Abstract

Coral reefs in tropical and subtropical oceans are complex ecosystems characterized by high biodiversity. Zooxanthellate scleractinians are a major component of these reefs. However, the factors influencing coral community establishment and the diversity of coral genera remain poorly understood. A scleractinian-specific environmental DNA metabarcoding (Scl-eDNA-M) method offers a comprehensive and comparative approach to analyzing coral communities across different reef sites. In this study, 10 reef sites in the Republic of Palau, each with distinct geographic features, were monitored using the Scl-eDNA-M system. This system is technically capable of identifying all 69 known scleractinian coral genera in Palau; approximately 60 genera were detected in this study. Acropora, Porites, Montipora, Pocillopora, Goniastrea, and Merulina were the dominant genera, while Leptoria, Platygyra, Pavona, Favites, Isopora, Cyphastrea, and Hydnophora were sub-dominant. The visual census method supported the eDNA metabarcoding results. Clustering analysis based on coral diversity at the genus level indicated that the 10 sites could be grouped into three categories, primarily based on the dominance of Acropora, Porites, Montipora, or Pocillopora. These community profiles were not associated with geographic features such as north versus south or east versus west, but rather with geological features such as lagoons, moats, or reef slopes. In contrast, several genera were identified only at specific geographic locations, including the western outer reefs. Although a larger-scale survey is needed, this study provides an insight into how coral communities in the Palau Islands may have formed in relation to geographic and geological factors.

Introduction

The coral reefs of the Palau Archipelago are among the most pristine and well-developed in the world. The archipelago is located at the westernmost part of the Micronesia region in the Pacific Ocean, approximately 950 miles southeast of the Philippines and 830 miles southwest of Guam. The main islands of Palau extend approximately 35 km in length (Figure 1a). Palau’s coral reefs provide essential goods and ecosystem services to the population of this small island nation (Costanza et al., 2014). However, similar to coral reefs worldwide, both natural and anthropogenic disturbances have degraded reef health, thereby reducing the direct and indirect benefits they offer (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007; Cinner et al., 2009; De’ath et al., 2012; Ainsworth et al., 2016; Cheal et al., 2017). Two major disturbances that affected Palau’s coral reefs over the past two decades were the 1998 mass bleaching event (Bruno et al., 2001; Golbuu et al., 2005, 2007) and two super typhoons that struck the eastern barrier reefs in 2012 and 2013 (Gouezo et al., 2015; Gouezo and Olsudong, 2018). The bleaching event resulted in a 43% loss of live coral cover (Golbuu et al., 2005, 2007), while the typhoons caused a 60% relative reduction in live coral. Despite these disturbances, the reefs have gradually recovered over the past decade.

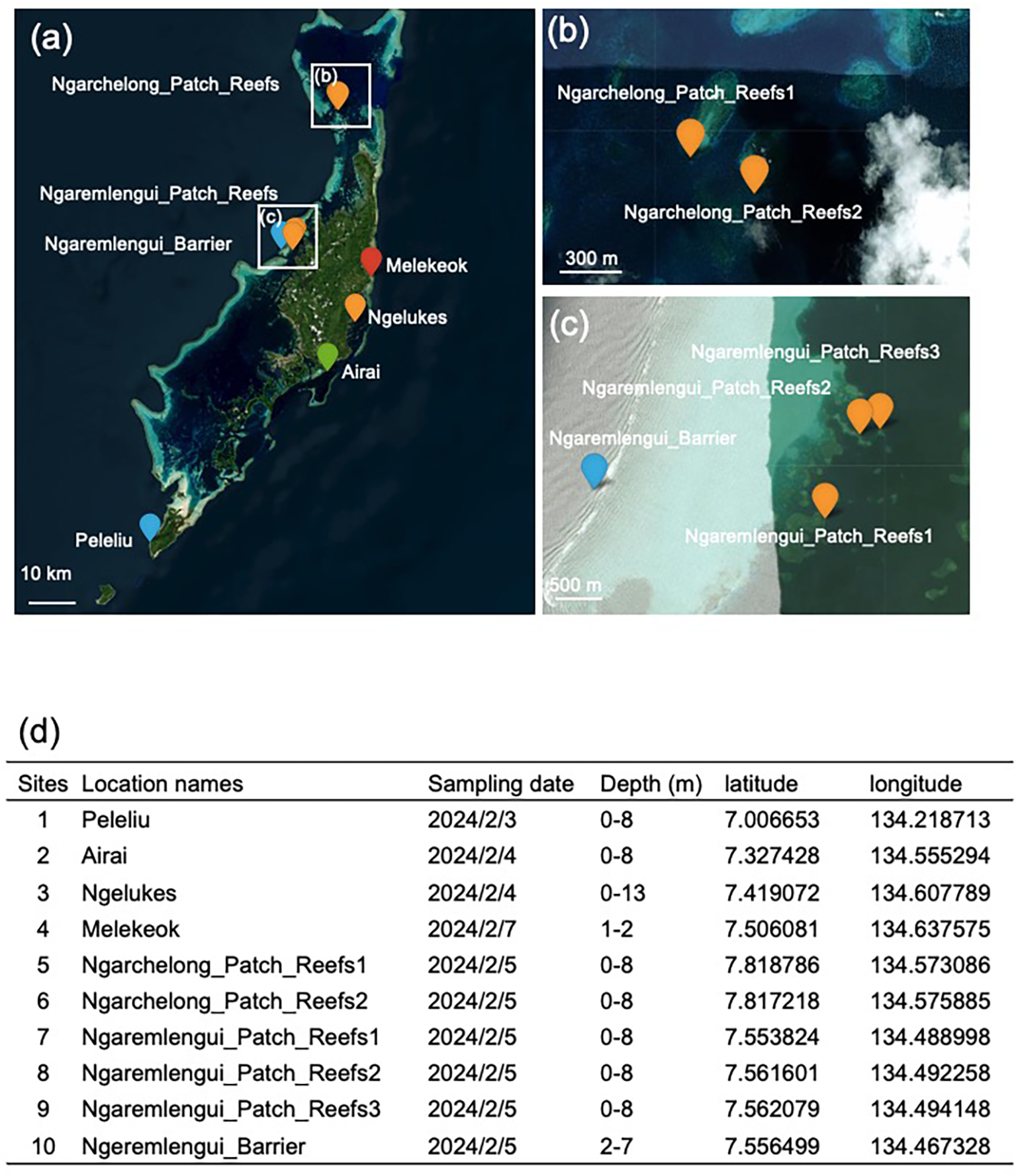

Figure 1

Locations of monitoring sites in the Palau Islands. (a) Zooxanthellate scleractinian coral eDNA survey conducted at 10 monitoring sites in Palau. (b) Enlarged view of the two northwestern sites shown in (a). (c) Enlarged view of the four mid-western sites shown in (a). (d) Details of sampling dates, approximate reef depths (m), and geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) of the sites.

Following the 1998 mass bleaching event, the Palau International Coral Reef Center (PICRC) established ecological monitoring programs in Palau. The coral reef ecological monitoring program was initiated in 2001 with the objective of documenting the status and temporal trends of coral reef communities (Gouezo et al., 2017, 2019a). The program encompasses the main islands of Palau and is stratified by exposure, with sites categorized as western outer reefs, eastern outer reefs, inner reefs, and patch reefs. According to Gouezo et al. (2019), it took 9–12 years for coral reefs to fully recover from the mass bleaching event, with complete recovery observed on the western outer and inner reefs. Patch reefs were the slowest to recover, despite exhibiting early community reassembly dominated by Acropora. In contrast, the eastern outer reefs had not fully recovered from bleaching damage before being impacted by typhoon events.

The major juvenile coral groups examined during monitoring of coral recovery included Acropora spp., Montipora spp., Pocillopora spp., Poritidae spp., and Merulinidae spp (Gouezo et al., 2019). The coral community has been gradually reassembling toward a more diverse composition, resembling the state prior to the typhoon disturbances. Coral diversity increased over time, from 16 genera in 2002 to a peak of 42 genera in 2010 at deeper reefs (10 m depth), prior to the typhoon events. The composition of major juvenile coral groups varied across the four reef types: Acropora spp. and Montipora spp. were dominant on the western and eastern outer reefs, while Poritidae spp. dominated the inner reefs. These spatial differences in coral assemblages offer valuable opportunities to study how coral communities in the Palau Islands have been structured in relation to geographic and geological features.

Environmental DNA metabarcoding (eDNA-M) is a powerful tool for monitoring zooxanthellate scleractinian corals at specific reef sites (Nichols and Marko, 2019; Alexander et al., 2020; DiBattista et al., 2020; Dugal et al., 2021; Shinzato et al., 2021; Nishitsuji et al., 2023; Gösser et al., 2023; Nishitsuji et al., 2024; Satoh et al., 2024). This method relies on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of a specific region of environmental DNA, typically corresponding to a segment of the mitochondrial genome. Accurate assessment of coral genus-level diversity requires a complete or near-complete eDNA-M system. To achieve this, we addressed two critical challenges: the selection of a suitable primer set for PCR amplification, and the availability of sequence information for zooxanthellate scleractinian corals in Japan. Previous coral eDNA-M studies have employed partial sequences of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI), 16S rDNA, and/or internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) for coral eDNA detection (Nichols and Marko, 2019; Alexander et al., 2020; Dugal et al., 2021). On the other hand, in anticipation of the potential to yield more information in the future, we targeted the mitochondrial 12S rDNA gene and developed a primer set capable of amplifying this region across all known scleractinian species (Shinzato et al., 2021). Lengths of amplicons varied from 366 to 471 bp depending on the species, the sequence differences of which were used to identify scleractinian genera.

