Abstract

Introduction:

Against the backdrop of intensifying climate change, new emission reduction regulations from the International Maritime Organization (IMO) are driving the shipping industry to accelerate decarbonization. Clean alternative fuels are critical for achieving net-zero emissions; however, the development of their technical standards and application specifications lags behind technological advancements. This study focuses on the standards and specifications for marine clean alternative fuels under IMO’s new regulatory framework, aiming to address global coordination challenges and support the green transition of the shipping industry.

Methods:

This research employs a multidimensional approach: systematically reviewing policies and regulations from the IMO and major shipping nations/regions; integrating authoritative data from sources such as DNV GL and Clarksons Research to conduct a life-cycle assessment of mainstream clean alternative fuels; and constructing three representative scenarios through scenario analysis to evaluate fuel competitiveness and the direction of standard development.

Results:

The analysis reveals significant disparities in regulatory frameworks: China’s "1+N" policy system emphasizes top-down coordination, the EU relies on carbon trading mechanisms and mandatory measures like FuelEU Maritime, Japan prioritizes safety standards (e.g., ClassNK guidelines), and Singapore adopts pragmatic policies to establish a green fuel hub. Three major challenges in global standard harmonization are identified: geopolitical competition leading to fragmentation of standards, technological innovation outpacing regulatory development, and uneven infrastructure deployment.

Discussion:

To address these challenges, this study proposes establishing a global multi-level governance system, accelerating the construction of port infrastructure, and promoting the integration of international policies and standards. These measures aim to facilitate the coordinated development of technical standards and application specifications for marine clean alternative fuels, providing a systematic foundation for the industry’s green transition.

1 Introduction

Conventional fossil fuels are non-renewable resources. The exhaust gases emitted from ships powered by fossil fuels contain atmospheric pollutants such as sulfur oxides (SOX) and nitrogen oxides (NOX), as well as greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4). They not only contribute to air pollution in port areas but also exacerbate global climate change. A report published by Simpson Spence Young (SSY), an independent shipbroker based in the UK, states that global shipping CO2 emissions increased by 4.9% year over year to 833 million tons in 2021 (Gas network). On 13 November 2024, the Global Carbon Budget 2024 Report, led by the University of Exeter and compiled by over 80 institutions, was released at COP29. The report indicates that global CO2 emissions are likely to hit an all-time high in 2024, pushing the world further off track from meeting critical climate targets, with total emissions expected to reach 41.6 billion tons, up from 40.6 billion tons in 2023. Most of these emissions originate from the combustion of coal, oil, and natural gas (Global Carbon Project). Given the depletion of conventional fossil fuels and the pressing need to mitigate climate change, the demand for an energy transition is becoming increasingly urgent, with alternative energy sources emerging as a key solution for shipping decarbonization. Unlike land-based energy transitions, maritime operations face greater challenges due to the involvement of port infrastructure development, international conventions, flag state regulations, port state controls, and fuel supply chains, making the adoption of marine clean alternative fuels more complex (Molland, 2008).

To achieve sustainable green development in shipping, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has been actively promoting maritime decarbonization and advocating for the goal of net-zero emissions in international shipping. At its 72nd Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) session, the IMO set an ambitious target to reduce the annual total greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping by at least 50% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels. The 83rd MEPC session, held in London on 7–11 April 2025, approved draft amendments to Annex VI of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), marking the world’s first regulatory framework combining mandatory emission limits with greenhouse gas pricing in the shipping industry. This milestone framework represents a crucial step toward achieving net-zero carbon emissions in international shipping around 2050 (IMO, a). To meet these emission reduction targets, the shipping market is accelerating research and the application of new energy sources. Energy efficiency and cleanliness are the two core principles guiding the development of future marine fuels. Decarbonization pathways for shipping involve two key approaches: in the short term, improving marine engine technology and combustion efficiency, and in the long term, developing and adopting marine clean alternative fuels (Li et al., 2025). In this global “race to net zero,” major maritime nations strive to lead in new energy, propulsion systems, and materials, seeking a voice in setting international standards and technical regulations to gain strategic advantages for their domestic industries.

Liquefied natural gas (LNG), liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), methanol, biofuels, ammonia, hydrogen, nuclear energy and other low- or zero-carbon alternatives are currently the primary types of marine clean alternative fuels. Newer low-carbon auxiliary propulsion technologies include fuel cell systems, energy storage battery systems, and wind-assisted propulsion. When selecting marine clean alternative fuels, shipping companies focus primarily on the integrity of the fuel supply chain, operating costs, and safety. Even though clean alternative fuel technology is still in its infancy, the study and use of marine clean alternative fuels is becoming an unstoppable trend due to stricter emission reduction goals. According to statistics from Clarksons Research (CR), as early as 2021, there were 449 newbuild orders for alternative-fuel vessels worldwide, a significant increase compared with 209 vessels in 2020. In the first quarter of 2022, alternative-fuel vessels accounted for 61% of total newbuild orders by gross tonnage. In terms of fuel types, LNG remains the mainstream alternative, representing 94% of orders by vessel count, followed by methanol dual-fuel vessels (4%) and ethane dual-fuel vessels (2%), with 10% of vessels designed to use both LNG and ammonia (Eworldship, a). In 2024, the green and low-carbon trend continued to dominate the shipping market, with the size of the alternative-fuel-powered fleet expanding further and the share of such vessels in newbuild orders rising. By 2024, vessels powered by marine clean alternative fuels accounted for 43.2% of the global fleet by deadweight tonnage, marking a two-percentage-point increase from 2023. From January to April 2025, the share of alternative-fuel newbuild orders rose further to 63%, with orders for conventionally fueled vessels nearly disappearing (Al-Asmakh et al., 2025). These data indicate that, beginning in 2025, the application of marine clean alternative fuels in shipping has entered a new stage of rapid development, accelerating the sector’s decarbonization process (China Ocean Shipping e-Journal). As such regulations become more stringent, the use of carbon-neutral fuels will progressively increase, with ammonia and bio methanol considered the most promising options.

The growing demand for the application of marine clean alternative fuels has also increased the need for a comprehensive regulatory framework for clean energy in shipping. The international regulatory framework continues to evolve. Several international standards have been successively developed, such as the Generic interim guidelines on Training for Seafarers on Ships Using Alternative Fuels and New Technologies, the Use of Hydrogen as Fuel, Interim Guidelines for the Use of Ammonia Cargo as Fuel, and Interim Recommendations for the Carriage of Liquefied Hydrogen in Bulk the Interim Guidelines for the Safety of Ships Using Methyl/Ethyl Alcohol as Fuel (MSC.1/Circ.1621), and the Interim Guidelines for the Safety of Ships Using Ammonia as Fuel (MSC.1/Circ.1687). Although international regulatory rules for marine clean alternative fuels are being introduced at an accelerated pace, the global adoption of a “dominant fuel” remains contested due to technological and geopolitical factors. These factors further complicate international regulation and the global coordination of standards for marine clean alternative fuels (Kołakowski et al., 2024). Technical standards and regulations for marine clean alternative fuels have not received much in-depth academic research up to this point. The majority of studies conducted in the last five years have concentrated on technological aspects, leaving policy frameworks and regulatory systems largely unexplored (Helgason et al., 2020). To successfully achieve the “30·60” dual carbon targets, China must enhance top-level policy design and formulate national standards for marine clean alternative fuels. This study aims to analyze the current status of marine clean alternative energy technologies and standards, drawing on the practical experiences of several countries. It aims to offer suggestions for the future development of an international regulatory framework by embracing both domestic and international viewpoints and concentrating on policy and standardization aspects.

2 Current status of marine clean alternative fuel technologies

In recent years, major global shipping companies have actively engaged in planning and implementing new energy strategies. Throughout the maritime industry supply chain, the fuel decisions made by these powerful shipping companies serve as a guide and an example. An increasing number of real-ship applications demonstrate that key technologies for marine clean alternative fuels are gradually overcoming technical limitations. These technological advancements in turn influence the development of pertinent standards and regulations. As the specific characteristics of various marine clean alternative fuels fall outside the scope of this study, this section focuses solely on analyzing the development status of marine clean alternative fuels based on current real-ship cases.

