Abstract

Marine plastic pollution is a problem that crosses borders and needs immediate global cooperation. This kind of cooperation needs to be based on a single international framework that fairly and authoritatively divides up responsibilities while respecting national sovereignty. Although the Fifth United Nations Environment Assembly initiated an intergovernmental negotiating committee to develop a legally binding Global Plastics Treaty by 2024, no agreement has been reached by the fifth session in 2025. Key issues persist surrounding plastic source control, financing mechanisms, and raw material regulation. This paper examines how the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) can apply to global marine plastic governance. This study first examines the doctrinal foundations of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) and explains why it is relevant to marine plastic pollution. It then analyses the main points of contention surrounding CBDR in the ongoing plastics treaty negotiations, including debates over differentiation, obligations, and implementation. Finally, it reviews state and institutional practice at the national, regional, and multilateral levels to assess how CBDR is applied or contested. The analysis shows that CBDR remains contested in marine plastic governance. Problems include the instrumental use of CBDR by different actors, inconsistencies in responsibility differentiation, outdated categorical groupings, interpretive disagreements, and deadlock over means of implementation. These issues limit CBDR’s ability to support an effective plastics treaty. Based on these findings, the paper proposes strategies to apply CBDR better. These include improving procedural rules, developing a dynamic and tiered responsibility system, designing a framework with core and flexible obligations, and establishing comprehensive support and monitoring mechanisms. In summary, these measures can illustrate the potential for CBDR to move beyond its divisive role and serve as a more nuanced governance tool for reconciling diverse national interests and capacities. Such an approach could contribute to laying the groundwork for an effective and universal plastics treaty by enabling a fairer allocation of responsibilities.

1 Introduction

Plastics are a cornerstone of the modern global economy, widely used across industrial and consumer sectors due to their durability, versatility, and low cost (Weng et al., 2024). However, the very properties that make plastics valuable also make them a persistent environmental threat. Most plastics do not biodegrade naturally, and inadequate waste management has led to the accumulation of immense quantities of plastic refuse. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), over 400 million tons of plastic are produced annually, with two-thirds of this amount being short-lived products that quickly become waste, thereby polluting the environment (UNEP, 2025b). Conventional disposal methods such as incineration, landfilling, and thermal cracking face significant technical and administrative challenges, resulting in widespread leakage of plastic waste into terrestrial and marine ecosystems (Qian et al., 2025). Moreover, up to 90% of greenhouse gas emissions linked to the plastics sector occur during polymer and product production (Karali et al., 2024). Around 25% of all plastics manufactured end up polluting the environment. Of this, 6 million tons end up in rivers and along coastlines annually (UN plastics treaty, 2024). The consequences are multifaceted, inflicting direct economic damage on maritime industries, such as tourism and shipping, while also degrading marine ecosystems and posing indirect risks to human health through the food chain, and causing direct physical harm and mortality to marine life through entanglement and ingestion (Yang, 2024). Crucially, the burden of marine plastic pollution is not evenly distributed. The challenges faced by developed and developing nations differ significantly, and specific geographic locations, such as Small Island Developing States (SIDS), are disproportionately affected compared to continental coastal states. This has elevated marine plastic pollution to a critical global governance issue requiring urgent international cooperation (Vince and Hardesty, 2017). However, the current global governance architecture is ill-equipped to handle this escalating crisis. It is characterized by decentralized authority, weak international institutions, an uneven regulatory landscape, and a heavy reliance on voluntary initiatives and regional agreements, all of which have proven insufficient to curb the worsening pollution (Dauvergne, 2018). In light of these shortcomings, establishing a unified, legally binding global framework is essential to effectively address the challenge of marine plastic pollution (Maes et al., 2023).

In response to this need, the United Nations Environment Assembly adopted Resolution 5/14, “End plastic pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument,” on March 2, 2022. The resolution established an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) with a mandate to develop a legally binding global plastics treaty by the end of 2024 (UNEP, 2022a). While these negotiations represent a landmark opportunity, the five INC sessions held to date have yet to produce a final treaty. Progress has been hampered by fundamental disagreements among states, particularly concerning the allocation of obligations, the balancing of economic interests, and the design of financial and technical assistance mechanisms (Muraki Gottlieb, 2021). The core of this study lies in the persistent deadlock in the negotiations toward a Global Plastics Treaty. This deadlock stems largely from the divergent interpretations and contested applications of the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR). This research seeks to examine how the CBDR principle can be reconceptualized and operationalized to overcome these divisions and contribute to a more effective, equitable, and universally accepted global framework for plastic pollution governance. Specifically, it investigates three interrelated questions: (1) how different actors and coalitions have instrumentalized CBDR in the treaty negotiations, thereby shaping the current impasse; (2) how differentiated responsibility has been applied, with varying degrees of success, across national, regional, and multilateral plastic governance regimes; and (3) what innovative procedural, substantive, and financial mechanisms could transform CBDR from a source of political contention into a practical tool of cooperation.

The article adopts a multi-method research design. A historical analysis traces the evolution of the CBDR principle throughout the INC process, while a comparative analysis examines its differentiated application across national, regional, and multilateral governance frameworks. In addition, a normative and legal-sociological approach identifies the underlying legal tensions, the political and economic instrumentalization of the principle, and potential pathways for institutional innovation. Chapter 3 applies purposive and comparative case selection criteria based on influence, typological representativeness, and contextual diversity. The selected cases include the European Union, the United States, China, and Russia, as well as regional and multilateral frameworks such as OSPAR and the Basel Convention, which represent distinct models of CBDR practice, including peer-based, procedural, and universal-prohibition approaches. Using qualitative content analysis, the study systematically collects and reviews treaty drafts, national submissions, and reports from INC-1 to INC-5 to identify the evolution of state positions across four key dimensions: CBDR interpretation, financial mechanisms, upstream production control, and sovereignty. To reduce confirmation bias, the study employs data triangulation, disconfirming evidence tests, and alternative explanation analysis, incorporating factors such as political cycles and industrial protectionism. However, the highly politicized nature of the negotiations results in inevitable data opacity, and reliance on qualitative analysis involves inherent risks of interpretive bias. Moreover, although the comparative case studies are representative and influential, they cannot fully capture the diversity of state positions.

2 The principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and the global governance of marine plastic pollution

Legal principles provide the foundational stability and guidance for legal rules, embodying broader academic theories and policy objectives. As such, they reflect the underlying values and standpoints of a given regulatory regime. Scholars differ on the legal status of CBDR in international environmental law. Some scholars assert that CBDR is a fundamental principle of international environmental law, broadly applied across various international environmental protection regimes (Stalley, 2018). Others characterize it as a guiding principle or a “soft law” norm, intended to shape negotiations rather than impose standalone legal obligations (Petrescu-Mag et al., 2013). Regardless of this debate, the CBDR principle provides an essential framework for addressing the global challenge of marine plastic pollution, offering both a relevant context and a necessary approach for structuring equitable international cooperation (Zhou et al., 2023). This section provides a theoretical analysis of the Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) principle. It first outlines the core legal and conceptual foundations of the principle, then examines its structural and functional relevance to the global governance of marine plastic pollution. Based on this theoretical framework, the section further explores the key controversies concerning the application of CBDR within the negotiations of the Global Plastics Treaty. The purpose of this analysis is to identify potential pathways for the principle’s application and to provide a theoretical foundation for the subsequent discussion on its practical implementation in global plastic pollution governance.

