Abstract

Introduction:

The Blue Amazon represents an extensive coastal zone with high biodiversity and wide salinity variation, which poses challenges for marine fish farming, particularly regarding the efficiency of biofilters in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). In this context, açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea), previously evaluated in freshwater, emerge as a promising alternative for use as filter media under different salinity conditions. The objective of this study was to evaluate the potential of açaí seeds as substrate in RAS biofilters, analyzing their acute and chronic impact on the physicochemical parameters of water and the removal of ammonia, nitrite and nitrate over 28 days.

Methods:

The experiment was conducted in six independent systems (three aquaria each), subjected to salinities of 0, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 35‰. After Acute (0, 20, 40, 60,80,100 and 120 minutes) and chronic (2,3,4,14,21 and 28 days) salinity change, water samples were collected to measure physicochemical quality and to assess nitrification efficiency and nitrogen compound removal.

Results:

Higher oxygen consumption and ammonia clearance were observed at 0, 7 and 14‰ after 120 minutes of salinity change, while nitrate accumulation was significantly higher in freshwater. In long term, after 28 days, ammonia clearance was significantly lower at 35‰, though nitrate accumulation was not affected by salinity. The highest ammonia removal rates were recorded in the 0‰ and 7‰ treatments.

Discussion:

The results demonstrate that açaí seeds are capable of removing ammonia after a few minutes and can sustain the growth of nitrifying bacteria under different salinity levels, although more efficiently in low salinity waters (seven times).

1 Introduction

In the Brazilian Amazon, aquaculture has become consolidated as a strategic agricultural activity to produce aquatic organisms, standing out as an alternative to fishing in providing animal protein of high biological value. In addition to contributing to food security, the sector plays an important role in generating employment and income. In this context, freshwater fish farming is the most representative segment, with a predominance of native species such as tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum), other “round fish” and their hybrids, as well as pirarucu (Arapaima gigas) (Valladão et al., 2018; IBGE, 2024; Peixe, 2024). Regional aquaculture production is concentrated mainly in extensive and semi-intensive earthen pond systems, followed by intensive net cage farming (Hilsdorf et al., 2022; Rodrigues et al., 2024; Pacheco et al., 2025).

The Amazon Basin, formed by the Amazon River and its tributaries, holds the largest reserve of surface freshwater available on the planet (Araujo-Lima and Ruffino, 2003). In addition, the Northern region of the country comprises an extensive coastal zone with a broad continental shelf, known as the "Blue Amazon", characterized by vast mangrove areas and high biodiversity of fisheries importance (Gerhardinger et al., 2018), which indicates great potential for marine fish farming. However, the high discharge of the Amazon River — responsible for about 20% of all freshwaters released into the world’s oceans (Castello et al., 2013)— combined with the high rainfall characteristic of the equatorial climate, leads to strong salinity fluctuations, from 0‰ to 35‰. This represents a challenge for marine aquaculture, since stable salinity is necessary to maintain proper fish osmoregulation during confined production, although the optimal salinity varies according to species and life stage, especially in estuarine and migratory species.

Nevertheless, even with the abundance of water and high biodiversity, the development of aquaculture in the Amazon still faces challenges, mainly due to environmental variability and the need to ensure the sustainability of production systems. Therefore, production intensification must be accompanied by practices aimed at sustainable aquaculture, minimizing environmental impacts without compromising productivity (Pretty et al., 2010). In this context, the Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) represents a solution for achieving high production levels with lower environmental impact. RAS operates through the continuous treatment of wastewater from aquaculture tanks using mechanical and biological filters, in which nitrifying bacteria metabolize nitrogen compounds, and the treated and higher-quality water is returned to the production tanks. Thus, this technique reduces the use of water and land, improves the efficiency of resource use, such as water, and makes intensive aquaculture more sustainable (Owatari et al., 2018; Timmons and Vinci, 2022). On the other hand, there is a need for daily water exchanges of around 20%, which can be a limiting factor in marine aquaculture if the intake of coastal water does not provide an adequate salinity level.

RAS biofilters support the proliferation of nitrifying bacteria, especially those from the genera Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter, which aerobically oxidize TAN into nitrite and then into nitrate, making the water suitable for aquatic animal farming (Ruiz et al., 2020). Various substrates can be used as attachment media for nitrifying bacteria in the biofilter (Wafula et al., 2023). Some agricultural by-products, such as wood chips, wheat straw (Saliling et al., 2007), coconut shells, polyurethane foam, ceramic beads, plastic beads (Mnyoro et al., 2024), biochar, zeolite (Paul and Hall, 2021) and eggshells (Marques et al., 2024) have shown effectiveness in nitrification, indicating their potential for use in RAS biofilters. However, replicating such conditions in marine aquaculture environments can lead to osmoregulatory stress in nitrifying bacteria, reducing the efficiency of TAN oxidation (Kinyage et al., 2019; Fossmark et al., 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to identify biological media that remain efficient under various salinity levels.

In the Brazilian Amazon, açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea), a by-product of pulp extraction, have been successfully tested as biological media in freshwater RAS and aquaponic systems (Sterzelecki et al., 2022; Nascimento et al., 2023). The effectiveness is likely due to the lignified fibrous tegument that remains attached to the seed after pulp extraction (de Oliveira and Schwartz, 2018; de Lima et al., 2021), forming a structure like filaments that may increase the surface area available for the proliferation of nitrifying bacteria. This highlights the urgent need to develop reuse strategies for this by-product, as the seeds can serve as a substrate for nitrifying bacteria, optimizing waste use, reducing environmental impact and lowering production costs (da Costa et al., 2022; Nascimento et al., 2023). However, no studies have evaluated the use of açaí seeds as biological media in marine RAS. In this context, we hypothesize that açaí seeds can serve as a substrate for the attachment of nitrifying bacteria in biological filters, thereby contributing to the nitrification process in RAS operating under different salinity levels. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the potential of açaí seeds as a filtering medium in RAS over 28 days, testing different water salinity levels and evaluating their acute and chronic impact on water quality during the trial.

