Abstract

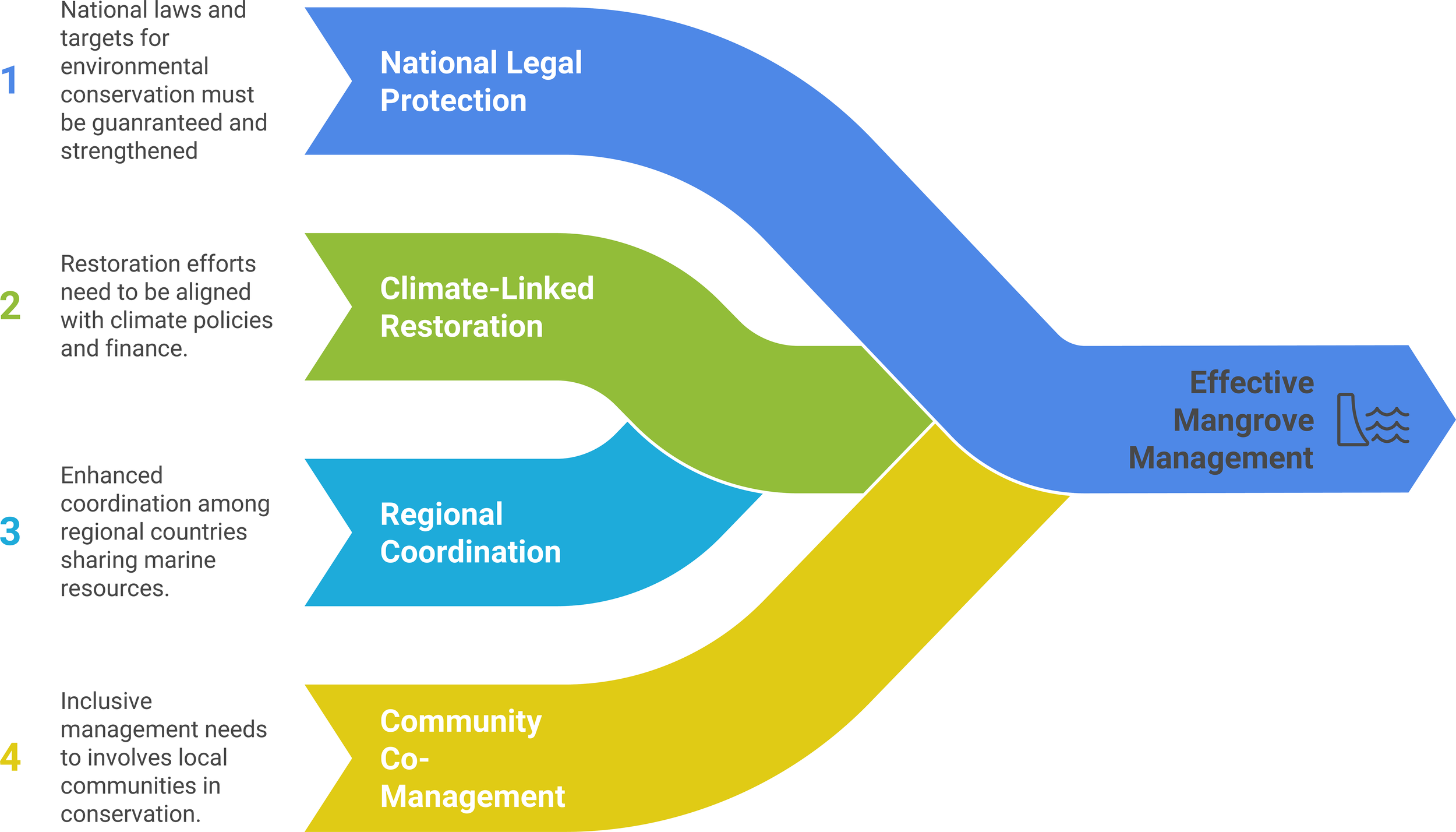

Middle Eastern (ME) mangroves, spatially restricted and fragmented at the arid limit of the biome, underpin shoreline protection, fisheries, and blue-carbon initiatives along rapidly urbanizing coasts. However, global generalisations tend to overestimate their functional capacity, risking context mismatched restoration and overestimated offset potential. We conducted a comprehensive multi-method review across the Red Sea, Arabian/Persian Gulf, and adjoining shores. From peer-reviewed and agency sources, the literature was synthesized across four domains: eco-biophysical dynamics, socio-economics, climate-risk pathways, and governance. The review demonstrated that four primary controls govern distribution and function: freshwater inputs, hypersalinity, heat, and sheltering geomorphology. Avicennia marina dominates as dwarf, slow-growing stands of ~2–4 m, allocating resources below ground on carbonate and nutrient-poor substrates. Vertical accretion is modest ~1–3 mm yr-¹, organic carbon burial is low ~10–15 g C m-² yr-¹, and soil stocks are small ~43 ± 5 Mg C ha-¹ relative to the humid tropics. A wave-energy threshold and micro- to mesotidal ranges constrain the flushing. Sea-level rise (SLR) of 2.92 mm yr-¹, with a projected increase of 39.1 cm by 2100, combined with thermal and salinity extremes, dust burial, and oiling, raises the risk. However, undisturbed soils confer high carbon permanence. Socio-economic benefits, such as nursery support, shoreline defense, and cultural amenities, are large, but enforcement, monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV), and co-management remain uneven. A region-specific framework is most essential. Priorities are to safeguard groundwater-fed refugia, secure retreat corridors, reduce local stressors, and implement stress-matched restoration that replicates resilient features, such as space, sediment, seepage, and shelter, while grounding mitigation in arid-zone MRV and avoided-loss accounting. This study provides a resilience–threat typology and integrated governance framework linking legal protection, climate-linked restoration, regional coordination, and inclusive co-management.

1 Introduction

The Middle East has mangroves that fringe the Arabian/Persian Gulf and Red Sea, which are small in area but ecologically significant nodes in one of the driest seascapes on the planet (Su et al., 2021). They stabilize coastlines, provide food through fisheries, and sequester blue carbon; however, they are susceptible to extreme temperatures, hypersalinity, and low levels of freshwater input (Krauss et al., 2022). National commitments, such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) vow to grow mangroves by 2030 and extensive nurseries along the Red Sea coast of Saudi Arabia, have accelerated these systems into regional policy discussions on climate change and coastal-risk avoidance and mitigation (Ministry of Climate Change and Environment [MOCCAE], 2021; Saudi Green Initiative, 2025). Meanwhile, high coastal development and historical pollution in the Gulf increases their vulnerability (Al-Nadabi and Sulaiman, 2021; Al-Tarshi et al., 2024), which is why a synthesis that models these complexities beyond global generalizations is required.

Although several reviews and technical assessments exist, such as the regional organization for the conservation of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (PERSGA) Red Sea guidance (PERSGA/GEF, 2004), country-focused appraisals, and systematic reviews, coverage remains fragmented across subregions and disciplines. Earlier reviews typically emphasize ecology or distribution, with limited integration of arid-zone biogeochemistry, groundwater–sediment controls, livelihoods, governance performance, and emerging blue-carbon finance. The lack of attention to the dimensions of equity and livelihood is noted in the most recent Western Asia literature review by Yap and Al-Mutairi (2025), even though these are salient dimensions of policies. These gaps are addressed in our review , in which we integrate an eco-biophysical perspective with governance and socioeconomic dimensions in the specific context of the predominantly desert dominated regions we examine.

The fundamental issue addressed in this in-depth review is the comparative mismatch existing between the global mangrove assumptions and the Middle Eastern counterparts. The arid climate has made mangroves in this region nutrient-limited and of dwarf stature (Naidoo, 2006); sediment budgets are dominated by carbonate (Saderne et al., 2018), and carbon burial rates are an order of magnitude lower than those of humid-tropical references (Breithaupt et al., 2012). These facts are highly relevant to realistic blue-carbon accounting for site-appropriate restoration. Further, global averages are overemphasized, which is accompanied by the risk of exaggerated carbon claims and irrelevant plantation objectives. Simultaneously, the rate of development, temperature rise, and rise in sea levels create pressure by reducing the available populations to settle with limited opportunities to migrate landward (Spencer et al., 2016; Saintilan et al., 2020). Thus, a compelling, locally specific evidence base is needed to refocus expectations, target pristine freshwater-mediated refugia, and match restoration to hydro-geomorphic boundary conditions.

In this backdrop, we have synthesized a comprehensive review that integrates peer-reviewed publications with official data repositories, regional agencies, and national climate reports to assemble eco-biophysical characteristics, sedimentology and hydrology, biogeochemistry, socio-economic values, climate-risk pathways, and governance tools across key ME nations where mangroves can be found, including Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Yemen. This integration will result in the generation of restoration, protection, and MRV of blue carbon efforts in arid environments to create decision-relevant baselines and thresholds.

This review article aims to (i) synthesize and critically evaluate available eco-biophysical and biogeochemical data on ME mangroves against a backdrop of heat and salinity stress; (ii) quantify what can or cannot be paralleled between global mangrove paradigms and arid coasts and, correspondingly, the implications on blue-carbon accounts; (iii) map a region-specific agenda on adaptation, restoration, and monitoring against national climate commitments and without falling into easy-one size fits all variance; and (iv) integrate socio-economic benefits and equity considerations with governance performance to identify actionable solutions.

2 Materials and methods

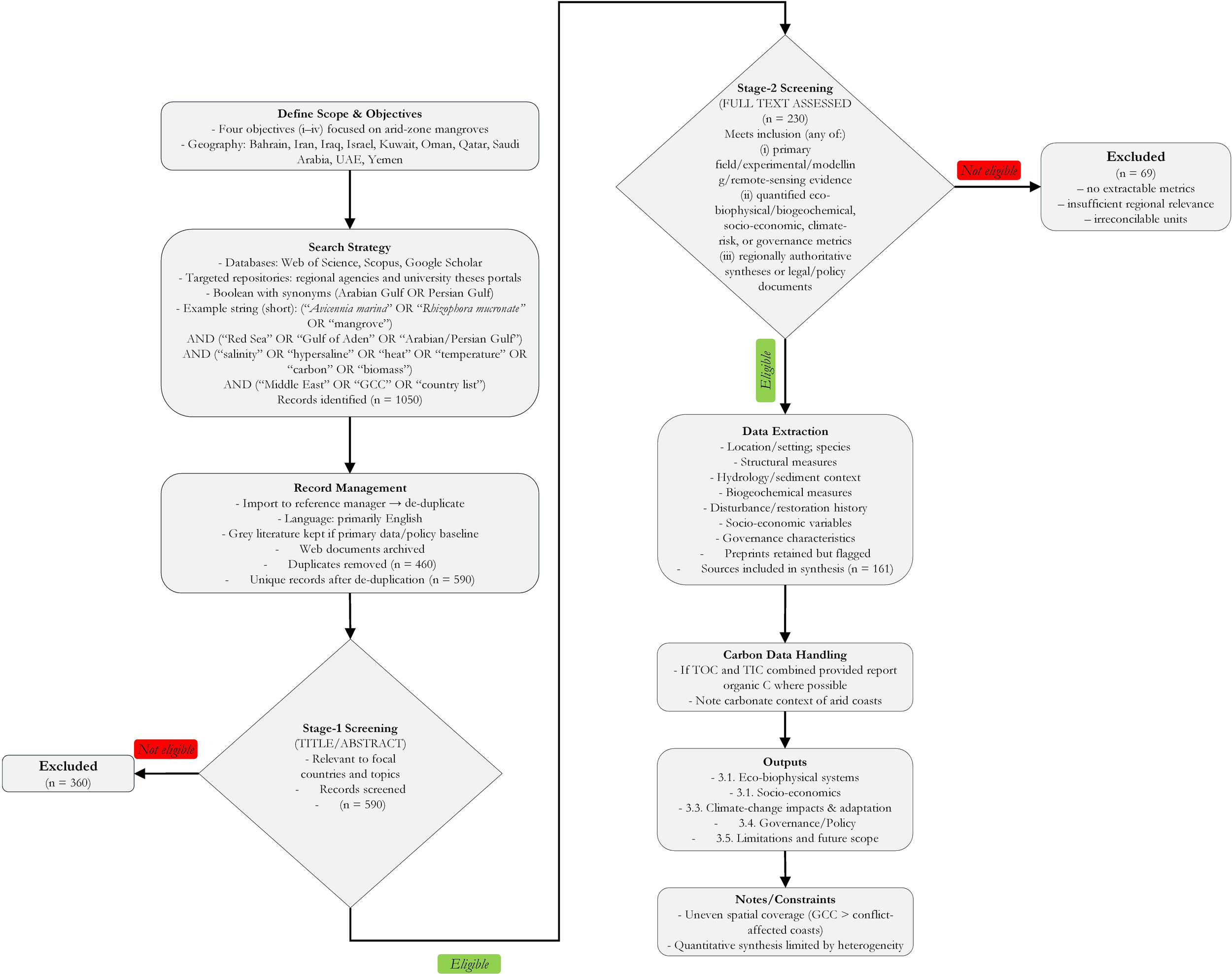

We used a multi-method evidence-based comprehensive review methodology to support four review objectives relevant to ME arid-zone mangrove systems (Taherdoost, 2022), that included (i) to compress and evaluate eco-biophysical and biogeochemical evidence on heat-salinity stress; (ii) to test what remains and does not transfer between the global mangrove paradigm and arid coasts; (iii) to plot a region-specific adaptation, restoration, and monitoring agenda in step with national climate commitments; and (iv) to reconcile socio-economic and equity dimensions with high performance of governance. We targeted the geography of Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Yemen. The results are presented in five sections of the paper: (3.1) eco-biophysical systems, (3.2) socio-economics, (3.3) climate change impacts and adaptation, (3.4) governance/policy, and (3.5) limitations and future scope. Figure 1 shows the ME countries where this review was conducted. Figure 2 shows the overall methodology used in this study.

