Abstract

While international law theoretically regulates marine pollution by categorizing its sources, such as land-based, ship-based, dumping-related, seabed activities within national jurisdiction, activities in the Area, and atmospheric pollution, practical implementation faces systemic crises. Confined by the framework provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the application of specific international legal norms struggles to address increasingly complex marine pollution issues. This paper adopts UNCLOS as its core framework, integrating relevant international treaties, customary international law, and judicial precedents to systematically examine the interpretive mechanisms and application pathways of general international law in marine environmental protection. Through empirical analysis and comparative studies, this paper elucidates the dynamic evolution of treaty interpretation and explores the judicial application of principles such as the “precautionary principle” and the “common but differentiated responsibilities” principle. This paper aims to advance the legal governance of the marine environment at the international level, offering insights into resolving fragmentation in norms, strengthening enforcement mechanisms, and harmonizing divergent State practices.

1 Introduction

Oceans and seas are vital to life on Earth, regulating climate, sustaining biodiversity, supporting livelihoods and food security, enabling global trade and providing countless ecosystem services (UNESCO, 2024). Yet they face mounting threats from overfishing, pollution, biodiversity loss and climate change. The protection and preservation of the marine environment is not only crucial to the survival of ecosystems, but also a fundamental prerequisite for global sustainable development.

In response to the increasingly severe problem of marine pollution, the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea put forward issues related to marine environmental protection. Compared with the previous fragmented systems in the field of marine environmental protection, UNCLOS represents the first comprehensive statement of international law on this issue (Sohn et al., 2010). Due to the advanced nature of the corresponding provisions in Part XII of UNCLOS, it is regarded as the most powerful comprehensive environmental treaty currently existing or likely to remain so for some time to come (Stevenson and Oxman, 1994). Tommy T.B. Koh argues that UNCLOS, as the core of international maritime law, can be regarded as a “Constitution for the oceans” (Koh, 1985).

However, the praise of the “Constitution for the oceans” does not imply that UNCLOS can be regarded as an international treaty capable of resolving all issues or disputes concerning the law of the sea. David Freestone emphasizes that UNCLOS offers a legal framework for resolving ocean law issues but does not purport to resolve all marine disputes (Freestone, 2012). Michael Wood advocates for viewing UNCLOS as a “living instrument” (Wood, 2016). In fact, when interpreting or applying the provisions of UNCLOS, it is inevitable to invoke the rules of general international law. This is a two-way process, which not only aids in understanding general international law but also enriches the system of rules in the law of the sea.

As a component of international law, general international law is also a body of legal norms governing international relations. As a result of consent, general international law also encompasses commonalities distilled from various sources of law. It serves to express the shared values and collective will of States and other actors in international relations. In practice, general international law functions as a supplementary provision to treaty rules. Numerous international treaties, among others, refer to the term “general international law” and use it as a supplement to the treaty provisions (Such as vienna convention on diplomatic relations). At the same time, general international law serves as a basis for the decisions of various international judicial bodies. Moreover, general international law can serve as a tool for the interpretation and application of rules by international courts and tribunals. Thus, by constructing a multi-layered and cross-sectoral legal framework, general international law plays a fundamental and coordinating role in the protection and preservation of the marine environment.

This paper begins by exploring the foundational theories of general international law, clarifying its core concepts. It attempts to reconstruct and present the procedural steps through which the relevant rules and principles are identified as part of general international law. Next, this paper outlines the core rules and principles of general international law in the field of marine environmental protection and preservation. It seeks to reveal the legal substance and functional roles of these principles in the context of marine environmental protection. Subsequently, this paper analyzes the application of general international law in practice at three levels: national, regional, and global. Finally, this paper discusses the interpretation and development of these principles by international courts and tribunals. It reviews relevant cases from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), analyzing their interpretative approaches to these principles.

2 Methodology

This paper adopts a doctrinal approach to explore the interpretation and application of general international law in the context of marine environmental protection. The doctrinal method focuses on analyzing primary legal sources, such as treaties, conventions, and customary international law, as well as secondary sources, including scholarly articles and judicial decisions, to explore the foundational principles governing marine environmental preservation. This analytical framework enables a detailed and systematic examination of legal rules, their underlying theoretical foundations, and their practical implications for marine environmental preservation.

The analysis is structured around key principles of general international law, particularly those related to marine environmental protection, such as the precautionary principle, the principle of due diligence, the principle of responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage, the polluter pays principle, the principle of international cooperation, and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. These principles are examined to determine their recognition and evolution within international law, specifically as they relate to marine conservation efforts.

To ensure a comprehensive analysis, a variety of primary legal sources were selected. The criteria for selecting case law and treaties were based on their relevance to the core principles outlined above, their impact on the development of marine environmental law, and their inclusion in widely recognized international agreements such as UNCLOS, regional conventions, and key rulings from international courts and tribunals. The selection of these sources reflects their prominence in the development of international legal standards for marine protection and preservation. In addition, secondary sources, including scholarly articles, reports from international organizations, and legal commentaries, were also incorporated to provide context, support, and analysis of the primary legal texts. These secondary sources were chosen for their academic rigor and their ability to shed light on the practical application of international legal principles in diverse regional and national contexts.

This paper employs both analytical and comparative techniques to evaluate the principles of marine environmental protection within the framework of general international law. The analytical technique involves a close reading and interpretation of the primary legal texts, examining how each principle has been articulated and applied in legal practice. The comparative technique contrasts these principles across different legal regimes, including national, regional, and international contexts, to highlight variations in implementation, enforcement, and effectiveness. This comparison is particularly important in understanding how different legal systems approach the integration of international norms into domestic law, and how regional agreements contribute to the broader international legal landscape. By applying these methods, this paper seeks to clarify the evolving role of international legal principles in marine environmental protection, identify existing gaps in the application of these principles, and offer insights into future directions for legal development and cooperation.

3 What is general international law?

3.1 Theories

In the twentieth century, with the development of theories concerning the sources of international law, scholars continued to engage with fundamental issues in international law. In the course of discussing and classifying its various forms, Oppenheim introduced the concept of “general international law” to distinguish it from “special international law” (Oppenheim, 1905). Kelsen regarded general international law as that part of international law comprising principles, rules, and institutions applicable to all States and other subjects of international law globally (Kelsen, 1952). Brownlie argued that general and special international law correspond, in terms of form, to customary law and treaties respectively, as referenced in Article 38(1) of the ICJ Statute (Brownlie, 1995). Cheng emphasized that general international law is essentially equivalent to customary international law (Cheng, 1998). All of these scholars, without exception, pointed out that treaties, as written agreements concluded by States and governed by international law, are by nature only capable of creating legal rights and obligations between the contracting parties.

Tunkin argued that the view of general international law as exclusively customary law, although quite accurate in the era of Vattel, has become outdated (Tunkin, 1958). He further contended that general international law consists of both customary and conventional (treaty-based) norms. While recognizing that customary international law is a component of general international law, Tunkin also emphasized that general multilateral treaties have already become, or are in the process of becoming, part of general international law through the process of codification. Moreover, such general multilateral treaties may become binding upon non-party States through their acceptance as customary norms (Tunkin, 1993). For instance, in the case of the UNCLOS, although the United States is not a party to it, those provisions of UNCLOS that have been identified as reflecting customary international law—particularly with respect to the regime of maritime zones—are nonetheless applicable to and binding upon the United States (Charney, 1983).

