- 1Centre for Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), Lowestoft, United Kingdom

- 2HalieuMer, Arzon, France

- 3Ascension Island Government Conservation and Fisheries Directorate, Georgetown, Ascension Island, South Atlantic Ocean, United Kingdom

- 4Environment and Natural Resources Directorate, St Helena Government, Jamestown, Saint Helena

- 5Fish Aging Services Pty Ltd, Queenscliff, VIC, Australia

This study investigates the age-based life-history traits of two groundfish species, the spotted moray eel (Gymnothorax moringa) and squirrelfish (Holocentrus adscensionis), found in Ascension Island and St Helena. Both islands are part of the UK Overseas Territories (UKOTs) and are known for their fish biodiversity. The research aims to provide essential life-history information to support sustainable management of these species within the Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) of Ascension Island and St Helena. A total of 556 fish samples were collected between 2014 and 2021, with 279 individuals of G. moringa and 277 individuals of H. adscensionis. We found significant differences in life span, adult body size, and growth rates between the two islands for both species. G. moringa exhibited longer life spans (32 vs 29 years) and faster growth rates at Ascension Island compared to St Helena, while H. adscensionis showed larger adult sizes at Ascension Island but shorter life spans (21 vs 27 years) compared to St Helena. The study highlights the importance of developing locality-specific species life history data collections to monitor population dynamics in MPA areas. This biological information is essential to allow future assessment programs on the potential impacts of climate change and inshore human activities, including the impacts of inshore fisheries. Future research should focus on reproductive biology, size and age at maturity, and migration patterns to enhance the accuracy of sustainability assessments for these fisheries.

Introduction

Ascension Island and St Helena are isolated islands in the tropical South Atlantic. Both are hotspots of pelagic biodiversity, which attracts high abundances of commercially important fish species within their Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Both are part of the UK Overseas Territories (UKOTs), which are collectively responsible for around 90% of the UK’s biodiversity and include a number of endemic and endangered species. The Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) of the UKOTs currently cover over 1% of the world’s oceans and play an important role in safeguarding marine environments around the world (Marine Conservation Institute, 2025). In 2019, the Ascension Island Council designated a large Marine Protected Area (MPA), covering its entire EEZ of around 445,000 km2. The St Helena MPA, designated by St Helena Government in September 2016, encompasses the island’s entire EEZ and territorial sea of around 448,000km2. Excepting a small amount of inshore recreational fishing, the Ascension MPA is fully no-take, whereas the St Helena MPA is a Category VI ‘Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources’, following International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) descriptions (Day et al., 2019). Sustainable, low-impact, human use of marine resources is permitted, provided it does not undermine the MPA’s objectives. As such, only one-by-one fishing methods are permitted within the St Helena MPA (handlines, pole-and-line, pots, by hand, spear gun) (St Helena Marine Management Plan, 2023). Other human activities (marine tourism and marine development activities) are only permitted if they are compatible with the goals and objectives of the St Helena Marine Management Plan.

In addition to highly migratory pelagic species (e.g. Thunnus albacares yellowfin tuna, Thunnus obesus bigeye tuna, and Acanthocybium solandri wahoo), Ascension Island and St Helena host a range of inshore fish species that can be found around each island and some of the larger seamounts. Around Ascension Island, the only fishing still permitted is recreational (shore- or boat-based) which targets mainly rockhind grouper, moray eel, and glasseye snapper, and other species including squirrelfish. In St Helena, fishing pressure inshore is largely commercial, targeting yellowfin, wahoo, and grouper, amongst other species. Recently, an Inshore Fisheries Management Strategy in Ascension Island (2023) and a Fisheries Ordinance (2021) in St Helena have been proposed to secure social, economic and environmental objectives. Consultation with local communities highlighted that data and information regarding stock status and species life history is lacking for several targeted species.

Life-history parameters for many demersal reef fish populations around Ascension Island are often based on data collected from St Helena, meaning that Ascension Island fisheries are considered to be data-poor or data-limited. It has been demonstrated that life history parameters (growth rates, body size, life span, maturation rates, etc.) vary within species across a range of geographical scales, including on localized scales as a result of locality-specific environmental impacts (e.g. Pears et al., 2006; Caselle et al., 2011; Hamilton et al., 2011; Berumen et al., 2012; Trip et al., 2008; Visconti et al., 2020). These intraspecific variations in life history traits place constraints upon the reproductive potential of a given fish stock, with clear implications for effective fisheries management of these fisheries (Hawkins and Roberts, 2004; Hamilton et al., 2007). It is important to build relevant locality-specific data for use in stock assessments for the two locations separately, including for example, catch levels, a timeseries of abundance, and biology (i.e. age/size distribution, and/or sex ratio).