2.1 Types of marine clean alternative fuels

2.1.1 LNG fuel

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is the most widely used low-carbon fuel and has attracted significant attention in the shipping industry. LNG can reduce CO2 emissions by 15–20%, cut SOX emissions by more than 98%, and lower NOX emissions by approximately 85–90% (Jeong and Yun, 2023). However, LNG-fueled engines are associated with “methane slip” during combustion, whereby unburned methane, a short-lived greenhouse gas with a much stronger warming effect than CO2, escapes into the atmosphere. This phenomenon is the primary reason why environmental organizations continue to question LNG’s environmental performance (Lagouvardou et al., 2023). Moreover, the development of LNG-powered vessels is constrained by factors such as fuel supply chain integrity, port infrastructure availability, and operating costs. Nevertheless, these challenges have not dampened industry enthusiasm for LNG investments.

2.1.2 LPG fuel

Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) primarily consists of propane and butane, with trace amounts of olefins. LPG can reduce SOX emissions by 90–97% and NOX emissions by 15–20% (Yang, 2009). A key advantage of LPG-powered vessels is that liquefied LPG can be supplied directly as marine engine fuel without the need for additional vaporization equipment. Furthermore, LPG fuel can be relatively easily sourced from a wide network of global bunkering facilities, making the development of its supply chain more feasible. These attributes have led to LPG being considered a marine fuel with substantial growth potential.

2.1.3 Methanol fuel

Methanol is a water-soluble and biodegradable liquid with advantages that include relatively easy storage and transport, as well as minimal modifications required for existing dual-fuel engines. It also offers considerable long-term potential for emission reduction (Lim, 2025). Methanol is thus regarded as one of the most promising marine clean alternative fuels for large-scale future applications. At the end of March 2015, the world’s first methanol-powered ferry, Stena Germanica (classed by Lloyd’s Register), successfully completed its inaugural methanol-powered voyage between Gothenburg, Sweden, and Kiel, Germany, demonstrating the feasibility of methanol as a marine fuel (Eworldship, b).

2.1.4 Hydrogen fuel

Hydrogen, known for its cleanliness and high efficiency, is widely regarded as a highly promising clean fuel, with Japan and South Korea having both launched national plans for its development. In 2017, the Belgian company Cie. Maritime Belge SA (CMB) built the world’s first diesel-hydrogen dual-fuel internal combustion ferry (Zhong, 2022). In 2021, Kawasaki Heavy Industries of Japan successfully launched and commissioned the SUISO FRONTIER, the world’s first liquefied hydrogen carrier (Eworldship, c). Liquefied hydrogen offers economic advantages in storage and is cost-effective for fixed port-to-port routes, making it well-suited for pilot projects under the “green shipping corridor” concept. Hydrogen-powered vessels are thus expected to achieve significant growth in the foreseeable future (Bullermann et al., 2024).

2.1.5 Ammonia fuel

Ammonia is another low-carbon fuel that has attracted widespread attention. The European Union, Japan, and South Korea are actively developing ammonia-fueled vessels, aiming to gain a first-mover advantage before the release of international standards for ammonia as a marine fuel. Ammonia, primarily produced from hydrogen, also serves as a hydrogen carrier: through separation processes, hydrogen can be extracted for use. Ammonia combustion generates no carbon emissions, and its supply, transportation, and storage are relatively stable and straightforward (Bilgili, 2023a). However, some argue that the cost of ammonia largely depends on that of its primary feedstock, and certain production methods may lead to additional greenhouse gas emissions, raising concerns about its sustainability as a marine fuel (Zhang et al., 2025). Nevertheless, in March 2025, NYK Line announced the completion of a three-month demonstration voyage of the Sakigake, the world’s first commercial vessel retrofitted from an LNG-powered ship to run on ammonia fuel. The trial achieved approximately a 95% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, demonstrating both the decarbonization potential and operational safety of ammonia (Zhaobo). This real-world operation not only verified the feasibility of ammonia as a next-generation marine fuel but also provided a model for the retrofitting of existing vessels.

2.1.6 Biofuels

Biofuels are renewable fuels produced from biological organisms (biomass), with plant oils serving as the primary feedstock (Fink et al., 2025). They are considered carbon-neutral, as the amount of CO2 emitted during combustion is largely offset by the CO2 absorbed by source plants during their growth. Biofuels also emit no sulfur oxides during combustion (IMO, b). The majority of biofuels are still being researched and verified. The Global Maritime Forum is making significant investments in the development of biofuels, aiming to achieve breakthroughs in fuel supply chains and technological applications.

2.1.7 Battery/hybrid power

The use of battery-powered technology enables vessels to significantly reduce pollutant emissions, offering a promising emission reduction technology with considerable market potential. Presently, electric-powered vessels are primarily passenger ferries and cruise ships, mainly concentrated in Northern Europe (Poseidon Principles). With continuous improvements in marine battery and hybrid propulsion technologies, as well as declining operational and maintenance costs, the scope of practical applications is expected to expand. In addition, wind energy is a clean and renewable resource, and wind-assisted propulsion has been recommended by Det Norske Veritas (DNV-GL) as one of the three major auxiliary technologies for alternative marine energy. Norsepower, a Finnish company, has developed rotor sail systems that received the first type approval from DNV-GL and have been installed on vessels for pilot operations (Eworldship, d). Japan has also expressed high expectations for wind-assisted propulsion, with multiple shipping companies investing in the development of next-generation sail-powered vessels. However, the application of wind propulsion faces notable challenges, such as the high degree of unpredictability in maritime navigation, especially under adverse weather conditions, as well as stringent requirements for vessel stability and operational performance. Its adoption is further limited by high maintenance costs and low seafarer acceptance.

2.1.8 Summary

It is crucial to acknowledge the long-term necessity of developing such zero-carbon fuels, while maintaining a clear awareness of the significant challenges currently faced. Taking LNG as an example, it possesses certain advantages as an alternative fuel, including mature technology, partially reusable infrastructure, and the ability to rapidly reduce reliance on coal. However, it also carries risks, such as prolonged dependence on fossil-based infrastructure, the adverse impact of methane slip on short-term climate goals, and the potential diversion of investment away from truly zero-carbon energy sources.

Future research should develop more spatiotemporally refined models to determine the optimal duration and geographical scope for marine clean alternative fuels and to avoid lock-in effects. A comprehensive full life-cycle cost-benefit and environmental impact assessment is needed for different production pathways of clean fuels. It is imperative to study the development pathways and investment requirements for establishing a global zero-carbon fuel supply chain, including its transportation, storage, and safety management.

