Abstract

This article explores the tension between the integrity of marine ecosystems and the fragmented administrative systems prevalent in unitary states. Drawing upon the theoretical frameworks of holistic governance, this study investigates the institutional innovations introduced by the MEPL 2023. It conducts a comparative analysis of institutional practices from the European Union’s Maritime Strategy Framework Directive, the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, and the Arctic MOSPA Agreement. The central focus of the analysis lies in the responsibilities of each department at the central level, the local primacy at the level and a three-tiered responsibility framework encompassing “local primary responsibility, cross-regional coordination, and cross-departmental coordination”, and its role in addressing the fragmentation in marine governance. MEPL 2023 has effectively transformed local governments from passive implementers into proactive collaborators. However, due to ambiguities in the delineation of vertical and horizontal responsibilities and the heterogeneous institutional structures at the local level, significant gaps persist in enforcement. To enhance intergovernmental cooperation, this study proposes targeted strategies from both legislative and enforcement perspectives: clarifying the specific responsibilities of administrative entities at all levels, establishing uniform enforcement standards, creating regional marine management committees, codifying coordinative mechanisms within the draft Ecological Environment Code, and developing a digital platform to support joint monitoring, emergency response, and cross-jurisdictional enforcement. This research provides a replicable and scalable governance model for unitary states within the context of comparative environmental law, aimed at achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14.

1 Introduction

The core contradiction inherent in marine environmental governance arises from the fundamental conflict between the ocean’s natural characteristics—such as its fluidity and integrity—and the administrative management system, which is characterized by a dispersion of departmental functions and administrative divisions. Clarifying the boundaries of local governments’ rights and responsibilities in marine environmental protection, along with establishing a robust coordination governance mechanism, is essential for addressing the challenges faced in marine environmental governance and enhancing both the modernization of governance systems and overall governance capacity.

The Marine Environmental Protection Law (Marine Environmental Protection Law of the People's Republic of China, 2023), revised by China in 2023, represents not only a significant milestone in domestic marine governance but also offers a new institutional model for global marine environmental governance. MEPL 2023 not only reflects the governance rationale of imposing “the most stringent institutional safeguards” but also resonates profoundly with Goal 14 of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development- “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development” (UN. General Assembly, 2015). It provides other unitary states with a legislative framework and examples for clause design that can be utilized as references.

In our country, the fragmented, block-oriented, and decentralized management system governing marine environments has emerged based on industry-specific functional management (Wang & Song, 2017): responsibility for managing marine environments is distributed among eight State Council departments—including the Ministry of Ecology and Environment—as well as coast guard agencies and military entities. At local levels, this reflects an extension of land-based administrative division management models. Such a decentralized approach creates tension with oceanic unity, resulting in fragmentation within practical applications of marine management.

In response to this pressing need, the new law has achieved a significant breakthrough. On one hand, it establishes that “coastal local people’s governments at or above the county level shall be responsible for the quality of the marine environment in the sea areas under their administration”1 and implement the “target responsibility system and assessment and evaluation system”2 to reinforce local responsibilities. On the other hand, within the current fragmented framework, more explicit and detailed regulations regarding cross-departmental and cross-regional collaboration mechanisms have been introduced in multiple provisions to enhance inter-governmental coordination. This aims to reduce administrative barriers and regional divisions in marine environmental protection while fostering a coordination governance model characterized by clear rights and responsibilities, coordinated interactions, and efficient operations. This study will be grounded in theories of collaborative governance and holistic governance, analyzing relevant norms established by the new law with a focus on institutional innovations aimed at strengthening inter-governmental coordination governance. Building upon this foundation, it will explore effective pathways for optimizing government collaborative governance mechanisms concerning marine environments, thereby providing valuable insights into rights allocation and responsibilities within global marine governance frameworks.

2 Theoretical foundations and institutional frameworks governing the allocation of government responsibility

The theory of holistic governance points to the innovative direction of governance that breaks down administrative barriers, integrates governance resources, and achieves effective interaction among multiple subjects, which serves as the theoretical foundation for understanding the government responsibility allocation system for marine environmental protection as stipulated in the MEPL 2023.

2.1 The theory of holistic governance and its application in marine environmental governance

The theory of holistic governance emerged as a response to the fragmentation issues associated with the new public management movement. (Six, 1997; Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011) Its central tenet advocates for seamless public services and governance through institutionalized and regularized cross-departmental collaboration and integration, driven by citizens’ needs and aimed at addressing complex problems. This approach seeks to bridge policy gaps, mitigate service fragmentation, and clarify responsibilities that often become ambiguous due to professional specialization, departmental silos, and hierarchical segmentation.

The essence of holistic governance theory is rooted in integration and coordination. When applied to marine environmental governance, it primarily emphasizes three key aspects: (1) The importance of communication and collaboration among various levels of government. This includes understanding the roles, status, and functions of central and local governments, as well as the relationships between different governmental departments at both superior and subordinate levels within localities. (2) It highlights the necessity for effective communication and cooperation between government entities and social organizations. This encompasses inter-organizational coordination among multiple stakeholders, including government agencies, enterprises, civil society organizations, citizens, and examines their collective impact on marine environmental governance. (3) It addresses the management system and coordination mechanisms involved in this process. This includes institutional frameworks, cooperative arrangements, consultation processes, etc., along with an evaluation of their operational effectiveness.

In marine environmental governance, the government assumes a pivotal role. The primary actors include governmental bodies, enterprises, social organizations, and the public; however, the government remains central to these efforts. Key actions associated with marine environmental governance involve formulating governance plans as well as organizing management services during plan implementation while ensuring oversight throughout this process. In this process, the government fulfills multiple roles, such as leader, coordinator, commander and arbitrator. Consequently, this article aims to explore both the responsibilities assigned to governmental authorities in marine environmental governance as well as their corresponding coordination mechanisms.