We also established experimental conditions under which mitochondrial 12S rDNA reference sequences were available for all locally occurring scleractinian genera, thereby enabling comprehensive genus-level analysis. A recent taxonomic classification of zooxanthellate scleractinians in Japan reported the presence of 20 families comprising 85 genera (Online Monograph of Zooxanthellate Corals of Japan; accessed 25 July 2024, at https://coralmonogr.jpn.org/; Nishihira and Veron, 1995). However, a search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nucleotide database revealed that only approximately 60 of these genera had available 12S rDNA sequences, indicating that approximately 25 genera could not be detected by the eDNA-M system due to the absence of reference sequence data. To address this limitation and develop a nearly complete eDNA-M system for genus-level detection of Japanese scleractinians, we collected specimens representing 22 scleractinian genera and sequenced their mitochondrial genomes (Yoshioka et al., 2024; Hisata et al., 2025). In addition, species from 12 other genera were re-sequenced to account for potential sequence variation caused by geographic differences. Incorporating these sequences into a newly constructed informatics pipeline resulted in a Scl-eDNA-M system capable of detecting 83 out of the 85 known genera, with the exception of Boninastrea and Nemenzophyllia (Hisata et al., 2025).

Of the 83 genera, 58 were identifiable as “single genus”, in which given species clearly affiliated with or corresponded to a single genus. The most commonly distributed genera, such as Acropora, Isopora, Pavona, Galaxea, Pachyseris, Porites, Dipsastraea, Favites, and Pocillopora, were included in this category. On the other hand, 2 or 3 of the remaining 25 genera shared identical amplicon sequences and were therefore classified into 12 “grouped” genera. As discussed in detail by Hisata et al. (2025), among the 12 groups, 5 belong to the family Merulinidae, 3 belong to the family Fungiidae, and 4 groups each consist of genera from the families Acroporidae, Agariciidae, Dendrophylliidae, or Lobophylliidae. No group includes genera from more than one family. Members within each group—particularly those in the Fungiidae and Merulinidae—are morphologically similar and inhabit similar environments. Therefore, it is likely that their eDNA co-occurs in the same samples. However, to accurately distinguish among these closely related taxa, future studies should develop eDNA-M systems with primers capable of resolving each genus within these group. An application of the system in survey of coral community at 62 sites along the coast of Okinawa Island, Japan, resulted in eDNA-based detection of at least 54 of the 83 genera (65%) in Okinawa (Hisata et al., 2025).

The aim of this study was to gain insights into how coral communities in Palau are structured in relation to geographic and geological features. To achieve this, we first evaluated whether the Scl-eDNA-M system could detect all known coral genera in Palau. An eDNA-M survey was then conducted to assess coral genus-level diversity at 10 representative reef sites across Palau. A visual census was also performed at the same sites to support and validate the eDNA-M findings. Based on the data obtained using the Scl-eDNA-M system, we investigated the extent to which geographic and geological features influence coral community composition at these sites.

Materials and methods

Sampling sites

Sampling was conducted at 10 coral reef sites in the Republic of Palau on 3, 4, 5, and 7 February 2024 (Figure 1). The names of the sites, sampling dates, geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude), and approximate water depths are summarized in Figure 1d. Site 1 (Peleliu) was selected as the southernmost reef (Figure 1a). Sites 2 (Airai), 3 (Ngelukes), and 4 (Melekeok) were selected as eastern reefs (Figure 1a). Sites 5 (Ngarchelong_Patch_Reefs1) and 6 (Ngarchelong_Patch_Reefs2) were selected as the northernmost reefs (Figures 1a, b). Sites 7 (Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs1), 8 (Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs2), 9 (Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs3), and 10 (Ngeremlengui_Barrier) were selected as western reefs (Figures 1a, c). All sites were shallow reefs (Figure 1d), and photographs of each site were taken by experienced coral taxonomists (Figure 2).

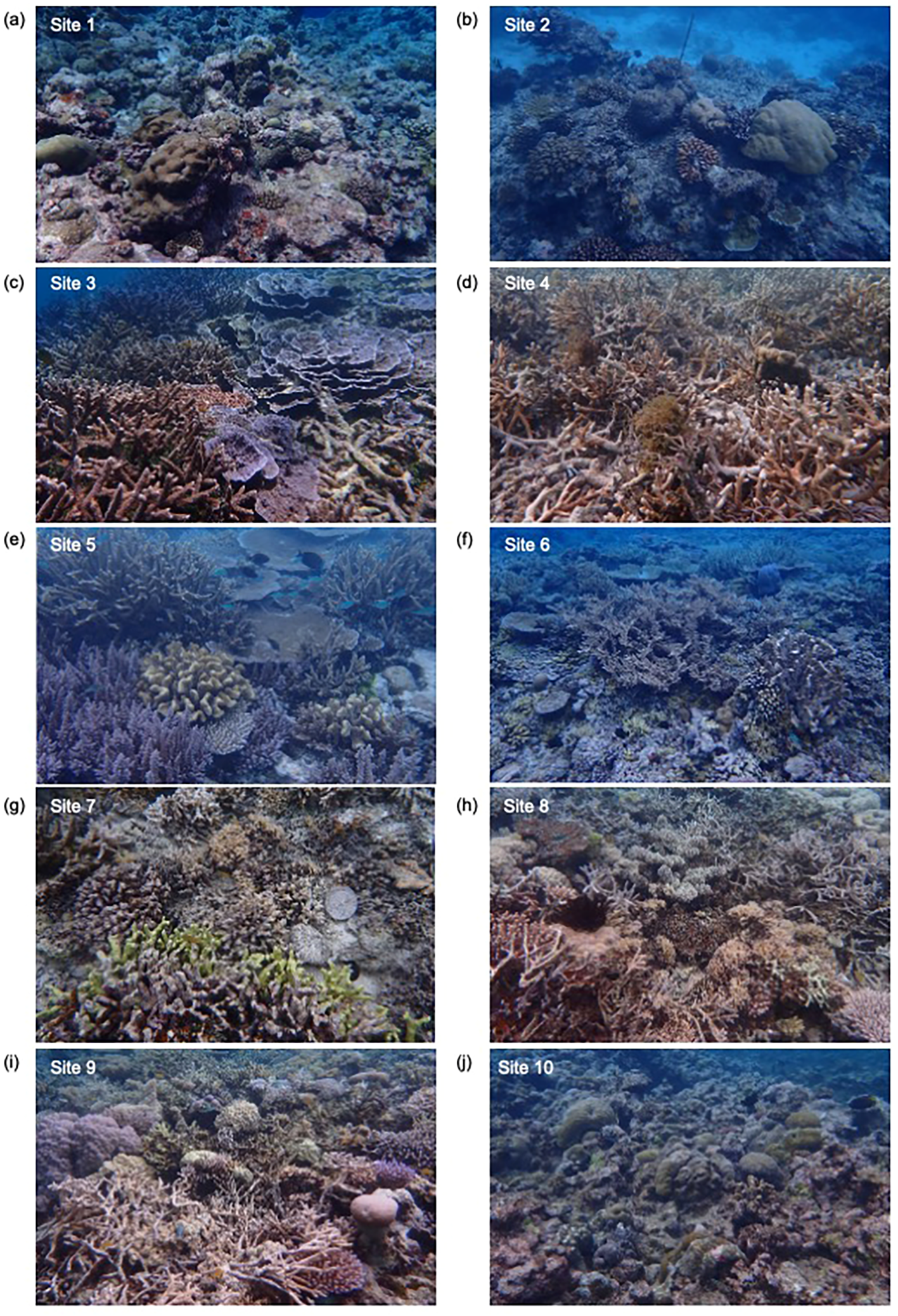

Figure 2

Photographs showing the distribution of various scleractinian corals at 10 monitoring sites in Palau. (a) Site 1: Peleliu; (b) Site 2: Airai; (c) Site 3: Ngelukes; (d) Site 4: Melekeok08; (e) Site 5: Ngarchelong_Patch_Reefs1; (f) Site 6: Ngarchelong_Patch_Reefs2; (g) Site 7: Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs1; (h) Site 8: Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs2; (i) Site 9: Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs3; (j) Site 10: Ngeremlengui_Barrier. Photographs were taken by coral experts during direct observation surveys.

Visual census

Two experienced coral reef specialists snorkeled around reefs and recorded coral community types and dominant coral genera (species), according to a manual in Monitoring Site 1000 Project in which reef monitoring was conducted in Japan by the Ministry of the Environment of Japan (https://www.biodic.go.jp/moni1000/manual/spot-check_ver5.pdf). Types of coral community included ‘specific taxon dominance’ (e.g. ‘Acropora dominance’), ‘specific species’, ‘multi-species mixed’ and ‘not determined’, where the first to third categories were distinguished by dominant taxa and their relative abundances. Monitoring of each site required approximately 20 min with repeated snorkeling. Each diver recorded coral genera based on their taxonomic experience. At the end of sampling day, the divers discussed their observations to reach a consensus regarding major coral genera observed at each site. Coral coverage of individual reefs was beyond the scope of the present study.

