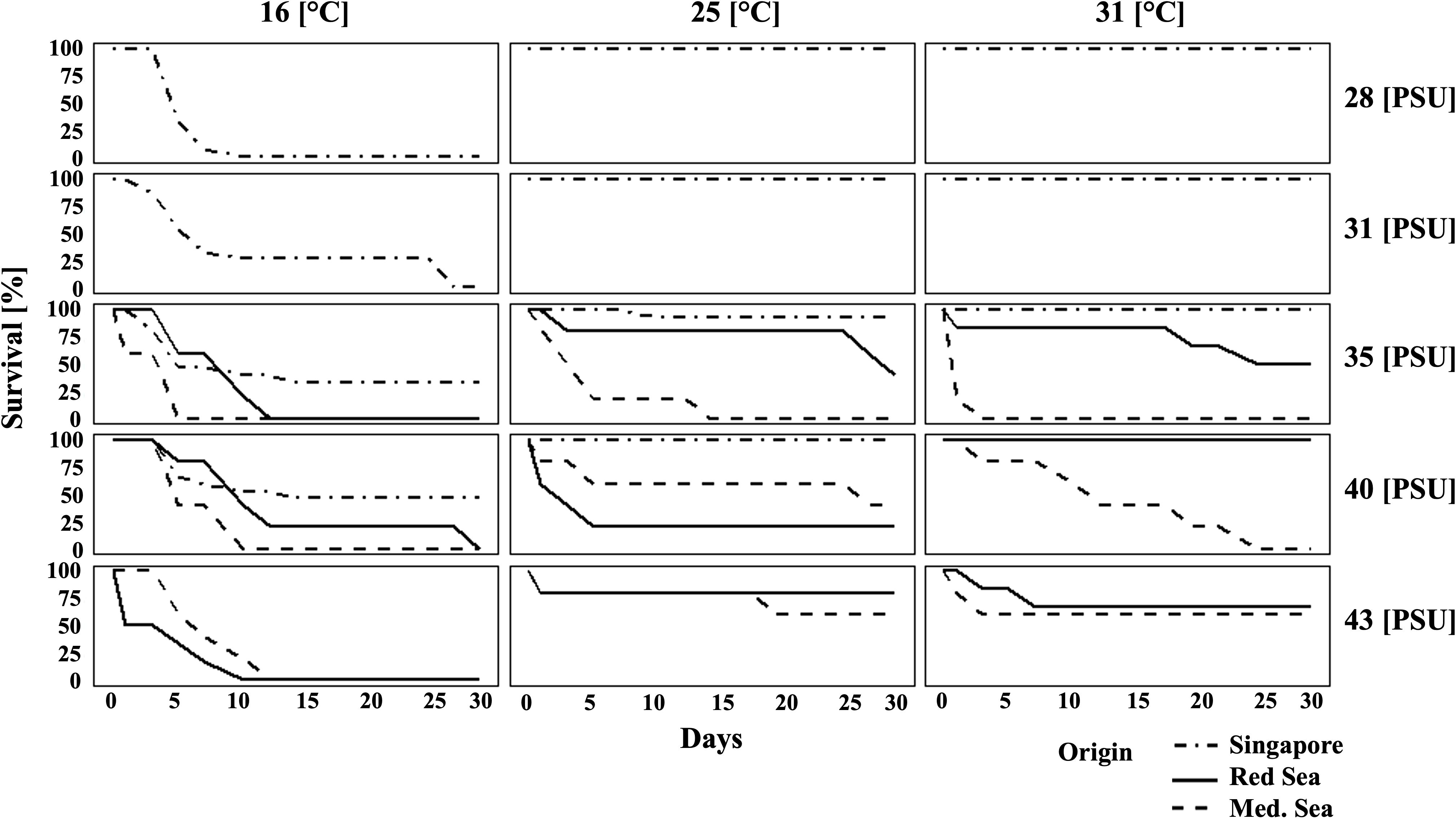

Survival rates during the stress experiment are given in Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests for each population revealed specific significant factors affecting survival: salinity for the Mediterranean population and temperature for the Red Sea and Singapore populations (p < 0.01). A General Linear Model (GLM) with a negative binomial distribution across all populations indicated significantly lower survival rates at 16 °C compared to 25 °C and 31 °C, between which no significant difference was observed (p < 0.01, R² = 0.622). Higher salinities (40, 43 PSU) were associated with increased survival (p < 0.01). Population origin also influenced survival, with the Red Sea and Singapore populations demonstrating significantly higher survival rates than the Mediterranean population (p < 0.01).

Figure 2. Survival rates of juveniles during the stress experiment. Columns represent different temperatures (16 °C, 25 °C, 31 °C), and rows represent different salinities (28, 31, 35, 40, 43 PSU). The continuous line represents the Red Sea population, the dashed line represents the Mediterranean Sea population, and the dot-dashed line represents the Singapore population. Sample sizes: N = 5–6 for Red Sea and Mediterranean Sea populations, and N = 15 for the Singapore population for each treatment.