2 Materials and method

2.1 Experimental design

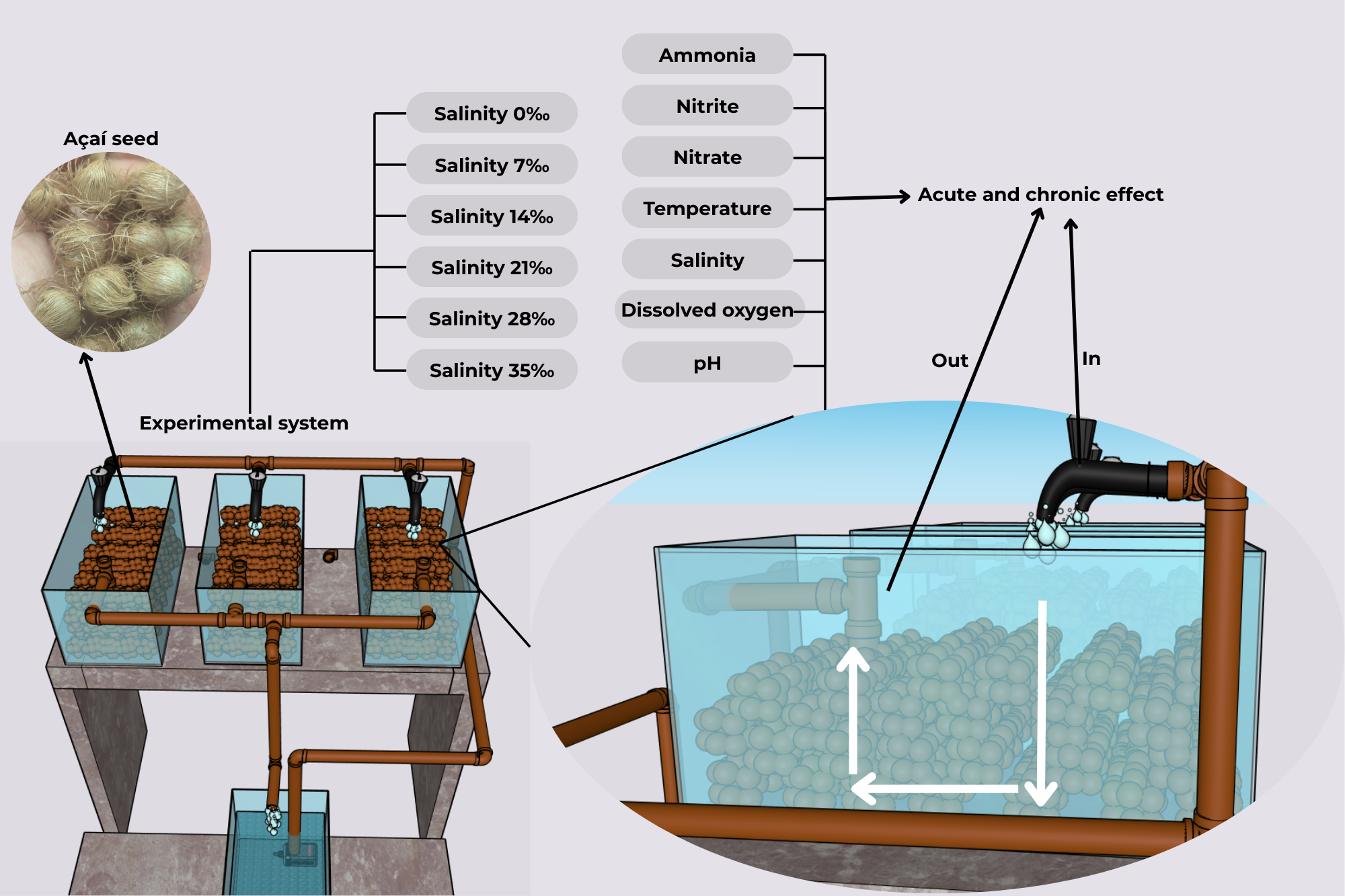

The experimental system was composed of six independent recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), each consisting of four aquariums with a useful volume of 28 L. Three of these aquariums were filled with açaí seeds (biofilter) and served as replicates, while the fourth functioned as a sump containing a pump that circulated the water toward the experimental units, which then returned to the sump by gravity (Figure 1). Aeration in the system occurred through water fall into the aquaria, both from pump action and gravitational return. The açaí seeds were obtained as donations from pulp extraction facilities in the city of Belém, Pará State, Brazil. The seeds underwent a preparation process that included washing with running water to remove residues. After cleaning, the seeds were placed into the systems. To standardize the substrate weight in the systems, 750 g of seeds were used per aquarium, totaling 2.250 kg per RAS.

Figure 1

Schematic design of the independent RAS units evaluated in each treatment. The arrows represent the water flow through the three biological filters composed of Açaí seed (Euterpe oleracea) inside the aquariums, indicating the inflow (in) and outflow (out) of water through the filters. The water flows by gravity into the fourth isolated aquarium, which contains a pump responsible for circulating the water throughout the system. In addition, the diagram includes captions indicating the treatments evaluated in each experimental system, as well as the acute and chronic effects of nitrification and the physicochemical parameters of the water.

The experiment was conducted over 28 days and consisted of six different salinities: 0‰, 7‰, 14‰, 21‰, 28‰, and 35‰, in the independent RAS units (Figure 2). Such ranges correspond to the salinity variations that occur in the Amazon coastal zone and could affect marine fish farming, particularly regarding the logistics of collecting water from the natural environment to meet production demands. Total system recirculation occurred every 7 minutes through submersible aquarium pumps with a maximum flow rate of 530 L h-¹ (Walter PUMP, model XT-530) in each treatment (Figure 1). To assess nitrification activity in the biological filters, 0.465 g of ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4) was added daily to each system throughout the trial.

