Abstract

The establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the Southern Ocean is crucial for the conservation of the Southern Ocean ecosystem and thus contributes to the adaptation to impacts of climate change and anthropogenic pressures. However, despite efforts by the Commission on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), progress in establishing MPAs has stagnated over the past decade. Current academic interpretations focus primarily on geopolitical and economic factors, such as fishing interests, often overlooking other underlying constraints. This article adopts an institutionalist perspective to explore the structural factors hindering MPA development, including uncertainty in scientific data, forum shopping, and the lack of legal commitment. By critically reviewing recent MPA negotiations and summarizing their key characters, this article identifies several structural constraints to more progress in MPA development. It also proposes a series of practical strategies for CCAMLR to overcome these challenges, highlighting the need for accommodating competing interests, refining MPA definitions, harmonizing criteria, designing enforcement mechanisms, and aligning itself with international regimes relating to spatial protection of marine ecosystems such as the Agreement on Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement). The article argues that minimizing these structural constraints is essential for achieving a robust, representative MPA system in the Southern Ocean, thereby contributing to global marine conservation and climate adaptation efforts.

1 Introduction

The Southern Ocean, covering 9.6% of the world’s oceans, plays a key role in global marine ecosystems, leveraging biodiversity and providing essential services that regulate global climate (Xavier et al., 2016; Cavanagh et al., 2021, p.2). However, it is also one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change, experiencing rapidly increasing temperature, ice loss, and shifts in ecosystem composition. These changes have profound implications not only for the Southern Ocean’s ecosystems but also for the planet’s overall environmental health (Murphy et al., 2021, p.2; Rogers et al., 2020, p.7.23). Establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the Southern Ocean is recognized as an essential strategy to mitigate the impacts of climate change, preserve marine biodiversity, and enhance the resilience of these ecosystems (Tittensor et al., 2019; Brooks et al., 2020). The definition of an MPA was initially proposed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), as ‘any area of intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by law or other effective means to protect part or all of the enclosed environment’ (IUCN, 2012). MPAs are central to international conservation efforts, with their establishment aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 14 on life below water.

The Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR Convention), as an exclusive conservation instrument in the Southern Ocean, has the mandate to deploy appropriate management tools to enhance the resilience of the Southern Ocean. The Commission for the CAMLR Convention (CCAMLR) has been working towards adopting a network of Southern Ocean MPAs since 2002. In 2009, the Commission first committed to adopting a representative network of MPAs to establish a representative network of MPAs by 2012 (CCAMLR, 2009a). In the same year, the Commission adopted the world’s first high seas MPA south of the South Orkney Islands (SOISS), to contribute towards the conservation of marine biodiversity in Subarea 48.2 (CCAMLR, 2009b). In 2011, CCAMLR adopted the General Framework for the Establishment of CCAMLR Marine Protected Areas (the MPA Framework) (CCAMLR, 2011). In 2016, CCAMLR adopted the world’s largest MPA in the Ross Sea Region (RSR) (CCAMLR, 2016a). The designation of RSR MPA is seen as a good example of absorbing Climate Change into CCAMLR’s decision-making processes (Rayfuse, 2018, p.76).

However, the progress of MPA establishment under CCAMLR over the past half-decade has been far from satisfactory. A recent research on existing MPAs reveals that ‘current Antarctic MPAs are not representative of the full range of benthic and pelagic ecoregions’ and more MPAs are needed (Brooks et al., 2020, p.1). Three MPA proposals currently pending, situated respectively in the East Antarctic Planning Domain, Weddell Sea, and Antarctic Peninsula region (Scott, 2021, p.85). Annual CCAMLR meetings have revealed a persistent lack of consensus on adopting new MPAs since 2017, while the review of Research and Monitoring Plans (RMPs) for existing MPAs has also emerged as a contentious arena (CCAMLR, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022; CCAMLR, 2023a). Consequently, the process of MPA establishment in the Southern Ocean appears to have stagnated (Scott, 2021).

Meanwhile, the Agreement on Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJAgreement), adopted in June 2023 after years of negotiations, reached the milestone of 60 state ratifications needed to trigger its entry into force. The BBNJ Agreement applies to ‘area beyond national jurisdiction’(ABNJ) including the vast majority of the Southern Ocean (BBNJ Agreement, preamble and article 2). The establishment of MPAs as an example of area-based management tools falls within the scope of both the BBNJ Agreement and the CAMLR Convention (Scott, 2025, p.19). According to the article 5 of the BBNJ Agreement, it ‘shall be interpreted and applied in a manner that does not undermine relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies and that promotes coherence and coordination with those instruments, frameworks and bodies’ (BBNJAgreement, article 5, paragraph 2). Therefore, the BBNJ Agreement is not supposed to overtake the CAMLR Convention and applies directly to the establishment of MPAs in the Southern Ocean. Nevertheless, these two legal instruments has profound implications to each other. On one hand, the existing practices of Southern Ocean MPAs under the CAMLR Convention have influenced the rule-making during the negotiations of the BBNJ Agreement (Liu, 2024, p.5). On the other, the delicate rules and procedures on area-based management tools in the BBNJ Agreement does to some extent affect future development and management of MPAs under the CAMLR Convention (Nocito and Brooks, 2023, p.5). Particularly, the Conference of Parties (COP) of the BBNJ Agreement ‘[m]ay take decisions on measures compatible with those adopted by relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies, in cooperation and coordination with those instruments, frameworks and bodies’ (BBNJAgreement, article 22, paragraph 1(b)), although this mandate is limited by a recommendation nature when ‘proposed measures fall within the competences of those other organizations’ (BBNJAgreement, article 22, paragraph 1(c)). As existing literature has given emerging attention to the relationship of the CAMLR Convention and the BBNJ Agreement, the taking into effect of the BBNJ Agreement undoubtably adds new momentum to establishing MPAs in the Southern Ocean.

2 Methodology

This article addresses two core research questions: First, what are the underlying structural constraints impeding MPA establishment under CCAMLR? Second, how might this impasse be resolved to advance cooperative progress in Antarctic MPA development?

This article adopts an institutionalist perspective to analyze these two questions, which also distinguishes the article itself from various other literature. Since 1980s, a cluster of research on international cooperation theories emerged. International cooperation theorists argues that prospects for international cooperation depend heavily on the distinct strategic structure of each issue area (Fearon, 1998, p.269). Apart from traditional concerns such as national interests, more structural constraints including transection cost, information gaps and uncertainty are identified as the hinders of international cooperation (Keohane, 2004, p.87 &102; Koremenos, 2005, p.549). Structural constraints here can be understood as ‘limitations or restrictions that are inherent in the structure of international governance on a certain issue’. These are not easily changed and can have a significant impact on the behavior and outcomes within that context. These findings on structural constraints are not exhaustive, as specific structural factors influencing the progress of international cooperation differ on different issues of international negotiations. Nevertheless, the lens of structural constraints has significant implications in the making of international law, and can be used to analyze the difficulties behind cooperation on establishing MPAs, which further benefit solution-finding of the issue.

In addition, some prominent institutionalists including Kenneth W Abbott introduced the concept of ‘legalization’ in early 2000s, which is defined as ‘a particular form of institutionalization characterized by three components: obligation, precision, and delegation’ (Abbott et al., 2000, p.401). This concept indicates that obligation, precision, and delegation are three key dimensions which operationalize the assessment of institutionalization level of international cooperation. This article uses these three criteria as analytical tools for assessing the institutionalization level of MPA developments in the Southern Ocean, which is shown in section 4.

Following a ‘what-why-how’ analytical framework, the article proceeds as follows. It first reviews spatial management negotiations within CCAMLR over the past five years, synthesizing key issues and points of contention. Next, it assesses the institutionalization level of MPA-related deliberations. It then analyses the structural constraints perpetuating the negotiating stalemate. Finally, it puts forward recommendations to facilitate MPA establishment in the Southern Ocean.