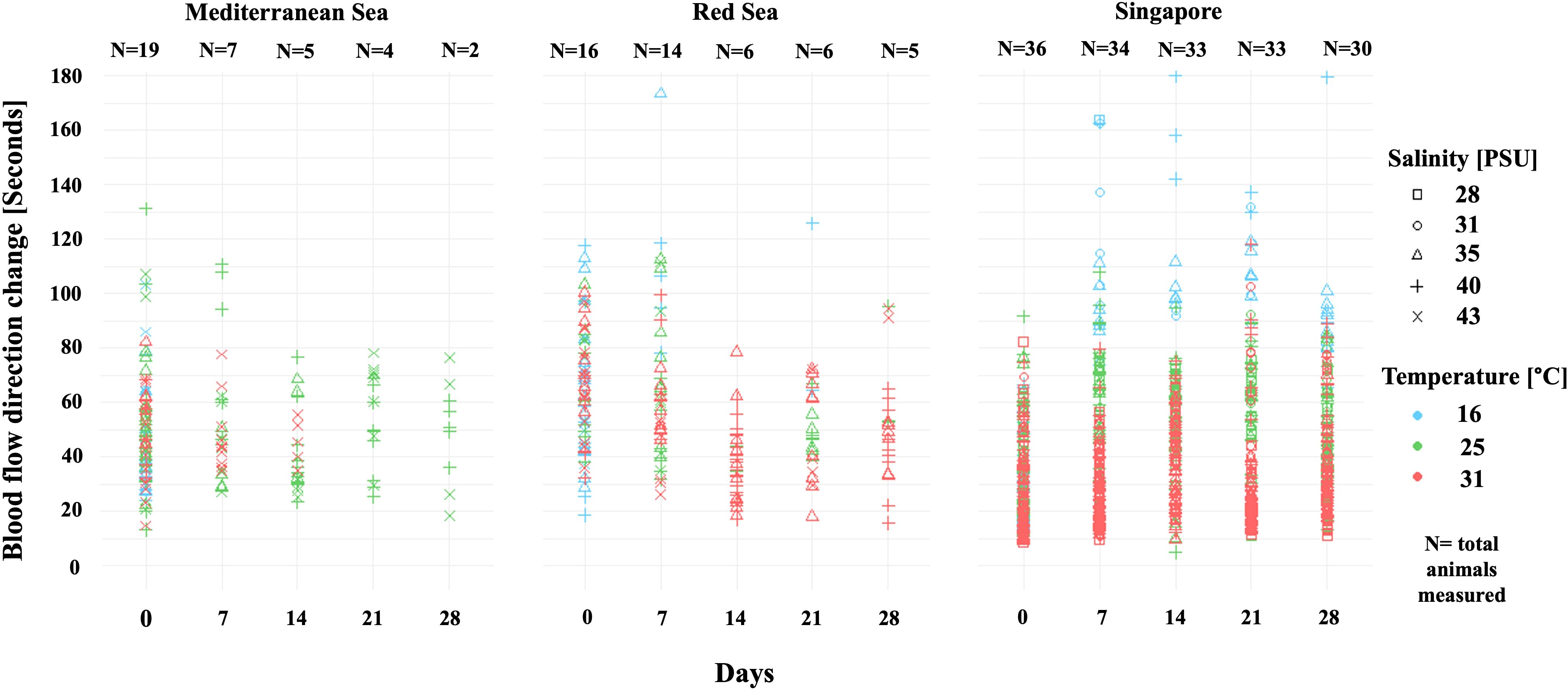

A Poisson GLM for all blood flow direction change data (Figure 3) revealed significant effects of temperature, salinity, and time. Blood flow was significantly slower at 16 °C and faster at 31 °C (p < 0.01, R2 = 0.984). Salinities of 28 and 35 PSU accelerated blood flow, while 43 PSU reduced it (p < 0.01). Blood flow direction change significantly decreased over the experimental period (p < 0.01). The Singapore population exhibited the fastest rates, followed by the Mediterranean and Red Sea populations (p < 0.05). Average blood flow direction changes across temperatures were 82.47 ± 21.56 for 16 °C; 51.72 ± 2.03 for 25 °C; and 37.29 ± 8.85 for 31 °C (across all populations).

Figure 3. Scatterplot of blood flow direction change in seconds for each population and treatment (sample size denoted above). Colors distinguish between temperatures, and shapes distinguish between salinities.

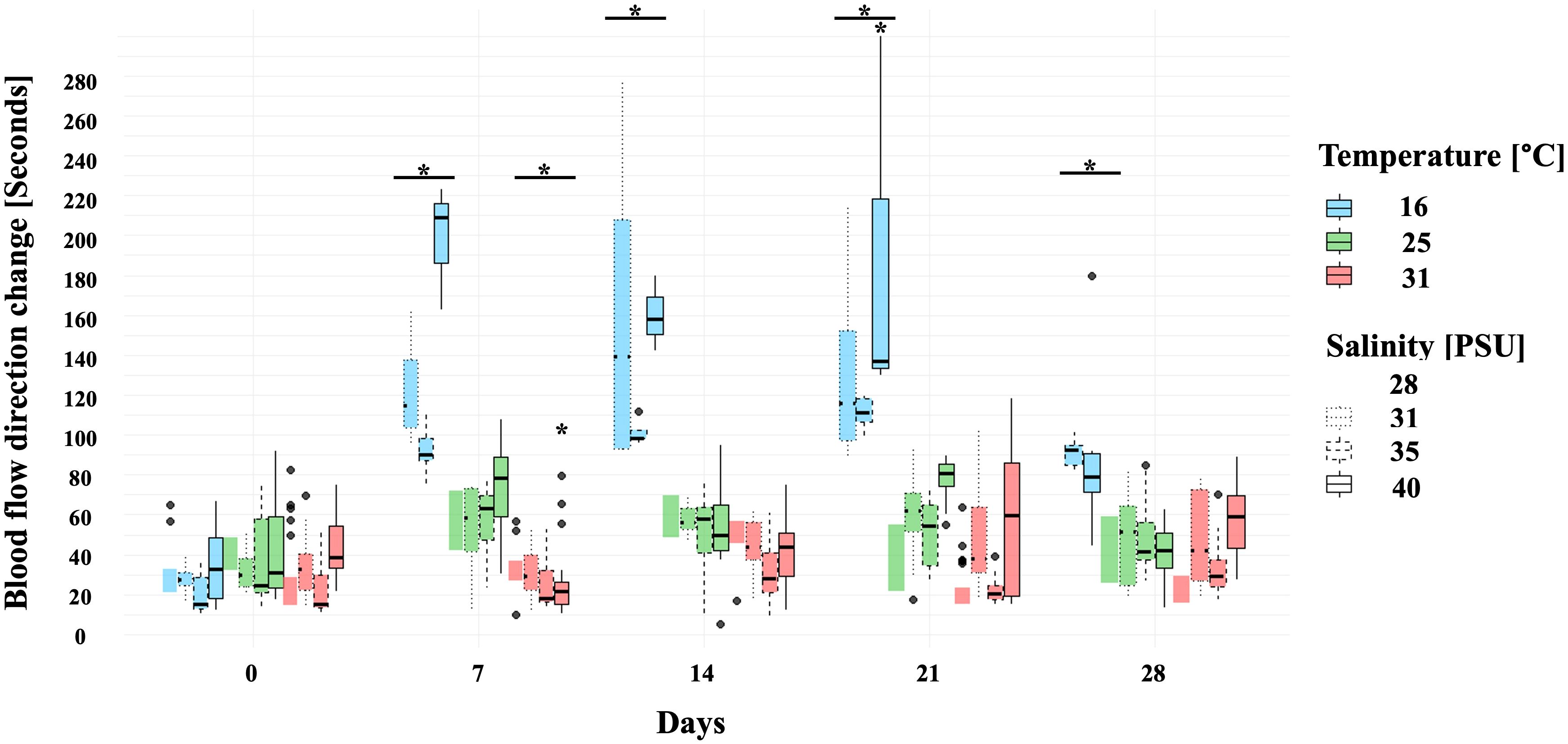

Repeated measures from the Singapore population enabled a Linear Mixed-Effects Model (Figure 4). Day of measurement was the most significant factor affecting blood flow rate, which decreased over time (p < 0.05, conditional R2 = 0.948), with variance among individuals accounted for most variability (marginal R2 = 0.157). Blood flow was significantly slower at 16 °C and faster at 31°C compared to the control (25°C, 31 PSU; p < 0.01). Salinity and time interactions also influenced blood flow rate. At 25°C, faster rates were observed at 28 PSU on Day 21 (p < 0.0005) and at 40 PSU on day 28 (p < 0.05). Moreover, the combination of 31°C and 40 PSU on Day 7 accelerated blood flow, while 16°C and 40 PSU on day 21 slowed it (p < 0.05), demonstrating the strong effect of temperature.

Figure 4. Blood flow direction change in individuals from Singapore in seconds for each week of the experiment. Asterisk (*) indicates significant differences in treatments compared to the control (p < 0.05). Line in box = median; box = 25th to 75th percentiles: bars = min and max values. Points outside this range are considered outliers and are plotted as individual dots. Colors distinguish between temperatures, and box borders distinguish between salinities. Sample size: N = 3 individuals per treatment.

