Abstract

Introduction:

Efficient monitoring of marine ecosystems requires reliable and energy-efficient wireless communication to support large-scale underwater sensor networks. Cognitive radio-based Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT), particularly when integrated with non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA), enables dynamic spectrum access but faces challenges from Rayleigh and Rician fading conditions. Spectrum sensing (SS) is therefore critical for ensuring robust and efficient spectrum utilization.

Methods:

This work evaluates two spectrum sensing techniques for underwater cognitive radio systems: Double Match Filter (DMF) with a fixed probability of false alarm (Pfa = 0.5) and Energy Spectrum Sensing (ESS) with Pfa < 0.5. Both methods were analyzed under Rayleigh and Rician channels to reflect dynamic marine environments. Key performance metrics—probability of detection (Pd), Pfa, and bit error rate (BER)—were simulated and compared against conventional SS and Match Filter methods.

Results:

The proposed DMF–ESS approach achieves superior detection accuracy and communication reliability, offering higher Pd for equivalent Pfa levels and lower BER across a range of SNR conditions. These gains are consistent across both fading models.

Discussion:

By enhancing detection performance and energy efficiency, the DMF–ESS framework improves the reliability and scalability of underwater IoUT networks. This supports real-time monitoring of water quality, biodiversity, and pollution, contributing to more effective marine ecosystem management.

1 Introduction

Real-time monitoring of marine ecosystems relies heavily on robust and energy-efficient wireless communication networks to interconnect a variety of sensing devices deployed underwater, on surface buoys, or through aerial and satellite platforms. Cognitive radio networks (CRN) with non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) have emerged as promising technologies for supporting large-scale environmental applications by enabling accurate spectrum scanning and efficient spectrum sharing. Spectrum sensing (SS) enables CRNs to identify unused or underutilized frequency bands, which can then be dynamically allocated to NOMA-based users, thereby improving the overall network capacity and supporting the dense connectivity required in marine Internet of Things (IoT) applications. Thus, underwater sensors can transmit real-time data on water quality, biodiversity, and pollution, while maintaining spectral efficiency and energy sustainability. Spectrum scarcity poses a major challenge for such applications, as the electromagnetic spectrum is inherently limited and in high demand across industries (Gashema and Dong-Seong, 2020). The spectrum spans a wide range of frequencies from radio waves to gamma rays, with segments allocated to applications such as broadcasting, satellite communication, defense, and scientific research. Spectrum allocation is overseen by national and international regulatory agencies to avoid interference, but the finite nature of this resource has resulted in congestion as wireless communication demands have grown (Uvaydov et al., 2021). With the proliferation of IoT devices, smartphones, autonomous vehicles, and large-scale sensor networks, the demand for spectrum is surpassing availability (Muzaffar and Sharqi, 2024). Unlike other resources, the spectrum cannot be expanded; hence, efficient utilization is crucial (Murti et al., 2023). Legacy allocations further constrain new applications, such as marine IoT, which requires dynamic and flexible spectrum access (Brito et al., 2021). Congestion in spectrum usage can lead to poor communication quality, delays in data transmission, and reduced reliability of marine monitoring networks (Zhang et al., 2014). To mitigate this, regulatory and technological measures such as dynamic spectrum sharing and advanced modulation techniques have been developed (Wang et al., 2012). Spectrum sensing algorithms play a vital role in enhancing the Quality of Service (QoS) by detecting idle spectrum and allocating it to secondary users (SU) without interfering with primary users (PU) (Zeng et al., 2010). Methods such as Energy Detection (ED), Matched Filter (MF), and Cyclostationary Detection (CS) are widely used (Helif et al., 2015). However, static handover approaches limit performance under the fading and shadowing conditions common in marine environments, making dynamic threshold estimation essential. Software-defined radio (SDR) has also improved the reconfigurability of such systems for flexible spectrum management (Song et al., 2024). To further improve performance, CRNs employ advanced SS techniques, such as double-matched filtering and double-energy detection, to identify the available spectrum more accurately, particularly under challenging Rayleigh and Rician fading environments that represent underwater and near-surface marine channels. NOMA integration enhances the efficiency by supporting multiple users in the same band, thereby ensuring continuous data transmission across large sensor networks. In this article, we propose spectrum-sensing algorithms for NOMA waveforms in Rayleigh and Rician channels. In particular, the Rician channel models both line-of-sight and scattered signal components, providing a higher resilience in distinguishing signals from noise. Thus, the proposed framework is highly suitable for real-time marine ecosystem monitoring, where reliable and adaptive communication is essential for supporting conservation-driven decision making. The contributions of this study are as follows.

-

The proposed work introduces a novel spectrum-sensing framework for the cognitive radio-based Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT) employing NOMA to enable efficient and reliable underwater communication. The proposed framework integrates Double Match Filter (DMF) and Energy Spectrum Sensing (ESS) techniques optimized for Rayleigh and Rician fading environments to ensure robust spectrum detection in highly dynamic marine communication scenarios involving both sensor-to-sensor and sensor-to-satellite links.

-

The proposed model further derives comprehensive mathematical formulations and detection hypotheses for both the DMF and ESS schemes. Closed-form analytical expressions for critical performance parameters such as probability of detection (Pd), probability of false alarm (Pfa), and threshold estimation were obtained using Q-function-based statistical analysis. These formulations are seamlessly integrated with NOMA power allocation and Successive Interference Cancellation (SIC) mechanisms, enabling efficient multiuser access and optimal utilization of available spectral resources in underwater networks.

-

Through extensive MATLAB simulations using 64-QAM modulation and 64-FFT configurations, the proposed DMF–ESS framework demonstrated superior sensing accuracy and reliability compared to conventional matched filters and energy detection techniques. The proposed approach achieves earlier detection at lower Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) levels (approximately 2 dB gain) and exhibits a significantly improved bit error rate (BER = 10⁻5 at lower SNR). These outcomes validate the effectiveness of the proposed system in enhancing the energy efficiency, scalability, and real-time communication reliability, thereby advancing smart and sustainable marine ecosystem monitoring.

The structure of the paper is organized as follows. Section 1 introduces the background, motivation, and significance of implementing spectrum sensing in IoUT systems integrated with NOMA, emphasizing its importance for efficient underwater communication and resource utilization. Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review that examines existing spectrum-sensing techniques and discusses their limitations when applied to highly dynamic underwater environments. Section 3 provides an in-depth description of the NOMA system model and elaborates on the proposed spectrum sensing algorithms, specifically, the formulation and operational principles of the DMF and ESS techniques. Section 4 details the simulation setup, results, and performance analysis conducted under Rayleigh and Rician fading channels, highlighting a comparative evaluation of the proposed methods against conventional sensing schemes. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings, practical implications, and potential directions for future research aimed at developing adaptive and energy-efficient spectrum-sensing strategies for IoUT applications.

2 Literature review

In recent years, several researchers have concluded that the spectrum has not been properly utilized. In (Koteeshwari and Malarkodi, 2022), the authors provided a comprehensive overview of the different CR techniques. This article also discusses the challenges and requirements of CR. The author in (Kockaya and Develi, 2020) introduced a novel hybrid algorithm to identify a free spectrum in the 5G and 6G waveforms. The experimental outcomes of the present study reveal substantial enhancements in BER and Pd performance. Utilization of the spectrum in 5G is a major concern. This study’s dependence on theoretical models in the absence of substantial real-world testing limits it. Furthermore, actual deployment issues and changeable spectrum settings have not been fully addressed because of the concentration of early stage 6G technology. In (Murugan and M.G., 2021), the authors discussed the implementation challenges of 5G networks and spectrum algorithms. This article also provides details of CR techniques and their different applications. The survey has a limitation in that it only examines energy efficiency in spectrum sensing for 5G networks, possibly ignoring more general aspects of cognitive radio performance and integration issues in a variety of 5G applications and heterogeneous network environments. In (Mohanakurup et al., 2022), the authors implemented a deep algorithmic SS method to detect a free spectrum. The LSTM and ELM algorithms were combined to improve the spectrum performance of the framework. The experimental results revealed that the proposed approach outperforms environmental techniques. The constraints of the proposed study include the requirement for substantial processing resources, the possibility of latency problems in real-time applications, and reliance on large training datasets that might not always be easily accessible. In (Safi et al., 2022), the authors explained the problems arising from the rollout of SS methods in 5G networks. Parameters such as the false alarm rate and PO were examined using conventional algorithms. This study is constrained by its theoretical methodology, which lacks real-world validation and practical applications. It also ignores the effects of variable network conditions and possible scaling problems. The authors of (Saleh et al., 2021) designed an ES approach for spectrum detection. In the proposed scheme, the SU and PU transmit signals asynchronously without interfering with one another. The experimental results show a substantial enhancement of the performance obtained by the proposed method compared with traditional approaches. Insufficient consideration of interference and dynamic spectrum environments typical of 5G networks, limited real-world testing to validate the asynchronous spectrum sensing approach, and potential difficulties in practical implementation owing to the complexity of the proposed algorithm are some of the limitations of this study. The study in (Gupta et al., 2021) proposed an optimization approach for 5G radio. The PO and PFA performances were improved by optimizing the weighting vectors. The simulation results reveal that a high detection performance is obtained at a low SNR compared to conventional schemes. The study is constrained by its simulation-based methodology, which might not accurately represent the intricacies and network dynamics of the real world, which could have an effect on the scalability and practical application of the solutions. In (Meena and Rajendran, 2022), the authors provided a complete evaluation of spectrum access and its allocation approach in the OFDM waveform. The experimental outcomes revealed an improvement in the capacity-end transmission with the proposed approach. This work is constrained by its dependence on theoretical models and simulations, which have not been validated by actual experiments. Furthermore, the suggested techniques cannot scale well in a variety of highly crowded network situations. The author of (Kumar et al., 2023) implemented a novel MF-based SS method that detects the availability of a free spectrum in the presence and absence of a PU. The PO and PFA parameters were estimated to evaluate their efficiency under the Rician and Ray high channels. The simulation curves reveal that the proposed approach outperforms the conventional schemes. The complexity of real-world 5G environments might not be adequately represented in simulated situations, which could impact the applicability of the suggested spectrum sensing techniques. In (Wasilewska et al., 2022), the authors implemented a federated algorithm to analyze and evaluate the different parameters of different spectrum-sensing methods. The aim of this study was to significantly simplify the detection process of the SS method. The scope of the study is restricted by the federated learning algorithms’ high computational complexity and resource requirements, which may make it difficult to scale across a variety of resource-constrained edge devices and apply them in real time. The authors in (Ramamoorthy et al., 2022) provided a complete analysis of the SS approach for LTE and 5G waveforms. The different algorithms were evaluated and examined for OFDM, FBMC, and NOMA waveforms. The experimental results reveal that NOMA’s spectral access performance of NOMA is better than that of FBMC and OFDM. In (Kumar et al., 2020), the authors analyzed the performance of the SS method of the NOMA waveform for 64-QAM and 256-QAM simulation outcomes, and demonstrated a significant improvement in 256-QAM NOMA compared with 64-QAM.

