Abstract

Assessing natural marine risks in coastal zones is a complex challenge due to the interplay of multiple processes. This complexity arises because a single coastal area may face simultaneous hazards of both hydro-meteorological and seismotectonic origin. The convergence of terrestrial and marine processes in the Tangier-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region, the focus of this study, can trigger catastrophic events, the severity of which is heightened in low-laying areas. To understand the threats this coastal zone faces from the Mediterranean Sea, this study assesses natural marine risks using a multi-criteria decision-making approach. The methodology employs a multi-scale Coastal Risk Index at a local level, integrating both climate change and tectonic-related risks to produce comprehensive multi-risk maps. These maps pinpoint hotspot coastal zones where natural marine risks probability is greatest. The results indicate a high risk of loss of property and a moderate risk of loss of life from both tectonic and climate-related hazards. For tsunami hazards, up to 32% of the hazardous zone is at a high risk of loss of property, but this figure is only up to 2% for loss of life. Concerning climate-related risks, 15% of the total threatened area faces a high risk of property loss, with an additional 15% at a moderate-to-high risk level. Multi-risk mapping shows that up to 30% of the hazard zone is characterized by high to very high levels of property loss risk. The city of Martil is identified as the most threatened area, a critical hotspot where the risks of tectonically-induced tsunamis and climate-induced coastal inundation intersect. Other key hotspots include the coasts of Fnideq, M’diq, Oued Laou, Stihat, and Ait Youssef Ou Ali. Importantly, the risk to human life remains low throughout the entire study area. This study also proposes some innovative solutions that could prove essential to address these risks. However, it should be noted that these solutions require long-term operational expenditures that could be a significant concern for decision-makers. Therefore, it suggests that a combination of hard engineering, nature-based solutions, and cost-effective ecological defenses, supported by public awareness and educational campaigns, could significantly improve preparedness for natural marine hazards in northern Morocco.

1 Introduction

Worldwide, coastal zones face significant threats, endangering both property and the lives of millions of people (Nadal-Caraballo et al., 2020). These areas experience dynamic natural and anthropogenic forcings, leading in rapid environmental changes (De Pippo et al., 2008). The convergence of terrestrial and marine processes in coastal regions can trigger catastrophic events, with heightened severity in populated areas. This underscores the need for coastal hazard assessment, complex task due to the interplay of multiple, sometimes unpredictable, processes (De Pippo et al., 2008; Resio et al., 2009). The diversity of hazards affecting coasts, especially natural marine threats such as tsunamis, storm surges, and sea-level rise further complicates the situation (Rutgersson et al., 2022). To better understand and address these challenges, various methods have been developed to evaluate coastal hazards, ranging from single-hazard to multi-hazard assessments (Satta et al., 2017; Gallina et al., 2020; Rutgersson et al., 2022; Agharroud et al., 2023; Luu et al., 2024). In fact, because single-hazard assessments focus on individual perils in isolation, they fail to capture the complex interplay of real-world coastal threats (Hochrainer-Stigler et al., 2023). To overcome this limitation, the authors employ a multi-hazard assessment, which integrates the analysis of several interacting hazards to produce comprehensive risk scores and identify hotspots (e.g., Gallina et al., 2020; Luu et al., 2024). The primary difficulty with this integrated approach is the added complexity of synthesizing diverse data and quantifying the relationships between different hazards.

Located in the southernmost part of the western Mediterranean, the coastal zone of Morocco faces multiple hazards of hydro-meteorological and seismotectonic origin. While numerous studies in Morocco have assessed natural marine risks, most focus on the Atlantic coasts, which has experienced severe events over the past 300 years (Kaabouben et al., 2009; Mhammdi et al., 2020; Sedrati et al., 2022; Tadibaght et al., 2022a, 2022b; Khalfaoui et al., 2023), from the devastating 1755 tsunami (Baptista et al., 1998) to powerful storms like Hercules/Christina in 2014 (e.g., Mhammdi et al., 2020). In contrast, Mediterranean coasts have received less research attention, likely because they have not experienced as many intense marine disasters (Khalfaoui et al., 2023; Hassoun et al., 2025). In fact, most vulnerability assessments focus on analyzing exposure to marine hazards, such as tsunami, sea level rise, storm surges, and other coastal threats (Niazi, 2007; Snoussi et al., 2008; Khouakhi et al., 2013; Raji et al., 2013; Taher et al., 2022; Fannassi et al., 2023). However, few studies have explored the modeling and simulation of these hazards to evaluate their probability of occurrence (Satta et al., 2016; Basquin et al., 2023; Outiskt et al., 2025). There is, therefore, a significant gap in the holistic assessment of disaster risk in all its dimensions.

Furthermore, studies have identified multiple evidences suggesting that Morocco’s Mediterranean coastal zone could face significant climate change impacts, including accelerated sea-level rise, intensified coastal storms, and enhanced erosion processes (Anfuso and Nachite, 2011; El Mrini, 2011). Satta et al. (2016); Aitali et al. (2020) and Agharroud et al. (2023) applied the Hoozeman risk equation to project future inundation levels, incorporating sea-level trends, extreme water levels, and storm wave characteristics for a 100-year return period. This methodology, although relatively simplistic, allowed not only to quantify the potential extent of inundation, but also to spatially map hazards by treating climate variables considered as dynamic forcing mechanisms within the delineated hazard zones derived from the computed inundation levels. In addition to climate-change hazards, the northern Moroccan coasts, along the seismically active Alboran Sea, are exposed to tsunamis (Estrada et al., 2018). Although not prone to tsunamis on the scale of the 1755 Lisbon event, the region’s tectonic activity, evidenced by historical tsunamis like the one in Almeria in 1522 (Reicherter and Becker-Heidmann, 2009), can generate waves up to 3 meters (Estrada et al., 2021; Outiskt et al., 2025), threatening both northern Morocco and southern Spain.

This study addresses a critical need to safeguard the populous coastal regions of Northern Morocco from marine-origin hazards. Although vulnerability analyses in hazardous zones are common, a holistic evaluation of disaster risk encompassing all its dimensions is notably lacking. Our study aims to contribute to this research area by developing a model to assess natural marine risks, specifically those arising from climate change and active tectonics. Aligned with the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) framework, we define risk through its core components: hazard, exposure, and vulnerability. The analysis further distinguishes between the risk of loss of life (gauged by the population’s reactive capacity) and the risk of loss of property (determined by the probability of environmental and physical damage). The spatial representation of the outcomes enables multi-risk assessments, pinpointing critical zones where risks converge. This, in turn, informs the discussion on implementing integrated protection measures to mitigate multi-hazard threats in priority areas.

2 Study area

2.1 Physical setting

Stretching for roughly 300 km along Morocco’s northwestern Mediterranean coast, the study area runs from Fnideq in the west to Al Hoceïma in the east (Figure 1). This coastal strip lies within the Rif chain, the northwestern tip of the Moroccan orogenic system and the westernmost extension of the Alpine belt (Chalouan and Michard, 1990). Formed through the collision of the African and Eurasian plates during the Neogene, the Rif presents a complex mosaic of nappes, thrusts, and fault systems that testify to its active geological history (Abbassi et al., 2020).

Figure 1

Location and key sources of natural marine hazards of the study area. SWH, Significant wave height; SLR, Sea level rise; TASZ, Trans-Alboran shear zone; AR, Alboran ridge; TTA, Tangier-Tetouan-Al Hoceima. Active faults are sourced from (Agharroud, 2022). Bathymetry and Elevation are from https://www.gebco.net/data-products/gridded-bathymetry-data.

The coastline is dominated by steep mountain slopes plunging almost directly into the sea, leaving little room for broad coastal plains. Between these rugged headlands, the shore opens into pocket beaches, alluvial deltas, and narrow embayments (e.g., Agharroud et al., 2023). Beneath this landscape lies a varied geological foundation: Mesozoic carbonates (limestones and dolomites), marls, and flysch sequences, interspersed with Paleozoic metamorphic rocks belonging to the External Rif and Sebtide–Ghomaride complexes (Michard et al., 2008). This lithological diversity, together with ongoing tectonic activity, shapes patterns of coastal erosion, sediment supply, and slope stability.

Due to its narrowness, the continental shelf of the study area facilitates direct land–sea exchanges. High-energy storms can rapidly transport sediments from short, high-gradient rivers, including Oued Martil, Oued Laou, and Oued Nekor (Figure 1), into the marine environment, generating distinct deltas and sediment plumes (Haissen et al., 2025).

2.2 Seismotectonic setting

This study focuses on the Northern Morocco, which lies within the Betic-Alboran-Rif (BAR) block, a geological structure bounded by the African and Iberian plates (Vernant et al., 2010; Koulali et al., 2011). The BAR block comprises three structural domains: the Betic domain in Spain, the Alboran domain in the Alboran Sea, and the Rif domain in Morocco.

The study area is exposed to natural marine hazards due to the active geodynamics of the Alboran Sea. Although the sea’s origin is complex and debated (Agharroud, 2022 and reference therein), it is a tectonically active zone with significant recorded seismicity, making it a potential source for tsunami waves (Estrada et al., 2021). One conceivable mechanism for this activity is delamination, driven by a subducting lithospheric slab beneath the BAR block alongside subduction rollback (Pérouse et al., 2010; Spakman et al., 2018; Civiero et al., 2020; Larrey et al., 2023). This process generates surface deformation where seismogenic and tsunamigenic structures are located. The most active seismogenic source in the Alboran Sea is the extensive strike-slip fault system known as the Trans-Alboran Shear Zone (TASZ) (Figure 1), situated along the eastern boundary of the BAR block (Koulali et al., 2011; d’Acremont et al., 2014). The focus of our simulation, the Averroes Fault (Figure 1), is located at in the central Alboran Sea and has been active since the Pliocene (Estrada et al., 2018). Located north of the Alboran Ridge, this fault exhibits right-lateral strike-slip motion, transitioning to a normal fault towards the northwest (Figure 1) (Estrada et al., 2021).

The Averroes Fault is both seismogenic and tsunamigenic. This is supported by its historical activity, which shows evidence of vertical displacement of up to 5.4 meters—consistent with an earthquake of magnitude 7.0. Such an event would be sufficient to generate tsunami waves impacting southern Spain and northern Morocco (Estrada et al., 2021). Furthermore, the fault may transfer its motion southeast to the Yusuf Fault (Perea et al., 2018). If the length of the active fault system increases in this way, its potential to generate larger earthquakes (Agharroud et al., 2021) and, consequently, more significant tsunamis, could be substantially heightened.

2.3 Climatic setting

The Mediterranean basin is recognized as one of the world’s most prominent climate change hotspots, where warming and drying trends are occurring at rates exceeding the global average (Namdar et al., 2021). Over the last century, mean air temperatures have increased by approximately 1.5–2.0 °C, accompanied by a decline in annual precipitation of 10–20% in several sub-regions. Projections indicate further temperature rises of up to 2.2–3.8 °C and a continued reduction in rainfall by the end of the 21st century (Alvarez et al., 2024). These changes are leading to more frequent and intense droughts, shifts in hydrological regimes, and an increase in the occurrence of extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and coastal storms.

The combined effects of these climatic trends are accelerating sea-level rise, coastal erosion, and saltwater intrusion into aquifers, while also altering sediment dynamics and the stability of coastal ecosystems. Moreover, the degradation of wetlands and loss of agricultural productivity are intensifying socio-economic vulnerabilities in coastal communities that depend heavily on natural resources (Su et al., 2025).

The study area experiences a Mediterranean climate (Köppen–Geiger Csa), with mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. Climate patterns vary noticeably over short distances due to the interplay of rugged topography, the moderating effect of the sea, and exposure to prevailing winds (Urdiales-Flores et al., 2024). The Rif Mountains create strong orographic contrasts, shaping both temperature and rainfall gradients (Al Mashoudi et al., 2025).

Average annual temperatures range from 16 °C to 19 °C, with winter lows occasionally dipping below 8 °C in higher inland areas, while summer highs in low coastal plains often surpass 30 °C. Diurnal temperature variations remain moderate near the coast but are more pronounced inland (IPCC, 2014; Deitch et al., 2017; Urdiales-Flores et al., 2024).

Rainfall is highly seasonal, with over 80% of annual totals falling between October and April. Annual precipitation varies from 500–700 mm in the sheltered eastern sector near Al Hoceïma to over 1,200 mm in the mountainous west between Fnideq and Chefchaouen. The study area is drained by several permanent and seasonal rivers (Oueds) that play a crucial role in sediment transport and coastal dynamics (Figure 1). From west to east, the Oued Smir drains the Rif Mountains north of Tetouan and discharges into the Mediterranean near M’diq, contributing fine sediments to the coastal plain. The Oued Martil, one of the largest rivers in the region, crosses the Tetouan basin and forms an important alluvial plain before reaching the sea near Martil city. Further east, the Oued Laou drains a wide mountainous watershed characterized by steep slopes and high seasonal runoff, making it a significant source of sediment and nutrients to the coastal zone. The Oued Rhis, located near Al Hoceima, has a narrow valley and a relatively short course, yet contributes to the transport of terrigenous materials into nearby bays. Finally, the Oued Nekor, one of the most important rivers in the eastern Rif, flows through the Nekor plain and discharges into the bay of Al Hoceima. It plays a key geomorphological role in supplying fine terrigenous sediments to the bay, thereby influencing its sedimentary dynamics and coastal stability (Ed-Dakiri et al., 2024). Intense, short-lived downpours most common in autumn and early winter can trigger flash floods in the short, steep coastal catchments (Satta et al., 2017).

Wind patterns reflect both large-scale circulation and local effects. Westerly to northwesterly Atlantic flows dominate in winter, while easterly to southeasterly (Chergui) winds in summer bring hot, dry conditions. Sea breezes are common along the shore during warmer months, tempering extreme heat.