2.2 Application of the MEPL government responsibility system to the theory of holistic governance

The MEPL adheres to the principle of “sea-land integration”, treating marine pollution and terrestrial pollution as interconnected issues while emphasizing the integrity of ecosystems. Under this principle, the MEPL has prioritized revising the government’s responsibility mechanism. This revision not only clearly delineates the responsibilities of each department horizontally but also establishes a three-tiered framework for inter-governmental coordination, based on a clear definition of local governments’ primary responsibilities vertically. This is a concrete manifestation of applying holistic governance theory to practical marine environmental management.

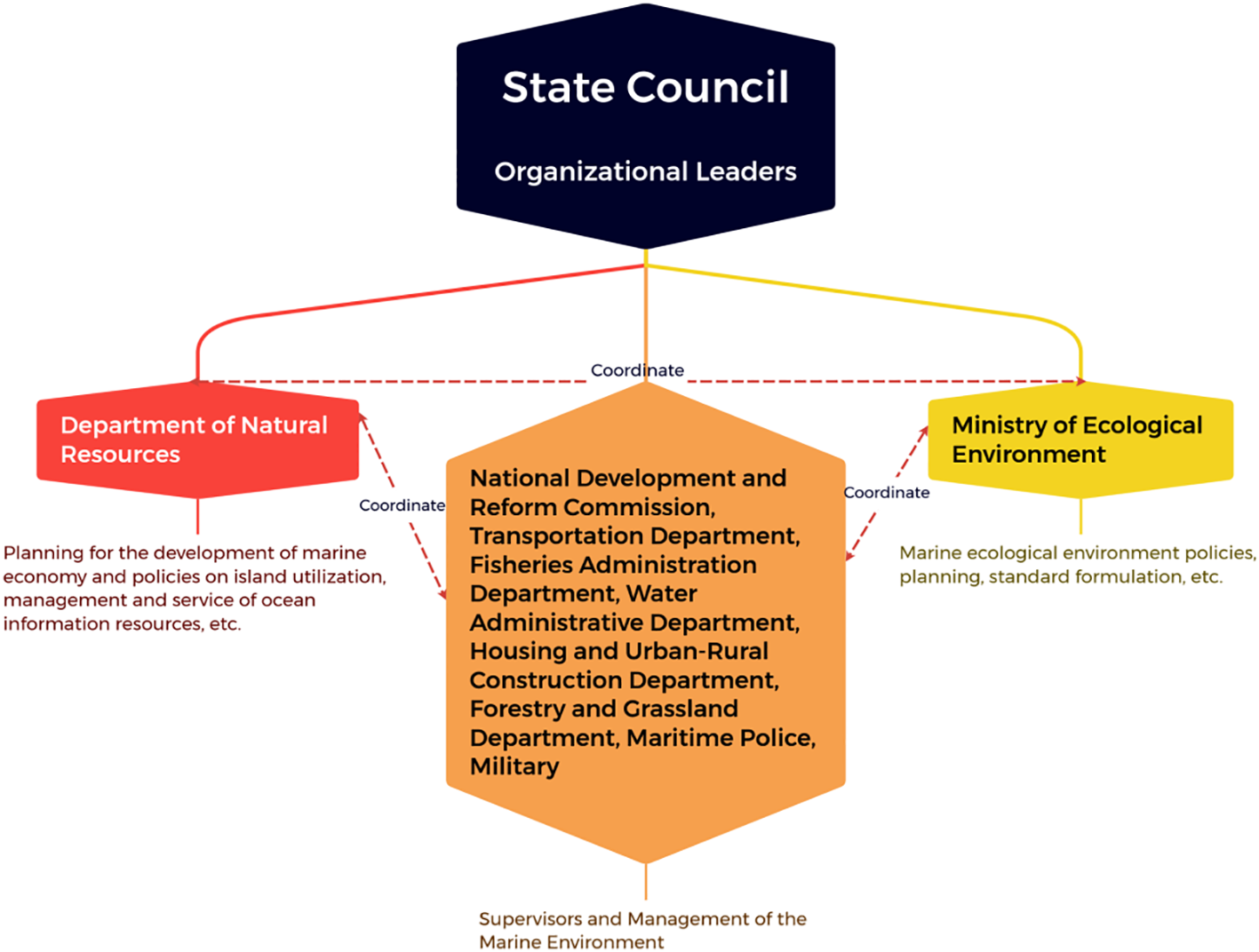

2.2.1 Clearly defines the responsibilities of each department at the central level

Article 4 of the MEPL addresses the outcomes of the 2018 national institutional reform by designating responsibility for marine environmental management to a department within the Ministry of Ecology and Environment.3 The Natural Resources Department is tasked with overseeing and managing marine development and utilization while retaining its external designation as the State Oceanic Administration.4 In terms of specific responsibilities, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment in China is charged with formulating policies, plans, and standards related to the marine ecological environment. Conversely, the Ministry of Natural Resources is responsible for planning marine economic development, establishing policies and technical standards for island utilization, as well as managing and providing services related to marine information resources. Additionally, various departments, including the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Transport, Fishery Administrative Department (under the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs), Ministry of Water Resources, China Coast Guard, collaborate to fulfill their respective roles in developing policies and regulations while coordinating efforts in supervising marine environmental protection. These institutions execute their designated duties while ensuring legal coordination among themselves in governing marine environments. (As illustrated in Figure 1).

Figure 1

The main responsibilities and coordination system for marine environmental governance at the central level.

2.2.2 Clearly stipulates the local primary responsibility at the local level

At the local level, the most significant change in the MEPL is the clarification of “local government responsibility”. The stipulation that “coastal local people’s governments at or above the county level shall be responsible for the quality of the marine environment in the sea areas under their administration”5 effectively balances both the physical characteristics of oceanic environments and governmental structures.

Given that oceans are dynamic systems where water bodies, pollutants, biological resources, etc., traverse administrative boundaries freely, no single administrative region can fully manage or control environmental quality in its maritime zones. The sustainable functioning of marine ecological environments relies on cooperative efforts in protection measures and pollution prevention across different administrative regions and departments.