This study aims to provide missing age-based life-history information for the sustainable management of two local ground fishery species, which both occur across Ascension Island and St Helena, these being the spotted moray eel Gymnothorax moringa and squirrelfish Holocentrus adscensionis. Historical catch data on groundfish species from St Helena show stable trends for both G. moringa and H. adscensionis, with no significant changes across years (Edwards 1990; St Helena Marine Management Plan, 2023). On the other hand, catch data for Ascension Island is very limited, with the main focus being only on big pelagic species and grouper. A data collection program was established to support sustainability assessments of these two exploited fish species. Age-based data was collected to (i) establish baseline life-history information for G. moringa and H. adscensionis, and (ii) describe differences within each of the two species across Ascension Island and St Helena, to provide an evidence base for fishery management decisions as required under the objectives of each MPA’s Management Plans and associated strategies for both Ascension and St Helena islands.

Materials and methods

Ascension Island sampling

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island located at 7°56′S 14°25′W, surrounded by a narrow band of shallow water habitat due to the steep sides of the volcano. Ascension Island’s coastal habitat includes rocky volcanic reef, boulder field, sand and rhodolith beds, and the sea surface temperature is relatively constant across seasons, between 22°C and 29°C all year round. The entire island experiences the strong currents and heavy swells from the Atlantic South Equatorial Current, with the north-western side being the comparatively more sheltered part of the island. Fishing for moray eel and squirrelfish most commonly occurs around the north-western side of the island from small recreational boats or from the rocks where there are accessible areas along the coastline. Gear types include rod and reel, handline and spearfishing. Eels are also often caught along the coastline by baiting them into shallow rock pools (Edwards 1990; St Helena Marine Management Plan, 2023).

St Helena sampling

St Helena is an isolated oceanic island in the south Atlantic located at 15.96°S, 5.70°W with a rapid drop-off in bottom depth resulting in a narrow continental shelf. Sea surface temperatures in St Helena are warmest in March (median = 25.6˚C) and coolest in October (median = 20.2˚C), with large-scale temperature changes across the EEZ over the course of a year and warmest temperatures in the north of the EEZ. Commercial fishing for both species occurs all-round St Helena, though more typically on the leeward (western) side of the island. St Helena experiences moderate wind speeds over the year with slightly higher winds during the winter months and during spring months. In terms of current speed, there is a moderate East-West surface current with low variation across the year.

Sample collection

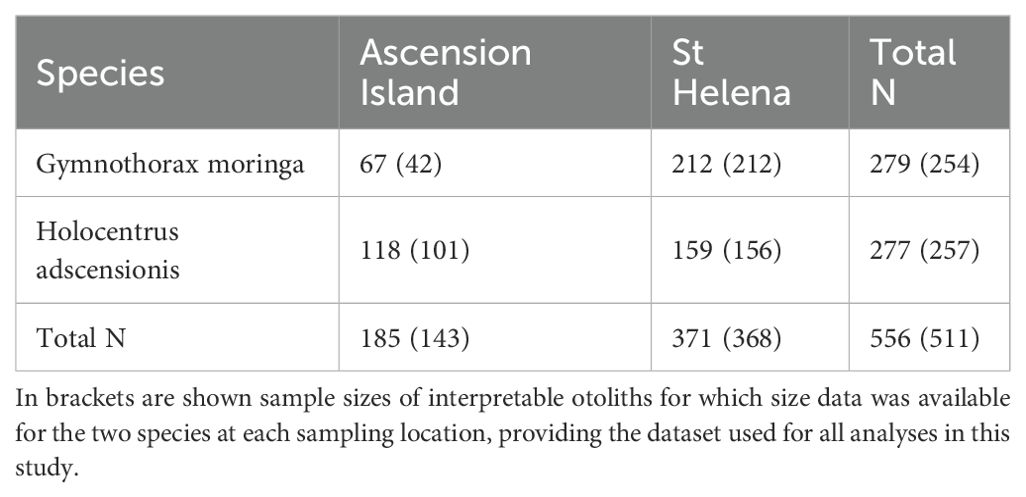

A total of 279 moray eel G. moringa and 277 squirrelfish H. adscensionis were collected from St Helena and Ascension Island (total of 556 fish) (Table 1). All fish were collected between 2014 and 2021 during surveys, from periodic pierhead sampling, fishing competitions and research activities using handline (8–12 hooks) and droppers. All fish were collected as part of catch sampling programs conducted by the Governments of Ascension and St Helena. (Figure 1). For each individual fish collected, total length (moray eels) and fork length (squirrelfish) was measured to the nearest centimeter, and sagittal otoliths were dissected out and stored in envelopes or vials before processing.

