Abstract

Despite ecological protections, the Mar Menor lagoon in Spain continues to experience eutrophication, leading to uncontrolled proliferation of algae such as Caulerpa prolifera. When it decomposes, it reduces oxygen and creates sludge, causing fish and other aquatic animals to suffocate. Storms and seasonal changes then wash the uprooted algae ashore, generating foul odors and sludge buildup along the lagoon’s banks. In this study, the utilization of algal beach wracks as a component of substrates for mushroom cultivation was explored, assessing their potential to replace conventional lignocellulosic materials. Rinsed algal wracks were incorporated at 20%, 40%, and 60% (dry weight) into wheat straw-based substrates (patented formula no. 202430026), supplemented with 0%, 0.63%, 2.5%, or 5% additional nutrients, to cultivate four different mushroom species: oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), king oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus eryngii), Shimeji mushroom (Hypsizygus tessulatus), and Nameko mushroom (Pholiota nameko). Proximal analysis [moisture, pH, conductivity, nitrogen, organic load, and carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio], lignocellulosic content (lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose), mushroom yield, and biological efficiency (BE) were analyzed and compared among formulations. Results demonstrated that utilizing 20% algal wracks significantly enhanced BE, with increases above 300% for H. tessulatus, 11% for P. ostreatus, and 9% for P. nameko, while P. eryngii showed similar yield and BE to the standard substrate (46.53% BE in the standard substrate compared to 48.37% in the algae-enriched substrate). These findings highlight the feasibility and environmental value of using algal beach residues as sustainable substrates for mushroom production, offering a circular bioeconomy alternative to current disposal practices in the Mar Menor region.

1 Introduction

Algal beach wrack accumulation in seas and coastal lagoons represents a growing environmental challenge, as it disrupts the ecological balance of aquatic ecosystems worldwide. This phenomenon is driven by the combined effects of climate change and various anthropogenic activities. In semi-enclosed lagoons such as the Mar Menor (Murcia, Spain), excessive nutrient inputs from agricultural runoff, groundwater discharge, and urban effluents have triggered persistent algal proliferations and the progressive decline of seagrass meadows (Álvarez-Rogel et al., 2020; Pérez-Martín, 2023; Ruiz et al., 2022). Among the most abundant species, the green macroalga (Caulerpa prolifera) has expanded rapidly (Sánchez-Fernández et al., 2025), colonizing large sandy and muddy areas formerly dominated by seagrass (Cymodocea nodosa) and other seagrass species (Bernardeau-Esteller et al., 2023; López-Ballesteros et al., 2023; IEO-CSIC, 2024). Massive accumulations of detached C. prolifera and other seaweeds along beaches and the coastal fringe have become a serious environmental and management problem. These wracks emit unpleasant odors, hinder recreational use of beaches, and entail significant removal and disposal costs for local authorities (Rodil et al., 2024).

The uncontrolled decomposition of wrack deposits can generate anoxic conditions, release greenhouse gases (CO2 and CH4), and re-mobilize nitrogen and phosphorus into the water column, enhancing eutrophic conditions (Rodil et al., 2024; Ulaski et al., 2023). This process may lead to a self-reinforcing degradation loop characterized by loss of benthic biodiversity, alteration of sediment biogeochemistry, and long-term reduction of ecosystem resilience (Liu et al., 2023; Figueroa et al., 2025). These accumulations impact tourism and fisheries, representing a recurrent burden for coastal municipalities (García-Ayllon, 2018).

The most costly mitigation strategy implemented to decelerate the eutrophication of the Mar Menor lagoon is the physical removal of beach wracks (García-Ayllon, 2018). However, this practice generates substantial quantities of organic waste, which subsequently accumulate at disposal sites where opportunities for reuse are limited. Therefore, the need for sustainable valorization alternatives for this biomass has become an urgent priority. Previous studies explored the use of marine macroalgae as feedstock for bioenergy, fertilizers, or animal feed (García-Ayllon, 2018; Vincevica-Gaile et al., 2022). Nevertheless, their potential application as a raw material for edible mushroom cultivation remains poorly investigated.

Mushroom cultivation is an established agricultural industry with several benefits for society. Besides providing local job opportunities, it is a circular process, since it makes use of by-products from other agricultural activities. Moreover, mushroom cultivation provides a nutrient-rich edible product that is beneficial for human health, due to either its nutritional characteristics (e.g., high protein and fiber content) or its medicinal properties (e.g., anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antimicrobial) (Valverde et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2025), and ensures that the food produced is safe for consumers (Sangeeta et al., 2024).

Commercial-scale cultivation of edible mushrooms mainly relied on the selection and proper preparation of substrates. These substrates should provide all nutrients needed by the mycelium (the vegetative part of the mushroom) in a form that can be absorbed by their hyphae since it will play a crucial role determining the yield, quality, and overall success of their cultivation (Padamini et al., 2024). Most edible mushroom species can uptake these nutrients from several biological materials (Assan et al., 2014). These materials usually have included lignocellulose and a high nitrogen content, as they are key components for fungal growth (Hoa et al., 2015). Therefore, the carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio was an important factor in mushroom cultivation influencing not only mycelial growth but also mushroom weight, yields, and fruiting bodies’ protein content (Kumla et al., 2020). Manure (for Agaricus bisporus), other organic nitrogen supplements (cereal bran, cereal husks, and soybean meal), or inorganic supplements (ammonium chloride and urea) are incorporated to ensure an optimal C/N ratio (Ragunathan and Swaminathan, 2003; Cueva et al., 2017). The selection of raw materials and supplements for substrate formulation is determined by their long-term regional availability (Jayaraman et al., 2024; Cueva et al., 2017). In Spain, wheat straw, chicken manure, and oak chips (Quercus falcata) were used most frequently due to their abundance and affordable cost (Goglio et al., 2024).

In recent years, the lack of precipitation in the Iberian Peninsula resulted in dramatically drought stresses in plants and vegetables, including wheat, oak, and corn, leading to an increase in their by-product prices because of the large crop reduction and losses (Nyaupane et al., 2024). In those years, mushroom growers were even forced to import these products from other countries, increasing the production costs and leaving them with no or extremely low benefit, requiring governmental help to survive (Díez, 2024).

Macroalgae contained diverse polysaccharides (cellulose, hemicellulose, xylan, galactan, and sulfated heteroglycans) and mineral elements (Ca, Fe, K, and Mg) that could enhance substrate quality for mushroom cultivation (Mamede et al., 2023). Their incorporation into lignocellulosic matrices might have improved water retention, porosity, and nutrient availability, supporting the growth of basidiomycetes (Ravlikovsky et al., 2024). Moreover, the conversion of macroalgal residues into productive substrates has always aligned with the principles of the circular bioeconomy and the European Union’s Green Deal objectives, contributing to waste reduction and resource efficiency (Brito-López et al., 2025).

The mushroom species of the study were selected after primarily in vitro experiments where the mycelial growth rate of 12 different species were assayed on plates containing algae-enriched media (Lavega et al., 2023), and they were the species that showed more promising growth performance. Additionally, their relevance to the mushroom cultivation sector in La Rioja (Spain) was considered. Pleurotus ostreatus is currently the second most widely cultivated mushroom in the region, while Pleurotus eryngii is showing a rapidly increasing cultivation trend, reflecting its increasing economic importance (Mendiola Lanao, 2017; Lavega González, 2023).

Therefore, in this work, the four mushroom species selected were oyster mushroom (P. ostreatus), king oyster mushroom (P. eryngii), Shimeji mushroom (Hypsizygus tessulatus) and Nameko mushroom (Pholiota nameko). These fungi were cultivated using substrates formulated with algal wracks. A partial substitution of conventional lignocellulosic materials was tested in several substrate formulations.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Biological materials

Commercial mycelia of Shimeji (H. tessulatus) (Bull.) Singer (HT), Nameko (P. nameko) (T. Itô) S. Imai (PN), and king oyster mushroom (P. eryngii) (DC: Fr.) Quel. (PE) were obtained from mycelia (Deinze, Belgium), and oyster mushroom (P. ostreatus) (Jacq.Ex Fr.) Kummer (PO) was purchased from Micelios Fungisem (Autol, Spain).

Algal beach wracks, algae strandings, or algae clumps from the Mar Menor lagoon (Murcia, Spain) were a mixture of mainly C. prolifera (Forsskal) Lamouroux, followed by C. nodosa (Ruiz et al., 2020; Bernardeau-Esteller et al., 2023; Belando et al., 2021). Another minor algal species present in the clumps were Ruppia cirrhosa, Cystoseira sp., Laurencia obtusa, Lophocladia lallemandii, and filamentous algae (named in Spanish “ova”) that bloomed on the lagoon shore after releasing agricultural fresh waters from nearby fields (Ulothrix sp., Ulva prolifera, Cladophora sp., etc.) (Lombardo et al., 2025).

