Abstract

With the increasing intensity and duration of marine heatwaves (MHW), there has been a corresponding rise in bleaching events. These events cause severe ecological impacts, yet most studies have focused on directly impacted or economically important species, such as corals and fish. However, the impacts of heat-induced bleaching on specialized predators, particularly those that feed on prey susceptible to bleaching, remain largely unknown. This gap of knowledge is especially concerning given that many of these specialized species have complex life cycles, for which stage specific tolerance is poorly characterized, and have narrow geographic ranges, potentially increasing their vulnerability to environmental change. Here, we tackle this issue by studying the impact of a MHW event and bleaching of prey on the thermal plasticity throughout the life cycle of the stenophagous nudibranch, Berghia stephanieae. We tested the Critical Thermal Maxima (CTmax) of embryos, juveniles and adults of Berghia stephanieae. We found that while none of the tested treatments significantly impacted B. stephanieae’s CTmax, juveniles had a significantly lower CTmax than the remaining life stages under optimal conditions. We also found that survival decreases under MHW conditions, particularly in embryos, that failed to survive past four days of exposure. Lastly, heat tolerance plasticity was minimal in this species. These findings highlight this nudibranch’s limited acclimation capacity for acute thermal stress, and that the tolerance of its early life stages will most likely be the most critical for its survival under future extreme climate scenarios.

1 Introduction

A complex life cycle is one that is characterized by a sudden ontogenetic transition (e.g. metamorphosis), that involves significant changes in the individual’s physiology, morphology, and/or behavior, as well as the habitat it occupies (Wilbur, 1980). These life cycles are the ones most common among animals (Werner, 1988; Rumrill et al., 2018; Saltini et al., 2023), and marine invertebrates are no exception to this, encompassing various developmental stages adapted to different ecological roles and environmental conditions (Gibson, 2011; Iwasa et al., 2022). As the various developmental stages are vastly different, they may display different tolerances to environmental variation, such as climate change and extreme weather events (Pandori and Sorte, 2019). There is no universal pattern in how sensitivity to environmental conditions varies across different developmental stages. Even though most life stages are sensitive to climate extremes, it is fairly common for the earlier developmental stages to be less robust (Pandori and Sorte, 2019). Furthermore, phenotypic plasticity, the ability of an organism to create different phenotypes to adapt to different environmental conditions (Sommer, 2020), has also been shown to differ and to not be stagnant throughout an organism’s life cycle (Fischer et al., 2014). Indeed, this mechanism involves a myriad of molecular defenses and physiological and behavioral responses to try to counteract and resist to external stressors (Leung et al., 2019; Madeira et al., 2021; Han et al., 2023). Various factors can influence phenotypic plasticity, including external abiotic stressors (e.g. temperature), biotic stressors (e.g. predator-prey interactions) or internal conditions of the organism (e.g. health, nutritional or reproductive status) (Padilla and Savedo, 2013; Klingenberg, 2019; Abdelnour et al., 2024). When under extreme weather events, the plasticity of a species may drive its fate, with species from highly variable environments being hypothesized to be more resilient (Canale and Henry, 2010; Chevin and Hoffmann, 2017).These organisms were found to endure such temperature changes through inherent high thermal limits (Stillman, 2002; Madeira et al., 2012a) or changes in metabolic activity (Rivera-Ingraham et al., 2016; Zeppilli et al., 2018; Hui et al., 2020).

Climate change can be a major threat to species with complex life cycles (Lowe et al., 2021) and a source of phenotypic plasticity among marine invertebrates (Byrne et al., 2020). With the continuous increase of human pressure on marine habitats, marine organisms are subject to rapid changes in their environment (Doney et al., 2012). Among global changes, the warming of the oceans is one of the most concerning, given the prevalence of ectothermy among marine species. High temperature has a wide range of impacts across biological hierarchy levels on various classes of organisms. These impacts range from altered cellular functioning (Madeira et al., 2020; Guscelli et al., 2023) to increased or decreased metabolic rates at moderate and extreme temperature, respectively (Minuti et al., 2021). Additionally, population changes, such as range shifts, and prey-predator chronological mismatch resulting in a lack of food have also been reported in marine ecosystems (Asch et al., 2019; Weiskopf et al., 2020; Fournier et al., 2024). Even though some species are able to endure these changes, others lack the physiological tolerance to do so (Cooke et al., 2013) or the phenotypic plasticity to adapt and thrive under such new conditions (Fox et al., 2019).

Unlike global warming, which was defined by Harkiolakis (2013) as a sustained increase in the globe’s temperature over a prolonged period of time, marine heatwaves (MHW) are a much faster, shorter and more intense thermal stress. In fact, MHW is a term first coined by Pearce et al. (2011) to define a period of abnormally high-water temperature. Nowadays, the most used definition of MHW is the one by Hobday et al. (2016) stating that it is a period of 5 or more consecutive days where the sea surface temperature of a given place is above the 90th percentile of the local climatological time series (Hobday et al., 2016; Joyce et al., 2024). Under such acute thermal stress organisms can incur into sub-lethal or even lethal damage (Villeneuve and White, 2024).

Organisms inhabiting shallow waters (e.g. intertidal areas, estuaries) are commonly adapted to more pronounced thermal fluctuations, as they experience periodical shifts on seawater temperature in these habitats. Nonetheless, due to their extreme home environment, some species are already living close to their physiological limit, thus often impairing them to cope with added stress (Somero, 2005; Madeira et al., 2017; Missionário et al., 2022). Considering the heightened severity (i.e. intensity, duration and frequence) of extreme climate events, understanding species upper thermal limits and how these are impacted by predicted future climate conditions (i.e. ocean warming, MHWs) is paramount for ecosystem modelling and conservation efforts (Gillooly et al., 2001; Stillman, 2019; Vinagre et al., 2019; Divu et al., 2024).

Nudibranchia, one of the most species-rich orders of mollusks, with over 3000 extant species (Marchel et al., 2021), features several eurythermal organisms (species with a high range of thermal tolerance). Nudibranchs are slow-moving ectotherms that when exposed to thermal stress commonly rely on physiological mechanisms of compensation (Marshall et al., 2011; Armstrong et al., 2019). Berghia stephanieae, (Valdés, 2005) is one of such nudibranchs. This species is endemic to Florida (U.S.A.) and its distribution range is particularly narrow, occurring from the northernmost point at 25.7 °N to the southernmost point on 25.09 °N, and the westernmost point at 80.44 °W to the easternmost point at 80.2 °W (Liu et al., 2021). It is a simultaneous hermaphrodite which features a facultative lecithotrophic larval stage, i.e. their embryos either hatch as a lecithotrophic larvae, that undergoes metamorphosis within the first day of life, or metamorphose still before hatching and emerge as an imago of the adult (Carroll and Kempf, 1990; Banger, 2011; Silva et al., 2023). This species is a stenophagous predator, feeding solely on the glass anemone Exaiptasia diaphana (Rapp, 1829). This anemone establishes and maintains a long-term symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic endosymbiontic dinoflagellates (Symbiodiniaceae). While this nudibranch can retain some of the photosynthetic endosymbionts of its prey, it does not establish a true mutualistic relationship with them (Monteiro et al., 2019; Silva et al., 2021). This species holds particular scientific interest given its ecological role as specialist, occupying a specific dietary niche and living in a restricted geographic location. Recently, scientists have considered the predator/prey pair B. stephanieae/E. diaphana as a good model for the study of cascading effects of MHWs and bleaching on trophic interactions, research topics that remain largely understudied (Silva et al., 2023).

The present work focuses on this predator/prey model B. stephanieae/E. diaphana to shed light on the intra-specific variability of thermal tolerance and heat tolerance plasticity of the nudibranch B. stephanieae, throughout its life cycle. Here we used a laboratory bred B. stephanieae community (7th generation) to establish baseline upper thermal limits across different life stages of this nudibranch. Subsequently, we tested if exposure of B. stephanieae to a marine heatwave, the bleaching of its prey (E. diaphana), as well as the combination of both these factors impacts its upper thermal limit. These treatments aimed to mimic the occurrence of a MHW in B. stephanieae’s habitat, and associated bleaching events, which would ultimately shift the nutritional profile of its prey (E. diaphana) (Leal et al., 2012). This added nutritional stress may hold particular importance for stenophagous species, particularly at tropical shallow-water habitats, as these can act as ecological traps during MHWs, compromising the survival of coastal organisms (Vinagre et al., 2018, 2019). In general, mollusc’s early ontogenetic stages have higher thermal tolerance than later ones (Diederich and Pechenik, 2013; Peck et al., 2013). As such, we hypothesize that: (1) embryos of B. stephanieae will have the highest thermal tolerance, when compared to juveniles and adults and that (2) the effect of a MHW combined with feeding on bleached prey will impact the survival of this nudibranch and decrease its thermal tolerance. Such impact should be more pronounced on the adult stage, when compared to juveniles, given that adults partially digest their photosynthetic endosymbionts gaining some degree of energetic benefit from it, as opposed to juveniles that excrete these symbionts fully undigested (Borgstein et al., 2024). As these nudibranchs inhabit shallow waters, 1–2 m depth, they may be well adapted to temperature variations, but may live already close to their thermal limit. We anticipate that the combination of a MHW with a subpar nutritional regime will lead to a negative synergistic effect on this nudibranch. By addressing these hypotheses, we aim to provide new insights into the physiological limits of specialized predators under climate-induced stress, particularly MHWs.

The focus of this work on the ontogenetic plasticity within a highly specialized predator provides novel insights into the intricate interplay between developmental processes and environmental stress responses, a perspective that remains untaped in thermal biology.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Characterization of the thermal regime of B. stephanieae’s habitat

Berghia stephanieae’s habitat was defined according to this species description in MolluscDB database, from the northernmost point at 25.7 °N to the southernmost point on 25.09 °N, and the westernmost point at 80.44 °W to the easternmost point at 80.2 °W (Liu et al., 2021). Within this area, daily seawater potential temperature at a depth of 0.5 m was retrieved for the period from the 1st of January of 2005 to the 31st of December 2024. Data from the 1st of January of 2005 to the 31st of May 2022 was obtained from the Copernicus Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis dataset, while data from the 1st of June 2022 onward was sourced from the Copernicus Global Ocean Physics Analysis and Forecast dataset. The data was extracted and converted into CSV using R version 4.2.0 (R Core Team, 2021) with the help of R studio (RStudio Team, 2020), and the packages “ncdf4” (Pierce, 2010) and “lubridate” (Spinu et al., 2010). Lastly, this data set was concatenated using Microsoft Excel average and maximum seawater temperatures could be identified.

