Abstract

This study was conducted to investigate the feed attractant properties of recombinant Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′ (secreting Patt, a functional peptide screened after enzymatic hydrolysis of the cotton meal) on the appetite regulatory system, growth performance, intestinal structure integrity, and digestive and absorptive functions of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). A total of 240 blunt snout breams were selected (10.85 ± 0.25 g) and divided into four groups (three replicates per group), including control group (C, basic diet), original bacteria group (OB, 1 × 108 CFU/kg Bacillus subtilis CM65) and two levels of recombinant bacteria groups (RB1, 1 × 108 CFU/kg Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′; RB2, 1 × 109 CFU/kg Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′). After a 10-week feeding trial, the results showed that the appropriate dietary Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′ supplementation (1 × 109 CFU/kg) enhanced appetite and increased feed intake while improving growth performance via the activation of growth hormone–insulin-like growth factor (GH–IGF) axis, enhanced intestinal absorptive capability, and maintained the integrity of intestinal structure by increasing the relative mRNA expression of tight junction proteins. Overall, those indices in the OB group had no significant change. In conclusion, this study confirmed that Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′ (or Patt) has great potential as a feed attractant, which can be recommended for use as a long-lasting effective feed attractant for fish.

1 Introduction

Aquaculture, as an important source of high-quality animal protein, has proven to play a vital role in contributing to food security, alleviating global hunger and promoting economic growth (Yan et al., 2023). With the rapid development of aquaculture, the demand and production of aquafeed have increased rapidly, while the gap between the supply and demand of fishmeal (a high-quality protein source for aquafeeds) is becoming increasingly serious, forcing experts to search for new cheaper alternative protein sources to partly or even completely substitute fishmeal (Mugwanya et al., 2022). However, many studies have shown that fishmeal substitution may lead to poor palatability, low feed intake, and poor digestibility (Wang A. et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2022; Yan et al., 2024), which makes the development of feed attractants a hot topic (Rao et al., 2018) because a high-quality feed attractant can not only alleviate the adverse effects mentioned above (Li et al., 2025; Pang et al., 2024) but also reduce feed losses and wastes in water, thereby lessening environmental pressure and reducing the cost of aquaculture (Ballester-Moltó et al., 2017; Llagostera et al., 2019). Overall, feed attractants are important for sustainable aquaculture development.

Screening methods for aquafeed attractants can be briefly divided into two categories based on the duration of the screening experiment: one is short-term screening, which is mainly based on the intuitive feeding behavior of aquatic animals, including the maze method, touch ball method, and so on (Cheng et al., 2019). By this way, the attractant being screened itself possesses a strong odor and can stimulate feeding by activating the sensory organ of the fish (Yacoob et al., 2002). Another category relies on long-term culture experiment to evaluate the quality of feed attractants by using the actual feed intake as an index, which was considered as a more accurate and practical way (Soengas et al., 2018). Moreover, the feed attractants selected by this method are considered able to act on the feeding regulatory system of fish, thereby exerting a long-term feed-promoting effect (Bertucci et al., 2019). Peptides have a variety of flavor properties that stimulate the nervous system of aquatic animals, increasing their appetite and improving feed taste and palatability (Ball et al., 2004). Small peptides are potent attractants currently used as alternatives to traditional feed attractants in aquaculture (Conti et al., 2024; Peng et al., 2022; Tusche et al., 2011).

Previous laboratory studies have shown the promotion of feeding behavior using enzyme-digested cotton meal products on blunt snout bream (Yuan et al., 2019), which might be related to the increase in the content of small peptides (180–1,500 Da) before and after the enzyme digestion (Yuan et al., 2020). Based on this, a functional small peptide, Patt (FRQGDVIALP), was preliminarily screened from the digested products of its content. Furthermore, its appetite-stimulating potential was evaluated in vitro by using primary intestinal epithelial cells isolated from blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). Patt might have the potential to promote feeding, which needed to be verified by a long-term growth experiment. However, the high price of adding peptides directly to aquatic feed is detached from production realities, which leads to peptides usually being added to feed in the form of enzymatic digests of protein products (Chen et al., 2023; He et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2019). However, insufficient investigation of the functional mechanisms of such peptides has prompted a shift toward probiotics and genetically engineered-driven peptide expression.

Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis), a promising probiotic, has several advantages for aquaculture. It can form spores under unfavorable conditions and is non-pathogenic to aquatic animals, making it a better choice to be added as a vector for administering an aquafeed supplement while also serving as a probiotic (Ghosh, 2025; Kuebutornye et al., 2020). It has been reported that B. subtilis can enhance feed intake, promote growth, and improve antioxidant defense as well as the intestinal functions of aquatic animals (Kuebutornye et al., 2019). In addition, B. subtilis is a good vector for heterologous protein expression. According to previous studies (He et al., 2024; Xiong et al., 2024), a peptide with antioxidant and immune-enhancing properties was successfully inserted into B. subtilis CM65 and enhanced the antioxidant capacity of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) and blunt snout bream, which provides a theoretical basis for this experiment. Combining B. subtilis CM65 with Patt and adding Patt in the form of added recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ can save costs and enable the evaluation of the actual feed attractant effect of the Patt.

Blunt snout bream, one of the popular freshwater species in China, is famous between fish farmers and consumers for its high growth rate and tasty flesh, thus having a significant economic value (Jiang et al., 2024; Wang X. et al., 2024). As an herbivorous species used in traditional culture, developing a suitable aquafeed attractant for it can not only promote the development of the farming industry but also provide new ideas for the preparation and selection of feed attractants. Obviously, evaluating the function of the aquafeed attractant only from the perspective of feed intake is biased. Although some feed attractants can increase feed intake, they have no significant growth-promoting effect on aquatic animals (Calo et al., 2024; Pulido-Rodriguez et al., 2021; Zarantoniello et al., 2022). The activation of the appetite regulatory system contributes to the increasing feed intake, while the digestive and absorptive system determines growth performance (Zhao et al., 2019). The intestine is an important part of the peripheral appetite regulatory system as well as the largest digestive and absorptive organ of blunt snout bream, and the integrity of the intestinal structure is fundamental to its functions (Zhou et al., 2023). Overall, this study aimed to construct recombinant B. subtilis CM65 expressing Patt peptide and investigated its appropriate supplementation level and effects on the growth, appetite regulation, and the structure and functions of the intestine to assess its potential effectiveness as a feed attractant of blunt snout bream. These results can offer new theoretical insight into the development of aquatic feed additives.

2 Materials and methods

In this study, the feeding schemes and all experimental operations were handed by The Animal Care and Use Committee at Nanjing Agriculture University which granted permission (license number: SYXK (Su)2021-0086).

2.1 Patt, B. subtilis CM65, and recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′

Peptide sequences of enzyme-digested cotton meal products were determined according to the previous laboratory study of Yuan et al. (2020), and Patt (FRQGDVIALP) was selected from the products. An Escherichia coli–Bacillus subtilis shuttle expression vector pBE plasmid, which consist of an ampicillin-resistant gene originated from Escherichia coli as well as a kanamycin-resistant gene originated from B. subtilis, was stored in our lab. As Patt itself has a very low molecular weight (1,100 Da), it is difficult to be recognized and expressed by direct introduction of the pBE. According to previous laboratory studies (He et al., 2024; Xiong et al., 2024), five Patt segments were tandemly attached to His-tag to constitute the pBE-Patt′. To clone the plasmid, Escherichia coli was cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C with 200 r/min shaking.

A plasmid-free strain of B. subtilis CM65, whose NCBI accession number is “SAMN37990”, has shown that the survival rate of its spore approached to 100% under reaction conditions of 80°C for 15 min, suggesting that it can be used as a feed additive to be added prior to pelleting (Xiong et al., 2024). The pBE-Patt′ plasmid obtained was transformed into competent B. subtilis CM65 cell to constitute the recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ and was then cultured in LB medium containing 100 μg/mL kanamycin (CAS#25389-94-0, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) at 37°C with 200 r/min shaking for 48 h to obtain spore and harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min (TGL16M, YINGTAI Instrument, China). The same protocols (without kanamycin) above were observed to harvest the spore of B. subtilis CM65. After that, the spread plate method was adopted to calculate the colony-forming units (CFU) of the spores obtained, wherein B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ was 1 × 1012 CFU/kg and B. subtilis CM65 was 2 × 1013 CFU/kg. Additionally, the content of Patt in B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ (1 × 1012 CFU/kg) was about 25.96% (of total protein), which was measured by using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (Orbitrap Astral and Vanquish Neo UHPLC, Thermo Scientific, American).

2.2 Experimental design and feeding trial

Four isonitrogenous (27% crude protein) and isolipidic (7% crude lipid) experimental diets were formulated as follows: the control group (C, basic diet), the original bacteria group (OB, 1 × 108 CFU/kg B. subtilis CM65), and two levels of recombinant bacteria groups (RB1, 1 × 108 CFU/kg B. subtilis CM65-Patt′; RB2, 1 × 109 CFU/kg B. subtilis CM65-Patt′). The composition of the experiment diet is shown in Table 1, with fish meal, soybean meal, cottonseed meal, and rapeseed meal served as protein sources, and soybean oil was adopted as the lipid source. In addition, the bacteria were separately added by dissolving in 50 mL sterile water and then spraying into the well-mixed diet. After that, the diet was prepared into particles with a particle size of 2 mm and stored at -20°C.

Table 1

| Ingredients (%) | C | OB | RB1 | RB2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish meal (g kg-1) | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |||

| Soybean meal (g kg-1) | 25.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | |||

| Cottonseed meal (g kg-1) | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.7 | |||

| Rapeseed meal (g kg-1) | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | |||

| Soybean oil (g kg-1) | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | |||

| Corn starch (g kg-1) | 28.0 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 28.0 | |||

| Rice bran (g kg-1) | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | |||

| Calcium biphosphate (g kg-1) | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | |||

| Ethoxyquin (g kg-1) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| Salt (g kg-1) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| Premixa (g kg-1) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| B. subtilis supplement | |||||||

| B. subtilis CM66, CFU kg-1 | 0 | 1 × 108 | 0 | 0 | |||

| B. subtilis CM66-Patt′, CFU kg-1 | 0 | 0 | 1 × 108 | 1 × 109 | |||

| Proximate composition (dry matter basis) | |||||||

| Crude protein (%) | 27.81 | 27.71 | 26.94 | 27.51 | |||

| Crude lipid (%) | 7.96 | 7.35 | 7.88 | 7.65 | |||

| Crude ash (%) | 8.09 | 8.10 | 7.83 | 8.15 | |||

| Moisture (%) | 13.48 | 13.18 | 12.70 | 12.93 | |||

Formulation and proximate composition of diets.

Premix supplied the following minerals (g/kg of diet) and vitamins (IU or mg/kg of diet): CuSO4·5H2O, 2.0 g; FeSO4·7H2O, 25 g; ZnSO4·7H2O, 22 g; MnSO4·4H2O, 7 g; Na2SeO3, 0.04 g; KI, 0.026 g; CoCl2·6H2O, 0.1 g; vitamin A, 900,000 IU; vitamin D, 200,000 IU; vitamin E, 4,500 mg; vitamin K3, 220 mg; vitamin B1, 320 mg; vitamin B2, 1,090 mg; vitamin B5, 2,000 mg; vitamin B6, 500 mg; vitamin B12, 1.6 mg; vitamin C, 5,000 mg; pantothenate, 1,000 mg; folic acid, 165 mg; and choline, 60,000 mg.