2.2 Global newbuilding market fuel transition landscape

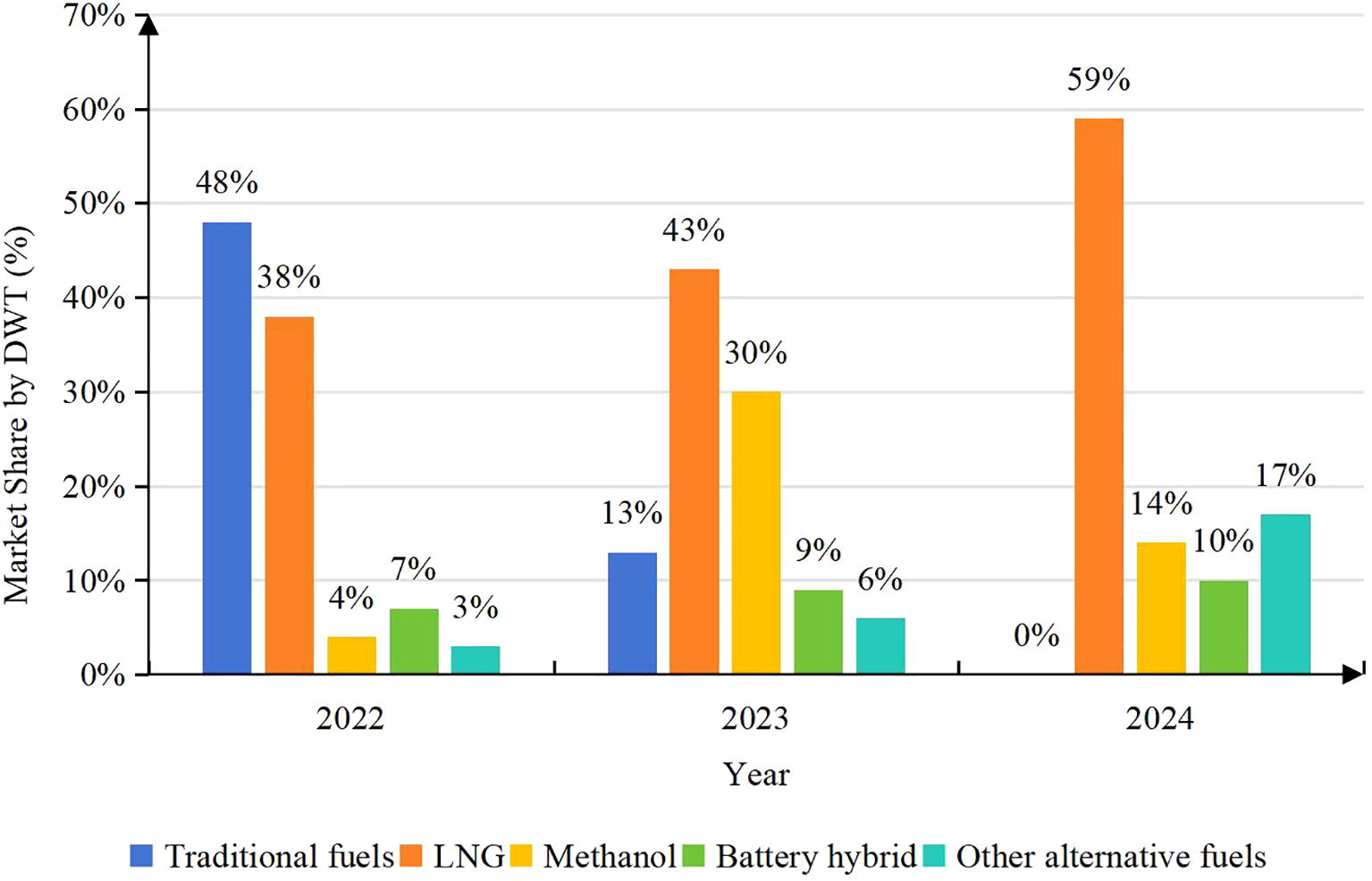

The year 2024 marks a pivotal milestone in the maritime industry’s fuel transition. According to CR data, alternative-fuel vessels accounted for over 50% of the global newbuilding orders by deadweight tonnage(DWT) for the first time, while orders for conventionally fueled vessels have shrunk to nearly zero. Figure 1 illustrates the newbuilding order trends from 2022 to 2024 across different fuel types, measured by deadweight tonnage and including both confirmed orders and “fuel-ready” design orders.

Figure 1

Composition of newbuilding orders by fuel types from 2022 to 2024 (measured in DWT, including confirmed and fuel-ready design orders). Other marine clean alternative fuels include LPG, ammonia, hydrogen, biofuels, etc.; Traditional fuels accounted for nearly 0% of total tonnage in 2024.Data source: Clarksons Research(CR), 2025.

The structural shift in shipowners’ newbuilding orders reflects three distinct industry trends. Container ships and car carriers have emerged as the primary adopters of marine clean alternative fuels. In 2024, LNG-powered vessels maintained a leading share of 58% among new orders in this segment, followed by methanol-powered vessels at 30%, with conventionally fueled ships nearly phased out. Leading shipping companies such as Maersk and CMA CGM have cumulatively ordered over 100 methanol-fueled vessels. This trend, combined with an 18% reduction in LNG technology costs at Chinese shipyards, is driving the establishment of mature fuel transition pathways for vessels operating on fixed routes (Edaily).

In short-sea shipping, 45% of newbuilding orders for roll-on/roll-off vessels and ferries utilize battery/hybrid propulsion systems, supported significantly by a 60% shore power coverage rate at Nordic ports. Meanwhile, the growing demand for long-term decarbonization is fostering strategic deployment of ammonia fuel: 6% of new ship orders now include ammonia-ready designs (comprising 45 confirmed orders and 303 options). Related technology patents have increased annually by 37%, according to World Intellectual Property Organization data, laying the foundation for zero-emission shipping post-2030 (Class NK).

However, bulk carriers and tankers exhibit slower transition rates, with conventional fuels still accounting for 83% of new orders in these segments. The main bottleneck lies in infrastructure gaps: only 18% of global ports are equipped with green fuel bunkering capabilities, methanol bunkering is available at just 35 ports worldwide, and ammonia/hydrogen fueling infrastructure has yet to reach significant scale. While container ships are charting courses toward zero-carbon shipping corridors, bulk carriers continue to seek a balance between technological feasibility, economic viability, and operational flexibility, indicating that comprehensive decarbonization of small and medium-sized vessels will require a transitional phase.

2.3 Comprehensive evaluation of marine clean alternative fuels

One of the most critical ways to meet the “carbon peak and carbon neutrality” targets is to encourage the use of clean alternative fuel technologies. Although new clean alternative fuel technologies are now being used on actual ships, many practical obstacles still stand in the way of their widespread adoption. To systematically evaluate the comprehensive performance of alternative marine fuels, this section draws upon data from authoritative institutions such as DNV-GL and CR. Based on the well-to-wake life cycle assessment methodology (Yuksel, 2023), this study analyzes mainstream alternative clean fuels across five dimensions: technological maturity, emission reduction potential, economic viability, infrastructure coverage, and safety risks and regulatory levels. Combined with scenario analysis, this approach provides scientific basis for industry technology selection and policy formulation. Notably, battery/hybrid propulsion, despite its advantages in specific vessel segments, was excluded from this comprehensive fuel evaluation due to its relatively small overall market share.

2.3.1 Evaluation framework

2.3.1.1 Technology maturity

Assessed using the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) scale, which ranges from 1 to 9, with higher values indicating greater maturity. Levels are assigned based on the scale of real-ship applications and operational duration. Data are sourced from the DNV Global Alternative Fuels Vessel Statistics Report.

2.3.1.2 Emission reduction potential

Calculated as the carbon reduction rate of the fuel’s full lifecycle relative to the IMO-defined baseline for heavy fuel oil (HFO) carbon intensity, encompassing production, transportation, and combustion stages.

2.3.1.3 Economic feasibility

Integrates fuel market prices and vessel retrofit costs through a full lifecycle cost analysis over a 10-year asset depreciation period.

2.3.1.4 Infrastructure coverage

Quantified by the penetration rate of fuel supply networks based on Clarksons’ global top 100 ports bunkering service database.

2.3.1.5 Safety risk level and regulatory compliance

Comprehensive assessment of fuel toxicity, flammability and explosive limits, and other characteristic parameters, along with compliance with international standards and national regulations. Safety Risks and Regulatory Compliance: Comprehensive assessment of fuel toxicity, flammability and explosion limits, and other characteristic parameters, along with compliance with international standards and national regulations.

2.3.2 Data description for each dimension

2.3.2.1 Technology maturity

LNG has reached full commercialization (TRL 9). According to a DNV survey, technologies related to LNG, such as cryogenic storage and fuel supply systems, are widely applied and have become stable. Methanol is in the quasi-commercialization stage (TRL 8), with dual-fuel engines having accumulated over 1.5 million operating hours. Some vessels have successfully adopted methanol fuel, and the related technology is continually improving, though its application scale is still smaller than that of LNG. Ammonia fuel storage and leakage monitoring technologies are still under development (TRL 5). Hydrogen is currently in the engineering verification stage (TRL 5), with orders concentrated in the cruise/ferry segment (less than 1%). Both ammonia and hydrogen face numerous technical challenges in storage, transportation, and engine compatibility, and are still far from large-scale commercial application.

2.3.2.2 Emission reduction potential

In terms of emission reduction potential, a comparative summary of various fuels is provided in Table 1. Among them, LNG, while able to reduce some carbon emissions, is significantly impacted by methane slip, which severely affects its actual emission reduction performance. Methanol, ammonia, and liquefied hydrogen (LH2) demonstrate higher emission reduction potential; however, methanol is limited by the availability of biomass carbon sources, ammonia faces challenges related to high electrolytic energy consumption, and liquefied hydrogen suffers from liquefaction efficiency losses.

