Abstract

The hybrid abalone (Haliotis discus hannai ♀ × H. fulgens ♂), locally known as Lvpan abalone, is a commercially important aquaculture species in Fujian Province, China and is valued for its heat tolerance, rapid growth, and large size. While blooms of the dinoflagellate Karenia mikimotoi cause substantial losses in Fujian’s abalone industry primarily through toxin production and hypoxia, their specific effects on Lvpan abalone remain poorly characterized. This study investigated the 24-h and 48-h exposure effects of a simulated K. mikimotoi bloom on the gills and hepatopancreas of Lvpan abalone. Histopathology revealed significant tissue damage, along with oxidative stress that was confirmed by elevated levels of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and malondialdehyde. Metabolomic profiling uncovered a tissue-specific response. Both tissues exhibited shared responses to mitigate oxidative stress and regulate energy balance, mediated by the accumulation of β-hydroxybutyric acid and acetyl-L-carnitine. In addition, the gills maintained energy homeostasis through AMPK activation, whereas the hepatopancreas enhanced its detoxification capacity through elevated levels of S-adenosylmethionine. These findings elucidate the impact of K. mikimotoi blooms on Lvpan abalone and provide a scientific basis for developing mitigation strategies against toxic algal blooms in abalone aquaculture.

1 Introduction

Abalone is a mariculture molluscan species with high economic value (Cook, 2023). China accounts for 90% of global farmed abalone production (Zhou et al., 2024), while Fujian Province produces over 75% of national production (Gao et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). However, problems such as water quality deterioration (Liang et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023b), summer heat (Xu et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2023a) and germplasm degradation (Zhou et al., 2024) have negative effects on the major aquaculture species of abalone in China, namely Pacific abalone (Haliotis discus hannai). To address these challenges, a hybrid abalone (H. discus hannai ♀ × H. fulgens ♂), locally termed Lvpan abalone, has been extensively cultivated in southern China due to its enhanced thermal resilience, accelerated growth rates, and superior size potential compared to parental species (Gao et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2024). However, even promising new hybrids like Lvpan abalone are increasingly threatened by harmful algal blooms (HABs) in their primary cultivation areas, such as the coastal waters of Fujian.

HABs are increasing globally in eutrophic mariculture zones, inducing hypoxia and toxin exposure that threaten aquaculture sustainability (Brand et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2023b). Karenia mikimotoi is a well-known toxic dinoflagellate, which has induced blooms in the East China Sea almost every year since 2002, with the maximum cell density recorded exceeding 1×107 cells/L (Chen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2019). In 2012, a large-scale HAB caused by K. mikimotoi along the coast of Fujian caused mass mortality of Pacific abalone, with an economic loss of 330 million USD. This represents the highest economic loss ever recorded in China caused by HABs (Liao et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2023b).

K. mikimotoi exhibits multiple toxic effects on marine organisms through reactive oxygen species (ROS), hemolytic toxins and cytotoxicity (Li et al., 2019). For example, the antioxidant enzymes in gills and hepatopancreas of Pacific abalone were significantly negatively affected by K. mikimotoi under aeration (Lin et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018). Moreover, dissolved oxygen (DO) levels during K. mikimotoi blooms can decrease to 2.0 mg/L (Liao et al., 2024; O’Boyle et al., 2016), leading to growth inhibition and mortality in both Pacific abalone and Lvpan abalone by disrupting their immunity and oxidative balance (Dai et al., 2024; Nam et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2020). Consequently, K. mikimotoi blooms threaten abalone via a combination of direct toxicity and hypoxia-induced stress. Despite established knowledge that this combined exposure is particularly severe for Pacific abalone (Liao et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023b), its consequences for Lvpan abalone remain unknown.

Therefore, this study aimed to simulate the combined stressors of a K. mikimotoi bloom (toxin exposure and hypoxia) and systematically examine the stress responses in Lvpan abalone. We focused on histopathological alterations in the gills and hepatopancreas, the response of the antioxidant defense system, and adaptations in the metabolic profile, thereby elucidating the toxicity mechanisms and providing a scientific basis for the healthy aquaculture of Lvpan abalone and HABs prevention.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Algae and abalone culture

K. mikimotoi FJ-strain, originally isolated from the Fujian coastal waters, was obtained from the Key Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environmental Science, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. For cultivation, seawater was first filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane and then autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min. After cooling, the sterile seawater was enriched with L1 medium prepared without silicate (Guillard and Hargraves, 1993). The cultures were maintained in an air-conditioned room at 20 ± 1 °C and illuminated with a 12: 12 h light-dark cycle at a light intensity of 60 μmol photons m−2 s−1.

Lvpan abalones were purchased from a breeding facility in Dongshan, Fujian, China. Medium-sized individuals (shell length: 5.71 ± 0.50 cm; shell width: 3.90 ± 0.38 cm) were selected and acclimated for 14 days in an aerated seawater recirculating system. The temperature of seawater was maintained at 20 ± 1 °C, and the abalones were fed fresh kelp.

2.2 Experimental design and sample collection

Based on reported cell densities and DO levels during K. mikimotoi blooms in Chinese coastal waters (Liao et al., 2024; Li et al., 2019; O’Boyle et al., 2016), laboratory-simulated bloom conditions were set at 1× 107 cells/L and 2.0 mg/L DO, respectively. The control group and treatment group (S-group) were setup in triplicate using six 20 L plastic rectangular boxes. Each box contained 15 healthy abalone individuals. For the S-group, 15 L of algal culture (1× 107 cells/L) was added to each box. The DO concentration in the S-group was monitored in real-time using a DO probe, with a DO controller (Jenco 6308DT, accuracy ± 0.05 mg/L) automatically adjusting air and pure nitrogen inputs to stabilize the DO level at 2.0 mg/L. In the control group, 15 abalone individuals were cultured in 15 L of seawater with continuous aeration. To minimize the effect of abalone metabolites on water quality, the water in each box was completely replaced with 15 L of freshly prepared algal culture (for S-group) or filtered seawater (for C-group) daily. The culture conditions during the experiment were maintained at 20 ± 1 °C under a 12: 12 h light-dark cycle. Abalone that lost gastropod adhesion and showed no response to repeated stimulation were considered dead and were removed immediately to avoid water contamination.

Two exposure periods (24 and 48 hours) were selected for the formal experiment to simulate the actual co-occurrence of high-density K. mikimotoi (1×107 cells/L) and hypoxic conditions (2.0 mg/L) during blooms in coastal aquaculture areas, a design that aligns with prior studies on these combined stressors in abalone (Liao et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023b). After 24 hours, three live abalone individuals were randomly sampled from each box (nine abalone individuals per group), for both the control group (C) and the S-group (S24). An additional sampling (nine abalone individuals) was performed for the S-group at 48 h (S48). Gills and hepatopancreas were dissected from nine abalone per group. Tissues from each organ and individual were divided into four portions for parallel histological examination, biochemical parameter quantification, and metabolomic profiling, the fourth aliquot was reserved as a backup. For histological analysis, samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, while all remaining samples were stored in liquid nitrogen.

2.3 Histological observation

After 48h fixation, specimens for histological examination were dehydrated through a graded alcohol series (75% for 4h, 85% for 2h, 90% for 2h, 95% for 1h, and two changes of anhydrous ethanol for 30 min each). Afterwards, they were cleared twice using xylene for 10 min each and finally embedded in molten paraffin. The paraffin blocks were sectioned into four µm-thick slices with a microtome (Leica® RM2016, Germany) and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Dutra et al., 2017). sections were observed and imaged using a light microscopy system (Nikon® Eclipse E100 equipped with Nikon® DS-U3, Japan). A semiquantitative analysis according to Hooper et al. (2014) was used to determine histopathological changes in gills and hepatopancreas of Lvpan abalone. The variations assessed in the gills included the level of eosinophilia in the sinus fluid, goblet cell numbers at the tips of the filaments, and the length of epithelial necrosis on the filaments, while interstitial edema and hemocyte infiltration were evaluated in the hepatopancreas.

2.4 Biochemical measurement

Gill and hepatopancreas samples (n=9 per group) were used for biochemical measurements. Each tissue sample (~60 mg) was homogenized on ice in 0.85% NaCl solution at a tissue-to-solution ratio of 1:9 (w/v). The homogenates were used for the determination of biochemical parameters using commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The activities of key antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD, A001-3) and catalase (CAT, A007-1-1), were quantified to assess cellular antioxidant capacity. Additionally, the level of malondialdehyde (MDA, A003-1), a prominent biomarker of lipid peroxidation, was assessed to evaluate the intracellular oxidative stress levels in abalone. Total protein content (A045-4) was measured as a normalization reference for all samples.

2.5 Metabolomic analysis

For metabolomic profiling, gill and hepatopancreas samples (n=9 per group and tissue type) were processed. 100 mg of each tissue sample was ground in liquid nitrogen and then vortexed with 500 µL of prechilled 80% methanol. The samples were incubated on ice for 5 min, followed by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was subsequently transferred to a fresh tube and diluted with LC-MS grade water to a final concentration of 53% methanol. Then, the samples were centrifuged in the conditions above and the supernatant was analyzed using a UHPLC-MS/MS system (Want et al., 2013).

Analyses were performed on a Vanquish™ UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher, Germany) coupled with an Orbitrap Q Exactive™ HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Germany). The separation was achieved using a Hypersil Gold column (100×2.1 mm, 1.9μm, Thermo Fisher, USA) with a 12-min linear gradient at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (eluent A) and methanol (eluent B) with gradient elution as follows: 0 min, 2% B; 1.5 min, 2% B; 3 min, 85% B; 10 min, 100% B; 10.1 min, 2% B; 12 min, 2% B. The Q Exactive™ HF-X mass spectrometer was operated in both positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes with a mass range set to m/z 100–1500, using a data-dependent scan resolution mode. Blank samples, amino acid mixtures, and pooled quality control samples from all samples were used to ensure reproducibility of UHPLC-MS/MS measurements (Lu et al., 2025).

Raw spectral processing, data mining and metabolite identification were conducted using the Compound Discoverer 3.3 software (Thermo Fisher, Germany) with the mzCloud, mzVault and MassList databases, as previously described (Liu et al., 2023). The functions of identified metabolites were annotated against the KEGG, HMDB, and LIPIDMaps databases. Both principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) were performed using the metaX software (Wen et al., 2017), which provided the VIP (Variable Importance in the Projection) value for each metabolite.

2.6 Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses for histopathology and biochemistry were performed using Minitab Version 21 (Minitab LLC, State College, PA, USA). Prior to applying parametric tests, the data were assessed for normality of distribution and homogeneity of variance to validate the assumptions for ANOVA. Normality was evaluated using the Anderson–Darling test, and homogeneity of variance was tested using Levene’s test. For data sets that met these assumptions, one-way ANOVA followed by appropriate post-hoc comparisons (Fisher’s test) was conducted to determine statistically significant differences between groups. For parameters, where data transformations did not achieve normal distribution, non-parametric tests (e.g., Kruskal–Wallis test or Mood test) were applied instead. All results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Graphs represent untransformed data.