2.2 Exaiptasia diaphana monoclonal culture

A monoclonal community of Exaiptasia diaphana was produced with the protocol described by Silva et al. (2021). In short, a large adult specimen of this glass anemone species was isolated from a coral base it had colonized and placed in a 640-L life support system (LSS). This LSS consisted of two 260-L glass tanks (350 mm x 500 mm x 1500 mm) filled with seawater (salinity 35), collected from Ria de Aveiro, Portugal (40°38’18” N 8°43’43” W) at high tide. The tanks were kept under a 12 h light: 12 h dark photoperiod with an irradiance of roughly 70 μmol. photons. m−2. s−1 delivered by two ViparSpectra V165 LED. This anemone was fed daily with newly hatched Artemia sp. nauplii (Artemia Koral GmbH, Nürnberg, Germany) and otherwise kept to freely reproduce asexually through laceration of its basal peduncle. To keep ammonia, nitrates, nitrites, pH and salinity levels under recommended limits for marine invertebrates, partial water changes were performed, twice per week, totaling 20 % of total volume. The testing of these water parameters was performed using Tropic Marin colorimetric tests (Tropic Marin®, Wartenberg, Germany).

For the present experiment, roughly 800 glass anemones from this monoculture were used, distributed under two different sizes, small (<2 mm pedal diameter) and large (>5 mm pedal diameter). Bleaching was performed in 200 anemones (see section 3.4), 100 small and 100 large specimens, with the remaining 600 anemones (300 small and 300 large specimens) being kept symbiotic; 200 of these glass anemones (100 small and 100 large specimens) were employed during the experimental period, with the remaining 400 glass anemones (200 small and 200 large specimens) being used during the acclimation period to the experimental system.

2.3 Berghia stephanieae captive culture

A group of 30 small Berghia stephanieae adults were acquired from Tropical Marine Centre Iberia (Lisbon, Portugal) and sorted into fifteen breeding pairs. Each breeding pair was individually stocked and fed ad libitum with symbiotic E. diaphana. The nudibranchs were allowed to breed in a glass beaker with 1.2 L of artificial seawater (ASW), prepared by mixing fresh water purified by reverse osmosis (MO12000 E reverse osmosis from Ambietel – Tecnologias Ambientais LDA., Matosinhos, Portugal) with Red Sea Coral Pro Salt (Eilat, Israel) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to reach a salinity of 35. Each egg mass produced was removed from the glass beaker using a flexible plastic spatula, washed with autoclaved ASW (AASW) and transferred to a glass Petri dish (150 mm diameter and 30 mm high) with 100 mL of AASW for incubation and hatching at 26 °C. During the first 10 days of embryonic development, water changes using 10 % of AASW were performed daily on each Petri dish. This procedure was suspended on the day of expected hatching (day 11 post oviposition) to avoid losing newly hatched nudibranchs. At this time-point, juveniles were supplied ad libitum with small symbiotic anemones, daily. The fastest growing nudibranchs of each cohort were selected as new breeders and paired, while keeping inbreeding to a minimum and, as such, establishing a healthy broodstock of B. stephanieae.

In the present study, 7th generation laboratory-bred specimens were used. All specimens more than 12 mm long were considered as adults, while those smaller than 12 mm were considered as juveniles (Taraporevala et al., 2022). Egg masses were collected from the 6th generation parents.

2.4 Exaiptasia diaphana bleaching

Two hundred E. diaphana (100 small and 100 large specimens) from the monoclonal culture were selected to be bleached according to the menthol protocol described by Matthews et al. (2015). Briefly, menthol (Menthol (20 % w/v in ethanol) was added to ASW (prepared as described above) at a final concentration of 0.19 mmol.l-1), as well as Diuron® (DCMU (3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea) (100 mmol.l-1 in ethanol) at a final concentration of 5 µmol.l-1). The bleaching procedure consisted on keeping the anemones in a 12L:12D photoperiod, while incubating them in the menthol solution for 8 h (during the light period) followed by a 16 h incubation in ASW. This 24 h cycle was repeated four times, followed by a 3-day incubation of these anemones in a Diuron® solution. This process was repeated until glass anemones were considered bleached (visual identification with confirmation according to their Fv/Fm – mean ± SD of 0.433 ± 0.08; healthy threshold is 0.600 according to Warner and Suggett, 2016) (see Available data). During the bleaching protocol anemones were fed three times a week with newly hatched Artemia sp. nauplii.

2.5 Experimental set up

The impacts of MHW and consequent bleaching in the upper thermal tolerance limits and heat tolerance plasticity of B. stephanieae throughout its life cycle were tested using a fully factorial experimental design, with two independent variables (exposure to a MHW – (Temperature) – and bleaching of prey – (Food)), with two levels each, resulting in four treatments: 1) control temperature (27 °C) while feeding on symbiotic prey, treatment 27S (control); 2) MHW exposure (32 °C) while feeding on symbiotic prey, treatment 32S (thermal stress); 3) control temperature (27 °C) while feeding on bleached prey, treatment 27B (nutritional stress); and 4) MHW exposure (32 °C) while feeding on bleached prey, 32B (combined stress). The control temperature of 27 °C was selected based on the average sea surface temperature found in Florida coastal waters inhabited by B. stephanieae; MHW temperature (32 °C) was selected to simulate the worst MHW recorded in that region (Sanford et al., 2019; Androulidakis and Kourafalou, 2022). All four treatments were applied to specimens in their juvenile and adult stage, while only temperature treatments were applied to embryos, as these do not feed exogenously. Briefly, there were three different experimental systems according to each phase of the life cycle of B. stephanieae. Before the experiment started, specimens were acclimated to the experimental system for 14 days, at control temperature and fed with symbiotic anemones (with the exception of embryos, which do not feed and could not be acclimated due to the short time from oviposition to hatching).

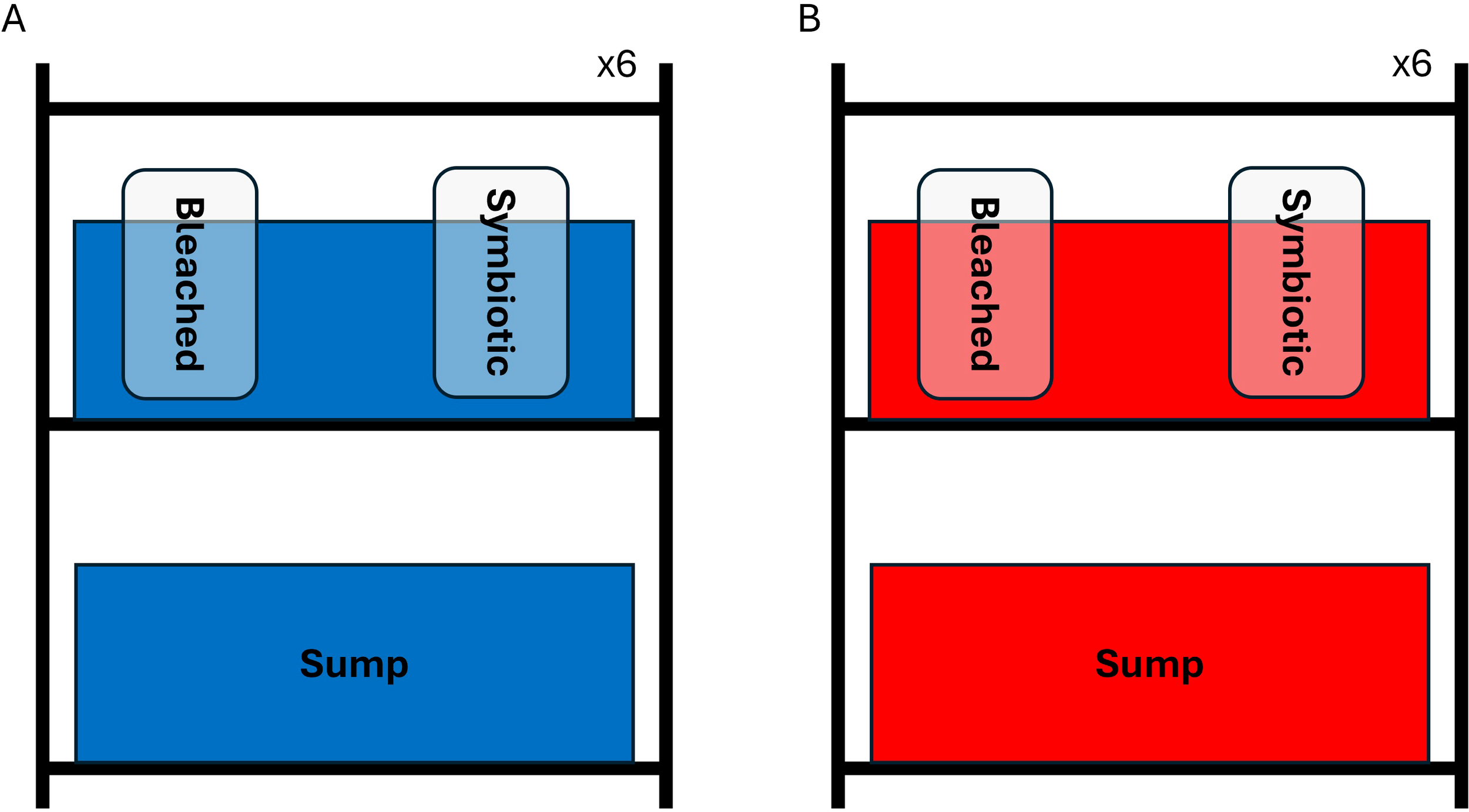

For adults, the experimental set up consisted of 12 shelf systems each containing two 40-L tanks filled with tap water to serve as a water bath for two 1.5 L mason jars filled with ASW (prepared as described above), and a 100-L tank to serve as a sump (Figure 1). Each mason jar housed a single B. stephanieae adult. Each jar was fed three times per week either symbiotic or bleached glass anemones, according to the “Food” treatment. To apply temperature treatments, each system was equipped with an Eheim Thermocontrol 150 W heater, for temperature maintenance. There were six replicate systems per temperature treatment (Figure 1). The sump was equipped with an Eheim 3200 pump, to recirculate the water bath, prevent stratification and ensure thermal homogeneity. After the acclimation period, a 7-day MHW (Androulidakis and Kourafalou, 2022) was simulated in treatments 32S and 32B, with temperature being increased at a rate of 1 °C. h-1 on day 0 and kept constant throughout the experiment (McLachlan et al., 2020). Temperature maintenance was checked and recorded using environmental loggers (Eletricblue, Oporto, Portugal) (see Available data). A total of twenty-four adults were used, totaling 6 replicates per treatment.

Figure 1

Schematic representation of the experimental system. Panel (A) refers to Berghia stephanieae kept at 27 °C, while panel (B) refers to specimens kept at 32 °C. Both systems featured two tanks, one on the bottom shelf serving as a sump, and one on the top shelf serving as water bath for two mason jars. Different types of food were provided to B. stephanieae housed on each jar, one of which is labelled as “Bleached” (bleached Exaiptasia diaphana), and the other as “Symbiotic” (symbiotic Exaiptasia diaphana). One single sea slug was housed per jar.

For juvenile B. stephanieae, a similar system was used to the one described for adults but featuring some slight changes. Briefly, juvenile specimens were housed in the same water bath, however they were held in 150 mL beakers, containing 100 mL of ASW, that were floated in the water bath with the help of an extruded polystyrene floater. The same number of replicates per treatment was used for this experiment (six, for a total of twenty-four juveniles).

As for embryos, egg masses were housed in Petri dishes (100 mm diameter 20 mm height) and floated in the same water baths. Each Petri dish was filled with 100 mL of AASW. A total of three egg masses were used per temperature treatment, one per water bath.