Wheat grains (Triticum spp.), wheat straw (Triticum spp.), oak chips (Q. falcata), oat (Avena sativa), soybean (Glycine max) flour powder, and corn (Zea mays) kernels were collected from local producers in La Rioja and Navarra (Spain). These agricultural by-products used in the study were obtained during the harvest periods. Commercial carbocal (AB Azucarera Iberia, Spain) was utilized to adjust the pH of the mixture and optimize the mineral content of various substrates.

2.2 Sample collection and preparation

Algal wracks were manually collected from the seashore of the Mar Menor lagoon. The algal wracks were transferred into truck containers and transported to an authorized recycling facility located near the lagoon. The algal material was manually distributed over cotton fabric sheets (33.6 m²) in uniform layers not exceeding 15 cm in thickness to ensure adequate aeration and prevent compaction. The algal wracks were sun-dried to constant weight ≤20% moisture). After drying, the algal wracks were packed in 1-m³ bulk bags and transported to the Mushroom Technological Centre (CTICH) in La Rioja, Spain. Prior to use, approximately 150 kg of dried algal wracks was rinsed for 3 min, three times in 500-L batches of clean fresh water to remove residual salts and surface impurities.

Dried wheat straw was subsequently chopped into small fragments, whereas wheat grains, oak chips, oat, and corn kernels were ground to a homogeneous particle size suitable for substrate formulation. All processed materials, including the rinsed algal biomass, were stored under ambient conditions in a dry, shaded environment until subsequent use.

2.3 Substrate formulation and mushroom cultivation

Experimental treatments (Table 1) were formulated and patented (Soler Rivas et al., 2024) to evaluate the effect of incorporating different proportions of algal wrack [0%, 20%, 40%, and 60% dry weight (dw)] and nutritional supplements (0%, 0.63%, 2.5%, and 7.5% dw) on mushroom productivity and substrate performance of four species: P. ostreatus, P. eryngii, P. nameko, and H. tessulatus. Each treatment was prepared as an independent batch of cultivation bags, with batch numbers shown in Table 1 (between parentheses). To evaluate the effect of residual salinity, some substrates incorporated non-rinsed algal material. Supplementations were blends of ground cereals and lignocellulosic ingredients (e.g., oat seeds, soybean flour powder, corn kernels, and wheat kernels). Tested ratios were expressed on a dry weight basis.

Table 1

| Mushroom species | Algal wrack (% dw) | Supplements (% dw) | Substrate (% dw) | Number of bags (number of batch) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. ostreatus | 0 | 0 | 100 (wheat straw) | 89 (1) |

| 20 (non-rinsed) | 0 | 80 | 89 (1) | |

| 20 | 0 | 80 | 75 (1) | |

| 20 | 2.5 | 77.5 | 68 (1) | |

| 40 | 2.5 | 57.5 | 59 (1) | |

| 60 | 2.5 | 37.5 | 56 (1) | |

| 20 | 5 | 75 | 59 (1) | |

| 40 | 5 | 55 | 55 (1) | |

| 60 | 5 | 35 | 56 (1) | |

| 0 | 0.63 | 99.37 | 120 (1) | |

| 20 | 0.63 | 79.37 | 129 (1) | |

| P. eryngii | 0 | 5 | 95 (oak chips and wheat straw) | 162 (2) |

| 20 | 5 | 75 | 182 (2) | |

| 0 | 7.5 | 92.5 | 162 (2) | |

| 20 | 7.5 | 72.5 | 129 (2) | |

| P. nameko | 0 | 7.5 | 92.5 (oak chips and wheat straw) | 95 (1) |

| 20 | 7.5 | 72.5 | 68 (1) | |

| H. tessulatus | 0 | 7.5 | 92.5 (oak chips and wheat straw) | 73 (1) |

| 20 | 7.5 | 72.5 | 67 (1) |

Concentration of algal wrack and supplements used to design substrates for cultivation of four mushroom species and number of bags prepared per experimental trial.

The different dry material mixtures were soaked in water until a final moisture content of 70%–75% (Binder ED400) is reached and placed into polypropylene bags (20 × 12 × 50 mm) with a 5-µm filter (Unicornbags). Once the bags were filled with 2.8 kg of substrate, they were sterilized at 121°C for 3 h, as it included wheat grains and corn kernels, to guarantee the elimination of all the possible contaminants. When substrates cooled down, they were aseptically inoculated with mushroom spawn (1% w/w substrate) by spreading it on the substrates.

Once the substrates were inoculated with the spawn, they were incubated until primordia formation was inducted and fruiting was achieved as indicated in Table 2. Each mushroom required specific conditions of temperature, humidity, CO2 concentration, and light as well as a different number of days in each stage (Table 2). Incubation rooms were precisely controlled with multiple sensors (Fancom temperature sensor SF-7, RH sensor Fancom Set L/N T05726, and Fancom 4270025 CO2 sensor from Fancom, Panningen, The Netherlands) and nebulizers being continuously monitored by a specific software (Fancom, Panningen, The Netherlands).

Table 2

| Process | Conditions | P. ostreatus | P. eryngii | H. tessulatus | P. nameko |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation | Room temperature | 20–22°C | 23–25°C | 23°C | 23°C |

| Substrate temp. | 25–30°C | 25–28°C | 25°C | 25°C | |

| Incubation time | 19–22 days | 10–15 days | 20 days | 16–19 days | |

| Primordia induction | (Night time) * temp. | <11–15°C | <18°C | 18–24°C | 18–24°C |

| Relative humidity | 90%–95% | 95%–97% | 90%–95% | 90%–95% | |

| Fruiting conditions | Room temperature | 10–17°C | 12–15°C | 13–18°C | 18–28°C |

| Relative humidity | 85% | 95%–97% | 90% | 85%–90% | |

| CO2 concentration | <1,000 ppm | <1,200 ppm | 2,000–3,000 ppm | 1,000 ppm | |

| Light | 800–1,500 lux | 800–1,500 lux | 500–1,000 lux | <500 lux |

Conditions selected during the different cultivation steps for the assayed mushroom species.

2.4 Analysis of mushroom yield and biological efficiency

Fruiting bodies were harvested at the species-specific maturity stage and immediately weighed to determine total yield and biological efficiency (BE). Yield was expressed as the ratio of fresh mushroom weight to the initial substrate weight. BE (%) was calculated as the percentage ratio of the fresh weight of harvested mushrooms to the dry weight of the substrate used for cultivation, according to the formula:

2.5 Proximate analysis

Moisture was determined by heating the sample at 70°C for 24 h to a constant mass on a Binder ED400 oven (Merck, Germany); ammonium content was measured by collecting distilled ammonia in boric acid and titrating the mixture with a standard acid H2SO4 solution using a FOSS, Kjeltec 8100 Tecator line (Denmark); pH was determined with a CRISON pH meter (GLP 21-22, Spain); and conductivity was measured with a CRISON conductometer (GLP 31, Spain) according to standard procedures (AOAC, 2000) in freshly raw materials and prepared substrates as described in Lavega et al. (2023). The nitrogen and organic content were analyzed in substrate samples oven-dried at 70°C for 16 h (Binder ED400) and ground and sieved until particles of <1 mm were obtained (FOSS, CT 293 Cyclotec, Denmark). Carbon (C) content was assessed according to an established method (Royse and Sanchez, 2007). The Kjeldhal method was used to determine the total nitrogen (N) content of each substrate. The C/N ratio of each substrate was then calculated.

2.6 Quantification of lignin and complex carbohydrates

The procedure for the determination of neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), and lignin from dry compost and casing used was adapted from standardized methodology (van Soest et al., 1991). For the quantification of the lignin and carbohydrate content, Fibertec™ 8000 (Foss, Denmark) was used. The amount of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and other macromolecules (such as cutin) was initially calculated from 0.5 to 1 g of dry sample (W1; dm = dry matter) prepared in a crucible. To estimate the NDF amount, samples were dissolved in 100 mL of neutral detergent solution and 0.5 mL of antifoam agent (1‐octanol) (van Soest et al., 1991). Samples were subsequently subjected to vacuum filtration and washed three times with distilled water and finally with acetone. Dry samples were weighed (W2) and calcinated in a muffle furnace at 520°C (W3). The proportion of the original sample corresponding to NDF was calculated using the following equation:

ADF was calculated from 0.5 to 1 g of dry sample (W4) dissolved in 100 mL of acid detergent solution and 0.5 mL of antifoam agent (1‐octanol) as described above. The dry sample (W5) was subsequently calcinated (W6). This process dissolves hemicellulose and allows cellulose, lignin, and cutin content to be estimated using the following equation:

Finally, the ADF residue was digested with concentrated sulfuric acid (72%) to degrade cellulose and cutin (W7). The organic fraction remaining corresponding to the lignin content was calculated following calcination of this sample (W8).