All statistical analyses and visualization during metabolomic analysis were performed using R software. Differences between comparison groups were assessed using the Student’s t-test at the univariate level. Metabolites with a VIP > 1.0 and a p < 0.05 were considered significantly different. For clustering heatmaps, the intensity areas of differential metabolites were normalized by conversion to z-scores.

3 Results

3.1 Histopathological alterations

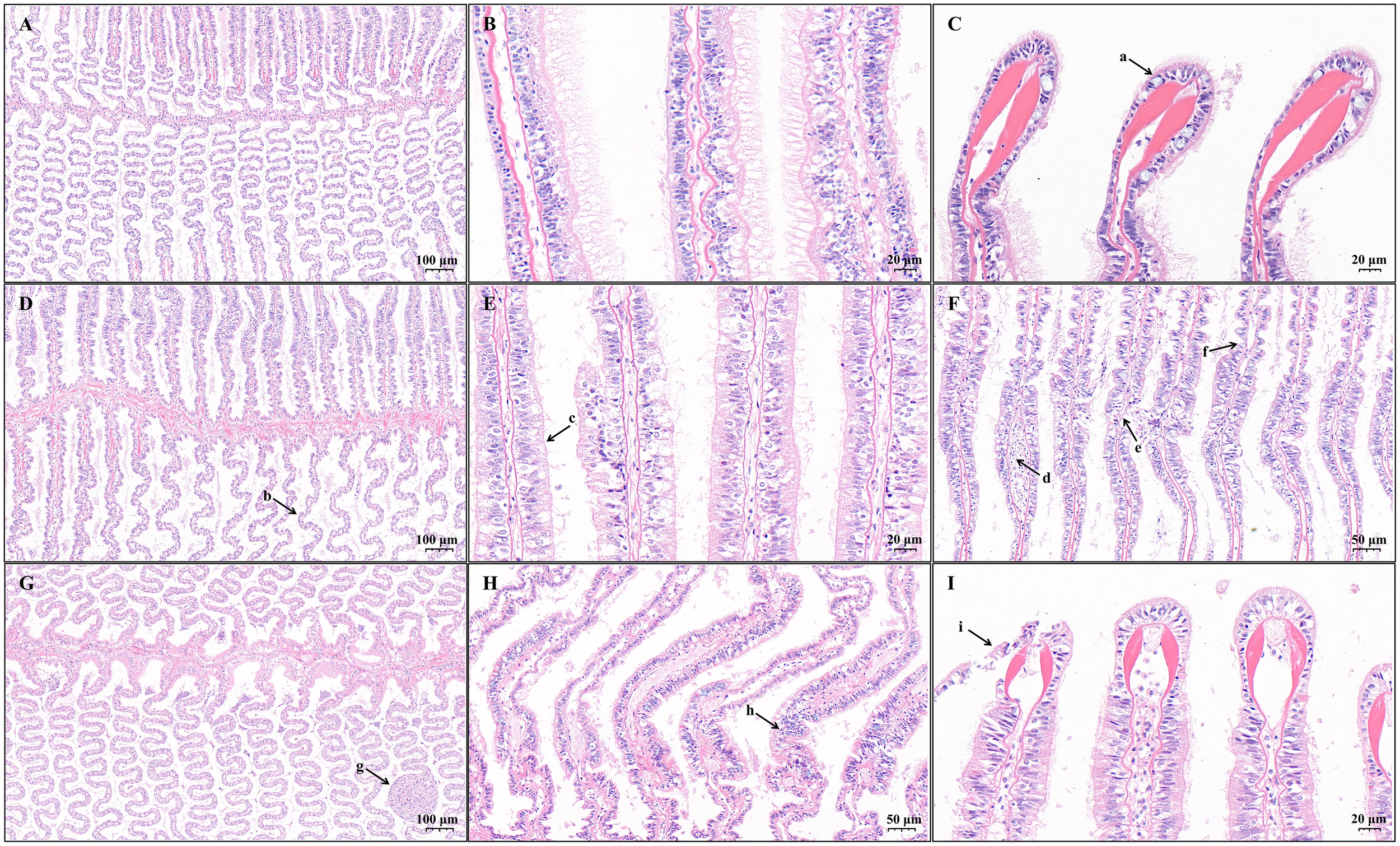

The gill filaments of Lvpan abalone, arranged bilaterally along the central gill axis, are lined with a respiratory epithelium that serves as the principal site of gas exchange in abalone. In the control group, the gill filaments displayed a neat, feather-like alignment along both sides of the gill axis, and the respiratory epithelium formed regular wave-like folds (Figure 1A). Abundant cilia were clearly visible on the lateral surfaces of the filaments (Figure 1B). At the tips of most filaments, mucus-containing goblet cells were observed (Figure 1C). Semiquantitative analysis revealed no significant differences between the control and treatment groups in gill sinus eosinophilia (p = 0.266) or epithelial necrosis (p = 0.105), while goblet cell numbers at the tips of the filaments decreased significantly in the S24 and S48 samples (p = 0.011, Figure 1I). In addition, other distinct pathologies, which were not included in the semiquantitative analysis approach of Hooper et al. (2014), were frequently observed in the treatment groups. These observations included filaments with irregular corrugations (Figure 1D), cilia loss (Figure 1E), epithelial atrophy alongside goblet cell hyperplasia (Figure 1F), vascular occlusion with hemocyte infiltration (Figure 1G), vascular congestion and hemolymph channel enlargement (Figure 1H), and epithelial lifting at V-shaped skeletal rods (Figure 1I).

Figure 1

Light micrographs of gills from Lvpan abalone in the control (A–C) and treatment groups after 24 h (D–F) and 48h (G–I). Arrows indicate: (a) goblet cells containing mucus; (b) irregular corrugations of filaments; (c) cilia loss; (d) enlarged hemolymph channels; (e) epithelial necrosis; (f) epithelial atrophy accompanied by goblet cell hyperplasia; (g) vascular occlusion with hemocyte infiltration; (h) vascular congestion and hemolymph channel enlargement; (i) epithelial lifting at V-shaped skeletal rods.

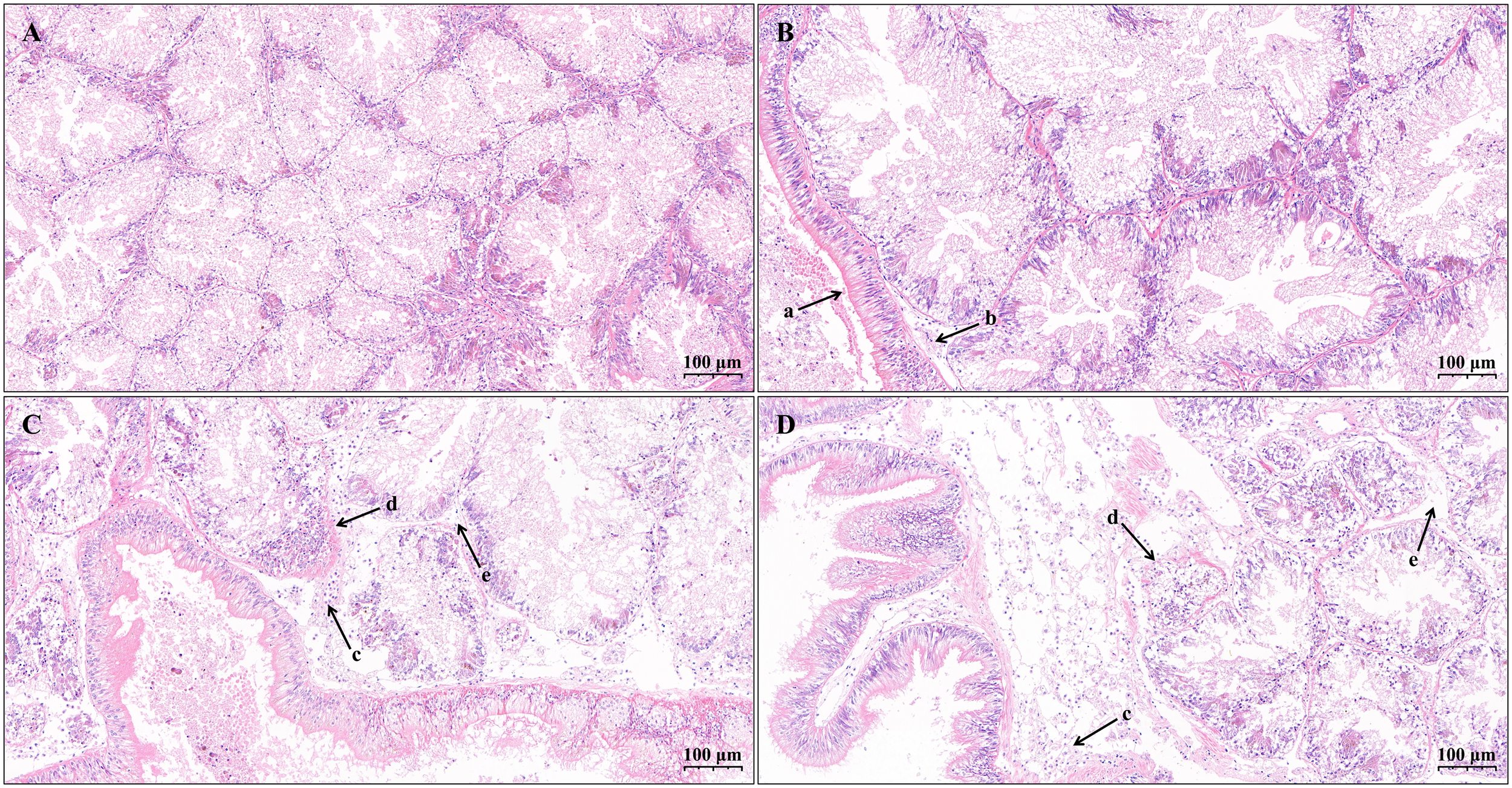

The hepatopancreas of Lvpan abalone is primarily composed of numerous spherical or irregularly shaped hepatopancreatic tubules. In the control group, the hepatopancreatic tubules were compactly organized with well-defined boundaries (Figures 2A, B). Significant structural alterations were observed after exposure to K. mikimotoi and hypoxia (Figures 2C, D). A progressive worsening of both interstitial edema and hemocyte infiltration was observed in the S24 and S48 groups (Supplementary Figure S1, p < 0.05). The edema extended from the interstitium surrounding individual hepatopancreatic tubule to the periphery between the basement membrane and the capsule (Figures 2C, D).

Figure 2

Light micrographs of hepatopancreas from Lvpan abalone in the control (A, B) and treatment groups after 24 h (C) and 48h (D). Arrows indicate: (a) the capsule; (b) mild peripheral edema; (c) extensive peripheral edema with hemocyte infiltration; (d) regions with indistinct tubule boundaries; (e) internal edema between adjacent tubules.