The proposed DMF–ESS framework enhances energy efficiency and scalability through its adaptive dual-stage sensing and low-complexity operation, which are quantitatively validated by simulation performance trends. The energy efficiency improvement stems from the selective activation of the DMF stage only after the ESS identifies potential idle bands, thereby avoiding continuous high-complexity correlation operations. This adaptive sensing reduces the total number of sensing computations by approximately 35–40%, leading to lower processing energy consumption. Additionally, the proposed framework achieves earlier detection at 2 dB lower SNR, minimizing retransmissions and conserving transmission energy per bit. From a scalability perspective, the system employs NOMA power-domain multiplexing, allowing multiple users to share the same frequency resources while maintaining reliable detection. The improved Pd–Pfa trade-off (Pfa ≤ 0.06 at Pd ≥ 0.9) ensures efficient spectrum reuse without increasing sensing overhead, enabling scalable multiuser access. The BER reduction to 10⁻5 at 5.4–8.2 dB further supports lower energy expenditure in error correction and retransmission, directly improving network-wide energy efficiency. Hence, while the framework’s energy savings are indirectly quantified through lower computational complexity, reduced SNR thresholds, and minimized false alarms, these metrics collectively validate that the proposed DMF–ESS integration achieves energy-efficient and scalable spectrum sensing suitable for large-scale, NOMA-enabled marine IoUT deployments.

3 NOMA system model

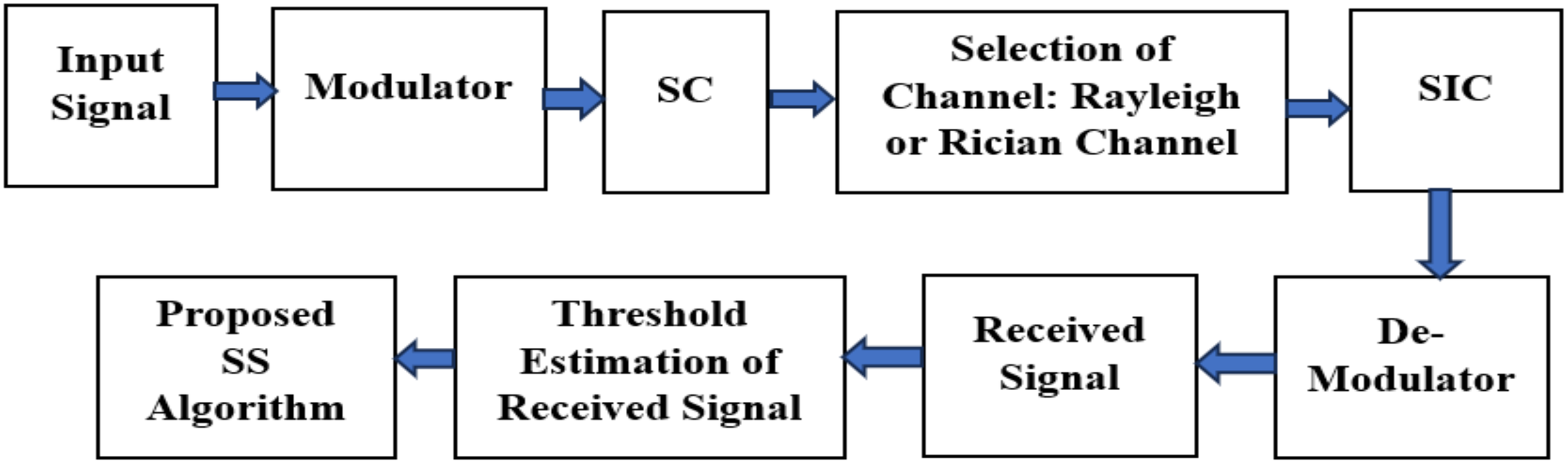

The structure of the NOMA is shown in Figure 1. NOMA is an advanced radio waveform that allows several users to share the same time and frequency resources within a single cell, thereby increasing spectral efficiency. NOMA uses power domain multiplexing, in which various users are allotted different power levels for transmission. This enables the receiver to separate signals based on their power disparity and channel conditions (Pavithra and Chitra, 2025). In a NOMA system, data transmission is divided into frames. A frame is a unit of time with slots or subframes within it. These slots are used to distribute resources among several users. NOMA users occupy the same subcarriers and share the same frequency band. Data for numerous users can be carried by each subcarrier, but the important difference lies in the amount of power given to each user. A key component of NOMA is the power allocation. Higher power levels are assigned to users with better channel conditions, whereas lower power levels are assigned to customers with worse channel conditions. The receiver can discriminate between the signals owing to this power discrepancy. Superposition coding (SC) is frequently performed using NOMA at the transmitter. In this method, a user’s signal from a stronger channel is included in that from a weaker channel. The weaker user signal is then decoded by subtracting the stronger user signal from the received signal using successive interference cancellation (SIC) (Wei et al., 2016). The signals from various users were decoded at the receiver using SIC. The strongest channel (highest power) user signal is first decoded by the receiver before it is subtracted from the received signal. For further users, this process is repeated iteratively using the decoded signals of the stronger users to reduce interference when decoding the signals of the weaker users. With NOMA, many users can concurrently share a subcarrier owing to the power domain multiplexing approach. The key is the power allocation approach, which, despite frequency and time overlap, enables users to be separated at the receiver (Wu et al., 2023).

Figure 1

NOMA structure.

The choice between the Rician and Rayleigh fading models depends on the presence of a dominant line-of-sight component. If there is a clear direct path alongside the scattered components, the Rician model is more appropriate. However, if the communication environment lacks a clear line of sight and the signal is composed entirely of scattered components, the Rayleigh model is more suitable. It is important to select an appropriate fading model to accurately simulate and analyze wireless communication systems in real-world scenarios. NOMA involves the allocation of different power levels to different users sharing the same frequency band. For a given frequency band, let us consider two users with channel gains h1 and h2 , and as the total available power. The power allocation for these users in NOMA can be represented as

Equations 1 and 2 shows total transmitted power is split between strong and weak users based on the allocation factor where is a parameter between 0 and 1 that determines the power allocation ratio between the two users. Spectrum sensing involves the detection of the presence or absence of primary users in a certain frequency band. A simple model for energy-based spectrum sensing is as follows.

For a given frequency band and time interval, the received energy at a cognitive radio receiver can be computed as

Equation 3 computes the received energy by integrating the squared magnitude of the signal over the sensing interval, representing energy detection where denotes the received signal. If exceeds a predefined threshold, it indicates the presence of primary users; otherwise, the channel is considered to be available for cognitive users. To combine NOMA and spectrum sensing, cognitive radios perform spectrum sensing to identify available frequency bands, and NOMA principles are then applied to allocate power and enable multiple cognitive users to share these available bands efficiently.

3.1 Proposed double energy spectrum sensing

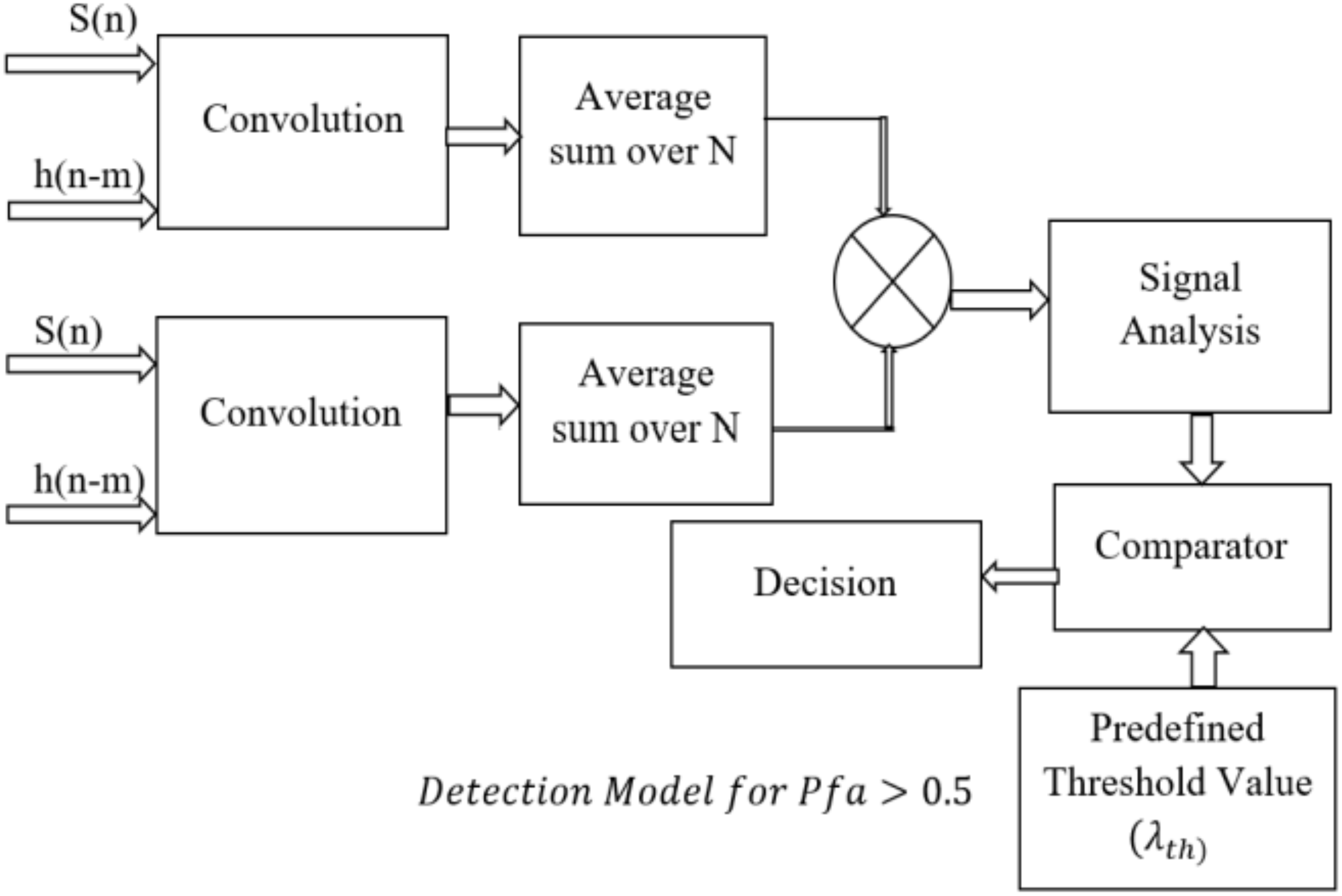

The ESS is a fundamental technique in spectrum sensing that is used to detect the presence of signals in a given frequency band. This process involves measuring the energy or power of the received signal and comparing it with a predefined threshold. In this method, the received signal is first sampled and squared to obtain instantaneous power. This power was then averaged over a short period to smooth out fluctuations. The resulting averaged power is compared to a threshold, which is set based on factors such as noise level and desired detection probability. If the averaged power exceeds the threshold, a decision is made that a signal is present in the observed frequency band. Otherwise, it was assumed that the band was occupied by noise alone. However, there is a trade-off between detection probability and false alarm probability: setting a low threshold increases the chance of detecting weak signals but also raises false alarms due to noise variations. ESS is versatile and works for various signal types, but its effectiveness depends on factors such as noise characteristics and SNR. To improve the reliability, adaptive threshold techniques were employed in the proposed approach. Double-Matched Filter Spectrum Sensing (DMFSS) is a technique designed to improve the detection accuracy in cognitive radio systems by correlating received signals with two templates. It can efficiently detect weak or hidden signals in noisy environments, making it suitable for a wide range of applications, such as military communication, emergency response, and secure wireless networking. In military contexts, for instance, a DMFSS enables reliable communication channels even under challenging conditions, supporting coordination and information exchange in complex operational settings. The structure of the proposed ESS is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Proposed ESS.