The juvenile blunt snout bream of this study was provided by a fish hatchery at Ezhou (Hubei, China). Before the formal feeding trial, a 2-week acclimation culture was performed to establish the feeding reflexes of fish. After that, a total of 240 healthy blunt snout bream (10.85 ± 0.25 g) were randomly and evenly divided into 12 net cages (three replicates per diet at 20 fish per cage), each with a capacity of 2 m3 (length/width/height = 2:1:1) in an outdoor pond, with each net cage providing ample space for the fish to move freely (Liu et al., 2024). During the feeding trial, the fish were fed to saturation three times a day (8:00, 12:00, and 16:00) for 10 weeks. On each day before the morning feeding, 50 g feed for each cage was weighed. After feeding, the remaining feed would be reweighed to calculate the feed intake. Throughout the feeding trial, the water conditions were measured using a YSI ProPlus (YSI Water Quality Testing Instrument Co., Ltd., OH, USA) within a temperature range from 23°C to 28°C, pH was 7.1 to 7.3, dissolved oxygen levels were maintained at 5.0 to 6.0 mg/L, and ammonia nitrogen concentrations were below 0.04 mg/L.

2.3 Proximate composition analysis

According to the standard method of AOAC (2005), the contents of moisture, crude protein, crude lipid, and crude ash of the diets (nine samples per group) were measured. The moisture contents were determined by drying samples at 105°C to a constant weight according to (AOAC, 2005) method no. 925.10. Crude protein content (N factor = 6.25) was quantified by using an automated Kjeldahl nitrogen analyzer (FOSS KT260, Switzerland) by Kjeldahl (AOAC, 2005) method no. 990.03. The crude lipid content was quantified by ether extraction using a Soxhlet System (Soxtec System HT6, Sweden) according to AOAC (2005) method no. 2003.05. The crude ash contents were determined by burning samples at 550°C in a muffle furnace to a constant weight according to AOAC (2005) method no. 923.03. The proximate composition of each diet is shown in Table 1.

2.4 Sample collection

At the end of the feeding trial, the fish were starved for 24 h for sampling. All of the fish in each cage were numbered and weighed. Four fish were randomly selected from each cage (four individual samples per replicate; 12 samples per diet in total) and anesthetized with MS-222 (100 mg/L) (#E10521, Sigma, USA) to measure the body weight, total length, body length, and body width. Based on a study by Chen et al. (2022), blood was collected from the tail vein and stored in anticoagulant tubes, which were moistened with sodium heparin (0.2 g dissolved in 5 mL distilled water) (CAS#9041-08, Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd, China) and oven-dried at 65°C in advance. Blood was later rapidly sampled and centrifuged (3,000 × g, 4°C, 10 min) in a centrifuge (TGL16M, Yingtai Instrument, China) to collect plasma, and those samples were then stored at -20°C for subsequent experiments. Then, samples of brain, liver, intestinal, and intraperitoneal fat were collected and weighed to calculate the biometric parameters. After that, the whole intestines were carefully rinsed with sterile deionized water, and the mid-intestine was dissected with sterile scissors following the method described by Huang et al. (2025). One portion of the mid-intestine was preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological observation, and the remaining samples were stored at -80°C for further analysis.

2.5 Analytical procedures

2.5.1 Plasma appetite hormone analysis

An ELISA method was adopted to quantify plasma neuropeptide Y (NPY) and peptide YY (PYY) level (two individual samples per replicate; six samples per diet in total). The kits (cat. no. XFH14038 and cat. no. XFH14015) used were from Nanjing Xin Fan Biology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China), and the method of determination was performed according to the protocols.

2.5.2 Intestinal digestive analyses

Intestinal samples (three individual samples per replicate; nine samples per diet in total) were homogenized with sterile saline at a ratio of 1:9 by mass volume and then centrifuged. The supernatant was collected, and 10% tissue homogenate was prepared for the determination of digestive enzyme activities. A colorimetric assay was adopted to determine the α-amylase (AMS) activity, trypsin (TPS) activity, and lipase (LPS) activity by using the kits (cat. no. C016-1-1, cat. no. A080-2-2, and cat. no. A054-2-1) from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5.3 Intestine hematoxylin and eosin

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining was performed at Shandong SparkJade Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China). Intestine tissues (two individual samples per replicate; six samples per diet in total) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for over 24 h, subsequently dehydrated gradually with alcohol, and then embedded in paraffin after being transferred to a xylene solution. A 6-μm-thick paraffin section was prepared and stained with conventional HE, followed by fixation with neutral gum. Subsequently, images (one slide per sample) were captured using an upright microscope (BX51, Olympus, Japan). The field of view with complete and straight villi was selected on the tissue sections of each part. Villus height (VH), villus width (VW), and muscle layer thickness (MLT) were measured by using Image Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA) for further structural analysis with each three fields analyzed per slide.

2.5.4 Real-time quantitative PCR

Intestinal and brain samples (two individual samples per replicate; six samples per diet in total) were lysed with trizol (Invitrogen, CA, USA) at a ratio of 1/10 to extract RNA. The absorbance at 260 and 280 nm of each sample was measured by using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to assess the content and purity of the extracted RNA. Next, the extracted RNA was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA by using Evo M-MLV RT Mix Kit with gDNA Clean for qPCR Ver.2 (Accurate Biology, Hunan, China). The cDNA was then used for qRT-PCR with the polymerase chain reaction performed on CFX96TM Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA). The qPCR reaction protocols were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 s. Melting curve analysis was performed by heating from 60°C to 95°C with a ramp rate of 0.1°C/s according to the instructions for SYBR Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (Accurate Biology, Hunan, China).

The expression levels of the target genes were normalized to elongation factor 1 alpha (ef1α) using the comparative Ct method (2−ΔΔCt) (Liu et al., 2024). The primers designed are shown in Table 2. It should be mentioned that all of the PCR were highly specific and reproducible (0.998 > R2 > 0.983), where all primer pairs had equivalent PCR efficiencies (from 0.91 to 1.01).

Table 2

| Genes | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) | Accession numbers or references | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appetite regulation | ||||

| npy | CGCCTGCTTGGGAACTCTTA | TGGACCTTTTGCCGTACCTC | JQ301475.1 | 0.97 |

| pyy | AGTCTACTTTCAACAATAAAGCAGG | GCGTCATGTTCCCTAACCCA | AF233875.1 | 0.95 |

| npy 1r | GTGTGAGGTAACGCAGCTCT | CAACCACCGAACGAACACAC | XM_048197605.1 | 0.92 |

| npy 2r | GCAGACAATTCAGGGTTGCG | GCCACAAGCATTTTCGTCGT | XM_048197241.1 | 0.91 |

| agrp | GGAGTCTTGTGCAGACCCTC | CAGCCTTACCCAGATCCTCATC | MK165096.1 | 0.94 |

| pomc | GTGGGTTTCCTACCTGCACA | CCCCTCACCATCTCTTTTGC | AY125332.2 | 0.91 |

| lep | CACATCACTGCGTAACTGG | TGACACCCTAACTACCTTCC | KJ193853.1 | 0.96 |

| cck | CGCAGAAGTTCCTCTCCGAA | TCATACTCTTCTGCGCTCCG | AY125332.2 | 0.96 |

| Growth promotion | ||||

| igf1 | CGGTTTTCACAGGTGCACAG | ACAGGGTGCCCAAAATCCTT | JQ398496.1 | 0.99 |

| Gh | GAGCCATCTCAAACAGCC | AGCAAGCCAGAAGACGAA | AY170124.1 | 1.01 |

| Ghr | TGGCACAGATACCAAGCA | GGGAGAAGATGAGCAGGA | JN896373.1 | 0.98 |

| Intestine structure | ||||

| claudin 3c | GGGCATTATCGGCTGGATCA | TGTCCGGTGCTCTGTACAAC | XM_048167600.1 | 1.02 |

| claudin 4l | TTGTGATTGGGATCCTGGGC | TGGTTTTGGAGCTCTCGTCC | XM_048167602.1 | 0.97 |

| occludin | GCGCGTTCTGTGGTATGATG | GTCAGAACCACTACTTGGAAGGT | XM_048187597.1 | 0.96 |

| Intestine absorption | ||||

| slc1a3 | GGAATGCTTTCGTCATCCTCAC | CAGAGCGGCCATACCTGTAATT | KY200978 | 0.90 |

| slc6a19b | ACCGCATCTTGCTCACAGTTATT | ACCACTGGAAAGGCTGTTTATGT | KX823960 | 0.91 |

| slc7a7 | GTCCCATACTTCACATAGGCA | GATAGCCATCACTTTCTCCAAC | JX013494 | 0.93 |

| slc7a8 | TGGTGAGAAGCTGTTGGGAGTGA | GCAAGTGAAGAGTAGGGCTGGAA | GU474428 | 0.90 |

| slc7a9 | TTCTACAGTCTTCTGCCGTTGC | AGAGCTGGAGAAGGCGTGTAAC | KX823958 | 0.92 |

| slc7a1 | TGCACAGGCTGAACAGGACACT | CGACATCACTGAACCCTCCAAC | KY200979 | 0.95 |

| slc38a2 | AGAAGAGTCCTGCAAACCCAA | CACAAACATTCCCAGAAACGA | KY200981 | 0.92 |

| slc7a5 | CAACATGAGCCGACCAGGAGAC | CCAGCGACAACCCGACTGAACC | KY200980 | 0.96 |

| slc6a6 | GCAGAGTTGGGCACGACAATCAC | GGAAGAGCGGCTGAACCAAGTAG | KX682391 | 0.93 |

| slc6a14 | TCATTGCGTACCCTGATGCTCT | ACTTCAGAACTTTGGGATAGGCA | KX823959 | 0.93 |

| Reference gene | ||||

| ef1α | CTTCTCAGGCTGACTGTGC | CCGCTAGCATTACCCTCC | X77689.1 | 0.98 |

Nucleotide sequences of the primers used to assay gene expression by RT-PCR.

npy, neuropeptide Y; pyy, peptide YY; npy 1r, neuropeptide Y receptor Y1; npy 2r, neuropeptide Y receptor Y2; agrp, agouti related neuropeptide; pomc, proopiomelanocortin; lep, leptin; cck, cholecystokinin; igf1, insulin-like growth factors 1; gh, growth hormone; ghr, growth hormone receptor; slcia3, solute carrier family 1 member 3; slc6a19b, solute carrier family 6 member 19b; slc7a7, solute carrier family 7 member 7; slc7a8, solute carrier family 7 member 8; slc7a9, solute carrier family 7 member 9; slc7a1, solute carrier family 7 member 1; slc38a2, solute carrier family 38 member 2; slc7a5, solute carrier family 7 member 5; slc6a6, solute carrier family 6 member 6; slc6a14, solute carrier family 6 member 14; ef1α, elongation factor 1 alpha.

2.6 Calculations of growth performance parameters

The following formula was used to calculate the growth performance indicators:

In the formula, W0 and Wt are the initial and final weights (g); t represents the trial days; F is the total feed intake of each cage (g); N represents the total number of fish in each cage; G1, G2, G3, and G4 are the visceral weight (g), liver weight (g), intraperitoneal fat weight (g), and intestine weight (g), respectively; Wb represents the final weight of each fish (g); L1 and L represents the intestine length (cm) and body length (cm); and L3 represents for cube of body length (cm3).

