Abstract

The marine ecosystem is one of the world’s largest reservoirs, with billions of species interacting. It harbors a diverse array of macro- and microorganisms equipped with unique metabolic abilities and intricate interactions enabling adaptation to challenging environments, resulting in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. The expanding field of marine (blue) biotechnology investigates various, frequently disregarded aquatic ecosystems as viable and sustainable sources of biomolecules and biomass to meet these social demands. With a focus on the identification and industrial significance of bioactive chemicals and bioproducts derived from microbes, this review endeavors to present an in-depth analysis of marine microbial bioprospecting. Marine microbial exploration has produced thousands of structurally unique metabolites over the past few decades, many of which have shown industrial or medicinal significance. Approximately 28,500 marine natural products including polysaccharides, peptides, polyketides, polyphenolic compounds, sterol-like products, and alkaloids, had been identified as of 2016. Owing to developments in synthetic biology and metagenomics, the frequency of discovery has significantly increased since the 2000s, and the present review systematically compiles these advancements using a PRISMA-based screening framework. In its entirety, this review emphasizes the critical ecological and biotechnological aspects of marine microorganisms and proposes a conceptual and quantitative foundation for further research into marine microbial resources in pharmaceutical development and sustainable biotechnology. The review was developed through a comprehensive literature search conducted using public databases.

1 Introduction

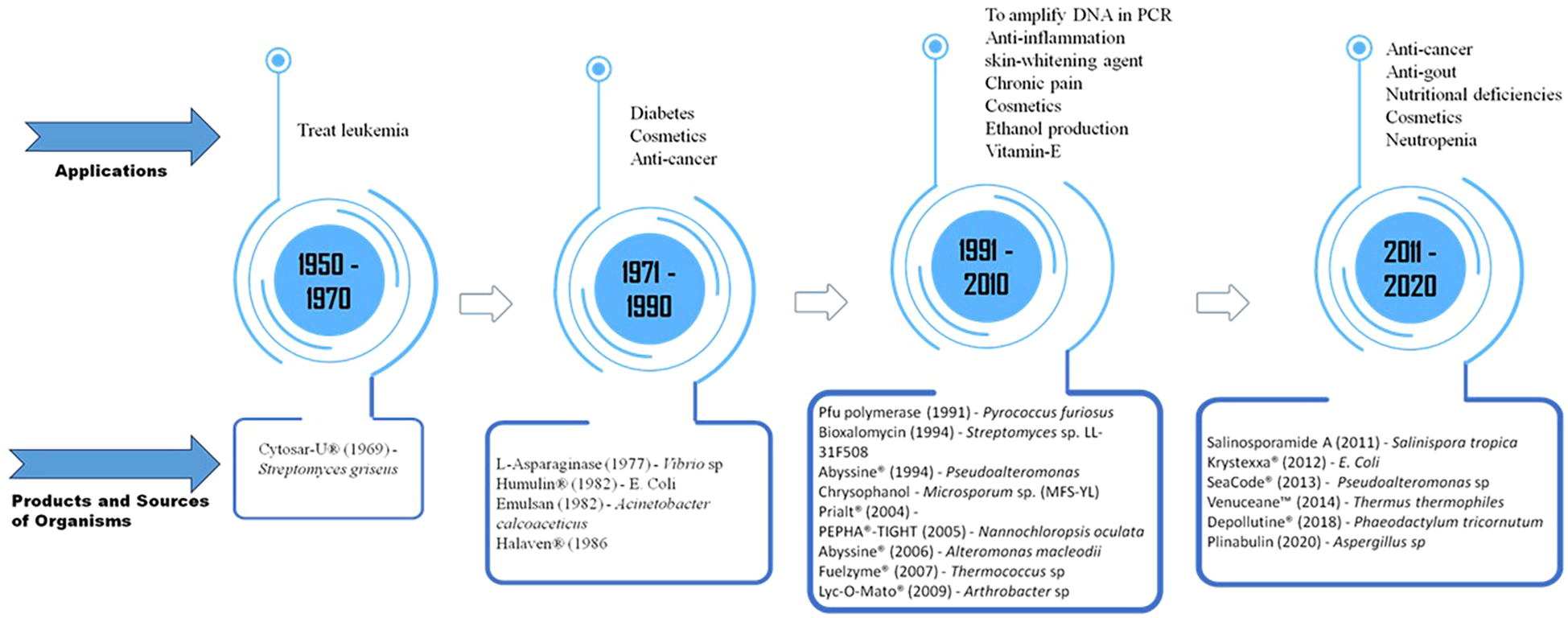

The marine ecosystem encompasses approximately 70% of the Earth’s surface, and it is home to a remarkable diversity of life forms that produce bioactive compounds with potential applications, from medicine to biotechnology. Marine organisms, including bacteria, algae, and fungi, have evolved unique molecular and metabolic pathways to survive in extreme environments, which led to the production of compounds with incredible properties (Karthikeyan et al., 2022). These microscopic yet extremely prevalent organisms play vital roles in biogeochemical processes and help to regulate the environment and ensure the ongoing stability and functioning of life on Earth (Zhang et al., 2024). Extremophiles are special organisms that thrive in tough conditions, helping them produce these extraordinary compounds (Coutinho et al., 2018). Bioactive compounds produced by microbial strains from various substrates—including marine sediments, mangrove debris, and seawater—offer a wide range of applications across pharmaceuticals, cosmeceuticals, nutraceuticals, and green energy sectors (Andryukov et al., 2018). The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) was declared by the UN General Assembly in December 2017 in order to promote international efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which concentrate on the conservation and sustainable use of the oceans and marine resources. These advancements are in direct line with the SDGs, including SDG 3 (Good Health & Well-Being), SDG 7 (Affordable & Clean Energy), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation & Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption & Production), and SDG 14 (Life Below Water). Through coordinated research and innovation, the ERA-NET Cofund BlueBio project, which falls in accordance with the European Green Deal, seeks to promote Europe’s blue bioeconomy by utilizing aquatic bioresources for sustainable food and bio-based goods. Moreover, the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) has advanced aquaculture and marine biotechnology through funding and R&D. These developments have greatly helped coastal farmers and bolstered India’s blue biotechnology industry (European Commission, 2019; Department of Biotechnology (DBT), 2023). Marine habitats’ remarkable biological and taxonomic diversity significantly impacts the microbial communities’ biochemical adaptability, leading to an unprecedented range of bioactive compounds. The biomolecules present in seawater, which share a similar chemical composition with human blood plasma, exhibit lower toxicity and enhanced therapeutic potential compared to conventional enzymes. Consequently, it is not surprising that the number of studies exploring marine microorganisms as sources of bioactive metabolites continues to increase annually. Therefore, in contemporary studies, attention is directed toward the secondary metabolites obtained from marine ecosystems, potentially harboring unique characteristics. Discovering novel metabolites has been bolstered with the help of advanced techniques in genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics (Nugraha et al., 2023). In order to comply with societal demands (healthcare, economy, and ecosystem), the growing area of “blue” biotechnology has lately concentrated on overlooked aquatic niches as sustainable supplies of bioactive metabolites and biomass. According to estimates, the worldwide marine biotechnology sector was valued at approximately USD 6.2 billion in 2024 and was expected to increase at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 7%–8% to reach USD 8.9 billion by 2029. An additional projection sets the market at approximately USD 6.78 billion in 2024 and will reach over USD 13.6 billion by 2034 (Rotter et al., 2021). In order to address the dearth of comprehensive assessments that link ecological diversity, omics-driven advancements, and potential bioeconomic implications, this study summarizes seven decades of marine microbial bioprospecting. Furthermore, it highlights the role of marine microbes in nature and their potential to produce valuable natural compounds, summarizing past progress and future prospects in marine biotechnology.

2 Methodology

2.1 Data collection

A comprehensive bibliographic review was conducted on the potential of marine microbial bioprospecting for diverse industrial sectors such as pharmaceuticals, sustainable energy, and therapeutics. In addition, quantitative data were gathered from major scientific databases—SciFinder, PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Google Scholar—along with relevant academic and reference publications.

2.2 Search and eligibility criteria

The following search query was applied to retrieve literature relevant to this review: ((“marine bacteria” OR “extremophiles” OR “marine microbes” OR “marine sources”) AND (“bioactive compounds” OR “industrial significance” OR “antimicrobial” OR “anticancer” OR “antioxidant” OR “anti-inflammatory”) AND (“isolation” OR “characterization” OR “bioprospecting” OR “biotechnological potential” OR “drug discovery”)), and meta-analysis was used. Exceptional original research articles, studies concerning the secondary metabolites or bioactive compounds from marine microbes and their industrial as well as ecological significance, and English-language publications were the inclusion criteria, regardless of the year of publication.

2.3 Data analysis

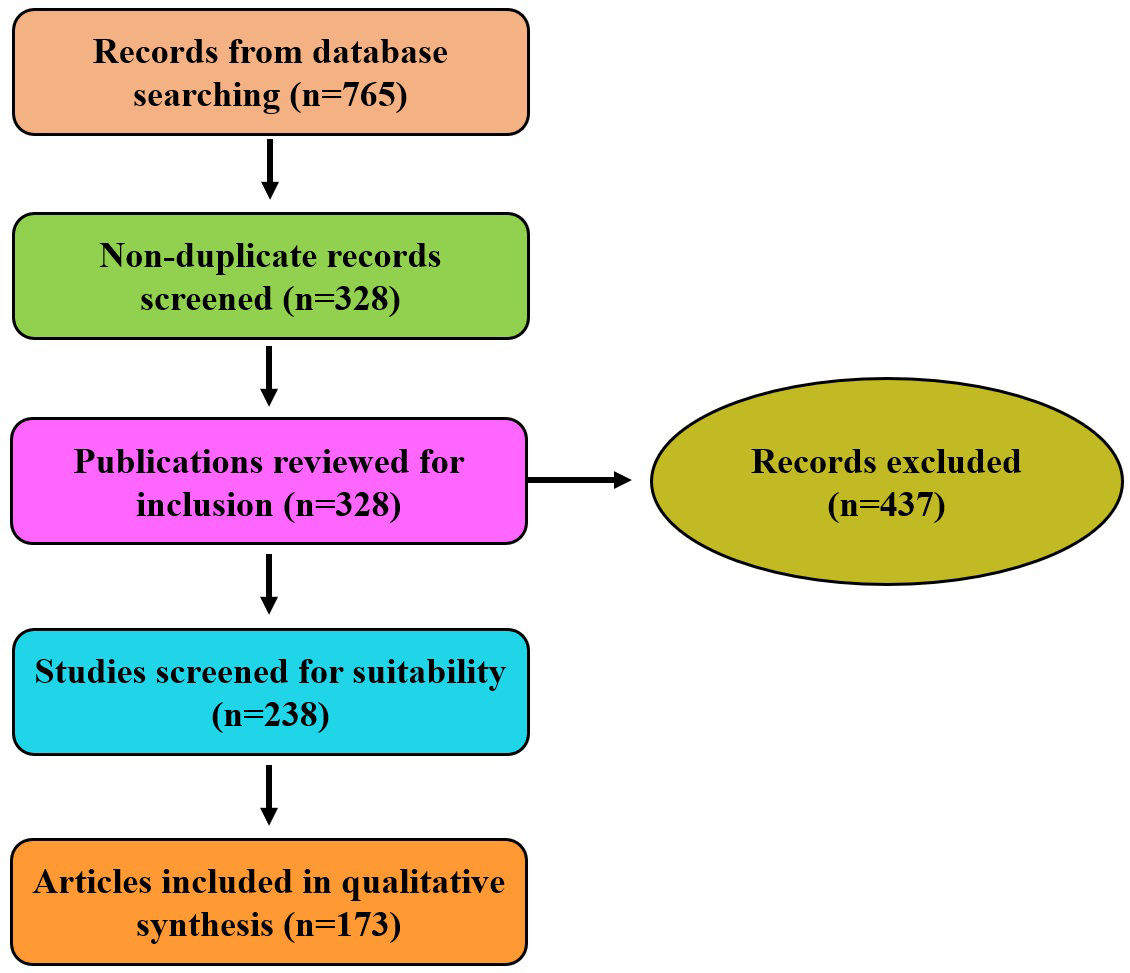

To ensure a comprehensive assessment, relevant data were extracted and systematically compiled from the selected studies. The extracted information primarily focused on the types of industrial applications explored, the marine microbial sources and their associated bioactive metabolites, and the reported mechanisms of action (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow schematic representation of the literature screening and inclusion process.