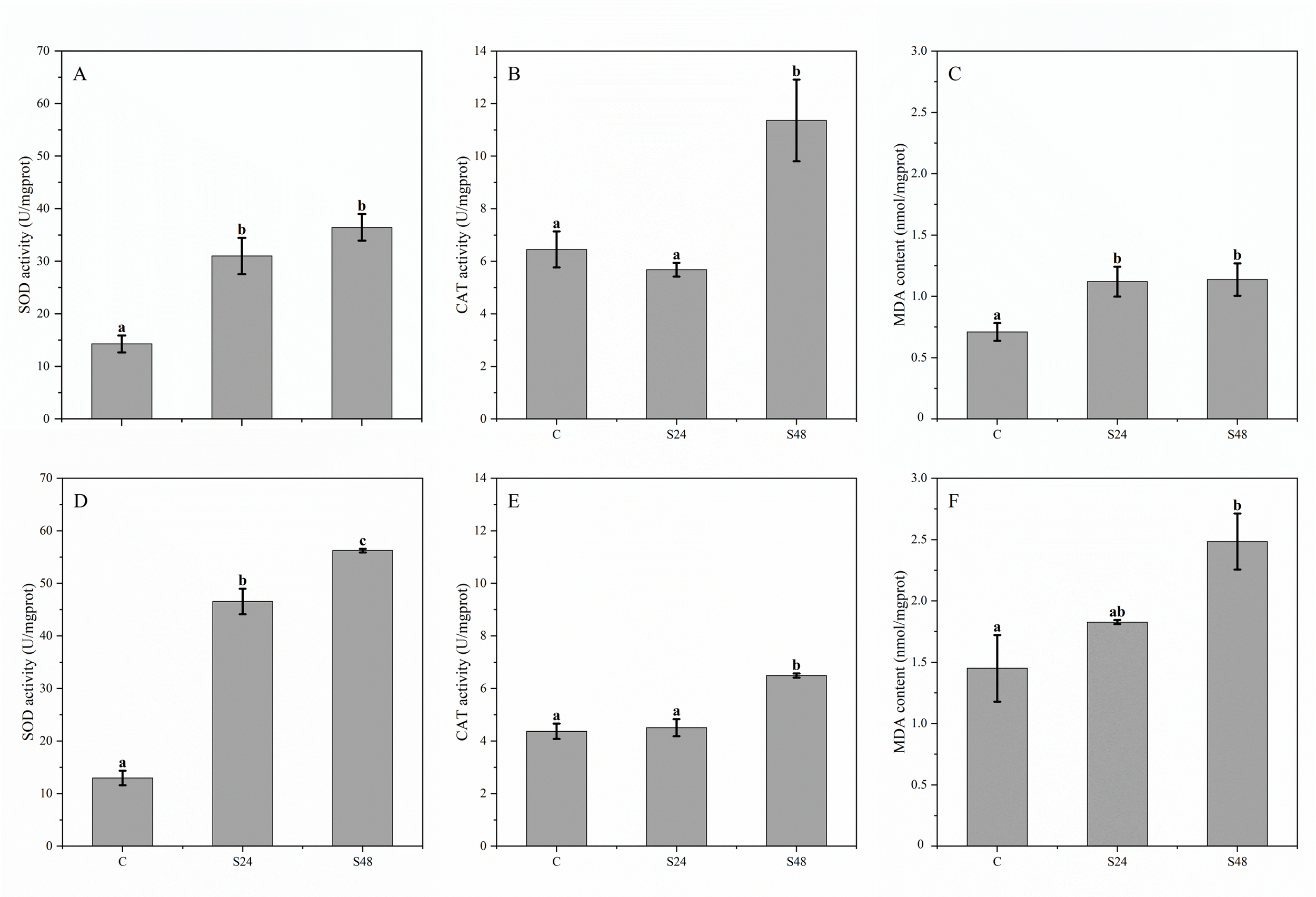

3.2 Oxidative stress responses

Exposure to K. mikimotoi blooms triggered a progressive oxidative stress response in Lvpan abalone. After 24 h, SOD activity increased significantly in both gills and hepatopancreas (Figures 3A, D, p < 0.05), and MDA content increased in gills (Figure 3C, p < 0.05). The oxidative stress response was more pronounced by 48 h, with significant increases in SOD activity, CAT activity, and MDA content in both tissues compared to the control group (Figure 3, p < 0.05).

Figure 3

Enzyme activities and biochemical indices in the gills (A–C) and hepatopancreas (D–F) of Lvpan abalone. Abscissa: C, control group; S24/S48, treatment group (24 h/48 h). Groups that do not share a letter indicate significant difference (Fisher’s test, p < 0.05).

3.3 Metabolic adaptations

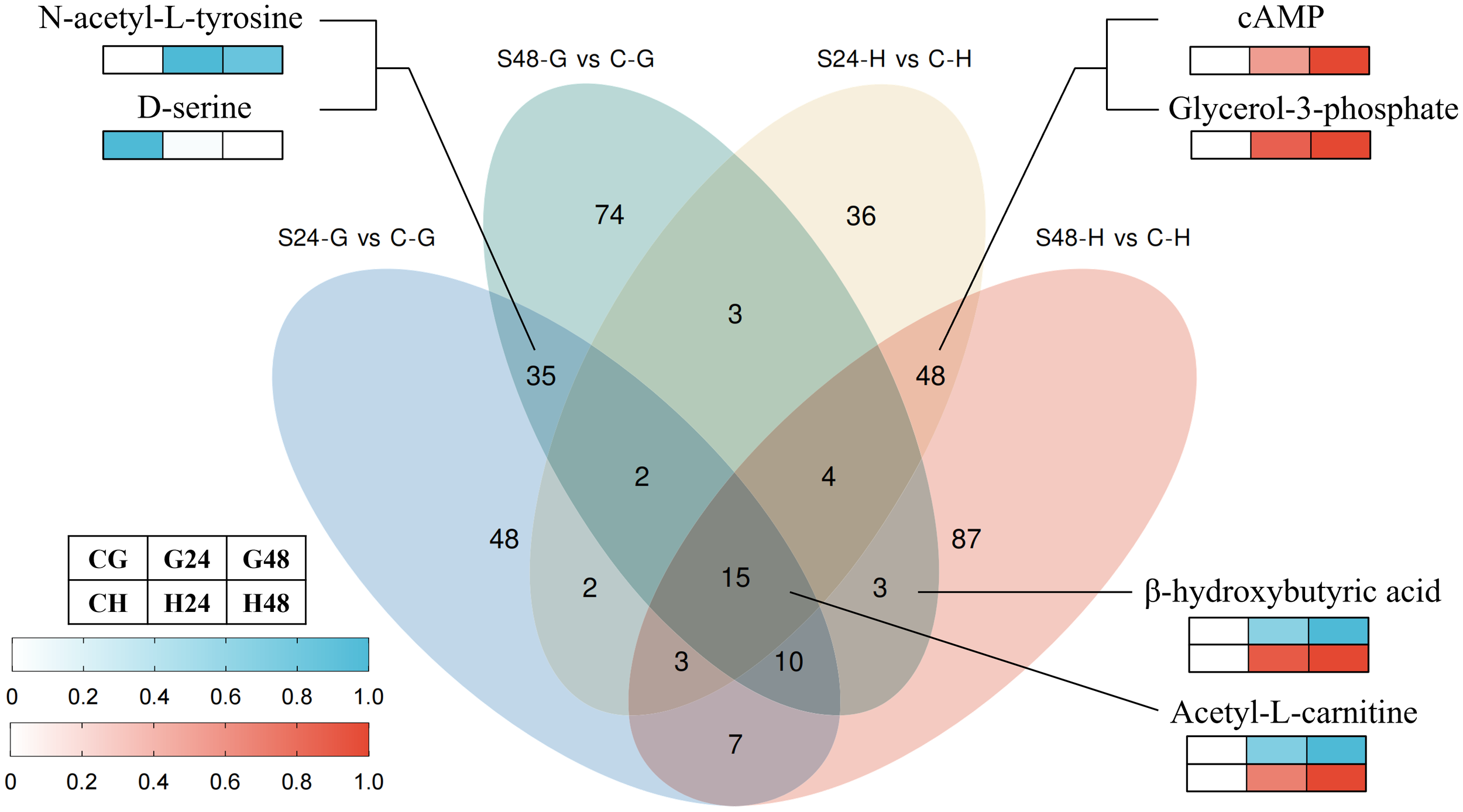

A total of 1050 annotated metabolites were identified in all samples, most of which were lipids and lipid-like molecules, organic acids and their derivatives, and organoheterocyclic compounds. Compared with the control group, the gill tissue exhibited 122 and 146 differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) at 24 h and 48 h, respectively (p < 0.05). In hepatopancreas samples, 113 DEMs were identified at 24 h, increasing to 177 at 48 h.

To investigate tissue-specific metabolic variations over time, Venn diagram analysis was conducted (Figure 4). The results revealed 35 DEMs that were significantly altered in gill tissue at both time points, including representative metabolites such as N-acetyl-L-tyrosine and D-serine. These shared gill metabolites exhibited no significant changes in the hepatopancreas and were therefore considered gill-specific DEMs. Similarly, 48 hepatopancreas-specific DEMs were identified, including key representatives such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and glycerol-3-phosphate (Gro3P). Notably, 15 metabolites were significantly altered in all stress-exposed groups compared to controls, including acetyl-L-carnitine. These metabolites may serve as pivotal regulatory nodes in mediating abalone’s adaptive physiological responses to environmental stressors.

Figure 4

Venn diagrams and representative differentially expressed metabolites. S24-G/S48-G, treatment group (24 h/48 h, gills). S24-H/S48-H, treatment group (24 h/48 h, hepatopancreas). C-G/C-H: control group (gills/hepatopancreas).