Higgins viewed international law as a normative legal system governing transboundary relations, deriving primarily from two sources: contractual law and general international law. Contractual law encompasses both bilateral treaties, which give rise to particular regimes, and multilateral treaties, which establish general regimes—the Charter of the United Nations (UN Charter) being an example of the latter. General international law, according to Higgins, refers to customary rules as evidenced by State practice, and also includes widely accepted general principles. Moreover, she noted that the application of rules of general international law by institutions such as the ICJ and the International Law Commission (ILC) may contribute to the evolution of relevant State practice and customary norms (Higgins, 1963). It is thus evident that, in her view, general international law is distinct from treaty law and constitutes a component of the international legal system. It is primarily composed of rules of customary international law, while also incorporating certain general principles of law.

Yasuaki offers a critical perspective on the widely held view that “general international law” is synonymous with “customary international law”. Customary international law is merely one “form” in which international law may exist, and its applicability may be either limited or universal. By contrast, general international law is defined by its universal binding force. Therefore, equating customary international law with general international law conflates two distinct legal categories—where the former concerns the “form” of law, and the latter concerns its “scope of application”. This conflation, according to Yasuaki, constitutes a conceptual confusion. He further underscores that much of customary international law has historically been shaped by a small number of powerful States. As Oscar Schachter noted, “as a matter of historical fact, most rules of customary international law have been designated by a very few States” (Schachter, 1996). Given that the recognition of a customary rule requires both “state practice” and “opinio juris”, Yasuaki argues that many customary norms developed in the twentieth century lack a legitimate foundation. He proposes a new approach to identifying general international law, and calls for discussions on general international law to move beyond the framework of Article 38 of the ICJ Statute (Onuma, 2010).

These varying perspectives illustrate that general international law remains in a state of ongoing development and expansion. Accordingly, the understanding of general international law should be rooted in the practical needs of the contemporary international community. This paper argues that, at the current stage, general international law is a developing and collective concept that is embedded within the sources of international law. It exists in a dynamic relationship with treaty rules, customary rules, and general principles of law. It represents a body of rules and principles that are binding on all States. In international legal practice, the proper application of general international law depends crucially on those sources. Therefore, the categories of legal sources specified in the ICJ Statute should serve as the ultimate basis for identifying and determining the rules and principles of general international law.

3.2 Identification of general international law

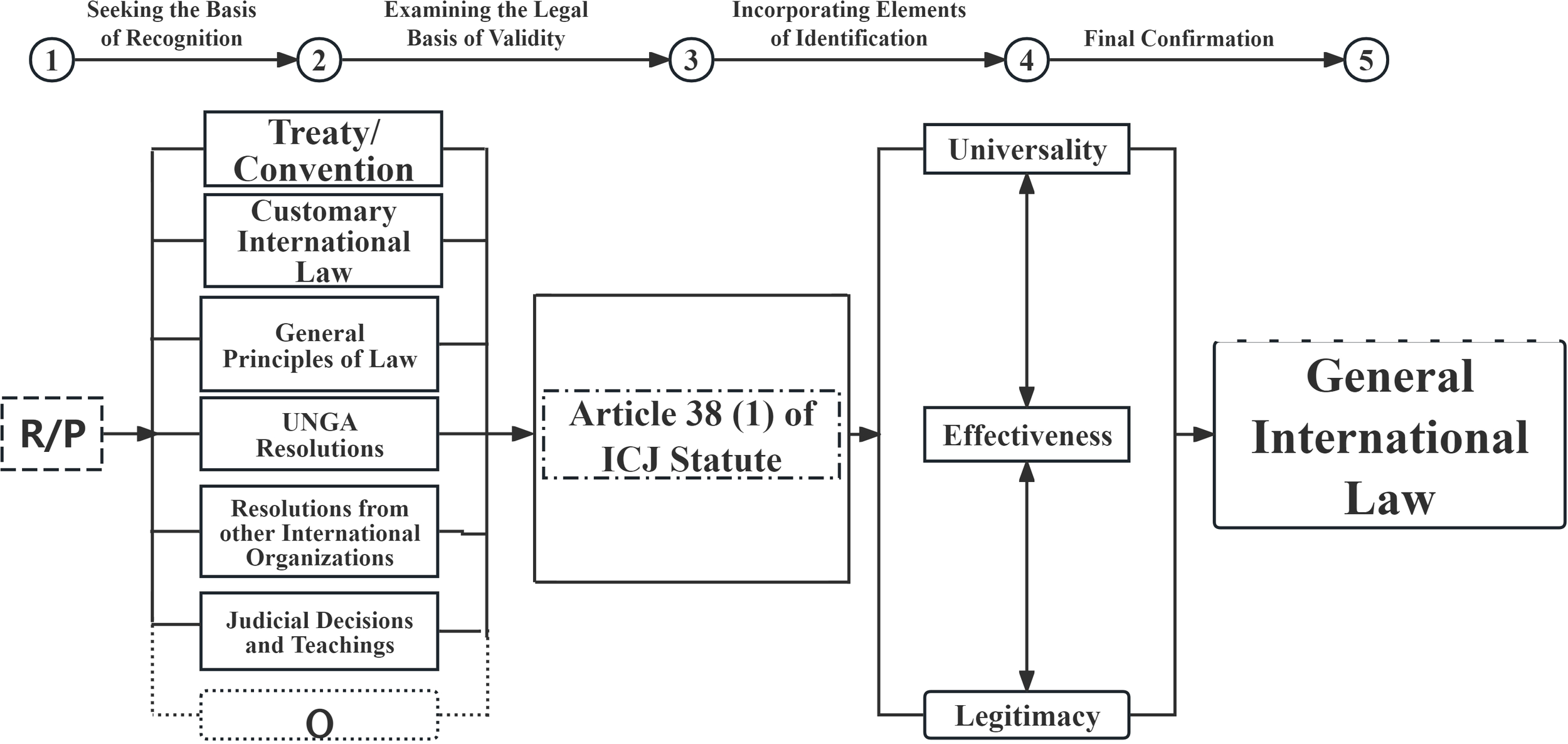

Drawing on the historical evolution of general international law, and taking into account its dynamic and general nature as well as its foundations in the recognized sources of international law, this paper contends that the identification of general international law is best understood as a “pluralistic and evolving” process. Accordingly, this paper presents a procedural framework for the identification of general international law (see Figure 1). This framework is intended to explore and gradually establish a coherent set of criteria for defining general international law.

Figure 1

Identification process of general international law.

Figure 1 consists of five columns. The horizontal sequence from(1)to(5), moving from left to right, represents the sequential stages and steps involved in progressively identifying relevant rules or principles derived from the sources of international law as general international law. The vertical axis indicates the specific content and requirements corresponding to each stage.

In sequence (1), the characters “R/P” stand for “relevant rule or principle”. Since the rule or principle to be identified may originate from various contexts, it is placed within a dashed-line box to indicate its indeterminate and non-specific nature.

The transition from (1) to (2) illustrates the practical need to identify certain rules or principles appearing within relevant bases of recognition as general international law. This need may arise in various contexts: when international law scholars refer to such rules or principles, when different parties invoke them in legal or diplomatic settings, or more significantly, when international judicial bodies apply them in the course of adjudication.