3 Complex marine habitats

Marine ecosystems are characterized by high and low temperatures, extreme pressure, elevated salinity levels, anaerobic conditions, and combinations of extreme conditions called polyextremophilic environments (Kumbhare et al., 2015). It is clear that marine polyextremophiles have distinct structural alterations in their lipid, enzyme, and biopolymer in order to thrive in hot, cold, and salty circumstances (Sorokin et al., 2014). Extremophiles are categorized according to the various environmental conditions in which they evolve, i.e., acidophiles (<pH 5), alkaliphiles (>pH 9), psychrophiles (0°C–20°C), thermophiles (45°C–80°C), hyperthermophiles (>80°C), halophiles (2.5–5.2 M salt), xerophiles (low water activity), and barophiles (high pressure >38–50 MPa), which synthesize secondary metabolites with great values and remain resilient (Mashakhetri et al., 2024). Due to the pressure variance, most psychrophilic organisms are commonly known as piezophiles. Belonging to the Gamma-proteobacteria class, these organisms are represented by five genera: Shewanella, Moritella, Photobacterium, Colwellia, and Psychromonas (Fang et al., 2010). In the harsh climatic conditions of the Antarctic ecosystem, bacteria, fungi, algae, and viruses can also survive (Cowan et al., 2010). Since extremophiles produce potential bioactive compounds, they have garnered attention in recent decades. In marine ecosystems, competition for nutrients and space creates a selection pressure that drives evolution, ending up with the development of unique metabolites to adapt to varying environmental conditions (Di Donato et al., 2018). To illustrate these ecological and metabolic differences, a comparative summary of terrestrial and marine microbial outputs is provided (Table 1). Halophiles, which include archaea, bacteria, and eukarya, are salt-loving organisms from hypersaline habitats with varying NaCl requirements (Corral et al., 2019). When compared to proteins found under normal circumstances, such as transcription binding protein (TBP), TATA-box-binding protein (improved DNA interaction), and P45 protein (prevents denaturation inhibition of malate dehydrogenase), halophilic proteins are distinct and have a comparatively larger salt bridge (Kumar et al., 2018). As demonstrated by Thiobacillus ferrooxidans, which possesses a sizable external loop that restricts ion transport, acidophiles adapt by decreasing membrane permeability through reduced pore diameters. In order to survive acidic environments, they also raise their negative surface charge (Hunter and Christopher, 2018). Extremophiles demonstrate remarkable biochemical adaptability, producing highly stable metabolites and enzymes tailored to harsh environments (Table 2).

Table 1

| Parameter | Marine microbes | Terrestrial microbes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological perspective | Extreme habitats are home (saline, high pressure, low temperature); high phylogenetic novelty | Widely distributed across soils and plants; higher biomass density | Ren et al. (2018) |

| Metabolic diversity and unique scaffolds | Rich chemical novelty; polycyclic ethers, halogenated compounds | Classical scaffold dominance (β-lactams, polyketides, terpenoids) | Wang et al. (2022); Cappiello et al. (2020) |

| Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) | High in cryptic BGCs | Increased proportion of expressed BGCs | Lai et al. (2025) |

| Enzymatic profile | Cold-active, salt-tolerant, piezophilic, thermostable; stable for industrial extremes | Mostly mesophilic; limited extremophilic properties | Canganella and Wiegel (2011) |

| Extent of exploration | Underexplored; high proportion of undiscovered metabolites | Relatively well explored; slow pace of scaffold innovation | Wang et al. (2024) |

Comparative analysis of marine vs. terrestrial microbial outputs.

Table 2

| Habitat | Organism | Adaptation strategy | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophilic Archaea | Methanopyrus kandleri | Produce specific molecular thermosome (30), a chaperonin protein that reacts only at very high temperatures | Membrane fluidity increases with an increment in temperature. To maintain and to keep the optimum fluidity of the membrane | Barzkar et al. (2018) |

| Thermococcus kodakarensis | The combined action of reverse gyrase and DNA topoisomerase II that removes negative supercoils | The removal of the reverse gyrase encoding gene from the chromosome leads to reduced growth rates in the mutant strain | Ghosh et al. (2020) | |

| Pyrococcus furious | Produce thermostable pyrolysin | Enhanced thermal stability correlates with a higher density of ion-pair networks at elevated temperatures. | Ghosh et al. (2020) | |

| Psychrophilic Bacteria | Pyrococcus haloplanktis | Overexpressed RNA helicase in low temperatures | Help to unwind the RNA secondary structures for efficient translation in the cold and optimize protein synthesis at low temperatures | Feller (2013) |

| Kocuria polaris | Higher proportion of unsaturated fatty acids | Fluidity and the ability to transport nutrients are maintained even under very cold conditions | Kumar Chattopadhyay et al. (2014) | |

| Halophilic Bacteria | Salinibacter ruber | An increase in the quantity of acidic amino acid residues on the protein surface | Protect the enzyme from aggregation under high salinity | Sinha and Khare (2014) |

| Haloferax alexandrines | Produced small heat shock-like proteins (sHSPs) | Increased the production of protective red carotenoid pigment | Thombre et al. (2016) |

Mechanistic strategies of extremophiles’ adaptation.

4 Exploring the potential of marine microbial applications

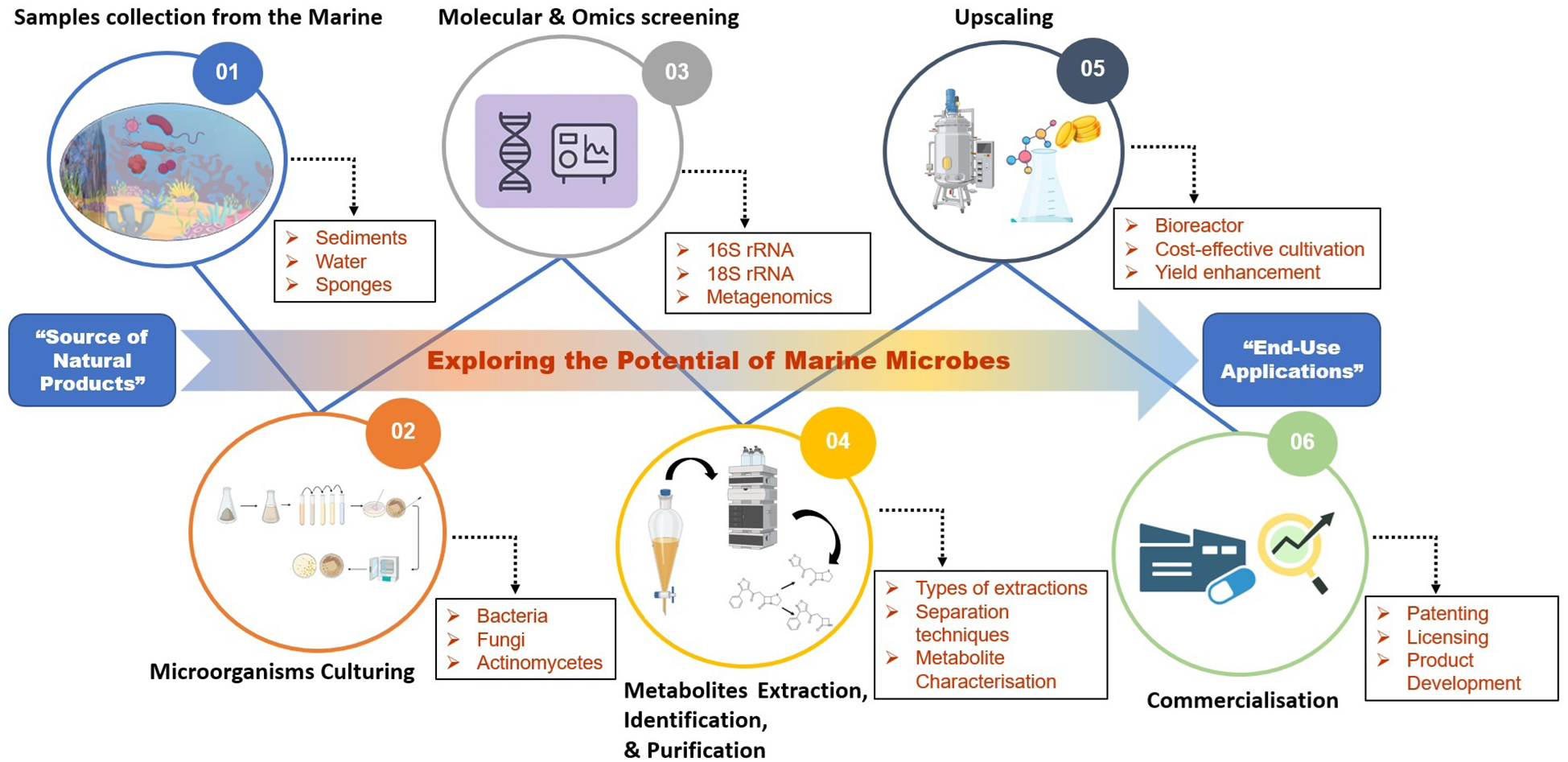

Several microbial species have evolved special traits as a result of their adaptation to extreme environments. These adaptive strategies play a crucial role in a number of essential biotechnological applications. Marine microbes are major suppliers of a variety of biopolymers, extremozymes, etc.; one such example is soil-degrading extremozymes employed in remediating hazardous pollutants (Shukla et al., 2020). Because of improvements in culturing methods, complex marine microorganisms are still cultured in order to discover novel secondary metabolites. The vast genetic and biochemical diversity present in marine microorganisms, though still in its early stages of exploration, holds significant promise as a potential source of valuable metabolites. Despite being in its infancy, research on the biochemical and genetic diversity of marine microbes has already uncovered bioactive metabolites with unanticipated industrial applications; notably, in 2016, 179 novel substances were discovered from marine microorganisms (Blunt et al., 2018). These applications span various sectors such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and nutraceuticals, as well as the production of biofuels and biopolymers. The complete marine microbial bioprospecting pipeline is shown in Figure 2, highlighting prospects for innovation at several stages.