2.7 Statistical analysis

The analysis used the Statgraphics Centurion XVII software (version 19.3) to compare the outputs. The initial step involved conducting an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess differences among various groups. If the data satisfied the assumptions of normality and equal variance, Tukey’s test was employed for post-hoc comparisons at a 5% significance level. For datasets that did not meet these assumptions, non-parametric methods, such as the Kruskal–Wallis test or Mann–Whitney U test, were applied to compare medians at a 95% confidence level.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Influence of wrack addition on the physicochemical characteristics of the formulated substrates

Biological materials intended for mushroom substrate formulation must satisfy specific physicochemical criteria to ensure efficient mycelial growth and fruiting. For P. ostreatus cultivation, substrate moisture was maintained at 65%–75%, the C/N ratio was adjusted to 30–60, the pH was controlled between 5 and 7.5, and electrical conductivity (EC) was kept below 4 mS/cm (Gebru et al., 2024). Slight variations in substrate requirements had been reported for other species; for instance, the optimal C/N ratio for P. nameko ranged from 40 to 85 (Meng et al., 2019), while organic matter contents exceeding 85% were considered desirable for H. tessulatus (Lin et al., 2023). Accordingly, key parameters, including moisture, total nitrogen (N), C/N ratio, pH, EC, and organic matter, were analyzed in multiple raw materials, including algal wracks, to evaluate their suitability as substrates (Oei, 2005).

Moisture content was generally consistent among the materials (Table 3), with the exception of oak chips and rinsed algal wracks, which exhibited considerably higher water retention. Nitrogen levels were found to be highest in soybean meal, followed by algal wracks and wheat kernels, indicating that algal wracks represent a valuable nitrogen source comparable to other traditional supplements such as corn kernels or oat seeds (Sainos et al., 2006). However, their organic content was observed to be up to 30% lower, in agreement with previous reports showing that both fresh C. prolifera and its algal residue contain high ash levels (up to 30%) (Inoubli et al., 2024; Lavega et al., 2023), highlighting the necessity for increased supplementation when formulating substrates to achieve organic matter values exceeding 85%. Additionally, algal wracks were characterized by elevated pH and EC values, particularly in non-rinsed samples, attributable to the hypersaline nature of the biomass (Oosterbaan et al., 2025). Consequently, a rinsing step is recommended prior to their use in substrate formulation to prevent salt-induced stress on mycelial growth. Furthermore, the C/N ratio of algal wracks was found to be similar to that of poultry manure (Hachicha et al., 2008; Gao et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014), a material commonly employed to enhance compost composition for A. bisporus cultivation, suggesting that algal wracks could serve as a nitrogen-rich additive (Thai et al., 2022; Geng et al., 2024).

Table 3

| Raw material | Moisture (%) | Nitrogen (%) | Organic content (%) | pH | Conductivity (mS/cm) | C/N ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algal wracks non-rinsed | 15.7 ± 13.82a | 3.25 ± 0.16c | 67.55 ± 4.75ab | 7.04 ± 0.36c | 24.91 ± 4.23b | 12.09 ± 1.00a |

| Algal wracks rinsed | 20.65 ± 18.71a | 2.94 ± 1.63bc | 62.95 ± 30.30a | 7.74 ± 0.45d | 8.8 ± 7.93a | 13.07 ± 1.84a |

| Oat seeds | 11.31 ± 0.15a | 1.61 ± 0.37ab | 96.96 ± 0.9bc | 6.44 ± 0.04b | 0.9 ± 0.09a | 35.96 ± 8.11b |

| Soybean meal | 11.68 ± 1.70a | 8.12 ± 0.1d | 92.46 ± 0.,635abc | 6.1 ± 0.07b | 3.8 ± 0.35a | 6.61 ± 0.22a |

| Corn kernels | 13.86 ± 0.01a | 1.4 ± 0.02ab | 98.41 ± 0.18c | 6.15 ± 0.07b | 0.76 ± 0.20a | 40.78 ± 0.43b |

| Wheat kernels | 12.96 ± 0.20a | 2.17 ± 0.03abc | 98.22 ± 0.15c | 6.46 ± 0.01b | 0.62 ± 0.10a | 26.2 ± 0.37b |

| Wheat straw | 11.45 ± 1.84a | 0.67 ± 0.02a | 94.99 ± 0.19bc | 6.69 ± 0.10bc | 1.67 ± 0.70a | 82.59 ± 2.14c |

| Oak chips | 32.97 ± 19.67a | 0.17 ± 0.01a | 97.91 ± 2.01c | 3.46 ± 0.13a | 1.41 ± 1.71a | 327.03 ± 30.07d |

Physical chemical parameters of the different biological materials used to formulate mushroom substrates (mean ± standard deviation). .

Different letters indicate significant differences between materials according to the results of post-hoc Tukey’s test for the biological variables (n = 3, p < 0.05).

Based on these results, mixtures were formulated to cultivate P. ostreatus, P. eryngii, H. tessulatus, and P. nameko (Table 4). Moisture levels were influenced mainly by supplement concentrations, while total nitrogen increased significantly in substrates containing algal wracks for P. ostreatus and P. eryngii. Organic matter content remained similar in most formulations, with slightly lower values when only algal wracks were added but within standardized values. Furthermore, overall pH values (6.8–7.7) and EC remained within optimal ranges for all species, except for the conductivity level of substrates with non-rinsed algal wracks that was above the tolerated levels. However, the rinsing procedure applied was sufficient to remove the salt excess as substrates prepared including rinsed wracks showed EC levels similar to controls. The C/N ratio varied depending on species and formulation, with higher ratios in P. ostreatus substrates without supplements and marked differences in P. eryngii at higher supplement levels. These findings indicated that algal wracks can be used to formulate substrates to cultivate all selected mushrooms and they will mainly contribute as an effective nitrogen-rich component. The main concern that should be taken into consideration before its utilization is the removal of sea salt that was easily achieved by simple rinsings with fresh water until conductivity reached levels from 5.55 to 0.88. P. ostreatus can grow with 1%–2% NaCl, but higher levels inhibit nutrient intake (Chang-Sung et al., 2006; Venâncio et al., 2017) and reduce the activity of the ligninolytic fungal enzymes responsible for breaking down organic matter in the substrate (Karan et al., 2012; Braham et al., 2021). The substrate designed for P. nameko, one of the most salt-sensitive strains, also reached values lower than 2.5 mS/cm (the maximum tolerated), indicating that the substrate might also be suited for its cultivation.Previous assays conducted on Petri plates containing dialyzed and non-dialyzed algal wracks from Mar Menor indicated that mycelia from all Pleurotus species studied were able to grow at comparable rates on both types of media, whereas the growth of H. tessulatus and P. nameko mycelia was slower on media containing non-dialyzed wracks (Lavega et al., 2023). Nonetheless, similar or slightly higher biomass production was observed on non-dialyzed algal wracks (Mamede et al., 2023). These results suggest that a simple rinsing procedure may be more effective than an intensive desalting process, such as dialysis using highly purified water, which could also remove other potentially beneficial compounds that stimulate fruiting body production, including agricultural fertilizers providing nitrogen and phosphorus, as algal wracks from Mar Menor were found to be highly enriched with these nutrients (Tarrass et al., 2024). Supporting this, related species such as Pleurotus florida have been reported to exhibit increased mycelial growth when inorganic phosphate concentrations in the cultivation substrate were elevated (Kamal et al., 2012).