Stress experiment on P. nigra reproduction products

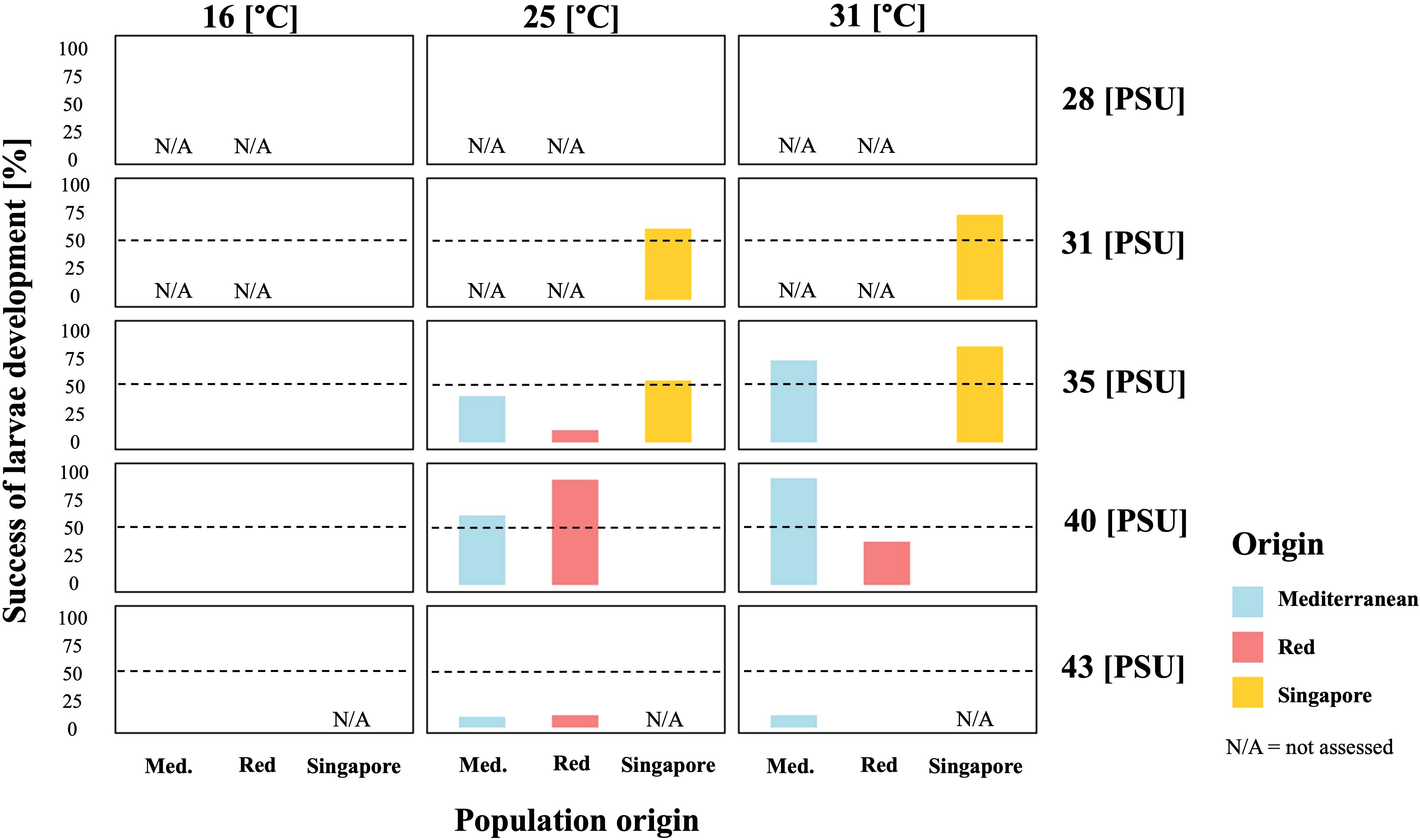

Figure 5 presents larval development success under stress conditions across the three populations. Separate General Linear Models (GLMs) with binomial distributions revealed distinct population-specific responses. For the Singapore population, larval development was significantly enhanced at higher temperature (31 °C) and salinity (35 PSU) (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, R2 = 0.422). The Red Sea population exhibited decreased larval development at higher temperature (31°C) and salinities of 35 and 43 PSU (p < 0.01, R2 = 0.454). For the Mediterranean population, salinity was the primary factor affecting development, with reduced success at 35 PSU and 43 PSU (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, R2 = 0.262).

Figure 5. Larval development during stress exposure. N/A represents combinations that were not examined, while blank indicates 0% development. The color index distinguishes between populations (N = 60 larvae per treatment). Dashed line represents the 50% threshold.

Overall, the results highlight low temperature as a reproduction barrier across all populations. The Red Sea population exhibited a narrow salinity tolerance, limiting successful reproduction at higher salinities, whereas the Singapore and Mediterranean populations demonstrated greater tolerance to lower salinity.