Figure 2

Marine microbial bioprospecting pipeline.

4.1 Pharmaceuticals

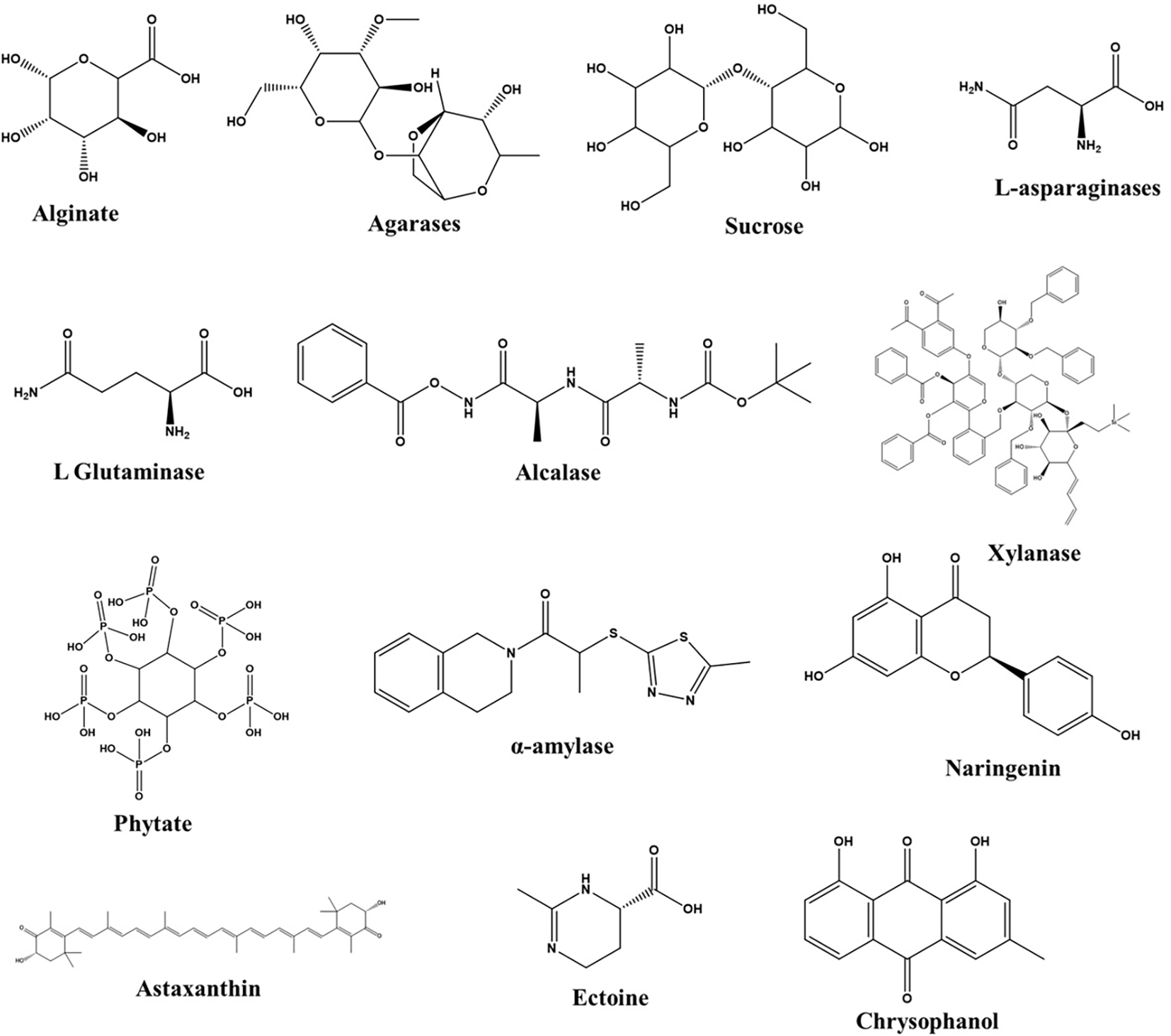

The marine ecosystem offers a bountiful supply of novel bioactive metabolites that are both structurally and physiologically stable (Figure 3). Within the pharmaceutical industry, there is a heavy dependence on these stable primary and secondary metabolites derived from marine microorganisms. These metabolites exhibit diverse biological activities, fueling the development of innovative pharmaceutical formulations. With increasing demands for marine-based pharmaceuticals to address both emerging and existing diseases, the exploration of marine microbial metabolites presents an intriguing area of research (Table 3).

Figure 3

Major bioactive metabolites synthesized by marine bacteria.

Table 3

| Pharmacological activity | Marine microbial source | Geographical location | Biological target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial activity |

Oscillatoria simplicissima, Oscillatoria acutissima, and Spirulina platensis |

Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea coast | Staphylococcus aureus, Micrococus luteus, Serratia marcescens, Salmonella spp., Vibrio spp., Aeromonas hydrophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans | Elkomy (2020) |

| Antibacterial activity | Strain Al-Dhabi-91 of Streptomyces parvus | Saudi Arabian marine region | Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli | Al-Dhabi et al. (2019) |

| Streptomyces sp. VITSTK7 | Bay of Bengal, Puducherry | Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus cereus, Klebsiella pneumonia | Thenmozhi and Kannabiran (2012) | |

| Antibacterial & antifungal activity | Tetraselmis sp. | Moroccan coastlines | Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, and Aspergillus niger | Maadane et al. (2017) |

| Antifungal activity | Sarcophytonglaucum | Red Sea | Penicillium sp., Aspergillus niger, Candida albicans | ElAhwany et al. (2015) |

| Halophilic strains GD3007 and DM0207 | Solar saltpans of Thoothukudi District | Aspergillus niger and Penicillium chrysogenum | Deepalaxmi and Gayathri (2018) | |

| 10 strains of Streptomyces sp. ACT2 | Mangrove estuaries of Tamil Nadu | Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Epidermophyton floccosum, and Microsporum canis | Suresh et al. (2020) | |

| Antagonistic activity | 16 actinomycete isolates | Hurghada City and the Suez Gulf |

Aeromonas hydrophila, Vibrio damsela, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC6538, Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC9027, Salmonella typhimurium ATCC14028, Escherichia coli ATCC19404, and Candida albicans ATCC 10231 |

Hamed et al. (2019) |

| Anti-virulence activity | Aspergillus welwitschiae FMPV 28 | Marine sponge Taedania sp. collected in Ponta Verde reef, Alagoas State, Brazil |

Staphylococcus aureus | Endres et al. (2022) |

The therapeutic virtue of marine microbes.

4.1.1 Antibacterial activity

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a serious global concern that makes it harder to treat infectious diseases caused by microbial agents (Jani et al., 2021). To overcome the pathogenesis and induced resistance by microbes, it is inevitable to discover new/alternative antibiotics. For the successful discovery of secondary metabolites that are structurally and biochemically unique, the variety of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in genome-sequenced bacteria provides significant information. Using the MIBiG database, clustering thresholds for BGC and molecular networks were altered to reflect the chemical analogies between GCF (gene cluster family)-encoded compounds and MF (molecular family) assemblies in order to assess the uncharted biosynthetic realm of marine prokaryotes (Wei et al., 2021). It has been demonstrated that marine natural bioproducts have potent antibacterial capabilities (El Samak et al., 2018). The bacterial strains, Bacillus megaterium, Vibrio sp., Dietzia sp., Bacillus marisflavi, Salinicoccus roses, Bacterium K54, and Ruegeria sp., were isolated from sponges—Echinodictyum sp., Spongia sp., Sigmadocia fibulatus, and Mycale mannarensis reported from the Gulf of Mannar have antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis. Bacillus subtilis, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio fortis, and Vibrio sp. also displayed action against Escherichia coli (Anand et al., 2006). Streptomyces sp. VITSTK7, isolated from marine soil sediment in Puducherry, Bay of Bengal, India, was reported to have moderate antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus cereus, and Klebsiella pneumonia (Thenmozhi and Kannabiran, 2012). Al-Dhabi-91 of Streptomyces parvus, isolated from the Saudi Arabian Sea, has antibacterial efficacy against the following clinical pathogens: S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia, and E. coli (Al-Dhabi et al., 2019). Pseudomonas mendocina, Bacillus spp., and Aeromonas-hydrophilized antimicrobial activity against Bacillus sp. was demonstrated. Staphylococcus aureus is susceptible to Aeromonas hydrophila M8 and Pseudomonas luteola M5 bacteria. Pseudomonas luteola M5 and Alcaligenes faecalis R2 isolated from Moroccan Atlantic Ocean coastal regions were reported to suppress Citrobacter freundii (El Amraoui et al., 2014).

4.1.2 Antifungal activity

Extremophilic marine microbes are reported to have pharmaceutical applications due to their antimicrobial properties. Streptomyces sp. ACT7 isolated from the East Coast Regions of the Bay of Bengal was reported to have antagonistic activity on phytopathogens, namely, Fusarium oxysporum and Alternaria sp (Thirumurugan et al., 2015). From Sanya, South China, the marine endophytic fungi of the sponge Axinella sp.—Eupenicillium sp.—is the source for curvularin and dehydrocurvularin, which have antifungal activity against Saccharomyces cerevisiae [minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) 375–750 g/mL] and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (MIC > 3,000 g/mL). The fungus Paraphaeosphaeria sp. strain N-119 is associated with the marine horse mussel Modiolus auriculatus obtained from Hedo Cape, Japan, inhibiting the growth of Neurospora crassa (Karpiński, 2019). The most notable strain of Streptomyces sp. ACT2 exhibits anti-dermatophytic activity against four pathogenic dermatophytes, including Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Epidermophyton floccosum, and Microsporum canis, which were isolated from mangrove estuaries in Tamil Nadu (Suresh et al., 2020). Culturable microorganisms (263) associated with marine sponges and coral mucus have potential antibiotic compounds that combat Candida albicans, which was reported from the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay (Rajasabapathy et al., 2020). Actinomycetes (M-20) isolated from Avicennia marina have antifungal activity and are reported from the backwater area, Ariyankuppam, Puducherry (Janaki et al., 2016). Nocardiopsis sp. VITSVK5 (FJ973467), a marine bacterium obtained from the Puducherry coast, shows antifungal effectiveness against Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, and Aspergillus niger (Vimal et al., 2009).