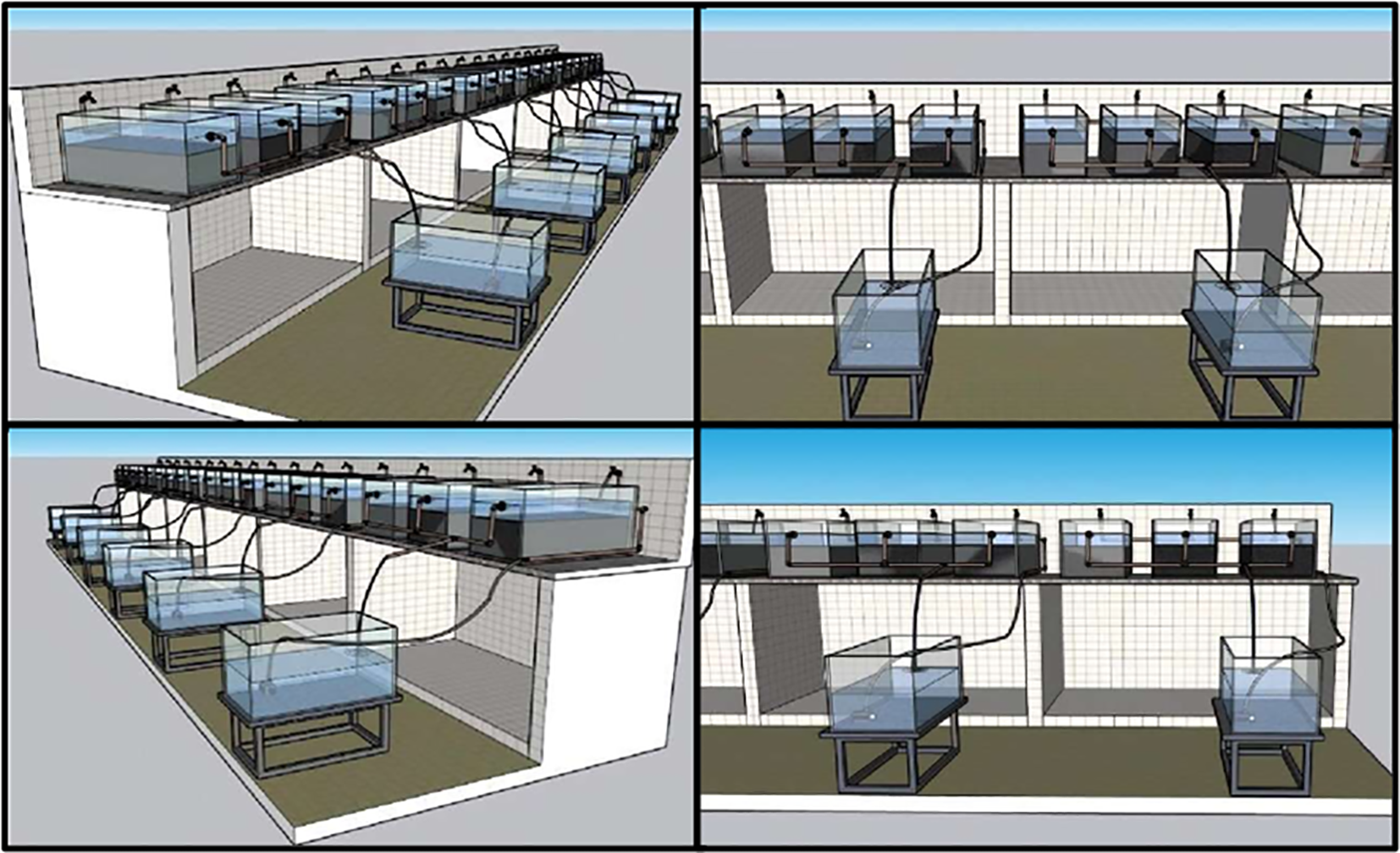

Figure 2

Independent experimental systems evaluated under different water salinities: 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35‰.

The experiments were conducted in triplicate in 28 L aquariums, artificially salinized with salt of the VeroSal Corais (Veromar, Campinas, SP, Brazil) formulated with sodium (9 g L-1), chlorides (16 g L-1), carbonates (110 mg L-1), calcium (420 mg L-1), magnesium (1,250 mg L-1), sulfates (2.5 g L-1), bromides (60 mg L-1), boron (5 mg L-1), strontium (6 mg L-1) and trace elements, according to the manufacturer. The salt was mixed with water in ppt according to the treatments evaluated. The experimental systems had an average flow rate of 5 mL minute-1 and the salinization rate corresponded to 7% h-1. Two exposure periods were evaluated in the trial: acute and chronic. In the acute assay, water samples were collected at 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 and 120 minutes to evaluate the immediate response of the nitrifying bacteria. In the chronic trial, water quality was monitored on days 0, 7, 14, 21 and 28 to evaluate the long-term effects. In both trials, the salinity adjustments, as well as the addition of ammonium sulfate and açaí seeds without pre-treatment to aquariums, were carried out immediately on the first day of the experiment.

2.2 Physicochemical parameters of water

Water quality parameters were measured daily at the inlet and outlet of the systems throughout the experimental period. These parameters included temperature (T) and dissolved oxygen (DO, mg L-¹) using a ProODO optical oximeter and digital thermometer (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA), electrical conductivity (EC, in μS cm-¹) using a digital conductivity meter (TDS & EC meter KP-AA008, Brazil), pH using a digital pH meter (AKSO, São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil), and salinity using a refractometer (RM-T32 ATC, 0–35% BRIX ACUCAR).

2.3 Nitrogen compounds

Water analysis included total ammonia determined according to Bolleter et al. (1961), with absorbance readings at 630 nm using a spectrophotometer (Ionlab Equipamentos Laboratoriais e Hospitalares Ltda., Araucária, PR, Brazil); nitrite was analyzed with readings at 540 nm, and nitrate with readings at 220 nm/270 nm. All following the methodology described by Lipps et al. (2023).

2.4 Ammonia clearance

To quantify ammonia (NH3) removal by nitrifying bacteria in the açaí seed, the concentration variation was determined over a 20-minute interval, considering a salinity of 35‰. The initial and final NH3 concentrations (mg L-¹) were calculated.

For each replicate, the amount of NH3 removed was calculated:

or

The amount of NH3 removed is the difference between the initial concentration and the final average:

(If ΔC is positive, it means removal; if negative, there was an increase)

This way:

Cinitial is the concentration at time 0 min (mg L-¹),

Cfinal,i is the concentration at time of 20 min (mg L-¹).

The average removal between replicates was then obtained:

Where:

n is the number of replicates in the 20-minute time frame.

The removal rate (R) was then calculated in absolute terms (mg NH3 L-¹ 20 min-¹), and in relative terms, the following formula was used:

For the final calculation, the initial value of 1.832 mg L-¹ was used, obtaining the average removal rate and efficiency. This procedure allowed standardizing the analysis and comparing the performance of the açaí seed biofilter across different salinities.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The assumptions of homoscedasticity and normality were verified. For parametric variables, one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test were used to detect significant differences (p < 0.05). For non-parametric results, the Kruskal-Wallis’s test and Dunn’s post hoc test were applied to explore significant differences (p < 0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 software.

3 Results

3.1 Physicochemical parameters of water

Salinity had a significant effect only on the DO (dissolved oxygen) parameter at the inlet and outlet of the biological filters among the treatments (p < 0.05). The highest DO was observed at the inlet in the treatment with 7‰ salinity (6.48 mg L-¹) and the lowest in the 0‰ salinity treatment (3.59 mg L-¹). At the outlet, DO was highest in the treatments with 7‰ and 14‰ salinities (5.31 and 5.21 mg L-¹, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Parameter | Water salinity | p-value | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0‰ | 7‰ | 14‰ | 21‰ | 28‰ | 35‰ | |||||||||

| Inlet | Outlet | Inlet | Outlet | Inlet | Outlet | Inlet | Outlet | Inlet | Outlet | Inlet | Outlet | Inlet | Outlet | |

| T (°C) | 27.79 ± 0.37 | – | 27.89 ± 0.31 | – | 27.87 ± 0.33 | 28.13 ± 0.31 | – | 28.20 ± 0.26 | – | 28.26 ± 0.25 | – | 0.35ns | – | |

| DO (mg L-1) | 3.59 ± 0.21d | 2.00 ± 0.31c | 6.48 ± 0.08a | 5.31 ± 0.08a | 5.79 ± 0.06ab | 5.21 ± 0.08a | 5.40 ± 0.07bc | 3.99 ± 0.11b | 5.23 ± 0.06c | 4.08 ± 0.05b | 5.00 ± 0.19cd | 4.08 ± 0.13b | <0.01* | <0.01* |

| pH | 6.96 ± 0.17 | 6.93 ± 0.11 | 7.04 ± 0.17 | 6.96 ± 0.16 | 7.03 ± 0.16 | 7.05 ± 0.16 | 7.27 ± 0.14 | 7.22 ± 0.15 | 7.36 ± 0.14 | 7.38 ± 0.14 | 6.46 ± 0.34 | 7.52 ± 0.16 | 0.61ns | 0.05ns |

physicochemical parameters of water evaluated after 28 days in the experimental systems.

* Data are presented as mean ± SEM. In each row, values (inlet and outlet) followed by different letters indicate significant differences according to Dunn's test at 5% probability. *p < 0.01, ns: not significant.

On the other hand, water salinity had no influence (p > 0.05) on temperature and pH parameters (Table 1).