2.7 Data statistics and analysis

All data are presented as means ± SEM. The data between the control group and the OB group were analyzed by independent-samples t-test with SPSS 22.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). When analyzing the data among OB, RB1, and RB2 groups, Levene’s test was firstly performed to check if the data conform to normality and homogeneity. For data conforming to the assumptions (P > 0.05), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-range test was used to compare significant differences among those groups. Otherwise, nonparametric test was performed.

3 Results

3.1 Effect of recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ on feed intake

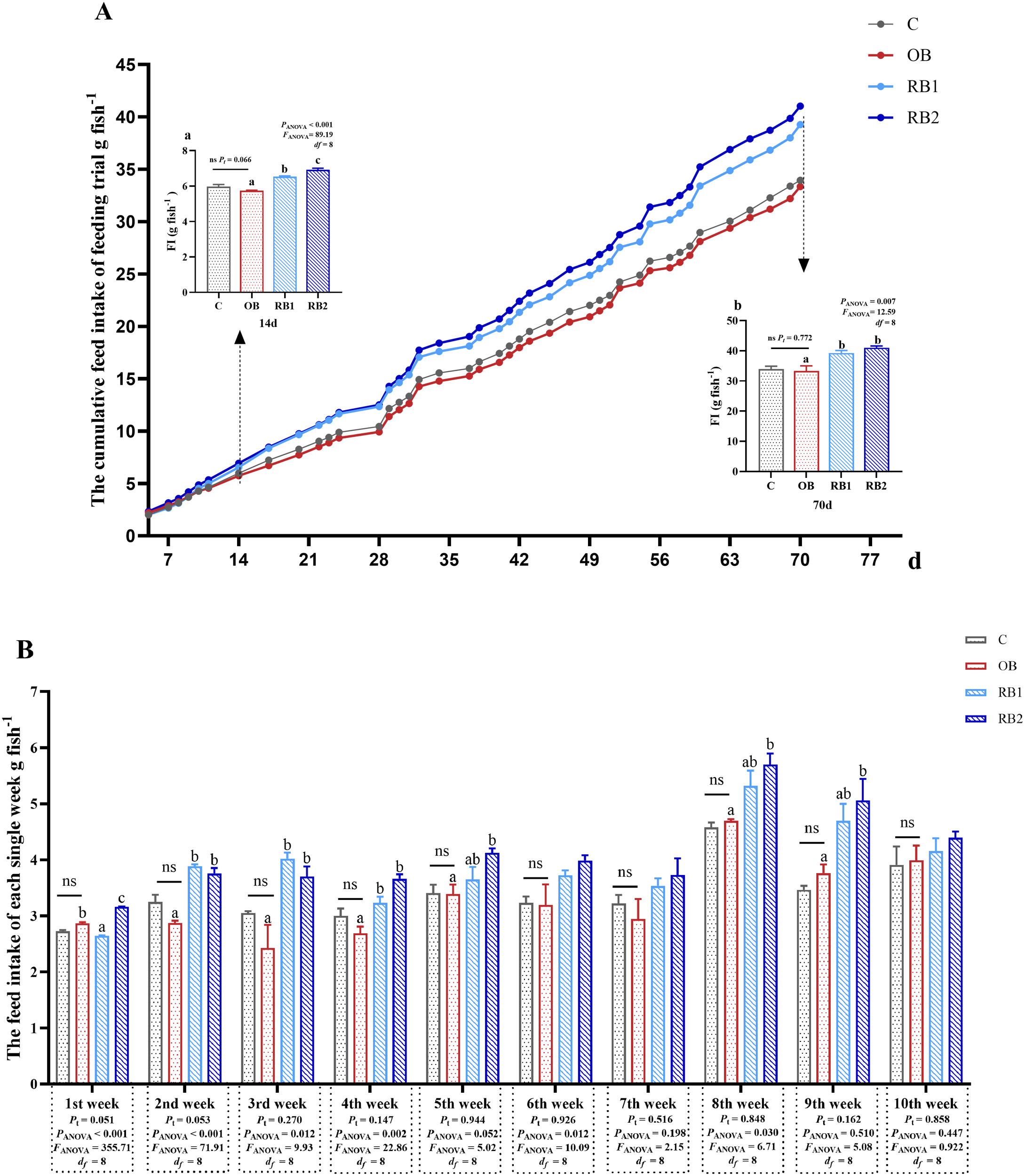

In terms of the entire feeding trial, no statistical difference on the cumulative FI was observed between the control group and the OB group (P > 0.05) (Figure 1A). However, from the 14th day, RB supplementation significantly promoted cumulative FI (P < 0.05), and this influence lasted even until the end of the trial (P < 0.05). As shown in Figure 1B, an analysis of weekly total FI revealed no significant difference between the OB and control groups (P > 0.05). Over the 10-week period, the FI of the RB groups exhibited a gradually increasing trend. Specifically, the FI of the RB2 group was significantly higher than that of the OB group in the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, eighth, and ninth weeks (P < 0.05).

Figure 1

Feed intake of blunt snout bream fed different experiment diets. OB, original bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65; RB, recombinant bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′. (A) Effect of different diets on cumulative feed intake of the feeding trial. (a) Cumulative feed intake of the first 14 days. (b) Cumulative feed intake of 70 days of feeding trial. (B) Effect of different diets on feed intake of each week. nsP > 0.05, compared between the control group and the OB group analyzed by independent-samples t-test. abccompared among the OB group, RB1 group, and RB2 group by using one-way ANOVA. Values in the same line with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

3.2 Effect of recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ on growth performance and organ coefficient

As shown in Figure 2, there was no statistical difference on WGR and SGR between the control group and the OB group (P > 0.05). Additionally, WGR and SGR showed an increased trend in the OB, RB1, and RB2 groups, and this trend was significant (P < 0.05) in the RB2 group. However, FCR showed no significance among all treatments (P > 0.05).

Figure 2

Growth performance and organ coefficient of blunt snout bream fed different experiment diets. OB, original bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65; RB, recombinant bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′. (A) WGR, weight gain rate. (B) SGR, specific growth rate. (C) FCR, feed conversion radio. (D) CF, condition factor. (E) VSI, visceral somatic index. (F) HSI, hepatosomatic index. (G) IPE, intraperitoneal fat radio. (H) ISI, intestine somatic index. (I) ILI, intestine length index. *P < 0.05, nsP>0.05, compared between the control group and the OB group analyzed by independent-samples t-test. abcompared among the OB group, RB1 group, and RB2 group by using one-way ANOVA. Values in the same line with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

No statistical differences were observed in CF, ISI, and ILI among all of the groups (P > 0.05). However, OB could significantly increase VSI (P < 0.05), while the opposite was found for HSI (P < 0.05). However, with the addition of RB, VSI was lowered first and then raised and was lowest in the RB1 group (P < 0.05). Furthermore, RB could increase IPE, with the highest value observed at a dosage of 1×109 CFU/kg (P < 0.05).

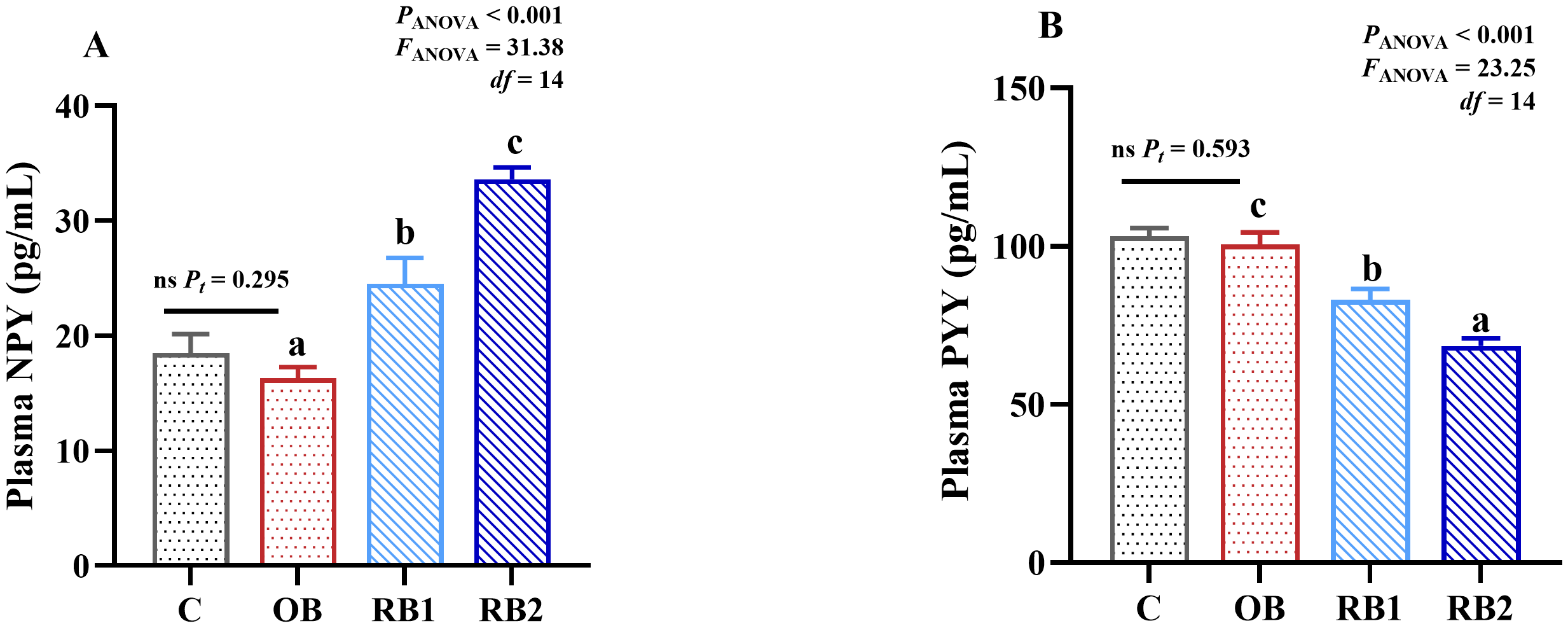

3.3 Effect of recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ on plasma NPY and PYY levels

No significant differences were observed between the control and the OB group in plasma NPY and PYY (P > 0.05), whereas RB addition significantly increased the levels of NPY and decreased PYY (P < 0.05), with RB2 showing the most significant effect (P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Plasma neuropeptide Y (NPY) and peptide YY (PYY) concentrations of blunt snout bream fed different experiment diets. OB, original bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65; RB, recombinant bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′. (A) Plasma NPY (pg/mL). (B) Plasma PYY (pg/mL). nsP > 0.05, compared between the control group and the OB group analyzed by independent-samples t-test. abccompared among the OB group, RB1 group, and RB2 group by using one-way ANOVA. Values in the same line with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