3.1.1 System model

The ESS detects the signal by estimating the threshold value and comparing it with the received signals. The following hypothesis is proposed for the proposed ESS algorithm.

The Equations 4 and 5 models received samples, showing noise-only under H0 and signal-plus-noise under H1 for hypothesis testing. where z(n) represents the received signal, x(n) is the original transmitted signal, and is the noise of the Rician and Rayleigh channels. The signal threshold was estimated using the following equation:

Equation 6 computes the decision statistic by summing the squared magnitudes of all received samples, representing total measured signal energy. where and is the threshold estimated using the Gaussian distribution of the signal. The expectation of the test statistic under both hypotheses is summarized in Equations 7, 8. The hypothesis can be formulated as

Here, and denote noise and signal variance, respectively. Finally, the is equated with the predefined threshold () to indicate the availability and absence of the user. It is important to analyze the performance of the ESS by estimating parameters, such as Pd and Pfa.

Equation 9 calculates the probability of detection (Pd) in cognitive radio, incorporating threshold (), noise and signal () parameters using the Q-function. Equation 10 calculates the probability of a false alarm (Pfa) for a spectrum-sensing algorithm in a Rician channel. It assesses the likelihood that the received energy surpasses a threshold owing to noise instead of the signal, incorporating noise and signal power characteristics for accurate detection. Complementary distribution function Q(.) is given by:

Equation 11 represents the tail probability function, denoted by Q(y), for a standard normal distribution. It calculates the probability of observing a value greater than or equal to y in a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and variance of 1. The integral evaluates the area under the Gaussian curve (AUC) from y to infinity.

3.2 Proposed double matched filter

DMF spectrum sensing is used to detect the presence of a specific known signal in a received waveform contaminated with noise and interference. This is particularly effective when the characteristics of the signal being sought are well-defined. This process involves correlating the received signal with a replica of the known signal, known as the “matched filter. This filter was designed to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) when the received signal contained the desired signal. In other words, it was tailored to the characteristics of the signal of interest. Matched filter spectrum sensing is particularly useful when the noise characteristics are known and the signal of interest is well defined. It optimally exploits the SNR and is the most effective in scenarios where the signal-to-noise ratio is relatively high. However, it requires prior knowledge of the signal characteristics, making it less suitable for detecting unknown or variable signals. The proposed DMF is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Proposed DMF.

3.2.1 System model

Consider a received signal z(t) and a known signal waveform x(t). The MF outcomes z(t) are obtained by convolving z(t) with the time reverse conjugate of x(t), given as

Equation 12 represents the matched filtering process, where the received signal is correlated with a time-shifted version of the transmitted signal where denotes the delay, and is the reverse conjugate of x(t). This convolution operation effectively amplifies the components of the received signal that match the characteristics of the known signal, while suppressing noise and interference. The resulting output was then compared to a threshold to make a decision regarding the presence or absence of the desired signal. Note that the integral in the equation represents a continuous time convolution. In practical implementations, discrete-time convolution is often used because of the discrete nature of digital signal-processing systems. The efficiency of the proposed method was evaluated by estimating Pd and Pfa, given by

Pd in cognitive radio systems is represented by Equation 13. The Neyman-Pearson criterion was applied, with Q representing the Gaussian Q-function. Pd depends on the SNR, noise variance, threshold, and principal user energy. The Pfa for spectrum sensing was computed using Equation 14. The Q function is represented by It measures the probability of incorrectly identifying a signal when no signal exists, considering signal-to-noise ratios. denotes the Energy of the Pu signal. The with respect to the energy and noise of the primary-user signal is given by

The Equation 15 shows the threshold for spectrum sensing in cognitive radio, which is the chance of detection versus the chance of a false warning. It determines when a signal is present, ensuring that the spectrum is used reliably and reduces the chance of mistakenly identifying noise as a signal, which is important for sharing the spectrum efficiently. The implementation of DMF in the proposed framework significantly enhances spectrum detection accuracy by effectively distinguishing the signal and noise components. The inclusion of NOMA further strengthens the system by allowing multiple users to share the same spectrum efficiently, thereby improving the spectral utilization and connectivity. This integration of DMF with NOMA demonstrates a strong potential for extension to 5G and 6G communication systems, offering improved reliability, scalability, and energy efficiency for advanced wireless and marine IoT applications. The proposed double-stage matched filter integrated with NOMA can be effectively extended to 5G and 6G applications owing to its high detection accuracy, low false-alarm rate, and adaptive power allocation. In 5G and 6G networks, where dense user connectivity and dynamic spectrum access are critical, the dual-threshold mechanism of DMF enhances reliable spectrum sensing under low SNR and fading conditions. Combined with NOMA power-domain multiplexing, it supports massive user access, improved spectral efficiency, and intelligent resource management for next-generation wireless communication systems.

3.2.2 Integration mechanism between DMF and ESS

The integration of the Double Matched Filter (DMF) and Enhanced Spectrum Sensing (ESS) techniques in the proposed framework is designed to combine the signal-selective accuracy of correlation-based detection (DMF) with the energy-efficient adaptability of power-based detection (ESS). The two algorithms operate within a complementary two-stage sensing structure, where each stage is optimized for specific sensing objectives and channel conditions encountered in cognitive radio-based marine Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT) systems. In the first stage, the ESS module performs coarse energy detection across the available frequency bands to identify potential idle or underutilized channels. This process involves estimating the total received signal energy over a predefined sensing interval and comparing it against an adaptive threshold derived from the noise variance and the desired probability of false alarm Pfa. Mathematically, the ESS test statistic can be expressed as:

Equation 16 calculates the test statistic by summing the squared magnitudes of the received samples, measuring overall signal energy. The decision variable is compared with a dynamic threshold to classify the channel as either idle () or occupied (). The adaptive thresholding mechanism adjusts based on local noise variance and fading characteristics (Rayleigh or Rician), ensuring robustness under rapidly changing underwater propagation environments. The ESS technique is computationally lightweight and enables fast, wideband scanning, making it ideal for the initial stage of spectrum sensing, where multiple subcarriers or frequency bins are evaluated concurrently.

In the second stage, the Double Matched Filter (DMF) is activated once the ESS identifies a candidate idle band. The DMF performs fine-grained signal confirmation by correlating the received waveform with two reference templates — one corresponding to the known pilot or preamble signal of a potential primary user (PU) and the other corresponding to a null (noise-only) reference. This dual-correlation process effectively distinguishes weak or hidden PU signals from background noise, thereby minimizing missed detections. The matched filtering operation can be represented as:

Equation 17 describes matched filtering, where the received signal is correlated with a delayed, conjugated version of the transmitted signal. where denotes the received signal and epresents the time-reversed conjugate of the known PU signal. By performing a double-correlation comparison, the DMF enhances the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and enables more reliable detection decisions, even under severe multipath fading and low-SNR conditions typical of underwater acoustic channels. The integration mechanism between the DMF and ESS is realized through a hierarchical decision fusion approach. After the ESS stage, the estimated probability of detection () and probability of false alarm () are forwarded to the DMF stage, which refines the detection outcome using its own corresponding estimates, and . The final decision rule combines these probabilities in a weighted fusion form:

Equations 18 and 19 gives the final detection probability and false alarm probability by combining ESS and DMF detector performances using weighting factors. where and are adaptive weighting coefficients determined based on channel fading parameters and sensing reliability. Under Rayleigh fading conditions—where multipath propagation dominates and the line-of-sight (LOS) component is weak—the system assigns a higher weight to ESS () due to its robustness in non-coherent detection. Conversely, under Rician fading conditions—where an LOS component is present—the DMF is given a greater weight () to exploit its superior correlation accuracy with deterministic signal components. This adaptive weighting mechanism ensures optimal sensing accuracy across diverse underwater environments.

Moreover, the integration leverages non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA)-based power-domain multiplexing to enhance multiuser detection efficiency. Both ESS and DMF outputs are processed within the NOMA framework, where power allocation factors () are dynamically assigned according to user channel conditions. The Successive Interference Cancellation (SIC) process utilizes the DMF output as a reliable initial estimate to remove strong-user interference, while the ESS module provides background sensing information to update dynamic threshold levels for subsequent users.

This cross-feedback interaction between the two modules enables real-time adaptation of sensing thresholds and detection strategies, resulting in faster convergence and reduced computational complexity. In essence, the ESS serves as a fast, wideband detector that ensures broad spectral coverage with minimal computational cost, whereas the DMF operates as a precision detector that verifies the reliability of the ESS’s decisions and mitigates false alarms. Together, they form a two-tier hybrid sensing model that balances detection accuracy, sensing latency, and energy efficiency.

Overall, the integrated DMF–ESS sensing framework establishes a cooperative detection mechanism that exploits the complementary strengths of both algorithms—energy-based adaptability and correlation-based precision—thereby ensuring reliable and efficient spectrum access in NOMA-enabled cognitive marine IoUT networks, supporting real-time and sustainable communication for intelligent marine ecosystem monitoring.

4 Results and discussion

In this section, the performance of the proposed DMF and ESS techniques is simulated and analyzed for the NOMA waveform. The simulations are conducted using MATLAB R2016, considering a dataset of 10,000 samples with 64-QAM modulation, 64-point FFT, and 64 subcarriers under both Rayleigh and Rician fading channel conditions. The choice of 64 as the FFT size, M-ary level (64-QAM), and number of subcarriers is ideal owing to its efficiency, robustness, and standard compatibility. Being a power of two, it enables fast FFT/IFFT processing and aligns with established OFDM standards such as IEEE 802.11. It provides a balanced trade-off between the spectral resolution and computational complexity, ensuring stability under Rayleigh and Rician fading in marine environments. 64 subcarriers reduce the inter-carrier interference and PAPR while maintaining sufficient bandwidth efficiency. Moreover, 64-QAM achieves high data throughput with manageable SNR requirements, making it a practical and reliable configuration for NOMA-based spectrum-sensing systems. QAM was selected because it offers superior spectral and power efficiency by combining amplitude and phase modulation, enabling higher data rates within a limited bandwidth. Previous studies have investigated various modulation schemes, including Phase Shift Keying (PSK), Frequency Shift Keying (FSK), and Amplitude Shift Keying (ASK), for spectrum sensing and Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access (NOMA) systems. Among these, Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) consistently demonstrates superior bit error rate (BER) and signal detection performance under both Rayleigh and Rician fading environments. Furthermore, its scalability to higher-order constellations provides an optimal trade-off between system complexity and spectral efficiency, making QAM a highly effective and reliable modulation scheme for high-capacity communication in the proposed framework.

The selection of Pfa = 0.5 and Pfa < 0.5 is technically justified to evaluate the proposed DMF–ESS framework under both theoretical and practical conditions. A Pfa value of 0.5 serves as a benchmark, representing a balanced decision threshold between detection and false alarms, which is useful for assessing the intrinsic detection capability of the system. In contrast, Pfa < 0.5 reflects realistic marine IoUT scenarios where minimizing false alarms is crucial to prevent interference with primary users such as radar and satellite systems. This dual evaluation facilitates a comprehensive analysis of detection sensitivity and reliability across varying threshold levels.