In all experiments, water was kept at a salinity of 36 ± 1 and a pH of 7.9 ± 0.1, with ammonia, nitrates and nitrites being kept below limit levels advised for marine invertebrates. Water quality was ensured through partial water changes of 50 % of the total volume, three times a week, with previously prepared ASW (see above), that had been pre-conditioned to the desired temperature (with the exception for egg masses). Water parameter testing was performed regularly to ensure water quality. Temperature and pH were checked daily using a multiparameter probe (Hanna HI9829, Hanna instruments, Bedfordshire, United Kingdom); salinity, ammonia, nitrates and nitrites were tested twice a week using Tropic Marin colorimetric tests (Tropical Marine Centre, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom).

On day 7, all replicates were used for upper thermal tolerance limit estimations and thermal safety margin assessment (see section 3.6 and 3.7). Cumulative survival was assessed at the end of the experiment, based on the number of organisms surviving per total number of organisms in each treatment.

2.6 Critical thermal maximum

Berghia stephanieae’s upper thermal tolerance limits were assessed using the dynamic method of the Critical Thermal Maximum (CTmax) developed by Mora and Ospína (2001) and adapted by Madeira et al. (2012a). Briefly, for adults, every nudibranch was collected and weighted to the nearest 0.01 mg on an analytical scale (Sartorius AG BCE224I-1SJP, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). Afterwards, each nudibranch was randomly placed in a 150-mL glass beaker (n = 1 individual per flask, ntotal = 19 adult B. stephanieae), filled with ASW (prepared as described above) and placed on a water bath (Grant Optima T100, Grant instruments, Cambridge, United Kingdom). The nudibranchs exposed to a control temperature were added to the beakers at temperature of 27 °C, whilst the ones who were exposed to the MHW were only added to the system when the water temperature reached 32 °C. Water bath temperature was raised at a rate of 2 °C.h-1, as this rate mimics environmental conditions that occur in intertidal areas (Missionário et al., 2022). Nudibranchs were kept under constant observation, using a LEICA S3AP0 microscope (LEICA, Wetzlar, Germany), to identify any physiological or behavioral shift caused by heat exposure (e.g. curled mantel, loss of attachment) until CTmax was reached (heat induced coma, the point at which the nudibranch ceased all responses for being prodded in the rhinophores for two seconds) (Laetz et al., 2024). When CTmax was achieved, temperature in the beaker was registered and the nudibranchs were set aside, in a new water bath for recovery. For juveniles, the same system was used as for adults, with small adaptations, that is, the same water bath was used, but juveniles were randomly distributed, 1 per well in 5 separate 6-well plates (n = 1 individual per well, ntotal = 24 juvenile B. stephanieae), instead of using beakers. Every other experimental set-up was kept unchanged. As for embryos, given the impracticality and increased complexity of analyzing the egg mass in its entirety, individual embryos were extracted and processed separately.

Thus, each egg mass was disaggregated, and ten embryos were collected per egg mass. Afterwards, the same methodology was used as for juvenile B. stephanieae (n = 1 embryo per well, ntotal = 30 B. stephanieae embryos), with CTmax being recorded when embryo movement ceased (Cowan et al., 2023). Due to embryo mortality under marine heatwave conditions, embryo CTmax was only compared with control conditions of the remaining life stages.

CTmax for each treatment was calculated as the mean of all individuals, using the formula (Equation 1):

where CTmaxn represents the temperature at which the loss of response or cessation of movement was recorded for a given specimen, and n is the number of individuals assessed. Intraspecific variability in thermal tolerance was quantified using coefficients of variation (% CV), calculated as (Equation 2):

where SD is the standard deviation of CTmax values and Mean is the respective treatment average.

Survival post-CTmax assay was above 90 % for adults and 87.5 % for juveniles which is in accordance with the literature (survival should be above 90 % for most cases, Morgan et al., 2018). Post CTmax assay survival was not possible to account for embryos (see below).

2.7 Heat tolerance plasticity and thermal safety margins

Thermal safety margin (TSM) was calculated (Equation 3) for both juveniles and adults of B. stephanieae, in the various treatments, as the difference between the average CTmax value recorded within a given treatment and the maximum seawater temperature recorded within the species’ habitat range (as defined above) (Vinagre et al., 2019).

Moreover, heat tolerance plasticity was calculated following two metrics. The first was acclimation capacity, which is an absolute measure of heat tolerance plasticity, indicating how much the species’ thermal limits change regardless of how large the temperature difference was. It is estimated by comparing the CTmax of the marine heatwave group against the CTmax of the control group within each type of food and life stage (Equation 4):

The second metric was Acclimation Response Ratio (ARR),which is a standardized measure of heat tolerance plasticity, indicating how much the thermal limits change per degree of temperature change. It is calculated as the change in CTmax () divided by the change in acclimation temperature () (Equation 5):

An ARR value of 0 indicates a lack of plasticity, whereas a value of 1 represents complete physiological compensation for temperature increases. Negative values indicate that the species’ capacity to tolerate heat decreases under the tested treatments, suggesting a detrimental or maladaptive response.

Data from the experimental treatments using embryos were not used on these analyses due to the mortality levels recorded in the MHW treatment.

2.8 Statistical analysis

R software, version 4.2.0, on the RStudio integrated development environment, was used for statistical analysis and graphical representation (RStudio Team, 2020; R Core Team, 2021). All statistical analyses and interpretation of experimental results were performed using the “language of evidence” proposed by Muff et al. (2022). Evidence of effects is described following the range: 0.0001 < p < 0.001—very strong evidence; 0.001 < p < 0.01—strong evidence; 0.01 < p < 0.05—moderate evidence; 0.05 < p < 0.1 weak evidence; 0.1 < p < 1—little to no evidence. Data importation was performed using “readxl” package (Wickham and Bryan, 2025). Figures were created using packages “ggplot2”, “gghalves”, “ggridges”, and “ggtext” (Wickham, 2016; Wilke, 2017; Tiedemann, 2019; Wilke and Wiernik, 2020). Tables and summary statistics were produced with packages “dplyr”, “broom”, “broom.mixed”, and “gt” (Robinson et al., 2014; Bolker and Robinson, 2018; Wickham et al., 2023; Iannone et al., 2025). Differences in survival among treatments were assessed using Fisher’s exact test to perform pairwise comparisons followed by Bonferroni correction for multiple pairwise comparisons. As for CTmax data, all tests were preceded by normality testing of data, using a Shapiro-Wilk’s normality test (to verify normality of distribution) and a graphical residual diagnostics.

Concerning CTmax data for embryos, as only a baseline estimation at control temperature was performed (due to high mortality levels under MHW), a model analysis was employed to compare baseline thermal tolerance across all life stages under optimal conditions (control temperature and control feeding, in case of juveniles and adults). For that, a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) was fitted using glmmTMB package (McGillycuddy et al., 2025), with life stage as a fixed effect and egg mass as a random intercept, so that each individual embryo could be nested in the respective egg mass. Subsequently, simulation-based residuals were used to assess model diagnostics, using the DHARMa package (Hartig, 2016) with scaled residuals showing no significant deviations from expected distributions, no evidence of dispersion issues (dispersion = 1.04, p = 0.8), and no outliers detected. Afterwards, post-hoc comparisons were performed using Tukey’s HSD tests to compare the CTmax of different life stages of B. stephanieae under optimal conditions. Effect size was calculated through Cohen’s D using the “effsize” package (Torchiano, 2013).

Due to the lack of normality of distribution and the right-skewness of the data, Generalized Linear Models (GLM) assuming a Gamma distribution for the data, using the logarithmic link function, were employed to model the CTmax data of adults and juveniles. Briefly, life stage, temperature and food were used as fixed factors, and the effect of weight was tested by including or excluding it as a covariate in the model, based on centered weight, following the formula (Equation 6):

Where is the centred weight of a sample, is the original weight of said sample and is the average weight of the sample’s life stage.

Confirmation of the model fit was obtained through residual inspection and AIC comparison against different models. Additionally, weight effects were evaluated using a Type III ANOVA (comparing life stages and treatments) and Spearman’s correlation test (to test for correlations within life stages and treatments).

3 Results

3.1 Thermal regime of B. stephanieae’s habitat

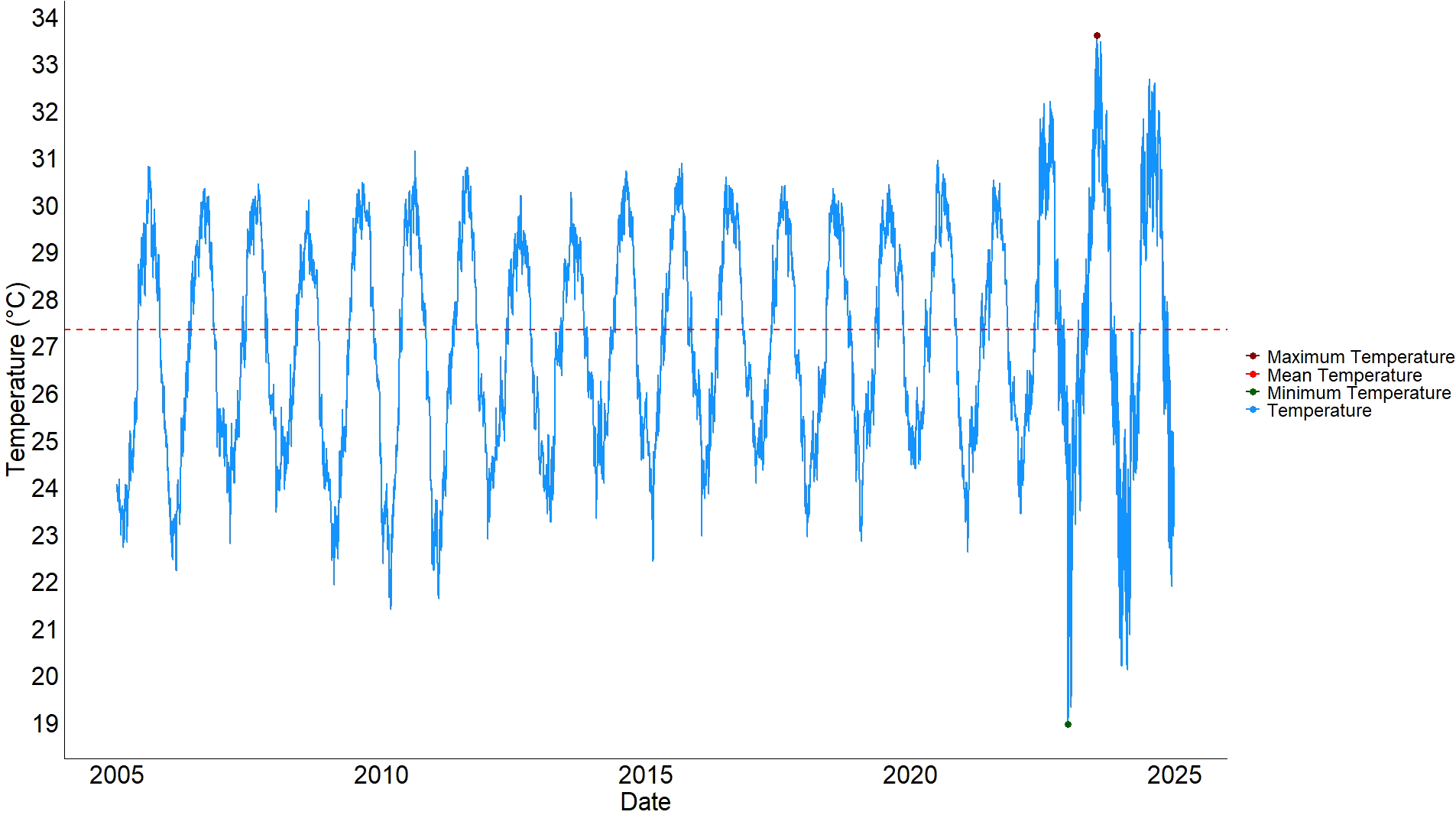

The analysis of seawater surface temperature of the habitat of B. stephanieae, as defined by MolluscDB, revealed a high thermal variability over the 20-year period surveyed (from January 1st, 2005 to December 31st, 2024). In this period, daily temperature at 0.5 m depth averaged at 27.3 °C, with the maximum recorded temperature being found on the 13th of July, at 33.6 °C (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Thermal regime of Berghia stephanieae’s natural habitat. Temperature data obtained from Copernicus and span from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2024, at a depth of 0.5 meters. The dark red point represents the highest recorded temperature, the dark green point represents the lowest, and the red dotted line indicates the average temperature over the period.