Relative humidity generally exceeds 70% along the coast, especially in winter, but drops inland during the dry season. High potential evapotranspiration in summer, driven by heat, clear skies, and dry winds, intensifies soil moisture deficits. These climatic characteristics, together with steep slopes and limited lowlands, directly influence erosion, sediment transport, and hydrological processes feeding into the coastal system (Erol and Randhir, 2012).

2.4 Socio-economic background

This coastal corridor forms part of the Tangier–Tetouan–Al Hoceïma (TTA) region, one of Morocco’s most economically active areas and a crossroads of cultures. Its population is concentrated in towns and cities such as Fnideq, Martil, Tetouan, Chefchaouen (inland), Oued Laou, and Al Hoceïma, alongside numerous smaller fishing villages and rural communities. According to recent census data, the provinces of Tetouan, Chefchaouen, and Al Hoceïma together host over two million inhabitants, with the highest densities along the coast (HCP, 2024).

The socio-economic profile of the study area is shaped by a combination of tourism, trade, agriculture, fisheries, and small-scale industry. In the Tetouan area, proximity to Sebta fosters active cross-border trade and supports a dynamic tourism sector, which constitutes a major source of income. The prefecture of M’diq-Fnideq, strategically located along the Mediterranean coast, has capitalized on its maritime assets and strong touristic appeal to attract substantial investment in hospitality, real estate, and service-oriented projects.

Tourism represents a key economic driver in the study area, benefiting from the TTA region’s privileged geographical position, the diversity of its landscapes, and its proximity to Europe. The Mediterranean coastline, which extends across these localities, offers significant potential for seaside tourism, while the surrounding Rif Mountains, natural parks, and protected areas present opportunities for ecotourism. Rich historical and cultural heritage sites further support the development of cultural tourism. The juxtaposition of mountainous landscapes and coastal zones punctuated by beaches and coves makes this area a prime touristic destination.

Agriculture plays an important role, particularly in the province of Al Hoceima, which contributes 19% of the total agricultural production of the TTA region. The sector is characterized by diversified crops, mainly cereals, fruit trees, and legumes. In Tetouan and M’diq-Fnideq, agricultural activity is more constrained due to expanding urbanization and tourism-oriented land use, yet, fortunately, peri-urban and small-scale farming persist. Oued Laou, with its fertile valleys and coastal location, integrates agricultural production with fishing activities, ensuring both subsistence and market supply.

Industrial activity remains less developed compared to the regional hub of Tangier. In Al Hoceima, it is primarily oriented towards small-scale processing, particularly industries related to fishing and agri-food, with growing potential in aquaculture and seafood transformation. In Tetouan and M’diq-Fnideq, industry is closely linked to tourism and services, encompassing small manufacturing units, construction-related activities, and food processing. Oued Laou’s industrial base is minimal, dominated by artisanal and small-scale processing linked to agriculture and fishing (PAP/RAC, 2024).

3 Methodology

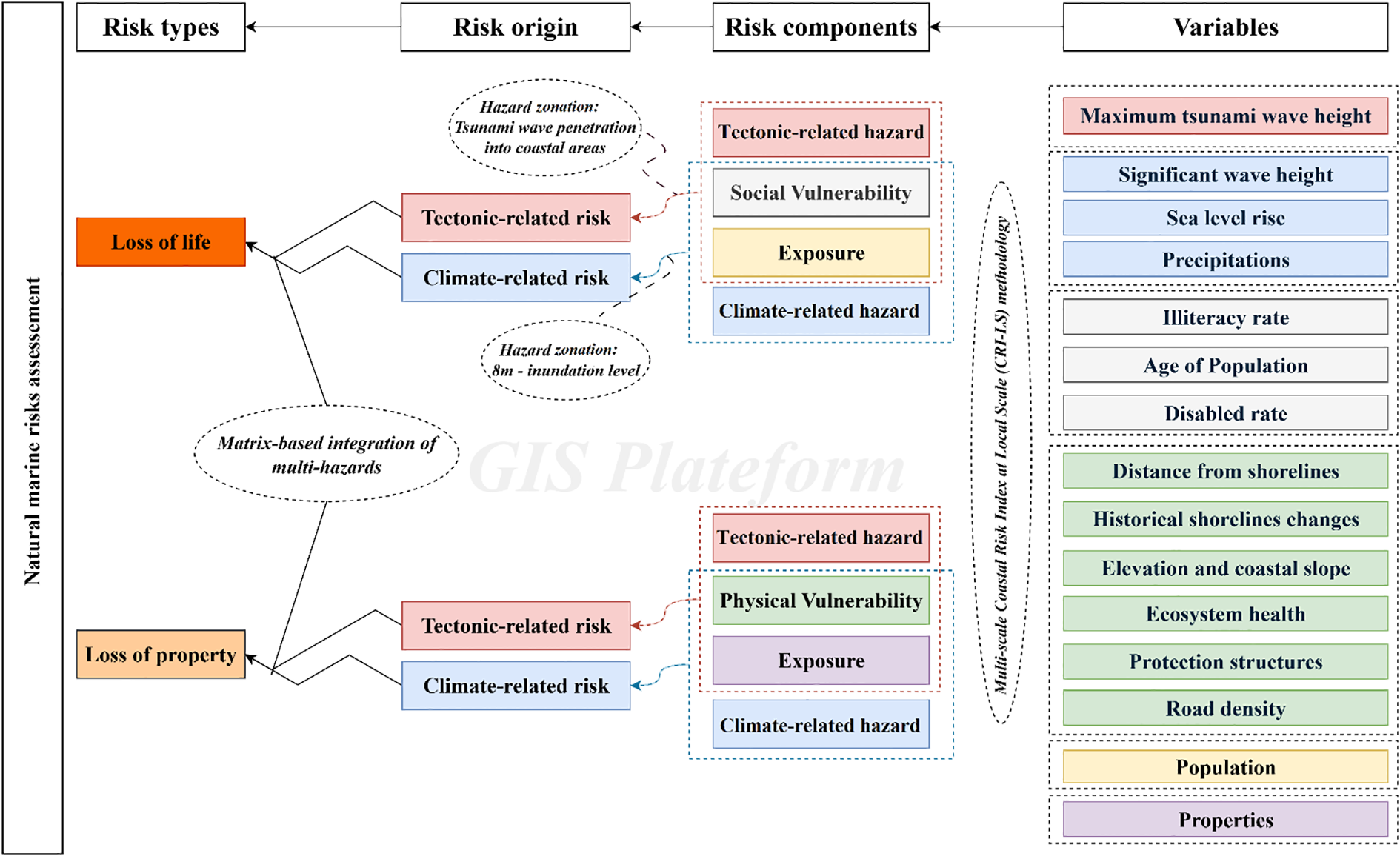

This study evaluates natural marine risks along the Mediterranean coast of Morocco through a multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approach. The methodology integrates both climate change and tectonic-related risks to produce comprehensive multi-risk maps. These maps identify high-risk coastal zones where the probability of natural marine risks is greatest, based on the known equation of risk (Equation 1):

where: R = Risk; H Hazard; V = Vulnerability; and E = Exposure.

To achieve this, the study delineates hazard zones for both tsunami risk stemming from active tectonics in the Western Mediterranean Sea and coastal inundation driven by climate-induced sea-level rise. Within these hazard-prone areas, the analysis focuses on two critical dimensions (Figure 2): (1) physical vulnerability, which analyzed through geomorphological and biological factors; (2) social vulnerability that assessed based on the population’s capacity to cope with marine disasters. To map the natural marine risk, hazards and vulnerabilities are combined using the natural risk equation (Equation 1), along with two exposure factors. The first is the population density to gauge the potential impact of marine disasters on coastal communities. The second corresponds to the land cover to assess the effects on different landscape components in the Northern Moroccan coastal zone. A flowchart summarizing the study’s methodology is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Flowchart depicting the study’s development process.

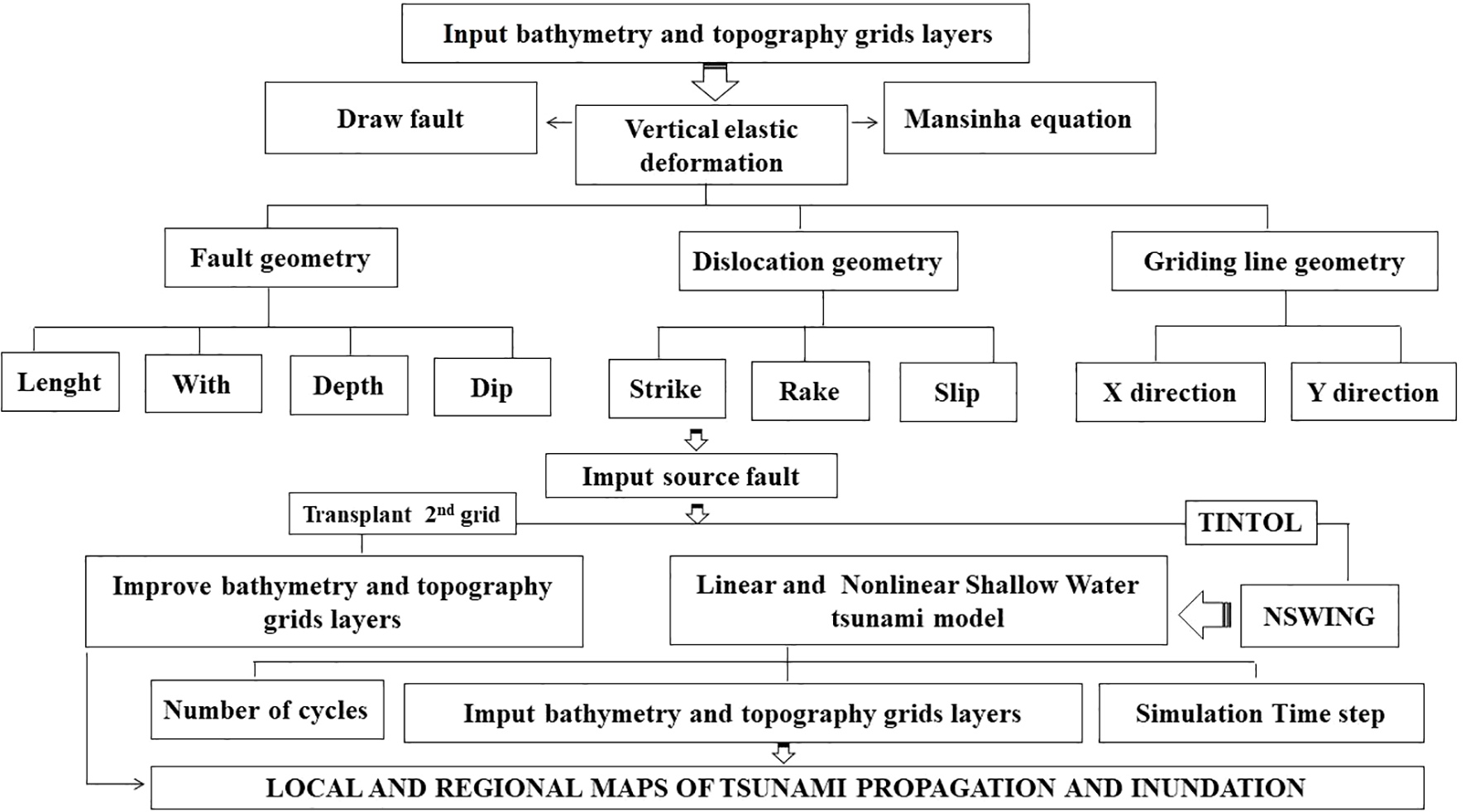

3.1 Tectonic-related hazard

Because of active tectonic movements in the Western Mediterranean Sea, the northern Moroccan coastline faces a tsunami threat from seismic faults in the region. To enhance our understanding of the impact of tsunami on the study area, numerical modeling was employed using MIRONE software as a contemporary tsunami simulation tool (Figure 3) (Luis, 2007). The software was selected due to its accessibility, ease of use, and comprehensive coverage of tsunami modeling phases, including wave generation, propagation, and coastal inundation (e.g., Tadibaght et al., 2022a; Outiskt et al., 2025). MIRONE also facilitates data integration, analysis, and enhancement without relying on external programs. Furthermore, it produces detailed, high-resolution maps that effectively visualize tsunami impacts along coastlines.

Figure 3

Numerical tsunami simulation workflow.

To streamline the process, we first downloaded bathymetric data of GEBCO (General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans) from https://www.gebco.net/data-products/gridded-bathymetry-data, accessed June 2025, at a 300 m resolution and enhanced them using the Transplant 2nd Grid tool (Luis, 2007). These maps were then imported as ASCII Grid files. Next, we delineated potential submarine earthquake faults capable of triggering tsunami waves using Mansinha’s formula (Mansinha and Smylie, 1971). For this study, a tsunami simulation was performed using the seismogenic Avoreos Fault (Supplementary Table S1). Although older than Okada’s formulation (Okada, 1985), Mansinha’s method yields reliable results and is simpler to apply (Tadibaght et al., 2022a). Additionally, it allows us to estimate a reasonable seismic magnitude by merging smaller fault segments into a single rectangular fault, whereas Okada’s approach divides them into sub-sections, limiting the magnitude achievable in MIRONE for tsunami generation. Nevertheless, Okada’s method has been preferred by other researchers using different software (Omira et al., 2009; Mellas et al., 2012)

To compute the magnitude, the following equation was employed (Equation 2):

where: D = coseismic displacement (m); A = rupture area (km²); and μ = crustal rigidity coefficient (Nm−2).

For seismic moment magnitude calculation, MIRONE implements the Mo-Mw relationship (Equation 3, Hanks and Kanamori, 1979):

where: M0 = seismic moment (Nm); and Mw = moment magnitude.