Sequence (2) represents the scope of the bases of recognition for identifying general international law. From top to bottom, the solid-line boxes list various bases through which relevant rules or principles may be manifested, including but not limited to: treaties or conventions, customary international law, general principles of law, UNGA resolutions, other international organizational resolutions, judicial decisions, and teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations. Given the varying probative value of these bases, the likelihood of distilling rules or principles of general international law from each source also differs. To visually reflect this, font size is used to indicate relative weight. In recognition of the evolving nature of international law and its sources (Thirlway, 2019), the character “o” enclosed in a dashed-line box is used to indicate the potential emergence of new bases of recognition in the future. Additionally, each of the bases of recognition in this sequence is interconnected by circular links, illustrating that certain rules or principles may be derived simultaneously from multiple bases.

The transition from (2) to (3) indicates that, once the need for identification is raised, it becomes necessary to further examine the actual connection between the relevant rule or principle and the three generally accepted sources listed in Article 38(1) of the ICJ Statute. This step serves to assess the basis of legal validity for the rule or principle in question.

Sequence (3) represents the source of legal validity. At this stage, the legal effect or applicability of relevant rules or principles is assessed through reference to the three widely recognized sources of international law listed in Article 38(1) of the ICJ Statute. Since general international law is encompassed within, and expressed through, the sources of international law, these sources not only confirm and give form to general international law but also constitute the foundation of legal validity for the rules and principles of international law. Therefore, this stage involves examining the relationship between the relevant rule or principle and the generally accepted sources of international law.

The transition from (3) to (4) indicates that once a relevant rule or principle has undergone the review of its legal validity and is found to be substantively connected to “treaties, customary international law, or general principles of law”, it then proceeds to the stage of matching the necessary and sufficient conditions. At this stage, the rule or principle is assessed to determine whether it simultaneously satisfies the three essential elements: universality, effectiveness, and legitimacy.

Sequence (4) lists the necessary and sufficient conditions for a rule or principle to be considered part of general international law: universality, effectiveness, and legitimacy. In other words, a rule or principle that is closely connected in practice with “treaties, customary international law, or general principles of law” can only be regarded as general international law if it simultaneously satisfies all three of these criteria.

The transition from (4) to (5) indicates that only when a relevant rule or principle fully satisfies all three elements and maintains a substantive connection with the three sources of international law, can it be identified as part of general international law.

In Sequence (5), taking into account the earlier definition of general international law, it is understood as the body of international legal rules and principles that possess the characteristics of universality, effectiveness, and legitimacy, and are binding on all subjects of the international community. This is, in essence, a dynamic and open-ended collective concept. Accordingly, the concept is placed within a box with a dashed upper border to signify its evolving and continuously expanding nature in line with the development of international law.

This section outlines the general process of defining general international law. In practice, particularly in the process of protecting and preserving the marine environment, relevant rules and principles can be incorporated into the broader framework of general international law. These rules and principles play a foundational and coordinating role. Section 3 will further discuss how the principles can be recognized as part of general international law with respect to marine environmental protection and conservation.

4 Rules and principles of general international law in the protection and preservation of marine environment

4.1 Precautionary principle

According to the identification process in Section 2.2, the precautionary principle in sequence (1), is one of the key principles of international environmental law, widely endorsed by the international community and established through treaties and agreements (Crawford, 2012). It is also recognized as one of the three fundamental principles of international environmental law (Tromans, 2001). The transition from (1) to (2) of precautionary principle can be illustrated from many articles contained in conventions and international instruments.

Regarding sequence (2), this principle originates in Article 194(1) of UNCLOS and Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (Rio Declaration). Precautionary principle contained in the convention and international instrument mentioned above also reflects the transition from (2) to (3). Take Article 194(1) of UNCLOS as an example, this provision connect the precautionary principle and one of the generally accepted sources listed in Article 38(1) of the ICJ Statute, which determines the legal validity of precautionary principle and is the core content of sequence (3). In addition, article 14 of the Convention on Biological Diversity refers to the precautionary principle, stating that precautionary measures should be taken to avoid or minimize activities that may have significant adverse impacts on biodiversity.

In international judicial practice, ITLOS, in its Advisory Opinion of the Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area, noted that the incorporation of the precautionary principle into other international treaties and documents has led to a trend of recognizing this principle as part of customary international law (Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area, Advisory Opinion, 2011). It is noteworthy that the inclusion of the precautionary principle in international treaties and its interpretation and application in judicial practice further demonstrate that the principle reflects the characteristics of universality, effectiveness, and legitimacy, which represents the transition from (3) to (4).

Regarding sequence (4), this principle imposes legal standards on state conduct, requiring that a State take all appropriate measures to ensure that activities under its jurisdiction or control do not cause environmental harm to other States or to areas beyond national jurisdiction, or at least to minimize the risk of such harm occurring. In both substantive and procedural terms, the principle is reflected in the obligation to adopt preventive measures, ensure access to information, maintain control over the implementation of activities, and establish emergency response mechanisms in the event of a crisis. Procedurally, it includes obligations such as conducting environmental impact assessments, and ensuring prior notification and consultation (Fisher, 2001).

When available scientific and technical evidence suggests the possibility of significant harm, the precautionary principle requires that States take preventive measures against foreseeable damage (Cameron and Abouchar, 1991). In most cases—especially those involving the effects of hazardous substances on human health or the environment—scientific evidence may be inconclusive. The precautionary principle advocates for a “better safe than sorry” approach, promoting action in the face of uncertainty, as a response to the often passive or indifferent attitude toward environmental pollution observed in international practice (De Sadeleer, 2020a). Therefore, according to the identification process in Section 2.2, this principle can be considered as a part of general international law.

4.2 Principle of due diligence

According to the identification process in Section 2.2, the principle of due diligence in sequence (1) requires States to take necessary measures to ensure that activities under their jurisdiction or control do not cause significant harm to the interests of other States or to those of the international community (Malcolm, 2017a). Although there is currently no universally accepted or precise definition of the due diligence obligation, it is widely recognized within the international community as being closely linked to international legal responsibility and constitutes a duty incumbent upon sovereign States. This obligation is reflected in various international treaties concerning environmental protection, such as the Rio Declaration and UNCLOS, which reflects the transition from (1) to (2).

Regarding sequence (2), this principle is implied in Principle 2 of the Rio Declaration and article 194 of UNCLOS. Principle of due diligence contained in the Rio Declaration and UNCLOS also reflects the transition from (2) to (3). Although the term “due diligence” is not explicitly used in article 194 of UNCLOS, its substance closely aligns with the content of the due diligence obligation, which determines the legal validity of this principle and is the core content of sequence (3). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations established the Agreement on Port State Measures (PSMA) to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing by preventing vessels engaged in IUU fishing from using ports and landing their catches. This agreement includes “responsible fisheries” as a guiding principle, which reflects the duty of due diligence. As a result, PSMA, which came into effect in 2016, sets out specific international legal obligations for port States to combat illegal fishing (Agreement on port state measures (PSMA), 2006).