Potential distribution of P. nigra under a global change scenario

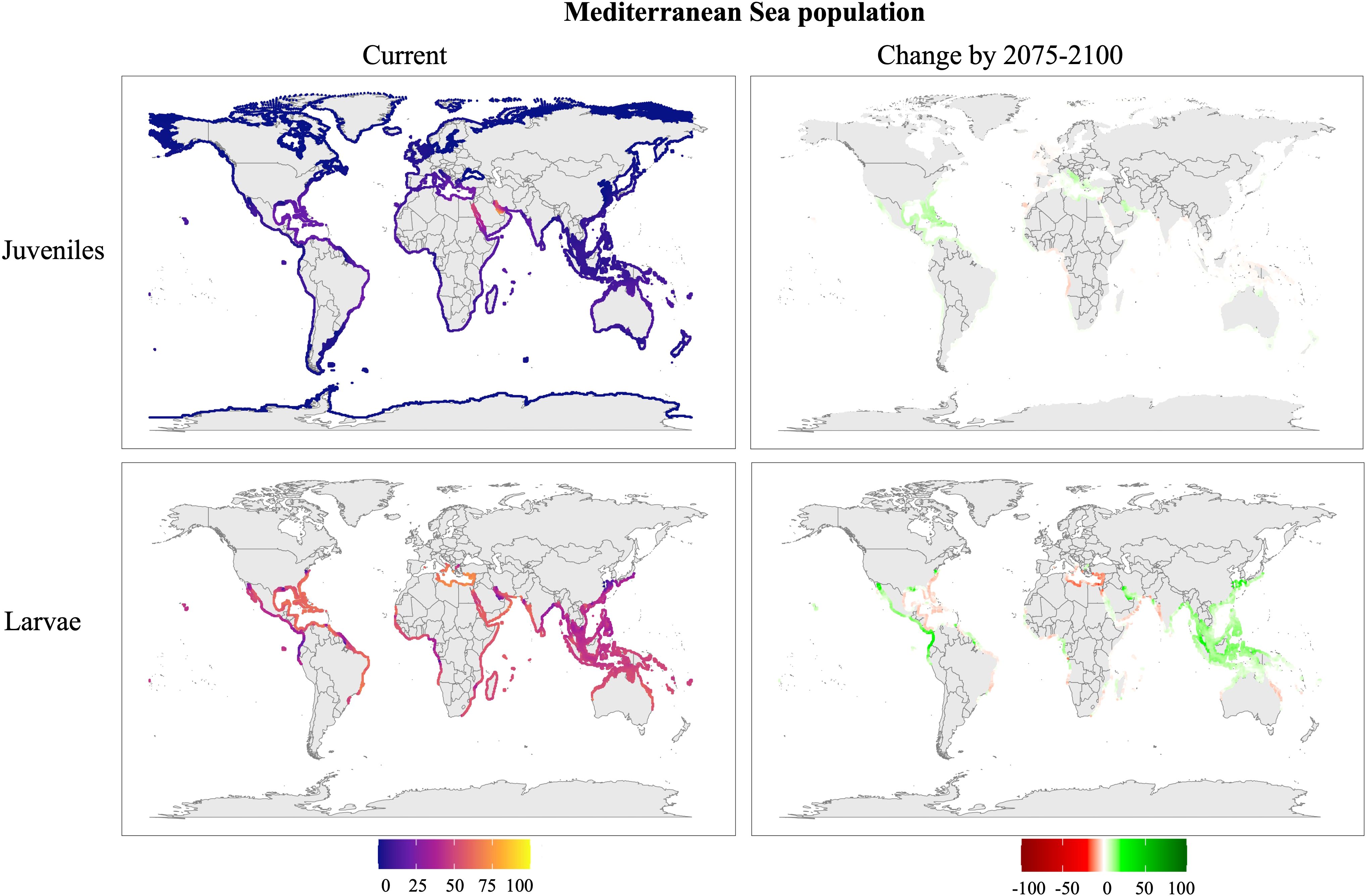

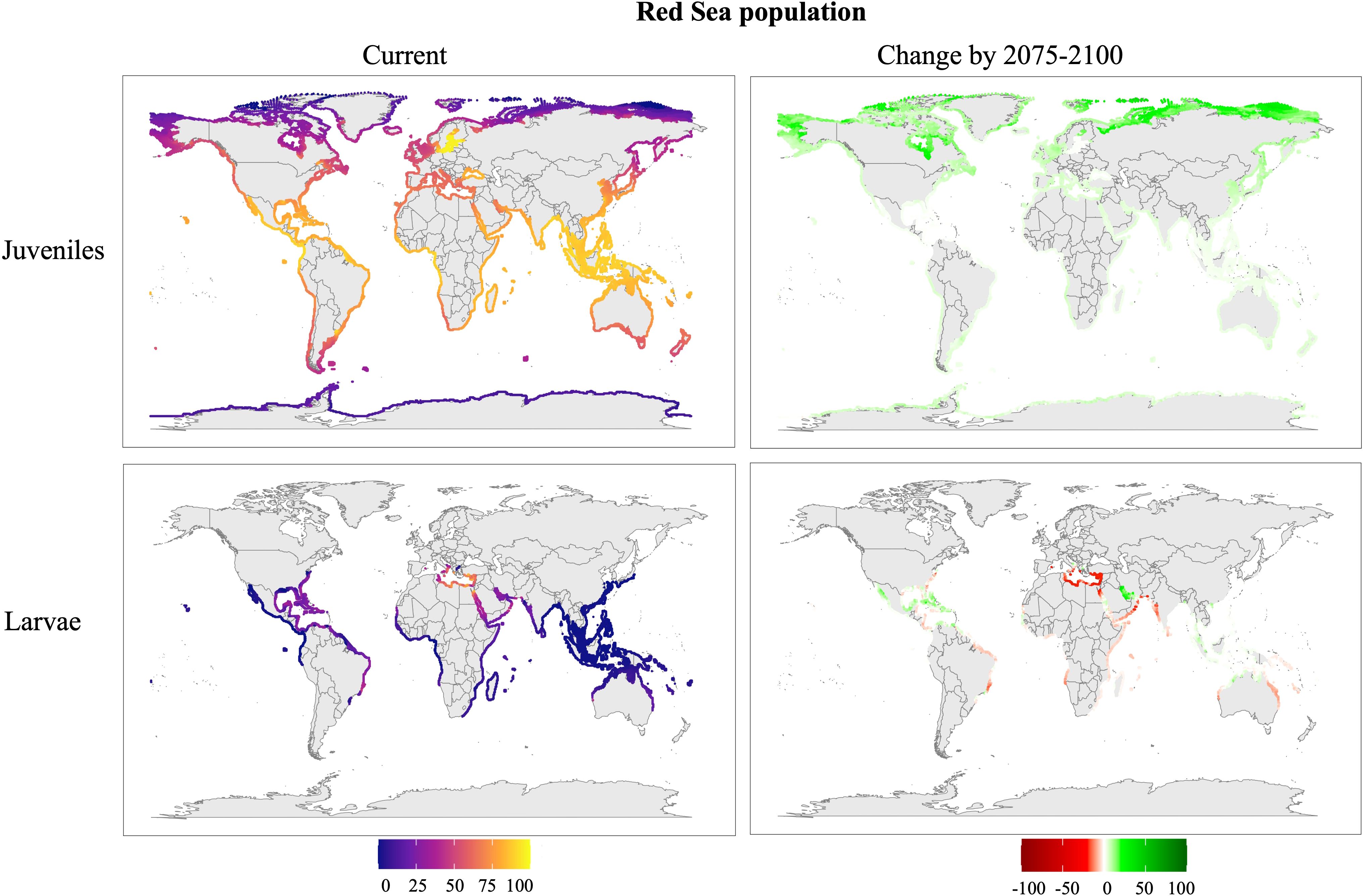

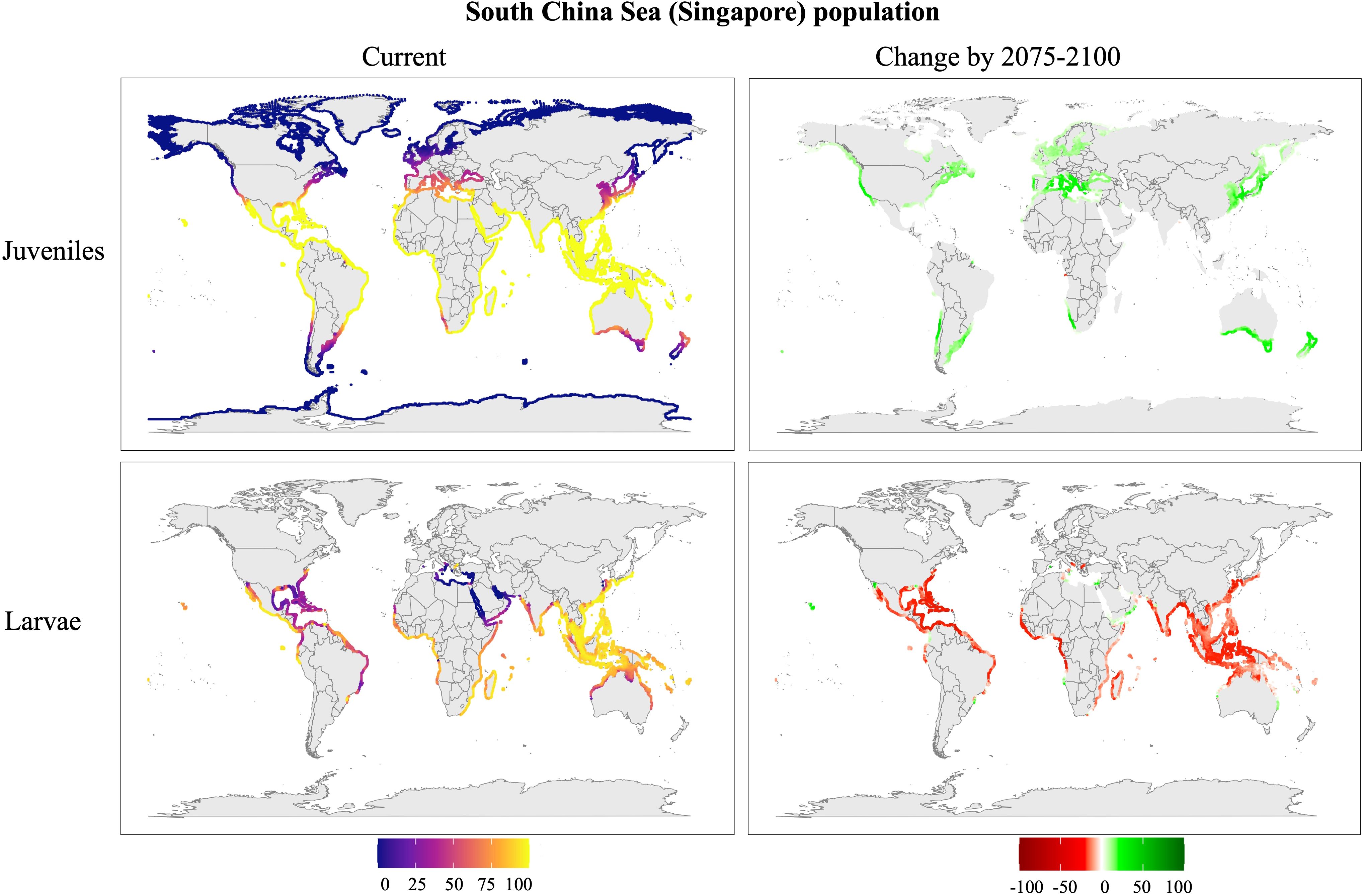

Figures 6-8 illustrate the predicted mean survival rates under the present conditions and the projected changes in survival by the end of the century (2075-2100). The larval distribution maps consider only temperatures above 25°C, to reflect seasonal reproduction.

Figure 6. Predicted distribution of the Mediterranean Sea population of Phallusia nigra under the SSP5-8.5 climate scenario. Maps represent current conditions (2015–2024) and change in survival for future projections (2075–2100). Larval distributions were restricted to regions with temperatures exceeding 25 °C to account for seasonal reproduction. Survival rates (%) indicate the mean survival predicted by the model.

Figure 7. Predicted distribution of the Red Sea population of Phallusia nigra under the SSP5-8.5 climate scenario. Maps represent current conditions (2015–2024) and change in survival for future projections (2075–2100). Larval distributions were restricted to regions with temperatures exceeding 25 °C to account for seasonal reproduction. Survival rates (%) indicate the mean survival predicted by the model.

Figure 8. Predicted distribution of the Singapore population of Phallusia nigra under the SSP5-8.5 climate scenario. Maps represent current conditions (2015–2024) and change in survival for future projections (2075–2100). Larval distributions were restricted to regions with temperatures exceeding 25 °C to account for seasonal reproduction. Survival rates (%) indicate the mean survival predicted by the model.

Mediterranean Sea population (Figure 6): Survival of juveniles in the Mediterranean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, with higher survival rates in the Red Sea and even higher survival in the Persian Gulf. Larvae demonstrate the potential to survive in new regions, including the eastern Pacific Ocean, the Philippine Sea (extending from Japan to Australia), and both African coasts, reaching as far as Madagascar. Future projections indicate increased juvenile survival in the Mediterranean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. Larval survival is projected to increase in the Philippine Sea but decrease in the Mediterranean Sea.

Red Sea population (Figure 7): Juveniles demonstrate a broader expansion to both northern and southern latitudes, with high survival rates in the western and eastern Atlantic (including the African coasts), the Philippine Sea, the Great Barrier Reef, and New Zealand. In contrast, the survival of larvae is more limited, restricted to areas such as Brazil, the Caribbean, the Red Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Persian Gulf. Future projections suggest increased juvenile survival, with expansion extending to southern Australia and higher latitudes. Larval survival, however, is expected to decline in the Mediterranean Sea.

Singapore population (Figure 8): Juveniles exhibit high survival rates, particularly in coastal areas around the equator, extending north to the Mediterranean Sea and Japan and south to Madagascar, Brazil, and Australia. Larval survival is more restricted, with success primarily in the Philippine Sea, the eastern Pacific, and the western African coasts. Future projections indicate that juvenile survival will expand to northern and southern latitudes, including most of the Mediterranean Sea, Japan, southern Australia, and New Zealand. Larval survival, however, is expected to decline in its current range but may persist in new areas such as the Great Barrier Reef, Hawaii, and the Eastern Mediterranean Sea.