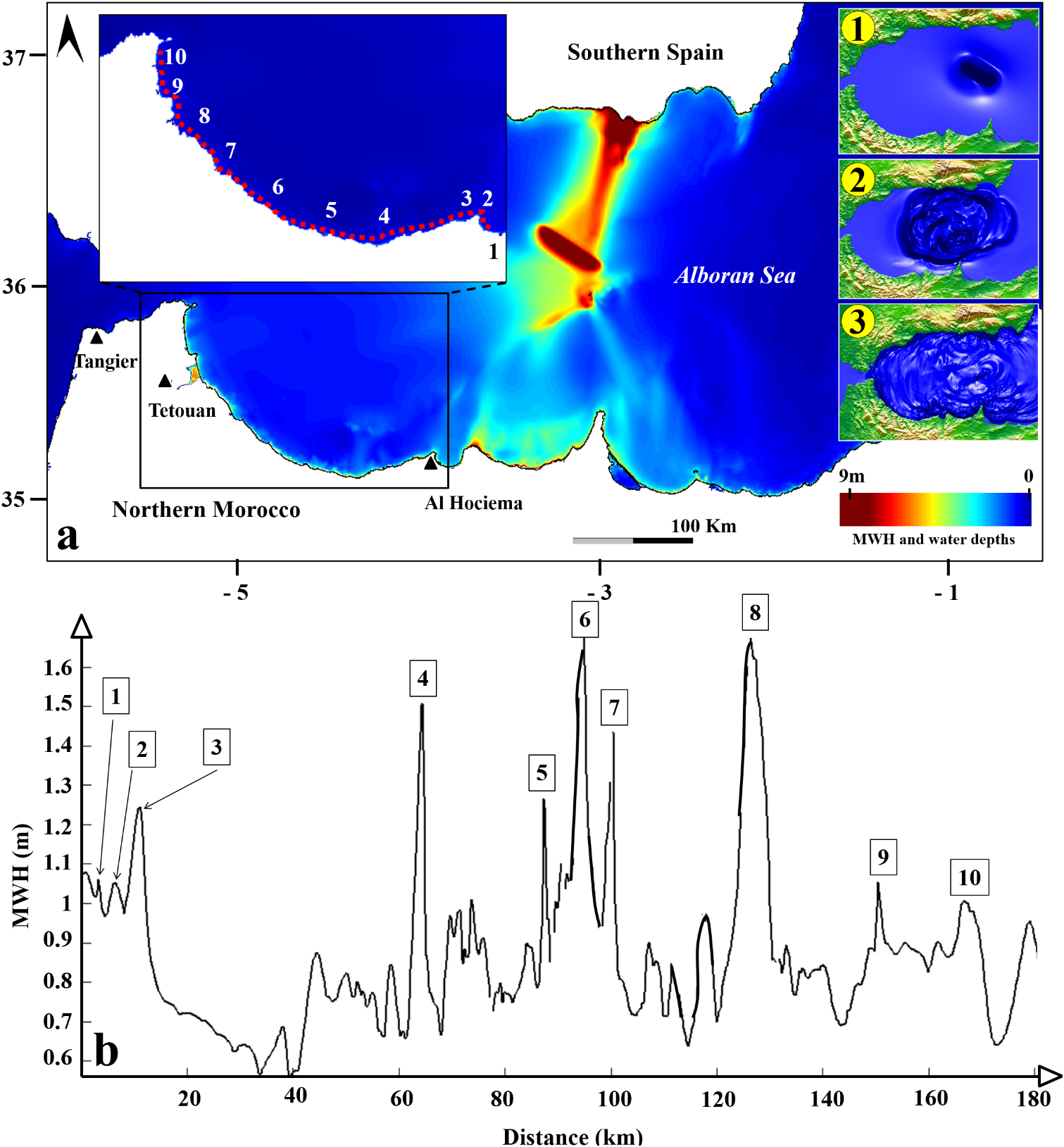

For modeling tsunami wave propagation across the Western Mediterranean Sea and subsequent coastal inundation, we employed both linear (Equation 4) and nonlinear (Equation 5) differential equation models integrated within the MIRONE software (Luis, 2007). Data quality was enhanced using the Transplant 2nd Grid tool to achieve higher-resolution results (Figure 4).

Figure 4

(a) Simulated maximum surface elevation from the Averroes Fault tsunami Scenario. 1) step of set-up; 2) step of run-up; 3) step of run-up and flow depth. (b) Tsunami arrival travel times at selected location (1, Ait Yousef Ou Ali; 2, Ajdir; 3, Al Hoceima; 4, Takmot; 5, Amtar; 6, Stihat; 7, Oued Laou; 8, Martil; 9, M’diq; 10, Fnideq.

where: η = free surface displacement (m); H = η + h = total water column depth (m); h = still-water depth (m); P and Q = the horizontal volumetric flux components along the x- and y-axes respectively (m²/s); τx and τγ = indicate the bottom friction terms in the x- and y-directions (N/m²).

3.2 Inundation hazard related to climate change

Coastal flooding related to climate change is often caused by a combination of multiple factors including tide level, storm surge, wave conditions and sea-level rise. To assess the geographical extent of the effects of such a hazard on the coastal areas concerned (the hazard zone for flooding), it is necessary to consider the maximum water level at the shoreline resulting from extreme wave conditions (100-years Return period) and extreme sea level rise scenarios. The maximum inundation level was derived applying the equation proposed by Hoozemans et al. (1993) (Equation 6).

where: Dft = Inundation level; MHW = Mean high-water level; St = Relative sea level rise; Wf = Storm wave height; Pf = Sea level rise due to atmospheric pressure drop.

This method has already been applied in Morocco to estimate inundation levels and identify hazard zones for coastal risk assessment (e.g., Snoussi et al., 2008; Satta et al., 2016; Aitali et al., 2020; Agharroud et al., 2023). Although simplistic, it allowed to identify the area in which the flooding could theoretically develop and on which the risk index had to be applied. In the Mediterranean coastal region of Morocco, where our study area is located, the highest recorded inundation level reaches 7.64 m, based on a 0.86 m sea-level rise, a 0.96 m mean high-water level, and storm waves of 6.20 m with a 100-year return period (Snoussi et al., 2008). However, future inundation levels could rise further due to the potential collapse of Antarctic marine ice sheets, which may contribute up to 1.5 m to sea-level rise (IPCC, 2014). To account for this uncertainty, many authors apply the precautionary principle by incorporating a 1.5 m sea-level rise into the Hoozeman equation when calculating inundation level (e.g., Satta et al., 2016). In this study, we compute the maximum inundation level using the same parameters as Snoussi et al. (2008), but adopt the upper projected sea-level rise for 2100, while disregarding atmospheric pressure effects (Agharroud et al., 2023). The resulting 8 m inundation level is used to delineate the climate related-risk in coastal zone. Then we assessed the coastal hazard within the delineated hazard zone for flooding. To do so, A 30-meter resolution digital elevation model, derived from ASTER DEM (NASA/METI/AIST, 2019), was used to define a coastal hazard zone, identifying all low-lying areas between 0 and 8 meters in altitude. This area is considered susceptible to future climate-related damage.

Based on a review of previous studies evaluating coastal hazard (Satta et al., 2016, 2017; Aitali et al., 2020; Agharroud et al., 2023), three key climate-related variables were selected to generate the hazard map (Supplementary Table S2): (1) Sea-level rise trends (1993–2021), derived from satellite altimetry data (https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/?id=1599); (2) Significant wave height that refer to the annual average count of waves exceeding the 95th percentile of daily wave heights over a 100-year period (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/sis-ocean-wave-indicators?tab=overview); (3) Precipitation concentration measured through the daily precipitation concentration index, which indicates rainfall erosivity and intensity, reflecting periods of highly concentrated precipitation (Salhi et al., 2019).

3.3 Coastal vulnerability

Vulnerability is a critical component of coastal risk assessment, reflecting a system’s susceptibility to natural hazards (Maanan et al., 2018). In northern Morocco’s coastal zones, vulnerability is assessed through two key dimensions (Supplementary Table S2):

-

physical vulnerability, analyzing geological, geomorphological and hydrodynamic factors that influence hazard exposure. To create a coastal vulnerability map for Northern Morocco’s coastal zones, key variables were selected based on data availability. Geomorphological factors like Coastal Slope (CS) and Elevation (E), derived from ASTER DEM (NASA/METI/AIST, 2019), indicate how topography influences shoreline retreat risk. Ecosystem health, assessed using Google Earth imagery, plays a crucial role in mitigating storm surges, flooding, and other coastal threats. Another critical factor is shoreline change, which identifies erosion-prone areas due to climate effects; this analysis builds on data from Niazi (2007); El Mrini (2011) and Khouakhi et al. (2013). Additionally, road density (from OpenStreetMap) and distance to shoreline (calculated via GIS) help determine evacuation efficiency as hazards advance inland. The presence of coastal protection structures is also considered, as they can significantly reduce the impact of marine hazards;

-

Social vulnerability, evaluating community resilience using socioeconomic indicators such as population age distribution, disability rate, and illiteracy rate. The later is derived from the latest General Population and Housing Census report (HCP, 2024). These three variables were selected because they directly influence the population’s ability to respond quickly, effectively, and with adequate awareness to hazards.

3.4 Coastal exposure

Two exposure levels are independently evaluated to determine the critical issues at stake in the study area’s coastal zone:

-

Properties, which represent tangible assets with multiple uses, playing a significant role in the region’s economy and long-term development. To incorporate this factor into the risk assessment, land cover data is used, sourced from ESRI’s Sentinel-2 Land Cover dataset. This dataset is produced using Impact Observatory’s deep learning model, which analyzes Sentinel-2 satellite imagery (available at: https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/landcoverexplorer/);

-

Population, as coastal communities face increased susceptibility to hazards impacting these regions. The population’s exposure level is assessed using demographic density data sourced from the latest General Population and Housing Census (HCP, 2024).

3.5 Coastal marine-related risk assessment

Four risk maps were generated (Table 1): risk of loss of property from long-term climate change impacts, risk of loss of life from long-term climate change impacts, risk of loss of property from tectonic events (specifically tsunamis), and risk of loss of life from tectonic events (specifically tsunamis).

Table 1

| Risk | Risk type | Hazard | Vulnerability | Exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal inundation related to climate change | Loss of property | Coastal inundation | Physical vulnerability | Landcover |

| Loss of life | Coastal inundation | Social vulnerability | Population | |

| Tsunami | Loss of property | Maximum wave height | Physical vulnerability | Landcover |

| Loss of life | Maximum wave height | Social vulnerability | Population |

Key components used to generate each risk map in this study.

For the tsunami risk assessment, hazard zones were delineated based on the maximum inland penetration predicted by numerical tsunami simulations. Meanwhile, coastal inundation risks were determined using the Hoozemans equation.

The development of each risk map follows multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) principles, adopting the multi-scale Coastal Risk Index at Local Scale (CRI-LS) methodology established by Satta (2014) (Equation 7). This integrated approach was designed to offer Mediterranean coastal managers an accessible tool for assessing coastal risks. It is cost-effective, adaptable, and suitable for local-scale applications, making it practical for managers with limited resources and data availability. This approach systematically integrates the three fundamental components of the natural risk equation (Equation 1) through:

where: CH = Coastal Hazard sub-index; CV = Coastal Vulnerability sub-index; and CE = Coastal Exposure sub-index.

Initial data collection provides the foundation for selected risk variables, which are then processed through a standardized evaluation framework. Each variable class is assigned a relative importance score on a 1–5 scale, with rankings determined through literature review. Subsequently, percentage-based weighting factors are applied to these variables (Torresan et al., 2012), derived from expert opinions and literature review followed by stakeholder consultation (Satta et al., 2016; Agharroud et al., 2023). These weighted scores are then computationally integrated to generate composite sub-indices following the Equation 8.

where: CSI = Coastal sub-index (CH, CV or CE); n = Number of variables; xi = scores related to variable i; Wi = weight related to variable i.

Both scores and weights were normalized to a standard 0–1 scale to enable comparative analysis of the results. Considering = 1 instead of 100% and , the equation becomes:

where: = minimum score; = maximum score; = normalized score.

4 Results

4.1 Tectonic-related coastal risk

4.1.1 Tsunami threat from the Averroes fault

The simulated tsunami scenario generated by the Averroes fault in the Alboran Sea shows a significant impact on several Moroccan coastal areas. Tsunami waves could reach the Moroccan coasts in under 30 minutes. Wave propagation from the source indicates that tsunami energy is concentrated on the eastern part of Morocco’s Mediterranean coast, particularly in areas closest to the epicenter. Within this region, the Bay of Al Hoceima is the most affected, with maximum wave amplitudes reaching approximately 3 m (Figure 4). Results show significant inundation in this area, with flow depths exceeding 2 m inland (Figure 4). This basin-shaped topography acts as a natural amplifier, accentuating the tsunami’s impact. Moving westward, the tsunami reached Jebha with wave heights of approximately 1.6 m (Figure 4). Despite this moderate offshore amplitude, observed onshore flow depths were less significant. The steep slopes and rugged coastal relief in this region limited the extent of inland flooding. A similar phenomenon was observed in Oued Laou, located further east. There, flow depths exceeded 2 m, particularly in the flat, low-lying areas downstream of the coastal river. The confluence of the river mouth and the tsunami inundation underscores the heightened vulnerability of such estuarine environments.

