- School of Law, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China

The United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) and the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) have been working on an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment (Plastics Treaty) since 2022. This piece presents a perspective on the current progress of the Plastics Treaty from the first session of the UNEA to the last session of the INC as of August 2025, highlighting different positions of States and groups of States, based on which, argues that some of the key contentions remain throughout the negotiations.

1 Introduction

Despite the existence of several international conventions addressing plastic pollution, the fragmentation of them remains a significant issue (Wang, 2025; Kirk et al., 2024).1 These instruments tend to compartmentalize the marine environment and enact specialized pollution rules. Consequently, they often regulate only specific facets of marine plastic pollution (Kirk et al., 2024), leaving significant gaps in addressing the full spectrum of plastic and the remediation of environmental damage (Wang, 2025, 2023). This dilemma has substantially impeded the advancement and effectiveness of international efforts to control plastic pollution. In light of these challenges, the resolution adopted by the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) and the ongoing development of an international legally binding instrument (ILBI) on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment (the Plastics Treaty) represents a crucial future direction for global plastic management.

Scholars have discussed the Plastics Treaty from different perspectives, for example, plastic control from the perspectives of specific States (Chang et al., 2024; Stöfen-O’Brien and Graham, 2024), from the perspectives of principles of international law (Wang, 2025; Xu et al., 2023), the supplementing role of the Plastics Treaty to the overall landscape (Wang, 2025; van der Marel and Stöfen-O’Brien, 2024), the challenges along the way of the new treaty (Wang, 2023), among others. Yet the overall progress, especially from UNEA sessions to INC sessions, have not been thoroughly analyzed, particularly the different positions of States and their core disagreements throughout the negotiations. This piece aims at systematically demonstrating the progress and gaps of the negotiations of the Plastics Treaty. This piece is structured as follows. After introduction, it summarizes the UNEA sessions and INC sessions, with a focus on different positions of States, based on which, the future trajectories for the Plastics Treaty are discussed.

