- Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, Institute for Global Governance Studies, Institute for Marine and Polar Studies, Shanghai, China

In April 2025, China acceded to the Agreement on Port State Measures, marking its active efforts in combating illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. This represents a significant initiative of China to protect the marine ecological environment, achieve sustainable development of fisheries, and deeply participate in global marine governance, while also indirectly responding to the constrains from the United States through its “Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness Partnership”. This manuscript employs dual perspectives from international relations and international law, along with research methods such as literature review, legal provision analysis, comparative analysis, and case study, to examine the positive impacts, risks, and challenges brought by China’s accession to the Agreement. The research result is that China’s accession to the Agreement enables it to enhance the effectiveness of combating IUU fishing, better protect marine biological resources and fishery resources, and is conducive to improving its international image. In order to better fulfill the international obligations, China needs to ensure the coordination of domestic laws such as the Fishery law with the Agreement, fulfill its responsibilities and obligations as a port State, flag State, and developing country, and strengthen port supervision and compliance capabilities. Meanwhile, China also faces risks such as insufficient law enforcement capacity and certain developed states’ discriminatory inspections against Chinese fishing vessels. The research concludes that China should coordinate domestic laws with the Agreement on Port State Measures and other relevant laws and regulations, complete the upgrading and transformation of its domestic fishery industry, fulfill its responsibilities as a port State, flag State, and contracting party, establish standardized law enforcement procedures, improve the capacity of supervision and law enforcement, enhance the institutionalization, informatization, and intelligentization of fishery management, and actively participate in regional and international fishery cooperation. This article further discusses the accession to the Agreement marks China’s transformation from a “rule adapter” to an “rule builder” in global fishery governance, providing a practical path for balancing domestic sustainable fishery development with participation in global governance and constructing a maritime community with a shared future.

1 Introduction: overview of the port state measures agreement: background, significance, and legal status

1.1 Legislative background of PSMA

The Port State Measures Agreement (PSMA) is an international legal instrument developed under the auspices of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). This legal instrument was adopted on the 36th Session of the FAO Conference on November 22, 2009 by Resolution 12/2009 (Ted, 2009) and formally entered into force on June 5, 2016 (FAO, 2016a). As the world’s first legally binding multilateral treaty specifically targeting illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU fishing) (ECNS, 2025), PSMA has been widely recognized by the international community as a robust and effective tool for eliminating IUU fishing activities (FAO, 2024).

As a paradigmatic instrument of “hard law” in the field of international fisheries governance PSMA derives legally binding force for all its Parties from the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT). Pursuant to the VCLT’s core principles—particularly the principle of pacta sunt servanda, which means once the PSMA enters into force for a Party, that Party is legally obligated to perform all the substantive duties prescribed therein.

This legal nature stands in fundamental contrast to the PSMA’s key predecessor: the FAO International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (hereinafter referred to as the “2001 IPOA-IUU”), adopted by FAO in 2001. As a non-binding “soft law” instrument, the 2001 IPOA-IUU lacks mandatory enforcement mechanisms. Its implementation relies entirely on the voluntary commitment and discretionary compliance of States, without imposing legally enforceable obligations. Unlike the PSMA, which establishes clear legal consequences for non-compliance, such as the obligation of Parties to deny port entry to IUU-listed vessels and the requirement to notify relevant flag States and regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) of enforcement actions, the 2001 IPOA-IUU contains no provisions for legal liability or coercive measures against States that fail to implement its guidelines.

In essence, the PSMA’s status as hard law endows it with three distinct advantages over the 2001 IPOA-IUU. First, enhanced legal validity, as its obligations are rooted in treaty law rather than voluntary guidelines. Second, binding force on Parties, which cannot unilaterally evade compliance without violating international law. Third, enforceable consequences, as Parties are required to establish domestic regulatory frameworks to penalize non-compliant vessels and report enforcement actions to relevant international bodies. These attributes address the core limitation of the 2001 IPOA-IUU, dependence on voluntary adherence, and thereby strengthen the global capacity to combat IUU fishing (Andrew, 2016).

1.2 Aims and expectations of PSMA

Currently, IUU fishing accounts for 15–30% of global marine catches annually (FAO, 2024), causing $10–23 billion in economic losses and leading to a 20% decline in key fishery stocks (e.g., tuna, cod) over the past decade (Khan and Jiang, 2024). This poses a severe threat to the sustainable development of fishery resources and marine ecosystems and the integrity of marine ecosystems. The core purpose of the PSMA is to prevent, deter, and eliminate IUU fishing by promoting effective port state measures among contracting parties, thereby cut down the chain of illegal fishing at the stages of port access and management, and ultimately achieving the long-term conservation and sustainable use of marine biological resources.

To meet with its objectives more effectively, the PSMA places special emphasis on supporting developing countries in implementing the Agreement (FAO, 2016b). Through capacity-building initiatives, it assists developing countries to fulfill their obligations as port states and flag states, reflecting the flexibility and diversity of the regime’s design. The functional value of the PSMA extends beyond strengthening the regulation of IUU fishing; it also advances the upgrading of international fishery governance from voluntary commitments to mandatory norms, enabling states to translate political will into concrete and feasible policies and measures.

1.3 Institutional innovation of PSMA

As the first internationally legally binding instrument specifically targeting IUU fishing, the PSMA has unified the global port State control standards. It blocks the circulation chain of IUU-caught fish through a combination of “port access restrictions + standardized inspections + information sharing”, fills the gaps in the traditional flag State control model, and provides a key tool for the sustainable governance of global fisheries (Etty R. Agoes, 2011).

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), seas and oceans are divided into maritime zones under coastal States’ jurisdiction, entitling coastal States to combat IUU fishing within these zones but inherently limiting their regulatory reach to such restricted areas, thus leaving IUU fishing on the high seas and other areas beyond their jurisdiction largely unchecked, a limitation further exacerbated by flag States’ long-standing “non-compliance” in failing to effectively regulate their flagged vessels’ IUU activities (FAO, 2024); while UNCLOS only outlines port States’ obligations from a marine environmental protection perspective without specifying obligations or implementation procedures for fishery resource conservation or IUU fishing prevention and punishment, the PSMA, a critical supplement to UNCLOS that builds on its framework and advances institutional deepening, addresses the ineffectiveness of flag State jurisdiction under UNCLOS, rather than remedying “limitations in maritime jurisdiction division”: it not only imposes binding obligations on flag States to strengthen the regulation of their vessels, but also converts port States’ obligations into enforceable operational norms through detailed provisions, e.g. inspections, denial of port services to IUU vessels, thereby effectively remedying the challenge coastal States face in combating global IUU fishing, especially on the high seas, due to their limited jurisdiction and filling gaps in the international legal framework for IUU fishing management (Judith Swan, 2016).

In addition, the institutional innovation of the PSMA manifests in multiple dimensions. First, it establishes the first global mandatory norms specifically targeting IUU fishing, filling institutional gaps in international fishery governance. Second, it breaks away from the traditional flag state-centric model in fishery governance and strengthens the central role of port states in regulating foreign fishing vessels, forming a “port interception” governance loop. Third, Article 3 of PSMA clearly defines the scope of application as “A Party may, in its capacity as a port State”, and provisions on information exchange, port designation, and inspection procedures uniformly use mandatory language such as “each party shall”, further consolidating its legal nature and legal binding force.

1.4 The application scope of PSMA

The PSMA clearly defines the core obligations that all contracting parties must undertake, forming a comprehensive port state control system. First, designating ports available for use by foreign fishing vessels and notifying such port information to the FAO and other contracting parties. Second, establishing communication channels among states to develop regular information exchange mechanisms with other states and the FAO. Third, conducting statutory inspections of foreign fishing vessels entering their ports and reporting inspection results as required. Fourth, taking follow-up measures based on inspection findings, including denying illegal vessels’ entry or access to port facilities.

The scope of application of the Agreement focuses on the management by contracting parties, acting as port states, of “vessels not entitled to fly their flag”, covering the entire process from a vessel’s application for port entry to its stay in the port. In terms of applicable objects, except for certain exempted artisanal fishing vessels and container ships, all other foreign fishing vessels are required to comply with the Agreement’s provisions, ensuring the precision and effectiveness of the regime’s coverage.