In the city of Martil, flow depths exceeded 6 m in several locations (Figure 4). This urban center, situated on a coastal plain with dense development along the waterfront, is particularly at risk. The area’s low-lying topography exacerbated wave penetration inland. At Marina Smir, between M’diq and Fnideq, flood depths reached approximately 2 m, with localized areas of more limited inundation. This site, which contains port and tourist infrastructure, is also exposed, especially in the low-lying areas around the port where the coastal morphology facilitates penetration. Fnideq city, to the northwest, may also experience severe flooding, with water depths exceeding 2 meters in exposed areas. The region’s topography, characterized by coastal exposure and a predominantly flat terrain, contributes to its exposition, particularly in its coastal districts

4.1.2 Tectonic-related coastal risk index

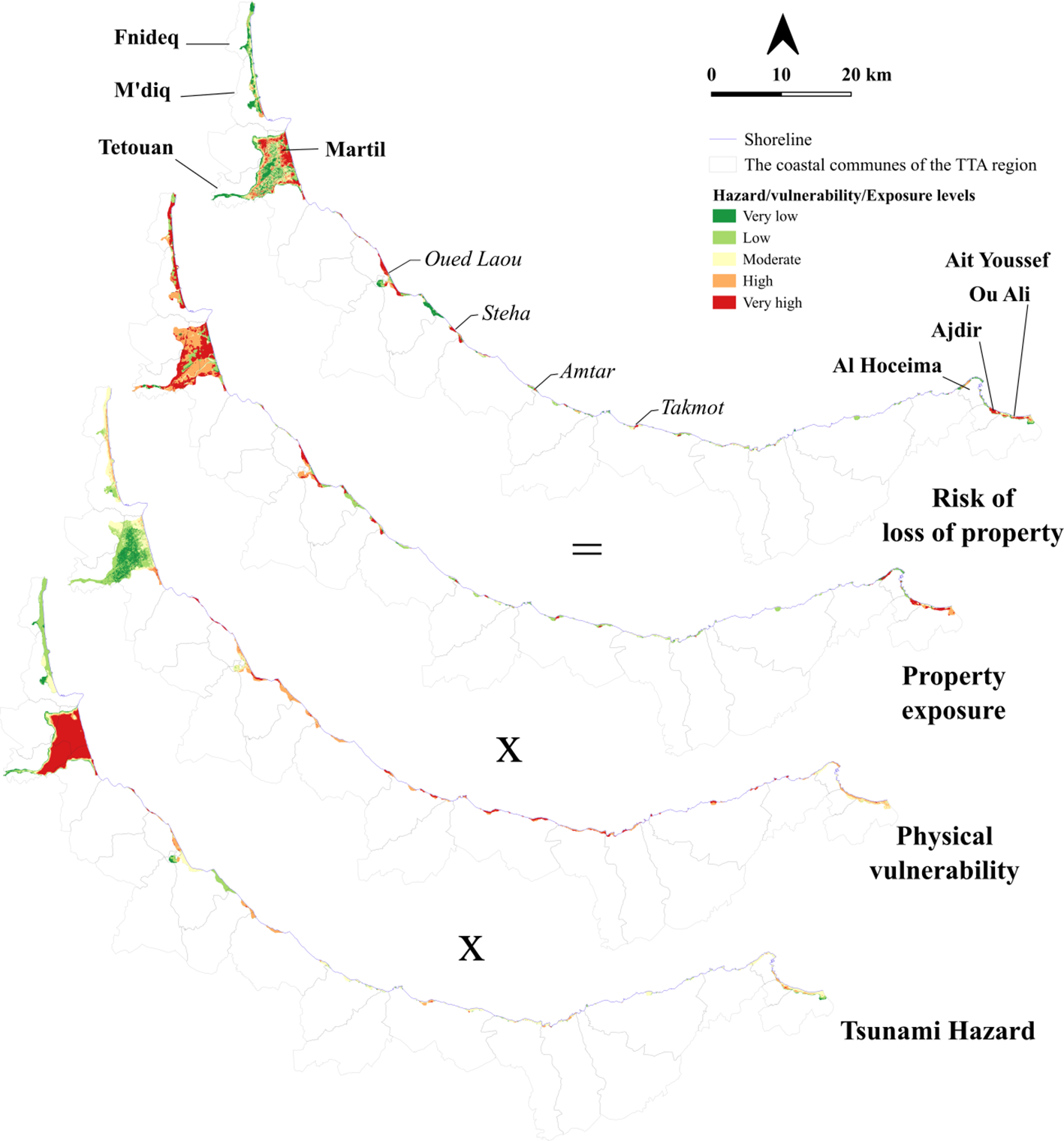

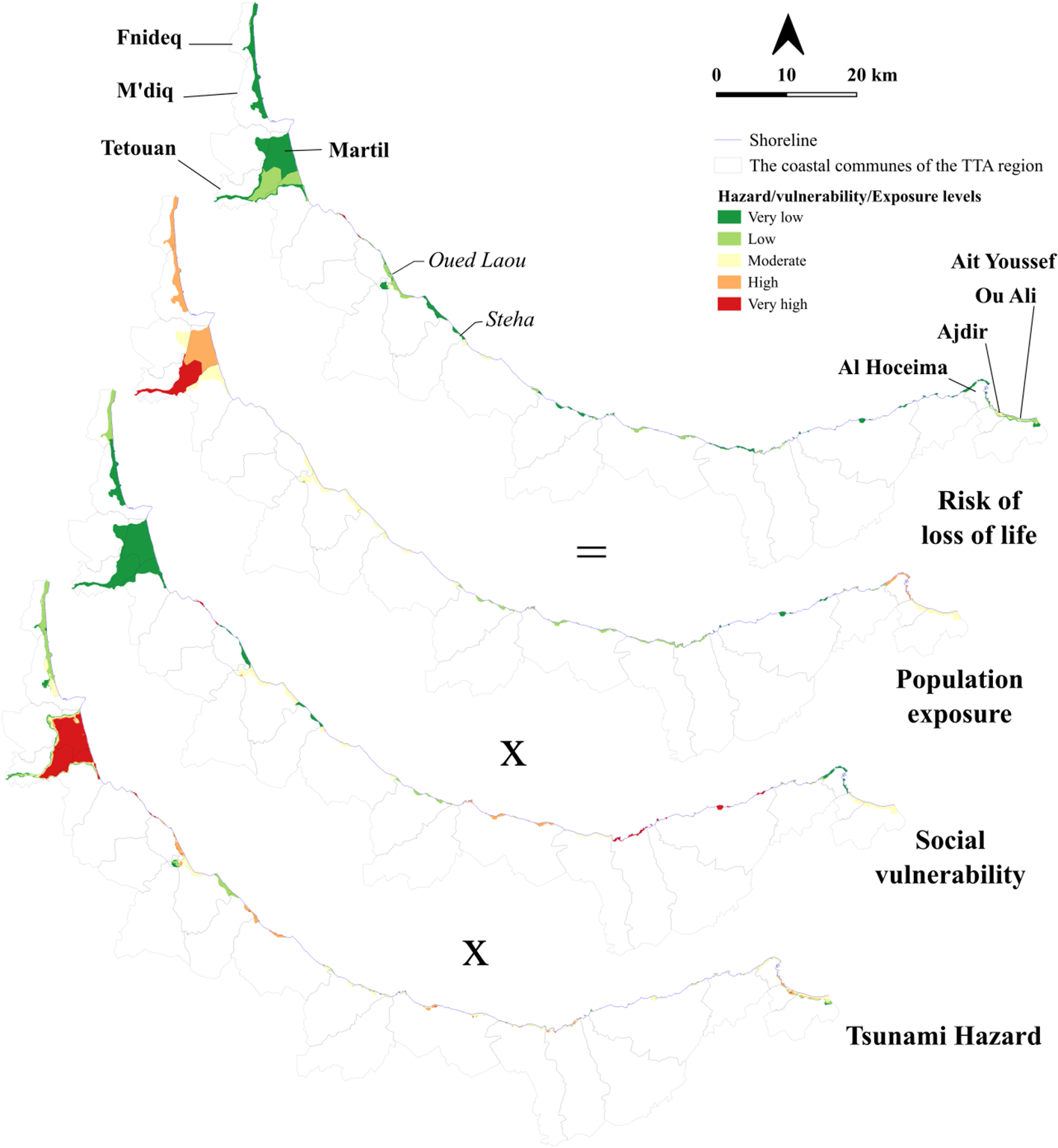

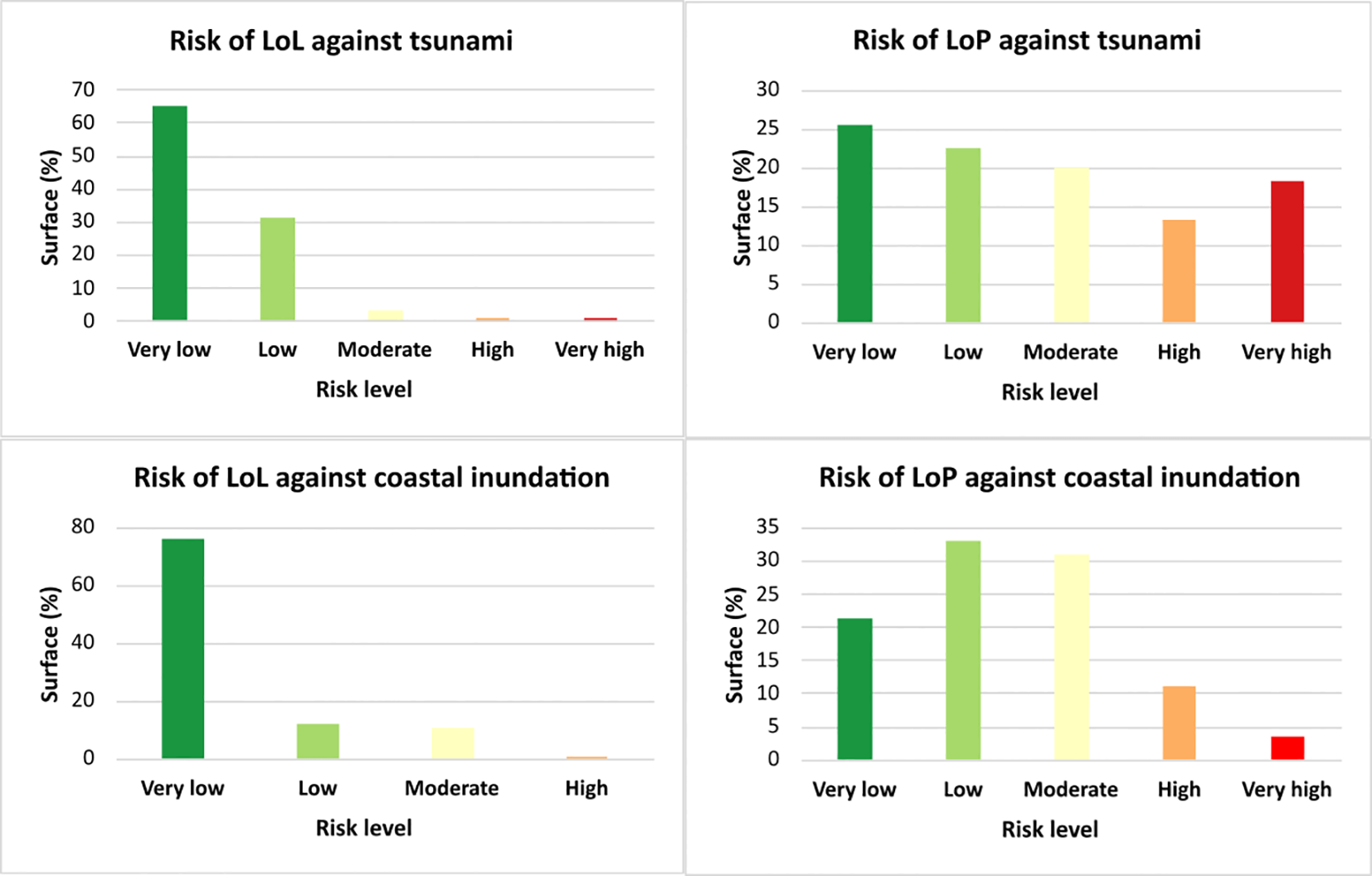

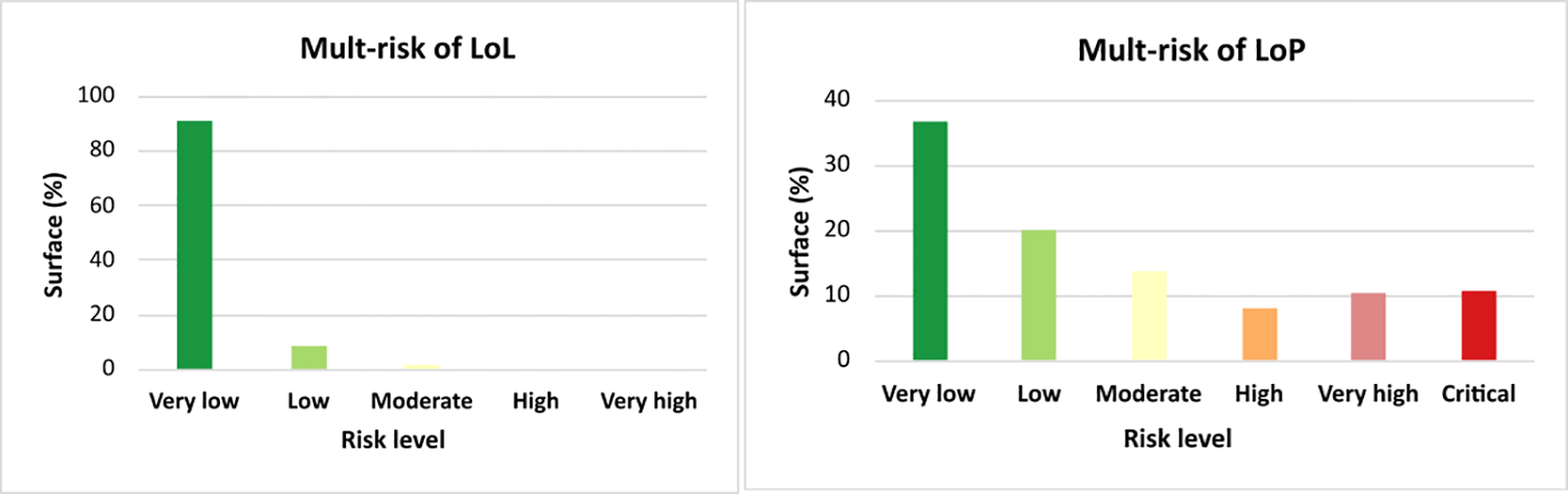

Tsunamis, as the most likely hazard associated with tectonic activity in the Alboran Sea, are analyzed in combination with vulnerability and exposure indices to assess tsunami risk in northern Morocco. The findings indicate an uneven distribution of risk intensity across coastal communes in the study area (Figures 5, 6). Analysis of the risk of loss of property (LoP) reveals that 32% of the hazard zone faces high to very high risk, while an additional 20% falls under moderate risk (Figure 7). Low-lying areas with unobstructed water flow, particularly through river systems, are most susceptible. Martil stands out as the most exposed location, as tsunami waves could surge inland via the Martil River. Elevated risk of LoP also extends along the coasts of M’diq (southern sector), Oued Laou, Stehat, Takmot, Al Hoceima, Ajdir, and Ait Youssef Ou Ali (Figure 5). Meanwhile, M’diq to Fnideq exhibit moderate coastal risk levels. The remaining communes in the study area show minimal tsunami risk potential.

