Abstract

The sustainable supply of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LC-PUFA) remains a major challenge for global aquaculture. Although plant oils, microalgae, genetically modified crops, insects, krill, and fish by-products have been explored as alternative sources, none currently provides a stand-alone solution for meeting the growing demand of n-3 LC-PUFA in aquafeeds’ production. Here, we present marine gammarids as a potential complementary source of these fatty acids. Our Perspective article focuses on the nutritional attributes of marine gammarids, including their naturally high levels of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and considers their biological traits that support aquaculture practicality. We also examine the potential of marine gammarids for circular bioeconomy applications through trophic upgrading of low-value side streams. While evidence from feeding trials is limited, preliminary data suggest marine gammarids may maintain their high EPA and DHA content even when fed on low-quality diets. Critical research priorities include developing scalable production systems, optimising feed formulations, evaluating performance across key aquaculture species, and assessing ecological and operational feasibility. This Perspective also highlights the potential of marine gammarids to contribute to a diversified and resilient aquafeed portfolio. Although they are unlikely to replace fish meal or fish oil entirely, marine gammarids may serve as a strategic complementary ingredient.

1 Introduction

The global supply of n-3 long-chain-polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LC-PUFA), particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3), remains insufficient to meet their increasing demand. This persistent shortfall has been widely recognised as a critical global issue with significant implications (Glencross et al., 2024). EPA and DHA are essential nutrients for human and animal health, supporting neural development and offering protection against diverse chronic diseases (Kerdiles et al., 2017). Although some fish species can synthesise n-3 LC-PUFA endogenously, their capacity is limited and generally inadequate, particularly in marine carnivorous species; therefore, dietary supplementation remains necessary (Izquierdo, 2005; Tocher, 2015).

Historically, wild fisheries have been the primary source of n-3 LC-PUFA for human consumption. However, with most global fish stocks now fully exploited or overexploited, capture fisheries are insufficient to meet current and future demand (FAO, 2024). Aquaculture, now exceeding capture fisheries in total production, is increasingly relied upon to provide high-quality protein and lipids (FAO, 2024). Despite advances, with modern grow-out diets for marine fish now include less than 10% FM and approximately 5% FO, aquafeeds still depend heavily on wild fish stocks, using most of the world’s fish meal (FM) and fish oil (FO). Although FM and FO inclusion levels have declined markedly in recent decades, they remain the most concentrated and reliable natural sources of EPA and DHA, and replacing them sustainably continues to pose significant challenges. Nevertheless, aquafeed production still depends heavily on wild fish stocks, consuming approximately 87% and 74% of the global fish meal (FM) and fish oil (FO) output, respectively (Glencross et al., 2023, 2024).

The shift toward plant-based ingredients has reduced reliance on marine resources. However, it introduced new nutritional limitations. Plant meals and oils generally contain little or no EPA or DHA and often have high n-6/n-3 ratios, which can impair fish health and fillet quality. Additional n-3 LC-PUFA sources, including insect meals, microbial biomass, and marine by-products, have been explored, but cost-efficient, scalable ingredients with EPA and DHA profiles comparable to FM and FO remain scarce.

This Perspective examines marine gammarids as an underexplored and potentially complementary ingredient, positioning them among other emerging n-3 LC-PUFA sources and identifying key knowledge gaps and research opportunities.

2 Diversification of n-3 LC-PUFA sources

Developing additional sources of n-3 fatty acids to supplement or replace FM and FO has broadened the aquafeed ingredient basket. These innovations have helped reduce dependence on finite marine inputs. However, no single alternative currently provides a scalable and stable stand-alone solution for supplying n-3 LC-PUFA to global aquaculture.

Plant-derived meals and oils are widely used due to availability and cost, but they contain negligible EPA and DHA and are typically rich in n-6 fatty acids. This imbalance may impair growth and immune function, limiting their ability to meet the n-3 LC-PUFA requirements of most farmed marine species. As a result, their role remains largely supportive rather than substitutive (Tocher, 2015).

Microbial sources, particularly single-cell organisms such as microalgae, represent a promising route for sustainable production of n-3 LC-PUFA. These organisms can synthesise EPA and DHA de novo, and their use has expanded in recent years. However, large-scale application is restricted by high production costs associated with cultivation, energy use, and biomass stabilisation. Although potent in n-3 LC-PUFA content, reaching 58% of n-3 LC-PUFA (Glencross et al., 2024), their cost profile currently limits widespread adoption (Tocher et al., 2019).