Seawater collection, PCR amplification, and sequencing of eDNAs

Duplicate 1-L surface seawater samples were collected for eDNA analysis using disposable plastic bags. Soon after collection, on a boat, each sample was individually filtered through a 0.45-μm Sterivex filter (Merck) using an EYELA rotor machine or 50 mL syringes, a process that took approximately 15 min. To prevent DNA degradation, 2 mL of RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to each filter immediately after filtration. Filters were stored at 4 °C on the boat and later transferred to a −20°C freezer in the laboratory. These procedures minimized the risk of cross-contamination between samples and prevented DNA degradation.

eDNA was extracted from the Sterivex filters following the Environmental DNA Sampling and Experiment Manual, version 2.1 (Minamoto et al., 2021). Each duplicate sample was independently subjected to DNA extraction, PCR amplification, cDNA preparation, sequencing, and metabarcoding analysis. Final results were obtained by averaging the paired samples.

Primers used for the scleractinian-specific eDNA metabarcoding method were Scle_12S_Fw (5′-CCAGCMGACGCGGTRANACTTA-3′) and Scle_12S_Rv (5′-AAWTTGACGACGGCCATGC-3′), designed to amplify an approximately 350-450 bp region of the mitochondrial 12S rDNA gene (Shinzato et al., 2021). These primers completely matched the target region of almost all zooxanthellate scleractinian corals examined to date (Hisata et al., 2025). PCR amplification was performed in a 25-μL reaction containing 2 μL of eluted eDNA, 0.3 U of Tks Gflex DNA Polymerase (Takara), 12.5 μL of 2× Gflex PCR Buffer (Takara), and 0.5 μM of each primer. The PCR protocol consisted of initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min; followed by 35 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 68°C for 30 s; and a final extension at 68°C for 5 min. Control PCR experiments were performed using DNA from Acropora tenuis as a positive control and surface seawater from a coastal site (>30 m depth) and distilled water as negative controls. The positive control produced a visible ~400-bp amplicon, while the negative controls showed no bands (Supplementary Figure S1).

PCR products were purified using the FastGene Gel/PCR ESxtraction Kit (NIPPON Genetics Co., Ltd.). Amplicon sequencing libraries were prepared from the cleaned PCR products using the KAPA HyperPrep Kit (Roche), without fragmentation. Libraries were multiplexed and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform with 300-bp paired-end reads, using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600 cycles). Sequencing data have been deposited in public databases under the following accession numbers: BioProject—PRJDB20358 (PSUB025693), BioSample—SAMD00894721 to SAMD00894740 (SSUB033143), Experiment—DRX660806 to DRX660825 (oist_mgu-0072_Experiment_0001–0020), and Run—DRR680704 to DRR680723 (oist_mgu-0072_Run_0001–0020).

Metabarcoding analysis

The Scl-eDNA-M system was able to identify 83 genera by analyzing eDNA from mitochondrial 12S rDNA (Hisata et al., 2025). Of the aforementioned genera, 58 were identified as “single or independent” genera. On the other hand, 2 or 3 of the remaining 25 genera shared identical amplicon sequences and were therefore classified into 12 grouped genera (Hisata et al., 2025).

Low-quality sequences (using –quality-cutoff=30 and –minimum-length=300) and Illumina sequence adaptors were trimmed using CUTADAPT v4.5 (Martin, 2011). ZOTUs (zero-radius operational taxonomic units) were employed to identify scleractinian genera, with minor modifications to the method described by Shinzato et al. (2021). All ZOTU analyses were conducted on a sample-by-sample basis using USEARCH v11.0.677 (Edgar, 2010). ZOTUs with a BLAST e-value ≤ 1e−20 against mitochondrial sequences of scleractinians were retained for further analysis. The number of mapped sequences for each ZOTU was determined using the USEARCH otutab command with a percent identity of 100% (-id 1.00). Taxonomic assignments were made using a custom database (Hisata et al., 2025) and the Assign-Taxonomy-with-BLAST tool, and the best-estimated genus was selected. Two seawater samples were analyzed, and in most cases, they yielded similar ZOTU counts (Supplementary Table S1). These counts were evaluated by taking the average. The detection threshold for genera was set at 0.01% of ZOTU counts in each surveyed reef to avoid false positives, given that Scl-eDNA-M is one of the most accurate systems for detecting scleractinians.

Hierarchical and non-hierarchical clustering analyses were performed using scleractinian ZOTU counts in R v4.3.2 to clarify the similarity of scleractinian coral communities among the survey sites. The pheatmap package (v2.12.1) was employed for hierarchical clustering using the Ward.D method. To further examine compositional similarity among coral taxa at different sites, we conducted non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) using the vegdist and metaMDS functions from the vegan R package. In this analysis, data sizes were normalized to the smallest ZOTU count across all survey sites using the rarefy function. Clustered sites were visualized with color and symbol annotations.

Results

Efficiency of the Scl-eDNA-M system

As mentioned above, the Scl-eDNA-M system is capable of identifying 83 zooxanthellate scleractinian genera reported from Japan. Randall (1995) documented 63 coral genera in Palauan waters based on collected specimens (Supplementary Table S2), whereas Maragos et al. (1994) estimated Palau’s coral diversity at 425 species across 78 genera. We initially assessed the applicability and efficiency of the Scl-eDNA-M system for identifying Palauan scleractinians using Randall’s dataset (1995). Advances in coral taxonomy since the publication of Randall’s report have resulted in changes to species and genus names, as well as the establishment of new genera; thus, several taxa have been reassigned to updated taxonomic categories. We re-examined the 63 genera reported by Randall using the most recent taxonomic classification (World Register of Marine Species website, accessed July 2025; Costello et al., 2013), which resulted in a revised total of 68 zooxanthellate scleractinian genera currently recognized in the Palau Islands (Supplementary Table S2). We then compared the 68 genera reported from Palau with the 83 genera identified in Japan using the Scl-eDNA-M system and confirmed that all 68 Palauan genera were included among the 83 Japanese genera (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2). In other words, 15 genera detected in Japan have not been reported in Palau by Randall (1995). These include Gyrosmilia (Euphylliidae), Bernardpora (Poritidae), Pseudosiderastrea (Rhizangiidae), Heterocyathus (Caryophylliidae), Heteropsammia (Dendrophylliidae), Halomitra and Zoopilus (Fungiidae), Cynarina and Echinomorpha (Lobophylliidae), Catalaphyllia, Oulastrea, Paramontastraea, Physophyllia, and Trachyphyllia (Merulinidae), and Blastomussa (Plerogyridae) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2).

We also consulted the more recent NOAA Field Guide to the Corals of Palau (2020) (https://www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/palau_coral_field_id/field_guide_corals_palau_2020.pdf). Compared with Randall (1995), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) guide includes 39 additional zooxanthellate scleractinian species and one additional genus, Paramontastraea. Since the reference database of the Scl-eDNA-M already contains Paramontastraea, the system is applicable for distribution survey of the genus, and Paramontastraea was detected in Palau (Table 1, 2). Therefore, we concluded that the Scl-eDNA-M system is capable of identifying all 69 scleractinian genera present in Palau.

eDNA metabarcoding analysis

Palau genera detected by Scl-eDNA-M system

The presence and absence of scleractinian genera across 10 reef sites in Palau are shown in Table 1. In addition, to provide data directly for readers to assess independently, ZOTU counts for 83 genera are presented in Supplementary Table S1. A total of 1,900,226 ZOTUs corresponding to amplicon sequences of scleractinian mitochondrial 12S rDNA were obtained (Supplementary Table S1). The highest ZOTU count (360,691) was recorded at Site 1 (Peleliu), while the lowest (75,190) was observed at Site 8 (Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs2). The average across all 10 sites was 190,227. When compared with ZOTU counts from other reef systems reported previously (Nishitsuji et al., 2023; Noda et al., 2025; Hisata et al., 2025), the values obtained in this study were comparable and sufficient for subsequent metabarcoding analyses. However, the reasons for the lower ZOTU counts observed at Sites 3 and 8 remained unclear.

Under the detection threshold of 0.01% of all ZOTU counts at given survey sites, 18 genera of the 69 Palauan genera identifiable by this system were not identified. They were Alveopora, Astreopora, Euphyllia, Gyrosmilia, Bernardpora, Pseudosiderastrea, Stylocoeniella, Heterocyathus, Cycloseris, Heliofungia, Cynarina, Homophyllia, Micromussa, Astraeosmilia, Paragoniastrea, Blastomussa, Plerogyra, and Madracis (Table 1). In contrast, the remaining 51 genera were detected with distinct ZOTU counts, indicating a high richness of zooxanthellate scleractinian corals in the Palau Islands (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Based on ZOTU counts, the most dominant genera were Acropora, Porites, Pocillopora, Montipora+Anacropora, and Goniastrea+Merulina (Supplementary Table S1). These were followed by Leptoria+Platygyra, Pavona, Favites, Isopora, Cyphastrea, and Hydnophora (Supplementary Table S1). The top five single and grouped genera were also commonly detected by the Scl-eDNA-M system along the coasts of the Okinawa Archipelago, Japan (Nishitsuji et al., 2023; Noda et al., 2025; Hisata et al., 2025). In addition, Pavona, Favites, and Isopora were likewise identified in Japan (Nishitsuji et al., 2023; Hisata et al., 2025). These findings suggest that an overall profile of common genera is shared between Okinawa and Palau, despite their geographic separation of approximately 2,200 km across the Pacific Ocean.