Table 4

| Mushroom species | Algal wrack (% dw) | Supplements (% dw) | Moisture (%) | % Nit. org | % Organic content | pH | Conductivity (mS/cm) | C/N ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. ostreatus | 0 | 0 | 79.30 ± 0.10f | 0.92 ± 0.09a | 87.13 ± 0.23c | 7.55 ± 0.57a | 3.73 ± 0.19c | 54.98 ± 5.7e |

| 20 (non-rinsed) | 0 | 78.40 ± 0.78ef | 1.41 ± 0.08c | 79.06 ± 1.07a | 7.57 ± 0.31a | 4.79 ± 0.52d | 32.55 ± 1.31bc | |

| 20 | 0 | 76.10 ± 0.45de | 1.57 ± 0.10de | 84.6 ± 0.65b | 6.78 ± 0.22a | 3.98 ± 0.57cd | 31.07 ± 1.80bc | |

| 20 | 2.5 | 71.78 ± 0.30c | 1.65 ± 0.06ef | 86.23 ± 0.73c | 7.11 ± 0.4a | 1.82 ± 0.10ab | 31.06 ± 0.28bc | |

| 40 | 2.5 | 75.05 ± 1.32d | 1.65 ± 0.04ef | 88.07 ± 0.47cd | 7.05 ± 0.06a | 2.18 ± 0.18b | 31.78 ± 0.41bc | |

| 60 | 2.5 | 73.58 ± 1.31cd | 1.73 ± 0.00f | 86.5 ± 1.86c | 7.07 ± 0.07a | 2.11 ± 0.01b | 29.2 ± 0.30ab | |

| 20 | 5 | 60.96 ± 0.75b | 2.01 ± 0.00g | 86.67 ± 0.17c | 7.39 ± 0.23a | 1.78 ± 0.80ab | 25.4 ± 0.10a | |

| 40 | 5 | 56.53 ± 1.00a | 1.72 ± 0.12f | 89.95 ± 0.56d | 7.37 ± 0.06a | 1.62 ± 0.45ab | 30.4 ± 1.89b | |

| 60 | 5 | 59.68 ± 0.96b | 1.22 ± 0.03b | 93.24 ± 0.36e | 7.4 ± 0.10a | 1.22 ± 0.24a | 44.27 ± 1.14d | |

| 0 | 0.63 | 76.41 ± 1.04def | 0.87 ± 0.01a | 92.69 ± 0.17e | 7.23 ± 0.15a | 1.37 ± 0.05ab | 62.12 ± 0.89f | |

| 20 | 0.63 | 70.5 ± 3.81c | 1.46 ± 0.05cd | 87.86 ± 1.33c | 7.24 ± 0.48a | 1.43 ± 0.36ab | 34.87 ± 0.64c | |

| P. eryngii | 0 | 5 | 65.35 ± 1.27a | 1.1 ± 0.17b | 87.8 ± 1.86bc | 7.24 ± 0.42a | 1.43 ± 0.34a | 34.87 ± 8.70b |

| 20 | 5 | 68.26 ± 2.66b | 1.19 ± 0.16bc | 90.53 ± 1.7b | 7.78 ± 0.35a | 0.86 ± 0.32a | 42.28 ± 7.30ab | |

| 0 | 7.5 | 62.81 ± 1.21a | 0.86 ± 0.06a | 94.28 ± 0.52c | 7.48 ± 0.21a | 0.93 ± 0.5a | 55.19 ± 4.67c | |

| 20 | 7.5 | 64.99 ± 1.96a | 1.36 ± 0.13c | 93.82 ± 0.71a | 7.2 ± 0.17a | 1.04 ± 0.8a | 55.38 ± 3.62a | |

| H. tessulatus | 0 | 7.5 | 65.11 ± 0.49a | 1.05 ± 0.11a | 92.36 ± 0.45a | 7.69 ± 0.56a | 1 ± 0.24a | 51.22 ± 5.15a |

| 20 | 7.5 | 67 ± 0.04b | 1.26 ± 0.06a | 90.84 ± 0.55a | 7.47 ± 0.45a | 1 ± 0.48a | 41.91 ± 2.11a | |

| P. nameko | 0 | 7.5 | 66.43 ± 0.05a | 1.2 ± 0.16a | 91.78 ± 2.02a | 7.54 ± 0.13a | 0.73 ± 0.06a | 44.75 ± 6.88a |

| 20 | 7.5 | 66.2 ± 1.78a | 1.15 ± 0.24a | 92.26 ± 1.81a | 7.47 ± 0.16a | 0.95 ± 0.32a | 47.85 ± 10.82a |

Physical chemical parameters of the different substrate batches formulated (mean ± standard deviation).

Different letters indicate significant differences between materials according to the results of post-hoc Tukey’s test for the biological variables (n = 3, p < 0.05).

3.2 Influence of wrack addition on the fiber content of the formulated substrates

Fiber composition was evaluated in the formulated substrates prior to mushroom cultivation to assess the potential effects of algal wrack incorporation (Table 5). According to previous reports, cellulose levels of 35%–45%, hemicellulose levels of 20%–30%, and lignin levels of 10%–15% were considered optimal for the cultivation of P. ostreatus and P. eryngii (Adebayo and Martinez-Carrera, 2015). Comparable values have also been reported for other selected species, with H. tessulatus and P. nameko requiring 40%–50% cellulose, 20%–30% hemicellulose, and 20%–30% lignin (Kumla et al., 2020). Therefore, even when added at the highest tested concentration, algal wrack inclusion in the formulated substrates remained within these standardized ranges.

Table 5

| Mushroom species | Algal wrack (% dw) | Supplements (% dw) | NDF (% dw) | ADF (% dw) | Lignin (% dw) | Cellulose (% dw) | Hemicellulose (% dw) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. ostreatus | 0 | 0 | 82.76 ± 1.04e | 51.19 ± 3.86e | 10.55 ± 1.21cd | 42.84 ± 0.33f | 31.57 ± 3.64bcd |

| 20 (non-rinsed) | 0 | 72.21 ± 1.07cd | 47.35 ± 3.74de | 13.25 ± 0.18e | 36.25 ± 0.58de | 24.87 ± 3.00a | |

| 20 | 0 | 80.32 ± 1.5e | 51.63 ± 1.17e | 13.36 ± 0.04e | 38.27 ± 1.21e | 27.79 ± 0.41ab | |

| 20 | 2.5 | 70.22 ± 2.29bc | 36.28 ± 0.90a | 10.23 ± 0.64cd | 26.05 ± 0.47a | 33.94 ± 3.07cd | |

| 40 | 2.5 | 80.36 ± 0.13e | 43.91 ± 0.21cd | 8.4 ± 1.25ab | 34.78 ± 0.00d | 36.52 ± 0.15d | |

| 60 | 2.5 | 72.77 ± 1.47cd | 39.02 ± 2.38ab | 7.47 ± 0.72a | 31.55 ± 1.78c | 33.75 ± 2.64cd | |

| 20 | 5 | 64.26 ± 1.10a | 39.25 ± 1.39ab | 10.97 ± 0.82d | 28.28 ± 0.91b | 25.02 ± 2.49a | |

| 40 | 5 | 72.94 ± 3.38cd | 42.12 ± 1.53bc | 11.33 ± 1.03d | 30.79 ± 0.00c | 29.01 ± 0.22abc | |

| 60 | 5 | 73.93 ± 1.44d | 46.72 ± 2.19d | 11.42 ± 0.0d | 35.3 ± 2.02d | 27.21 ± 2.96ab | |

| 0 | 0.63 | 75.64 ± 0.43d | 47. ± 0.19de | 9.43 ± 0.92bc | 38.17 ± 1.11bc | 28.04 ± 0.62ab | |

| 20 | 0.63 | 66.86 ± 4.87ab | 38.76 ± 0.28ab | 9.06 ± 0.31bc | 29.71 ± 0.59bc | 28.09 ± 5.15ab | |

| P. eryngii | 0 | 5 | 71.75 ± 0.76b | 47.37 ± 2.02ab | 10.15 ± 2.10a | 37.11 ± 0.92b | 24.38 ± 1.71a |

| 20 | 5 | 73.73 ± 0.96b | 48.19 ± 2.14b | 10.47 ± 0.68a | 36.97 ± 0.96b | 25.53 ± 2.96a | |

| 0 | 7.5 | 75.04 ± 3.55a | 53.55 ± 3.71c | 13.92 ± 2.26b | 39.68 ± 3.42b | 22.74 ± 2.88a | |

| 20 | 7.5 | 67.9 ± 3.70a | 44.53 ± 2.70a | 13.7 ± 1.16b | 30.6 ± 1.98a | 22.75 ± 1.63a | |

| H. tessulatus | 0 | 7.5 | 76.24 ± 3.33a | 49.95 ± 2.63a | 9.73 ± 1.0a | 40.2 ± 1.77b | 26.29 ± 0.92b |

| 20 | 7.5 | 70.8 ± 2.04a | 47.58 ± 3.71a | 11.3 ± 1.,97a | 36.28 ± 1.86a | 23.23 ± 1.77a | |

| P. nameko | 0 | 7.5 | 72.77 ± 2.04a | 47.68 ± 4.04a | 9.55 ± 2.11a | 38.13 ± 2.06a | 25.09 ± 2.01a |

| 20 | 7.5 | 75.58 ± 2.33a | 48.85 ± 2.53a | 10.18 ± 0.14a | 37.52 ± 0.56a | 26.73 ± 0.93a |

Total fiber content of formulated substrates with algal wrack and supplements for mushroom cultivation (mean ± standard deviation).

