Abstract

Microplastic (MP) pollution has become a critical concern for coral reef ecosystems, yet its presence and impact on zoanthids remain poorly understood. This study provides the first detailed assessment of microplastic accumulation in the zoanthid Palythoa caesia, a common benthic organism in coral reef environments. Samples were collected from three distinct reef sites in Thailand: Chan Island in the upper Gulf of Thailand, Kong Sai Daeng Island in the western Gulf, and Ao Jak of Mu Ko Surin, the Andaman Sea. A total of 624 MP particles were extracted from 38 P. caesia colonies, with MPs detected in every sample. The average abundance was 4.11 ± 1.38 particles·cm-² or 2.37 ± 1.13 particles·g-¹ wet weight, with Chan Island showing significantly higher concentrations than the other sites. This spatial variability appears to reflect differences in local pollution sources, particularly from tourism and coastal activity. MPs were present in both the surface and inner tissue layers, with 61% found on the surface. This suggests that mucus secretion may play a key role in trapping particles from the surrounding water. Fibers were the most common morphology (>80%), and black and blue particles dominated the color spectrum. FT-IR analysis identified polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE) as the most abundant polymers, while Chan Island exhibited higher proportions of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polystyrene (PS), likely linked to single-use plastic waste. The presence of MPs within the inner tissue layers indicates active uptake by the polyps, likely due to their suspension-feeding behavior and the capacity of their coenenchyme to trap sediments. These findings highlight P. caesia as a promising bioindicator for microplastic contamination in reef ecosystems. Addressing this issue will require localized management strategies, including strengthened waste controls in tourist areas, improved regulation of recreational activities in protected zones, and long-term biomonitoring. Integrating microplastic mitigation into marine spatial planning will be essential for preserving coral reef resilience in the face of growing anthropogenic pressures.

Introduction

Coral reefs are the most biodiverse marine ecosystems, providing invaluable ecological services such as coastal protection, fisheries production, and carbon sequestration (Yeemin et al., 2024; Yuan et al., 2024). However, these vital ecosystems are experiencing unprecedented degradation driven by the synergistic effects of climate change and anthropogenic pollution (Nurdjaman et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024). Climate change poses multifaceted threats through rising sea surface temperatures (SSTs), ocean acidification (OA), and the increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events. Elevated SSTs disrupt the coral-zooxanthellae symbiosis, triggering widespread bleaching and potentially causing large-scale mortality if thermal stress persists (Hughes et al., 2019; Neely et al., 2024; Yuan et al., 2024). Concurrently, OA driven by rising atmospheric CO2 reduces seawater pH and aragonite saturation state, impairing coral calcification and compromising reef structural integrity (Cornwall et al., 2021). These stressors are further compounded by increasingly frequent marine heatwaves, which allow insufficient recovery time between bleaching events (Doney et al, 2020; Jiang et al., 2022). Alongside these climate-driven impacts, a suite of anthropogenic pollutants has emerged as critical drivers of coral reef decline. While rising sea surface temperature (SST) remains a primary driver of coral reef decline, increasing evidence also highlights that anthropogenic pollution, particularly nutrient enrichment from agricultural and urban runoff, plays a critical role in reef degradation (Lapointe et al., 2019; Stuart et al., 2025). The ingestion of MPs by coral polyps leads to detrimental effects, including impaired growth and increased susceptibility to bleaching, which is critical for coral survival (Biswas et al., 2024; Prakash, 2024). Additionally, microplastics can have synergistic effects of thermal stress, leading to coral bleaching and increased cellular stress markers (Isa et al., 2024). Overall, while microplastics alone may not pose a significant threat, their interaction with other environmental stressors can severely compromise coral health and resilience.

Plastic pollution, meanwhile, has garnered increasing concern as a pervasive and complex environmental stressor. Microplastics (MPs), defined as synthetic polymer particles ranging from 1 µm to 5 mm in size (Hartmann et al., 2019; Frias and Nash, 2019), have proliferated across marine environments, becoming one of the most pressing environmental challenges of the 21st century. Since their initial scientific documentation in the 1970s (Carpenter et al., 1972), MPs have accumulated in global surface waters at alarming rates, with estimates suggesting between 15 and 51 trillion particles afloat (Isobe et al., 2021). Their ubiquity results from multiple pathways, including direct release from personal care products (Cheung and Fok, 2017; Bashir et al., 2021; Nunes et al., 2023), fragmentation of larger debris through environmental weathering (Andrady, 2017; Delorme et al., 2025), and even atmospheric transport to remote marine habitats (Rindelaub et al., 2025). The ecological consequences of microplastic contamination manifest across multiple biological scales, compounding the vulnerabilities already imposed by climate change. At the organismal level, microplastics (MPs) can induce multiple adverse effects in anthozoans, particularly within the subclass Hexacorallia. Previous studies have demonstrated that MPs adhere to coral mucus layers and are actively ingested by polyps, leading to physical blockage, reduced feeding efficiency, and decreased energy allocation (Browne et al., 2008; Wegner et al., 2012; Reichert et al., 2018; Huffman Ringwood, 2021). Chronic exposure has also been associated with oxidative stress, tissue necrosis, and disruption of symbiotic zooxanthellae, thereby compromising coral health and resilience (Okubo et al., 2018; Rotjan et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2021; Stuart et al., 2025). These individual effects scale up to population- and community-level impacts, including trophic transfer through marine food webs (Jovanović, 2017; Setälä et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2024; Khan and Rountos, 2025), shifts in benthic community composition (Wright et al., 2021), and particularly severe consequences for coral reefs (Yeemin et al., 2018). Building on these findings, microplastic contamination has also emerged as a significant threat to marine invertebrates more broadly, with growing evidence of ingestion and associated physiological effects documented across diverse taxa, including cnidarians (Porter et al., 2023; Hatzonikolakis et al., 2024).

Zoanthids (order Zoantharia), a group of colonial anthozoans closely related to corals and sea anemones, represent a crucial component of benthic ecosystems. As sessile organisms inhabiting the benthic habitats, they are particularly vulnerable to microplastic exposure owing to their suspension-feeding behavior and their close association with contaminated sediments. The ingestion mechanisms in zoanthids involve both autotrophic photosynthesis via symbiotic Symbiodiniaceae and heterotrophic feeding on suspended particulate matter and plankton, a nutritional strategy known as mixotrophy (Muscatine and Porter, 1977; Houlbrèque and Ferrier-Pagès, 2009). Symbiotic zooxanthellae within their tissues contribute significantly to their carbon requirements through photosynthetic carbon fixation, with species like Zoanthus sociatus and Palythoa variabilis variabilis relying on these algae for up to 48.2% and 13.1% of their respiratory needs, respectively (Steen and Muscatine, 1984). Additionally, zoanthids engage in heterotrophic feeding, consuming small detrital particles and zooplankton, with variations in dietary preferences observed between species (Steen and Muscatine, 1984). Furthermore, some zoanthids, such as Palythoa caribaeorum, exhibit a remarkable ability to reproduce asexually through fission and fragmentation. This biological trait is relevant to the present study because asexual reproduction enhances colony expansion and tissue connectivity, facilitating the entrapment and internal retention of microplastic particles within Palythoa caesia colonies examined in our experiment. Laboratory experiments demonstrate that zoanthids can absorb polyvinyl chloride MPs, leading to detrimental effects such as increased DNA damage and altered enzyme activities, which are critical for their health and survival (Albertoni et al., 2024), potentially interfering with nutrient absorption and symbiont function. Zoanthids, like many marine organisms, have been shown to accumulate and retain MPs, with studies indicating that these particles can persist within their systems for extended periods. Research on Zoanthus sp. has demonstrated that exposure to polyvinyl chloride MPs results in significant biochemical responses, suggesting that these organisms can absorb and retain MPs over time (Albertoni et al., 2024. This aligns with findings in other cnidarians, such as the zoanthid Zoanthus sp. and the sea anemone Bunodosoma cangicum, where exposure to microplastics resulted in biochemical and physiological alterations, indicating their capacity for microplastic uptake and retention within tissues (Morais et al., 2020; Albertoni et al., 2024). The persistence of MPs in marine organisms is further supported by studies on zooplankton, which have shown ingestion and retention of MPs that can lead to trophic transfer within aquatic food webs (Cole et al., 2013; McHale and Sheehan, 2024). Although such transfer has not yet been demonstrated in anthozoans, several studies provide evidence of MP uptake and internal incorporation in anthozoans, such as Anemonia viridis (Savage et al., 2022) and anthozoan polyps where microplastics invaded internal tissues (Okubo et al., 2020), suggesting potential pathways for bioavailability to higher trophic levels. Additionally, Palythoa is consumed by a range of marine species, including nudibranchs, starfish, and specific gastropods, (Sonia Kumari et al., 2019; Obuchi and Reimer, 2011; Martin et al., 2014), illustrating the possibility of trophic transfer of microplastics through its food web.

Despite growing recognition of microplastic pollution as a global threat to marine ecosystems, studies specifically examining microplastic ingestion and its physiological impacts on zoanthids remain remarkably scarce in the scientific literature. This critical knowledge gap is particularly concerning given zoanthids’ ecological importance as benthic habitat formers and their potential role as bioindicators of microplastic pollution in coral reef systems. To address these pressing knowledge gaps, this study aims to: (1) quantify microplastic ingestion rates in zoanthid species across different reef habitats in Thailand, and (2) characterize the polymer composition and size distribution of ingested MPs using advanced spectroscopic techniques. Our findings provide crucial baseline data for understanding cnidarian vulnerability to microplastic pollution and inform conservation strategies for benthic marine invertebrates in an era of global environmental change.

