Abstract

Understanding the status and trends of Essential Ocean Variables (EOV) and Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBV) is crucial for informing policy-makers and the public about sustainable management of marine biodiversity. Marine image data hold significant potential in this context, offering a permanent, information-rich and non-extractive record of marine environments at the time of capture. Quantitative image-based measurements such as species abundance and distribution have proven to be highly effective for engaging diverse stakeholders. The exchange and reuse by experienced fisheries scientists and marine ecologists of nine image-based datasets (including images, metadata and annotations) collected through various protocols revealed a substantial disconnect between initial expectations and actual practical usability, particularly in terms of understanding and reusing data. Two key issues were highlighted. First, the link between the datasets and their potential applications in deriving EOV/EBV was often inadequately described or absent. Second, despite both initial and ongoing efforts to document the data, new users continued to face challenges in understanding underlying properties and contextual features of datasets. We suggest these findings are likely to characterize many, if not most, historical image-based datasets. While standards promoting the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) for image-based data are emerging, our focus here is on the specific features of documentation that enable or facilitate reuse of data for the purpose of deriving EOV/EBV. From this perspective, we provide a set of recommendations for documenting both images and their associated annotations, aimed at supporting broader applications of in situ image data in marine conservation and ecology.

1 Introduction

Strong declines in the condition of marine ecosystems and biodiversity stem from human activities, both indirectly in relation to climate change, and directly through well-identified pressures including farming, deforestation, overexploitation of resources and coastal development (Halpern et al., 2008; Froese et al., 2018; IPBES, 2019). Management and policy responses to these declines are informed by monitoring the status and trend in the condition of oceans and marine life. Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBV) and Essential Ocean Variables (EOV) (Supplementary Material 1) are two distinct and complementary, internationally agreed frameworks to facilitate consistent approaches to environmental monitoring and subsequent reporting to international conventions and initiatives (Convention on Biological Diversity, United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, International Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services). Here, we refer to EBV and EOV collectively as Essential Variables (EV) although they pertain to different user needs. EV are relevant for assessing questions at various scales, ranging from Marine Protected Area (MPA) effectiveness and local impact of anthropogenic activities, to national-level State of the Environment reporting (e.g. https://soe.dcceew.gov.au/). The production of EV relies on monitoring programs that should be globally coordinated (Navarro et al., 2017; Gonzalez et al., 2023) to guide action to meet the targets of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022).

Underwater image-based data are information-rich, time-stamped records of marine biodiversity, usually with spatial provenance, and have become a major source of in situ observations (Mallet and Pelletier, 2014; Durden et al., 2016). Image-based data play a growing role for monitoring EV such as habitat cover, taxonomic composition, abundance, body size and condition, in various marine ecosystems, from shallow coastal to deep sea environments. Imagery offers several attractive characteristics. Firstly, non-extractive collection is well-suited to surveying sensitive habitats and monitoring change over time (Seiler, 2013). Secondly, it provides quantitative estimates of abundance, and may reduce uncertainties due to observational selectivity, compared to physical samplers such as nets (Williams et al., 2015; Langlois et al., 2020; Hanafi-Portier et al., 2021; Pelletier et al., 2021). Thirdly, the spatial scales of image data align with management needs [e.g. to identify Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems (Baco et al., 2023)] and allow building scalable biodiversity distribution models (Rowden et al., 2017; Pelletier et al., 2020). Fourthly, physical habitat variables (e.g. seabed geomorphology) and biodiversity data are collected simultaneously and at the same scales (Marcillat et al., 2024). Fifthly, imagery has the potential to provide temporally replicated data on biodiversity (Saulnier et al., 2025). Last but not least, it is a powerful tool for outreach, stakeholder engagement and facilitating communication with policy-makers and environmental managers (Pelletier, 2020).

These characteristics emphasize the strong potential for image-based EV to monitor benthic biodiversity from local to large scales, and their high relevance for data sharing and reuse. Images are well suited to reuse because they represent an unequivocal snapshot-in-time that can be revisited to address various science questions. However, achieving consistency and scalability of in situ observations remains challenging, particularly when compared to data collection methods like remote-sensing imagery. Coordinated efforts are thus needed to generate consistent and representative observations across biotopes and regions, and to ensure that protocols enable integration across depth gradients, habitat types, and ecosystems. Such efforts are aligned with the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) principles (Wilkinson et al., 2016) that seek to enable reuse, compare and combine data (in general) and, for biodiversity data, by developing standards and nomenclatures (Wieczorek et al., 2012), and guidelines for the routine generation of EBV products (Hardisty et al., 2019). Nonetheless, data sharing remains hindered by a lack of incentive and institutional support and the absence of generally applicable “best practices” (Mandeville et al., 2021). For image-based data and derived data products, detailed operating procedures and metadata are required at each step of data generation. The lack of common references, shared standards, vocabularies, and broadly agreed guidelines for data management is currently being addressed by the marine imaging community, to make image data FAIR (Schoening et al. (2022), https://www.marine-imaging.com, https://challenger150.world). Schoening et al. (2022) introduced metadata standards for image acquisition and some aspects of biological data capture through the concept of image FAIR Digital Objects (iFDO). Complementary to iFDO, Durden et al. (2024) presented a set of attributes for documenting the pool of organisms from which imagery is collected (‘target populations’).

To provide a complementary hands-on perspective, this article examines a selection of image-based datasets representative of widely-used benthic imagery protocols, and evaluates their potential reuse for producing EV. An initial screening was conducted to assess how well the content of each dataset could be understood for the purpose of deriving EV. Selected datasets were then exchanged among scientists to attempt practical reuse. This exercise supported a reflective discussion on the challenges and enablers of understanding and reusing historical image-based datasets.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Datasets