Different letters indicate significant differences between materials according to the results of post-hoc Tukey’s test for the biological variables (n = 3, p < 0.05).

Moreover, only slight differences were observed between substrates with and without algal wracks. Significant variations in NDF and ADF were detected only in P. ostreatus substrates containing both 5% supplements and algal wracks, although the observed reductions seemed unlikely to be related to the supplemented algal wrack or to the supplement concentration. Increasing algal wrack concentration from 20% to 60% did not substantially affect NDF or ADF levels, and formulations containing 20% wracks without supplements showed values comparable to the control. A more detailed analysis of structural fiber fractions revealed that lignin content was significantly higher in P. ostreatus substrates containing 20% algal wracks compared with the control, whereas higher wrack inclusion (60%) produced either similar or lower lignin levels depending on the supplement percentage. These variations likely reflect mixture heterogeneity rather than algal lignin contribution, as green algae such as C. prolifera lack substantial lignin, a polymer mainly reported in brown algae and Sargassum species (Martone et al., 2009). Moreover, cellulose content was significantly lower in substrates enriched with algal wracks for P. ostreatus and H. tessulatus, while hemicellulose was slightly higher in wrack-containing (20%) substrates for P. ostreatus, P. eryngii, and P. nameko. These subtle differences were also likely to be because of the compositional variations among the mixed materials rather than intrinsic chemical disparities. Algal wracks may contribute with cellulose, hemicellulose, xylan, mannan, and sulfated heteroglycans as main polysaccharides described within the Caulerpa genus with relatively poor ulvan and starch concentrations (Chattopadhyay et al., 2007; Domozych et al., 2012). Thus, these results revealed that wheat straw, the main substrate component, shares a similar fiber composition to the marine residues, and therefore, they can be partially substituted by algal wracks to generate suitable substrates to cultivate the four mushroom species with no large fiber composition changes.

3.3 Fruiting bodies production on formulated substrates with algal wracks

The addition of non-rinsed algal wracks significantly reduced P. ostreatus yield by 46% compared to the control substrate (Table 6). In contrast, yields from substrates containing only rinsed algal wracks were statistically similar to those from the control, indicating that residual salinity in the non-rinsed biomass negatively affected productivity. Supplementation with 2.5% additional nutrients together with 20% to 60% algal wrack markedly increased P. ostreatus production, whereas increasing the supplement concentration to 5% reduced yield. However, a 2.5% supplementation involved high substrate production costs that might drastically reduce cultivation benefits as the nutrients supplemented were expensive nutrients (patented formula no. 202430026); therefore, the cultivation experiments were repeated with lower supplement contents. When the supplement level was reduced to 0.63%, the combination with 20% algal wrack enhanced the yield 45% compared to the control, suggesting that a slight supplementation and algal wrack addition increased its production without a significant increase in the production costs, and thus, the alternative substrate was an interesting opportunity for mushroom growers to increase their economic benefits. BE followed the same trend as yield, increasing and almost duplicating its value with the addition of the algal wracks.

Table 6

| Mushroom species | Algal wrack (% dw) | Supplements (% dw) | Incubation (days) | Yield (g mushroom/kg substrate) | Biological efficiency | Fruiting period (days) | Picking (days) | Complete cycle (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. ostreatus | 0 | 0 | 52 | 126.46 ± 6.70b | 60.89 ± 15.50ab | 16 | 5 | 73 |

| 20 (non-rinsed) | 0 | 52 | 67.76 ± 11.62a | 30.6 ± 5.42bc | 16 | 5 | 73 | |

| 20 | 0 | 52 | 135.52 ± 19.25b | 55.97 ± 5.09e | 19 | 8 | 79 | |

| 20 | 2.5 | 72 | 201.37 ± 39.09c | 71.91 ± 13.96e | 39 | 6 | 117 | |

| 40 | 2.5 | 72 | 294.04 ± 34.69de | 113.58 ± 13.40f | 35 | 10 | 117 | |

| 60 | 2.5 | 69 | 333.69 ± 31.41e | 130.89 ± 12.32g | 30 | 12 | 117 | |

| 20 | 5 | 36 | 134.27 ± 32.18b | 33.93 ± 1.69cde | 25 | 16 | 77 | |

| 40 | 5 | 37 | 206.29 ± 12.00c | 46.7 ± 2.63a | 25 | 16 | 77 | |

| 60 | 5 | 36 | 291.06 ± 12.31d | 70.98 ± 4.69cd | 25 | 16 | 77 | |

| 0 | 0.63 | 23 | 143.87 ± 25.42b | 59.16 ± 10.45cde | 13 | 8 | 44 | |

| 20 | 0.63 | 23 | 208.68 ± 2.85c | 64.82 ± 0.89de | 12 | 9 | 44 | |

| P. eryngii | 0 | 5 | 53 | 190.96 ± 3.93a | 55.01 ± 3.91a | 5 | 4 | 62 |

| 20 | 5 | 55 | 193.22 ± 28.77a | 58.9 ± 2.85a | 3 | 4 | 62 | |

| 0 | 7.5 | 38 | 173.62 ± 14.85a | 46.53 ± 6.60a | 4 | 3 | 45 | |

| 20 | 7.5 | 38 | 170.56 ± 8.82a | 48.37 ± 4.55a | 4 | 3 | 45 | |

| H. tessulatus | 0 | 7.5 | 90 | 19.28 ± 2.84a | 5.58 ± 0.82a | 15 | 4 | 109 |

| 20 | 7.5 | 90 | 78.57 ± 14.55b | 23.79 ± 4.41b | 13 | 6 | 109 | |

| P. nameko | 0 | 7.5 | 96 | 388.57 ± 23.87a | 115.88 ± 7.12a | 47 | 15 | 158 |

| 20 | 7.5 | 96 | 443.96 ± 27.52a | 126.62 ± 7.85a | 47 | 15 | 158 |

Cultivation time needed for each developmental stage and for total cultivation*, yield, and biological efficiency (mean ± standard deviation).

*Incubation days: time required from inoculation with spawn until substrate was fully colonized by mycelium. Fruiting period: time from fruiting induction to harvesting mature mushrooms. Picking days: days from start picking mushroom until completing the harvest. Complete cultivation: from inoculation of the substrate with spawn until harvesting all of the fruiting bodies.

Different letters indicate significant differences between materials according to the results of post-hoc Tukey’s test for the biological variables (n = number of bags of each trial, p < 0.05).

Although the addition of rinsed algal wracks to P. ostreatus substrates could yield results comparable to or higher than conventional substrates, complete substitution of wheat straw with algal biomass was not encouraged. An attempt to use 100% algal wrack was carried out, but no fruiting bodies were obtained (results not shown) as algal wracks by themselves lacked the physicochemical (Table 3) and fiber contents (Lavega et al., 2023) necessary to cultivate them. The addition of other by-products was always tested by partial substitution of wheat straw; i.e., banana leaves were tested up to 80% (de Carvalho et al., 2012), with higher yields than control; similarly, olive mill residues were added up to 25% (Kalmis et al., 2008; Hanumanta and Ashok, 2022), with similar yields to control, and coffee pulps were mixed up to 10%–20% for the cultivation of Pleurotus pulmonarius (Chai et al., 2021), with a 40% increase in yield in the substrates enriched with 10% of coffee pulps, reflecting the importance of maintaining an adequate lignocellulosic balance in the substrate (Sánchez et al., 1999). The fact that the addition of the marine residue yielded higher BE than all other residues suggested that algal wracks may provide, aside from their particular polysaccharide (Rachidi et al., 2021) composition, other bioactive compounds—potentially minerals (Ca and Fe) (Yokota et al., 2016; Julian et al., 2018), biostimulants (Godlewska et al., 2016; Álvarez-González et al., 2025; Brito-López et al., 2025), or phosphates—that enhance P. ostreatus mycelial development and fruiting (although no fungal growth stimulants were specifically reported in algae).