2 Gaps, progress and positions of States during negotiations

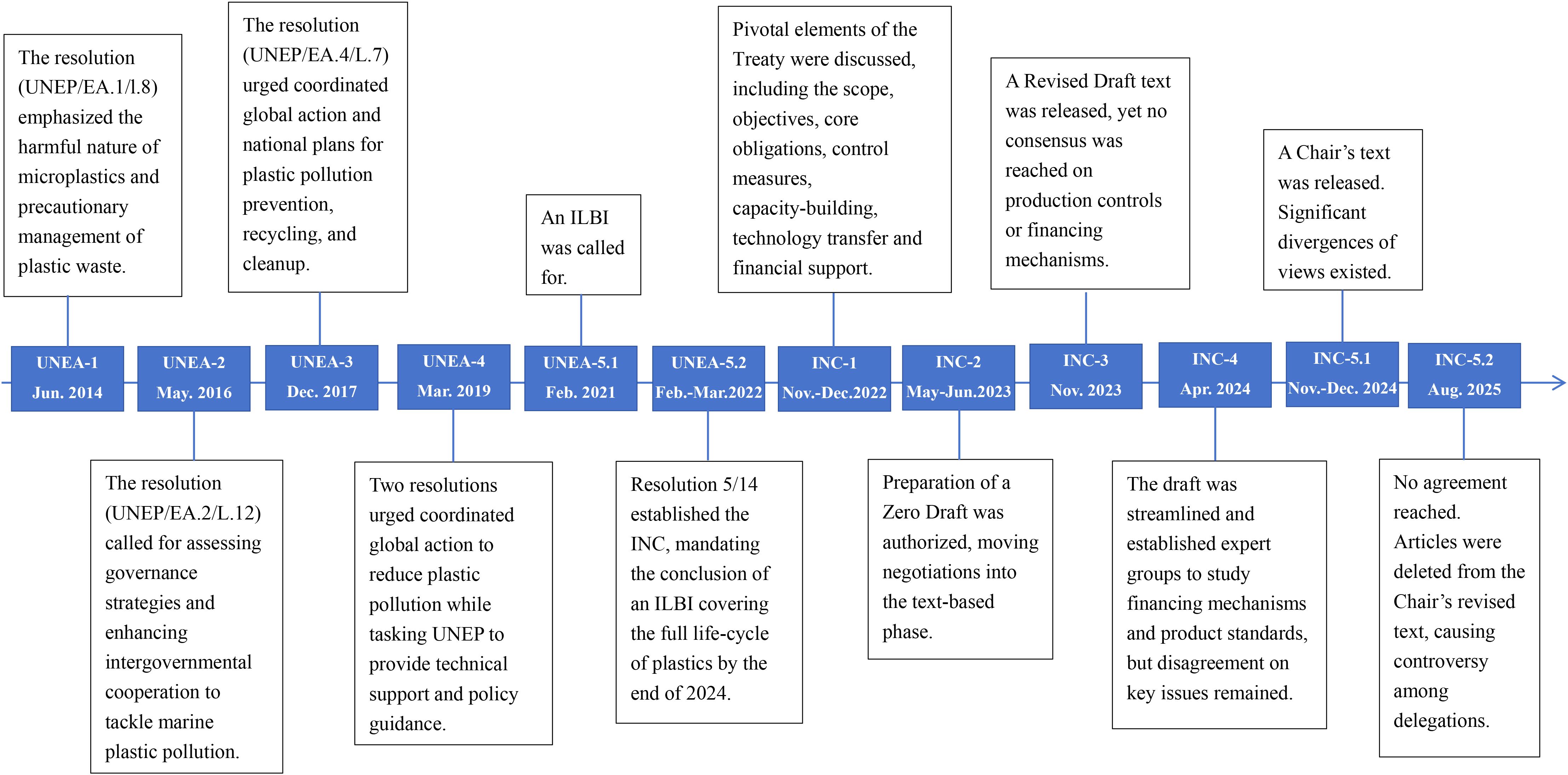

This section discusses gaps and progress of the Plastics Treaty, with a focus on States’ different positions. Figure 1 demonstrates the timeline of key negotiation milestones.

2.1 The UENA sessions

In 2013, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Governing Council was re-designation as the UNEA. At its inaugural session in 2014, the UNEA adopted a landmark resolution titled “Marine Plastic Debris and Micro Plastics” (UNEP, 2014a). This resolution, building upon a proposal by Norway (UNEP, 2014b), underscored the detrimental impacts and origins of micro plastics. In direct response to the request from the first session of the UNEA (UNEA-1), a comprehensive study titled “Marine Plastic Debris and Microplastics: Global Lessons and Research to Inspire Action and Guide Policy Change” was issued (UNEP, 2016a). This study effectively extended the foundational content established at UNEA-1, offering concrete recommendations concerning the implementation of existing agreements and proposing novel methods and measures for plastic pollution prevention (Wang, 2023).

The second session of the UNEA (UNEA-2) convened in 2016, operating within the broader framework of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015). This ambitious agenda, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, specifically aimed to “prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land-based activities, by 2025” (UN, 2015). The outcomes of UNEA-2 were thus directly aligned with these overarching global objectives for environmental protection (UNEP, 2016b). UNEA-2 significantly broadened its focus to encompass the comprehensive issue of plastic pollution and microplastics generation (Wang, 2023). A key emphasis UNEA-2 advocated for the establishment of public-private partnerships, recognizing the critical role of collaboration involving a wide array of actors in addressing plastic pollution (Cui, 2023).

At the third session of UNEA (UNEA-3) held in 2017, an open-ended ad hoc expert group was established, which convened twice prior to the fourth session of the UNEA (UNEA-4). The expert group was specifically mandated to conduct further in-depth studies on the sources of marine plastic debris and micro plastics (UNEP, 2017). A pivotal assessment report “Combating Marine Plastic Litter and Micro plastics: An Effective Assessment of Relevant International, Regional and Subregional Governance Strategies and Approaches” (UNEP, 2018) was presented by the expert group in 2018. This report systematically collated, categorized, and evaluated existing ILBIs pertaining to plastics governance (Wang, 2023). Based on its findings, the report put forth recommendations for either the revision and expansion of the current legal framework or, alternatively, the development of a new ILBI to address plastic pollution (UNEP, 2018).

The UNEA-4, held in 2019, called for strengthening the connection between science and policy (UNEP, 2019). A key emphasis was placed on mitigating the problem of marine plastic through the crucial mechanism of increasing resource recovery rates (UNEP, 2019). UNEA-4 articulated clear aspirations to encompass the entire life cycle of plastics, promoting a holistic approach to addressing plastic pollution (Wang, 2025, 2023).