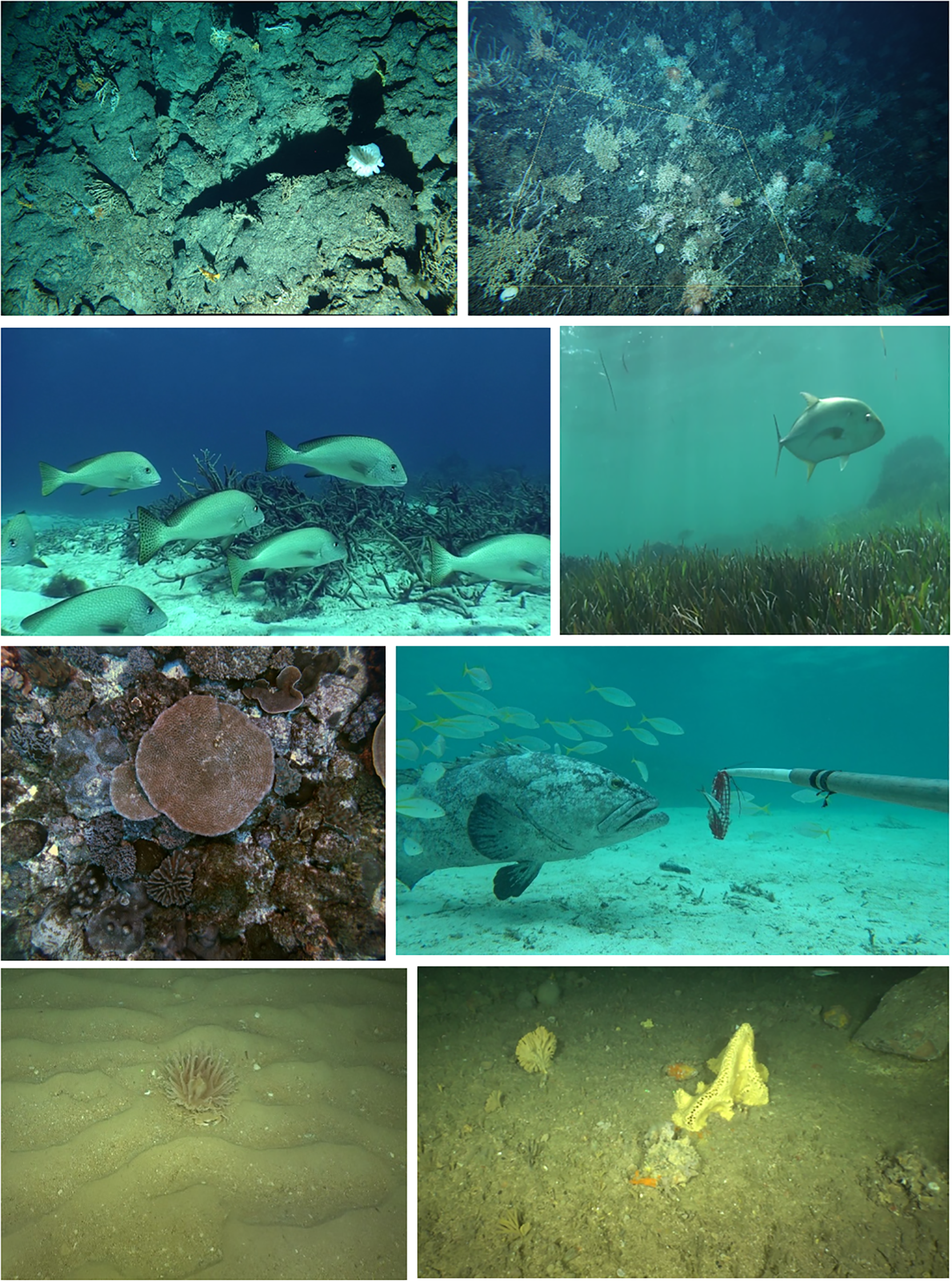

Nine image-based biodiversity datasets collected by 16 science providers in France and Australia with extensive experience in the Acquisition, Annotation, Administration and Application of marine imagery (the “QuatreA” group, Supplementary Material 2), were shared within the group. The datasets pertained to demersal fish, benthic sessile invertebrates and benthic habitats in temperate and tropical, and deep and shallow ecosystems (Figures 1, 2, Table 1). They resulted from a range of protocols generally applied for monitoring benthic and demersal macrofauna [i.e. size of the order of a cm, Cochran et al. (2019)], megafauna [i.e. maximum body mass > 45kg, Estes et al. (2016)], as well as sea weeds and seagrasses (derived EV in Supplementary Material 1). Two datasets were collected in deep volcanic habitats (D1, D2), five in shallow coral reef ecosystems (D3-D7) and two on soft bottom temperate shelves (D8-D9). Sampling platforms and, image types and annotation features were respectively described in Supplementary Materials 3, 4. For each protocol, specific annotation schemes have been defined (Althaus et al., 2015; Przeslawski et al., 2019; Hanafi-Portier et al., 2021; Pelletier et al., 2021; Untiedt et al., 2021).

Figure 1

Location of the datasets included in the study. Datasets were identified in Table 1, sampling platforms in Supplementary Material 3. Background : ESRI World Imagery [Satellite Imagery]. Visualized in QGIS 3.4. ESRI. https://www.arcgis.com

Figure 2

Example images with targeted EV: 1st row: D1 (Benthic invertebrate abundance and distribution) and D2 (Hard coral cover and composition); 2nd row: D3 (Fish abundance and distribution) and D4 (Biotic cover and composition); 3rd row: D5 (Biotic cover and composition) and D6 (Fish abundance and distribution); 4th row: D8 and D9 (Benthic invertebrate abundance and distribution).

Table 1

| Dataset | Ecosystem | Location & year | Sampling type/platform | Target EOVs | Type of image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | Deep volcanic habitats | Mozambique Channel (Indian Ocean), 2017 | Transects - Towed Camera System (SCAMPI) | Benthic habitats & communities | still images |

| D2 | Tasmania (SW Pacific), 2018 |

Transects - Towed camera system (MRTIC) | Benthic habitats & communities | video & stereo still images | |

| D3 | Shallow coral reefs | Coral Sea Region (SW Pacific), 2015 |

Lander - Rotating video station (STAVIRO) | Fishes | video |

| D4 | Benthic habitats | video | |||

| D5 | Coral Sea Region (SW Pacific), 2020 |

Transects - Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) | Benthic habitats & communities | still images | |

| D6 | Lander - Baited Remote Underwater stereo Video (Stereo BRUV) | Fishes | video | ||

| D7 | Benthic habitats | video | |||

| D8 | Continental shelf | Bay of Biscay and Celtic Sea, 2020 | Transects - Towed sledge (PAGURE) | Benthic habitats & communities | video |

| D9 | Gulf of Lion, Mediterranean 2019 | Benthic habitats & communities | video |

General information about the nine datasets considered.

Images were generated either by fixed observation systems set on the sea bottom (landers) or as transects from mobile platforms (towed camera or AUV); sampling platforms are fully described in Supplementary Material 3. Locations of datasets in Figure 1.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Data exchange

Data exchange was organized during a workshop of the QuatreA group in 2021, via shared repositories where the datasets were uploaded. A dataset comprised image samples, metadata, annotations, EV products derived from annotations, and any documentation or report that the data producer deemed necessary for understanding the files in the dataset.