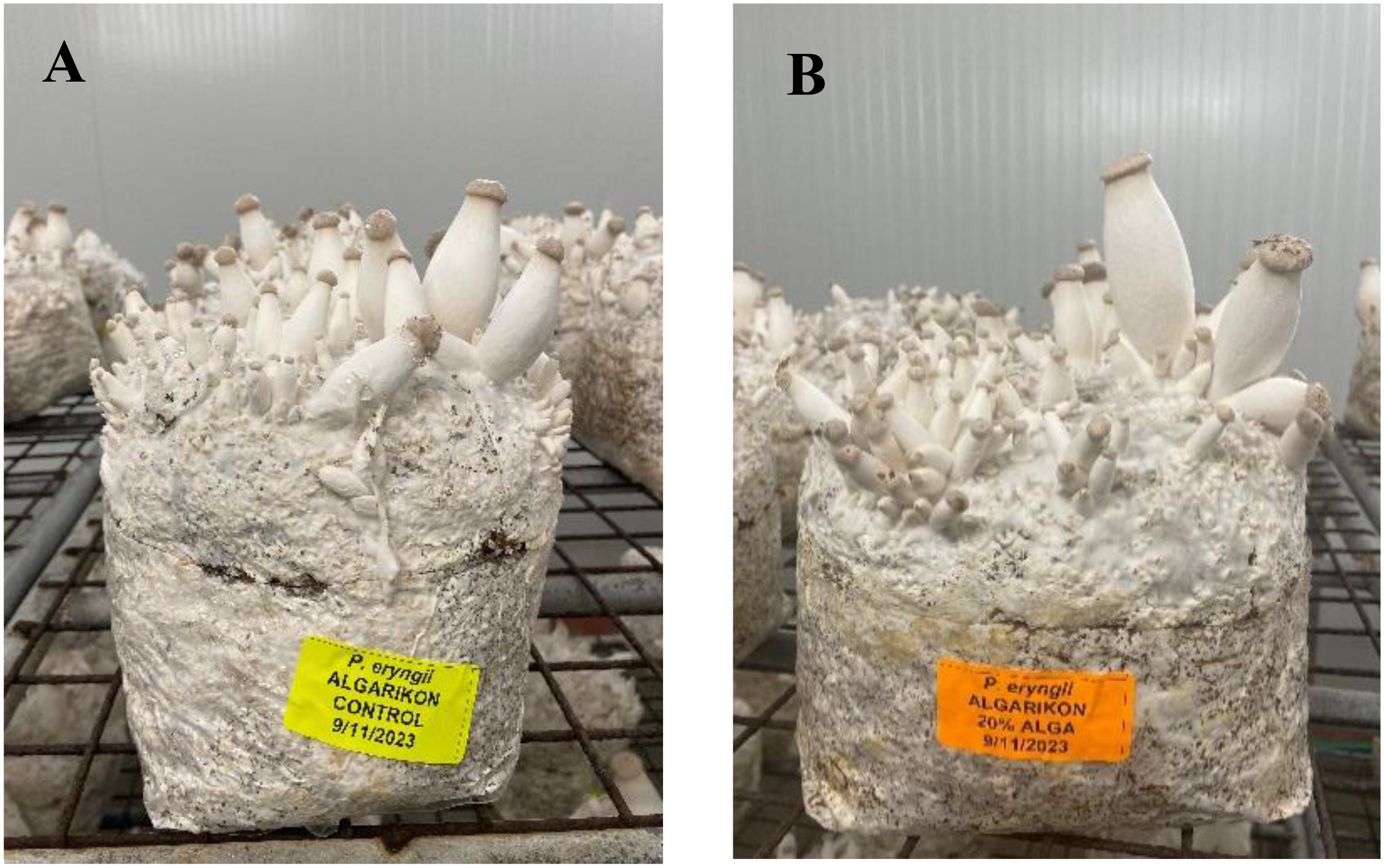

However, the addition of 20% algal wrack did not significantly modify P. eryngii yield (Figure 1). The utilized supplementation was higher than that for P. ostreatus, and high supplementation in the latter strain was detrimental; therefore, it might be the reason for the insignificant changes. Nevertheless, yield improvements were also observed for other species such as P. nameko (yields increased 14.2% compared to the control) and H. tessulatus that exhibited a striking 307.6% yield increase in wrack-enriched substrates, with corresponding gains in BE.

Figure 1

Fruiting bodies of P. eryngii were incorporated into the substrate formulation. (A) shows cultivation without using algal wracks as substrate, and (B) demonstrates cultivation utilizing algal wracks. The mushrooms were grown at 15°C, and the fruiting bodies were photographed after 56 days of cultivation.

Incubation time varied among species (Table 6). P. ostreatus initiated fruiting 23–36 days post-inoculation, representing the fastest colonization rate, followed by P. eryngii (38 days). H. tessulatus and P. nameko required 90 and 96 days, respectively, for full mycelial colonization. Fruiting initiation occurred earlier in wrack-enriched substrates for P. ostreatus and P. eryngii, while growth rates for the other species were comparable to controls. Harvest timing also differed, with P. eryngii completing its fruiting within 4 days, whereas P. nameko and P. ostreatus required 15–16 days. No significant differences were found in flushing periods between wrack-containing and control substrates. The total crop cycle was longest for P. nameko (158 days), followed by H. tessulatus and P. ostreatus (~84 days), while P. eryngii displayed the shortest cycle (49–51 days). These differences were primarily attributed to the specific mycelial characteristics of each fungal species. The duration of each cultivation phase is influenced by multiple factors, including substrate composition (Schoder et al., 2024), microorganisms (Suwannarach et al., 2022), and even the physiological mycelium “age”. Consequently, substantial variability in growth and fruiting times was reported among mushrooms of the Pleurotus genus (Song et al., 2024).

4 Conclusion

The study emphasizes the central role of substrate formulation in optimizing mushroom productivity, with lignocellulose content and EC emerging as key parameters. Incorporating algal beach wracks into mushroom substrates offers both agronomic and environmental benefits, transforming a problematic biomass into a valuable biotechnological resource.

The results highlight the importance of substrate formulation, particularly the roles of lignocellulose content and electrical conductivity, in optimizing fungal performance. Incorporating macroalgal residues offers a sustainable alternative that contributes to circular bioeconomy goals by converting environmental waste into valuable agricultural inputs.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation. ER: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MP-C: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. CS-R: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Visualization, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by the TED2021-129591B-C31 project (acronym Algarikon) financed by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/and the European Union by Next Generation EU/PRTR. S.F.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank the CTICH-ASOCHAMP staff for helping with cultivation of different mushroom varieties, the General Directorate of the Mar Menor lagoon (DGMM, Murcia) for granting access to algal wracks, and Reciclesan (Roldan) for the use of their facilities. Algarikon MM would also like to thank CocaCola Europacific partners and the Chelonian Research Foundation for the award within the 7th edition of Mares Circulares Awards (as “Innovative Business Initiative”).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adebayo E. Martinez-Carrera D. (2015). Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus) are useful for utilizing lignocellulosic biomass. Afr. J. Biotechnol.14, 52–67. doi: 10.4314/ajb.v14i1

2

Álvarez-González A. Serrano L. Gorchs G. Uggetti E. (2025). Exploring the biostimulant potential of Scenedesmus sp. grown in wastewater: impacts on plant growth and photosynthetic activity of lettuce. Chemosphere.382. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2025.144494

3

Álvarez-Rogel Barberá G. G. Maxwell B. Guerrero-Brotons García D.- Martínez-Sánchez J. J. et al . (2020). The case of Mar Menor eutrophication: state of the art and description of previously 3 tested Nature Based Solutions. Ecol. Eng.158, 106086. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2020.106086

4

AOAC . (2000). Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemistry. (Virginia, USA: AOAC).

5

Assan N. Assan N. Mpofu T. (2014). The influence of substrate on mushroom productivity-A Review. Sci. J. Crop Sci.3, 86–91. doi: 10.14196/sjcs.v3i7.1502

6

Belando M. D. Bernardeau-Esteller J. Paradinas I. Ramos-Segura A. García-Muñoz R. García-Moreno P. et al . (2021). Long-term coexistence between the macroalga Caulerpa prolifera and the seagrass Cymodocea nodosa in a Mediterranean lagoon. Aquat. Bot., 173. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2021.103415

7

Bernardeau-Esteller J. Sandoval-Gil J. M. Belando M. D. Ramos-Segura A. García-Muñoz R. Marín-Guirao L. et al . (2023). The Role of Cymodocea nodosa and Caulerpa prolifera Meadows as Nitrogen Sinks in Temperate Coastal Lagoons. Diversity15 (2). doi: 10.3390/d15020172

8

Braham S. A. Siar E. H. Arana-Peña S. Carballares D. Morellon-Sterling R. Bavandi H. et al . (2021). Effect of concentrated salts solutions on the stability of immobilized enzymes: Influence of inactivation conditions and immobilization protocol. Molecules26 (4). doi: 10.3390/molecules26040968