In international judicial practice, the principle of due diligence has been affirmed, which reflects the transition from (3) to (4). For example, in the Corfu Channel case, the ICJ explicitly held that “it is every State’s obligation not to allow knowingly its territory to be used for acts contrary to the rights of other States” (Corfu channel case, judgement, 1949). This conclusion has been reaffirmed in numerous subsequent decisions in international legal practice. In the Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay case, the ICJ for the first time emphasized the connection between the obligation of environmental impact assessment and the duty of due diligence (Pulp mills on the river Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), judgment, 2010).

Regarding sequence (4), the key focus of the due diligence obligation lies in whether a sovereign State has taken prudent and reasonable measures to prevent the occurrence of adverse consequences. From a legal perspective, due diligence is generally regarded as an obligation of conduct, as it does not, by its nature, require the absolute prevention of harm. Rather, it emphasizes the need to take appropriate preventive measures. However, the due diligence obligation can also be interpreted as encompassing an obligation of result, in the sense of avoiding the occurrence of substantial environmental harm. States are required to take all necessary steps to prevent significant pollution and to act in a manner expected of a “responsible government”, which may include the establishment of consultation and notification mechanisms (Articles 197, 198, 200, 204, 205 and 206 of UNCLOS). In addition, States must also take all necessary measures to prevent the occurrence of substantial pollution and to demonstrate conduct consistent with that of a responsible government (Dupuy, 1980). Therefore, according to the identification process in Section 2.2, this principle can be considered as a part of general international law.

4.3 Principle of responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage

According to the identification process in Section 2.2, the principle of responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage in sequence (1) is a well-established principle of international law, which imposes an obligation on States to avoid causing harm to other States (Malcolm, 2017b). The transition from (1) to (2) of this principle can be illustrated from many articles contained in conventions and international instruments.

Regarding sequence (2), the principle of responsibility not to cause environmental damage to other States has been consistently reaffirmed in subsequent international instruments. This principle is enshrined in the 1972 Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (Stockholm Declaration), which articulates the dual principles of “state sovereignty” and the “duty not to cause environmental harm to other States”, both of which are foundational to international environmental law (Principle 21 of Stockholm declaration, 1972).

The principle contained in the international instruments also reflects the transition from (2) to (3). Take article 195 of UNCLOS as an example. This provision shows the connection between the principle of responsibility not to cause environmental damage to other States and the sources listed in Article 38(1) of the ICJ Statute and determines the legal validity of this principle.

In general judicial practice, this principle was first articulated in the Trail Smelter case and has since served as a foundational precedent guiding State responsibility for transboundary environmental harm (Nagtzaam et al., 2020). The Trail Smelter case involved two arbitral decisions. In the first decision, rendered in 1938, the tribunal held that Canada was liable to compensate the United States for damage caused on U.S. territory. In the second decision in 1941, the tribunal declared: “Under the principles of international law, no State has the right to use or permit the use of its territory in such a manner as to cause injury by fumes in or to the territory of another or the properties or persons therein, when the case is of serious consequence and the injury is established by clear and convincing evidence” (Bjorge and Miles, 2017). This declaration established the Trail Smelter case as the first international judicial precedent affirming the principle that a State must not cause environmental damage beyond its borders. In light of the aforementioned international judicial and legislative practices, it can be argued that this principle reflects the transition from (3) to (4).

Regarding sequence (4), Article 7 of the Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses, which stipulates the “obligation not to cause significant harm”, reflects the principle of responsibility not to cause environmental damage to other States (Article 7 of convention on the law of the non-navigational uses of international watercourses, 1997). Moreover, the Draft Articles on Prevention of Transboundary Harm from Hazardous Activities, completed by the International Law Commission in 2001, was developed based on the fundamental spirit of the “innocent use of territory” principle, particularly as articulated in the Trail Smelter case. Article 3 on “Prevention” states that “the originating state shall take appropriate measures to prevent significant transboundary harm, and, in the event of harm, shall minimize the risks involved” (Article 3 of draft articles on prevention of transboundary harm from hazardous activities, 2001). In contemporary international law, a significant number of conventions and State practices have established the obligation to prevent transboundary pollution. This has become customary international law and is firmly rooted in the positive law framework. Therefore, according to the identification process in Section 2.2, this principle can be considered as part of general international law.

4.4 Polluter pays principle

According to the identification process in Section 2.2, the polluter pays principle in sequence (1) establishes that those who cause environmental harm are responsible for bearing the costs of compensation and remediation (Louka, 2006). The principle has attracted broad support. The connection between the principle and other instruments and conventions reflects the transition from (1) to (2).

Regarding sequence (2), the first international instrument to refer expressly to the polluter pays principle was the 1972 OECD Council Recommendation on Guiding Principles Concerning the International Economic Aspects of Environmental Policies, which endorsed the polluter pays principle to allocate the costs of pollution prevention and control measures to encourage rational use of environmental resources and avoid distortions in international trade and investment (OECD council recommendation on guiding principles concerning the international economic aspects of environmental policies, 1972). In addition, this principle is explicitly affirmed in the principle 16 of Rio Declaration.

The polluter pays principle can also be traced back to several conventions that established minimum civil liability standards for damage caused by hazardous activities (Convention on third party liability in the field of nuclear energy, 1960). The original intent of these conventions was clearly to ensure that the party responsible for causing the harm would compensate the victim. In addition, this principle has also been referred to or adopted in other environmental treaties, including the 1985 ASEAN Agreement on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (Article 10(d) of 1985 agreement on the conservation of nature and natural resources), the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (Article 2(5)(b) of convention on the protection and use of transboundary watercourses and international lakes, 1992), and the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (Article 2(2)(b) of convention for the protection of the marine environment of the north-east atlantic, 1992). The conventions and treaties mentioned above reflect the transition from (2) to (3). The International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation describe the polluter pays principle as a general principle of international environmental law (Preamble of international convention on oil pollution preparedness, response and co-operation, 1990), which determines the legal validity of this principle and is the core content of sequence (3).

Regarding sequence (4), the principle conveys the idea that the costs of pollution should be borne by the polluter. Most developed countries recognize that, “in view of the pressures their societies place on the global environment and of the technologies and financial resources they command, they have a responsibility in the international pursuit of sustainable development” (Principle 6 of rio declaration on environment and development). The practical impact of the polluter pays principle lies in its role in allocating economic obligations for environmentally harmful activities. This is particularly evident in the areas of liability, the use of economic instruments, and the application of rules on competition and subsidies (Sands and Peel, 2012). Therefore, according to the identification process in Section 2.2, this principle can be considered as a part of general international law.

4.5 Principle of international cooperation

According to the identification process in Section 2.2, the principle of international cooperation in sequence (1) is a fundamental norm in international environmental law, reflecting the recognition that environmental challenges, especially those affecting the global commons such as the marine environment, transcend national boundaries and require collaborative efforts among States (De Sadeleer, 2020b). The transition from (1) to (2) of this principle can be illustrated from many provisions contained in numerous international legal instruments.

Regarding sequence (2), principle 24 of the Stockholm Declaration reflects a general political commitment to international cooperation in matters concerning the protection of the environment, and Principle 27 of the Rio Declaration states rather more succinctly that “States and people shall co-operate in good faith and in a spirit of partnership in the fulfilment of the principles embodied in this Declaration and in the further development of international law in the field of sustainable development”. The importance attached to the principle of cooperation, and its practical significance, is reflected in many international instruments, such as the Preamble to the Convention on the Transboundary Effects of Industrial Accidents (Preamble of convention on the transboundary effects of industrial accidents, 1992).