2.1 The doctrinal foundations of the CBDR principle

First, the connotation of shared responsibility. Five elements support a finding of common responsibility: common challenge, common interest, common concern, shared responsibility, and the global public interest. A common challenge is a problem or risk faced by people as a whole and caused by multiple actors, so that it cannot be attributed to a single actor for purposes of international responsibility (Yan, 2023). Examples include marine pollution, climate change, ozone depletion, and biodiversity loss. A common challenge is the basis for the emergence of shared responsibility. A common interest refers to an issue that affects the interests of humankind rather than just one state, such as international peace and development, and the basic conditions for human survival (Borrelle et al., 2017). The commonality of interests provides countries with the motivation and purpose for joint action, which is the objective condition for the emergence of shared responsibility. Common concern reflects states’ recognition of these shared challenges and interests. Levels of concern shift in response to national conditions, but states tend to converge on minimum shared points and red lines. These shared understandings enable cooperation and the building of common responsibility. On this basis, a common responsibility arises: all states share responsibility for global environmental challenges. No state (including developed, developing, or least developed) stands outside the responsibility framework (Lee, 2015). In international environmental law, this idea has three layers. The first is a moral responsibility to protect the environment on which all life depends. The second is a political responsibility to act together and to cooperate on shared problems (Yang, 2024). The third is a substantive legal responsibility, namely the common legal obligations found in environmental treaties. The global public interest clarifies the ethic behind common responsibility. Its purpose is to protect the interests of humans and other species, of states and the international community, and of present and future generations. This provides the basic rationale for implementation.

Secondly, the connotation of differentiated responsibility. Differentiated responsibility highlights differences in responsibility. It is the route by which common responsibility is made effective. The term itself points to variation, which is why the concept needs clear treatment in international law. The primary sources of international law are custom and treaties. Custom rests on general practice and opinion juris and does not provide a stable basis for a commitment to differentiated responsibility. This section, therefore, focuses on treaties. Treaties may be bilateral or multilateral. In bilateral treaties, different parties often assume different duties. In multilateral treaties, differentiation is not automatic and may appear to sit uneasily with the principles of sovereign equality and reciprocity.

In international environmental treaties, two grounds justify differentiation: historical contribution to environmental harm and differences in capacity to respond (Gupta and Sanchez, 2013). Differentiation does not mean that developed states bear all duties and developing states bear none. That would contradict the premise of shared responsibility. As a matter of fairness, when a state has gained by shifting costs to others without their consent, those who were disadvantaged may require the former to bear at least the value of that unfair gain to restore equality (Shue, 1999). Early industrialization by developed states damaged the environment and reduced the environmental space of developing states. These states should therefore carry a larger share of the initial costs of remediation. Developing states also have duties, but these must be tailored to reflect their capacity constraints (Singh, 2022). Differences in capacity refer to the differences in the ability to govern and comply that arise from a country’s development stage and national conditions. In practice, it encompasses financial resources, technology, and the capacity to organize and integrate these resources effectively. In sum, given historical contributions and capacity differences, obligations and timelines should be allocated in a differentiated manner, and implementation should be tailored accordingly, all within the framework of shared responsibility.

Finally, CBDR is not two separate systems of “common” and “differentiated” responsibility. The addressees and the mode of performance are the same, since states implement treaty duties. What differs are the content, scope, and timing of those duties. Common responsibility states the value and the goal. Differentiation is the means to achieve that goal. It defines, calibrates, and schedules the common responsibility so that it can be carried out in practice.

2.2 The integration of the CBDR principle with the global governance of marine plastic pollution

Global governance of marine plastic pollution requires that all states share responsibility. First, marine plastic pollution is a quintessential global challenge (Yu et al., 2023), as plastic waste originates from numerous sources and is transported by ocean currents worldwide, making it impossible to attribute the problem to any single country. Second, Clean oceans represent a common interest for all nations. The ocean serves not only as a global climate regulator but also provides essential resources, including food, medicine, and energy for humanity, while functioning as a vital channel for global trade. The destruction of marine ecosystems by plastic pollution poses a significant threat to these common interests, affecting global marine biodiversity, food security, and human health. Therefore, global marine plastic pollution governance aligns with the common interests of all countries, providing objective grounds for international cooperation. Third, Marine plastic pollution has become a significant concern for the international community. Since the United Nations Environment Assembly first adopted a resolution on marine plastic litter and microplastics in 2014 (UNEA, 2014), international attention to marine plastic pollution has continued to increase. Although countries differ in their levels of concern and focus regarding this issue, a basic understanding has emerged that marine plastic pollution necessitates a global collective response, providing a cognitive foundation for effective global governance of marine plastic pollution. Moreover, these three elements collectively generate common responsibility for marine plastic pollution governance (Tanaka, 2023). In global marine plastic pollution governance, all countries should contribute within their respective capacities to reduce plastic waste entering the ocean and work together to protect the marine environment. Finally, global marine plastic pollution governance exhibits significant public benefits globally. Marine protection concerns present and future generations, coastal and land-locked states, and human and non-human life. This global public benefit provides the underlying cognitive construction for shared responsibility in marine plastic pollution governance.

Then, states bear differentiated responsibilities in the global governance of marine plastic pollution. The legitimacy of differentiated responsibilities stems primarily from two sources: historical contributions of plastic waste to marine environmental destruction and differences in capacity to address plastic pollution. Regarding historical contribution differences, developed countries pioneered the large-scale use of plastic materials during industrialization, generating substantial plastic waste that entered marine environments. These historical emissions form the basis for developed countries to assume greater responsibility for addressing marine plastic pollution. While developed countries should bear greater responsibility, developing countries cannot be completely exempt from responsibility, particularly emerging economies with rapidly growing plastic pollution emissions. Differences in capacity to address marine plastic pollution manifest in three main aspects. First, the capacity for a plastic waste management system, including collection, classification, recycling, and treatment capabilities. Second, the capacity for research, development, and application of plastic alternative materials. Third, the capacity for monitoring and assessing plastic pollution. Developed countries generally possess advantages in these three areas, while many developing countries face challenges, including insufficient infrastructure and limited technological capabilities. When establishing global marine plastic pollution governance mechanisms, the capacity limitations of developing countries must be fully taken into account. This requires bridging capacity gaps through technology transfer, financial support, and capacity-building measures to enable the effective participation of developing countries in global governance.

Finally, in global marine plastic pollution governance, common responsibility establishes the basic framework for state participation, while differentiated responsibility allocates specific responsibilities based on historical contributions and capacity differences among countries. These two elements are not opposing but rather complementary components of a whole. Differentiated responsibility does not negate common responsibility but rather provides reasonable arrangements for implementing common responsibility to ensure its practical realization. At the operational level, global marine plastic pollution governance mechanisms should simultaneously include universally applicable basic obligations that reflect common responsibility and differentiated specific obligations.

In summary, the CBDR principle has a profound connection with global marine plastic pollution governance. This coupling provides a theoretical foundation for constructing a fair and effective global governance system for marine plastic pollution, while offering theoretical guidance for resolving international disagreements over the allocation of responsibility.

2.3 Controversies regarding the application of the CBDR principle in global marine plastic pollution governance

Based on the connotation of the CBDR principle and its application in global marine plastic pollution governance, this paper identifies the core disputes in global plastic treaty negotiations to clarify the pathway for applying the CBDR principle in global plastic pollution governance (Wang, 2025).