2.2.2 Understanding datasets: an expert evaluation

Evaluation aimed to appraise the level of understanding of a given dataset’s content and its potential for EV production. For this purpose, a questionnaire was iteratively devised. It relied on close-ended multiple choice questions, complemented by free text fields to provide additional context or insights (Supplementary Material 5). The questionnaire comprised five sections: background information on the dataset and the data files, file format, file content, information about EV, and overall assessment of the understanding of the dataset.

Each dataset was screened by most of the respondents, with one questionnaire per dataset and respondent. The responses were not statistically analyzed, as the sample size was small, and the number of completed questionnaires was not fully balanced across respondents. Rather, we examined and synthesized the responses to demonstrate patterns and characteristics of the datasets and identified the main concerns with respect to the questions addressed. For any given dataset, responses could differ slightly between respondents, illustrating differences in perceptions.

2.2.3 Re-using datasets for EV computation

Two pairs of datasets were selected to evaluate data reusability by calculating EV-related metrics (the most similar ecosystems were paired to minimize variability): 1) datasets D1 and D2 from deep volcanic habitats; and 2) datasets D4 and D7 from coastal habitats (details in Supplementary Materials 6, 7). Within each pair, data producers were required to reuse the other’s dataset, i.e. to prepare data and compute EV metrics solely based on the information provided. This hands-on exercise was aimed at i) detecting any information gaps in the dataset, and ii) supporting recommendations for a more effective sharing of data (see discussion). To assess reusability, we only examined the characteristics of the EV metrics resulting from each protocol, without comparing them from an ecological perspective. Two families of metrics commonly derived from benthic imagery were considered: diversity metrics (Magurran, 2004; Clarke and Gorley, 2006) and abundance metrics. For benthic fauna, the latter included invertebrate densities in ind.m-2, while for fishes, both the abundance and biomass of large fish were considered (Table 2).

Table 2

| EOV | EBV | Metric | Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benthic invertebrate abundance and distribution, hard coral cover and composition | Species abundance, species distribution | Invertebrate density: no. individuals per m2 (ind.m-2) in a given area: • D1: calculated from a set of images within along-transect polygons of 200 m2 • D2: calculated from a measured quadrat generated using stereo images |

0.96 ind/m2 2.75 ind/m2 |

| Taxonomic diversity | • Margalef diversity species richness (d) • Shannon diversity (H’) • Simpson’s diversity (1-Lambda) |

8.76 (D1) & 3.83 (D2) 2.02 (D1) & 2.32 (D2) 0.76 (D1) & 0.86 (D2) |

|

| Fish abundance and distribution | Species abundance, species distribution | Index of abundance for large fishes: • D4: Mean no. fishes classified as large (relative to their species) taken over the 3 rotations of observation unit, scaled to area of view • D7: Maximum no. fish > 20 cm taken over all frames of the observation unit • D7: Biomass of large fish (>20 cm) |

5.30 ind/100m2 26.45 ind/frame 13.872 kg/frame |

| Taxonomic diversity | Species richness per observation unit: • D4: No. of species within the area of view (here 10m), taken over the 3 rotations of observation unit, and scaled to 100 m2 (nb. of species/100m2) • D7: No. of species in the frame with maximum abundance |

14.31 species/100m2 16.94 species/frame |

Metrics computed in relation to EOV and EBV.

Estimates were computed from the datasets exchanged. Note the differences in units among datasets for any given metric. nb. = number.

Sample-based rarefaction curves for species richness were obtained from the iNEXT() function, using the iNEXT package in R (Chao et al., 2014; Hsieh et al., 2016). Taxonomic richness was estimated based on taxa occurrences (presence/absence), using Hills number with the order q = 0, corresponding to species richness. Calculations were performed with 999 permutations, richness was extrapolated up to twice the reference sample size (e.g. 1800 images extrapolated from the 899 images in D1 dataset). Rarefaction of the taxonomic richness was calculated for the minimum sample size (i.e., 305 quadrats in D2). Note that, in image-based data, the level of identification (species, genus, family, other) may vary within a given dataset because the ability to identify taxonomic features is variable; here we thus refer to taxonomic richness (instead of species richness), considering this varying level of taxa identification. Plots were produced using the ggplot2 package (Wickham, 2016) in the R environment (version 4.1.0) (R Core Team, 2021).

3 Results

3.1 Understanding the datasets

Six datasets were evaluated by eight respondents, two by seven respondents and one by five respondents. The average time taken to understand and evaluate a dataset was 15 minutes, and the maximum time was 180 minutes.

3.1.1 Respondents’ characteristics

All respondents were either advanced or expert in ecology and/or fisheries science, and in data acquisition (Table 6.1 in Supplementary Material 6). They formed a mix of marine ecologists and fisheries scientists highly skilled in data acquisition, more or less involved in data science and management, and including both junior and senior scientists.

3.1.2 General information about the dataset

This contextual information (purpose, nature of the dataset, region and ecosystem where the data were collected, among others) is key for potential reusers, but varied greatly between datasets and was absent for two datasets. For seven out of nine datasets, it consisted of a large report or publication, which was assessed to be essential to understand the dataset but scored between very easy (four datasets), easy (two datasets) and not easy (one) to understand. The survey purpose and the ecosystems sampled were clearly identified for all datasets but one, and survey features (sampling platform, sampling design, location, timing, depth range) were well documented. Key information about camera specifications, e.g. field of view, and orientation was occasionally missing. Likewise, the processing and subsampling of images for annotation were often not fully described. While the lead organization was unambiguous, custody and user license remained mostly obscure, including because it may not be the same for image data, annotation data and EV products. End-users of data were identified for six datasets. However, target EV were only explicitly stated for four datasets, while for five datasets, they were not mentioned or ambiguously so.

3.1.3 Understanding the data files

The files containing sampling metadata were all machine-readable for all datasets but one, where the file was under a proprietary format, not accessible using open source software. In several instances, metadata were repeated in the annotation file, leading to tables with too many columns. For two datasets, the annotation file also included EV values. For three datasets only, EV metrics were provided in a separate file. Comprehending the data files was assessed against the use of clear headers, adherence to standards and controlled vocabularies, and consistency of content. Production of metadata and annotation files was documented for all datasets but one (Table 6.3 in Supplementary Material 6); seven used a standard annotation scheme based on a methodological guide. The language used was consistent and fields were mostly well defined in five datasets, but overall, controlled and standard vocabularies were not used. These results suggested that despite data providers having done their best to provide the files (e.g. by indicating how each data file was produced), there were still areas of improvement regarding field definition, consistent language use, and controlled and standard vocabularies.