From the perspective of the government organizational structure, China is a unitary state, and “line-block” coordination is an important proposition for the modernization of government governance. The “line-block” coordination in marine environmental governance should follow the principle of unified leadership by the central government, and the central and local governments should give full play to the enthusiasm and initiative of local governments in accordance with the principle of dividing powers and responsibilities. In terms of the “vertical management system” (“line”), based on the leading relationship between government authorities at higher and lower levels, the responsibilities for marine environmental protection from the central to local levels are administered through a vertical chain: the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (central level) → Departments of Ecology and Environment (provincial level) → Bureaus of Ecology and Environment (prefecture-level municipal and county levels). In terms of the “horizontal management system” (“block”), local governments with comprehensive administrative functions take overall charge of and bear responsibility for the marine environmental quality within their respective jurisdictions.

Local government responsibility entails that local administrative bodies must undertake active roles in construction, management, organization, coordination, and ensuring positive outcomes regarding environmental quality. Central to this framework is strengthening the role positioning of local governments as coordinators and accountable entities. To achieve these defined roles, legislation has established a “target responsibility system and assessment and evaluation system”6, which directly links environmental quality indicators—such as water quality compliance rates and effectiveness in ecological restoration—to governmental officials’ performance evaluations. This approach creates robust incentives for fulfilling their duties.

The principal responsibilities assigned to local authorities also inherently promote hierarchical integration and regional extension. Within China’s hierarchical structure comprising provincial, municipal, and county levels of governance, relationships between superiors and subordinates delineate a “responsibility chain” for target assessments. Consequently, it follows that local authorities’ main responsibilities necessitate vertical integration across various tiers of governance. Under the physical characteristics of the ocean’s integrity and fluidity, the local primary responsibility system inherently requires local governments to transcend the boundaries of their jurisdictions and achieve governance integration in a larger area by participating in or leading regional collaboration mechanisms, in order to fulfill the responsibility of ensuring or improving the marine environmental quality within their respective jurisdictions.

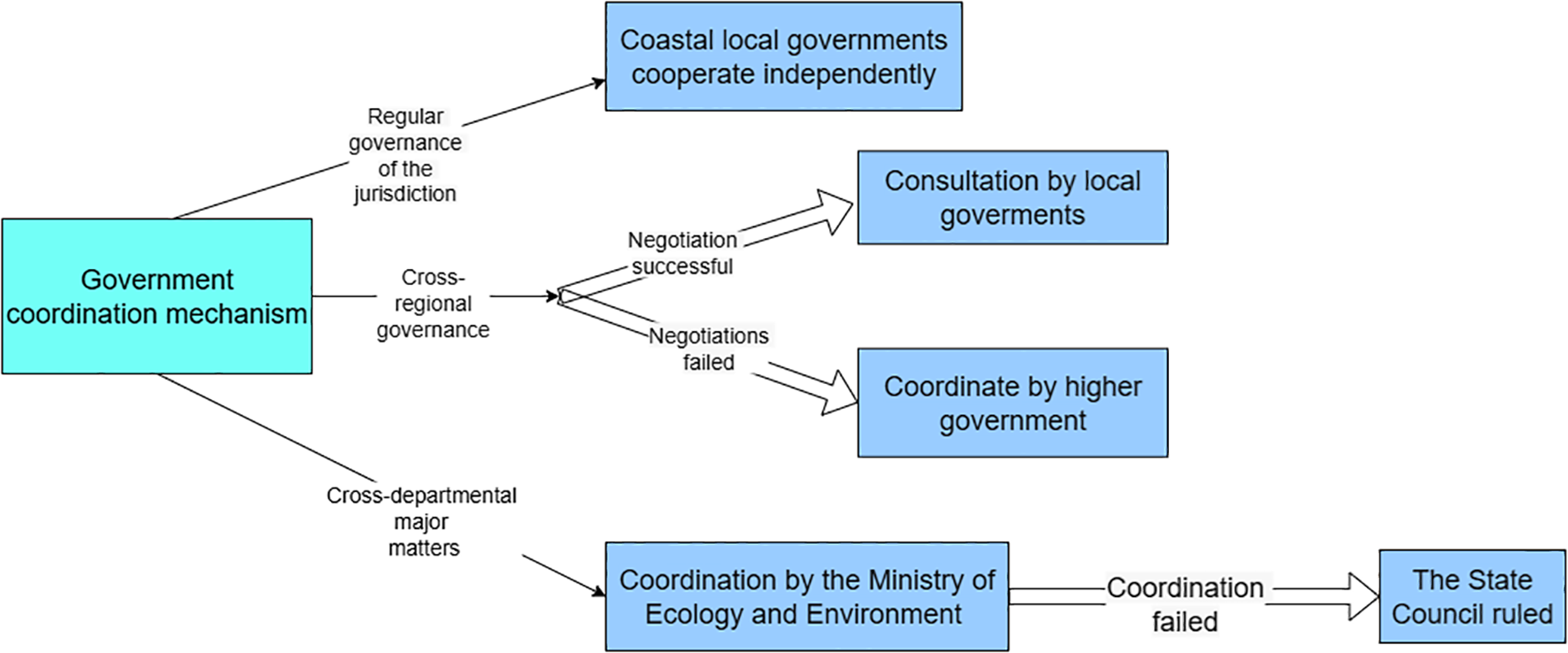

2.2.3 Establish a three-tiered responsibility framework at the coordination mechanism level

Article 6 of the MEPL 2023 is one of the most institutional breakthroughs in the aspect of government collaborative governance in the new law. Compared with Article 9 of the MEPL2017 which merely emphasized that “local people’s governments concerned shall resolve disputes through consultation”7, the new legislation adds Article 6(1) that explicitly grants “coastal local people’s governments at or above the county level may establish a regional cooperation mechanism for marine environmental protection”8, encouraging regular institutionalized cooperation and providing a system framework for proactive cooperation among governments. In accordance with the results of the State Council’s institutional reform in 2018, Article 6(3) of the MEPL 2023 changes “environmental protection department”9 to “ecological and environmental department”10.