Materials and methods

Study sites and samples collection

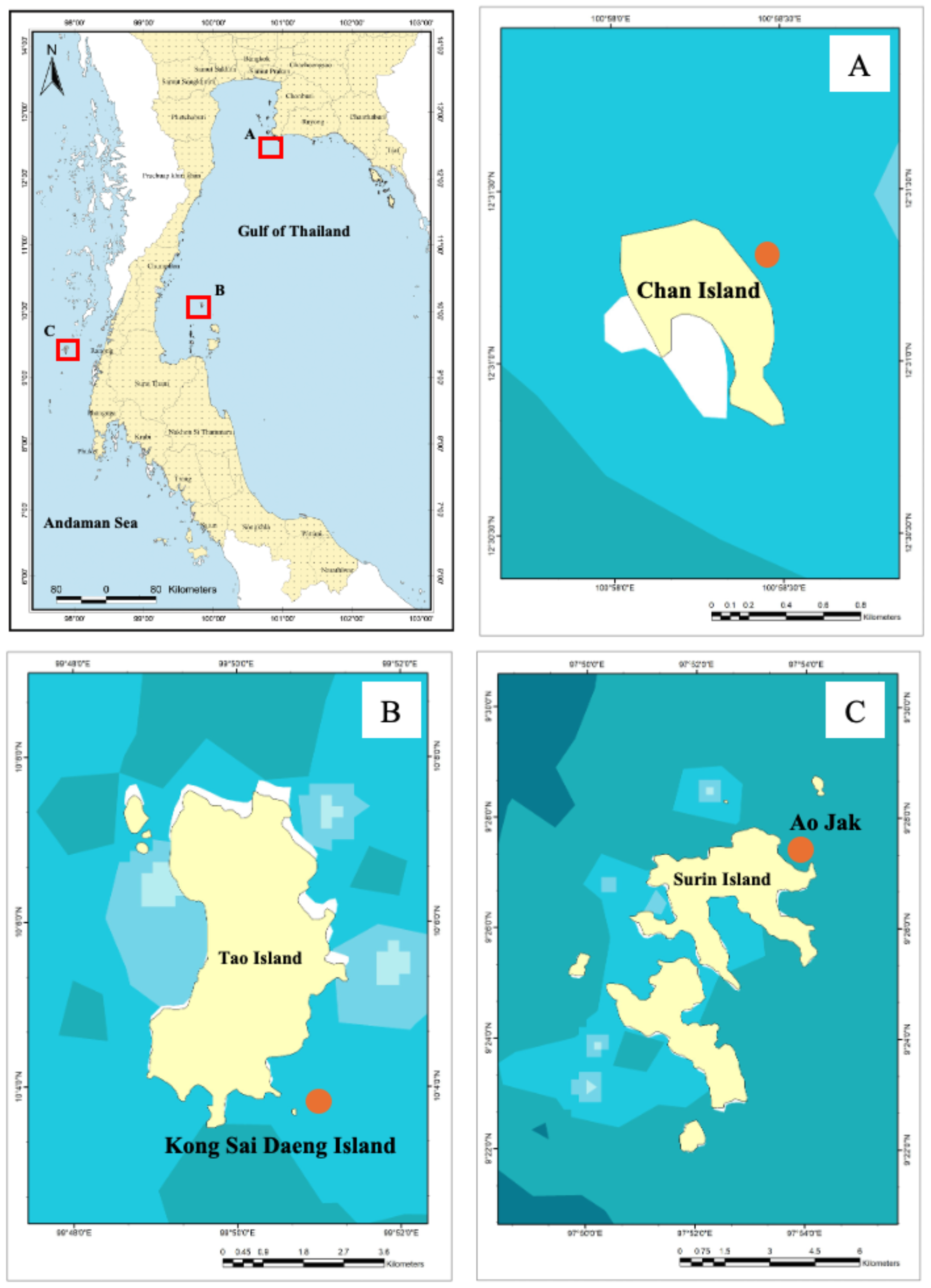

Three representative coral reef areas were designated as sampling sites. The first site, Chan Island, is located in the southern part of Samae San Island in the upper Gulf of Thailand, Chonburi Province, approximately 8 km from the shore. This area supports agriculture and coastal aquaculture and functions as a significant industrial hub, situated near the Eastern Seaboard industrial estates within the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC). The second site, Kong Sai Daeng Island, is located in the southern part of Tao Island in the western Gulf of Thailand, Surat Thani Province, approximately 70 km offshore. It is a well-known tourism destination, particularly for scuba diving and marine recreation, and also supports local fisheries and small-scale aquaculture. The third site, Ao Jak, is situated within Mu Ko Surin National Park in the Andaman Sea, Phang Nga Province, approximately 60 km offshore. This site is recognized for its exceptional coral biodiversity and serves as a critical habitat for numerous reef-associated species. It is also regarded as one of Thailand’s premier locations for snorkeling and diving (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1

| Study sites | Ko Chan | Ko Kong Sai Daeng | Ao Jak |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude (N), Longitude (E) | 12°31.279’N, 100°58.424’E | 10°3.733’N, 99°50.704’E | 9°27.216’N, 97°53.877’E |

| Distance from Shore (km) | 8 | 70 | 60 |

| Distance from main point sources (km) | 122 | 110 | 170 |

| Water Transparency | Turbid | Clear | Clear |

| Depth (m) | 3-5 | 5-13 | 2-14 |

| Anthropogenic Disturbance | Snorkeling and trampling; plastic waste; boat noise; turbidity from vessel movement; nutrient input; pier construction; potential introduction of invasive species | Over-tourism; plastic and wastewater pollution; sediment runoff | Snorkeling-induced coral damage; marine debris from tour boats; wastewater discharge; sediment resuspension |

Location and information of the study sites.

Figure 1

Location of the study sites: (A) Chan Island, (B) Kong Sai Daeng Islands, and (C) Ao Jak, Mu Ko Surin National Park.

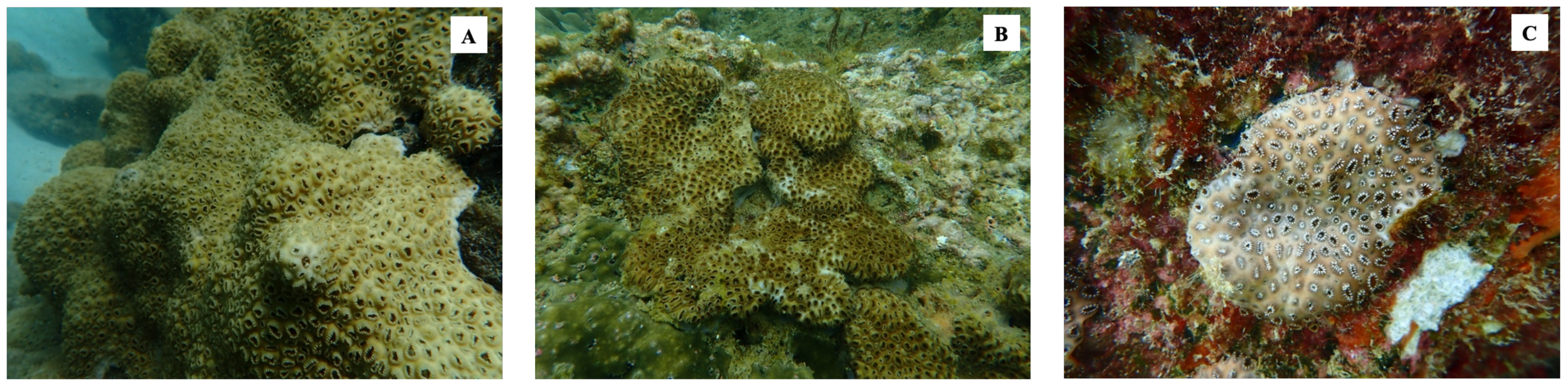

Samples of Palythoa caesia were collected from coral reefs at the similar depth range across the study sites, approximately 2–7 meters during the wet season of 2024, in October for Chan Island and Ao Jak, and in February for Kong Sai Daeng Island. Although the sampling depth at Chan Island was slightly shallower than at the other two sites, all depths were within the typical habitat range of P. caesia. Prior to sampling, each colony was photographed to document its morphological condition, coloration, and surrounding substrate. (Figure 2). In total, 38 colonies of P. caesia were sampled from Chan Island (15 samples), Kong Sai Daeng Island (14 samples), and Ao Jak (9 samples), with three tissue pieces (including inner and outer tissues) collected from each colony to ensure representative coverage of the entire colony surface for microplastic analysis. Tissue samples measuring approximately 5 × 5 cm were then carefully excised from P. caesia colonies using a diving knife. Following collection, each sample were individually wrapped in aluminum foil and then sealed in a zip-lock bag before being transferred to the laboratory. The collected zoanthid samples were immediately frozen and stored at -20 °C before microplastic analysis.

Figure 2

Underwater photographs of Palythoa caesia colonies at the study sites: (A) Ko Chan, (B) Ko Kong Sai Daeng, and (C) Ao Jak.

Extraction and filtration of MPs from Palythoa caesia

The P. caesia samples were thawed and subsequently washed with sterile distilled water. Morphometric measurements were obtained using a digital vernier caliper gauge micrometer, and weights were recorded with a digital balance. A tissue fragment of each specimen was photographed prior to microplastic isolation and pre-treatment. For microplastic extraction from the surface of tissue fragment, each sample was placed in a sterile 1000 mL glass beaker. A concentrated sodium chloride solution (1.2 g/mL) was prepared and filtered prior to use, and approximately 800 mL of the solution was added to each glass beaker, which was fully covered with aluminum foil to prevent contamination. The tissues were then gently rinsed with distilled water, and the rinsate was collected and transferred to the previous beaker. The solution containing MPs and other organic residues was mixed with 1–2 mL of 30% H2O2 and incubated in an oscillation incubator at 60 °C and 90 rpm for 24 h, followed by an additional 24 h at room temperature to ensure complete digestion. Subsequently, the remaining tissue fragments were transferred to clean beakers for further processing. The tissues fragments were treated with aforementioned protocol to extract microplastics from inner tissue. Once digested, the solutions from both surface and inner tissue layers was filtered onto Whatman GF/F glass microfiber filter membrane (0.7 μm pore size with a 47 mm diameter) in a glass filtration unit equipped with a vacuum pump to obtain the microplastic. After the filtration process, the filter paper containing the captured MPs was carefully transferred to clean and covered glass Petri dishes and dried for further observation.

Characterization and identification of MPs

A visual inspection was initially conducted to quantify and screen suspected MPs based on their physical characteristics. All particles presumed to be MPs were observed, photographed, and marked under a stereo microscope (ZEISS Model Stemi 508, Germany), with images captured using an AxioCam digital camera. The size of each microplastic particle was measured using the ZEISS Labscope 4.3 image-processing software. Subsequently, the sizes, shapes, and colors of the MPs were recorded. The particles were categorized into three shape types: fibers, fragments, and pellets. For size measurements, fibrous MPs were measured along their entire length, whereas fragmented, filmy, and granular particles were measured along their longest axis (Ding et al., 2019). Additionally, MPs were classified into the following size ranges: 50–500 μm, 501–1,000 μm, 1,001–2,000 μm, 2,001–3,000 μm, 3,001–4,000 μm, and 4,001–5,000 μm, based on the classification recommended by the frameworks in marine microplastic research (Masura et al., 2015; Frias and Nash, 2019), designed to capture fine-scale variations in particle size that may influence ingestion potential, retention, and transport behavior within marine organisms and reef environments. Transparent and white MPs were grouped as colorless, while all other colors were categorized as colored.