Table 1

| Fuel | Emission reduction range | Key factors |

|---|---|---|

| LNG | 10% - 25% | Methane slip |

| Methanol | 85% - 95% | Sustainability of biomass carbon sources |

| Ammonia | 92% - 98% | Electrolytic energy consumption |

| Hydrogen | 96% - 99% | Liquefaction efficiency loss |

Emission reduction potential comparison.

The emission reduction rate is calculated based on the IMO (2023) HFO carbon emission intensity of 94 gCO2eq/MJ.

2.3.2.3 Economic comparison: cost multiples

LNG costs approximately 1.8 to 2.2 times that of conventional fuels (HFO), including both fuel procurement costs and vessel modifications to accommodate LNG. Methanol costs 2.3 to 2.8 times more than HFO, with relatively higher fuel prices and the need for significant investment in vessel engine and other modifications. Ammonia costs 3.5 to 4.5 times that of HFO, with storage tank costs accounting for 60% of modification expenses. Ammonia fuel requires specialized storage tanks, which contribute significantly to the modification costs, resulting in poorer overall economic feasibility.

2.3.2.4 Infrastructure coverage

The data on the global top 100 ports coverage is as follows. Currently, LNG has relatively well-developed bunkering facilities in lots of ports worldwide, offering a significant infrastructure advantage (Rao et al., 2025). The infrastructure for methanol fueling is lagging, with limited coverage in major global ports, restricting its widespread application. Ammonia fuel infrastructure is still in its infancy, with only a handful of ports offering related bunkering services. Hydrogen fuel infrastructure is also limited, primarily concentrated in hub ports within specific regions.

2.3.2.5 Safety risk level and regulatory compliance

Ammonia presents a toxic risk, with no comprehensive international safety standards in place. In the event of a leak or other incidents, ammonia can pose severe risks to both personnel and the environment. Hydrogen has a wide flammability and explosive range, with a lack of certification standards for storage tanks. Its flammability and explosive characteristics increase safety risks during use, and the lack of proper safety regulations further complicates safety management. Methanol, on the other hand, has low toxicity and is the most mature in terms of safety management, having established a relatively comprehensive safety management system through years of practical application.

2.3.3 Conclusions of the comprehensive evaluation of marine fuels based on scenario analysis

Given the long-term and uncertain nature of the shipping industry’s energy transition, relying solely on static assessment methods proves insufficient to fully support the scientific rigor and foresight of strategic decision-making. Against this backdrop, this study introduces scenario analysis to conduct dynamic research, establishing a critical pathway for accurately evaluating the competitiveness of marine fuels. Based on core variables influencing shipping industry development, this study constructs three representative scenarios to systematically analyze the market competitiveness of various fuels under different conditions:

-

Baseline Scenario. This scenario assumes the continuation of current policy trends and technological development pace, with moderate increases in carbon market prices and ongoing iteration of marine propulsion technologies at current rates. In terms of fuel competition, LNG and methanol will maintain market dominance in the medium to short term due to their mature technological systems and significant economic advantages. Notably, under current regulatory frameworks, LNG-powered vessels burning fossil-derived LNG are exempt from related carbon penalties. This competitive edge is projected to persist beyond 2031, serving as a crucial support for both fuels to sustain their market share.

-

Policy Intensification Scenario. This scenario focuses on a development path featuring significantly tightened global decarbonization policies. It assumes countries will accelerate shipping decarbonization through a combination of policies: setting aggressive carbon reduction targets, establishing high carbon pricing levels, implementing mandatory zero-carbon fuel quotas, and providing dedicated subsidies for green fuels. Under this framework, the market competitiveness of green methanol and green ammonia will significantly improve. The former benefits from its environmentally friendly attributes derived from renewable feedstocks, while the latter gains clear advantages through its tradable “surplus unit” mechanism under policy incentives. Conversely, traditional fossil fuels and “gray” fuels will face severely weakened economics due to rising carbon costs, leading to a substantial contraction in their market space.

-

Technology Breakthrough Scenario. This scenario centers on breakthroughs in key technologies, assuming unexpectedly steep cost reductions for electrolyzers (core equipment for green hydrogen production), ammonia fuel cells, and carbon capture and storage (CCS). These advancements would significantly optimize the cost structure of the green energy supply chain. In terms of fuel competition, the economic viability of green ammonia and green hydrogen will substantially improve, enabling rapid market share expansion. Long-term projections indicate that by 2040 and beyond, e-fuels—leveraging their dual advantages of large-scale production capability and full compliance with global fuel standards—are expected to emerge as the most cost-effective fuel option, propelling the shipping industry into a phase of deep decarbonization.

-

To enhance the dynamic adaptability of the five-dimensional assessment framework across different future scenarios and improve the transparency of evaluation outcomes, this study assigns differentiated weightings to each assessment dimension for every scenario. These weightings are not arbitrarily determined but result from a comprehensive analysis synthesizing perspectives from the literature and expert judgments applied during the research team’s deliberations. The core rationale lies in reflecting how decision-makers—such as shipowners and policymakers—shift their priorities when selecting fuels under varying external driving conditions, and the weight distributions under different scenarios are detailed in Table 2. Under the baseline scenario, weight allocations remain relatively balanced, reflecting that technological maturity and economic viability continue to be the primary constraints on market adoption under the assumption of current trend continuation. The policy-enhanced scenario significantly increases the weight assigned to “emission reduction potential,” directly aligning with the core regulatory focus on lifecycle carbon emissions as outlined in policy frameworks such as the IMO (2023) Greenhouse Gas Reduction Strategy and the EU’s “Fit for 55” package (IMO, a; Christodoulou and Cullinane, 2022; Kouzelis et al., 2022). In the technological breakthrough scenario, “economic viability” receives the highest weighting. This is based on cost reduction projections for key technologies like electrolyzers from organizations such as the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), indicating that under these conditions, cost competitiveness would replace policy pressure as the primary driver of market penetration. This weighting design aims to transform the qualitative framework into a more comparable dynamic assessment tool. Subsequent analysis will proceed based on this weighting logic.

Table 2

| Evaluation dimension | Baseline scenario | Policy intensification scenario | Technology breakthrough scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technological Maturity | 25% | 20% | 15% |

| Emission Reduction Potential | 20% | 35% | 25% |

| Economic Feasibility | 25% | 20% | 35% |

| Infrastructure Coverage | 15% | 15% | 15% |

| Safety Risk & Regulatory Compliance | 15% | 10% | 10% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Weight distribution and basis for evaluation dimensions across different scenarios.

Weight allocation was determined through the integration of two analyses: (1) priorities reflected in reference policy guidance documents and literature (IMO, a; Christodoulou and Cullinane, 2022; Kouzelis et al., 2022; Christodoulou et al., 2025); (2) expert judgment formed by the research team following thematic discussions based on prior work in the field (1). The bold value in each row indicates the evaluation dimension assigned the highest weight under that specific scenario.

It is particularly important to note that to ensure the dynamic adaptability of assessment outcomes, this study has implemented scenario-based adjustments to the weightings and scoring criteria for each evaluation dimension—including environmental performance, economic viability, and technological maturity. For instance, under the policy-strengthened scenario, the weighting for “environmental performance” is significantly increased to reflect policy prioritization of environmental attributes. while in the technological breakthrough scenario, the scoring logic for “economic viability” was adjusted to incorporate cost reductions driven by technological advancements as a core evaluation metric, thereby more accurately reflecting the key drivers of fuel competitiveness under different scenarios.