This provision addresses regional collaboration alongside cross-regional and cross-departmental coordination. Articles 20, 25, 40, and 50 of MEPL 2023 delineate specific aspects such as governing key marine areas, collaborative monitoring efforts, regional linkages, and coordinated prevention and control measures concerning pollution from rivers discharging into the sea. This approach facilitates precise stratification of responsible entities and governance targets while promoting systematic and coordinated development within marine governance initiatives.

The revised Article 6 has established a hierarchical protection mechanism. For daily environmental protection affairs within the maritime area, Article 6(1) empowers local governments to independently establish collaborative mechanisms. In cases of cross-regional disputes, Article 6(2) mandates that coastal local governments resolve these issues through consultation or by seeking guidance from their superiors. For significant cross-departmental matters, coordination shall be undertaken by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment; if this coordination fails, the State Council will render a decision under Article 6(3). Consequently, the new legislation delineates a three-tiered responsibility framework comprising local autonomy, superior coordination, and central decision-making. Within the established institutional framework, encompassing the local governance responsibilities of governments at their respective levels and the regulatory oversight functions of higher-level government departments, this structure not only accommodates the flexibility inherent in local collaboration but also reinforces the central guarantee’s coordination framework. For further details, please refer to Figure 2:

Figure 2

Government coordination mechanisms for marine environment protection.

This institutional innovation has transformed local governments from passive responsibility bearers into proactive collaborative promoters. It has laid a robust foundation for institutional arrangements such as central-local coordination in key marine areas11, information sharing12, “river-sea linkage” initiatives aimed at ecological restoration of estuaries flowing into the sea13, and joint prevention and basin-sea area joint prevention and control measures for pollutants entering marine environments14.

From a holistic governance perspective, this three-tiered responsibility structure clarifies the roles and functions of governments at all levels in collaborative governance. The key actions for the holistic governance of the marine environment include formulating governance plans, organizing implementation, and supervising the implementation process. The three-tiered responsibility framework is highly aligned with the theory of holistic governance: On one hand, the framework is grounded in the principle of local governments assuming primary responsibility. As the governance scope expands, it establishes an inter-governmental responsibility collaboration mechanism that progresses from local primary responsibility to cross-regional coordination, and ultimately to cross-departmental collaboration at the central government level. This achieves organizational integration and clarifies the division of powers and responsibilities from both the “lines” and “blocks” dimensions. On the other hand, it emphasizes the synergy between the functions of governments at different levels. Examples include the independent daily management by local governments, the cross-regional coordination by higher-level governments, the organization of major cross-departmental initiatives by State Council ministries, and the final decision-making authority of the State Council. The core objective of this three-tiered is to prevent local governments from succumbing to a “prisoner’s dilemma” arising from divergent interests within their jurisdictions. Through a step-by-step responsibility arrangement, the willingness to negotiate among local governments is transformed into institutionalized rigidity, and the daily collaboration among local governments, coordination at higher levels and the central government’s bottom-line guarantee are organically combined, providing a systematic institutional arrangement for cross-regional Marine environmental governance. This not only helps alleviate the fragmented predicament of “nine dragons governing water”, but also provides a system framework for our country to further improve cross-regional and cross-departmental collaboration in the future.

3 Analysis for the implementation about the government responsibility in the marine environmental protection law

Since the MEPL revised the government responsibility system based on the holistic governance theoretical framework, notable results have been achieved. As of the end of May 2025, a total of over 63,000 marine discharge outlets have been inspected across the country, with the completion rate of remediation for such outlets in key bays reaching 93.1%.15 In terms of law enforcement, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the China Coast Guard, and other relevant authorities have established a supervision and law enforcement mechanism. On the basis of regular patrols and law enforcement, they have jointly carried out special supervision and law enforcement campaigns such as “Green Shield” and “Blue Sea”.16.

However, in practice, affected by the inherent structural contradictions in China’s “line-block integration” administrative system, a certain degree of misalignment between powers and responsibilities has emerged. This misalignment occurs between local governments that bear responsibility for marine environmental quality (“block”) and vertically managed departments that control law enforcement resources (“line”). Specifically, this misalignment manifests in two major practical challenges: firstly, the coordination difficulty in the connection of governance responsibilities between the central government and local governments at the vertical level; secondly, the collaboration dilemma among governments at the same level in cross-regional and cross-domain governance at the horizontal level.