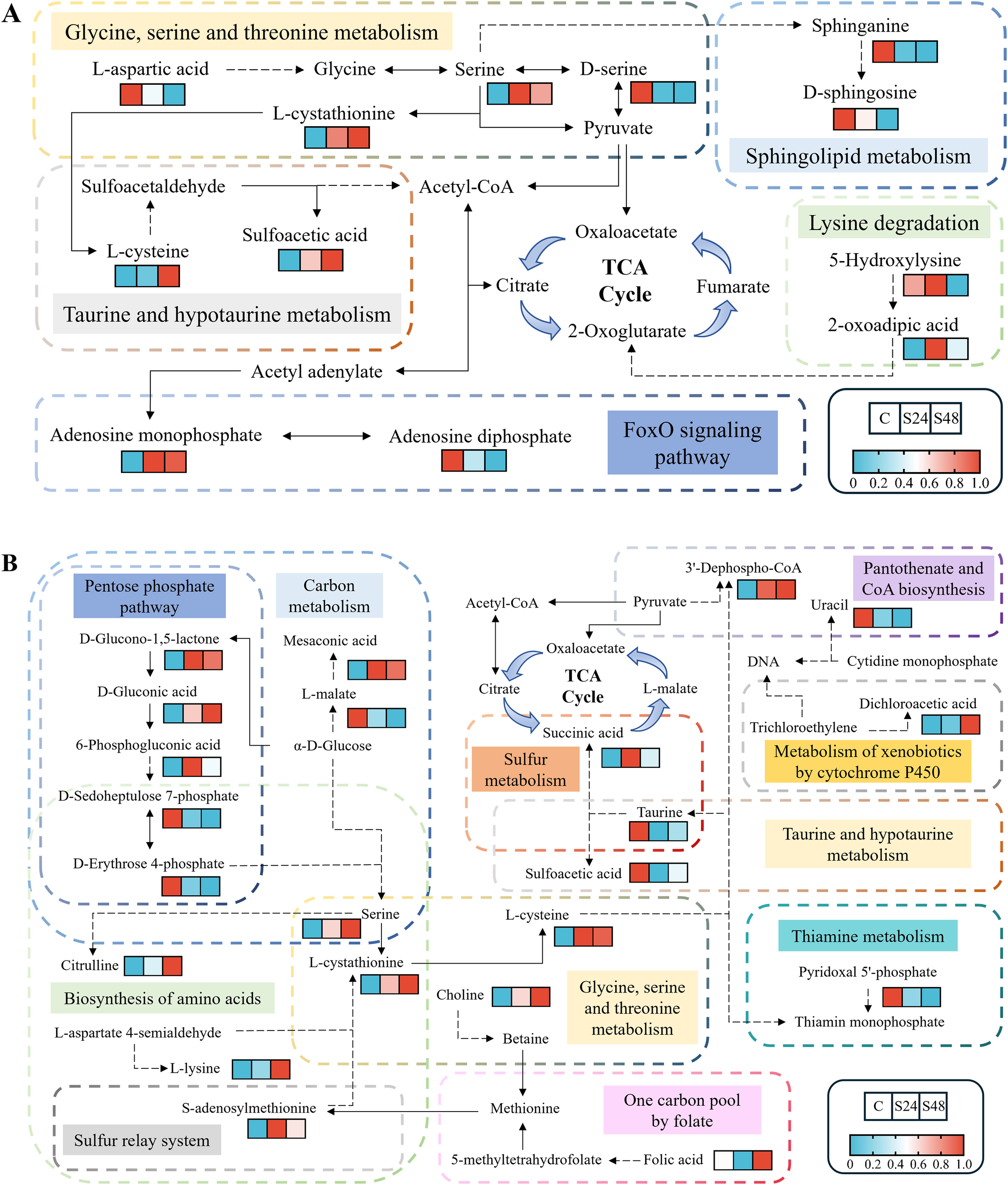

Based on KEGG pathway enrichment and heatmap analyses of DEMs in gill tissues (Figure 5A), the glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism pathway was enriched in S24-vs-C. Within this pathway, levels of serine and L-cystathionine increased significantly, while those of D-serine and L-aspartic acid markedly decreased. In S48-vs-C, DEMs were significantly enriched in the sphingolipid metabolism pathway and the FoxO signaling pathway. Specifically, sphinganine and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) levels decreased notably, whereas adenosine monophosphate (AMP) increased significantly. Furthermore, taurine and hypotaurine metabolism, and lysine degradation were enriched in S48-vs-S24. In these pathways, a marked increase in L-cysteine was observed, while 2-oxoadipic acid increased significantly at 24 h but decreased at 48 h.

Figure 5

Metabolic profiles within significantly enriched KEGG pathways of differentially expressed metabolites in gills (A) and hepatopancreas (B). C, control group; S24/S48, treatment group (24 h/48 h).

Compared to the gills, the hepatopancreas exhibited a notable increase in the number of significantly enriched KEGG pathways (Figure 5B). In S24, five pathways were prominently enriched: sulfur metabolism, carbon metabolism, taurine and hypotaurine metabolism, pentose phosphate pathway, and pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis. The S48 group showed enrichment in six pathways: carbon metabolism, biosynthesis of amino acids, pentose phosphate pathway, glycine, serine and threonine metabolism, thiamine metabolism, and sulfur relay system. Additionally, in S48-vs-S24, one carbon pool by folate and metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 were also enriched. The hepatopancreas had a higher abundance of DEMs, and those shared with gill tissue displayed largely consistent change trends.

4 Discussion

4.1 Gill and hepatopancreas lesions caused by K. mikimotoi blooms

As the primary respiratory organs in mollusks, gills may suffer structural and functional disruptions under toxic and hypoxic stress, leading to reduced energy metabolism efficiency and impaired immuno-physiological functions. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that that K. mikimotoi damaged the gill cells of H. diversicolor by inducing the proliferation of rough endoplasmic reticulum, lysis of hemocyanin, and deformation of blood sinusoids and gland cells, thereby leading to insufficient oxygen supply and mass mortality of abalone (Xie, 2016). Furthermore, apparent shrinkage and deformation of the afferent and efferent branchial vessels, as well as broken gill filaments, were observed in Pacific abalone exposed to K. mikimotoi FJ-strain at a density of 1 × 107 cells/L. These pathologies were attributed to hemolytic toxins produced by K. mikimotoi (Liao et al., 2024). Harris et al. (1998), reported that in H. laevigata Donovan, long-term nitrite exposure induces chronic gill changes (lamellar thickening, epithelial lifting, and mucous cell proliferation), while low dissolved oxygen causes direct pathological damage including necrosis and altered mucus composition. This damage, combined with immune compromise, increases parasitic susceptibility, creating a vicious cycle of tissue damage and hypoxia that ultimately results in significantly reduced survival. However, neither quantitative nor semiquantitative assessment of histopathological slides was conducted in these studies, making it impossible to establish significant relationships between abalone lesions and exposure to toxins or hypoxia.

In our study, goblet cell numbers at the tips of the filaments decreased significantly in the S24 and S48 samples, while epithelial atrophy co-occurring with goblet cell hyperplasia appeared to exacerbate in other regions. This suggests a complex interplay of pathological damage and compensatory defense mechanisms. Goblet cells are secretory cells in the epithelium that synthesize and secrete mucins. Mucins prevent direct contact between the gills and the environment, as well as fusion of adjacent gill filaments (Riera-Ferrer et al., 2024). The severe loss of goblet cells at the tips is likely a direct result of toxin-induced damage and oxidative stress, consistent with lesions described in the snail Bellamya bengalensis under toxicant exposure (Londhe and Kamble, 2013). This loss poses a triple threat: (1) increased mechanical damage due to reduced lubrication; (2) heightened exposure to toxicants and pathogens from impaired immune defense; and (3) hindered excretion of metals (Martins et al., 2015). However, in the context of hypoxia, this reduction may also represent a paradoxical adaptive strategy to minimize the diffusion barrier and enhance gaseous exchange efficiency (Mistri et al., 2016; Riera-Ferrer et al., 2024). Concurrently, the observed hyperplasia of goblet cells in other areas of the filament appears to be a compensatory response aimed at increasing mucous secretion to trap harmful particles and prevent filament fusion. Yet, this comes at the cost of impaired oxygen uptake due to epithelial thickening, creating a physiological trade-off. This redistribution of goblet cells underscores a disrupted balance between gas exchange and pathogen defense, ultimately contributing to a vicious cycle of gill dysfunction under combined stressors.

The hepatopancreas of abalone plays a vital role in digestion, energy storage, detoxification, immune response, and metabolic regulation. Under normal conditions, hepatopancreatic tubules exhibit tightly packed arrangements with distinct boundaries (Meusel et al., 2022). However, environmental stressors such as tributyltin and Haliotid herpesvirus-1 infection have been shown to induce pathological changes in the hepatopancreas of H. diversicolor supertexta, including granular degeneration, cell swelling, vacuolation, and inflammatory infiltration (Bai et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2010). In this study, combined exposure to K. mikimotoi and hypoxia similarly disrupted the hepatopancreatic architecture in Lvpan abalone, resulting in interstitial edema and hemocyte infiltration (Figures 2C, D), indicating severe functional compromise. First, the digestive and absorptive functions are severely compromised as edema fluid separates hepatopancreatic tubules, impeding enzyme secretion and nutrient uptake, while hemocyte infiltration directly destroys the digestive epithelium. Second, the organ’s energy storage role is impaired; hypoxia forces cells into catabolism, depleting reserves, and the energetic cost of the immune response diverts resources away from storage. Finally, the detoxification capacity is overwhelmed because the synthesis of detoxification enzymes is suppressed by both hypoxia and resource competition, while the infiltration itself adds endogenous toxins to the load. Together, these pathologies disrupt digestion, energy storage, and detoxification, ultimately reducing Lvpan abalone resilience to K. mikimotoi bloom stress.

4.2 Enhancement of antioxidant capacity and energy homeostasis in gills

Under acute stress (DO: 2 mg/L, K. mikimotoi FJ-strain: 3×106 cells/L, 24h), the SOD activity in the gills of Pacific abalone decreased significantly, indicating that its antioxidant system was compromised at the early stage of exposure (Zhang et al., 2023b). In contrast, its hybrid offspring, the Lvpan abalone, maintained an inducible antioxidant defense under a more severe scenario (DO: 2 mg/L, K. mikimotoi FJ-strain: 1×107 cells/L, 48h). Although the MDA content increased significantly, confirming oxidative damage, the activities of both SOD and CAT rose markedly. This sustained antioxidant capacity demonstrates that Lvpan abalone exhibits greater physiological tolerance to K. mikimotoi blooms compared to its maternal parent, as its defense system remained responsive despite the presence of gill lesions.