Figure 1

Study region across the Middle East with national boundaries shown as blue outlines. Red polygons depict mangrove distribution from the Global Mangrove Watch (GMW) 2016 v2 dataset; polygon outlines are intentionally exaggerated for legibility and are not to scale. The upper-right inset situates the study area in the global context. Graticule coordinates are standard geographic (WGS84). Basemap credits: Esri and partners; administrative boundaries: Natural Earth.

Figure 2

Methodology flowchart used in this comprehensive review.

Iterative searches were conducted in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, complemented by targeted queries of regional agency repositories and university theses portals, with no restriction on search date. We applied no publication‐year restrictions to avoid excluding foundational arid-zone studies and evolving grey literature (policies, agency reports). Boolean strings combined taxonomy, locality, and process terms, with regional synonyms (e.g., “Arabian Gulf” OR “Persian Gulf”). For example, (“Avicennia marina” OR “Rhizophora mucronata” OR mangrove) AND (“Red Sea” OR “Gulf of Aden” OR “Arabian Gulf” OR “Persian Gulf”) AND (salinity OR hypersaline OR heat OR temperature OR carbon OR biomass) AND (“Middle East” OR “Gulf Council Cooperation” OR “GCC” OR “Bahrain” OR “Iran” OR “Iraq” OR “Israel” OR “Kuwait” OR “Oman” OR “Qatar” OR “Saudi Arabia” OR “United Arab Emirates” OR “UAE” OR “Yemen”). Near-duplicate items were consolidated for counts.

Grey literature has explicitly been incorporated where it forms primary data and policy baselines. We restricted the corpus to English to a large extent. A reference manager was used to eliminate duplicate files; web documents were placed in storage. This two-stage screening retained records that either: (i) documented primary field, experimental, modelling, or remote-sensing evidence pertinent to our focal countries; (ii) quantified biophysical or biogeochemical parameters, socio-economic outcomes, measures of climatic risks, or governance instruments; or (iii) contained regionally authoritative syntheses or legal/policy documents. Articles that were not relevant to the topic in a significant way, which had no methods identified, and which were beyond the area of geographical scope were avoided. Preprints that have transparent methods with obvious regional relevance were not discarded but marked, as part of the appraisal process. We sampled location and setting, species, structural measures, hydrology/sediment context, biogeochemical measures, history of disturbance, restoration success, socio-economic variables, and governance characteristics, and only those records were sampled that were eligible. Where organic and inorganic fractions of carbon were combined, we presented organic carbon alone where it was possible to do so and indicated the carbonate context of arid coasts. Given methodological heterogeneity across the ME studies, we conducted a structured narrative synthesis rather than a meta-analysis.

In total, about 1050 records were retrieved. After de-duplication (460), 590 unique records proceeded to title/abstract screening; 360 were excluded as out of scope for focal countries, which were basically not about mangroves, and or lacking identifiable methods, leaving 230 for full-text assessment. A further 69 full texts were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria, which were no extractable eco-biophysical/biogeochemical or governance metrics, insufficient regional relevance, or irreconcilable reporting units, that finally resulted in 161 sources included in the synthesis, which included 145 scholarly articles and 16 web/agency/portal items cited as numbered footnotes. Coverage was skewed toward GCC states with comparatively fewer studies from conflict-affected coasts; this asymmetry is noted in the limitations.

Legal protection, management instruments, restoration/offset commitments, and multi-level/transboundary mechanisms were some of the policy documents. Spatial coverage of the evidence is uneven between countries and sub-basins, with more concentrated coverage in GCC states. Quantitative synthesis was restricted by the heterogeneity of methods and reporting units. In the region, sources of a policy are new or developing, and enforcement decisions are still partly a matter of judgment. We thus laid greater stress on decision-relevant ranges, empirically restricted thresholds, and transparently identified uncertainties as compared to sole value generalizations. Here, we also note that despite comprehensive, multi-database searches with documented criteria, dynamic indexing and grey-literature volatility mean that inadvertent omissions may occur, and the number of searchable publications may vary over time.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Eco-biophysical mangrove systems in the Middle East

Mangrove ecosystems in the ME are unique outposts of tropical biodiversity in an otherwise arid region. Understanding their eco-biophysical dynamics is crucial because these mangroves provide valuable services, such as coastal protection, carbon sequestration, and nursery habitat, which are under extreme environmental stress. ME mangrove forests, found in Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Yemen, occur at the harsh limits of mangrove tolerance, characterized by high salinity, high temperatures, and minimal freshwater input (Friis and Killilea, 2024). Consequently, they are often stunted dwarf forests with patchy distributions and low standing biomass (Waleed et al., 2025). Nonetheless, they represent important natural capital in the region’s coastal zones and form natural laboratories for studying mangrove adaptations to extreme conditions. In the context of climate change and regional coastal development, there is growing interest in mangroves as nature-based solutions for carbon storage and shoreline stabilization (Ahmed et al., 2022). In this section, we highlight the key findings from peer-reviewed studies and technical reports and identify knowledge gaps and future research needs.

3.1.1 Species distribution and biogeography

It is estimated that the total Gulf mangrove area is ~165 km² (Almahasheer, 2018). Approximately half of this occurs in the UAE, especially in Abu Dhabi, which alone now supports about 55–60 km², and about 40% in Iran, mainly in Hormozgan Province. Qatar supports ~ 10 km² of mangroves, chiefly at Al Khor and Al Dhakhira in the northeast. Bahrain’s mangroves are the smallest by country, covering only ~0.6 km² in Tubli Bay in Ras Sanad, a relictual population at the extreme environmental limit. Saudi Arabia retains ~10 km² of fragmented stands, primarily around Tarut Bay, while Kuwait and Iraq still have no self-sustaining native mangrove populations. Earlier afforestation attempts in Kuwait during the 1960s–70s failed, but post-1990 plantings in protected embayments such as Sulaibikhat Bay have survived, with A. marina reaching ~2.5 m height after seven years (AboEl-Nil, 2001). Iraq historically lacked mangroves, though a small pilot planting in the Shatt al-Arab delta began in the 2020s1. Throughout the Gulf, A. marina typically grows as isolated, low thickets or dwarf trees lining muddy lagoons and estuaries, reflecting the region’s extreme heat and hypersalinity.

Mangroves in the Red Sea–Gulf of Aden have reached their most significant ME development. A. marina dominates the Saudi and Yemeni coasts, forming extensive forests of about 200 km², forests along the Saudi Red Sea shores (Almahasheer, 2018; Shaltout et al., 2021), whereas R. mucronata appears only in well-flushed southern lagoons of Yemen and Djibouti and sparsely on the Farasan Islands (PERSGA/GEF, 2004; Alharbi, 2019). Yemen’s Tihama plain and Adenic lagoons also hold sizeable, although poorly quantified, stands (USAID, 2013). Poleward limits persist as relictual A. marina patches at Sinai and a tiny spring-fed colony near Eilat (28° 10N) (Por et al., 1977), highlighting the hydrographic controls on distribution.

South of Hormuz, Indian Ocean mangroves persist as scattered A. marina enclaves nourished by runoff and summer monsoons. On Iran’s Baluchestan coast, A. marina lines estuaries such as Govatr Bay, with R. mucronata recorded only at Sirik (Zahed et al., 2010). The only extensive forest is the 823.60 km² Hara Biosphere Reserve on Qeshm Island (Zahed et al., 2010). Oman contains approximately 11 km² split among Batinah, Muscat, the central Arabian Sea, and monsoon-fed Dhofar khawrs (Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), 2004). All stands occupy low-energy bays and estuaries that receive periodic freshwater input.

Only two true mangrove tree species are found in the Middle East: the grey mangrove A. marina, dominant throughout the region, and the red mangrove R. mucronata, restricted to a few locales (Waleed et al., 2025). A. marina has an extensive but discontinuous distribution along the Middle Eastern coasts, which reflects its high tolerance for the region’s hyper-saline and hot environments (Haseeba et al., 2025a). In contrast, R. mucronata reached its northern limits here and survived only in more sheltered or southern sites with slightly moderated conditions (Ahmed and Abdel-Hamid, 2007). Overall, mangrove cover in this region is modest, at approximately 0.19% of the global mangrove area (Bunting et al., 2022). However, spatial patterns vary among sub-regions due to differences in climate and coastal geomorphology.

Several environmental factors govern the biogeography of mangroves in the Middle East. The foremost of these is freshwater availability. Studies have consistently shown that proximity to freshwater inputs, such as river outflows, groundwater springs, or rainfall, has a strong influence on mangrove presence and growth in this desert region. For instance, in Qatar and the UAE, mangroves thrive best at inlets receiving intermittent wadi flow or subsurface fresh groundwater, whereas purely marine locations with no freshwater tend to have sparser, more stunted mangroves or none at all (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 2008; Friis and Killilea, 2024). Al-Khayat and Balakrishnan (2014) documented that Qatar’s dense mangrove stands occur near the outfalls of ancient river systems in the northeast, highlighting the role of past freshwater delivery. Likewise, A. marina stands in Iran’s Hara-forest, gets benefit from dilution of salinity by riverine inflow from the Mehran River, thereby contributing to its relatively luxuriant condition with trees reaching approximately 5 to 6 m tall (Ghasemi et al., 2013; Karimi et al., 2025). In contrast, sites with no freshwater runoff, such as Bahrain’s Tubli Bay and some UAE lagoons, exhibit hypersaline waters that have constrained the size and coverage of mangroves in the region (Aljenaid et al., 2022; Mateos-Molina et al., 2024).

Extreme salinity and temperature are the overriding climatic constraints on mangrove biogeography. The Arabian Gulf, in particular, is a hostile setting, wherein salinities in shallow lagoons routinely exceed 45 practical salinity units (PSU) and can reach more than 70 PSU in enclosed sabkha creeks during the dry season (Rivers et al., 2020). Summer sea temperatures climb to ~35°C, while winter air temperatures in the northern Gulf can dip near freezing, a combination outside the tolerance of most mangrove species. A. marina is the only species resilient enough to tolerate these extremes, making it the sole naturally occurring mangrove in the Gulf (Haseeba et al., 2025a; Lachkar et al., 2025). Even Avicennia grows only in the warmer lower Gulf and not in the far north; 30°N is approximately the latitudinal limit, beyond which winter cold kills propagules, such as earlier attempts to naturalize A. marina in Iraq and Kuwait largely failed due to winter stress (Haseeba et al., 2025a). R. mucronata, being more thermophilic and less salt-tolerant than A. marina, is confined to the frost-free coasts of the Red Sea and the Sea of Oman, where average sea surface salinities remain moderate, typically between 36 and 40 PSU (Sofianos and Johns, 2007; Waleed et al., 2025). These environmental conditions contrast with the more hypersaline and temperature-variable settings of the Arabian Gulf, where R. mucronata is absent. Even there, Rhizophora only establishes in particularly sheltered, warm pockets, illustrating that ME conditions push this species to its ecological margin.