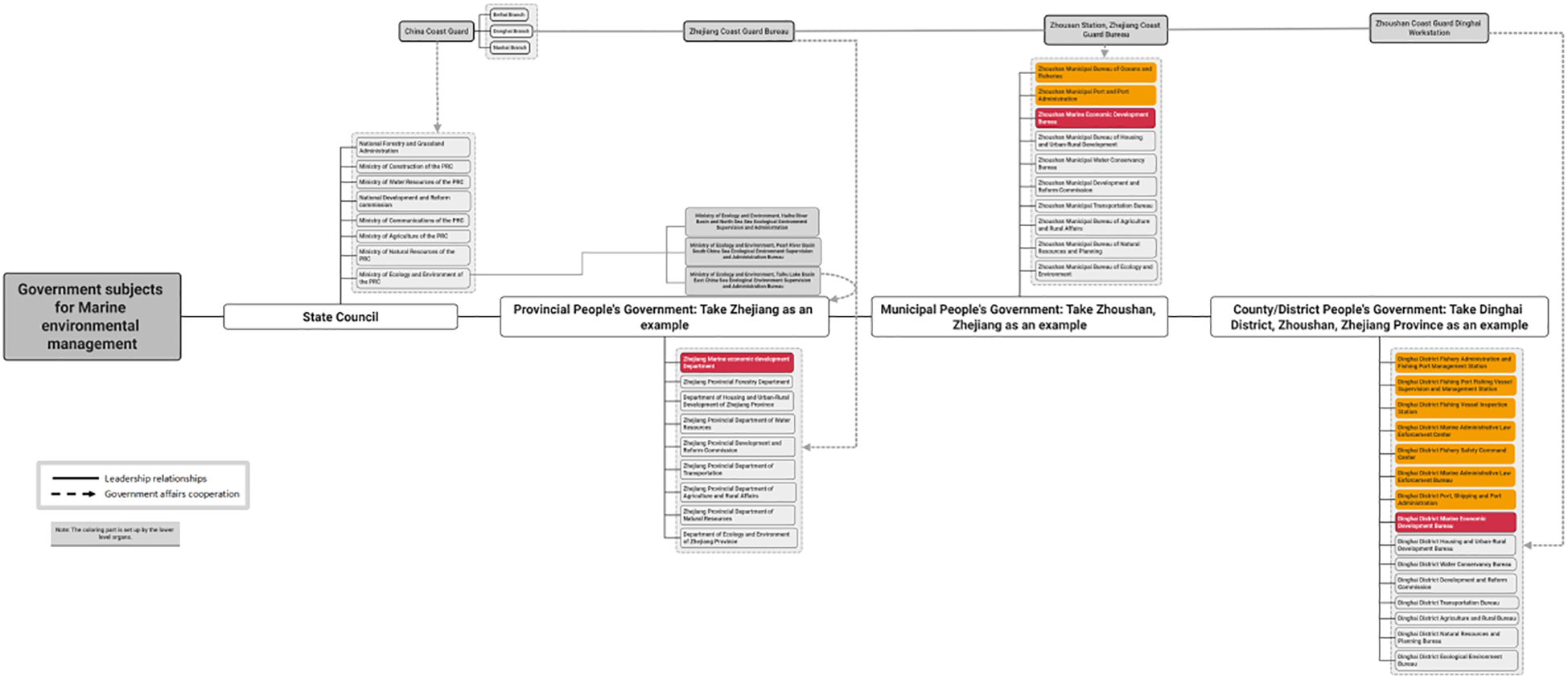

Under the “dual-track” governance model combining vertical and horizontal administration in China, there exist two types of local law enforcement entities: those under the vertical management of central authorities and those under the horizontal administration of local governments. (Vincent, 2015) The MEPL 2023 establishes a vertical and horizontal accountability system, which, in practice, generates vertical, horizontal, and intersecting institutional relationships. (Cui and Mao, 2025) Vertically, it refers to the relationships between different levels of government and their respective departments; horizontally, it denotes the relationships among governments or departments at the same administrative level. (See Figure 3) A more particular case arises in the relationship between central government’s dispatched agencies for marine affairs and local marine administrative departments: while these institutions differ in administrative hierarchy and lack direct subordination, their functions concerning marine governance are intertwined. Such “dual-track” system gives rise to significant challenges in administrative coordination and law enforcement.

Figure 3

Government responsible entity system for marine environment law enforcement in China.

3.1 Coordination challenges between central and local authorities

Local entities such as the China Coast Guard and the dispatched agencies of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and the Ministry of Natural Resources operate independently of local governments in terms of personnel authority, fiscal control, and administrative responsibilities, and function under the leadership of central authorities. In contrast, law enforcement entities under local government control include departments structurally mirroring those at higher administrative levels, as well as those established in light of local specificities. In mainland China, there are 11 coastal provinces (municipalities/autonomous regions): Liaoning, Hebei, Tianjin, Shandong, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan. These are further subdivided into 51 prefecture-level cities and 208 county-level governments.

Taking the provincial government as an example, in general, in addition to corresponding to the central government agencies at the provincial level, various localities will set up separate agencies based on regional or industrial differences, which is relatively independent and cannot be directly connected with the central agencies. For example, Zhejiang and Hainan—both prominent maritime provinces—have established specialized bodies such as the Zhejiang Marine economic development Department and the Hainan Provincial Department of Oceans, which directly subordinate to the provincial governments. China’s marine administrative structure may be conceptually visualized as a “linear–radial” stratified framework: from the central government to the coastal provinces (autonomous regions and centrally administered municipalities), operations follow a linear model; in contrast, at the municipal and county levels, there is pronounced structural differentiation, manifesting in a radial configuration. At the central level, it is divided by departments and forms a vertical (“line”) relationship with the corresponding departments of lower-level governments. At the local level, provincial, municipal, and county governments bear legal responsibility for the jurisdictions under their control (the “block” structure). Due to mismatches in the correspondence and subordination between “lines” and “blocks”, and the absence of legal provisions clearly defining coordination mechanisms, the cooperation between central and local authorities in practice is significantly hindered.

3.2 Coordination challenges among local governments at the same level

The coordination problem is equally pronounced at the same administrative level due to the fragmented institutional design of marine-related agencies established by various coastal municipal and county (or district) governments that based on their local industrial or sectoral needs. This “line-block” misalignment is particularly salient at the provincial, municipal, and county levels. Among the coastal provinces, municipalities, and counties, Zhejiang Province stands out with a distinct comparative advantage in the marine sector. The province serves as an illustrative case for analyzing these issues, particularly through the lens of fishery pollution regulatory enforcement across the provincial–municipal–county hierarchy.

In practice, marine environmental enforcement mechanisms across the “province–municipal–county” levels can be broadly categorized into two models: unified administration and fragmented enforcement (Sun and Hu, 2025). At the provincial level, take Jiangsu Province as an example, fishery pollution regulation at all three levels falls under the Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, forming a structurally uniform and vertically aligned model. In contrast, Zhejiang Province exemplifies a fragmented enforcement model. At the provincial level, supervision of marine fishery pollution falls under the Ministry of Natural Resources.17 Despite being neighboring provinces, the disparity between Jiangsu and Zhejiang in the assignment of fishery pollution enforcement bodies complicates cross-regional coordination, thereby diminishing enforcement efficiency.

At the municipal level, there also exists a misalignment of enforcement authorities. In Zhejiang Province, the administration of marine and fishery affairs is handled by different entities at the municipal and county levels. Specifically, at the municipal level, Zhoushan City places marine and fishery governance under the Bureau of Ocean and Fisheries, whereas Taizhou City assigns the same responsibilities to the Port, Navigation, and Fishery Administration Bureau. The former is a specialized agency focused on marine and fishery affairs, while the latter falls within the transportation and port management system. This structural incongruity between enforcement entities at the same administrative level is particularly evident.