At the first and second sessions of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-1 in Punta del Este and INC-2 in Paris), the debate framework concerning the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) was established. From the outset, CBDR emerged as a fundamental issue dividing negotiating blocs. At INC-1, developing countries represented by the African Group, the Latin American and Caribbean Group (GRULAC), the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), and the Pacific Small Island Developing States explicitly invoked the CBDR principle. They stressed that access to means of implementation, including financial resources, technology transfer, and capacity building, was a prerequisite for assuming substantive obligations (UNEP, 2022c), and they demanded that developed countries take the lead in providing such support. This position sparked a debate between a “top down” approach advocating globally uniform rules and a “bottom up” approach emphasizing nationally determined measures (UNEP, 2022b). By the time of INC-2, these divergences had further consolidated. Many developing countries underscored the necessity of recognizing CBDR as an overarching principle of the treaty, a position that was firmly opposed by some states. During this session, the High Ambition Coalition (HAC), led by Rwanda and Norway, formally articulated its core demand, namely regulating upstream activities such as plastic production (UNEP, 2023a). In contrast, the oil-producing countries (McDERMOTT, 2025) including Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Russia, consolidated their strong opposition to production controls and argued that the treaty should focus exclusively on downstream waste management (Plastics pollution is surging — the planned UN treaty to curb it must be ambitious, 2025). At the same time, procedural questions, particularly the choice between consensus and voting rules, began to be used by these countries as a strategy to delay negotiations (UNEP, 2023b). These two sessions highlighted the strategic divergence over CBDR in the governance of global plastic pollution. For most members of the Group of 77, CBDR embodies principles of equity and empowerment, meaning that developed countries must provide the means to realize shared objectives. For powerful oil-producing nations, however, CBDR has increasingly been framed as a principle of sovereignty and exception.

At the third and fourth sessions of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-3 in Nairobi and INC-4 in Ottawa), the debate over the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) shifted from the principle itself to the precise wording of the treaty text. Discussions centered on how CBDR should be reflected in the text, with the “zero draft” emerging as the focal point. This document marked the beginning of a trench warfare phase in the negotiations. The Like-Minded Group (LMG) and other countries argued that the draft was imbalanced and failed to reflect their perspectives adequately. They stressed the need for inclusiveness in the text and demanded that all options be incorporated (ENB, 2023), including a “no text” option under key provisions such as production control. These demands caused the draft to expand significantly in size and complexity, producing multiple contradictory options. The LMG explicitly invoked the principle of permanent sovereignty over natural resources to reject production controls, interpreting CBDR in this way (UNEP, 2023c). At INC-4, negotiations were based on a heavily expanded “revised zero draft.” Positions among delegations became more entrenched. The High Ambition Coalition (HAC), the African Group, and others continued to advocate for legally binding global rules on primary plastic polymers (PPPs) and financing arrangements. In contrast, the LMG persisted in promoting voluntary measures and sought to shift the agenda toward downstream issues such as recycling. One of the key outcomes of INC-4 was the decision to establish two open-ended ad hoc expert groups during the intersessional period. The first was tasked with analyzing options for implementing the instrument’s objectives, including potential financial mechanisms, adjustments in financial flows, and identifying possible sources and means of mobilizing finance, with the results to be considered at INC-5. The second was mandated to identify and analyze both standard and non-standard approaches regarding plastic products and chemicals of concern contained in such products, as well as product design, with an emphasis on recyclability and reusability, again to be considered at INC-5 (ENB, 2024a). However, under the persistent insistence of the LMG, the mandate of the expert group on plastics and chemicals of concern was significantly diluted. Its focus shifted away from production levels toward product design. During this session, the “Busan Bridge” Declaration began to take shape. This initiative was intended to sustain high ambition and reflected the growing frustration among ambitious states over the slow pace of negotiations (UNEP, 2024b).

Finally, at the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (The first part of the fifth session (INC-5.1) took place from 25 November to 1 December 2024 in Busan, Republic of Korea. The second part of the fifth session (INC-5.2) took place from 5 to 15 August 2025 in Geneva, Switzerland. The INC5.1 was not closed, but rather continued in Geneva), negotiations on the applicability of the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) reached an impasse, which led to the drafting of the Chair’s text. What had originally been planned as the final negotiating round ended in stalemate, with no agreement achieved (UNEP, 2025a). The central division persisted. The High Ambition Coalition (HAC), supported by more than one hundred states, pressed for legally binding upstream measures, while the Like-Minded Group (LMG), led by Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Iran, strongly opposed any ceiling on plastic production (UNEP, 2025a). To break the deadlock, the Chair introduced a simplified “non-paper,” which later became the Chair’s text, in an attempt to focus on consensus. Yet large portions of this document were bracketed, indicating that the content had not been agreed upon and would need to be renegotiated in full. The failure of both INC-5.1 and INC-5.2 reflected the fundamental divergence over the practical application of CBDR. On one side, CBDR was understood as obliging developed countries to provide financial and technological support for the global transition toward lower levels of plastic production. On the other side, CBDR was interpreted as affirming the right of states, particularly developing countries, to determine their own development trajectories, including the continuation of plastic production. Within the consensus-based decision-making framework of the United Nations, these opposing interpretations effectively stalled progress in the negotiations.