1.5 International impact of PSMA

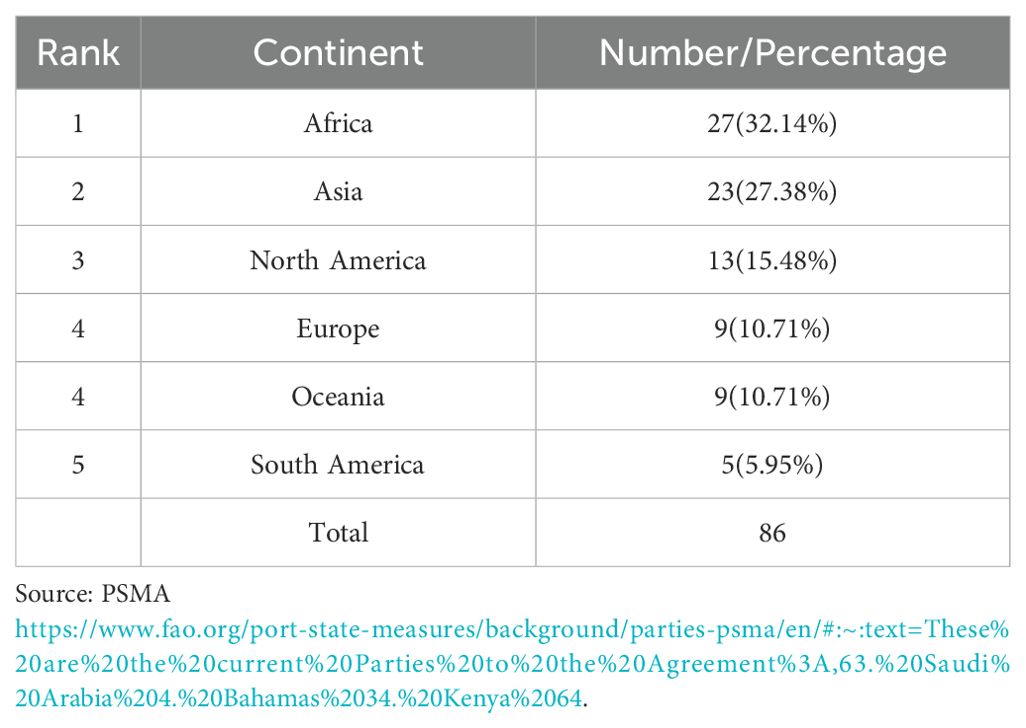

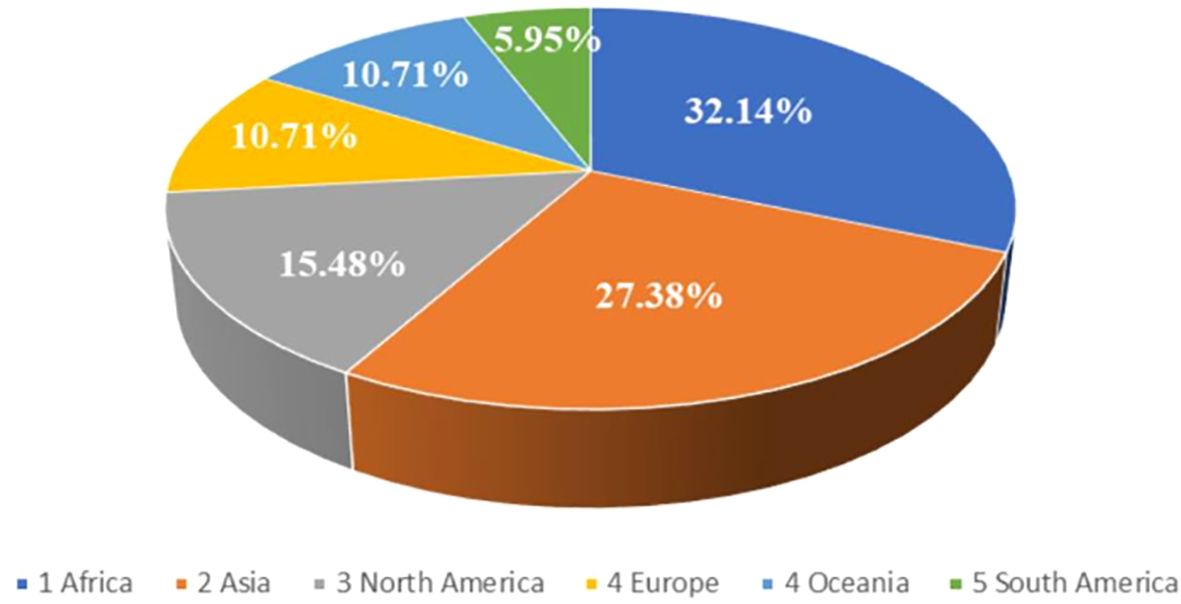

To date, the PSMA has 86 member states. A growing number of countries worldwide have demonstrated their commitment to combating IUU fishing by acceding to the Agreement.

The States of PSMA are as follows:

The implementation of the PSMA varies significantly across different categories of its 86 member states. As a major global fishing nation, the United States has actively engaged in international cooperation to advance the PSMA, using its influence to promote the Agreement’s implementation at the international level. Domestically, the U.S. has a relatively well-developed legal and regulatory framework for fisheries management, including the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, which provides a domestic legal basis for PSMA implementation. Agencies including the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are tasked with port inspection and related functions, equipped with advanced monitoring and law enforcement capabilities as well as a professional workforce. However, some U.S. fisheries stakeholders argue that certain inspection measures under the PSMA have increased operational costs and time burdens, potentially undermining the efficiency of fishing operations. This has, to a certain extent, created resistance to the full implementation of the PSMA within the country.

EU, regarded as a whole, possess a mature fisheries management system. Most member states have proactively implemented the PSMA by incorporating its provisions into their domestic legal and regulatory frameworks. The EU has established the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), which strengthens the supervision of member states’ ports through regional cooperation to ensure that foreign fishing vessels comply with PSMA requirements. In terms of inspection capacity building, EU countries have invested substantial resources to upgrade port inspection facilities and enhance the professionalism of inspection personnel. Ports in several EU countries rank among the world’s leaders in inspection technology and information-based management. Nevertheless, differences in fisheries economic structures and regulatory priorities among EU member states have necessitated extensive internal coordination for consistent PSMA implementation. Additionally, ensuring the effective application of the PSMA in fisheries cooperation with non-EU countries remains a key challenge.

Global South countries face multiple difficulties in implementing the PSMA. Some countries lack a sound legal framework for fisheries management, with inadequate regulations on port state measures, making it difficult to align their domestic systems with PSMA requirements. In terms of inspection capacity, many countries suffer from shortages of professional inspectors, advanced inspection equipment, and technologies, preventing them from conducting comprehensive and effective inspections of foreign fishing vessels. Funding scarcity constitutes another critical constraint, as these countries struggle to allocate sufficient resources to capacity building, technology introduction, and personnel training. To address these challenges, several Global South countries have actively sought international cooperation. Through collaborative programs with international organizations and developed countries, they have accessed technical assistance, financial support, and training opportunities, gradually enhancing their capacity to implement the PSMA (Table 1; Figure 1).

Figure 1. The percentage of member states of each continent. Source: by author https://www.fao.org/port-state-measures/background/parties-psma/en/#:~:text-These%20are%20the%20current%20Parties%20to%20the%20Agreement%3A,63.%20Saudi%20Arabia%204.%20Bahamas%2034.%20Kenya%2064.

Meanwhile, many Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) have also adopted conservation and management measures consistent with the provisions of the Agreement, promoting the governance of IUU fishing from individual national actions to regional coordination and global linkage.

The implementation of PSMA has exerted significant international impacts. First, it has strengthened the legal obligations of countries in IUU fishing governance, facilitating the formation of a multi-stakeholder collaborative governance network involving “port States-flag States-coastal States-RFMOs”. Second, it has reduced institutional barriers in international fisheries trade through unified rules and standards, promoting the standardization of the global fisheries order. Third, it has provided capacity-building support for developing countries, advancing the fairness and inclusiveness of global fisheries governance. Fourth, through information sharing and law enforcement coordination, it has significantly improved the efficiency of identifying and intercepting IUU fishing, offering institutional guarantees for the protection of marine biological resources.