Discussion

In the world’s rapidly changing oceans in which rising temperatures and shifting salinity regimes are reshaping ecosystems, non-indigenous species that become invasive represent a significant threat. Our findings reveal that the solitary ascidian Phallusia nigra is capable not only of surviving extreme regimes, but also of overcoming previous reproduction barriers, facilitating its adaptation to novel environments. Our findings reveal the complex interplay between an organism’s physiology, environmental changes, and invasion dynamics. Fouling organisms are of great concern due to their ability to be transported across regions. With the acceleration of global trade and the intensification of climate change, the spread of non-indigenous species is expected to increase, potentially leading to a decline in local biodiversity (Castro et al., 2022; Chapman et al., 2017; Pinsky et al., 2019b). Understanding the environmental conditions that support ascidian reproduction and survival is key to predicting their potential spread and future distribution.

Our results indicate that the larval development and survival of P. nigra is strongly influenced by the origin of the parent population. All populations examined in this study were sensitive to low temperature, with no larval development observed at 16 °C and with juvenile survival rates at 16 °C ranging from 0-50%. This sensitivity could be attributed to the tropical origin of P. nigra, where tolerance to colder water is not required; and it may represent a trait that populations must evolve over time. Such sensitivity contrasts with the wild Mediterranean population, which regularly experiences such temperatures during winter. However, this contradiction could also be due to the experimental design, which lacked a gradual acclimation period, and/or the relatively small size of the tested individuals (~5 mm in length), whose tunics are more delicate compared to the larger (~5–7 cm in length) and tougher individuals present in the wild during winter. Despite this, the non-indigenous Mediterranean population demonstrated high larval development rates at 35 and 40 PSU, with lower rates at 43 PSU. The occurrence of some larval development at 43 PSU suggests a degree of adaptation to high salinity, and these rates may increase over time due to genetic adaptations and selection (Prentis et al., 2008). The non-indigenous Singapore population demonstrated high development rates at salinities of 31 and 35 PSU but not at the higher level (40 PSU), and exceptional survival across all salinity levels regardless of temperature, except at the low temperature, possibly due to the establishment of a subpopulation with specific genetic adaptations to salinity fluctuations. This suggests that the Singapore population may have undergone selection for tolerance to moderate salinity variations while remaining sensitive to more extreme conditions such as high salinity, reflecting a potential genetic differentiation that supports its successful establishment in non-native environments. In contrast, the native Red Sea population faced a significant salinity reproduction barrier, with most larvae developing at 40 PSU, and very few at 35 or 43 PSU, and only at 25 °C. The juveniles nonetheless exhibited high tolerance to a salinity of 35 PSU, despite this being lower than that which they typically encounter in their natural habitat.