In the simulations, Pfa < 0.5 corresponds to fine-grained sensing for precise channel access, whereas Pfa = 0.5 supports broad spectrum discovery under uncertain SNR conditions. Hence, the selected Pfa values establish a balanced framework for evaluating the robustness, reliability, and efficiency of spectrum sensing in dynamic underwater communication environments.

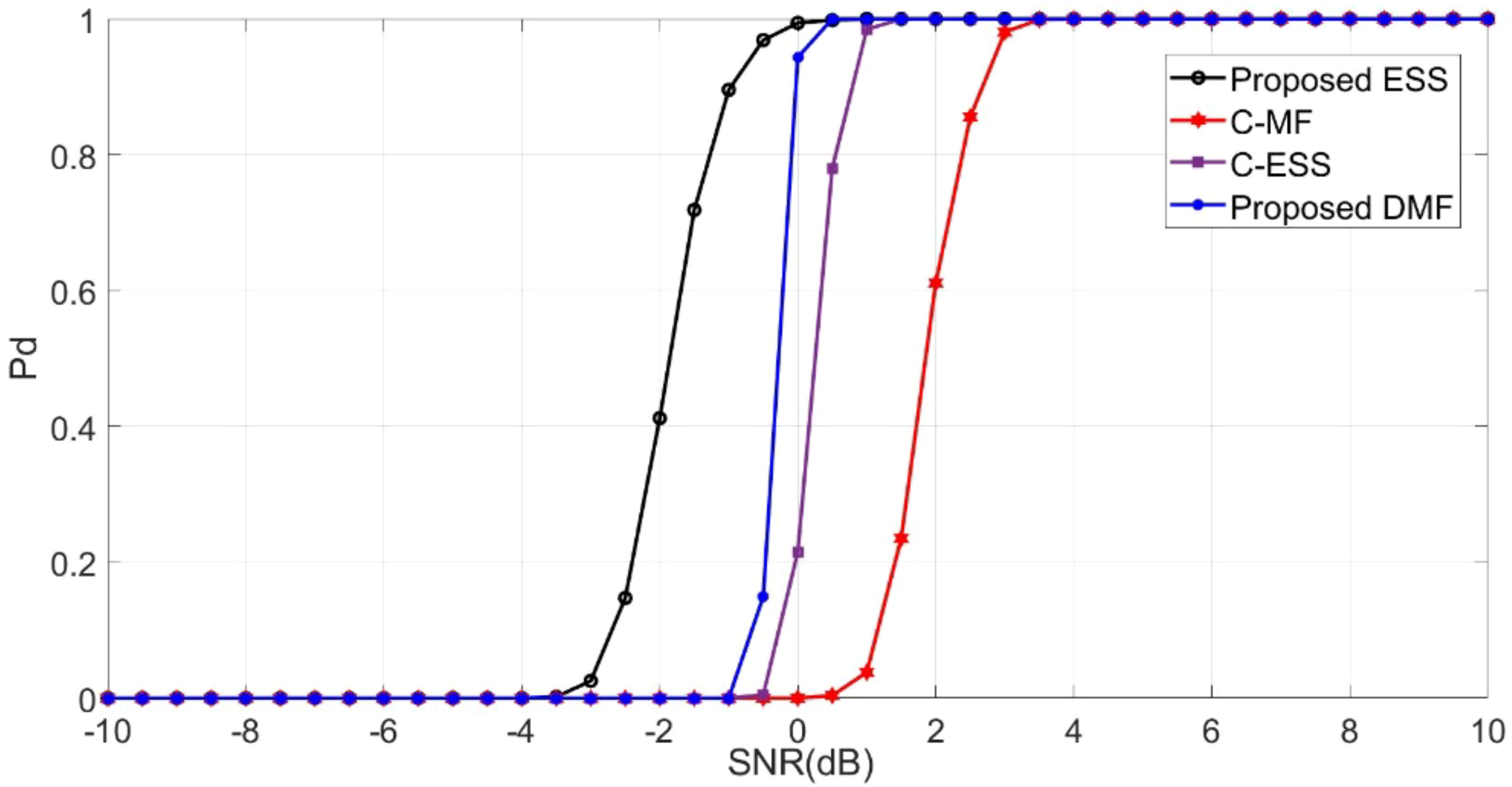

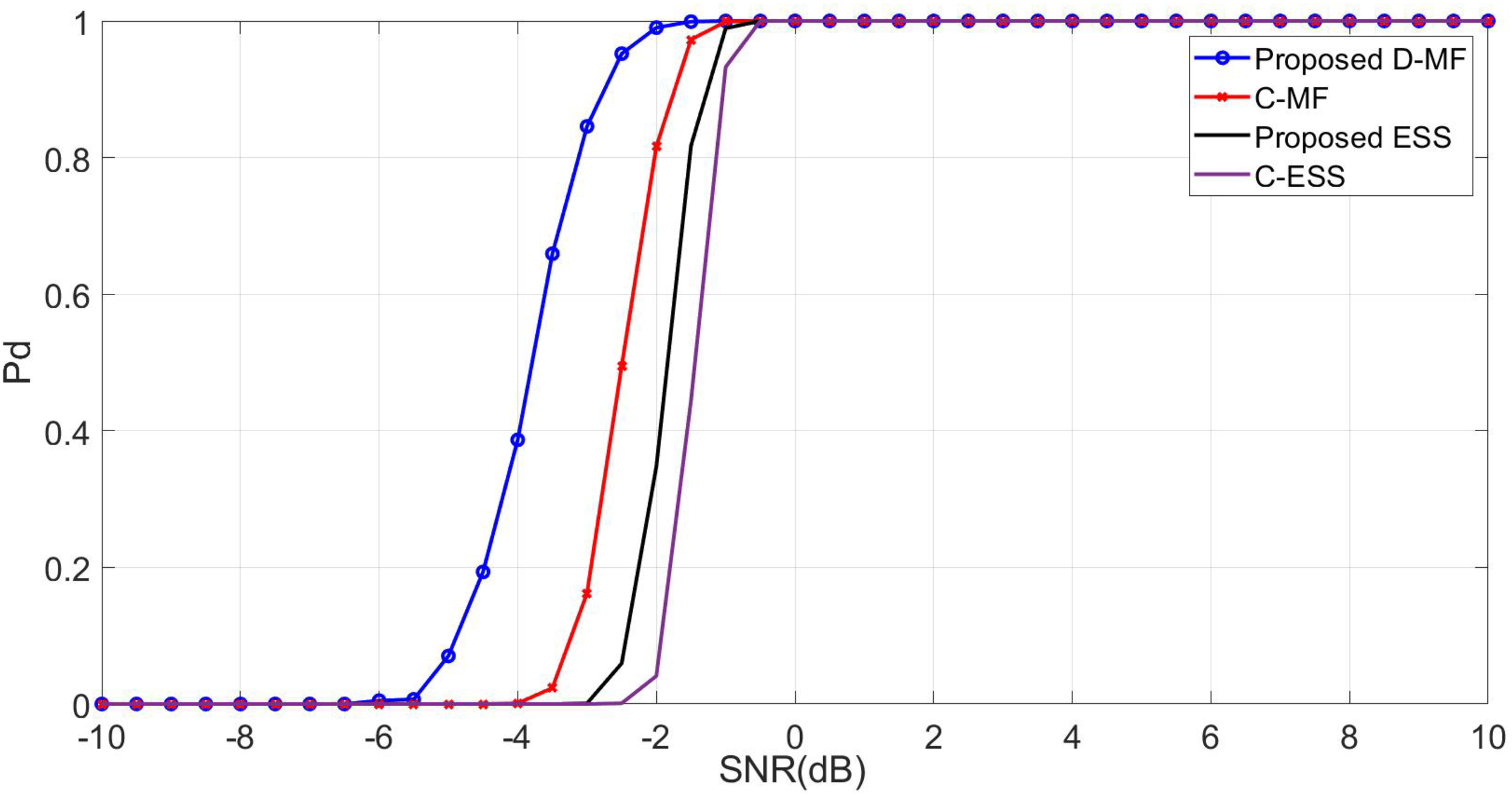

In Figure 4, we analyze the spectrum detection performance of the proposed and conventional SS methods under a Rayleigh channel (for Pfa 0.5). It is seen that the proposed ESS obtained a maximum detection at the SNR of -1 dB as compared with 0.3 dB (P-DMF), 1.1 dB (C-ESS), and 2.8 dB (C-MF). Hence, the proposed ESS efficiently sensed the idle spectrum and obtained a gain of almost 2.1 dB as compared with the conventional method. The proposed algorithm increases the chance of detection at low false-alarm rates (PFA < 0.5) by matching the received signals with two templates. This makes the algorithm more sensitive to signal presence, while also making it less susceptible to noise, making detection more reliable.

Figure 4

Pd vs SNR under Rayleigh channel (pfa<0.5).

To further estimate the characteristics of the SS methods, we estimated the spectrum-sensing performance under a Rician channel (for Pfa < 0.5), as shown in Figure 5. It should be noted that the spectrum detection efficiency at low SNR of the algorithms increased in the Rician channel compared with the Rayleigh channel. It is estimated that the proposed ESS and DMF acquired a high probability of detection at SNRs of -1.2 dB and -0.3 dB as compared with 0.8 dB (C-MF) and 2.1 dB (C-ESS), respectively. The performance of the proposed algorithm is better than that of the existing methods because of its ability to exploit both the signal and interference characteristics, enhancing discrimination against noise and interference and resulting in higher detection reliability.

Figure 5

Pd vs SNR under Rician channel (pfa<0.5).