In summary, through clarifying its legal positioning, strengthening mandatory constraints, and refining obligation clauses, the PSMA has established the world’s first specialized hard-law framework for combating IUU fishing. It has become one of the core pillars of the current international fisheries governance system, providing crucial institutional support for advancing the sustainable use of marine biological resources and the modernization of global marine governance.

2 Consideration and discussion of China’s accession to PSMA

2.1 International community’s appeal to China’s accession to PSMA

The international community has called for China’s accession to PSMA (Young, 2025) driven by China’s pivotal position in the global fisheries and port system. Statistics show that, in terms of the total number of visits by fishing and transport vessels, China is home to ten of the world’s busiest ports, with domestic vessels accounting for the vast majority of port visits. The legislative purpose of the PSMA is to require countries to impose stricter controls on foreign fishing vessels applying to enter and use their ports. As a major port nation, China’s participation significantly benefit the global governance of IUU fishing.

Research by the Pew Charitable Trusts further indicates that China is regarded as one of the countries at highest risk in Asia regarding the effective combat against IUU fishing, primarily due to insufficient governance capacity. (Young, 2025). Although the PSMA focuses primarily on regulating foreign vessels, it explicitly requires contracting parties to investigate and penalize their own vessels suspected of unlawful activities. Historically, most countries have focused more on regulating foreign vessels, leading numerous distant-water fishing vessels to return to domestic ports to evade inspections. Given that China operates the world’s largest distant-water and domestic fishing fleets, its serious consideration of accession to PSMA was regarded as a crucial opportunity to alter this situation. (Elaine Young, 2025) Since over 99% of vessels calling at Chinese ports are domestic, including distant-water fleets returning to unload their catches (Eco-Business, 2025). China’s implementation of equivalent supervision and management measures for both domestic and foreign vessels would exert a positive and far-reaching impact on global IUU fishing governance. Additionally, the international community expects China to share real-time data such as port inspection reports with other contracting parties through measures such as adopting global information exchange systems, providing informational and technical support for combating illegal fishing, (Elaine Young, 2025) and further improving the global fisheries regulatory system.

2.2 Analysis of reasons for China’s delayed accession to the PSMA

After the adoption of the PSMA in 2009, China did not accede immediately. The reason for China’s delayed accession to PSMA stemmed from the late development of China’s fisheries management capacity and insufficient preliminary preparations, resulting in a prolonged period of institutional preparation and strategic consideration.

2.2.1 The inadequacy of China’s fishery legislation

In the first decade of the 21st century, the core tasks of China’s fishery sector focused on ensuring food security and fishermen’s incomes, with management priorities centered on “maintaining production” and “preventing inshore overfishing”. Participation in global IUU fishing governance was limited during this period. Domestic fisheries management relied more on maritime patrols, with insufficient emphasis on refined port supervision, making it difficult to meet the PSMA’s rigid requirements such as “port state boarding inspections” and “denying entry to non-compliant vessels”, resulting in significant capacity gaps.

2.2.2 Lack of coordination between Chinese domestic Fishery Laws and PSMA

The PSMA requires port states to implement effective inspection obligations, conduct information sharing, and deny entry to foreign fishing vessels, among other measures. However, China’s Fishery law and other supporting regulations at the time lacked the concept of “port state measures” and failed to clarify procedures for approving foreign vessel entry, inspection standards, or specialized penalty clauses for IUU vessels. Therefore, China’s early accession could have posed implementation risks of “operating without legal basis”.

2.2.3 Weaknesses in China’s regulatory systems and law enforcement capacity

China long maintained a regulatory inertia of “emphasizing maritime oversight over port supervision”, leading to a lack of specialized measures for boarding and evidence collection for foreign vessels at the port frontline. Overlapping responsibilities among multiple departments, including fishing ports, customs, and maritime authorities, often resulted in poor information sharing and redundant inspections. A unified platform covering catch traceability and vessel dynamics was absent, failing to meet PSMA’s requirements for real-time risk analysis and global information exchange. Furthermore, within China’s port management system, fishing ports and non-fishing ports were overseen by different departments, and the fisheries system itself featured separate structures for fishing port management and fisheries administration, which could have imposed additional burdens and pressures on fisheries management reform.

2.2.4 The ambiguity exists in PSMA in combating IUU fishing

The PSMA fails to adopt a precise, legally appropriate definition of IUU fishing, which arouse Chinese concern, as another significant reason for China’s delayed accession to PSMA. Instead, it directly incorporates the ambiguous definition from the non-legally binding IPOA-IUU through Article 1(e), which refers to the activities outlined in paragraph 3 of the 2001 IPOA-IUU. The ambiguity primarily stems from the unclear scope of paragraph 3.3, concerning unregulated fishing and the problematic terms “consistency” and “contravention” in paragraph 3.3.1 of the IPOA-IUU definition. As noted by commentators like Serdy, applying these terms to non-parties of regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) violates the basic principle of treaty law that treaties only bind their parties, not third states without consent. Additionally, paragraph 3.4 of the IPOA-IUU inappropriately exempts certain unregulated fishing from oversight, claiming it “may not violate applicable international law.” However, such fishing still requires regulation under obligations imposed by the Straddling Stocks Agreement and UNCLOS, and this exemption essentially legitimizes RFMOs’ failure to fulfill their regulatory responsibilities (Deji Sasegbon, 2012).

2.3 Key considerations for China’s accession to PSMA in 2025

In April 2025, China formally acceded to PSMA, a result driven by domestic transformation, international responsibilities, and strategic needs. Its core considerations are reflected in the following aspects.

2.3.1 China aspires to promote sustainable fishery

China’s decision to accede to PSMA is a strategic step aligned with its evolving role in global fisheries governance and its goal of promoting sustainable fisheries development. In the early stages of global fisheries governance, China primarily adopted a “rule-adapting” stance, favoring bilateral cooperation to address issues. However, fisheries rights closely tied to national food security, coastal community livelihoods, and core interests like maritime jurisdiction, resource development, and ecological security, have long been a focal point of maritime competition. Thus, engaging with frameworks such as the PSMA is not merely an operational choice, but also a strategic move to pursue and protect maritime rights.

At present, China’s accession to the PSMA reflects a shift in its fisheries philosophy from “production priority” to “ecology priority.” Recognizing that IUU fishing damages global and coastal marine ecosystems while infringing on fishermen’s legitimate rights, China aims to leverage the PSMA to strengthen port supervision, block IUU catches from entering the market, standardize the fisheries industrial chain, and enhance catch traceability and import inspection systems, all in support of high-quality fisheries development. As Liu Xinzhong, Director of the Fishery and Fishery Administration Bureau of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs stated, “Our accession to this agreement this time means that China will assume more international responsibilities in fishery management” (The Government of People’s Republic of China, 2025). Specifically, China will supervise foreign fishing vessels landing at or entering its ports per the PSMA, ensure Chinese fishing vessels comply with the agreement when operating in other countries/economies, and participate in the PSMA’s improvement, enhancement, popularization, and implementation. Ultimately, accession to the PSMA enables China to deepen its engagement in international fisheries governance, crack down on illegal fishing, protect marine fishery resources, upgrade port management, improve the whole-chain supervision system, advance fishery industry modernization, and promote high-level opening-up.

2.3.2 China desires to fulfill major-country responsibilities in global fisheries governance

Liu Xinzhong stated, “Our accession to this agreement on this occasion means that China will assume more international responsibilities in fishery management.” (The Government of People’s Republic of China, 2025) As the world’s largest fisheries producer, trader, and distant-water fishing power, China’s accession to PSMA is conducive to participating in the revision of its rules, enhancing its influence over the rules, improving the compliance capacity of developing countries, and better practicing the concept of a “maritime community with a shared future”. It helps reverse the international perception that “China’s distant-water fleets are at high risk of illegal fishing,” shape the image of a “responsible major fisheries country”, and accumulate experience for participation in other global environmental agreements.