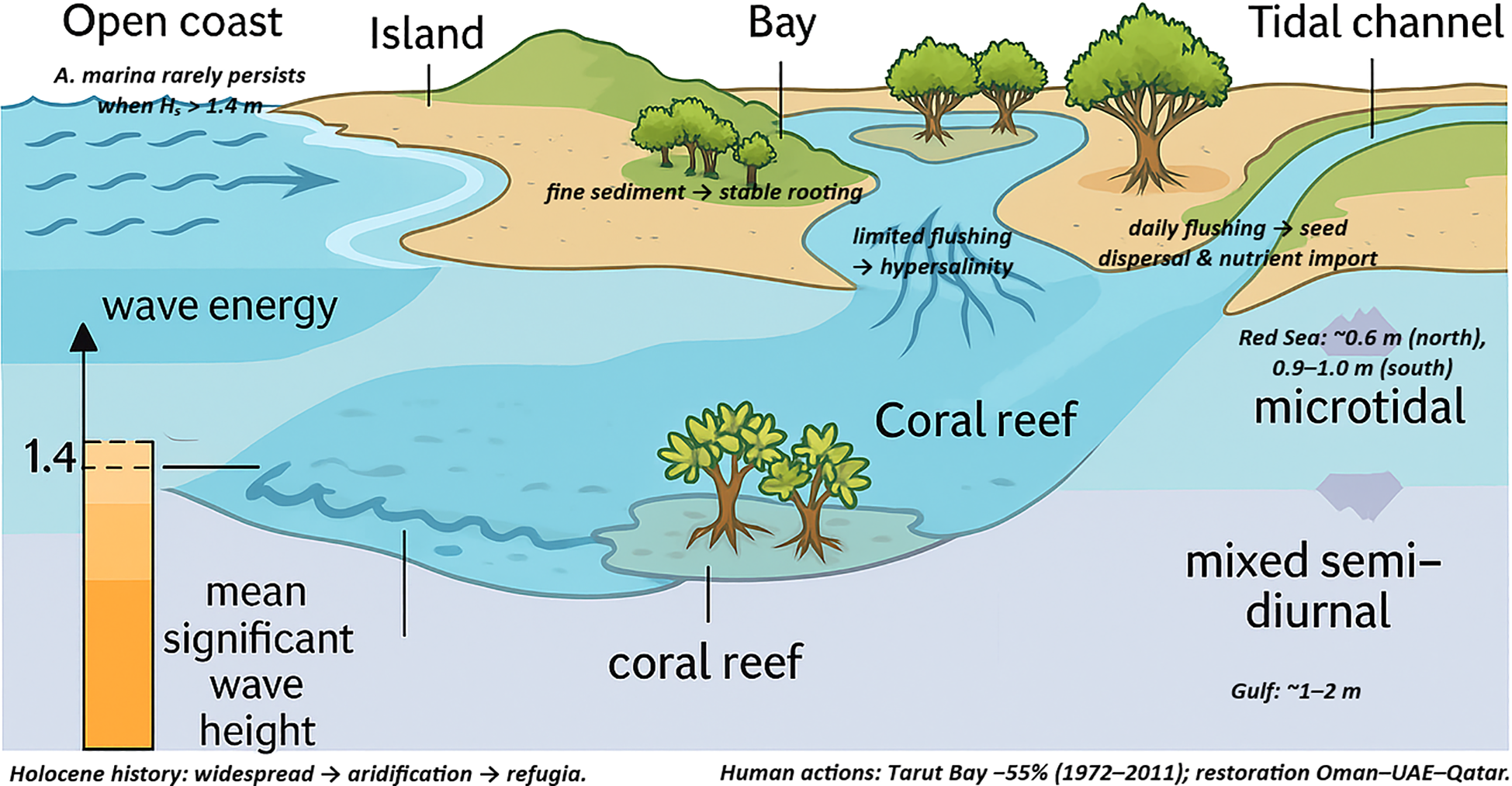

Coastal geomorphology and hydrodynamics shape mangrove distribution. Exposure to high wave action, such as open sea fronts, generally prevents mangrove growth in these areas. Indeed, Martínez-Díaz and Reef (2023) have noted that A. marina does not persist where the mean significant wave height exceeds 1.4 m. Hence, mangroves in this region preferentially colonize low-energy environments, such as the leeward sides of islands, inner reaches of bays, deltaic channels, and behind coral reef flats. Further, the ME coastline, with its many sheltered khors, such as the creeks along the Oman-UAE coast and the Red Sea mersas, provides niches where wave stress is reduced and fine sediment accumulates, providing a base for mangrove rooting. The tidal regime is micro- to meso-tidal: the Red Sea experiences a microtidal range with 0.6 m in the north, increasing to 0.9–1.0 m in the southern reaches, while the Persian Gulf features a mixed semi-diurnal tide with average tidal ranges of 1–2 m (Hoseini and Soltanpour, 2021; Guo et al., 2024). These relatively small tides indicate that tidal flushing is limited in some interior lagoons, contributing to hypersalinity. However, tidal exchange is vital for seed dispersal and nutrient import; mangroves are often found fringing tidal channels where daily flushing mitigates salt buildup. These landform–hydrodynamic controls, and the key thresholds for wave energy and tidal range, are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Conceptual controls on ME mangroves: sheltering landforms and reef flats reduce wave energy and trap fine sediment, enabling establishment; A. marina is generally absent on open coasts where Hs > 1.4 m. Small tidal ranges (Red Sea ~0.6–1.0 m; Gulf ~1–2 m) limit flushing in interior lagoons (causing hypersalinity) but daily exchange along channels disperses propagules and imports nutrients.

Historical biogeography also plays an important role. Paleoecological evidence suggests that mangroves were more widespread in the Middle East during the mid-Holocene climatic optimum, as sea levels and humidity were higher; however, many stands collapsed as conditions became more arid in the late Holocene (Rossignol-Strick, 2002; Decker et al., 2021). This history means that today’s mangrove populations are remnants of refugial sites. Genetic studies, for example, on A. marina populations, indicate low diversity and possible local adaptation to extreme conditions (Malekmohammadi et al., 2023). For example, Avicennia in the Gulf may have shorter dispersal ranges and distinct phenotypes, such as dwarfism and high salt excretion capacity, than their conspecifics elsewhere (Naidoo, 2006). These biogeographical characteristics highlight the isolation and uniqueness of each pocket of ME mangroves, meriting country-specific conservation efforts.

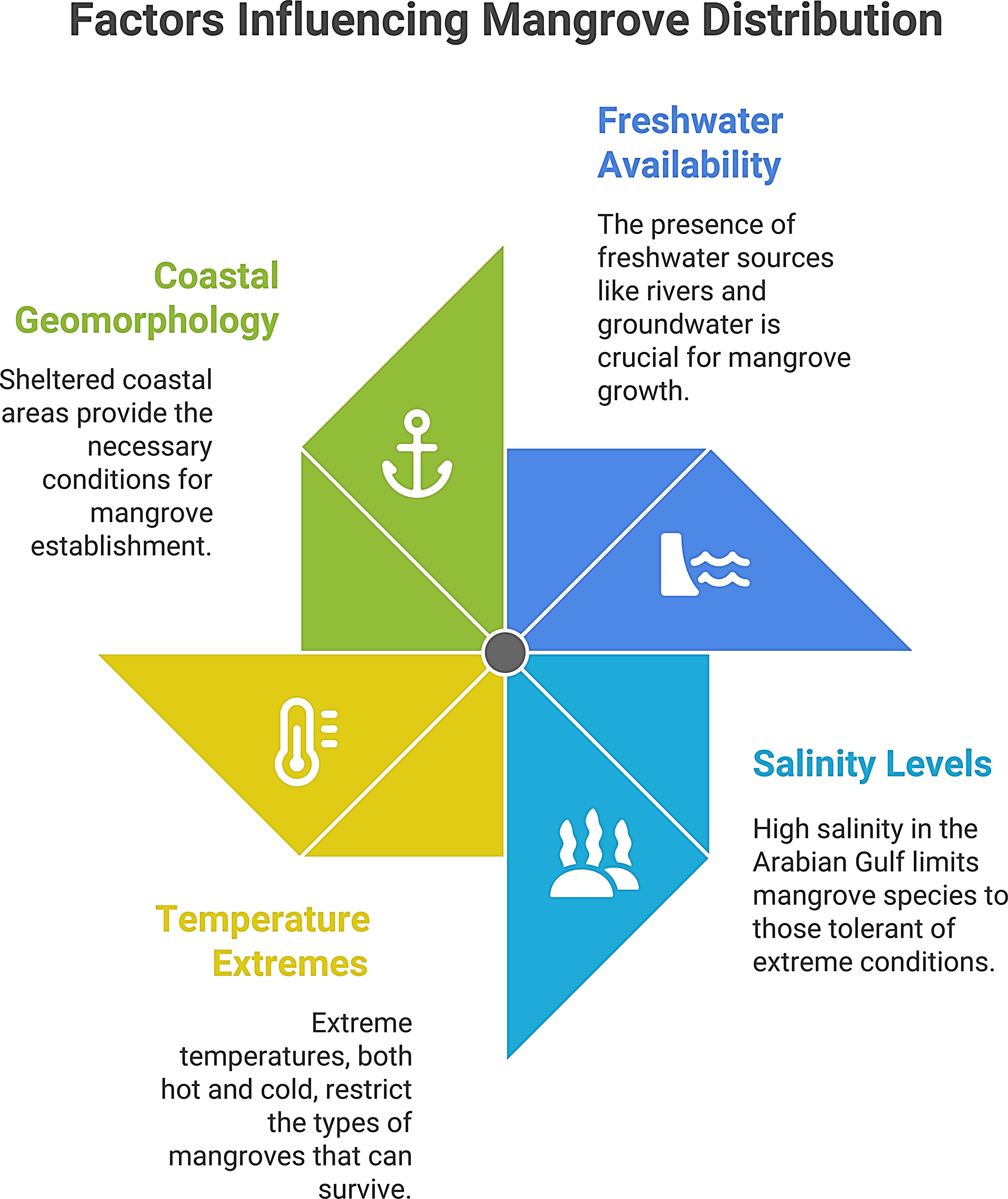

Finally, human actions have also impacted mangrove distribution, for instance, coastal land reclamation has also destroyed some stands for example, Saudi Arabia’s Gulf mangroves were reported to have declined by 55% from 1972 to 2011 due to urban-industrial development around Tarut Bay (Almahasheer et al., 2013), while restoration planting has added new stands in parts of Oman, UAE, and Qatar in recent decades. Overall, however, ME mangroves remain relatively few and far between, living on the edge of what mangrove species can withstand environmental stressors. The four dominant abiotic controls, freshwater availability, salinity, temperature extremes, and coastal geomorphology, are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Dominant abiotic controls on ME mangrove distribution and performance. Schematic highlighting (i) freshwater availability (rivers/groundwater seepage), (ii) salinity levels (hypersaline Gulf conditions), (iii) temperature extremes (summer heat and winter cold limits), and (iv) coastal geomorphology (sheltered leeward settings).

3.1.2 Structural and functional traits

ME mangroves exhibit distinctive structural and functional traits as adaptations to extreme environments. One conspicuous trait is that of dwarfism. Across the region, mangrove trees are typically short in stature, often only 2–4 m tall at maturity, in stark contrast to the 10–30 m heights recorded in more humid tropical mangroves. Surveys confirm that Gulf mangroves are especially stunted; for example, A. marina along the Gulf coast of the UAE and Qatar seldom exceeds 3 m in height, with many stands resembling that of shrublands (Al-Khayat and Balakrishnan, 2014).

Nutrient and freshwater limitations, coupled with high salinity and heat stress, are thought to constrain the vertical growth of mangroves, resulting in their dwarf forms. In the Red Sea, where conditions are slightly less harsh, A. marina can grow taller, reaching 8–10 m in the best sites, such as in parts of Sudan or near freshwater seepage zones; however, even there, the average tree height (5–6 m) is modest by global standards (PERSGA/GEF, 2004; Waleed et al., 2025). These trees also have relatively slender trunks and limited canopy spread. Field measurements in Qatar found that over half of adult A marina were only 3–5 years old, with few trees living beyond 30 years, suggesting high population turnover, and diameter at breast height (DBH) seldom exceeded 10–15 cm (Hegazy, 1998). These metrics reflect the diminutive nature of mangroves in arid regions.