The fifth session of the UNEA (UNEA-5) convened in two phases. By 2021, the escalating global plastic pollution crisis had galvanized numerous stakeholders, leading to widespread calls for the establishment of a new ILBI. During the initial phase of the UNEA-5 (UNEA-5.1), held in February 2021, States unequivocally reiterated the need to address plastic pollution (Wang, 2025; Sun et al., 2021). In response, the UNEP released an assessment report titled “From Pollution to Solution: A Global Assessment of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution” (UNEP, 2021). This report was specifically designed to inform the discussions at the second phase of UNEA-5 (UNEA-5.2).

Prior to the UNEA-5.2 in 2022, following extensive negotiations within the Open-ended Committee of Permanent Representatives and subsequent contact group, States ultimately agreed to consolidate a unified draft resolution (Tu, 2022). This culminated in the adoption of a landmark resolution titled “End Plastic Pollution: Towards an International Legally Binding Instrument (End Plastic Pollution Resolution)” (UNEP, 2022a). The resolution adopts a comprehensive approach addressing the entire life cycle of plastics, which extends beyond pollution management to encompass all stages, from plastic production and design to consumption and disposal (Wang, 2025; Life Cycle Initiative, 2025). Additionally, it establishes a foundational framework for the ILBI and delineates essential provisions, including objectives, principles and strategies (Environmental Investigation Agency, 2025). Most importantly, it mandates the establishment of an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) with the ambitious objective of concluding an ILBI by the end of 2024.

2.2 The INC sessions

The inaugural session of the INC (INC-1) commenced its work in 2022 in Uruguay (UNEP, 2025a). INC-1 featured extensive dialogues pertaining to the pivotal elements of the Plastics Treaty, including the scope, objectives, core obligations, control measures, capacity-building, technology transfer and financial support (UNEP, 2022b). Although consensus emerged on the necessity of addressing the entire life cycle of plastics, divergent perspectives persisted concerning the prioritization of specific segments within this life cycle. A notable point of contention centered on whether to emphasize upstream interventions, such as source reduction and production control (Wen et al., 2022), or downstream approaches, focusing on leakage prevention and end-of-life waste management (Chile, 2022; Peru, 2022; Switzerland, 2022). What States advocate for behind the upstream or downstream interventions is the concern over their economic interests. Plastic primary raw materials, predominantly hydrocarbons – such as natural gas, petroleum, coal – are processed into fundamental plastic monomers. As foundational chemical feedstocks, the governance of hydrocarbons intersects with critical sectors including energy and the chemical industry, encompassing processes from mining and production to transportation and storage of petroleum and natural gas. Similarly, processed plastic intermediate products are central to chemical manufacturing. As previously articulated by the United Kingdome delegation, these substances possess applications extending beyond plastic manufacturing (the United Kingdom, 2023). Consequently, their inclusion within the treaty’s regulatory scope, and subsequent restriction, could exert significant economic repercussions on other domestic industries.

Concerning core obligations and control measures, divergence of views was centered on the preference for either a top-down model characterized by legally binding constraints, or a bottom-up approach with national flexibility and voluntary contributions (Beijing Luyan Center for Philanthropy and Development, 2023). These contrasting perspectives highlight the complex challenges in forging a globally harmonized approach to plastic pollution governance.

The second session of the INC (INC-2) honed in on twelve issues, including strategies for phasing out and reducing the supply, demand and use of primary plastics, alongside measures for reducing microplastics (Cowan et al., 2024). INC-2 prioritized strengthening waste management systems, promoting circular design principles, fostering the adoption of safe and sustainable alternatives (UNEP, 2023a). A key outcome was the mandate for the preparation of a Zero Draft of the treaty (UNEP, 2023a).

In September 2023, preceding the third session of INC (INC-3) in Kenya, the Zero Draft of the Plastics Treaty was finalized. The draft placed emphasis on several critical areas: the reduction of primary plastics, the elimination of certain polymers and chemicals, phasing out of short-lived plastics, fostering transparency in the production of plastic products, and promoting the reuse of plastics (UNEP, 2023b). To facilitate further deliberations, the draft offers multiple options for each element (UNEP, 2023c). The draft encompasses sixteen options for the scope of the Plastics Treaty, which are primarily drawn from the statements of 22 national delegations.2 These options can be categorized into five approaches, which highlight the complexities in reaching a consensus on the precise boundaries of the treaty:

1. Absence of standalone scope provisions (Option 0): it suggests that the instrument should not include specific provisions defining its scope.

2. Full life cycle coverage without explicit definition (Options 1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 15): it does not provide a clear definition of what constitutes the full life cycle.

3. Comprehensive life cycle and all sources (Options 5, 16): it suggests an explicit cover over the complete life cycle of plastics, from extraction and production through design, use, consumption, disposal, and remediation, addressing all sources of plastic pollution.