Table 1. Sample sizes of fish collected for moray eel G. moringa and squirrelfish H. adscensionis at Ascension Island and St Helena.

Figure 1. Map of both Ascension Island and St Helena showing the bathymetry of each island and their relative position within the South Atlantic Ocean.

Otolith preparation and age determination

For each fish sampled, both sagittal otoliths were extracted and preserved dry or in ethanol. Otoliths of G. moringa were mounted in specifically prepared molds and covered with black polyester resin left to cure overnight. Transverse sections of otoliths were prepared following Bedford (1983) with some adjustments. The otoliths were sectioned on a high or low speed saw, with sections to varying thicknesses from 250μm to 450μm. Strips were mounted on glass slides with up to 4 strips per slide and covered with a clear epoxy resin and a glass cover slip. On the other hand, H. adscensionis otoliths were prepared according to Robbins and Choat (2002) and Visconti et al. (2018) with some modifications. Each otolith was mounted on a glass slide with thermoplastic cement (Crystalbond 509) and subsequently ground from the posterior and anterior margins to obtain a thin transverse section through the nucleus using a diamond polish wheel with P1200-grade wet and dry sandpaper.

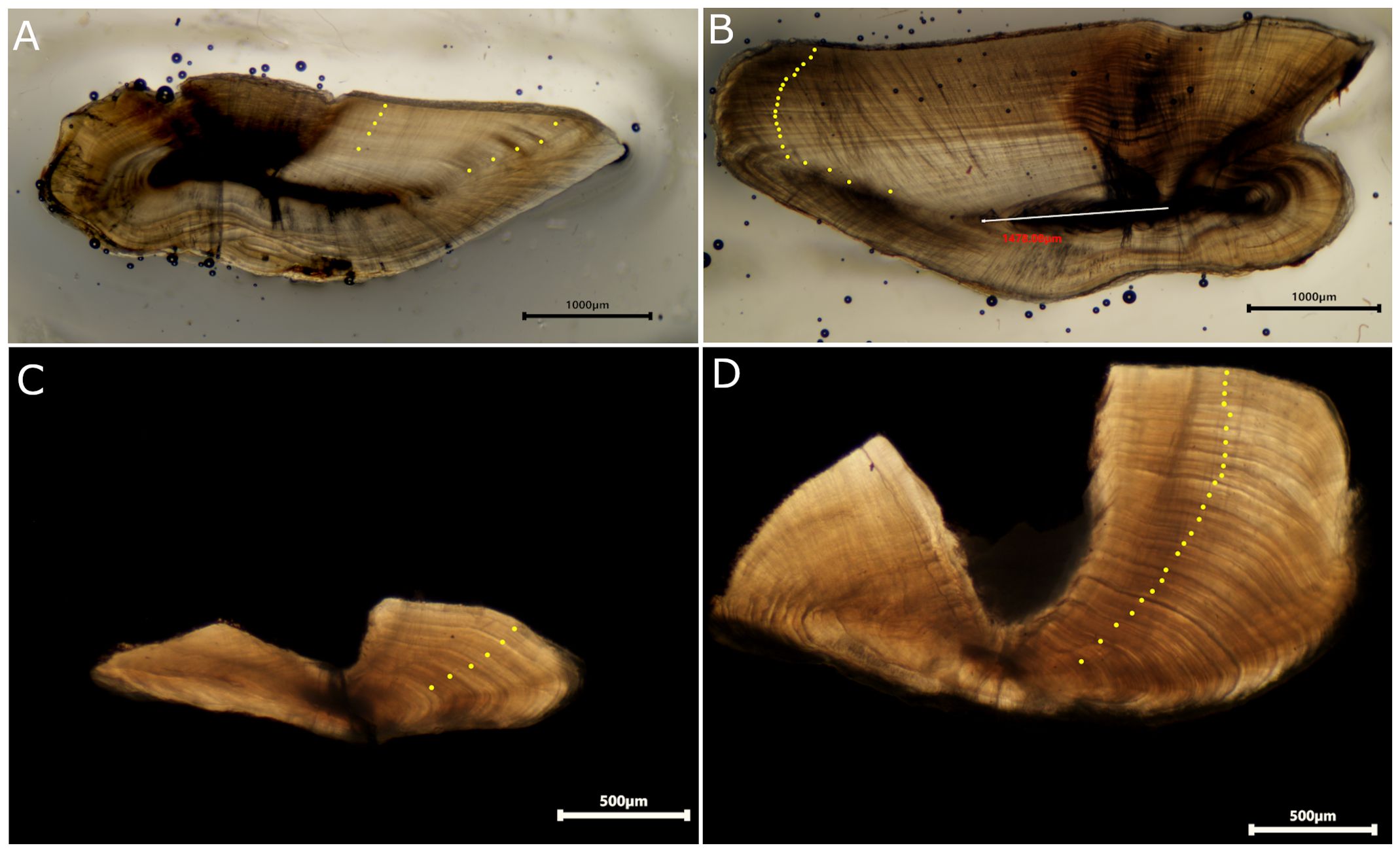

From the 556 fish sampled, otoliths from 511 samples (254 G. moringa and 257 H. adscensionis, Table 1) were considered suitable for age estimation by two expert readers under transmitted light (examples of sections for both species are shown in Figures 2A, B). Annual growth increments were identified for each species and age-determination protocols were established.

Figure 2. Sectioned otoliths of squirrelfish H. adscensionis aged 5 years (A) and 25 years (B) old, and moray eel G. moringa aged 6 years (C) and 25 years (D) old from Ascension Island. Yellow dots represent the position of the annual ring.

Otolith increments (i.e. one opaque zone and one translucent zone) from each otolith section were read twice by two experienced readers (Panfili et al., 2002). Otoliths were given a final count by each reader and, if the count agreed between readers, that count was used as the final age. When counts differed, an agreed final age was assigned after a joint reading by both readers. If no pattern was visible in the otolith section, an age was not assigned.

Life span, and mean adult body size

Mean maximum age of the 10% oldest individuals was calculated for each species at both locations, as a proxy for life span. Similarly, mean maximum size of the 10% largest individuals was calculated for the two species at both locations, as a measure of mean adult body size. Life span and mean adult body size are presented with standard error estimates.