Genetically modified (GM) oilseed crops engineered to produce EPA and/or DHA offer a scalable land-based option. Oils from crops such as Camelina or Canola have demonstrated promising DHA and EPA levels (DHA reaching up to 12% and EPA to 24%) and good tissue incorporation in feeding trials (Sprague et al., 2017). However, broader adoption remains constrained by regulatory and consumer acceptance barriers, particularly in Europe. Additionally, differences in lipid form may influence bioavailability, creating further uncertainty regarding their full equivalency to marine-derived oils (Tocher et al., 2019).

Insects, particularly the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens), are increasingly explored for circular aquafeeds due to their ability to convert organic waste into protein-rich biomass (Barroso et al., 2014). However, their lipids predominantly contain saturated and n-6 fatty acids, and EPA/DHA levels remain minimal unless marine substrates are added to their diet. This dependence on marine inputs limits their contribution to reducing FO reliance (Hossain et al., 2023).

Several marine-origin alternatives have also received attention. Krill (Euphausia superba) provides a high-quality phospholipid-rich source of EPA and DHA, reaching up to 34% of total fatty acids (BioMarine, 2022; Glencross et al., 2024). However, it raises ecological concerns due to its central role in polar food webs (Cavan et al., 2019). Similarly, fish by-products can offer a valuable LC-PUFA source, providing up to 14% of these fatty acids for instance in salmon by-products (Glencross et al., 2024; Monteiro et al., 2024); yet their availability and nutritional consistency vary geographically and seasonally. These limitations reduce their predictability and broader applicability.

In comparison, marine gammarids may offer a unique combination of moderately high n-3 LC-PUFA content, adaptability, and potential for circular production, warranting closer evaluation as part of a diversified raw-material portfolio.

3 Nutritional potential of marine gammarids as n-3 LC-PUFA source

Marine gammarids are small peracarid crustaceans occupying intermediate trophic levels in marine and estuarine food webs. Their ecological role, combined with favourable biochemical and biological traits, positions them as promising candidates for aquafeed development (Ahyong, 2020). Moreover, certain species have shown potential to contribute to closing the n-3 LC-PUFA supply gap in aquafeeds.