4. Exclusion of upstream stages (Options 3, 6, 10, 13): it suggests excluding the initial stages of extraction and processing of primary raw materials, as well as virgin polymer production.

5. Scope defined by core obligations (Option 9): it suggests a clear definition of the full life cycle of plastics can only be established once the core obligations of the treaty have been mutually agreed.

At INC-3, deliberations spanned the entire plastics value chain, which includes upstream considerations, such as the control and reduction of plastic polymers and chemicals; midstream interventions, covering the control of plastic products, microplastics and enhanced producer involvement in product design; and downstream management, encompassing waste management strategies and the international trade of plastic waste (UNEP, 2023c). These comprehensive discussions were incorporated into the Revised Draft released in December 2023 (UNEP, 2023d).

The fourth session of the INC (INC-4) convened in Canada in April 2024. The primary objectives were to streamline the Revised Draft (UNEP, 2024a). Representatives from different groups of States focused on different aspects of the treaty. Notably, Kazakhstan (2024a) and Russia (2024a) object to the establishment of a special fund and the charging of fees for pollution, arguing such an approach ignores the differences in plastic pollution and governance capacity in different countries (Wang, 2025).

The above positions indicate that delegations shared the recognition that plastic pollution demands an ILBI, and that effective implementation will necessitate financial, technical, and capacity-building support (Wang, 2023). The key disputes lie in the how — the level of ambition, specific mechanisms, and the allocation of responsibilities (Wang, 2025).

One of the main issues is what constitutes the “entire life cycle of plastics” and whether plastic production should be addressed by the treaty (Earth Negotiations Bulletin of IISD, 2024). States’ positions can be summarized into several groups. Iran, Israel, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, China and Russia advocate for some sort of exclusion, including raw materials, intermediate products, primary raw materials, virgin polymer production (Kazakhstan, 2024b; China, 2024; Malaysia, 2024; Iran, 2024; Israel, 2024; Russia, 2024b). Conversely, the European Union (EU), Australia and other countries (the European Union, 2024; Australia, 2024; Thailand, 2024; Rwanda, 2024; Panama, 2024; Guatemala, 2024; Philippines, 2024) voted for including regulation of primary plastic polymers in the scope, believing that restricting production is an effective way to reduce plastic pollution, while Russia, Kazakhstan, Kuwait and other countries (Russia, 2024c; Kazakhstan, 2024c; Kuwait, 2024; Egypt, 2024; Vietnam, 2024) expressed strong opposition, believing that this is beyond the scope of the authorization of the UN resolution, which may have a negative impact on the petrochemical industry and their economy (Wang, 2025). Consequently, two expert groups were established subsequent to INC-4, aiming to further study the upwards of 3,700 elements that remained unagreed upon (UNEP, 2024a, 2024b).

The fifth session of the INC (INC-5.1) convened in November 2024 in Korea. One month prior to INC-5.1, the INC Chair’s “Non-paper 3” was released (Valdivieso, 2024), which was designed to replace the Revised Draft. INC-5.1 was strategically organized into four contact groups with distinct focuses to facilitate detailed and thematic negotiations (UNEP, 2024c). This approach aimed to ensure comprehensive coverage of the myriad components necessary for the ILBI (UNEP, 2024c).