3 An update of ongoing MPA discussions under CCAMLR

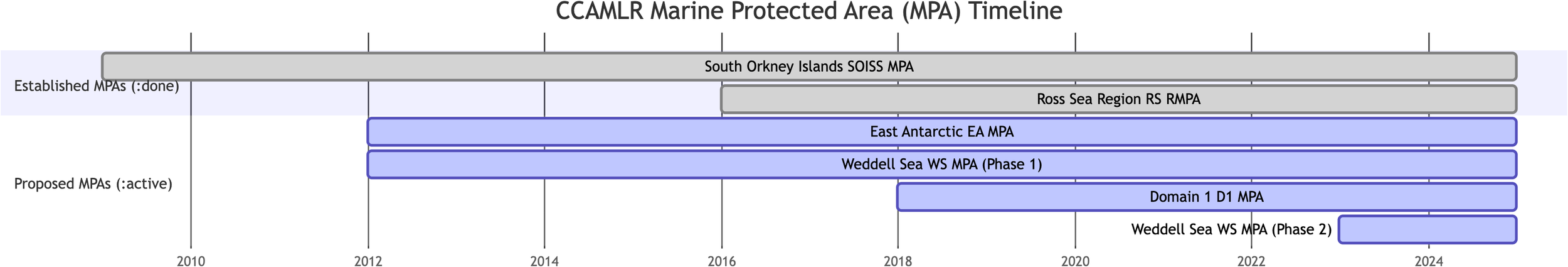

In the Southern Ocean, two vast marine protected areas have to date been established with fairly stringent conservation measures: the South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf MPA (SOISS MPA) and the Ross Sea Region MPA (RSR MPA). Three more proposals are currently under negotiation in the CCAMLR Convention Area, in the East Antarctic, Weddell Sea and Western Antarctic Peninsula respectively. The timeline of these MPA developments is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The timeline of existing MPAs and MPAs in Progress under CCAMLR.

3.1 Debates on the review of existing MPAs

Monitoring and evaluation are keys to the success of MPA networks (Agardy and Staub, 2006; Chircop et al., 2010). Established MPAs will be reviewed in a five year’s frequency, to assess whether specific objectives of the MPAs have been achieved. Two existing MPAs, SOISS MPA and RSR MPA, are both being reviewed.

3.1.1 SOISS MPA

The SOISS MPA, established in 2009 as a first-stage protection zone and updated in 2018, holds the distinction of being the world’s first high-seas MPA, covering 94,000 km² of continental shelf (CCAMLR, 2009b; CM 91-03). In 2009, the UK initiated a MPA proposal on the Southern Shelf of South Orkneys Island and was approved by the CCAMLR in the same year. The objectives of SOISS MPA are ‘to provide a scientific reference area and to conserve important predator foraging areas and representative examples of pelagic and benthic bioregions’.

The SOISS MPA is designated as a General Protection Zone where all commercial fishing is prohibited, apart from some agreed scientific fishing research activities, aligning it with an IUCN Category IV (Habitat/Species Management Area) focused on protecting key ecosystem processes (CCAMLR, 2009c; CCAMLR, CM 91-03; IUCN, 2012). The SOISS MPA was established for an initial 10-year period, requiring a formal review to inform its future management, a structure intended to adapt to new scientific information (CCAMLR, CM 91-03). The map of the SOISS MPA is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

The map of SOISS MPA1.

3.1.2 RSR MPA

The RSR MPA, which entered into force in 2017, is the largest in the world at 2.09 million km², a scale reflecting the vastness of the ecosystem it aims to protect (Brooks et al., 2020). In 2011, the US and Aotearoa New Zealand prepared two separate proposals by for a marine protected area in the Ross Sea. Both proposals were rejected but were later on combined into a joint proposal resubmitted by these two states from 2012 (Nyman, 2018, p.197). It was adopted in 2016 after a compromise of including fishing zones in the proposal (Brooks et al., 2020b). The objectives of the RSR MPA include conserving natural ecological structure, dynamics and function throughout the Ross Sea region at all levels of biological organization, protecting habitats that are important to native mammals, birds, fishes and invertebrates, promoting research and other scientific activities focused on marine living resources and so on.

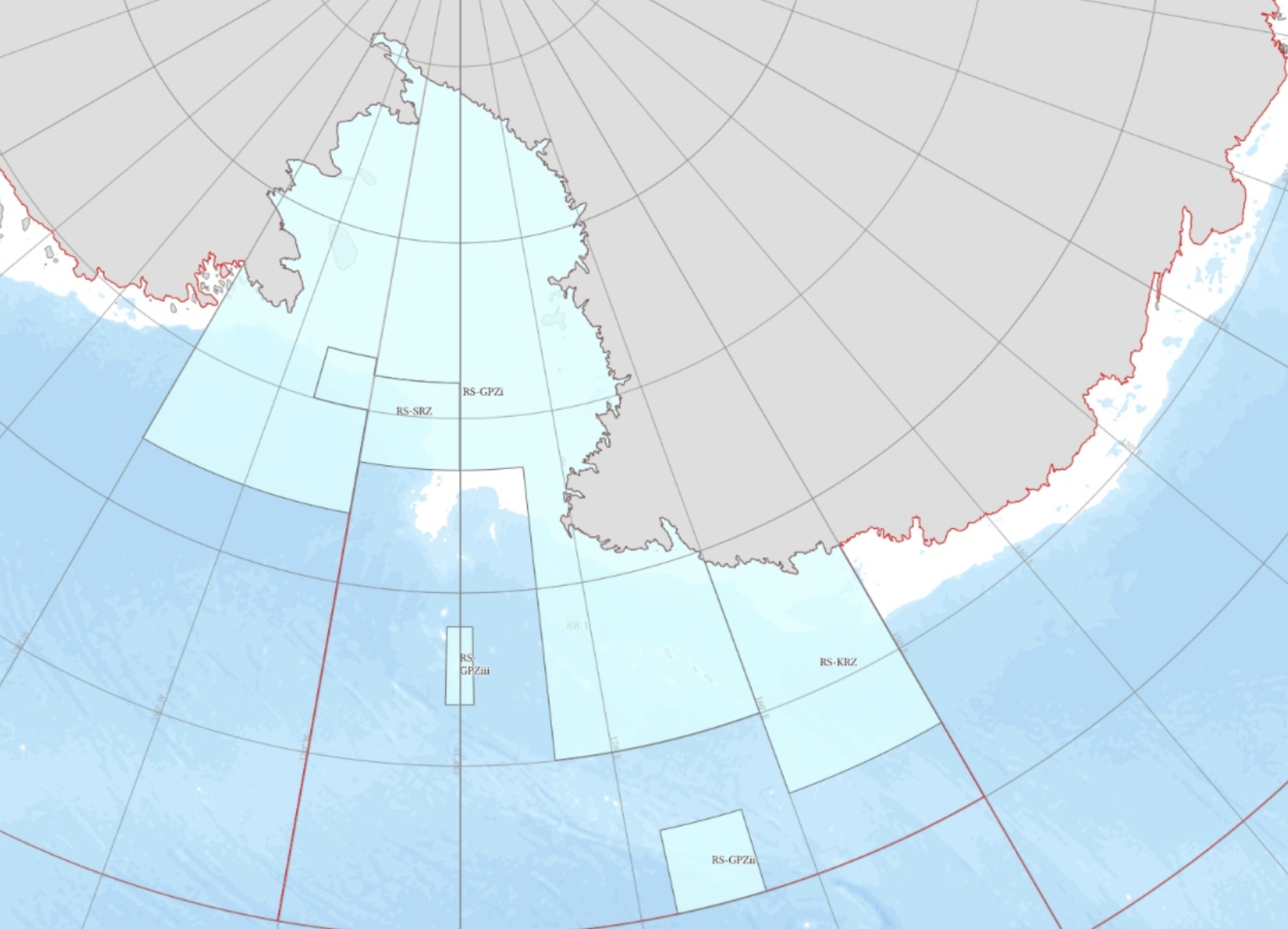

As is shown in Figure 3, the RSR MPA employs a complex zoning plan, featuring a large (1.12 million km2) no-take General Protection Zone (IUCN IV) alongside designated zones where limited research fishing for toothfish (Dissostichus spp.) and krill is permitted, categorizing those areas under IUCN VI (Protected Area with sustainable use) (CCAMLR, CM 91-05, article 5; Brooks et al, 2020). In this zoning plan, each zone has its specific objective and management measures. For example, the Special Research Zone (SRZ) is designed to serve as a scientific reference area to advance research to increase scientific understanding about the ecosystem effects of external forces like fishing and climate change and continue to inform the science-based management of the Ross Sea toothfish fishery. The RSR MPA has a fixed 35-year term with a built-in review process focused on its objectives, but its long-term duration was a point of negotiation and remains a topic of discussion regarding the permanence of conservation (CCAMLR, CM 91-05; Brooks and Ainley, 2022). In 2017, the Scientific Committee endorsed RMP for RSR MPA (SC-CAMLR, 2017).

Figure 3

The map of RSR MPA2.

As is revealed in Table 1, the SOISS MPA and RSRMPA differentiate from each other in many characteristics. Disagreements exist in the review of both MPAs. Majority of the CCAMLR Members believed that both achieved its objectives. Russia and China contended that there was a lack of scientific data to make such conclusion. They argued that relevant Conservation Measures or the RMP should be improved, otherwise the MPA will have no effect due to a failure of renewal (CCAMLR, 2022, para.5.13-5.15).