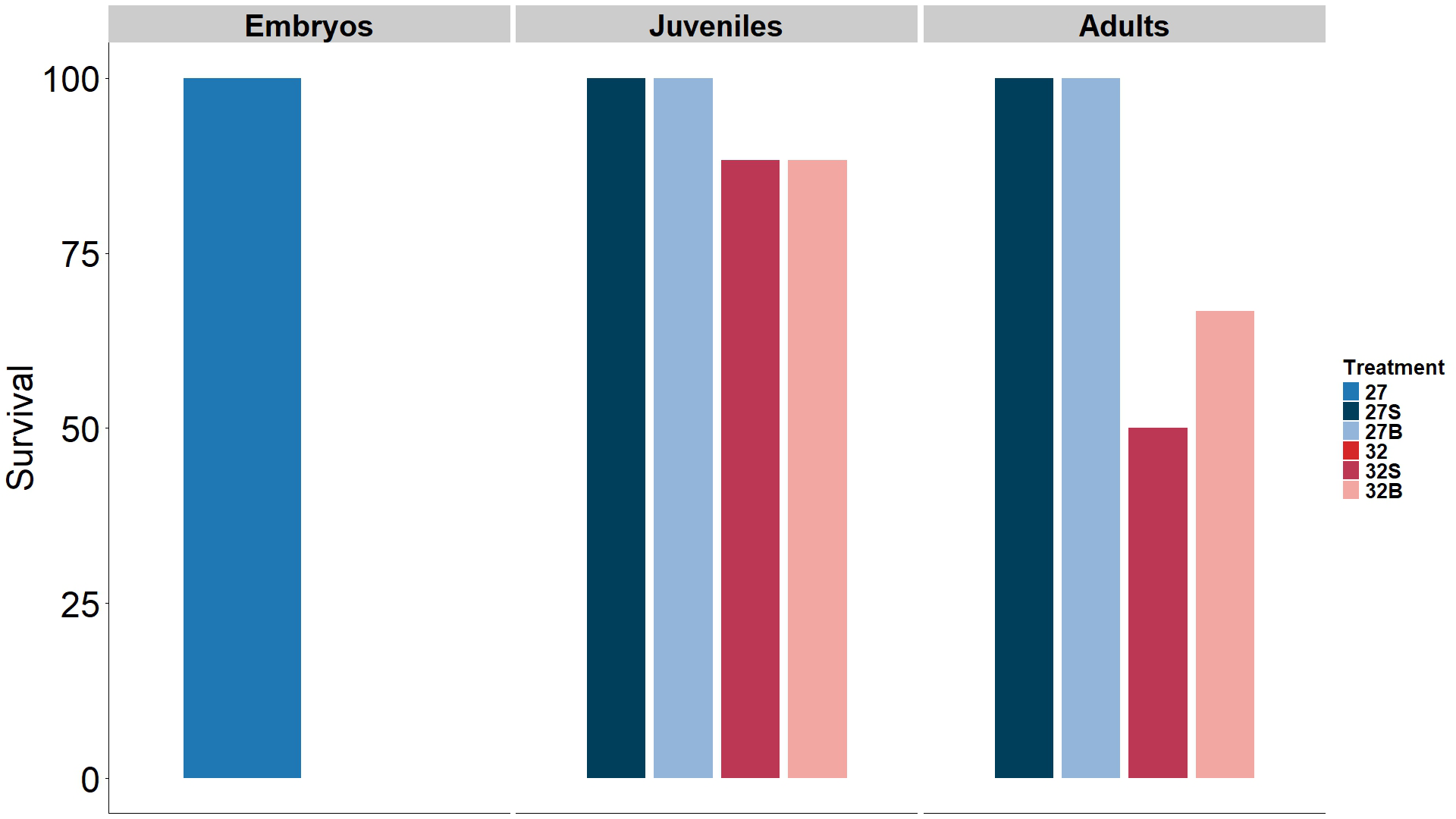

3.2 Survival

Acclimation to the experimental system was successful, with 100 % nudibranch survival. Following the experimental period, no significant differences between any of the tested groups was found on the survival of B. stephanieae (little to no evidence of effect with p > 0.1) (see Available data). During the experiment, all individuals maintained under control temperature (27 °C) survived, regardless of life stage or food source. Despite the lack of statistically significant differences, a trend of decreasing survival was observed under marine heatwave conditions (32 °C). Among adult nudibranchs, the lowest survival was recorded in those exposed to MHW only (32S), with only three out of six (50 %) surviving until the end of the experimental period. Under combined stress (32B) a slightly higher survival was found, with four adult nudibranchs (66.7 %) surviving. As for juvenile nudibranchs, both treatments where a MHW was simulated (32B and 32S) lost one individual (83.3 %). Lastly, all the embryos of the egg masses under a MHW were dead by the fourth day of exposure (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Survival of different life stages of Berghia stephanieae at the end of a 7-day marine heatwave experiment with bleaching of its prey Exaiptasia diaphana. 27S – control temperature (27 °C) and symbiotic prey, 32S – marine heatwave (32 °C) and symbiotic prey, 27B – control temperature and bleached prey, 32B – marine heatwave and bleached prey – all with an n of six nudibranchs); 27 and 32 refers to Berghia stephanieae embryos (n = 30) that were exposed to control temperature and marine heatwave, respectively, with no food treatment has they have no exogenous feeding.