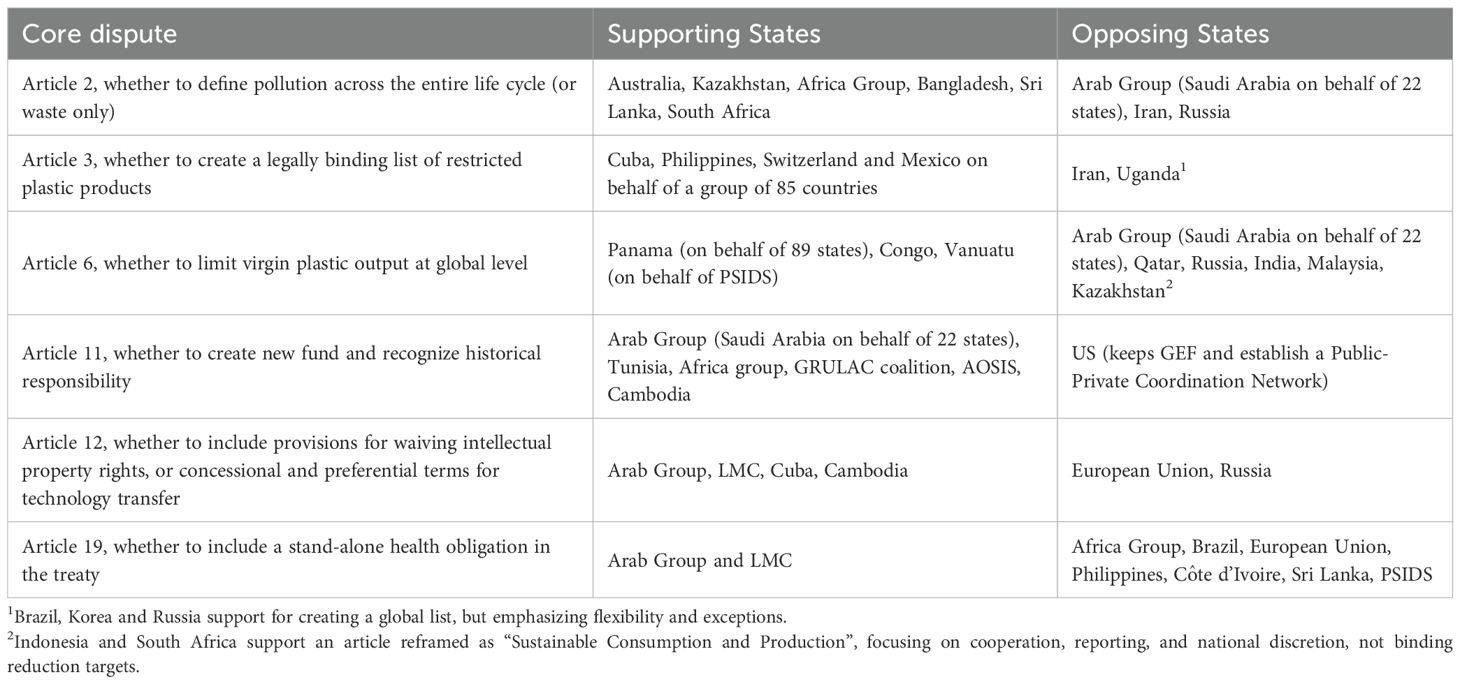

The Chair’s Text was released then in December 2024 (UNEP, 2024d). A notable feature was that Article 3 and 6 are the sole articles entirely enclosed in “box codes”, implying their potential for complete deletion if consensus cannot be achieved. Furthermore, significant controversy surrounds Article 11 on the financial mechanism. While there is a general consensus on the necessity of establishing such a mechanism, considerable disagreements persist regarding the allocation of responsibilities and obligations, the source and utilization of funds, and the operational modalities of the mechanism (Wang, 2025; UNEP, 2024d).

The second part of the fifth session (INC-5.2) took place in August 2025 in Switzerland, and no treaty was adopted (UNEP, 2025b). Despite 10 days of intensive negotiations, disagreements persisted. The Chair’s draft deleted the terms of scope and definitions, including those for “plastic”, “plastic pollution”, “plastic products” and “plastic waste”. This means, plastic was not defined at all in the Plastics Treaty in this draft. Articles 6, 14 and 19 were also deleted, which sparked intense controversy. The EU criticized the text for violating the authorization of UNEA and lacking full life-cycle management; the United States claimed that the draft crossed a red line; The Arab Group, China, India, Iran and others strongly opposed the new category of “developing countries with financial capacity” introduced in the Chair’s draft, calling it unjustified and unauthorized (Earth Negotiation Bulletin of IISD, 2025). The Chair’s revised text was released on the last day of INC-5.2 and was also criticized by delegations, as illustrated by Table 1. Eventually, INC-5.2 failed to reach into an agreement.

3 Discussion

While being called “the most important negotiation you’ve (probably) never hear of” (Bodansky, 2024), INC-5.2 failed to adopt the Plastics Treaty. Throughout the UNEA and INC sessions, progress has been made yet the key contentions remain, which arguably represents that the fundamental disagreements among States did not progress, leading to the failure of the ambition to finalize the instrument by the mandated 2024 deadline.

The fact that INC-5.2 did not conclude the Plastics Treaty reflects that the ambitious States may have set up too high a target that others are not ready to or capable of reaching it. Or from the opposite perspective, States depending more on plastic, regardless of which stage out of the cycle, are not provided with sufficient replacement for their dependency, either economically, socially or industrially. The failure to finalize the treaty also indicates that the middle ground where both sides meet by compromising their interests and needs has not been found yet.