Modelling of growth

For each species at both locations, the sizes-at-age of the individual fish was fitted with the traditional von Bertalanffy Growth Function (VBGF) to estimate growth, following the equation:

where Lt (cm) is estimated size-at-age t, L∞ (cm) is mean asymptotic size, K (year-1) is a curvature parameter and t0 (years) is age at which fish have a theoretical size of zero. The VBGF was fitted by constraining the y-intercept of the curve to an approximate size at settlement L0 of 8 mm FL for H. adscensionis and 15 mm FL for G. moringa (Tyler et al., 1993; Zokan et al., 2022). 95% confidence ellipses surrounding the VBGF estimates of parameters L∞ and K were estimated (Kimura, 1980).

Results

Otolith-based analysis of age and growth of G. moringa and H. adscensionis allowed the establishment of baseline life history information for both species, and describe differences in growth rate, body size, and life span within each of the two species between Ascension Island and St Helena. Both species varied in life span, mean adult body size, and growth between the two island territories; however, the pattern by which the two species differed in these traits between Ascension Island and St Helena was different between the two species.

G. moringa lived longer, grow faster initially, and reached a smaller adult size as a result of a reduced adult growth at Ascension Island than at St Helena (Table 2; Figure 3A). Examination of the population age structure indicated that the greater life span for G. moringa at Ascension Island was associated with a greater number of individuals in the younger age classes, despite individuals being present in age classes up to 32 years. The variation in adult size was mirrored in the size distributions of G. moringa across the two islands, revealing a distinct difference in size structure between locations; St Helena fish occupied larger size classes absent in Ascension Island (Figure 4A). In terms of growth, G. moringa displayed a clear pattern of “crossed” growth trajectories (Figure 3A). As evidenced by the higher growth coefficient K at Ascension Island (K = 1.18) than at St Helena (K = 0.26), G. moringa had faster initial growth rates over the first two years of life at Ascension Island than at St Helena (Figure 3A; Table 2). Faster initial growth was associated with smaller adult body size of G. moringa at Ascension Island, with no overlap in the 95% confidence ellipses around the best-fit VBGF parameters K and L∞, suggesting that these differences were significantly different: G. moringa at Ascension Island showed a higher K value and smaller L∞ that at St Helena (Figure 3A insert).