Figure 5

Tectonic-driven tsunami risk to property: combining hazard, physical vulnerability, and property exposure.

Figure 6

Tectonic-driven tsunami risk to population: combining hazard, social vulnerability, and population exposure.

Figure 7

Descriptive statistics for tectonic and climate-driven risks.

The severity of tsunami impacts is strongly influenced by population density. To evaluate this, the risk of Loss of Life (LoL) was calculated by integrating social data with tsunami hazard mapping (Figure 6). The results indicate that over 90% of hazard zone face a low risk of LoL, while only 2%, primarily in Ajdir’s coastal area, show high LoL risk levels (Figure 7). Further analysis reveals significant disparities in social vulnerability across coastal municipalities in the study area. Urban communities generally demonstrate low social vulnerability, whereas rural areas exhibit moderate to high vulnerability. However, rural zones tend to be sparsely populated, while urban centers like Martil have much denser populations. As a result, despite urban areas lower social vulnerability, their high population concentration increases exposure, leading to a greater potential for severe tsunami consequences.

However, coastal communes such as Oued Laou, Stehat, and Ajdir remain highly vulnerable, lacking adequate defenses to protect critical infrastructure, including fishing ports and shoreline buildings, from tsunami threats. Urban areas like Martil face even greater risks, with waterfront neighborhoods particularly susceptible to extensive property damage. Meanwhile, the M’diq-Fnideq coastal stretch, while experiencing only moderate physical risk, requires prioritized mitigation efforts due to its strategic economic importance as a tourism hub.

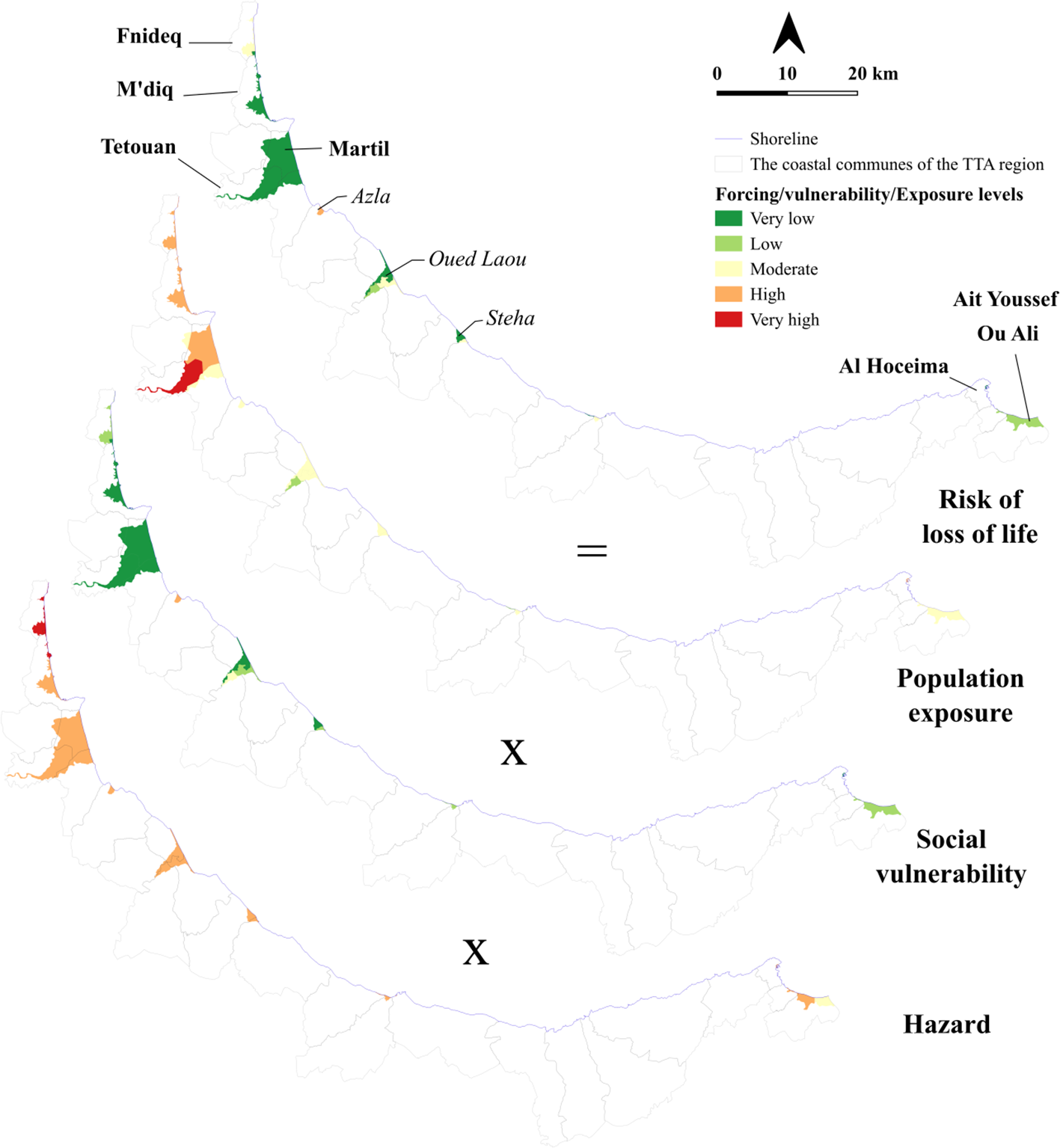

4.2 Climate change related coastal risk

Thus far, the accelerated impacts of climate change, such as sea-level rise, higher storm surge, and fluctuations in precipitation patterns, are widely documented as critical drivers of coastal risk (IPCC, 2022). These processes seem to be amplified in the study area, threaten low-lying coastal areas by increasing erosion risk, inundation frequency, and the vulnerability of these coastal socio-ecosystems, which provide several ecosystem services.

In this context, this study highlights the high exposure of low-lying coastal plains, such as Fnideq, M’diq, Martil, Azla, Oued Laou and Stihat, to coastal inundation due to sea-level rise and extreme storms (Figure 8). Through the application of the Hoozemans model, the maximum coastal inundation level by 2100 was estimated at approximately 8 m under worst-case climate scenarios. This projection exceeds earlier regional estimates (Snoussi et al., 2008), and highlights the magnitude of potential climate impacts along the Rif coastline. Referring to Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) topographic data and flood simulation (https://www.floodmap.net/?gi=2542987), the spatial distribution of inundation risk shows clear contrasts. Martil emerges as the most threatened hotspot, with simulated inundation depths of approximately 3.5–4 m across its densely urbanized plain. M’diq and Fnideq show localized flooding of 2–3 m, particularly around port facilities and tourist infrastructure. In Oued Laou, depths also reach 2–3 m within the river mouths, confirming the heightened vulnerability of such areas where marine and fluvial dynamics converge. Contrariwise, the steep coastal areas near Stihat and Al Hoceïma experience only limited inundation, as rugged land limits inland penetration despite exposure to extreme storm surges.

Figure 8

Climate change-driven inundation risk to property: combining hazard, physical vulnerability, and property exposure.

The risk of coastal inundation (Figures 8, 9) shows a strong contrast between the risk of loss of life (LoL) and loss of property (LoP). More than 75% of the coastal zone lies in the very low LoL category (Figure 7), confirming that sea-level rise and storm-driven inundation are unlikely to cause significant direct mortalities. However, the LoP distribution is more severe, with over 60% of the area in low to moderate categories and nearly 15% in high to very high-risk levels (Figure 7), indicating that climate change will primarily manifest through widespread property and infrastructure losses rather than immediate threats to human life. This pattern can be explained by the combined effects of accelerated sea-level rise, high-energy storm surges, and intense precipitation, which together enhance erosion and intensify inundation hazards in densely populated and economically strategic zones. Thus, in urban centers such Martil, the high population density and dominance of built-up land use near shorelines amplify property risks, intensified by the lack of natural buffer zones and limited protective infrastructure. Conversely, coastal rural centers, such as Stehat, Ajdir, Ait Youssef Ou Ali show increased social vulnerability due to limited adaptive capacity, despite lower population densities.

Figure 9

Climate-driven inundation risk to population: combining hazard, social vulnerability, and population exposure.

These findings confirm that climate forcing mechanisms, in interaction with the specific geomorphological context of the Rif coastline, characterized by a complex mosaic of vulnerable upland and lowland plains (Martil, Oued Laou…), significantly increase direct inundation risks and cascading risks to socio-economic activities.