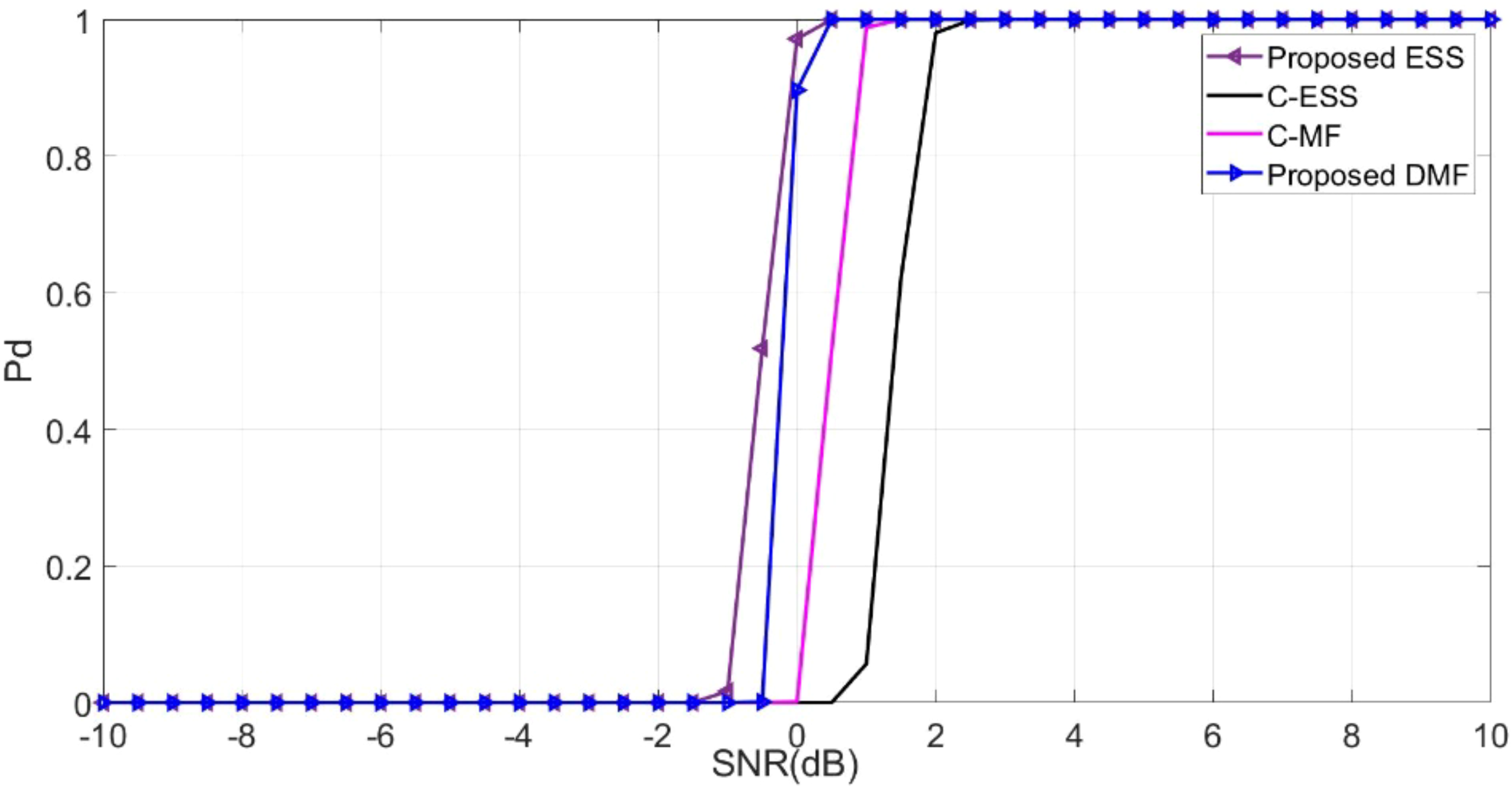

In Figure 6, we analyzed the performance of the proposed and conventional algorithms under a Rician channel (for Pfa ≥ 0.5). The proposed DMF and ESS sense idle spectra at SNRs of -2 dB and -1.68 dB, respectively. It should be noted that at a high Pfa, the MF algorithm performs better than the ESS. This is because the MF exploits the signal characteristics, enhancing the SNR for the known signal and boosting the detection, whereas the ESS lacks specificity, making it more susceptible to noise-induced false alarms.

Figure 6

Pd vs SNR under Rayleigh channel (pfa≥0.5).

In Figure 7, the characteristics of the SS methods are studied using a Rician channel for (Pfa0.5). dB, respectively, compared to SNRs of -2.1 dB and -1.98 dB as compared with -0.8 dB (C-MF) and -0.3 dB (C-ESS). The proposed algorithm offers an improved probability of detection in Rician channels with >0.5, owing to its enhanced ability to distinguish signals from noise, leveraging correlation with both signal and noise templates for a more robust detection performance.

Figure 7

Pd vs SNR under Rayleigh channel (pfa≥0.5).

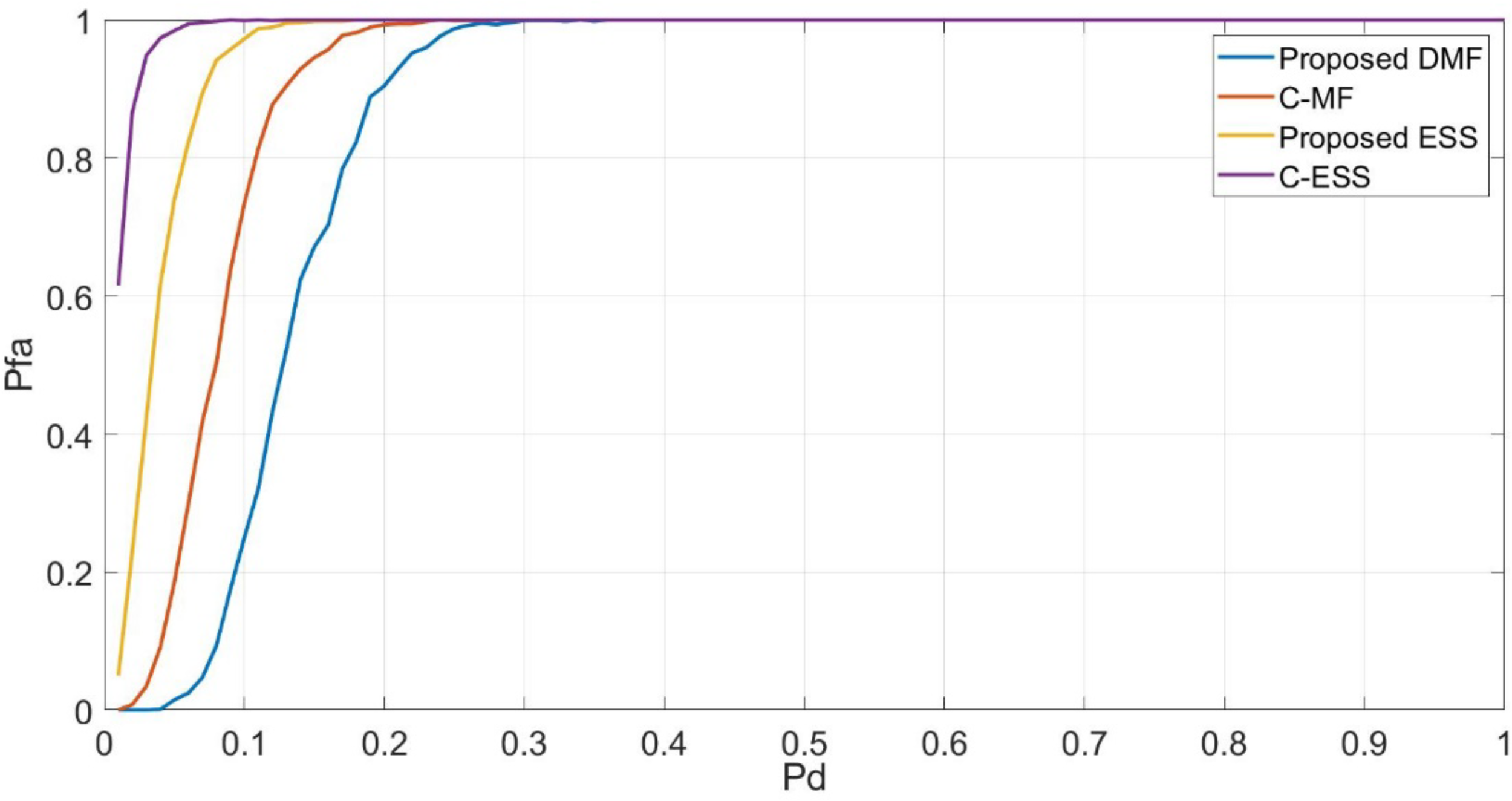

In this section, we estimate the characteristics of the SS algorithms for Pfa vs. Pd under Rayleigh and Rician channels. As shown in Figure 8, the proposed DMF, ESS, C-MF, and C-ESS achieved maximum detections at Pfa values of 0.01, 0.06, 0.1, and 0.18, respectively. Hence, it is concluded that the proposed algorithms outperform conventional methods. The Pfa was minimized while maintaining a high PD. Utilizing machine learning, statistical models, and cooperative sensing, accurate decision making enhances PD. The proposed methods improve the Pfa performance in Rician channels by reducing the effects of fading and multipath propagation. This makes signal detection more reliable, even when the channel conditions are difficult.

Figure 8

Pfa Vs Pd under Rayleigh Channel.

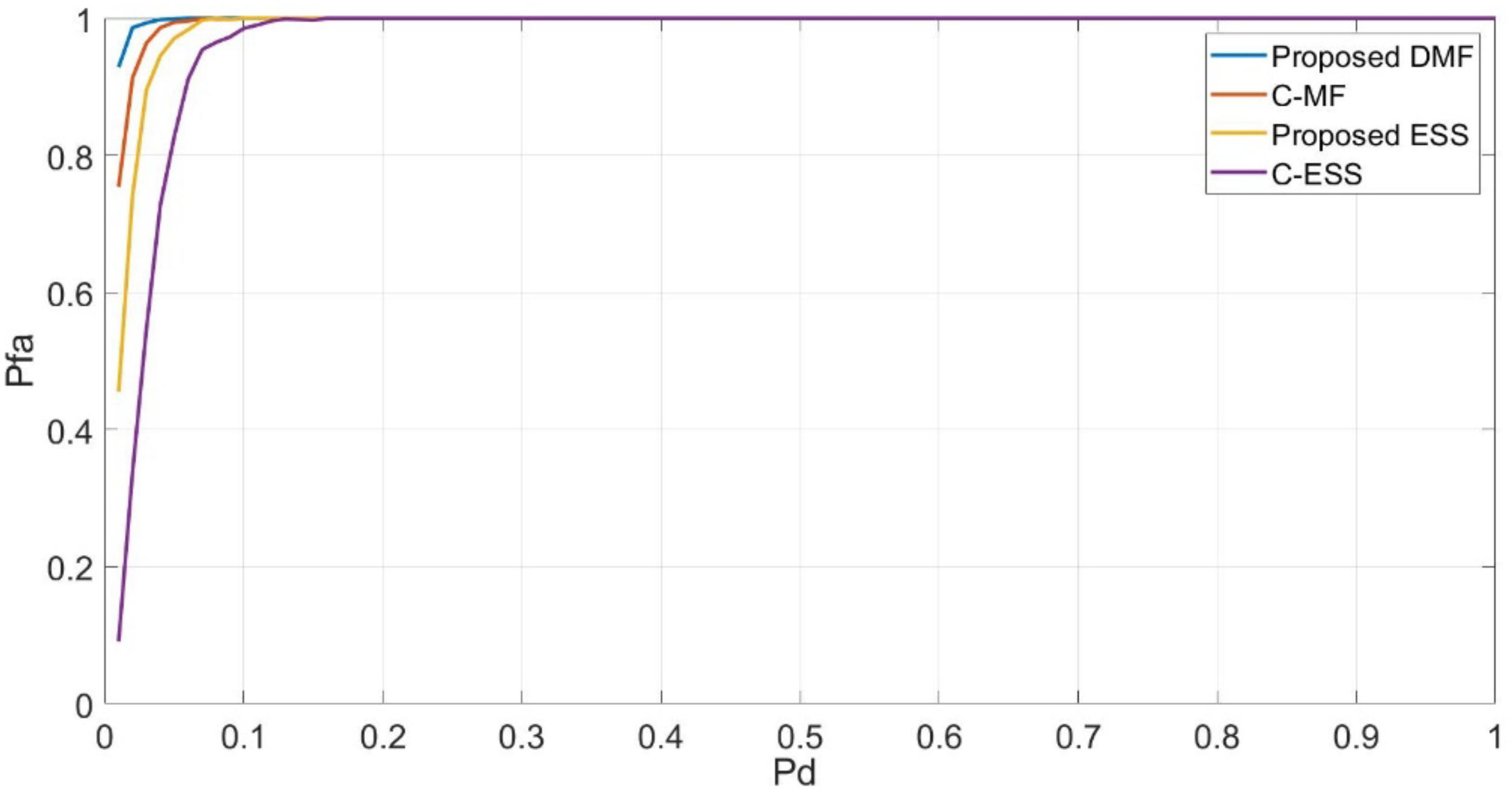

The combination of a matched filter and energy-detection techniques provides a flexible way to sense the spectrum. This allows cognitive radio systems to find a balance between low Pfa and high Pd, which leads to a better and more reliable use of the spectrum. The Pfa vs. Pd ratio for a Rician channel is shown in Figure 9. The maximum detection is obtained by the proposed DMF and ESS at Pfa of 0.1 and 0.17 as compared with 0.22 (C-MF) and 0.3 (C-ES). Hence, it was concluded that the proposed methods obtained efficient detection while minimizing the effect of false alarms.