The identification of microplastics (MPs) was performed using Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy (Bruker ALPHA II Compact FT-IR Spectrometer, Germany) with a detection limit of 50 µm. Spectra were recorded across the range of 4000–400 cm-¹ at a resolution of 2 cm-¹. The resulting spectra were analyzed with OPUS software and compared against a reference database of standard polymer compounds to determine the identity of the particles. Spectra exhibiting a similarity match of ≥70% with reference materials were accepted and classified as microplastic polymers. Non-plastic materials were excluded from the counts, and the total number of MPs was subsequently recalculated.

Contamination controls

All those procedures are carried out with maximum care in order to avoid contamination during analysis of samples. Before use all sampling tools and materials were thoroughly cleaned three times with distilled water filtered through a GF/C (diameter 47 mm: pore size 1.2 μm) glass microfiber filter (Whatman, UK) and rinsed with acetone to minimize contaminants (Li et al., 2015). Common measures such as washing glass containers, wearing cotton lab and nitrile gloves, filtering solutions, and etc. were taken to prevent external contaminations as Ding et al. (2019) described. The microplastic identification was conducted in a closed lab, and the stereo-microscope was covered with a glass cover between the particle verification. Filter papers were carefully examined under a microscope before use to ensure that no pre-existing particles or contaminants were present. Care was taken to complete the procedures as soon as possible uncontaminated. Aluminum foil was used to cover the beakers during the entire process. To account for procedural contaminations, blanks with the same volume of 30% H2O2 but no tissues were performed simultaneously during sample processing procedures. To avoid contamination by air, the laboratory’s ventilation and windows were kept closed at all times. The number of microplastics observed in the blank controls (0–2 particles per filter) was subtracted from that counted in the analyzed samples to correct for background contamination. The particles detected in blanks were mainly transparent or white fibers within the 100–500 μm size range, composed primarily of polyethylene and polypropylene. Their abundance (<5% of the mean sample count) and uniform morphology indicate minimal influence of laboratory contamination on the results.

Statistical analysis

The abundance of microplastics was expressed as both particles·cm-² and particles·g-¹ wet weight (w.w.). The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test to confirm the normal distribution of data. The differences in MP abundance among the study sites were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For the significant results (p < 0.05), post-hoc comparisons were conducted using the Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) tests to identify specific differences between the groups. Independent samples Student’s t-tests were conducted to compare mean micro plastic abundance between the surface and inner tissue layers. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.5.1. Data were presented as means ± standard deviations (SD) unless otherwise specified.

Results

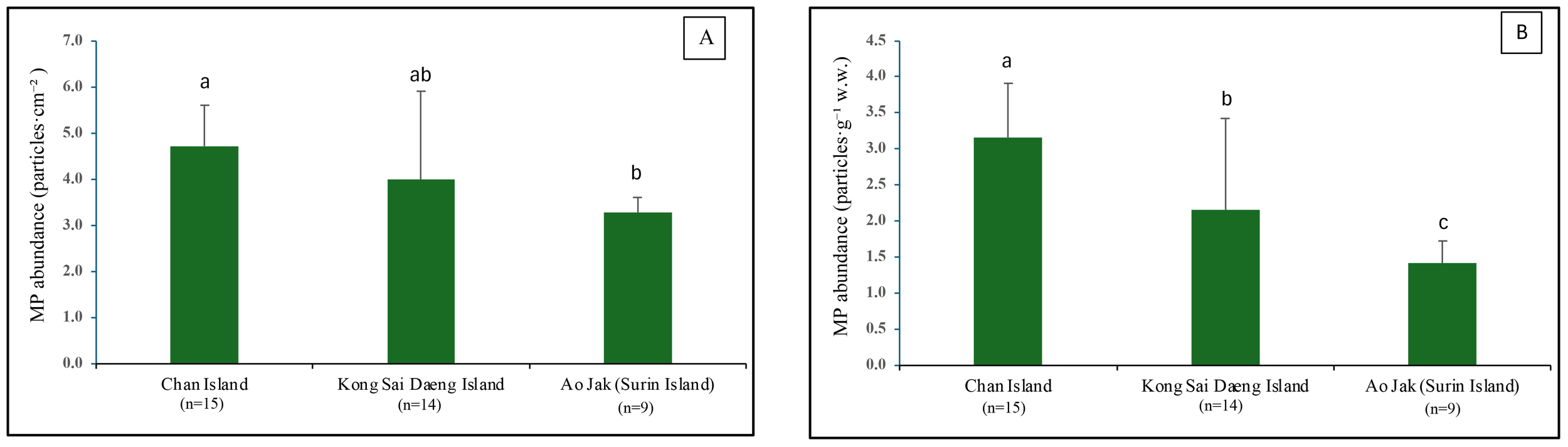

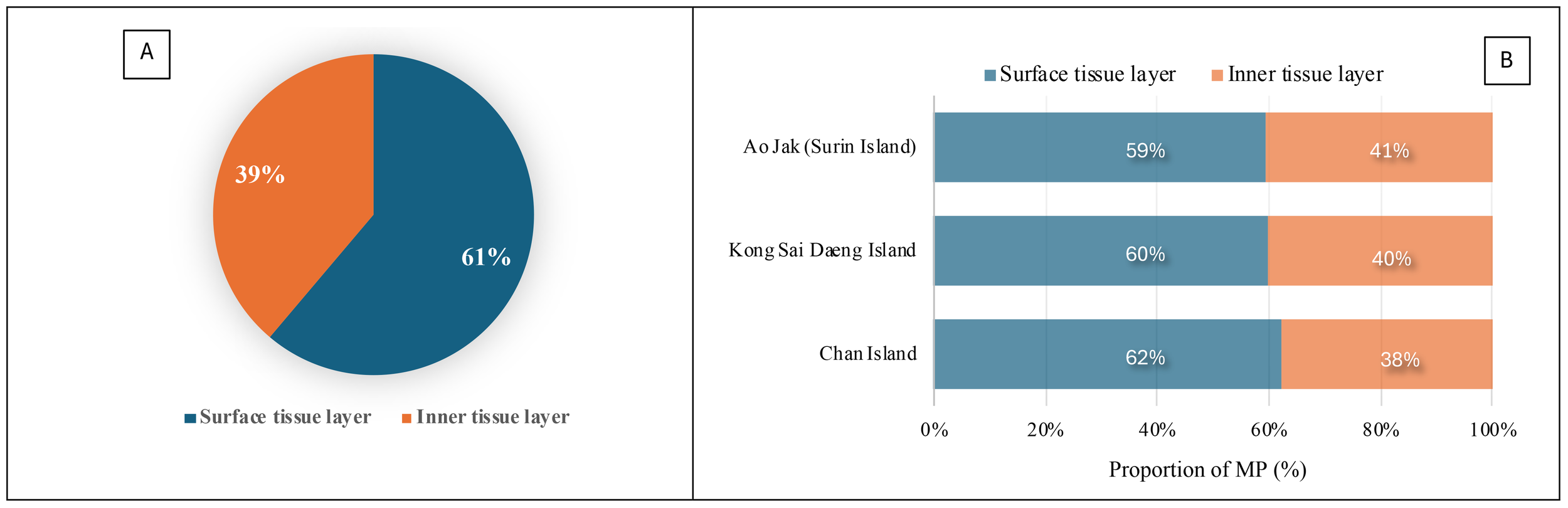

Abundance of MPs in Palythoa caesia

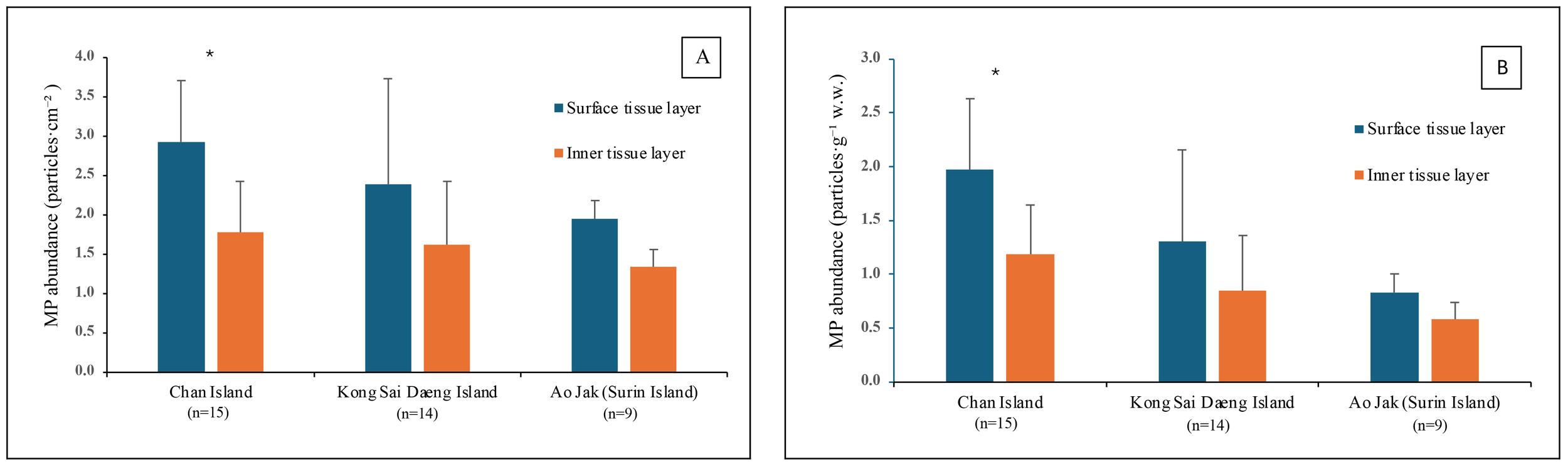

A total of 624 MPs was collected from 38 colonies of P. caesia were examined across all study sites, and microplastics were detected in 100% of the colonies, with quantities ranging from 5 to 30 particles/colony. The average microplastic abundance across all sites was 4.11 ± 1.38 particles·cm-² or 2.37 ± 1.13 particles·g-¹ w.w. Among the study sites, the highest abundance was recorded at Chan Island (4.70 ± 0.90 particles·cm-² or 3.15 ± 0.76 particles·g-¹ w.w.), followed by Kong Sai Daeng Island (4.00 ± 1.90 particles·cm-² or 2.16 ± 1.26 particles·g-¹ w.w.) and Ao Jak (3.28 ± 0.32 particles·cm-² or 1.41 ± 0.31 particles·g-¹ w.w.) (Figure 3). Considering the MP abundance by surface area, a statistically significant difference in microplastic abundance was detected between Chan Island and Ao Jak (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD test, F = 3.43, p < 0.05). In terms of the abundance by sample weight, there were statistical differences among locations (F = 10.66, p<0.05). For MPs detected across various structural components, including the surface and inner tissue layers at all study sites, the proportion adhering to the surface layer was higher than that in the inner tissues, accounting for 61% and 39% of the total number of MPs, respectively. Binomial test revealed the significant differences between the two proportions (Binomial test = 175, p<0.01). Ko Chan had the highest proportion of MPs on the surface tissue layers, followed by Ko Kong Sai Dang and Ao Jak (Figure 4). The abundance of MPs found on the surface (1.46 ± 0.89 particles·g-¹ w.w.) was significantly higher than that in the inner tissues (0.93 ± 0.65 particles·g-¹ w.w.) (t-test, t = 2.96, p < 0.01) (Figure 5).