In addition to the global and local distributions described above, site-specific and characteristic features were also identified. First, the family Astrocoeniidae is considered important for understanding the early evolution of the suborder Vacatina (Yoshioka et al., 2025). Palauastrea (also known as Palau coral), a member of this family, was detected exclusively at Site 9 (Table 1; Supplementary Table S1), although the site was predominantly occupied by Acropora and Porites (Table 1; Supplementary Table S1). Similarly, the restricted detection of Plesiastrea at Site 3 and Stylaraea at Site 1 was also observed (Table 1; Supplementary Table S1). Second, Coeloseris (family Euphylliidae) was detected with a considerable ZOTU count only at Sites 2, 3, and 4—eastern outer reefs facing the Pacific Ocean (Supplementary Table S1; Figure 1). These sites correspond to lagoon (Sites 2 and 3) and moat (Site 4) environments. Site 2 was dominated by Pocillopora, Site 3 was dominated by Acropora, and Site 4 was dominated by Porites (Table 1; Supplementary Table S1).

Third, Acropora and Montipora are two genera within the family Acroporidae and are among the most common corals in the western Pacific, including Japan and Palau. This study showed notable differences among Sites 1, 4, and 5. Site 1, in particular, showed a high abundance of Montipora (ZOTU count: 208,997) and a low abundance of Acropora (ZOTU count: 2,606). In contrast, Sites 4 and 5 showed a high abundance of Acropora (ZOTU counts: 194,837 and 182,201, respectively) and a low abundance of Montipora (ZOTU counts: 2,689 and 3,420).

New genera records for Palau suggested by the Scl-eDNA-M system

This study detected the eDNA-based presence of 51 genera in Palau (i.e., 69 minus 18; Table 1). On the other hand, 14 genera (i.e., 83 minus 69) not previously recorded in Palau (Randall, 1995) are possibly identifiable using the eDNA-M system (Table 1). These genera included Heteropsammia, Gyrosmilia, Bernardpora, Pseudosiderastrea, Heterocyathus, Halomitra, Zoopilus, Cynarina, Echinomorpha, Catalaphyllia, Physophyllia, Trachyphyllia, Oulastrea, and Blastomussa (Table 1). Our analysis indicated that five of these genera—Gyrosmilia, Bernardpora, Heterocyathus, Cynarina, and Blastomussa—showed no detectable ZOTU counts (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S1). The 8 to remaining 9 genera (except for Pseudosiderastrea) exhibited distinct ZOTU counts (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S1), with particularly high counts observed for Heteropsammia at Site 5 (1,016), Halomitra at Site 9 (3,418), and Trachyphyllia at Site 3 (892). These findings suggest that future in situ observations should focus on confirming the presence of these 8 genera, particularly the 3 with comparatively high ZOTU counts. The potential to detect previously unrecorded genera highlights one of the key advantages of the Scl-eDNA-M system, which enables the identification of a near-complete assemblage of target scleractinian taxa. The coral community analysis conducted here therefore suggests the presence of these 8 genera in Palau.

Table 1

| Suborder | Family | Genus | Previous report in Palau | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | Site 6 | Site 7 | Site 8 | Site 9 | Site 10 | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peleliu | Airai | Ngelukes | Melekeok | Ngarchelong_Patch_Reefs1 | Ngarchelong_Patch_Reefs2 | Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs 1 | Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs 2 | Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs 3 | Ngeremlengui_Barrier | |||||

| Refertina | Acroporidae | Acropora | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Alveopora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Astreopora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Isopora | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Montipora/Anacropora | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||

| Agariciidae | Gardineroseris/Leptoseris/Pavona | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| Pavona | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||

| Dendrophylliidae | Dendrophyllia/Duncanopsammia/Tubastraea | 1*** | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Heteropsammia* | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Turbinaria | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Euphylliidae | Coeloseris | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Euphyllia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Fimbriaphyllia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Galaxea | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Gyrosmilia** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pachyseridae | Pachyseris | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Poritidae | Bernardpora** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Goniopora | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | ||

| Porites | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| Stylaraea | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Rhizangiidae | Pseudosiderastrea** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vacatina | Astrocoeniidae | Palauastrea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Stylocoeniella | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Caryophylliidae | Heterocyathus** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Coscinaraeidae | Coscinaraea | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |

| Diploastraeidae | Diploastrea | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Fungiidae | Ctenactis/Polyphyllia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Cycloseris | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Danafungia/Lithophyllon | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Fungia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Halomitra* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Heliofungia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Herpolitha/Podabacia/Sandalolitha | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Lobactis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Pleuractis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Sinuorota | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Zoopilus* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Leptastreidae | Leptastrea | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| Lobophylliidae | Acanthastrea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Cynarina** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Echinomorpha* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Echinophyllia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Homophyllia/Micromussa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Lobophyllia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Oxypora | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Merulinidae | Astraeosmilia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Astrea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Catalaphyllia* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Caulastraea/Oulophyllia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Coelastrea/Dipsastraea | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Cyphastrea | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Dipsastraea | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Echinopora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Favites | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Goniastrea/Merulina | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||

| Hydnophora | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Leptoria/Platygyra | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Mycedium/Pectinia/Physophyllia | 1**** | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Paragoniastrea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Paramontastraea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Trachyphyllia* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Oulastreidae | Oulastrea* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Plerogyridae | Blastomussa** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Physogyra | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Plerogyra | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Plesiastreidae | Plesiastrea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Pocilloporidae | Madracis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pocillopora | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| Seriatopora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Stylophora | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Psammocoridae | Psammocora | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| total | 69 | 23 | 20 | 19 | 28 | 24 | 30 | 15 | 9 | 26 | 30 |

Detected genera by eDNA in this study along Palau coast.

* These groups were not reported prevously but detected in this study.

** These groups were not reported previously and not detected in this study.

*** Dendrophyllia and Tubastraea are azooxanthellae groups, but share identical 12S rDNA amplicon sequsnces to Duncanopsammia.

**** Mycedium and Pectinia were reported, but Physophyllia was not in Palau previously."1" means detection or previous report and "0" means no detection or no previous reports except for the "total" column and raw in this table.

Table 2

| Suborder | Family | Genus | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | Site 6 | Site 7 | Site8 | Site 9 | Site 10 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refertina | Dendrophylliidae | Heteropsammia | 335 | 16 | 2 | 28 | 1016 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 30 | 15 | 1460 |

| Euphylliidae | Gyrosmilia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Poritidae | Bernardpora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rhizangiidae | Pseudosiderastrea | 7 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 24 | |

| Vacatina | Caryophylliidae | Heterocyathus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fungiidae | Halomitra | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 155 | 161 | 0 | 0 | 3418 | 0 | 3750 | |

| Zoopilus | 0 | 0 | 124 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 126 | ||

| Lobophylliidae | Cynarina | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Echinomorpha | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63 | ||

| Merulinidae | Catalaphyllia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 74 | 81 | |

| Mycedium/Pectinia/Physophyllia* | 0 | 0 | 129 | 370 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 154 | 0 | 2 | 655 | ||

| Trachyphyllia | 0 | 0 | 892 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 255 | 1149 | ||

| Oulastreidae | Oulastrea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 109 | 109 | |

| Plerogyridae | Blastomussa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

ZOTU counts of scleractinian genera that have not been reported from Palau.

* Mycedium and Pectinia were reported but Physophylliia was not in Palau previously.

Bold numbers and taxa mean that they are above our detection threshold.

Visual census

In this study, during surface seawater sampling conducted from a boat, direct observations of dominant scleractinian genera were performed by two experienced coral taxonomists (Figure 2). At Site 1 (Peleliu, southernmost reef slope), dominant genera identified through direct observation were Pocillopora, Acropora, Porites, Montipora, and Goniastrea (Table 3; Figure 2a). At Site 2 (Airai, eastern lagoon), the dominant genera were Pocillopora, Acropora, Porites, and Stylophora (Table 3; Figure 2b). At Site 3 (Ngelukes Entry, eastern lagoon), the dominant genera included Acropora, Montipora, Porites, Pocillopora, Seriatopora, Goniastrea, and Heliopora (Table 3; Figure 2c). At Site 4 (Melekeok08, eastern moat), Acropora, Porites, Isopora, Pocillopora, Stylophora, and Montipora were dominant (Table 3; Figure 2d). At Site 5 (Ngarchelong Patch-Reefs1 Entry region, northernmost lagoon), the dominant genera were Acropora, Pocillopora, Millepora, and Stylophora (Table 3; Figure 2e). At Site 6 (Ngarchelong Patch-Reefs2 Entry region, northernmost lagoon), Acropora was the most dominant, followed by Stylophora, Seriatopora, Goniastrea, and Platygyra (Table 3; Figure 2f). At Site 7 (Ngaremlengui Patch Reefs1, western reef lagoon), the dominant genera were Porites, Acropora, Seriatopora, Fungiidae, and Echinopora (Table 3; Figure 2g). At Site 8 (Ngaremlengui Patch Reefs2, western reef lagoon), Acropora, Porites, Seriatopora, Pocillopora, Echinopora, and Fungiidae were dominant (Table 3; Figure 2h). At Site 9 (Ngaremlengui Patch Reefs3, western reef moat), the dominant genera included Acropora, Porites, Seriatopora, and Fungiidae (Table 3; Figure 2i). At Site 10 (Ngeremlengui Barrier, western reef slope), direct observation revealed Goniastrea, Porites, Pocillopora, Acropora, Stylophora, Diploastrea, and Platygyra as the dominant genera (Table 3; Figure 2j).