Despite their small stature, productivity and growth are ongoing, albeit at a slow pace. Recent studies using tree-ring and node analyses have quantified their growth rates. Almahasheer (2021) measured branch extension in Saudi Gulf mangroves through internode counts and found that A. marina produces, on average, approximately 6–9 nodes per year, corresponding to a linear growth of approximately 20–25 cm in shoot length per year. These growth rates are notably lower than those recorded in more favorable, wetter tropical regions, where annual shoot elongation can exceed 50 cm/year, for example, Rhizophora apiculata in Thailand and A. marina in the Central Red Sea. This comparison suggests that Arabian Gulf A. marina populations are only modestly productive in terms of wood increment due to environmental stress such as hypersalinity, heat extremes, and pollution. Similarly, litterfall production, a proxy for net primary productivity, is on the lower end of the global mangrove values. Hegazy (1998) conducted a field study in Qatar, wherein A. marina litterfall was observed to be seasonal and bimodal, totaling approximately 17 tons/ha/year, with leaves comprising about 34% of the total mass. These values are relatively modest compared to some Indo-Pacific mangroves. However, these productivity levels are remarkable given the stress conditions and are sufficient to sustain detrital food webs locally. The trees compensate for slower growth by year-round activity; Avicennia in this region is evergreen and retains some leaves throughout all seasons, continuing photosynthesis whenever moisture and temperature are within tolerable ranges.

Regarding the leaf traits and water-use efficiency, ME Avicennia leaves are small, thick, and succulent, classic xeromorphic structures that store water and limit transpiration. Their midday orientation, which is <180°from the horizontal, reduces incident radiation and leaf temperature (Naskar and Palit, 2015). Salt-secreting glands expel excess ions, and field observations note that Gulf leaves glisten with crystallized salt; periodic shedding of these salt-laden leaves further relieves the ionic load. Collectively, succulence, salt glands, and sacrificial leaf drop allow A. marina to persist in waters 2–3 times seawater salinity (Waisel et al., 1986). R. mucronata, which lacks such glands and relies on root exclusion and internal tolerance (Naidoo and Naidoo, 2017), is consequently scarce under hypersaline conditions, thereby highlighting the regional dominance of Avicennia.

It is worth noting that the root architecture mirrors these extreme edaphic pressures. A. marina develops extensive shallow laterals studded with dense, stubby pneumatophores, up to approximately 10000 within 2.5 m of a single trunk (Cabahug et al., 2006). Prolonged aerial exposure due to brief tidal inundation enhances gas exchange in anoxic sediments; however, high pore-water salinity restricts nutrient uptake and seedling establishment (Ocean, 2023). Therefore, trees concentrate their roots in slightly fresher surface layers generated by rain or groundwater seepage. Where present, R. mucronata compensates with stilt roots arching 1–2 m above the substrate; studies indicate that up to 25% of its biomass resides in aerial roots, emphasizing investment in support and aeration in the Red Sea’s soft, saline muds (Sulochanan, 2013). Such architectures optimize oxygen acquisition and stability under combined anoxia and salinity stress.

Furthermore, physiological performance further confirms life at the tolerance limits. Yasseen and Abu-Al-Basal (2008) reported lower chlorophyll concentrations and photosynthetic rates than those in humid-tropical mangroves, attributing the declines to chronic salt and heat stress. They also observed that A. marina maintains high water-use efficiency by partial stomatal closure at peak stress while accumulating osmolytes, such as proline, to balance external salinity. Reproductive metrics mirror these constraints, as demonstrated by Hegazy (1998), who recorded only approximately 13% propagule maturation in Qatar, suggesting resource-driven abortion. Phenological timing appears adaptive; flowering in April–May and fruiting in June–August exploit warm, calmer seas for dispersal, whereas vegetative flushing peaks in late winter–spring and nearly ceases during the cooler, saline mid-winter. These seasonal rhythms tightly couple productivity to temperature and salinity.

With regard to structural biomass and allometry, studies reveal the cumulative outcomes of these stress-adapted strategies. In Abu Dhabi, A. marina stands exhibit relatively modest structural attributes compared to Southeast Asian mangroves. Average above-ground biomass typically ranges between 200–300 t ha-¹, with mean trunk diameters of approximately 10 cm and estimated stand ages under 50 years, which reflects their adaptation to arid conditions and environmental constraints in the Arabian Gulf region (Alsumaiti, 2014; Alsumaiti et al., 2019).

A. S. Al-Nadabi and Sulaiman (2021) observed in their study on an Omani mangrove stand, northern Arabian Sea coast, that A. marina exhibited root-to-shoot biomass ratios ranging from 1.0 to 2.1, indicating elevated below-ground allocation under arid stress (Komiyama et al., 2008). likewise reported ratios of 0.9–2.8 for A. marina, with the highest values common in Gulf/Red Sea populations. In contrast, tropical Southeast Asian mangrove systems typically display more balanced root-to-shoot ratios of approximately 1:1 (Donato et al., 2011). Such allocation maximizes water and nutrient uptake and anchors trees in shifting substrates. However, it limits woody carbon storage, confirming that survival, not growth, governs mangrove functioning at the desert sea margin.

To conclude this section, we come to the fact that the structural and functional profiles of ME mangroves are characterized by miniaturization and resilience. Diminutive, slow-growing trees with thick salt-managing leaves and extensive aerial roots perform the key functions of mangroves, such as primary production, litter turnover, and habitat provision, albeit at a reduced pace. These traits allow them to persist where few other woody plants can survive, essentially pushing the limits of the mangrove life-form. However, it also means that these populations are vulnerable; any additional stress, for example, heightened salinity or temperature from climate change, can easily reduce their growth or reproductive capacity further. Thus, understanding these functional traits is not only scientifically interesting but also critical for informing management, for example, knowing that freshwater supplementation or nutrient addition could substantially improve growth in restoration projects. Table 1 below provides key quantitative indicators of structural and functional adaptation in ME A marina.

Table 1

| Structural and functional traits | Metrics* | Why they matter | Source (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure (stature and form) |

Height: Middle East typical 2–4 m; Gulf (UAE–Qatar) seldom > 3 m; Red Sea avg 5–6 m (best 8–10 m). DBH: 10–15 cm. | Regional dwarfism; slender stems vs humid tropics (10–30 m). | (Al-Khayat and Balakrishnan, 2014; PERSGA/GEF, 2004; Waleed et al., 2025; Hegazy, 1998) |

| Growth and productivity | Shoot elongation: 6–9 nodes yr-¹ ~ 20–25 cm yr-¹. Litterfall: ~ 17 t ha-¹ yr-¹ (leaves ~ 34%). | Slow wood increment; modest but sustaining detrital NPP. | (Hegazy, 1998; Almahasheer, 2021) |

| Demography and reproduction | Age: > 50% adults 3–5 yr; few > 30 yr. Propagule maturation: ~ 13%. | High turnover; low reproductive success under stress. | (Hegazy, 1998) |

| Physiology and tolerance (leaves) | Operates at 2–3× seawater salinity (through salt glands, succulence). | Explains Avicennia dominance under hypersalinity. | (Waisel et al., 1986) |

| Roots, allocation and stocks | Pneumatophores: up to ~10,000 within 2.5 m radius. Root:shoot: 1.0–2.1 (regional range 0.9–2.8). AGB (Abu Dhabi): 200–300 t ha-¹. | Heavy below-ground investment; modest above-ground carbon. | (Cabahug et al., 2006; Al-Nadabi and Sulaiman, 2021; Komiyama et al., 2008; Alsumaiti, 2014; Alsumaiti et al., 2019) |

Key quantitative indicators of structural and functional adaptation in ME A marina.

*All values refer to A. marina unless noted.

3.1.3 Sedimentology, hydrology, and geomorphology

The eco-physical setting of ME mangroves is defined by extreme hydrological conditions and distinctive sedimentary environments. Hydrology, i.e., salinity and freshwater flux, governs the region’s mangroves, which inhabit one of the most water-stressed marine environments on the planet. Rainfall is extremely low, which is generally <100 mm/year along the Arabian Gulf shores and only slightly higher on the Red Sea coast (Barth and Khan, 2008; Al-Ansari et al., 2022). In contrast, evaporation is intense, on the order of 1.5–2 m/year in the Gulf (Barth and Khan, 2008), causing net water loss and salinity concentration in coastal embayments. As a result, the ambient water in mangrove habitats is usually hypersaline. The average sea salinity in the Gulf range is ~39–42 PSU, which is already above normal oceanic salinity (Al-Ansari et al., 2022), and enclosed mangrove creeks regularly measure far higher. In the Red Sea, salinity is also elevated, which is approximately 30–60 PSU in the central/southern Red Sea, owing to high evaporation and low influx (Mezger et al., 2016). These background conditions thus indicate that even minor hydrological fluctuations have a significant effect on mangroves. Therefore, freshwater inputs are considered as a critical modulator, as episodic rain or flood events can temporarily reduce salinity in lagoons, providing mangroves some reprieve from salt stress.

Groundwater also influences the salinity. It has been reported that limited groundwater seepage creates pockets of lower salinity around spring outlets in, for example, southern Oman, such as Dhofar, where limestone mountains provide freshwater springs that flow into coastal khawrs, resulting in brackish conditions in which Avicennia flourish at sites such as Khawr Rawri and Khawr Baleed (Hoorn and Cremaschi, 2004). A similar groundwater influence has also been reported in parts of the Red Sea coast of Yemen, where subsurface freshwater maintains mudflat moisture during droughts (PERSGA/GEF, 2004). Studies have found that mangrove stand conditions correlate with proximity to freshwater, and stands receiving measurable groundwater or runoff tend to have taller trees and denser canopies (Haseeba et al., 2025b). Conversely, mangroves in purely marine-fed lagoons often show signs of water stress characterized by leaf succulence, salt encrustation, and seasonal leaf drop.

Tidal exchange, although micro to mesotidal, remains the cornerstone of hydrological functioning in ME mangroves. Tidal ranges are typically < 1 m in the Red Sea and 1–3 m in the Gulf, giving roots only brief immersion in each cycle. Limited flooding concentrates salts through evaporation, whereas daily inundation can flush salts and replenish oxygen. Crucially, flood tides carry carbonate-rich sand and silt from neighboring reefs or shoals; Indeed, Almahasheer et al. (2017), found that Central Red Sea mangrove soils are composed mainly of minerogenic material (sand and carbonate silt), and vertical accretion rates were on the order of a few millimeters per year, comparable to global mangrove accretion rates. In contrast, Gulf forests rely on sparse carbonate, relictual terrigenous silt, and benthic algal matting, producing calcareous, low-organic substrates (Haseeba et al., 2025a). Therefore, tidal action simultaneously mitigates salinity and sustains soil building, yet its brevity accentuates edaphic stress.

ME mangroves generally root in carbonate or evaporitic sand rather than deltaic clay. In the UAE’s Khor al Beida, for instance, sand and shell fragments dominate, with organic carbon only a few percent (Samara et al., 2020). Such a high permeability accelerates drainage and drying between tides, and at the same time carbonate matrices precipitate phosphate, thereby reinforcing nutrient scarcity. Further, many forests have been found to occupy slight depressions along the Pleistocene sabkha, where pneumatophores trap particles and gradually raise the surface (Alsharhan and Kendall, 2019). However, once the elevation exceeds the tidal reach, hypersaline flats form landward, thereby limiting further expansion. This sediment–vegetation feedback confines mangroves to narrow coastal fringes that are sensitive to seaward or landward changes.

Coastal geomorphology also features sharms, khors, and mersas, sheltered inlets that serve as nurseries for mangroves along the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Oman coast. Yemen’s forests cluster at wadi mouths, such as Khor Kathib, while Oman’s extensive Mahout Island stands in a barrier-protected lagoon. Conversely, surf-dominated open coasts lack suitable depositional settings and thus host virtually no mangroves (Zerboni et al., 2020). Field experiments have shown that once mangroves disappear, whether through die-back or cutting, sediment stability collapses. Al-Hurban (2014) and Khalil (2015) have demonstrated how rapid erosion of exposed mudflats in Kuwait due to anthropogenic activities caused similar outcomes as observed in the southern Red Sea. Therefore, root networks play a decisive role in shoreline retention.

Groundwater interactions with the ocean waters, introduce a vertical salinity gradient that further structures the mangrove rooting depth. Hypersaline groundwater can infiltrate from adjacent salt flats, compelling mangroves to concentrate fine roots within the top layer, where occasional rain or tides dilute salts. Salinity profiles from Abu Dhabi have revealed that pore-water salinity rises sharply with depth (Moore et al., 2015). In contrast, Omani springs deliver subsurface freshwater that permits deeper rooting (Fouda and AI-Muharrami, 1996). It can be concluded that by partitioning the soil column, trees balance osmotic stress against water acquisition; however, their dependence on shallow layers heightens their vulnerability to surface salinity spikes.