3 Standards and regulatory framework for marine clean alternative fuels

As mentioned in the previous analysis of marine clean alternative fuels, the maturity of different technologies varies significantly. In general, standards and regulations often lag behind technological advancements and are less advanced than the technologies themselves. Several clean alternative fuel technologies remain immature, and the development of related standards is still in progress, with application regulations often remaining at the strategic planning level. Regarding technological development, the policies and standards for shipping decarbonization, as well as industry policies related to clean fuels, play a guiding and facilitating role in the advancement of new energy sources and alternative fuels. Alternative fuels, as a path for the maritime industry to address climate change, fall under the same international framework for greenhouse gas emissions reductions as fossil fuels, focusing on energy savings and emission reductions. The examination of standards and application regulations for marine clean alternative fuels must be conducted within the broader context of achieving net-zero emissions in shipping. The existing regulatory framework for traditional fossil fuels provides guidance for the development of new energy sources. The question of whether to maintain the current framework or establish new regulatory standards will unavoidably come up once marine clean alternative fuels reach a certain point. This section will examine and evaluate the IMO’s goal-setting for the development of marine clean alternative fuels, industry policies from various countries and national standards and classification society standards, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

| Country/Region | Policy focus | Key mechanisms | Strengths | Challenges | Relevant standards/Initiatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | Systematic, top-down, integrated with national energy strategy | “1+N” policy system, green shipping funds, port infrastructure incentives | Rapid large-scale implementation, strong government support | Limited market-driven flexibility, reliance on state-led investment | CCS guidelines for LNG, methanol, biofuels; Shanghai Green Fuel Plan (CCS; Trivyza et al., 2022) |

| EU | Regulatory coercion, market-based carbon pricing | EU ETS, FuelEU Maritime, AFIR | Leverages single market to force global compliance, high environmental integrity | Complex compliance, high costs for non-EU operators, trade tensions risk | Renewable Energy Directive, AFIR bunkering requirements (Onishchenko et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023) |

| Japan | Technology-led, safety-focused | ClassNK guidelines, R&D subsidies, hydrogen/ammonia roadmap | High safety credibility, trusted technical standards globally | Slower commercial deployment, limited scale of domestic market | ClassNK Guidelines for Alternative Fuels v3.0 (Bilgili, 2023b; Melnyk et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2025) |

| Singapore | Hub-based, pragmatic and open | Green Port Program, LNG bunkering pilots, GCMD, green corridors | Flexibility, strong international cooperation, focus on future business models | Limited domestic manufacturing, reliance on imports for fuels | Maritime SG Green Initiative, GCMD partnerships (Benet et al., 2022; Mallouppas et al., 2022; Savas et al., 2023) |

| South Korea | Industry-competitive, export-oriented | Green Ship Fuel Supply Chain Plan, R&D funding for ammonia/hydrogen | Strong industrial alignment, global shipbuilding market leverage | High dependency on export markets, geopolitical pressures | MOF Green Fuel Targets (2027/2030) (Rehbein et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2025) |

| UK | Innovation-focused, strategic incubation | Clean Maritime Demo Competition, UK ETS, ammonia fuel guidelines | Strong R&D ecosystem, early policy experimentation | Post-Brexit regulatory influence reduced, scaling challenges | MCA Ammonia Fuel Guidelines (2025) (Maritime decarbonisation strategy and calls for evidence) |

Comparative overview of regulatory frameworks for marine clean alternative fuels in major shipping nations/regions.

This table provides a qualitative summary based on the preliminary analysis in Sections 3.2 and 3.3. The basis for comparison stems from the core characteristics of each regulatory approach identified in the literature and referenced official documents.

3.1 International regulations and standards

To advance the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in international shipping, the IMO and national governments have set specific emission reduction targets and zero-carbon milestones. The mandatory provisions in Annex VI of the MARPOL regarding the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) and Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) came into effect on January 1, 2013. The regulations concerning the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) for existing ships came into effect in 2023. The EEXI energy efficiency standard and the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII), effective from 2025, require that from 2026 onwards, all new ships must meet the annual carbon intensity criteria. The development of marine alternative fuel technologies and regulations will accelerate in response to urgent decarbonization targets.

As a long-term strategic choice, clean alternative energy is highly anticipated. Regarding the safe use of LNG vessels, the IMO issued the International Code of Safety for Ships Using Gases or Other Low-Flashpoint Fuels (IGF Code). In 2018, the IMO completed the Interim Guidelines for the Safety of Ships Using Methyl/Ethyl Alcohol as Fuel, providing a global unified technical standard and regulatory reference for the use of alcohol-based fuels (Christodoulou et al., 2025). Additionally, the IMO’s focus on alternative energy is reflected in two meetings concerning marine clean alternative fuels. The first was the 6th Working Group Meeting on Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Ships in November 2019, and the second was the Alternative Fuels Workshop in 2021. Both meetings outlined target plans and implementation visions for the development of marine clean alternative fuels.

In addition to these standards, the IMO is also promoting shipping decarbonization through various means, including green finance and green shipping corridors. The Poseidon Principles for Marine Insurance, established in June 2019, is a framework that incorporates climate factors into loan decisions to promote decarbonization in international shipping. Each signatory must quantitatively assess the climate alignment of their shipping portfolios in accordance with global climate targets and disclose results based on the technical guidelines of the Poseidon Principles (Yuksel, 2023). The Green Shipping Corridor refers to specific shipping routes between major port hubs, which support and showcase carbon-free solutions within an ecosystem that includes regulatory and safety measures. These non-technical operational measures guide and stimulate the shipping industry to accelerate the adoption of marine clean alternative fuels.

On March 9, 2023, under the IMO’s GreenVoyage2050 project, the Low Carbon Global Industry Alliance (Low Carbon GIA) released a report titled Regulatory Mapping of Marine Alternative Fuels, which detailed the current regulatory documents for various types of marine fuels. This includes ISO standards, EU EN standards, IGF Code, IGC Code, IBC Code, the SOLAS Convention, and MARPOL (Zou and Yang, 2023). Currently, although safety guidelines for the use of methanol and ethanol as fuels are being developed, there remain gaps in the IMO’s safety requirements for low-flashpoint and toxic fuels. Additionally, the IMO is working to address the issues related to ammonia, hydrogen, and low-flashpoint diesel. For marine clean alternative fuels that are not covered by Annexes I or II of MARPOL, considerations regarding fuel spill risks need to be taken into account (Zincir and Arslanoglu, 2024). Future regulations may require certification for engine methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, but current MARPOL Annex VI and NOX regulations do not encompass these certification requirements. Regarding marine fuel quality, only a few alternative fuels have established quality standards for marine fuels. However, if existing land-based fuel standards are applicable, specialized standards for marine applications may not be necessary (Maritime Safety Administration pf the People’s Republic of China, 2025).

From March 18 to 22, 2024, the IMO convened the 81st Session of the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC 81) to discuss and approve several measures for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in shipping, providing a policy framework for the maritime industry’s transition to net-zero emissions. In support of global greenhouse gas reductions from ships, the MEPC 81 meeting introduced a draft outline for the IMO Net-Zero Emissions Framework, which aims to guide international shipping towards the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 (Kouzelis et al., 2022). This framework will be implemented through amendments to the existing MARPOL. The MEPC 81 has adopted, by Resolution MEPC.385(81), amendments to the Annex of the 1997 Protocol to the 1973 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 (hereinafter referred to as the MARPOL Convention), which will officially enter into force on 1 August 2025 (Huang et al., 2022). The 2024 amendments to Annex VI of the MARPOL Convention mainly addresses regulations related to low-flashpoint and gas fuels, clarifying inspection requirements for non-identical alternative diesel engines, and updating data collection requirements for ship fuel consumption, among other changes.

From November 11 to November 24, 2024, the 29th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP29) was held in Baku, Azerbaijan. During this conference, global carbon market standards were adopted, providing a unified framework for global carbon trading and officially launching the “Water for Climate Action” initiative. Several countries announced more ambitious NDC and national adaptation plans during the event (IMO, c). However, significant disagreements between developed and developing nations regarding climate finance, emission targets, adaptation funds, and the distribution of responsibility led to the lack of substantial breakthroughs on key issues.

From April 7 to 11, 2025, the IMO convened the 83rd meeting of the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC 83) in London, where it approved the draft amendments to MARPOL Annex VI. This is the world’s first framework that combines mandatory emission limits with greenhouse gas pricing for the maritime industry. This emission reduction framework is a crucial step towards achieving net-zero emissions in international shipping by 2050. The framework includes two core measures: new fuel standards for ships and a global emissions pricing mechanism. It establishes a regulatory system based on the greenhouse gas fuel intensity (GFI), with two compliance targets: direct compliance and base target (National Development and Reform Commission, 2022). Ships that fail to meet emission reduction targets will incur carbon emission costs.