4.1.3 Anticancer activity

Applications of biotechnology on sustainability and human wellbeing are essential for the treatment of many deadly diseases, especially cancer. The discovery of novel drugs depends on the abundance of anticancer secondary metabolites synthesized by marine microbes. Salinosporamide A, a novel, long-lasting proteasome inhibitor derived from the marine bacterium Salinispora tropica, has begun phase I clinical trials. It is extremely effective against a variety of hematologic malignancies and solid tumor models, and it has a low level of cytotoxicity for normal cells (Khalifa et al., 2019). The South China Sea gorgonian, marine-derived fungus Penicillium oxalicum SCSGAF 0023, sourced from Muricella flexuosa, produces oxalicumone, exhibiting notable cytotoxicity with low IC50 values against SW-620 cell lines (Sun et al., 2013). The human gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 and the hepatic cancer cell line BEL-7404 were both adversely affected by AGI-B4, a cytotoxic compound from the marine fungus Neosartorya fischeri strain 1008F1 (Tan et al., 2012). A marine-derived A. fumigatus isolated from sea green algae in Seosaeng-myeon, Ulsan, Republic of Korea, is the source of isosclerone and is cytotoxic to MCF-7 human breast cancer cells (Li et al., 2014). The crude extract of Halomonas sulfitobacter isolated from the brine–seawater interface of the Red Sea showed activity against cancer (Sagar et al., 2013). An effective anticancer non-ribosomal peptide (NPR) thiocoraline is obtained from the marine bacteria Cromonospora marina (Al-Mestarihi et al., 2014).

4.2 Nutraceuticals

More than 650 novel ingestible marine compounds were reported from marine microorganisms and phytoplankton in 2003 alone. Biomolecules from marine microorganisms are useful for a number of purposes in the food industry, including the cost-effective production of food under specific conditions like high pressure or low temperature, adding nutritional value to the food, and using “natural” pigments, preservatives, or flavors (Rasmussen and Morrissey, 2007) (Table 4).

Table 4

| Marine microbial source | Active compounds | Nutraceutical applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Azotobacter vinelandii | Alginate | Stabilizers in the food industry | Khutoryanskiy and Georgiou (2018) |

| Vibrio sp., Pseudomonas stutzeri, Aeromonas sp., Cytophaga sp., Bacillus sp., Alteromonas sp., Pseudoalteromonas sp., Streptomyces sp., and Alteromonas agarlyticus GJ1B | Agarases | Food additive and solidifying agent | Beygmoradi and Homaei (2017) |

| Cellulomonas sp., Vibrio sp., Paenibacillus sp. BME-14, Clostridium sp., Nocardia sp., Streptomyces sp., Trichoderma sp., Aspergillus sp., Fusarium sp., Chaetomium sp., Phoma sp., Sporotrichum sp., and Penicillium sp. | Sucrose | Fiber supplement, calorie reducer and emulsifier | |

|

Streptomyces sp., Bacillus cereus MAB5 Beauveriabassiana (MSS18/41), Bacillus PG03, Bacillus PG02 and PG04, A. niger, A. oryzae, B. licheniformis, B. subtilis Cladosporium sp., Paenibacillus barengoltzii, and Thermococcus zilligii |

L-asparaginases | Food processing agent | Qeshmi et al. (2018) |

| Vibrio azureus strain JK-79 and Alcaligenes faecalis KLU102 | L Glutaminase | Diary industries | Toldra and Kim (2017) |

| Bacillus licheniformis KSAWD3 | Alcalase | Processing of soy meal, protein-fortified beverages | Barzkar et al. (2018) |

| Thermotoga maritima | Xylanase | Frozen partially baked bread | Jiang et al. (2018) |

| Kodamea ohmeri BG3 | Phytate | Human and animal diet improvement | Afinah et al. (2010) |

| Halomonas sp. strain AAD21 | α-Amylase | Starch processing | Uzyol et al. (2012) |

The nutraceutical potential of marine microbial life.

4.2.1 Lipid production

The growth of tissue membranes and cell components and metabolic energy all depend on lipids. They are essential to the physiology and reproduction of marine microorganisms and are a reflection of the particular biochemical and ecological circumstances that prevail in the ocean. Bacterial membranes, which act as a barrier between the bacteria and their surroundings, include membrane lipids. Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3, a marine bacterium, serves as the source of glutamine-containing amino lipids and fatty acids, essential constituents of the human body, and plays pivotal roles in metabolic, structural, and functional regulation. Thraustochytrids, a group of heterotrophic stramenopiles that belong to marine protists, a potential strain of labyrinthulomycetes, have a high concentration of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and glutamines, which are used as a nutritional supplement (Smith et al., 2019; Gupta et al., 2012). Marine yeast Aureobasidium pullulans YTP6-14 synthesized massoia lactones, known as lactonized hydroxy fatty acids are used in perfumes (Luepongpattana et al., 2017). Additionally, DHA is used in the commercial production of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which influences the assimilation of total fatty acid content (35%–40%) in Schizochytrium sp (Dewapriya and Kim, 2014). Leveraging inexpensive, natural substrates, marine yeast isolates, especially Candida sp., can accumulate significant lipids, providing an economical and environmentally beneficial production technique (Hassan et al., 2018). The growth and function of the brain and central nervous system are critically reliant on PUFAs. The massive quantity of PUFA is produced by the filamentous fungus Aspergillus terreus MTCC 6324, which was obtained from debris mangrove swamps (Khot et al., 2012). PUFA can be produced from bacterial species like Moritella marina, Vibrio marinus, and Shewanella marinintestina isolated from a low-temperature deep sea (Bellou et al., 2016). Phycomycetes are a prospective source of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LC-PUFA), which are used in the production of vegetable oils. Marine fungi belonging to the Mortierella genus, such as Mortierella alpina, M. elongata, M. ramanniana, and M. isabellina, are prolific producers of high quantities of gamma-linolenic acid, arachidonic acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) (Rasmussen and Morrissey, 2007). The majority of bacterial lipids is derived from model organisms, such as E. coli, which is mostly made up of glycerophospholipids, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, and a trace amount of cardiolipin (Smith et al., 2019). The omega-3 fatty acid, EPA, which is produced by the distinctive marine Gram-negative pleomorphic bacterium (SCRC2378) found in the intestine of Pacific mackerel, improves cardiovascular health (Adarme-Vega et al., 2014). A potential antibiotic named pontifactin, a serine-rich lipopeptide synthesized by the Flavobacterium pontibacter korlensis, was isolated from petroleum-contaminated seawater (Balan et al., 2016).

4.2.2 Enzyme production

Marine enzymes function under a wide range of conditions, including high-salt concentrations, varied temperature fluctuations, pH, organic solvents, surfactants, metal ions, and intense light and pressure exposure. The biofuel, chemical, pharmaceutical, and food industries have all made use of a number of exceptional biocatalysts derived from marine extremophiles. These enzymes, which are derived from marine organisms, continue to work under a variety of conditions, enhancing the efficiency and competitiveness of numerous industrial processes (Dalmaso et al., 2015). Marine microbes are excellent sources of L-asparaginase, which is used to reduce the level of acrylamide in cooked foods to ensure food safety. It is also used in the production of crispbread, French fries, and sliced potato chips by eliminating acrylamide. Food industries have already used Aspergillus spp. to reduce the amount of acrylamide in baked goods. Streptomyces sp. is a major source of L-asparaginase among marine microbes. Even Bacillus cereus MAB5 isolated from mangroves, marine Bacillus PG03, Bacillus PG02 and PG04, Bacillus licheniformis, and Bacillus subtilis synthesize L-asparaginase. Additionally, the marine fungus Beauveria bassiana (MSS18/41), Paenibacillus barengoltzii, Cladosporium sp., A. niger, Aspergillus oryzae, and Thermococcus zilligii were also sources of producing L-asparaginases (Qeshmi et al., 2018). Dairy companies use L-glutaminase isolated from the marine Vibrio azureus strain JK-79 and Alcaligenes faecalis KLU102 of the Bay of Bengal (Toldra and Kim, 2017). Alcalase, derived from B. licheniformis KSAWD3, is commonly employed in the food industry for processing soy meals, protein-fortified beverages, and various other applications (Barzkar et al., 2018). Aspergillus niger MTCC 1344, isolated from saltwater near Ismalia, Egypt, is the source of naringenin-enzymatic hydrolysis of naringinase. It plays a significant role in the production of food, fruit, and beverages (Shehata and Abd El Aty, 2014). The protease was isolated from the marine Aureobasidium pullulans HN2-3 and cloned into Yarrowia lipolytica to produce bioactive peptides. It is used in the food industry to improve the functionality and taste of cheese (Fernandes, 2014). Amylase obtained from Catenovulum sp. X3 (isolated from saltwater in Shantou, China), synthesized and cloned in Escherichia coli, is frequently applied in food industries as a sweetener. In addition to hydrolase, amylopectin, and amylose, this enzyme was isolated and used to create biohydrogen by starch saccharification (Wu et al., 2017).

4.2.3 Polysaccharide production

Microbial polysaccharides are a significant source of innovative biopolymers that can be employed to develop new functional foods and nutraceuticals because of their immune-stimulating and therapeutic properties (Giavasis, 2013). Microbacterium aurantiacum FSW25, isolated from Rasthakaadu Beach (Tamil Nadu, India), was found to synthesize an exopolysaccharide that had exceptional rheological and antioxidant properties, making it suitable for use as a viscous antioxidant across various industries (Sran et al., 2019). Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Azotobacter vinelandii, in conjunction with marine brown algae like Macrocystis pyrifera, Ascophyllum nodosum, Laminaria hyperborea, and Laminaria digitata, produce extracellular polyuronides akin to alginic acid. These substances serve as stabilizers for ice cream and cheese, as well as thickeners and emulsifiers in tomato juice and salad dressings (Khutoryanskiy and Georgiou, 2018). A marine bacterial strain Aerococcus uriaeequi HZ isolated from Rongcheng, Shandong Province, China, secretes exopolysaccharides (EPSs) that have high demand due to their significant role in food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and other applications (Wang et al., 2018). Marine-derived Bacillus, Halomonas, Planococcus, Enterobacter, Alteromonas, Rhodococcus, Zoogloea, and Cyanobacteria strains produce EPSs (Dewapriya and Kim, 2014). Agarases are primarily synthesized by marine bacteria and are essential for the food industry in the production of soft drinks and jellies, as well as being used as a food additive and hardening agent. Marine bacteria such as Vibrio sp., Pseudomonas stutzeri, Aeromonas sp., Cytophaga, Bacillus, Alteromonas, Pseudoalteromonas, Streptomyces, and Alteromonas agarlyticus GJ1B could produce agarases. Cellulomonas, Vibrio, Paenibacillus sp. BME-14, Clostridium, Nocardia, Streptomyces, Trichoderma, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Chaetomium, Sporotrichum, and Penicillium are among the marine bacteria that have the capability to synthesize cellulose. Cellulose is used in the food industry as an emulsifier, calorie reducer, and fiber supplement (Beygmoradi and Homaei, 2017). Extracellular amylase from marine yeast Aureobasidium pullulans N13d is used in the production of cakes, fruit juices, and starch syrups; in baking; and in brewing, as well as used as digestive aids (Zhang and Kim, 2012). Alteromonas strains produce polymers with strong metal-binding properties, good gelling capabilities, and considerable thickening agent characteristics (Rasmussen and Morrissey, 2007). Chondroitin sulfate (CS) saccharides produced by Arthrobacter sp. strain (MAT3885), reported from the coastal regions of Reykjanes, are sources of dietary supplements used to treat osteoarthritis (Kale et al., 2015).