Table 2. Summary table showing maximum age (years), mean maximum age as a proxy for life span life span (mean age of 10% oldest individuals), maximum size (Fork Length, in cm), mean maximum size as a proxy for adult size (mean size of the 10% biggest individuals), and VBGF growth parameters L∞, K and t0.

Figure 3. Size-at-age and growth trajectories of (A) moray eel G. moringa and (B) squirrelfish H. adscensionis at Ascension Island (black dots, continuous line) and St Helena (white dots, dashed line). Size-at-age data were fitted with von Bertalanffy Growth Function (Table 2 shows VBGF growth model parameters of best-fitted growth curves below). Inserts show 95% confidence ellipses around VBGF growth parameters K and L∞..

Figure 4. Population size and age structure of (A) G. moringa and (B) H. adscensionis at Ascension Island (ASC) and St Helena (STH).

The patterns found for H. adscensionis in life span, adult body size and growth between Ascension Island and St Helena contrasted with that found for G. moringa, with an opposite direction in the response in life span and adult body size between these two locations. In contrast to G. moringa, maximum age and life span of H. adscensionis showed a comparatively younger maximum age and shorter life span but larger maximum sizes at Ascension Island than in St Helena (Table 2; Figure 4B). Comparison of the mean size of the 10% largest individuals showed that, on average, H. adscensionis reached larger body sizes at Ascension Island than at St Helena (Table 2). This coincided with a greater L∞ for H. adscensionis at Ascension Island (L∞ = 30.3 cm) than at St Helena (L∞= 27.9 cm), indicating greater adult body sizes at Ascension Island for this species (Table 2; Figure 3B). Furthermore, the growth trajectories of H. adscensionis overlapped over the ascending part of the curve between the two locations, although there was a lower value of growth coefficient K at Ascension Island (K = 0.4) than at St Helena (K = 0.54). Comparison of the 95% confidence ellipses around K and L∞ showed an overlap for K, indicating no significant difference in growth rate for this species between the two locations. In contrast, there was a significant difference in L∞, confirming the patterns found in mean maximum sizes, with a significantly greater L∞ at Ascension Island than at St Helena (Figure 3B, insert).

Discussion

This study provides essential biological information on the life history of two Ascension Island and St Helena groundfish species Gymnothorax moringa and Holocentrus adscensionis. We observed differences in life span, growth, and body size for both species between the two islands, although the direction of variation within each species differed between the two locations. There were significant differences in life span, adult body size, and growth rates between the two islands for both species: G. moringa exhibited longer life spans, faster initial growth rates and smaller adult body sizes at Ascension Island compared to St Helena, while H. adscensionis showed similar growth rates but larger adult sizes and shorter life spans at Ascension Island compared to St Helena. These data provide biological information for G. moringa and H. adscensionis that allow (i) filling the present gap in basic biological information for these two species in the two island territories, (ii) future development of monitoring and fisheries management plans within the Ascension Island and St Helena MPAs, and (iii) a basis upon which to understand population dynamics of these species between and within Ascension and St Helena populations.

Increased fishing pressure commonly results in a selection towards faster growing individuals and reduces adult body size (Ahti et al., 2020). While the level of fishing pressure exerted on the two species remains to be determined, the smaller sizes found for squirrelfish at St Helena, where fishing is authorized within the MPA may already be impacting this species. On Ascension Island, fishing pressure is not well quantified, as there are no commercial fisheries and there is no mandate for the submission of recreational catch data. The best proxy for fishing pressure is the annual export of fish. A license is required for exporting fish from the island (Customs Export Control Regulations, 2010). Between 2018 and 2023, exports of moray eel have fluctuated between 900-1200kg per year. As this rate is consistent, as is the human population size of Ascension Island, fishing pressure is not thought to have increased significantly. There is no record of squirrelfish having been exported within the same timeframe. With inshore shark activity over the last few years relatively few people have been spearfishing, presumably reducing fishing pressure on this species (pers. comm.). The implementation of a registration and licensing system in 2025 will hopefully encourage fishers to submit logbooks to better understand catch rates and feed into more accurate stock sustainability assessments.