The principle of international cooperation is affirmed in virtually all international environmental agreements of bilateral and regional application, and global instruments, which reflects the transition from (2) to (3). Article 197 of UNCLOS states the importance of international cooperation. In addition, article 5 of Convention on Biological Diversity also sets forth the principle of international cooperation. The above two provisions determine the legal validity of the principle of international cooperation and is the core content of sequence (3).

Practice supporting international cooperation is further reflected in the decisions and awards of international courts and tribunals. In the Mox Plant case, ITLOS affirmed that “the duty to co-operate is a fundamental principle in the prevention of pollution of the marine environment” (The mox plant case, provisional measures, 2001). The same approach was applied by the Tribunal in its provisional measures order in the Land Reclamation case, when it ordered Malaysia and Singapore to cooperate by entering into consultations to establish a group of independent experts to conduct a study on the effects of Singapore’s land reclamation and to propose measures to deal with any adverse effects, and to exchange information (Land reclamation in and around the straits of johor, provisional measures, 2003). The inclusion of the principle of international cooperation in international treaties and its interpretation and application in judicial practice further demonstrate that the principle reflects the characteristics of universality, effectiveness, and legitimacy, which represents the transition from (3) to (4).

Regarding sequence (4), this principle emphasizes that effective protection and preservation of the environment can only be achieved through joint action, information sharing, coordinated policies, and mutual assistance. It acknowledges the interdependence of States in managing shared natural resources and seeks to harmonize national measures to address transboundary environmental risks, fostering a cooperative rather than adversarial approach (Principle 7, 14, 18 and 19 of rio declaration on environment and development). International cooperation enables States to establish common standards, coordinate scientific research, conduct joint monitoring and assessment, and develop contingency plans for emergencies such as oil spills. Moreover, it underpins regional and global frameworks aimed at protecting the marine environment, such as regional seas conventions and protocols (Tanaka, 2016). By promoting dialogue, negotiation, and shared responsibility, the principle of international cooperation not only enhances legal certainty and operational effectiveness but also contributes to the broader goals of sustainable development and the equitable use of ocean resources. Therefore, according to the identification process in Section 2.2, this principle can be considered as part of general international law.

4.6 Principle of common but differentiated responsibilities

According to the identification process in Section 2.2, the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities in sequence (1) is a fundamental norm of international environmental law. It has developed from the application of equity in general international law, and the recognition that the special needs of developing countries must be taken into account in the development, application and interpretation of rules of international environmental law (Sands and Peel, 2018). The transition from (1) to (2) of this principle can be illustrated from many provisions contained in numerous international legal instruments.

Regarding sequence (2), this principle was initially established at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Fitzmaurice et al., 2022). The principle of common but differentiated responsibilities contained in international environmental conventions reflects the transition from (2) to (3). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change provides that the parties should act to protect the climate system on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (Article 3(1) of united nations framework convention on climate change, 1992). Reference to the principle is also made in the Paris Agreement. Although in more muted terms, the Agreement will be implemented to reflect equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances (Article 2(2) of paris agreement, 2015). The above two provisions determine the legal validity of the principle and is the core content of sequence (3).

In its Advisory Opinion on Responsibilities and Obligations in the Area, the ITLOS Seabed Disputes Chamber was presented with arguments to the effect that developing countries should have less onerous obligations of environmental protection, which reflects the transition from (3) to (4) (Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area, Advisory Opinion, 2011). Regarding sequence (4), this principle underpins equitable international cooperation, ensuring that developed countries assume a leading role in addressing global environmental challenges while recognizing the developmental needs of less developed countries. On one hand, all States bear a common responsibility in the protection of the global environment, whether in its entirety or in specific parts. This notion of common responsibility means that regardless of their level of development or geographic location, all countries have an inalienable obligation to safeguard the global environment. On the other hand, the differentiated responsibility aspect of the principle acknowledges that States’ contributions to and capacities for addressing environmental harm vary significantly. Therefore, according to the identification process in Section 2.2, this principle can be considered as part of general international law.

5 Application of general international law by States and international organizations in the protection and preservation of marine environment

At the national level, the incorporation of international legal rules and principles into domestic law facilitates the effective implementation of general international law. In turn, State practice contributes to the progressive development of international legal norms. As intermediary hubs between national jurisdictions and global governance, regional organizations play a dual role. Meanwhile, international organizations, through treaty-making and standard-setting, consolidate national and regional practices, while also providing authoritative guidance for future implementation.

5.1 State practice

In the field of marine environmental protection and preservation, numerous States have incorporated general rules and principles of international law into their domestic legal systems (see Table 1).

Table 1

| Rules and principles | Country | Domestic legislation or activities |

|---|---|---|

| Precautionary principle | China | Article 3 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of the Marine Environment |

| Canada | Preamble of Canada Oceans Act | |

| Norway | Section 9 of Nature Diversity Act | |

| Due diligence | China | Article 12 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Exploration and Development of Deep-Sea Seabed Resources |

| South Africa | Article 2 (4) (i) of National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 | |

| United States | National Environmental Policy Act | |

| Australia | Article 3A (b) of Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 | |

| Principle of responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage | Canada | Article 176 (1) (a) of Canadian Environmental Protection Act |

| Polluter pays principle | Norway | Section 28 of Norway’s Marine Resources Act |

| Principle of international cooperation | Japan | Article 27 of Basic Act on Ocean Policy |

Legislative practices in selected countries.

The precautionary principle has been widely adopted and internalized in national legal systems as a guiding norm for environmental protection and sustainable development. In China, Article 3 of the Law on the Protection of the Marine Environment explicitly establishes a precautionary approach, requiring pollution to be controlled at the source (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China, 2023a). Similarly, the Preamble to Canada’s Oceans Act affirms that precautionary approaches should be widely applied to achieve the sustainable management of marine resources (Department of Justice Canada, 1996a). Norway goes even further, Article 9 of the Nature Diversity Act stipulates that, in the absence of sufficient scientific knowledge, measures must still be taken to avoid irreversible harm to biodiversity (Ministry of the Environment of Norway, 2009).

The principle of due diligence requires States and relevant responsible entities to take all reasonable measures within their jurisdiction to ensure that activities under their control do not cause undue harm to the environment. This principle has been increasingly reflected in national legislation. For instance, Article 12 of China’s Law on the Exploration and Development of Deep-Sea Seabed Resources mandates that contractors must employ advanced technological methods to prevent or mitigate environmental damage to the marine ecosystem (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China, 2016b). Similarly, Section 2(4)(i) of South Africa’s National Environmental Management Act stipulates that environmental decision-making must include a comprehensive assessment of social, economic, and environmental impacts to ensure the sustainability of development initiatives (South Africa Government, 1998). This principle highlights the importance of proactive risk identification and management in environmental governance.

The Principle of responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage is a foundational norm in international environmental law. It establishes that, while States enjoy sovereign rights to exploit their own resources, they are under a legal obligation to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause significant harm to the environment of other States. This principle is codified in Section 176(1)(a) of Canada’s Environmental Protection Act, which stipulates that, where a substance is released into Canadian waters and may adversely affect another country, the competent authority must take appropriate measures (Department of Justice Canada, 1999b). This legislative example illustrates a clear legal framework for preventing and responding to transboundary pollution, underscoring the interrelationship between state responsibility and international cooperation in environmental governance.