4.2.4 Pigment production

Marine pigments have been receiving a lot of attention over the last few decades. They have evolved as substitutes in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries, replacing synthetic colors (Manochkumar et al., 2022). Carotenoids are the primary group of natural pigments that produce yellow, orange, red, and purple colorants. They are lipid-soluble, potentially biotechnological pigments that are derived from a variety of species, including plants, animals, and microbes (bacteria, fungi, yeasts, microalgae, and macroalgae) (Cardoso et al., 2017). The marine actinomycete Streptomyces sp. AQBMM35 synthesizes a colorless carotenoid called phytoene, which is used as a food additive (Dharmaraj et al., 2009). The marine bacteria Vibrio gazogenes produces the prodiginine pigment derived from prodigiosin, which is used to dye wool, silk, and synthetic fabrics like polyester and polyacrylic. It also has antibacterial properties against E. coli and S. aureus. The marine bacteria Paracoccus haeundaensis and Bacillus indicus HU36 produce carotenoids, which display combined effects in the suppression of linoleic acid peroxidation (Ye et al., 2019). A red pigment/carotene-producing yeast called Rhodotorula sp. RY1801 was found in the sediments of the South Yellow Sea in Dongtai City, Jiangsu Province, China (Zhao et al., 2019). The marine bacterium Brevundimonas sp. strain N-5 was found in Shimoda Port, Shizuoka Prefecture, on the Pacific coast of Middle Japan. When taken as a food supplement, astaxanthin can either prevent or lower the risk of a number of human illnesses (Asker, 2017). From the homogenate of the marine sponge Halicondria okada, a strain of the Rubritalea squalenifaciens bacterium (HOact23T) was isolated from the Miura Peninsula (Kanagawa, Japan). It synthesizes a yellow pigment called diapolycopenedioc acid (C30 carotenoid), which is used as an additive in food (Shindo and Misawa, 2014). Acroporano bilisdana 1846, marine bacterial strain 04OKA-13-27 (MBIC08261), identified in the hard coral region of Majyanohama, Okajima, and Kerama Islands in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan, produces the food coloring agent (3R)-saproxanthin (Shindo et al., 2007).

4.3 Cosmeceuticals

Synthetic cosmetics once dominated the market, but today, the demand for natural products in the cosmeceuticals sector is booming. In the recent past, marine microbe-derived products have gained importance due to their tremendous biological activities as compared with traditional synthetic cosmetics. For example, mycosporines and mycosporine-like amino acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and carotenoids derived from marine thraustochytrids are vital contributors to the cosmetics industry (Corinaldesi et al., 2017). Using chemically formulated cosmetics, toiletries, skincare products, and sunscreen can frequently harm the body. Recent reports revealed that an average adult uses nine cosmetic products, and one out of four women uses as many as 15 products (Nigam, 2009). Natural active substances, including vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, and enzymes used in cosmetics, are administered in a variety of skincare products (Siahaan et al., 2017). Under the brand name Abyssine®, exopolysaccharides derived from the marine bacteria Alteromonas macleodii are sold commercially to lessen the inflammation of sensitive skin brought on by UVB, mechanical, and chemical aggression (Guillerme et al., 2017). A polysaccharide mixture produced by Pseudoalteromonas sp., isolated from Antarctic waters, has anti-aging properties (Martins et al., 2014). Vibrio diabolicus is a polysaccharide-secreting marine bacteria isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent producing exopolysaccharide HE 800 that provokes collagen, contributing to skin structural properties (Courtois et al., 2014). A natural compound, ectoine, was first extracted from Ectothiorhodospira halochloris, which is proficient in hydrating the surface layers of the skin and protecting the outermost layers from dehydration (Bownik and Stępniewska, 2016; Kunte et al., 2014). It also cures skin inflammation and treats moderate atopic dermatitis (Marini et al., 2014). A patent was filed in the USA (U.S. patent 20140056834A1) for chrysophanol, which is an effective skin-whitening agent produced by the fungus Microsporum sp. associated with marine algae (MFS-YL) (Corinaldesi et al., 2017). The actinomycete Nocardiopsis dassonvillei, associated with the sea sponge Dendrilla nigra, is the source of ethyl oleate. It is a fatty acid ester that has multiple applications in cosmetic products that soften and perfume the skin (Thomas et al., 2010). Cosmetics have been utilized for aesthetic, beautification, protection, purification, and ceremonial purposes by several civilizations. Alteromonas macleodii ssp. fijiensis biovar deepsane, a deep-sea ecotype exopolysaccharide-producing bacterium, produces HYD657, which is used in cosmetic production (Poli et al., 2010). The Flavobacteria strain SM1127, isolated from Arctic brown alga Laminaria sp., synthesizes high exopolysaccharide, a moisturizing agent that has high water-retention capacity used in the cosmetics industry (Vilchez et al., 2011). Marine fungal species like Rhodotorula, Phaffia, and Xanthophyllomyces are essential sources of carotenoids and have considerable anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that help protect the skin from ultraviolet radiation (Saha and Ahmad, 2024). Two new compounds, Z233 derived from Sargassum horneri algae and two derivatives from Pestalotiopsis sp., have been identified as tyrosinase suppressors. These compounds are valuable for skin whitening and treating dermatological issues (Wu et al., 2013). However, it continues to be difficult to bring such marine-derived bioactive chemicals into commercial formulations because cosmetic production generally requires sustainability, especially regarding manufacturing capacity, toxicity, revenue potential, and waste generation. The Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) and the Fair Packaging and Labelling Act (FPLA) are two significant US regulations pertaining to cosmetic items that are overseen by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Every cosmetic product must include a Cosmetic Product Safety Report (CPSR), which is part of the Product Information File (PIF) (Fonseca et al., 2023).

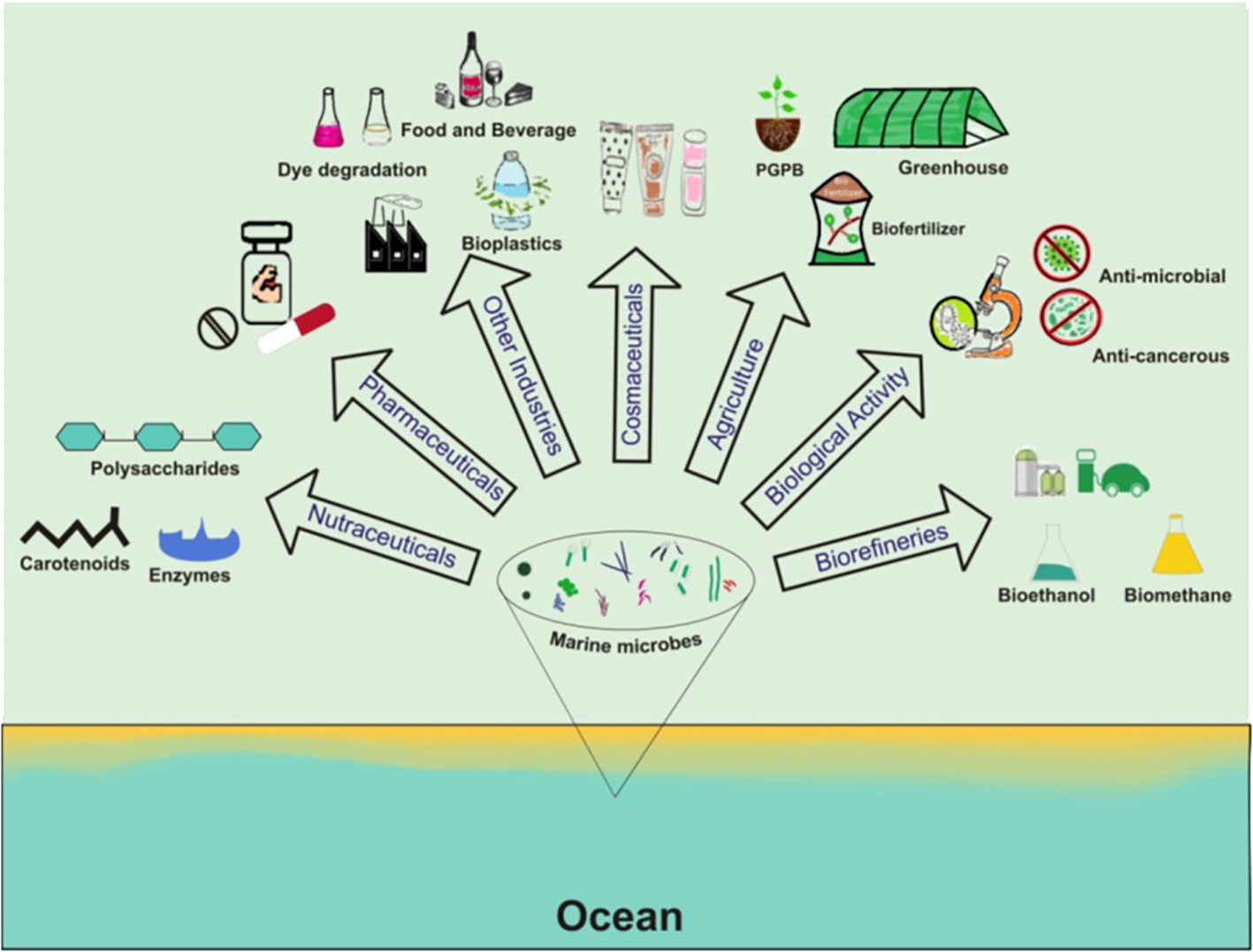

4.4 Environmental biotechnology applications

Countries around the world are likely to encounter a significant energy crisis as fossil fuel resources become depleted, prompting them to seek alternative renewable and sustainable energy sources. Marine microbes not only serve as an alternative source of energy but also reduce harmful greenhouse gases to balance political and economic issues (Madhavan et al., 2017). They produce a wide range of chemicals with enormous biotechnological potential, including lipids, fatty acids, carotenoids, and biofuels. With the potential to produce up to 40 times more crude oil per acre than terrestrial plants, marine microalgae in particular are intriguing third-generation biofuel sources. As illustrated in Figure 4, marine microbes contribute significantly to multiple industries, including the production of polysaccharides, carotenoids, enzymes, pharmaceuticals, bioplastics, biofertilizers, bioethanol, biomethane, and more, showcasing their multifaceted biotechnological potential.