Evaluating the health of the stock will continue to be challenging. This study was unable to include reproductive biology of the two species, so it is still uncertain at what size or age either species is sexually mature. That has implications on considering potential management measures such as minimum landing sizes. Orrell et al. (2024) concluded that moray eel has variable residency and site fidelity; therefore spatial management approaches may not be the most effective tools for protecting them. Alternative measures including bag limits or minimum landing size may be a better option. Size limits are arbitrary without further data to support the minimum size of maturity. Shinozaki-Mendes et al. (2007) estimated the size of sexual maturity in squirrelfish sampled from Brazil to be 14.6 cm fork length. This is a similar latitude to Ascension Island so it is likely the Ascension squirrelfish will reach maturity around the same size. In this study, a large number of fish sampled from fishing activities were caught below this size. If management measures are ever deemed necessary for protection of this species, setting a minimum landing size may be an effective option for ensuring that fish are able to reproduce before being taken from the system.

This study has provided baseline information on the biology of G. moringa and H. adscensionis at Ascension Island and St Helena. Assessing the potential environmental and anthropogenic impacts that may be driving the observed variation in life history traits in G. moringa and H. adscensionis between the two islands was beyond the scope of this study and will require future research. This will be essential as environmental factors (sea surface temperature, habitat productivity and availability, etc.) can directly impact population dynamics through their effect on fish growth, sexual maturation rates, reproductive ontogeny and life span (Jennings and Beverton, 1991; DeMartini et al., 2005). Locality-specific environmental conditions such as reef exposure can also directly impact growth and life span (Gust et al., 2002). Squirrelfish living in St Helena are exposed all year-round to moderate currents (average velocity 0.21 m/s) and west-northwest prevailing winds (average speed 6.32 m/s) (Ellick et al., 2013; Bacon et al., 2021), as well as colder waters and a greater amplitude of variation in average annual sea surface temperatures compared to Ascension Island. For the Ascension Islands, the average wind speed is 12.23 m/s blowing from south-east to north-west. There are complex circulation patterns including shore-parallel flows and eddies, largely dependent on tides, wind and geostrophic currents. The highest current velocities (up to 1.3 m/s) at Ascension Island are predicted to occur off the coast in water depths of up to 300 m (Coastal Marine Applied Research, 2023). Moray eel lives in a comparatively more sheltered microhabitat. This species is commonly found hiding in rock crevices and is more sedentary than squirrelfish, which are found largely on reef slopes (Orrell et al., 2024). While more sedentary than squirrelfish, G. moringa have been described as opportunistic, roving predators (Abrams et al., 1983; Young et al., 2003). They are not strictly nocturnal (Abrams et al., 1983) but their vertical migration in the water column is significantly predicted by lunar illumination, with morays occupying moderately deeper depths at night versus during the day (Orrell et al., 2024). Squirrelfish are nocturnal benthic feeders mainly targeting small crustaceans at night and leave the reef towards sand and grass beds, while moray eel often forage in the open during daylight and feed on crustaceans and fish caught by ambush. Food availability and exposure to predators vary at both locations and this may also influence the growth patterns and lifespan, and this may be especially prevalent in squirrelfish. However, the lack of data on the diet and predation dynamics of the species prevents us from drawing conclusions on the role that diet may play in the different growth trajectories observed, including on how these are impacted by differences in sea surface temperature regimes between the two islands.

It is recommended that future studies are conducted on both these species from Ascension Island and St Helena to continue to understand the species’ life histories including size and age at maturity, reproductive rates, spawning seasons and migration patterns. Additional studies should also investigate the trophic ecology of the species based on otolith stable isotopes and stomach contents, and examine the stock dynamics via otolith chemical profiles and shapes. This will continue to develop the accuracy of sustainability assessments for each fishery and allow a better understanding of biological and environmental factors affecting the in-shore fisheries species. Finally, long-term monitoring is recommended to understand the impacts of climate change.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because Not required as part of fishery landing samples.

Author contributions

ET: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Validation. IW: Methodology, Writing – original draft. TS: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation, Resources. JB: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration. PW: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. LH: Writing – review & editing, Resources. KJ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. KK-G: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SR: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology. SW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. VV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

This study was developed as part of The Blue Belt Programme, the UK Government’s flagship international marine conservation program developed to assist UKOTs in assessing and managing marine ecosystems. The Blue Belt Programme is central to the UK Government’s ambition of leading action to address the global issues of overfishing, species extinction, and climate change. The authors would like to thank the Ascension Island fishers from 2014–2021 who contributed their catch data as well as AIGCFD staff who compiled the data as part of the ongoing pierhead surveys.