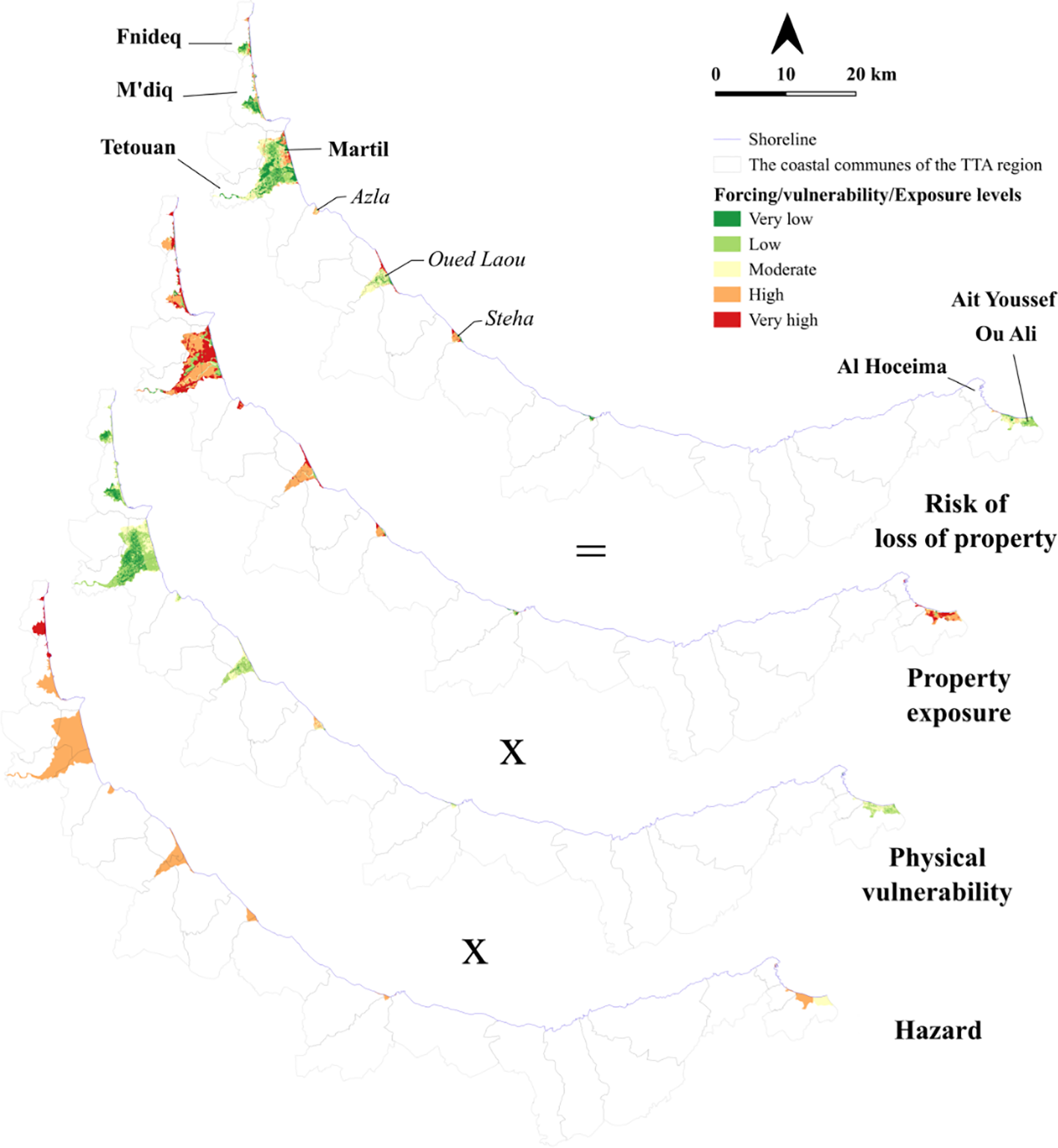

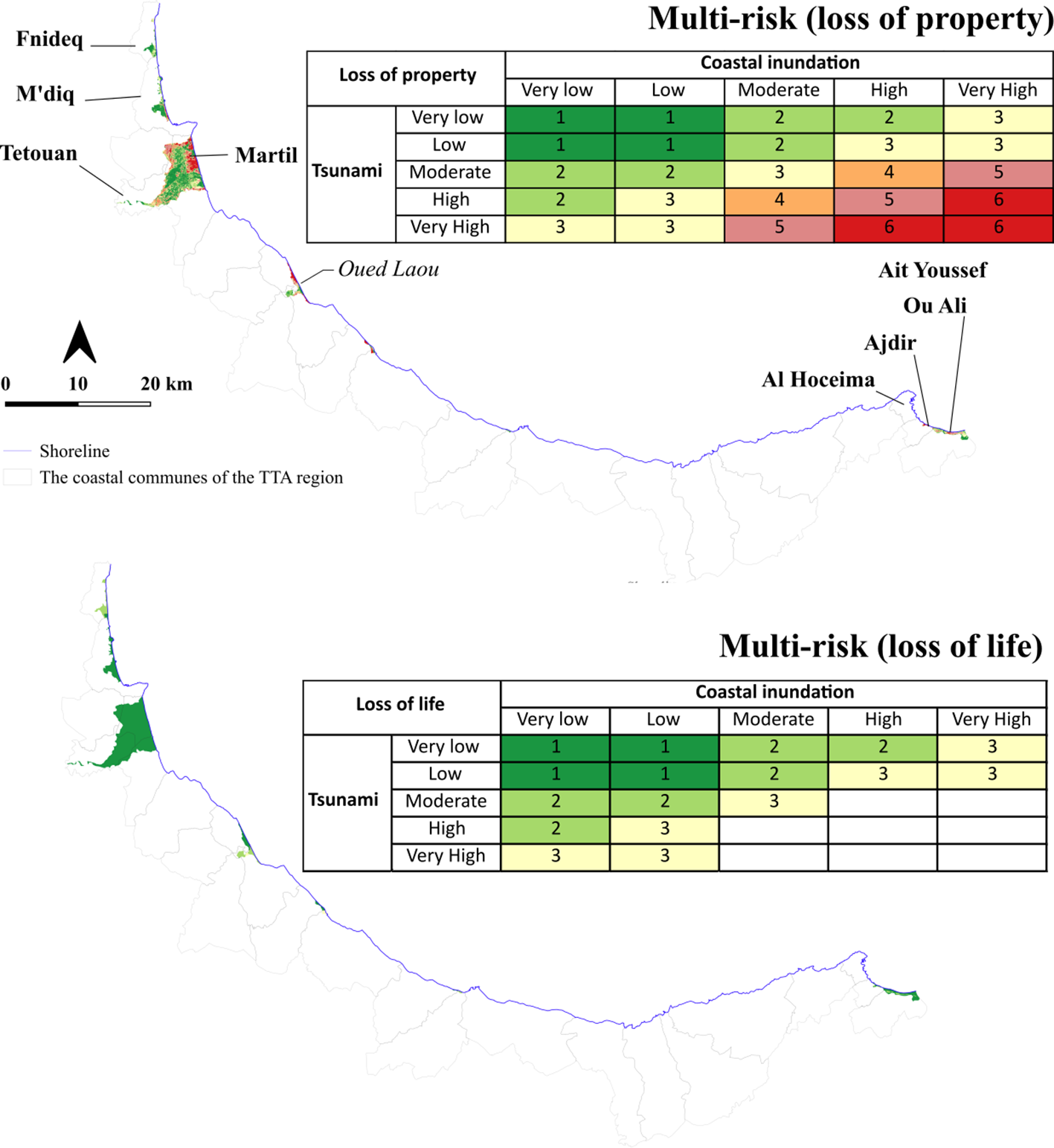

4.3 Multi-risks assessment

The research employed a spatial analysis of risk interactions to identify hotspots where these natural marine hazards may concurrently threaten lives and property (Figure 10). Using a matrix-based classification method, we reclassify combined risks to generate location-specific multi-risk profiles, enabling comprehensive risk assessment.

Figure 10

A multi-risk assessment mapping the combined threats of coastal inundation and tsunami for the risks of loss of property and loss of life.

The matrix-based integration of multi-hazards provides an effective visualization of risk distribution across the extensive study area (Luu et al., 2024). The analysis, based on raster data where each pixel represents a specific geographic area and risk value, reveals that 3.14 km² of land are exposed to overlapping tectonic and climate-related hazards. This multi-hazard risk is heavily concentrated in the urbanized Martil Plain, a region that shows exceptionally high pixel values corresponding to the level of LoP risk. Furthermore, the raster analysis pinpoints key coastal hotspots, such as Fnideq, M’diq, Oued Laou, Stihat, Ajdir, and Ait Youssef Ou Ali, as having the most severe combined risk levels identified in the data. Notably, elevated marine risks extend inland to low-lying sectors of Tetouan city beyond immediate coastal zones. The spatial risk analysis revealed distinct threat gradations across the study area, with critical risk zones comprising 11% of the total at-risk area (Figure 10), high-risk zones accounting for 19% (Figure 11), and moderate-risk zones representing 14%. These findings highlight widespread co-occurrence of tectonic and climate hazards, underscoring the urgent need for integrated mitigation strategies across hotspot locations.

Figure 11

Summary statistics characterizing the integrated risk values across the study area.

The analysis reveals that LoL risk from natural marine risks remains limited to moderate levels, primarily concentrated along the Oued Laou and Ait Youssef Ou Ali coastlines. These moderate-risk zones account for less than 2% of the total at-risk area (Figure 11). Notably, over 90% of the study region demonstrates very low risk levels, suggesting that local populations may possess inherent resilience factors that enhance their capacity to respond to natural risks.

5 Discussion

5.1 Reliability of natural marine hazard analyses

Coastal regions, characterized by high populations density and significant economic activity, place paramount importance on climate and tsunami risks assessment as part of their disaster risk reduction strategies (Sajjad and Chan, 2019). This is particularly relevant in the Mediterranean which is a geologically active maritime region, a densely populated coast and a hotspot of climate change. Such a context makes Mediterranean shores particularly vulnerable to natural hazards, putting human lives and property at risk. However, assessing the combined effects of coastal flooding induced both by climate change and tsunami hazards is complex and hard to determine. Few studies in the literature assessed simultaneously the effects of these two hazards. Dall’osso et al. (2014), for example, applied a probabilistic, multi-hazard approach to assess Sydney’s exposure to tsunamis, storms, and sea level rise. They concluded that tsunami hazard is dramatically increased due to higher SLR conditions. In the Eastern Mediterranean Sea, Yavuz et al. (2020) analyzed the coastal risk for potential earthquake triggered tsunamis (ETTs) coupled with predicted SLR. Their results showed that the contribution of climate-related SRL to ETTs depends on coastal topography and that increased risk levels are expected when both hazards are considered simultaneously in the risk analysis. They also noted that ignoring SLR will hinder realistic evaluation of ETT risks in the region.

In Morocco, to our knowledge, this is the first study that attempted to assess the coastal risk of flooding due to the combined effects of tsunami and climate change hazards. Our approach, although certainly perfectible, has nevertheless made it possible to identify the areas where the two hazards could potentially combine, putting human lives and property at risk of flooding and requiring urgent but adapted management measures. The results obtained are crucial and timely, as the TTA region is currently developing the integrated management plan for its coastal zones, taking into account all coastal risks.

In terms of research, these initial results open up interesting perspectives, particularly in terms of methodology, considering that, according to Sepúlveda et al. (2021), traditional tsunami hazard assessment approach where SLR is omitted or included as a constant sea-level offset in a probabilistic calculation may misrepresent the impacts of climate-change.

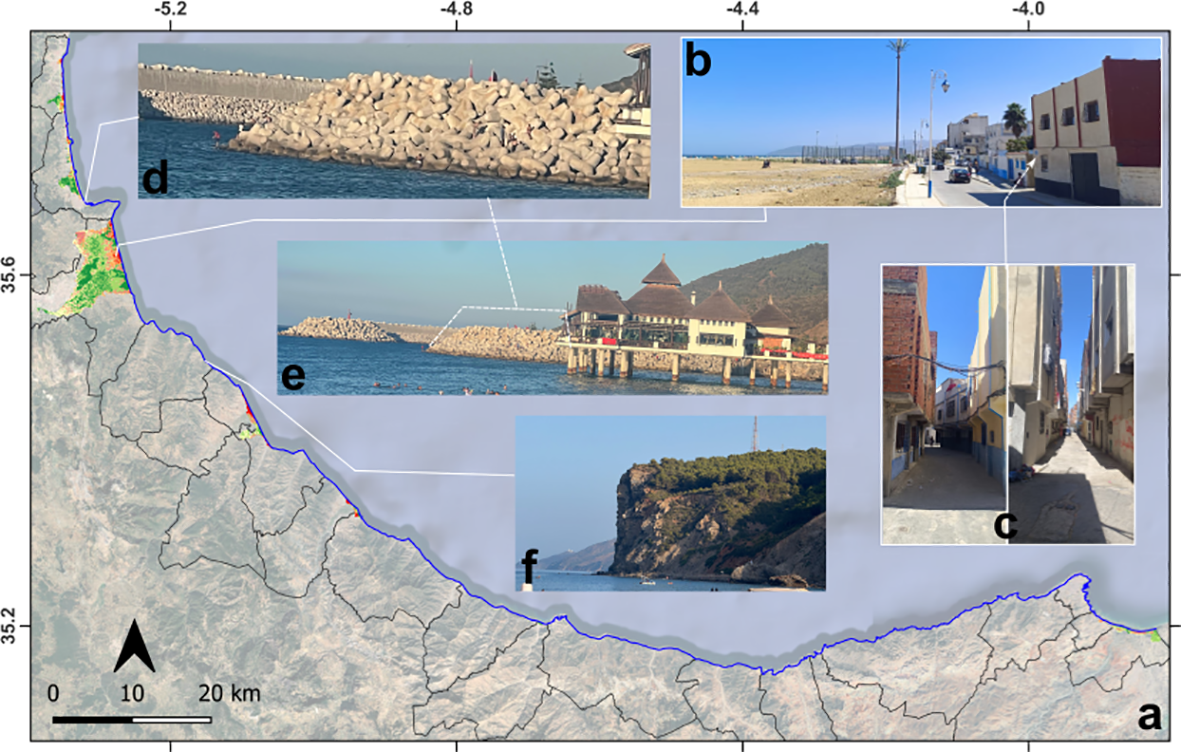

On the other hand, assessment of natural marine hazards in the study area reveals a relatively high risk of property loss from both tectonic and climate-related events. This preeminent risk is attributed to the convergence of high hazard levels and significant exposure. The high-risk zones identified for both hazard types are mainly located in low-lying areas, specifically the Martil Plain, Oued Laou, Stihat, and west of Al Hoceima (Figure 12). Conversely, physical vulnerability in these regions is assessed as moderate. This is largely due to the general morphology of the area, where the slope and elevation increase sharply inland (El Mrini et al., 2012), thus mitigating the impact of marine-origin events (Figure 13). With the notable exception of the Martil Plain, this trend is consistent throughout the study area. Furthermore, the observed shoreline changes are relatively moderate; the identified erosional hotspots, characterized by shoreline regression, show an average rate of -4 mm/year (Benkhattab et al., 2020). The presence of a developed road network, which can serve as a basis for evacuation strategies, can also help reduce physical vulnerability prior to or during a disaster, however, some narrow alleys within coastal building complexes, demonstrate the area’s high vulnerability and the challenge they pose for evacuation in the event of a tsunami (Figure 13c). Although the Mediterranean coast of Morocco remains understudied despite its susceptibility to tsunamis and storm surges (Khalfaoui et al., 2023), our results are consistent with the limited previous research, such as Khouakhi et al. (2013), who confirm that physical vulnerability in Al Hoceima Bay is moderate, and the work of Outiskt et al. (2025) who report that the vulnerability of building to tsunamis is generally low to moderate in the city of Martil. This assessment is somewhat different from previous studies that reported high vulnerability of low-lying coastal areas (Snoussi et al., 2008; Satta et al., 2016; Agharroud et al., 2023). This discrepancy likely arises because those studies incorporate anthropogenic pressures into their vulnerability metrics, a factor excluded from the present physical vulnerability assessment (Figure 13e). This suggests that vulnerability increases significantly in areas subject to greater human forcing.

Figure 12

Maps and photographs of the most significant areas, identifying multi-risk coastal hotspots. (a) the low-lying city of Martil; (b) the low-lying city of Oued Laou; (c, d) examples of highly vulnerable issues at stake in the Dezza district, located on dead-arm of the Martil River near the coast.

Figure 13

(a) A multi-risk map showing the potential for property loss, overlaid onto a Google Satellite map; (b) a photograph of buildings located near the coast in the low-lying city of Martil; (c) Narrow alleys within the coastal building complexes, demonstrating the area’s high vulnerability and the challenge they pose for evacuation during a tsunami; (d, e) Defensive structures in M’diq port, shown as an example of an engineering solution to climate-related risks. The tourist facilities built over the water remain directly exposed to marine hazards. (f) An example of the coastal morphology that serves as a natural barrier that protects some risk-free zones (photograph at Tamernout) within the study area.