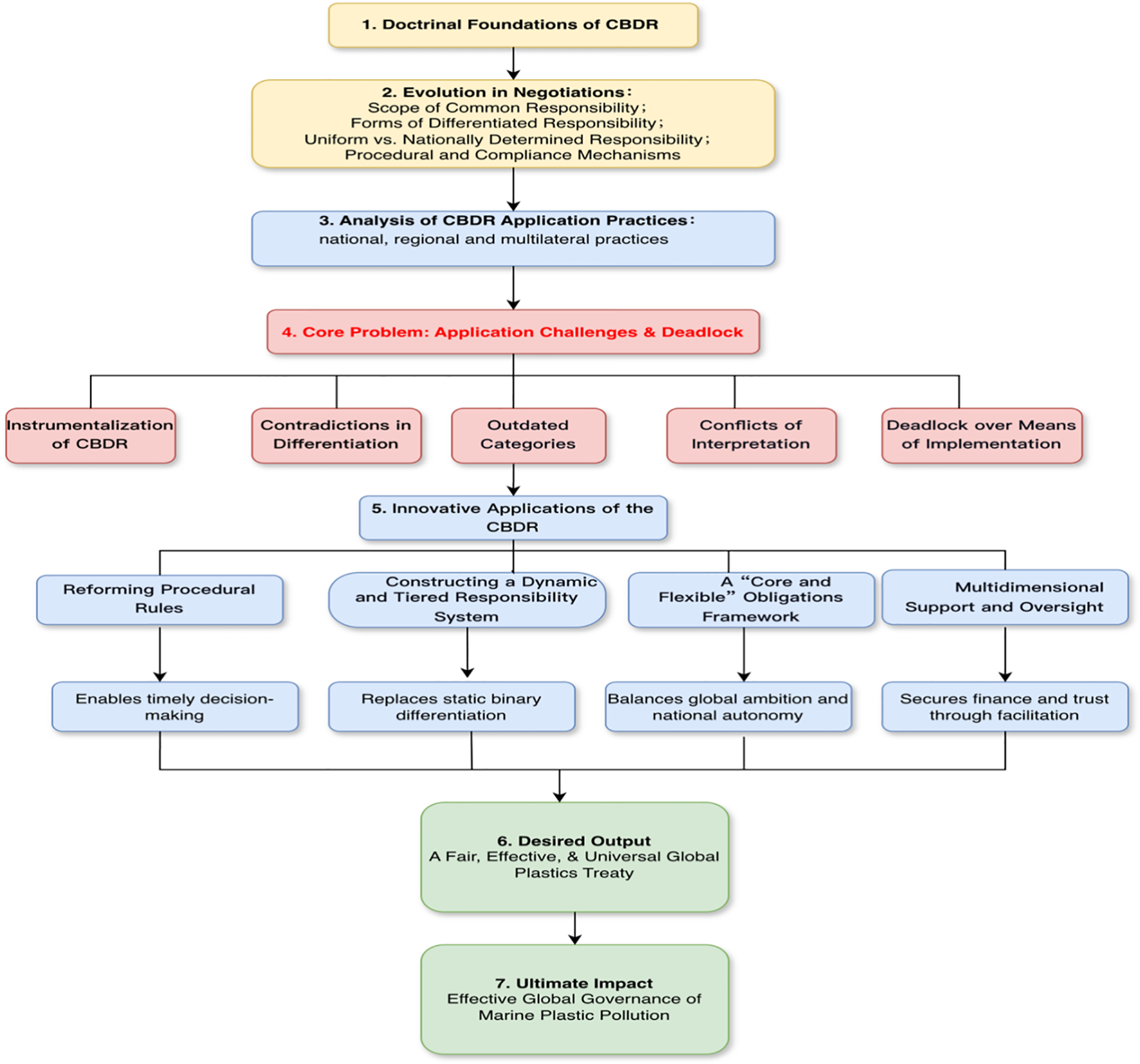

In summary, the application of CBDR within the global plastics treaty can be categorized into four dimensions. The first concern is whether common obligations should address the entire life cycle of plastics or be confined to downstream waste management. The second relates to whether differentiation should be expressed in the substance of obligations themselves or through means of implementation, such as financial support and technology transfer. The third concerns whether responsibilities should primarily take the form of uniform binding commitments or nationally determined measures. The fourth involves the role of procedural safeguards, such as prior informed consent (PIC) and compliance facilitation, within differentiated arrangements. These four dimensions reveal deep divisions in governance practice and form the core of the current negotiating deadlock. The CBDR principle transitions from a theoretical concept into a practical governance instrument. The specific theoretical evolution and the logical framework of this paper are delineated in the Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Specific theoretical evolution and the logical framework of this paper.

3 Application of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities in the global governance of marine plastic pollution

Building on the analysis of CBDR pathways in the global plastics treaty, this section examines the practical application of the principle in the governance of marine plastic pollution. Given the inherent differentiation of responsibilities among parties in bilateral treaties, the analysis follows a three-tiered structure, focusing on national, regional, and multilateral practices.

3.1 National practices of CBDR

As the primary actors in international relations, sovereign states shape both the interpretation and implementation of CBDR in the governance of marine plastic pollution. The application of CBDR at the national level is therefore inseparable from questions of power within international law and order (Ota and Ecoma, 2022), and the positions of major powers are of particular significance. Although the European Union (EU) is formally a regional organization, its high degree of political and economic integration, as well as its supranational institutions with regulatory and enforcement capacity, justify its inclusion in this analysis as a quasi-state actor. For major powers, interpretations of CBDR are rarely grounded in purely legal obligations but instead reflect domestic policies, economic structures, and global strategic interests, leading to clear strategic divergences.

3.1.1 The European Union: normative and precautionary application of the CBDR

The EU’s core position is that all countries should bear binding common obligations addressing the full life cycle of plastics, with particular emphasis on upstream controls of primary plastic polymer production (EU, 2025). In the EU’s view, CBDR does not directly determine the allocation of obligations and responsibilities for marine plastic pollution, nor should it justify exemptions from core commitments (European Union and Member States, 2023). Instead, differentiation should be expressed primarily through implementation mechanisms and transitional arrangements. This includes financial assistance, technology transfer, and more flexible compliance timelines for developing countries to help them achieve shared governance objectives. At the same time, the EU strongly promotes the “polluter pays” principle and supports the establishment of related financial mechanisms. However, it remains cautious toward the creation of a new fund financed exclusively by mandatory contributions from developed countries, preferring instead to build on existing financial arrangements and mobilize private and social capital (EU, 2024). The EU’s interpretation of CBDR can therefore be characterized as partially recognizing historical responsibilities and differences in capacity while firmly rejecting exemptions from core control measures. The European Union’s interpretation of the Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) principle is shaped by legal, economic, and political considerations. From a legal perspective, the EU’s position is rooted in the precautionary principle and the right to sustainable development, which provides a clear legal basis for adopting preventive and source-oriented measures even when scientific evidence is uncertain (De Smedt and Vos, 2022). This legal foundation corresponds closely with the EU’s economic strategy, as promoting globally binding and high-standard regulations allows the Union to project its internal regulatory model internationally. This approach, often described as the “Brussels Effect” (Ylönen, 2026), helps to ensure fair competition for its highly regulated industries and encourages leadership in markets for green technologies, chemical substitutes, and circular-economy solutions. Politically, the EU’s understanding is consistent with the experience of the Montreal Protocol, which demonstrates how flexibility in implementation can reconcile fairness with effectiveness in global environmental governance (Green, 2009).

3.1.2 The United States: elective and opportunistic application of the CBDR

The United States approaches the Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) principle through a politically driven and pragmatic lens rather than as a consistent legal doctrine (Li, 2023). At the early stages of the INC negotiations, the United States proposed a “nationally driven” approach to addressing plastic pollution, advocating that each state formulate and update legally binding National Action Plans (NAPs) (US, 2023). This position reflected an interpretation of CBDR that emphasized national sovereignty. As the negotiations progressed, however, the U.S. position showed subtle shifts, including support for restrictions on primary plastic production, signaling alignment with more ambitious goals (Rosengren, 2024). Yet subsequent developments indicated a retreat toward flexible approaches, favoring voluntary reduction targets determined by individual states (Winters, 2024). This oscillation reflected the tension between environmental policy priorities and the influence of the powerful petrochemical industry (Mosbergen, 2019). Moreover, this position reflects domestic political volatility, as shifts in presidential administrations have repeatedly altered the nation’s stance toward global environmental agreements. This oscillation demonstrates that foreign environmental policy is primarily determined by internal political dynamics rather than long-term legal commitments. Regarding financing, the United States acknowledged the need to support “countries most in need” while rejecting the establishment of new mandatory funding mechanisms. Instead, it preferred to rely on existing channels and to mobilize private and social capital (ENB, 2024b). In practice, the U.S. application of CBDR has been marked by opportunism and pragmatism. It seeks to demonstrate leadership and shape global rules, while at the same time avoiding any binding international obligations that could constrain its domestic economic or policy space (Volcovici, 2024).

3.1.3 China: pragmatic application of the CBDR

China’s interpretation of CBDR is complex and evolving. Firstly, it emphasizes equity and the right to development, consistently invoking CBDR to highlight the historical responsibilities of developed countries and their obligation to provide developing states with adequate financial, technological, and capacity-building support. Secondly, China aligns with the Like-Minded Group (LMG), including countries such as Saudi Arabia and Russia, in opposing legally binding global targets for production reduction (Iran, 2023). It stresses inclusiveness in treaty design, insisting that decisions on core obligations must be reached through consensus (China, 2024). However, recent developments demonstrate that China’s approach to plastic pollution governance is increasingly characterized by domestic policy autonomy and gradual internal reforms rather than reliance on external global regulation. Domestically, China has introduced several milestone policies, including the 2017 import ban on 24 categories of solid waste, the 2020 Opinions on Further Strengthening Plastic Pollution Control, followed by the 14th Five-Year Plan for Plastic Pollution Control (2021–2025) (Xu, 2025). These initiatives have built a progressively stricter regulatory framework covering production, consumption, recycling, and waste management. By pursuing incremental domestic regulation, China seeks to mitigate plastic pollution while safeguarding its policy space within global governance (Fürst and Feng, 2022). This dual strategy allows China to advocate differentiation internationally, demanding fair support from developed states, while maintaining sovereign control over the pace and structure of domestic environmental transitions. The result is a pragmatic model that combines the principles of CBDR with self-directed policy innovation, demonstrating how developing powers can reconcile environmental responsibility with national development priorities.