Scholars have suggested that the negotiations of other instrument can shed light on the Plastic Treaty (Beringen, 2025; Li and Xing, 2024). One lesson is that an effective treaty on plastics pollution control requires major players such as China, India and the United States to be a part of, which means the disagreements identified in this piece require compromise by both the ambitious States and the others.

As such, the way forward for the Plastics Treaty requires a strategic and conciliatory approach that acknowledges the deep-seated disagreements over scope, legal frameworks, and financial mechanisms. Common ground could involve flexible provisions that accommodate differing national priorities, including economic dependencies on plastics and capacity constraints. Establishing phased commitments or interim measures could serve as practical steps to bridge gaps, allowing Parties time to build capacity. Ultimately, consensus will depend on balancing environmental ambitions with social and economic realities, emphasizing a collaborative approach that strives for not only equitable but more importantly achievable outcomes to ensure the treaty’s successful finalization and adoption.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Writing – original draft. RH: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research is funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (24CFX113).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ These international instruments include, inter alia, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, the Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses. For discussion on how they are relevant to the Plastics Treaty – for instance, how their fragmented approaches inform the need for a unified instrument, or how their enforcement mechanisms might serve as precedents, see Wang, S. (2023), International Law-Making Process of Combating Plastic Pollution: Status Quo, Debates and Prospects, Mar. Policy, 147; Kirk, E. A., Popattanachai, N., Barnes, R. et al. (2024), Research Handbook on Plastics Regulation Law, Policy and the Environment, Edward Elgar.

- ^ They are: Costa Rica, India, Indonesia, Turkey, Russian Federation, Samoa on behalf of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), Chile, China, Iran, Kenya, Mexico, European Union, Cook Island, Norway, Panama, Singapore, Africa, Guatemala, Philippines, Republic of Korea, Qatar, Fiji.

References

Australia (2024). Australia New Text Proposal for Sub-Group 1.2 Part II.1. Primary Plastic Polymers. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/australia_primary_plastic_pollution_text_submission.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Beijing Luyan Center for Philanthropy and Development (2023). Summary and outlook of the first intergovernmental negotiations on plastic pollution. Available online at: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/m4nbJwHGiMagi4GNJb3-FQ (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Beringen E. (2025). Exploring the Potential for Inter-Regime Learning Between the BBNJ Agreement and the Global Plastics Treaty. Ocean Dev. Int’l. Law. doi: 10.1080/00908320.2025.2529780

Bodansky D. (2024). The Most Important Negotiation You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of. Available online at: https://www.ejiltalk.org/the-most-important-negotiation-youve-probably-never-heard-of/ (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Chang Y.-C., Sun K., and Wang Y. (2024). “Legal issues regarding plastic pollution control in China,” in Research Handbook on Plastics Regulation Law, Policy and the Environment. Eds. Kirk E. A., Popattanachai N., Barnes R., and van der Marel E. R. (Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar), 330–353.

Chile (2022). Submission of Chile Follow up of the Open-Ended Working Group for the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to Develop an International Legally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/chile_inc_submission.pdf (Accessed July 31, 2025).

China (2024). Part I 5. Scope (merge option 3 and option 13). Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/cg1_part_i.5_chn_textual_submission_april_24.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Cowan E., Holmberg K., Nøklebye E., Rognerud I., and Tiller R. (2024). It Takes Two to Tango: The Second Session of Negotiations (INC-2) for a Global Treaty to End Plastic Pollution. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 14, 428. doi: 10.1007/s13412-024-00906-4

Cui Y. (2023). The recent dynamics, realistic challenges and China’s response to the global governance of marine plastic litter. Pacific J. 3, 81–93. doi: 10.14015/j.cnki.1004-8049.2023.03.007

Earth Negotiations Bulletin of IISD. (2024). Summary of the Fourth Session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to Develop an International Legally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution: 23–29 April 2024. Available online at: https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marine-environment-negotiating-committee-inc4-summary (Accessed July 28, 2025).

Earth Negotiation Bulletin of IISD. (2025). Daily report for 13 August st. Available online at: https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution (Accessed August 16, 2025).

Egypt. (2024). Egypt’s Submission on Part 2.1 of The Revised Zero draft Primary Plastic Polymers. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/egypts_submission_on_part_2-1.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Environmental Investigation Agency. (2025). Available online at: https://reports.eia-international.org/a-new-global-treaty/ (Accessed July 29, 2025).