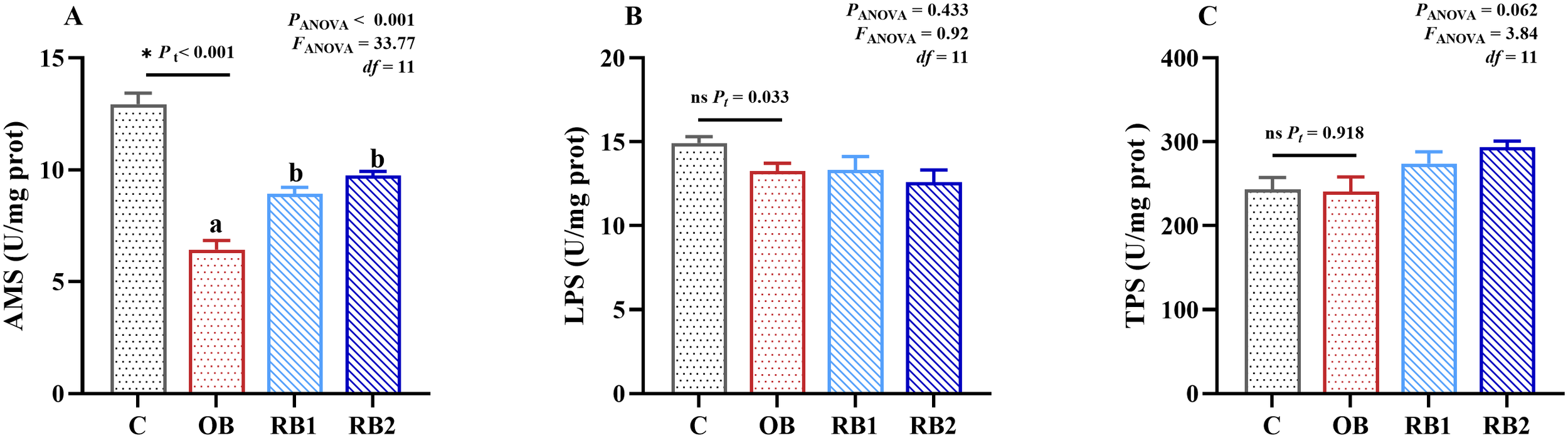

3.4 Effect of recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ on intestinal digestive enzyme activity

There were no statistical differences on LPS and TPS among all treatments (Figure 4). However, it was found that B. subtilis addition can significantly decrease the activity of AMS (P < 0.05). Supplying RB can mitigate this situation (P < 0.05) but cannot reach the same level as the control group.

Figure 4

Intestinal digestive enzyme activity of blunt snout bream fed different experiment diets. OB, original bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65; RB, recombinant bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′. (A) α-amylase (U/mg prot). (B) Lipase (U/mg prot). (C) total trypsin (U/mg prot). *P < 0.05; nsP > 0.05, compared between the control group and the OB group analyzed by independent-samples t-test. abcompared among the OB group, RB1 group, and RB2 group by using one-way ANOVA. Values in the same line with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

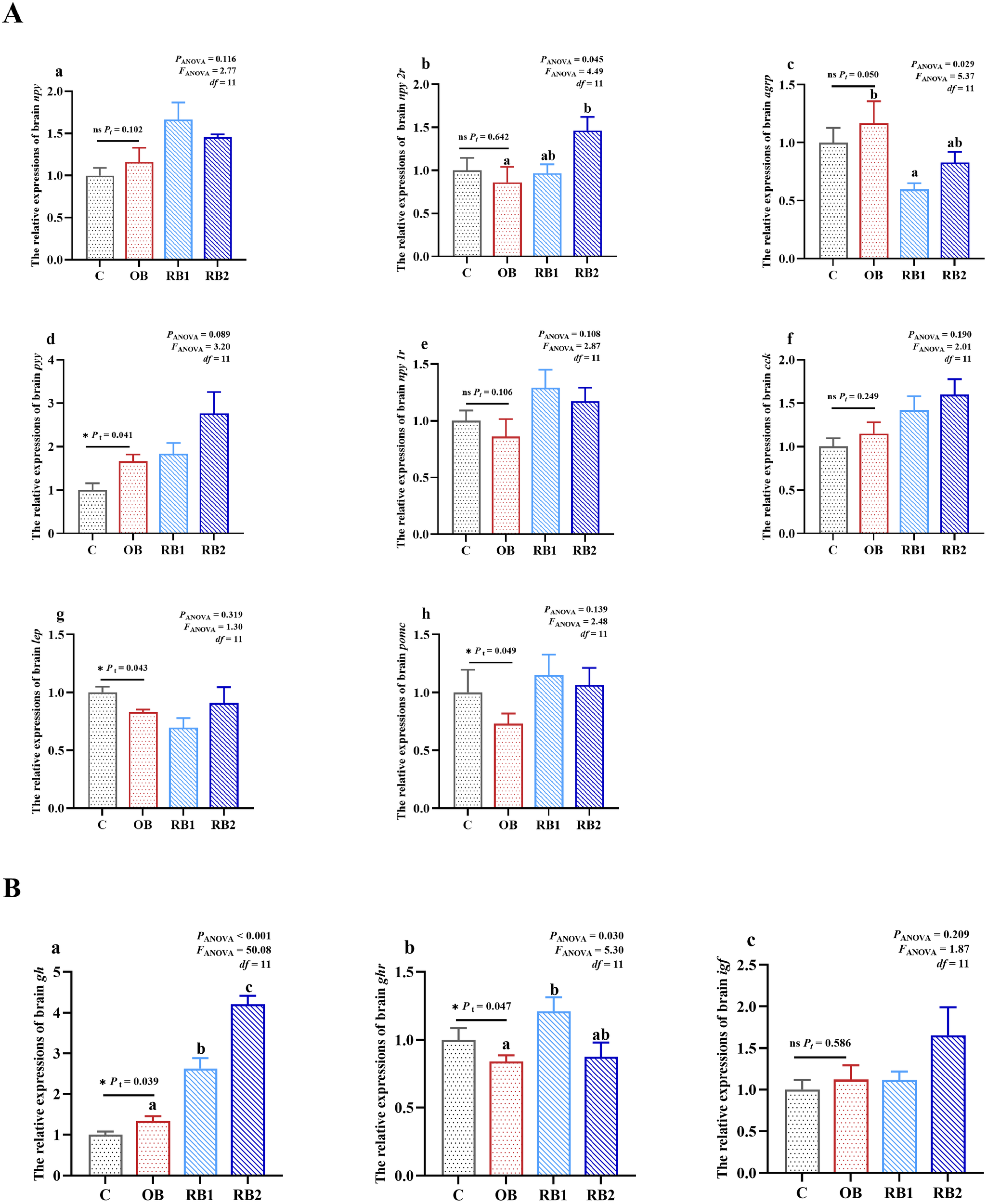

3.5 Effect of recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ on the transcription of brain appetite-regulating and growth-related genes

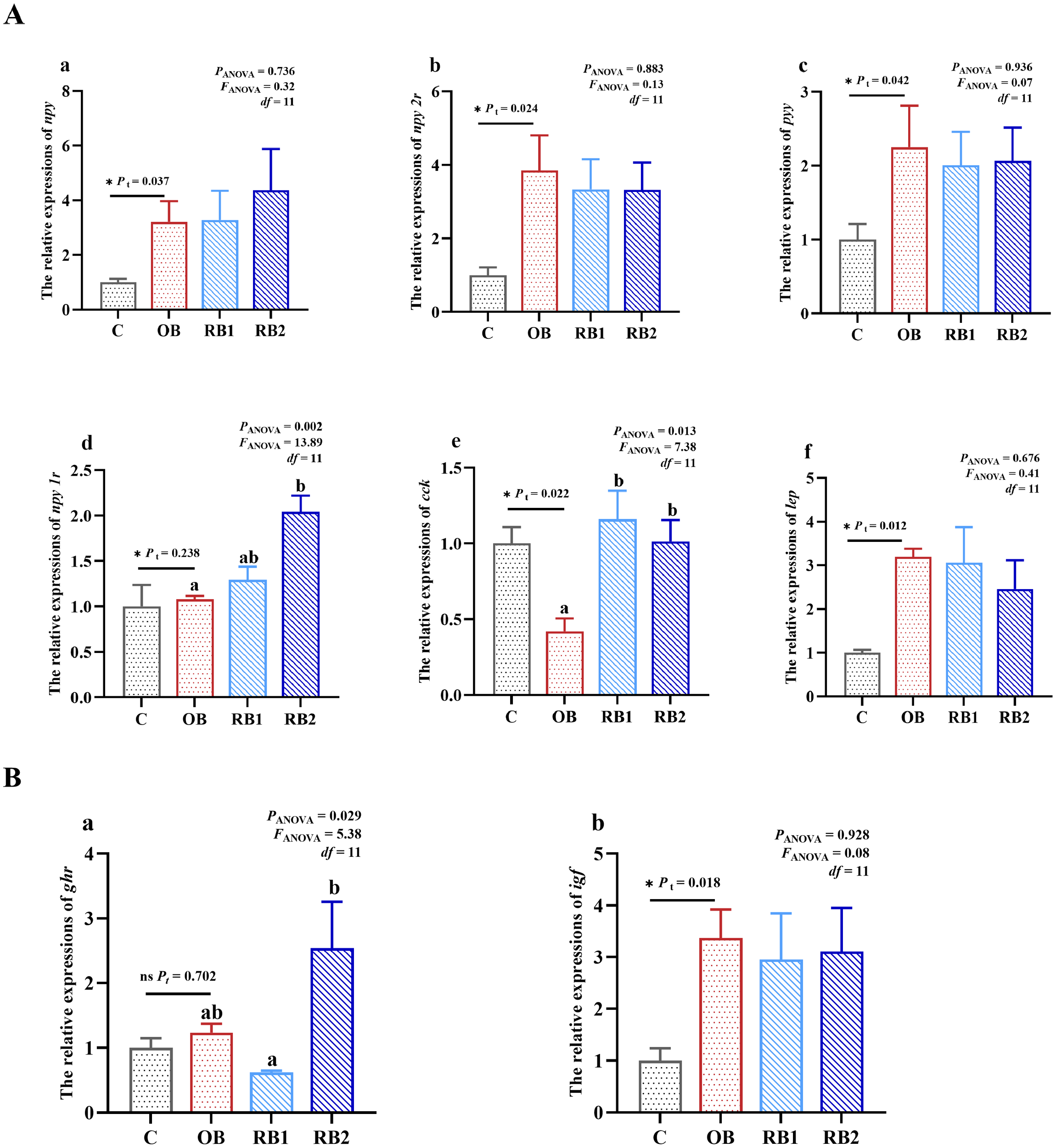

As shown in Figure 5, there was little difference observed in the expression of npy, igf, cck, and npy 1r among all treatments (P > 0.05). However, the mRNA transcriptions of gh and pyy were both significantly higher in the OB group compared with the control group (P < 0.05), but the opposite was presented in ghr, pomc, and lep (P < 0.05). The expression of gh showed a significant dose-dependent increase with the graded addition of RB (P < 0.05). The transcription of ghr and npy 2r both tended to be upregulating while respectively significant in the RB1 group and the RB2 group (P < 0.05). However, an opposite result was noted in agrp, and its transcription was lowest in the RB1 group (P < 0.05).