3.1.4 Russia: conservative and defensive application of the CBDR

Among the major powers, Russia has adopted one of the most explicit and defensive positions. As a major producer of fossil fuels, Russia views any restrictions on primary plastic production as a direct challenge to its economic sustainability and resource sovereignty (Ferris, 2023). Its official position is that the treaty should aim at “addressing plastic pollution rather than plastic production itself.” (Russia, 2023). Russia’s invocation of CBDR serves this core objective of resisting upstream controls. It argues that the treaty should follow a “bottom-up” model in which states voluntarily determine reduction targets according to national circumstances, and it firmly rejects any global bans or phased reduction schemes. Russia further contends that restrictions on raw material extraction or polymer production exceed the mandate of UNEA Resolution 5/14, linking these proposals to broader issues of the right to development and human rights. This defensive and highly instrumental interpretation of CBDR is designed to minimize the constraints that a plastic treaty could impose on its domestic petrochemical sector (Nielsen et al., 2020).

3.2 Regional practices of CBDR in marine plastic pollution governance

Regional cooperation frameworks for marine plastic pollution have developed distinctive models of differentiated responsibility. These arrangements provide diverse paradigms of practice that can inform both reform and adaptation of CBDR within the context of a global plastics treaty.

3.2.1 The Northeast Atlantic: peer-based common responsibility

The Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR) is composed mainly of European developed states with similar historical, cultural, economic, and technological backgrounds (About OSPAR, n.d.). As such, its governance model does not reflect CBDR in the traditional sense of North–South differentiation. Instead, it embodies a model of “peer-based common responsibility.” All contracting parties share general obligations to prevent and eliminate pollution, guided by widely accepted principles such as the polluter pays principle and the precautionary principle (Convention text, n.d.). OSPAR’s governance operates through binding decisions, recommendations, and agreements that establish concrete measures to address specific environmental challenges (The OSPAR acquis: Decisions, recommendations & agreements, n.d.). Instruments such as the Decision to Prohibit the Dumping and Leaving of Offshore Installations and the Regional Action Plan on Marine Litter provide a collective framework for coordinated action against marine plastic pollution, including specific reduction targets and obligations for all members (OSPAR Commission, 2023). Within this framework, differentiation is not the central concern; rather, cooperation and coordination form the core of governance. The OSPAR experience demonstrates that when parties share similar historical contexts, governance capacities, and conceptions of responsibility, it is possible to establish a strong regime based on common binding obligations. At the same time, it highlights the difficulty of achieving such homogeneity at the global level (Matz-Lück and Fuchs, 2014).

3.2.2 The Mediterranean: a North–South hybrid approach

The Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution (Barcelona Convention) and its seven protocols form the legal foundation for environmental protection and management in the Mediterranean region. With respect to marine plastic pollution, five protocols are relevant, and governance is operationalized through supplementary strategies and regulatory tools. Under Article 15 of the Protocol for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution from Land-Based Sources and Activities (LBS Protocol), the Regional Plan on Marine Litter establishes legally binding measures and timelines for implementation (Karakus, 2023). These measures aim to prevent marine litter from entering the marine environment and to remove existing litter as much as possible, thereby minimizing its quantity and impact on the Mediterranean ecosystem (UNEP, 2017b). In 2021, COP 22 adopted an updated Regional Plan that placed greater emphasis on preventive approaches and circular economy strategies to combat marine litter. The Mediterranean region features a typical North–South composition, with developed states along the northern shores and developing countries along the southern shores. The application of CBDR here takes the form of a hybrid model. On one side, all contracting parties accept the core reduction obligations under the Regional Plan. On the other side, the implementation of projects and fulfilment of treaty obligations relies heavily on external funding, technological assistance, and capacity-building support, particularly through initiatives such as the EU- and UNEP-funded Marine Litter MED Project. This model acknowledges the financial and technological limitations of developing states and seeks to bridge the capacity gap through project-based cooperation. However, the effectiveness of this governance model remains highly dependent on the sustained commitment of donor states and institutions.

3.2.3 East Asian Seas: capacity-building orientation

The Bangkok Declaration on Combating Marine Debris in the ASEAN Region, the ASEAN Regional Action Plan for Combating Marine Debris (2021–2025), the Regional Action Plan on Marine Litter (RAP MALI) under the Coordinating Body on the Seas of East Asia (COBSEA), and the Northwest Pacific Action Plan (NOWPAP) all share common features. They emphasize cooperation, information sharing, capacity-building, and voluntary national actions rather than imposing legally binding reduction targets. These frameworks broadly recognize the transboundary nature of marine debris and call for regional collaboration. However, most of the measures are recommendatory, encouraging member states to develop and implement national-level policies according to their own circumstances. For instance, the ASEAN framework recommends long-term waste management strategies and circular economy approaches, while the revised 2019 COBSEA RAP provides guidance for collective action across East Asian seas (UNEP, n.d.). The application of CBDR in this regional context does not require certain states to assume stricter or higher-standard obligations. Instead, it functions through regional cooperation platforms that provide knowledge, technology, and policy support to less capable states, thereby gradually enhancing the overall governance capacity of the region (Ng et al., 2023). This represents a typical “empowerment-oriented” model of CBDR in practice, characterized by incremental improvement rather than rigid one-size-fits-all obligations, and reflecting a relatively flexible approach to differentiated responsibilities.

3.2.4 The wider Caribbean region: vulnerability-oriented practice

Marine plastic governance in the Wider Caribbean Region is anchored in the Cartagena Convention and its protocols. The region encompasses a large number of Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and the practice of CBDR here reflects a strong recognition of particular vulnerabilities. The Protocol Concerning Pollution from Land-Based Sources and Activities (LBS Protocol) provides the legal framework for addressing land-based pollution, including plastics (Graham, 2024). Its implementation includes establishing a regional platform to improve the management of priority pollutants, launching the Caribbean Clean Seas Campaign to tackle marine litter and plastics, and initiating the GEF-funded LAC Cities Project on circular economy networks in March 2025 (UNEP, 2017a). The operational logic of this mechanism is to set common regional goals while prioritizing support for member states, particularly SIDS with limited capacity, in fulfilling their obligations under the protocol. Assistance covers policy development, financing, legislative drafting, and technical support, as exemplified by initiatives such as the PROMAR project (PROMAR, n.d.). The application of CBDR in this context uses vulnerability as the central dimension of differentiation. Through institutional support, external assistance, and regional cooperation, the framework aims to bridge capacity gaps for weaker states, ensuring their effective participation in and benefit from the regional governance process. Within the Caribbean context, a comparable approach can be seen in the GEF-funded Integrated Waste Management Project in Saint Lucia and Grenada, which combines financial support, institutional capacity-building, and legal reform to address marine litter and strengthen national resilience (GEF, 2024).

3.3 Multilateral rules practices of CBDR in marine plastic pollution governance

Before the conclusion of a global plastics treaty, the international community had already adopted several multilateral environmental agreements addressing aspects of marine plastic pollution. These instruments reveal diverse approaches to CBDR, highlighting the principle’s limitations in practice.