Table 1

| Characteristic | SOISS MPA | RSR MPA |

|---|---|---|

| Establishment Year | 2009 (As a first-stage MPA); 2018 (Current provisions) | 2016 (Entered into force 2017) |

| Size | 94,000 km² | 2.09 million km² (including a 1.12 million km² no-take zone) |

| Main Ecosystems | Polar shelf ecosystem, sea-ice influenced, benthic habitats | Continental shelf, slope, deep ocean, polynyas, seamounts |

| Flagship Species | Antarctic krill, Adélie penguins, icefish | Antarctic toothfish, Emperor penguins, Antarctic minke whales |

| Main Economic Activities | All fishing activities prohibited (General Protection Zone) | Prohibited: Commercial fishing in the General Protection Zone. Permitted: Limited research fishing for toothfish and krill in designated research zones. |

| Management Plan | CM 91-03 (and its successors) | CM 91-05 (and its successors) |

| Protection Category | IUCN Category IV (Habitat/Species Management Area) | A mix of IUCN Category IV (Habitat/Species Management Area) and Category VI (Protected Area with sustainable use of natural resources) |

| IUCN Alignment | Aligned with IUCN guidelines for marine protection. | Aligned, with specific zones corresponding to different IUCN categories. |

| Duration | Established for an initial period of 10 years, subject to review. | Established for 35 years, with a review process built into the management plan. |

A comparison of the SOISS MPA and RSRMPA.

Apart from the concern for availability of scientific data, Russia and China required clarification of the definition and maintenance of the RMP. There is a consensus that RMPs are scientifically based documents developed to support the future organization and implementation of scientific monitoring and effort (CCAMLR, 2019). But there are a few unclarities in this concept.

First of all, there are different understandings on the relations of RMP and MPAs. Russia proposed that a RMP should be prepared together with MPA proposals (Russia, 2022). It also suggested that the development of an RMP should be prior to MPA establishment (CCAMLR, 2022, para.5.14; CCAMLR, 2023a, para. 5.21). The EU is against such chronological requirement, arguing RMPs are not a precondition for adopting MPAs (CCAMLR, 2019, para.6.45).

Secondly, there are currently no unified criteria for sufficiency of baseline data needed for RMP. To develop an RMP, baseline data is needed, to translate conservation goals or general statements into specific, measurable, achievable, relevant or realistic and time-bound (SMART) management objectives, identify indicators, define states of system or decision triggers, develop management actions in relation to decision triggers. For the standard for the availability of scientific data, Russia holds a sufficient scientific data standard, while the EU, US and some other members only accept best available data (Russia, 2022; CCAMLR, 2022).

Lastly, in terms of who should be responsible for introducing an RMP to the Commission, China believed that the proponent(s) are obliged to develop and introduce an RMP to SC-CAMLR and CCAMLR (China, 2018). While the USA, France, Aotearoa New Zealand and some other CCAMLR members disagreed and believed that it is the responsibility of all members (CCAMLR, 2018).

3.2 Debates on new MPAs adoption

3.2.1 The East Antarctic planning domain

The East Antarctic region is a data-limited region with a paucity of time-series data that can be used to describe the structure and process of the ecosystem. In 2012, Australia, the EU and France proposed to establish EA MPA (Australia, France and the European Union, 2012). The Scientific Committee agreed that the proposal contains the best available science in 2013 (CCAMLR, 2019, para.6.45). Although most members believed that the proposal is ready for adoption Russia and a few states still show reservation towards the proposal. Russia was not satisfied with the quality of the proposal. It raised questions related to the boundaries, goals and objectives of the EA MPA proposal (CCAMLR, 2019, para. 6.42). Also, Russia insisted that the conservation measure for the EAMPA should not be a single one, rather there should be a separate measure for each of the three individual scientific reference zones designated as the EA MPA (CCAMLR, 2021, para.7.14). Moreover, Russia and China are both concerned about the sufficiency of baseline data in the proposal (CCAMLR, 2022, para.5.25; CCAMLR, 2019, para.6.43). In the 42nd CCAMLR meeting in 2023, the proposal got blocked again due to the concern of the status of the best available scientific evidence given climate change influence in the past 10 years (CCAMLR, 2023a, para.5.8). The proponents disagreed with such concern and emphasized CCAMLR’s precautionary and ecosystem-based approach to management, according to which threats did not need to be identified for establishing MPAs (CCAMLR, 2023a, para.5.9).

3.2.2 Weddell Sea MPA

The Weddell Sea region is an ideal study area for research into climate change impacts on Antarctic ecosystems, because there are few human activities undertaken. In 2012, Germany took responsibility for the development of a marine protected area in the Weddell Sea. The WS MPA proposal includes the two phases. Phase 1 of WS MPA is focused on the establishment of an MPA area in Domain 3 and the western parts of Domain 4 and phase 2 will extend the WSMPA across the Domain 4 region. In 2016, the Scientific Committee agreed that the WSMPA Phase 1 proposal was based on best science available and provided a sound basis for MPA planning in the area (CCAMLR, 2016b, para.5.72). The WSMPA Phase 2 proposal was proposed by Norway in the 42nd CCAMLR meeting in 2023 (Norway, 2023).

Russia suggested that proposal for phase 1 include more information on the commercial potential of dominant fish species and krill for future rational use (CCAMLR, 2019, para.6.48; CCAMLR, 2021, para.7.22). Lack the consideration of rational use from the objectives of the proposal was another reason for Russia’s objection (CCAMLR, 2022, para.5.33). China raised issues regarding the availability of baseline data, the proposed protection objectives and measures of the proposal (CCAMLR, 2021, para.7.21). China also put forward concerns about the necessity of this MPA, because the area was less impacted by climate change than other areas, and the fishing activities were managed well and at low level (CCAMLR, 2022, para.5.34).

3.2.3 Antarctic Peninsula Region domain 1 MPA

Domain 1 in Antarctic Peninsula is one of the relatively data-rich regions in the whole CCAMLR Convention Area. It encompasses the area of concern to fur seal populations, which is a critically endangered population and threatened by krill fishing (SC-CAMLR, 2022, paragraphs 3.36, 3.39, 4.11). Therefore, this area is given particular attention in CCAMLR’s spatial management. The preliminary proposal of D1MPA was introduced for discussion during the 2017 meeting of the Scientific Committee. It was submitted by Argentina and Chile and tabled in the CCAMLR Commission since 2018.

It has not been a long time since the submission of the proposal, so substantial comments were given by many parties to improve it. The objections were mainly from Russia. Russia suggested a need for baseline data collection, justifications for the proposed boundaries and duration. More generally, Russia expressed a need for criteria to assess conservation objectives, the development of indicators to assess the effectiveness of the MPA (CCAMLR, 2022, para.5.13). Observing the vastly different opinions about the key aspects of the MPAs, South Africa suggested working on an agreement on a CCAMLR universally acceptable MPA framework (CCAMLR, 2019, para.6.59).

4 Characters of MPAs development under CCAMLR

The negotiations concerning the establishment of MPAs in the CCAMLR Convention Area reveal a complex and uneven evolution across different dimensions of institutionalization. While there is a clear trend towards greater precision in the technical and scientific discourse, this has not been matched by a corresponding increase in legal commitment, and the level of delegation to third-party bodies remains intentionally low.

First, the negotiations demonstrate a growing level of precision, a key hallmark of legal development. The discussions have progressively moved from vague conceptual debates to highly specified technical exchanges. Members now engage in detailed deliberations on the exact scientific requirements for MPA proposals, the specific components of RMPs, and the precise procedures for setting conservation objectives. This shift indicates a maturation of the dialogue, focusing on how MPAs should be implemented rather than whether to implement. Second, the legal obligation to establish MPAs remains weak, situated at the softer end of the international law spectrum. The landmark designation of the RSR MPA in 2016 remains an isolated success; for nearly a decade since, no new binding commitments have been secured. Subsequent pledges, such as the 2021 reaffirmation of the commitment to a representative MPA system, are politically significant but carry no binding legal force, especially as they follow the lapse of the original 2012 target. This creates a paradox where negotiations are technically precise but legally non-binding. Last but not least, the institutional structure of CCAMLR exhibits a low level of delegation. While CCAMLR itself functions as a delegated administrative organization, its members have carefully circumscribed this authority. The Scientific Committee only plays an advisory role. The critical decision-making power—the authority to formally adopt and legally bind states to new MPAs—remains entirely in the hands of the parties. This low level of delegation to institutions for decision-making is a fundamental factor in the slow pace of MPA establishment, as it ensures that political consensus is the sole pathway to creating legally binding obligations.