On April 11, 2025, IMO member states reached a global agreement at the global maritime decarbonization negotiations held at IMO’s headquarters in London. The agreement approves the global net-zero emissions regulation for shipping, which also includes the first global carbon tax for international shipping. This is the first carbon revenue system of any kind managed by the United Nations. According to the IMO’s 2023 strategy, the agreement includes a new measure setting global standards for progressively reducing the greenhouse gas intensity of ship fuels. This measure will regulate the “cleanliness” of ship fuels based on their climate impact, covering the entire lifecycle of shipping fuels. It uses standardized standards and universal certification schemes to ensure that the global shipping market, regardless of where the fuel is produced, transported, or used, can maintain a level playing field (Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China, 2022). This approach effectively prevents emissions from being shifted to other sectors and encourages sustainable investments globally, accelerating emission reductions. Additionally, the agreement introduces the world’s first emissions pricing mechanism, which, through financial incentives, encourages shipping companies to use the cleanest fuels and technologies as early as possible. For instance, companies will receive incentives for investing in zero-emission and near-zero-emission marine clean fuels such as renewable methanol and ammonia.

3.2 National industry policies and technical standards

3.2.1 China

China has established a “1+N” policy system for achieving carbon peak and carbon neutrality (where “1” refers to two key documents: the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council’s Opinions on Fully and Accurately Implementing the New Development Concept and Achieving Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality, and the Action Plan for Achieving Carbon Peak Before 2030; “N” refers to specific implementation plans and related supporting schemes in key areas and industries). This system systematically deploys green and low-carbon actions in the transportation sector, with clear goals, clear paths, and strong measures. The policy framework includes documents such as the Outline for Building a Strong Transportation Nation and the 14th Five-Year Plan for Green Transportation Development, and extends to the construction of a technical standards system and the innovation of financial support mechanisms, providing solid support for the green transformation of transportation.

In 2020, at the 75th United Nations General Assembly, the Chinese government proposed the “3060” carbon peak and carbon neutrality goals. Subsequently, China issued the Opinions on Fully and Accurately Implementing the New Development Concept and Achieving Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality and the Action Plan for Achieving Carbon Peak Before 2030. In the field of energy conservation and emission reduction in transportation, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the National Energy Administration (NEA) released the Opinions on the Green and Low-Carbon Transition Mechanisms, Systems, and Policy Measures in 2021, being implemented in coordination with energy-sector carbon peak policies to guide the establishment of a low-carbon transportation system (The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, a). On March 25, 2022, the Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Science and Technology jointly issued the Medium- and Long-term Development Plan for Technological Innovation in the Transportation Sector (2021-2035), which mentioned accelerating the application of technologies related to intelligent green manufacturing, safe and efficient clean energy, resource efficiency, and ecological environmental protection (The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, b).

On January 19, 2023, the State Council Information Office released a white paper titled China’s Green Development in the New Era, which emphasized the need to “raise vehicle emission standards, promote the use of LNG for ships, and retrofit shore power reception facilities, while accelerating the transformation and elimination of old ships.” (The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, c) On December 29, 2023, five departments, including the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and the NDRC, jointly issued the Green Development Action Plan for the Shipbuilding Industry (2024-2030), which proposes that by 2025, China will have established an initial green development system for shipbuilding, with an increased supply capacity for green ship products. It aims for international market shares of green-powered ships, such as LNG and methanol vessels, to exceed 50% (The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, d).

On December 27, 2023, the NDRC revised and issued the Industrial Structure Adjustment Guidance Catalogue (2024 Edition) (Shanghai Municipal People's Government), including the addition of “Water Electrolysis Hydrogen Production and Carbon Dioxide Catalytic Synthesis of Green Methanol” to the list of encouraged industries in the renewable energy sector. This new policy opens up new opportunities for the hydrogen industry’s application and market expansion in China. Green methanol synthesis technology addresses key challenges in the hydrogen energy production, storage, and transportation processes, providing a practical path for the safe and efficient use of hydrogen energy and becoming a crucial step toward achieving China’s “3060” carbon peak and carbon neutrality goals and building a modern energy system.

In March 2024, the State Council issued the Action Plan for Promoting Large-Scale Equipment Renewal and Consumer Goods Trade-In (Eworldship, e). The plan emphasizes the need for equipment updates, accelerating the scrapping and replacement of high-energy consumption and high-emission old vessels, and strongly supports the development of ships powered by new energy sources. The plan also highlights the improvement of infrastructure and standards for new energy vessels, and the gradual expansion of applications for electric, LNG-powered, biodiesel-powered, and green methanol-powered ships. Green methanol is expected to be first widely adopted in the large shipping sector, potentially driving the global transition from low-carbon to zero-carbon and negative-carbon practices.

In October 30, 2024, the Shanghai Development and Reform Commission, Shanghai Municipal Transportation Commission, and Shanghai Municipal Economic and Information Technology Commission jointly issued the Shanghai’s Work Plan for Promoting the Green Transition of International Shipping Fuels (CCS). The plan outlines the following objectives. By 2030, Shanghai aims to form a collaborative green fuel supply system for international shipping. The plan specifies that Shanghai’s bonded LNG fueling capacity will reach one million cubic meters (liquid), while green methanol and green ammonia fueling capabilities will reach one million tons. At the same time, technological innovation and demonstration applications will reach internationally leading levels, forming a group of technology-leading enterprises with strong international competitiveness. The core competitiveness of the entire industry chain will steadily improve, and a green fuel refueling service center will be established, laying the foundation for the development of an international green fuel trading center and international green fuel certification service center.

In terms of technical standards, since the China Classification Society (CCS) issued the Guidelines for the Inspection of Gas-Fueled Powered Ships in 2008, a series of related guidelines and standards have been developed and released, including the Natural Gas Fuel Powered Ship Specification, Ship Alternative Fuel Application Guidelines, Liquefied Natural Gas Fuel Refueling Ship Specification, and Pure Battery-Powered Ship Inspection Guidelines (MSA). On July 1, 2024, the new version of the Ship Application of Natural Gas Fuel Specification (2024) will come into effect, replacing its 2021 version and subsequent amendments. The new version of the Ship Application of Biofuels Guidelines has taken effect on April 1, 2025, replacing the section on “Biodiesel” in the Alternative Fuel Guidelines for Ships (2017) (Zincir, 2022).

In addition, China has led the completion of the International Guidelines for Shore Power Safety Operation for International Voyaging Ships. It has been certified by the IMO, contributing Chinese experience to global port green development. The industry standard system has already taken shape, covering LNG fuel, methanol/ethanol, hydrogen fuel, pure battery power and shore power. These standards meet the needs of different shipping regions and types of vessels, providing technical guidance for the application of marine clean alternative fuels in China’s shipping industry (Trivyza et al., 2022).

3.2.2 South Korea

On 15 July 2022, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) and the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF) of South Korea jointly held the launch ceremony for the Comprehensive Project Group for Eco-friendly Ship Lifecycle Innovation Technology Development, announcing an investment of approximately USD 200 million over ten years to advance eco-friendly ship technologies (Nguyen et al., 2025). In response to the IMO greenhouse gas reduction targets and to lead next-generation ship technologies in the global shipbuilding market, the South Korean government aims to develop core zero-carbon propulsion technologies based on hydrogen and ammonia by 2030. These initiatives are designed to consolidate South Korea’s position as a leading nation in the eco-shipbuilding sector and to enable the country to take a leading role in shaping future international standards for eco-ship technologies.

On 15 November 2023, the MOF, responsible for shipping, ports and the marine environment, released the Green Ship Fuel Supply Chain Development Plan (hereinafter referred to as “the Plan”), outlining the vision of building a Northeast Asian green shipping fuel supply hub. Taking 2022 as the baseline year, the Plan sets phased strategic targets in line with global green shipping development trends and energy demand. First, increase the share of green marine fuel supply. By 2027 and 2030, green marine fuels supplied at ports are expected to account for 10% (1.34 million tons) and 30% (4.02 million tons), respectively (compared with the 2022 baseline supply of 1,340 tons; the green marine fuel share in 2023 was 0%). Second, expand the share of green-fueled container ship port calls. By 2027 and 2030, the proportion of container ships using green fuels calling at ports is targeted to reach 10% and 20% by gross tonnage, respectively, aligning with the IMO 2023 greenhouse gas Reduction Strategy. Third, build port storage capacity for green fuels. By 2027 and 2030, total storage capacity for green marine fuels at ports is planned to reach 400,000 tons and 1 million tons, including 600,000 tons of LNG, 200,000 tons of methanol, and 200,000 tons of ammonia (Rehbein et al., 2019).