Figure 4

Unveiling the versatility of marine microorganisms: applications across diverse fields.

Microbial lipid-derived biodiesel is low in sulfur, biodegradable, and compatible with current turbines (Knothe, 2011). Marine bacteria, such as Rhodococcus species, and microalgae, such as Chlorella, Tetraselmis, Isochrysis, and Scenedesmus, are effective lipid producers for the synthesis of biodiesel (Gupta et al., 2013). Marine microalgae are the major source of the production of biofuels because they are generally grown in open or covered ponds or closed PBRs with sunshine. The cell walls of microalgal biomass and marine bacteria with cellulolytic sources were isolated from the guts of filtering bivalve molluscs and used for the production of biogas. The R. ornithinolytica cellulolytic bacterial strains MA5 or MC3, pretreated with microalgal biomass, boosted methane production. Consequently, “whole-cell” cellulolytic pretreatment can improve the effectiveness and efficiency of biogas production (Munoz et al., 2014). Additionally, methanogenic consortia of Methanosarcina, Methanogenium, and Methanoplanus species that efficiently transform waste into biomethane are supported by marine organic waste (Quinn et al., 2016). Beneath anaerobic or phototrophic circumstances, marine bacteria such as Clostridium, Citrobacter, Ectothiorhodospira, and Rhodovulum generate iohydrogen, an environmentally friendly, zero-carbon energy source (Cai et al., 2012). When produced in E. coli, recombinant strains like Catenovulum sp. X3 have shown increased hydrogen yields (Wu et al., 2017). Marine yeasts and fungi can ferment carbohydrates from algae and plant biomass to produce bioethanol. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Zygosaccharomyces rouxii hybrids are halotolerant strains, demonstrating greater ethanol tolerance and yield (Soccol et al., 2010). The marine yeasts Candida and Debaryomyces effectively ferment sugars in saline media, and the marine microalgae like Spirogyra and Chlorococum can produce up to 15,000 L of ethanol per acre yearly (Harun et al., 2010). Furthermore, marine life forms make bioplastics, reducing plastic pollution worldwide. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) and polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), biodegradable thermoplastic polymers with commercial applications, are produced by Bacillus megaterium, Halomonas campaniensis, Cupriavidus spp., and Haloferax mediterranei (Możejko-Ciesielska and Kiewisz, 2016; Kavitha et al., 2018). At low-nutrient settings, a variety of halophilic and deep-sea bacteria, such as Colwellia, Moritella, Shewanella, and haloarchaeal taxa (Haloarcula, Halobacterium, Haloferax mediterranei), accumulate PHAs, indicating their potential for large-scale bioplastic synthesis (Ahuja et al., 2024). Furthermore, marine extremophiles have exceptional dye-degrading characteristics that reduce pollution from textile effluents. Synthetic dyes like methylene blue, Congo red, and Reactive Blue 4 are efficiently broken down by enzymes like laccases and azo-reductases from marine species, namely, Oscillatoria curviceps, Flavodon flavus, Cerrena unicolor, and Phlebia sp (Theerachat et al., 2019; Ghosh et al., 2020). Marine Shewanella marisflavi acts as a halotolerant exoelectrogenic decolorizer capable of degrading dyes such as Xylidine Ponceau 2R (Xu et al., 2016).

Also, marine microbial consortia are efficient in the bioremediation of oil spills by using surface-active and exopolysaccharide-producing bacteria to break down hydrocarbons. Marine bacteria, namely, Alcanivorax, Cycloclasticus, Marinobacter, Neptunomonas oleiphilus, and Oleispira, effectively degrade petroleum hydrocarbons by continuously fermenting either individually or in consortia (Al-Hawash et al., 2018). Exopolysaccharides produced by marine microbes like Alteromonas and Pseudoalteromonas are direct evidence of hydrocarbon degradation in the marine environment (Gutierrez et al., 2018). The marine genera Oceanospirillales, Colwellia, Cycloclasticus, and Alcanivorax borkumensis, crucial in bioremediating oil spills, are sources of potentially bioactive substances (Bollinger et al., 2020). Pseudomonas putida, Bacillus thuringiensis, and Enterobacter cloacae from marine origin accomplish heavy metal detoxification by biosorption, bioprecipitation, and bioaccumulation. Zunongwangia profunda exopolysaccharides can remediate wastewater as they have a strong metal-binding affinity for Cu²+ and Cd²+ (Sun et al., 2015). These environmentally friendly techniques are substitutes for traditional physicochemical approaches to hazardous management (Ameen et al., 2020) (Table 5).

Table 5

| Heavy metal and dyes | Marine microbial source | Geographical location | Mechanism of action | Heavy metal removal capacity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hg | Bacillus thuringiensis PW-05 | Odisha coast | Cellular chelation | 50 mg L−1 HgCl2 | Dash & Das (2016) |

| Cr |

Bacillus sp., MTCC 5514 |

Tamil Nadu, Bay of Bengal, India | Biosurfactant | 2000 mg L−1 Cr (VI) | Gnanamani et al. (2010) |

| Cd |

Rhodopseudomonas

palustris TN110 |

Saline paddy field, South Thailand | Bioprecipitation | 0.2 mM CdCl2 | Sakpirom et al. (2019) |

| Cu | Ceratoneis closterium, Phaeodactyum tricornutum, and Tetraselmis sp. | Australian National Algal Culture Collection, CSIRO | Intracellular uptake | 8 to 47 μg Cu/L | Adams et al. (2016) |

| Direct blue 2B | Pseudomonas sp. | Mangrove sediments | Degradation | 500 ppm—9.03% | Raja et al. (2013) |

| Congo Red, Methylene Blue, Trypan Blue, and Aniline Blue |

Marine fungus NIOCC 2a | Chorao Island in Goa | Degradation | 0.02% > 0.04% | D’Souza-Ticlo et al. (2009) |

| Congo red-21 | Streptomyces sviceus | Bay of Bengal coastline of Nellore district | Dye degradation | 70% of decolorization at 96 h | Ghosh et al. (2020) |

| Bioplastics | Pseudodonghicolaxia menensis | Red Sea, Saudi Arabia |

Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) production | 0.162 g/L/h | Mostafa et al. (2020) |

| Polyester |

Chlorella sp., Oscillatoria salina, Leptolyngbya valderiana, and Synechococcus elongates |

National Repository for Microalgae (NRMC), Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu | Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production | PHA produced 0.32 g/L, 0.99 g/L, 2.74 g/L, and 2.74 g/L | Roja et al. (2019) |

Marine microbes’ pioneering role in environmental restoration.

4.5 Agricultural biotechnology applications

People need to have access to safe food because of population expansion. Inorganic fertilizers with a high potassium, nitrate, ammonium, and potassium content are used to ensure crop protection and increase productivity. In the global context, agricultural runoff due to inorganic fertilizers poses a serious threat, which leads to eutrophication in freshwater and marine ecosystems (Huang et al., 2017). Eutrophication-induced algal bloom is detrimental to our ecosystem, human health, and recreational opportunities, which is reported in the United States, Japan, the Black Sea, and Chinese coastal areas (Ngatia et al., 2019). Biofertilizers are formulations of microorganisms, including beneficial bacteria, fungi, and microalgae, designed to enhance soil microbiology and improve nutrient availability, ultimately increasing crop yield. These technologies offer cost-effective solutions for sustainable agriculture (Lucena Cavalcante et al., 2012). Nitrogen is crucial for plant growth, and nitrogen-rich microbiomes, such as those containing Azotobacter and Azospirillum, enhance nitrogenase activity. This makes them valuable biofertilizers for improving mangrove restoration efforts, as observed in the Indian mangrove forest of Pichavaram, where they aid in the restoration of Avicennia marina (Baskar and Prabakaran, 2015). Ten phosphate-solubilizing fungus genera, namely, Aspergillus, Verticillium, and Nigrospora, were reported from the Muthupet Mangrove Reserve. Among these, A. niger and A. flavus had the most notable characteristics for solubilizing phosphate, and they greatly improved soil fertility and plant growth as well (Arulselvi et al., 2018). On the southeast coast of India, soil samples from a mangrove ecosystem had significant amounts of Azotobacter and heterotrophic bacteria that fix nitrogen at high rates. Acinetobacter beijerinckii, A. chroococcum, and A. virelandii novel species were reported for their rapid growth rate and nitrogen fixation (Ravikumar et al., 2004). Anabaena sp., symbiotic cyanobacteria known as Anabaena azollae, and Nostoc cicadas exhibited strong nitrogenase activity in marine environments (Kumar et al., 2019) (Table 6). Microbes aid in the growth of plants and protect them against disease and abiotic challenges through a variety of activities. Indole acetic acid is a key plant growth regulator that promotes a number of development and proliferation processes, including cell division, elongation, tissue differentiation, apical dominance, and defense against pathogens, light, and gravity. An endophytic Bacillus strain was isolated from a marine green alga, Ulva lactuca, effectively inducing plant growth and resistance against plant pathogens (Nair et al., 2016). The marine bacterium Pseudomonas spp. enhanced fresh and dry biomass (Goswami et al., 2015). Kocuria flava and Bacillus vietnamensis, two halophilic mangrove rhizospheric bacterial strains isolated from Sundarban, enhanced the yield of paddy plants (Mallick et al., 2018). The plant height has been influenced by marine microbial strains such as Azospirillum halopraeferens, A. brasilense, Vibrio aestuarianus, V. proteolytic, Bacillus licheniformis, and Phyllobacterium sp (Bashan et al., 2000). A biocontrol agent, Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain obtained from the Gulf of Khambhat, impacted and promoted plant growth (Goswami et al., 2015). The effective plant growth-promoting activity of Spirulina platensis was reported in Zea mays L (Sampathkumar et al., 2019).

Table 6

| Microbial source | Geographical location | Role in agriculture | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina platensis | CAS in Marine Biology, Faculty of Marine Sciences, Annamalai University, Tamil Nadu, India | Biofertilizer | Sampathkumar et al. (2019) |

| Isochrysis galbana | Marine Biotechnology Division, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), Cochin (Kerala, India) | Plant growth promoter | Sandhya and Vijayan (2019) |

| S. platensis, C. vulgaris | Marine environment | Biofertilizer | Dineshkumar et al. (2020) |

| Rhizobium sp. and Pseudomonas sp. | Rhizosphere and nodules of mung bean from salt-affected fields | Plant growth promoter | Ahmad et al. (2013) |

| Aspergillus niger and A. flavus | Muthupet mangroves | Biofertilizer | Arulselvi et al. (2018) |

| Anabaena azollae and Nostoc cycadales | Marine basins | Biofertilizer | Kumar et al. (2019) |

| Halotolerant marine bacterial strains AMETH101 to AMETH292 | Kelambakkam to Marakanam | Plant growth promoters | Vinothini et al. (2014) |

| Halotolerant rhizobacterial (HTRB) strains, AMET7041 | Department of Biotechnology, AMET University, Chennai | Plant growth promoters | Jayaprakashvel et al. (2014) |

Impact of marine microbes on agricultural advancement.