2.3.3 Domestic legal framework has been amended to coordinate with PSMA

The 2024 Draft Amendment to Fishery law of China added provisions aligned with the PSMA, clarifying the legal basis for measures such as “denial of entry” and “seizure of catches”. In accordance with the revised Fishery law, China will establish an effective inter-departmental coordination mechanism, an IUU information platform, and a port inspection network, providing solid support for fulfilling international obligations. The revised Fishery law will place greater emphasis on alignment with relevant laws, enhance port construction and services, stress the protection of aquatic resources, standardize fishing activities, increase penalty intensity, and promote sustainable fisheries development. The amended domestic legislation ensures the legality, sustainability, and environmental friendliness of fishing activities, facilitating the implementation of the PSMA.

Liu Xinzhong stated, the implementation of PSMA is a systematic project that imposes higher and newer requirements on inter-departmental coordination and supervision & law enforcement capabilities (China News Service Website, 2025). Liu Xinzhong stated that to ensure the sound implementation of this work, coordination mechanisms at both the central and local levels have been established. (The Government of People’s Republic of China, 2025).

In the next step, Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs will launch special law enforcement campaigns, arrange for the supervision and inspection of foreign fishing-related vessels, and organize law enforcement capacity training in the near term to further enhance the capacity for fulfilling obligations under the Agreement. Additionally, it will coordinate the relevant resources of universities and directly affiliated public institutions to participate in the review, evaluation of the Agreement as well as subsequent rule negotiations, thereby providing legal, technical and other supporting guarantees for the implementation of the Agreement. (The Government of People’s Republic of China, 2025).

2.4 Accession to PSMA is a strategic counterbalance to the U.S. lead “Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness Partnership”

China’s accession to the Agreement on Port State Measures has achieved certain results in alleviating pressure from the U.S.-led “Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness Partnership” (IPMDA), but it still unable to fully address the core challenges posed by IPMDA. A complex strategic interaction remains between the two.

2.4.1 Reducing international pressure and enhancing international cooperation

In shaping international narratives, the United States has used IPMDA to stigmatize China’s fishing activities as “illegal” in distant waters, aiming to isolate China. By acceding to the PSMA, revising the domestic Fishery law, disclosing port inspection standards, and participating in PSMA meetings, China has demonstrated compliance and transparency in combating IUU fishing, effectively weakening the U.S.’s stigmatizing slander and gaining more international support.

In terms of promoting cooperation, as an open multilateral mechanism, the PSMA can effectively facilitate China’s engagement in fisheries governance cooperation with other countries, including the United States and its allies and partners states. This helps break exclusive “small cliques” such as IPMDA. Meanwhile, advocating an “open and inclusive” international fisheries management order is conducive to gaining the support of developing countries, forming a contrast with the U.S.-led small multilateral groups, and securing broad international backing.

2.4.2 China strives to respond to U.S. geostrategic competition

The PSMA and IPMDA are fundamentally different in nature, aims and expectations. The PSMA focuses on fisheries compliance and resource protection, belonging to non-traditional security cooperation; in contrast, IPMDA centers on intelligence surveillance and strategic containment, covering official ships and military vessels, and is essentially a security cooperation framework. Even after China’s accession to the PSMA, it cannot prevent IPMDA from conducting “normalized surveillance” of Chinese vessels’ activities in nearby and distant waters.

Furthermore, IPMDA’s containment of China is not only based on the pretext of “illegal fishing” but also creates public opinion pressure through politicized narratives such as “coercion in China’s maritime zones”, which are rooted in geostrategic competition and cannot be simply resolved through technical regulatory measures under the PSMA in the fisheries sector. Meanwhile, IPMDA has shown signs of expanding into military security, such as the integration of military intelligence. In comparison, as a fisheries governance mechanism, the PSMA cannot effectively counter tools of military security cooperation or prevent the upgrading of intelligence coordination within the U.S. alliance system.

In summary, while China’s accession to the PSMA has no direct connection with IPMDA, it forms an indirect strategic counterbalance in Indo-Pacific strategic competition. By acceding to the PSMA, China can effectively enhance its image of abiding by international law and the PSMA, counter international stigmatization, promote multilateral cooperation, and alleviate international public opinion pressure-making it an effective measure to address external challenges. However, due to differences in strategic nature and core objectives, even after accession, China still cannot fully counter U.S. geostrategic containment and security control. In the future, China needs to comprehensively respond to U.S. maritime containment through multiple measures, such as deepening PSMA cooperation, promoting regional fisheries coordination, and strengthening multilateral rule-making.

2.4.3 China’s accession is responding to trade barriers of US and EU

Major aquatic product-consuming countries such as the European Union and the United States have set up green trade barriers by enacting and implementing “illegal catch bans”, such as EU IUU Regulation (Council Regulation EC No 1005/2008). Acceding to PSMA and improving the regulatory system will enable China’s aquatic product exports to meet the legality requirements of importing countries, reducing the impact of trade barriers on the fisheries economy. Meanwhile, China can exercise reciprocal supervision over foreign vessels in its capacity as a “port state”, which helps mitigate the negative impact of unilateral EU sanctions on Chinese fishermen and safeguard their legitimate rights.

2.5 International community’s reflections and discussions on China’s accession

China’s accession has aroused widespread attention and discussion in the international community, with the attitudes of various parties as follows:

2.5.1 Reflections of intergovernmental international organizations

Qu Dongyu, Director-General of the FAO, emphasized that China’s accession constitutes a significant milestone in global responsible fisheries governance and sustainable development, and this move reflects the shared determination of member states to combat IUU fishing (FAO, 2025). This fully affirms China’s willingness and ability to play an active role in the global fisheries governance system, highlighting the great significance of China’s accession to promoting the sustainable development of global fisheries.

The PSMA Secretariat highly commended China’s accession to the PSMA, stating that China’s participation has injected strong impetus into the protection of global marine resources and the sustainable development of fisheries (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2025). As a major fishing country with a large fleet of fishing vessels and busy ports, China’s accession can effectively enhance the global port control capacity against illegal fishing, thereby playing a positive role in implementing the objectives of the PSMA and safeguarding the sustainability of global fishery resources.

2.5.2 Reflections of non-governmental international organizations

The Pew Research Center argued that as a country with the world’s largest distant-water and domestic fishing fleets, China’s accession demonstrates its willingness to take more responsibility in global fisheries governance, marking major progress (Pew Research Center, 2025). It further pointed out that China’s decision to join the PSMA sends a strong signal that China is ready to assume a greater leadership role in global fisheries governance and strengthen the supervision of its large-scale fishing operations, which is of great significance to the sustainable development of global fisheries.

Other non-governmental organizations generally believe that China’s accession to the PSMA is conducive to promoting the sustainable development of global fishery resources. China can provide more resources and experience for global fisheries governance and help improve the implementation mechanism of the PSMA, which will have a positive impact on the optimization of the global fisheries governance system and the achievement of sustainable development goals (Eco-Business, 2025).

2.5.3 Reflections of official governments of various states

Mirko Mariano, an Argentine marine conservation expert representing the official perspective of Argentina, noted that China’s accession is a positive step and an important part of combating illegal fishing, and the success of the PSMA depends on the accession of new members (Eco-Business, 2025). This reflects Argentina’s official positive attitude towards China’s accession to the PSMA and its recognition of China’s potential contribution to the global campaign against illegal fishing.

From the perspective of overall international public opinion, many other countries have expressed their welcome and support for China’s accession to the PSMA. Against the backdrop of the continuous decline in global fish stocks, countries have realized that improving fisheries management and effectively governing IUU fishing are crucial to reversing the current negative trend (Elaine Young, 2025). As a major fishing country, China’s accession helps to strengthen the intensity of global fisheries governance and maintain the international fisheries order, thus winning recognition and expectations from many countries.