As far as coastal processes and landform dynamics are concerned, the region is cyclone-free, mainly. However, episodic Arabian Sea storms, such as Cyclone Gonu (2007), can impose acute disturbances (Blount et al., 2008). In Oman, extreme waves uprooted trees and scoured substrata. However, post-event monitoring revealed a rapid recovery fueled by freshwater and sediment pulses (Rahdarian and Niksokhan, 2017; Najah et al., 2025). Elsewhere, sedimentary evolution is governed by slower tides, residual currents, and wind-borne dust. Water residence times are long, 2–5 years in the Gulf and decades in the Red Sea, allowing fine sediments and contaminants to gradually accumulate in mangrove creeks (Hughes and Hunter, 1979; Hunter, 1983). Over geological timescales, such steady processes, rather than episodic storms, have shaped most of the regional depositional profiles.

Overall, ME mangroves persist through a finely balanced interplay between hydrological scarcity and excess salinity. Autochthonous carbonate sands with limited nutrients compel tight internal cycling, whereas geomorphic barriers restrict upslope migration. Accretion rates of ~1–3 mm yr-¹ documented in the Red Sea have thus far tracked twentieth-century SLR (Almahasheer et al., 2017). However, accelerated rise, tectonic subsidence, and intensive coastal development increasingly threaten a coastal squeeze, especially for Gulf stands having limited sediment supply. Studies highlight critical data gaps on groundwater influence and sediment budgets on mangrove ecosystems (Macklin et al., 2021; Tomer et al., 2025), and filling these gaps will refine projections of mangrove resilience and inform better-targeted restoration. Hydrologic scarcity, elevated salinity, small tidal ranges, carbonate-dominated substrates, and long residence times define the regional setting as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| Sedimentology, hydrology and geomorphology | Metrics* | Why they matter | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrologic balance | Rainfall < 100 mm yr-¹ (Arabian Gulf shores); Red Sea “slightly higher”. Evaporation 1.5–2 m yr-¹ (Gulf). | Extreme evaporative deficit causes chronic hypersalinity risk in embayments. | (Barth and Khan, 2008; Al-Ansari et al., 2022) |

| Ambient salinity | Gulf seawater ~39–42 PSU (creeks often higher). Red Sea ~30–60 PSU (central/southern). | Background waters are already hypersaline; small freshwater pulses have outsized effects. | (Al-Ansari et al., 2022; Mezger et al., 2016) |

| Tidal regime / immersion | Red Sea < 1 m (microtidal). Gulf 1–3 m (micro–mesotidal). | Brief inundation each cycle causes limited flushing, salt concentration, and short aeration windows. | (Barth and Khan, 2008; Al-Ansari et al., 2022) |

| Sediment supply and vertical accretion | Accretion ~1–3 mm yr-¹ (Red Sea); soils largely sand + carbonate silt (minerogenic). | Capacity to (so far) track 20th-century SLR; carbonate-dominated substrates. | (Almahasheer et al., 2017) |

| Substrate composition | Organic carbon only “a few %” (Khor al Beida, UAE); sand and shell fragments dominate. | Calcareous, low-OC, high-permeability soils cause rapid drainage and nutrient limitation. | (Samara et al., 2020) |

| Water residence time | Gulf: 2–5 years; Red Sea: decades. | Long residence enhances the accumulation of fines and contaminants in mangrove creeks. | (Hughes and Hunter, 1979; Hunter, 1983) |

Eco-physical setting of ME mangroves.

*Freshwater springs (e.g., Dhofar khawrs) create localized brackish pockets that improve condition, but are site-specific and not quantified in the text; cyclone impacts are episodic (e.g., Gonu 2007) and qualitative here.

3.1.4 Biogeochemical cycling

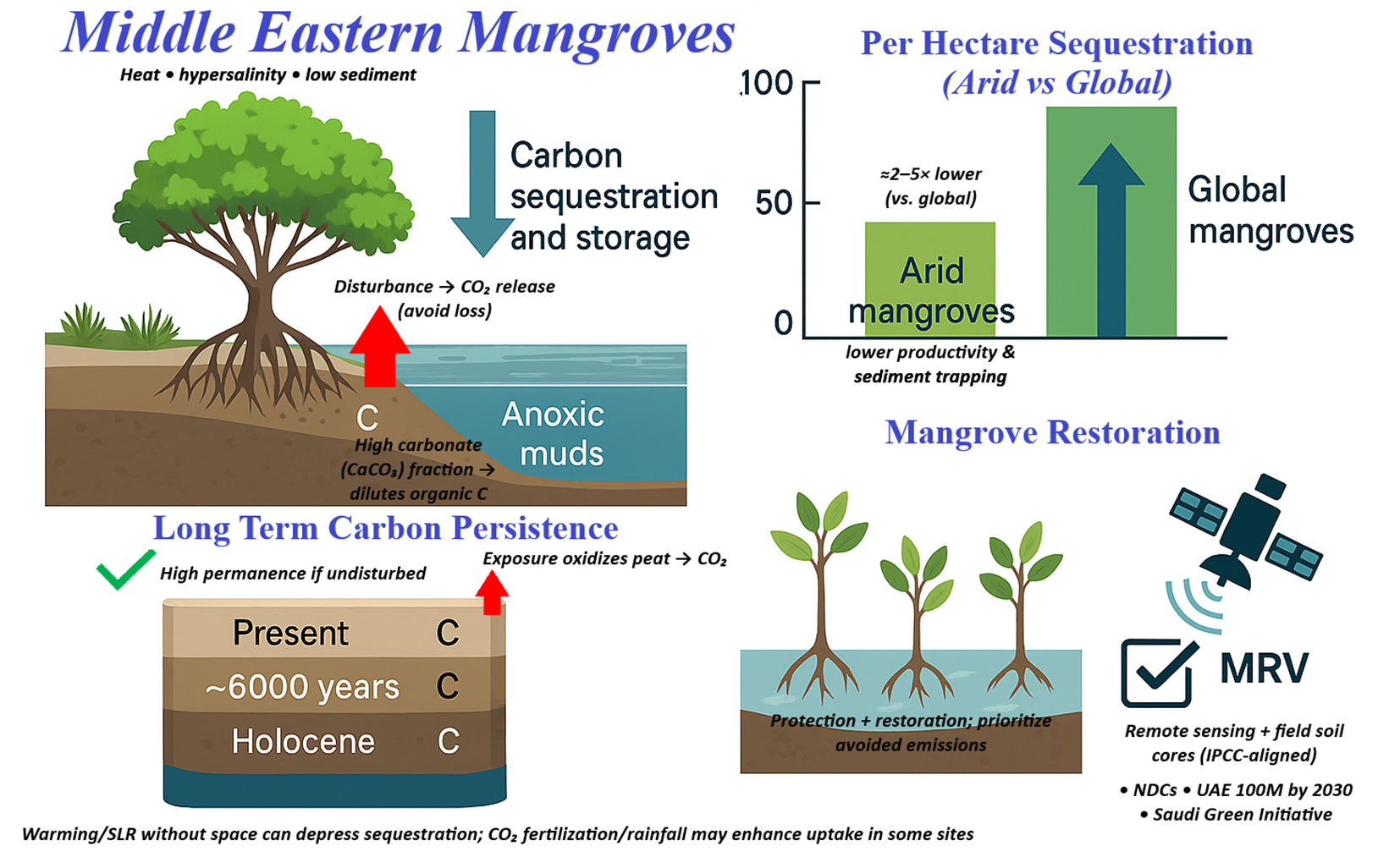

Mangrove ecosystems are renowned for their role in the biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nutrients, and metals. In the Middle East, mangroves function as blue carbon sinks and nutrient transformers, but the oligotrophic conditions of the region modulate their biogeochemical performance. Here, mangroves sequester carbon in both biomass and sediment, although generally at lower rates and quantities than wetter mangrove forests. Almahasheer et al. (2017) conducted a detailed study of Saudi Arabian Red Sea mangroves and found that soil organic carbon stocks in these arid mangroves are among the lowest reported globally. This study measured an average of only ~43 ± 5 Mg C/ha stored in the top 1 m of mangrove soil in the central Red Sea, which is roughly 25–30% of the typical values (>150 Mg/ha) recorded in Indo-Pacific mangroves.

Several factors explain this low carbon storage, such as (1) low productivity yields relatively small carbon inputs, such as leaf litter, root turnover, to the soil; (2) high temperatures and dry aerated conditions between tides can enhance decomposition, releasing much of the carbon as CO2 rather than accumulating in peat; and (3) limited allochthonous input – unlike riverine mangroves that receive external organic matter, these stands rely primarily on what they themselves produce. Correspondingly, carbon sequestration, i.e., the rate of carbon burial, in Red Sea mangrove sediments was estimated at only ~15 g C/m²/yr in recent decades, and ~3 g C/m²/yr over millennial timescales, which is an order of magnitude lower than the global mangrove average, and this low carbon sink capacity is attributed to the extreme environmental conditions of the Red Sea (Van Der Werf et al., 2009). This implies a very low nutrient supply and high evaporation limits mangrove growth and increases soil respiration rates. Essentially, any organic material that enters the soil is decomposed relatively efficiently, given warmth and periodic oxygenation, leaving little to be buried long-term.

Nevertheless, ME mangroves still play a non-trivial role in carbon cycling at the local scale. They fix CO2 through primary production and contribute detritus to the coastal food webs. The total ecosystem carbon stocks, including biomass, were modest but not negligible. For example, a multi-habitat carbon stock inventory across UAE coastal lagoons found mangroves had the highest carbon storage per hectare (~94.3 ± 19.6 t C ha-¹) among all coastal ecosystems. About 51% of this carbon is in living biomass, and the rest is in soils. Soil stocks in the top 50 cm averaged 53.9 t C ha-¹ (Carpenter et al., 2023; Dhawi, 2025). Region-wide, the total mangrove carbon pool is significant when considering large extents, such as the ~355 km² in Saudi Arabia2.

Thus, these mangroves represent vital carbon sinks in countries that otherwise have carbon-poor desert landscapes. Governments in the region have recognized this and started including mangroves in their Blue Carbon and climate mitigation strategies, such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia, which have initiatives to plant millions of mangrove trees to enhance carbon sequestration (Waleed et al., 2025). However, it must be kept in mind that environmental constraints limit per-tree or per-hectare carbon uptake. Any projections of carbon offset from ME mangroves must use region-specific low sequestration rates rather than global averages to be realistic.

Furthermore, greenhouse gas exchange in arid mangroves deviates from humid-tropical norms. High salinity and well-aerated substrates suppress methanogenesis, yielding minimal CH4 fluxes reported for the Red Sea by Breavington et al. (2025) and earlier studies. Breavington et al. (2025) demonstrated that summer heat accelerates heterotrophic respiration, driving substantial CO2 efflux, such that combined CO2 + CH4 emissions can approach burial rates. Therefore, resolving the true sink capacity depends on year-round flux data. Nutrient cycling is also constrained. With negligible river input, new nitrogen and phosphorus arrive chiefly through oligotrophic seawater or aeolian dust, which imposes chronic limitations (Anton et al., 2020). Chlorotic foliage, high C:N ratios, and slow growth reflect N scarcity, whereas A. marina recruits cyanobacterial mats (Fatimahsari et al., 2014) and diazotrophic endophytes (Inoue et al., 2024) to fix atmospheric nitrogen. Furthermore, phosphorus binds to carbonate sands, and in the case of studies conducted in the UAE, mangrove leaves contain only 0.05–0.1% phosphorus (Almahasheer et al., 2017), whereas litter decays slowly under hot, nutrient-poor conditions (Hegazy, 1998). Tight internal recycling creates limited outflow, as shown by the high 69–72 % resorption efficiencies in Red Sea stands (Almahasheer et al., 2018). Although it was shown that fertilization plots briefly boosted production, management favors safeguarding natural particulate inflows. Such conservation and opportunistic fixation sustain productivity despite the desert austerity.