European Union. (2024). European Union and its Member States–text proposal on Primary plastic polymers. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/european_union_part2_primary_plastic_polymers.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Guatemala. (2024). Guatemala Intervention. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/part_ii_-_1_primary_plastic_polymers.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Iran. (2024). Iran Inputs on Preamble, Objectives, Principles and Scope. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/cg1-_sub_cg1.1-_iran_inputs_on_preamble_objectives_principles_and_scope_0.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Israel. (2024). Objective and Scope. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/objective_and_scope.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Kazakhstan. (2024a). Part III.1–Financing [mechanism [and resources]. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/part_iii_1.2.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Kazakhstan. (2024b). Part I.5 – Scope. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/part_i.5.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Kazakhstan. (2024c). Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/part_ii.1-3_kazakhstan_26.04.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Kirk E. A., Popattanachai N., Barnes R., and van der Marel E. R.. (2024). “An Introduction to Plastics Regulation: Law, Policy and the Environment,” in Research Handbook on Plastics Regulation Law, Policy and the Environment. Eds. Kirk E. A., Popattanachai N., Barnes R., and van der Marel E. R.. (Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar).

Kuwait. (2024). Kuwait intervention Contact Group 1. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/25-4-2024_kw_cg1_p.p.p.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Li J. and Xing W. (2024). A Critical Appraisal of the BBNJ Agreement not to Recognize the High Seas Decline as A Common Concern of Humankind. Mar. Policy 106131. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106131

Life Cycle Initiative. (2025). Available online at: https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/activities/life-cycle-assessment-in-high-impact-sectors/life-cycle-approach-to-plastic-pollution/ (Accessed July 27, 2025).

Malaysia. (2024). Malaysia’s Written Submission for INC-4 Contact Group 1 (Subgroup 1.1). Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/my_inc-4_part_i.5.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Panama. (2024). Cuarta Sesión Del Comité Intergubernamental De Negociación (Inc4) Para Desarrollar Un Instrumento Internacional Jurídicamente Vinculante Sobre La Contaminación Por Plásticos, Incluido En El Medio Marino. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/panama_-_group_1_-_subgroup_1.2_part_ii._1_primary_plastic_polymers_0.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Peru. (2022). Contributions of Peru to the Process of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC). Available online at: https://apps1.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/peru_submission_inc_plastics_eng_rev.pdfoverlay-context=node/344%3Fq%3Dnode/344 (Accessed July 31, 2025).

Philippines. (2024). Subgroup 1.2 Part II 1 – Primary plastic polymers. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/phl_sg_1.2_25_apr_part_ii_1.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Rwanda. (2024). Rwanda New Text Proposal for Sub-Group 1.2 Part II.1 Primary Plastic Polymers. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/rwanda_text_proposal_for_primary_plastic_polymers_0.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Stöfen-O’Brien A. and Graham R. (2024). The Establishment of Science–Policy Interfaces for the Global Plastics Treaty: Reflections on Small Island Developing States’ Perspectives. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 39,497–501. doi: 10.1163/15718085-bja10187

Sun Y. Z., Lin Y., Steindal E. H., Jiang C., Yang S., and Larssen T. (2021). How Can the Scope of a New Global Legally Binding Agreement on Plastic Pollution to Facilitate an Efficient Negotiation Be Clearly Defined? Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 6527–6528. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c02033

Switzerland. (2022). Follow-up to the OEWG plastic pollution Written submission from Switzerland. Available online at: https://apps1.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/switzerland_1.pdf (Accessed July 31, 2025).

Thailand. (2024). Thailand Reflections on the Part II.1 Primary Plastic Polymer. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/thailand_reflections_on_the_part_ii.1.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

The Russian Federation. (2024a). Intervention of the Russian Federation. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/russia_cg2_sg2.1_part_iii_finance_and_fee_cg2.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

The Russian Federation. (2024b). Suggestions of the Russian Federation regarding technical streamlining of Section I.5 “Scope”. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/russias_proposal_for_technical_streamlining_of_scope_cg1.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

The Russian Federation. (2024c). The intervention of the Russian Federation in regard of Article 1. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/part_ii_article_1_intervention_of_the_russian_federation_during_subgroup_1_2_meeting.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. (2023). Submission of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Part A. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/united_kingdom_15092023_a.pdf (Accessed July 30, 2025).

Tu R. H. (2022). A review of the fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly. World Environ. 02), 18–23.