Figure 5

Relative mRNA transcriptions of brain appetite-regulated and growth-related genes of blunt snout bream fed different experiment diets. OB, original bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65; RB, recombinant bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′. (A) Relative mRNA transcriptions of brain appetite-regulated genes. Relative transcriptions of npy (a), npy 2r (b), agrp (c), pyy (d), npy 1r (e), cck (f), lep (g), and pomc (h). (B) Relative mRNA transcriptions of brain GH–IGF axis. Relative transcriptions of gh (a), ghr (b), and igf (c). *P < 0.05; nsP > 0.05, compared between the control group and the OB group analyzed by independent-samples t-test. abcompared among the OB group, RB1 group, and RB2 group by using one-way ANOVA. Values in the same line with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

3.6 Effect of recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ on the transcription of intestine appetite-regulating and growth-related genes

The transcription of appetite-regulating genes in the intestine was not exactly the same as observed in the brain. Comparing the OB group with the control group, the transcription of igf, npy, npy 2r, pyy, and lep all had a significant upregulation (P < 0.05), while an opposite result was presented on cck (P < 0.05) (Figure 6). The expression of npy 2r was higher in the RB2 group than the OB group (P < 0.05), while the expression of cck in both the RB1 group and the RB2 group was significantly higher than that in the OB group (P < 0.05).

Figure 6

Relative mRNA transcriptions of intestinal appetite-regulated and growth-related genes of blunt snout bream fed different experiment diets. OB, original bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65; RB, recombinant bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′. (A) Relative mRNA transcriptions of intestinal appetite-regulated genes. Relative transcriptions of npy (a), npy 2r (b), pyy (c), npy 1r (d), cck (e), and lep (f). (B) Relative mRNA transcriptions of intestinal GH–IGF axis. Relative transcriptions of ghr (a) and igf (b). *P < 0.05; nsP > 0.05, compared between the control group and the OB group analyzed by independent-samples t-test. abcompared among the OB group, RB1 group, and RB2 group by using one-way ANOVA. Values in the same line with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

3.7 Effect of recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ on the mRNA transcription of intestinal tight junction proteins and absorption-related genes

No significant difference was observed in the expression of claudin-3c and occludin between the control group and the OB group (P > 0.05), whereas the transcription of claudin-4l was significantly upregulated in the OB group (P < 0.05) (Figure 7A). Supplying B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ can significantly elevate the mRNA transcription of occludin (P < 0.05). The expression of claudin-3c was significantly higher in the RB1 group, while the expression of claudin-4l was higher in the RB2 group compared with those in the OB group (P < 0.05).

Figure 7

Relative mRNA transcriptions of intestinal tight junction proteins and absorption-related genes of blunt snout bream fed different experiment diets. OB, original bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65; RB, recombinant bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′. (A) Relative mRNA transcriptions of intestinal tight junction proteins. Relative transcriptions of claudin 3c (a), claudin 4l (b), and occludin (c). (B) Relative mRNA transcriptions of intestinal absorption-related genes. *P < 0.05; nsP > 0.05, compared between the control group and the OB group analyzed by independent-samples t-test. abcompared among the OB group, RB1 group, and RB2 group by using one-way ANOVA. Values in the same line with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

As shown in Figure 7B, the mRNA expressions of slc7a8 and slc7a9 were significantly lower in the OB group compared with the control group (P < 0.05). The transcriptions of slc7a7, slc7a5 as well as slc6a14 were significantly upregulated when the dietary RB level was 1 × 109 CFU/kg (P < 0.05). With the dose up, the mRNA expressions of slc6a19b and slc7a9 were significantly higher than the OB group, while no significance was observed between the RB1 group and the RB2 group (P > 0.05). However, the expression of slc7a6 was significantly higher and higher (P < 0.05).

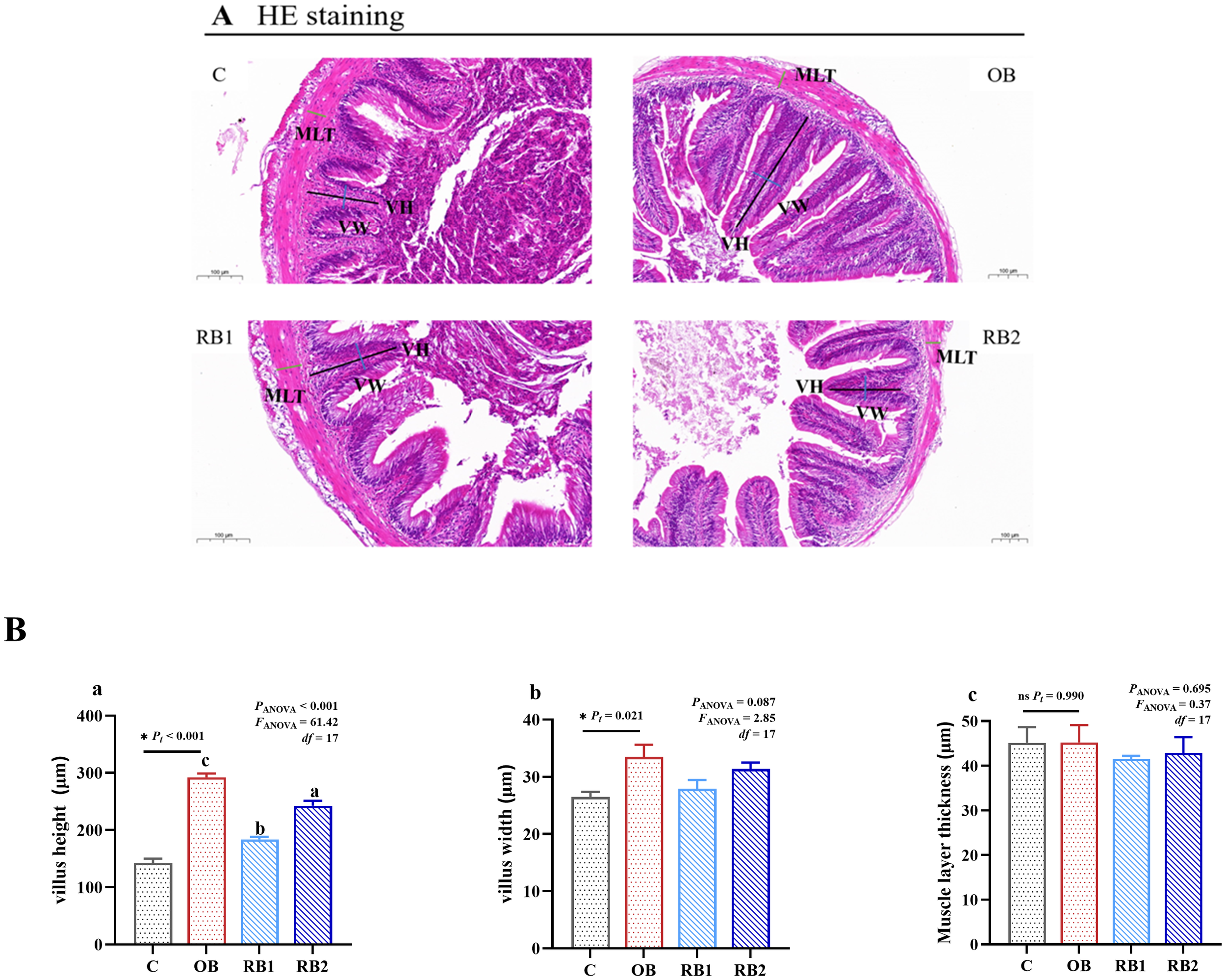

3.8 Effect of recombinant B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ on histological observation of the intestine

Little difference was observed on MLT among all treatments (P > 0.05) (Figure 8). Supplying OB can significantly increase VH and VW compared with the control group. However, with dietary supplied RB, there was a deep decrease on VH (P < 0.05). Upon reaching the dose of 1 × 109 CFU/kg (the RB2 group), VH significantly increased compared with the RB1 group but was still significantly lower than the OB group (P < 0.05).

Figure 8

Intestinal structure of blunt snout bream fed different experiment diets. OB, original bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65; RB, recombinant bacteria—Bacillus subtilis CM65-Patt′. (A) Histological observations of the intestine stained with H&E (magnification ×100; scale bars, 100 μm; villus height, black line; villus weight, blue line; muscular layer thickness, green line). (B) (a) Villus height, (b) villus width, and (c) muscular layer thickness. *P < 0.05; nsP > 0.05, compared between the control group and the OB group analyzed by independent-samples t-test. abcompared among the OB group, RB1 group, and RB2 group by using one-way ANOVA. Values in the same line with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

4 Discussion

Changes in feed intake and growth performance are the key apparent indicators to assess the effectiveness of an aquafeed attractant. Previous research showed that dietary-supplied B. subtilis had a positive effect on growth in many aquatic animals such as Oreochromis niloticus, Penaeus vannamei, and Rhamdia quelen (Alves et al., 2024; Cao et al., 2022; Liao et al., 2023; Rodigues et al., 2021). In this study, the addition of B. subtilis CM65 has no significant impact on the growth performance of blunt snout bream. The same occurred in the study of Xiong et al. (2024) using a dietary supplement of 2 × 107–2 × 109 CFU/kg B. subtilis CM65 for which no significant impacts on the growth performance of juvenile blunt snout bream were observed, while it was found that 1 × 108 –1 × 109 CFU/kg B. subtilis CM65 supplied can significantly promote the weight gain of Chinese mitten crab (He et al., 2024). However, the effect of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ on the FI of blunt snout bream was positive and significant. Firstly, the difference of cumulative FI among all treatments indicated that the superior feeding behavior promoted by the use of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ was completely apparent in the early stage of the feeding trial. Moreover, as shown by the changes in weekly FI, this beneficial effect did not diminish as the feeding trial progressed, which indicated that the feeding stimulation advantage of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ was long lasting. These data were also an indication that the Patt peptide successfully expressed from B. subtilis was functional. With increasing intake, there were bound to be effects on fish growth. Given that the relative molecular mass of Patt is only 1,100 Da, it has been proposed that short peptides (180–1,500 Da) could be absorbed directly by the intestine without consuming energy (Guo et al., 2009; Rashidian et al., 2021). Consequently, it is unsurprising that both SGR and WGR increased significantly when the addition of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ reached 1 × 109 CFU/kg. CF is a common index to represent the wellbeing of fish. However, not only B. subtilis CM65 but also the peptide added had a significant impact on it. Additionally, dietary supplementation with 1 × 109 CFU/kg B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ significantly increased IPE, suggesting that the lipogenic pathway might be activated due to the increase in feed intake (Liu et al., 2024).