An overall comparison of visual census data among the 10 sites indicated similarities in generic composition between Sites 1 and 2, Sites 4 and 5, and Sites 8 and 9 (Table 3; Figure 2).

Table 3

| Monitoring Sites | Scleractinian ZOTU count | coral community | Dominat corals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | specific species | Pocillopora | Acropora | Porites | Montipora | Goniastrea | |||

| (Peleliu) | 360,691 | 13 (0.521 %) | 11 (0.723 %) | 3 (12.5 %) | 1 (57.9 %) | 2 (16.2 %) | |||

| Site 2 | specific species | Pocillopora | Acropora | Porites | Stylopora | ||||

| (Airai) | 213,198 | 1 (29.7 %) | 3 (19.9%) | 2 (19.9%) | 9 (1.48 %) | ||||

| Site 3 | specific species | Acropora | Montipora | Porites | Pocillopora | Seriatopora | Goniastrea | Heliopora | |

| (Ngelukes) | 77,677 | 1 (72.5 %) | 2 (5.70 %) | 5 (4.18 %) | 9 (0.969 %) | 19 (0.0283 %) | 13 (0.478 %) | Not Scleractinia | |

| Site 4 | specific species | Acropora | Porites | Isopora | Pocillopora | Stylophora | Montipora | ||

| (Melekeok08) | 228,474 | 3 (11.1 %) | 1 (51.3%) | 4 (6.73 %) | 2 (17.8 %) | 14 (0.267 %) | 5 (3.79 %) | ||

| Site 5 | Acropora | Acropora | Pocillopora | Millepora | Stylophora | ||||

| (Ngarchelong_Patch_Reefs1) | 214,730 | 1 (90.7%) | 2 (2.31%) | Not Scleractinia | 12 (0.179%) | ||||

| Site 6 | Acropora | Acropora | Stylophora | Seriatopora | Goniastrea | Platygyra | |||

| (Ngarchelong_Patch_Reefs2) | 249,194 | 1 (73.1 %) | 7 (0.729 %) | 14 (0.239 %) | 3 (7.02 %) | 8 ( 0.698 %) | |||

| Site 7 | multi-species mixed | Porites | Acropora | Seriatopora | Fungiidae | Echinopora | |||

| (Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs3) | 139,417 | 1 (46.6 %) | 3 (22.3 %) | 14 (0.0445 %) | not genus (0.440 %) | 11 (0.0839 %) | |||

| Site 8 | Acropora | Acropora | Porites | Seriatopora | Pocillopora | Echinopora | Fungiidae | ||

| (Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs2) | 75,019 | 1 (83.2 %) | 2 (11.5 %) | no eDNA | 3 (1.70 %) | no eDNA | not genus (0.432 %) | ||

| Site 9 | specific species | Acropora | Porites | Seriatopora | Fungiidae | ||||

| (Ngaremlengui_Patch_Reefs1) | 162,715 | 1 (35.8%) | 2 (29.5%) | 23 (0.0903%) | not genus (3.89 %) | ||||

| Site 10 | specific species | Goniastrea | Porites | Pocillopora | Acropora | Stylophora | Diploastrea | Platygyra | |

| (Ngeremlengui_Barrier) | 179,111 | 1 (21.5 %) | 6 (6.44 %) | 7 (3.93%) | 5 (10.1%) | 25 (0.0642 %) | 23 (0.116 %) | 4 (11.3 %) |

Comparsion of prominent coral genera by divers' direct observation with eDNA metabarcoding data.

The numbers outside parentheses indicate the ranking of ZOTU counts, and the numbers in parentheses are the percentage of ZOTU counts at given sites. Numbers 1 to 5 are in bold.

Support of eDNA data by visual census method

We evaluated whether data obtained through the eDNA-M method were supported by visual census observations. At Site 1 (Peleliu), the visual census identified Pocillopora, Acropora, Porites, Montipora, and Goniastrea as the dominant genera (Table 3; Figure 2a). Correspondingly, genera with high ZOTU counts in the eDNA-M analysis included Montipora, Goniastrea, and Porites (Supplementary Table S1). These results show a fair level of agreement between the two methods (Table 3). At Site 2 (Airai), visual observation indicated local dominance of Pocillopora, Acropora, and Porites (Table 3; Figure 2b), which was consistent with the eDNA-M results that also showed high ZOTU counts for Pocillopora, Acropora, and Porites (Supplementary Table S1; Table 3). Similarly, direct observation at Site 3 (Ngelukes Entry) identified Acropora, Montipora, Porites, and Pocillopora as the dominant genera (Table 3; Figure 2c). The two highest ZOTU counts were recorded for Acropora and Montipora (Supplementary Table S1), again indicating strong consistency between visual census and eDNA-M results (Table 3).

At Site 4 (Melekeok), direct observation recorded the local dominance of Acropora, Porites, Isopora, Pocillopora, and Montipora (Table 3; Figure 2d). Genera with high ZOTU counts included Porites, Pocillopora, Acropora, Isopora, and Montipora (Supplementary Table S1), indicating a strong match between the two methods (Table 3). At Site 5 (Ngarchelong Patch-Reefs1 Entry region), Acropora and Pocillopora were identified as the dominant genera by direct observation (Table 3; Figure 2e). The eDNA-M analysis also showed high ZOTU counts for Acropora and Pocillopora (Supplementary Table S1), confirming a good agreement between the two methods (Table 3). At Site 6 (Ngarchelong Patch-Reefs2 Entry region), direct observation recorded Acropora as the most dominant genus, followed by Stylophora, Seriatopora, and Goniastrea (Table 3; Figure 2f). Genera with high ZOTU counts included Acropora, followed by Montipora and Goniastrea (Supplementary Table S1).

Direct observation characterized Site 7 (Ngaremlengui Patch Reefs1) by the dominance of Porites and Acropora (Table 3; Figure 2g). The eDNA-M analysis also revealed high ZOTU counts for Porites and Acropora (Supplementary Table S1). At Site 8 (Ngaremlengui Patch Reefs2), direct observation reported the local dominance of Acropora, Porites, and Pocillopora (Table 3; Figure 2h). Similarly, Acropora, Porites, and Pocillopora were the three genera with the highest ZOTU counts (Supplementary Table S1), showing that the results from both methods were well matched. At Site 9 (Ngaremlengui Patch Reefs3), Acropora and Porites were also dominant according to visual census (Table 3; Figure 2i). The same genera had the highest ZOTU counts in the eDNA-M analysis (Supplementary Table S1). At Site 10 (Ngeremlengui Barrier), direct observation identified Goniastrea, Porites, Pocillopora, and Acropora as the dominant genera (Table 3; Figure 2j). The eDNA-M results showed high ZOTU counts for Goniastrea, Porites, Pocillopora, and Acropora (Supplementary Table S1), indicating general agreement between the methods, though with partial differences in dominant taxa.

Local community profiles of scleractinians along Palau reefs

The analysis of local distribution profiles of scleractinian corals was conducted using data obtained by eDNA-M system, which was supported by the results of direct observations.