3.2 Nitrogen compounds

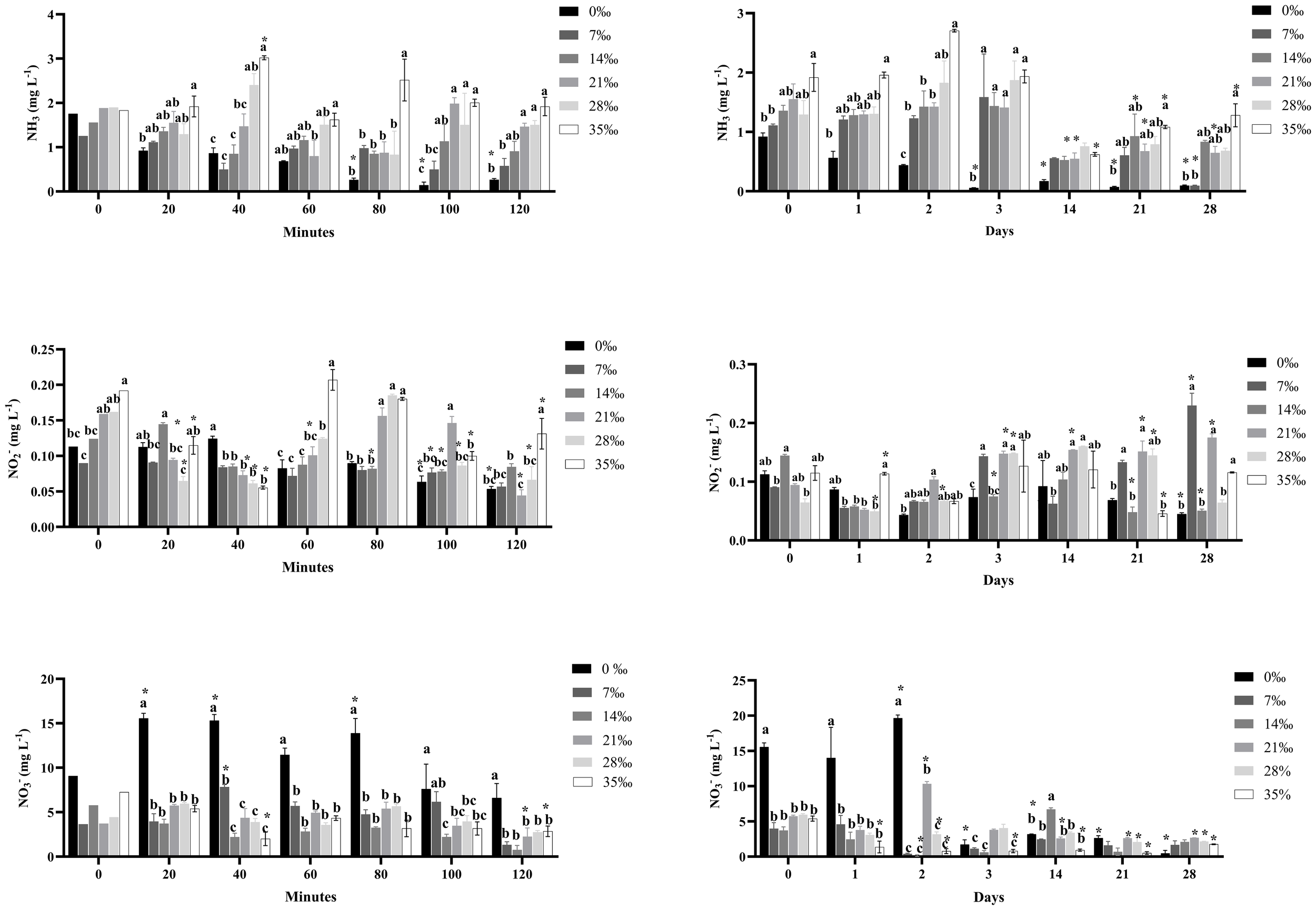

There were acute and chronic significant differences (p < 0.05) in nitrogen compound concentrations among salinity levels (0‰, 7‰, 14‰, 21‰, 28‰ and 35‰) during the experimental period. Within 120 minutes, a significant decrease in ammonia was observed in the 0‰ and 7‰ salinity treatments, followed by 14‰. Treatments with 21‰, 28‰ and 35‰ showed higher concentrations, indicating lower ammonia reduction.

During the chronic phase, ammonia decreased significantly in the 0‰ salinity treatment (0.55 mg L-¹), remaining low and relatively stable over 28 days (0.08, 0.09, and 0.8 mg L-¹). A marked reduction was also observed on day 28 in the 7‰ salinity treatment. Intermediate values were recorded at 14‰, 21‰ and 28‰. The highest ammonia concentration was found in the 35‰ salinity treatment throughout the trial. Overall, a decline in ammonia concentration was seen in all treatments after the third day, indicating conversion into nitrite and nitrate.

As for nitrite (NO2-), in the acute phase, fluctuations were observed among salinities over the 120 minutes. Nitrite peaked at 0‰ at 40 minutes, at 14‰ at 20 minutes, at 21‰ at 100 minutes, and at 28‰ at 80 minutes. Meanwhile, at 35‰, nitrite was higher at 0, 60, 80 and 120 minutes.

Similarly, during the chronic phase, nitrite concentrations varied among salinities. The 7‰ treatment showed higher nitrite levels on days 3, 21 and 28; 14‰ peaked on day 0; 21‰ on days 2, 14, 21 and 28; 28‰ on day 14; and 35‰ on days 1, 7 and 28, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Effect of açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea) as biological media under different salinities on nitrogen compound concentrations during acute (minutes) and chronic (days) periods of experimentation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among groups according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

The 0‰ salinity treatment exhibited the highest nitrate (NO3-) concentration compared to other treatments during the 120-minute acute period, as well as in the early days of the chronic phase. However, from day 3 onward, nitrate decreased significantly in the 0‰ treatment and remained low throughout the 28-day trial. On day 14, the 14‰ treatment had the highest nitrate concentration among treatments. Overall, nitrate concentrations on days 21 and 28 were lower in all treatments compared to day 1 (Figure 3).