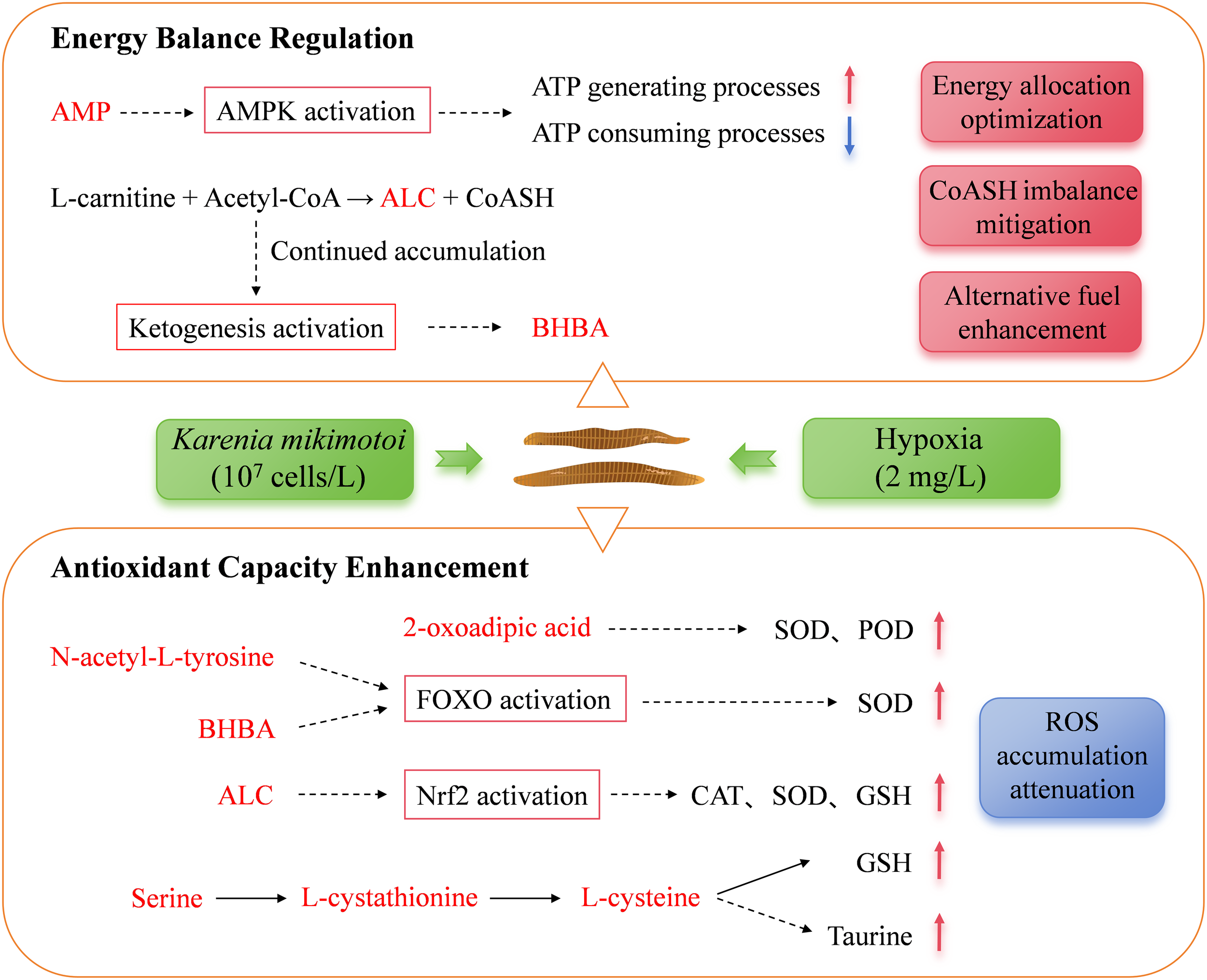

Metabolomics provided molecular insights into the underlying responses of Lvpan abalone under oxidative stress. Sphinganine, a critical component of sphingolipids essential for membrane integrity, was reduced in gills after 24-h exposure to K. mikimotoi and hypoxia (Figure 5A). This decline likely impairs membrane fluidity and permeability, increasing susceptibility to oxidative damage and diminishing stress resilience (Quinville et al., 2021). To counteract oxidative stress, serine and 2-oxoadipic acid levels increased in gills (Figure 5A), which may enhance antioxidant capacity by modulating the activities or levels of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and peroxidase (Figure 6) (He et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023a).

Figure 6

Metabolic adaptation in the gills of Lvpan abalone during a K. mikimotoi bloom. AMP, adenosine monophosphate; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ALC, acetyl-L-carnitine; BHBA, β-hydroxybutyric acid; SOD, superoxide dismutase; POD, Peroxidase; CAT, catalase activity; GSH, reduced glutathione. Metabolites shown in red were identified as significantly increased in this study.

A significant elevation in AMP and a reduction in ADP within the FoxO signaling pathway (Figure 5A) indicated cellular energy deficit, triggering allosteric activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Venter et al., 2018a). This activation was further supported by the significant upregulation of AMPK-related genes in gills at 24 h (Supplementary Figure S2). Activated AMPK promotes ATP-generating pathways (e.g., fatty acid oxidation) and suppresses non-essential ATP-consuming processes for survival (e.g., cell proliferation, protein and triglyceride synthesis), thereby helping to maintain energy balance under hypoxia (Sharma et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022). The significant downregulation of gene K02209 (encoding minichromosome maintenance protein 5, MCM5) further supports that AMPK activation suppressed cell proliferation (Supplementary Figure S2). As a critical factor for initiating and extending DNA replication, the reduction of MCM5 would directly impede cell division (Wu et al., 2021). AMPK also enhances FOXO transcriptional activity, leading to the upregulation of antioxidant enzymes, promotion of autophagy, and inhibition of apoptosis, collectively alleviating oxidative injury and maintaining tissue homeostasis (Guan et al., 2025). The anti-apoptotic effect was further corroborated by the significant upregulation of gene K05143, which encodes Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6B (TNFRSF6B, Supplementary Figure S2). TNFRSF6B is an endogenous immunomodulator that inhibits apoptosis by interfering with the activation of multiple signaling pathways (Huang et al., 2025). Additionally, N-acetyl-L-tyrosine, another elevated metabolite in gills (Figure 4), has been reported to activate FOXO transcription factors (Matsumura et al., 2020), suggesting a synergistic role in reinforcing cellular stress adaptation (Figure 6).

At 48 h, L-cysteine and its precursor L-cystathionine accumulated in gills (Figure 5A). As precursors for the antioxidants taurine and reduced glutathione (GSH), their elevation likely alleviates oxidative stress (Liu et al., 2024; Surai et al., 2021). Concurrently, β-hydroxybutyric acid (BHBA) was significantly elevated at 48 h (Figure 4). BHBA mitigates oxidative damage by reducing pro-oxidative markers (e.g., ROS, nitrites), promoting FOXO3A and metallothionein-2 expression, and elevating GSH levels (Majrashi et al., 2021; Shimazu et al., 2013). Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALC), another critical metabolite elevated in gills at both 24 h and 48 h (Figure 4), attenuates oxidative injury by enhancing endogenous antioxidant defenses and suppressing lipid peroxidation (Sepand et al., 2016).

Beyond their antioxidant roles, both ALC and BHBA play a crucial role in maintaining metabolic homeostasis during hypoxia. The inhibition of fatty acid β-oxidation and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle under hypoxic stress causes mitochondrial accumulation of acyl-coenzyme A and acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which sequesters the essential metabolic cofactor free CoA (CoASH). To counteract this imbalance, L-carnitine binds to excess acetyl-CoA to form ALC, thereby releasing CoASH (Hanai et al., 2020; Malaguarnera et al., 2006). Consequently, the observed increase in ALC levels, previously reported in H. midae, Pacific abalone, and Lvpan abalone under hypoxia within 24h (Venter et al., 2018b; Shen et al., 2021), represents an immediate response that restores metabolic homeostasis by regulating the acetyl-CoA/CoASH ratio. While this mechanism appears conserved across abalone species, the sustained ALC accumulation in Lvpan abalone from 24h to 48h may indicate a robust homeostatic adjustment in this hybrid. As hypoxia persisted, the continued accumulation of acetyl-CoA activated ketogenesis as a delayed response, leading to a significant increase in BHBA by 48 h (Figure 4). Beyond alleviating mitochondrial stress, BHBA serves as an alternative fuel to maintain the function of vital organs during a systemic energy crisis (Majrashi et al., 2021). Thus, the sequential elevation of ALC and BHBA in Lvpan abalone gills reveals an orchestrated metabolic defense strategy to counteract the combined oxidative and energetic challenges of a simulated K. mikimotoi bloom.

4.3 Multipronged metabolic adaptation in hepatopancreas

Both the present study and Zhang et al. (2018) found that the basal activity of CAT in the abalone hepatopancreas (Figures 3B, E) was lower than that in the gill tissue, while the basal levels of SOD were comparable between the two tissues (Figures 3A, D). This suggests an inherently weaker capacity of the hepatopancreas to clear hydrogen peroxide via CAT. Following exposure to K. mikimotoi blooms, the hepatopancreas exhibited a more pronounced increase in both SOD activity and MDA content compared to the gills (Figures 3A, C, D, F), indicating that it experienced more severe oxidative stress. Notably, the corresponding increase in CAT activity in the hepatopancreas was relatively limited compared to that in the gills. This pattern implies that the clearance of hydrogen peroxide, which is generated by SOD activity, may represent a rate-limiting step in the antioxidant defense of this organ. Collectively, these results suggest that the hepatopancreas is a primary target organ during K. mikimotoi and hypoxia exposure, and that an uncoordinated response within its intrinsic antioxidant enzyme system is a key mechanism underlying its heightened susceptibility to oxidative damage.