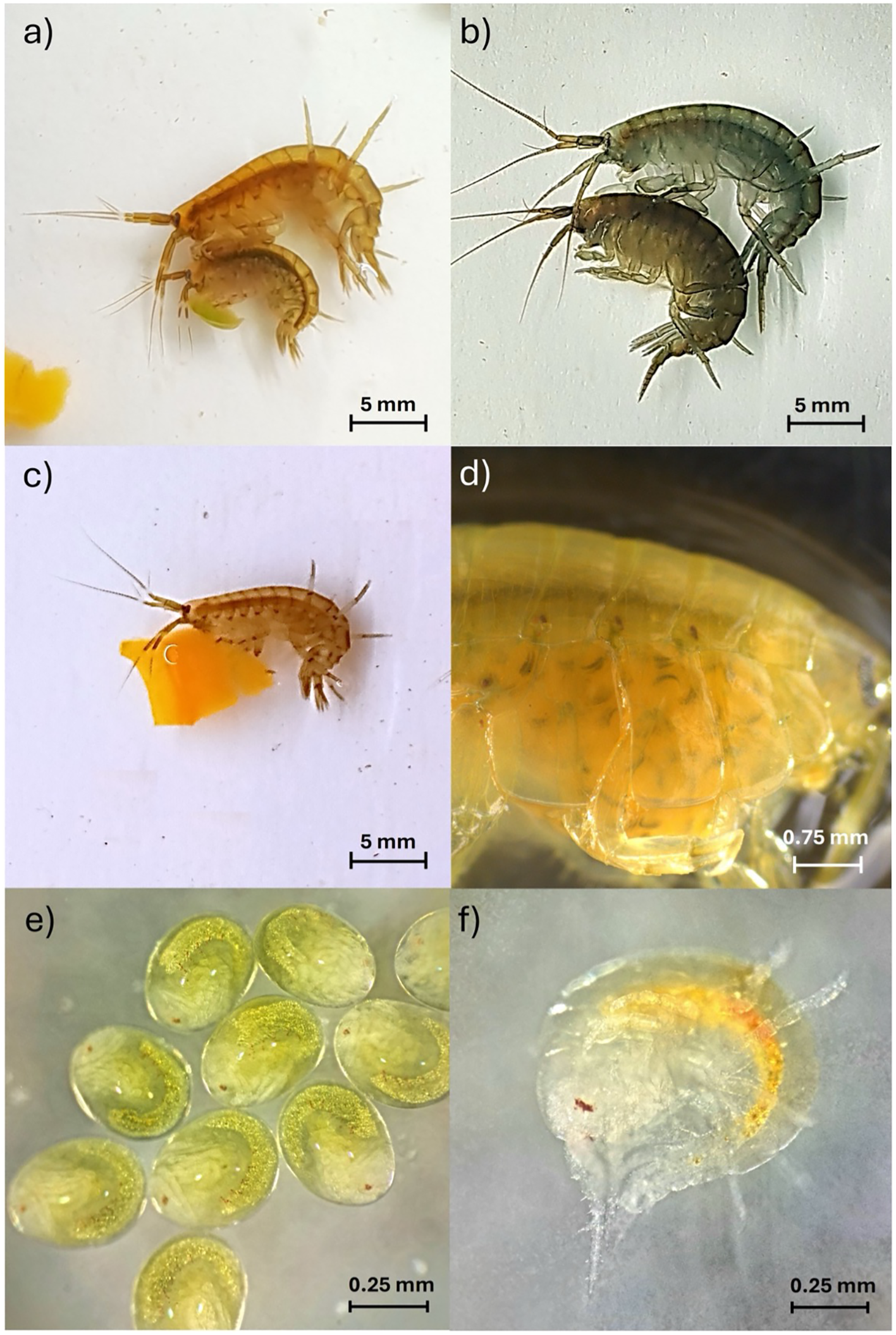

Although comprehensive lipid analyses exist for fewer than ten marine amphipod species, the available data indicate that marine gammarids often exhibit higher levels of protein, lipids, carotenoids, and essential fatty acids than many freshwater counterparts (Baeza-Rojano et al., 2014). Marine environments naturally support higher n-3 LC-PUFA availability, contributing to elevated EPA and DHA content in marine invertebrates (Ishikawa et al., 2019; Twining et al., 2021). Species such as Gammarus locusta (Figure 1a), Marinogammarus marinus (previously known as Echinogammarus marinus, Figure 1b), and Gammarus insensibilis show particularly favourable profiles (Table 1). For instance, M. marinus and G. insensibilis have been reported to contain EPA and DHA concentrations of up to 18% and 10% of their total fatty acids content, respectively (Alberts-Hubatsch et al., 2019; Jiménez-Prada et al., 2021), being competitive with several alternative feed ingredients.

Figure 1

Breeding pair of Gammarus locusta feeding on pea (a) and breeding pair of Marinogammarus marinus (male specimens on top of females) (b); G. locusta feeding on carrot (c); Ovigerous G. locusta incubating embryos in ventral abdominal pouch (marsupium) (d); G. locusta embryos (e); and neonate G. locusta immediately able to feed independently on the same feed supplied to adult conspecifics (f).

Table 1

| Species | Lipid | EPA | DHA | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gammarus insensibilis | ~6–13% | 7–18% | 4–10% | (Jiménez-Prada et al., 2021; Castilla-Gavilán et al., 2025) |

| Gammarus locusta | ~7% | 5–16% | 6–8% | (Baeza-Rojano et al., 2014; Alberts-Hubatsch et al., 2019) |

| Gammarus aequicauda | Phospholipids: ~49% of total lipids; Triacylglycerols: ~45% of total lipids | 7.5% | 2.5% | (Prato and Biandolino, 2009) |

| Marinogammarus marinus | ~9.6% | 5–20% | 5–9% | (Baeza-Rojano et al., 2014; Alberts-Hubatsch et al., 2019) |

Approximate lipid (%) and EPA and DHA (% total fatty acids) contents in selected marine gammarid species.

Data presented are limited to marine or coastal gammarid species for which published biochemical profiles relevant to aquafeed formulations are available.