3.1.4 Information about EV

For the three datasets with separate EV files, field headers were correctly defined and controlled and standard vocabularies were used. Language use was consistent but for one dataset. For the six datasets that reported EV (even when they were not in a separate file), the presented EV were found to be conceptually similar to metrics that could be computed from other datasets in general. There was a consensus among respondents for three datasets, while, for the other three datasets, responses were more mixed with some non-responses or poorer scores. Lastly, for some datasets, images were provided to explain the annotation scheme, but derived EV were rarely illustrated from images.

3.1.5 Potential of the dataset for producing additional EV

Generally, the description of the annotation procedure was not sufficient to identify whether EV could be calculated from the data, including due to limitations in the data acquisition method and/or the annotation scheme. For instance, observations by cameras with a narrow field of view or from a moving platform may prevent accurate observations of large and mobile taxa, whereas panoramic video may not detect small taxa.

3.1.6 Overall understanding of the dataset

There was some variation among respondents on this aspect, but six datasets were scored as either “good” or “complete”, one “intermediate”, and two datasets were scored “difficult”. Interestingly, when experts evaluated their own datasets, they rarely gave the highest score. This suggests that, despite their careful preparation for data exchange, the exercise revealed the need for additional information. Free text comments highlighted several barriers to understanding: i) too many files to decipher; ii) a lack of overarching guidance; iii) gaps in metadata information; and (iv) redundant information across files, which generates confusion about which information should be used.

3.2 Reusing the datasets

3.2.1 Invertebrates in deep volcanic habitats

Datasets D1 and D2 were successfully analyzed by new users: no information gaps were identified in the dataset descriptions, and diversity metrics, rarefaction curves and invertebrate abundances (densities) were computed from each dataset (Supplementary Material 7). Back-transforming data to unstandardized abundance counts was necessary to compute Margalef and Simpson indices because the data provided were standardized densities (Supplementary Material 4). Also, it was necessary to rescale counts by the averaged sampling area per image for rarefaction curves because the average area annotated on a given image differed between the datasets. For mean abundance densities, standard deviations reflected sampling and annotation efforts, i.e. the number of images sampled and the number of images annotated (Supplementary Material 7).

Despite D1 and D2 being obtained from relatively similar protocols (towed video with periodic sampling of still images), the annotation strategies and observation granularity of the two datasets differed. First, the list of annotated invertebrate taxa differed between D1 and D2, with D2 being restricted to VME taxa (stony, soft and black corals, sponges, crinoids, seapens and brisingids) and not considering other major taxa (crustacea, holothurians, ophiuroids and asteroids) that had been annotated in D1 (Supplementary Material 4, 7). Filtering data corresponding to overlapping fractions of the invertebrate fauna would potentially remove this lack of taxonomic consistency. But there were also large differences in the taxonomic granularity of invertebrate Phyla between datasets, for example, granularity was high for corals in D2 (52 phototaxa retained, Supplementary Material 7), whereas it was coarser (at the order level) in D1. Similarly, sponges were differentiated at Phylum level in D2 and at Class level in D1, directly reflecting the relatively poor knowledge of sponges in both regions, and the lack of taxonomic expertise to guide consistent identification at a higher taxonomic granularity.

3.2.2 Fishes in coastal habitats

Datasets D4 and D7 were also successfully analyzed by new users. No major information gaps were identified in the dataset descriptions. Diversity metrics, rarefaction curves and fish abundance indices could be computed from each dataset (Supplementary Material 7). Both datasets were generated from video recorded by a lander, but differed in mode of image capture, duration of observation and sampled area. More precisely, the D4 lander (STAVIRO) recorded for 9 minutes compared to 1 hour for the D7 lander (stereo BRUV). The sampled area (volume) can be estimated in D4 because the STAVIRO depth-of-view is roughly calibrated, but it is not known in D7 because the BRUV lander is baited and the range of attraction to the bait plume is not measured. Regarding annotation, fishes are counted over an entire video of 9 minutes (D4) vs from maximum number of individuals (MaxN) in a single frame over the full deployment (D7).

Compared to deep benthic invertebrates, a higher proportion of fishes can be expected to be identified consistently from any regional species pool, because fish taxonomy is more mature, external diagnostic characters for species are typically more recognizable, and many high-quality identification guides exist. However, both D4 and D7 annotation protocols have specifics that relate to the image capture process. For D4, because fishes are counted up to a 5 m radius, the species reference list needs to exclude small species that may be missed, and species complexes were defined for species that are difficult to distinguish on images (Supplementary Material 7). In contrast, for D7, fishes are closer to the camera because they are gathering around the bait meaning that small species are consistently detected. Also, fishes from an unknown or ambiguous family were counted in D7 but not in D4.

4 Discussion

This exchange and reuse of datasets had two main objectives: firstly to assess the level of understanding of datasets, and secondly to determine what is required for a marine scientist to effectively reuse unfamiliar data and to identify which EV metrics could be derived from them.

Our ‘hands-on’ experiment identified several challenges in understanding each dataset - challenges that become even more pronounced when attempting to manipulate the data and compute EV metrics. Despite the reused datasets being considered relatively easy to understand during the evaluation phase, evaluating and reusing them still demanded significant time, effort and communication. This highlights even greater resource requirements when datasets are reused by non-experts or when documentation is limited.

4.1 The main challenge for understanding and reusing data: inadequate documentation

We identified that information needed to understand and reuse unfamiliar datasets was missing in each stage of the workflow. For image acquisition, this variously included post-survey reporting, detail on sampling design, e.g. a map indicating the spatial extent and distribution of sampling effort and depth range (for guidance, see §4.2).

Similarly, the documented detail for image annotation methods was highly variable, but there was typically insufficient information on annotation method, guides to taxa including reference list of target taxa and rationale for inclusions/exclusions, definition of annotation classes, and reference image examples to re-use data. This extended to EV production, where EV metrics were often not made explicit, and there was no precise definition of how they were computed from annotations. Two notable information gaps were identified regarding annotation schemes. First, the exact list of annotated taxa must be clearly provided, preferably as an explicit list, along with the criteria used for selecting those taxa. It is also recommended that a reference guide, such as identification keys (e.g. Hanafi-Portier et al., 2021) or reference to image catalogs like SMarTaR-ID (Howell et al., 2020) and CATAMI (Althaus et al., 2015), are included to provide exemplar images. Second, the documentation must precisely describe the subsampling of images, including rationale and methods used. Regarding EV production, recommendations are given below (§ 4.4).