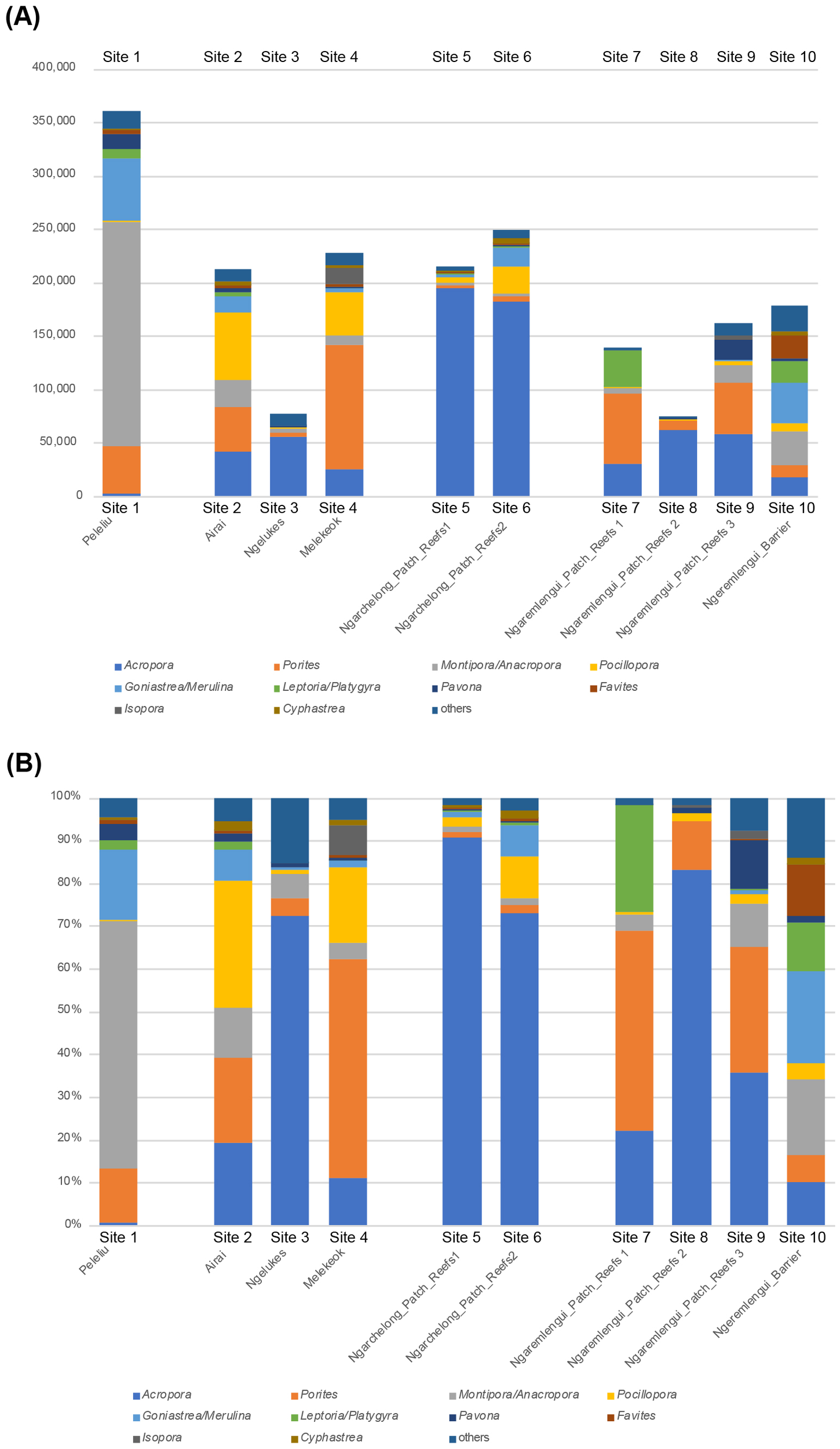

Bar graph comparison of the community

Figure 3 presents a bar graph comparing scleractinian coral communities across the 10 survey sites, based on the relative dominance of 10 genera: Acropora, Porites, Montipora, Pocillopora, Goniastrea+Merulina, Leptoria+Platygyra, Pavona, Favites, Isopora, and Cyphastrea. The profiles were broadly categorized into three groups. The first group included Sites 3, 5, 6, and 8, where Acropora was highly dominant, followed by Porites, Montipora, and Pocillopora in lower proportions. The second group consisted of Sites 2, 4, 7, and 9, where Porites was dominant followed by Pocillopora at Sites 2 and 4, and Acropora at Sites 7 and 9. Site 1 was characterized by the dominance of Montipora, followed by Goniastrea+Merulina. This pattern closely resembled that of Site 10; thus, Sites 1 and 10 likely constituted the third group (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Bar graphs showing the composition of scleractinian genera with the top 11 highest ZOTU counts at 10 monitoring sites in the Palau Islands. (A) Results based on raw ZOTU counts; the Y-axis indicates the ZOTU counts. (B) Results based on the percentage of ZOTU counts.

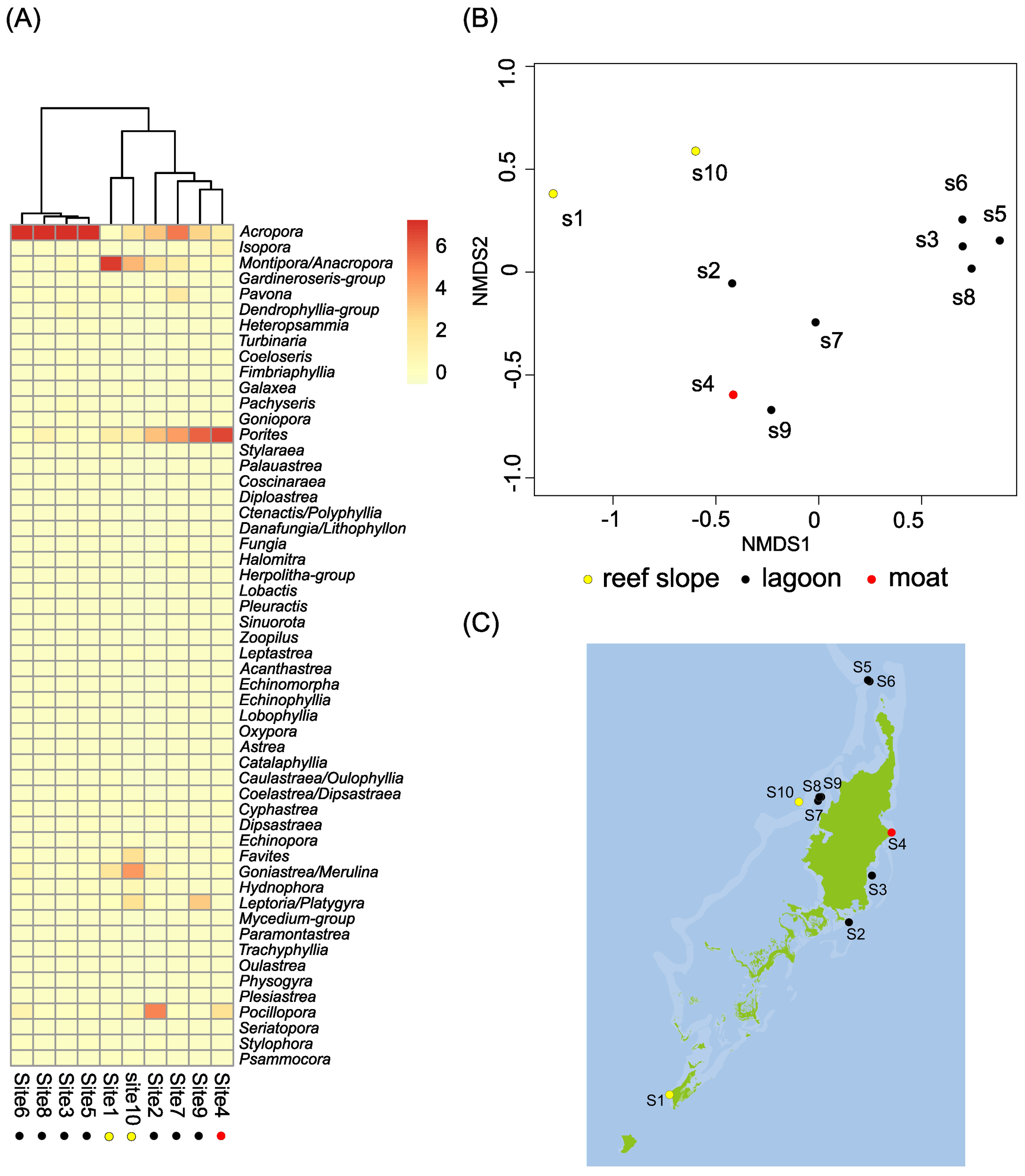

Heatmap analysis

Heatmap analysis was conducted using total sum scale (TSS)-normalized read abundance of ZOTU counts for each taxon (Figure 4A, rows) across merged sample replicates (Figure 4A, columns). This analysis initially grouped the 10 sites into two major clusters: one comprising Sites 3, 5, 6, and 8, and the other consisting of Sites 1, 2, 4, 7, 9, and 10. The latter was further subdivided into a subgroup containing Sites 1 and 10, and another with Sites 2, 4, 7, and 9 (Figure 4A). The first major cluster was characterized by a high relative abundance of Acropora, with lower representation of other genera. In contrast, the second major cluster generally exhibited lower proportions of Acropora and higher proportions of Montipora, Porites, Goniastrea+Merulina, and Pocillopora. Within this second group, the Site 1 and Site 10 subgroup showed particularly high levels of Montipora, along with Goniastrea+Merulina and Porites. These patterns were consistent with those observed in the bar graph analysis.

Figure 4

Classification of scleractinian coral communities across 10 monitoring sites in the Palau Islands based on eDNA data. (A) Hierarchical clustering of scleractinian coral communities at the survey sites. (B) NMDS plot showing community classifications. (C) Map of coral community types at the 10 sites; dot colors correspond to the NMDS-based classification in (B).