2.5.4 Reflections of academic community

The academic community has conducted in-depth discussions and analyses on China’s accession to the PSMA from multiple perspectives. Some scholars recognize the positive significance of China’s accession to global fisheries governance, arguing that China, by virtue of its own resources, experience, and large-scale fisheries sector, can play a key role in combating illegal fishing and promoting the sustainable development of fisheries. At the same time, some scholars have pointed out certain areas for improvement in China’s fisheries governance. For instance, they suggest that China should share real-time data through global information exchange systems and further improve port reporting and risk assessment mechanisms to better comply with the requirements of the PSMA, enhance its fisheries governance capacity, and make greater contributions to the sustainable development of global fisheries (Elaine Young, 2025).

In general, the international community holds a positive attitude towards China’s accession to the PSMA and generally recognizes the important role and contribution of China in global fisheries governance. Meanwhile, there are also expectations that China will continue to improve its own fisheries governance system in the process of implementing the PSMA and work together with the international community to promote the sustainable development of global fishery resources.

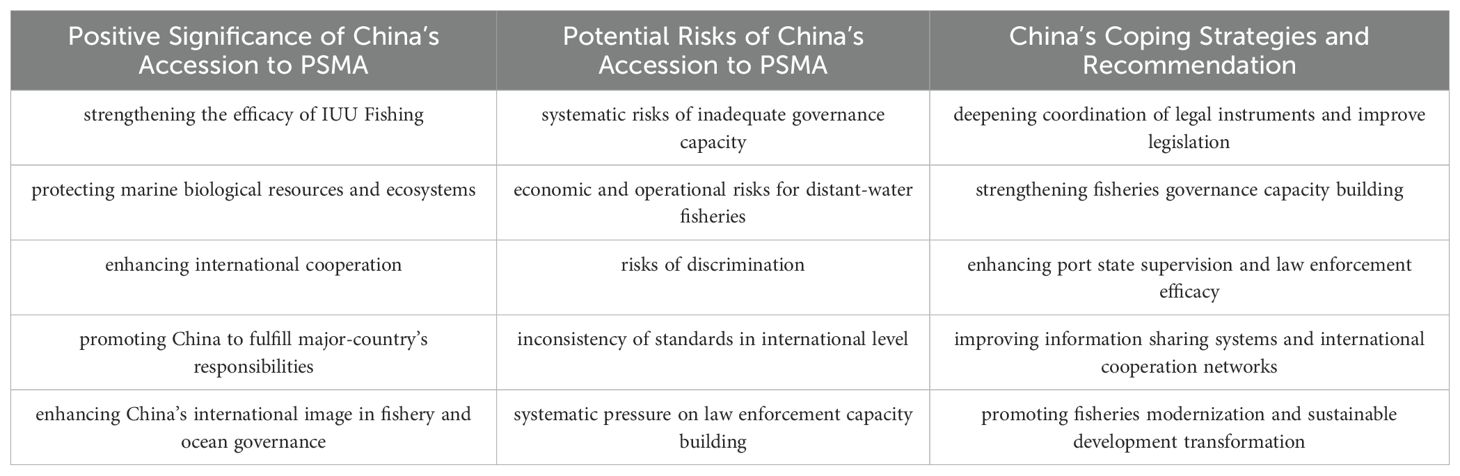

3 Positive significance of China’s accession to PSMA

China’s accession to PSMA marks a critical turning point in global fisheries governance. In particular, the verified international standards for port supervision to its domestic ports in accordance with the PSMA (Eco-Business, 2025). China not only promotes the modernization of its own fisheries management but also exerts far-reaching impacts on global efforts to combat IUU fishing and to safeguard marine ecological security (Eco-Business, 2025). Its positive significance is primarily reflected in the following three aspects.

3.1 Strengthening efficiency of combating IUU fishing and protecting marine biological resources and ecosystems

China’s accession to the PSMA provides institutional guarantees for combating IUU fishing, significantly enhancing the accuracy and effectiveness of fisheries governance. From the perspective of governance mechanisms, the PSMA strengthens the control of illegal fishing through multiple pathways. First, it increases the probability of detecting IUU fishing activities. As a port state, China can rely on port inspections to accurately verify vessel information, enabling more effective identification of problematic fishing vessels compared to traditional maritime patrol models and forming a critical “port interception” defense line. Second, it enhances the intensity of combating illegal activities at the economic level. Port states have the right to deny entry or access to port facilities for vessels suspected of illegal fishing, cutting off the flow of illegal catches into the market at the source, reducing the economic benefits and incentives for fishermen to engage in IUU fishing, and curbing the formation of illegal industrial chains (Le Gallic and Cox, 2006). Third, it compensates for gaps in flag state jurisdiction. Addressing the issue of vessels evading penalties due to inadequate supervision by some flag states, port state inspections form a robust supplementary mechanism, effectively resolving enforcement inefficiencies caused by cross-border jurisdictional complexities. Fourth, it standardizes law enforcement standards (Blaise and Press, 2010). PSMA clarifies minimum standards and law enforcement procedures, which helps improve the quality of China’s port inspections and subsequent law enforcement outcomes, as well as ensuring the standardization and authority of governance measures.

From a global governance perspective, as one of the world’s largest producers, processors, and importers/exporters of fisheries products, China’s accession to the PSMA significantly expands the Agreement’s application and coverage (Eco-Business, 2025). China has numerous coastal ports, with over 99% of vessels calling at these ports being domestic. This means that after PSMA’s implementation, China’s domestic fleets will face stricter inspections upon returning to ports, a mechanism that exerts a significant impact on global efforts to combat IUU fishing (Eco-Business, 2025). By preventing illegal catches from landing and circulating through Chinese ports, it not only ensures the long-term conservation and sustainable use of marine biological resources (National Business Daily Online, 2025) but also plays a vital role in safeguarding food security, promoting stable development of fisheries trade, and ensuring supply chain security, providing solid support for healthy growth of domestic and international marine economies and the well-being of coastal communities. Furthermore, China’s accession is meaningful to govern illegal fishing activities in neighboring waters, promoting regional marine ecological protection cooperation while safeguarding its maritime rights under the UNCLOS (Constantino et al., 2022).

3.2 Enhancing China’s leadership and participation in international cooperation

The PSMA provides an important platform for China to deeply participate in global fisheries governance and assume international responsibilities. As a contracting party to PSMA, China will undertake more international obligations in fisheries management while gaining broader cooperation opportunities. First, deepening collaboration with other contracting parties and regional fisheries organizations through information sharing, joint law enforcement, and other mechanisms to enhance the synergy of global fisheries governance. Second, promoting the upgrading of port infrastructure and management capabilities, leveraging the opportunity of implementing PSMA to improve the port supervision system and enhance the modernization level of fisheries governance. Third, balancing fisheries resource development and protection, and promoting the formation of sustainable fisheries development models in the process of fulfilling resource conservation obligations.

This initiative fully reflects China’s strategic consciousness and responsibility as a major fisheries country (China Rural Network, 2025). Accession to the PSMA aligns with China’s practical need to shift its fisheries governance from a ‘production-first’ to an ‘ecology-first’ approach and demonstrates its determination to actively participate in global governance and promote the building of a maritime community with a shared future. By participating in the implementation and improvement of the rules, China can effectively align with international fisheries governance standards, contribute practical experience to global fisheries resource protection, and enhance its own fisheries management capabilities through international cooperation, achieving mutual promotion between “fulfilling responsibilities” and “capacity building”.

3.3 Enhancing China’s international image in fishery and ocean governance

Against the backdrop of Sino-U.S. strategic competition and the contest for discourse power in global marine governance, China’s accession to the PSMA holds significant strategic symbolic meaning. For a long time, some countries have politicized the issue of illegal fishing, attempting to restrict the development of China’s distant-water fisheries by hyping the “Chinese illegal fishing” narrative. By acceding to the Agreement and committing to strengthening port construction and vessel supervision (Eco-Business, 2025), China directly refutes such unfounded accusations, effectively responds to international concerns about its fisheries governance, and significantly enhances its image and reputation in international fisheries and shipping sectors.

In terms of governance discourse power, China’s accession provides a favorable opportunity to strengthen its influence in global IUU fishing combat and marine governance. As a responsible major country, China’s practices under the Agreement framework offer a reference model for developing countries participating in global fisheries governance, helping to foster a more equitable and reasonable international fisheries governance order. Meanwhile, through active fulfillment of obligations under the Agreement, China’s statements and actions in addressing related issues such as forced labor and human trafficking derived from illegal fishing further consolidate its constructive role in global marine ecological protection and sustainable development, accumulating credibility and discourse power for participation in higher-level global marine governance issues.