9

Brito-López C. van der Wielen N. Barbosa M. Karlova R. (2025). Plant growth-promoting microbes and microalgae-based biostimulants: Sustainable strategy for agriculture and abiotic stress resilience. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.380 (1927). doi: 10.1098/rstb.2024.0251

10

Chai W. Y. Krishnan U. G. Sabaratnam V. Tan J. B. L. (2021). Assessment of coffee waste in formulation of substrate for oyster mushrooms Pleurotus pulmonarius and Pleurotus floridanus. Future Foods4. doi: 10.1016/j.fufo.2021.100075

11

Chang-Sung J. Hwa-Jin S. Won-Sik K. Young-Bok Y. Jong-Chun C. Se-Chul C. (2006). Effects of NaCl concentrations on production and yields of fruiting body of oyster mushrooms, Pleurotus spp. Kor J. Mycol34, 39–53. doi: 10.4489/KJM.2006.34.1.039

12

Chattopadhyay K. Adhikari U. Lerouge P. Ray B. (2007). Polysaccharides from Caulerpa racemosa: Purification and structural features. Carbohy Polymers.68, 407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.12.010

13

Cueva A. R. Bernarda M. Hernández Niño-Ruiz A. (2017). Influence of C/N ratio on productivity and the protein contents of Pleurotus ostreatus grown in differents residue mixtures. Rev. la Facultad Cienc. Agrarias.49, 331–344.

14

de Carvalho C. S. de Aguiar L. V. Sales-Campos C. de Almeida Minhoni M. T. de Andrade M. C. (2012). Applicability of the use of waste from different banana cultivars for the cultivation of the oyster mushroom. Braz. J. Microbiol.43, 819–826. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822012000200048

15

Díez L. (2024). Los champiñoneros riojanos, al límite por la falta de tratamientos fúngicos ( Nuevecuatrouno). Available online at: https://nuevecuatrouno.com/2024/04/27/champinoneros-riojano-limite/ (Accessed October 7, 2025).

16

Domozych D. S. Ciancia M. Fangel J. U. Mikkelsen M. D. Ulvskov P. Willats W. G. T. (2012). The cell walls of green algae: A journey through evolution and diversity. Front. Plant Sci., 3(MAY). doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00082

17

Figueroa F. L. Vega J. Flórez-Fernández N. Mazón J. Torres M. D. Domínguez H. et al . (2025). Challenges and opportunities of the exotic invasive macroalga Rugulopteryx okamurae (Phaeophyceae, Heterokontophyta). J. Appl. Phyco37, 579–595. doi: 10.1007/s10811-024-03404-w

18

Gao M. Liang F. Yu A. Li B. Yang L. (2010). Evaluation of stability and maturity during forced-aeration composting of chicken manure and sawdust at different C/N ratios. Chemosphere78, 614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.10.056

19

García-Ayllon S. (2018). The Integrated Territorial Investment (ITI) of the Mar Menor as a model for the future in the comprehensive management of enclosed coastal seas. Ocean Coast. Manage.166, 82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.05.004

20

Gebru H. Belete T. Faye G. (2024). Growth and yield performance of pleurotus ostreatus cultivated on agricultural residues. Mycobiology52, 388–397. doi: 10.1080/12298093.2024.2399353

21

Geng Y. Wang Y. Li H. Li R. Ge S. Wang H. et al . (2024). Optimization of manure-based substrate preparation to reduce nutrients losses and improve quality for growth of. Agaricus bisporus Agri. 14 (10). doi: 10.3390/agriculture14101833

22

Godlewska K. Michalak I. Tuhy L. Chojnacka K. (2016). Plant growth biostimulants based on different methods of seaweed extraction with water. BioMed. Res. Int. doi: 10.1155/2016/5973760

23

Goglio P. Ponsioen T. Carrasco J. Milenkovi I. Kiwala L. van Mierlo K. et al . (2024). An environmental assessment of Agaricus bisporus ((J.E.Lange) Imbach) mushroom production systems across Europe. Eur. J. Agron., 155. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2024.127108

24

Hachicha S. Sallemi F. Medhioub K. Hachicha R. Ammar E. (2008). Quality assessment of composts prepared with olive mill wastewater and agricultural wastes. Waste Manage.28, 2593–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2007.12.007

25

Hanumanta D. L. Ashok L. B. (2022). Assessment of nutrient composition in banana leaf in hiriyur taluk of chitradurga district, karnataka. Environ. Ecol.40, 815—819.

26

Hoa H. T. Wang C. L. Wang C. H. (2015). The effects of different substrates on the growth, yield, and nutritional composition of two oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus cystidiosus). Mycobiology43, 423–434. doi: 10.5941/MYCO.2015.43.4.423

27

IEO-CSIC (2024). Status of seagrass meadows in the mar menor (Madrid, Spain: Spanish Institute of Oceanography).

28

Inoubli S. López-Álvarez M. Flórez-Fernández N. Shili A. Ksouri R. Torres M. D. et al . (2024). Microwave-assisted processing of ulvans from Mediterranean Caulerpa prolifera with in vitro cell viability. Algal Res.84. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2024.103808

29

Jayaraman S. Yadav B. Dalal R. C. Naorem A. Sinha N. K. Srinivasa Rao C. et al . (2024). Mushroom farming: A review Focusing on soil health, nutritional security and environmental sustainability. Farm Syst. 2 (3). doi: 10.1016/j.farsys.2024.100098

30

Julian A. Umagat M. Renato R. (2018). Mineral composition and yield of pleurotus ostreatus on rice straw-based substrate enriched with natural calcium sources. Int. J. Biol Pharm. Allied Sci.7. doi: 10.31032/ijbpas/2018/7.8.4501

31

Kalmis E. Azbar N. Yildiz H. Kalyoncu F. (2008). Feasibility of using olive mill effluent (OME) as a wetting agent during the cultivation of oyster mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus, on wheat straw. Biores Technol99, 164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.11.042

32

Kamal S. Upadhyay R. C. Ahlawat O. P. Singh M. (2012). Effect of phosphate supplementation on growth and extracellular enzyme production by some edible mushrooms. Mushroom Res.21, 23–33.

33

Karan R. Capes M. D. DasSarma S. (2012). Function and biotechnology of extremophilic enzymes in low water activity. Aquat. Biosyst.8 (1). doi: 10.1186/2046-9063-8-4

34

Kumla J. Suwannarach N. Sujarit K. Penkhrue W. Kakumyan P. Jatuwong K. et al . (2020). Cultivation of mushrooms and their lignocellulolytic enzyme production through the utilization of agro-industrial waste. Molecules25 (12). doi: 10.3390/molecules25122811

35

Lavega R. Grifoll V. Rascón E. Pérez-Clavijo M. Soler-Rivas C. (2023). The potential of the algae accumulated in mar menor shores as an alternative raw material for mushroom cultivation. IV Cial Forum.

36

Lavega González R. (2023). Caracterización de la estructura, dinámica, microbioma y propiedades funcionales de los hongos cultivados en La Rioja. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid (SP.

37

Lin H. Li P. Ma L. Lai S. Sun S. Hu K. et al . (2023). Analysis and modification of central carbon metabolism in Hypsizygus marmoreus for improving mycelial growth performance and fruiting body yield. Front. Microbiol.14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1233512

38

Liu S. Luo H. Jiang Z. Ren Y. Zhang X. Wu Y. et al . (2023). Nutrient loading weakens seagrass blue carbon potential by stimulating seagrass detritus carbon emission. Ecol. Indic., 157. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.111251

39

Lombardo J. Tejada S. Compa M. Forteza V. Gil L. Pinya S. et al . (2025). Oxidative stress response in native algae exposed to the invasive species Batophora occidentalis in S’Estany des Peix, Formentera (Balearic Islands). Front. Mar. Sci., 12. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1586402

40

López-Ballesteros A. Trolle D. Srinivasan R. Senent-Aparicio J. (2023). Assessing the effectiveness of potential best management practices for science-informed decision support at the watershed scale: The case of the Mar Menor coastal lagoon, Spain. Sci. Tot Environ., 859. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160144

41

Mamede M. Cotas J. Bahcevandziev K. Pereira L. (2023). Seaweed polysaccharides in agriculture: A next step towards sustainability. Appl. Sci.13 (11). doi: 10.3390/app13116594

42

Martone P. T. Estevez J. M. Lu F. Ruel K. Denny M. W. Somerville C. et al . (2009). Discovery of lignin in seaweed reveals convergent evolution of cell-wall architecture. Curr. Biol.19, 169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.031

43

Mendiola Lanao M. (2017). Caracterización de compuestos bioactivos y efecto de la aplicación de Pulsos Eléctricos de Moderada Intensidad de Campo en setas cultivadas en La Rioja ( Universitat de Lleida). Available online at: https://www.tesisenred.net/handle/10803/456031 (Accessed June 5, 2025).