Non-metric multidimensional scaling ordination analysis

Analysis of the NMDS revealed the following clustering patterns (Figure 4B). A distinct cluster consisted of Sites 3, 5, 6, and 8, corresponding to the first major group identified in the heatmap analysis. Weaker clustering was also observed between Sites 1 and 10, and between Sites 4 and 9 (Figure 4B). The former group was characterized by the dominance of Montipora, and the latter by the dominance of Porites. When these results were considered alongside two factors—geological and geographical features—it appeared that the pattern of coral distribution was more closely correlated with geology (e.g., reef slopes, lagoons, and moats) than with geography (e.g., south vs. north, east vs. west) (Figure 4C). Specifically, Sites 3, 5, 6, and 8 were located in lagoons, whereas Sites 1 and 10 were situated on reef slopes (Figure 4C). This geological association was supported by similarities in coral composition observed in photographs: Sites 3 (Figure 2c), 5 (Figure 2e), 6 (Figure 2f), and 8 (Figure 2h) exhibited comparable coral assemblages. Likewise, the coral composition in Site 1 (Figure 2a) resembled that of Site 10 (Figure 2j).

Discussion

The Scl-eDNA-M system in coral community research

eDNA-M has emerged as a powerful approach for comprehensive monitoring of scleractinian corals (Shinzato et al., 2018; Nichols and Marko, 2019; Alexander et al., 2020; DiBattista et al., 2020; Dugal et al., 2021; Shinzato et al., 2021; Gösser et al., 2023; Nishitsuji et al., 2023; Hoban et al., 2023; Ip et al., 2023; Nishitsuji et al., 2024). Compared with its application to other marine taxa, such as fish (e.g., Açıkbaş et al., 2024), Scl-eDNA-M offers several advantages. First, because most corals are sessile and firmly attached to substrates, reef communities provide stable targets for repeated monitoring. This also enables direct validation of Scl-eDNA-M results against visual census surveys (Gösser et al., 2023; Nishitsuji et al., 2023; Satoh et al., 2024; this study). Second, corals continuously release mucus and cellular debris containing DNA. This material is buoyant and tends to remain near the sea surface, allowing scleractinian-specific eDNA to be efficiently captured by filtering surface seawater over shallow reefs.

Despite these advantages, the application of Scl-eDNA-M and the interpretation of its results require careful consideration of several issues (e.g., van der Loos and Niland, 2021). The first involves seawater sampling, including potential contamination among samples from the same site or between sites, as well as eDNA degradation during procedures. In this study, seawater was collected using disposable bags, filtered rapidly, and preserved with RNAlater immediately after filtration to minimize these risks. The second issue concerns primer design and the completeness of mitochondrial genome data for local scleractinian corals. This challenge is being addressed through the development of the Scl-eDNA-M system, which targets the 12S rDNA region and currently covers sequence data for 83 of the 85 genera recorded in Japan. Extending this system beyond Japan to diverse coral reef regions worldwide will be crucial for advancing molecular and ecological insights into coral reef formation across the Pacific Ocean.

This study applied the Scl-eDNA-M system to coral reefs in Palau and found that the system is capable of identifying 69 scleractinian genera previously documented in the region. Of the 69 genera, 51 confirmed their eDNA-based presence. In addition, eDNA analysis indicated the potential presence of 8 to 9 genera not previously recorded in Palau. Among these, Heteropsammia, Halomitra, and Trachyphyllia were particularly strong candidates, with probable sites of occurrence also identified (Table 2). These findings enhance understanding of the taxonomic composition of Palau’s coral reefs and highlight the utility of this approach for detecting previously unrecognized diversity.

The most problematic issue in the eDNA-M method is the quantitative assessment of coral diversity using the Scl-eDNA-M method, such as comparisons of the relative proportions of coral genera between multiple sites based on ZOTU counts, which required further refinement. This was due to several underlying assumptions inherent in the technical procedures. The first question is whether the number of coral colonies is quantitatively correlated with the amount of eDNAs obtained from surface seawater or eDNA counts obtained by the metabarcoding system. This has been examined and confirmed in aquarium experiments in which multiple Acropora species were reared in tanks containing different numbers of colonies (Shinzato et al., 2018). The next question is whether the number of colonies from different coral genera is quantitatively correlated with the amount of eDNA or ZOTU count obtained from surface seawater. This was tested in another aquarium experiment in which 37 coral genera were reared at varying colony numbers (Narisoko et al., 2025). The results indicated that Acropora tended to yield slightly higher ZOTU counts per colony than other genera, whereas Fungia tended to yield slightly lower values. However, these differences were not sufficient to significantly influence the results of comparative analyses. Therefore, we thought that comparisons of coral genus proportions at reef sites based on ZOTU counts appear to be more reliable than might initially be assumed. This is supported by the general concordance between eDNA-M results and visual surveys in both the present study of Palau reefs and previous surveys in Okinawa reefs (Nishitsuji et al., 2023; Hisata et al., 2025). Nevertheless, eDNA abundance and the corresponding ZOTU values are affected by physical and biological conditions, underscoring the need for further methodological refinement.

Factors influencing coral community establishment

Among reef organisms, zooxanthellate corals, most of which belong to the order Scleractinia, class Anthozoa, play the most critical role in the construction of coral reef ecosystems. These corals form complex ecosystems characterized by immense diversity at the species, genus, and family levels. However, the processes shaping coral community composition in relation to the geographic and geological features of reefs remain poorly understood. The aim of this study was to challenge this question.

Given the methodological constraints and limitations in interpreting the results discussed above, the present study may still offer valuable insights into how coral communities have been shaped by environmental, geographic, or geological factors. An overall classification of the 10 sites based on eDNA-M-derived scleractinian genera diversity clearly demonstrated three major groupings: one consisting of Sites 3, 5, 6, and 8; a second composed of Sites 2, 4, 7, and 9; and a third made up of Sites 1 and 10 (Figure 4). This classification was supported by bar graph comparison, heatmap analysis, and NMDS analysis. The results of the visual census method also supported this inclination (Table 3). The first group was characterized by the dominance of Acropora and other associated genera, the second was characterized by the dominance of Porites, and the third was characterized by the dominance of Montipora (Figure 4A). When these results were examined in relation to two potential explanatory factors—geography and geology—it appeared highly likely that coral distribution patterns were more strongly associated with geologic features (e.g., reef slopes, lagoons, and moats) than with geographic location (e.g., north vs. south or east vs. west). Thus, the present study might provide evidence supporting the notion that coral genera diversity in Palau is primarily structured by geological, rather than geographic, factors.

On the other hand, we also identified cases in which coral community composition appeared to be associated with geographic features. Coeloseris (family Euphylliidae) was detected with a considerable ZOTU counts only at Sites 2, 3, and 4—corresponding to the eastern outer reefs of Palau facing the Pacific Ocean (Table 2; Figure 1). Sites 2 and 3 were lagoonal reefs, while Site 4 was a moat reef. These sites were characterized by the dominance of Pocillopora (Figure 2b), Acropora (Figure 2c), and Porites (Figure 2d), respectively. The specific localization of Coeloseris on the eastern outer reef thus appeared to be linked to regional or geographic factors, as pointed out by Gouezo et al. (2019).

This research also sheds light on one clue regarding coral distribution related to seawater temperature. Acropora and Montipora are two genera within the family Acroporidae and represent the most common corals in the western Pacific, including Japan, Taiwan, and Palau. The distribution of these genera has sometimes been discussed in relation to seawater temperature variation within reefs. Specifically, Montipora tends to be more abundant in warmer waters, whereas Acropora prefers cooler regions (Jokiel and Brown, 2004). The present eDNA-M analysis indicated notable differences between Sites 1, 4, and 5: Site 1 showed high abundance of Montipora and low abundance of Acropora, while Sites 4 and 5 showed the opposite pattern, with abundant Acropora and less Montipora. Although the high abundance of Montipora at Site 1 was not always supported by direct observation (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1; Figure 2a), this pattern was consistent with the previously reported temperature-based distribution of the two genera.

In conclusion, although broader-scale monitoring is necessary, the present study provides important insights into the coral community structure of Palau reefs in relation to geographic or geologic factors.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

TaN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. HN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – review & editing. MK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. EO: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. GR: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YG: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KH: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. ToN: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. NS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported in part by the JST COI-NEXT program (Grant No. JPMJPF220405) and the OIST Coral Project.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Palau International Coral Reef Center for their generous hospitality. The Sequencing Section and the Scientific Computing and Data Analysis Section at OIST are acknowledged for conducting genome sequencing and for computing resources.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1669587/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Ainsworth T. D. Heron S. F. Ortiz J. C. Mumby P. J. Grech A. Ogawa D. et al . (2016). Climate change disables coral bleaching protection on the Great Barrier Reef. Science352, 338–342. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7125

2

Alexander J. B. Bunce M. White N. Wilkinson S. P. Adam A. A. Berry T. et al . (2020). Development of a multi-assay approach for monitoring coral diversity using eDNA metabarcoding. Coral Reefs39, 159–171. doi: 10.1007/s00338-019-01875-9

3

Bruno J. Siddon C. Witman J. Colin P. Toscano M. (2001). El Niño related coral bleaching in Palau, western Caroline Islands. Coral Reefs20, 127–136. doi: 10.1007/s003380100151

4

Cheal A. J. MacNeil M. A. Emslie M. J. Sweatman H. (2017). The threat to coral reefs from more intense cyclones under climate change. Global Change Biol.23, 1511–1524. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13593

5

Cinner J. E. McClanahan T. R. Daw T. M. Graham N. A. J. Maina J. Wilson S. K. et al . (2009). Linking social and ecological systems to sustain coral reef fisheries. Curr. Biol.19, 206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.055

6

Costanza R. de Groot R. Sutton P. van der Ploeg S. Anderson S. J. Kubiszewski I. et al . (2014). Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environ. Change26, 152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.002

7

Costello M. J Bouchet P. Boxshall G. Fauchald K. Gordon D. Hoeksema B. W et al . (2013). Global coordination and standardisation in marine biodiversity through the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) and related databases. PloS one8, e51629.