5 Marine model organisms boosting the bioeconomy

The richness of natural components and evolutionary lineages found in marine microbial communities makes them an untapped source of bioresources that can boost and support the economy. The synthesis of bioactive compounds containing unusual functional groups such as isocyanate, dichloramine, isonitrile, and halogenated functional groups can be influenced by marine abiotic parameters like osmolarity, pH, and temperature variations. Next-generation sequencing methods have revolutionized the identification of previously overlooked microbes from different environments, giving us greater access to potentially useful bioactive compounds. This expands the potential of microbial resources and has implications for the development of the bioeconomy (Pandey and Singhal, 2021). Two suitable methods, shotgun metagenomics and amplicon-based metagenomics, have been used to comprehend different facets of the microbiome. The Sorcerer II (2003–2010), the Malaspina (2010–2011), and the Tara Oceans (2010–2011) were extensive explorations to investigate the diverse marine habitats by metagenomics methods planned in the past 10 years (2009–2013). From metagenomic sampling, the TARA Ocean expedition showed the depth of microbial diversity and anticipated upwards of 40 million unique genes (Pesant et al., 2015). The metagenome investigations featured 8,000 high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), revealing three unique uncultured archaeal phyla (UAP), the superphylum Asgard, and 17 unique uncultured bacterial phyla (UBP) (Lapidus and Korobeynikov, 2021). The discovery of marine natural products (MNPs) increased most quickly between the 1970s and 1980s, when there was a 305% rise in the number of novel marine molecules. The vast majority of MNPs were obtained from marine microbes, predominantly bacteria (Carroll et al., 2019). Pharmaceuticals and biomaterials derived from marine sources, such as analgesics, antibacterials, and cancer therapies, are already on the market. At least 25 marine compounds were under investigation as potential novel medications (Calado et al., 2018). Most of the MNPs were obtained from the following genera: Aspergillus (708), Laurencia (593), Sinularia, and Streptomyces (593) (Blunt and Munro, 2017). One of the nucleosides, vidarabine, obtained from Streptomyces antibioticus, possesses anticancer and antiviral properties to treat herpes virus, poxvirus, rhabdovirus, hepadnavirus, RNA tumor virus, and ophthalmologic issues (Mayer et al., 2010). Marine microalgae are being used in the food sector due to their rich sources of nutrients like beta-carotene; vitamins C, A, E, and H; complex B; astaxanthin; polysaccharides; and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lonza Group—Switzerland has been extracting the microalgal oil docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) from Ulkenia sp. Pharmaceutical-grade EPA oil is extracted from Nitzschia laevis diatoms by Photonz Corp., New Zealand (Lee et al., 2011). Bioactive metabolites derived from marine microalgae have demonstrated greater antioxidant efficacies compared to commercially available products (Wang et al., 2025). Carotenoids from marine microalgae are utilized in cosmetics, medications, food coloring, and feed additives. The market value was estimated at US $1.45 billion in 2019 and is projected to reach US $2.04 billion by 2025, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.75% (Barros de Medeiros et al., 2022). The consumption of omega-3 dietary supplements in Australia has surged by 10% annually, reaching a value of $200 million. In the US alone, it amounted to $2.49 billion in 2019. This figure is expected to grow at a CAGR of 7% from 2020 to 2027 (Oliver et al., 2020). Ocean-related economic activity is expected to quadruple in 20 years, from USD 1.5 trillion in 2010 to USD 3 trillion by 2030 (OECD, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), a figure equal to the GDP of France in 2020 (OECD, 2016). The EU’s blue biotechnology market achieved a gross value added (GVA) of €327 million in 2022, with turnover reaching €942 million, as reported in the EU Blue Economy Report (European Commission, 2023). Marine microorganisms are also a significant source for cosmeceutical industries because of their antioxidant properties, anti-ultraviolet protection, and anti-aging properties. Bacterial and yeast extracts are used in 78% of new products in the face and neck therapeutic category. Cosmeceutical product usage increased at a rate of 4.5% annually between 2010 and 2015. Unipex made a successful introduction of Abyssine®, one of the pioneering specialty substances derived from Alteromonas macleodii sp. fijiensis, into the cosmetic market. Marine-inspired biomaterials, such as water-resistant adhesives and environmentally friendly antifouling agents, are also advantageous to the robust industry since they prolong the life of maritime infrastructures and protect commercial vessels’ hydrodynamic performance. Potential options for low-cost biodiesel and biomass scaling up are marine algae and yeasts (Vieira et al., 2020). Innovative techniques, including lab-on-a-chip, microfluidic, and tiny next-generation sequencing (NGS), are opening the door to deeper and more extensive oceanic exploration, which plays a major role in the bioeconomy. Blue biotechnology is helping to uncover the “blue gold”: the untapped biological richness of the world’s seas by making sample collection easier and enabling specimens acquired under difficult deep-sea conditions to develop both onboard and in laboratory techniques. Blue biotechnology is an emerging sector poised to transform the bioeconomy and act as a robust toolkit for delivering innovative solutions to address various challenges. By collaborating with value chain partners, new applications of blue bioresources and biotechnological products have been developed to drive innovation and promote new circular business models. The development of marine natural products is an emerging research area with abundant commercial and societal benefits. Globally, numerous organizations and industries are working to introduce new bioactive ingredients from marine sources to the market. The majority of authorized medications derived from marine sources are anticancer; nevertheless, they act in multiple mechanisms. The drug HALAVEN®, based on spongonucleosides, functions as an antimetabolite and inhibits microtubules; trabectedin (YONDELIS®) and lurbinectedin (ZEPZELCA™) are DNA alkylating agents; antibody–drug conjugates (ADCETRIS®, POLIVY™) selectively deliver MMAE to cancer cells; and plitidepsin (APLIDIN®) inhibits protein recycling through eEF1A2 (Haque et al., 2022). Anticancer, antibacterial, and analgesic medications are only a few examples of the pharmaceuticals with marine inspiration that are already on the market (Figure 5). Leveraging these developments, systems biology, bioinformatics, and artificial intelligence are rapidly propelling innovation in marine biotechnology by facilitating quicker and more thorough investigation of marine biological resources. Researchers may determine biosynthetic channels, estimate enzyme roles, and create targeted probes using programs like BRENDA, BLAST, and Clustal Omega (Liguori et al., 2020). By incorporating various ocean state variables into 3D analytical platforms, AI-driven methods are revolutionizing the interpretation of marine data and facilitating the effective management and visualization of intricate data. Capitalizing on this, scientists have created all-season convolutional neural network (A-CNN) models capable of deciphering complex marine and environmental patterns that support biotechnological discovery (Ham et al., 2021).

Figure 5

Discovery of the potential of marine microbial natural products.

6 Conservation of marine microbes

According to the WFCC World Data Centre on Microorganisms, more than 600 microbial repositories were registered in 68 countries; India alone has 32 microbial collection repositories. With a maximum of nine cultural collections, the state of Maharashtra came out on top. Ex situ conservation is a technique that is often employed in culture collection centers to conserve germplasm and would provide efficient, genetically stable cultures for sustainable applications (Winters and Winn, 2010). The scientific infrastructure and microbial resource centers (MRCs) are crucial for promoting the conservation of microbial resources and enabling breakthroughs in biotechnology, agriculture, and education. MRCs are the key players in selecting, acquiring, systematizing, maintaining, and granting access to microbiological resources in order to provide information (Sahin, 2006). The MRC network was established in 1974 by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), UNESCO, and the International Cell Research Organization (ICRO). This network intends to conserve and use microbial gene pools, make them accessible to underdeveloped countries, and enhance environmental microbiology and biotechnology research. Conservation supports a better understanding of microbial systematics and physiology of novel strains. Authorized microbial strains and their genomic DNA are transmitted with quality control assurance. The efficient and methodical operation of microbial resource centers lays the foundation for microbial taxonomy by facilitating new avenues in microbiological research (Overmann, 2015). Ex situ conservation techniques include repeated subcultivation, freezing at extremely low temperatures, preservation on agar beads at 50°C, cryopreservation, gelatin discs, and lyophilization (freeze-drying) (Sharma et al., 2017). Despite all of these techniques, cryopreservation and lyophilization are extensively used for culture collections (Wowk, 2007). MRCs maintain comprehensive databases to provide access to information on cultures, their typical characteristics, literature, and DNA arrays. Important cultures derived from research are accessioned, inspected, and conserved (Sly, 2010). For marine cyanobacteria and microalgae, the DBT, Government of India, financed the establishment of the National Facility for Marine Cyanobacteria (NFMC) & National Repository for Freshwater Microalgae & Cyanobacteria at Bharathidasan University in Thirichirapalli, Tamil Nadu, India. For many years, microbes have gained a well-known reputation as potential treasure troves for a variety of purposes. Although there are countless facts concerning how well bacteria function in the ecosystem, they are largely ignored and are not taken into account in conservation biology. In order to protect vulnerable microbial species, their habitats, and their importance in taxonomy exploration training, research activities should prioritize conservation by recognizing MRCs with financial aid.

7 State of the art and emerging directions

Multi-omics-powered research platforms have replaced traditional culture-dependent screening in marine microbial bioprospecting over the last 70 years. A large reservoir of cryptic BGCs has been discovered by the development of genome and metagenome mining; plenty of these BGCs contain novel bioactive compounds that have not yet been produced in a lab setting. The examination of metabolic pathways, resistance mechanisms, and enzyme functionalities associated with pharmacological and biological uses is further made possible by comparative and functional metagenomics. Leveraging on these metagenomic breakthroughs, new prioritization frameworks guided by AI and machine learning anticipate bioactivity and biosynthetic potential from genomic data, considerably accelerating the selection of significant compounds. All these developments have made research on marine microbial diversity a more foreseeable and data-focused field, thereby providing the rationale for structuring this review around the transition from conventional techniques toward more innovative computational and system-wide methods.

Omics-driven bioprospecting acceleration: By uncovering cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters and establishing a large-scale connection between genotype and metabolite output, integrating genomes, metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics will further broaden the discovery pipeline (Moutinho Cabral et al., 2024).

AI-based metabolite prediction: In order to determine bioactivity, locate biosynthetic gene clusters, and find new compounds from unexplored habitats, AI-driven technologies may incorporate data from multiple domains, including genomics, metabolomics, and cheminformatics (Medema and Fischbach, 2015).

Sustainable marine cultivation and upscaling: Advancements in customized bioreactor designs, ideal seawater medium, and engineered consortia techniques will minimize ecological strain on natural supplies while enabling low-impact, global production of marine proteins (Yin et al., 2025).

Regulatory harmonization and IP sharing: To establish uniform standards for marine biotechnology and guarantee equitable cooperation between nations, regulatory harmonization is crucial. To ensure that marine genetic resources are managed responsibly and benefits are distributed equitably, transparent and equitable IP-sharing procedures that are governed by frameworks such as the Nagoya Protocol are equally crucial (Roca, 2021).