The biosynthetic capacity of marine gammarids to produce n-3 LC-PUFA has been inferred from feeding trials assessing the impact of dietary fatty acids on their tissue profiles (Baeza-Rojano et al., 2014; Alberts-Hubatsch et al., 2019; Jiménez-Prada et al., 2021). The ability to synthetise n-3 LC-PUFA depends on the presence and function of key enzymes involved in fatty acid elongation and desaturation (Monroig et al., 2022). Three genes, namely elovl4, elovl6, and elovl1/7-like, encoding fatty acyl elongases, which catalyse the rate-limiting step in the fatty acid elongation pathway (Monroig et al., 2022), were recently identified in M. marinus (Ribes-Navarro et al., 2021). Functional analyses further indicated that elovl4 and elovl1/7-like act as PUFA elongases, with specificity for substrates ranging from C18 to C22. In contrast, elovl6 displayed activity limited to C18 PUFA substrates, suggesting it plays little or no role in n-3 LC-PUFA biosynthesis in marine gammarids (Ribes-Navarro et al., 2021). Although marine gammarids possess elongases involved in LC-PUFA biosynthesis, they appear to lack the desaturases required for full de novo synthesis of EPA and DHA via known biosynthetic pathways. Therefore, their ability to maintain consistently high EPA and DHA levels is therefore more likely linked to efficient dietary retention and, potentially, to microbial symbionts capable of LC-PUFA biosynthesis, although this remains to be confirmed experimentally. Building on this, the consistently high n-3 LC-PUFA content of marine gammarids appears to be strongly influenced by trophic upgrading, a process through which lower-quality dietary substrates are converted into EPA- and DHA-enriched biomass. Importantly, this enrichment does not depend on substrates of marine origin, since species such as G. locusta and G. insensibilis can maintain elevated EPA and DHA levels, even when cultured on terrestrial plant-based side streams, including lupine meal and carrot leaves (Jiménez-Prada et al., 2021; Ribes-Navarro et al., 2022). The operational implications of this trophic upgrading capacity for circular aquaculture production are further explored in Section 4.

In natural ecosystems, amphipods serve as a key trophic link and constitute an important dietary component for a wide range of demersal fish and invertebrates (Pita et al., 2002). Yet, a limited number of studies have investigated their application in aquaculture. For instance, in Norway, meal produced from the wild-caught marine pelagic amphipod Themisto libellula was used successfully as a complete replacement for FM in formulated feeds for Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and salmon (Salmo salar), resulting in growth rates comparable to or even exceeding those achieved with traditional FM-based diets (Moren et al., 2006). Several amphipod species have also been evaluated as live or whole-animal diets for rearing hatchlings of the common cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis), with marine amphipods supporting good growth compared to caprellid amphipods (Baeza-Rojano et al., 2010). Notably, the marine amphipod Hyale media has been shown to enhance the growth performance of Mexican four-eyed octopus (Octopus maya) hatchlings when compared to the freshwater amphipod Hyalella azteca or brine shrimp Artemia spp., likely due to its superior essential fatty acid profile (Baeza-Rojano et al., 2013, 2014). Studies evaluating the inclusion of marine gammarids in fish diets remain extremely limited. In amberjack (Seriola dumerili) juveniles, a diet containing G. insensibilis improved survival rates, though growth was lower compared to fish fed a commercial diet (Prada, 2018). In the same study, behavioural changes were also noted, with amberjack fed the gammarid diet displaying reduced aggressive behaviour during feeding. Although a detailed assessment of protein and amino acid composition lies outside the scope of this Perspective, marine gammarids generally also contain protein levels comparable to other marine invertebrates and show favourable amino acid profiles that align with the nutritional requirements of marine fish and shrimp species. These features may partially explain the good results achieved when gammarids biomass is incorporated in the formulation of aquafeeds (Baeza-Rojano et al., 2014).

Several freshwater amphipod species are already commercially available in the aquatic pet trade, particularly as premium feeds for water turtles and other ornamental species, and their success is often attributed to the high digestibility and palatability of amphipods. Interestingly, their marine counterparts, typically richer in n-3 LC-PUFA and therefore better suited to fulfil the dietary requirements of marine species, have remained undervalued. This contrast highlights an untapped opportunity to explore the full potential of marine gammarids, not only as aquafeed ingredients, but also for specialised feed markets that pay premium values.

4 Production traits and circular applications for aquaculture

One of the main advantages of incorporating marine gammarids into the aquafeed raw material basket is their alignment with circular bioeconomy principles. As detritivore crustaceans capable of performing trophic upgrade, they convert organic matter, including fish faeces, uneaten aquafeeds, plant by-products, and macroalgal detritus, into biomass enriched in n-3 LC-PUFA (Figures 1a, c) (Alberts-Hubatsch et al., 2019; Ribes-Navarro et al., 2022). This capacity has been reported across substrates, including plant materials, such as lupine meal, carrot leaves (Ribes-Navarro et al., 2022), and marine detritus (Jiménez-Prada et al., 2021; Castilla-Gavilán et al., 2023, 2025). Under controlled conditions, G. insensibilis was able to remove approximately 155–170 mg DW detritus g-1 day-1 with survival above 80%, highlighting its efficiency as an extractive species and its potential contribution to nutrient recovery within aquaculture systems (Castilla-Gavilán et al., 2023).