4.2 How to improve the understanding of image-based data to support the production of Essential Variables?

The iFDO format considers all metadata needed to identify and access images from capture to curation, accessibility and use rights, and includes the study objective. The framework proposed by Durden et al. (2024), builds from iFDO and documents both biological scope and imaging approach for an image dataset using the Ecological Metadata Language (EML) Jones et al. (2019), which captures much of the information outlined above (§ 4.1), but detailed information on sampling design, annotation methods and derived EV is not provided. Additionally, regarding sampling design, statistical considerations based on the research questions addressed by the dataset should be made explicit (Foster et al., 2020).

4.2.1 A concise, self-explanatory, and user-friendly summary of the dataset is needed

In this study, several of the datasets were difficult to understand without consulting the data files directly or referring to external sources. This issue typically occurred when no descriptive document was attached, or when general information was buried within lengthy or partly unrelated documents such as scientific articles, short survey reports or long reports covering multiple data collections. While providing URLs is essential, navigating repositories often requires additional guidance and effort.

Key information to support data reuse should be readily grasped through a visual (e.g. a map) and concise summary (such as a ‘readme’ type of file), along with direct access to the relevant data files, so that new users can quickly assess whether the data suit their needs. It should explicitly state the target EV and intended end-users, as these are central for identifying reuse potential (see our suggested template, Supplementary Material 8). The EOV specification sheets developed by GOOS (2025) offer guidance on how to best measure EOV which could inspire this document. Such an abstract is already provided in repositories like GBIF (2025) and OBIS (2025) (the latter using EML too), although not referring explicitly to EV.

4.2.2 Provide example images

A key advantage of image-based data is its potential to visually support users in understanding the dataset and its associated files. In some cases, images were provided to explain the annotation scheme, but EV were rarely illustrated through images. A more systematic use of images to describe datasets would enhance interpretability. Providing direct access to collected images not only improves transparency but also fosters creativity and innovation, as images may be repurposed for non-anticipated uses. Reuse and dissemination of historical scientific image data can help combat the shifting baseline syndrome by promoting the use of visual evidence in management and conservation efforts (Soga and Gaston, 2018).

4.2.3 Browsing the data files and understanding their content should be easier

Understanding and manipulating data to compute EV was challenging, particularly when descriptions of image subsampling, features of annotation schemes, and details about the computation of EV metrics were insufficient. Besides, redundant information or overlapping information across multiple files created confusion. To improve clarity and usability, datasets should be organized into distinct files (field metadata, annotation metadata, annotations and EV metrics) with minimal redundancy, and complemented by a clear workflow showing how the files are related and derived from one another. Consistently with Schoening et al. (2022), additional recommendations include: i) ensuring files are machine readable using open source software; ii) providing concise descriptions of each file’s content with clearly defined headers, data custody and usage license, and iii) using controlled vocabulary, even if not standardized, along with a dictionary to explain terms.

4.2.4 Simple improvements will facilitate the application of standards

For annotation files, providing explicit field definition is easily achieved by including a side table or document alongside the data file. Similarly, ensuring consistent language use requires only basic semantic alignment and verification, even when multiple languages are inherent to the dataset, as was the case here. Although vocabularies were not fully standardized, most protocols were mature and broadly used. The marine science imaging community has been actively addressing these issues in collaboration with repository services, e.g. ODATIS (2025) and UMI (2025). The broader adoption of standards is expected to follow as a more comprehensive array of protocols becomes operationalized.

4.2.5 Assisting data producers in documenting their datasets for publication

Currently many data producers receive limited support for documenting the data they have collected. For instance, terms such as custody and use license were unfamiliar to several data producers in this study, highlighting the need for guidance on how these standard terms translate to specific components of an imagery dataset. Such guidance is e.g. occurring in the Marine Imaging community (Borremans et al., 2024). Implementing good documentation practices requires practical assistance e.g. through user-friendly operating procedures (see e.g. the Standard Operating Procedure for image curation and publication developed by Schoening (2021)). This is important not only for future datasets, but also to safeguard and disseminate existing datasets, ensuring their long-term value and use in times of rapid changes in biodiversity.

4.2.6 Implications of machine learning for data reuse

Machine learning (ML) methods can automate the detection and classification of biota in images and process large volumes of data enhancing the generation and sharing of image-based data. The datasets considered in this study were not annotated using ML. However, this will be the norm in the future; annotation data and associated metadata should thus be carefully documented. The iFDO standard includes a provision to document image-level metadata such as annotation labels, localization coordinates and annotator identifiers. This metadata standard enables the distinction between human-produced and machine-generated annotations, and helps standardize the process of image annotation amid future ML advancements. Being able to reuse ML-derived annotations is contingent upon documenting machine learning pipelines, models, and resulting datasets (Samuel et al., 2021; Folorunso et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2022). This could encompass: i) comprehensive metadata describing the model such as architecture and size, the training configuration including the learning rate, loss function, optimizer and regularization methods, and ii) dataset attributes such as relevant preprocessing steps, data normalization, and augmentation techniques. The final models are often tightly coupled with the specific datasets on which they are trained, potentially restricting the reuse of a model to a particular data class or distribution, thereby influencing the reusability of the model.

Several initiatives are actively addressing these challenges in marine and broader environmental contexts. Dedicated marine imaging platforms including Squidle+ and BIIGLE enable collaborative annotation workflows for underwater imagery analysis, while FathomNet serves as a curated repository of marine imagery designed for machine learning model development (Langenkämper et al., 2017; Katija et al., 2022; Squidle+, 2025). Organizations including Earth Science Information Partners (ESIP), Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC), and Radiant Earth Foundation are developing standards for ML-ready environmental datasets (Alemohammad et al., 2020; ESIP Data Readiness Cluster, 2022), with OGC having established the Training Data Markup Language for Artificial Intelligence (TrainingDML-AI) standard for geospatial training data (Yue et al., 2023).

4.3 Main issues preventing the comparison of EV obtained from distinct protocols

4.3.1 Image capture process

For mobile animals, deployment scheme and image capture features determine species-dependent observation probabilities, which strongly influences the observation of fishes. Hence, abundance and diversity metrics differ between baited and unbaited platforms because the species-specific influence of bait, and extent of bait plume, are unknown. In addition, differences in both duration and area of observation preclude comparing counts. For benthic habitats, including sessile fauna, subsampling of images, the area of image corresponding to the annotations, and the difference between percent cover metrics and individual counts hinder the potential for metric’s comparability. For both fishes and benthic habitats, taxonomic richness strongly depends on sampling effort (duration and observation area/volume), while image resolution, camera orientation and speed, and illumination also determine different taxonomic identification levels and the lower size limit of visible organisms.

4.3.2 Subsampling for annotation

Image subsampling determines the effective sampled area and/or sample duration, and this may be standardized by rescaling with respect to time and/or spatial support. In our study, and more generally, it is relatively easy for abundance estimation, but potentially more difficult for diversity metrics and rarefaction curves that are based on counts of corresponding taxa, ideally species.