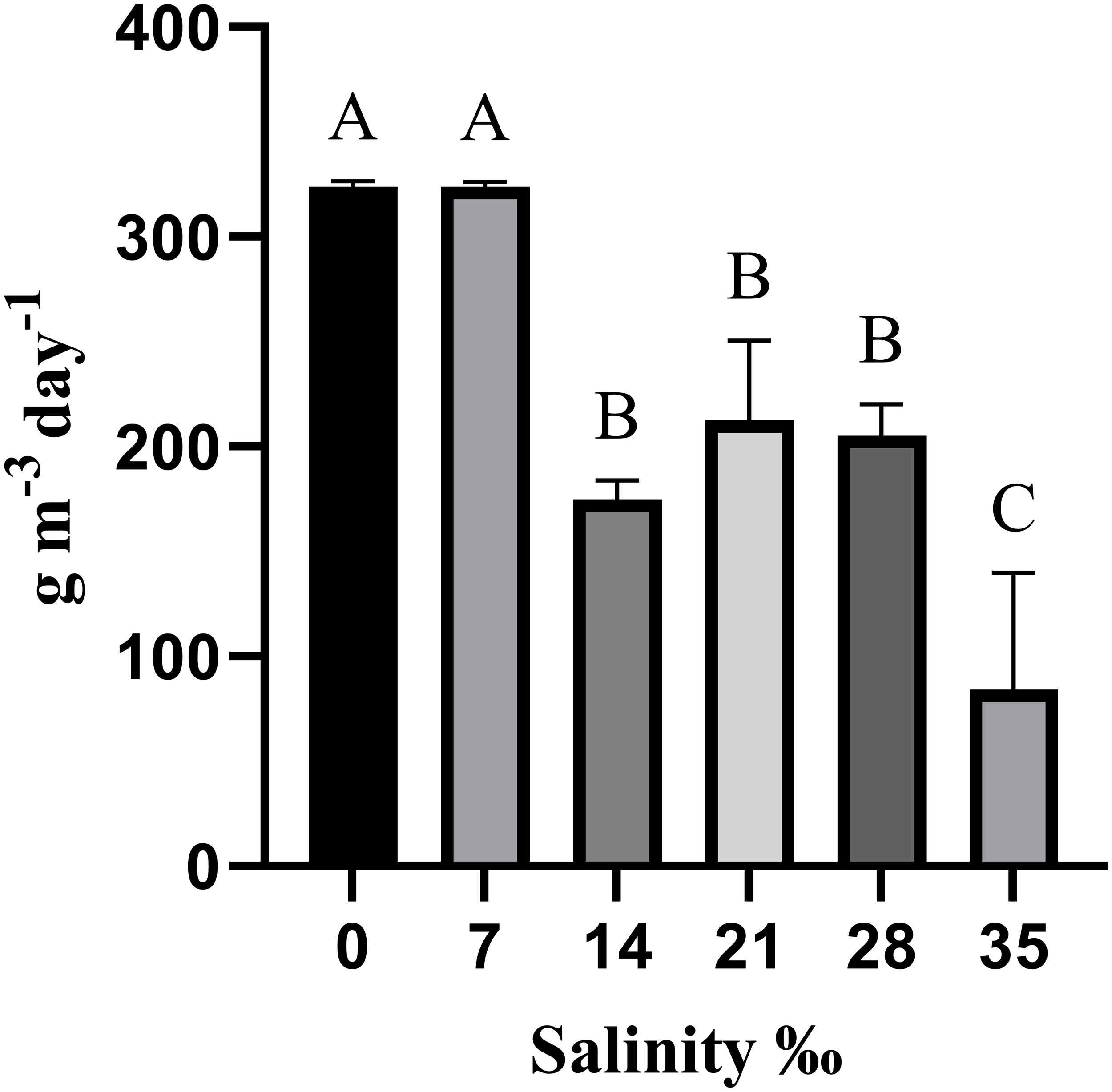

3.3 Ammonia clearance

The treatments with salinities of 0‰ and 7‰ achieved the highest ammonia removal rates (323.7 g day-¹ m-³ for both). However, the treatment with a salinity of 35‰ showed the lowest rate, only 45.08 g day-¹ m-³, while the treatments with salinities of 14‰, 21‰ and 28‰ showed intermediate rates of 172.2, 212.4 and 203.5 g day-¹ m-³, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Ammonia clearance by açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea) as a biological medium under different salinities after 28 days of experimentation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among groups according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

4 Discussion

4.1 Physicochemical parameters of water

The physical-chemical change in water quality indicates microorganism activity in our study. The chemoautotrophic nitrification carried out by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) reduces dissolved oxygen concentrations and water pH, while denitrification bacteria increase pH (Jianlong and Ning, 2004; Preena et al., 2021). The higher dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration found at the inlet of the biological filter compared to the outlet indicates nitrification activity at all salinities. When comparing DO among salinities, a lower concentration was found at both the inlet and outlet in the 0‰ condition, possibly due to more intense nitrification in freshwater compared to saline conditions. Previous studies on salt effects on nitrification bacteria showed lower activity after increasing salinity (Aslan and Simsek, 2012b; Costigan et al., 2024). Although DO concentrations below 2 mg L-¹ can inhibit nitrification (Prinčič et al., 1998), in our study, DO levels ranged between 2 and 6 mg L-¹, remaining within the effective range for nitrification.

Water salinity had no significant influence on pH at the inlet or outlet of the biofilter, although pH tended to be lower at the outlet in the 0‰ and 7‰ salinity treatments. During the nitrification process, which occurs in the presence of oxygen, H+ ions are released during the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite and nitrate. The increase in the concentration of this ion in the water leads to medium acidification. On the other hand, in denitrification, nitrate undergoes a reduction process in the absence of oxygen, ultimately generating nitrogen gas (N2). During the reduction process, H+ is consumed, resulting in the production of bicarbonate (HCO3-), which raises the pH of the medium (Ebeling et al., 2006; van Rijn et al., 2006). The absence of significant pH variation in our study indicates the establishment of a nitrifying and denitrifying microbial population at all salinities. Studies showed that nitrification and denitrification could occur simultaneously in a single reactor with the combination of anoxic and aerated zones (She et al., 2016).

4.2 Nitrogen compounds

Nitrifying bacteria are sensitive to variations in water salinity, which can disrupt osmoregulation and impair nitrification, resulting in elevated TAN levels in RAS under different salinity conditions (Rud et al., 2017; Fossmark et al., 2021). This sensitivity may explain our findings after acute change, which show that higher TAN levels at salinities above 7‰. However, during the chronic evaluation, a reduction in TAN was seen in all treatments after the third day. Previous studies (Kinyage et al., 2019; Navada et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023) have reported increased nitrification efficiency following a bacterial adaptation period to salinity, demonstrating the nitrifying bacterial community's capacity to adjust to environmental changes in the long term.

In general, in our study, ammonia was consumed in all treatments in different proportions according to the water salinity, both in the acute and chronic periods. This demonstrates the ability of açaí seeds to promote water nitrification within a short period of time. It is likely that the characteristics of the seeds, such as their lamellar fiber structure, which resembles filaments after pulp extraction, make them a highly effective medium for the attachment of nitrifying bacteria. Paul and Hall (2021) evaluated the characteristics of some alternative biofiltration media and found, through surface profilometry and electron microscopy, that zeolite and biochar exhibited a rougher surface than plastic media, resulting in greater bacterial adhesion and enhanced water nitrification. Although not assessed in our study, the roughness of açaí seed fibers could also be a determining factor in the nitrification efficiency observed in the trials.

Nitrite, an intermediate product in TAN-to-nitrate nitrification, is also toxic to aquatic organisms at high concentrations. It can interfere with oxygen transport in fish blood (Preena et al., 2021) and is more readily oxidized than TAN. In our study, nitrite concentrations varied throughout the acute and chronic phases, with alternating peaks across treatments. Notable spikes were observed in the 35‰ treatment during the acute phase, and in the 21‰ and 35‰ treatments during the chronic phase. These results suggest lower nitrite oxidation efficiency by NOB in high-salinity water. Therefore, the development of more effective biofilters is crucial to promoting healthy bacterial communities, especially considering that nitrifying microorganisms are sensitive to environmental parameters such as salinity, which is often adjusted in production systems to meet the physiological needs of cultured species (Kinyage et al., 2019).