Furthermore, trace metal dynamics reveal a filtering yet finite capacity. Surveys of Tarut Bay in Saudi Arabia and Tubli Bay in Bahrain recorded arsenic, chromium, copper, nickel, and vanadium much higher than international permissible limits (Almahasheer, 2019; Samara et al., 2020), surpassing the other global baselines reported for mangrove sediments (MacFarlane and Burchett, 2000). In fact, A. marina sequesters part of this load, and studies in Hormozgan, Iran, have shown that the accumulation of lead and zinc illustrates its phytoremediation potential (Ghasemi et al., 2018). However, ecological functions deteriorate once thresholds are exceeded. Protected Khor al Beida, UAE, in contrast, remains primarily within safe ranges, aside from slight Zn and Ni enrichment (Samara et al., 2020), highlighting the value of proactive pollution control.

Concerning hydrocarbon and plastic contaminants, they further add emerging pressures on mangroves. Even moderate oiling can leave persistent residues on A. marina tissues and adjacent sediments, with recovery often taking years (Burns et al., 1993). Although in the typically anaerobic mangrove sediments, mixed microbial consortia can biodegrade hydrocarbons, though attenuation is generally slow (Fakhrzadegan et al., 2019). Microplastics have recently been detected in Omani sediments and mollusks (Al-Tarshi et al., 2024), confirming mangrove creeks as depositional traps. Nevertheless, healthy stands improve neighboring habitats. In Bahrain’s Tubli Bay, they have been shown to attenuate nutrient-metal runoff, thereby benefiting seagrass beds (Saavedra-Hortua et al., 2023). Alongside organic burial, arid soils store significant inorganic carbon in biogenic carbonates (Saderne et al., 2018), which is an under-recognized pathway.

Collectively, ME mangroves operate as multifaceted biogeochemical filters, the efficiency of which is modulated by salinity, heat, and anthropogenic inputs. Restricted mainly to A. marina, they endure as scattered refugia where sheltered carbonate shores coincide with brief tidal exchanges. Dwarf canopies, salt-excreting leaves, and oxygenating roots sustain growth on sabkha soils nourished by rare freshwater pulses. Although their blue carbon, nutrient, and pollutant sinks are modest, these forests still stabilize coasts and underpin regional biodiversity. However, critical knowledge gaps cloud future projections. Hydrological minima, thermal and salinity thresholds, and long-term trends in growth, recruitment, and sediment accretion remain largely undocumented for most stands. Targeted work on local genotypes, soil microbiomes, and trophic links, especially mangrove support of oligotrophic fisheries, would clarify adaptive capacity and ecosystem connectivity. Closing these gaps is essential for robust climate forecasts.

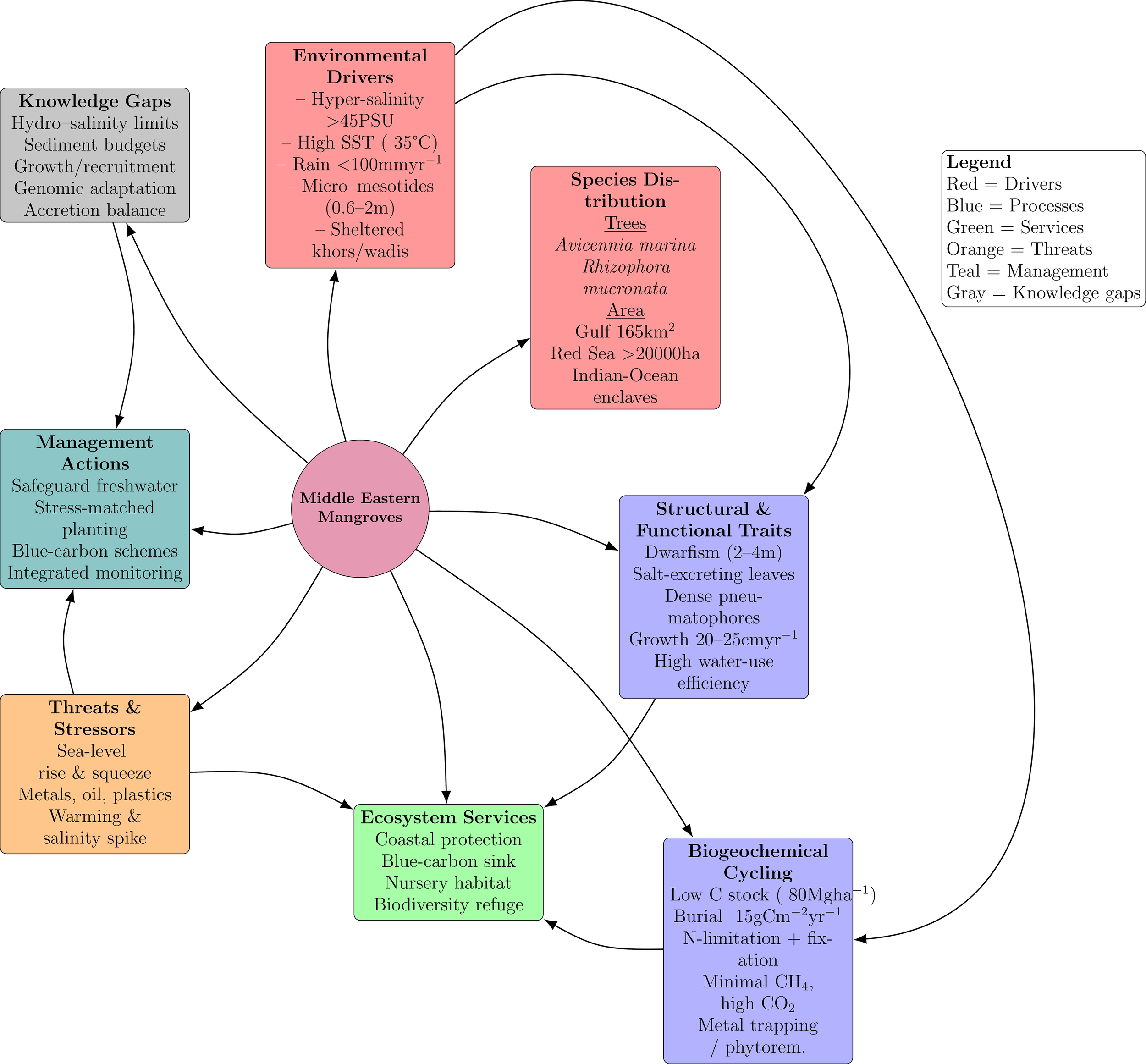

Management assessments have warned of an approaching tipping point. SLR without compensatory sediment, further warming of Gulf waters, and relentless coastal development could exceed physiological tolerances. Therefore, protecting groundwater discharge oases, curbing reclamation, and aligning restoration with site hydrogeology are priority actions. Regional planting campaigns succeed best when sites offer slight freshwater seepage and employ locally stress-hardened propagules. Hence, these modest forests deliver disproportionate benefits while illustrating life at environmental extremes. Integrated monitoring that couples hydrology, soils, and vegetation must be launched urgently. Without it, escalating climatic and anthropogenic pressures may outpace intervention. Safeguarding ME mangroves will conserve ecological heritage and provide a living model for adaptation under intensifying stress. These relationships are synthesized in Figure 5, which links drivers, traits, and biogeochemical processes to services, threats, management levers, and knowledge gaps in the literature.

Figure 5

Conceptual map of the mangrove ecobiophysical system in the Middle East. Eight color-coded modules radiate from the central Middle Eastern mangrove node. Environmental drivers (red), species distribution (red), structural and functional traits (blue), biogeochemical cycling (blue), ecosystem services (green), threats and stressors (orange), management actions (teal), and knowledge gaps (grey). Curved radial arrows denote direct influences on the mangrove system, while secondary curved arrows trace the dominant causal pathways among modules, for example, hyper-salinity regulates physiological traits, which in turn modulate service provision. Box positions convey thematic relationships rather than geography. The diagram synthesizes peer-reviewed evidence to show how extreme salinity, heat, and limited freshwater create dwarf, Avicennia-dominated stands with low carbon stocks, and it pinpoints priority interventions, maintaining freshwater inputs, applying stress-matched restoration, and instituting integrated monitoring, to safeguard these desert-edge forests under rising sea levels and expanding coastal development.

3.2 Socio-economic dimensions of ME mangroves

Although the Middle East’s mangrove ecosystems are limited in extent compared to tropical regions, they provide critical socio-economic benefits in an arid context. These salt-tolerant A. marina stands are the only evergreen forests in these regions that act as natural buffers and resource repositories along desert coasts. Regional mangroves span from substantial forests in Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea and Gulf shores to small patches in Bahrain. Some countries, such as Iraq and Israel, have negligible mangrove cover. Understanding their socio-economic aspect is vital because rapid coastal development, climate stress, and resource pressure threaten these fragile ecosystems. Recent research has begun to highlight how ME mangroves support fisheries, protect shorelines, store blue carbon, and enrich local culture and livelihoods. We organized the discussion into three domains, i.e., provisioning and regulating services, cultural and recreational values, and livelihood and equity analyses, and shed light on why socioeconomic insights into ME mangroves are important for conservation and sustainable development.

3.2.1 Provisioning and regulating services

ME mangroves underpin coastal fisheries by functioning as nurseries for commercially valuable juveniles. In Qatar, they shelter blue swimming crabs and myriad fish. Al-Khayat and Jones (1999) and Al-Maslamani et al. (2012) reported dense juvenile assemblages along the nation’s east coast. Restoration in Oman restored more productive fishing grounds, with molluscs, crabs, and fish crowding replanted creeks3. Even modest stands host remarkable diversity, with 177 fish species catalogued in an Omani mangrove lagoon (Al Jufaili et al., 2021). Although studies have found limited evidence that mangroves subsidise offshore fisheries, these forests sustain prey and ecosystem engineers that are critical for higher trophic levels (Al-Khayat and Giraldes, 2020), thereby reinforcing regional food security.

Coastal defense services are equally consequential. PERSGA/GEF (2004) has documented that Red Sea mangroves stabilize sediments, curb erosion, and arrest dune migration, the benefits judged far more valuable than wood harvest. In Oman, decades of planting have created the lungs of Muscat, a living barrier that filters water and absorbs cyclonic surges (Al-Afifi, 2018). Such extensive Arabian Gulf plantations are expected to enhance protection from rising seas and extreme tides (Erftemeijer et al., 2020). Thus, even dwarf stands will act as natural breakwaters, safeguarding rapidly urbanizing shorelines.

Blue carbon sequestration adds climate mitigation value. Despite physiological stress, Gulf mangroves rank among the largest carbon sinks, regionally (SChile et al., 2017). Bahrain’s remnant forests store approximately 200 Mg C ha-¹ (Naser, 2023), and natural UAE stands reach ~156 Mg C ha-¹ (SChile et al., 2017). Although Oman’s stocks are lower (around 60–133 Mg C ha-¹), these densities approach humid-tropical benchmarks (Al-Nadabi and Sulaiman, 2018). Recognizing this asset, Bahrain aims to quadruple its mangrove area by 2035 to meet net-zero pledges (Naser, 2023), while Saudi Arabia and the UAE have embedded restoration within their Vision 2030/2050 strategies4. Although carbon monetization is still nascent, the inclusion of mangroves in national greenhouse-gas inventories signals rising economic valuation.

Traditional provisioning persists, where alternatives lag. On Iran’s Qeshm Island, mangrove branches supply forage, fuel, and boat timber, and blossoms sustain apiculture. Similar subsistence use is observed in Yemeni and Iranian villages, but unregulated cutting and grazing have accelerated the decline (Zahed et al., 2010). Wartime fuel shortages have intensified wood harvesting in Yemen5. However, global synthesis shows that indirect benefits, such as fisheries enhancement, shoreline stability, and carbon storage, vastly outweigh the market value of wood or fodder (Su et al., 2021). Therefore, balancing subsistence use with conservation is pivotal for retaining the full socio-economic portfolio of ME mangroves.

3.2.2 Cultural and recreational services

Even in desert societies, mangrove ecosystems have notable cultural significance and recreational value. Al-Afifi et al. (2024) demonstrated that Omani coastal residents highly value mangrove services, even associating them with Arabic and Islamic stewardship. In their study, they showed that the respondents emphasized the intrinsic, instrumental, and relational values of mangroves are embodied in their vernacular term, called al qurm. Historical practices where livestock rest beneath mangrove canopies or even use its bark as traditional medicine are very common examples. In Qatar, school children and university volunteers now plant mangroves as green oases along a barren coast6. These patterns confirm that mangroves anchor the regional identity and heritage.

Eco-tourism has translated this cultural attachment into economic value. The UAE’s Eastern Mangrove Lagoon, threaded with boardwalks and kayaking routes, provides urban green space and birdwatching opportunities for the region. Emirates Nature–WWF has placed a high monetary value on such amenities, highlighting ecotourism as a pillar of the UAE’s blue-economy vision7. Further, UN Environment (2018) has called the Qurm Ramsar reserve Muscat’s green lung, where charismatic fauna heighten the aesthetic experience8. Carefully managed access thus integrates conservation and livelihood benefits in these areas.