The polluter pays principle embodies an economic liability mechanism for environmental harm. Under this principle, the party responsible for pollution is required to bear all or a substantial portion of the costs associated with environmental restoration and remediation. It serves as a crucial tool for achieving environmental justice and ensuring the efficient allocation of environmental resources. Article 28 of Norway’s Marine Resources Act explicitly prohibits the abandonment of objects in the sea that may endanger marine life. Moreover, it imposes obligations on responsible parties to undertake clean-up measures and provides for corresponding penalties (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2008). By internalizing the costs of environmental damage, this legislative approach promotes behavioral accountability and serves as a strong incentive for compliance with marine environmental standards.

The principle of international cooperation underscores the necessity for States to engage in coordinated efforts when addressing global or transboundary environmental challenges. It promotes the negotiation, conclusion, and effective implementation of international agreements, recognizing that collective action is essential to protect shared environmental resources. Article 27 of Japan’s Basic Act on Ocean Policy explicitly mandates the state to strengthen international cooperation in key areas such as marine resource conservation, prevention of marine crime, and disaster mitigation (Cabinet Office of Japan, 2007). This principle not only facilitates the construction of a global environmental governance framework but also provides an institutional foundation for knowledge sharing, technology transfer, and the implementation of common responsibilities.

These legislative practices demonstrate that, although the formulation and application of international principles may vary across jurisdictions, most countries have established clear statutory provisions that translate these principles into binding domestic legal obligations. This has significantly contributed to advancing global cooperation and practice in marine environmental protection. From precautionary management to transboundary responsibility, from the polluter pays principle to international cooperation, national environmental legislation—while aligning with international norms—also reflects domestic contexts and specific needs, exhibiting a degree of flexibility and innovation. The implementation of these domestic laws not only strengthens each state’s internal environmental accountability but also provides a legal foundation and operational framework for the international community in addressing increasingly severe global environmental challenges.

5.2 Regional practice

The European Union (EU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are representative regional organizations in the fields of regional integration and multilateral cooperation, serving as benchmarks for the two major blocs, the West and the Global South. They incorporate and integrate the rules and principles of general international law into their relevant legal and policy documents to achieve the objectives of marine environmental protection and conservation within their respective regions (See Table 2).

Table 2

| Regional organization | Rules and principles | Articles |

|---|---|---|

| EU | Precautionary principle | Communication on the Precautionary Principle; Article 191 (2) of Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union |

| Due diligence | Article 8 of Marine Strategy Framework Directive | |

| Principle of responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage | Article 2 (1) of Marine Strategy Framework Directive | |

| Polluter pays principle | Para. 2 of Annex of Council Recommendation 75/436/EURATOM, ECSC, EEC of 3 March 1975; Article 191 (2) of Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union | |

| Principle of international cooperation | Article 6 of Marine Strategy Framework Directive | |

| ASEAN | Precautionary principle | Article 11 of the 1985 Agreement on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources |

| Due diligence | Article 14 of the 1985 Agreement on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources |

|

| Principle of responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage | Article 2 of ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution | |

| Polluter pays principle | Article 10 (d) of the 1985 Agreement on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources |

|

| Principle of international cooperation | Article 18 (1) of the 1985 Agreement on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources |

Practices of selected regional international organizations.

As a highly integrated regional international organization, the EU exhibits a highly institutionalized and legalized environmental governance system, where the relevant principles of international environmental law are largely solidified through explicit legislative documents, ensuring their enforceability. Firstly, the EU holds a representative position in the application of the precautionary principle. According to the European Commission’s Communication on the Application of the Precautionary Principle, this principle is not only one of the foundational elements of EU environmental policy but also widely applied in risk management and policy-making for the marine environment. This document provides legal and operational guidance for policy interventions under conditions of scientific uncertainty, explicitly requiring the adoption of preventive measures when there is a potential for serious or irreversible damage, even if certain causal relationships have not been fully established (European Commission, 2000). In addition, article 191 (2) of Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union sets the environmental foundation of all EU marine-related directives, which states “Union policy on the environment shall be based on the precautionary principle and on the principles that preventive action should be taken, that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source and that the polluter should pay” (Treaty on the functioning of the european union).

EU institutionalizes the principles of due diligence and responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage through the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Article 8 of the MSFD requires Member States to conduct an initial assessment of their marine waters based on existing data, highlighting the emphasis on scientific research and systematic evaluations, which reflects the principle of due diligence (Article 8 of marine strategy framework directive). Additionally, Article 2(1) further stipulates that marine environmental policies should account for the transboundary impacts on third countries, thereby strengthening the legal foundation for Member States’ environmental responsibilities both within and outside the region (Article 2(1) of marine strategy framework directive). In terms of economic principles, the EU established the polluter pays principle as early as 1975 through the Council Recommendation (Council recommendation, 1975). This principle requires the polluters to bear the costs of pollution control. In practice, it has been concretely implemented through legislation and fiscal policies, providing institutional support for the internalization of the costs associated with marine pollution management. Moreover, Article 6 of the MSFD explicitly states that Member States should coordinate their governance actions through “existing regional cooperation mechanisms, including Regional Sea Conventions”, thereby concretely embodying the principle of international cooperation in EU marine environmental governance. This provision requires Member States to make full use of international platforms and mechanisms when formulating and implementing marine strategies, and to engage in coordinated and joint actions with countries both within and outside the region (Article 6 of marine strategy framework directive).

In contrast to the EU, ASEAN’s legal framework primarily relies on soft law, with its environmental governance mechanism emphasizing respect for sovereignty, consensus-building, and flexible responses. Nevertheless, ASEAN has gradually incorporated the core principles of international environmental law in several of its documents. Regarding the precautionary principle, Article 11 of the ASEAN Agreement on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources states that Parties should strive to control pollution emissions and establish control measures based on the environmental carrying capacity (Article 11 of the 1985 agreement on the conservation of nature and natural resources). While the term precautionary principle is not directly used, the concept of taking preventive measures in the face of potential pollution risks is clearly reflected. As for the due diligence principle, Article 14 stipulates that activities which may cause significant impacts on the natural environment should undergo prior assessments wherever possible, and preventive and remedial measures should be taken based on the assessment results (Article 14 of the 1985 agreement on the conservation of nature and natural resources).

In addressing transboundary environmental damage responsibility, ASEAN adopted the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution in 2002. Article 2 of the agreement emphasizes that haze pollution caused by land and forest fires should be prevented through national actions and regional cooperation (Article 2 of ASEAN agreement on transboundary haze pollution). Although the focus of this agreement is not on marine environments, the transboundary responsibility framework it establishes offers institutional insights for the governance of other types of regional environmental pollution. Regarding the polluter pays principle, Article 10(d) of the ASEAN Agreement on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources stipulates that, to the extent possible, the initiators of activities leading to environmental degradation should bear responsibility for prevention, control, and remediation (Article 10 (d) of the 1985 agreement on the conservation of nature and natural resources). Additionally, according to Article 18(1), ASEAN has established a clear international cooperation obligation (Article 18 (1) of the 1985 agreement on the conservation of nature and natural resources). This principle embodies a significant collectivist character, reflecting the region’s emphasis on collective action grounded in the equality of sovereignty. It facilitates policy coordination and institutional integration within the region, while also enabling ASEAN to participate in global environmental governance processes with a unified voice.