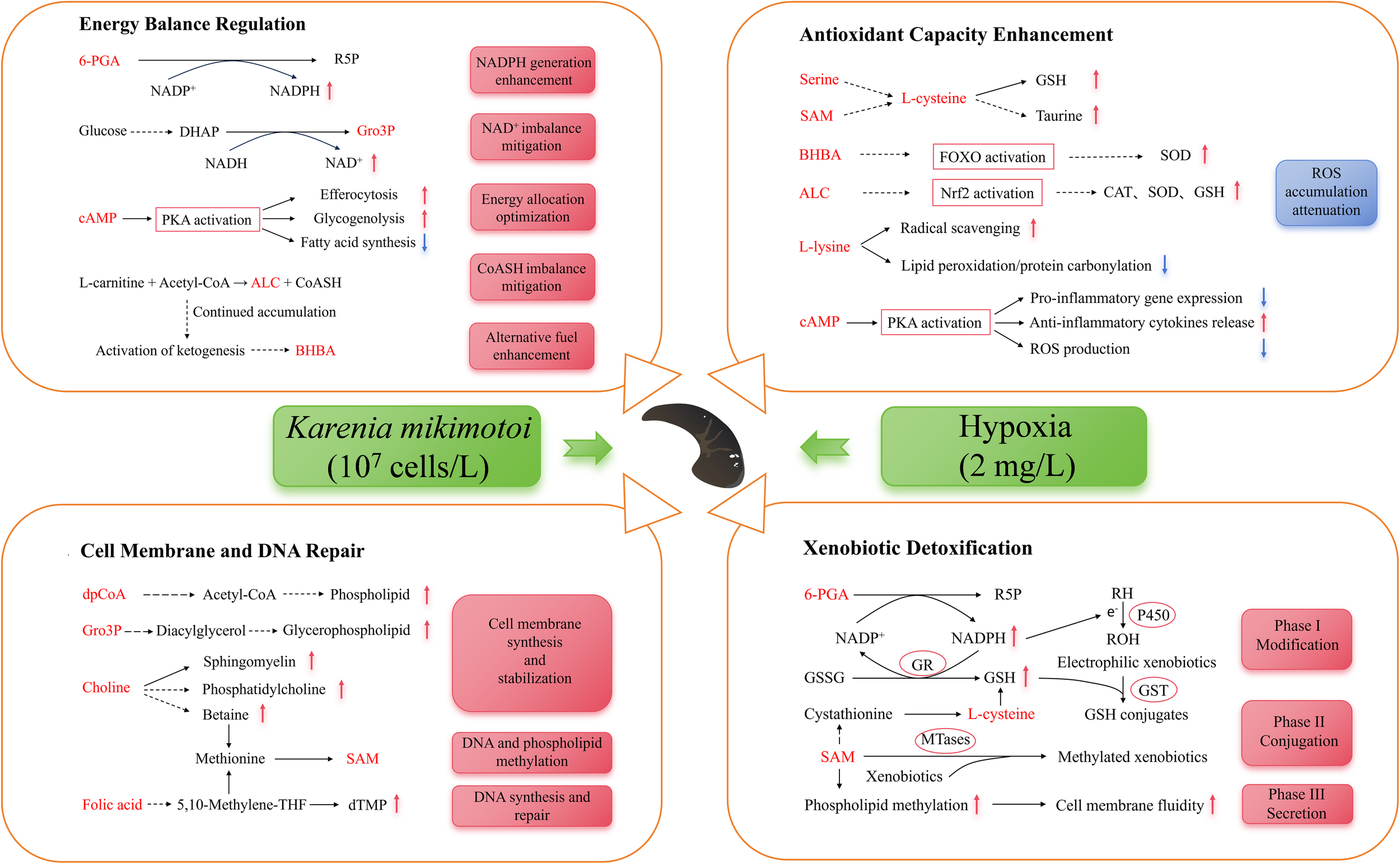

Metabolomic analysis revealed that the hepatopancreas mirrored the trends in the gills and also accumulated serine, L-cysteine, BHBA, and ALC. These metabolites contributed to the upregulation of key antioxidants (e.g., GSH and SOD), thereby enhancing ROS elimination capacity (Figure 7). This metabolic response was further supported by a concomitant increase in SOD and CAT enzymatic activities (Figures 3D, E). Additionally, elevated L-lysine levels may further support antioxidant defenses through direct radical scavenging and prevention of lipid peroxidation/protein carbonylation (Huang et al., 2021; Olin-Sandoval et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2018). Nevertheless, a significant increase in MDA levels (Figure 3F) indicated that ROS production had overwhelmed cellular antioxidant capacity, ultimately leading to the observed histological damage.

Figure 7

Metabolic adaptation in the hepatopancreas of Lvpan abalone in a K. mikimotoi bloom. 6-PGA, 6- phosphogluconic acid; R5P, ribulose-5-phosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; Gro3P, glycerol-3-phosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PKA, protein kinase A; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; BHBA, β-hydroxybutyric acid; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase activity; GSH, reduced glutathione; ALC, acetyl-L-carnitine; dpCoA, 3’-dephospho-CoA; dTMP, deoxythymidine monophosphate; RH, lipophilic substances; ROH, epoxides; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; GR, glutathione reductase; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; MTases, SAM-dependent methyltransferase. Metabolites shown in red were identified as differentially expressed in this study.

The hepatopancreatic detoxification response relies on the coordinated action of key enzymes, including cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP450) in Phase I, various transferases (e.g., glutathione S-transferases, UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, methyltransferases) in Phase II, and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in Phase III (Byeon et al., 2022). Our findings indicate a specific metabolic adaptation within this system under 24-h exposure, centered on enhanced NADPH production. The significant accumulation of 6-Phosphogluconic acid (6-PGA) indicates an upregulation of the pentose phosphate pathway, aimed at boosting NADPH production (Figure 7, Phégnon et al., 2024). This is critically significant because NADPH serves as an essential cofactor for both CYP450-mediated Phase I detoxification (Wei et al., 2025) and the glutathione reductase-mediated regeneration of GSH, which is essential for Phase II conjugation and ROS scavenging (Georgiou-Siafis and Tsiftsoglou, 2023; Moreno-Sánchez et al., 2018). This adaptive response is further corroborated by the accumulation of dichloroacetic acid (Figure 5B), a terminal metabolite that provides direct evidence of heightened CYP450-mediated biotransformation. Thus, the rise in both 6-PGA and dichloroacetic acid suggests a coherent adaptive response where increased NADPH biosynthesis sustains the activity of core detoxification enzymes to mitigate xenobiotic stress.

Under dual stress from K. mikimotoi and hypoxia, the hepatopancreas of Lvpan abalone exhibits a coordinated response mechanism via one-carbon metabolism, characterized by significant upregulation of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), choline, and folic acid at 48 h (Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017). As the primary methyl donor, SAM orchestrates detoxification through three mechanisms (Figure 7): (1) SAM-dependent methyltransferases, including catechol-O-methyltransferase and As(III) S-adenosylmethionine methyltransferases, utilize SAM to methylate xenobiotics (e.g., catechols and arsenic), enhancing their hydrophilicity for efficient excretion (Li et al., 2021); (2) SAM acts as a GSH precursor while upregulating glutathione-S-transferase to facilitate toxin-GSH conjugation (Sandamalika et al., 2019); (3) SAM enhances membrane fluidity via phospholipid methylation, optimizes the conformational dynamics of transport proteins, and thereby facilitates the efflux of toxic metabolites. In addition, elevated SAM levels, as a key methyl donor, enhance cellular resilience in Lvpan abalone by supporting membrane phospholipid synthesis and enabling the epigenetic regulation of DNA repair genes (Goicoechea et al., 2024). Altogether, the elevated SAM level orchestrates a comprehensive defense strategy in Lvpan abalone, ranging from the repair of cellular membranes and DNA to the potentiation of antioxidant and detoxification pathways in the hepatopancreas. Choline and folic acid maintain SAM homeostasis by replenishing methyl groups via their metabolites, betaine and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, respectively (Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017). As a precursor of sphingomyelin, phosphatidylcholine, and betaine, choline plays an important role in restoring membrane integrity and regulating intracellular osmotic pressure under stress (Kenny et al., 2025). This adaptive choline elevation mirrors findings in hypoxia-exposed H. midae (Venter et al., 2018b). Folic acid, through its bioactive form tetrahydrofolate, serves as a one-carbon unit carrier to enable the synthesis of thymine and other nucleotides, which are indispensable for DNA replication and repair processes (Asbaghi et al., 2021). The coordinated enhancement of choline and folic acid metabolism observed in this study suggests a synergistic strategy in Lvpan abalone to reinforce cellular integrity and genomic stability under the combined stress of K. mikimotoi and hypoxia.

In Lvpan abalone, energy metabolism was significantly reprogrammed under stress. Under normoxia, the abalone predominantly relies on the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) for efficient ATP synthesis, employing molecular oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor (Venter et al., 2022). Hypoxia, however, disrupts ETC function, triggering an energy crisis. In response, Lvpan abalone reprograms its metabolism to support compensatory energy production. As a key intermediate of the TCA cycle and the end-product of the glucose/aspartate-succinate pathway (a glycolytic bypass pathway), succinic acid accumulated in hepatopancreatic samples of Lvpan abalone at 24 h, which aligns with observations in hypoxia-exposed H. midae and H. iris (Alfaro et al., 2021; Venter et al., 2018b). This suggests that Lvpan abalone enhances glycolytic flux to sustain ATP production under oxygen-limited conditions where oxidative phosphorylation is suppressed.

NAD+, a critical electron acceptor in metabolic pathways (e.g., TCA cycle, glycolysis), requires oxygen-dependent regeneration via the respiratory chain to maintain the NADH/NAD+ balance. Hypoxia-induced ETC inhibition leads to NAD+ depletion, disrupting glycolysis due to NADH/NAD+ imbalance (Xiao and Loscalzo, 2020). Previous research has shown that hypoxia activates the glucose-driven Gro3P synthesis pathway as an endogenous NAD+ regeneration mechanism (Liu et al., 2021). Therefore, the significant elevation of Gro3P levels in Lvpan abalone hepatopancreas (Figure 4) helps alleviate NAD+ depletion to sustain glycolysis under hypoxic stress. In addition, Gro3P acts as a precursor for glycerophospholipid synthesis (Possik et al., 2021), enabling membrane repair and preventing energy loss from ion leakage. This dual mechanism supports both metabolic regulation and structural maintenance (Figure 7). Similarly, elevated 3’-Dephospho-CoA levels enhance acetyl-CoA production (Figure 5B), fueling fatty acid synthesis and membrane phospholipid regeneration to mitigate oxidative stress damage (De Carvalho and Caramujo, 2018).

As a hepatopancreas-specific DEM, cAMP increased progressively in Lvpan abalone (Figure 4). cAMP activates protein kinase A, exerting multifaceted protective effects (Figure 7): (1) suppressing pro-inflammatory gene expression, promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines release, reducing ROS generation; (2) stimulating efferocytosis to eliminate dysfunctional cells, and optimizing energy allocation (Tavares et al., 2020); (3) activating glycogen phosphorylase to accelerate glucose production via glycogenolysis, repressing ATP-consuming processes like lipogenesis, thereby balancing energy homeostasis (Wahlang et al., 2018). Concurrently, hypoxia promotes more glucose entering the pentose phosphate pathway (Wang et al., 2023), as evidenced by elevated 6-PGA in hepatopancreatic S24 samples (Figure 5B). This metabolic shift boosts NADPH production, critical for counteracting oxidative stress and preserving mitochondrial redox balance, thereby safeguarding ATP generation under oxygen limitation.