UNEP. (2014a). Marine plastic litter and microplastics, UN Doc UNEP/EA.1/6. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/17285/K1402364.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed= (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2014b). Proceedings of the United Nations Environment Assembly, UNEP/EA.1/10. Available online at: https://docs.un.org/en/UNEP/EA.1/10 (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2016a). Marine plastic debris and microplastics: global lessons and research to inspire action and guide policy change. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/77206 (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2016b). Marine plastic litter and microplastics, UNEP/EA.2/Res.11, preamble paras 6–7. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/11186/K1607228_UNEPEA2_RES11E.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2017). Marine plastic litter and microplastics, UNEP/EA.3/Res.7, para 10. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/31022/k1800210.english.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2018). Discussion paper on barriers to combating marine litter and microplastics, including challenges related to resources in developing countries. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/unep_aheg_2018_1_2_barriers_edited_0.pdf (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2019). Marine plastic litter and microplastics, UNEP/EA.4/Res.6. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/28471/English.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2021). From pollution to solution: a global assessment of marine litter and plastic pollution. Available online at: https://www.unep.org/resources/pollution-solution-global-assessment-marine-litter-and-plastic-pollution (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2022a). End plastic pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument, Resolution 5/14. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/39812/OEWG_PP_1_INF_1_UNEA%20resolution.pdf (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2022b). Report of the intergovernmental negotiating committee on plastic pollution (INC-1), UN Doc UNEP/PP/INC.1/7. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/42282/INC1reportReissuedAdvance.pdf (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2023a). Report of the intergovernmental negotiating committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, on the work of its second session, UN Doc UNEP/PP/INC.2/5. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/42953/FinalINC2Report.pdf (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2023b). Zero draft text of the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, UN Doc UNEP/PP/INC.3/4. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/algeria_0.pdf (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2023c). Report of the intergovernmental negotiating committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, on the work of its third session, UNEP/PP/INC.3/5. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/44760/INC3ReportE.pdf (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2023d). Revised draft text of the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, UNEP/PP/INC.4/3. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/44526/RevisedZeroDraftText.pdf (Accessed July 29, 2025).

UNEP. (2024a). Report of the intergovernmental negotiating committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, on the work of its fourth session, UNEP/PP/INC.4/5. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/45872/INC4_Report.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

UNEP. (2024b). Compilation of draft text of the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, UNEP/PP/INC.5/4. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/45858/Compilation_Text.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

UNEP. (2024c). Note by the Chair providing further detail relevant to the organization of work at the fifth session of the intergovernmental negotiating committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, UNEP/PP/INC.5/7. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/46645/Chairs_Note_Chinese.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

UNEP. (2024d). Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/46710/Chairs_Text.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

UNEP. (2025a). Available online at: https://www.unep.org/inc-plastic-pollution (Accessed July 28, 2025).

UNEP. (2025b). Available online at: https://www.unep.org/inc-plastic-pollution/session-5.2 (Accessed August 16, 2025).

United Nations. (2015a). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1. Available online at: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/70/1.

Valdivieso L. V. (2024). Non-Paper 3 of the Chair of The Committee. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/46483/Non_Paper_3_E.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

van der Marel E. R. and Stöfen-O’Brien A. (2024). Accommodating a Future Plastics Treaty: The “Plasticity” of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 39,322–324. doi: 10.1163/15718085-bja10164

Vietnam. (2024). Vietnam’s written submission Contact Group 1 (Subgroup 1.2). Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/text_proposal_viet_nam_for_primary_plastic_polymers.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

Wang S. (2023). International law-making process of combating plastic pollution: Status Quo, debates and prospects. Mar. Policy 147, 105376. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105376

Wang S. (2025). Revisiting the Common but Differentiated Responsibility Principle in the Prevention and Control of Marine Plastic Pollution. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 40, 1–21. doi: 10.1163/15718085-bja10223

Wen Z. G., Hu Y. P., Tan Y. Q., Tian Y. Q., Chen H. J., Wang X. Y., et al. (2022). Reflections on the first intergovernmental negotiation on plastic pollution control: How to further reach an agreement? Environ. Economy 23, 4.

Keywords: UNEA, UNEP, future trajectory, funding mechanism, scope of the treaty

Citation: Guo J and Hu R (2025) The plastics treaty: steps forward, agreement deferred. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1677615. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1677615

Received: 01 August 2025; Accepted: 25 August 2025;

Published: 08 September 2025.

Edited by:

Qi Xu, Jinan University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Guo and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianping Guo, Z3VvamlhbnBpbmdAeGp0dS5lZHUuY24=

Jianping Guo

Jianping Guo Rui Hu

Rui Hu