From a production viewpoint, integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) currently appears the most feasible and potentially cost-effective pathway for large-scale cultivation. Amphipods naturally colonise aquaculture structures at high densities and can be harvested using simple, inexpensive collectors, achieving biomass purities exceeding 86% and estimated yields of up to ~1 tonne per year in standard cage farms (Fernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2018). IMTA systems also benefit from existing hydrodynamics, waste streams, and substrates, enabling passive, low-maintenance production.

There is also increasing interest in integrated biofloc technology (BFT) systems, which combines microbial productivity with nutrient recycling (Castilla-Gavilán et al., 2025). In these systems, residues from one species stimulate biofloc formation, which can then support secondary organisms. Although still emerging, a recent study reported that marine gammarids, more specifically G. insensibilis, can be incorporated into integrated BFT settings, utilising RAS effluents as a nutrient source and contributing to enhanced LC-PUFA profiles in bioflocs (Castilla-Gavilán et al., 2025). This adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that low trophic level species could enhance the functionality of BFT systems by improving waste valorisation and contributing an additional high-quality biomass that meets the nutritional requirements of aquaculture species, such as salmonids, marine crustaceans, gilthead sea bream, and turbot. Nonetheless, integrated BFT systems remain in the early stages of development for amphipods, with only two studies using these organisms to date (Promthale et al., 2021; Castilla-Gavilán et al., 2025). Compared to IMTA, BFT systems require greater technological input, including continuous aeration, management of the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, and a tighter water-quality control, which can increase operational costs and biosecurity demands. Survival and performance of amphipods in BFT systems appear to depend on the quality and origin of detrital inputs, and long-term production efficiency, reproductive rates, and harvesting strategies remain largely unquantified. Nonetheless, BFT should be regarded as a promising complementary system for producing marine gammarids that certainly deserve further investigation.

A balanced assessment of feasibility must also consider the challenges associated with scaling-up gammarids production. High-density cultures may increase susceptibility to disease, ammonium accumulation can depress feeding activity, and harvesting efficiency will certainly vary between systems and environmental contexts (Castilla-Gavilán et al., 2023). Seasonal fluctuations in natural amphipod recruitment and labour associated with collector handling can further influence productivity in IMTA systems. Moreover, published information on the economic costs of marine gammarids production is extremely limited, and to our best knowledge, no comprehensive techno-economic analyses are currently available. Thus, the present evaluations of feasibility and cost-effectiveness are theoretical and based primarily on biological performance and system-level synergies, rather than detailed financial modelling.

Additionally, from a biological and operational perspective, marine gammarids present favourable traits that support aquaculture feasibility: tolerance to a wide salinity range (Vargas-Abúndez et al., 2021), reproduction via direct development, avoiding free-swimming larval stages, and low incidence of cannibalism, facilitating single-tank production and reducing operational complexity and costs. Females brood embryos within a specialised ventral abdominal pouch, the marsupium (Figures 1d, e), from which fully formed juveniles “hatch”. These juveniles are immediately capable of feeding on the same diets supplied to adults, which simplifies culture protocols and reduces the need for a specialised larviculture infrastructure (Figure 1f).

In addition, in contrast to plant crops or terrestrial insect production systems (Smetana et al., 2023), marine gammarid production does not require freshwater or arable land, and they can be reared in three-dimensional aquatic systems. This allows for increased production yields without expanding spatial footprint, enhancing their potential as a sustainable aquafeed source (Harlıoğlu and Farhadi, 2018).

Taken together, these traits suggest that marine gammarids not only represent a nutritionally valuable source of n-3 LC-PUFA but also offer operational advantages for circular, resource-efficient aquaculture production.

5 From potential to application

Despite their innovative potential, the transition of marine gammarids from experimental candidates to viable commercial sources of n-3 LC-PUFA requires coordinated optimisation rather than further exploratory studies alone.