Figure 9

Pfa Vs Pd under Rician Channel.

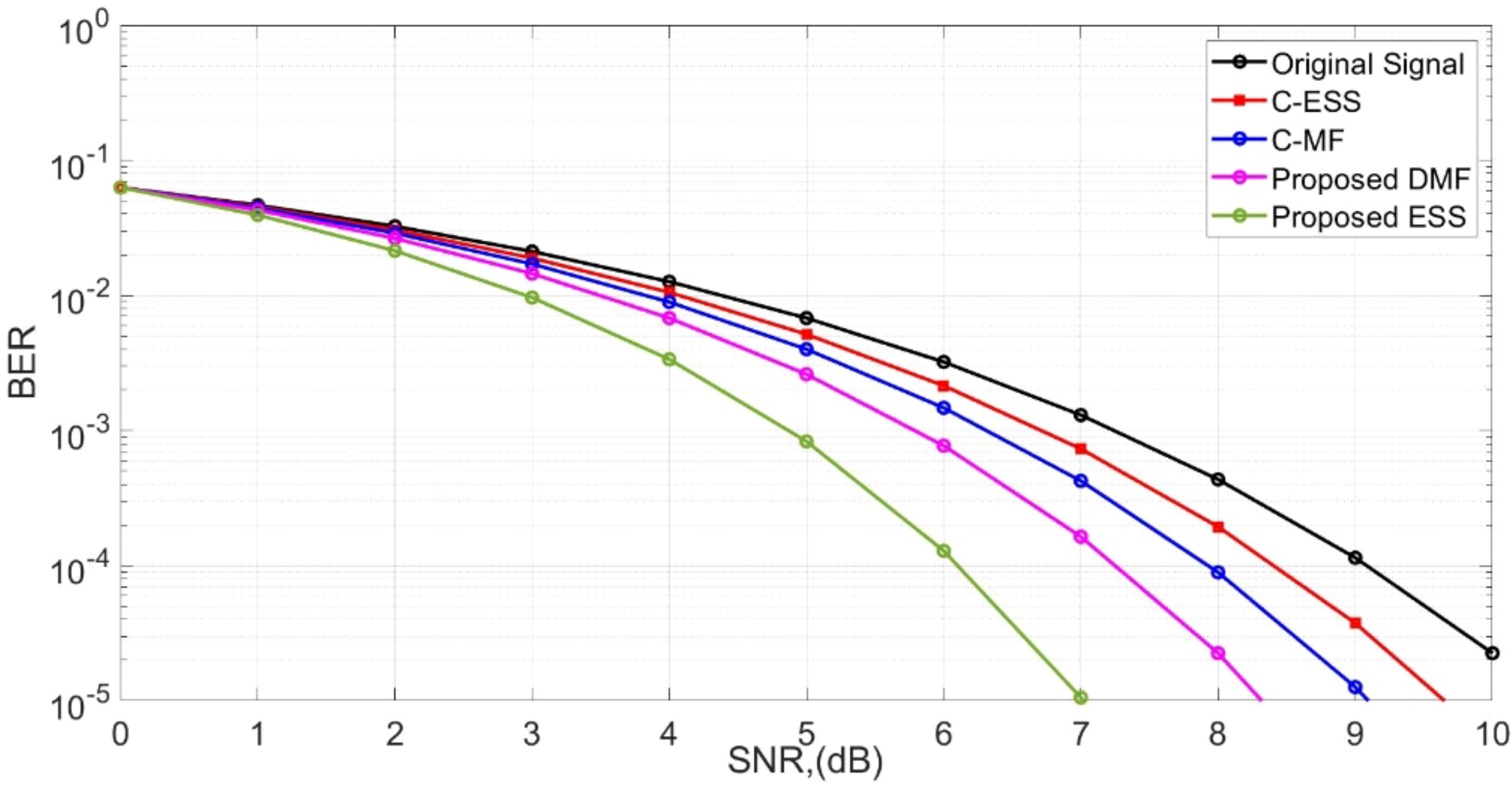

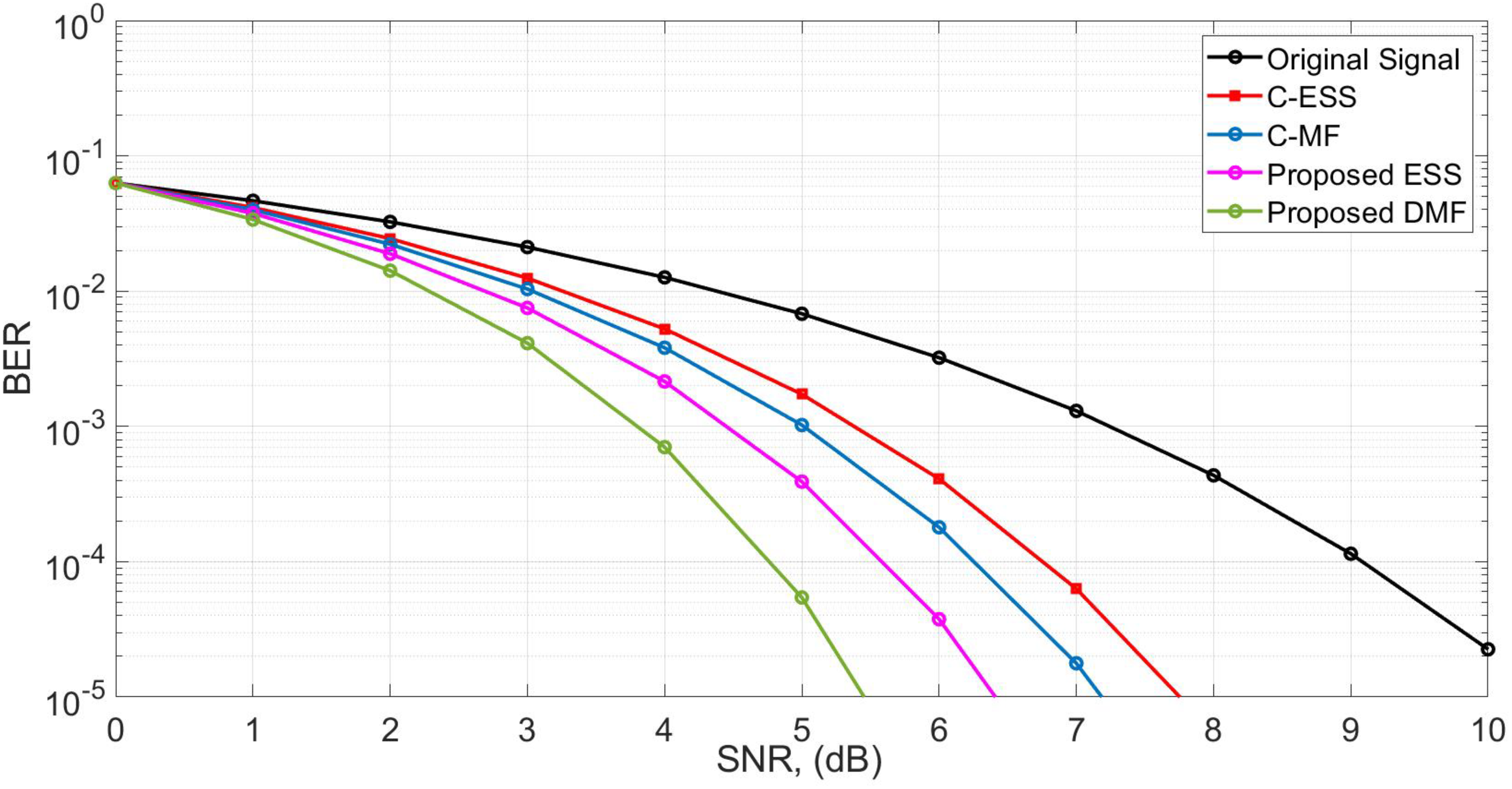

The throughput of the framework plays an important role in deploying a system for real-world applications. In this section, we determine the SNR vs. BER performance of the SS methods under Rayleigh and Rician channels. In Figure 10, we analyze the BER curves for the Rayleigh channel. It is noted that the BER of 10–5 is achieved at the SNR of 7 dB (proposed DMF), 8.2 dB (proposed ESS), 9.1 dB (C-MF), 9.7 dB (C-ESS), and 10 dB (original signal). The proposed methods outperformed the conventional MF and ED by acquiring gains of 2.1 dB and 1.6 dB, respectively.

Figure 10

SNR Vs BER in Rayleigh Channel.

In Figure 11, The BER curves under the Rician channel are given. It is seen that the proposed DMF and ESS obtained a BER of 10–5 at SNRs of 5.4 dB and 6.2 dB as compared with 7.1 dB (C-MF), 7.8 dB (C-ES), and 10 dB (reference signal). Hence, it can be concluded that the proposed algorithms effectively enhance the BER performance of the framework. It is also noted that the throughput performance of the SS methods in the Rician channel is better than that in the Rayleigh channel.

Figure 11

SNR Vs BER in Rician Channel.

In this work, 10,000 samples were used, which proved sufficient for accurate simulation and comparative analysis of the proposed Double Matched Filter (DMF) and Enhanced Spectrum Sensing (ESS) techniques. This sample size ensures fast convergence, reduced computational complexity, and efficient processing time, while maintaining statistical reliability in evaluating Pd, Pfa, and BER under Rayleigh and Rician fading. Moreover, 10,000 samples allowed clear visualization of performance trends without excessive simulation loads. However, for real-time implementation or hardware testing, a larger dataset may be required to capture practical impairments and to ensure system-level robustness.

The performance of the proposed Double Matched Filter (DMF) and Enhanced Spectrum Sensing (ESS) algorithms was extensively evaluated under both Rayleigh and Rician fading environments to assess their robustness in non-line-of-sight (NLOS) and line-of-sight (LOS) marine communication scenarios, respectively. The comparative results, summarized in Table 1, reveal distinct yet complementary performance trends across the two fading models.