Previous studies have reported the optimal survival conditions of P. nigra as 25-32 °C and 30–35 PSU in Singapore (Lee S. pers. Comm.) and 17-30 °C, 30–35 PSU in Brazil (Rocha et al., 1999, 2017), while P. nigra populations in Brazil seem to be highly sensitive to extreme salinities, which hinder its reproduction, under both high (45 PSU) and low (20 PSU) conditions (Rocha et al., 2017). However, those studies examined temperature and salinity separately, in contrast to the current novel multi-factorial study. The levels of these two factors are critical for marine environments, as salinity and temperature have been shown to significantly influence survival in simulations of shipping voyages involving tropical and subtropical ascidians (Bereza and Shenkar, 2022). Multiple stressor experiments are essential to more accurately assess the complexity of marine environments and to gain a better understanding of how climate change might impact marine organisms (Bass et al., 2021). An earlier global study (Lenz et al., 2011) compared native and non-indigenous species within the same groups—specifically bivalves, ascidians, and crustaceans—and found that the introduced species generally exhibited a broader tolerance range for both temperature and salinity than their native counterparts. A study on the green crab Carcinus maenas, conducted on three populations along the European coast, revealed that their larvae exhibit a broad range of tolerance to temperature and salinity, suggesting potential local adaptation (Šargač et al., 2022), similar to the non-indigenous P. nigra populations in the present study.

In addition to examining survival rates, the current study employed blood flow analysis as a tool to estimate physiological response. The results revealed a slower rate at 16°C, characterized by increased time to change direction, compared to a faster rate at 31°C, which aligns with the elevated metabolic activity revealed at higher temperatures (Ai-Li et al., 2008). Additionally, lower salinities (28, 35 PSU) accelerated blood flow, while higher salinity (43 PSU) slowed it down. The observed decrease in blood flow rate over the experimental period suggests that such analysis offers an informative tool for assessing stress in ascidians, as suggested by Dijkstra et al. (2008).

P. nigra records from the Persian Gulf (Iran, Qatar) on both artificial and natural substrates (Al-Khayat and Ibrahim, 2001; Monniot and Monniot, 1997) further indicates the ability of this species to survive in such extreme conditions over time, such as water temperatures in this region span from 18 °C to 37 °C and salinity ranging from 43 to 46 PSU (Afkhami et al., 2012; Alosairi et al., 2020; Naser, 2017). Such adaptations in introduced species can take place through within-generation phenotypic plasticity, enabling the species to survive and eventually reproduce in their new environment. Trans-generational plasticity may also be a factor in which the offspring inherit traits or mutations that enhance their ability to survive in a new environment (Dyer et al., 2010). For marine invertebrates, plasticity is most commonly induced by changes in the abiotic environment, primarily influencing their morphology (Padilla and Savedo, 2013).

Our study has demonstrated how P. nigra can rapidly adapt to different regions with distinct environmental conditions, including extreme conditions. The distribution maps of current and future scenarios present the locations where P. nigra is likely to survive if it reaches new areas – a scenario made increasingly probable by the expanding global shipping network (Chapman et al., 2017), with P. nigra having been detected to date as hull fouling in Israel, Cyprus, and Greece (Gewing and Shenkar, 2017; Kondilatos et al., 2010; Ulman et al., 2017). The differences detected for the three studied populations’ future distribution highlight the species’ ability for adaptation to diverse environmental conditions.

Although the modeling framework was global, survival parameters were derived from population-specific experiments, with salinity ranges for the Singapore population differing from those of the Red Sea and Mediterranean populations. These differences reflect local environmental conditions and limit direct global comparability. Accordingly, our maps should be viewed as population-based projections that illustrate how local adaptation and physiological tolerance shape potential range expansion under climate change.

Our maps represent the predicted mean survival rates, revealing a concerning pattern of potential expansion. While the unexpectedly low survival found for the Mediterranean population may be due to our small sample size, this nonetheless suggests that natural selection will favor the most resilient individuals, accelerating adaptation in this region. More alarmingly, Mediterranean larvae have demonstrated the potential to survive in many other regions, highlighting the hidden risk of future invasions beyond its current range. The Red Sea population, despite displaying the most restricted larval survival, exhibited exceptionally high juvenile resilience, indicating that under favorable conditions, these individuals could still colonize new regions. Perhaps the most striking finding is that of the extreme resilience of the Singapore P. nigra population, which thrives across a vast range of environmental conditions. With Singapore’s port ranking among the busiest in the world, this population poses a global invasion threat, with shipping routes offering stepping stones to new habitats. Given its tolerance and access to over 600 ports worldwide, under suitable conditions P. nigra could soon establish in unexpected ecosystems, from temperate coastlines to tropical waters.

Invasive ascidians pose a serious threat to marine ecosystems in rapidly colonizing available substrates and outcompeting the sessile native species for space and resources (Lambert, 2007; Zhang et al., 2020). Their fast growth and high filtering ability can disrupt local food webs, reducing biodiversity and altering ecosystem dynamics. Economically, they impact aquaculture by suffocating shellfish through fouling ropes, nets, and other structures. They also contribute to biofouling in ports, increasing maintenance costs for marine industries. P. nigra exemplifies this threat, demonstrating a remarkable resilience and rapid geographic spread over the last century, raising concerns about its potential both to disrupt the delicate ecological balance and impose an economic burden.

The current study has presented a novel approach to understanding marine bioinvasions in a rapidly changing world. By examining the same species from three different localities, we identified the differential physiological tolerances of each population and modeled its potential distribution under future global change scenarios. Our findings highlight the varying survival potential of distinct populations and identify high-risk regions for this species’ future establishment. As climate change progresses and global shipping networks continue to expand, the threat of invasive ascidians becoming widespread is no longer hypothetical – it is imminent. Such insights as those obtained here are crucial for preventing the proliferation of nuisance species and mitigating biodiversity loss in marine ecosystems. We strongly recommend future research focusing on multi-stressor experiments and molecular analyses, to uncover the genetic mechanisms driving the rapid adaptation and success of invasive species.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15425963.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because experiments on invasive ascidians do not require an ethical approval in Singapore and Israel.

Author contributions

AU: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SL: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. ST: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Resources. OL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Resources. NS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the ISF grant number (535/23) to NS.

Acknowledgments

We are greatful to L. Novak and the Shenkar lab members for their assistance in the field, and to N. Paz for editorial assistance. We also thank the St. John’s Island National Marine Laboratory for providing the facility necessary for conducting our research in Singapore. Supplementary Figures were created with BioRender.com, with permission. Original maps were taken from d-maps from the following URL’s: https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=334&lang=en, https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=602&lang=en, https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=3266&lang=en.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1666759/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Experimental setup for Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea populations. Each population was allocated to nine aquariums, covering all combinations of temperatures and salinities. Each treatment included N = 5–6 individuals. The Singapore population had slightly different experimental salinities (28, 31, 35, and 40 PSU) to reflect its native tropical conditions, with n = 15 juveniles per treatment.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Schematic representation of the experimental setup for P. nigra gametes. (A) Overall setup of the treatments (B) Oocytes and sperm addition to each well.