4 China’s legal and administrative practice after accession to PSMA

Following its accession to PSMA, China has established a multi-level legal practice system concentrated on fulfilling treaty obligations. Through domestic legal transformation, implementation of multi-role obligations, and participation in international cooperation, it has laid an institutional foundation for the effective domestic implementation of PSMA and contributed practical experience to global fisheries governance (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2025).

4.1 Coordination of domestic laws and international rules

To ensure the effectiveness of PSMA rules in domestic implementation, China has prioritized the coordination of laws and regulations as a core practical task. The newly revised Fishery law adds legal conditions for the entry of foreign fishing vessels, clarifies port state inspection powers, entry refusal procedures, and remedy mechanisms, filling the previous gap in domestic law regarding the concept of “port state measures”. The revised Fishery law not only strengthens the protection of domestic fishery resources but also incorporates key port control provisions targeting IUU fishing. By transforming treaty rules into domestic legal forms, it enables the application of international standards within China.

Simultaneously, China has promoted the alignment of supporting regulations such as the Maritime Traffic Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China, The Port Law of the People’s Republic of China, and Measures of the People’s Republic of China for the Registration of Vessels with international laws including the UNCLOS, International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, and Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. In preparing coordination with international legal instrument, China has further refined law enforcement details and operational procedures, formulating departmental regulations to define IUU fishing scenarios, penalty standards, and inter-departmental collaboration mechanisms, providing clear guidance for law enforcement personnel and ensuring standardized and unified enforcement.

4.2 Fulfilling regulatory obligations as a port state

Pursuant to Part III of the PSMA, entitled ‘Port State Measures’, China has clarified its core regulatory obligations as a port State and carried out substantive practices. In port management, China has designated and published a list of open ports with inspection capabilities, requiring foreign fishing vessels to submit detailed information-such as vessel identification data, fishing licenses, and catch species and quantities-prior to entry. Through information verification, it assesses whether vessels are involved in illegal fishing. For suspected non-compliant vessels, entry may be denied or only allowed for inspection purposes, blocking the circulation of illegal catches at the source.

In inspection implementation, Chinese law enforcement agencies conduct targeted spot checks on foreign fishing vessels are approved entry, focusing on verifying the origin of catches and the authenticity and compliance of licenses. Zhoushan is China’s first port to implement the PSMA. Since the commencement of treaty implementation, it has actively advanced the implementation of various measures. On April 16, 2025, under the guidance of multiple departments, Zhejiang fishery administration, maritime, customs, and border inspection law enforcement agencies jointly conducted a boarding inspection on a Panamanian-flagged fishing refrigerated transport vessel entering Ximatou Fishing Port in Dinghai District, Zhoushan City. This marked the first joint law enforcement inspection after the Agreement took effect in China. Law enforcement officers carefully verified information such as vessel details, shipowner and captain identities, catch species, quantities, origins, and transport documents, and cross-checked against lists of IUU-related vessels provided by RFMOs, finding no evidence of illegal fishing activities (Temple et al., 2022).

Zhoushan is China’s largest base for distant-water fishing production and the largest customs entry port for self-caught distant-water fisheries, accounting for 30% of the nation’s distant-water fishery output and over 65% of national squid fishing catch output. PSMA obligations also apply to Chinese distant-water fishing vessels, requiring them to operate legally and compliantly when entering ports of other countries, submit fishing logs on time, operate in designated areas, and report port entries promptly. As implementation subjects, distant-water fishing enterprises must assume responsibilities, enhance compliance awareness, and integrate into the new global distant-water fisheries management system. This will help drive Zhoushan’s distant-water fisheries toward greater standardization and sustainability, strengthening their competitiveness in the international fisheries market.

By August 2025, Zhoushan Port had conducted 12 boarding inspections of foreign fishing-related vessels, identifying and rectifying 7 issues such as incomplete documents and equipment failures, with no major illegal fishing cases reported. The first inspection was recognized by the FAO as a “model case for developing countries in fulfilling their obligations” and was included in the 2025 report of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Strategy of the PSMA. In addition, the compliance awareness of pelagic fishery enterprises has significantly improved. The on-time reporting rate of fishing logs by fishing vessels increased from 78% to 92% in the first half of 2025, and complaints about illegal operations decreased by 40% year-on-year.

However, as the first Port to implement PSMA, Zhoushan faces several challenges. First, shortage of law enforcement resources. The average daily number of ships entering and leaving Zhoushan Port exceeds 200, yet there are only 32 professional inspectors, resulting in an average annual inspection volume of 112 vessels per inspector, far exceeding the FAO-recommended standard of 50 vessels per inspector, posing a risk of “prioritizing quantity over quality.” Second, obstacles to International Cooperation. Some contracting parties have not timely updated the contact information of port focal points in the Global Information Exchange System, leading to data delays in verifying the qualifications of foreign fishing vessels. For example, during the first inspection in April 2025, data asynchronization from a contracting party prolonged the inspection time by 2 hours. Third, high Adaptation Costs for Fishermen. Some crew members of pelagic fishing vessels are unfamiliar with the technical operations required by the PSMA, such as electronic catch tagging and real-time position reporting, with operational errors accounting for 35% of inspection delays in the first half of 2025.

Zhoushan Port could provide reference to other states. In future, Zhoushan and other port city could transform international agreements into operable local practices through a model of “intelligent supervision + cross-departmental collaboration,” which provides an institutional innovation sample for developing countries to fulfill their fisheries governance obligations. Drawing on the experience of Zhoushan as a reference case, ports across the country can enhance their implementation of the PSMA in the following aspects in the future, including optimize law enforcement resources, deepen international cooperation, and strengthen capacity Building.

4.3 Implementing control responsibilities as a flag state

As a flag state, China has strengthened the ability of supervision over vessels flying its flag in accordance with Part V of the PSMA (FAO, 2016a). In the pre-prevention phase, China provides training for crew members on fulfilling treaty obligations, enabling them to further clarify responsibilities and obligations related to port state measures (FAO, 2025), understand the need to comply with PSMA and legal rules when entering ports of other countries and ensure they fully grasp port state inspection standards and procedures (ECNS, 2025). In the responsive phase, upon receiving inspection reports from other countries regarding suspected IUU fishing by Chinese-flagged vessels, China promptly initiates comprehensive investigations. For confirmed non-compliant vessels, measures such as penalties and suspension of fishing licenses are imposed, with handling results fed back to relevant parties. In long-term management, China has established a full-cycle vessel traceability system, using Automatic Identification System (AIS), electronic fishing logs, and satellite monitoring technology to collect real-time vessel dynamics and catch information, creating “digital identity” files for vessels. Additionally, in accordance with Article 24 of PSMA, it fulfils monitoring, review, and assessment obligations, in order to ensure regularly evaluation of the implementation and progress of PSMA to ensure flag state supervision aligns with global fisheries governance standards.

4.4 Actively fulfilling cooperation obligations as a contracting party

As a PSMA contracting party, China actively fulfils international cooperation obligations. In information sharing, China has established regular information exchange mechanisms with other contracting parties and RFMOs (FAO, 2016b), promptly exchanging vessel violation records, port inspection results, and IUU fishing risk assessment information to provide data support for global IUU fishing governance (FAO, 2024). In capacity building, China participates in the Global Information Exchange System (GIES), supports developing countries in enhancing port inspection technologies and law enforcement capabilities, and promotes the construction of an equitable global fisheries governance framework (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2025).

Under the leadership of the FAO, China will work with other contracting parties to gradually improve and fulfil the obligations stipulated in the PSMA, enabling relevant measures to more effectively combat illegal fishing (FAO, 2025). It will actively share domestic practical experience, facilitating the identification of operational challenges in port state measure implementation and the exploration of solutions. Through such cooperation, China aims to form a multi-stakeholder collaborative governance network involving “port states-flag states-coastal states-RFMO”, contributing to enhancing the effectiveness of combating IUU fishing and better promoting global sustainable fisheries development.