4.1 A growing level of precision

Precision and elaboration are significant hallmarks in the development international law (Abbott et al., 2000, p.409-413). The MPA discussions under CCAMLR are shifting from using vague language to defining precise concepts and rules. The concerns about the definition of MPAs in the Southern Ocean has been mentioned as an issue by CCAMLR over the years.3 But only recently the specification of the MPA debates increased significantly. The past seven years has seen different views exchanged on ‘the level of scientific information required to establish an MPA, the specifics of RMP components, the procedures for setting the conservation objectives of an MPA and their contents, and the implementation and management of an MPA once it is established’ (CCAMLR, 2023b, para.1.18).

4.1.1 Clarification of principles for MPAs

Opposing parties to the MPA proposals have raised concerns regarding the clarity of objectives and principles governing MPAs in the Southern Ocean, triggering debates over their foundational framework. Notably, several draft MPA proposals have employed the phrase ‘preservation of Antarctic marine life’ as their core objective, deviating from the principles enshrined in Article 2 of the CAMLR Convention. This discrepancy has drawn criticism from China, which emphasizes the importance of ‘rational use’ as a cornerstone of the Convention.

Article 2 of the CAMLR Convention explicitly defines its objective as ‘the conservation of Antarctic marine living resources’, clarifying that ‘conservation’ includes rational use (CAMLR Convention, Article 2). Opponents argue that an overemphasis on ‘preservation of Antarctic marine life’ effectively excludes ‘rational use’, potentially undermining the fishing interests of certain member states. China, in particular, has framed this divergence as inconsistent with CCAMLR’s statutory objectives.

Conversely, proponents of the MPA proposals defend the terminology, citing its alignment with the precautionary approach as a justifiable priority (Jacquet et al., 2016). While consensus on the prioritization of these principles remains elusive, the debate has nonetheless driven the refinement of guiding principles and objectives for MPAs toward greater precision.

4.1.2 Unification of the criteria on designating MPAs

Member states hold divergent perspectives on the criteria for designating MPAs, constituting another contentious debate with significant disagreements. This rift emerged prominently in the context of the EA MPA proposal, where the paucity of scientific data led Russia and China to question both the sufficiency and necessity of the proposed MPA.

At the 42nd CCAMLR Meeting, Russia advocated for revising the ‘best available’ science standard to a ‘sufficient’ science threshold (Russia, 2023). This proposal faced opposition from numerous members, who argued that the ‘best available’ science standard is mandated by the CAMLR Convention and must be upheld (CCAMLR, 2023a, para. 5.33). The Convention explicitly stipulates that conservation measures shall be ‘formulated, adopted and revised on the basis of the best scientific evidence available’ (CAMLR Convention, Article 9.2(f)), a provision also enshrined in the 2011 MPA Framework, rendering challenges to this standard unlikely to gain traction. In its comments on the EA MPA proposal, China put forward a five-element standard (CCAMLR, 2017, para. 6.21). However, the elements outlined in this framework are subject to varying interpretations and require further specification to ensure operational clarity.

Proponents of new MPAs have sought a middle ground by emphasizing a case-by-case approach to MPA designation criteria (CCAMLR, 2021, para. 7.3). Russia, by contrast, has rejected this approach, instead calling for the development of unified criteria applicable across the Convention Area (Russia, 2022). To date, efforts to harmonize MPA designation criteria have yielded minimal progress, underscoring the need for substantial compromise to achieve consensus on this critical issue.

4.1.3 Standardization of management of MPAs

The MPA Framework offers guidance for the development of MPA proposals and their subsequent management. Nevertheless, there remains a need for CCAMLR to establish a single, unified process governing both MPA designation and operational management. This necessity is underscored by the fact that the management of the SOISS MPA has yet to be harmonized with the MPA Framework—after all, the Framework was agreed upon subsequent to the establishment of the SOISS MPA, which was formalized through a Conservation Measure. Furthermore, the MPA Framework itself lacks sufficient procedural and implementation-oriented provisions (CCAMLR, 2022, para. 5.60).

Russia has taken a leading role in advocating for the standardization of MPA management. At the 42nd CCAMLR Meeting in 2023, Russia submitted a draft amendment to the MPA Framework (CCAMLR, 2023a, para. 5.33). This amendment integrated Japan’s proposal to adopt a mandatory MPA checklist, as well as Russia’s own initiative to develop guidelines for the formulation and operation of RMPs, which would be appended to Conservation Measure 91-04 (Japan, 2015; CCAMLR, 2019, para. 6.15). While certain amendments in the draft were not accepted by European members and their U.S. counterparts, these parties demonstrated openness to the proposed changes. This indicates a clear willingness among all member states to pursue a consistent approach to the development and management of MPAs.

4.2 A lack of legal commitment

In international law, legal obligations derive from binding rules or commitments, which manifest in diverse forms across a spectrum ranging from soft law to jus cogens (Chinkin, 1989; International Law Commission, 2022). States’ commitments on international issues vary significantly along a continuum of obligation, spanning from ‘explicit negation of intent to be legally bound’ to ‘unconditional obligation’ (Abbott et al., 2000).

The level of legal commitment regarding Southern Ocean MPAs has remained largely stagnant over the past decade. The designation of the Ross Sea Region MPA in 2016 marked a milestone, demonstrating CCAMLR’s capacity to build consensus and fulfill its commitments. Since then, however, no new binding commitments have been secured. At its 40th annual meeting in 2021, CCAMLR members reaffirmed their commitment to establishing a representative system of MPAs within the Convention Area (CCAMLR, 2021). Notably, this reaffirmation came nearly a decade after the 2012 target for establishing such a system had lapsed, and it carries no binding legal effect.

MPA development is thought as a useful tool to protect Antarctic marine ecosystems against the adverse impacts of climate change (Wilson et al., 2020). Lack of legal commitment to MPA has restrained the ability of the Antarctic marine ecosystems to adapt to the impacts of climate change. There are currently insufficient binding rules and norms in climate change within the Antarctic Treaty System, which further affects the legitimacy of this regime (Stephens, 2018).

In recent years, there has been a growing political willingness among both proponents and opponents to participate in and engage with MPA discussions. At a virtual meeting on 28 April 2021, ministers and high-level officials from 15 CCAMLR member states and the European Union issued a Joint Declaration committing to the designation of Southern Ocean MPAs as soon as possible. This commitment was reiterated at a follow-up virtual meeting on 29 September 2021 and advanced further during the Third Special Meeting of CCAMLR in 2023. While members failed to reach consensus on a roadmap for developing a representative MPA system as initially envisaged, their shared intent holds significance, as no party explicitly dissented from this commitment. China’s stance toward MPAs has also grown more positive, with fewer debates over the necessity of such measures compared to a decade ago.

Despite these developments, no new legal commitments have been formalized to date. Russia and China, while actively participating in debates, remain cautious about developing legally binding instruments. All attempts to establish new binding commitments have encountered obstacles under CCAMLR’s consensus-based decision-making framework.

4.3 A low level of delegation

Delegation is defined as ‘the extent to which states and other actors delegate authority to designated third parties—including courts, arbitrators, and administrative organizations—to implement agreements’ (Abbott et al., 2000, p. 415). In the context of MPA development, a certain degree of delegation is inherent: CCAMLR functions as a pre-existing organization with the mandate to coordinate and mediate negotiations on MPA-related matters. The Commission itself possesses administrative authority to implement agreed-upon binding measures and maintains an independent Scientific Committee tasked with providing advice to the Commission on the adoption of conservation measures and RMPs for MPAs (MPA Framework, Articles 3 and 5).

That said, CCAMLR’s structure, like that of many international regimes, remains relatively decentralized. Its consensus-based decision-making process—enshrined in Article 12 of the CAMLR Convention—results in weak binding constraints on member states. The requirement of consensus is one of the fundamental arrangements in Antarctic Treaty System and dates back to article 12 of the Antarctic Treaty. It reflected the delicate balance of claimant states and non-claimant states in Antarctic decision-making, and assured that no recommendations affecting sovereignty claims can be made without the consent of claimant and non-claimant states (Triggs, 1985, p.208). This agreement was followed by the CANMLR Convention and historically contributed to CCAMLR’s legitimacy and success in developing numerous conservation measures (Everson, 2017, p. 149; Vanstappen, 2019, p. 89). In recent years, however, it has been characterized as the Achilles’ heel of the regime, particularly in the context of MPA designation (Goldsworthy, 2022, p. 433).

The Scientific Committee, for its part, is widely regarded as an independent and reliable body that has helped ensure evidence-based decision-making within CCAMLR (Vanstappen, 2019, p. 89). Despite this, the Committee’s reviews of MPA proposals carry limited weight due to their non-binding nature. This is exemplified by the fact that MPA proposals deemed to ‘reflect the best available science’ in reviews conducted over a decade ago have yet to be approved.