These organizations, through the formulation of regional legal documents and policy frameworks, not only advance the localization and institutionalization of core principles of international law but also, to some extent, contribute to the general development of international law through the accumulation of regional consensus and the feedback of experiences.

5.3 Global practice

At the international level, rules and principles of general international law concerning marine environmental protection and conservation are embedded in numerous treaties and declarations (see Table 3).

Table 3

| Rules and principles | Conventions | Provisions |

|---|---|---|

| Precautionary principle | UNCLOS | Article 194(1) |

| Rio Declaration | Principle 15 | |

| Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes | Article 2(5)(a) | |

| Convention on Biological Diversity | Preamble | |

| United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change | Article 3(3) | |

| Due diligence | UNCLOS | Article 194(2) (3) |

| Rio Declaration on Environment and Development | Principle 2 | |

| Principle of responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage | UNCLOS | Article 195 |

| Rio Declaration | Principle 2 | |

| Stockholm Declaration | Principle 21 | |

| UN Charter | Article 74 | |

| Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States | Article 30 | |

| Polluter pays principle | Rio Declaration on Environment and Development | Principle 16 |

| Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes | Article 2(5)(b) | |

| 1989 OECD Council Recommendation on the Application of the Polluter-Pays Principle to Accidental Pollution | Paragraph 4 of Appendix | |

| Principle of international cooperation | Stockholm Declaration | Principle 24 |

| Rio Declaration | Principle 27 | |

| Convention on Biological Diversity | Article 5 | |

| Principle of common but differentiated responsibilities | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change | Article 3(1) |

| Rio Declaration | Principle 7 | |

| Paris Agreement | Article 2(2) |

Some global practice.

As one of the earliest documents to establish the fundamental principles of modern international environmental law, the Stockholm Declaration affirms the principle of balancing national sovereignty with environmental responsibility. It states that when using their own resources, States should ensure that their actions do not cause harm to the environment of other states or areas beyond their national jurisdiction (Principle 21 of stockholm declaration). Principle 24 reflects the principle of international cooperation, emphasizing that the international community should work together, through multilateral or bilateral mechanisms, on an equal footing to address environmental challenges collectively (Principle 24 of stockholm declaration).

As the most authoritative international treaty in the field of maritime law, UNCLOS establishes a systematic legal framework for marine environmental protection and conservation. Article 194(1) of UNCLOS enshrines the precautionary principle, requiring States to take all necessary measures to prevent, reduce, and control all forms of marine pollution, even when scientific evidence is not yet sufficient (Article 194(1) of UNCLOS). Simultaneously, Articles 194(2) and 194(3) reflect the due diligence principle, obligating States to exercise a high degree of care and sustained effort when implementing environmental protection measures (Article 194(2) and (3) of UNCLOS). Furthermore, Article 195 reaffirms the principle of responsibility not to cause transboundary environmental damage, stipulating that States must not transfer pollution to other countries or to areas beyond their jurisdiction when preventing marine pollution (Article 195 of UNCLOS). This establishes the obligation for States to prevent their activities from causing harm to the environment of other States.

The Rio Declaration, as a soft law document, does not have legal binding force but plays an important guiding role in the development of principles in international environmental law. Principle 2 embodies the dual requirements of due diligence and no-harm responsibility for transboundary environmental damage, emphasizing that while states have sovereignty over resource development, they also bear the responsibility not to cause harm to the environment of other states or the global environment. Principle 7 articulates the common but differentiated responsibilities principle, stressing that developed countries should bear greater obligations in environmental protection. Principle 15 explicitly defines the application of the precautionary principle, stating that when there is a threat of serious or irreversible damage, preventive measures should not be delayed due to scientific uncertainty. Principle 16 establishes the polluter pays principle, requiring states to use economic instruments to internalize environmental costs. Principle 27 introduces the principle of international cooperation, calling on states to cooperate in good faith and with a spirit of partnership to jointly promote sustainable development.

Additionally, the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes and the OECD Council Recommendation on the Application of the Polluter-Pays Principle to Accidental Pollution both establish and concretize the precautionary principle and the polluter pays principle, reinforcing proactive management and cost allocation in environmental governance (Article 2(5)(a) of convention on the protection and use of transboundary watercourses and international lakes; paragraph 4 of appendix of OECD council recommendation on the application of the polluter-pays principle to accidental pollution). The Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change further clarify the application scope of the precautionary principle and the principle of international cooperation (Preamble and article 5 of convention on biological diversity; article 3(3) of united nations framework convention on climate change). The Paris Agreement explicitly articulates the common but differentiated responsibilities principle, which reflects considerations of fairness and capacity differences in environmental governance (Article 2(2) of paris agreement). Moreover, Article 74 of the UN Charter and Article 30 of the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States affirm, the obligation of States not to cause transboundary environmental damage, providing political and legal support for the international normalization of environmental responsibility (Article 74 of charter of the united nations; article 30 of charter of economic rights and duties of states).

The international community has gradually established a framework of general international legal rules and principles through a series of legally binding treaties and influential soft law instruments. This normative system reflects a collective effort to strike a balance between environmental protection and the regulation of State conduct in the face of scientific uncertainty, the global nature of marine environmental risks, and disparities in development. It now constitutes an indispensable legal foundation for contemporary international marine environmental governance.

6 Interpretation of general international law by international courts and tribunals in the protection and preservation of marine environment

6.1 ICJ

In the Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay case, the ICJ referenced the Corfu Channel case, explicitly noting that the core of the dispute’s precautionary principle arises from the obligation of due diligence, meaning that each State is required to prevent its territory from being used in actions that may infringe upon the rights of another State. Argentina argued that Uruguay’s environmental impact assessment for the pulp mills did not consider alternative locations nor sufficiently account for the affected population. Furthermore, the mills did not use the best available technology, which, according to Argentina, indicated that Uruguay had failed to meet the required due diligence standard. Additionally, Argentina contended that the burden of proof for the precautionary duty should be reversed, with Uruguay required to demonstrate that the mills would not cause significant environmental harm (Pulp mills on the river Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), judgment, 2010).Uruguay, on the other hand, argued that the convention prescribed an obligation of conduct, not of results, and that it had fulfilled its duty to prevent pollution. Uruguay had conducted a comprehensive analysis of the site’s suitability, ensured that the technology used was in line with international standards, and provided emission data showing compliance with regulatory limits (Pulp mills on the river Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), judgment, 2010).

ICJ concluded that the principle of due diligence encompasses three key requirements: the establishment of appropriate rules and measures, maintaining effective oversight, and ensuring compliance by both public and private operators. In this case, ICJ acknowledged that the duty of due diligence includes conducting an environmental impact assessment. Uruguay had fulfilled its reasonable obligations in terms of site selection and public consultation. Moreover, the technology used and the emission data provided met the established standards, and there was no conclusive evidence to suggest that Uruguay had failed to meet its due diligence obligations (Pulp mills on the river Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), judgment, 2010).