Conflict of interest

Authors LH and KJ were employed by the company Fish Aging Services Pty Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abrams R. W., Abrams M. D., and Schein M. W. (1983). Diurnal observations on the behavioral ecology of Gymnothorax moringa (Cuvier) and Muraena miliaris (Kaup) on a Caribbean coral reef. Coral Reefs 1, 185–192. doi: 10.1007/BF00571196

Ahti P. A., Kuparinen A., and Uusi-Heikkilä S. (2020). Size does matter — the eco-evolutionary effects of changing body size in fish. Environ. Rev. 28, 311–324. doi: 10.1139/er-2019-0076

(2023). Ascension island inshore fisheries management strategy. Available online at: https://www.ascension.gov.ac/project/ascension-island-inshore-fisheries-strategy-march-2023.

Bacon J., Fernand L., and Young E. (2021). Hydrodynamic modelling with Telemac3D at St Helena. iv + 49.

Bedford B. C. (1983). A method for preparing sections of large numbers of otoliths embedded in black polyester resin. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 41, 4–12. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/41.1.4

Berumen M. L., Trip E., Pratchett M. S., and Choat J. H. (2012). Differences in demographic traits of four butterflyfish species between two reefs of the Great Barrier Reef separated by 1,200 km. Coral Reefs 31, 169–177. doi: 10.1007/s00338-011-0838-z

Caselle J. E., Hamilton S. L., Schroeder D. M., Love M. S., Standish J. D., Rosales-Casian J. A., et al. (2011). Geographic variation in density, demography, and life history traits of a harvested, sex-changing, temperate reef fish. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci. 68, 288–303. doi: 10.1139/F10-140

Coastal Marine Applied Research (2023). Ascension island circulation modelling, model development report 2210_d2_v1 (Plymouth, UK: University of Plymouth Enterprise Limited), 54 pp.

Customs Export Control Regulations (2010). Available online at: https://www.sainthelena.gov.sh/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Customs-Ordinance-Updated-25-September-2018.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Day J., Dudley N., Hockings M., Holmes G., Laffoley D., Stolton S., et al. (2019). Guidelines for applying the IUCN protected area management categories to marine protected areas. 2nd ed (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN).

DeMartini E. E., Friedlander A. M., and Holzwarth S. R. (2005). Size at sex change in protogynous labroids, prey body size distributions, and apex predator densities at NW Hawaiian atolls. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 297, 259–271. doi: 10.3354/meps297259

Edwards A. J (1990). Fish and fisheries of Saint Helena island.Centre for Tropical Coastal Management Studies, University of Newcastle upon Tyne [for the] Education Department of the Government of Saint Helena.

Ellick S., Westmore G., and Pelembe T. (2013). St. Helena state of the environment report april 2012 - march 2013 (Environmental Management Division, St. Helena Government). Available online at: https://www.sainthelena.gov.sh/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/State-of-the-Environment-Report-2012-2013-FINAL-v2.pdfpage=8 (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Fisheries Ordinance (2021). Available online at: http://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/sth216187.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Gust N., Choat J., and Ackerman J. (2002). Demographic plasticity in tropical reef fishes. Mar. Biol. 140, 1039–1051. doi: 10.1007/s00227-001-0773-6

Hamilton S. L., Caselle J. E., Lantz C. A., Egloff T. L., Kondo E., Newsome S. D., et al. (2011). Extensive geographic and ontogenetic variation characterizes the trophic ecology of a temperate reef fish on southern California (USA) rocky reefs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 429, 227–244. doi: 10.3354/meps09086

Hamilton S., Caselle J., Standish J., Schroeder D., Love M., Rosales-Casian J., et al. (2007). Size-selective harvesting alters life histories of a temperate sex-changing fish. Ecol. Appl. 17, 2268–2280. doi: 10.1890/06-1930.1

Hawkins J. P. and Roberts C. M. (2004). Effects of fishing on sex-changing Caribbean parrotfishes. Biol. Conserv. 115, 213–226. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00119-8

Jennings S. and Beverton R. J. H. (1991). Intraspecific variation in the life history tactics of Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus L.) stocks. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 48, 117–125. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/48.1.117

Kimura D. K. (1980). Likelihood methods for the von Bertalanffy growth curve. Fishery Bull. 77, 765–776.