At the county level, further divergences arise. In Jiaojiang District of Taizhou, fishery enforcement is overseen by the Bureau of Agriculture, Rural Affairs, and Water Resources, with operational responsibilities assumed by its subordinate Marine and Fishery Law Enforcement Team. In contrast, Sanmen County, also under the jurisdiction of Taizhou, assigns unified responsibility to its Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, with the Marine and Fishery Bureau and its Enforcement Team carrying out specific duties. The pronounced differentiation among Zhejiang’s provincial, municipal, and county-level enforcement bodies, coupled with their misaligned chains of command, presents serious obstacles to unified coordination and enforcement.

4 Refining government responsibilities and enhancing inter-governmental coordination

Effective marine environmental protection hinges on the clear delineation of government responsibilities and efficient coordination among governments at all levels. While China has established a basic framework for the marine environmental protection responsibility system, there remain areas requiring refinement, including the specification of responsibilities, law enforcement standards, and coordination mechanisms. From both legislative and law enforcement perspectives, this work systematically explores approaches to optimizing government responsibilities and strengthening inter-governmental coordination, thereby providing concrete pathways and solutions to enhance the effectiveness of marine environmental governance.

4.1 Legislative dimension

4.1.1 Clarify the specific contents of government responsibilities

Articles 4, 5, and 6 of the MEPL 2023 delineate a responsibility network for marine environmental protection, which is a kind of consequence-oriented result and establishes mechanisms for safeguarding the marine environment. However, several critical issues remain unresolved: how to achieve desired marine environmental quality; what local responsibilities entail; methods for assessing these responsibilities; the implications of failing to meet these responsibilities; and how to address such consequences. On July 18, 2025, the General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council issued the Provisions on the Responsibility System for Ecological and Environmental Protection by Local Party and Government Leading Officials (for Trial Implementation), clarifying the responsibilities of the primary leaders of local party committees and governments at or above the county level and providing a framework for addressing accountability (The General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council, 2025). To facilitate the implementation process, it is essential to further define more specific and operational guidelines, such as the delineation of powers and responsibilities between the central and local governments (Shohet Radom and Menahem, 2025), concrete performance evaluation indicators across the “central-provincial-municipal-county” administrative levels, and mechanisms for assuming responsibilities. The central government leads systematic governance across marine areas and river basins, while local authorities concentrate on refined management within their administrative jurisdictions to prevent the fragmentation of the marine ecosystem by administrative boundaries. At the central level, with a primary focus on “cross-regional, systematic, and emergency” protection of the marine ecological environment, it assumes responsibilities for policy formulation, overall coordination, supervision, and accountability. At the local level, provincial, municipal, and county-level governments carry out autonomous functions at varying levels based on core tasks related to “protection of the marine ecological environment within administrative jurisdictions”, emphasizing territoriality and refinement. Provincial governments are tasked with developing implementation plans for marine ecological environment protection in alignment with national directives. Meanwhile, municipal and county-level governments are responsible for executing local pollution control measures and grassroots emergency response initiatives.

4.1.2 Accelerate standard formulation for enforcement

Articles 16 to 20 of the MEPL 2023 constitute a normative cluster concerning labor division between central and local authorities. In light of this framework, it is imperative that the Ministry of Ecology and Environment accelerates its efforts in developing corresponding departmental regulations or benchmark plans to avoid the waste of law enforcement resources and policy inconsistencies arising from the implementation of disparate measures (Six and Diana, 1999). In March 2024, this ministry issued the Implementation Opinions on Accelerating the Establishment of a Modern Ecological Environment Monitoring System, proposing tasks such as “improving the integrated sky-ground-sea monitoring network, fostering revised advantages in digital and intelligent monitoring technologies, and promoting efficient monitoring management.” (Ministry of Ecology and Environment, 2024) In March 2025, in order to implement these tasks, it further issued the Plan for the Digital and Intelligent Transformation of the National Ecological Environment Monitoring Network to lead and drive high-quality development in ecological environment monitoring (Ministry of Ecology and Environment, 2025). Additionally, the introduction of the following standards and plans should also be prioritized, such as national marine environmental quality standards or environmental quality standards for various sub-regions of the sea, water pollution discharge standards, particularly typical carbon and nitrogen emission standards, and comprehensive action plans for marine environmental protection. Local governments should refine the central government’s plans and programs based on local conditions.

4.1.3 Establish a tiered coordination framework

Firstly, it is essential to adopt the regional sea cooperation model outlined in the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD, 2008/56/EC) to establish three “Regional Sea Management Committees” (European Union, 2008) for the Bohai Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea. These committees should be granted statutory functions to formulate regional standards and mediate inter-provincial disputes. From the perspective of the inherent attributes of marine ecosystems, the fluidity, integrity, and interrelationship of oceanic environments indicate that fragmented governance within a single administrative region is inadequate for addressing cross-regional marine environmental issues. These challenges include the transboundary transmission of land-based pollution, the protection of migratory marine biological resources, and responses to cross-sea ecological disasters. Drawing from practical experiences with the MSFD, it is evident that regional governance institutions must possess authority to coordinate efforts and establish standards that extend beyond individual member states (or provinces in our context). This insight is equally relevant to regional marine governance in China. Although our MEPL provides principle-based guidelines for cross-regional marine environmental protection, there remains a notable absence of specialized institutions tasked with specific coordination and implementation functions. Consequently, discrepancies have emerged among provinces regarding the formulation of marine environmental standards and delineation of pollution control responsibilities; instances of responsibility evasion have also been observed. Therefore, through legislative amendments or by introducing specialized regulations, it is essential to clearly define the legal authority granted to regional marine management committees. This includes their roles in formulating regional marine environmental standards, mediating disputes across provincial boundaries, and promoting coordinated ecological protection efforts. Establishing such institutional foundations will ensure their effective coordination capabilities are realized. Secondly, we propose the establishment of “Marine Affairs Coordination Committees” in coastal provinces, led by provincial government leaders responsible for integrating the functions of marine-related agencies. This initiative aims to create a unified interface with central marine departments, address existing gaps between local specialized agencies and central authorities, and standardize the functional positioning of marine-related agencies at various administrative levels—provincial, municipal, and county—within each province. In regions characterized by decentralized law enforcement (such as Zhejiang Province), it is advisable to conduct a “functional categorization” of relevant agencies such as the Department of Natural Resources and the Marine and Fisheries Bureau. This process would clarify both “guidance rights” and “filing rights” that provincial agencies hold over differentiated municipal contexts. Besides, we absolutely should draw on the experience of the U.S. Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement and encourage adjacent municipal governments to sign cooperation agreements with soft law binding force to facilitate joint monitoring, data sharing, and emergency response mechanisms.