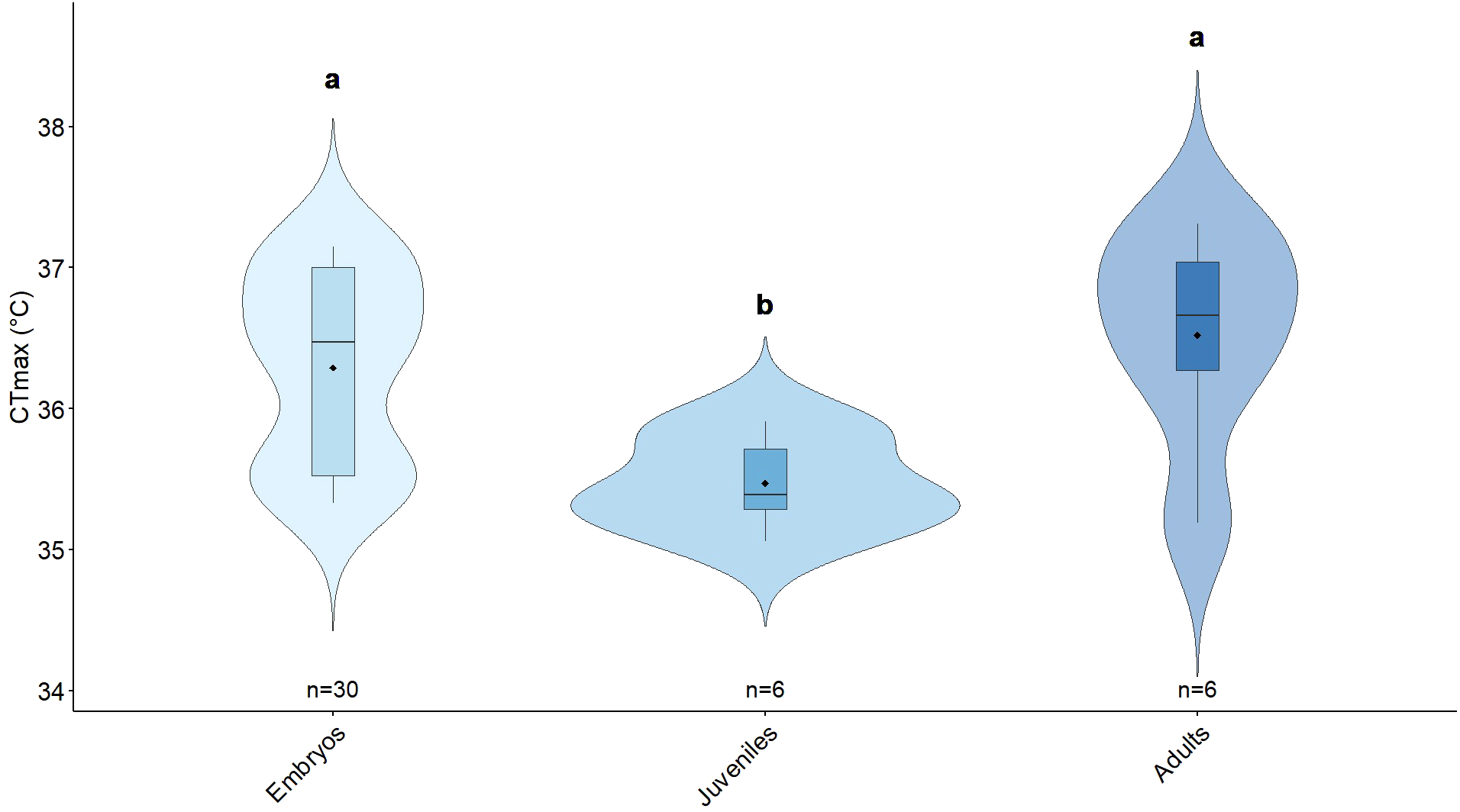

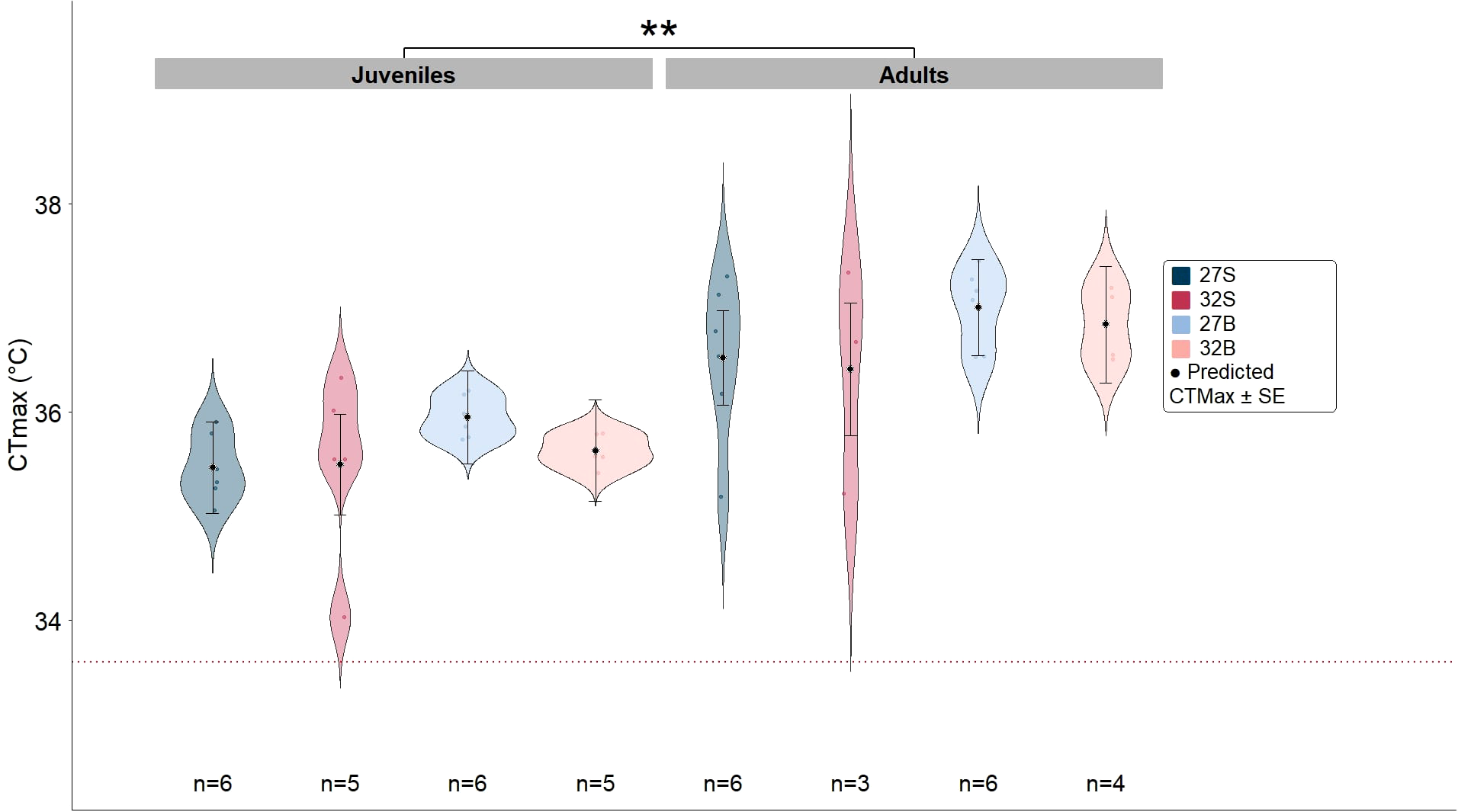

3.3 Berghia stephanieae thermal tolerance

Significant differences were found in baseline thermal tolerance (CTmax) of Berghia stephanieae across all life stages. Adults had the highest average CTmax (36.52 ± 0.77 °C), followed by embryos (36.29 ± 0.66 °C), and juveniles (35.47 ± 0.33 °C) (Figure 4). Differences were found between juveniles’ CTmax and both embryos’ and adults’ CTmax (moderate evidence of effect with p=0.016 in both cases, Cohen’s D = -1.309 and -1.783 respectively) (Table 1).

Figure 4

Violin plots showing the critical thermal maximum (CTmax) of Berghia stephanieae across different life stages under optimal conditions (27 °C and feeding on symbiotic prey). The black dot represents the mean CTmax. The embedded boxplot displays the median (center line), 25th percentile (lower hinge), and 75th percentile (upper hinge). The sample size is displayed under each life stage plot. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences.

Table 1

| Life stage | Estimate | Standard error | Statistic | Adjusted p-value | Cohen’s D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryos – Adults | -0.006 | 0.008 | -0.763 | 0.721 | 0.339 |

| Juveniles – Adults | -0.029 | 0.011 | -2.742 | 0.016 | -1.783 |

| Juveniles - Embryos | -0.023 | 0.008 | -2.745 | 0.016 | -1.309 |

Tukey’s post-hoc tests results comparing critical thermal maximum (CTmax) among life stages of Berghia stephanieae and their effect sizes.

Statistical significance is indicated in bold lettering.

Concerning the CTmax of juveniles and adults across the different feeding and temperature treatments, little to no evidence of interaction between factors was found. As for main effects, only life stage impacted the CTmax of B. stephanieae (very strong evidence of effect, p=0.005), with juveniles having a 2.8 % lower CTmax when compared to adult B. stephanieae (Figure 5, Table 2). The factors “Food” and “Temperature” did not influence the CTmax of nudibranchs (little to no evidence of effect, p=0.811 and p=0.104, respectively). There is weak evidence for the influence of the covariate “Weight” on CTmax (p = 0.087). Accordingly, we found little to no evidence of a significant correlation between individual weight and CTmax for both juveniles and adults (p = 0.52 and p= 0.88 correspondingly) (Table 3).

Figure 5

Violin plots showing the critical thermal maximum (CTmax) of Berghia stephanieae juveniles and adults under different temperature and food treatment conditions (27S – control temperature (27 °C) and symbiotic prey, 32S – marine heatwave (32 °C) and symbiotic prey, 27B – control temperature and bleached prey, 32B – marine heatwave and bleached prey). Black dots represent model-predicted CTmax values, with whiskers indicating the standard error. Statistically significant differences are denoted by “**” (p = 0.01). The sample size is displayed under each treatment plot. The red dotted line indicates maximum B. stephanieae habitat temperature (33.6 °C).

Table 2

| Term | Estimate (exp) | 95 % CI (lower) | 95 % CI (upper) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 36.450 | 36.006 | 36.901 | 0.000 |

| Life stage: Juveniles | 0.974 | 0.957 | 0.991 | 0.005 |

| Temperature: Marine heatwave (MHW) | 0.997 | 0.977 | 1.019 | 0.811 |

| Food: Bleached | 1.015 | 0.997 | 1.032 | 0.104 |

| Weight | 1.182 | 0.981 | 1.422 | 0.087 |

| Life stage: Juveniles x Temperature: MHW | 1.001 | 0.973 | 1.029 | 0.965 |

| Life stage: Juveniles x Food: Bleached | 0.999 | 0.975 | 1.024 | 0.942 |

| Temperature: MHW x Food: Bleached | 1.004 | 0.975 | 1.033 | 0.809 |

| Life stage: Juveniles x Temperature: MHW x Food: Bleached | 0.989 | 0.952 | 1.028 | 0.580 |

Exponentiated coefficients (with 95 % confidence intervals) from a generalized linear model (GLM) examining the effects of life stage, temperature and food factors and their interactions on Berghia stephanieae’s critical thermal maximum (CTmax).

Estimates represent multiplicative changes in expected CTmax relative to the reference category for each factor (“Adult” for life stage, “Symbiotic” for food and “Control” for temperature). Weight has been centered for each life stage (“Juvenile” and “Adult”). P-values correspond to Wald tests for each coefficient. Statistical significance is indicated in bold lettering.

Table 3

| Life stage | rho | p-value | S |

|---|---|---|---|

| Juveniles | -0.1451978 | 0.5191119 | 2028.145 |

| Adults | 0.0359807 | 0.8837356 | 1098.982 |

Results of Spearman correlation tests evaluating the relationship between individual body weight and critical thermal maximum (CTmax) in juveniles and adults of Berghia stephanieae.

3.4 Heat tolerance plasticity and thermal safety margins

Both acclimation response ratio (ARR) and acclimation capacity for B. stephanieae revealed negligible plastic responses across all treatment groups (ARR ranged: −0.08 to +0.01 °C, and acclimation capacity ranged: -0.323 to 0.026) (Table 4).

Table 4

| Life stage | Food | Control CTmax (°C) | MHW CTmax (°C) | Acclimation capacity | Acclimation response ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juveniles | Symbiotic | 35.47 | 35.50 | 0.026 | 0.0065 |

| Juveniles | Bleached | 35.96 | 35.63 | -0.323 | -0.0808 |

| Adults | Symbiotic | 36.52 | 36.41 | -0.108 | -0.0271 |

| Adults | Bleached | 37.01 | 36.84 | -0.166 | -0.0415 |

Acclimation capacity and acclimation response ratio of different Berghia stephanieae life stages (juveniles and adults) food treatments and their respective critical thermal maximums (CTmax) under both temperature treatments.

As for thermal safety margins (TSM), they ranged from 1.87 to 3.4 °C across treatments (Table 5). The highest TSM was found in adults fed bleached prey under control temperature, while the lowest one was found in juveniles fed symbiotic prey under marine heatwave conditions.

Table 5

| Life stage | Food | Control CTmax (°C) | MHW CTmax (°C) | TSM Control (°C) | TSM MHW (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryos | NA | 36.29 | NA | 2.69 | NA |

| Juveniles | Symbiotic | 35.47 | 35.50 | 1.87 | 1.90 |

| Juveniles | Bleached | 35.96 | 35.63 | 2.36 | 2.03 |

| Adults | Symbiotic | 36.52 | 36.41 | 2.92 | 2.81 |

| Adults | Bleached | 37.01 | 36.84 | 3.41 | 3.24 |

Thermal safety margins (TSM) of different Berghia stephanieae life stages under the different treatments as respective critical thermal maximums (CTmax), considering the maximum habitat temperature of 33.6 °C, registered in this species’ habitat.

4 Discussion

Our study provides compelling evidence for life-stage–specific thermal tolerance in the specialist nudibranch B. stephanieae, highlighting the occurrence of ontogenetic variation in thermal sensitivity within this species. Under optimal stocking conditions, juveniles displayed the lowest upper thermal limits, while embryos and adults had higher thermal tolerance comparable between them. Such results support the idea that different life-stages have different thermal strategies or physiological limits, as observed in other taxa such as gastropods (Diederich and Pechenik, 2013; Truebano et al., 2018), bivalves (Peck et al., 2013; Delorme et al., 2024), holothurians, echinoids, asteroids (Peck et al., 2013) and marine and freshwater fish (Dahlke et al., 2020). However, while early life stages (i.e. embryos and larvae) usually display lower thermal tolerance in many marine ectotherms (Madeira et al., 2012a; Truebano et al., 2018; Dahlke et al., 2020; Collin et al., 2021), the opposite pattern has been observed in some marine invertebrates, including gastropods (Diederich and Pechenik, 2013), bivalves, holothurians, echinoids and asteroids (Peck et al., 2013), where early ontogenetic stages seem to display a higher thermal tolerance than later life-stages. Our results seem to fit this observation. These differences between CTmax of different life stages may reflect ontogenetic shifts in energy allocation, membrane stability, or expression of heat shock proteins (Truebano et al., 2018; Madeira et al., 2020). In this work juveniles displayed the lowest CTmax, which may be due to their higher energetic consumption for somatic growth (Deaker and Byrne, 2022; Pettersen et al., 2022). This finding does contrast with what could be expected from the literature, as, generally, embryos tend to be less resilient (Pottier et al., 2022). Under shifting environmental regimes, the ability to survive may depend on the level of phenotypic plasticity. In this study, neither food nor thermal regime impacted upper thermal tolerance limits of feeding stages (juveniles and adults), suggesting limited heat tolerance plasticity, possibly explaining decreased survival outcomes. Similarly, high temperature strongly reduced the survival of embryos, highlighting their sensitivity to shifting environmental conditions. Overall, our results emphasize the relevance of estimating tolerance limits across life-cycle stages and pinpoint the lack of plasticity of thermal tolerance limits in this nudibranch species.