In order to further assess the effect of OB and RB on appetite induction, we measured the hormone levels and gene expression of appetite-related factors in blunt snout bream. The results showed that the plasma levels of NPY and PYY had no significant differences between the control and OB groups, suggesting that the addition of OB in diet did not affect the appetite of fish. Notably, both NPY and PYY are widely expressed in the central nervous system and intestine of fish. While NPY is acting as an appetite stimulant, PYY does the opposite. This may also explain why the differences in FI were not significant. The increase in feed intake might be due to the appetite regulatory system activated, which mainly consists of the central nervous system (CNS) (brain) and peripheral organs (intestine). Appetite-stimulating hormones and anorexigenic hormones were transported via the blood to regulate the activity of the cells for appetite regulation (Bertucci et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2019). In addition, the transcription of intestinal appetite stimulant factor npy and its receptor npy 2r as well as appetite suppressant factor pyy (also pyy in the brain), respectively, were all significantly increased while remarkably decreasing appetite suppressant factors pomc and lep of brain and cck in the intestine. Although similar transcription trends of npy and pyy in the intestine may lead to stable intestinal hormone levels, they exert specific action via different NPY Y receptors (Cox et al., 2010) and NPY binding with NPY 2r, while PYY is binding its cognate receptor NPY 1r (Hyland et al., 2003; Tough et al., 2006). Increased intestinal mRNA expression of the npy 2r suggested that NPY played a more efficient and important role in the intestine. Though the transcription of appetite suppressant factors pomc and lep in the brain was significantly reduced, the expression of lep in the intestine was remarkably increased. This is explained by the following two reasons: Firstly, the CNS might not be as sensitive as the peripheral appetite regulatory system to the extinction of appetite (Sabioni et al., 2022). Secondly, the retention of incompletely digested food in the intestine may lead to a higher expression of lep in the intestine (Huang et al., 2019). However, the hormone levels and the expression of appetite-regulating genes were changed as B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ was added. As the dose rose, the plasma NPY increased significantly while PYY decreased sharply. Plasma hormone levels can roughly reflect the overall levels in the organism, noting that the blunt snout bream of the RB1 and RB2 groups may have been in a chronic state of hyperphagia (Zhang et al., 2022), which led to higher FI compared to the OB group. When B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ was added at 1 × 108 CFU/kg, the expression of agrp in the brain was significantly downgraded during the transcriptional upregulation of cck in the intestine. As the supplement was increased to 1 × 109 CFU/kg, there was an upregulation trend of agrp, but the expression of npy 1r and cck were both remarkably higher than in the OB group. These data indicated that the hormone expression was regulated to maintain a stable internal environment. In addition, although the mRNA expression of npy (in the brain and intestine) and igf (in the intestine) was not significantly upregulated, they were maintained at a high level of expression. The expression of appetite-regulating genes was frequently used to assess the practical effects of novel feed ingredients and feed additives on aquatic animals. It has been reported that dietary-supplied 6-g/kg cottonseed meal protein can upregulate the transcription of npy and npy r to promote Chinese mitten crab feeding (Cheng et al., 2019). However, the increased expression of hypothalamus cck indicated the negative effect on the consumption by Salminus brasiliensin fed vegetable-based diet supplied with 180 g/kg swine liver hydrolysate (Lorenz et al., 2022). In this study, the blunt snout bream dietary supplement of 1 × 109 CFU/kg B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ had the best positive effect on appetite regulation. It might also be the Patt peptide functions that lead to homeostasis. Previous research had indicated that small peptides not only have specific flavors themselves but also strengthen the flavor by enhancing or masking the flavor of other substances (Agyei, 2015; Wang and De Mejia, 2005). Small polyglutamic acid peptides can mask the bitter taste present in protein hydrolysates and thus improve the palatability of protein hydrolysates (Ball et al., 2004). Research has shown that adding an appropriate amount of a small peptide to the diet of Chinese mitten crab can have a better effect on feed attraction (Wang L. et al., 2024). In addition, the relative expression of growth-related genes (GH with its receptor GHR and IGF1) was investigated to further interpret the growth performance results. The GH–IGF1 axis has been demonstrated to play a key role in regulating blunt snout bream growth (Liu et al., 2024). As an important growth promoter, GH binds to its receptor GHR to stimulate the production of IGF1, which, in turn, increases the growth performance of fish (Zhong et al., 2012). In our research, diets supplemented with 1 × 108 CFU/kg B. subtilis CM65 remarkably increased the transcription of brain gh as well as intestine igf1, while the opposite igf1 expression trends were observed in the brain, which might be caused by the negative feedback regulation that exists between IGF1 and GH (Liu et al., 2024). All of the results above indicated that B. subtilis CM65 can activate the GH–IGF1 axis of blunt snout bream, but no significant effect was found on the growth. Furthermore, with the additional dose of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′, the expression of brain gh kept increasing significantly. It can also remarkably increase the expression of brain ghr with the addition of 1 × 108 CFU/kg B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ and of intestinal ghr at the dose of 1 × 109 CFU/kg. These indicated that B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ had a more conducive function to promote the growth performance of blunt snout bream than B. subtilis CM65, which could also explain the differences in SGR among all treatments.

The increase in feed intake might mainly be regulated by appetite, but it does not mean increased feed intake is positively correlated with growth performance in fish, which also depends on the structural and functional (digest and absorb) integrity of the intestine (Dawood et al., 2021). ISI and ILI, which are commonly presented as proxy for intestinal development (Wen et al., 2014), had no significant changes among OB or RB in this study. To further investigate the integrity of the structure, the transcription of tight junction proteins (Claudin 3c, Occludin, and Claudin 4l), which can maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier (Li et al., 2023), was investigated. Research has revealed that B. subtilis can improve intestinal barrier function by upregulating the expression of claudin and occludin to promote defensins and mucin formation and regulate the immune function in the intestine (Chang et al., 2021, 2023; Pothuraju et al., 2021). In this study, B. subtilis CM65 can remarkably upregulate the transcription of claudin-4l. In addition, with dietary supplement of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ raised from 1 × 108 CFU/kg to 1 × 109 CFU/kg, the transcription of claudin-3c significantly upregulated at first and then decreased, while the opposite was observed in claudin-4l. B. subtilis CM65 supplementation also had a positive effect on occluding. The results above indicated that B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ (or Patt) is more conducive to use to maintain intestinal barrier health than B. subtilis CM65.

Digestive efficiency, which can be directly assessed by the activities of digestive enzymes, is a key determinant of growth performance (Javahery et al., 2019). B. subtilis, a class of probiotics widely used in aquaculture, has been substantiated to improve the digestive enzyme activities in many aquatic animals like Catla, Pagrus major, Litopenaeus vannamei, and Oreochromis niloticus (Bhatnagar and Raparia, 2020; Monier et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2021; Zaineldin et al., 2018). The observed increased digestibility of nutrients may be the result of probiotic supplementation, which increases the availability of nutrients in diets (Mohapatra et al., 2012). However, in this study, neither the addition of B. subtilis CM65 nor B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ had an insignificant effect on the activities of LPS and TBS in blunt snout bream. Moreover, B. subtilis CM65 can remarkably decrease AMS activity compared with the control group. Dietary supplied B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ was effective in mitigating the decline in AMS but could not restore the same level of enzyme activity as in the control group. This result may be attributed to the amount of additive and strain specificity of B. subtilis (Ghosh, 2025). Moreover, this may explain the reason why there was no difference in WGR and SGR between the control group and OB groups. Diets supplemented with probiotics are easier to digest because probiotics can have the potential to synthesize digestive enzymes (Dawood et al., 2019; Ringo et al., 2020), which indicates that supplemented B. subtilis CM65 might act to augment AMS activity after settling in the intestinal tract of blunt snout bream, resulting in a reduction in enzyme activity by the host. Furthermore, the decrease in AMS is evidence of the development of pancreatic exocrine secretion in larval fish (Cai et al., 2015), which indicates that B. subtilis CM65 can promote the development of pancreatic exocrine secretion. However, a further in-depth study is needed to elucidate this assumption.

The structural integrity of the intestine is essential for the effective absorption of nutrients. Thus, the intestinal villi are not only closely involved in absorbing nutrients, but they also help to expel harmful microorganisms through their regular movement (Wang et al., 2022). In this study, compared with the control group, the VH and VW of the OB group increased significantly, which indicated that B. subtilis CM65 can promote intestinal development. Normally, the length of the intestinal villi indicates the metabolic rate of the intestinal epithelial cells and reflects the secretory function of the intestinal tract of an animal organism (Wang et al., 2018). VH and VW determine the area of contact between the intestinal villi and the chyme. However, when the addition of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ was 1 × 108 CFU/kg, there was a sharp decline in VH. The decline might be caused by the higher FI, which increased stress on the intestinal tract (always stays overloaded) and, in turn, had a negative effect on the growth of the intestinal villi (Xia et al., 2020). However, with a dose of up to 1 × 109 CFU/kg, this situation was improved somehow. The result was parallel with earlier studies (Chang et al., 2021; Du et al., 2021), indicating an appropriate dose of B. subtilis to induce favored intestinal development. In addition, B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ can reduce MLT to a certain extent. As the thickness of the muscle layer decreased, intestinal permeability increased and, in turn, intestinal absorption was enhanced (Cadangin et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2024). This implied that B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ can improve the absorption capacity for blunt snout bream.

The intestinal absorption of amino acids (AAs), which are crucial nutrients, is facilitated by their respective specific transporters (Verri et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). In this study, B. subtilis CM65 supplementation significantly downgraded the transcription of slc7a8 (encoding LAT2 protein) and slc7a9 (encoding a subunit of b0,+AT1 amino acid transporter), which can mainly transform neutral AAs (Yuan et al., 2020). The decreased absorptions of neutral AAs might be a cause of the decrease in WGR. In addition, dietary B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ supplementation was found to increase the transcription of amino acid transporters to enhance the intestine absorption capacity. The y+L transport system, consisting of y+LAT1 (encoded by slc7a7) and y+LAT2 (encoded by slc7a6), which can transport cationic and neutral AAs, was activated with the dose of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ used in this study. In addition, other neutral AA transporters like B0AT1 (encoded by slc6a19b), LAT1 (encoded by slc7a5), and LAT2 as well as cationic AA transporter ATB0,+ (encoded by slc7a6) were significantly activated when the dose of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ was 1 × 109 CFU/kg. This also indicated that the bioavailability of nutrients from feed in the RB2 group was increased, thereby promoting fish growth. Although numerous studies indicated that diets supplemented with B. subtilis are easier to absorb (Liaqat et al., 2024; Mohammadi et al., 2020; Saravanan et al., 2021), up to now, the specific mechanism on how it promotes the expressions of AA transporters remained unknown. The possibilities are as follows: On the one hand, increased FI could lead to an upregulation of intestinal absorption and thus reach a healthy state for the organism (Sheng et al., 2023). On the other hand, probiotics colonizing the intestine can assist in digestion, leading to an increase in free amino acid contents that, in turn, leads to the increasing mRNA expression of respective transporters (Poncet and Taylor, 2013). Overall, the elevated gene expression observed is partly accounted for by the effective use of protein feed sources as well as the enhanced intestinal absorption capacity.

5 Conclusion

This current study indicated that B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ has the potential to serve as an attractant added to the aquafeed of blunt snout bream. Dietary supplementation of B. subtilis CM65-Patt′ at 1 × 109 CFU/kg was associated with stimulated appetite, increased feed intake, promoted growth, maintained intestinal integrity, and enhanced intestinal functions (digestive and absorptive). Furthermore, after the 10-week feeding trial, this supplementation resulted in a significant 26.59% increase in feed intake and a consequent 17.26% increase in the final body weight of the fish. Those improved capacities observed in blunt snout bream might be attributed to the secret ion of the Patt peptide by B. subtilis CM65-Patt′. Patt might activate the NPY-PYY brain–intestine appetite regulatory axis for feeding and the GH–IGF1 axis for growth (based on gene expression data). This study might hold significant importance for developing effective peptide feed attractants for modern intensive aquaculture. However, since the pBE plasmid used in this study carries antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), the proactive mitigation of ARGs spread is a non-negotiable prerequisite for any consideration of its application in commercial feed.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by The Animal Care and Use Committee at Nanjing Agriculture University granted permission (license number: SYXK (Su)2021-0086). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XYC: Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. JZ: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SX: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Resources. BY: Software, Resources, Writing – review & editing. ZL: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Software. XW: Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. XT: Writing – review & editing, Resources. XL: Software, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. GJ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. WL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. XS: Software, Writing – review & editing. XX: Writing – review & editing, Software. XFC: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFD2402000) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M751453).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Agyei D. (2015). Bioactive proteins and peptides from soybeans. Recent Patents Food Nutr. Agric.7, 100–107. doi: 10.2174/2212798407666150629134141

2

Alves A. P. D. Orlando T. M. De Oliveira I. M. Libeck L. T. Silva K. K. S. Rodrigues R. A. F. et al . (2024). Synbiotic microcapsules of Bacillus subtilis and oat β-glucan on the growth, microbiota, and immunity of Nile tilapia. Aquac Int.32, 3869–3888. doi: 10.1007/s10499-023-01355-6

3

AOAC (2005). Official methods of official analytical chemists international. 16th ed (Arlington, VA: Association of Official Analytical Chemists).