Soheili village on Qeshm Island exemplifies community-led models. Adjacent to the UNESCO-listed Hara forest, residents have created dolphin-watching tours, homestays, and mangrove-themed handicrafts that immerse tourists in local folklore. Women operate more than 30 craft shops and many guesthouses, preserving cultural skills while diversifying income9. Therefore, the valorization of the ecosystem has reinforced social cohesion and pride in Persian Gulf coastal culture.

Beyond formal tourism, newly planted stands in Bahrain and Kuwait serve as outdoor classrooms and family picnic spots, illustrating the everyday value of amenities. Education programs employ nurseries and reserves to instill conservation ethics, cultural services with long-term societal returns. Qualitative surveys in Oman, visitor counts in UAE parks, and community narratives in Iran converge on a single takeaway. Although spatially limited, ME mangroves wield a disproportionate influence as symbols of resilience, loci of recreation and eco-spiritual connection, and catalysts for heritage-based development in rapidly modernizing nations (Moussa et al., 2024).

3.2.3 Livelihood and equity analyses

Socioeconomic dependence on mangroves varies markedly across the Middle East. In wealthy Gulf states, mangroves underpin public goods, fisheries recruitment, and coastal protection, without direct household extraction. In contrast, coastal communities in Yemen, Oman, and remote Iranian and Saudi districts still harvest fuelwood and fodder, especially where conflict or poverty constrain the alternatives. Yemen’s sixth national biodiversity report notes that the war−related fuel crisis has again accelerated the use of fuel−wood for cooking, intensifying mangrove cutting (Republic of Yemen, Ministry of Water and Environment, Environment Protection Authority, 2019). Because most Yemeni and Djiboutian stands remain government land with de-facto open access, villagers gain short-term relief, but it risks long-term degradation. Therefore, policies that replace biomass energy or institute regulated community forestry are essential to reconcile subsistence needs with conservation.

Where co-management has been adopted, the livelihood outcomes differ sharply. On Qeshm Island, the village of Soheili has transformed the UNESCO-listed Hara forest into a community-run ecotourism hub. Residents operate boat tours, homestays, and handicraft enterprises through their councils, achieving full employment and gender-balanced participation. Women now lead more than 30 craft shops and guide visitors, overturning the historic male monopoly on mangrove labor. This empowerment shows that involving local actors, especially women and youth, can align equity with ecosystem stewardship.

In high-income settings, restoration initiatives are essentially state- or corporation-driven. Qatar’s coastal planting projects and Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 campaigns deliver climate mitigation and urban amenities. However, their chief beneficiaries are distant publics rather than traditional users10. Yap and Al-Mutairi (2025), in their regional governance review, highlighted fragmented authority and limited community inclusion, calling for participatory approaches. Oman’s JICA-supported programs now engage villagers in monitoring and replanting, cultivating shared ownership (Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), 2004). Thus, channeling investment toward subsistence fishers and herders is pivotal for distributive justice.

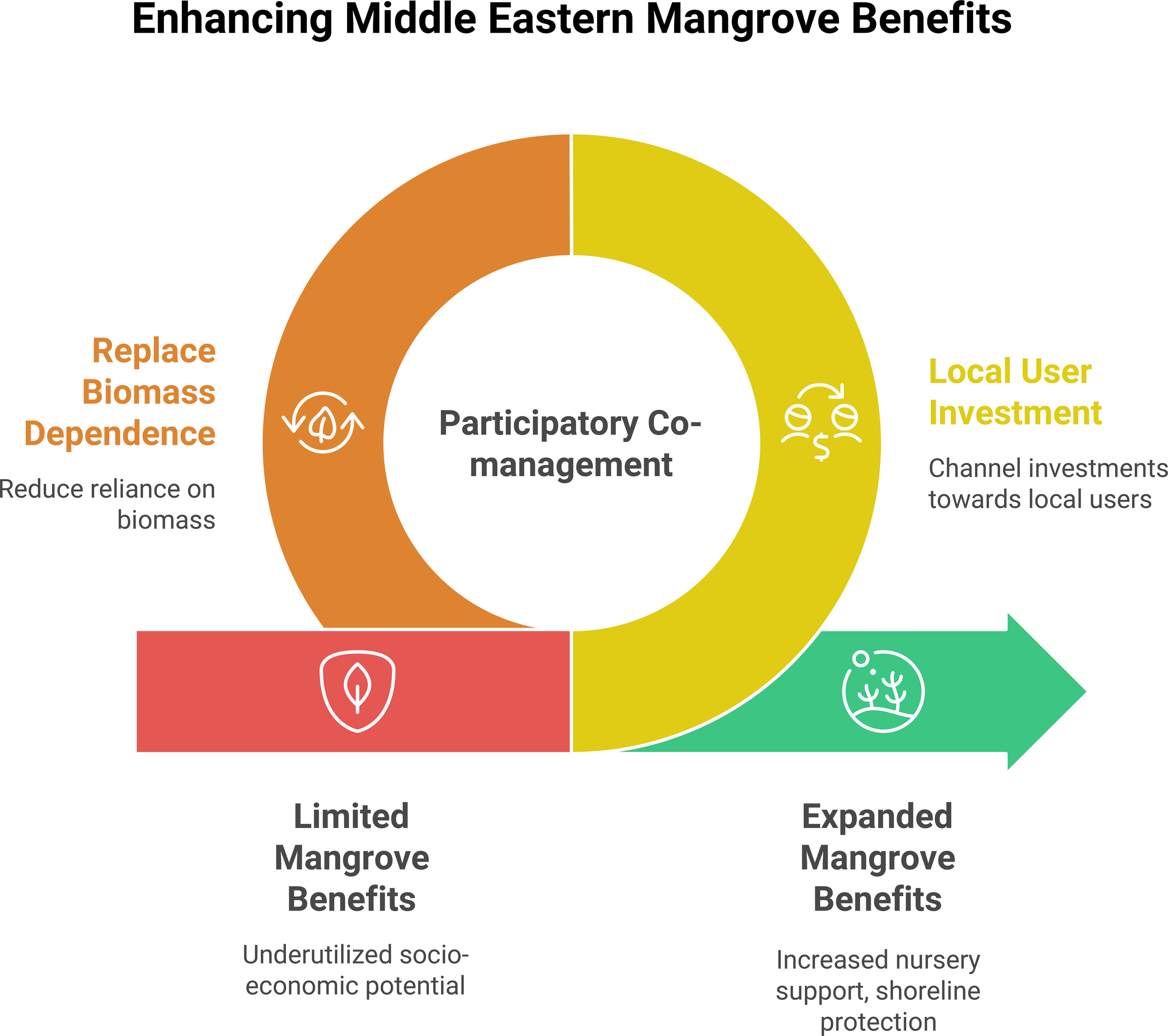

Despite these advances, socioeconomic inquiry remains limited. Yap and Al-Mutairi (2025) also found that only 21 of the 168 Western−Asian mangrove studies examined livelihoods or economic valuation. Systematic data on gender roles, benefit distribution, and the efficacy of restoration for well-being are largely absent, constraining evidence-based policymaking. Figure 6 summarizes a simple theory-of-change for the region demonstrating participatory co-management at the core, enabled by (i) replacing biomass dependence and (ii) channeling investment to local users, shifting systems from limited to expanded mangrove benefits. This implies that as the governance moves from top-down projects toward co-management and targeted support for local users, benefits expand, such as nursery support, shoreline protection, and cultural amenities.

Figure 6

Enhancing ME mangrove benefits, policy pathway schematic. Central ring: participatory co-management. Left lever: replace biomass dependence (alternatives to fuelwood; regulated community forestry). Right lever: local user investment (directing funds and decision-making to fishers, herders, and community groups). The pathway arrow depicts a transition from limited benefits (underutilized socio-economic potential) to expanded benefits (increased nursery support, shoreline protection, and cultural–livelihood gains).

Collectively, the literature reveals that even modest ME mangrove tracts furnish essential livelihoods, risk reduction, and cultural identity, and where inclusive governance is embraced, these benefits expand while pressure on resources declines. Filling the current research gaps and embedding local voices in management will therefore be pivotal in securing both ecological integrity and equitable development along the region’s rapidly changing coasts. Key socio-economic metrics and policy anchors are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3

| Socio-Economic metrics | Metrics (values/claims) | Why they matter | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provisioning / Nursery | Dense juvenile fish and blue swimming crabs in Qatar (east coast); dense juvenile assemblages along the east coast | Direct nursery function supporting local fisheries | (Al-Khayat and Jones, 1999; Al-Maslamani et al., 2012) |

| Restoration in Oman causes more productive fishing in replanted creeks | Restoration converts habitat to near-term livelihood gains | Footnote 3 | |

| 177 fish species recorded in an Omani mangrove lagoon | High biodiversity in modest stands; prey base for higher trophic levels | (Al Jufaili et al., 2021) | |

| Coastal defense | Stabilize sediments, curb erosion, arrest dune migration; dwarf stands act as natural breakwaters; buffer cyclonic surges (Oman) | Shoreline risk reduction for urbanizing coasts | (PERSGA/GEF, 2004; Al-Afifi, 2018; Erftemeijer et al., 2020) |

| Blue carbon and climate policy | Bahrain ~200 Mg C ha-¹; UAE ~156 Mg C ha-¹; Oman ~60–133 Mg C ha-¹ | Significant carbon stocks despite aridity | (SChile et al., 2017; Naser, 2023; Al-Nadabi and Sulaiman, 2018) |

| Bahrain: 4× mangrove area by 2035 | National mitigation commitment tied to mangroves | (Naser, 2023) | |

| Included in national greenhouse gas (GHG) inventories | Formal recognition causes rising economic valuation | Footnote 4 | |

| Restoration embedded in Vision 2030/2050 (KSA/UAE) | Long-horizon policy backing for expansion | Footnote 4 | |

| Cultural and recreation | Stewardship values (Al Qurm); boardwalks/kayaking/birding (UAE); Muscat’s green lung; school and volunteer planting | Cultural identity and urban amenity benefits | (Al-Afifi et al., 2024); Footnote 6 |

| Livelihood and equity | Fuelwood/fodder where alternatives are limited (Yemen, parts of Iran/Oman); Soheili, Qeshm: community ecotourism; >30 women-led craft shops | Equity, women’s participation, and diversified local income | (Republic of Yemen, Ministry of Water and Environment, Environment Protection Authority, 2019); Footnote 9 (Soheili case) |

| Evidence base/gaps | Only 21 of 168 West-Asian studies assessed livelihoods and valuation. | Sparse socio-economic evidence limits policy design | (Yap and Al-Mutairi, 2025) |

Consolidated socio-economic anchors for ME mangroves.

3.3 Climate-change impacts and adaptation in ME mangrove ecosystems

Mangrove forests in the Middle East exist at the threshold of environmental tolerance, making their resilience to climate change a critical issue. These arid-region mangroves, primarily A. marina, endure extreme heat, hypersalinity, and minimal freshwater input, yet they provide outsized ecosystem services in otherwise desert coastlines. In recent years, there has been growing interest in their fate under climate change, as nations such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia have invested in mangrove restoration for coastal protection and carbon mitigation. This section synthesizes the current knowledge on climate change impacts and adaptive responses in ME mangroves, spanning Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Yemen. Key themes covered in this section include SLR and coastal squeeze, thermal and salinity extremes, acute disturbance events, and blue carbon sequestration potential. Understanding these factors is vital for safeguarding the region’s mangroves as climate-resilient green infrastructure.

3.3.1 Sea-level rise and coastal squeeze

Relative SLR is a major climate threat to mangroves globally, especially in the low-lying arid coasts of the Middle East. Tide-gauge records indicate that the Arabian Gulf has experienced, on average, 2.92 mm/year of SLR in recent decades (Al-Subhi and Abdulla, 2021), a rate exceeding the global 20th-century average of 1.7 mm/year (Church and White, 2011). Regional modelling projects that Gulf sea levels could rise 39.1 cm by 2100 under the high-emissions RCP8.5 scenario, outpacing typical vertical accretion rates in local mangroves (Al-Subhi and Abdulla, 2021). Sediment cores and surface elevation surveys suggest that Persian/Arabian Gulf mangroves have low sediment supply and accumulation rates, often <3 mm/year, reflecting the region’s paucity of riverine input.