Although our small sample size limits statistical resolution, the survival observed provides an important context for interpreting the non-plastic CTmax values in B. stephanieae. While all individuals survived under control temperature conditions (27 °C), the exposure to MHW (32 °C) led to a decreasing trend in survival, particularly among adults and embryos. This suggests that although CTmax did not significantly change, the energetic and physiological burden imposed by MHW exposure was sufficient to cause death. This may be the result of sublethal effects of thermal stress, such as the disruption of routine metabolic function, cellular membrane structure damage, metabolic depression or reactive oxygen species formation, culminating in reduced long-term survival (Long and Daly, 2017; Viladrich et al., 2022). We must also note that CTmax was only measured in surviving individuals, hence the most resistant ones, potentially leading to an overestimation of thermal tolerance. The negative impacts of heat have been widely reported in marine ectotherms, where chronic exposure to elevated temperatures impairs fitness even in the absence of CTmax shifts (Sokolova et al., 2012; Pörtner et al., 2017). Interestingly, juveniles showed the highest survival, a result that aligns with previous studies on invertebrates (Peck et al., 2009). This pattern may be attributed to differences in metabolic requirements or enhanced cellular turnover rates at this stage (Deaker and Byrne, 2022; Pettersen et al., 2022). Most impressive was the fact that all embryos failed to survive beyond four days of MHW exposure, highlighting the extreme vulnerability of early ontogenetic stages to thermal stress, already reported in other marine invertebrates (Przeslawski et al., 2015; Pandori and Sorte, 2019; Deschamps et al., 2025). This recorded mortality of embryos in the MHW treatment made direct comparisons with other life stages exposed to stress impossible, as their CTmax estimates were obtained exclusively under control temperature conditions. Moreover, such results may reflect the ability of embryos to tolerate brief, acute thermal exposures but not compounded stress lasting for several days Developmental processes are known to be highly thermosensitive, with high temperatures leading to malformations and death in many taxa (Przeslawski, 2004; Liu et al., 2023). This might be due to the reduced cellular and molecular defenses of embryos (Przeslawski, 2004), or abnormal expression of autophagy or apoptosis related genes (Liu et al., 2023) rendering them more vulnerable to sustained high temperatures. Additionally, one must note that the mechanisms, exposure time and energy costs/trade-offs underpinning acute (e.g. CTmax) and chronic assays (e.g. specific treatments of a certain duration) may differ (Bates and Morley, 2020). While the CTmax assay is based on an “exponential accumulation of heat stress over time” (Ern et al., 2023) and is thought to result from heat-induced neural dysfunction (Jørgensen et al., 2020; Andreassen et al., 2022), survival outcomes of a specific treatment may derive from a linear accumulation of heat stress throughout a determined amount of time. In this case, accumulated cellular injury or energetic costs could play a role in defining survival outcomes (Madeira et al., 2020). If this heat stress surpasses the critical temperature for acclimation, then mortality is expected (see Ern et al., 2023). This discrepancy between acute thermal limits, and survival to longer periods of thermal stress is a strong indicator of the vulnerability of early life stages to chronic exposure, something that has been observed in various marine invertebrate early life stages, mainly coral and molluscan embryos (Gosselin and Qian, 1997; Byrne, 2011; Przeslawski et al., 2015; Pandori and Sorte, 2019; Oliveira et al., 2020; Czaja et al., 2023). As such, the assessment of CTmax alone may underestimate the true vulnerability of earlier life stages of marine invertebrates. Still, natural thermal variability (e.g. daily variability) might be an important factor to consider in future experimental designs, as evidence suggests that species responses may differ between stable and variable temperature treatments (Bates and Morley, 2020).

Despite B. stephanieae showing clear ontogenetic differences on its CTmax, our results revealed no significant differences among treatment groups, both according to thermal condition, prey condition or even their interaction. These results suggest that short-term exposure to thermal or dietary stress does not alter the acute upper thermal limits of B. stephanieae. This stability indicates that this nudibranch lacks heat tolerance plasticity, so its ability to withstand heat stress cannot be further adjusted. This finding is further supported by the very low acclimation capacity and minimal ARR recorded across all tested treatments. One could also argue that the MHW treatment tested here, even though ecologically relevant, did not surpass the organism’s short-term acclimatory threshold, or that its duration was insufficient to trigger measurable plasticity (Gunderson and Stillman, 2015). In fact, acclimation responses are known to vary substantially in ectotherms (Morley et al., 2019), with limited thermal tolerance plasticity being commonly observed in intertidal species with inherently high baseline thermal tolerance (Stillman, 2003), particularly among tropical ectotherms (Gunderson and Stillman, 2015; Vinagre et al., 2016). Even though nudibranchs show one of the highest heat tolerance plasticity within marine ectotherms, previous studies have found that acclimation to thermal stress in this group occurs within an average of four weeks (Armstrong et al., 2019), far exceeding our exposure period. However, low heat tolerance plasticity is commonly reported for other eurythermal or intertidal species, such as Petrolishtes crabs, which were found to have a trade-off between having a higher thermal tolerance at the cost of having a lower acclimation capacity (Stillman, 2003). Several other intertidal decapod crustaceans and fishes follow the same trade-off pattern, where tropical species show higher CTmax, although lacking the plasticity to acclimate to warming scenarios (Vinagre et al., 2016). This low plasticity may reflect trade-offs between heat shock response and other energetically demanding processes, such as immune function and cellular repair (Kültz, 2005; Collins et al., 2023; Diaz De Villegas et al., 2024). This energetic trade-off would be particularly relevant when the organisms are subjected to nutritional stress, as well as thermal stress (Fitzgerald-Dehoog et al., 2012). However, our data shows no significant interaction between these stressors, refuting the hypothesis of negative synergistic responses in upper thermal limits.

Regarding our expectation that dietary stress would impair thermal tolerance, this was based on prior studies demonstrating that reduced energy availability can limit the organism’s capacity to mount effective stress responses (Sokolova et al., 2012; Pörtner et al., 2017). This is the case, for instance, for Acartia tonsa, where three days starvation leads to a significant decrease in CTmax (Rueda Moreno and Sasaki, 2023). In fact, ectotherms thermal limits may be effected by their diet quality (i.e. macronutrient and micronutrient composition) (Hardison and Eliason, 2024). Assuming that bleached prey provides poorer nutrition to the nudibranchs, due to a poorer fatty acid profile, as reported by Leal et al. (2012), we expected their CTmax to be lower. However, this was not the case, suggesting that food quality may not be a major factor modulating upper thermal limits for B. stephanieae. The lack of interaction between factors “temperature” and “food” also indicates that the response to temperature is independent of prey condition and vice-versa.

Lastly, the TSMs found in our work were slim, with the highest being 3.47 °C. This result indicates that B. stephanieae’s habitat temperatures are reaching this nudibranch’s thermal limit. Similar TSM have been reported in intertidal organisms experiencing sublethal or lethal effects during MHW events (Madeira et al., 2012b; Missionário et al., 2022; Fernandes et al., 2023). However, when compared to tropical intertidal species TSM, the one found in this work is much lower, thus highlighting this species vulnerability (Vinagre et al., 2019b). This is particularly concerning when considering the thermal regime of tropical tidepools, in which temperatures can easily exceed the upper thermal limits of most tropical coastal species (Vinagre et al., 2018). Moreover, the fact that these TSM are so narrow highlights the importance of evaluating, not only the tolerance limits of an organism, but also the thermal regime and history of its habitat. Moreover, the lowest TSMs in B. stephanieae were recorded for its juvenile stage. That, together with the fact that embryos under MHW were unable to develop and hatch, showcases the sensitivity of B. stephanieae populations to MHWs coinciding with reproductive periods, that will inevitably reduce recruitment in this species. Adding to this, intraspecific variation in CTmax was low (coefficient of variation ranging from 0.45 to 2.98 % (see Available data)), a result that is comparable to those recorded for other marine invertebrates and fish (Madeira et al., 2012b; Vinagre et al., 2016). Even though this consistency may enable species-level predictions, it also supports limited standing genetic variation in thermal tolerance, that may hinder evolutionary responses to rapid environmental change (Shaw et al., 2013; Bennett et al., 2018). However, one must consider that our study used laboratory-bred individuals, from the 7th in-house-bred generation, from two original populations. Even though there was an effort to limit inbreeding, our specimens are still highly acclimated to laboratory conditions, i.e. highly stable water temperatures and, as such, likely less tolerant to such shifts than wild conspecifics. Indeed, these captive-bred individuals may differ from wild conspecifics due to factors such as genetic drift, relaxed selective pressures, and controlled environmental conditions (Turko et al., 2023). These differences may influence the thermal limits studied in this work, warranting a careful interpretation and extrapolation of results to natural populations. Nonetheless, one must recall that while laboratory experiments offer controlled settings for mechanistic insights, they inevitably lack the complexity and environmental realism of natural habitats, where multiple interacting factors shape fitness and survival (Turko et al., 2023).

In this study the bleaching of E. diaphana was accomplished using the protocol described by Matthews et al. (2015). that achieves bleaching using menthol as a chemical stressor. This approach achieves bleaching through a different molecular pathway than that of hyperthermal induced bleaching (Dani et al., 2016). studies have found that, in the snakelocks anemone Anemonia viridis, heat stress induces bleaching through the expulsion of damaged endosymbionts and the simultaneous death of both the endosymbiont and the host cell through apoptosis (Dani et al., 2016). Conversely, the same study found that the most prevalent pathway through which menthol stress induces bleaching is through symbiophagy (Dani et al., 2016). Furthermore, Matthews et al. (2015) found that when comparing menthol induced bleaching with cold induced bleaching, a much higher effectiveness was achieved when bleaching was achieved using menthol as a stressor, with higher survival rates and enabling recovery of the bleached organism on the long term. Therefore, while using menthol as the stressor to induce bleaching may limit the ecological interpretation of our findings, it limits the risks of experimental failure.