Figure 3

Abundance of microplastics (MPs) detected in P. caesia samples collected from coral reefs at the study sites. (A) MPs abundance expressed as particles·cm-². (B) MPs abundance expressed as particles·g-1w.w. Spatial variation in MP abundance assessed using one-way ANOVA. Shared letters indicate no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) based on Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test.

Figure 4

Proportion of microplastics (MPs) detected in the surface and inner tissue layers. (A) Combined data from all three study sites. (B) Data presented separately for each study site.

Figure 5

Abundance of microplastics (MPs) detected in the surface and inner tissue layers of Palythoa caesia collected from coral reefs at the study sites. (A) MP abundance expressed as particles·cm-². (B) MP abundance expressed as particles·g-¹ w.w. Asterisk indicates significant difference of mean MP abundance (t-test, p<0.05).

Characteristics of microplastics in Palythoa caesia

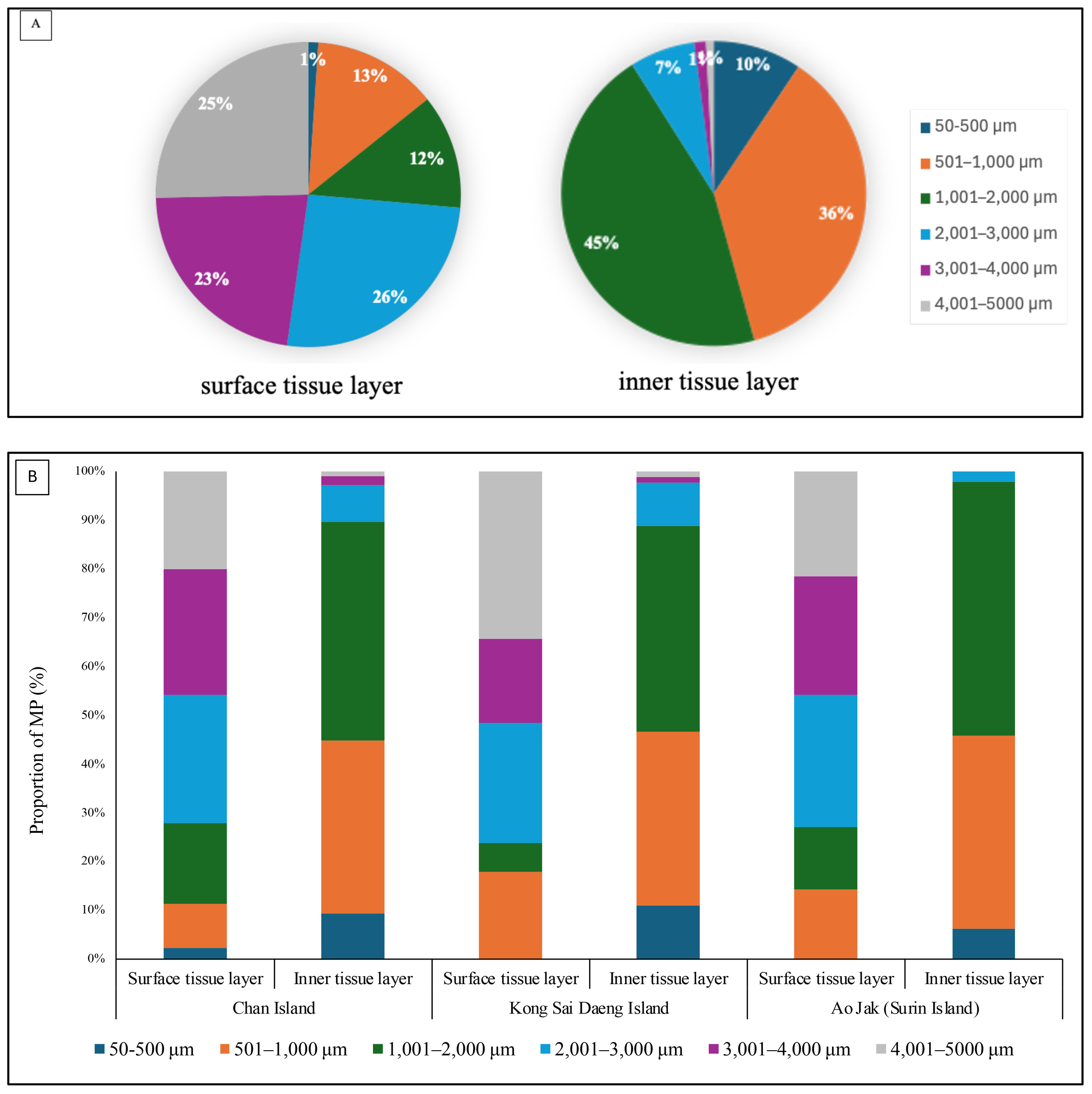

The relative abundance and characteristics of microplastics (MPs) in P. caesia were assessed based on size, morphology, color, and polymer composition in both the surface and inner tissue layers across all study sites. The size distribution of MPs differed slightly between tissue layers. In the surface tissue, MPs predominantly ranged from 2,001 to 3,000 μm, while those in the inner tissue were mainly within the 1,001 to 2,000 μm range (Figure 6). There was an association between the size distribution and tissue layers (surface tissue and inner tissue), where smaller size of MPs tended to be found in the inner tissue layer (χ2 = 261.10, p<0.01).

Figure 6

Relative abundance and size distribution of microplastics (MPs) detected in P. caesia specimens across all study sites. (A) Pie charts show the overall size distribution of MPs. (B) Bar graphs display the MP size distribution in the surface and inner tissue layers at each study site.