First, scalable production systems must be developed through the standardisation of robust and cost-effective rearing protocols. Although biomass yields may not yet match those of other emerging n-3 LC-PUFA sources, their compatibility with co-cultured and multi-trophic systems provides distinct operational advantages. Successful intensification will depend on systems that maintain water quality, minimise pathogen risks, and integrate efficiently within IMTA or BFT frameworks. While freeze-drying and milling technologies are already used for ornamental amphipod biomass, commercial-scale production for aquafeeds will require further optimisation to achieve economic viability, supported by pilot-scale trials and techno-economic assessments.

Second, feeding strategies should prioritise locally available agricultural and marine side streams. Although EPA- and DHA-rich biomass can be produced from plant-based substrates, further research is needed to quantify trophic-upgrading efficiency across species, measure variability under different feedstocks, and evaluate regulatory or consumer-related risks. These insights are fundamental for establishing long-term production reliability.

Third, additional nutritional trials are required to evaluate the efficacy of gammarid-derived ingredients in diets for key aquaculture species. Studies should examine growth performance, feed conversion, fillet quality, health indicators, and consumer acceptance across realistic inclusion levels. Benchmarking gammarids against other emerging n-3 LC-PUFA sources, such as microalgae, krill, or insect meals, will help position their role within diversified feed portfolios.

Taken together, these steps highlight the need for targeted research and development to bridge current knowledge gaps. While preliminary evidence indicates strong potential for marine gammarids as a complementary aquafeed ingredient, their practical implementation will depend on parallel progress in nutritional validation, operational performance, and cost-effectiveness.

6 Concluding remarks

The biological traits of marine gammarids, including their broad salinity tolerance, direct development, and naturally low cannibalism, support their suitability for controlled culture systems. Their favourable biochemical composition, including consistently high levels of EPA and DHA and their capacity to maintain these fatty acids when reared on low-value substrates, highlights their promise as a sustainable feed ingredient. Their ability to recycle nutrients and integrate into IMTA or BFT systems further aligns with circular-economy objectives and strengthens their potential contribution to environmentally efficient aquaculture production.

Nevertheless, several gaps must be addressed. Rearing protocols, scalable production systems, and cost-efficient feeding strategies require further optimisation, and nutritional trials across major aquaculture species remain limited. Regulatory and safety considerations, particularly regarding the use of side streams, must also be clarified to support broader adoption.

Addressing these research needs will determine whether marine gammarids can transition from experimental organisms to practical aquafeed ingredients. While unlikely to fully resolve the n-3 LC-PUFA supply challenge, they may represent a valuable complementary ingredient within future aquafeed formulations, supporting a more diversified, resilient, and sustainable feed industry.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

RC: Resources, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. MC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Visualization. LM: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. DR: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – review & editing. FR: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. MD: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JF: Writing – review & editing. RS: Writing – review & editing. DM: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. AM: Writing – review & editing. ÓM: Writing – review & editing. ML: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was performed under the scope of project “BLUE BIOECONOMY PACT” (Project N° C644915664-00000026), co-funded by the Next Generation EU European Fund, under the incentive line “Agendas for Business Innovation” within Component 5—Capitalization and Busi-ness Innovation of the Portuguese Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), specifically under the vertical WP7 – Fish (LowTrophAqua), as well as under the scope of project “PUFAPODS Merging blue and green food systems - Using marine gammarid amphipods supplied with plant food processing side streams to produce n-3 LC-PUFA” which is supported by FCT/MEC https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.01620.PTDC. This work was funded by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia I.P., under the project CESAM-Centro de Estudos do Ambiente e do Mar, references UID/50017/2025 (doi.org/10.54499/UID/50017/2025) and LA/P/0094/2020 (doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0094/2020), PhD Scholarship (2021.04675.BD to JFF), and research contracts awarded to DM (2022.00153.CEECIND), ML (CEECIND/01618/2020) and FR (CEECIND/00580/2017) under the Scientific Employment Stimulus Programme.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ahyong S. T. (2020). “ Evolution and radiation of crustacea,” in The Natural History of the Crustacea: Evolution and Biogeographyof the Crustacea, vol. 8. ( Oxford University Press USA, USA), 53–79.