Nitrate is the final element generated by nitrification in the presence of oxygen from ammonia. However, the removal of nitrogen from the environment occurs through denitrification, under oxygen-depleted conditions, in which nitrate is reduced to nitrogen gas (N2) or nitrous oxide (N2O) (Wongkiew et al., 2017), a potent greenhouse gas. The bacteria responsible for these processes belong to the group of Archaea and facultative heterotrophic bacteria (Hargreaves, 1998; Michaud et al., 2006; Gentile et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2014). In the acute phase of our study, the 0‰ salinity treatment had higher nitrate concentrations compared to the other treatments, as also observed during the first two days of the chronic phase. This may be explained by the higher nitrification rate in this treatment, leading to nitrate accumulation. From the third day onward, however, nitrate levels dropped significantly in the 0‰ treatment, and from day 21, nitrate concentrations decreased in all treatments compared to those observed at the beginning of the chronic phase. It is likely that areas with low dissolved oxygen concentration—especially at the aquarium edges due to the rectangular shape—favored the proliferation of anaerobic heterotrophic bacteria, which denitrified the nitrate with varying efficiency depending on water salinity. Some studies have demonstrated effective nitrate removal strategies in RAS, such as the use of anoxic reactors to promote denitrification (Klas et al., 2006; Torno et al., 2018; Stavrakidis-Zachou et al., 2019; Ernst et al., 2024).

4.3 Ammonia clearance

The efficiency of ammonia clearance by nitrifying bacteria in RAS can be affected by various factors, such as water temperature (Kinyage and Pedersen, 2016), pH, alkalinity, dissolved oxygen, TAN concentration, organic carbon proportion (Prinčič et al., 1998; Jianlong and Ning, 2004; Michaud et al., 2006; Summerfelt et al., 2015; Jafari et al., 2024), salinity (Ilgrande et al., 2018; Kinyage et al., 2019; Navada et al., 2019), types of biofilm media and variation in microbial population (Lekang and Kleppe, 2000; Owatari et al., 2018; Jose et al., 2020; Wafula et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023; Mnyoro et al., 2024). Normally, nitrifying bacteria take an average of 28 days to proliferate in biological filter media to efficiently nitrify the water in RAS. However, açaí seeds possibly carried a preexisting microbial load sufficient to acutely nitrify the water, as observed in the freshwater treatments of our study after the acute period, increasing the efficiency in the long term.

In general, in our study, over 28 days of observation, the treatments with salinities of 0‰ and 7‰ showed higher efficiency in ammonia clearance, whereas the treatment with 35‰ salinity was the least efficient, with an approximate 86% reduction in nitrification rate. The detrimental effect of salinity on nitrifying bacterial activity was further evaluated by Ilgrande et al. (2018), who reported a decrease in TAN oxidation and alterations in cellular metabolism, such as changes in nitrogen and carbon cycles, as well as the production of intracellular solutes to maintain bacterial osmotic balance under high salinity. On the other hand, in our study, there was a recovery of nitrification efficiency in the long term, which may indicate microbial adaptation to environmental changes. Although these adaptations are essential for microbial survival under environmental shifts, they may increase energy expenditure, thereby compromising nitrification efficiency. Therefore, physiological and structural aspects of the microbial community should be considered when assessing the impact of salinity on the biological filtration mechanism in an RAS.

Sterzelecki et al. (2022) demonstrated the efficacy of açaí seeds as a culture medium for biofiltration in freshwater, achieving a 74 to 95% reduction in ammonia in 28 days and bringing the concentration to values below 1 mg L-¹, in part due to the adsorption capacity of the organic substrate. Other biological filters, such as the moving bed reactor, reached removal of 267 g of total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) per m³ day-1, and the Floating Spheres reach 667 g of TAN per m³ day-1 (Guerdat et al., 2010), whose efficiency can be impacted by factors such as high fish density (Roalkvam et al., 2021). The use of algae in integrated marine aquaculture systems has also been shown to be efficient, with species such as Gracilaria and Ulva showing removal rates of 0.42 to 0.45 g of TAN per m² day-1, and achieving an efficiency of up to 83.06% (Al-Hafedh et al., 2012). Despite the predominance of fixed film filters in low-cost systems, their application in more complex contexts, such as marine larviculture, is limited by the high management requirements and the need to optimize denitrification (Gutierrez-Wing and Malone, 2006). In the long term, the ammonia clearance decreased seven times in our study when salinity was increased from 0‰ to 35‰, from 323.67 g m-³ day-¹ to 45.08 g m-³ day-¹. This finding corroborates previous results that showed a negative impact on the nitrification capacity of biofilters (Aslan and Simsek, 2012; Costigan et al., 2024).

5 Conclusion

Açaí seeds exhibited nitrification capacity in both the acute and chronic periods, which may indicate that the seeds can naturally harbor bacteria with the potential to nitrify water. However, a decrease in nitrification efficiency was observed in seeds exposed to salinities above 7‰, with up to a sevenfold reduction in efficiency in the 35‰ salinity treatment. On the other hand, higher salinities did not completely prevent ammonia removal in the long term, demonstrating the potential of açaí seeds as biological media for wastewater treatment in intensive marine aquaculture.

To optimize the use of açaí seeds as a biofilter medium, further studies are required to identify the resident bacterial species and to assess the microbial community's performance across a range of ammonia and salinity conditions. The results will be critical for informing future water quality and economic analyses under commercial-scale Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) production in the marine environment.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DC: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. BE: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JP: Investigation, Writing – original draft. AR: Investigation, Writing – original draft. HB: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GP: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. NM: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JM: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. FS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The author, DC thanks The Amazon Foundation for Support of Studies and Research of Pará (FAPESPA) and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for granting the scholarship (88887.149844/2025-00).

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank the VeroSal Corais (Veromar, Campinas, SP, Brazil), Amazonian Aquatic Biosystems Laboratory (BIOAQUAM), the Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory (LAqTrop), and the Tropical Aquatic Ecology Laboratory (LECAT) for providing infrastructure support for the experimental trials.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Al-Hafedh Y. S. Alam A. Buschmann A. H. Fitzsimmons K. M. (2012). Experiments on an integrated aquaculture system (seaweeds and marine fish) on the Red Sea coast of Saudi Arabia: Efficiency comparison of two local seaweed species for nutrient biofiltration and production. Rev. Aquac4, 21–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-5131.2012.01057.x

2

Araujo-Lima C. A. R. M. Ruffino M. L. (2003). “ Migratory fishes of the Brazilian Amazon,” in Migratory fishes of South America: Biology, fisheries and conservation status. Eds. CarolsfeldJ.HarveyB.RossC.BaerA. ( IDRC, World Bank, Washington, DC), 233–302.