Here we show that even though B. stephanieae’s upper thermal tolerance limits differ between life stages, all stages display limited plasticity, with particularly poor survival outcomes in early ontogenetic stages, under MHW conditions. These results emphasize the high vulnerability of this species to future climate extremes. Indeed, this vulnerability is emphasized as recent evidence shows that this species home range is warming up at rates much higher than global ocean average (Shi and Hu, 2023). Moreover, over the last 40 years, Florida has been subjected for a continuous trend of MHW intensification (total number of MHW days increased by 7.4 days/decade and the frequency of individual MHW events increased by 0.75 events/decade) (Androulidakis and Kourafalou, 2022). As such B. stephanieae’s resilience may be threatened under future climate scenarios, due to it being a specialist nudibranch, with a narrow geographic distribution, occupying shallow and highly thermally variable habitats. The loss of this specialized organism may unlock unknown cascading effects on local biodiversity and ecosystem functioning, due to their unique ecological roles and stenophagous feeding habits. Indeed, the loss of predators, has diverse ecological consequences, with the disruption of food webs being one of the most studied, due to the loss of regulation of prey population, causing a cascade of ecological effects resulting in the loss of ecosystem functions and services (Fortuna et al., 2024).

Even though there is a limitation posed by the low replication of certain experimental components, particularly for embryo CTmax assays and specific survival assessment, the data generated in this work offers meaningful evidence on the thermal tolerance plasticity, or lack thereof, of B. stephanieae different life-cycle stages, when exposed to thermal and nutritional stress. This provides a valuable foundation for future research that should account for an enhanced level of replication and a broader experimental scope. Overall, the limited level of replication of our study may somehow constrain the statistical robustness of our findings, which warrants cautious interpretation of these specific results and should impair generalizations. Future works should therefore delve deeper into chronic stresses and transgenerational effects, particularly under multi-stressor scenarios. Assessing wild populations is also of paramount importance, as most studies to date have focused on lab-grown individuals. Understanding the ecological context and real-world vulnerabilities of B. stephanieae and other highly specialized marine invertebrates is crucial for predicting their persistence and the stability of their ecosystems under ongoing climate change.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15967722.

Author contributions

RS: Visualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RC: Methodology, Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition. DM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) funded RS through a Ph.D. grant (2021.05303.BD, DOI: https://doi.org/10.54499/2021.05303.BD) and DM through a researcher contract (DM: CEECIND/00153/2022, DOI: https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.00153.CEECIND/CP1720/CT0016). This work was funded by national funds through FCT – Fundaçao para a Ciência e a Tecnologia I.P., under the projects CESAM - Centro de Estudos do Ambiente e do Mar, references UID/50017/2025 (doi.org/10.54499/UID/50017/2025) and LA/P/0094/2020 (doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0094/2020). This work was developed under the incentive line “Agendas for Business Innovation” within Component 5, Capitalization and Business Innovation of the Portuguese Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), specifically under the transversal WP9, Portuguese Blue Biobank that was co-funded by Next Generation EU European under the project “BLUE BIOECONOMY PACT” (Project N°. C644915664-00000026).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work the authors used OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4o to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abdelnour S. A. Naiel M. A. E. Said M. B. Alnajeebi A. M. Nasr F. A. Al-Doaiss A. A. et al . (2024). Environmental epigenetics: Exploring phenotypic plasticity and transgenerational adaptation in fish. Environ. Res.252, 118799. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.118799

2

Andreassen A. H. Hall P. Khatibzadeh P. Jutfelt F. Kermen F. (2022). Brain dysfunction during warming is linked to oxygen limitation in larval zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.119, e2207052119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2207052119

3

Androulidakis Y. S. Kourafalou V. (2022). Marine heat waves over natural and urban coastal environments of South Florida. Water14, 3840. doi: 10.3390/w14233840

4

Armstrong E. J. Tanner R. L. Stillman J. H. (2019). High heat tolerance is negatively correlated with heat tolerance plasticity in nudibranch mollusks. Physiol. Biochem. Zoology92, 430–444. doi: 10.1086/704519

5

Asch R. G. Stock C. A. Sarmiento J. L. (2019). Climate change impacts on mismatches between phytoplankton blooms and fish spawning phenology. Global Change Biol.25, 2544–2559. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14650

6

Banger D. (2011). Breeding Berghia nudibranches: The best kept secret (CreateSpace Independent Publishing, North Charleston, S.C. , U.S.A.: Dene Banger).

7

Bates A. E. Morley S. A. (2020). Interpreting empirical estimates of experimentally derived physiological and biological thermal limits in ectotherms. Can. J. Zool.98, 237–244. doi: 10.1139/cjz-2018-0276

8

Bennett J. M. Calosi P. Clusella-Trullas S. Martínez B. Sunday J. Algar A. C. et al . (2018). GlobTherm, a global database on thermal tolerances for aquatic and terrestrial organisms. Sci. Data5, 180022. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.22

9

Bolker B. Robinson D. (2018). broom.mixed: Tidying methods for mixed models. 0.2.9.6. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.broom.mixed

10

Borgstein N. M. van der Meij S. E. T. Christa G. Laetz E. M. J. (2024). Potential energetic and oxygenic benefits to unstable photosymbiosis in the cladobranch slug, Berghia stephanieae (Nudibranchia, Aeolidiidae). Mar. Biol. Res.20, 45–58. doi: 10.1080/17451000.2024.2312908

11

Byrne M. (2011). “ Impact of ocean warming and ocean acidification on marine invertebrate life history stages: Vulnerabilities and potential for persistence in a changing ocean,” in Oceanography and marine biology: an annual review. Ed. GibsonR. N. ( Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton London New York), 1–42. Available online at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/b11009-3/impact-ocean-warming-ocean-acidication-marine-invertebrate-life-history-stages-vulnerabilities-potential-persistence-changing-ocean-maria-byrne (Accessed September 15, 2025).

12

Byrne M. Foo S. A. Ross P. M. Putnam H. M. (2020). Limitations of cross- and multigenerational plasticity for marine invertebrates faced with global climate change. Global Change Biol.26, 80–102. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14882

13

Canale C. Henry P. (2010). Adaptive phenotypic plasticity and resilience of vertebrates to increasing climatic unpredictability. Clim. Res.43, 135–147. doi: 10.3354/cr00897

14

Carroll D. J. Kempf S. C. (1990). Laboratory culture of the aeolid nudibranch Berghia verrucicornis (Mollusca, Opisthobranchia): Some aspects of its development and life history. Biol. Bull.179, 243–253. doi: 10.2307/1542315

15

Chevin L.-M. Hoffmann A. A. (2017). Evolution of phenotypic plasticity in extreme environments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc B372, 20160138. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0138

16

Collin R. Rebolledo A. P. Smith E. Chan K. Y. K. (2021). Thermal tolerance of early development predicts the realized thermal niche in marine ectotherms. Funct. Ecol.35, 1679–1692. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13850

17

Collins M. Clark M. S. Truebano M. (2023). The environmental cellular stress response: the intertidal as a multistressor model. Cell Stress Chaperones28, 467–475. doi: 10.1007/s12192-023-01348-7

18

Cooke S. J. Sack L. Franklin C. E. Farrell A. P. Beardall J. Wikelski M. et al . (2013). What is conservation physiology? Perspectives on an increasingly integrated and essential science. Conserv. Physiol.1, cot001–cot001. doi: 10.1093/conphys/cot001

19

Cowan Z.-L. Andreassen A. H. De Bonville J. Green L. Binning S. A. Silva-Garay L. et al . (2023). A novel method for measuring acute thermal tolerance in fish embryos. Conserv. Physiol.11, coad061. doi: 10.1093/conphys/coad061

20

Czaja R. Beal B. Pepperman K. Espinosa E. P. Munroe D. Cerrato R. et al . (2023). Interactive roles of temperature and food availability in predicting habitat suitability for marine invertebrates. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.293, 108515. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2023.108515

21

Dahlke F. T. Wohlrab S. Butzin M. Pörtner H.-O. (2020). Thermal bottlenecks in the life cycle define climate vulnerability of fish. Science369, 65–70. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz3658

22

Dani V. Priouzeau F. Pagnotta S. Carette D. Laugier J.-P. Sabourault C. (2016). Thermal and menthol stress induce different cellular events during sea anemone bleaching. Symbiosis69, 175–192. doi: 10.1007/s13199-016-0406-y

23

Deaker D. J. Byrne M. (2022). The relationship between size and metabolic rate of juvenile crown of thorns starfish. Invertebrate Biol.141, e12382. doi: 10.1111/ivb.12382

24

Delorme N. J. King N. Cervantes-Loreto A. South P. M. Baettig C. G. Zamora L. N. et al . (2024). Genetics and ontogeny are key factors influencing thermal resilience in a culturally and economically important bivalve. Sci. Rep.14, 19130. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-70034-0

25

Deschamps M. Giménez L. Astley C. Boersma M. Torres G. (2025). Heatwave duration, intensity and timing as drivers of performance in larvae of a marine invertebrate. Sci. Rep.15, 15949. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-98259-7

26

Diaz De Villegas S. C. Borbee E. M. Abdelbaki P. Y. Fuess L. E. (2024). Prior heat stress increases pathogen susceptibility in the model cnidarian Exaiptasia diaphana. Commun. Biol.7, 1328. doi: 10.1038/s42003-024-07005-8

27

Diederich C. Pechenik J. (2013). Thermal tolerance of Crepidula fornicata (Gastropoda) life history stages from intertidal and subtidal subpopulations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.486, 173–187. doi: 10.3354/meps10355

28

Divu D. N. Mojjada S. K. Pokkathappada A. A. Anil M. K. Gopidas A. P. Sundaram S. L. P. et al . (2024). Exploring the thermal adaptability of silver pompano Trachinotus blochii: An initiative to assist climate change adaptation and mitigation to augment aquaculture productivity. Ecol. Inf.82, 102761. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102761

29

Doney S. C. Ruckelshaus M. Emmett Duffy J. Barry J. P. Chan F. English C. A. et al . (2012). Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci.4, 11–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-041911-111611

30

Ern R. Andreassen A. H. Jutfelt F. (2023). Physiological mechanisms of acute upper thermal tolerance in fish. Physiology38, 141–158. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00027.2022

31

Fernandes J. F. Calado R. Jerónimo D. Madeira D. (2023). Thermal tolerance limits and physiological traits as indicators of Hediste diversicolor’s acclimation capacity to global and local change drivers. J. Thermal Biol.114, 103577. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2023.103577

32

Fischer B. Van Doorn G. S. Dieckmann U. Taborsky B. (2014). The evolution of age-dependent plasticity. Am. Nat.183, 108–125. doi: 10.1086/674008

33

Fitzgerald-Dehoog L. Browning J. Allen B. J. (2012). Food and heat stress in the California mussel: Evidence for an rnergetic trade-off between survival and growth. Biol. Bull.223, 205–216. doi: 10.1086/BBLv223n2p205

34

Fortuna C. M. Fortibuoni T. Bueno-Pardo J. Coll M. Franco A. Giménez J. et al . (2024). Top predator status and trends: Ecological implications, monitoring and mitigation strategies to promote ecosystem-based management. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1282091

35

Fournier R. J. Colombano D. D. Latour R. J. Carlson S. M. Ruhi A. (2024). Long-term data reveal widespread phenological change across major US estuarine food webs. Ecol. Lett.27, e14441. doi: 10.1111/ele.14441

36

Fox R. J. Donelson J. M. Schunter C. Ravasi T. Gaitán-Espitia J. D. (2019). Beyond buying time: the role of plasticity in phenotypic adaptation to rapid environmental change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc B374, 20180174. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2018.0174

37

Gibson R. N. (Ed.) (2011). Oceanography and marine biology: An annual review (Boca Raton London New York: CRC Press).