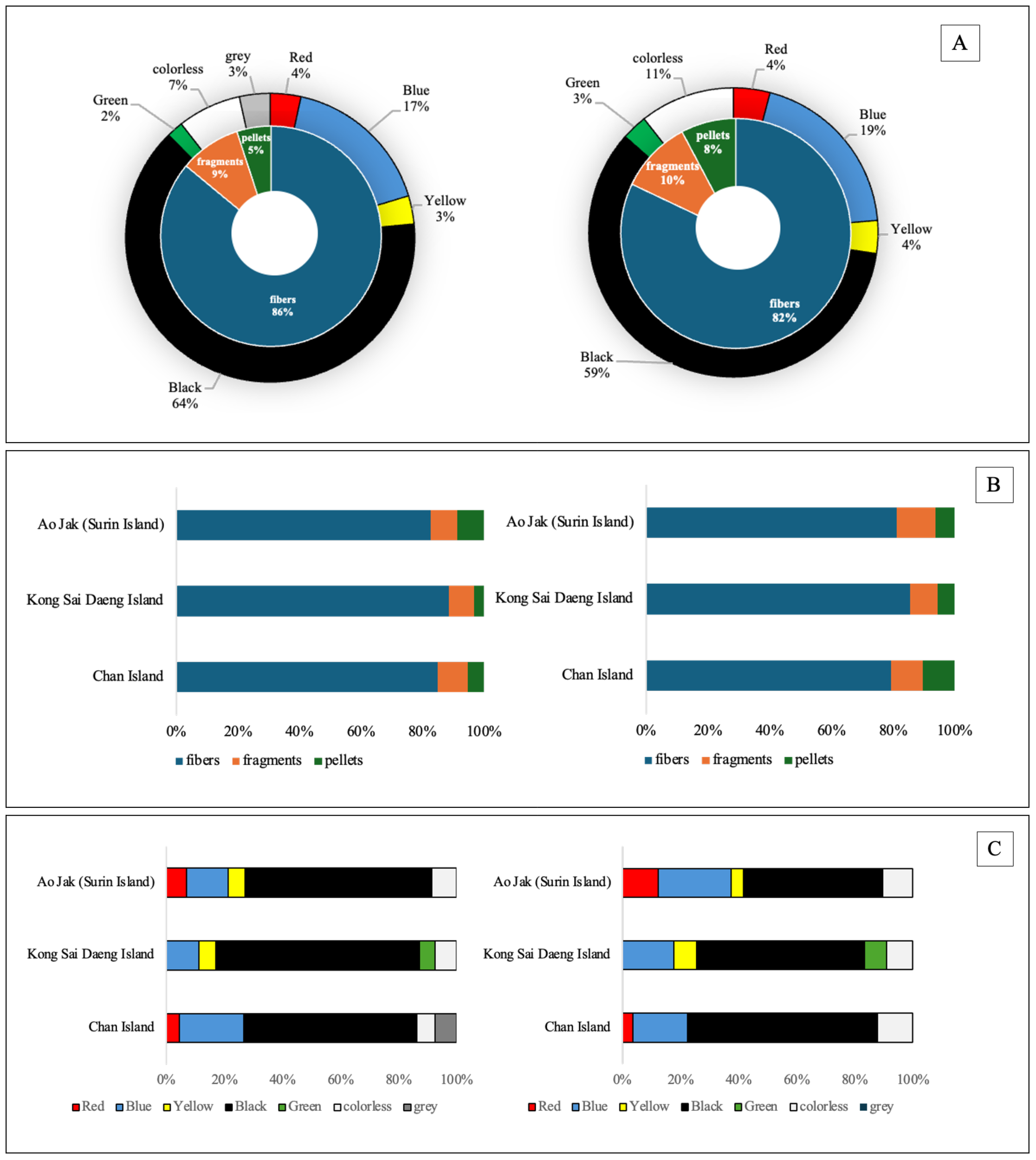

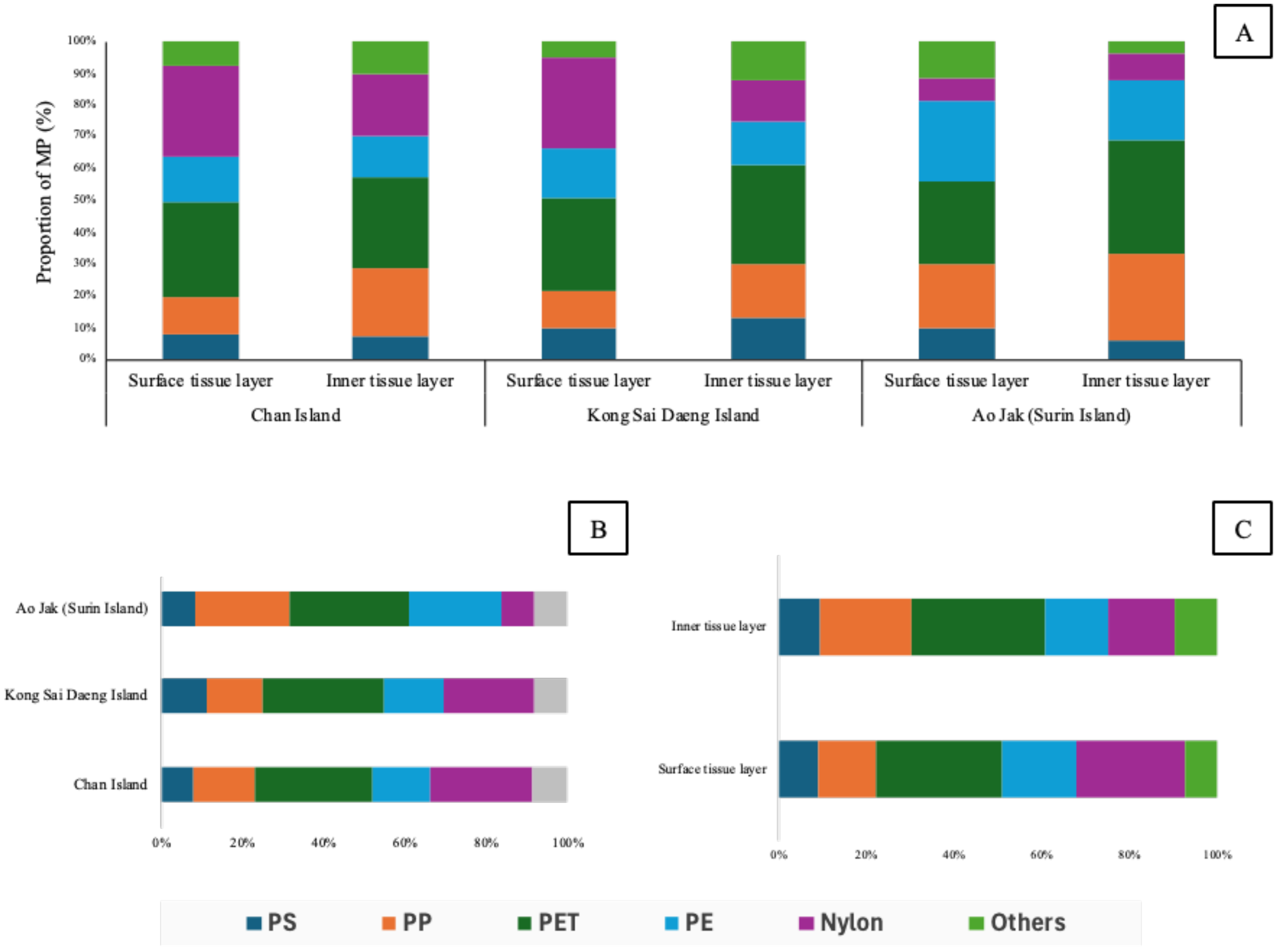

In terms of morphology, fibers were overwhelmingly dominant in both tissue compartments, comprising 86% of MPs in the surface layer and 82% in the inner layer. Fragments and pellets were less prevalent, accounting for 9% and 5% in the surface tissue and 10% and 8% in the inner tissue, respectively (Figures 7, 8). Color analysis revealed that black MPs were the most abundant in both tissue layers, representing 64% in the surface and 59% in the inner layer. Blue MPs followed in abundance (17% surface; 19% inner), while colorless and red particles accounted for moderate proportions (7–11% and 4%, respectively). Yellow, green, and grey particles were detected at lower frequencies (<5%), with relatively minor variation across sites (Figure 7). Considering the MPs of the size class 1001 - 2000 µm found in the inner tissue layer, about 86.5% were fibers and the other 13.5% were fragments. Most fibers were found black (71.9%) followed by blue (14.6%). Almost of fragment-shape MPs were blue (93.3%). Polymer composition analysis identified six major polymer types: polystyrene (PS), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyethylene (PE), nylon, and unidentified others. Among these, PP and PE were the most prevalent polymers in both tissue layers, reflecting their widespread use and environmental persistence. While overall polymer profiles were broadly similar across the study sites, site-specific variations were observed. Chan Island exhibited relatively higher proportions of PET and PS, whereas Ao Jak showed a more balanced representation of PP and nylon (Figure 9). Based on the chi-square test, there were no associations between study sites and size distribution (χ2 = 14.56, p=0.14), morphology (χ2 = 3.24, p=0.51), and polymer type (χ2 = 5.39, p=0.86).

Figure 7

Relative abundance and characteristics of MP morphologies and colors detected in P. caesia specimens. (A) Donut pie charts summarizing overall MP morphologies and colors; (B) Bar graphs showing the distribution of MP morphologies; and (C) Bar graphs displaying the proportions of MP colors at each study site. Each dataset is presented separately for the surface tissue layer (left) and the inner tissue layer (right).

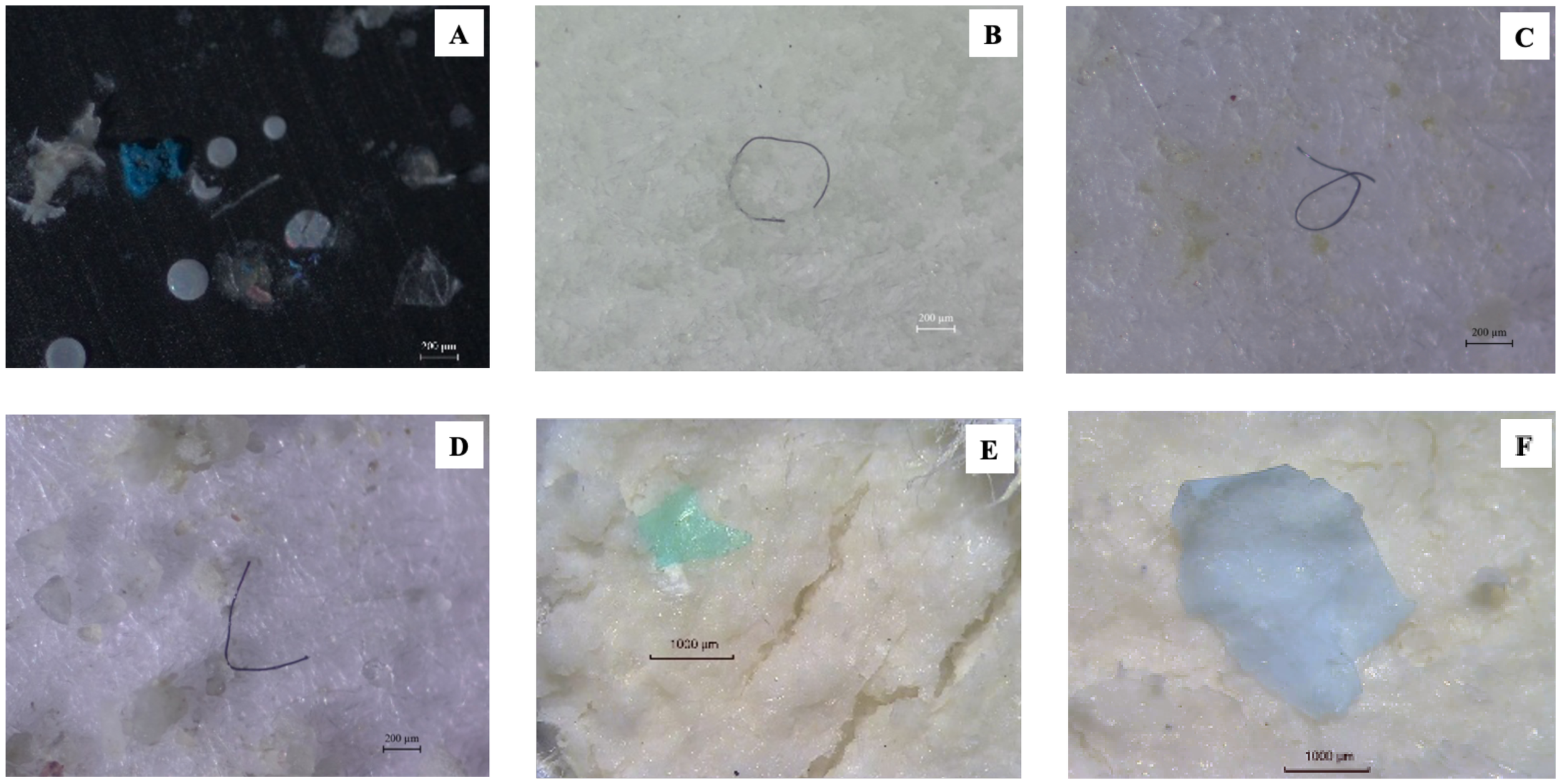

Figure 8

Characteristics of microplastics (MPs) identified in Palythoa caesia samples. (A–C) MPs observed in the surface tissue layer. (D–F) MPs observed in the inner tissue layer.

Figure 9

Composition and distribution of polymer types detected in Palythoa caesia across study sites and tissue layers. (A) Proportion of microplastic (MP) polymer types in the surface and inner tissue layers of P. caesia from each site (Ko Chan, Ko Kong Sai Daeng, and Ao Jak), (B) Comparison of polymer composition among study sites and (C) Overall distribution of polymer types comparing between the surface and inner tissue layers.