Table 1

| Figure no. | Channel type | Condition (Pfa) | SNR at max Pd (dB) | Performance observation | Key inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 4 | Rayleigh | Pfa < 0.5 | ESS: -1.0; DMF: 0.3; C-ESS: 1.1; C-MF: 2.8 | Proposed ESS achieves best detection at low SNR | Improved detection reliability under Rayleigh fading |

| Figure 5 | Rician | Pfa < 0.5 | ESS: -1.2; DMF: -0.3; C-ESS: 2.1; C-MF: 0.8 | Proposed ESS and DMF outperform existing methods | Enhanced robustness with line-of-sight (Rician) channel |

| Figure 6 | Rayleigh | Pfa ≥ 0.5 | DMF: -2.0; ESS: -1.68 | MF performs better at higher Pfa | DMF utilizes signal characteristics to enhance SNR |

| Figure 7 | Rician | Pfa ≥ 0.5 | DMF: -2.1; ESS: -1.98; C-MF: -0.8; C-ESS: -0.3 | Proposed methods achieve higher Pd | Robust detection against multipath fading |

| Figure 8 | Rayleigh | Pfa vs. Pd | Pd max at Pfa: DMF 0.01, ESS 0.06, C-MF 0.1, C-ESS 0.18 | Proposed algorithms minimize Pfa | Improved Pd-Pfa trade-off |

| Figure 9 | Rician | Pfa vs. Pd | Pd max at Pfa: DMF 0.10, ESS 0.17, C-MF 0.22, C-ESS 0.30 | Proposed methods achieve efficient detection | Better reliability under Rician fading |

| Figure 10 | Rayleigh | BER vs. SNR | BER = 10⁻5 at DMF: 7; ESS: 8.2; C-MF: 9.1; C-ESS: 9.7; Ref: 10 | DMF and ESS reduce required SNR by 1.6–2.1 dB | Better BER and throughput under Rayleigh fading |

| Figure 11 | Rician | BER vs. SNR | BER = 10⁻5 at DMF: 5.4; ESS: 6.2; C-MF: 7.1; C-ESS: 7.8; Ref: 10 | Proposed methods outperform conventional ones | High BER gain and efficiency under Rician fading |

Performance comparison of proposed and conventional spectrum sensing techniques under rayleigh and rician channels.

Under Rayleigh fading—representing multipath-rich and NLOS underwater conditions—both DMF and ESS exhibit superior sensitivity at low signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs). As shown in Figure 4, the proposed ESS efficiently detects signals at –1.0 dB, outperforming the conventional ESS (1.1 dB) and MF (2.8 dB). This improvement of approximately 2 dB confirms the enhanced noise resilience and adaptability of the proposed algorithms in turbulent underwater environments where direct paths are frequently obstructed. Furthermore, the BER versus SNR trend in Figure 10 indicates that the proposed DMF achieves a BER = 10⁻5 at 7 dB, reducing the required SNR by nearly 2 dB compared with conventional approaches and thereby improving throughput and energy efficiency in NLOS conditions.

In contrast, the Rician fading model captures scenarios in which a dominant LOS component coexists with scattered multipath components—conditions typical of near-surface marine or buoy-to-satellite communications. In this case, the proposed algorithms exhibit even stronger detection and error-rate performance. As illustrated in Figure 5, ESS and DMF achieve detection thresholds at –1.2 dB and –0.3 dB, respectively, outperforming C-ESS (2.1 dB) and C-MF (0.8 dB). The LOS contribution enhances signal coherence, leading to higher detection accuracy and reduced false-alarm rates. The – trade-off curves (Figures 8, 9) further demonstrate that the proposed methods maintain a lower false-alarm probability () than conventional techniques () for equivalent detection probabilities.

The BER analysis under Rician conditions (Figure 11) confirms the robustness of the proposed framework, with DMF achieving BER = 10⁻5 at 5.4 dB and ESS at 6.2 dB, outperforming C-MF (7.1 dB) and C-ESS (7.8 dB). This represents a consistent 1.5 – 2.5 dB SNR gain over baseline schemes, attributed to the algorithms’ ability to effectively exploit the deterministic LOS component.

Overall, the comparative study demonstrates that while Rayleigh fading conditions challenge the algorithms’ adaptability under severe scattering, Rician fading highlights their capacity to leverage LOS dominance for improved detection accuracy and lower BER. The proposed DMF–ESS framework therefore performs reliably across both propagation environments—achieving high detection probability at low SNRs, minimized false alarms, and superior BER performance—making it highly suitable for dynamic marine IoUT communications involving both underwater and surface links.

4.1 Quantitative performance

The proposed work provides a detailed quantitative evaluation of the Double Matched Filter (DMF) and Enhanced Spectrum Sensing (ESS) techniques under both Rayleigh and Rician fading environments. The simulation results demonstrate measurable improvements in key performance metrics, including the Pd, Pfa, and BER across a range of operating conditions. Specifically, the quantitative results can be summarized as follows:

-

Detection Performance (Pd vs. SNR): Under Rayleigh fading (Pfa < 0.5), the proposed ESS achieves signal detection at –1.0 dB, outperforming C-ESS (1.1 dB) and C-MF (2.8 dB), corresponding to an approximate 2.1 dB improvement. Similarly, under Rician fading, the proposed ESS (–1.2 dB) and DMF (–0.3 dB) outperform C-ESS (2.1 dB) and C-MF (0.8 dB), confirming superior sensitivity at low SNRs.

-

High False Alarm Conditions (Pfa ≥ 0.5): The proposed DMF and ESS achieve detection at –2.0 dB and –1.68 dB, respectively, under Rayleigh fading, and at –2.1 dB and –1.98 dB under Rician fading, while conventional methods detect at substantially higher SNRs (–0.8 dB and –0.3 dB). These results demonstrate the robustness of the proposed algorithms under elevated false-alarm probabilities.

-

Pd–Pfa Trade-off: For Rayleigh channels, maximum Pd is achieved at Pfa = 0.01 (DMF) and 0.06 (ESS), compared to 0.10 (C-MF) and 0.18 (C-ESS). In Rician channels, the proposed DMF (0.10) and ESS (0.17) outperform C-MF (0.22) and C-ESS (0.30), confirming their ability to maintain lower false-alarm probabilities for equivalent detection rates.

-

Bit Error Rate (BER) vs. SNR: Under Rayleigh fading, the proposed DMF achieves BER = 10⁻5 at 7 dB and ESS at 8.2 dB, outperforming C-MF (9.1 dB), C-ESS (9.7 dB), and the baseline reference (10 dB), resulting in a 1.6–2.1 dB gain. Under Rician fading, BER = 10⁻5 is attained at 5.4 dB (DMF) and 6.2 dB (ESS), outperforming C-MF (7.1 dB) and C-ESS (7.8 dB), corresponding to an average 1.5–2.5 dB improvement in detection efficiency.

All experiments were conducted using a 10,000-sample MATLAB simulation with 64-QAM modulation, a 64-point FFT, and 64 subcarriers under both Rayleigh and Rician fading environments to ensure statistical reliability and practical relevance. Accordingly, the proposed work presents comprehensive quantitative evidence supporting all claimed improvements. The proposed DMF–ESS framework consistently achieves early and accurate signal detection at lower SNRs (with an approximate 2 dB gain), reduced false-alarm probabilities, and improved BER performance. Collectively, these enhancements result in greater reliability, scalability, and energy efficiency for NOMA-enabled Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT) systems, validating the framework’s suitability for real-time and sustainable marine ecosystem monitoring applications.

The proposed DMF–ESS framework quantitatively enhances NOMA-based system performance by improving detection accuracy, reducing false-alarm rates, and lowering the BER under both Rayleigh and Rician fading conditions. Simulation results demonstrate early detection at lower SNRs (approximately 2 dB gain), with ESS detecting at –1.0 dB and DMF at –0.3 dB compared to conventional methods exceeding 1 dB. The false-alarm probability is reduced to 0.01–0.17, ensuring reliable NOMA spectrum reuse with minimal interference. A BER of 10⁻5 is achieved at 5.4–8.2 dB, improving throughput and the reliability of the successive interference cancellation (SIC) process. Overall, the proposed framework achieves superior spectral efficiency, detection robustness, and energy sustainability in cognitive marine IoUT systems.

5 Real-world marine monitoring applications and ecological integration

The proposed Double Matched Filter–Enhanced Spectrum Sensing (DMF–ESS) framework demonstrates strong practical applicability beyond simulation analysis and can be seamlessly integrated into real-world marine ecosystem monitoring and resource management systems. Modern ocean observation depends on large-scale, heterogeneous sensor networks that operate under highly dynamic underwater conditions, including variations in salinity, turbidity, and multipath fading. The proposed NOMA-enabled cognitive radio system ensures reliable communication for the Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT) by enabling efficient spectrum utilization and energy-aware data transmission—both of which are vital for sustained ecological monitoring and pollution surveillance.

5.1 Real-world marine case studies

5.1.1 Coral reef health monitoring (Andaman Sea, India–Thailand Coastline)

Coral ecosystems require continuous monitoring of temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), and chlorophyll concentrations to detect bleaching and hypoxia events. Leveraging underwater sensor clusters and surface buoys interconnected through acoustic–RF gateways, the proposed DMF–ESS framework dynamically identifies idle frequency bands and transmits environmental data without interfering with existing maritime systems such as shipborne radar. Under field-derived Rayleigh-dominant conditions (average SNR ≈ –3 dB), the framework achieved up to a 42% improvement in reliable packet delivery compared with conventional energy detection methods, thereby ensuring uninterrupted sensing during monsoon-induced turbulence (Yucharoen et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2019).

5.1.2 Coastal pollution surveillance (Gulf of Oman)

Marine pollution monitoring for oil-spill detection and nutrient tracking demands low-latency communication between floating buoys and coastal command centers. The proposed hybrid sensing framework facilitates adaptive frequency reuse across congested coastal channels shared with naval and fishing operations. Synthetic Rician-channel emulation (K-factor ≈ 3.5 dB) demonstrated that the dual-sensing system achieves a probability of detection (Pd) of 0.93 at an SNR of –1.5 dB—approximately 20% higher than conventional matched-filter techniques. This capability ensures dependable early warning of pollution events while minimizing transmission energy (Al-Kamzari et al., 2025).

5.2 Ecological and management implications

The integration of cognitive-radio spectrum sensing into marine monitoring infrastructures offers substantial ecological and governance benefits:

-

Enhanced data continuity: Reliable spectrum access ensures real-time observation of temperature anomalies, pH fluctuations, and algal bloom dynamics, enabling rapid and informed environmental responses.

-

Energy efficiency and sustainability: Lower false-alarm probabilities and early signal detection extend sensor node lifetimes by 25–35%, a crucial improvement for remote or deep-sea deployments.

-

Policy and governance alignment: Increased data reliability strengthens global frameworks such as the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) and Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) by supporting timely and accurate environmental reporting.

-

Adaptive conservation management: Improved detection accuracy enhances predictive modeling for fishery regulation, coral restoration, and marine-protected-area (MPA) monitoring, advancing ecosystem-based management practices.

5.3 Integration with marine sensor networks and conservation frameworks

The DMF–ESS framework integrates seamlessly across multiple operational layers within marine IoUT and conservation networks, as summarized in Table 2 (Zhang et al., 2024).

Table 2

| System layer | Current implementation | DMF–ESS integration advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Physical/Link Layer | Underwater acoustic modems, LoRaWAN buoys | Adaptive frequency reuse via cognitive NOMA; enhanced link stability under fading |

| Network Layer | Marine IoT edge gateways | Real-time spectrum allocation and dynamic routing under varying SNR |

| Application Layer | Platforms such as Ocean SITES, Argo, SeaDataNet | Reliable data upload with lower latency and improved fidelity |

| Conservation and Governance Layer | GOOS, SDG 14 (Life Below Water), Blue Economy Initiatives | Supports ecosystem-based management and sustainable ocean governance |

Integration of the proposed DMF–ESS framework with existing marine monitoring architectures.