References

Afkhami M., Ehsanpour M., Forouzan F., Bastami K. D., Bahri A. H., and Daryaei A. (2012). Distribution of ascidians Phallusia nigra (Tunicata: Ascidiacea) on the north coast of the Persian Gulf, Iran. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 5, e95. doi: 10.1017/S1755267212000772

Ai-Li J., Jin-Li G., Wen-Gui C., and Chang-Hai W. (2008). Oxygen consumption of the ascidian Styela clava in relation to body mass, temperature and salinity. Aquac. Res. 39, 1562–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2008.02040.x

Al-Khayat J. and Ibrahim I. I. (2001). Fouling in the pearl oyster beds of the Qatari water, Arabian Gulf. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 5, 145–163. doi: 10.21608/ejabf.2001.1714

Alosairi Y., Alsulaiman N., Rashed A., and Al-Houti D. (2020). World record extreme sea surface temperatures in the northwestern Arabian/Persian Gulf verified by in situ measurements. Mar. pollut. Bull. 161, 111766. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111766

Bae S. and Choi K.-H. (2025). Predicting the potential habitat suitability of two invasive ascidian species in Korean waters under present and future climate conditions. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 81, 103967. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2024.103967

Barrett T., Dowle M., Srinivasan A., Gorecki J., Chirico M., Hocking T., et al. (2024). data.table: Extension of “data.frame.”. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.data.table

Bass A., Wernberg T., Thomsen M., and Smale D. (2021). Another decade of marine climate change experiments: trends, progress and knowledge gaps. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.714462

Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., and Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Software 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Bautista N. M. and Crespel A. (2021). Within- and trans-generational environmental adaptation to climate change: perspectives and new challenges. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.729194

Bereza D. and Shenkar N. (2022). Shipping voyage simulation reveals abiotic barriers to marine bioinvasions. Sci. Total Environ. 837. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155741

Biancolini D., Pacifici M., Falaschi M., Bellard C., Blackburn T. M., Ficetola G. F., et al. (2024). Global distribution of alien mammals under climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17560. doi: 10.1111/gcb.17560

Biedrzycka A., Fijarczyk A., Kloch A., and Porth I. M. (2022). Editorial: Genomic basis of adaptations to new environments in expansive and invasive species. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2022.974649

Castro N., Gestoso I., Marques C. S., Ramalhosa P., Monteiro J. G., Costa J. L., et al. (2022). Anthropogenic pressure leads to more introductions: Marine traffic and artificial structures in offshore islands increases non-indigenous species. Mar. pollut. Bull. 181. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2022.113898

Chaikin S., Dubiner S., and Belmaker J. (2022). Cold-water species deepen to escape warm water temperatures. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 31, 75–88. doi: 10.1111/geb.13414

Chapman D., Purse B. V., Roy H. E., and Bullock J. M. (2017). Global trade networks determine the distribution of invasive non-native species. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 26, 907–917. doi: 10.1111/GEB.12599

Chen Y., Gao Y., Huang X., Li S., and Zhan A. (2021). Local environment-driven adaptive evolution in a marine invasive ascidian (Molgula manhattensis). Ecol. Evol. 11, 4252–4266. doi: 10.1002/ece3.7322

Chen Y., Gao Y., Zhang Z., and Zhan A. (2024). Multi-omics inform invasion risks under global climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17588. doi: 10.1111/gcb.17588

Darbyson E. A., Hanson J. M., Locke A., and Willison J. H. M. (2009). Settlement and potential for transport of clubbed tunicate (Styela clava) on boat hulls. Aquat. Invasions 4. doi: 10.3391/ai

Deckmyn O. S. and code by R.A.B. and A.R.W.R. version by R.B.E. by T.P.M. and A (2024). maps: Draw Geographical Maps. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.maps

Dijkstra J., Dutton A., Westerman E., and Harris L. (2008). Heart rate reflects osmostic stress levels in two introduced colonial ascidians Botryllus schlosseri and Botrylloides violaceus. Mar. Biol. 154, 805–811. doi: 10.1007/s00227-008-0973-4

Dyer A. R., Brown C. S., Espeland E. K., McKay J. K., Meimberg H., and Rice K. J. (2010). SYNTHESIS: The role of adaptive trans-generational plasticity in biological invasions of plants. Evol. Appl. 3, 179–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2010.00118.x

Feely R. A., Doney S. C., and Cooley S. R. (2009). Ocean acidification: present conditions and future changes in a high-CO2 world | Oceanography. Oceanography. 22 (4), 37. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2009.95

Gallardo B., Clavero M., Sánchez M. I., and Vilà M. (2016). Global ecological impacts of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 151–163. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13004

Gewing M.-T., Goldstein E., Buba Y., and Shenkar N. (2019). Temperature resilience facilitates invasion success of the solitary ascidian Herdmania momus. Biol. Invasions 21, 349–361. doi: 10.1007/s10530-018-1827-8

Gewing M.-T. and Shenkar N. (2017). Monitoring the magnitude of marine vessel infestation by non-indigenous ascidians in the Mediterranean. Mar. pollut. Bull. 121, 52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.05.041

Goodbody I. (1961). Continuous breeding in three species of tropical ascidian. Proc. Zool. Soc Lond. 136, 403–409. doi: 10.1111/J.1469-7998.1961.TB05882.X

Gröner F., Lenz M., Wahl M., and Jenkins S. R. (2011). Stress resistance in two colonial ascidians from the Irish Sea: The recent invader Didemnum vexillum is more tolerant to low salinity than the cosmopolitan Diplosoma listerianum. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 409, 48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.08.002

Hijmans R. J., Bivand R., Chirico M., Cordano E., Dyba K., Pebesma E., et al. (2025). terra: Spatial Data Analysis. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.terra

IPCC (2023). Summary for Policymakers. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/summary-for-policymakers (Accessed December 11, 2024).

Jofré Madariaga D., Rivadeneira M. M., Tala F., and Thiel M. (2014). Environmental tolerance of the two invasive species Ciona intestinalis and Codium fragile: their invasion potential along a temperate coast. Biol. Invasions 16, 2507–2527. doi: 10.1007/s10530-014-0680-7

Kenworthy J. M., Davoult D., and Lejeusne C. (2018). Compared stress tolerance to short-term exposure in native and invasive tunicates from the NE Atlantic: when the invader performs better. Mar. Biol. 165. doi: 10.1007/s00227-018-3420-1

Kondilatos G., Corsini-Foka M., and Pancucci-Papadopoulou M.-A. (2010). Occurrence of the first non-indigenous ascidian Phallusia nigra Savigny 1816 (Tunicata: Ascidiacea) in Greek waters. Aquat. Invasions 5, 181–184. doi: 10.3391/ai.2010.5.2.08

Lambert G. (2007). Invasive sea squirts: A growing global problem. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 342, 3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2006.10.009. Proceedings of the 1st International Invasive Sea Squirt Conference.