3.3.1 MARPOL annex V: universal prohibition and capacity gaps

Annex V of the International Convention for Preventing Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) is the core international legal instrument regulating ship-source garbage pollution. The definition of garbage under Annex V includes all plastics in any form, and the annex expressly prohibits their discharge into the sea. The annex applies to all types of ships and designates certain “special areas” where even stricter discharge restrictions apply (International Maritime Organization (IMO), n.d.).

The responsibility model is a universal obligation, requiring all parties to ensure that vessels under their jurisdiction comply with the prohibition. In practice, however, this universal framework has revealed deep inequalities. Effective implementation of Annex V depends on port states providing adequate and convenient reception facilities. Although the convention legally obliges parties to ensure such facilities, many developing states lack the financial and technical resources to comply, resulting in inadequate or poorly managed facilities (UNEP, 2018). This creates strong incentives for illegal discharges by ships calling at their ports. The universal prohibition under Annex V thus fails to provide differentiated support for developing states. While imposing a uniform high standard in law, it neglects the disparities in implementation capacity, producing a wide gap between formal obligations and actual compliance. This shortcoming directly reflects the absence of adequate consideration for the “respective capabilities” component of CBDR.

3.3.2 The London convention and protocol: a top-down prohibition model

The London Convention and its Protocol aim to prevent marine pollution by regulating dumping at sea. Under its “black list” approach, the convention explicitly prohibits dumping “persistent plastics and other persistent synthetic materials.” The 1996 Protocol introduced an even stricter “reverse list” method, banning the dumping of all wastes unless explicitly listed as permissible. However, neither the convention nor its protocol contains explicit provisions on CBDR. Their responsibility model relies on uniform obligations, requiring all parties to comply with identical prohibitions without accounting for waste generation or management capacity differences. This one-size-fits-all approach offers a practical historical reference point for analyzing the evolution of CBDR. It demonstrates that legal frameworks lacking differentiation may be ill-suited for complex global problems such as plastic pollution, which are deeply linked to levels of development, consumption patterns, and infrastructure capacity. For instance, several developing coastal states, such as Ghana and Indonesia, have struggled to implement the strict dumping prohibition due to limited waste treatment infrastructure and enforcement capacity, leading to continued illegal discharges despite formal compliance with the Convention. This illustrates how uniform legal obligations, when detached from capacity considerations, may undermine both compliance and environmental effectiveness (Hui et al., 2025).

3.3.3 The Basel convention: procedural differentiation

The Basel Convention’s Plastic Waste Amendments brought most categories of plastic waste under the prior informed consent (PIC) procedure. Exporting states must now obtain explicit written consent from importing and transit states before shipping controlled plastic wastes. This amendment represents a significant application of CBDR in practice. Through the PIC process, importing states (often developing countries) are empowered to refuse shipments of wastes they cannot manage in an environmentally sound manner, thus protecting themselves from the harmful effects of transboundary pollution (Islam, 2020).

In addition, the amendment provides for supportive measures, particularly for developing countries, to strengthen their capacity to implement the new obligations. In this way, CBDR is reflected not in the substantive content of commitments, but in procedural and implementation rights. This highlights the principle’s flexibility and its potential for diverse applications.

3.3.4 The Stockholm and Rotterdam conventions: typical models of CBDR

The Stockholm Convention indirectly regulates the life cycle of plastics by listing chemicals used as plastic additives, such as certain brominated flame retardants and UV stabilizers, in its annexes. The convention embodies CBDR by requiring developed countries to provide new and additional financial and technological assistance to developing countries to support their compliance with obligations to eliminate persistent organic pollutants (POPs). This represents a classic application of CBDR, where support is differentiated according to capacity and responsibility.

The Rotterdam Convention similarly promotes shared responsibility and cooperation in the trade of hazardous chemicals. Chemicals listed in Annex III, which includes substances relevant to plastics, may only be exported with the prior informed consent of the importing party (ENB, 2025). This procedural safeguard provides developing countries with the right to protect themselves against unwanted risks. The Stockholm and Rotterdam Conventions illustrate a combined model of differentiated support and procedural guarantees, offering a valuable foundation for future synergies between a global plastics treaty and the governance of plastic-related chemicals.

4 Challenges in applying the CBDR principle to global governance of marine plastic pollution

Drawing on the analysis of CBDR practices at national, regional, and multilateral levels, this section examines the key challenges to applying the principle in the governance of plastic pollution.

4.1 Instrumentalization of CBDR: geopolitical and economic interests

One of the most profound challenges is the instrumentalization of CBDR in the plastics treaty negotiations, where the principle has been used as a rhetorical tool to defend core economic and geopolitical interests rather than to advance environmental solutions. First, CBDR has become a proxy for protecting industrial and economic interests. For oil-producing countries such as Saudi Arabia and Russia, plastics represent a strategic alternative to fossil fuels in the context of the global energy transition (Banjo and Lowery, 2024), as demand for fossil fuels as energy sources peaks and declines, converting oil and gas into plastics and other petrochemical products has become a crucial strategy for maintaining revenues and sustaining core industries (Davies et al., 2025). These states’ opposition to production controls is therefore less about defending the developmental rights of the Global South and more about safeguarding their economic lifelines. CBDR is reframed as an expression of resource sovereignty and development rights, serving as a defensive strategy to block international regulation that could threaten their petrochemical sectors. This instrumental use of CBDR has diverted negotiations away from environmental effectiveness and turned them into a contest over economic interests, with the heavy presence of fossil fuel and petrochemical lobbyists further undermining credibility.

Second, CBDR has been drawn into the sphere of geopolitical rivalry (Dauvergne et al., 2025). During heightened global conflict, economic competition, and the rise of unilateralism and protectionism, major powers such as the United States have used tariffs and regulatory frameworks as strategic tools to advance their interests. This has deepened global mistrust in multilateral cooperation, making plastics treaty negotiations even more difficult. Since the interpretation and application of CBDR directly shape the scope and content of states’ obligations, divergent understandings have become a matter of negotiating power and influence, reinforcing its role as a geopolitical instrument.

4.2 Contradictions in differentiation: empowerment versus exemption

The central controversy surrounding differentiation under the CBDR principle lies in whether it should function as an empowerment mechanism designed to help all states ultimately achieve common goals, or as an exemption that allows certain states to avoid core obligations (Voigt and Ferreira, 2016). The empowerment approach, advocated by the High Ambition Coalition and most developing countries, particularly Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and the African Group, holds that differentiation should be expressed through longer compliance periods and sufficient means of implementation, including financing and technology transfer. The objective is to ensure that all states eventually meet a uniform and legally binding global standard, such as a worldwide reduction target for primary plastic production. This interpretation draws inspiration from the successful experience of the Montreal Protocol, which combined common obligations with differentiated support measures (Kirk, 2020). By contrast, the exemption approach is advanced by the Like-Minded Group, which pushes differentiation to the extreme by interpreting it as a right to be exempt from obligations on the basis of sovereignty and national circumstances. This position rejects any form of global upstream production control and instead calls for nationally determined action plans in a bottom-up manner. While framed as drawing on the model of the Paris Agreement, this approach is in fact weaker, since it not only supports voluntary nationally determined contributions but also seeks to exclude production control measures entirely from the legally binding scope of the treaty.

The conflict between these two models has produced draft texts filled with contradictory options. For example, provisions on production control simultaneously include alternatives for establishing a global reduction target, adopting nationally determined targets, or including no text at all. This fundamental divide over the application of differentiation under CBDR has paralyzed the treaty’s institutional design and significantly delayed progress in global plastic pollution governance.