Discussion

Our findings clearly establish the pervasive presence of microplastics (MPs) in P. caesia colonies across all surveyed coral reef sites, with a 100% detection rate and concentrations ranging from 5 to 30 particles per colony. This outcome is consistent with the growing body of literature reporting widespread MP contamination in marine environments and its accumulation in diverse marine taxa, including scleractinian corals (Chamchoy et al., 2018; Lim et al., 2022; Soares et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2025; Barros et al., 2025). The average MP abundance recorded in this study (4.11 ± 1.38 particles·cm-² or 2.37 ± 1.13 particles·g-¹ w.w.) is comparable to, and in some instances exceeds, values previously reported for other coral species and reef systems worldwide, thereby underscoring the substantial MP burden affecting these ecosystems (Lim et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2025). Some studies, for example, Morais et al. (2020) and Sfriso et al. (2020), reported MP contamination in sea anemones (Bunodosoma cangicum and Edwardsia meridionalis), which were varied from 0.4 – 1.6 pieces per individual. The elevated MP accumulation observed in P. caesia is likely influenced, at least in part, by its distinctive biological architecture and ecological strategy, which may enhance its capacity to trap and retain particulate matter from the surrounding environment. As a colonial zoanthid, Palythoa spp produces coenenchyme that facilitates the incorporation of surrounding sediment and particulate matter into its tissue matrix, supporting the formation of a rigid structural framework (Haywick and Mueller, 1997). This behavior likely enhances the passive entrapment and retention of MPs from the surrounding environment, resulting in greater accumulation compared to non-framework-forming or soft-bodied benthic invertebrates. The significant variation in microplastic abundance among the study sites, with Chan Island exhibiting the highest levels (4.70 ± 0.90 particles·cm-² or 3.15 ± 0.76 particles·g-¹ w.w.), followed by Kong Sai Daeng Island and Ao Jak, suggests localized differences in microplastic pollution. This spatial variability is likely influenced by proximity to anthropogenic activities such as tourism, industrial waste discharge, and coastal populations, which are recognized as major sources of plastic pollution in marine environments (Hansani et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Higher levels of human activity are commonly associated with increased plastic waste generation, which can degrade into microplastics and be transported into adjacent coral reef ecosystems (Zhang et al., 2023; Sánchez-Campos et al., 2024; Santana et al., 2025). The observed spatial differences in microplastic abundance among sites suggest that local environmental pressures, such as coastal development, tourism intensity, and land-based runoff, play a critical role in shaping microplastic contamination patterns. These findings highlight the need for localized monitoring and mitigation strategies to effectively address microplastic pollution in coral reef habitats.

Our investigation into the distribution of microplastics within the structural components of the zoanthid P. caesia revealed a significantly higher proportion adhering to the surface layer (61%) compared to the inner tissues (39%). This consistent pattern across all study sites suggests that surface adhesion plays a critical role in the initial interactions between microplastics and zoanthid colonies. Similar to scleractinian corals, zoanthids secrete mucus that facilitates the entrapment of suspended particulates, including microplastics, from the surrounding water column (Lim et al., 2022; Barros et al., 2025). While this mucus-mediated surface retention may serve as both a feeding strategy for capturing prey and an initial protective mechanism against suspended particles, it can also result in the unintended entrapment of microplastics as bycatch, potentially leading to adverse physiological effects (Pantos, 2022; Kim et al., 2024; Reuning et al., 2025). Although most ingested microplastics are egested after ingestion, as reported in many marine invertebrates including corals and anemones (Tahsin et al., 2023), continuous exposure and surface accumulation may still impose sublethal stress on zoanthids by interfering with feeding, respiration, and mucus production (Rocha et al., 2020; da Silva Batista & Amado, 2023). The presence of MPs within the inner tissues of P. caesia suggests active uptake or internalization by the polyps, referring to the process by which particles are engulfed or translocated from the external surface into the endodermal tissue through phagocytosis or endocytosis. Zoanthids, as opportunistic suspension feeders, can mistake microplastics within certain size ranges for food particles and ingest them (Pantos, 2022). MPs may accumulate within the tissues, potentially causing physical damage, impaired nutrient assimilation, growth inhibition, and physiological stress responses (Bove et al., 2023; López et al., 2025).

MP contamination in marine organisms is a growing concern, and the current findings in P. caesia provide valuable insights into the distribution and characteristics of microplastics within different tissue layers. The observed size differences, with larger MPs (2,001-3,000 µm) predominantly found in the surface tissue and smaller MPs (1,001-2,000 µm) in the inner tissue, align with recent research suggesting a size-dependent uptake and translocation mechanism in marine invertebrates (Li et al., 2023). This consistent pattern across all study sites reinforces the idea of similar particle penetration and retention mechanisms in P. caesia, warranting further investigation into the physiological processes facilitating this differentiation.

The overwhelming dominance of fibrous MPs in both surface (86%) and inner (82%) tissue layers of P. caesia is a critical finding that resonates with numerous studies on MP pollution in aquatic environments (Jensen et al., 2019; Isa et al., 2024; Reichert et al., 2024). Fibers are frequently reported as the most abundant MP morphology in various marine organisms and water samples, often attributed to the widespread use and shedding of synthetic textiles. This prevalence suggests that fibrous MPs pose a significant threat to P. caesia, mainly due to their elongated and flexible structure, which facilitates entanglement and adherence to the colony surface. Such fibers may also mimic filamentous organic matter or planktonic detritus, increasing the likelihood of incidental capture during feeding activities rather than intentional ingestion (Li et al., 2018). Similar observations of high fibrous MP accumulation have been reported in other marine invertebrates, such as bivalves and corals, indicating that suspension- and filter-feeding organisms with mucus-mediated particle capture mechanisms are broadly susceptible to this specific MP morphology. The consistent morphological pattern between tissue layers highlights similar pathways of particle adherence and translocation within P. caesia, suggesting that fibrous MPs can penetrate and be retained across tissue compartments through comparable physical or physiological mechanisms, as previously reported for corals and other cnidarians (Rotjan et al., 2019; Corinaldesi et al., 2021).

The color analysis of MPs in P. caesia revealed a consistent dominance of black MPs in both surface (64%) and inner (59%) tissue layers, followed by blue MPs (17% surface; 19% inner). This finding aligns with recent literature indicating that black and blue MPs are frequently reported as prevalent colors in marine environments and organisms. The high abundance of black MPs could be attributed to the degradation of common plastic products like tires, fishing gear, or agricultural films, which often contain carbon black as a pigment (Li et al., 2023). The consistent distribution of these colors across tissue layers suggests that the presence of colored MPs in P. caesia’s tissues may reflect selective ingestion or retention processes. Several studies suggest that the color of microplastics significantly influences ingestion patterns among marine organisms, including corals and fish. Marmara et al. (2023) reported that black fibrous microplastics are among the most frequently found types in color among pisces, mollusca, and crustacea. This could be due to black particles are similar in color to their natural food sources, such as zooplankton, which might result in being mistakenly ingested by such marine animals (Nie et al., 2019).

Regarding polymer composition, polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE) were the most prevalent types in both tissue layers, consistent with global production and consumption patterns of these plastics. Their widespread use in packaging, ropes, and fishing nets contributes significantly to their environmental ubiquity and subsequent uptake by marine organisms (Coyle et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2024). While the overall polymer profiles between inner and surface tissue layers were broadly similar, the observed site-specific variations in polymer composition remain noteworthy. For instance, Chan Island, the predominance of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polystyrene (PS) likely reflects direct inputs from land-based tourism and shoreline commercial activities. PET, commonly used in beverage bottles and transparent food packaging, is often introduced through improper disposal of single-use plastics by visitors and vendors along the coast. In contrast, PS, frequently found in expanded foam food containers and lightweight construction materials, may originate from nearby resort infrastructure and coastal development. Conversely, Ao Jak exhibited a comparatively balanced composition of polypropylene (PP) and nylon. These polymers are typical of marine-derived materials, with PP commonly used in ropes, fishing nets, and marine lines, while nylon is widely used in fishing gear, buoys, and boating accessories. Given the limited human activity in the area, these MPs are plausibly derived from drifting fishing debris transported by surface currents or monsoonal circulation from adjacent fishing grounds. These geographical differences underscore the importance of site-specific pollution sources in shaping the polymer profiles of MPs detected in marine organisms. This study was designed to detect the abundance of microplastics during wet season as several studies reported that wet seasons often coincide with elevated microplastic concentrations in water and sediments, driven by increased runoff, river discharge, stormwater overflow, and resuspension caused by hydrodynamic activity (Gao et al., 2022; Cheung and Not, 2023). It is important to note that the actual microplastic abundance may be underestimated, as the FTIR instrument used in this study could not detect particles smaller than 50 µm.

Based on our findings, the mean abundance of microplastics in corals at Ko Chan was 4.70 particles.cm-2 or 3.15 particles. g -2 while the abundance of microplastics in seawater nearby was about 2.06 particles/m³ in seawater (Phaksopa et al., 2022). This confirms that corals can act as a sink for MPs, due to their filter-feeding and mucus-trapping abilities, which facilitate the accumulation of particles from both the water column and suspended sediments (Soares et al., 2023). Microplastic contamination can link with the concentration of MPs in seawater. Several studies indicate that the abundance of microplastics (MPs) in coral tissues show a positive relationship with MP concentrations in surrounding seawater. In the coral reef ecosystems of Sri Lanka, a significant positive correlation was found between MP abundance in coral tissues and surface water, with a correlation coefficient of 0.65, indicating that the reef environment contributes to coral MP enrichment (Abeysinghe et al., 2024). Additionally, the concentration of MPs in corals is generally higher than that in surrounding seawater, for example, the study of coral reefs in Sri Lanka show the MP abundance of 546.7 particles.kg-1 while only 9.8 particles.m-3 was found in seawater (Hansani et al., 2023).

The widespread occurrence and site-specific variation of MP contamination in P. caesia underscore the need for targeted management approaches that address localized sources of pollution. Elevated concentrations of PET and PS detected at Chan Island highlight the importance of enforcing stricter controls on single-use plastics and improving waste management infrastructure in tourism-intensive zones. In contrast, for protected and uninhabited sites such as Ao Jak, management efforts should focus on regulating tourism-related waste, particularly from recreational boating and snorkeling activities, through enhanced visitor guidelines and regular clean-up operations. To support evidence-based policy development, long-term biomonitoring programs utilizing benthic indicator species are recommended to track spatiotemporal trends in MP pollution. Integrating microplastic mitigation strategies into marine spatial planning and national coastal zone management frameworks will be essential for safeguarding reef ecosystem resilience under escalating anthropogenic pressures. Public education and active stakeholder engagement remain critical to fostering an inclusive and collaborative governance approach for effective plastic pollution reduction.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

TY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Supervision. CC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. WK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. WB: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. CP: Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. PK: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. WS: Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI), the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) by the Program Management Unit Competitiveness (PMUC), and Ramkhamhaeng University (RU).