4

Ball L. E. Garland D. L. Crouch R. K. Schey K. L. (2004). Post-translational modifications of Aquaporin 0 (AQP0) in the normal human lens: Spatial and temporal occurrence. Biochemistry43, 9856–9865. doi: 10.1021/bi0496034

5

Ballester-Moltó M. Sanchez-Jerez P. Cerezo-Valverde J. Aguado-Giménez F. (2017). Particulate waste outflow from fish-farming cages. How much is uneaten feed? Mar. pollut. Bull.119, 23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.03.004

6

Bertucci J. I. Blanco A. M. Sundarrajan L. Rajeswari J. J. Velasco C. Unniappan S. (2019). Nutrient regulation of endocrine factors influencing feeding and growth in fish. Front. Endocrinol.10. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00083

7

Bhatnagar A. Raparia S. (2020). Evaluation of probiotic adequacy, immunomodulatory effects and dosage application of Bacillus coagulans in formulated feeds for Catla (Hamilton 1822). Int. J. Aquat. Biol-IJAB8, 194–208.

8

Cadangin J. Lee J. H. Jeon C. Y. Lee E. S. Moon J. S. Park S. J. et al . (2024). Effects of dietary supplementation of Bacillus, β-glucooligosaccharide and their synbiotic on the growth, digestion, immunity, and gut microbiota profile of abalone, Haliotis discus hannai. Aquac Rep.35, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102027

9

Cai Z. N. Li W. J. Mai K. S. Xu W. Zhang Y. J. Ai Q. H. (2015). Effects of dietary size-fractionated fish hydrolysates on growth, activities of digestive enzymes and aminotransferases and expression of some protein metabolism related genes in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) larvae. Aquaculture440, 40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.01.026

10

Calo J. Comesaña S. Fernández-Maestú C. Blanco A. M. Morais S. Soengas J. L. (2024). Impact of feeding diets with enhanced vegetable protein content and presence of umami taste-stimulating additive on gastrointestinal amino acid sensing and feed intake regulation in rainbow trout. Aquaculture579, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.740251

11

Cao H. Z. Chen D. D. Guo L. F. Jv R. Xin Y. T. Mo W. et al . (2022). Effects of Bacillus subtilis on growth performance and intestinal flora of Penaeus vannamei. Aquac Rep.23, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2022.101070

12

Chang X. L. Kang M. R. Shen Y. H. Yun L. L. Yang G. K. Zhu L. et al . (2021). Bacillus coagulans SCC-19 maintains intestinal health in cadmium-exposed common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) by strengthening the gut barriers, relieving oxidative stress and modulating the intestinal microflora. Ecotoxicol Environ. Saf.228, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112977

13

Chang X. L. Kang M. R. Yun L. L. Shen Y. H. Feng J. C. Yang G. K. et al . (2023). Sodium gluconate increases Bacillus velezensis R-71003 growth to improve the health of the intestinal tract and growth performance in the common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Aquaculture563, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738980

14

Chen W. L. Ge Y. P. Sun M. He C. F. Zhang L. Liu W. B. et al . (2022). Insights into the correlations between prebiotics and carbohydrate metabolism in fish: Administration of xylooligosaccharides in Megalobrama amblycephala offered a carbohydrate-enriched diet. Aquaculture561, 738684. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738684

15

Chen S. H. Li P. H. Chan Y. J. Cheng Y. T. Lin H. Y. Lee S. C. et al . (2023). Potential anti-sarcopenia effect and physicochemical and functional properties of rice protein hydrolysate prepared through high-pressure processing. Agric. Basel13, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13010209

16

Cheng H. H. Liu M. Y. Yuan X. Y. Zhang D. D. Liu W. B. Jiang G. Z. (2019). Cottonseed meal protein hydrolysate stimulates feed intake and appetite in Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Aquac Nutr.25, 983–994. doi: 10.1111/anu.12916

17

Conti F. Olivotto I. Cattaneo N. Pavanello M. Sener I. Antonucci M. et al . (2024). The promising role of synthetic flavors in advancing fish feeding strategies: A focus on adult female zebrafish (Danio rerio) growth, welfare, appetite, and reproductive performances. Animals14, 1–19. doi: 10.3390/ani14172588

18

Cox H. M. Tough I. R. Woolston A. M. Zhang L. Nguyen A. D. Sainsbury A. et al . (2010). Peptide YY is critical for acylethanolamine receptor gpr119-induced activation of gastrointestinal mucosal responses. Cell Metab.11, 532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.04.014

19

Dawood M. A. O. Ali M. F. Amer A. A. Gewaily M. S. Mahmoud M. M. Alkafafy M. et al . (2021). The influence of coconut oil on the growth, immune, and antioxidative responses and the intestinal digestive enzymes and histomorphometry features of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Physiol. Biochem.47, 869–880. doi: 10.1007/s10695-021-00943-8

20

Dawood M. A. O. Koshio S. Abdel-Daim M. M. Van Doan H. (2019). Probiotic application for sustainable aquaculture. Rev. Aquac11, 907–924. doi: 10.1111/raq.12272

21

Du R. Y. Zhang H. Q. Chen J. X. Zhu J. He J. Y. Li L. et al . (2021). Effects of dietary Bacillus subtilis DSM 32315 supplementation on the growth, immunity and intestinal morphology, microbiota and inflammatory response of juvenile largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides. Aquac Nutr.27, 2119–2131. doi: 10.1111/anu.13347

22

Ghosh T. (2025). Recent advances in the probiotic application of the Bacillus as a potential candidate in the sustainable development of aquaculture. Aquaculture594, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741432

23

Guo H. Kouzuma Y. Yonekura M. (2009). Structures and properties of antioxidative peptides derived from royal jelly protein. Food Chem.113, 238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.06.081

24

He C. F. Liu W. B. Zhang L. Chen W. L. Liu Z. S. Li X. F. (2023). Cottonseed meal protein hydrolysate improves the growth performance of chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) by promoting the muscle growth and molting performance. Aquac Nutr.2023, 1–13. doi: 10.1155/2023/8347921

25

He C. F. Xiong W. Li X. F. Jiang G. Z. Zhang L. Liu Z. S. et al . (2024). The P4' Peptide-Carrying Bacillus subtilis in Cottonseed Meal Improves the Chinese Mitten Crab Eriocheir sinensis Innate Immunity, Redox Defense, and Growth Performance. Aquac Nutr.2024, 1–13. doi: 10.1155/2024/3147505

26

Hu R. G. Yang B. T. Zheng Z. Y. Liang Z. L. Kang Y. H. Cong W. (2024). Improvement of non-specific immunity, intestinal health and microbiota of crucian carp (Carassius auratus) juvenile with dietary supplementation of Bacillus coagulans BC1. Aquaculture580, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.740327

27

Huang Y. Chu X. Cao X. Wang X. Guo H. Hua H. et al . (2025). Effects of oxidized soybean meal and oxidized soybean oil on growth, intestinal oxidative stability, inflammation, structure, digestive and absorptive capacity of Megalobrama amblycephala. Aquaculture603, 742394. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.742394

28

Huang C. C. Sun J. Ji H. Oku H. Chang Z. G. Tian J. J. et al . (2019). Influence of dietary alpha-lipoic acid and lipid level on the growth performance, food intake and gene expression of peripheral appetite regulating factors in juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Aquaculture505, 412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.02.054

29

Hyland N. P. Sjöberg F. Tough I. R. Herzog H. Cox H. M. (2003). Functional consequences of neuropeptide YY 2 receptor knockout and Y2 antagonism in mouse and human colonic tissues. Br. J. Pharmacol.139, 863–871. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705298

30

Javahery S. Noori A. Hoseinifar S. H. (2019). Growth performance, immune response, and digestive enzyme activity in Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei Boone 1931, fed dietary microbial lysozyme. Fish Shellfish Immunol.92, 528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.06.049

31

Jiang Y. Y. Liu Z. S. Zhang L. Liu W. B. Li H. Y. Li X. F. (2024). Phosphatidylserine counteracts the high stocking density-induced stress response, redox imbalance and immunosuppression in fish megalobrama ambylsephala. Antioxidants13, 1–14. doi: 10.3390/antiox13060644

32

Kuebutornye F. K. A. Abarike E. D. Lu Y. (2019). A review on the application of Bacillus as probiotics in aquaculture. Fish Shellfish Immunol.87, 820–828. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.02.010

33

Kuebutornye F. K. A. Abarike E. D. Lu Y. S. Hlordzi V. Sakyi M. E. Afriyie G. et al . (2020). Mechanisms and the role of probiotic Bacillus in mitigating fish pathogens in aquaculture. Fish Physiol. Biochem.46, 819–841. doi: 10.1007/s10695-019-00754-y

34

Li Q. Cao Y. Y. Wang Y. T. Long X. D. Sun W. B. Yang H. et al . (2023). Toxic effects of copper sulfate and trichlorfon on the intestines of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquac. Res.2023, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2023/8360334

35

Li W. Li E. R. Wang S. Liu J. D. Wang M. X. Wang X. D. et al . (2025). Comparative effects of four feed attractants on growth, appetite, digestion and absorption in juvenile Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Aquaculture594, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741441

36

Liang X. F. Yu X. T. Han J. Yu H. H. Chen P. Wu X. F. et al . (2019). Effects of dietary protein sources on growth performance and feed intake regulation of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Aquaculture510, 216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.05.059

37

Liao Z. H. Liu Y. T. Wei H. L. He X. S. Wang Z. Q. Zhuang Z. X. et al . (2023). Effects of dietary supplementation of Bacillus subtilis DSM 32315 on growth, immune response and acute ammonia stress tolerance of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fed with high or low protein diets. Anim. Nutr.15, 375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2023.05.016

38

Liaqat R. Fatima S. Komal W. Minahal Q. Kanwal Z. Suleman M. et al . (2024). Effects of Bacillus subtilis as a single strain probiotic on growth, disease resistance and immune response of striped catfish (Pangasius hypophthalmus). PloS One19, 1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294949

39

Liu Z. S. Zhang L. Chen W. L. He C. F. Qian X. Y. Liu W. B. et al . (2024). Insights into the interaction between stocking density and feeding rate in fish Megalobrama ambylcephal based on growth performance, innate immunity, antioxidant activity, and the GH–IGF1 axis. Aquaculture580, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.740355

40

Llagostera P. F. Kallas Z. Reig L. de Gea D. A. (2019). The use of insect meal as a sustainable feeding alternative in aquaculture: Current situation, Spanish consumers' perceptions and willingness to pay. J. Cleaner Prod229, 10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.012

41

Lorenz E. K. Sabioni R. E. Volkoff H. Cyrino J. E. P. (2022). Growth performance, health, and gene expression of appetite-regulating hormones in Dourado Salminus brasiliensis, fed vegetable-based diets supplemented with swine liver hydrolysate. Aquaculture548, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737640