5 Potential risks of China’s accession to PSMA

On one hand, China’s accession to PSMA has brought positive impacts on global fisheries governance and domestic fisheries transformation; on the other hand, during the implementation of PSMA, China still faces multi-dimensional risks and challenges in institutional construction, economic costs, international environment, and capacity building, which may impede its future implementation of the PSMA. These risks stem not only from shortcomings in domestic governance systems but also from the complexity of the international environment for rule implementation. They warrant China’s special vigilance and require systematic analysis to provide a basis for risk response.

5.1 systemic risks of inadequate governance capacity

There is a significant gap between China’s current fisheries regulatory system and the requirements of the PSMA, resulting in both institutional and operational risks.

5.1.1 Imperfections exist in legal, regulatory, and institutional systems

China’s laws and regulations on port supervision of fishing vessels lack specificity and systematisms, and a port state measure system fully aligned with PSMA has not yet been established. Provisions in the Fishery law and supporting regulations regarding port state inspection powers, catch traceability responsibilities, and violation disposal procedures are insufficiently detailed, leaving law enforcement personnel without clear operational guidelines. Additionally, the definition of specific scenarios of IUU fishing remains vague, failing to meet PSMA’s requirement for “precision law enforcement” and potentially leading to issues such as inconsistent law enforcement standards and disputes over compliance identification.

5.1.2 Deficiency in inter-departmental coordination and management capacity

There are overlaps and ambiguities in the division of powers and responsibilities between China’s port management authorities and fisheries administrative departments. Fishing ports and non-fishing ports are supervised by different departments, and within the fisheries system, port supervision departments and fisheries administration departments are also separately established. This multi-agency governance structure for maritime affairs leads to difficulties in data sharing between departments, high coordination costs, and hinders the establishment of the integrated management system required by PSMA. For example, inspections of incoming foreign fishing vessels require simultaneous coordination with port, fisheries administration, customs, and other departments, but existing coordination mechanisms struggle to achieve real-time information exchange, potentially causing inspection delays or regulatory loopholes.

5.1.3 Weaknesses in port infrastructure and technical capabilities

Some Chinese ports lack specialized facilities and technical support meeting the Agreement’s requirements, failing to satisfy core demands such as fishing monitoring and reporting systems and vessel dynamic monitoring. On one hand, most ports are not equipped with key facilities such as dedicated catch traceability equipment and vessel identity verification systems, making it difficult to accurately verify the legality of catch origins. On the other hand, inadequate informatization and intelligentization, coupled with the absence of a full-chain digital supervision platform covering “fishing-landing-circulation”, result in delayed data collection and insufficient sharing, affecting the effectiveness of Agreement implementation.

5.1.4 Economic pressure of long-term investment and transformation

To meet the PSMA’s standards, China needs to upgrade existing ports or build new specialized fisheries ports, equipped with dedicated equipment such as fishing vessel entry-exit management systems and catch disposal facilities, which requires long-term investment of substantial financial and human resources. Meanwhile, fisheries administrative departments face additional pressure to expand law enforcement personnel and provide professional training, including skills in vessel inspection, catch sampling, and communication in English language, which may exacerbate strained administrative resources in the short term. This cost pressure is not only reflected at the government level but also transmitted to fisheries enterprises, increasing their operational burdens.

5.2 Economic and operational risks for distant-water fisheries

The implementation of the PSMA poses challenges to the short-term economic gains and long-term operational models of China’s distant-water fisheries, creating multiple economic risks.

5.2.1 Short-term decline in catch volumes

The PSMA requires fisheries enterprises to upgrade fishing equipment, improve technical standards, and conduct personnel training to meet compliance requirements, directly increasing their management, operational, and technical investment costs. High-risk fishing enterprises need to invest more resources in improving vessel monitoring systems, electronic fishing logs, and other facilities, which may cause short-term supply chain tensions in the industrial chain. Meanwhile, strict port inspections and access restrictions may prevent some catches with potential compliance deficiencies from landing, leading to a short-term decline in distant-water fishing volumes and affecting corporate revenue and fishermen’s livelihoods (Agnew and Barnes, 2004).

5.2.2 Pressure on fishermen’s livelihoods

Fishermen’s livelihoods will face significant impacts in the initial stage of Agreement implementation. Some fishermen relying on traditional fishing may fall into economic difficulties due to rising compliance costs or declining catches, being forced to switch to coastal fishing or aquaculture. Without proper guidance, this transition may exacerbate coastal overfishing, placing additional pressure on coastal ecosystems and contradicting the Agreement’s core objective of “resource conservation.”

5.2.3 Increased overseas operational costs

At the international level, the overseas operational costs of Chinese distant-water fisheries enterprises have risen significantly. On one hand, enterprises must cope with issues such as inspection delays at foreign ports and requirements for additional supporting documents, increasing time and economic costs. On the other hand, to meet the regulatory standards of different countries, they need to invest in upgrading vessel technical equipment and conducting crew training on international rules, particularly in English communication and international compliance skills, further raising operational burdens. Additionally, costs related to communication and coordination in international cooperation and data security maintenance in information sharing pose challenges to the sustainable operation of enterprises.

5.3 Risks of discrimination and inconsistency of standards in international level

The complex international environment for PSMA implementation exposes China to dual risks from rule application and geopolitics.

5.3.1 Risk of discriminatory inspections by developed countries

The high generality and ambiguity of the Agreement’s text provide room for selective law enforcement by some countries. The United States and its allies will continue to conduct discriminatory inspections on Chinese fishing vessels under the pretext of “combating IUU fishing”, including requiring supporting documents beyond the scope of the Agreement, setting stricter review standards on China, in aspects of catch origins and fishing methods, and even expanding extraterritorial jurisdiction through systems such as on-board observer agreements. Such actions not only increase compliance costs for Chinese vessels but may also stigmatize China’s fisheries image through international publicity, restrict the international activities of Chinese distant-water vessels, and trigger international trade frictions.

5.3.2 Divergences in regional implementation standards

Significant differences in PSMA implementation standards across countries and regions create compliance difficulties for Chinese fishing vessels. European and American countries have established strict technical standards and regulatory systems, forming implicit trade barriers (Garcia et al., 2021). Countries in major distant-water fishing regions such as West Africa and South America face weak supervision due to insufficient law enforcement resources and imperfect laws and regulations. Although the small island states are advancing digitalization through electronic Port State Measure (e-PSM) systems, they are still in the initial stage. These standard divergences may lead to Chinese vessels being misclassified as non-compliant in some ports or facing high compliance costs due to inconsistent requirements.

5.4 Systematic pressure on law enforcement capacity building

The Agreement’s high requirements for port state law enforcement capacity have exposed shortcomings in China’s law enforcement systems, technical support, and talent reserves, creating urgent pressure for capacity building.

5.4.1 Lacking law enforcement systems and technical equipment

China has not yet established a sound port supervision and inspection system for fishing vessels, facing challenges such as weak port law enforcement capabilities and a lack of professional law enforcement personnel and advanced technical equipment. Existing law enforcement methods struggle to meet the Agreement’s requirement for “precision supervision”; for example, inadequate technical capabilities in key links such as catch sampling and testing, and vessel identity verification may lead to missed inspections or misjudgments of non-compliant vessels. Furthermore, informatization platforms such as vessel monitoring systems and catch traceability systems have not yet achieved full-chain coverage, with inadequacies in data collection, sharing, and application capabilities affecting law enforcement efficiency and accuracy.

5.4.2 Shortage of law enforcement professional capabilities

The professional quality and international perspective of law enforcement personnel are insufficient to meet the Agreement’s requirements. On one hand, China currently lacks managers and frontline operators proficient in specialized skills such as vessel registration and inspection, and catch testing. On the other hand, domestic port law enforcement personnel have inadequate English communication skills and understanding of international rules, failing to meet the needs of international information sharing and inter-departmental collaboration. The talent shortage undermines law enforcement quality, potentially triggering international compliance disputes and damaging China’s image as a responsible major port country.