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to the staff of the Marine Biodiversity Research Group, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Ramkhamhaeng University, for their support and assistance in the field. A great attitude must be expressed to local communities and tour operators, who provided valuable local information for research planning. We would also like to express our sincere appreciation to the staff of Mu Ko Surin National Park for their kind support, facilitation, and cooperation during the fieldwork.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was utilized to enhance the language, improve clarity, and format the text in compliance with journal guidelines. All scientific content, data analysis, and conclusions were independently developed, written, and verified by the authors. The role of AI was strictly limited to editorial assistance, and the authors confirm that no confidential, personal, or proprietary data were input into the AI system.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abeysinghe S. Guruge P. Kumara T. P. (2024). Microplastic pollution status in the coral reef ecosystems on the southern and western coasts of Sri Lanka during the southwest monsoon. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 206, 116713. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4702871

2

Albertoni L. F. Dal Pont G. De Souza-Bastos L. R. Ostrensky A. Da Costa J. H. A. Sadauskas-Henrique H. (2024). Time-dependent biochemical responses of the zoanthid Zoanthus sp. exposed to polyvinyl chloride microplastics. Ecotoxicology Environ. Contamination19, 10–19. doi: 10.5132/eec.2024.01.02

3

Andrady A. L. (2017). The plastic in microplastics: a review. Mar. pollut. Bull.119, 12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.01.082

4

Barros Y. Soares M. O. Ayala A. P. Neto V. S. Giarrizzo T. Cavalcante R. M. (2025). First evidence of microplastic contamination in the tissue and skeletons of the keystone reef-building coral Siderastrea stellata in coastal reefs. Discover Oceans2, 20. doi: 10.1007/s44289-025-00059-4

5

Bashir S. M. Kimiko S. Mak C. W. Fang J. K. H. Gonçalves D. (2021). Personal care and cosmetic products as a potential source of environmental contamination by microplastics in a densely populated Asian city. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.683482

6

Biswas T. Pal S. C. Saha A. Ruidas D. Shit M. Islam A. R. M. T. et al (2024). Microplastics in the coral ecosystems: a threat which needs more global att8ention. Ocean & Coastal Management249, 107012. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.107012

7

Bove C. B. Greene K. Sugierski S. Kriefall N. G. Huzar A. K. Hughes A. M. et al . (2023). Exposure to global change and microplastics elicits an immune response in an endangered coral. Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1037130

8

Browne M. A. Dissanayake A. Galloway T. S. Lowe D. M. Thompson R. C. (2008). Ingested microscopic plastic translocates to the circulatory system of the mussel, Mytilus edulis (L.). Environ. Sci. Technol.42, 5026–5031. doi: 10.1021/es800249a

9

Carpenter E. J. Anderson S. J. Harvey G. R. Miklas H. P. Peck B. B. (1972). Polystyrene spherules in coastal waters. Science178, 749–750. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4062.749

10

Chamchoy C. Sutthacheep M. Sangiamdee D. Musig W. Boonmewisate S. Sangsawang L. et al . (2018). Microplastics in scleractinian corals from the upper Gulf of Thailand. Ramkhamhaeng Int. J. Sci. Technol.1, 1–8.

11

Chen C. F. Ju Y. R. Wang M. H. Lim Y. C. Chen C. W. Cheng Y. R. et al . (2025). Microplastic pollution in stony coral skeletons and tissues: A case study of accumulation and interrelationship in South Penghu Marine National Park, Taiwan Strait. J. Hazardous Materials484, 136761. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136761

12

Cheung C. K. H. Not C. (2023). Impacts of extreme weather events on microplastic distribution in coastal environments. Sci. Total Environ.904, 166723. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166723

13

Cheung P. K. Fok L. (2017). Characterisation of plastic microbeads in facial scrubs and their estimated emissions in Mainland China. Water Res.122, 53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.05.053

14

Cole M. Lindeque P. Fileman E. S. Halsband C. Goodhead R. M. Moger J. et al . (2013). Microplastic ingestion by zooplankton. Environ. Sci. Technol.47, 6646–6655. doi: 10.1021/es400663f

15

Corinaldesi C. Canensi S. Dell’Anno A. Tangherlini M. Di Capua I. Varrella S. et al . (2021). Multiple impacts of microplastics can threaten marine habitat-forming species. Commun. Biol.4, 431. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-01961-1

16

Cornwall C. E. Comeau S. McCulloch M. T. (2021). Coralline algae elevate pH at the site of calcification under ocean acidification. Global Change Biol.27, 918–929. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13673

17

Coyle R. Hardiman G. Driscoll K. O. (2020). Microplastics in the marine environment: a review of their sources, distribution processes, uptake and exchange in ecosystems. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2, 100010. doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100010

18

da Silva Batista K. A. Amado E. M. (2023). Impacts of marine microplastic pollution on sea anemones: State of the art and future perspectives. Licuri Publishing, 104–117. doi: 10.58203/Licuri.21721

19

Delorme A. E. Lebreton L. Royer S. J. Kāne K. Arhant M. Le Gall M. et al . (2025). Assessing plastic brittleness to understand secondary microplastic formation on beaches: a hotspot for weathered marine plastics. Microplastics Nanoplastics5, 25. doi: 10.1186/s43591-025-00128-7

20

Ding J. Jiang F. Li J. Wang Z. Sun C. Wang Z. et al . (2019). Microplastics in the coral reef systems from Xisha Islands of South China Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol.53, 8036–8046. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b01452

21

Doney S. C. Busch D. S. Cooley S. R. Kroeker K. J. (2020). The impacts of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and reliant human communities. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour.45, 83–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-083019

22

Frias J. P. Nash R. (2019). Microplastics: Finding a consensus on the definition. Mar. pollut. Bull.138, 145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.11.022

23

Gao Y. Fan K. Zeng Y. Li H. Mai Y. Z. Liu Q. et al . (2022). Abundance, composition, and potential ecological risks of microplastics in surface water at different seasons in the pearl river delta, China. Water14, 2545. doi: 10.3390/w14162545

24

Gao S. Li Z. Zhang S. (2024). Trophic transfer and biomagnification of microplastics through food webs in coastal waters: a new perspective from a mass balance model. Mar. pollut. Bull.200, 116082. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116082

25

Hansani K. U. D. N. Thilakarathne E. P. D. N. Koongolla J. B. Gunathilaka W. Perera B. I. G. Weerasingha W. M. P. U. et al . (2023). Contamination of microplastics in tropical coral reef ecosystems of Sri Lanka. Mar. pollut. Bull.188, 115299. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115299

26

Hartmann N. B. Huffer T. Thompson R. C. Hassellov M. Verschoor A. Daugaard A. E. et al . (2019). Are we speaking the same language? Recommendations for a definition and categorization framework for plastic debris. Environ. Sci. Technol.53, 1039–1047. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b05297

27

Hatzonikolakis Y. Raitsos D. E. Sailley S. F. Digka N. Theodorou I. Tsiaras K. et al . (2024). Assessing the physiological effects of microplastics on cultured mussels in the Mediterranean Sea. Environ. pollut.363, 125052. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2024.125052

28

Haywick D. W. Mueller E. M. (1997). Sediment retention in encrusting Palythoa spp.: a biological twist to a geological process. Coral Reefs16, 39–46. doi: 10.1007/S003380050057

29

Houlbrèque F. Ferrier-Pagès C. (2009). Heterotrophy in tropical scleractinian corals. Biol. Rev.84, 1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00058.x

30

Huffman Ringwood A. (2021). Bivalves as biological sieves: bioreactivity pathways of microplastics and nanoplastics. Biol. Bull.241, 185–195. doi: 10.1086/716259

31

Hughes T. P. Kerry J. T. Baird A. H. Connolly S. R. Dietzel A. Eakin C. M. et al . (2019). Global warming impairs stock–recruitment dynamics of corals. Nature568, 387–390. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1081-y

32

Isa V. Seveso D. Diamante L. Montalbetti E. Montano S. Gobbato J. et al . (2024). Physical and cellular impact of environmentally relevant microplastic exposure on thermally challenged Pocillopora damicornis (Cnidaria, Scleractinia). Sci. Total Environ.918, 170651. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170651

33

Isobe A. Azuma T. Cordova M. R. Cózar A. Galgani F. Hagita R. et al . (2021). A multilevel dataset of microplastic abundance in the world's upper ocean and the Laurentian Great Lakes. Microplastics Nanoplastics1, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s43591-021-00013-z

34

Jensen L. H. Motti C. A. Garm A. Tonin H. Kroon F. J. (2019). Sources, distribution and fate of microfibres on the great barrier reef, Australia. Sci. Rep.9, 9021. doi: 10.1038/S41598-019-45340-7

35

Jeong C.-B. Kang H.-M. Lee M.-C. Kim D.-H. Han J. Hwang D.-S. et al . (2021). Adverse effects of microplastics and oxidative stress-induced MAPK/Nrf2 pathway-mediated defense mechanisms in the marine copepod Paracyclopina nana. Sci. Rep.11, 1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep41323

36

Jiang L. Sun Y.-F. Zhou G. Tong H. Huang L. Yu X. et al . (2022). Ocean acidification elicits differential bleaching and gene expression patterns in larval reef coral Pocillopora damicornis under heat stress. Sci. Total Environ.842, 156851. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156851

37

Jovanović B. (2017). Ingestion of microplastics by fish and its potential consequences from a physical perspective. Integrated Environ. Assess. Manage.13, 510–515. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1913

38

Khan A. Rountos K. J. (2025). Evaluation of microplastics in marine selective and non-selective suspension-feeding benthic invertebrates. Mar. Environ. Res.209, 107205. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2025.107205

39

Kim A. R. Mitra S. K. Zhao B. (2024). Unlocking passive collection of microplastics in coral reefs by adhesion measurements. ACS ES&T Water4, 5653–5659. doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.4c00650

40

Lapointe B. E. Brewton R. A. Herren L. W. Porter J. W. Hu C. (2019). Nitrogen enrichment, altered stoichiometry, and coral reef decline at Looe Key, Florida Keys, USA. Mar. Biol.166, 108. doi: 10.1007/s00227-019-3538-9

41

Li Y. Chen W. Yang S. Wang K. Yu W. (2023). Size-dependent accumulation and trophic transfer of microplastics in a marine food web. Environ. pollut.318, 120857. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172470

42

Li J. Green C. Reynolds A. Shi H. Rotchell J. M. (2018). Microplastics in mussels sampled from coastal waters and supermarkets in the United Kingdom. Environ. pollut.241, 35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.038

43

Li J. Yang D. Li L. Jabeen K. Shi H. (2015). Microplastics in commercial bivalves from China. Environ. pollut.207, 190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.09.018

44

Lim Y. C. Chen C. W. Cheng Y. R. Chen C. F. Dong C. D. (2022). Impacts of microplastics on scleractinian corals nearshore Liuqiu Island, southwestern Taiwan. Environ. pollut.306, 119371. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119371

45

López M. A. Tirpitz V. Do M. S. Czermak M. Ferrier-Pagés C. Reichert J. et al . (2025). Heterotrophic feeding modulates the effects of microplastic on corals, but not when combined with heat stress. Sci. Total Environ.972, 179026. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.179026

46

Marmara D. Katsanevakis S. Brundo M. V. Tiralongo F. Ignoto S. Krasakopoulou E. (2023). Microplastics ingestion by marine fauna with a particular focus on commercial species: a systematic review. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1240969. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1240969

47

Martin D. Gil J. Abgarian C. Evans E. Turner E. M. Jr Nygren A. (2014). Coralliophila from Grand Cayman: Specialized coral predator or parasite?. Coral Reefs33, 1017. doi: 10.1007/S00338-014-1190-X

48

Masura J. Baker J. Foster G. Arthurs C. (2015). Laboratory methods for the analysis of microplastics in the marine environment: recommendations for quantifying synthetic particles in waters and sediments. NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS-OR&R, 48. Available online at: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/10296 (Accessed November 20, 2025).