For instance, the Diza Sidi Abdelsalam district of Martil is situated directly on the banks of the Martil River, where a former meander has been abandoned and transformed into a stagnant backwater (Figure 12d). This geomorphological feature functions as a receptacle for untreated wastewater and solid waste, contributing to severe environmental degradation. In the event of a tsunami, the strong wave energy could resuspend and disperse these polluted waters over a wide area, facilitating the spread of pathogenic microorganisms and chemical contaminants and thereby increasing the risk of waterborne diseases and secondary health crises in the aftermath (Manual, 2010). These environmental vulnerabilities are further compounded by the socio-economic dynamics of Martil, a major coastal destination that experiences a substantial seasonal influx of tourists, particularly during the summer months. This demographic surge not only places additional pressure on already limited sanitation and infrastructure systems but also significantly increases the exposure of a transient population to tsunami hazards (Logan et al., 2018). The convergence of polluted oxbow waters, inadequate urban sanitation, and seasonal tourism pressure creates a multi-dimensional risk scenario in which even a moderate tsunami event could simultaneously trigger environmental, sanitary, and socio-economic crises.

Conversely, the results indicate that the risk of LoL is generally low to moderate for both climate and tectonic related risks. This assessment is primarily based on population resilience metrics. While significant hazards from active tectonics and climate change are undoubtedly present and potentially severe, and exposure remains high due to dense coastal populations (El Mrini et al., 2013), social vulnerability is notably low. Clarifying this point, this study evaluated social vulnerability using three key variables from the latest census data (HCP, 2024), to understand the population’s adaptive capacity. First, the elderly person and disability rate were analyzed to gauge the population’s ability to respond effectively to hazards. In high-exposure urban zones, the percentage of people over 65 years old and those with disabilities is low, enhancing community responsiveness and reducing the overall severity of LoL risk. Second, the illiteracy rate was used as a proxy for the potential effectiveness of public awareness campaigns (Noy and Yonson, 2018). Similar to the other factors, illiteracy is low in populated areas (as Martil city) (HCP, 2024), suggesting an inherent capacity for public education on natural hazards that need to be enhanced (Ivčević et al., 2025). This finding appears to contrast with studies on risk perception, which indicate that public awareness of marine-generated disasters is not robust (Ivčević et al., 2020, 2021). Local perception of risk is instead shaped by lived experience; northern residents (Oued Laou to Fnideq) perceive flooding and coastal storms as the primary threats, while southern residents (Al Hoceima to Oued Laou) are more concerned with earthquakes and flooding, with little mention of specific coastal hazards (Ivčević et al., 2021). It is worth mentioning here that the weak coastal governance experienced by the region amplifies the impacts of natural marine hazards (Idllalène, 2024). Indeed, Ivčević et al. (2025) identified a critical imbalance between stakeholder engagement and institutional coordination, coupled with increasing bureaucratization that obscures accountability. In conclusion, while the calculated risk to human life is currently low to moderate, the combination of high physical hazard levels and a lack of comprehensive public awareness requires proactive measures. The implementation of integrated coastal zone management is urgently recommended to develop a regional coastal plan that addresses these gaps.

5.2 Addressing threats from coastal hazards

To address the impacts of natural marine hazards, coastal zones most at risk should be prioritized for enhanced measures that combine protection and mitigation strategies for both tectonic and climate-related risks. A variety of approaches can be employed, such as nature-based solutions (NbS) for climate adaptation (Kumar et al., 2020; IPCC, 2022), early warning systems, and innovative technologies for vertical evacuation in tsunami events (Wächter et al., 2012; León et al., 2024).

In Morocco, many laws and frameworks, including the Coastal Law (Law No. 81-12), have long been adopted to protect the coastline against coastal risks. However, their implementation is still far from being effective. It is hoped that the operational plan of the National Risk Management Strategy 2021–2031 will address these gaps. Indeed, this plan highlights two key projects focused on coastal areas (Agharroud et al., 2023 and reference therein): (1) Conducting studies and developing scenarios related to marine flooding and coastal erosion, along with corresponding mitigation measures for vulnerable zones; (2) Undertaking tsunami risk studies and scenario development for high-priority areas. Aside from these initiatives, various management actions have been implemented to lessen coastal hazards and safeguard infrastructure from erosion (Figures 13d, e). However, these measures appear inadequate given the accelerating effects of climate change, which have significantly worsened coastal erosion (Sedrati and Anthony, 2007). Agharroud et al. (2023) discuss several climate change adaptation options based on the combining of both hard structures (seawalls, breakwaters…) and NbS (as fixation and revegetation of the coastal dunes). These solutions could be also important to protect coastal zone from the tsunami event if the maximum wave height and run-up height is not elevated.

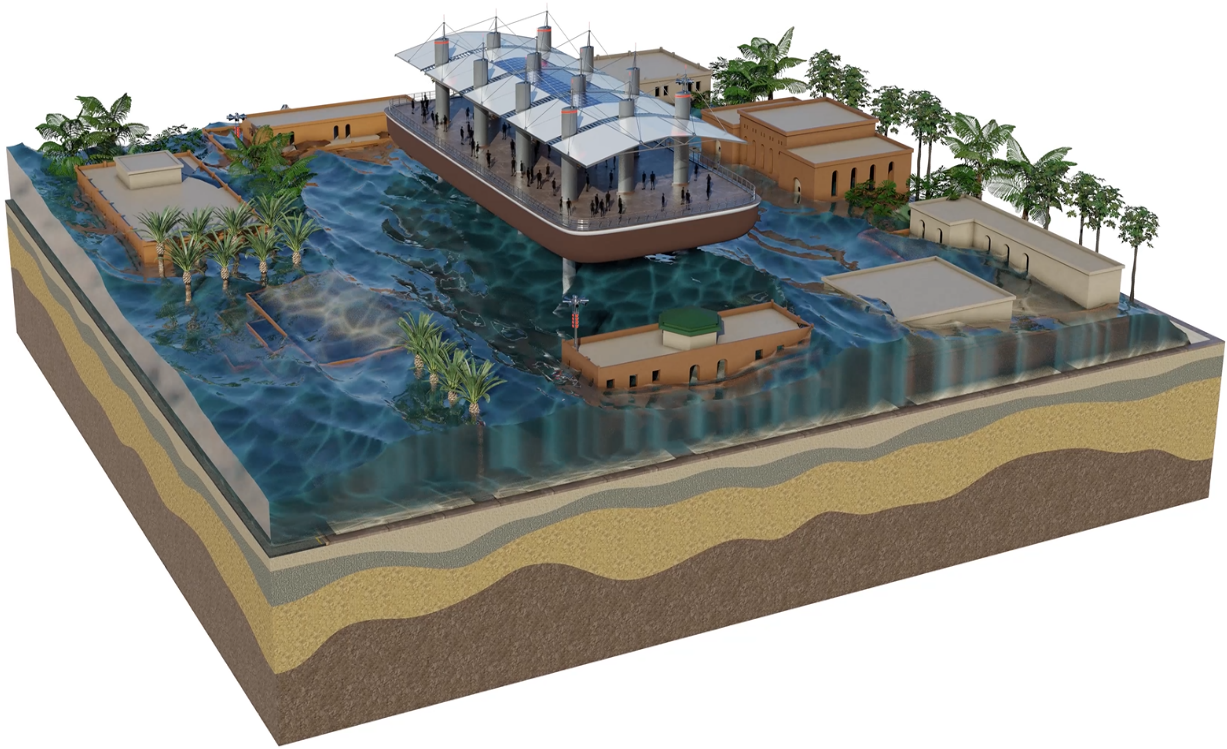

5.3 Tsunami mitigation solution with applications for climate hazards

Preparedness for tsunamis, in particular, requires careful management and planning (Kannangara et al., 2022). Evacuation is the most effective strategy for saving lives during a tsunami (Sun et al., 2017). When a tsunami is generated locally, the available response time is often very short (Angove et al., 2019), making vertical evacuation to the upper floors of resilient buildings or to high ground a critical priority for saving lives in at-risk coastal communities. However, it should be noted that not all areas along Morocco’s Mediterranean coast have multi-story buildings suitable for use as vertical refuges or easily accessible high ground, particularly in threated cities as Martil, M’diq, Fnideq and Oued Laou.

According to a quantitative assessment (Outiskt et al., 2025), a tsunami event would cause significant material losses, estimated at up to $3.72 million, exclusively in Martil. The human cost is projected to be even more severe, with potential fatalities reaching 31,000. To mitigate such catastrophic loss of life, the Anti-Tsunami Platform from DryUp Swiss Technology offers an effective protective solution (Figure 14). This rapidly deployable system features a satellite-linked control center for operational management and public alert dissemination. Upon receiving a tsunami warning, the platform, comprising a hollow buried base and a column-supported roof, automatically elevates to safeguard evacuees.

Figure 14

Example of solution to provide safety in case of tsunami (the Anti-Tsunami-Platform).

Other structural approaches are being implemented and proposed to ensure the protection of populations. These solutions include elevated evacuation platforms, designed to provide temporary refuge above the expected flood level (Figure 14). They have the advantage of being quickly accessible and able to accommodate large numbers of people. However, land constraints often limit their installation in at risk areas. Vertical reinforced concrete shelters are also a solution that is generally integrated into public or private buildings and are an effective alternative in areas where space is limited. Their structural robustness is a major advantage, although their capacity remains modest and their effectiveness depends heavily on their proximity to residential areas. However, it is also important to note that the coastal effectiveness of such an installation may be a concern for Moroccan authorities. Ultimately, the effectiveness of this kind of system is contingent on its integration with a reliable early warning system, public awareness campaigns, and other complementary risk reduction measures (Tadibaght et al., 2022a; Outiskt et al., 2025).

On the other hand, more cost-effective and ecological defense strategies, such as foresting vulnerable coasts, can be adopted (Scoccimarro, 2020). One can also benefit from the experience of Japan, where a major engineered response to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami was the construction of an extensive 370 km seawall, costing nearly 10 billion euros. The wall’s design is tailored to the local topography: it stands at 14.7m in Sanriku, 8-10m in the low-lying Sendai Bay, and a massive 28m at the Fukushima nuclear site. A similar project in Hamamatsu (Shizuoka) features a 15m wall stretching 17.5 km (Scoccimarro, 2020).

Despite all the techniques mentioned previously, their effectiveness remains limited without sufficient awareness-raising and educational activities on tsunami risks, particularly those conducted through the media, schools, and civil society events. Many regions around the world still suffer from a lack of communication on this issue, especially in developing countries, which often only react after a disaster has occurred rather than proactively.

Consequently, media pressure is considered one tool that can be used to lobby governments and authorities to adopt reasonable strategies to protect people and property. Hence, Morin et al. (2008) argue that the media play an important role in disseminating information to citizens quickly, clearly, and proactively, which can significantly reduce damage. Furthermore, people’s curiosity to witness a tsunami event firsthand, as well as the impulse of some surfers to head toward the ocean during the initial waves, as observed in Indonesia in 2004 and New Caledonia in 2007, leads to material and human losses that could otherwise have been avoided.

6 Conclusion

This study attempted to assess marine-origin risks threatening the Mediterranean coastal zones of the TTA region in northern Morocco. It aimed to fill a gap in disaster risk evaluation by encompassing all its dimensions (hazards, vulnerability, and exposure) in alignment with the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction framework. The results reveal a significant risk of LoP and a moderate risk of LoL from both tectonic and climate-related hazards, especially in low-lying areas. Tsunami hazards place up to 32% of the hazardous zone at a high level of property loss risk, but only up to 2% for loss of life. While the analysis excluded the compound effect of a tsunami superimposed on sea-level rise, this presents a significant opportunity for future methodological development. For climate-related risks, 15% of the total threatened area is at a high level of property loss risk, with up to 15% at a moderate-to-high level. Multi-risk mapping indicates that up to 30% of the hazard zone is characterized by high to very high levels of property loss risk. The city of Martil is identified as the most threatened area. It is a critical hotspot where the threats of tectonically-induced tsunamis and climate-induced coastal inundation intersect. Other key hotspots include the coasts of Fnideq, M’diq, Oued Laou, Stihat, and Ait Youssef Ou Ali. The risk to human life remains low throughout the study area. Consequently, this study concludes that mitigating the impacts of natural marine hazards should be a priority, with a focus on strengthening coastal defenses. These measures should combine mitigation strategies for both tectonic and climate-related risks. While innovative solutions like anti-tsunami platforms and super-seawalls may be considered by Moroccan authorities, a combination of hard engineering, Nature-based Solutions (NbS), and more cost-effective ecological defenses, coupled with public awareness and educational campaigns, could significantly improve preparedness for natural marine hazards in northern Morocco.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

KA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AT: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MO: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OE: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HR: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AE: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Frontiers in Marine Science for the crucial support for the open-access dissemination of this work. Our thanks go to João Francisco Pinto Ramos of DryUP Swiss Technology SA for his collaborative support and for sharing the technical details of the innovative anti-tsunami platform. We express our gratitude to the reviewers whose comments and remarks significantly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1695978/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abbassi A. Cipollari P. Zaghloul M. N. Cosentino D. (2020). The Rif chain (Northern Morocco) in the late tortonian-early messinian tectonics of the Western Mediterranean orogenic belt: evidence from the tanger-al manzla wedge-top basin. Tectonics39, e2020TC006164. doi: 10.1029/2020TC006164

2

Agharroud K. (2022). Tectonique active du front sud de la chaîne rifaine (Tronçon Fès-Meknès, Nord du Maroc) : Approche morpho-chronologique (Tétouan: Université Abdelmalek Essaâdi).