4.3.3 Taxa reference lists for annotation

An explicit list of annotated taxa is essential to understand data and derived metrics, and enable comparisons between distinct protocols. Furthermore, because reference lists inevitably differ across ecosystems, explicit criteria for building the list are desirable. Annotation levels frequently differ across protocols, either because the field of view constrains the objects that can be observed depending on their size (e.g. for fishes), or because the taxonomic granularity may differ depending on the ability to identify faunal units from images. In addition, and this particularly applies to coastal areas, this identification level varies according to visibility and light. Hence, many organisms cannot be identified at species level, particularly when taxonomies are poorly known (e.g. some deep-sea invertebrate taxa) or when discriminating criteria not visible on images (e.g. cnidarians, sponges, ophiurids,…). These effects are somehow mitigated through annotation schemes that anticipate the image resolution at which diagnostic features can be consistently identified, and prefer assigning higher taxonomic levels where diagnostic characters are lacking.

For all these reasons, resulting EV metrics are usually not comparable across protocols. Intercalibration experiments conducted on the field would be the appropriate option to be able to compare, aggregate or pool EV values across protocols, but such experiments are too rarely envisaged [e.g. Mallet et al. (2014)]. Also, some metrics may prove more robust to comparison and aggregation than others, depending e.g. on the taxa, on the variable behind the metric (occurrence, abundance, diversity), or on the spatio-temporal support of the EV metric. In any case, the proper documentation of datasets will enable a sound reuse of data, avoid mixing incompatible data and sometimes allow the use of several datasets together while taking into account all precautions of use.

4.4 Recommendations for reusing benthic image-based data for EOV and EBV production

To facilitate the production of ecological metrics, the globally accepted EV frameworks should be used. Minimum information standards for EBVs were developed within GEOBON (Fernandez, 2018) and linkage with EOV and monitoring programs is also embraced by the Marine Biodiversity observation Network.1

Reusing existing EV products requires to know how metrics were computed from annotations, and how they relate to the corresponding EV. For clarity, EV should be organized as stand-alone metrics’ files, distinct from annotations. Reusing existing annotations for computing new EV requires to know exactly what can or cannot be done with the data, and specify any other “precaution before reuse”. Hence, the EV that can be computed reliably from the data should be listed, as well as how they should be computed from the annotations. Reusing images for new annotation requires to know precisely the image capture process and any related information. In all cases, understanding and reusing image-based data requires proper documentation of datasets by the scientific communities that collect and use the data. To foster sound reuse, the document must clearly state the taxonomic resolution and the fraction of the ecosystem reliably observed.

Our experience also illustrates that the use of standards for underwater benthic image-based data should be a priority. Several collaborative initiatives have embraced this challenge, but they rely on the willingness of scientists and institutional support is often poor. Based on our experience and exchanges with the marine imaging community (Pelletier et al., 2025), we identify a strong and urgent need for better support to enable public dissemination of all data and facilitate their reuse, especially for supporting biodiversity conservation policies.

Statements

Data availability statement

For D1, survey report and dive metadata are published on https://campagnes.flotteoceanographique.fr (Corbari et al., 2017) and annotations are published on https://www.seanoe.org (Hanafi-Portier et al., 2023). D2 data are published as part of CSIRO Data collection (Untiedt et al., 2023). D3 and D4 are published on seanoe.org (Pelletier et al., 2023). D5, D6 and D7 can be retrieved on the Institute of Marine Science (University of Tasmania) repository (Monk et al., 2023). D8 and D9 are published on seanoe.org (Vaz et al., 2023). The questionnaire and the codes devised for this study are available at https://github.com/QuatreA under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Animal Ethics Committee, University of Tasmania AMBIO Steering Committee, Government, Provinces and Conservatory of Wildlife Areas of New Caledonia. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

DP: Validation, Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis. JM: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Software. FA: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Validation, Visualization, Data curation, Conceptualization. CB: Software, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Validation. MH-P: Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Validation. BS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis. KO: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. CU: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Data curation. CJ: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. NB: Validation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation. PL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. SV: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation. EH: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AW: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the French Institute for the Exploitation of the Sea (Ifremer), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the University of Tasmania. Additional funding was provided by the FASIC Program of CampusFrance under project n°46032PE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the numerous people who contributed to the collection and annotation of the datasets evaluated in the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1676232/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1

Alemohammad H. Maskey M. Estes L. Gentine P. Lunga D. Yi Z. (2020). Advancing application of machine learning tools for NASA’s earth observation data (Washington D.C: NASA). Available online at: https://www.grss-ieee.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/NASA_ML_Workshop_Report_jan2020.pdf (Accessed September 24, 2025).

2

Althaus F. Hill N. Ferrari R. Edwards L. Przeslawski R. Schönberg C. H. L. et al . (2015). A standardised vocabulary for identifying benthic biota and substrata from underwater imagery: the CATAMI classification scheme. PloS One10, e0141039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141039

3

Baco A. R. Ross R. Althaus F. Amon D. Bridges A. E. H. Brix S. et al . (2023). Towards a scientific community consensus on designating Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems from imagery. PeerJ11, e16024. doi: 10.7717/peerj.16024

4

Borremans C. Durden J. M. Schoening T. Curtis E. J. Adams L. A. Branzan Albu A. et al . (2024). Report on the marine imaging workshop 2022. RIO10, e119782. doi: 10.3897/rio.10.e119782

5

Chao A. Gotelli N. J. Hsieh T. C. Sander E. L. Ma K. H. Colwell R. K. et al . (2014). Rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers: a framework for sampling and estimation in species diversity studies. Ecol. Monogr.84, 45–67. doi: 10.1890/13-0133.1

6

Clarke K. R. Gorley R. N. (2006). PRIMER v6: User Manual/Tutorial (Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research) (Plymouth: PRIMER-E).

7

Cochran J. K. Bokuniewicz H. J. Yager P. L. (2019). “ Marine Life,” in Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences ( Academic Press, New York).

8

Convention on Biological Diversity (2022). Post-2020 global biodiversity framework. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/409e/19ae/369752b245f05e88f760aeb3/wg2020-05-l-02-en.pdf (Accessed September 25, 2023).

9

Corbari L. Samadi S. Olu K. (2017). BIOMAGLO cruise RV Antea. doi: 10.17600/17004000

10

Durden J. Schoening T. Althaus F. Friedman A. Garcia R. Glover A. et al . (2016). “ Perspectives in visual imaging for marine biology and ecology:from acquisition to understanding. Oceanography and marine biology, 1–72.