Marine Conservation Institute (2025). MPAtlas [online]. Available online at: http://www.mpatlas.org (Accessed May 14, 2025).

Orrell D. L., Sadd D., Jones K. L., Chadwick K., Simpson T., Philpott D. E., et al. (2024). Coexistence, resource partitioning and fisheries management: A tale of two mesophotic predators in equatorial waters. Fish Biol. 106, 1377–1399. doi: 10.1111/jfb.15744

Panfili J., de Pontual H., Troadec H., and Wright P. J. (2002). Manual of fish sclerochronology (Brest, France: Ifremer-IRD co-edition), 464–4p+.

Pears R. J., Choat J. H., Mapstone B. D., and Begg G. A. (2006). Demography of a large grouper, Epinephelus fuscoguttatus, from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef: implications for fishery management. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 307, 259–272. doi: 10.3354/meps307259

Robbins W. D. and Choat J. H. (2002). Age-based dynamics of tropical reef fishes; A guide to the processing, analysis and interpretation of tropical fish otoliths. Townsville Aust., 1–39.

Shinozaki-Mendes R. A., Hazin F. H. V., De Oliveira P. G., and De Carvalho F. C. (2007). Reproductive biology of the squirrelfish, Holocentrus adscensionis (Osbeck 1765), caught off the coast of Pernambuco, Brazil. Scientia Marina 71, 715–722. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2007.71n4715

St Helena Marine Management Plan (2023). Available online at: https://www.sainthelena.gov.sh/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/St-Helena-MMP_FINAL_2023.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Trip E., Choat J. H., Wilson D. T., and Robertson D. R. (2008). Inter-oceanic analysis of demographic variation in a widely distributed Indo-Pacific coral reef fish. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 373, 97–109. doi: 10.3354/meps07755

Tyler J. C., Johnson G. D., Brothers E. B., Tyler D. M., and Smith C. L. (1993). Comparative early life histories of western Atlantic squirrelfishes (Holocentridae): age and settlement of Rhynchichthys meeki, and juvenile stages. Bull. Mar. Sci. 53, 1126–1111.

Visconti V., Trip E. D. L., Griffiths M. H., and Clements K. D. (2018). Life-history traits of the leatherjacket Meuschenia scaber, a long-lived monacanthid. J. fish Biol. 92, 470–486. doi: 10.1111/jfb.13529

Visconti V., Trip E. D. L., Griffiths M. H., and Clements K. D. (2020). Geographic variation in life-history traits of the long-lived monacanthid Meuschenia scaber (Monacanthidae). Mar. Biol. 167, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00227-019-3628-8

Young R. F., Winn H. E., and Montgomery W. L. (2003). Activity patterns, diet and shelter site use for two species of moray eels, Gymnothorax moringa and Gymnothorax vicinus, in Belize. Copeia 1, 44–55. doi: 10.1643/0045-8511(2003)003[0044:APDASS]2.0.CO;2

Keywords: blue belt, fisheries, growth, otoliths, Southern Atlantic, United Kingdom overseas territory

Citation: Visconti V, Trip EDL, Woodgate I, Simpson T, Bell JB, Whomersley P, Henry L, Jones K, Krusic-Golub K, Robertson S and Wright S (2025) Otolith-based age and growth of the spotted moray eel (Gymnothorax moringa) and squirrelfish (Holocentrus adscensionis) from Ascension Island and St Helena. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1705888. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1705888

Received: 15 September 2025; Accepted: 11 November 2025; Revised: 07 November 2025;

Published: 16 December 2025.

Edited by:

Marco Albano, University of Messina, ItalyReviewed by:

Peter Coulson, University of Tasmania, AustraliaClaudio D’Iglio, University of Messina, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Visconti, Trip, Woodgate, Simpson, Bell, Whomersley, Henry, Jones, Krusic-Golub, Robertson and Wright. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valerio Visconti, dmFsZXJpby52aXNjb250aUBjZWZhcy5nb3YudWs=

†These authors share first authorship

Valerio Visconti

Valerio Visconti Elizabeth D. L. Trip

Elizabeth D. L. Trip Ian Woodgate

Ian Woodgate Tiffany Simpson3

Tiffany Simpson3 Paul Whomersley

Paul Whomersley Leeann Henry

Leeann Henry Kyne Krusic-Golub

Kyne Krusic-Golub