8

De’ath G. Fabricius K. E. Sweatman H. Puotinen M. (2012). The 27-year decline of coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef and its causes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.109, 17995–17999.

9

DiBattista J. D. Reimer J. D. Stat M. et al . (2020). Environmental DNA can act as a biodiversity barometer of anthropogenic pressures in coastal ecosystems. Sci. Rep.10, 8365. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64858-9

10

Dugal L. Thomas L. Wilkinson S. P. Richards Z. T. Alexander J. B. Adam A. A. S. et al . (2021). Coral monitoring in northwest Australia with environmental DNA metabarcoding using a curated reference database for optimized detection. Environ. DNA3, 1–14. doi: 10.1002/edn3.199

11

Edgar R. C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics26, 2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461

12

Gösser F. Schweinsberg M. Mittelbach P. Schoenig E. Tollrian R. (2023). An environmental DNA metabarcoding approach versus a visual survey for reefs of Koh Phangan in Thailand. Environ. DNA5, 297–311. doi: 10.1002/edn3.378

13

Golbuu Y. Bauman A. Kuartei J. Victor S. (2005). “ The state of coral reef ecosystems of Palau,” in The State of Coral Reef Ecosystems of the United States and Pacific Freely Associated States, 2005. Silver Spring, MD, 488–507.

14

Golbuu Y. Fabricius K. Okaji K. (2007). “ Status of Palau’s coral reefs in 2005, and their recovery from the 1998 bleaching event,” in Coral Reefs of Palau, Palau, 40–50.

15

Gouezo M. Golbuu Y. van Woesik R. Rehm L. Koshiba S. Doropoulos C. (2015). Impact of two sequential super typhoons on coral reef communities in Palau. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.540, 73–85. doi: 10.3354/meps11518

16

Gouezo M. Nestor V. Olsudong D. Marino L. Mereb G. Jonathan R. (2017). 15 years of coral reef monitoring demonstrates the resilience of Palau’s coral reefs, PICRC Technical Report 18-08. Palau, International Coral Reef Center. Palau.

17

Gouezo M. Nestor V. Otto E. I. Marino L. Olsudong D. Mereb G. et al . (2019). Palau’s coral reefs are generally in good condition apart from reefs still recovering from typhoon damages, PICRC Technical Report 20-09. Palau, International Coral Reef Center. Palau.

18

Gouezo M. Olsudong D. (2018). Impacts of Tropical Storm Lan (October 2017) on the western outer reefs of Palau, PICRC Technical Report 18-08.

19

Hisata K. Nagata T. Kanai M. Sinniger F. Nagata F. Suwa M. et al . (2025). An eDNA metabarcoding system for detecting scleractinian corals to the generic level along the Japanese coast. Galaxea27, 13–29. doi: 10.3755/galaxea.G27D-5

20

Hoban M. L. Bunce M. Bowen B. W. (2023). Plumbing the depths with environmental DNA (eDNA): metabarcoding reveals biodiversity zonation at 45–60 m on mesophotic coral reefs. Mol. Ecol.32, 5590–5608. doi: 10.1111/mec.17140

21

Hoegh-Guldberg O. Mumby P. J. Hooten A. J. Steneck R. S. Greenfield P. Gomez E. et al . (2007). Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science318, 1737–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.1152509

22

Ip Y. C. A. Chang J. J. M. Tun K. P. P. Meier R. Huang D. (2023). Multispecies environmental DNA metabarcoding sheds light on annual coral spawning events. Mol. Ecol.32, 6474–6488. doi: 10.1111/mec.16621

23

Jokiel P. L. Brown E. K. (2004). Global warming, regional trends and inshore environmental conditions influence coral bleaching in Hawaii. Glob Change Biol.10, 1627–1641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00836.x

24

Maragos A. et al . (1994). “ Marine and coastal areas survey of the main Palau Islands. Part 2,” in Rapid Ecological Assessment Synthesis Report of Palau, Ministry of Resources and Development.

25

Martin M. (2011). Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J.17, 10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200

26

Minamoto T. Miya M. Sado T. Seino S. Doi H. Kondoh M. et al . (2021). An illustrated manual for environmental DNA research: water sampling guidelines and experimental protocols. Environ. DNA3, 8–13. doi: 10.1002/edn3.121

27

Narisoko H. Nagata F. Hisata K. Fujie M. Yoshioka Y. Nonaka M. et al . (2026). Efficiency of scleractinian-specific eDNA metabarcoding using specimens from Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium, Japan. Zool. Sci. in press.

28

Nichols P. K. Marko P. B. (2019). Rapid assessment of coral cover from environmental DNA in Hawai’i. Environ. DNA1, 40–53. doi: 10.1002/edn3.8

29

Nishihira M. Veron J. E. N. (1995). Hermatypic corals of Japan (Tokyo: Kaiyusha), 439.

30

Nishitsuji K. Nagahama S. Narisoko H. Shimada K. Okada N. Shimizu Y. et al . (2024). Possible monitoring of mesophotic scleractinian corals using an underwater mini-ROV to sample coral eDNA. Roy Soc. Open Sci.11, 221586. doi: 10.1098/rsos.221586

31

Nishitsuji K. Nagata T. Narisoko H. Kanai M. Hisata K. Shinzato C. et al . (2023). An environmental DNA metabarcoding survey reveals extensive generic-level occurrence of scleractinian corals at recovering coral reefs near Okinawa Island. Proc. R Soc. B290, 20230026. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2023.0026

32

Açıkbaş A. H. O. Narisoko H. Huelimann R. Nishitsuji K. Satoh N. Reimer J. D. et al . (2024). Fish and coral assemblages of a highly isolated oceanic island: The first eDNA survey of the Ogasawara Islands. Environ. DNA6, e509. doi: 10.1002/edn3.509

33

Randall R. H. (1995). Biogeography of reef-building corals in the Mariana and Palau Islands in relation to back-arc rifting and the formation of the eastern Philippine Sea. Nat Hist Res3(2):193–210.

34

Satoh N. Sinniger F. Narisoko H. Nagahama S. Okada N. Shimizu Y. et al . (2024). Using underwater mini-ROV for coral eDNA survey: a case study in Okinawan mesophotic ecosystems ( Coral Reefs). doi: 10.1007/s00338-024-02597-3

35

Shinzato C. Narisoko H. Nishitsuji K. Nagata T. Satoh N. Inoue J. (2021). Novel mitochondrial DNA markers for Scleractinian corals and generic-level environmental DNA metabarcoding. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.758207

36

Noda T. Higa M. Hisata K. Narisoko H. Suwa M. Koseki A. et al . (2025). eDNA metabarcoding reveals high generic-level scleractinian diversity in the Kerama Islands, Okinawa, Japan. Coral Reefs44, 1065–1078. doi: 10.1007/s00338-025-02669-y

37

Shinzato C. Zayasu Y. Kanda S. Kawamitsu M. Satoh N. Yamashita H. et al . (2018). Using seawater to document coral-zoothanthella diversity: a new approach to coral reef monitoring using environmental DNA. Front. Mar. Sci.5. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00028

38

van der Loos L. M. Niland R. (2021). Biases in bulk: DNA metabarcoding of marine communities and the methodology involved. Mol. Ecol.30, 3270–3288. doi: 10.1111/mec.15592

39

Yoshioka Y. Kanai K. Tsuhako T. Satoh N. Nagata T. (2025). Complete mitochondrial genomes of Palauastrea ramosa Yabe & Sugiyama 1941 and Stylocoeniella guentheri (Bassett-Smith 1890) reveal their molecular phylogenetic position. Galaxea27, 7–12. doi: 10.3755/galaxea.G27-4

40

Yoshioka Y. Nagata F. Nonaka M. Satoh N. (2024). Molecular phylogenetic position of the family Fungiidae (Cnidaria: Anthozoa) based on complete mitochondrial genome sequences. Galaxea26, 43–47. doi: 10.3755/galaxea.G26N-7

Summary

Keywords

Palau coral reefs, scleractinian coral diversity, coral reef community structure, geological and geographic drivers, eDNA metabarcoding

Citation

Noda T, Narisoko H, Kanai M, Otto EI, Rengiil G, Golbuu Y, Hisata K, Nagata T and Satoh N (2026) Environmental DNA metabarcoding reveals geologic, not geographic, drivers of coral community structure in Palau. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1669587. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1669587

Received

20 July 2025

Revised

09 November 2025

Accepted

10 November 2025

Published

21 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Charles Alan Jacoby, University of South Florida St. Petersburg, United States

Reviewed by

Jeff Eble, Florida Institute of Technology, United States

Chih-Wei Chang, National Academy of Marine Research (NAMR), Taiwan

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Noda, Narisoko, Kanai, Otto, Rengiil, Golbuu, Hisata, Nagata and Satoh.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Noriyuki Satoh, norisky@oist.jp

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.