11

Durden J. M. Schoening T. Curtis E. J. Downie A. Gates A. R. Jones D. O. B. et al . (2024). Defining the target population to make marine image-based biological data FAIR. Ecol. Inf.80, 102526. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102526

12

ESIP Data Readiness Cluster (2022). Checklist to Examine AI-readiness for Open Environmental Datasets. ESIP (Earth Science Information Partners). doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.19983722.v1

13

Estes J. A. Heithaus M. McCauley D. J. Rasher D. B. Worm B. (2016). Megafaunal impacts on structure and function of ocean ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour.41, 83–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085622

14

Fernandez N. (2018). Minimum information standards for essential biodiversity variables ( GEOBON). Available online at: https://www.db-thueringen.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/dbt_derivate_00044044/Fernandez_S3.3_ICEI2018.pdf (Accessed June 30, 2025).

15

Folorunso S. Ogundepo E. Basajja M. Awotunde J. Kawu A. Oladipo F. et al . (2022). FAIR machine learning model pipeline implementation of COVID-19 data. Data Intell.4, 971–990. doi: 10.1162/dint_a_00182

16

Foster S. D. Monk J. Lawrence E. Hayes K. R. Hosack G. R. Langlois T. et al . (2020). “ Chapter 2. Statistical considerations for monitoring and sampling,” in Field manuals for marine sampling to monitor Australian waters, version 2. Eds. PrzeslawskiR.FosterS. ( Marine Biodiversity Hub, National Environmental Science Programme, Hobart), 26–50. Available online at: https://www.nespmarine.edu.au/system/files/Przeslawski_2020_NESP%20field%20manuals%20V2_all.pdf (Accessed September 23, 2025).

17

Froese R. Winker H. Coro G. Demirel N. Tsikliras A. C. Dimarchopoulou D. et al . (2018). Status and rebuilding of European fisheries. Mar. Policy93, 159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.04.018

18

GBIF (2025). The global biodiversity information facility (GBIF). Available online at: https://www.gbif.org/what-is-gbif (Accessed May 3, 2025).

19

Gonzalez A. Vihervaara P. Balvanera P. Bates A. E. Bayraktarov E. Bellingham P. J. et al . (2023). A global biodiversity observing system to unite monitoring and guide action. Nat. Ecol. Evol.7, 1947–1952. doi: 10.1038/s41559-023-02171-0

20

GOOS (2025). The GOOS bioEco metadata portal. Available online at: https://bioeco.goosocean.org/ (Accessed June 30, 2025).

21

Halpern B. S. Walbridge S. Selkoe K. A. Kappel C. V. Micheli F. D’Agrosa C. et al . (2008). A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science319, 948. doi: 10.1126/science.1149345

22

Hanafi-Portier M. Borremans C. Soubigou O. Samadi S. Corbari L. Olu K. (2023). Benthic megafaunal assemblages from the Mayotte island outer slope: a case study illustrating workflow from annotation on images to georeferenced densities in sampling units. doi: 10.17882/97234

23

Hanafi-Portier M. Samadi S. Corbari L. Chan T.-Y. Chen W.-J. Chen J.-N. et al . (2021). When imagery and physical sampling work together: toward an integrative methodology of deep-sea image-based megafauna identification. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.749078

24

Hardisty A. R. Michener W. K. Agosti D. Alonso García E. Bastin L. Belbin L. et al . (2019). The Bari Manifesto: An interoperability framework for essential biodiversity variables. Ecol. Inf.49, 22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2018.11.003

25

Howell K. L. Davies J. S. Allcock A. L. Braga-Henriques A. Buhl-Mortensen P. Carreiro-Silva M. et al . (2020). A framework for the development of a global standardised marine taxon reference image database (SMarTaR-ID) to support image-based analyses. PloS One14, e0218904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218904

26

Hsieh T. C. Ma K. H. Chao A. (2016). iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol.7, 1451–1456. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12613

27

IPBES (2019). Global assessment report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat). Available online at: https://zenodo.org/record/6417333 (Accessed August 25, 2023).

28

Jones M. O’Brien M. Mecum B. Boettiger C. Schildhauer M. Maier M. et al (2019). Ecological Metadata Language version 2.2.0. doi: 10.5063/f11834t2

29

Katija K. Orenstein E. Schlining B. Lundsten L. Barnard K. Sainz G. et al . (2022). FathomNet: A global image database for enabling artificial intelligence in the ocean. Sci. Rep.12, 15914. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-19939-2

30

Langenkämper D. Zurowietz M. Schoening T. Nattkemper T. W. (2017). BIIGLE 2.0 - browsing and annotating large marine image collections. Front. Mar. Sci.4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00083

31

Langlois T. Goetze J. Bond T. Monk J. Abesamis R. A. Asher J. et al . (2020). A field and video annotation guide for baited remote underwater stereo-video surveys of demersal fish assemblages. Methods Ecol. Evol.11, 1401–1409. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.13470

32

Lin C. Chen W. Vanderbruggen T. Emani M. Xu H. (2022). “ Making machine learning datasets and models FAIR for HPC: A methodology and case study,” in 2022 Fourth International Conference on Transdisciplinary AI (TransAI). (Laguna, Hills, CA, United States: IEEE). 128–134. doi: 10.1109/TransAI54797.2022.00029

33

Magurran A. (2004). Measuring biological diversity (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing).

34

Mallet D. Pelletier D. (2014). Underwater video techniques for observing coastal marine biodiversity: A review of sixty years of publications, (1952–2012). Fisheries Res.154, 44–62. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2014.01.019

35

Mallet D. Wantiez L. Lemouellic S. Vigliola L. Pelletier D. (2014). Complementarity of rotating video and underwater visual census for assessing species richness, frequency and density of reef fish on coral reef slopes. PloS One9, e84344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084344

36

Mandeville C. P. Koch W. Nilsen E. B. Finstad A. G. (2021). Open data practices among users of primary biodiversity data. BioScience71, 1128–1147. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biab072

37

Marcillat M. Van Audenhaege L. Borremans C. Arnaubec A. Menot L. (2024). The best of two worlds: reprojecting 2D image annotations onto 3D models. PeerJ12, e17557. doi: 10.7717/peerj.17557

38

Monk J. Caroll A. Barrett N. (2023). BRUV and AUV annotation data for Elizabeth and Middleton reefs. doi: 10.25959/6WJ9-VY51

39

Navarro L. M. Fernández N. Guerra C. Guralnick R. Kissling W. D. Londoño M. C. et al . (2017). Monitoring biodiversity change through effective global coordination. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustainability29, 158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.02.005

40

OBIS (2025). The ocean biogeographic information system (OBIS). Available online at: https://obis.org/ (Accessed May 3, 2025).