3

Aslan S. Simsek E. (2012). Influence of salinity on partial nitrification in a submerged biofilter. Bioresour Technol.118, 24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.05.057

4

Bolleter W. T. Bushman C. J. Tidwell P. W. (1961). Spectrophotometric determination of ammonia as indophenol. Anal. Chem.33, 592–594. doi: 10.1021/ac60172a034

5

Castello L. McGrath D. G. Hess L. L. Coe M. T. Lefebvre P. A. Petry P. et al . (2013). The vulnerability of Amazon freshwater ecosystems. Conserv. Lett.6, 217–229. doi: 10.1111/conl.12008

6

Costigan E. M. Bouchard D. A. Ishaq S. L. MacRae J. D. (2024). Short-term effects of abrupt salinity changes on aquaculture biofilter performance and microbial communities. Water16, 2911. doi: 10.3390/w16202911

7

da Costa J. A. S. Sterzelecki F. C. Natividade J. Souza R. J. F. de Carvalho T. C. C. de Melo N. F. A. C. et al . (2022). Residue from açai palm, Euterpe oleracea, as substrate for cilantro, Coriandrum sativum, seedling production in an aquaponic system with tambaqui, Colossoma macropomum. Agriculture12, 1555. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12101555

8

de Lima A. C. P. Bastos D. L. R. Camarena M. A. Bon E. P. S. Cammarota M. C. Teixeira R. S. S. et al . (2021). Physicochemical characterization of residual biomass (seed and fiber) from açaí (Euterpe oleracea) processing and assessment of the potential for energy production and bioproducts. Biomass Convers Biorefin11, 925–935. doi: 10.1007/s13399-019-00551-w

9

de Oliveira M. S. P. Schwartz G. (2018). “ Açaí—Euterpe oleracea,” in Exotic Fruits Reference Guide. Eds. RodriguesS.SilvaE. O.BritoE.S.d ( Academic Press, Oxford, UK), 1–5. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-803138-4.00002-2

10

Ebeling J. M. Timmons M. B. Bisogni J. J. (2006). Engineering analysis of the stoichiometry of photoautotrophic, autotrophic, and heterotrophic removal of ammonia-nitrogen in aquaculture systems. Aquaculture257, 346–358. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.03.019

11

Ernst A. Steinbach C. Wagner K. Waller U. (2024). Virtual sensing of nitrite: A novel control for safe denitrification in recirculating aquaculture systems (RASs). Fishes9, 398. doi: 10.3390/fishes9100398

12

Fossmark R. O. Attramadal K. J. K. Nordøy K. Østerhus S. W. Vadstein O. (2021). A comparison of two seawater adaptation strategies for Atlantic salmon post-smolt (Salmo salar) grown in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS): Nitrification, water and gut microbiota, and performance of fish. Aquaculture532, 735973. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735973

13

Gentile M. E. Lynn Nyman J. Criddle C. S. (2007). Correlation of patterns of denitrification instability in replicated bioreactor communities with shifts in the relative abundance and the denitrification patterns of specific populations. ISME J.1, 714–728. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.87

14

Gerhardinger L. C. Gorris P. Gonçalves L. R. Herbst D. F. Vila-Nova D. A. de Carvalho F. G. et al . (2018). Healing Brazil’s Blue Amazon: The role of knowledge networks in nurturing cross-scale transformations at the frontlines of ocean sustainability. Front. Mar. Sci.4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00395

15

Guerdat T. C. Losordo T. M. Classen J. J. Osborne J. A. DeLong D. P. (2010). An evaluation of commercially available biological filters for recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac Eng.42, 38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2009.10.002

16

Gutierrez-Wing M. T. Malone R. F. (2006). Biological filters in aquaculture: Trends and research directions for freshwater and marine applications. Aquac Eng.34, 163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2005.08.003

17

Hargreaves J. A. (1998). Nitrogen biogeochemistry of aquaculture ponds. Aquaculture166, 181–212. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(98)00298-1

18

Hilsdorf A. W. S. Hallerman E. Valladão G. M. R. Zaminhan-Hassemer M. Hashimoto D. T. Dairiki J. K. et al . (2022). The farming and husbandry of Colossoma macropomum: From Amazonian waters to sustainable production. Rev. Aquac14, 993–1027. doi: 10.1111/raq.12638

19

IBGE (2024). Produção da Pecuária Municipal 2023 (Rio de Janeiro). Available online at: https://www.gov.br/mpa/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/ppm_2023_v51_br_informativo.pdf (Accessed March 8, 2025).

20

Ilgrande C. Leroy B. Wattiez R. Vlaeminck S. E. Boon N. Clauwaert P. (2018). Metabolic and proteomic responses to salinity in synthetic nitrifying communities of Nitrosomonas spp. and Nitrobacter spp. Front. Microbiol.9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02914

21

Jafari L. Montjouridès M. A. Hosfeld C. D. Attramadal K. Fivelstad S. Dahle H. (2024). Biofilter and degasser performance at different alkalinity levels in a brackish water pilot scale recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) for post-smolt Atlantic salmon. Aquac Eng.106, 102407. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2024.102407

22

Jianlong W. Ning Y. (2004). Partial nitrification under limited dissolved oxygen conditions. Process Biochem.39, 1223–1229. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00249-8

23

Jose D. Preena P. G. Kumar V. J. R. Philip R. Singh I. S. B. (2020). Metaproteomic insights into ammonia oxidising bacterial consortium developed for bioaugmenting nitrification in aquaculture systems. Biologia75, 1751–1757. doi: 10.2478/s11756-020-00481-3

24

Kinyage J. P. H. Pedersen L. F. (2016). Impact of temperature on ammonium and nitrite removal rates in RAS moving bed biofilters. Aquac Eng.75, 51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2016.10.006

25

Kinyage J. P. H. Pedersen P. B. Pedersen L. F. (2019). Effects of abrupt salinity increase on nitrification processes in a freshwater moving bed biofilter. Aquac Eng.84, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2018.12.005

26

Klas S. Mozes N. Lahav O. (2006). Development of a single-sludge denitrification method for nitrate removal from RAS effluents: Lab-scale results vs. model prediction. Aquaculture259, 342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.05.049

27

Lekang O. I. Kleppe H. (2000). Efficiency of nitrification in trickling filters using different filter media. Aquac Eng.21, 181–199. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8609(99)00032-1

28

Lipps W. C. Braun-Howland E. B. Baxter T. E. (2023). Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 24th Edn (Washington DC: American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation).

29

Lu H. Chandran K. Stensel D. (2014). Microbial ecology of denitrification in biological wastewater treatment. Water Res.64, 237–254. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.06.042

30

Marques V. S. Vieira J. S. O. Alves A. P. de Oliveira J. A. V. Costa N. S. P. Lopes T. S. et al . (2024). Use of eggshell as an alternative substrate for biofilters in recirculation aquaculture systems. DELOS17, 01–24. doi: 10.55905/rdelosv17.n55-001

31

Michaud L. Blancheton J. P. Bruni V. Piedrahita R. (2006). Effect of particulate organic carbon on heterotrophic bacterial populations and nitrification efficiency in biological filters. Aquac Eng.34, 224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2005.07.005

32

Mnyoro M. S. Munubi R. N. Chenyambuga S. W. Pedersen L. F. (2024). Comparison of four different types of biomedia during start-up in a recirculating aquaculture system with rainbow trout. J. Water Process Eng.68, 106549. doi: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106549