2

Alberts-Hubatsch H. Slater M. J. Beermann J. (2019). Effect of diet on growth, survival and fatty acid profile of marine amphipods: implications for utilisation as a feed ingredient for sustainable aquaculture. Aquac. Environ. Interact.11, 481–491. doi: 10.3354/aei00329

3

Baeza-Rojano E. Domingues P. Guerra-García J. M. Capella S. Noreña-Barroso E. Caamal-Monsreal C. et al . (2013). Marine gammarids (Crustacea: Amphipoda): a new live prey to culture Octopus maya hatchlings. Aquac. Res.44, 1602–1612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2012.03169.x

4

Baeza-Rojano E. García S. Garrido D. Guerra-García J. M. Domingues P. (2010). Use of Amphipods as alternative prey to culture cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) hatchlings. Aquaculture300, 243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.12.029

5

Baeza-Rojano E. Hachero-Cruzado I. Guerra-García J. M. (2014). Nutritional analysis of freshwater and marine amphipods from the Strait of Gibraltar and potential aquaculture applications. J. Sea Res.85, 29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2013.09.007

6

Barroso F. G. de Haro C. Sánchez-Muros M.-J. Venegas E. Martínez-Sánchez A. Pérez-Bañón C. (2014). The potential of various insect species for use as food for fish. Aquaculture422–423, 193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.12.024

7

BioMarine A. (2022). Krill: what are the costs versus benefits for feed manufacturers? ( International Aquafeed), 16–17. Available online at: https://145359403.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/145359403/International%20Aquafeed2202.pdf (Accessed December 3, 2025).

8

Castilla-Gavilán M. Guerra-García J. M. Hachero-Cruzado I. (2025). Integrating Gammarus insensibilis in biofloc systems: A sustainable approach to nutrient enrichment and waste valorisation in aquaculture. Aquaculture597, 741922. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741922

9

Castilla-Gavilán M. Guerra-García J. M. Moreno-Oliva J. M. Hachero-Cruzado I. (2023). How much waste can the amphipod Gammarus insensibilis remove from aquaculture effluents? A first step toward IMTA. Aquaculture573, 739552. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.739552

10

Cavan E. L. Belcher A. Atkinson A. Hill S. L. Kawaguchi S. McCormack S. et al . (2019). The importance of Antarctic krill in biogeochemical cycles. Nat. Commun.10, 4742. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12668-7

11

FAO (2024). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 – Blue Transformation in action (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations). doi: 10.4060/cd0683en

12

Fernandez-Gonzalez V. Toledo-Guedes K. Valero-Rodriguez J. M. Agraso M. M. Sanchez-Jerez P. (2018). Harvesting amphipods applying the integrated multitrophic aquaculture (IMTA) concept in off-shore areas. Aquaculture489, 62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.02.008

13

Glencross B. D. Bachis E. Betancor M. B. Calder P. Liland N. Newton R. et al . (2024). Omega-3 futures in aquaculture: Exploring the supply and demands for long-chain omega-3 essential fatty acids by aquaculture species. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac.33 (2), 1–50. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2024.2388563

14

Glencross B. Fracalossi D. M. Hua K. Izquierdo M. Mai K. Øverland M. et al . (2023). Harvesting the benefits of nutritional research to address global challenges in the 21st century. J. World Aquac. Soc54, 343–363. doi: 10.1111/jwas.12948

15

Harlıoğlu M. M. Farhadi A. (2018). Importance of Gammarus in aquaculture. Aquac. Int.26, 1327–1338. doi: 10.1007/s10499-018-0287-6

16

Hossain M. S. Small B. C. Hardy R. (2023). Insect lipid in fish nutrition: Recent knowledge and future application in aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 15(4), 1664–1685. doi: 10.1111/raq.12810

17

Ishikawa A. Kabeya N. Ikeya K. Kakioka R. Cech J. N. Osada N. et al . (2019). A key metabolic gene for recurrent freshwater colonization and radiation in fishes. Science364, 886–889. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5656

18

Izquierdo M. (2005). Essential fatty acid requirements in Mediterranean fish species. Cahiers Options Méditerranéennes63, 91–102. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/39665747.

19

Jiménez-Prada P. Hachero-Cruzado I. Guerra-García J. M. (2021). Aquaculture waste as food for amphipods: the case of Gammarus insensibilis in marsh ponds from southern Spain. Aquac. Int.29, 139–153. doi: 10.1007/s10499-020-00615-z

20

Kerdiles O. Layé S. Calon F. (2017). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and brain health: Preclinical evidence for the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Food Sci. Technol.69, 203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.09.003

21

Monroig Ó. Shu-Chien A. C. Kabeya N. Tocher D. R. Castro L. F. C. (2022). Desaturases and elongases involved in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in aquatic animals: From genes to functions. Prog. Lipid Res.86, 101157. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2022.101157

22

Monteiro J. P. Domingues M. R. Calado R. (2024). Marine animal co-products-how improving their use as rich sources of health-promoting lipids can foster sustainability. Mar. Drugs22, 73. doi: 10.3390/md22020073