5 Structural constraints underlying the negotiations

The analysis above shows that negotiations on MPAs under CCAMLR are getting more and more rigid. This is understandable because increased precision naturally engenders high negotiating costs (Goldstein et al., 2000, p.398).4 A high level of precision enables states to calculate the future gains and loss. As James D Fearon has revealed, ‘the more states value future benefits, the greater the incentive to bargain hard for a good deal, possibly fostering costly standoffs that impede cooperation (Fearon, 1998, p.296).’ Despite the growing institutionalization in MPA development, there are structural constraints that impede the achievement of a cooperation outcome. These constraints offer a structural explanation on why Russia and China have resistance or hesitance in reviewing existing MPAs and accepting new MPAs.

5.1 Competing national interest

States have extensive yet divergent interests in the vast and bountiful Southern Ocean. The first and foremost concern of interest is competing jurisdiction in the Southern Ocean. Sovereignty is still an unsolved issue which penetrates to each aspects of Antarctic affairs. The establishment of MPAs has an influence on the ‘exclusive jurisdiction’ derived from existing sovereignty claims. Due to the sensitive nature of the sovereignty issues in Antarctica, prospects for reforming the decision-making rule in the near term appear limited.

The second significant concern in MPA development is economical interest. Establishment of MPAs means a shrink of freedom of fishing in the Southern Ocean. Russia and China are both major fishing nations. Russia used to be a major krill fisher in the Antarctic region, accounting for more than 95 percent of the global volume of krill fishing. China is the world’s second largest producer of krill. The establishment of MPA usually entails large no-take area. Even though the CAMLR Commission explained ‘MPAs do not necessarily exclude fishing, research or other human activities’, the main conservation measure in current two MPAs is sanctuary for nearly all types of fishing activities. The natural tendency of protecting its fishing interests and avoiding potential degradation of fishing rights leads Russia and China to be particularly cautious about new MPA proposals. China’s protection for its fishing interests can be seen from repeated expressions of ‘rational use’ in negotiations (Jacquet et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2016). This attitude has been constantly reflected in its Antarctic engagement policy (Liu, 2020, p.4). China’s performance in MPA negotiations is consistent with this position: it was willing to provide constructive feedback to improve proposals in progress, as long as it incorporated a fishing demand. In this sense, China is not against the establishment of MPAs but adopts a two-fold approach, striking a balance between ‘rational use’ and ‘conservation’ (Hong, 2021, p.3).

Another source of political confrontation is the competition on discourse and leadership. For the EU, it perceives the maintenance of its forerunner image and leadership in environmental issues as its key interest (Raspotnik and Østhagen, 2020, p.266). Therefore, it pursues a greater influence over international debate on the establishment of MPAs, which is listed as a separate item in its policy agenda (Liu, 2018, p.867; European Commission, 2009). This can be seen from the fact that existing proposals are all initiated by and under the leadership of the EU and its members. The strong language and pushy words in support of proposed MPAs used by the EU in the negotiations are part of the efforts to advance its interests (Raspotnik and Østhagen, 2020, p.263-265). Academic literature has extensively examined China’s engagement in Antarctic marine conservation from a geopolitical perspective, noting its evolving role from a ‘norm antipreneur’ to a ‘norm entrepreneur’ and its increasingly active participation as a relative latecomer to the Antarctic Treaty System (Liu, 2020, p. 4; Tang, 2017). These shifts suggest potential for China to deepen its engagement and even assume a leadership role in Antarctic governance in the future.

5.2 Scientific, conceptual and managerial uncertainty

Another source of hesitance towards Antarctic marine conservation of Russia and China is from uncertainty. Three types of uncertainty discourage Russia and China. The first one is the uncertainty undying the knowledge of climate change and Antarctica. There are numerous scientific reports demonstrating the adverse impacts of climate change happening globally and in Antarctica. There is a certain degree of certainty on the fact that climate change has inevitably had adverse impacts on Antarctica and its ecosystems (IPCC, 2019, 2021; SCAR, 2022). However, the evidence is collected unevenly, and some parts of Antarctica are poorly still observed. For instance, there is a knowledge gap in communities, habitats and ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries, tourism and climate change in some iced underwater areas (Xavier et al., 2016; Van de Putte et al., 2021). The paucity and patchiness of marine ecology data raised concerns about the sufficiency of scientific evidence. In case of little scientific evidence available, the necessity of establishing MPA becomes a question. As is said by Chinese delegation, ‘MPAs could not address all the threats that climate change poses to Antarctica’s marine ecosystem’.

The second kind of uncertainty is the real intent of the MPA. MPAs should not be established without clear objectives and management measures. The IUCN Report identifies the establishment of clear goals and measurable objectives for the network as essential for guiding management decisions and tracking progress and performance (IUCN, 2008). If there is no consistent standard for MPAs, it will be subject to political manipulation to realize unknown intent of proponents. The intent of MPA proponents, who are mostly claimants of territorial sovereignty, is skeptical for non-claimants such as Russia and China. It is not unreasonable to worry that the MPA will not be used as a way of strengthening presence and enhancing territorial claims (Chen, 2019, p.192). Thus, China wants to understand the real need for the MPA given that many conservation measures are available. For Russia, a mandatory RMP together with MPA proposal is helpful to remove such uncertainty and guarantee acceptable substantial management in the MPA.

The last one is uncertainty about subsequent management of MPAs. MPAs often face criticism for inefficiency due to poor management, lack of monitoring, and insufficient consideration of ecological and social factors (Maestro et al., 2019). The effect of established MPAs should be evaluated with consistent and relatively objective standards and methods. Research has been conducted on the frequently cited indicators used to assess the success of MPA globally (Gallacher et al., 2016). Monitoring MPAs is challenging due to the complexity of marine ecosystem dynamics (Esteban-Cantillo et al., 2025). The monitoring complexities in the Southern Ocean is much higher than that in other parts of the high seas, which means additional difficulty in the management of those MPAs. In the Southern Ocean, the a number of management details including the temporal scale of MPAs are still uncertain. The lasting period of the MPAs links to the evaluation frequency, financial budget, and long-term governance stability, and therefore should be decided with collectively deliberation based on scientific evidence. Moreover, there are no clear rules on the attribution of responsibilities and sharing of costs in managing established MPAs under CCAMLR (Chen, 2019, p.195). For example, it is not clear whether the draft and maintenance of RMP was the responsibility of all CCAMLR members or that of proposers. Moreover, In Russia’s eyes, there are loopholes in current MPA Framework in providing guidance in MPA management. Therefore, Russia required a unified approach for the management of MPAs, to make sure it will operate within a guideline and not go too far beyond its original purpose. Russia showed a low tolerance for such uncertainty by suggesting a suspension of existing MPAs and discussions on new MPA proposals in the Convention Area until the MPA Framework is revised (CCAMLR, 2023b, para.5.31 and 5.44).

5.3 Potential influence of enforcement on Antarctic claims

The ability of enforcement is another concern in the design of international regimes (Koremenos et al., 2001, p.776). Enforcement means the real effect of an agreement. CCAMLR has its own enforcement mechanisms in fishing management. But its effective enforcement in fishing management also relies on active enforcement of state members, including the United States and Antarctic territorial claimants, namely Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia, Chile, Argentina and the United Kingdom. It is possible that after the establishment of MPAs, the claimants will be motivated and justified to enforce fishing restrictions in its own claimed waters. This discourages non-claimant states who has limited capacity to contribute to Southern Ocean enforcement activities as they cannot take the opportunities to enhance their presence and claims (Hong, 2023).

5.4 Forum shopping between international regimes

‘Forum shopping’ originally refers to the practice of choosing the court or jurisdiction that has the most favorable rules or laws for the position being advocated (Ferrari, 2021, p.61). Here it is used to mean the situation where states could pick a favorable regime or political setting to cooperate on MPA issues. MPA and marine conservation for adaptation to climate change are being addressed by many multiple international regimes, including but not limited to the UNCLOS, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (‘UNFCCC’), and the Convention on Biological Diversity (‘CBD’). Considering that CCAMLR is a part of the Antarctic Treaty System where there are only 12 original signatories and limited state members, China and Russia will not be motivated to compromise in MPA establishment under CCAMLR if they believe that they can get a better status in other international regimes.