33

Nascimento E. T. S. Pereira Junior R. F. dos Reis V. S. Gomes B. J. F. Owatari M. S. Luz R. K. et al . (2023). Production of late seedlings of açai (Euterpe oleraceae) in an aquaponic system with tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum, Curvier 1818). Agriculture13, 1581. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13081581

34

Navada S. Vadstein O. Tveten A. K. Verstege G. C. Terjesen B. F. Mota V. C. et al . (2019). Influence of rate of salinity increase on nitrifying biofilms. J. Clean Prod238, 117835. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117835

35

Owatari M. S. Jesus G. F. A. de Melo Filho M. E. S. Lapa K. R. Martins M. L. Mouriño J. L. P. (2018). Synthetic fibre as biological support in freshwater recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). Aquac Eng.82, 56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2018.06.001

36

Pacheco F. S. Heilpern S. A. DiLeo C. Almeida R. M. Sethi S. A. Miranda M. et al . (2025). Towards sustainable aquaculture in the Amazon. Nat. Sustain8, 234–244. doi: 10.1038/s41893-024-01500-w

37

Paul D. Hall S. G. (2021). Biochar and zeolite as alternative biofilter media for denitrification of aquaculture effluents. Water13, 2703. doi: 10.3390/w13192703

38

Peixe B. R. (2024). Anuário 2024 ( Associação Brasileira de Piscicultura). Available online at: https://www.peixebr.com.br/anuario-2024/ (Accessed March 31, 2024).

39

Preena P. G. Rejish Kumar V. J. Singh I. S. B. (2021). Nitrification and denitrification in recirculating aquaculture systems: the processes and players. Rev. Aquac13, 2053–2075. doi: 10.1111/raq.12558

40

Pretty J. Sutherland W. J. Ashby J. Auburn J. Baulcombe D. Bell M. et al . (2010). The top 100 questions of importance to the future of global agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Sustain8, 219–236. doi: 10.3763/ijas.2010.0534

41

Prinčič A. Mahne I. Megušar F. Paul E. A. Tiedje J. M. (1998). Effects of pH and oxygen and ammonium concentrations on the community structure of nitrifying bacteria from wastewater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.64, 3584–3590. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.10.3584-3590.1998

42

Roalkvam I. Drønen K. Dahle H. Wergeland H. I. (2021). A case study of biofilter activation and microbial nitrification in a marine recirculation aquaculture system for rearing Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquac Res.52, 94–104. doi: 10.1111/are.14872

43

Rodrigues A. P. O. de Freitas L. E. L. Maciel-Honda P. O. Lima A. F. de Lima L. K. F. (2024). Feeding rate and feeding frequency during the grow-out phase of tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) in earthen ponds. Aquac Rep.35, 102000. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102000

44

Rud I. Kolarevic J. Holan A. B. Berget I. Calabrese S. Terjesen B. F. (2017). Deep-sequencing of the bacterial microbiota in commercial-scale recirculating and semi-closed aquaculture systems for Atlantic salmon post-smolt production. Aquac Eng.78, 50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2016.10.003

45

Ruiz P. Vidal J. M. Sepúlveda D. Torres C. Villouta G. Carrasco C. et al . (2020). Overview and future perspectives of nitrifying bacteria on biofilters for recirculating aquaculture systems. Rev. Aquac12, 1478–1494. doi: 10.1111/raq.12392

46

Saliling W. J. B. Westerman P. W. Losordo T. M. (2007). Wood chips and wheat straw as alternative biofilter media for denitrification reactors treating aquaculture and other wastewaters with high nitrate concentrations. Aquac Eng.37, 222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2007.06.003

47

She Z. L. Zhang X. L. Gao M. Guo Y. C. Zhao L. T. Zhao Y. G. (2016). Effect of salinity on nitrogen removal by simultaneous nitrification and denitrification in a sequencing batch biofilm reactor. Desalin Water Treat57, 7378–7386. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2015.1016459

48

Stavrakidis-Zachou O. Ernst A. Steinbach C. Wagner K. Waller U. (2019). Development of denitrification in semi-automated moving bed biofilm reactors operated in a marine recirculating aquaculture system. Aquac Int.27, 1485–1501. doi: 10.1007/s10499-019-00402-5

49

Sterzelecki F. C. de Jesus A. M. Jorge J. L. C. Tavares C. M. de Souza A. J. N. Souza Santos M. L. et al . (2022). Açai palm, Euterpe oleracea, seed for aquaponic media and seedling production. Aquac Eng.98, 102270. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2022.102270

50

Summerfelt S. T. Zühlke A. Kolarevic J. Reiten B. K. M. Selset R. Gutierrez X. et al . (2015). Effects of alkalinity on ammonia removal, carbon dioxide stripping, and system pH in semi-commercial scale water recirculating aquaculture systems operated with moving bed bioreactors. Aquac Eng.65, 46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2014.11.002

51

Timmons M. B. Vinci B. J. (2022). Recirculating Aquaculture. 5th Edn (Florida, USA: Ithaca Publishing Company LLC).

52

Torno J. Naas C. Schroeder J. P. Schulz C. (2018). Impact of hydraulic retention time, backflushing intervals, and C/N ratio on the SID-reactor denitrification performance in marine RAS. Aquaculture496, 112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.07.004

53

Valladão G. M. R. Gallani S. U. Pilarski F. (2018). South American fish for continental aquaculture. Rev. Aquac10, 351–369. doi: 10.1111/raq.12164

54

van Rijn J. Tal Y. Schreier H. J. (2006). Denitrification in recirculating systems: Theory and applications. Aquac Eng.34, 364–376. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2005.04.004

55

Wafula E. A. Gichana Z. Onchieku J. Chepkirui M. Orina P. S. (2023). Opportunities and challenges of alternative local biofilter media in recirculating aquaculture systems. JATEMS1, 73–83. doi: 10.69897/jatems.v1i1.24

56

Wongkiew S. Hu Z. Chandran K. Lee J. W. Khanal S. K. (2017). Nitrogen transformations in aquaponic systems: A review. Aquac Eng.76, 9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2017.01.004

57

Zhang W. Liu B. Sun Z. Wang T. Tan S. Fan X. et al . (2023). Comparision of nitrogen removal characteristic and microbial community in freshwater and marine recirculating aquaculture systems. Sci. Total Environ.878, 162870. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162870

Summary

Keywords

aquaculture, salinity, water quality, biofilter, RAS

Citation

da Costa DL, Eiras BJCF, Pereira JDdS, Rodrigues ACR, Barros HLB, Palheta GDA, de Melo NFAC, Santos MdLS, Matias JFN and Sterzelecki FC (2026) Acute and chronic effects of salinity on nitrification in a recirculating aquaculture system with açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea) as biological media. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1704819. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1704819

Received

13 September 2025

Revised

11 November 2025

Accepted

26 November 2025

Published

02 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Kumbukani Mzengereza, Mzuzu University, Malawi

Reviewed by

Benjamin Vallejo, University of the Philippines Diliman, Philippines

Zhenlu Wang, Guizhou University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 da Costa, Eiras, Pereira, Rodrigues, Barros, Palheta, de Melo, Santos, Matias and Sterzelecki.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fabio Carneiro Sterzelecki, fabio.sterzelecki@ufra.edu.br

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.