5 Conclusions

In response to an extreme K. mikimotoi bloom (DO: 2 mg/L, algal density: 1×10⁷ cells/L), Lvpan abalone exhibited significant histopathological damage and oxidative stress in both gill and hepatopancreas tissues. Our integrated analysis revealed that Lvpan abalone activated a suite of metabolic adaptations to preserve homeostasis, including bolstering antioxidant defenses, repairing cellular membranes, clearing damaged cells, and shifting toward anaerobic metabolism to meet energy demands. Notably, the synergistic accumulation of BHBA and ALC contributed to reducing oxidative stress and regulating energy balance. Furthermore, the hepatopancreas demonstrated an increased capacity for detoxification, especially through elevated levels of SAM. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that Lvpan abalone utilizes a complex metabolic network to mitigate K. mikimotoi bloom stress. However, when the intensity or duration of the stress exceeds its physiological compensatory threshold, severe oxidative damage and structural tissue disruption become inevitable, leading to mortality. Therefore, this study not only elucidates the key adaptive mechanisms in Lvpan abalone but also underscores the importance of implementing early warning and intervention strategies in aquaculture before these compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed. Future studies should explore how the intensity and duration of stress induced by K. mikimotoi blooms affect the physiology of Lvpan abalone.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by The Ethical Committee of Minjiang University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

HL: Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. XX: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Data curation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YZ: Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. JL: Funding acquisition, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. QZ: Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. ZD: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. YW: Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft. PZ: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft. JY: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (grant number 2022J011137), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42306179), the Scientific Research Project of No.2 Bureau of China Metallurgical Geology Bureau (grant number CMGB02KY202302), Fashu Charity Foundation Research Project (grant number MFK23015), and Open Project of Fujian Key Laboratory on Conservation and Sustainable Utilization of Marine Biodiversity, Minjiang University (grant number CSUMBL2024-2).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1702024/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Alfaro A. C. Nguyen T. V. Venter L. Ericson J. A. Sharma S. Ragg N. L. C. et al . (2021). The effects of live transport on metabolism and stress responses of abalone (Haliotis iris). Metabolites.11, 748. doi: 10.3390/metabo11110748

2

Asbaghi O. Ghanavati M. Ashtary-Larky D. Bagheri R. Rezaei Kelishadi M. Nazarian B. et al . (2021). Effects of folic acid supplementation on oxidative stress markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Antioxidants.10, 871. doi: 10.3390/antiox10060871

3

Bai C. M. Li Y. N. Chang P. H. Jiang J. Z. Xin L. S. Li C. et al . (2019). Susceptibility of two abalone species, Haliotis diversicolor supertexta and Haliotis discus hannai, to Haliotid herpesvirus 1 infection. J. Invertebr Pathol.160, 26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2018.11.008

4

Brand L. E. Campbell L. Bresnan E. (2012). Karenia: The biology and ecology of a toxic genus. Harmful Algae.14, 156–178. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.020

5

Byeon E. Kim M. S. Lee Y. Lee Y. H. Park J. C. Hwang U. K. et al . (2022). The genome of the freshwater monogonont rotifer Brachionus rubens: Identification of phase I, II, and III detoxification genes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D.42, 100979. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2022.100979

6

Chen B. H. Wang K. Guo H. G. Lin H. (2021). Karenia mikimotoi blooms in coastal waters of China from 1998 to 2017. Estuar. Coast. ShelfS. 249, 107034. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2020.107034

7

Cook P. A. (2023). Worldwide abalone production: an update. New Zeal J. Mar. Fresh.59, 4–10. doi: 10.1080/00288330.2023.2261869

8

Dai Y. Shen Y. W. Liu Y. B. Xia W. W. Hong J. W. Gan Y. et al . (2024). A high throughput method to assess the hypoxia tolerance of abalone based on adhesion duration. Aquaculture.590, 741004. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741004

9

De Carvalho C. C. C. R. Caramujo M. J. (2018). The various roles of fatty acids. Molecules.23, 2583. doi: 10.3390/molecules23102583

10

Ducker G. S. Rabinowitz J. D. (2017). One-carbon metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab.25, 27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.009

11

Dutra F. M. Rönnau M. Sponchiado D. Forneck S. C. Freire C. A. Ballester E. L. C. (2017). Histological alterations in gills of Macrobrachium amazonicum juveniles exposed to ammonia and nitrite. Aquat Toxicol.187, 115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.04.003

12

Gao X. L. Pang G. W. Luo X. You W. W. Ke C. H. (2020). Effects of stocking density on the survival and growth of Haliotis discus hannai ♀ × H. fulgens ♂ hybrids. Aquaculture.529, 735693. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735693

13

Gao X. L. Zhang M. Luo X. You W. W. Ke C. H. (2023). Transitions, challenges and trends in China’s abalone culture industry. Rev. Aquac.15, 1274–1293. doi: 10.1111/raq.12769

14

Georgiou-Siafis S. K. Tsiftsoglou A. S. (2023). The key role of GSH in keeping the redox balance in mammalian cells: mechanisms and significance of GSH in detoxification via formation of conjugates. Antioxidants.12, 1953. doi: 10.3390/antiox12111953

15

Goicoechea L. Torres S. Fàbrega L. Barrios M. Núñez S. Casas J. et al . (2024). S-Adenosyl-l-methionine restores brain mitochondrial membrane fluidity and GSH content improving Niemann-Pick type C disease. Redox Biol.72, 103150. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2024.103150

16

Guan G. Q. Chen Y. X. Dong Y. L. (2025). Unraveling the AMPK-SIRT1-FOXO pathway: The in-depth analysis and breakthrough prospects of oxidative stress-induced diseases. Antioxidants.14, 70. doi: 10.3390/antiox14010070

17

Guillard R. R. L. Hargraves P. E. (1993). Stichochrysis immobilis is a diatom, not a chyrsophyte. Phycologia.32, 234–236. doi: 10.2216/i0031-8884-32-3-234.1

18

Hanai T. Shiraki M. Imai K. Suetugu A. Takai K. Shimizu M. (2020). Usefulness of carnitine supplementation for the complications of liver cirrhosis. Nutrients.12, 1915. doi: 10.3390/nu12071915

19

Harris J. O. Maguire G. B. Handlinger J. H. (1998). Effects of chronic exposure of greenlip abalone, Haliotis laevigata Donovan, to high ammonia, nitrite, and low dissolved oxygen concentrations on gill and kidney structure. J. Shellfish Res.17, 683–687. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(97)00249-4

20

He L. Q. Ding Y. Q. Zhou X. H. Li T. J. Yin Y. L. (2023). Serine signaling governs metabolic homeostasis and health. Trends Endocrinol. Metab.34, 361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2023.03.001

21

Hooper C. Day R. Slocombe R. Benkendorff K. Handlinger J. Goulias J. (2014). Effects of severe heat stress on immune function, biochemistry and histopathology in farmed Australian abalone (hybrid Haliotis laevigata×Haliotis rubra). Aquaculture.432, 26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.03.032

22

Huang Y. Jin J. Ren N. X. Chen H. X. Qiao Y. Zou S. M. et al . (2025). ZNF37A downregulation promotes TNFRSF6B expression and leads to therapeutic resistance to concurrent chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer patients. Transl. Oncol.51, 102203. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2024.102203

23

Huang D. Y. Maulu S. Ren M. C. Liang H. L. Ge X. P. Ji K. et al . (2021). Dietary lysine levels improved antioxidant capacity and immunity via the TOR and p38 MAPK signaling pathways in grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idellus fry. Front. Immunol.12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.635015

24

Kenny T. C. Scharenberg S. Abu-Remaileh M. Birsoy K. (2025). Cellular and organismal function of choline metabolism. Nat. Metab.7, 35–52. doi: 10.1038/s42255-024-01203-8

25

Li J. J. Sun C. X. Cai W. W. Li J. Rosen B. P. Chen J. (2021). Insights into S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase related diseases and genetic polymorphisms. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res.788, 108396. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2021.108396

26

Li X. D. Yan T. Yu R. C. Zhou M. J. (2019). A review of Karenia mikimotoi: Bloom events, physiology, toxicity and toxic mechanism. Harmful Algae.90, 101702. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2019.101702

27

Liang Y. Zhong Y. X. Xi Y. He L. Y. Zhang H. Hu X. et al . (2024). Toxic effects of combined exposure to homoyessotoxin and nitrite on the survival, antioxidative responses, and apoptosis of the abalone Haliotis discus hannai. Ecotox Environ. Safe272, 116058. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116058

28

Liao L. Z. Lin J. N. Ding X. S. Feng S. Yan T. (2024). Karenia mikimotoi induced adverse impacts on abalone Haliotis discus hannai in Fujian coastal areas, China. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. Uk.104, e47. doi: 10.1017/S0025315424000353

29

Lin J. N. Yan T. Zhang Q. C. Wang Y. F. Liu Q. Zhou M. J. (2016). Effects of Karenia mikimotoi blooms on antioxidant enzymes in gastropod abalone, Haliotis discus hannai. Mar. Sci.40, 17–22. doi: 10.11759/hykx20150330001

30

Liu S. S. Fu S. Wang G. D. Cao Y. Li L. L. Li X. M. et al . (2021). Glycerol-3-phosphate biosynthesis regenerates cytosolic NAD+ to alleviate mitochondrial disease. Cell Metab.33, 1974–1987.e1979. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.06.013

31

Liu R. X. Song D. K. Zhang Y. Y. Gong H. X. Jin Y. C. Wang X. S. et al . (2024). L-Cysteine: A promising nutritional supplement for alleviating anxiety disorders. Neuroscience.555, 213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2024.07.038

32

Liu C. Y. Yang L. Jin F. Q. Yin Y. L. Xie Z. Z. Yang L. F. et al . (2023). Untargeted UHPLC-MS metabolomics reveals the metabolic perturbations of Helicoverpa armigera under the stress of novel insect growth regulator ZQ-8. Agronomy.13, 1315. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13051315

33

Londhe S. Kamble N. (2013). Histopathology of cerebro neuronal cells in freshwater snail Bellamya bengalensis: impact on respiratory physiology, by acute poisoning of mercuric and zinc chloride. Toxicol. Environ. Chem.95, 304–317. doi: 10.1080/02772248.2013.771431

34

Lu J. Yao T. Fu S. L. Fan S. G. Ye L. T. (2025). Time- and concentration-dependent metabolic responses reveal adaptation failure in cadmium-exposed Haliotis diversicolor. J. Hazard Mater489, 137578. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.137578

35

Majrashi M. Altukri M. Ramesh S. Govindarajulu M. Schwartz J. Almaghrabi M. et al . (2021). β-hydroxybutyric acid attenuates oxidative stress and improves markers of mitochondrial function in the HT-22 hippocampal cell line. J. Integr. Neurosci.20, 321–329. doi: 10.31083/j.jin2002031

36

Malaguarnera M. Pistone G. Astuto M. Vecchio I. Raffaele R. Lo Giudice E. et al . (2006). Effects of L-acetylcarnitine on cirrhotic patients with hepatic coma: randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dig Dis. Sci.51, 2242–2247. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9187-0

37

Martins C. Alves de Matos A. P. Costa M. H. Costa P. M. (2015). Alterations in juvenile flatfish gill epithelia induced by sediment-bound toxicants: A comparative in situ and ex situ study. Mar Environ Res.112, 122–130. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2015.10.007

38

Matsumura T. Uryu O. Matsuhisa F. Tajiri K. Matsumoto H. Hayakawa Y. (2020). N-acetyl-l-tyrosine is an intrinsic triggering factor of mitohormesis in stressed animals. EMBO Rep.21, e49211. doi: 10.15252/embr.201949211

39

Meusel E. Menanteau-Ledouble S. Naylor M. Kaiser H. El-Matbouli M. (2022). Gonad development in farmed male and female South African abalone, Haliotis midae, fed artificial and natural diets under a range of husbandry conditions. Aquacult Int.30, 1279–1293. doi: 10.1007/s10499-022-00850-6

40

Mistri A. Verma N. Kumari U. Mittal S. Mittal A. K. (2016). Surface ultrastructure of gills in relation to the feeding ecology of an angler catfish Chaca chaca (Siluriformes, Chacidae). Microsc Res. Techniq79, 973–981. doi: 10.1002/jemt.22729

41

Moreno-Sánchez R. Marín-Hernández Á. Gallardo-Pérez J. C. Vázquez C. Rodríguez-Enríquez S. Saavedra E. (2018). Control of the NADPH supply and GSH recycling for oxidative stress management in hepatoma and liver mitochondria. BBA-Bioenergetics.1859, 1138–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.07.008