42

Mohammadi G. Adorian T. J. Rafiee G. (2020). Beneficial effects of Bacillus subtilis on water quality, growth, immune responses, endotoxemia and protection against lipopolysaccharide-induced damages in Oreochromis niloticus under biofloc technology system. Aquac Nutr.26, 1476–1492. doi: 10.1111/anu.13096

43

Mohapatra S. Chakraborty T. Prusty A. K. Das P. Paniprasad K. Mohanta K. N. (2012). Use of different microbial probiotics in the diet of rohu, Labeo rohita fingerlings: effects on growth, nutrient digestibility and retention, digestive enzyme activities and intestinal microflora. Aquac Nutr.18, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2011.00866.x

44

Monier M. N. Kabary H. Elfeky A. Saadony S. Abd El-Hamed N. N. B. Eissa M. E. H. et al . (2023). The effects of Bacillus species probiotics (Bacillus subtilis and B. licheniformis) on the water quality, immune responses, and resistance of whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vanname) against Fusarium solani infection. Aquac Int.31, 3437–3455. doi: 10.1007/s10499-023-01136-1

45

Mugwanya M. Dawood M. A. O. Kimera F. Sewilam H. (2022). Replacement of fish meal with fermented plant proteins in the aquafeed industry: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Aquac.15, 1–27. doi: 10.1111/raq.12701

46

Pang Y. Y. Zhang J. Y. Chen Q. Niu C. Shi A. Y. Zhang D. X. et al . (2024). Effects of dietary L-tryptophan supplementation on agonistic behavior, feeding behavior, growth performance, and nutritional composition of the Chinese mitten crab (Eriochei sinensis). Aquac Rep.35, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.101985

47

Peng D. Peng B. B. Li J. Zhang Y. P. Luo H. C. Xiao Q. Q. et al . (2022). Effects of three feed attractants on the growth, biochemical indicators, lipid metabolism and appetite of Chinese perch (Siniperc chuatsi). Aquac Rep.23, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2022.101075

48

Poncet N. Taylor P. M. (2013). The role of amino acid transporters in nutrition. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care16, 57–65. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32835a885c

49

Pothuraju R. Chaudhary S. Rachagani S. Kaur S. Roy H. K. Bouvet M. et al . (2021). Mucins, gut microbiota, and postbiotics role in colorectal cancer. Gut Microbes13, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1974795

50

Pulido-Rodriguez L. F. Cardinaletti G. Secci G. Randazzo B. Bruni L. Cerri R. et al . (2021). Appetite regulation, growth performances and fish quality are modulated by alternative dietary protein ingredients in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) culture. Animals11. doi: 10.3390/ani11071919

51

Rao P. Rodriguez R. L. Shoemaker S. P. (2018). Addressing the sugar, salt, and fat issue the science of food way. NPJ Sci. Food2, 12. doi: 10.1038/s41538-018-0020-x

52

Rashidian G. Moghaddam M. M. Mirnejad R. Azad Z. M. (2021). Supplementation of zebrafish (Dani rerio) diet using a short antimicrobial peptide: Evaluation of growth performance, immunomodulatory function, antioxidant activity, and disease resistance. Fish Shellfish Immunol.119, 42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2021.09.035

53

Ringo E. Van Doan H. Lee S. H. Soltani M. Hoseinifar S. H. Harikrishnan R. et al . (2020). Probiotics, lactic acid bacteria and bacilli: interesting supplementation for aquaculture. J. Appl. Microbiol.129, 116–136. doi: 10.1111/jam.14628

54

Rodigues M. L. Damasceno D. Z. Gomes R. L. M. Sosa B. D. Moro E. B. Boscolo W. R. et al . (2021). Probiotic effects (Bacillus cereus and Bacillus subtilis) on growth and physiological parameters of silver catfish (Rhamdia quele). Aquac Nutr.27, 454–467. doi: 10.1111/anu.13198

55

Sabioni R. E. Lorenz E. K. Cyrino J. E. P. Volkoff H. (2022). Feed intake and gene expression of appetite-regulating hormones in Salminus brasiliensis fed diets containing soy protein concentrate. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. a-Mol Integr. Physiol.268, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2022.111208

56

Saravanan K. Sivaramakrishnan T. Praveenraj J. Kiruba-Sankar R. Haridas H. Kumar S. et al . (2021). Effects of single and multi-strain probiotics on the growth, hemato-immunological, enzymatic activity, gut morphology and disease resistance in Rohu, Labeo rohita. Aquaculture540, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.736749

57

Sheng Z. Y. Xu J. M. Zhang Y. Wang Z. J. Chen N. S. Li S. L. (2023). Dietary protein hydrolysate effects on growth, digestive enzymes activity, and expression of genes related to amino acid transport and metabolism of larval snakehead (Chann argus). Aquaculture563, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738896

58

Soengas J. L. Cerdá-Reverter J. M. Delgado M. J. (2018). Central regulation of food intake in fish: an evolutionary perspective. J. Mol. Endocrinol.60, R171–R199. doi: 10.1530/jme-17-0320

59

Tough I. R. Holliday N. D. Cox H. M. (2006). Y4 receptors mediate the inhibitory responses of pancreatic polypeptide in human and mouse colon mucosa. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.319, 20–30. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106500

60

Tusche K. Berends K. Wuertz S. Susenbeth A. Schulz C. (2011). Evaluation of feed attractants in potato protein concentrate based diets for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture321, 54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.08.020

61

Verri T. Barca A. Pisani P. Piccinni B. Storelli C. Romano A. (2017). Di- and tripeptide transport in vertebrates: the contribution of teleost fish models. J. Comp. Physiol. B-Biochem Syst. Environ. Physiol.187, 395–462. doi: 10.1007/s00360-016-1044-7

62

Wang W. Y. De Mejia E. G. (2005). A new frontier in soy bioactive peptides that may prevent age-related chronic diseases. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf.4, 63–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2005.tb00075.x

63

Wang X. Dong Y. Z. Huang Y. Y. Tian H. Y. Zhao H. J. Wang J. F. et al . (2024). Docosahexaenoic acid-enriched diet improves the flesh quality of freshwater fish (Megalobrama amblycephala): Evaluation based on nutritional value, texture and flavor. Food Chem.460, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140518

64

Wang A. R. Fu Y. Fu L. L. Li M. G. Xu J. Guo X. J. et al . (2024). Dietary monosodium glutamate affects the growth and feed utilization of Eriocheir sinensis by regulating the appetite related genes expression. Aquac Rep.38, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102310

65

Wang K. Z. Jiang W. D. Wu P. Liu Y. Jiang J. Kuang S. Y. et al . (2018). Gossypol reduced the intestinal amino acid absorption capacity of young grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture492, 46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.03.061

66

Wang L. Lei M. T. Yu A. L. Chen Z. M. Ibrahim U. B. Li P. et al . (2024). Dried porcine soluble augments dietary fishmeal replacement by poultry by-product meal for large yellow croaker Larimichthys crocea. Aquaculture593, 9. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741306

67

Wang C. A. Xu Z. Lu S. X. Jiang H. B. Li J. N. Wang L. S. et al . (2022). Effects of dietary xylooligosaccharide on growth, digestive enzymes activity, intestinal morphology, and the expression of inflammatory cytokines and tight junctions genes in triploid Oncorhynchus mykiss fed a low fishmeal diet. Aquac Rep.22, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2021.100941

68

Wen H. L. Feng L. Jiang W. D. Liu Y. Jiang J. Li S. H. et al . (2014). Dietary tryptophan modulates intestinal immune response, barrier function, antioxidant status and gene expression of TOR and Nrf2 in young grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Fish Shellfish Immunol.40, 275–287. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.07.004

69

Wu P. S. Liu C. H. Hu S. Y. (2021). Probiotic Bacillus safensis NPUST1 Administration Improves Growth Performance, Gut Microbiota, and Innate Immunity against Streptococcus iniae in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Microorganisms9, 1–19. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9122494

70

Xia Y. Wang M. Gao F. Y. Lu M. X. Chen G. (2020). Effects of dietary probiotic supplementation on the growth, gut health and disease resistance of juvenile Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Anim. Nutr.6, 69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2019.07.002

71

Xiong W. Cao X. Chen K. He C. Wang X. Guo H. et al . (2024). Recombinant Bacillus subtilis expressing functional peptide and its effect on the growth, antioxidant capacity and intestine in Megalobrama amblycephala. Aquaculture586, 740813. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.740813

72

Xu X. Y. Yang H. Zhang C. Y. Bian Y. H. Yao W. X. Xu Z. et al . (2022). Effects of replacing fishmeal with cottonseed protein concentrate on growth performance, flesh quality and gossypol deposition of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Aquaculture548, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737551

73

Yacoob S. Y. Anraku K. Archdale M. V. Matsuoka T. Kiyohara S. (2002). Exposure of taste buds to potassium permanganate and formalin suppresses the gustatory neural response in the Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus). Aquac Res.33, 445–453. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2109.2002.00694.x

74

Yan Y. Lin Y. Gu Z. Y. Lu S. Y. Zhou Q. L. Zhao Y. F. et al . (2024). Dietary fishmeal substitution with Antarctic krill meal improves the growth performance, lipid metabolism, and health status of oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense). Aquac Rep.37, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102202

75

Yan Y. Lin Y. Zhang L. Gao G. D. Chen S. Y. Chi C. H. et al . (2023). Dietary supplementation with fermented antarctic krill shell improved the growth performance, digestive and antioxidant capability of Macrobrachium nipponense. Aquac Rep.30, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2023.101587

76

Yuan Z. H. Feng L. Jiang W. D. Wu P. Liu Y. Jiang J. et al . (2020). Choline deficiency decreased the growth performances and damaged the amino acid absorption capacity in juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture518, 12. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734829

77

Yuan X. Y. Jiang G. Z. Cheng H. H. Cao X. F. Shi H. J. Liu W. B. (2019). An evaluation of replacing fish meal with cottonseed meal protein hydrolysate in diet for juvenile blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala): Growth, antioxidant, innate immunity and disease resistance. Aquac Nutr.25, 1334–1344. doi: 10.1111/anu.12954

78

Yuan X. Y. Liu W. B. Wang C. C. Huang Y. Y. Dai Y. J. Cheng H. H. et al . (2020). Evaluation of antioxidant capacity and immunomodulatory effects of cottonseed meal protein hydrolysate and its derivative peptides for hepatocytes of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). Fish Shellfish Immunol.98, 10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.01.008

79

Zaineldin A. I. Hegazi S. Koshio S. Ishikawa M. Bakr A. El-Keredy A. M. S. et al . (2018). Bacillus subtilis as probiotic candidate for red sea bream: Growth performance, oxidative status, and immune response traits. Fish Shellfish Immunol.79, 303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.05.035

80

Zarantoniello M. Rodriguez L. F. P. Randazzo B. Cardinaletti G. Giorgini E. Belloni A. et al . (2022). Conventional feed additives or red claw crayfish meal and dried microbial biomass as feed supplement in fish meal-free diets for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): Possible ameliorative effects on growth and gut health status. Aquaculture554, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738137

81

Zhang C. Wang X. D. Su R. Y. He J. Q. Liu S. B. Huang Q. C. et al . (2022). Dietary gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) supplementation increases food intake, influences the expression of feeding-related genes and improves digestion and growth of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Aquaculture546, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737332

82