4.1.4 Codify inter-governmental coordination via draft of ecological environmental code

To tackle issues related to fragmented environmental protection legislation, the National People’s Congress of China is compiling the Draft of Ecological Environmental Code to integrate nine individual laws, including the Marine Environment Protection Law and the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law. During the compilation of the code, reference can be made to Article 10 of the MSFD, which mandates member states to establish common indicators system. (European Union, 2008) All local governments should bear the primary responsibility for reducing pollution sources. Additionally, among local governments within the same sea area, reference can be made to the cross-border environmental impact assessment and responsibility-sharing mechanisms established in international conventions such as the Helsinki Convention and the Barcelona Convention, explicitly stipulating that local governments of pollution sources must continuously exchange monitoring data and risk control measures with affected local governments and, if necessary, establish a “mandatory joint environmental impact assessment for transboundary marine projects” based on project conditions.

4.2 Law enforcement dimension

4.2.1 Create a joint data monitoring and management system

The implementation of Article 11 of MSFD, which requires member states to develop coordinated monitoring programmes (European Union, 2008), can serve as a valuable reference for China. Local governments in China should establish a joint data monitoring and management system.

In cross-regional marine environmental protection efforts, regions can jointly establish a carbon footprint database based on pollutant discharge baselines. Enterprises and relevant departments in different regions should summarize and input pollutant discharge data from various marine-related production activities, such as offshore oil and gas exploitation and coastal industrial production. Simultaneously, a joint monitoring data analysis platform should be established to integrate multi-source data such as meteorological, hydrological, and geological data for comprehensive analysis and prediction of marine environmental change trends. This platform will utilize big data and artificial intelligence technologies to deeply mine vast amounts of monitoring data and promptly identify potential environmental risks. Local governments should rely on this platform to share information, avoid responsibility evasion in cross-regional marine environmental protection, and enhance the synergy and precision of governance.

4.2.2 Establish shipping-pollution emergency response linkage mechanism

Drawing inspiration from the Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic (MOSPA), local governments should create an emergency response linkage mechanism to address shipping pollution by developing an interconnected alert system for maritime accidents. When accidents such as fuel oil leaks or hazardous chemical leaks occur on ships, the system can promptly transmit alert information to relevant entities such as surrounding ships, port management authorities, maritime law enforcement agencies, and marine environmental monitoring departments. Based on the information provided by the interconnected system, departments and units will quickly activate emergency plans and take measures such as deploying oil booms and cleaning up pollutants to minimize the damage caused by shipping accidents to the marine environment.

4.2.3 Enable digital cross-regional joint law enforcement

It is essential to utilize digital supervision platforms to consolidate law enforcement resources across various departments, including maritime affairs, coastal defense, and ecological environment protection, thereby facilitating information sharing and collaborative command. The scope and frequency of marine pollution monitoring should be expanded through digital law enforcement methods such as unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) patrols. These UAVs can be equipped with high-definition cameras and pollution detection instruments to conduct real-time surveillance of critical sea areas while transmitting acquired images and data back to the command center instantaneously. Based on this monitoring data, law enforcement personnel can accurately identify sources of pollution and pinpoint locations of violations, enabling them to respond swiftly at enforcement sites while enhancing both efficiency and precision in their operations. Furthermore, by leveraging digital platforms alongside big data systems, it is possible to dismantle temporal and spatial barriers among law enforcement agencies, thus achieving remote joint law enforcement capabilities. In cases involving cross-regional marine pollution incidents, different regional law enforcement departments can engage in video conferences via these platforms to collaborate effectively on case management; share evidentiary materials; ensure fairness and consistency in legal actions; and foster robust synergies that enhance efforts against diverse forms of marine pollution violations.

5 Conclusion

The revisions to the MEPL 2023 signify a substantial transformation in China’s marine governance paradigm. By designating local governments as the primary entities responsible for marine environmental quality within their jurisdictions and institutionalizing mechanisms for cross-regional and cross-departmental collaboration (e.g., Article 6), this law shifts local authorities from being passive implementers to proactive collaborators. This institutional framework not only addresses the “tragedy of the commons” in marine management but also aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14, providing a replicable model for unitary states aiming to enhance their marine governance.

Nevertheless, notable implementation gaps persist. Vertically, ambiguities surrounding the delineation of responsibilities between central and local authorities, coupled with mismatched “line-block” administrative structures, impede effective coordination among central agencies (such as the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and China Coast Guard) and local governments. Horizontally, diverse institutional configurations at provincial, municipal, and county levels—illustrated by differing fishery pollution enforcement mechanisms in Zhejiang—hinder unified enforcement efforts and cross-regional cooperation. These challenges highlight an urgent need for targeted legislative and operational reforms: clarifying role-specific responsibilities across various administrative tiers; standardizing enforcement criteria; establishing regional marine management committees; codifying collaborative efforts within the draft Ecological Environment Code; and developing digital platforms for joint monitoring and law enforcement.