44

Meng L. Fu Y. Li D. Sun X. Chen Y. Li X. et al . (2019). Effects of corn stalk cultivation substrate on the growth of the slippery mushroom (Pholiota Microspora). RSC Adv.9, 5347–5353. doi: 10.1039/c8ra10627d

45

Nyaupane S. Poudel M. R. Panthi B. Dhakal A. Paudel H. Bhandari R. (2024). Drought stress effect, tolerance, and management in wheat–a review. Cogent Food Agric.10 (1). doi: 10.1080/23311932.2023.2296094

46

Oei P. (2005). Small-scale mushroom cultivation: oyster, shiitake and wood ear mushrooms. 1st ed. (The Netherlands: Wageningen: Agromisa Foundation and CTA).

47

Oosterbaan M. Gómez-Jakobsen F. Barberá G. G. Mercado J. M. Ferrera I. Yebra L. et al . (2025). Characterization and potential causes of a whiting event in the Mar Menor coastal lagoon (Mediterranean, SE Spain). Sci. Tot Environ.978. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.179391

48

Padamini R. Kumar S. Dange M. M. Ali M. U. Chavda H. (2024). Mushroom: the fascinating fungi (India: Emerald Publishing House).

49

Pérez-Martín M.Á. (2023). Understanding nutrient loads from catchment and eutrophication in a salt lagoon: the mar menor case. Water (Switzerland)15 (20). doi: 10.3390/w15203569

50

Rachidi F. Benhima R. Kasmi Y. Sbabou L. Arroussi H. (2021). Evaluation of microalgae polysaccharides as biostimulants of tomato plant defense using metabolomics and biochemical approaches. Sci. Rep., 11(1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78820-2

51

Ragunathan R. Swaminathan K. (2003). Nutritional status of Pleurotus spp. grown on various agro-wastes. Food Chem.80, 371–375. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00275-3

52

Ravlikovsky A. Pinheiro M. N. C. Dinca L. Crisan V. Symochko L. (2024). Valorization of spent mushroom substrate: establishing the foundation for waste-free production. Recycling, 9(3). doi: 10.3390/recycling9030044

53

Rodil I. F. Pérez-Rodríguez V. Bernal-Ibáñez A. Pardiello M. Soccio F. Gestoso I. (2024). High contribution of an invasive macroalgae species to beach-wrack CO2 emissions. J. Environ. Manage367, 122021. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122021

54

Royse D. J. Sanchez J. E. (2007). Ground wheat straw as a substitute for portions of oak wood chips used in shiitake (Lentinula edodes) substrate formulae. Biores Technol.98, 2137–2141. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.08.023

55

Ruiz J. M. Albentsosa M. Aldeguer B. Alvarez-Rogel J. Yebra L. (2020). Informe de Evolución y Estado Actual del Mar Menor en Relación al Proceso de Eutrofización y Sus Causas 2020 (Madrid, Spain: Technical Report Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO); Spanish Institute of Oceanography), 165.

56

Ruiz J. M. Jaime Bernardeau-Esteller J. Belando M. D. (2022). Mar Menor lagoon: an iconic case of ecosystem collapse. Harmful Algae News, 70.

57

Sainos E. Díaz-Godínez G. Loera O. Montiel-González A. M. Sánchez C. (2006). Growth of Pleurotus ostreatus on wheat straw and wheat-grain-based media: Biochemical aspects and preparation of mushroom inoculum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.72, 812–815. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0363-0

58

Sánchez G. Olguin E. Mercado G. (1999). Accelerated coffee pulp composting. Biodegradation10, 35–41. doi: 10.1023/A:1008340303142

59

Sánchez-Fernández O. Marcos C. Puerta P. Sala-Mirete A. Pérez-Ruzafa A. (2025). Spatial and temporal scales of variability of mollusks in a strongly threatened mediterranean coastal lagoon (Mar menor, murcia, Spain). Water17, 657. doi: 10.3390/w17050657

60

Sangeeta S. D. Ramniwas S. Mugabi R. Uddin J. Nayik G. A. (2024). Revolutionizing Mushroom processing: Innovative techniques and technologies. Food Chem: X23. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101774

61

Schoder K. A. Krümpel J. Müller J. Lemmer A. (2024). Effects of environmental and nutritional conditions on mycelium growth of three basidiomycota. Mycobiology52, 124–134. doi: 10.1080/12298093.2024.2341492

62

Singh A. Saini R. K. Kumar A. Chawla P. Kaushik R. (2025). Mushrooms as nutritional powerhouses: A review of their bioactive compounds, health benefits, and value-added products. Foods14 (5). doi: 10.3390/foods14050741

63

Soler Rivas C. Marín Martín F. Lavega González R. Vázquez de Frutos L. Ruiz Rodríguez A. Pérez Clavijo M. et al . (2024). Sustrato a base de vegetales marinos apto para el cultivo de hongos comestibles (Madrid, Spain: P202430026 Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas).

64

Song J. Ma L. Zong T. Zhang Z. Chen Q. Yuan W. (2024). Effects of mycelium post-ripening time on the yield, quality, and physicochemical properties of Pleurotus geesteranus. Sci. Rep.14 (1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-82600-7

65

Suwannarach N. Kumla J. Zhao Y. Kakumyan P. (2022). Impact of cultivation substrate and microbial community on improving mushroom productivity: A review. Biology11 (4). doi: 10.3390/biology11040569

66

Tarrass F. Benjelloun M. Piccoli G. B. (2024). Hemodialysis water reuse within a circular economy approach. What can we add to current knowledge? A point of view. J. Nephrol. doi: 10.1007/s40620-024-01989-6

67

Thai M. Safianowicz K. Bell T. L. Kertesz M. A. (2022). Dynamics of microbial community and enzyme activities during preparation of Agaricus bisporus compost substrate. ISME Commun., 2(1). doi: 10.1038/s43705-022-00174-9

68

Ulaski B. P. Otis E. O. Konar B. (2023). How landscape variables influence the relative abundance, composition, and reproductive viability of macroalgal wrack in a high latitude glacial estuary. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.280. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2022.108169

69

Valverde M. E. Hernández-Pérez T. Paredes-López O. (2015). Edible mushrooms: Improving human health and promoting quality life. Int. J. Microbiol. 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/376387

70

van Soest P. J. Robertson J. B. Lewis B. A. (1991). Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci.74, 3583–3597. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2

71

Venâncio C. Pereira R. Freitas A. C. Rocha-Santos T. A. P. da Costa J. P. Duarte A. C. et al . (2017). Salinity induced effects on the growth rates and mycelia composition of basidiomycete and zygomycete fungi. Environ. Pollut231, 1633–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.09.075

72

Vincevica-Gaile Z. Sachpazidou V. Bisters V. Klavins M. Anne O. Grinfelde I. et al . (2022). Applying macroalgal biomass as an energy source: utility of the baltic sea beach wrack for thermochemical conversion. Sustainability14, 13712. doi: 10.3390/su142113712

73

Wang X. Lu X. Li F. Yang G. (2014). Effects of temperature and Carbon-Nitrogen (C/N) ratio on the performance of anaerobic co-digestion of dairy manure, chicken manure and rice straw: Focusing on ammonia inhibition. PloS One, 9(5). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097265

74

Yokota M. E. Frison P. S. Marcante R. C. Jorge L. F. Valle J. S. Dragunski D. C. et al . (2016). Iron translocation in Pleurotus ostreatus basidiocarps: Production, bioavailability, and antioxidant activity. Genet. Mol. Res.15 (1). doi: 10.4238/gmr.15017888

Summary

Keywords

algal wracks, biological efficiency, Caulerpa prolifera , circular bioeconomy, eutrophication, mushroom cultivation, substrate formulation

Citation

Lavega R, Rascón E, Soler-Rivas C and Pérez-Clavijo M (2025) Utilization of algal beach wracks as a supplementary substrate for enhancing mushroom production. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1708048. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1708048

Received

19 September 2025

Revised

24 November 2025

Accepted

25 November 2025

Published

15 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Saravana Periaswamy Sivagnanam, Munster Technological University, Ireland

Reviewed by

Asmamaw Tesfaw, Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia

Chanchao Chem, Gunma University, Japan

Mrutyunjay Padhiary, Assam University, India

Rusdi Hasan, Universitas Padjadjaran Departemen Biologi, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Lavega, Rascón, Soler-Rivas and Pérez-Clavijo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rebeca Lavega, r.lavega@ctich.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.