41

ODATIS (2025). Scientific expert consortium on optical benthic imagery ( ODATIS). Available online at: https://www.odatis-ocean.fr/en/activites/consortium-dexpertise-scientifique/ces-imagerie-optique-benthique (Accessed May 3, 2025).

42

Pelletier D. (2020). Assessing the effectiveness of coastal marine protected area management: four learned lessons for science uptake and upscaling. Front. Mar. Sci.7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.545930

43

Pelletier D. Althaus F. Borremans C. Barrett N. Monk J. Olu K. et al . (2025). The QuatreA initiative: Acquiring, administering, analysing and applying data products derived from underwater optical imagery ( Ifremer, CSIRO, University of Tasmania).

44

Pelletier D. Roos D. Bouchoucha M. Schohn T. Roman W. Gonson C. et al . (2021). A standardized workflow based on the STAVIRO unbaited underwater video system for monitoring fish and habitat essential biodiversity variables in coastal areas. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.689280

45

Pelletier D. Schohn T. Carpentier L. Bockel T. Garcia J. (2023). STAVIRO example dataset, from data acquisition to the computation of Essential Biodiversity Variables and Essential Ocean Variables. doi: 10.17882/96690

46

Pelletier D. Selmaoui-Folcher N. Bockel T. Schohn T. (2020). A regionally scalable habitat typology for assessing benthic habitats and fish communities: Application to New Caledonia reefs and lagoons. Ecol. Evol.10, 7021–7049. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6405

47

Przeslawski R. Foster S. Monk J. Barrett N. Bouchet P. Carroll A. et al . (2019). A suite of field manuals for marine sampling to monitor Australian waters. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00177

48

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed March 7, 2019).

49

Rowden A. A. Anderson O. F. Georgian S. E. Bowden D. A. Clark M. R. Pallentin A. et al . (2017). High-resolution habitat suitability models for the conservation and management of vulnerable marine ecosystems on the Louisville seamount chain, South Pacific Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci.4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00335

50

Samuel S. Löffler F. König-Ries B. (2021). “ Machine Learning Pipelines: Provenance, Reproducibility and FAIR Data Principles,” in Provenance and Annotation of Data and Processes. Eds. GlavicB.BraganholoV.KoopD. ( Springer International Publishing, Cham), 226–230.

51

Saulnier E. Breckwoldt A. Robert M. Pelletier D. (2025). Remote underwater video for monitoring reef fish spawning aggregations. ICES J. Mar. Sci., 82, fsae194. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsae194

52

Schoening T. (2021). SOP: Image curation and publication. Version 1.0.0 and Supplement Version 1.0.0. Available online at: https://repository.oceanbestpractices.org/handle/11329/1781 (Accessed April 17, 2025)

53

Schoening T. Durden J. M. Faber C. Felden J. Heger K. Hoving H.-J. T. et al . (2022). Making marine image data FAIR. Sci. Data9, 414. doi: 10.1038/s41597-022-01491-3

54

Seiler J. (2013). Testing and evaluating non-extractive sampling platforms to assess deep-water rocky reef ecosystems on the continental shelf (Hobart: University of Tasmania). Available online at: https://eprints.utas.edu.au/16786/ (Accessed February 22, 2022).

55

Soga M. Gaston K. J. (2018). Shifting baseline syndrome: causes, consequences, and implications. Front. Ecol. Environ.16, 222–230. doi: 10.1002/fee.1794

56

Squidle+ (2025). A tool for managing, exploring & annotating images, video & large-scale mosaics. Available online at: https://squidle.org (Accessed September 24, 2025).

57

UMI (2025). Understanding marine imagery. Available online at: https://imos.org.au/facility/autonomous-underwater-vehicles/understanding-of-marine-imagery (Accessed May 3, 2025).

58

Untiedt C. Althaus F. Williams A. Maguire K. (2023). Tasmanian seamount Hill U: benthic imagery and annotations. doi: 10.25919/q6q8-r874

59

Untiedt C. B. Williams A. Althaus F. Alderslade P. Clark M. R. (2021). Identifying black corals and octocorals from deep-sea imagery for ecological assessments: trade-offs between morphology and taxonomy. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.722839

60

Vaz S. Laffargue P. Pelletier D. (2023). PAGURE example dataset from data acquisition to the computation of Essential Biodiversity Variables and Essential Ocean Variables. doi: 10.17882/97472

61

Wickham H. (2016). ggplot2. Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4

62

Wieczorek J. Bloom D. Guralnick R. Blum S. Döring M. Giovanni R. et al . (2012). Darwin core: an evolving community-developed biodiversity data standard. PloS One7, e29715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029715

63

Wilkinson M. D. Dumontier M. Aalbersberg I. Appleton G. Axton M. Baak A. et al . (2016). Comment: The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data3, 160018. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.18

64

Williams A. Althaus F. Schlacher T. A. (2015). Towed camera imagery and benthic sled catches provide different views of seamount benthic diversity. Limnol. Oceanogr.: Methods13, e10007. doi: 10.1002/lom3.10007

65

Yue P. Shangguan B. Ziebelin D. (2023). “ The OGC training data markup language for artificial intelligence (TrainingDML-AI) standard,” in Conference Abstracts, EGU-16998. (EGU General Assembly and Vienna, Austria: European Geosciences Union).

Summary

Keywords

Essential Ocean Variables, Essential Biodiversity Variables, benthic imagery, data reuse, monitoring, megafauna, fishes, benthic habitats

Citation

Pelletier D, Monk J, Althaus F, Borremans C, Hanafi-Portier M, Scoulding B, Olu K, Untiedt C, Jackett C, Barrett N, Laffargue P, Vaz S, Hasan E and Williams A (2025) Challenges of reusing marine image-based data for fish and benthic habitat Essential Variables: insights from data producers. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1676232. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1676232

Received

30 July 2025

Accepted

20 October 2025

Published

17 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Rachel Przeslawski, Southern Cross University, Australia

Reviewed by

Henry Ruhl, Central and Northern California Ocean Observing System (CeNCOOS), United States

Horacio Samaniego, Austral University of Chile, Chile

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Pelletier, Monk, Althaus, Borremans, Hanafi-Portier, Scoulding, Olu, Untiedt, Jackett, Barrett, Laffargue, Vaz, Hasan and Williams.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dominique Pelletier, dominique.pelletier@ifremer.fr

† Present address: Melissa Hanafi-Portier, UMR 7205, Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité, équipe 3E, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.