Looking ahead, several critical research directions emerge to strengthen the MEPL implementation and enhance China’s marine governance capacity: (1) Comparative institutional analysis should be undertaken to evaluate different models for central-local coordination in marine environmental management, which could provide valuable insights for optimizing China’s own governance strategies. (2) Interdisciplinary research is needed to develop metrics for evaluating the ecological and economic effectiveness of key regulatory tools under the MEPL, particularly ecological red lines and total pollutant discharge control systems. (3) Research should assess the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of deploying advanced monitoring technologies and explore how digital platforms can facilitate cross-departmental and cross-regional information sharing. (4) Legal scholarship should focus on the interface between the MEPL and other relevant legal frameworks, particularly in the context of China’s ongoing environmental code compilation. (5) Empirical studies on the implementation of marine environmental cases would enhance understanding of how judicial mechanisms complement administrative enforcement. Research should examine factors influencing case selection, enforcement outcomes, and the long-term impact of litigation on compliance behavior, potentially identifying opportunities to strengthen the role of courts in promoting environmental justice.

In conclusion, the MEPL 2023 initiative signifies a pivotal advancement toward integrated marine governance; however, its success is contingent upon the effective translation of institutional innovations into practical applications. By addressing barriers to implementation and enhancing collaborative mechanisms, China’s experiences can provide valuable insights for global efforts aimed at reconciling administrative fragmentation with the ecological coherence of oceanic systems. Ultimately, this approach will contribute to the promotion of sustainable marine development on a worldwide scale.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

XL: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. YN: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by China’s National Social Sciences Fund (No. 22BFX024), Research Project of Humanities and Social Sciences of China’s Ministry of Education (No. 21YJA820014), and Major Research Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences by China’s Ministry of Education (No. 21JZD033).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^Article 5(1) of the MEPL 2023.

2.^Article 5(2) of the MEPL 2023.

3.^Article 4(1) of the MEPL 2023.

4.^Article 4(2) of the MEPL 2023.

5.^Article 5(1) of the MEPL 2023.

6.^Article 5(2) of the MEPL 2023.

7.^Article 9 of the MEPL 2017.

8.^Article 6(1) of the MEPL 2023.

9.^Article 6 of the MEPL 2017.

10.^Article 6(3) of the MEPL 2023.

11.^Article 20 of the MEPL 2023.

12.^Article 25 of the MEPL 2023.

13.^Article 40 of the MEPL 2023.

14.^Article 50 of the MEPL 2023.

15.^CHINANEWS, The Ministry of Ecology and Environment: More than 63,000 Marine discharge outlets have been investigated across the country (in Chinese). Available on: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/gn/2025/06-25/10437765.shtml.

16.^CHINANEWS, The Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Protect the ocean with the strictest systems and the most rigorous rule of law (in Chinese). Available on: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/gn/2024/07-11/10249436.shtml.

17.^According to the Zhejiang Institutional Reform Plan, the responsibilities of the former Ocean and Fishery Bureau were consolidated into the Department of Natural Resources in 2019 (in Chinese). Available on: https://zrzyt.zj.gov.cn/col/col1293266/index.html.

References

1

Cui W. Mao X. (2025). An analysis of the multiple structure and functional linkage mechanism of ocean management in contemporary chinese governance. Acad. Monthly5, 86. doi: 10.19862/j.cnki.xsyk.001075

2

European Union (2008). Marine Strategy Framework Directive 2008/56/EC. Strasbourg: European Parliament and the Council of the European Union.

3

Marine Environmental Protection Law of the People's Republic of China . (2023). Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. 2023-10-24.

4

Ministry of Ecology and Environment (2024). Notice on the Issuance of the Implementation Opinions on Accelerating the Establishment of a Modern Ecological and Environmental Monitoring System (Huan Jian Ce [2024] No. 17). Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202403/content_6939814.htm (Accessed July 20, 2025).

5

Ministry of Ecology and Environment (2025). An Illustrated Guide to the Digital Transformation Plan for the National Ecological and Environmental Monitoring Network. Available online at: https://www.mee.gov.cn/zcwj/zcjd/202503/t20250330_1105010.shtml (Accessed July 20, 2025).

6

Pollitt C. Bouckaert G. (2011). Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis-New Public Management, Governance, and the Neo- Weberian Slate. 3rd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

7

Shohet Radom O. Menahem G. (2025). Local autonomy and municipal activism: A new framework for examining relations between central and local government. Land14, 587. doi: 10.3390/land14030587

8

Six P. (1997). Holistic Government (London: Demos).

9

Six P. Diana L. (1999). Governing in the Round: Strategies for Holistie Government (London: Demos).

10

Sun R. Hu D. (2025). China’s marine eco-environment law enforcement from the perspective of the responsibility system: Dilemmas and solutions. Mar. Policy171, 106437. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106437

11

The General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council (2025). Provisions on the Accountability System for Local Party and Government Leading Cadres in Ecological and Environmental Protection (for Trial Implementation). Available online at: https://www.mee.gov.cn/zcwj/zyygwj/202507/t20250730_1124558.shtml (Accessed July 22, 2025> ).

12

UN. General Assembly (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: resolution/adopted by the General Assembly. Available online at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3923923?v=pdf (Accessed July 22, 2025).

13

Vincent C. (2015). Central-local government relations: implications on the autonomy and discretion of ZimbabweÂ’s local government. J. Political Sci. Public Affairs3, 1–2. doi: 10.4172/2332-0761.1000143

14

Wang G. Song K. Y. (2017). China’s marine environmental management system: change, dilemma and reform. J. China Ocean Univ2, 22–23. doi: 10.16497/j.cnki.1672-335x.2017.02.006

Summary

Keywords

marine environment protection law (MEPL), government responsibilities, government coordination mechanisms, marine governance, China

Citation

Li X and Ning Y (2025) Government coordination mechanism in marine governance: a study on China’s 2023 marine environmental protection law. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1699439. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1699439

Received

05 September 2025

Accepted

20 October 2025

Published

30 October 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Xiaoshou Liu, Ocean University of China, China

Reviewed by

Yen-Chiang Chang, Dalian Maritime University, China; Qi Xu, Jinan University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li and Ning.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu Ning, ningyusysu@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.