49

McHale M. Sheehan K. L. (2024). Bioaccumulation, transfer, and impacts of microplastics in aquatic food chains. J. Environ. Exposure Assess.3, 15. doi: 10.20517/jeea.2023.49

50

Morais L. M. S. Sarti F. Chelazzi D. Cincinelli A. Giarrizzo T. Martinelli Filho J. E. (2020). The sea anemone Bunodosoma cangicum as a potential biomonitor for microplastics contamination on the Brazilian Amazon coast. Environ. pollut.265, 114817. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114817

51

Muscatine L. Porter J. W. (1977). Reef corals: mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. BioScience27, 454–460. doi: 10.2307/1297526

52

Neely K. L. Nowicki R. J. Dobler M. A. Chaparro A. A. Miller S. M. Toth K. A. (2024). Too hot to handle? The impact of the 2023 marine heatwave on Florida Keys coral. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1489273

53

Nie H. Wang J. Xu K. Huang Y. Yan M. (2019). Microplastic pollution in water and fish samples around Nanxun Reef in Nansha Islands, South China Sea. Sci. Total Environ.696, 134022. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134022

54

Nunes B. Z. Huang Y. Ribeiro V. V. Wu S. Holbech H. Moreira L. B. et al . (2023). Microplastic contamination in seawater across global marine protected areas boundaries. Environ. pollut.316, 120692. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120692

55

Nurdjaman S. Nasution M. I. Johan O. Napitupulu G. Saleh E. (2023). Impact of climate change on coral reefs degradation at West Lombok, Indonesia. Jurnal Kelautan Tropis26, 451–463. doi: 10.14710/jkt.v26i3.18540

56

Obuchi M. Reimer J. D. (2011). Does Acanthaster planci preferably prey on the reef zoanthid Palythoa tuberculosa?. Galaxea, Journal of Coral Reef Studies13, 7. doi: 10.3755/galaxea.13.7

57

Okubo N. Takahashi S. Nakano Y. (2018). Microplastics disturb the anthozoan-algae symbiotic relationship. Mar. pollut. Bull.135, 83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.07.016

58

Okubo N. Tamura-Nakano M. Watanabe T. (2020). Experimental observation of microplastics invading the endoderm of anthozoan polyps. Mar. Environ. Res.162, 105125. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.105125

59

Pantos O. (2022). Microplastics: impacts on corals and other reef organisms. Emerging Topics Life Sci.6, 81–93. doi: 10.1042/ETLS20210236

60

Phaksopa J. Sukhsangchan R. Keawsang R. Tanapivattanakul K. Asvakittimakul B. Thamrongnawasawat T. et al . (2022). Assessment of Microplastics in Green Mussel (Perna viridis) and Surrounding Environments around Sri Racha Bay, Thailand. Sustainability15, 9. doi: 10.3390/su15010009

61

Prakash S. (2024). Microplastics in the Ocean and their Consequences: Coral Reef Case Study. Journal Article. doi: 10.58445/rars.2079

62

Porter A. Godbold J. A. Lewis C. N. Nunes J. D. C. C. Hauton C. (2023). Microplastic burden in marine benthic invertebrates depends on species traits and feeding ecology within biogeographical provinces. Nat. Commun.14, 8023. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43788-w

63

Reichert J. Schellenberg J. Schubert P. Wilke T. (2018). Responses of reef building corals to microplastic exposure. Environ. pollut.237, 955–960. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.11.006

64

Reichert J. Tirpitz V. Plaza K. Wörner E. Bösser L. Kühn S. et al . (2024). Common types of microdebris affect the physiology of reef-building corals. Sci. Total Environ.912, 169276. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169276

65

Reuning L. Hildebrandt L. Kersting D. K. Pröfrock D. (2025). High levels of microplastics and microrubber pollution in a remote, protected Mediterranean Cladocora caespitosa coral bed. Mar. pollut. Bull.217, 118070. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.118070

66

Rindelaub J. D. Salmond J. A. Fan W. Miskelly G. M. Dirks K. N. Henning S. et al . (2025). Aerosol mass concentrations and dry/wet deposition of atmospheric microplastics at a remote coastal location in New Zealand. Environ. pollut.372, 126034. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2025.126034

67

Rocha R. J. M. Rodrigues A. C. M. Campos D. Cícero L. H. Costa A. P. L. Silva D. A. M. et al . (2020). Do microplastics affect the zoanthid Zoanthus sociatus? Sci. Total Environ.713, 136659. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136659

68

Rotjan R. D. Sharp K. H. Gauthier A. E. Yelton R. Lopez E. M. B. Carilli J. et al . (2019). Patterns, dynamics and consequences of microplastic ingestion by the temperate coral, Astrangia poculata. Proc. R. Soc. B286, 20190726. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.0726

69

Sánchez-Campos M. Ponce-Vélez G. Sanvicente-Añorve L. Alatorre-Mendieta M. (2024). Microplastic contamination in three environmental compartments of a coastal lagoon in the southern Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Monit. Assess.196, 1012. doi: 10.1007/s10661-024-13156-2

70

Santana M. F. Tonin H. Vamvounis G. Van Herwerden L. Motti C. A. Kroon F. J. (2025). Predicting microplastic dynamics in coral reefs: presence, distribution, and bioavailability through field data and numerical simulation analysis. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res.32, 9655–9675. doi: 10.1007/s11356-025-36234-5

71

Savage G. Porter A. Simpson S. D. (2022). Uptake of microplastics by the snakelocks anemone (Anemonia viridis) is commonplace across environmental conditions. Sci. Total Environ.836, 155144. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155144

72

Setälä O. Fleming-Lehtinen V. Lehtiniemi M. (2018). Ingestion and transfer of microplastics in the planktonic food web. Environ. pollut.185, 77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.10.013

73

Sfriso A. A. Tomio Y. Rosso B. Gambaro A. Sfriso A. Corami F. et al . (2020). Microplastic accumulation in benthic invertebrates in Terra Nova Bay (Ross Sea, Antarctica). Environ. Int.137, 105587. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105587

74

Sharma D. Dhanker R. Bhawna, Tomar A. Raza S. Sharma A. (2024). “ Fishing Gears and Nets as a Source of Microplastic,” in Microplastic Pollution. Eds. ShahnawazM.AdetunjiC. O.DarM. A.ZhuD. ( Springer, Singapore). doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-8357-5_8

75

Soares M. O. Rizzo L. Neto A. R. X. Barros Y. Martinelli Filho J. E. Giarrizzo T. et al . (2023). Do coral reefs act as sinks for microplastics? Environ. pollut.337, 122509. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122509

76

Sonia Kumari A. Anto A. Raju A. K. Twinkle S. Sreenath K. R. Zacharia P. U. et al . (2019). Predatory association of Aeolidiopsis sp. on Palythoa mutuki (Haddon and Shackleton, 1891) along Gujarat coast, India. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India61, 106–109. doi: 10.6024/jmbai.2019.61.1.2100-16

77

Steen R. G. Muscatine L. (1984). Daily budgets of photosynthetically fixed carbon in symbiotic zoanthids. Biol. Bull.167, 477–487. doi: 10.2307/1541292

78

Stuart C. E. Pittman S. J. Stamoulis K. A. Benkwitt C. E. Epstein H. E. Graham N. A. et al . (2025). Seascape configuration determines spatial patterns of seabird-vectored nutrient enrichment to coral reefs. Ecography10, e07863. doi: 10.1002/ecog.07863

79

Tahsin K. T. Sangmanee N. Chamchoy C. Phoaduang S. Yeemin T. Winijkul E. (2023). “ Coral Feeding Behavior on Microplastics,” in Microplastic Occurrence, Fate, Impact, and Remediation. Environmental Chemistry for a Sustainable World, vol. 73 . Eds. WangC.BabelS.LichtfouseE. ( Springer, Cham). doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-36351-1_3

80

Wegner A. Besseling E. Foekema E. M. Kamermans P. Koelmans A. A. (2012). Effects of nanopolystyrene on the feeding behavior of the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis L.). Environ. Toxicol. Chem.31, 2490–2497. doi: 10.1002/etc.1984

81

Wright L. S. Napper I. E. Thompson R. C. (2021). Potential microplastic release from beached fishing gear in Great Britain's region of highest fishing litter density. Mar. pollut. Bull.173, 112949. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.113115

82

Yeemin T. Sangiamdee D. Musig W. Awakairt S. Rangseethampanya P. Rongprakhon S. (2018). Microplastics in the digestive tracts of reef fish in the Eastern Gulf of Thailand. Ramkhamhaeng Int. J. Sci. Technol.1, 9–14.

83

Yeemin T. Sutthacheep M. Pengsakun S. Klinthong W. Chamchoy C. Suebpala W. (2024). Quantifying blue carbon stocks in interconnected seagrass, coral reef, and sandy coastline ecosystems in the Western Gulf of Thailand. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1297286

84

Yuan M. H. Lin K. T. Pan S. Y. Yang C. K. (2024). Exploring coral reef benefits: a systematic SEEA-driven review. Sci. Total Environ.950, 175237. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175237

85

Zhang W. Ok Y. S. Bank M. S. Sonne C. (2023). Macro- and microplastics as complex threats to coral reef ecosystems. Environ. Int.174, 107914. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2023.107914

86

Zhao X. Yu S. Fan M. (2024). Degradation of coral reef ecosystems: mathematical-dynamical modeling approach. Europhysics Lett.148, 32001. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/ad89f6

Summary

Keywords

coral reef ecosystem, microplastic pollution, polymer identification, spatial variability, zoanthid

Citation

Yeemin T, Chamchoy C, Klinthong W, Pengsakun S, Banleng W, Phutthaphibankun C, Karnpakob P, Suebpala W and Sutthacheep M (2025) First assessment of microplastic accumulation and characteristics in the zoanthid Palythoa caesia across coral reef ecosystems in Thailand. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1670359. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1670359

Received

21 July 2025

Revised

01 November 2025

Accepted

05 November 2025

Published

09 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Jessica Reichert, University of Hawaii at Manoa, United States

Reviewed by

Suchai Worachananant, Kasetsart University, Thailand

Ahmad Faizal, Universitas Hasanuddin, Indonesia

Marvin Rades, University of Giessen, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yeemin, Chamchoy, Klinthong, Pengsakun, Banleng, Phutthaphibankun, Karnpakob, Suebpala and Sutthacheep.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Makamas Sutthacheep, smakamas@hotmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.