4.3 Outdated categories: the problem of a binary divide

The traditional application of CBDR rests on a binary division between “developed” and “developing” countries. In today’s multipolar world, this division is increasingly detached from reality and has become an obstacle in plastics governance. Although such binary distinctions have gained wide acceptance in some fields of international governance, such as trade and intellectual property, they cannot be uncritically transposed across different domains. The criteria for differentiation must be sector-specific, yet the conventional divide fails to align with contemporary indicators of national capacity and responsibility. It neither reflects the current configuration of the international political economy nor corresponds to the realities of plastic production and pollution contributions, leading to structural distortions in responsibility allocation.

China illustrates this dilemma. As the world’s largest plastics producer and a major economy with strong financial and technological capacity, it emphasizes its identity as a developing country to demand historical accountability and financial support from developed states. At the same time, it aligns with the LMG to oppose binding global production reduction targets on the grounds of sovereignty and national circumstances. This dual position creates a governance deadlock. Developed countries resist contributing significant financial resources to a mechanism that does not equally bind the largest producer. In contrast, other developing countries are weakened in their push for upstream controls without China’s full support. This rigidity reveals the need for a more dynamic differentiation mechanism, in which responsibilities evolve according to changing economic capacities, governance abilities, and pollution contributions. However, any proposals to revise categories or introduce “graduation” mechanisms face strong opposition from emerging economies, as such measures challenge their negotiating positions and reduce their policy space in international governance.

4.4 Conflicts of interpretation: the debate over responsibility

The core of the CBDR principle is a differentiated allocation of responsibilities based on historical contribution and capability. In the case of plastic pollution, however, the definition of historical contribution lacks solid scientific grounding and persuasive legitimacy. The conflicts over how to understand and apply CBDR are not a mere technical dispute. They concern the ontology of the problem itself.

First, there is a disjunction between historical and current responsibility, together with a selective grafting of arguments. Developed states represented by the European Union acknowledge in principle their historical role in global environmental harm during industrialization. In the plastics context, they place greater weight on the urgency and universality of present challenges. They argue that all states, especially current major producers, should assume binding common obligations such as reducing the production of primary plastic polymers. Their logic is that historical responsibility should lead to effective collective action and avoid the delays seen in climate governance that stem from burden shifting. By contrast, the Like-Minded Group led by Saudi Arabia and Russia has grafted CBDR onto a different strategy. On the one hand, they invoke historical responsibility to demand large-scale and unconditional financial and technological support from developed states. On the other hand, they use CBDR as a shield to reject any upstream obligations that would limit current or future plastics industries, and they claim that such measures fall outside the mandate of UNEA Resolution 5/14.

Second, there is a deliberate conflation and transfer between state responsibility and corporate responsibility. LMG states frame plastic pollution primarily as a problem of downstream mismanagement of waste rather than upstream overproduction. In doing so, they shift the burden from producers and producing states to consumers and to states with weaker waste management capacity. Their core message that “plastics are not pollutants; pollution results from improper handling after disposal” has been repeatedly advanced in the negotiations. This narrative minimizes responsibility at the stages of raw material extraction and production, and it locks the focus of governance onto the weakest end of the chain, where developing countries most need support. As a result, the polluter pays principle is hard to implement because the identity of the polluter is blurred at the source.

These fundamental conflicts over responsibility have pushed the negotiations toward theoretical debate rather than practical cooperation. One camp locates responsibility at the point of production, while the other places it at the point of waste. With this basic divide over the origin of the problem, discussions of core obligations cannot move forward.

4.5 Deadlock over means of implementation: finance as the ultimate fault line

Debates over means of implementation, particularly the financing mechanism, represent the ultimate manifestation of all the preceding disagreements. Developing countries have consistently demanded the establishment of an independent fund financed through mandatory contributions from developed states as a precondition for their compliance with treaty obligations. This demand stems directly from the traditional interpretation of CBDR, grounded in historical responsibility, national circumstances, and differentiated capacities. In contrast, developed states have favored a blended financing model (Jawed and Bose, 2025). They advocate reliance on existing mechanisms such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and emphasize the mobilization of private and domestic resources. This position reflects not only a desire to avoid further fragmentation of the international financial architecture but also a reluctance to assume unlimited, binding obligations—particularly in circumstances where major emerging economies and leading producer states refuse to undertake equivalent commitments.

Proposals for innovative financing mechanisms, such as a polymer levy, have been presented as effective ways to operationalize the polluter pays principle. A polymer levy refers to a levy imposed on enterprises engaged in the production of plastic polymers within the jurisdiction of the Convention. States Parties producing such polymers would be required to collect taxes based on the quantity of polymers manufactured. Depending on national circumstances, a portion of the revenues may be retained domestically for administrative or other designated purposes. The remaining funds shall be contributed to a global fund aimed at addressing legacy pollution and supporting other objectives outlined in this instrument (UNEP, 2024a). Yet such measures have faced strong resistance from the Like-Minded Group (LMG), which views them as a direct encroachment on producer responsibility and national fiscal sovereignty. The stalemate on finance is therefore not a mere technical or quantitative issue but a direct reflection of the fundamental divide over who should bear responsibility and in what form. As long as no consensus can be reached on the boundary between minimum common obligations and differentiated implementation measures, discussions over the form and substance of responsibility will remain deadlocked.

In conclusion, the application of CBDR in global plastics governance has become ensnared in a Gordian knot composed of instrumentalization, conflicting models, outdated classifications, interpretive disputes, and financial deadlock. This is not only a challenge for the CBDR principle in addressing emerging global problems but also a broader reflection of the difficulties facing multilateralism in today’s geopolitical landscape.

5 Innovative applications of the CBDR principle in global governance of marine plastic pollution

The current deadlock in negotiations on a global plastics treaty stems from rigid interpretations of the CBDR principle, entrenched binary divisions, and its strategic misuse. Breaking this impasse requires reconceptualizing CBDR as an operational and measurable process for allocating responsibilities. First, the instrumentalization of the principle can be addressed through procedural reforms that raise the political costs of deliberate obstruction and isolate political risks. Second, the stalemate between competing models and outdated standards can be mitigated through a dynamic and tiered system of responsibility allocation. Third, a “core and flexible obligations” framework, anchored in data, can resolve competing narratives about the root causes of the problem. Finally, innovative financing mechanisms and robust monitoring systems can provide guarantees for effective implementation. However, the legal status of the Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) principle fundamentally determines the legitimacy and feasibility of proposed instruments such as a tiered system and hybrid financial mechanisms. Originally articulated as a political commitment in the 1992 Rio Declaration, CBDR has gradually evolved through its incorporation into treaties, including the UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement, and the Convention on Biological Diversity, into a general principle of international environmental law. This dual character, which combines normative guidance with flexibility in implementation, provides a legitimate foundation for differentiation-based mechanisms (Petrescu-Mag et al., 2013). Measures such as production caps or financial support schemes can therefore be justified as expressions of equity in implementation rather than as derogations from sovereign equality. However, the indeterminate legal strength of CBDR also allows divergent interpretations. Developed countries often frame it as a capacity-based support obligation, while developing countries invoke it as a rationale for exemption from new commitments. The operational value of the principle lies in interpreting fairness as equitable implementation rather than obligation exemption, ensuring that differentiation enhances rather than undermines the legal and political viability of a future Global Plastics Treaty.

5.1 Preconditions for innovative application: reforming procedural rules

For CBDR to be applied innovatively in global plastics governance, the starting point must be a negotiation process that facilitates rather than obstructs effective outcomes. The present deadlock can be attributed in part to the procedural barrier of strict consensus. Thus, the first step in reinterpreting CBDR is procedural reform aimed at improving efficiency and creating conditions for substantive agreement.