38

Gillooly J. F. Brown J. H. West G. B. Savage V. M. Charnov E. L. (2001). Effects of size and temperature on metabolic rate. Science293, 2248–2251. doi: 10.1126/science.1061967

39

Gosselin L. Qian P. (1997). Juvenile mortality in benthic marine invertebrates. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.146, 265–282. doi: 10.3354/meps146265

40

Gunderson A. R. Stillman J. H. (2015). Plasticity in thermal tolerance has limited potential to buffer ectotherms from global warming. Proc. R. Soc B.282, 20150401. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0401

41

Guscelli E. Chabot D. Vermandele F. Madeira D. Calosi P. (2023). All roads lead to Rome: inter-origin variation in metabolomics reprogramming of the northern shrimp exposed to global changes leads to a comparable physiological status. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1170451

42

Han L. Hao P. Wang W. Wu Y. Ruan S. Gao C. et al . (2023). Molecular mechanisms that regulate the heat stress response in sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus intermedius) by comparative heat tolerance performance and whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing. Sci. Total Environ.901, 165846. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165846

43

Hardison E. A. Eliason E. J. (2024). Diet effects on ectotherm thermal performance. Biol. Rev.99, 1537–1555. doi: 10.1111/brv.13081

44

Harkiolakis N. (2013). “ Global warming,” in Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. Eds. IdowuS. O.CapaldiN.ZuL.GuptaA. D. ( Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg), 1256–1261. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-28036-8_367

45

Hartig F. (2016). DHARMa: Residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-Level / mixed) regression models. 0.4.7. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.DHARMa

46

Hobday A. J. Alexander L. V. Perkins S. E. Smale D. A. Straub S. C. Oliver E. C. J. et al . (2016). A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanography141, 227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2015.12.014

47

Hui T. Y. Dong Y. Han G. Lau S. L. Y. Cheng M. C. F. Meepoka C. et al . (2020). Timing metabolic depression: predicting thermal stress in extreme intertidal environments. Am. Nat.196, 501–511. doi: 10.1086/710339

48

Iannone R. Cheng J. Schloerke B. Hughes E. Lauer A. Seo J. et al . (2025). gt: Easily create presentation-ready display tables. Available online at: https://gt.rstudio.com.

49

Iwasa Y. Yusa Y. Yamaguchi S. (2022). Evolutionary game of life-cycle types in marine benthic invertebrates: Feeding larvae versus nonfeeding larvae versus direct development. J. Theor. Biol.537, 111019. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2022.111019

50

Jørgensen L. B. Robertson R. M. Overgaard J. (2020). Neural dysfunction correlates with heat coma and CTmax in Drosophila but does not set the boundaries for heat stress survival. J. Exp. Biol. 223 (Pt 13), jeb218750. doi: 10.1242/jeb.218750

51

Joyce P. W. S. Tong C. B. Yip Y. L. Falkenberg L. J. (2024). Marine heatwaves as drivers of biological and ecological change: implications of current research patterns and future opportunities. Mar. Biol.171, 20. doi: 10.1007/s00227-023-04340-y

52

Klingenberg C. P. (2019). Phenotypic plasticity, developmental instability, and robustness: The concepts and how they are connected. Front. Ecol. Evol.7. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00056

53

Kültz D. (2005). Molecular and evolutionary basis of the cellular stress response. Annu. Rev. Physiol.67, 225–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.103635

54

Laetz E. M. J. Kahyaoglu C. Borgstein N. M. Merkx M. van der Meij S. E. T. Verberk W. C. E. P. (2024). Critical thermal maxima and oxygen uptake in Elysia viridis, a sea slug that steals chloroplasts to photosynthesize. J. Exp. Biol.227, jeb246331. doi: 10.1242/jeb.246331

55

Leal M. C. Nunes C. Alexandre D. Da Silva T. L. Reis A. Dinis M. T. et al . (2012). Parental diets determine the embryonic fatty acid profile of the tropical nudibranch Aeolidiella stephanieae: the effect of eating bleached anemones. Mar. Biol.159, 1745–1751. doi: 10.1007/s00227-012-1962-1

56

Leung J. Y. S. Russell B. D. Connell S. D. (2019). Adaptive responses of marine gastropods to heatwaves. One Earth1, 374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2019.10.025

57

Liu Y. Chen L. Meng F. Zhang T. Luo J. Chen S. et al . (2023). The effect of temperature on the embryo development of cephalopod Sepiella japonica suggests crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. IJMS24, 15365. doi: 10.3390/ijms242015365

58

Liu F. Li Y. Yu H. Zhang L. Hu J. Bao Z. et al . (2021). MolluscDB: an integrated functional and evolutionary genomics database for the hyper-diverse animal phylum Mollusca. Nucleic Acids Res.49, D988–D997. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa918

59

Long W. C. Daly B. (2017). Upper thermal tolerance in red and blue king crab: Sublethal and lethal effects. Mar. Biol.164, 162. doi: 10.1007/s00227-017-3190-1

60

Lowe W. H. Martin T. E. Skelly D. K. Woods H. A. (2021). Metamorphosis in an era of increasing climate variability. Trends Ecol. Evol.36, 360–375. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2020.11.012

61

Madeira D. Fernandes J. F. Jerónimo D. Ricardo F. Santos A. Domingues M. R. et al . (2021). Calcium homeostasis and stable fatty acid composition underpin heatwave tolerance of the keystone polychaete Hediste diversicolor. Environ. Res.195, 110885. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110885

62

Madeira D. Madeira C. Costa P. M. Vinagre C. Pörtner H.-O. Diniz M. S. (2020). Different sensitivity to heatwaves across the life cycle of fish reflects phenotypic adaptation to environmental niche. Mar. Environ. Res.162, 105192. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.105192

63

Madeira C. Mendonça V. Leal M. C. Flores A. A. V. Cabral H. N. Diniz M. S. et al . (2017). Thermal stress, thermal safety margins and acclimation capacity in tropical shallow waters — An experimental approach testing multiple end-points in two common fish. Ecol. Indic.81, 146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.05.050

64

Madeira D. Narciso L. Cabral H. N. Diniz M. S. Vinagre C. (2012a). Thermal tolerance of the crab Pachygrapsus marmoratus: intraspecific differences at a physiological (CTMax) and molecular level (Hsp70). Cell Stress Chaperones17, 707–716. doi: 10.1007/s12192-012-0345-3

65

Madeira D. Narciso L. Cabral H. N. Vinagre C. (2012b). Thermal tolerance and potential impacts of climate change on coastal and estuarine organisms. J. Sea Res.70, 32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2012.03.002

66

Marchel M. Zahida F. Yuda I. P. (2021). Spesies diversity and abudance of Nudibranchia in Tulamben waters, Bali. J. Molusk. Indones.5, 34–41. doi: 10.54115/jmi.v5i1.6

67

Marshall D. J. Dong Y. McQuaid C. D. Williams G. A. (2011). Thermal adaptation in the intertidal snail Echinolittorina malaccana contradicts current theory by revealing the crucial roles of resting metabolism. J. Exp. Biol.214, 3649–3657. doi: 10.1242/jeb.059899

68

Matthews J. L. Sproles A. E. Oakley C. A. Grossman A. R. Weis V. M. Davy S. K. (2015). Menthol-induced bleaching rapidly and effectively provides experimental aposymbiotic sea anemones ( Aiptasia sp.) for symbiosis investigations. J. Exp. Biol. 219 (Pt 3), 306–310. doi: 10.1242/jeb.128934

69

McGillycuddy M. Warton D. I. Popovic G. Bolker B. M. (2025). Parsimoniously fitting large multivariate random effects in glmmTMB. J. Stat. Soft.112 (1), 1–19. doi: 10.18637/jss.v112.i01

70

McLachlan R. H. Price J. T. Solomon S. L. Grottoli A. G. (2020). Thirty years of coral heat-stress experiments: a review of methods. Coral Reefs39, 885–902. doi: 10.1007/s00338-020-01931-9

71

Minuti J. J. Corra C. A. Helmuth B. S. Russell B. D. (2021). Increased thermal sensitivity of a tropical marine gastropod under combined CO2 and temperature stress. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.643377

72

Missionário M. Fernandes J. F. Travesso M. Freitas E. Calado R. Madeira D. (2022). Sex-specific thermal tolerance limits in the ditch shrimp Palaemon varians: Eco-evolutionary implications under a warming ocean. J. Thermal Biol.103, 103151. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.103151

73

Monteiro E. A. Güth A. Z. Banha T. N. S. Sumida P. Y. G. Mies M. (2019). Evidence against mutualism in an aeolid nudibranch associated with Symbiodiniaceae dinoflagellates. Symbiosis79, 183–189. doi: 10.1007/s13199-019-00632-4

74

Mora C. Ospína A. (2001). Tolerance to high temperatures and potential impact of sea warming on reef fishes of Gorgona Island (tropical eastern Pacific). Mar. Biol.139, 765–769. doi: 10.1007/s002270100626

75

Morgan R. Finnøen M. H. Jutfelt F. (2018). CTmax is repeatable and doesn’t reduce growth in zebrafish. Sci. Rep.8, 7099. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25593-4

76

Morley S. A. Peck L. S. Sunday J. M. Heiser S. Bates A. E. (2019). Physiological acclimation and persistence of ectothermic species under extreme heat events. Global Ecol. Biogeogr28, 1018–1037. doi: 10.1111/geb.12911

77

Muff S. Nilsen E. B. O’Hara R. B. Nater C. R. (2022). Rewriting results sections in the language of evidence. Trends Ecol. Evol.37, 203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2021.10.009

78

Oliveira I. B. Freitas D. B. Fonseca J. G. Laranjeiro F. Rocha R. J. M. Hinzmann M. et al . (2020). Vulnerability of Tritia reticulata (L.) early life stages to ocean acidification and warming. Sci. Rep.10, 5325. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62169-7

79

Padilla D. K. Savedo M. M. (2013). “ A systematic review of phenotypic plasticity in marine invertebrate and plant systems,” in Advances in Marine Biology. Ed. LesserM. (Academic Press, Cambridge, M.A., U.S.A.: Elsevier), 67–94. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-410498-3.00002-1

80

Pandori L. L. M. Sorte C. J. B. (2019). The weakest link: Sensitivity to climate extremes across life stages of marine invertebrates. Oikos128, 621–629. doi: 10.1111/oik.05886

81

Pearce A. Lenanton R. Jackson G. Moore J. Feng M. Gaughan D. (2011). The “marine heat wave” off Western Australia during the summer of 2010/11 (Western Australia: Department of Fisheries).

82

Peck L. S. Clark M. S. Morley S. A. Massey A. Rossetti H. (2009). Animal temperature limits and ecological relevance: effects of size, activity and rates of change. Funct. Ecol.23, 248–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01537.x

83