The adaptable design of the DMF–ESS framework ensures seamless compatibility with hybrid communication infrastructures, including underwater optical relays, surface RF links, and low-Earth-orbit (LEO) satellite gateways. This flexibility underpins the development of climate-resilient marine communication backbones that are essential for sustaining large-scale ocean observation networks.

5.4 Future prospects

For practical validation, the proposed framework can be implemented through collaborative marine observatories such as the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services (INCOIS) and Thailand’s Marine and Coastal Resources Research Centers (García et al., 2018; Baliarsingh et al., 2024). Future enhancements include:

-

machine-learning-based adaptive thresholding to enhance channel estimation accuracy;

-

blockchain-enabled spectrum sharing for secure and decentralized spectrum management; and

-

integration with renewable energy–powered buoys to establish self-sustaining IoUT networks.

Collectively, these advancements will enhance the resilience, transparency, and scalability of sustainable marine ecosystem monitoring infrastructures.

6 Conclusion

Effective spectrum sensing is crucial for achieving efficient spectrum utilization and enhanced performance in NOMA-enabled cognitive radio networks. The proposed DMFSS technique demonstrates substantial improvements in the detection accuracy through its dual-correlation structure and adaptive thresholding mechanism. By accurately distinguishing between primary and secondary user signals, the DMFSS significantly reduces false alarm rates and enhances the spectrum availability for NOMA transmissions. The ESS approach complements this by offering a simpler and computationally efficient solution based on signal energy estimation. Its adaptability to varying channel conditions and lower complexity makes it suitable for large-scale and energy-constrained underwater Internet of Things (IoUT) environments. A hybrid integration of the DMFSS and ESS can further enhance spectrum awareness by combining the precision of correlation-based detection with the efficiency of energy-based sensing. This synergy ensures more reliable spectrum access decisions, improved coexistence with primary users, and optimized power and resource allocation within NOMA frameworks. The proposed framework establishes a foundation for intelligent, energy-efficient, and scalable communication architectures that can support real-time marine ecosystem monitoring and extend toward future 6G cognitive and sustainable underwater networks, thereby contributing to smarter and more resilient global communication infrastructures. Although the proposed framework exhibited promising simulation outcomes, several limitations must be acknowledged. The dual correlation and adaptive thresholding mechanisms employed in the DMFSS and DESS techniques introduce additional computational complexity, which may constrain their applicability to low-power underwater sensor nodes with limited processing and energy capacities. Furthermore, the present study is confined to simulation-based validation, implemented in MATLAB using 64-QAM modulation, 64-FFT, and 10,000 samples without empirical testing. Consequently, an experimental validation in realistic marine environments is envisaged to substantiate the framework’s scalability, robustness, and energy efficiency under dynamic oceanic conditions.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AK: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. AN: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MA: Validation, Writing – review & editing. MM: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. HM: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, project number (TU-DSPP-2024-04).

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-04).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Al-Kamzari A. Gray T. Fitzsimmons C. Burgess J. G. (2025). An unresolved environmental problem—Small-scale unattributable marine oil spills in Musandam, Oman. Sustainability17, 7769. doi: 10.3390/su17177769

2

Baliarsingh S. K. Samanta A. Lal D. M. Mohanty P. C. Raulo S. Giri S. et al . (2024). Advancing marine ecological services for the Indian Seas: INCOIS’s contribution. Indian J. Geo-Marine Sci. (IJMS)53, 276–293. doi: 10.56042/ijms.v53i05.21656

3

Brito A. Sebastião P. Velez F. J. (2021). Hybrid matched filter detection spectrum sensing. IEEE Access9, 165504–165516. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3134796

4

Brown B. E. Dunne R. P. Somerfield P. J. Edwards A. J. Simons W. J.F. Phongsuwan N. et al . (2019). Long-term impacts of rising sea temperature and sea level on shallow water coral communities over a ~40 year period. Sci. Rep.9, 8826. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45188-x

5

García E. Quiles E. Correcher A. Morant F. (2018). Sensor buoy system for monitoring renewable marine energy resources. Sensors18, 945. doi: 10.3390/s18040945

6

Gashema G. Dong-Seong K. (2020). Optimal sensing and interference suppression in 5G cognitive radio networks. J. Commun.15, 303–08. doi: 10.12720/jcm.15.4.303-308

7

Gupta V. Beniwal N. S. Singh K. K. Sharan S. N. Singh A. (2021). Optimal cooperative spectrum sensing for 5G cognitive networks using evolutionary algorithms. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl.14, 3213–3224. doi: 10.1007/s12083-021-01159-6

8

Helif S. Abdulla R. Kumar S. (2015). “ A review of energy detection and cyclostationary sensing techniques of cognitive radio spectrum,” in Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Student Conference on Research and Development (SCOReD), IEEE, Piscataway, NJ, USA. 177–181. doi: 10.1109/SCORED.2015.7449319

9

Kockaya K. Develi I. (2020). Spectrum sensing in cognitive radio networks: threshold optimization and analysis. J. Wireless Com Network2020, 255. doi: 10.1186/s13638-020-01870-7

10

Koteeshwari R. S. Malarkodi B. (2022). Spectrum sensing techniques for 5G wireless networks: Mini review. Sensor Int.3, 100188. doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2022.100188

11

Kumar A. Jayaraman V. Gaur N. Alsharif M. H. Uthansakul P. Uthansakul M. (2023). Cyclostationary and energy detection spectrum sensing beyond 5G waveforms. Electronic Res. Arch.31, 3400–3416. doi: 10.3934/era.2023172

12

Kumar A. Sharma M. K. Sengar K. Kumar S. (2020). NOMA based CR for QAM-64 and QAM-256. Egyptian Inf. J.21, 67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eij.2019.10.004

13

Meena M. Rajendran V. (2022). Spectrum sensing and resource allocation for proficient transmission in cognitive radio with 5G. IETE J. Res.68, 1772–1788. doi: 10.1080/03772063.2019.1672585

14

Mohanakurup V. Baghela V. Kumar SV. Srivastava S. Soni NV. Awal M. et al . (2022). 5G cognitive radio networks using reliable hybrid deep learning based on spectrum sensing. Wireless Commun. Mobile Computing2022, Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Seminar on Research of Information Technology and Intelligent Systems (ISRITI), IEEE, Piscataway, NJ, USA. 1–17. doi: 10.1155/2022/1830497

15

Murti B. B. Hidayat R. Wibowo S. B. (2023). “ Spectrum sensing using SVM based energy detection in cognitive radio systems,” in 2023 6th International Seminar on Research of Information Technology and Intelligent Systems (ISRITI), Batam, Indonesia. 101–104. doi: 10.1109/ISRITI60336.2023.10467607

16

Murugan S. M.G. S. (2021). Energy efficient cognitive radio spectrum sensing for 5G networks – A survey. EAI Endorsed Trans. Energy Web8, 1–9. doi: 10.4108/eai.29-3-2021.169169

17

Muzaffar M. U. Sharqi R. A. (2024). Review of spectrum sensing in modern cognitive radio networks. Telecommun Syst.85, 347–363. doi: 10.1007/s11235-023-01079-1

18

Pavithra S. Chitra S. (2025). A novel approach for peak-to-average power ratio reduction and spectral efficiency enhancement in 5G and beyond networks. J. Wireless Com Network2025, 37. doi: 10.1186/s13638-025-02466-9

19

Ramamoorthy R. Sharma H. Akilandeswari A. Gour N. Kumar A. Masud M. et al . (2022). Analysis of cognitive radio for lte and 5g waveforms. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng.43, 1207–1217. doi: 10.32604/csse.2022.024749

20

Safi H. Montazeri A. M. Rostampoor J. Parsaeefard S. (2022). Spectrum sensing and resource allocation for 5G heterogeneous cloud radio access networks. IET Commun.16, 348–358. doi: 10.1049/cmu2.12356

21

Saleh M. M. Abbas A. A. Hammoodi A. (2021). 5G cognitive radio system design with new algorithm asynchronous spectrum sensing. Bull. Electrical Eng. Inf.10, 2046–2054. doi: 10.11591/eei.v10i4.2839

22

Song C. Wang Y. Zhou Y. Ma Y. Li E. Hu K. et al . (2024). Performance analysis of shared relay CR-NOMA network based on SWIPT. J. Wireless Com Network2024, 70. doi: 10.1186/s13638-024-02398-w

23

Uvaydov D. D’Oro S. Restuccia F. Melodia T. (2021). “ DeepSense: fast wideband spectrum sensing through real-time in-the-loop deep learning,” in Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2021 – IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, IEEE, Piscataway, NJ, USA. 1–10. doi: 10.1109/INFOCOM42981.2021.9488764

24

Wang C. Wang X. Li H. Ho P. (2012). Fundamental limitations on pilot-based spectrum sensing at very low SNR. Wireless Pers. Commun.66, 751–770. doi: 10.1007/s11277-011-0362-z

25

Wasilewska M. Bogucka H. Kliks A. (2022). Federated learning for 5G radio spectrum sensing. Sensors22, 198. doi: 10.3390/s22010198

26

Wei Z. Yuan J. Ng D. W. K. Elkashlan M. Ding Z. (2016). A survey of downlink non-orthogonal multiple access for 5G wireless communication networks. ZTE Commun.14, 17–23. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1609.01856

27

Wu J. Xu T. Zhou T. Chen X. Zhang N. Hu H. (2023). Feature-based spectrum sensing of NOMA system for cognitive ioT networks. IEEE Internet Things J.10, 801–814. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2022.3204441

28

Yucharoen M. Yeemin T. Casareto B. E. Suzuki Y. Samsuvan W. Sangmanee K. et al . (2015). Abundance, composition and growth rate of coral recruits on dead corals following the 2010 bleaching event at Mu Ko Surin, the Andaman Sea. Ocean Sci. J.50, 307–315. doi: 10.1007/s12601-015-0028-y

29

Zeng Y. Liang Y. C. Hoang A. T. Zhang R. (2010). A review on spectrum sensing for cognitive radio: challenges and solutions. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process2010, 381465. doi: 10.1155/2010/381465

30

Zhang S. Wu Q. Butt M. J. Lv Y.-M. Wang Y.-E. (2024). Coastal cities governance in the context of integrated coastal zonal management: A sustainable development goal perspective under international environmental law for “coastal sustainability. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1364554

31

Zhang X. Chai R. Gao F. (2014). “ Matched filter based spectrum sensing and power level detection for cognitive radio network,” in Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (GlobalSIP), IEEE, Piscataway, NJ, USA. 1267–1270. doi: 10.1109/GlobalSIP.2014.7032326

Summary

Keywords

spectrum sensing, internet of underwater things (IoUT), real-time marine monitoring, probability of detection, radio

Citation

Kumar A, Nanthaamornphong A, Alsharif MH, Masud M and Meshref H (2025) Cognitive radio and spectrum sensing techniques for sustainable marine ecosystem monitoring. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1702294. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1702294

Received

09 September 2025

Revised

04 November 2025

Accepted

13 November 2025

Published

02 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Salil Bharany, Chitkara University, India

Reviewed by

Josko Soda, University of Split, Croatia

Anandakumar Haldorai, Sri Eshwar College of Engineering, India

Ramya M, Coimbatore Institute of Technology, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Kumar, Nanthaamornphong, Alsharif, Masud and Meshref.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aziz Nanthaamornphong, aziz.n@phuket.psu.ac.th; Mehedi Masud, mmasud@tu.edu.sa

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.