Lee S. S. C., Unger A., Teo S. L. M., and Shenkar N. (2025). Culturing the solitary ascidian Phallusia nigra in closed and open water systems for tropical environmental research. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. doi: 10.1002/lom3.10713

Lenz M., da Gama B. A. P., Gerner N. V., Gobin J., Gröner F., Harry A., et al. (2011). Non-native marine invertebrates are more tolerant towards environmental stress than taxonomically related native species: Results from a globally replicated study. Environ. Res. Invasive Species 111, 943–952. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.05.001

Lüdecke D., Ben-Shachar M. S., Patil I., Waggoner P., and Makowski D. (2021). performance: an R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open Source Software 6, 3139. doi: 10.21105/joss.03139

Meyer A. S., Pigot A. L., Merow C., Kaschner K., Garilao C., Kesner-Reyes K., et al. (2024). Temporal dynamics of climate change exposure and opportunities for global marine biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 15, 5836. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49736-6

Monniot C. and Monniot F. (1997). Records of ascidians from Bahrain, Arabian Gulf with three new species. J. Nat. Hist. 31, 1623–1643. doi: 10.1080/00222939700770871

Nagelkerken I. and Connell S. D. (2022). Ocean acidification drives global reshuffling of ecological communities. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 7038–7048. doi: 10.1111/gcb.16410

Naser H. A. (2017). Variability of marine macrofouling assemblages in a marina and a mariculture centre in Bahrain, Arabian Gulf. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 16, 162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2017.09.005

Occhipinti-Ambrogi A. (2007). Global change and marine communities: Alien species and climate change. Mar. pollut. Bull. 55, 342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2006.11.014

Padilla D. K. and Savedo M. M. (2013). “Chapter Two - A Systematic Review of Phenotypic Plasticity in Marine Invertebrate and Plant Systems,” in Advances in Marine Biology. Ed. Lesser M. (USA, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Academic Press), 67–94. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-410498-3.00002-1

Pierce D. (2024). ncdf4: Interface to Unidata netCDF (Version 4 or Earlier) Format Data Files. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.ncdf4

Pineda M. C. and Turon X. (2012). Stress levels over time in the introduced ascidian Styela plicata: the effects of temperature and salinity variations on hsp70 gene expression. Cell Stress Chaperones 17, 435–444. doi: 10.1007/s12192-012-0321-y

Pinsky M. L., Eikeset A. M., McCauley D. J., Payne J. L., and Sunday J. M. (2019a). Greater vulnerability to warming of marine versus terrestrial ectotherms. Nature 569, 108–111. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1132-4

Pinsky M. L., Selden R. L., and Kitchel Z. J. (2019b). Climate-driven shifts in marine species ranges: scaling from organisms to communities. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 12, 153–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010419

Poloczanska E. S., Burrows M. T., Brown C. J., Molinos J. G., Halpern B. S., Hoegh-Guldberg O., et al. (2016). Responses of marine organisms to climate change across oceans. Front. Mar. Sci. 3. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00062

Prentis P. J., Wilson J. R. U., Dormontt E. E., Richardson D. M., and Lowe A. J. (2008). Adaptive evolution in invasive species. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.03.004

Renborg E., Johannesson K., Havenhand J., Renborg E., Johannesson Á. K., and Havenhand Á. J. (2014). Variable salinity tolerance in ascidian larvae is primarily a plastic response to the parental environment. Ecol. Evol. 28, 561–572. doi: 10.1007/s10682-013-9687-2

Rocha R. M., Castellano G. C., and Freire C. A. (2017). Physiological tolerance as a tool to support invasion risk assessment of tropical ascidians. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 577, 105–119. doi: 10.3354/meps12225

Rocha R. M. D., Lotufo T. M. D. C., and Rodrigues S. D. A. (1999). The biology of Phallusia nigra Savigny, 1816 (Tunicata: Ascidiacea) in southern Brazil: spatial distribution and reproductive cycle. Bull. Mar. Sci. 64 (1), 77–87.

Šargač Z., Giménez L., González-Ortegón E., Harzsch S., Tremblay N., and Torres G. (2022). Quantifying the portfolio of larval responses to salinity and temperature in a coastal-marine invertebrate: a cross population study along the European coast. Mar. Biol. 169, 81. doi: 10.1007/s00227-022-04062-7

Schupfner M., Wieners K.-H., Wachsmann F., Steger C., Bittner M., Jungclaus J., et al. (2019). DKRZ MPI-Es12.2-HR model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp585. doi: 10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.4403

Shenkar N. and Loya Y. (2009). Non-indigenous ascidians (Chordata: Tunicata) along the Mediterranean coast of Israel. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 2. doi: 10.1017/s1755267209990753

Sorte C. J. B., Williams S. L., and Zerebecki R. A. (2010). Ocean warming increases threat of invasive species in a marine fouling community. Ecology 91, 2198–2204. doi: 10.1890/10-0238.1

Soto-Navarro J., Jordá G., Amores A., Cabos W., Somot S., Sevault F., et al. (2020). Evolution of Mediterranean Sea water properties under climate change scenarios in the Med-CORDEX ensemble. Clim. Dyn. 54, 2135–2165. doi: 10.1007/s00382-019-05105-4

Spence A. R. and Tingley M. W. (2020). The challenge of novel abiotic conditions for species undergoing climate-induced range shifts. Ecography 43, 1571–1590. doi: 10.1111/ecog.05170

Spinu V., Grolemund G., Wickham H., Vaughan D., Lyttle I., Costigan I., et al. (2024). lubridate: Make Dealing with Dates a Little Easier. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.lubridate

Therneau T. M. and Lumley T. (2023). Package Survival: A Package for Survival Analysis in R (R Package).

Ulman A., Ferrario J., Occhpinti-Ambrogi A., Arvanitidis C., Bandi A., Bertolino M., et al. (2017). A massive update of non-indigenous species records in Mediterranean marinas. PeerJ 5, e3954. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3954

Utermann C. (2021). Ciona intestinalis in the spotlight of metabolomics and microbiomics: New insights into its invasiveness and the biotechnological potential of its associated microbiota (thesis). Kiel, Germany: Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel.

Vandepas L. E., Oliveira L. M., Lee S. S. C., Hirose E., Rocha R. M., and Swalla B. J. (2015). Biogeography of Phallusia nigra: is it really black and white? Biol. Bull. 228, 52–64. doi: 10.1086/BBLv228n1p52

Wickham H., Chang W., Henry L., Pedersen T. L., Takahashi K., Wilke C., et al. (2024). ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.ggplot2

Wickham H., François R., Henry L., Müller K., Vaughan D., Software P., et al. (2023). dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.dplyr

Wood S. (2023). mgcv: Mixed GAM Computation Vehicle with Automatic Smoothness Estimation. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.mgcv

Zhan A., Briski E., Bock D. G., Ghabooli S., and Macisaac H. J. (2015). Ascidians as models for studying invasion success. Mar. Biol. 162, 2449–2470. doi: 10.1007/s00227-015-2734-5

Keywords: bioinvasions, species distribution, ascidians, environmental tolerance, global change, marine ecosystems, non-indigenous species

Citation: Unger A, Lee SSC, Teo SLM, Levy O and Shenkar N (2025) Climate change resilience in Phallusia nigra: a comparative study of native and introduced populations. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1666759. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1666759

Received: 15 July 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025; Revised: 12 November 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Fabio Crocetta, Anton Dohrn Zoological Station Naples, ItalyReviewed by:

Alfonso Angel Ramos-Esplá, University of Alicante, SpainLuís Felipe Skinner, Rio de Janeiro State University, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Unger, Lee, Teo, Levy and Shenkar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Noa Shenkar, c2hlbmthcm5AdGF1ZXgudGF1LmFjLmls

Amit Unger

Amit Unger Serina Siew Chen Lee

Serina Siew Chen Lee Serena Lay Ming Teo

Serena Lay Ming Teo Ofir Levy

Ofir Levy Noa Shenkar

Noa Shenkar