42

Nam S. E. Haque M. N. Lee J. S. Park H. S. Rhee J. S. (2020). Prolonged exposure to hypoxia inhibits the growth of Pacific abalone by modulating innate immunity and oxidative status. Aquat Toxicol.227, 105596. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2020.105596

43

O’Boyle S. McDermott G. Silke J. Cusack C. (2016). Potential impact of an exceptional bloom of Karenia mikimotoi on dissolved oxygen levels in waters off Western Ireland. Harmful Algae.53, 77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2015.11.014

44

Olin-Sandoval V. Yu J. S. L. Miller-Fleming L. Alam M. T. Kamrad S. Correia-Melo C. et al . (2019). Lysine harvesting is an antioxidant strategy and triggers underground polyamine metabolism. Nature.572, 249–253. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1442-6

45

Phégnon L. Pérochon J. Uttenweiler-Joseph S. Cahoreau E. Millard P. Létisse F. (2024). 6-Phosphogluconolactonase is critical for the efficient functioning of the pentose phosphate pathway. FEBS J.291, 4459–4472. doi: 10.1111/febs.17221

46

Possik E. Al-Mass A. Peyot M. L. Ahmad R. Al-Mulla F. Madiraju S. R. M. et al . (2021). New mammalian glycerol-3-phosphate phosphatase: role in β-cell, liver and adipocyte metabolism. Front. Endocrinol.12. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.706607

47

Quinville B. M. Deschenes N. M. Ryckman A. E. Walia J. S. (2021). A comprehensive review: Sphingolipid metabolism and implications of disruption in sphingolipid homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 5793. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115793

48

Riera-Ferrer E. Del Pozo R. Muñoz-Berruezo U. Palenzuela O. Sitjà-Bobadilla A. Estensoro I. et al . (2024). Mucosal affairs: glycosylation and expression changes of gill goblet cells and mucins in a fish-polyopisthocotylidan interaction. Front. Vet. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1347707

49

Sandamalika W. M. G. Priyathilaka T. T. Lee S. Yang H. Lee J. (2019). Immune and xenobiotic responses of glutathione S-Transferase theta (GST-θ) from marine invertebrate disk abalone (Haliotis discus discus): With molecular characterization and functional analysis. Fish Shellfish Immun.91, 159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.04.004

50

Sepand M. R. Razavi-Azarkhiavi K. Omidi A. Zirak M. R. Sabzevari S. Kazemi A. R. et al . (2016). Effect of acetyl-L-carnitine on antioxidant status, lipid peroxidation, and oxidative damage of arsenic in rat. Biol. Trace Elem Res.171, 107–115. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0436-y

51

Sharma A. Anand S. K. Singh N. Dwivedi U. N. Kakkar P. (2023). AMP-activated protein kinase: An energy sensor and survival mechanism in the reinstatement of metabolic homeostasis. Exp. Cell Res.428, 113614. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2023.113614

52

Shen Y. W. Huang M. Q. You W. W. Luo X. Ke C. H. (2020). The survival and respiration response of two abalones under short-term hypoxia challenges. Aquaculture.529, 735658. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735658

53

Shen Y. W. Zhang Y. Xiao Q. Z. Gan Y. Wang Y. Pang G. W. et al . (2021). Distinct metabolic shifts occur during the transition between normoxia and hypoxia in the hybrid and its maternal abalone. Sci. Total Environ.794, 148698. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148698

54

Shimazu T. Hirschey M. D. Newman J. He W. Shirakawa K. Le Moan N. et al . (2013). Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science.339, 211–214. doi: 10.1126/science.1227166

55

Surai P. F. Earle-Payne K. Kidd M. T. (2021). Taurine as a natural antioxidant: From direct antioxidant effects to protective action in various toxicological models. Antioxidants.10, 1876. doi: 10.3390/antiox10121876

56

Tavares L. P. Negreiros-Lima G. L. Lima K. M. E Silva P. M. R. Pinho V. Teixeira M. M. et al . (2020). Blame the signaling: Role of cAMP for the resolution of inflammation. Pharmacol. Res.159, 105030. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105030

57

Venter L. Alfaro A. C. Van Nguyen T. Lindeque J. Z. (2022). Metabolite profiling of abalone (Haliotis iris) energy metabolism: a Chatham Islands case study. Metabolomics.18, 52. doi: 10.1007/s11306-022-01907-6

58

Venter L. Loots D. Mienie L. J. van Rensburg P. J. J. Mason S. Vosloo A. et al . (2018a). The cross-tissue metabolic response of abalone (Haliotis midae) to functional hypoxia. Biol. Open7, bio031070. doi: 10.1242/bio.031070

59

Venter L. Loots D. Mienie L. J. van Rensburg P. J. J. Mason S. Vosloo A. et al . (2018b). Uncovering the metabolic response of abalone (Haliotis midae) to environmental hypoxia through metabolomics. Metabolomics.14, 49. doi: 10.1007/s11306-018-1346-8

60

Wahlang B. McClain C. Barve S. Gobejishvili L. (2018). Role of cAMP and phosphodiesterase signaling in liver health and disease. Cell Signal.49, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.06.005

61

Wang Y. T. Trzeciak A. J. Rojas W. S. Saavedra P. Chen Y. T. Chirayil R. et al . (2023). Metabolic adaptation supports enhanced macrophage efferocytosis in limited-oxygen environments. Cell Metab.35, 316–331.e316. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.12.005

62

Want E. J. Masson P. Michopoulos F. Wilson I. D. Theodoridis G. Plumb R. S. et al . (2013). Global metabolic profiling of animal and human tissues via UPLC-MS. Nat. Protoc.8, 17–32. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.135

63

Wei D. J. Xu S. Y. Wang X. F. Wu W. L. Liu Z. Wu X. D. et al . (2025). Photoinduced electron transfer enables cytochrome P450 enzyme-catalyzed reaction cycling. Plant Physiol. Biochem.219, 109412. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.109412

64

Wen B. Mei Z. L. Zeng C. W. Liu S. Q. (2017). metaX: a flexible and comprehensive software for processing metabolomics data. BMC Bioinf.18, 183. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1579-y

65

Wu Y. M. Huang S. Z. Zhao H. X. Cao K. Gan J. F. Yang C. et al . (2021). Zebrafish minichromosome maintenance protein 5 gene regulates the development and migration of facial motor neurons via fibroblast growth factor signaling. Dev. Neurosci.43, 84–94. doi: 10.1159/000514852

66

Xiao W. S. Loscalzo J. (2020). Metabolic responses to reductive stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal.32, 1330–1347. doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7803

67

Xie E. Y. (2016). Investigating the mechanisms of Karenia mikimotoi-induced mortality in Haliotis diversicolor. ( Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, China).

68

Xu F. Gao T. T. Liu X. (2020). Metabolomics adaptation of juvenile Pacific abalone to heat stress. Sci. Rep.10, 6353. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63122-4

69

Xu P. Zheng Y. D. Zhu X. X. Li S. Y. Zhou C. L. (2018). L-lysine and L-arginine inhibit the oxidation of lipids and proteins of emulsion sausage by chelating iron ion and scavenging radical. Asian Austral J. Anim.31, 905–913. doi: 10.5713/ajas.17.0617

70

Yang B. Gao X. L. Zhao J. M. Liu Y. L. Xie L. Lv X. Q. et al . (2021). Potential linkage between sedimentary oxygen consumption and benthic flux of biogenic elements in a coastal scallop farming area, North Yellow Sea. Chemosphere.273, 129641. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129641

71

Yu F. Shen Y. W. Peng W. Z. Chen N. Gan Y. Xiao Q. Z. et al . (2023a). Metabolic and transcriptional responses demonstrating enhanced thermal tolerance in domesticated abalone. Sci. Total Environ.872, 162060. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162060

72

Yu Z. M. Tang Y. Z. Gobler C. J. (2023b). Harmful algal blooms in China: History, recent expansion, current status, and future prospects. Harmful Algae129, 102499. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2023.102499

73

Zhang L. Chen Y. Zhou Z. Y. Wang Z. Y. Fu L. Zhang L. J. et al . (2023a). Vitamin C injection improves antioxidant stress capacity through regulating blood metabolism in post-transit yak. Sci. Rep.13, 12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-36779-w

74

Zhang M. Gao X. L. Lyu M. X. Lin S. H. Luo X. You W. W. et al . (2022). AMPK regulates behavior and physiological plasticity of Haliotis discus hannai under different spectral compositions. Ecotox Environ. Safe.242, 113873. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113873

75

Zhang Y. Song X. X. Zhang P. P. (2023b). Combined effects of toxic Karenia mikimotoi and hypoxia on the juvenile abalone Haliotis discus hannai. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1029512

76

Zhang T. F. Yan T. Zhang Q. C. Li X. D. Zhou M. J. (2018). Acute effect of four typical bloom forming algae on abalone Haliotis discus hannai and its antioxidant enzymes system. Mar. Environ. Science.37, 207–214. doi: 10.13634/j.cnki.mes.2018.02.008

77

Zhao Z. Gan H. L. Lin X. Wang L. Y. Yao Y. Y. Li L. et al . (2023). Genome-wide association screening and MassARRAY for detection of high-temperature resistance-related SNPs and genes in a hybrid abalone (Haliotis discus hannai ♀ x H. fulgens ♂) based on super genotyping-by-sequencing. Aquaculture.573, 739576. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.739576

78

Zhou M. C. Zhang J. P. Huang M. Q. You W. W. Luo X. Han Z. F. et al . (2024). Genetic variation between a hybrid abalone and its parents (Haliotis discus hannai ♀ and H. fulgens ♂) based on 5S rDNA gene and genomic resequencing. Aquaculture.579, 740173. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.740173

79

Zhou J. Zhu X. S. Cai Z. H. (2010). Tributyltin toxicity in abalone (Haliotis diversicolor supertexta) assessed by antioxidant enzyme activity, metabolic response, and histopathology. J. Hazard Mater.183, 428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.07.042

Summary

Keywords

hybrid abalone, Karenia mikimotoi blooms, histopathology, oxidative stress indicators, metabolomics

Citation

Liao H, Xu X, Zhuang Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Zhang Q, Ding Z, Wu Y, Zhang P and Yang J (2025) Pathological and metabolic effects of a simulated Karenia mikimotoi bloom on hybrid abalone (Haliotis discus hannai♀ × H. fulgens♂). Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1702024. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1702024

Received

09 September 2025

Revised

14 November 2025

Accepted

17 November 2025

Published

04 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Zekun Huang, Xiamen University, China

Reviewed by

Dayong Liang, Guangzhou University, China

Hailong Huang, Ningbo University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Liao, Xu, Zhuang, Zhang, Li, Zhang, Ding, Wu, Zhang and Yang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xin Xu, xuxin@mju.edu.cn; Jie Yang, jie.yang@mju.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.