First, rules of procedure should formally establish a mechanism of last resort voting (Hillsdon, 2025). At sessions such as INC 2 and INC 5, protracted debates over whether to insist on consensus or allow voting consumed significant time and resources. This procedural uncertainty enabled low ambition groups like the Like-Minded Group (LMG) to delay substantive discussions on contentious issues such as production controls. Therefore, at the resumption of negotiations in the INC5 Follow-up Meeting, procedural rules that include a last resort voting mechanism, such as a two-thirds majority, should be placed at the top of the agenda. This would not eliminate efforts to achieve consensus but ensure that negotiations can move forward rather than stagnate when deliberate obstruction occurs. Specifically, this mechanism would be activated only after three formal negotiation rounds on a specific issue fail to produce agreement, as verified by the Chair and endorsed by at least one-third of participating states. Once triggered, decisions would be adopted by a two-thirds majority of the parties present and voting, and would apply primarily to procedural or institutional matters such as annex updates, methodologies, or compliance arrangements, rather than to substantive obligations that create new legal duties. This design ensures that negotiations cannot be indefinitely stalled by a small group of dissenting states, while maintaining fairness by allowing parties with serious implementation concerns to submit their objections to the Facilitative Compliance Committee for review and assistance.

Second, a structured negotiation format and the authority of the Chair’s text should be institutionalized. To avoid uncontrolled expansion of draft texts, chairs and co-chairs should be empowered to produce simplified documents after each negotiating round. These texts should capture the main areas of consensus and the core points of divergence and serve as the basis for subsequent discussions. Although the Chair’s text introduced at INC 5 failed in breaking the deadlock, the approach was conceptually sound. Future negotiations should strengthen the Chair’s authority to consolidate and refine texts, preventing endless debates over bracketed language.

5.2 Core of innovative application: constructing a dynamic and tiered responsibility system

The core difficulty in applying the CBDR principle to global plastics governance lies in the outdated binary division between developed and developing countries (Thérien, 2024). This framework no longer reflects states’ responsibilities and capacities in addressing plastics. To restore CBDR as a foundation of fairness, it is necessary to establish a dynamic responsibility system based on multidimensional indicators and tiered categories. Such a system aims to transform the principle from abstraction into an operational, measurable standard that can evolve.

First, the scientific design of multidimensional indicators is required (Merry, 2018). Instead of a single political identity, objective, quantifiable, and verifiable indicators should be adopted to place parties into different tiers. These indicators should capture the two core dimensions of CBDR, namely responsibility and capability. A detailed analysis of the specific metrics is provided in Table 1.

Table 1

| Category | Indicator dimension | Potential indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Responsibility | Historical Contribution | Cumulative Primary Plastic Polymer (PPP) production (e.g., since 1950) |

| Current Production | Current annual PPP production (total and per capita) | |

| Consumption and Trade | Per capita plastic consumption Net trade of plastic waste (Exports vs. Imports) |

|

| Environmental Impact | Mismanaged plastic waste leakage rate (total and per capita) | |

| Capacity | Economic Capacity | Gross National Income (GNI) per capita |

| Technical Capacity | National Waste Management & Infrastructure Index | |

| Human Development | Human Development Index (HDI) |

Detailed analysis of the indicators.

Second, a dynamic tiered mechanism should be established. Based on weighted scores of the above indicators, parties may be divided into three tiers and one special category (Voigt and Ferreira, 2016). The first tier, representing the highest level of responsibility and capability, would include states with significant historical contributions, high current levels of production and consumption, and substantial economic and technological capacity, such as most G7 members and some petrochemical producers. These states should assume the strictest obligations and the largest share of financial contributions. The second tier, representing transitional responsibility and capability, would include emerging economies such as China, India, and Brazil. These states have significant levels of production and consumption, but their per capita levels and historical contributions are relatively lower. They should assume substantive but more flexible reduction obligations and gradually increase their contributions to financial mechanisms. The third tier, representing priority support and capacity building, would include developing countries with low contributions and weak economic and technological capacity. These states should receive priority access to financial and technological support, and their obligations should be closely linked to the level of assistance received. The special category should apply to Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs), whose economic vulnerability and institutional fragility require particular consideration. Regardless of their indicator scores, they should be granted the highest levels of support and the most flexible compliance arrangements to ensure environmental justice. The key is that this tiered system must be dynamic. A global plastics treaty could establish an independent scientific and technical assessment body to review indicators every five to ten years. Based on the results, states would be reassigned to tiers. This would ensure that responsibility allocation evolves in line with changes in global economic and environmental realities.

Finally, to turn the idea of dynamic tiering into a working framework, the indicators must be combined and managed through a clear, rules-based process. The first step involves normalization and weighting, ensuring that diverse metrics such as production, waste leakage, income, and infrastructure capacity can be compared on a 0 to 1 scale. Each indicator is rescaled using a normalization method based on its minimum and maximum values. The rescaled indicators are then combined into a single Composite Index Score. The exact weighting should be decided through political negotiation by the Conference of the Parties (COP). As a starting point, an equal split, with 50 percent for Responsibility indicators and 50 percent for Capability indicators, can serve as an initial reference. This composite score would then determine each Party’s tier based on pre-defined thresholds: Tier 1 (high responsibility and capacity, >0.75), Tier 2 (transitional, 0.40–0.75), and Tier 3 (low, <0.40). To ensure the framework remains dynamic, scores must be recalculated at regular review intervals (e.g., every five years), with clear “graduation” rules guiding transitions. For instance, if a Tier 2 Party’s composite score exceeds the Tier 1 threshold for two consecutive review cycles, it automatically advances to Tier 1 and assumes correspondingly higher obligations. Conversely, persistent decline may trigger reassignment to a lower tier, subject to review. Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) should remain in a special category that guarantees maximum flexibility and dedicated support regardless of their numerical ranking, recognizing their structural vulnerabilities (Pauw et al., 2019). In terms of governance, technical and political responsibilities must be clearly delineated. The Scientific and Technical Advisory Body (STAB)—analogous to the IPCC in the climate regime—should be mandated to develop indicator methodologies, data standards, and weighting formulas. The COP is the political authority under the treaty and should formally adopt these indicators, thresholds, and any revisions through its decision-making process. This helps ensure both scientific rigor and political legitimacy. The first COP (COP1) should establish the STAB, tasking it to deliver its initial recommendations for adoption at COP2 or COP3, with updates every five years thereafter. This institutional architecture ensures that the dynamic tiering mechanism evolves through an iterative, evidence-based, and politically accountable process, translating the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities into a measurable and adaptive governance tool.

5.3 Mechanisms for innovative application: a “core and flexible” obligations framework

Soft law rules sometimes substitute for hard law to facilitate consensus and promote cooperation in the short term (Boyle, 2019). Therefore, the design of core obligations in the plastics treaty must move beyond the binary of globally uniform binding rules versus purely voluntary soft law. A mixed model of “core obligations plus differentiated pathways” is needed. This model seeks to guarantee the achievement of global environmental objectives while providing states in different tiers with compliance pathways suited to their respective capacities.

First, the treaty should establish legally binding global core obligations. To avoid the gap between ambition and reality seen in the Paris Agreement, the treaty must contain obligations binding on all parties. These should include adopting a collective target for reducing the overall production of primary plastics. This target would not be allocated directly to individual states but would serve as a collective commitment guiding national policies and measures.