In the Advisory Opinion on the Obligations of States in Respect of Climate Change, ICJ held that the duty of due diligence is central to the standard of conduct for preventing environmental damage. States are required to fulfill this duty through both procedural and substantive elements (Obligations of states in respect of climate change, advisory opinion, 2025). Specifically, this includes the development of scientifically sound emission reduction rules, regulating the emission activities of both public and private actors, and taking precautionary measures when environmental impact assessments are uncertain. ICJ emphasized that a State has an obligation to utilize all available means to prevent significant environmental harm. However, when determining which measures to adopt, a State’s capacity should be a key factor, considering the historical and current emissions, capabilities, and level of development of each country. ICJ also endorsed the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”, recognizing that developed countries should take more stringent measures to fulfill their obligations (Obligations of states in respect of climate change, advisory opinion, 2025).

ICJ explicitly stated that the precautionary principle should apply to measures addressing climate change. To protect the environment, States are required to adopt precautionary approaches broadly, in line with their capacities. When there is a threat of serious or irreversible harm, the absence of full scientific certainty cannot be used as a reason to delay cost-effective environmental measures. States must not ignore potential risks and should take proactive adaptation and mitigation actions in advance. The goals of the Paris Agreement reflect the precautionary principle. States must take precautionary measures based on existing scientific evidence, and cannot remain inactive due to scientific uncertainty (Obligations of states in respect of climate change, advisory opinion, 2025).

6.2 ITLOS

In the MOX Plant case, Ireland argued that, under the precautionary principle, the United Kingdom had the responsibility to prove that the emissions and other consequences of the continued operation of the MOX plant would not cause harm. This principle, Ireland suggested, could assist ITLOS in assessing the urgency of the measures that the UK must take concerning the operation of the MOX plant (The mox plant case, provisional measures, order of 3 december 2001). The United Kingdom, however, contended that Ireland had not provided evidence to show that the operation of the MOX plant would result in irreparable harm to Ireland’s rights or cause significant damage to the marine environment, and thus, in the context of this case, the precautionary principle was not applicable (The mox plant case, provisional measures, 2001). In response, ITLOS ruled that Ireland and the United Kingdom should cooperate and consult in order to exchange further information regarding the potential consequences that the MOX plant’s operation might have on the Irish Sea. Moreover, the Tribunal ordered that the risks or impacts of the plant’s operation on the Irish Sea should be monitored, and, as appropriate, measures should be taken to prevent potential marine pollution from the MOX plant (The mox plant case, provisional measures, order of 3 december, 2001).

ITLOS explicitly stated that the “duty to cooperate, as a fundamental principle aimed at preventing marine pollution, is indeed derived from Part XII of UNCLOS, concerning the protection and preservation of the marine environment, as well as general international law” (The mox plant case, provisional measures, order of 3 december, 2001). This view was echoed in the Land Reclamation in and around the Straits of Johor case and the Advisory Opinion submitted by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission (Land Reclamation in and around the Straits of Johor (Malaysia v. Singapore), Provisional Measures, Order of 8 October 2003, 2003). This demonstrates that, in the view of ITLOS, the duty to cooperate is considered an integral part of general international law, and the principles related to this duty can play a positive role in the protection and preservation of the marine environment.

In the Advisory Opinion submitted by the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law, ITLOS emphasized that the principle of cooperation runs throughout Part XII of UNCLOS, which lays out a series of specific cooperation obligations. This principle is also a fundamental component of general international law regarding the prevention of marine pollution, and it plays a crucial role in mitigating the effects of human-induced greenhouse gas emissions on the marine environment. Almost all participants in the case acknowledged that the duty to cooperate is central to the review of greenhouse gas emissions. Some also argued that regulatory measures and internationally agreed standards are necessary.

In response, ITLOS observed that the duty to cooperate aims to establish a comprehensive framework for the joint protection of the marine environment. This framework should allow for significant flexibility, with the specifics of cooperation—such as rules, standards, and enforceability—left to the discretion of the parties involved. ITLOS further pointed out that UNCLOS specifically requires State parties to cooperate continuously, meaningfully, and in good faith, either directly or through competent international organizations, to prevent, reduce, and control marine pollution caused by greenhouse gas emissions. This includes cooperation in areas such as rule-making, scientific research, information exchange, and the establishment of scientific standards (Request for advisory opinion submitted to the tribunal, advisory opinion, 2015).

In the Advisory Opinion of Responsibilities and obligations of States sponsoring persons and entities with respect to activities in the Area, the Seabed Disputes Chamber argues that, the content of due diligence obligations may not easily be described in precise terms. It is a variable concept and may change over time as measures considered sufficiently diligent at a certain moment may become not diligent enough in light, for instance, of new scientific or technological knowledge. Article 153, paragraph 4, last sentence, of UNCLOS states that the obligation of the sponsoring State in accordance with article 139 of the Convention entails “taking all measures necessary to ensure” compliance by the sponsored contractor. UNCLOS provides some elements concerning the content of the due diligence obligation to ensure. Necessary measures are required and these must be adopted within the legal system of the sponsoring State (Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area, Advisory Opinion, 2011). It can be seen that, in the view of the Seabed Disputes Chamber, the fulfillment of the due diligence obligation usually requires the duty-bearer to take all necessary specific measures.

Regarding the precautionary principle, the Seabed Disputes Chamber observes that it has been incorporated into a growing number of international treaties and other instruments, many of which reflect the formulation of Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration. In the view of the Chamber, this has initiated a trend towards making precautionary principle part of customary international law. This trend is clearly reinforced by the inclusion of the precautionary approach in the standard clause contained in Annex 4, section 5.1, of the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Sulphides in the Area of 2010 (Regulations on prospecting and exploration for polymetallic sulphides in the area of 2010, 2010). In addition, the Seabed Disputes Chamber argues that, according to the article 31, paragraph 3(c), of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, the interpretation of a treaty should take into account not only the context but any relevant rules of international law applicable in the relations between the parties (Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area, Advisory Opinion, 2011). It can be seen that the Seabed Disputes Chamber has adopted an evolutionary interpretation approach, considering the precautionary principle as a general international law principle in the protection and preservation of the marine environment.

7 Conclusion

The practice of marine environmental protection under general international law is far from a simple, linear process of “top-down” or “bottom-up” implementation. Instead, it involves a complex interplay of vertical levels—national, regional, and international—alongside horizontal, bidirectional interactions between various legal actors. This multilayered approach not only reflects the hierarchical structure of rule systems but also encapsulates the dynamic feedback between different levels of legal authority. Such a structure reveals a tension between the fragmentation and integration of international law, as national legislation transposes international principles into binding domestic law, regional mechanisms elaborate on these principles to address local gaps, and international conventions affirm and solidify dispersed practices into universal norms.

Despite this multifaceted approach, significant challenges remain in the effective implementation of general international legal rules and principles concerning marine environmental protection. These challenges include the contradictions between scientific uncertainty and policy responses, inconsistencies in national assessment standards and enforcement capacities, gaps in the attribution of responsibility for transboundary pollution, deficiencies in dispute resolution mechanisms, and a lack of adequate frameworks for defining polluter liability and compensation. Moreover, persistent issues such as insufficient political will and fragmented cooperation mechanisms continue to hinder progress in marine environmental protection.