3.2.3 Japan

Japan, characterized by scarce domestic energy resources, has long prioritized the development of new energy sources. Since the latter half of the 20th century, the Japanese government has repeatedly formulated and released new energy strategies. In terms of standards for marine clean alternative fuels, ClassNK (Nippon Kaiji Kyokai) issued the Guidelines for Gas-fueled Ships (4th Edition) in April 2016 and the Guidelines for Fuel Cell Systems Onboard Ships (1st Edition) in June 2019, providing technical guidance for LNG and fuel-cell-powered vessels. In June 2022, ClassNK released the Guidelines for Ships Using Alternative Fuels, Version 2.0, supplementing the first edition published in 2021. This update added safety requirements for ammonia-fueled ships and revised the “Alternative Fuel Ready” notation. It also updated the safety requirements for ships using ammonia as fuel previously specified in the Guidelines for Ships Using Low-flashpoint Fuels (covering LPG, methanol, ethanol, etc.), including detailed provisions for the installation, control, and safety devices of ammonia-fueled vessels, as well as a comprehensive description of the requirements for ships designed to use marine clean alternative fuels. Furthermore, ClassNK revised the existing “LNG-Ready” class notation to “Alternative Fuel Ready”, outlining the criteria for vessels whose designs and certain installed systems can accommodate future use of marine clean alternative fuels (Chen et al., 2025).

In May 2024, ClassNK issued the Guidelines for Ships Using Alternative Fuels, Version 3.0 (Bilgili, 2023b). According to ClassNK, in addition to safety requirements for ships using methanol, ethanol, LPG, and ammonia as fuels, Version 3.0 introduces new requirements for hydrogen-fueled vessels, providing design guidance for ships adopting marine clean alternative fuels. The guidelines comprehensively specify safety measures for alternative-fueled ships, including installation, control, and safety systems, with the aim of minimizing risks to vessels, crew, and the environment. In the newly published Version 3.0, the provisions of Part GF (incorporating the IGF Code) are regarded as fundamental requirements. Moreover, Section D includes additional requirements specific to hydrogen fuels, such as precautions to prevent explosions due to hydrogen’s flammability and measures to mitigate the potential impacts of hydrogen leaks on crew and the environment (Melnyk et al., 2024).

3.2.4 Singapore

As the world’s largest bunkering hub, Singapore is committed to making sure that alternative marine fuels are available. With the accelerating pace of maritime decarbonization, the country is more committed to establishing regulations and standards for the safe supply of future alternative marine fuels. The Maritime Singapore Green Initiative (MSGI), launched in 2011, aims to minimize the environmental impact of shipping and related activities. On January 1, 2020, MSGI was renewed and extended until December 31, 2024, with four key programs: Green Ship, Green Port, Green Energy and Technology and Green Awareness (Profumo et al., 2025). Between 2017 and 2020, the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) implemented a pilot program to test operational protocols and gain hands-on experience in LNG bunkering. The program included issuing technical references, providing financial incentives for LNG-powered vessels using Singapore’s port, and co-funding the construction of LNG-fueled vessels and bunkering ships to facilitate ship-to-ship LNG bunkering. Singapore’s first commercial ship-to-ship LNG bunkering operation took place in May 2019 (Moshiul et al., 2022). In April 2020, the government released its Long-Term Low-Emissions Development Strategy, outlining a nationwide roadmap toward a low-carbon and climate-resilient future, reaffirming Singapore’s commitment to developing new low-carbon technologies and clean energy for shipping. During Singapore Maritime Week (SMW) 2021, then Minister for Transport Ong Ye Kung announced the establishment of the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonization (GCMD), which was officially launched on August 1, 2021, as the central driving force for Singapore’s maritime decarbonization initiatives (Savas et al., 2023). In the same year, the Singapore Shipping Association (SSA) established a dedicated Alternative Marine Fuels Subcommittee to advance the formulation of related standards. In March 2022, the current Minister for Transport, S. Iswaran, unveiled the Maritime Singapore Decarbonization Blueprint: Working Towards 2050, which identifies seven key focus areas, including future marine fuels, bunkering standards and infrastructure, carbon awareness, carbon accounting, and green financing (Nerheim et al., 2021). Furthermore, as two of the world’s top bunkering ports, Singapore and the Port of Rotterdam signed a Memorandum of Understanding on August 2, 2022, to establish the world’s longest green and digital shipping corridor, jointly addressing the challenges associated with the adoption of marine clean alternative fuels (Hansson et al., 2020).

In 2024, to further address global climate change and promote the sustainable transformation of international shipping, Singapore revised its Maritime Singapore Green Initiative to align with the International Maritime Organization (IMO) 2023 Strategy on the Reduction of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Ships. The revised initiative aims for low-emission and near-zero-emission technologies and fuels to account for at least 5%, and ideally 10%, of international shipping’s energy consumption by 2030 (Mallouppas et al., 2022). The updated Green Port Program (GPP) and Green Ship Program (GSP) came into effect on January 1, 2025. The revision integrates the original GPP into the GSP and introduces a new Green Craft Program (GCP) for port craft. Port tax incentives are provided for low- and zero-emission vessels using renewable fuels and advanced energy systems (Benet et al., 2022). It should be noted that ships previously registered under GPP are required to re-register in order to benefit from these port tax incentives.

3.2.5 European Union

The European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) has been in operation since 2005. In 2013, the European Commission proposed the inclusion of the maritime sector in the EU ETS, followed by the adoption of legislative drafts governing the monitoring, reporting and verification of ship greenhouse gas emissions. In 2018, the EU adopted the latest revision of the EU ETS Directive, mandating the European Commission to regularly review IMO actions and calling for measures to address shipping emissions under either the IMO or the EU framework starting from 2023. In 2019, the newly formed European Commission introduced the European Green Deal, which became the overarching framework for EU climate policy. Since then, the EU has undertaken a series of actions to strengthen its emission reduction targets, including the European Climate Law that came into effect in June 2021 and the still ongoing “Fit for 55” legislative package (Gilbert et al., 2018). On July 14, 2021, the European Commission proposed this “Fit for 55” package, which includes several maritime-related measures: the integration of shipping into the EU ETS; increased demand for renewable and low-carbon marine fuels; maximum limits on greenhouse gas intensity for energy used by ships calling at EU ports to encourage the use of zero-emission technologies while at berth; support for alternative fuel infrastructure; and amendments to the Renewable Energy Directive to accelerate the supply of renewable energy within the EU (Christodoulou and Cullinane, 2022).

In September 2023, the EU adopted the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR), which requires Member States to deploy an adequate number of liquefied methane bunkering points and other infrastructure at core maritime ports of the trans-European transport network by 31 December 2024. Member States are also required to develop national policy frameworks detailing the policies and measures necessary to achieve these targets and submit them to the European Commission by 2024 (Wang et al., 2023).

On 1 January 2024, the EU ETS formally came into force for the maritime sector, requiring all ships of 5,000 gross tonnage and above calling at EU ports to surrender emission allowances based on their verified greenhouse gas emissions (Onishchenko et al., 2022). On 1 January 2025, Fuel EU Maritime Regulation entered into force, mandating a progressive annual reduction in the well-to-wake greenhouse gas intensity of energy used onboard ships. The targets require a 2% reduction by 2025, tightening incrementally to an 80% reduction by 2050, applicable to all vessels of 5,000 GT and above that call at EU ports. Non-compliance is subject to substantial financial penalties.

On 26 February 2025, the European Commission officially released the Clean Industrial Deal, which earmarks over €100 billion to support clean manufacturing within the EU (Al-Aboosi et al., 2021). It places particular emphasis on formulating short- and medium-term measures that prioritize the use of specific renewable and low-carbon fuels in aviation and shipping, accelerate the deployment of charging infrastructure and substantially replace fossil-based materials with bio-based alternatives.