23

Moren M. Suontama J. Hemre G.-I. Karlsen Ø. Olsen R. E. Mundheim H. et al . (2006). Element concentrations in meals from krill and amphipods, — possible alternative protein sources in complete diets for farmed fish. Aquaculture261, 174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.06.022

24

Pita C. Gamito S. Erzini K. (2002). Feeding habits of the gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) from the Ria Formosa (southern Portugal) as compared to the black seabream (Spondyliosoma cantharus) and the annular seabream (Diplodus annularis). J. Appl. Ichthyol.18, 81–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0426.2002.00336.x

25

Prada P. J. (2018). Aplicaciones de los anfípodos (Crustacea: Peracarida: Amphipoda) en acuicultura (Sevilla, Spain: University of Sevilla).

26

Prato E. Biandolino F. (2009). Factors influencing the sensitivity of Gammarus aequicauda population from Mar Piccolo in Taranto (Southern Italy). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.72, 770–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.12.020

27

Promthale P. Withyachumnarnkul B. Bossier P. Wongprasert K. (2021). Nutritional value of the amphipod Bemlos quadrimanus sp. grown in shrimp biofloc ponds as influenced by different carbon sources. Aquaculture533, 736128. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.736128

28

Ribes-Navarro A. Alberts-Hubatsch H. Monroig Ó. Hontoria F. Navarro J. C. (2022). Effects of diet and temperature on the fatty acid composition of the gammarid Gammarus locusta fed alternative terrestrial feeds. Front. Mar. Sci.19, 226. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.931991

29

Ribes-Navarro A. Navarro J. C. Hontoria F. Kabeya N. Standal I. B. Evjemo J. O. et al . (2021). Biosynthesis of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in marine gammarids: molecular cloning and functional characterisation of three fatty acyl elongases. Mar. Drugs19. doi: 10.3390/md19040226

30

Smetana S. Bhatia A. Batta U. Mouhrim N. Tonda A. (2023). Environmental impact potential of insect production chains for food and feed in Europe. Anim. Front.13, 112–120. doi: 10.1093/af/vfad033

31

Sprague M. Betancor M. B. Tocher D. R. (2017). Microbial and genetically engineered oils as replacements for fish oil in aquaculture feeds. Biotechnol. Lett.39, 1599–1609. doi: 10.1007/s10529-017-2402-6

32

Tocher D. R. (2015). Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and aquaculture in perspective. Aquaculture449, 94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.01.010

33

Tocher D. R. Betancor M. B. Sprague M. Olsen R. E. Napier J. A. (2019). Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, EPA and DHA: Bridging the gap between supply and demand. Nutrients11, 89. doi: 10.3390/nu11010089

34

Twining C. W. Bernhardt J. R. Derry A. M. Hudson C. M. Ishikawa A. Kabeya N. et al . (2021). The evolutionary ecology of fatty-acid variation: Implications for consumer adaptation and diversification. Ecol. Lett.24, 1709–1731. doi: 10.1111/ele.13771

35

Vargas-Abúndez J. A. López-Vázquez H. I. Mascaró M. Martínez-Moreno G. L. Simões N. (2021). Marine amphipods as a new live prey for ornamental aquaculture: exploring the potential of Parhyale hawaiensis and Elasmopus pectenicrus. PeerJ9, e10840. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10840

Summary

Keywords

aquafeeds, circular economy, fatty acids, marine gammarids, trophic upgrading

Citation

Calado R, Carvalho M, Marques L, Rodrigues DP, Sousa JP, Rey F, Domingues MR, Fernandes JF, Silva RXG, Madeira D, Malzahn AM, Monroig Ó and Leal MC (2025) Why marine gammarids belong to the future portfolio of aquafeed ingredients. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1697384. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1697384

Received

02 September 2025

Revised

24 November 2025

Accepted

24 November 2025

Published

10 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Amit Ranjan, Tamil Nadu Fisheries University, India

Reviewed by

Sílvia Lourenço, Instituto Politécnico de Leiria, Portugal

Rakhi Kumari, Central Institute of Freshwater Aquaculture (ICAR), India

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Calado, Carvalho, Marques, Rodrigues, Sousa, Rey, Domingues, Fernandes, Silva, Madeira, Malzahn, Monroig and Leal.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ricardo Calado, rjcalado@ua.pt; Marta Carvalho, marta.carvalho@sciencecrunchers.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.