For example, almost all CCAMLR members have signed the BBNJ Agreement. Therefore, they are obliged to follow the legal norms and principles on MPAs in the BBNJ Agreement. Current practice has shown that claimant states such as UK, Chile and Norway are not willing to place MPA development issues in the Southern Ocean in the platforms under the BBNJ Agreement, which can be seen from the declarations of these states in approving the BBNJ Agreement.5 Other states may not follow such practice and can have different positions in terms of the applicability of the BBNJ Agreement in the Southern Ocean. In this case, CCAMLR members who can find clauses in their favor in the BBNJ Agreement are not likely to compromise in the CCAMLR negotiation process. In other words, CCAMLR members may use the rules in the BBNJ Agreement as a leverage in their negotiations under the CCAMLR. For example, the BBNJ provides a voting mechanism when consensus cannot be achieved in the development of area based managed tools (BBNJ Agreement, article 23). This arrangement was designed to avoid a stagnate in marine protection. If MPA proposals in the Southern Ocean are stuck for a long time, states theoretically have the option to propose such MPAs in the forum under the BBNJ Agreement and approve these proposals by voting. The feasibility of such pathway is subject to the interpretation of ‘not undermine’ provision of the BBNJ Agreement.6 Although the BBNJ Agreement does not create a hierarchy with decision-making authority positioned above other regimes with the ‘not undermine’ provision, the substantial work of CCAMLR on MPA developments would be impacted due to the overlap of jurisdiction over area-based management tools in the Southern Ocean (BBNJ Agreement, article 5). For detailed rules not covered by the BBNJ Agreement yet, states can still decide to voice their standings in one of the two forums whichever maximizes their interests.

Likewise, the UNFCCC framework is another available regime for climate change related negotiations, where a special privilege is given to developing countries through the application of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC). This principle has been emphasized in the recent ITLOS and ICJ advisory opinions on climate change. ITLOS recognized that the CBDR-RC principle enshrined in the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, applies to the law of the sea regime under UNCLOS (ITLOS, 2024, para. 325-326). ICJ also highlighted the importance of this principle in the interpretation of state obligations under international environmental law (ICJ, 2025, para.146). It is natural for developing members of CCAMLR, to seek for advantage and get allies in the negotiations of marine conservation for the climate change. Such a mentality is exemplified in the drafting of the 2023 Helsinki Declaration on Climate Change and the Antarctic in the 45th Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting, when China and Brazil insisted the incorporation of CBDR in the text of the Declaration.7

6 Ways to move forward

The evaluation of institutionalization of MPA developments in the Southern Ocean reveals the intertwining law and politics in Antarctic affairs, which echoes the conclusion of many other works on this theme. The mission of the ‘institutionalization’ academy is not only to explain but also to find a way forward to achieve a higher level of cooperation by dealing with the constraints. Taking all constraints and politics into account, some practical ways forward towards a representative MPA network in the Southern Ocean are provided.

6.1 Reduction of triple uncertainty

After exchanging different views on existing MPA review and new MPA proposals, the discussion is getting more precise and specific. Now that the opponents’ claims are clearer, a further removal of scientific and conceptual uncertainty helps to achieve substantial progress on MPA development. Enhancing scientific supporting materials is helpful to reduce scientific uncertainty on climate change and its impacts in the Southern Ocean. More scientific research on the impacts of climate change on the Southern Ocean should be encouraged.

But even if the science part meets the standards of CCAMLR’s best available science and even exceeds it, it is not sufficient to attain consensus (Sylvester and Brooks, 2020, p.10). To ease the conceptual uncertainty, a practical method was put forward in the third special meeting of the CCAMLR. The meeting agreed on a step-by-step approach. Based on this approach China suggested a three-step plan as the way forward for CCAMLR’s MPA process: First, the Commission modifies the MPA Framework. Second, the proponents amend their MPA proposals and improve supporting materials accordingly. Third, the Scientific Committee and the Commission review the amended MPA proposals and supporting materials (CCAMLR, 2023b, para 2.1). Russia proposed four additional annexes for the MPA Framework in the same meeting.8 This is a useful specification to build consensus and a good practice of reducing uncertainty. Walking down this path, by unpacking and addressing different views one by one or in bundle, it will lead to the adoption of MPAs as the proponents and supporters wanted at the end. This journey will be arduous, but a middle point can always be found.

As for the managerial uncertainty, the CCAMLR could learn from the management and systematic review process of Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASMAs) and Antarctic Specially Managed Areas (ASPAs) under the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (‘the Environmental Protocol’) by the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting. In accordance with the Protocol, parties are subject to stringent reporting obligations. Article 17 of the Environmental Protocol establishes an annual reporting duty on implementation, which is elaborated in Annex V for MPAs. Key requirements include:

Collecting and exchanging data on permits, visits, and any significant environmental damage.

Annually disclosing the number and nature of permits issued.

Providing summaries of all research and activities conducted.

Reporting annually on implementation measures, such as site inspections, and any corrective actions taken to address contrav entions of ASPA or ASMA Management Plans.

In the management of ASPA and ASMA, the obligations and responsibilities of reporting and reviewing equally and clearly fall on the shoulders of each consultative party so that no privileges can be claimed by the proposers. Clarification on this helpS CCAMLR to proceed in the review and management of existing MPAs.

6.2 The deployment of a neutral enforcement mechanism

Progress in negotiations is likely to accelerate if concerns regarding enforcement are effectively addressed. To forge consensus, the interests of all member states—whether claimants or non-claimants, developing or developed—must be adequately accommodated. Critical to this is respect for the delicate balance enshrined in Article 4 of the Antarctic Treaty, which mandates that the subsequent enforcement of MPA measures should not inadvertently grant claimant states undue advantages or operational conveniences within their claimed marine areas.

Conversely, introducing moderate enforcement leniency for less capable member states could serve as a meaningful incentive. The enforcement mechanism for MPAs should thus be grounded in principles of global equity and tailored to the respective capacities of states, explicitly acknowledging the constraints faced by developing countries with limited enforcement capabilities.

Considering the importance of decision-making in the establishment of new rules on MPAs, reform proposals have been proposed to adjust the consensus based decision-making under CCAMLR. For example, Yelena Yermakova proposed linking the decision-making power of the ATCPs to a country’s domestic emission reduction policies, arguing that only nations genuinely committed to climate change obligations should qualify as decision-makers in Antarctic affairs (Yermakova, 2021, p. 355). While the perspective of Yelena Yermakova has merit, her proposal is relatively radical and could potentially jeopardize the stability of the ATS. It is argued here that linking the decision-making power with a good climate obligation compliance in Antarctica might be a good direction to converging efforts on moving forward. This idea could attract the member states because it only requires a fulfillment of climate obligations in Antarctica, instead of that in their domestic territories. For instance, the compliance of a state party on climate mitigation or Environment Impact Accessment in Antarctica can be considered in reevaluating its decision-making power under CCAMLR.

6.3 Interaction with external international regimes

The goal of a representative MPA system in the Southern Ocean needs to be realized for the long-term effectiveness and legitimacy of CCAMLR in the era of climate change. Just as Rosemary Rayfuse argued, the overarching issue of climate change ‘requires a level of cooperation and coordination between existing regimes and regimes which currently [do] not exist’ (Rayfuse, 2012). Therefore, the rules for the MPAs in the Antarctic should be harmonized with those in the UNCLOS, UNFCCC, CBD, BBNJ Agreement and so on. In fact, coordination between CCAMLR’s conservation measures and other relevant institutions and mechanisms has been addressed through various provisions in the CAMLR Convention. For example, Article XXIII of the Convention requests that the Commission cooperate with the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and other specialized UN agencies, and that it seek to develop cooperative working relationships with inter-governmental and non-governmental organizations which could contribute to its work, including the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research, the International Whaling Commission and industry bodies.

Under such requirement, all CCAMLR members are supposed to navigate themselves in different projects of global governance as well as stay in the same page. For example, while setting guiding principles for MPA, the principles in these external regimes should be substantially considered. The dialogue among environmental regimes has been seen as a driver of consensus-based decision-making (Sykora-Bodie and Morrison, 2019, p.2154). It helps to build consensus and avoid ‘forum shopping’ of state parties. Therefore, CCAMLR should be sustain a close interaction with external environmental and conservation regimes. First of all, the rules and criteria on the designation of MPAs in the BBNJ Agreement provides a reference for that in the Southern Ocean. Secondly, CCAMLR members should keep participating and communicating in the meeting of the UNFCCC to build more common understanding on the demand of climate change governance and MPA establishment. The interaction with the UNFCCC also helps the incorporation of climate justice in the management of Southern Ocean MPA system. Lastly, the conceptual framework development and further precision of MPA can refer to the original function and motivation of ‘protected area’ in early discussions held by the CBD. The ongoing conservation goal management under the CBD framework also provides momentum for the marine conservation in the Antarctic.

7 Conclusions

Over the past decade, political negotiations on the establishment of MPAs in the Southern Ocean have reached an impasse. Yet beneath this broadly disappointing landscape, incremental progress toward greater precision in the Southern Ocean MPA regime should be recognized. After a close look at the debates on the management of existing MPAs and developments of new MPAs, it finds an urgent need for CCAMLR to accommodate competing interests, refine MPA definitions, harmonize criteria, deliberate on enforcement mechanisms, and align itself with international regimes relating to spatial protection of marine ecosystems. It also calls for more attention to leading debates in this regard from both policy makers and researchers.