In Saudi Arabia’s coastal lagoons, for example, accretion rates of only 2–4 mm/year have been recorded, with up to half of the sediment mass contributed by carbonate deposits rather than terrigenous mud. Such slow vertical growth raises concerns that ME mangroves will be unable to keep pace with the accelerating SLR beyond the mid-century (Saderne et al., 2018). Saintilan et al. (2020) estimated that at a sustained SLR >7 mm/year, mangrove sediment accretion will lag, leading to the drowning of mangrove roots and peat collapse. Where inland migration is blocked by urban development or topographic barriers, called coastal squeeze, the outlook is particularly dire. One study has warned that up to 90% of the coastal wetland area in the Middle East could be lost by 2100 if high-end SLR scenarios unfold without room for landward shifts (Spencer et al., 2016).

Despite these threats, geological and modern evidence suggest that mangroves can survive moderate SLR if accommodation space and sediment exist. Mangroves have historically migrated landward during Holocene SLR, as evidenced by paleo-mangrove peat deposits found inland. However, in the Middle East, such opportunities are limited by steep desert hinterlands and extensive coastal development. Decker et al. (2021) observed that paleoecological records from Oman illustrate the potential and limits of mangrove resilience. During the mid-Holocene, i.e., 6000 years before present, the Omani coast supported extensive mangrove swamps, but these ecosystems abruptly collapsed within decades owing to environmental change. Interestingly, this collapse was not driven by a sea-level highstand, as sediment archives show no evidence of a significant mid-Holocene SLR peak in Oman, but rather by increasing aridity and salinity as monsoonal rainfall waned. The resulting lack of freshwater and silting up of lagoons by wind-blown sand led to hypersaline soils that mangroves cannot tolerate, causing a rapid die-off. This paleoepisode highlights that mangrove retreat can occur from climate-driven coastal desiccation as much as from coastal inundation. In the current context, the landward migration of ME mangroves is only feasible in undeveloped areas, such as some sabkha plains. Remote-sensing studies have shown that in parts of the Gulf of Oman and the southern Gulf, mangrove cover has expanded in recent decades (Rondon et al., 2023), possibly aided by conservation planting and slight SLR inundating previously barren salt flats. However, such gains are localized. Overall, without proactive planning for mangrove retreat pathways, rising seas will likely squeeze many regional mangroves against seawalls and arid uplands, resulting in net habitat loss.

3.3.2 Thermal and salinity extremes

ME mangroves endure some of the harshest temperature and salinity conditions of any mangrove biome. Summer air temperatures regularly exceed 45°C and sea surface temperatures surpass 35°C in shallow Gulf lagoons (Paparella et al., 2019), pushing A. marina near its physiological limits. Field observations have indicated that mangrove productivity peaks only up to an upper thermal threshold of approximately 38–40°C, beyond which heat stress impairs photosynthesis and growth (Ward et al., 2016). Extreme heat can induce midday stomatal closure and leaf thermal damage. For instance, Persian Gulf mangroves exist in climates with mean annual temperatures >30°C and very high solar radiation, resulting in chronic heat and evaporative stress (Naderi Beni et al., 2021). However, intriguingly, the absence of winter frosts at these latitudes has allowed A. marina to extend further north than in other regions, and studies have demonstrated that recent warming of minimum winter temperatures has facilitated mangrove range expansion into previously cooler zones (Cavanaugh et al., 2014). Thus, ME mangroves are simultaneously benefiting from milder winters while suffering from more frequent summer heat extremes as the climate warms.

Hypersalinity is another formidable stressor. Mangroves in the Arabian/Persian Gulf routinely experience pore-water salinities above 40 PSU, far above the optimal range for most mangrove species (Moore et al., 2015). In hyper-arid Qatar, soil salinities in the intertidal zone can seasonally reach 50–60 PSU because of high evaporation and negligible rainfall (Rivers et al., 2020). A. marina exhibits remarkable salt tolerance. It is facultatively halophytic, meaning it can grow in fresh water but performs best in moderately saline conditions. Recent greenhouse experiments with Gulf mangrove seedlings found that medium salinity, for example, ~50% seawater, ~17 PSU, produced the highest growth rates, whereas both freshwater and full-strength seawater stunted growth and increased leaf shedding (Moslehi et al., 2025).

In the hyper-saline Arabian Gulf, surface waters routinely exceed 39 PSU (Sheppard et al., 2010), imposing intense osmotic stress on A. marina populations. Leaf-level work from the Qatari coast shows that these trees divert a large share of photosynthate to salt-gland secretion and other osmoregulatory pathways, confirming a high metabolic cost of life at such salinities (Yasseen and Abu-Al-Basal, 2008). The growth penalty is evident in the field. Monospecific A. marina thickets in Tarut Bay and adjacent sites rarely exceed 2 m in stature, with canopy dwarfism linked to prolonged hypersalinity and associated nutrient stress (Saderne et al., 2020). Globally, the same species can reach 14 m in lower-salinity settings, such as eastern Australia, highlighting the dwarfing effect of hypersalinity (Sadeer and Mahomoodally, 2022).

Low freshwater inflow also means that nutrients are scarce, compounding stress, and nitrogen limitation is particularly acute in these oligotrophic saline soils. As salinity and heat rise beyond thresholds, mangroves face an increased risk of hydraulic failure, i.e., inability to take up water, and metabolic disruption. Episodes of mass mangrove mortality in other regions have been linked to extreme heatwaves and droughts that elevate salinity, a combination that could threaten ME mangroves during severe climatic events. The tolerance limits of Gulf mangroves are still being investigated. However, available evidence shows that prolonged pore-water salinity above approximately 60 ppt and sustained air/leaf temperatures exceeding approximately 49°C can trigger canopy die-back and reproductive failure in A. marina (Gauthey et al., 2022; Naseef et al., 2024; Dhawi, 2025). Continued research is currently quantifying these thresholds using remote sensing of canopy health and in situ physiological measurements to predict how intensifying summer heat and evaporation may tip mangroves from resilience to collapse.

3.3.3 Extreme events and disturbance regimes

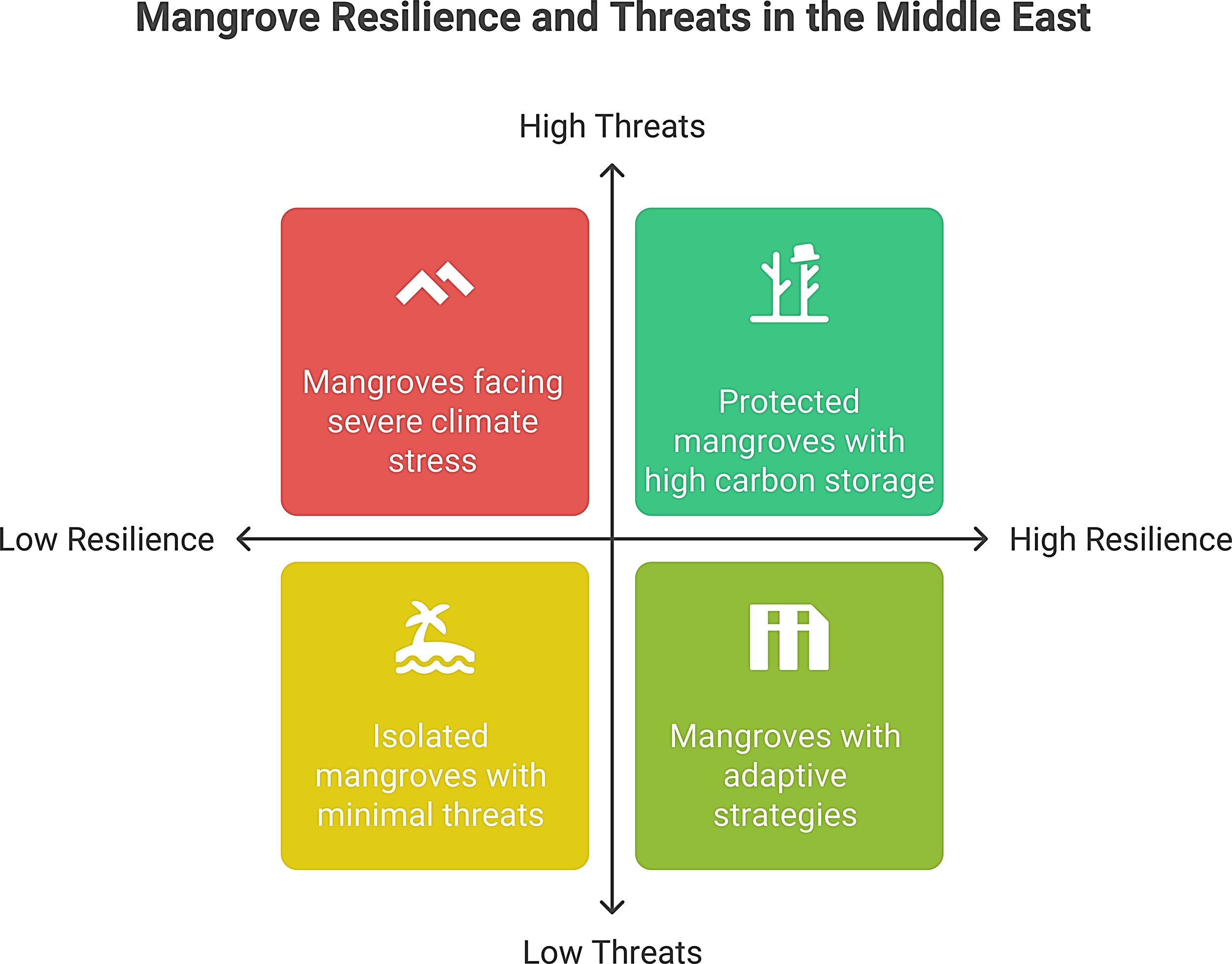

In addition to gradual climate shifts, ME mangroves are periodically affected by acute disturbances that can result in rapid degradation. Tropical cyclones, although relatively infrequent in this region, pose a significant episodic threat, especially along the Arabian Sea coasts of Oman and Yemen. Cyclones bring powerful winds, storm surges, and torrential rains that can uproot mangroves, erode sediment, and alter coastal geomorphology. In June 2007, Cyclone Gonu, the strongest cyclone on record in the Arabian Sea, struck Oman with >250 km/h winds and a 5 m storm surge (Blount et al., 2008). Mangrove stands in low-lying estuaries are inundated by saline floodwaters and buried under storm-driven sediment; post-storm assessments have noted extensive defoliation and tree mortality in affected lagoons (Banan-Dallalian et al., 2021). However, cyclonic events can have complex effects. While they can defoliate and damage trees, they also deposit new sediment that, in some cases, raises soil elevation and can help mangroves keep pace with SLR (Krauss and Osland, 2019). Following Cyclone Gonu, Omani authorities accelerated mangrove replanting programs, recognizing that storm-disturbed areas could be recolonized to serve as natural coastal buffers (Al-Afifi, 2018). More recently, Cyclone Mekunu (2018) hit the Yemen/Oman border region, causing flash floods in wadi deltas with mangroves, and field observations documented siltation around mangrove roots and increased seedling recruitment in the storm’s aftermath (Mansour, 2019). Thus, while severe storms can decimate individual mangrove stands, they may also create new sedimentary niches for mangroves to expand if post-disturbance conditions are favorable for their growth. We have demonstrated these disturbance patterns in site-level decisions using a simple resilience–threat framework, as shown in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7

Resilience–threat typology and management pathways for ME mangroves.

Dust storms and sand dune migration represent insidious disturbance regimes. In hyper-arid landscapes, such as the southern Gulf coast, high winds frequently mobilize sand and fine dust from inland deserts, which can be deposited onto mangrove zones. Large dust storms referred to as shamal events reduce sunlight and can coat mangrove leaves with dust, impairing photosynthesis in the short term. More critically, wind-blown sand can infill tidal creeks and smother pneumatophores, effectively suffocating the mangrove roots. The paleoclimate record from Oman demonstrated that increased aeolian sand deposition was a key factor in ancient mangrove collapse, as intensifying drought led to dune encroachment on coastal lagoons (Decker et al., 2021). In modern times, sand encroachment is evident in some UAE lagoons where mangroves border active dune fields. Managers have observed that without intervention, sand burial can kill fringe mangroves and prevent propagule establishment (Al-Afifi, 2018). Climate change may exacerbate the impact of dust if higher temperatures and drought frequency increase the region’s dust storm activity, further challenging mangrove survival.