3.2.6 United Kingdom

In February 2019, the United Kingdom released its ambitious Maritime 2050, which outlines maritime environmental policies, regulations, and the development of new technologies and fuels. The strategy aims to position the UK as a key player in shaping environmental regulations within Europe and the IMO, and as an authority on low- and zero-emission shipping (Yuksel et al., 2024). In July 2019, the UK launched the Clean Maritime Plan, which sets out the pathway to zero-emission shipping and provides guidance for ports in developing air quality strategies (Bouman et al., 2017). The plan stipulates that all new vessels ordered for operation in UK waters from 2025 onwards should be designed with zero-emission technologies. In November 2020, the UK government unveiled The Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution, detailing activities and investments to support the transition to net zero (Gilbert et al., 2018). Against this backdrop, the UK initiated the Clean Maritime Demonstration Competition (CMDC). The first round, launched in March 2021, allocated over £23 million to support the design and development of zero-emission vessel technologies and green port initiatives, with 55 projects receiving funding following independent evaluation. The UK Department for Transport launched the second round of the CMDC in March 2022 and established the UK Shipping Emissions Reduction Office. This round provided £12 million for pre-deployment trials and feasibility studies of innovative clean maritime solutions, with the trials starting on May 24, 2022 (Brynolf et al., 2014).

On 25 March 2025, the UK Maritime Administration announced the Marine Decarbonization Strategy, with the goal of making the UK a green energy superpower and promoting economic growth (Maritime decarbonisation strategy and calls for evidence). The strategy set targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30% by 2030, 80% by 2040, and achieve net zero by 2050. Shipping will be incorporated into the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS), with plans to further cut emissions and promote clean fuels and technologies. This strategy forms part of the government’s Plan for Change, unveiled in 2024, which established six major goals.

On 25 April 2025, the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) issued guidelines for the use of ammonia as a marine fuel, marking a “critical step” toward the widespread adoption of marine clean alternative fuels in the UK maritime sector. The disclosure states that released on 16 April 2025, the guidelines have provided a framework for operators, shipyards and classification societies in the design or retrofit of ammonia-fueled vessels.

3.3 discussion

3.3.1 Comparison of regulatory frameworks

Following an in-depth analysis of the regulatory frameworks promoting the green transition in shipping across various countries, it becomes evident that different nations and regions have developed distinct and complementary policy systems based on their unique industrial characteristics, resource endowments, and international positions.

China’s regulatory framework demonstrates a systematic approach. This top-down model excels in efficiently mobilizing resources, creating clear market expectations, and rapidly advancing large-scale industrial applications and standard implementation. South Korea’s policies are distinctly driven by industrial competition, with the core objective of consolidating its dominant position in global shipbuilding. Japan’s regulatory framework is renowned for its technological leadership and rigorous safety standards. Its strength lies in providing globally trusted technical specifications and safety protocols, particularly in comprehensive considerations for high-risk fuels such as ammonia and hydrogen. As the global bunkering hub, Singapore focuses its policies on maintaining its central role in international shipping through pragmatic and open strategies. Instead of pursuing domestic manufacturing, it actively explores future business models for green fuels, safety operational standards, and global certification systems through fiscal incentives, pilot projects, the establishment of international institutions like the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonization, and the creation of “green shipping corridors”. The European Union’s regulatory framework is a typical example of regulatory coercion and market mechanisms. By legislating the inclusion of shipping into the Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and implementing the “Fuel EU Maritime” regulation, it leverages its vast market size to compel the global shipping industry toward decarbonization. The UK’s policy, on the other hand, emphasizes strategic guidance and innovation incubation. Its advantage lies in stimulating industrial innovation and providing technological reserves for long-term decarbonization. However, its limitations include a reduced industrial scale and regulatory influence post-Brexit, and the primary challenge remains how to scale up and commercialize innovations from demonstration projects.

In conclusion, there is no one-size-fits-all perfect regulatory framework. China’s systematic approach, the EU’s regulatory coercion, Japan’s technological rigor, Singapore’s hub-based flexibility, South Korea’s industry-led competitiveness, and the UK’s innovation-oriented strategy collectively form a multi-driven landscape for global shipping decarbonization. The future trend will involve mutual learning and integration of these models, ultimately leading to a multi-layered and global governance system that balances policy constraints, market incentives, technological innovation, and international cooperation.

3.3.2 Geopolitical competition and the dilemma of global standardization

In the process of global shipping’s green transition, the harmonization of international technical standards and regulations is not merely a technical issue, but an extension of strategic competition and geopolitical rivalry among nations. This competition profoundly influences the process and outcomes of standard-setting. The essence of countries vying for dominance in standard development lies in the contest for future global maritime industry leadership, energy security, and economic interests. Dominating international standards paves the way for a country’s own technologies and industries, granting them “first-mover advantage” and “path dependency” in the global market. This “national champion” model, which treats standards as strategic tools, inevitably leads countries to prioritize promoting standards favorable to their own interests in international forums such as the IMO, rather than seeking the technically optimal solution. As a result, the negotiation process becomes fraught with game-playing and compromise, delaying the formation of a globally unified consensus.

From October 14 to 17, 2025, the second special committee meeting of the IMO Marine Environment Protection Committee was held in London. The meeting focused on reviewing and adopting the IMO Net-Zero Framework (NZF) and its subsequent work plan. Representatives from 135 member states participated, engaging in in-depth discussions on key issues related to the global shipping industry’s green transition.

During the deliberation on specific revisions to the NZF text, several developing countries emphasized the challenges and impacts of implementation. They expressed concerns regarding issues such as food security, the accessibility of green fuels and emission reduction technologies, and capacity-building for emission reductions. Countries including Liberia and the Bahamas expressed concerns about the NZF’s impact on their fleets, calling for further review and impact assessment before finalizing the framework. Saudi Arabia, the United States, Russia, and others reiterated their opposition to adopting the NZF at this stage. They argued that the current proposal fails to genuinely reflect multilateralism, would continue to cause division within the IMO, and its implementation would impose burdens on economies and consumers. They recommended conducting a comprehensive and integrated impact assessment of the current proposal and making further improvements. In contrast, EU countries, the United Kingdom, Pacific small island nations, and some African countries voiced support for the adoption of the NZF. They believe the new rules can create economic development opportunities and provide certainty for investments in shipping decarbonization and related fuels. They acknowledged that implementation challenges and impacts exist but argued these could be further addressed and refined through periodic reviews.

One of the key contentious issues at the meeting was the debate over technological pathways, reflecting differing preferences among countries and companies for the “dominant fuel.” The design of carbon pricing and incentive mechanisms could alter which players gain a competitive advantage. Meanwhile, if consistent global rules continue to be delayed, the European Union or several major port states may take unilateral measures, leading to regional regulatory fragmentation. This would not only increase cross-regional transportation costs but also create varying market access barriers in practice. These disputes demonstrate that political maneuvering, extending beyond technical texts, can have a magnified effect on real-world market behavior.

Furthermore, countries’ preferences for alternative fuel technological pathways are influenced not only by technological maturity but are also deeply rooted in their resource endowments, energy structures, and geopolitical strategies. Stringent regulations initially introduced by developed countries, while advancing emission reduction, also carry undertones of trade protectionism and may trigger international conflicts. Therefore, the challenges in coordinating global shipping decarbonization standards stem not merely from technical disagreements but are a direct manifestation of political and economic strategic competition among nations.

3.3.3 Common but differentiated responsibilities and the developing world’s demand for a just transition

The decarbonization of the global shipping industry must pursue environmental benefits while also ensuring equity and inclusivity. Ignoring the vast capacity differences between developed and developing countries and simplistically implementing a “one-size-fits-all” global standard is not only ethically questionable but also practically unsustainable. The principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR), established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), provides an important legal and ethical foundation for building a fair global framework for shipping emission reduction.

Within the International Maritime Organization (IMO) negotiations on emission reduction strategies, the CBDR principle has consistently been a focal point of contention between developed and developing countries. Major shipping nations and developed economies generally emphasize the need for “globally unified standards”, arguing that all ships, regardless of flag state, should comply with the same energy efficiency and carbon intensity rules. Their rationale is to ensure environmental integrity and maintain a level playing field in the global market. Many developing countries, however, insist that historical emissions and existing capacity inequalities must be taken into account. They seek to ensure that they are not forced out of the global shipping system due to transition costs or hindered in their economic development by high compliance expenses. These fundamental differences in stance have made IMO negotiations slow and fraught with compromise, highlighting the difficult political and economic realities inherent in coordinating global standards.