Political barriers represent the primary obstacle to CCAMLR’s progress on MPA issues, and the positions of the two key actors often cited as sources of contention—China and Russia—require nuanced differentiation. While China is seen as an emerging active player in CCAMLR, academic understanding of Russia’s political motivations in this domain remains limited. Russia’s persistent opposition and reluctance to compromise have been interpreted as indicators of power politics, with its use of veto power functioning as a bargaining tool to safeguard national interests (Chen, 2021). A fuller comprehension of its stance, however, requires contextualization within broader Antarctic and international political dynamics (Goldsworthy, 2022, p. 432). Beyond the pursuit of national interests, additional structural constraints encompass scientific, conceptual and managerial uncertainty, caution regarding enforcement mechanisms, and competition between overlapping regulatory regimes. Minimizing the effects of these constraints is the focus of the work of CCAMLR in the near future. CCAMLR could pursue several strategic pathways to advance progress. Mitigating uncertainty in future management frameworks, introducing incentive structures for MPA enforcement, and enhancing interaction with external international regimes would help alleviate structural constraints. Such measures are critical to advancing MPA establishment in the Antarctic—a priority made increasingly urgent by the realities of global climate change.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

MY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WQ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We want to thank China Scholarship Council and Macquarie University for co-funding MY’s cotutelle PhD program, which no doubt helped the accomplishment of this work. We bear full responsibility for any errors by our own.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^Source of figure: CCAMLR website. Available online at: https://cmir.ccamlr.org/node/2.

2.^Source of figure: CCAMLR website. Available online at: https://cmir.ccamlr.org/node/1.

3.^Russia reiterated this issue in its comments on MPA proposals, see CCAMLR (2019), Report of the 38th CAMLR meeting, paragraph 6.15; China also suggested an elaboration of definition of an MPA by the CCAMLR Commission, see CCAMLR (2021), Report of the 40th CCAMLR meeting, paragraph 7.1.

4.^Goldstein Judith, Miles Kahler, Robert O. Keohane, and Anne-Marie Slaughter. Introduction: Legalization and World Politics, (2000) 54:3 International Organization 85-399, at 398.

5.^For example, UK declares that ‘the Antarctic Treaty system comprehensively addresses the legal, political and environmental considerations unique to that region and provides a comprehensive framework for the international management of the Antarctic’. Chile declares that ‘the Agreement shall in no way undermine the legal regimes to which Chile is a party, such as, among others, the Antarctic Treaty and its related instruments in force (theConvention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals, and the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty and its annexes’. Another example is the declaration made by Norway, emphasizing the specific obligations in the BBNJ Agreement to respect the competences of, and not undermine instruments, frameworks and bodies including the Antarctic Treaty System. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/PAGES/ViewDetails.aspx?chapter=21&clang=_en&mtdsg_no=XXI-10&src=TREATY (last visited on 25 October 2025).

6.^Article 5, paragraph 2 of the BBNJ Agreement provides that ‘this Agreement shall be interpreted and applied in a manner that does not undermine relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies and that promotes coherence and coordination with those instruments, frameworks and bodies.’

7.^The final text of the Helsinki Declaration on Climate Change and the Antarctic did not include CBDR explicitly, but used the wording ‘recognising the objectives and principles of the UNFCCC and the on-going work to tackle climate change…’.

8.^Four annexes include: legal management aspects of MPAs in the Convention Area; benchmark checklist to regulate the unified process for the establishment and operation of MPAs in the CCAMLR area; MPA management plan and MPA RMP.

References

1

Abbott K. W. Keohane R. O. Moravcsik A. Slaughter A.-M. Snidal D. (2000). The concept of legalization. Int. Organ54, 401–419. doi: 10.1162/002081800551271

2

Agardy T. Staub F. (2006). “ Synthesis: Marine Protected Areas and MPA Networks,” in Module of the Network of Conservation Educators & Practitioners (NCEP). (IW: LEARN). Available online at: https://iwlearn.net/documents/28503 (Accessed November 25, 2025).

3

Australia, France and the European Union (2012). Proposal for a conservation measure establishing a representative system of marine protected areas in the East Antarctica planning domain. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/ccamlr-xxxi/36 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

4

Brooks C. M. Ainley D. G. (2022). A summary of United States research and monitoring in support of the Ross Sea region marine protected area. Diversity14. doi: 10.3390/d14060447

5

Brooks C. M. Chown S. L. Douglass L. L. Raymond B. P. Shaw J. D. Sylvester Z. T. et al . (2020). Progress towards a representative network of Southern Ocean protected areas. PloS One15, e0231361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231361

6

Brooks C. M. Crowder L. B. Österblom H. Strong A. L. (2020b). Reaching consensus for conserving the global commons: The case of the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Conserv. Lett.13. doi: 10.1111/conl.12676

7

Cavanagh R. D. Melbourne-Thomas J. Grant S. M. Barnes D. K. A. Hughes K. A. Halfter S. et al . (2021). Future risk for Southern Ocean ecosystem services under climate change. Front. Mar. Sci.7, 615214. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.615214

8

CCAMLR (2009a). Fulfilling CCAMLR’s commitment to create a representative system of Marine Protected Areas. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/ccamlr-xxxvii/bg/36 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

9

CCAMLR (2009b). Twenty-eighth Meeting of the Commission, Meeting Report. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/system/files/e-cc-xxviii.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2025).

10

CCAMLR (2009c). Protection of the South Orkney Islands southern shelf. Conservation Measure 91-03. Available online at: https://cm.ccamlr.org/en/measure-91-03-2009 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

11

CCAMLR (2011). Conservation Measure 91–04. Available online at: https://cm.ccamlr.org/en/measure-91-04-2011 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

12

CCAMLR (2016a). Conservation Measure 91–05. Available online at: https://cm.ccamlr.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/91-05-2016.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2025).

13

CCAMLR (2016b). Report of the 35th CCAMLR meeting. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/system/files/e-cc-xxxv_0.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2025).

14

CCAMLR (2017). Report of the 36th CCAMLR meeting. Available online at: https://documents.ats.aq/atcm36/fr/atcm36_fr001_e.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2025).

15

CCAMLR (2018). Report of the 37th CCAMLR meeting. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/ccamlr-xxxvii (Accessed October 29, 2025).

16

CCAMLR (2019). Report of the 38th CCAMLR meeting. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/system/files/e-cc-38_0.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2025).

17

CCAMLR (2021). Report of the 40th CCAMLR meeting. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/system/files/e-cc-40-rep.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2025).

18

CCAMLR (2022). Report of the 41st CCAMLR meeting. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org (Accessed October 29, 2025).

19

CCAMLR (2023a). Report of the 42nd CCAMLR meeting. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org (Accessed October 29, 2025).

20

CCAMLR (2023b). Report of the Third Special Meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org (Accessed October 29, 2025).

21

Chen J. (2019). “ China’s Role in Antarctic Marine Conservation,” in Chinese Research Perspectives on the Environment (London: Dialogue Earth) vol. 9. , 187–199.

22

Chen J. (2021). Controversy over Russian vessel in Antarctica reveals CCAMLR shortcomings. China Dialogue Ocean. (London: Dialogue Earth). Available online at: https://dialogue.earth/en/ocean/15935-controversy-over-russian-vessel-in-antarctica-reveals-ccamlr-shortcomings/ (Accessed October 29, 2025).

23

China (2018). The development of Research and Monitoring Plan for CCAMLR MPAs. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/ccamlr-xxxvii/32 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

24

Chinkin C. M. (1989). The challenge of soft law: development and change in international law. Int. Comp. Law Q38, 850–866. doi: 10.1093/iclqaj/38.4.850

25

Chircop A. Francis J. Van Der Elst R. Pacule H. Guerreiro J. Grilo C. et al . (2010). Governance of marine protected areas in East Africa: a comparative study of Mozambique, South Africa, and Tanzania. Ocean Dev. Int. Law41, 1–33. doi: 10.1080/00908320903285398

26

Esteban-Cantillo O. J. Abreu A. Bourgeois-Gironde S. Wanek E. Gurchani U. Eveillard D. et al . (2025). Six key policy recommendations to advocate for marine conservation that matches the ocean’s dynamism. npj Ocean Sustainability4, 50.

27

European Commission (2009). International dimension of the EU’s Integrated Maritime Policy. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/memo_09_453/MEMO_09_453_EN.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2025).