Key impediments still exist despite advancements in omics-driven research: many marine microorganisms continue to remain unculturable, and biosynthetic gene clusters are nevertheless unidentified or cryptic, which restricts their biotechnological exploitation.

8 Conclusion and future perspectives

The current review compiles the immense potential of marine microbes and their paramount applications in various sectors. The exploration of innovative oceanic products, which have enormous industrial applications, stands out as a particularly captivating avenue within contemporary marine science. The constant demand for novel drugs from natural sources demands the requirement for a significant number of discoveries from marine microorganisms. However, most of these microorganisms have not yet been cultured, and therefore, more rigorous efforts are required to culture these microorganisms to explore their potential for various secondary metabolites. Only a few culturable microbes (1%), which produced a number of useful commercial products, were the focus of scientific research over the past 50 years. However, the remaining uncultured microbes (99%) have a wide range of potential applications for keeping an eco-friendly environment and improving human welfare. A plethora of such marine microbes and their molecules can be discovered by various modern biotechnological methods. A significant advancement in this field is the emergence of metagenomics, a novel methodology for examining microorganisms directly from their natural environments. This approach employs functional gene screening and sequencing analysis to explore various aspects, including microbial diversity, community composition, genetic and evolutionary linkages, functional dynamics, and the complex interactions and relationships these microorganisms establish within their environment. The ultimate aim for safeguarding marine microbial diversity is the stability of bioactive compounds from these organisms, which is valuable and preferred in various industrial applications.

Despite these developments, important obstacles still remain. Massive marine ecosystems are still unexplored, and research is often biased toward certain regions. Broad comparisons are hampered by the limitations of metagenomic datasets, which are frequently caused by inconsistent methodology and insufficient sampling. For a comprehensive understanding of marine microbial diversity and its sustainable biotechnological potential, such challenges must be surmounted by parallel sampling, international collaboration, and integrated multi-omics techniques. Owing to the remarkable development of metagenomics and bioinformatics, the scientific community can now investigate and comprehend the vast metabolic potential hidden in marine microorganisms. These approaches make it achievable to identify and characterize biosynthetic gene clusters that produce novel metabolites. It also speeds up the research for potentially bioactive compounds and delivers fascinating insights about the evolutionary processes and ecological functions of these metabolites in marine environments.

Statements

Author contributions

CV: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. NN: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft. KN: Writing – original draft. MS: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. RV: Writing – original draft. RZ: Writing – original draft. SP: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. RC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis, Validation, Conceptualization, Investigation. AS: Formal Analysis, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. KT: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision, Formal Analysis, Validation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The authors are grateful to Vellore Institute of Technology for their constant support and encouragement. Prof. C. Rajasekaran and Dr. T. Kalaivani acknowledge DST – SPLICE – Climate Change Program, Govt. of India (grant no. DST/CCP/NCC&CV/133/2017 (G)), for supporting Ms. V. Chandra, Mr. N. Nagaraj, and Mr. S. Manoj. We are grateful to Dr. Swapnil Kajale for generating the figures. Dr. Avinash Sharma acknowledges the support of the DBT/Wellcome Trust, India Alliance under the project grant (IA/E/17/1/503700).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adarme-Vega T. C. Thomas-Hall S. R. Schenk P. M. (2014). Towards sustainable sources for omega-3 fatty acids production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.26, 14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.08.003

2

Adams M. S. Dillon C. T. Vogt S. Lai B. Stauber J. Jolley D. F. (2016). Copper uptake, intracellular localization, and speciation in marine microalgae measured by synchrotron radiation X-ray fluorescence and absorption microspectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol.50, 8827–8839.

3

Afinah S. Yazid A. M. Anis Shobirin M. H. Shuhaimi M. (2010). Phytase: Application in food industry. Int. Food Res. J.17, 13–21.

4

Ahmad M. Zahir Z. A. Nadeem S. M. Nazli F. Jamil M. Khalid M. (2013). Field evaluation of Rhizobium and Pseudomonas strains to improve growth, nodulation, and yield of mung bean under salt-affected conditions. Soil Environ.32, 158–166.

5

Ahuja V. Singh P. K. Mahata C. Jeon J. M. Kumar G. Yang Y. H. et al . (2024). A review on microbes mediated resource recovery and bioplastic (polyhydroxyalkanoates) production from wastewater. Microbial Cell Factories23, 187. doi: 10.1186/s12934-024-02430-0

6

Al-Dhabi N. A. Ghilan A. K. Esmail G. A. Arasu M. V. Duraipandiyan V. Ponmurugan K. (2019). Environmental-friendly synthesis of silver nanomaterials from the promising Streptomyces parvus strain Al-Dhabi-91 recovered from the Saudi Arabian marine regions for antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol.1, 111529. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111529

7

Al-Hawash A. B. Dragh M. A. Li S. Alhujaily A. Abbood H. A. Zhang X. et al . (2018). Principles of microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons in the environment. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res.44, 71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejar.2018.06.001

8

Al-Mestarihi A. H. Villamizar G. Fernández J. Zolova O. E. Lombó F. Garneau-Tsodikova S. (2014). Adenylation and S-methylation of cysteine by the bifunctional enzyme TioN in thiocoraline biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc136, 17350–17354. doi: 10.1021/ja510489j

9

Ameen F. A. Hamdan A. M. El-Naggar M. Y. (2020). Assessment of the heavy metal bioremediation efficiency of the novel marine lactic acid bacterium, Lactobacillus plantarum MF042018. Sci. Rep.10, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57210-3

10

Anand T. P. Bhat A. W. Shouche Y. S. Roy U. Siddharth J. Sarma S. P. (2006). Antimicrobial activity of marine bacteria associated with sponges from the waters off the coast of South East India. Microbiol. Res.161, 252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2005.09.002

11

Andryukov B. G. Mikhaylov V. V. Besednova N. N. Zaporozhets T. S. Bynina M. P. Matosova E. V. (2018). The bacteriocinogenic potential of marine microorganisms. Russ. J. Mar. Biol.44, 433–441. doi: 10.1134/S1063074018060020

12

Arulselvi T. Kanimozhi G. Panneerselvam A. (2018). Isolation and characterization of phosphate-solubilizing fungi from the soil sample of Muthupet mangroves. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol.4, 30–37.

13

Asker D. (2017). Isolation and characterization of a novel, highly selective astaxanthin-producing marine bacterium. J. Agric. Food Chem.65, 9101–9109. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b03556

14

Balan S. S. Kumar C. G. Jayalakshmi S. (2016). Pontifactin, a new lipopeptide biosurfactant produced by a marine Pontibacter korlensis strain SBK-47: Purification, characterization and its biological evaluation. Process Biochem.51, 2198–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2016.09.009

15

Barros de Medeiros V. da Costa W. K. da Silva R. T. Pimentel T. C. Magnani M. (2022). Microalgae as a source of functional ingredients in new-generation foods: Challenges, technological effects, biological activity, and regulatory issues. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.62, 4929–4950. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1879729

16

Barzkar N. Homaei A. Hemmati R. Patel S. (2018). Thermostable marine microbial proteases for industrial applications: scopes and risks. Extremophiles.22, 335–346. doi: 10.1007/s00792-018-1009-8

17

Bashan Y. Moreno M. Troyo E. (2000). Growth promotion of the seawater-irrigated oilseed halophyte Salicornia bigelovii inoculated with mangrove rhizosphere bacteria and halotolerant Azospirillum spp. Biol. Fertil. Soils32, 265–272. doi: 10.1007/s003740000246

18

Baskar B. Prabakaran P. (2015). Assessment of nitrogen-fixing bacterial community present in the rhizosphere of Avicennia marina. Indian J. Mar. Sci.44, 318–322.

19

Bellou S. Triantaphyllidou I. E. Aggeli D. Elazzazy A. M. Baeshen M. N. Aggelis G. (2016). Microbial oils as food additives: Recent approaches for improving microbial oil production and its polyunsaturated fatty acid content. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.37, 24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.09.005

20

Beygmoradi A. Homaei A. (2017). Marine microbes as a valuable resource for brand-new industrial biocatalysts. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol.11, 131–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2017.06.013

21

Blunt J. Munro M. (2017). MarinLit: A database of the marine natural products literature (Christchurch: University of Canterbury).

22

Blunt J. W. Carroll A. R. Copp B. R. Davis R. A. Keyzers R. A. Prinsep M. R. (2018). Marine natural products. Natural product Rep.35, 8–53. doi: 10.1039/C7NP00052A

23

Bollinger A. Thies S. Katzke N. Jaeger K. E. (2020). The biotechnological potential of marine bacteria in the novel lineage of Pseudomonas pertucinogena. Microb. Biotechnol.13, 19–31. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13288

24

Bownik A. Stępniewska Z. (2016). Ectoine as a promising protective agent in humans and animals. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol.67, 260–264. doi: 10.1515/aiht-2016-67-2837

25

Cai J. Wang G. Pan G. (2012). Hydrogen production from butyrate by a marine mixed phototrophic bacterial consortium. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy37, 4057–4067. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.11.101

26

Calado R. Leal M. C. Gaspar H. Santos S. Marques A. Nunes M. L. et al . (2018). “ How to succeed in marketing marine natural products for nutraceutical, pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical markets,” in Grand Challenges in Marine Biotechnology, Basel: Springer317–403.

27

Canganella F. Wiegel J. (2011). Extremophiles: from abyssal to terrestrial ecosystems and possibly beyond. Naturwissenschaften98, 253–279. doi: 10.1007/s00114-011-0775-2

28

Cappiello F. Loffredo M. R. Del Plato C. Cammarone S. Casciaro B. Quaglio D. et al . (2020). The revaluation of plant-derived terpenes to fight antibiotic-resistant infections. Antibiotics9, 325. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060325

29

Cardoso L. A. Karp S. G. Vendruscolo F. Kanno K. Y. Zoz L. I. Carvalho J. C. (2017). “ Biotechnological production of carotenoids and their applications in food and pharmaceutical products,” in Carotenoids, London, UK: InTechOpen vol. 125. , 125–141.

30

Carroll A. R. Copp B. R. Davis R. A. Keyzers R. A. Prinsep M. R. (2019). Marine natural products. Natural product Rep.36, 122–173. doi: 10.1039/C8NP00092A

31

Corinaldesi C. Barone G. Marcellini F. Dell’Anno A. Danovaro R. (2017). Marine microbial-derived molecules and their potential use in cosmeceutical and cosmetic products. Mar. Drugs15, 118. doi: 10.3390/md15040118

32

Corral P. Amoozegar M. A. Ventosa A. (2019). Halophiles and their biomolecules: recent advances and future applications in biomedicine. Mar. Drugs18, 33. doi: 10.3390/md18010033

33

Courtois A. Berthou C. Guézennec J. Boisset C. Bordron A. (2014). Exopolysaccharides isolated from hydrothermal vent bacteria can modulate the complement system. PloS One9, e94965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094965

34