5.5 Legal risks of submission to UNCLOS Annex VII arbitration

As is stipulated in paragraph 3 of Article 22, the dispute settlement clauses, “any dispute of this character not so resolved shall, with the consent of all Parties to the dispute, be referred for settlement to the International Court of Justice, to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea or to arbitration”, thus highlighted the possibility of resorting disputes to compulsory arbitration under Annex VII of UNCLOS. As supplement statement of selecting procedures, this article further explained “In the case of failure to reach agreement on referral to the ICJ, to the ITLOS or to arbitration, the Parties shall continue to consult and cooperate with a view to reaching settlement of the dispute in accordance with the rules of international law relating to the conservation of living marine resources.” While the provisions emphasize all parties shall consult on the selection of judicial procedures, in practice, disputes are highly likely to arise among parties regarding whether a dispute should be referred to a third-party judicial body and which specific judicial body would be advantageous to their own country. This leads to controversies in the process of selecting a dispute settlement body. In cases where no consensus can be reached through consultation, China may once again face the risk of having disputes “concerning the combat against illegal fishing” referred to compulsory arbitration under UNCLOS Annex VII, thereby confronting adverse legal risks.

Although China submitted a statement to the Secretary-General of the United Nations in 2006 in accordance with Article 298 of the Convention, the excluded matters are limited to any disputes specified in subparagraphs (a), (b), and (c) of paragraph 1 of Article 298 of the Convention (i.e., disputes involving maritime delimitation, historic bays or titles, military and law enforcement activities, and the performance by the Security Council of its functions under the UN Charter). China does not accept any procedures stipulated in Section 2 of Part XV of the Convention. However, fishery-related matters—specifically, disputes over the implementation of IUU fishing combat measures—do not fall within the categories of disputes China excluded from compulsory jurisdiction under Article 298(1) of UNCLOS, i.e. maritime delimitation, historic bays/titles, military/law enforcement activities. Therefore, China faces the risk of being subjected to compulsory arbitration under Annex VII.

More seriously, the combat against IUU fishing may be packaged as the principal claim by a claimant state for the purpose of establishing jurisdiction. Nevertheless, the true intentions of certain countries with malicious motives lie in the disputes over jurisdiction of maritime areas, the underlying territorial sovereignty disputes, and the so-called “forced labor”, transnational organized crime, and human rights violations issues. These countries may fabricate such issues under the pretext of IUU fishing, politicized the combat against illegal fishing and instrumentalized fisheries governance, aiming to achieve political objectives, slander and defame China in the international public opinion, and place China in an adverse international environment in terms of maritime governance.

5.6 Analysis of causes of risks

The risks faced by China after acceding to the PSMA reflect both domestic governance shortcomings and the complexity of the international rule implementation environment, with roots traceable through three dimensions.

5.6.1 Structural defects in domestic institutional coordination mechanisms

The PSMA requires information sharing and joint decision-making among port management, maritime, fisheries administration, customs, and other departments. However, China’s multi-agency governance structure leads to deficiencies in collaboration. Issues such as ambiguous jurisdiction division, severe information barriers, and low decision-making efficiency hinder the establishment of an integrated regulatory system, leaving the Agreement’s implementation without systematic institutional support (Santos and Lynch, 2023).

5.6.2 Inadequacies in supporting policies for implementation

Effective implementation of the Agreement depends on sound supporting systems, including domestic coordination mechanisms, law enforcement personnel training, and information sharing platforms, but China’s progress in these areas remains lagging. For example, there is a lack of specialized training systems for port state measures, resulting in insufficient understanding and application capabilities of law enforcement personnel regarding the Agreement’s provisions. Information exchange mechanisms have not been standardized, making inter-departmental data interoperability difficult and affecting regulatory synergy and effectiveness.

5.6.3 Capacity limitations as developing countries and insufficient of international support

Although Article 21 of the Agreement provides for technical and financial assistance to developing countries, in practice, the number of assistance requests received by FAO far exceeds its funding capacity, making it difficult for China to quickly address capacity gaps through international support. Meanwhile, rule-making and implementation standards dominated by developed countries may neglect the actual national conditions of developing countries, exacerbating implementation difficulties.

In summary, the potential risks of China’s accession to the PSMA exhibit superimposed characteristics of “domestic governance shortcomings-complex international environment-lagging capacity building”. These risks need to be gradually mitigated through domestic institutional reforms and capacity building, while also promoting fair rule implementation and cooperative support at the international level to achieve a balance between the Agreement’s objectives and the sustainable development of domestic fisheries (Garcia et al., 2000).

6 China’s coping strategies and recommendations

To further enhance the implementation effectiveness of PSMA, promote the modernization of domestic fisheries governance, and improve participation in global marine governance, China needs to formulate systematic countermeasures from multiple dimensions, including legal coordination, capacity building, regulatory optimization, international cooperation, and industrial transformation.

6.1 Deepen coordination of legal instruments and improve legislation

6.1.1 Coordinate PSMA with other international instruments

Article 4 of the PSMA concerning “Relationship with international law and other international instruments,” requires all state parties to comply with the requirement of PSMA, without prejudice to the rights, obligations, and responsibilities of each contracting party under international law; comply with the requirement, responsibilities and obligations in this Agreement in good faith, other acceded agreements, and the rules and principles of international law, and promote the coordination of PSMA with other domestic and international agreements.

The domestic implementation of international treaties is not a mere mechanical application or rigid duplication of rules; instead, it constitutes a process involving the comprehensive application of international law rules. Throughout this implementation process, it is essential to not only grasp the interconnections among different treaties but also consider the infiltrative role of international law principles, such as the due diligence principle, the principle of proportionality, the principle of non-discrimination and fairness, and the principle of transparency.

The due diligence principle denotes the obligation that a state or relevant subject, when conducting acts that may exert impacts on other entities or the international community, shall fulfill a reasonable duty of care and adopt necessary measures to prevent, mitigate, or eliminate potential risks. This principle is frequently embodied in treaty practices within fields such as environmental protection and international investment.

The principle of proportionality requires that the measures adopted by a state, such as regulatory measures and dispute settlement measures maintain an appropriate proportion to the legitimate objectives they intend to achieve. To comply with this principle, three core elements must be satisfied “the means are relevant to the objective, “the means are necessary for the achievement of the objective”, and “the means minimize the impairment of the legitimate rights and interests of the opposing party”. As a pivotal principle in international law, it serves to restrict state power and protect the rights and interests of individuals or other states.

The principle of non-discrimination and fairness encompasses two dimensions: “non-discrimination” and “fairness”. On one hand, the “non-discrimination” dimension mandates that a state shall not impose differential treatment based on unreasonable factors such as nationality, race, or gender. On the other hand, the “fairness” dimension emphasizes that all acts shall conform to the fundamental norms of fairness and justice. These principle functions as a foundational norm in treaties related to fields including international trade and human rights protection (Callum and Papastavridis, 2021).

The principle of transparency requires that when a state formulates and implements domestic rules related to international treaties, or conducts activities under the framework of treaties, including cooperative initiatives, dispute settlement proceedings, it shall disclose relevant information in a predictable and accessible manner. Such disclosure is intended to safeguard the right to information of other subjects and serves as a key principle for enhancing the credibility of the domestic implementation of international treaties.

In practice, China should first adopt a coordinated approach to PSMA and other fishery related legal instrument, including hard law and soft law. Beyond the PSMA, a hard law instrument endowed with explicit legal binding force, “international soft law” documents, which do not possess legal binding effect, also serve a pivotal role in providing policy guidance and technical oversight for global fisheries governance (Pew Charitable Trust, 2025). Specifically, instruments such as the resolutions of the annual United Nations “Oceans and the Law of the Sea” Conference, the United Nations General Assembly resolutions on sustainable fisheries, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development exert substantial influence in delineating objectives, setting agendas, advancing negotiations, and offering action-oriented guidelines for global fisheries governance. The Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, issued by FAO, furnishes fundamental concepts, principles, methodologies, and standards for all entities tasked with the conservation, management, and development of fisheries. Furthermore, the 2001 IPOA-IUU, also promulgated by the FAO, systematically articulates the obligations and corresponding measures that all States are required to undertake in the fight against IUU fishing (FAO, 2024).

6.1.2 Coordinate PSMA with Chinese fishery law