28

Everson I. (2017). Designation and management of large-scale MPAs drawing on the experiences of CCAMLR. Fish Fish18, 145–159. doi: 10.1111/faf.12137

29

Fearon J. D. (1998). Bargaining, enforcement, and international cooperation. Int. Organ52, 269–305. doi: 10.1162/002081898753162820

30

Ferrari F. (2021). “ Forum shopping: what, why, why not?,” in Forum Shopping Despite Unification of Law (Leiden: Brill) 60–116.

31

Gallacher J. Simmonds N. Fellowes H. Brown N. Gill N. Clark W. et al . (2016). Evaluating the success of a marine protected area: A systematic review approach. J. Environ. Manage.183, 280–293.

32

Goldstein J. Kahler M. Keohane R. O. Slaughter A.-M. (2000). Introduction: Legalization and world politics. Int. Organ54, 385–399. doi: 10.1162/002081800551262

33

Goldsworthy L. (2022). Consensus decision-making in CCAMLR: Achilles’ heel or fundamental to its success? Int. Environ. Agreem22, 411–437. doi: 10.1007/s10784-021-09561-4

34

Hong N. (2021). China and the Antarctic: Presence, policy, perception, and public diplomacy. Mar. Policy134, 104779. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104779

35

Hong N. (2023). Why China is hesitant about endorsing marine protected area proposals in the Antarctic. Available online at: https://Chinaus-icas.org/research/why-China-is-hesitant-about-endorsing-marine-protected-area-proposals-in-the-antarctic/ (Accessed October 29, 2025).

36

ICJ (2025). Advisory opinion on obligations of states in respect of climate change. (The Hague: International Court of Justice). Available online at: https://www.icj-cij.org/case/187/advisory-opinions (Accessed November 25, 2025).

37

ILC (2022). Draft conclusions on identification and legal consequences of peremptory norms of general international law (jus cogens) (New York: International Law Commission).

38

IPCC (2019). “ Technical summary,” in IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Eds. PörtnerH.-O.RobertsD. C.Masson-DelmotteV.ZhaiP.TignorM.PoloczanskaE.et al. (Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press), 39–76. doi: 10.1017/9781009157964.002

39

IPCC (2021). “ Technical summary,” in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Eds. Masson-DelmotteV.ZhaiP.PiraniA.ConnorsS. L.PéanC.BergerS.et al (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 33–144.

40

ITLOS (2024). Advisory opinion on climate change and international law. (Hamburg: International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea). Available online at: https://www.itlos.org/fileadmin/itlos/documents/cases/31/Advisory_Opinion/C31_Adv_Op_21.05.2024_orig.pdf (Accessed November 25, 2025).

41

IUCN (2008). Establishing Resilient Marine Protected Area Networks – Making It Happen. (Washington, DC: IUCN-WCPA, NOAA and The Nature Conservancy).

42

IUCN (2012). When is a Marine Protected Area really a Marine Protected Area. Available online at: https://iucn.org/content/when-a-marine-protected-areareally-a-marine-protected-area (Accessed November 24, 2025).

43

Jacquet J. Blood-Patterson E. Brooks C. Ainley D. (2016). ‘Rational use’ in Antarctic waters. Mar. Policy63, 28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.09.031

44

Japan (2015). Updated MPA Checklist Proposal. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/ccamlr-xxxiv/19 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

45

Keohane R. O. (2004). After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

46

Koremenos B. Lipson C. Snidal D. (2001). The rational design of international institutions. Int. Organ55, 761–799. doi: 10.1162/002081801317193592

47

Koremenos B. (2005). Contracting around international uncertainty. American Political Science Review99, 549–565.

48

Liu N. (2018). The European Union and the establishment of marine protected areas in Antarctica. Int. Environ. Agreem18, 861–874. doi: 10.1007/s10784-018-9419-8

49

Liu N. (2020). The rise of China and conservation of marine living resources in the polar regions. Mar. Policy121, 104181. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104181

50

Liu N. (2024). Establishing marine protected areas in the southern ocean, lessons for the BBNJ agreement. Mar. Policy165, 106216. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106216

51

Maestro M. Pérez-Cayeiro M. L. Chica-Ruiz J. A. Reyes H. (2019). Marine protected areas in the 21st century: current situation and trends. Ocean Coast. Manag171, 28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.01.008

52

Murphy E. J. Johnston N. M. Hofmann E. E. Phillips R. A. Jackson J. A. Constable A. J. et al . (2021). Global connectivity of Southern Ocean ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Evol.9, 624451. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.624451

53

Nocito E. S. Brooks C. M. (2023). The influence of Antarctic governance on marine protected areas in the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Agreement negotiations. NPJ Ocean Sustain2, 13. doi: 10.1038/s44183-023-00019-5

54

Norway (2023). A proposal for the establishment of a Weddell Sea Marine Protected Area – Phase 2. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/ccamlr-42/01-rev-2 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

55

Nyman E. (2018). Protecting the poles: Marine living resource conservation approaches in the Arctic and Antarctic. Ocean Coast. Manag151, 193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.11.006

56

Raspotnik A. Østhagen A. (2020). The EU in Antarctica: an emerging area of interest, or playing to the (environmental) gallery?. Eur. Foreign Aff. Rev.25 (2).

57

Rayfuse R. (2012). “ Climate change and the law of the sea,” in International Law in the Era of Climate Change. Eds. RayfuseR. G.ScotS. V. ( Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham), 147–174.

58

Rayfuse R. (2018). Climate change and Antarctic fisheries: ecosystem management in CCAMLR. Ecol. Law Q45, 53–82.

59

Rogers A. D. Frinault B. A. V. Barnes D. K. A. Bindoff N. L. Downie R. Ducklow H. W. et al . (2020). Antarctic futures: an assessment of climate-driven changes in ecosystem structure, function, and service provisioning in the Southern Ocean. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci.12, 7.1–7.34. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010419-011028

60

Russia (2022). Comments and Proposals Regarding the Development of MPAs for Spatial Management in the CCAMLR Convention Area, SC-CAMLR-XXXVII/18, CCAMLR-41/41. Available online at https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/ccamlr-41/41 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

61

Russia (2023). Draft amendment to Conservation Measures CM 91-04 (2011) General Framework for the establishment of CCAMLR Marine Protected Areas. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/ccamlr-42/28 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

62

SCAR (2022). Antarctic Climate Change and the Environment: A Decadal Synopsis and Recommendations for Action (Cambridge: Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research).

63

SC-CAMLR (2017). The Ross Sea region Marine Protected Area Research and Monitoring Plan. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/sc-camlr-xxxvi/20 (Accessed October 29, 2025).

64

SC-CAMLR . (2022). Report of the Forty-First Meeting of the Scientific Committee. Available online at: https://meetings.ccamlr.org/system/files/meetingreports/e-sc-41-rep.pdf.

65

Scott K. N. (2021). MPAs in the Southern Ocean under CCAMLR: implementing SDG 14.5. Korean J. Int. Comp. Law9, 84–107. doi: 10.1163/22134484-12340147

66

Scott K. N. (2025). Cold cooperation: Reconciling the biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction agreement and the Antarctic Treaty system. International & Comparative Law Quarterly , 1–32.

67

Smith D. McGee J. Jabour J. (2016). Marine protected areas: a spark for contestation over ‘rational use’ of Antarctic marine living resources in the Southern Ocean? Aust. J. Marit. Ocean Aff8, 180–198. doi: 10.1080/18366503.2016.1229398

68

Stephens T. (2018). The antarctic treaty system and the anthropocene. Polar J.8, 29–43. doi: 10.1080/2154896X.2018.1468630

69

Sykora-Bodie S. T. Morrison T. H. (2019). Drivers of consensus-based decision-making in international environmental regimes: Lessons from the Southern Ocean. Aquat. Conserv.29, 2147–2161.

70

Sylvester Z. T. Brooks C. M. (2020). Protecting Antarctica through co-production of actionable science: Lessons from the CCAMLR marine protected area process. Mar. Policy111, 103720. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103720

71

Tang J. (2017). China’s engagement in the establishment of marine protected areas in the Southern Ocean: From reactive to active. Mar. Policy75, 68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.10.010

72

Tittensor D. P. Beger M. Boerder K. Boyce D. G. Cavanagh R. D. Cosandey-Godin A. et al . (2019). Integrating climate adaptation and biodiversity conservation in the global ocean. Sci. Adv.5, eaay9969. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay9969

73

Triggs G. (1985). The Antarctic Treaty Regime: Workable Compromise or Purgatory of Ambiguity. Case West. Reserve J. Int. Law. 17, 195–228.

74

Van de Putte A. P. Griffiths H. J. Brooks C. Bricher P. Sweetlove M. Halfter S. et al . (2021). From data to marine ecosystem assessments of the Southern Ocean: achievements, challenges, and lessons for the future. Frontiers in Marine Science8, 637063.

75