3

Agharroud K. Puddu M. Ivčević A. Satta A. Kolker A. S. Snoussi M. (2023). Climate risk assessment of the Tangier-Tetouan-Al Hoceima coastal Region (Morocco). Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/FMARS.2023.1176350

4

Agharroud K. Siame L. L. Ben Moussa A. Bellier O. Guillou V. Fleury J. et al . (2021). Seismo-tectonic model for the southern pre-Rif border (Northern Morocco): insights from morphochronology. Tectonics40, e2020TC006633. doi: 10.1029/2020TC006633

5

Aitali R. Snoussi M. Kasmi S. (2020). Coastal development and risks of flooding in Morocco: The cases of Tahaddart and Saidia coasts. J. Afr. Earth Sci.164, 103771. doi: 10.1016/J.JAFREARSCI.2020.103771

6

Al Mashoudi A. Akallouch A. Arraji M. Samlali A. Tariq A. (2025). Unraveling seasonal rainfall dynamics in the Western Rif, Morocco, (1980–2019): A multivariate SPI-based analysis. Earth Syst. Environ.2025, 1–24. doi: 10.1007/S41748-025-00733-9

7

Alvarez I. Diaz-Poso A. Lorenzo M. N. Roye D. (2024). Heat index historical trends and projections due to climate change in the Mediterranean basin based on CMIP6. Atmos Res.308, 107512. doi: 10.1016/J.ATMOSRES.2024.107512

8

Anfuso G. Nachite D. (2011). “ Climate change and the mediterranean southern coasts,” in Disappearing Destinations: Climate Change and Future Challenges for Coastal Tourism. Preston, UK: CAB International, 99–110. doi: 10.1079/9781845935481.0099

9

Angove M. Arcas D. Bailey R. Carrasco P. Coetzee D. Fry B. et al . (2019). Ocean observations required to minimize uncertainty in global tsunami forecasts, warnings, and emergency response. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/FMARS.2019.00350

10

Baptista M. A. Heitor S. Miranda J. M. Miranda P. Mendes Victor L. (1998). The 1755 Lisbon tsunami: evaluation of the tsunami parameters. J. Geodyn25, 143–157. doi: 10.1016/s0264-3707(97)00019-7

11

Basquin E. El Baz A. Sainte-Marie J. Rabaute A. Thomas M. Lafuerza S. et al . (2023). Evaluation of tsunami inundation in the plain of Martil (north Morocco): Comparison of four inundation estimation methods. Natural Hazards Res.3, 494–507. doi: 10.1016/J.NHRES.2023.06.002

12

Benkhattab F. Z. Hakkou M. Bagdanavičiūtė I. El Mrini A. Zagaoui H. Rhinane H. et al . (2020). Spatial–temporal analysis of the shoreline change rate using automatic computation and geospatial tools along the Tetouan coast in Morocco. Natural Hazards104, 519–536. doi: 10.1007/S11069-020-04179-2

13

Chalouan A. Michard A. (1990). The ghomarides nappes, Rif coastal range, Morocco: A variscan chip in the alpine belt. Tectonics9, 1565–1583. doi: 10.1029/TC009I006P01565

14

Civiero C. Custódio S. Duarte J. C. Mendes V. B. Faccenna C. (2020). Dynamics of the Gibraltar arc system: A complex interaction between plate convergence, slab pull, and mantle flow. J. Geophys Res. Solid Earth125, e2019JB018873. doi: 10.1029/2019JB018873

15

d’Acremont E. Gutscher M. A. Rabaute A. Mercier de Lépinay B. Lafosse M. Poort J. et al . (2014). High-resolution imagery of active faulting offshore Al Hoceima, Northern Morocco. Tectonophysics632, 160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tecto.2014.06.008

16

Dall’osso F. Dominey-Howes D. Moore C. Summerhayes S. Withycombe G. (2014). The exposure of Sydney (Australia) to earthquake-generated tsunamis, storms and sea level rise: A probabilistic multi-hazard approach. Sci. Rep.4, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/SREP07401

17

Deitch M. J. Sapundjieff M. J. Feirer S. T. (2017). Characterizing precipitation variability and trends in the world’s Mediterranean-climate areas. Water 2017 Vol. 9 Page259 9, 259. doi: 10.3390/W9040259

18

De Pippo T. Donadio C. Pennetta M. Petrosino C. Terlizzi F. Valente A. (2008). Coastal hazard assessment and mapping in Northern Campania, Italy. Geomorphology97, 451–466. doi: 10.1016/J.GEOMORPH.2007.08.015

19

Ed-Dakiri S. Etebaai I. Moussaoui S. Tawfik A. Lamgharbaj M. El H. et al . (2024). Assessing soil erosion risk through geospatial analysis and magnetic susceptibility: A study in the Oued Ghiss dam watershed, Central Rif, Morocco. Sci. Afr26, e02401. doi: 10.1016/J.SCIAF.2024.E02401

20

El Mrini A. (2011). Evolution morphodynamique et impact des aménagements sur le littoral tétouanais entre RAS Mazari et fnideq (Maroc Nord Occidental) (Tétouan, Morocco: Université Abdelmalek Essaâdi).

21

El Mrini A. Anthony E. J. Taaouati M. Nachite D. Maanan M. (2013). A note on contrasting morphodynamics of two beach systems with different backshores, Tetouan coast, northwest Morocco: the role of grain size and human-altered dune morphology. J. Coast. Res.165, 1283–1288. doi: 10.2112/SI65-217.1

22

El Mrini A. Maanan M. Anthony E. J. Taaouati M. (2012). An integrated approach to characterize the interaction between coastal morphodynamics, geomorphological setting and human interventions on the Mediterranean beaches of northwestern Morocco. Appl. Geogr.35, 334–344. doi: 10.1016/J.APGEOG.2012.08.009

23

Erol A. Randhir T. O. (2012). Climatic change impacts on the ecohydrology of Mediterranean watersheds. Clim Change114, 319–341. doi: 10.1007/S10584-012-0406-8/METRICS

24

Estrada F. Galindo-Zaldívar J. Vázquez J. T. Ercilla G. D’Acremont E. Alonso B. et al . (2018). Tectonic indentation in the central Alboran Sea (westernmost Mediterranean). Terra Nova30, 24–33. doi: 10.1111/ter.12304

25

Estrada F. González-Vida J. M. Peláez J. A. Galindo-Zaldívar J. Ortega S. Macías J. et al . (2021). Tsunami generation potential of a strike-slip fault tip in the westernmost Mediterranean. Sci. Rep.11, 16253. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95729-6

26

Fannassi Y. Ennouali Z. Hakkou M. Benmohammadi A. Al-Mutiry M. Elbisy M. S. et al . (2023). Prediction of coastal vulnerability with machine learning techniques, Mediterranean coast of Tangier-Tetouan, Morocco. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci.291, 108422. doi: 10.1016/J.ECSS.2023.108422

27

Gallina V. Torresan S. Zabeo A. Critto A. Glade T. Marcomini A. (2020). A multi-risk methodology for the assessment of climate change impacts in coastal zones. Sustainability 2020 Vol. 12 Page3697 12, 3697. doi: 10.3390/SU12093697

28

Haissen A. El K. Zourarah B. Hakkou M. Chair A. Ettahiri O. et al . (2025). Coastal watershed and morphologic changes of their mouth along the Moroccan Mediterranean coastline. EuroMediterr J. Environ. Integr.10, 1523–1544. doi: 10.1007/S41207-024-00677-Y

29

Hanks T. C. Kanamori H. (1979). A moment magnitude scale. J. Geophys Res. Solid Earth84, 2348–2350. doi: 10.1029/JB084IB05P02348

30

Hassoun A. E. R. Mojtahid M. Merheb M. Lionello P. Gattuso J. P. Cramer W. (2025). Climate change risks on key open marine and coastal mediterranean ecosystems. Sci. Rep.15, 1–20. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-07858-x

31

HCP (2024). Annuaires Statistiques de la région. Available online at: https://www.hcp.ma/reg-alhoceima/Annuaires-Statistiques-de-la-region_a2.html (Accessed August 11, 2025).

32

Hochrainer-Stigler S. Trogrlić Šakić R. Reiter K. Ward P. J. de Ruiter M. C. Duncan M. J. et al . (2023). Toward a framework for systemic multi-hazard and multi-risk assessment and management. iScience26, 106736. doi: 10.1016/J.ISCI.2023.106736

33

Hoozemans F. M. J. Marchand M. Pennekamp H. A. . (1993). “ Sea Level rise: a global vulnerability assessment – vulnerability assessments for population, coastal wetlands and rice production on a global scale,” in Delft hydraulics and rijkswaterstaat, 2nd ed. (Delft/The Hague: Deltares (WL)), 184.

34

Idllalène S. (2024). An Illustrative Model of (Non) Local Governance: Morocco’s Coastal ZonesLocal and Urban Governance . 233–248, Part F3225. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-60657-1_15

35

IPCC (2014). Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/SYR_AR5_FINAL (Accessed August 23, 2025).

36

IPCC (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

37

Ivčević A. Bertoldo R. Mazurek H. Siame L. Guignard S. Ben Moussa A. et al . (2020). Local risk awareness and precautionary behaviour in a multi-hazard region of North Morocco. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduction50, 101724. doi: 10.1016/J.IJDRR.2020.101724

38

Ivčević A. Mazurek H. Siame L. Bertoldo R. Statzu V. Agharroud K. et al . (2021). Lessons learned about the importance of raising risk awareness in the Mediterranean region (north Morocco and west Sardinia, Italy). Natural Hazards Earth System Sci.21, 3749–3765. doi: 10.5194/NHESS-21-3749-2021

39

Ivčević A. Povh Škugor D. Snoussi M. Karner M. Kervyn M. Hugé J. (2025). Identifying success factors for integrated coastal zone management: Development of a regional coastal plan in Morocco. Environ. Sci. Policy167, 104027. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2025.104027

40

Kaabouben F. Baptista M. A. Iben Brahim A. El Mouraouah A. Toto A. (2009). On the moroccan tsunami catalogue. Natural Hazards Earth System Sci.9, 1227–1236. doi: 10.5194/nhess-9-1227-2009

41

Kannangara K. K. C. L. Adikariwattage V. V. Siriwardana C. S. A. (2022). “ Development of a cost-optimized model for evacuation route planning for tsunamis,” in 2022 Moratuwa Engineering Research Conference (MERCon), Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, IEEE. doi: 10.1109/MERCON55799.2022.9906279

42

Khalfaoui O. Dezileau L. Mhammdi N. Medina F. Mojtahid M. Raji O. et al . (2023). Storm surge and tsunami deposits along the Moroccan coasts: State of the art and future perspectives. Natural Hazards117, 2113–2137. doi: 10.1007/s11069-023-05940-z

43

Khouakhi A. Snoussi M. Niazi S. Raji O. (2013). Vulnerability assessment of Al Hoceima bay (Moroccan Mediterranean coast): a coastal management tool to reduce potential impacts of sea-level rise and storm surges. J. Coast. Res.65, 968–973. doi: 10.2112/SI65-164.1

44

Koulali A. Ouazar D. Tahayt A. King R. W. Vernant P. Reilinger R. E. et al . (2011). New GPS constraints on active deformation along the Africa-Iberia plate boundary. Earth Planet Sci. Lett.308, 211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.05.048

45

Kumar P. Debele S. E. Sahani J. Aragão L. Barisani F. Basu B. et al . (2020). Towards an operationalisation of nature-based solutions for natural hazards. Sci. Total Environ.731, 138855. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2020.138855

46

Larrey M. Mouthereau F. Do Couto D. Masini E. Jourdon A. Calassou S. et al . (2023). Oblique rifting triggered by slab tearing: the case of the Alboran rifted margin in the eastern Betics. Solid Earth14, 1221–1244. doi: 10.5194/SE-14-1221-2023

47

León J. Ogueda A. Gubler A. Catalán P. Correa M. Castañeda J. et al . (2024). Increasing resilience to catastrophic near-field tsunamis: systems for capturing, modelling, and assessing vertical evacuation practices. Natural Hazards120, 9135–9161. doi: 10.1007/S11069-022-05732-X

48

Logan T. M. Guikema S. D. Bricker J. D. (2018). Hard-adaptive measures can increase vulnerability to storm surge and tsunami hazards over time. Nature Sustainability1, 526–530. doi: 10.1038/s41893-018-0137-6

49

Luis J. F. (2007). Mirone: a multi-purpose tool for exploring grid data. Comput. Geosci33, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cageo.2006.05.005

50

Luu C. Forino G. Yorke L. Ha H. Bui Q. D. Tran H. H. et al . (2024). Integrating susceptibility maps of multiple hazards and building exposure distribution: a case study of wildfires and floods for the province of Quang Nam, Vietnam. Natural Hazards Earth System Sci.24, 4385–4408. doi: 10.5194/NHESS-24-4385-2024

51

Maanan M. Maanan M. Rueff H. Adouk N. Zourarah B. Rhinane H. (2018). Assess the human and environmental vulnerability for coastal hazard by using a multi-criteria decision analysis. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess.24, 1642–1658. doi: 10.1080/10807039.2017.1421452

52

Mansinha L. Smylie D. E. (1971). The displacement fields of inclined faults. Bull. Seismological Soc. America61, 1433–1440. doi: 10.1785/BSSA0610051433

53

Manual F. P. (2010). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Office of Coast Survey, 154–155.

54

Mellas S. Leone F. Omira R. Gherardi M. Baptista M.-A. Zourarah B. et al . (2012). Le risque tsunamique au Maroc: modélisation et évaluation au moyen d’un premier jeu d’indicateurs d’exposition du littoral atlantique. Géographie physique et environnement (Physio-Géo)6, 119–139. doi: 10.4000/PHYSIO-GEO.2589

55

Mhammdi N. Medina F. Belkhayat Z. El Aoula R. Geawahri M. A. Chiguer A. (2020). Marine storms along the Moroccan Atlantic coast: An underrated natural hazard? J. Afr. Earth Sci.163, 103730. doi: 10.1016/J.JAFREARSCI.2019.103730

56